Abstract

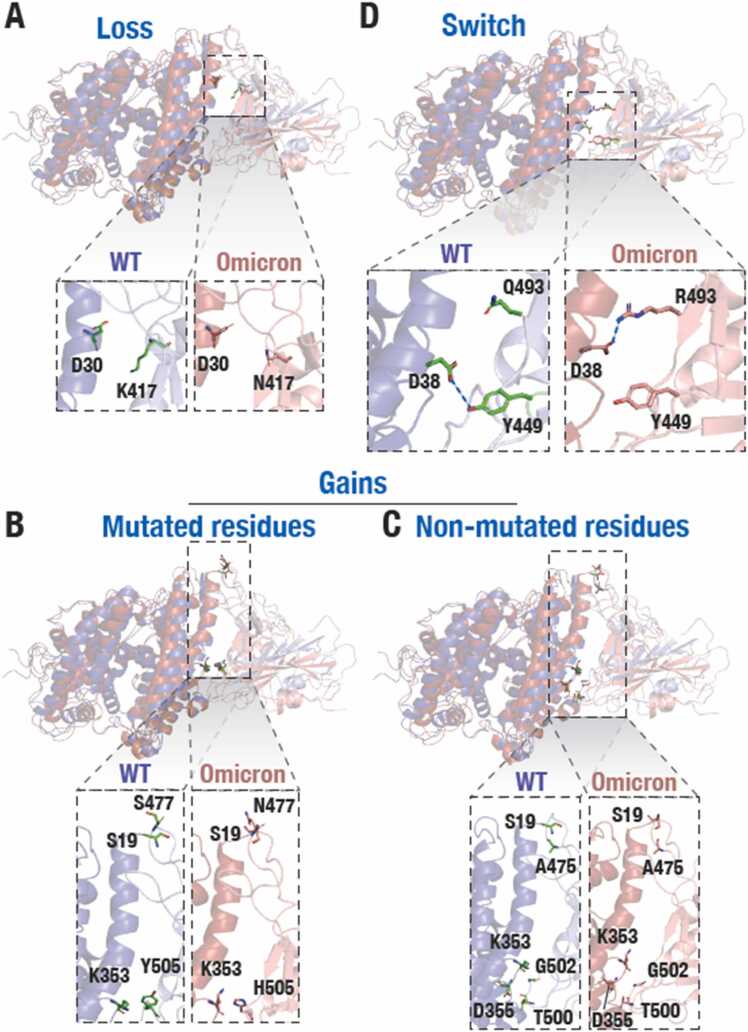

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant containing 15 mutations, including the unique Q493R, in the spike protein receptor binding domain (S1-RBD) is highly infectious. While comparison with previously reported mutations provide some insights, the mechanism underlying the increased infections and the impact of the reversal of the unique Q493R mutation seen in BA.4, BA.5, BA.2.75, BQ.1 and XBB lineages is not yet completely understood. Here, using structural modelling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we show that the Omicron mutations increases the affinity of S1-RBD for ACE2, and a reversal of the unique Q493R mutation further increases the ACE2-S1-RBD affinity. Specifically, we performed all atom, explicit solvent MD simulations using a modelled structure of the Omicron S1-RBD-ACE2 and compared the trajectories with the WT complex revealing a substantial reduction in the Cα-atom fluctuation in the Omicron S1-RBD and increased hydrogen bond and other interactions. Residue level analysis revealed an alteration in the interaction between several residues including a switch in the interaction of ACE2 D38 from S1-RBD Y449 in the WT complex to the mutated R residue (Q493R) in Omicron complex. Importantly, simulations with Revertant (Omicron without the Q493R mutation) complex revealed further enhancement of the interaction between S1-RBD and ACE2. Thus, results presented here not only provide insights into the increased infectious potential of the Omicron variant but also a mechanistic basis for the reversal of the Q493R mutation seen in some Omicron lineages and will aid in understanding the impact of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 evolution.

Keywords: ACE2, COVID-19, Omicron, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, Infectious Disease, SARS-CoV-2, S1 Spike Protein

Abbreviations: ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; RBD, Receptor binding domain; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; MD simulations, Molecular dynamics simulations

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

· SARS-CoV-2 Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD showed reduced dynamics and enhanced interaction compared to the WT complex

-

•

· Omicron complex showed several changes at residue level interactions involving both mutated and non-mutated residues

-

•

· Omicron complex showed a number of salt bridge interactions formed by the R493 residue arising from the unique Q493R mutation

-

•

· Reversal of the Q493R mutation in the Omicron S1-RBD further enhanced its interaction with ACE2 leading to a reduced interfacial dynamics

1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the causative agent of COVID-19, has caused more than 660 million infections resulting in more than 6.7 million deaths globally by mid-January 2023 [COVID-19 Map – Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (jhu.edu)].[1], [2], [3] The virus binds the host cell through the receptor binding domain (RBD) with its S1 subunit to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor expressed on host cell membranes.[4], [5], [6], [7] This is then followed by cleavage of spike protein by the host cell transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) at the furin cleavage site (S1/S2 subunit), permitting the fusion of the viral envelope and the cellular membrane of the host, facilitated by the S2 subunit, and later entry of the virus by endocytosis.[8], [9] Importantly, numerous variants have been registered since the onset of COVID-19 pandemic in 2019. Of these, Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1) and Delta (B.1.617.2) are designated as variants of Concern (VOCs) whereas Lambda (C.73) and Mu (B.1.621) as variants of interest (VOIs) by the World Health Organization (WHO). Former VOIs, Kappa (B.1.617.1), Iota (B.1.526) and Eta (B.1.525) have been regrouped to Variants under monitor (VUM) as the evidence of phenotype and epidemiology is still unclear.[10], [11], [12], [13] In continuation with these, a new variant named Omicron (B.1.1.529) was reported to cause a COVID-19 outbreak in the Gauteng province, South Africa during late November 2021. Further, on 26th of November, WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on SARS-CoV-2 Virus Evolution (TAG-VE) labeled B.1.1.529 a “Variant of Concern” (VOC), the supreme categorization for an evolving coronavirus variant. Initially, South Africa’s fourth COVID-19 wave was dominated by three Omicron lineages (BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3) and was hastily swapped by BA.4 and BA.5 by the first week of April, 2022.[14], [15] As of January 2023, Omicron infection is a matter of global concern.[16], [17], [18] In fact, the Omicron variant has dominated the Delta variant globally with respect to number of infections within a short span of time (Fig. 1A) (https://covariants.org/per-variant).[19], [20].

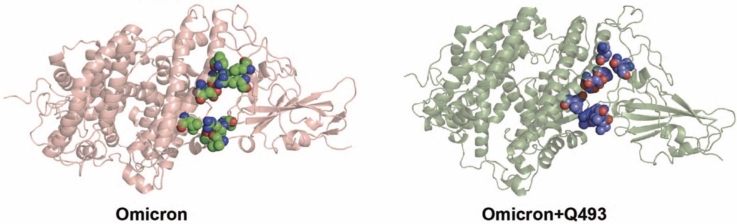

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant & mutations in the S1-RBD. (A) Schematic graph showing the emergence of the Omicron variant with a much higher reported cases (Relative Variant Genome Frequency) compared to the Delta variant. Source: GISAID; https://www.gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/). (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of B.1.1.529/1-194 (Omicron) and Parental/1-194 (WT) S1-RBD (residues 333-526) with the mutations highlighted with a light blue background. (C) Cartoon representation of the WT (PDB: 6M0J) and Omicron variant (modelled structure) ACE2-S1-RBD complex (WT – ACE2, deep blue & S1-RBD, light blue; Omicron – ACE2, fire brick & S1-RBD, salmon) showing the relative positioning of interfacial residues in ACE2 and in S1-RBD (green, WT; red, Omicron variant).

Of the 36 mutations reported in the Omicron variant, 30 are in its spike protein alone. These include the E484A, K417N, N440K and Q493R mutations, which have been reported to be associated with helping the virus to escape antibody detection.[13], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28] Additionally, a number of Omicron mutations have been reported to increase the affinity of the spike protein for ACE2, thus, providing some basis for the increased infectivity of the variant. For instance, the N501Y mutation has been reported to display a stable interaction compared to the wild type (WT) S1-RBD [29] likely providing a reason for the increased affinity of the N501Y mutant S1-RBD for ACE2 receptor.[30], [31] Furthermore, the S477N mutation located at the ACE2-S1-RBD interface has arisen independently multiple times in clade 20B [32] and contributes to the increased affinity to the host receptor.[31], [33] It is important to note that several other mutations in the Omicron S1-RBD such as the G339D, S371L S373P, S375F, G446S, T478K, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, Y505H are also present in the ACE2-S1-RBD interface.[13], [27], [34], [35], [36], [37] It also has been reported that the experimental KD value of the Omicron (B1.1.529) variant is 20.63 nM compared to a value of 26.37 nM for the WT (Wuhan) strain while a predicted KD value ∼12.98 nM for the BA.2 variant.[38] Overall, it appears that these mutations in combination can potentially alter the structural properties of the protein that may result in an altered interaction between Omicron S1-RBD and ACE2 receptor.[39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44].

In the current study, we utilized structural modelling and all-atom, explicit solvent MD simulations of the Omicron variant S1-RBD with the ACE2 receptor to gain insights into the mechanism underlying its increased affinity for ACE2 and higher transmission rate. Comparison of simulation trajectories of the WT reported previously[29] and the Omicron variant S1-RBD in complex with ACE2 showed a decreased residue level dynamic and free energy change alongside an increased number of H-bond, van der Waals and electrostatic interactions in the Omicron S1-RBD. Additionally, a substantial difference in the salt bridge interactions were observed in the Omicron S1-RBD including at the ACE2-S1-RBD interface. Importantly, the analysis also revealed the formation of unique salt bridge interactions formed by the R493 (Q493 in the WT; Q493R mutation) with the D38 (most stable), E35 and E37 residue in ACE2 and reversion of this single mutation to the original Q resulted in a further increase in ACE2-S1-RBD affinity as indicated by a decrease in the free energy change likely providing a basis for the prevalence of Omicron variant with this reversion.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Structural modeling of Omicron mutations in the ACE2-S1-RBD complex

We generated a structural model of the Omicron variant S1-RBD spanning residues from T333 to G526 of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein and containing all mutations in complex with ACE2 spanning residues from S19 to D615 of human ACE2.[26], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49]. For this, we utilized the available crystal structure of the ACE2-S1-RBD complex (PDB ID: 6M0J) [50] and the homology-based protein structure modelling program, Modeller 9.19[51]. Briefly, sequences of ACE2 and WT and Omicron variant S1-RBD were aligned and a homology-based models were generated with very slow MD refinement. Finally, the lowest energy model was selected and assessed for quality using the Procheck program. [https://servicesn.mbi.ucla.edu/PROCHECK/] [52] (Supp. Fig. 1). The structural model of ACE2 with the Revertant S1-RBD complex was generated using the Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD and the “Mutagenesis” tool in PyMOL.

2.2. ACE2-S1-RBD MD simulations

Briefly, Nanoscale Molecular Dynamics (NAMD) 2.13 software [53] and CHARMM36 force field [54] were utilized to perform the MD simulations as described previously [55], [56], [57]. The ACE2-S1-RBD models were used as inputs to generate the biomolecular simulation systems. The topology and parameter files for the simulations were prepared using the QwikMD plugin [58] available in Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) 1.9.3 software. Briefly, proteins were solvated in explicit solvent using TIP3P [59] cubic water box that contains 0.15 M NaCl with Periodic Boundary Conditions applied. The simulation systems consisted of 453089, 416106, and 416103 atoms for WT, Omicron, and Revertant, respectively. Before running production simulations, energy minimization and thermal equilibration were performed as described previously.[57], [60] Production simulation runs were performed for 100 ns in duplicates for all simulation systems. A 2-fs integration time step was selected for all simulations where trajectory frames were saved every 10,000 steps. A 12 Å cut-off with 10 Å switching distance was chosen to handle short-range non-bonded interactions, while long-range non-bonded electrostatic interactions were handled using Particle-mesh scheme at 1 Å PME grid spacing.

2.3. ACE2-S1-RBD MD simulation trajectory analysis

Following MD simulations, trajectory analysis was carried out using the available VMD plugins. Independent calculations of root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of backbone atoms were carried out using “RMSD trajectory Tool” in VMD. Measurements of root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of Cα atoms were performed after aligning the trajectories using Cα atoms from both ACE2 and S1-RBD (whole complex), and plotted separately for ACE2 and S1-RBD. Hydrogen bond analysis was performed at a switching angle of 20°and a cut-off distance between ACE2 and S1-RBD of 3.5 Å using “Hydrogen Bonds” extension in VMD [61]. The H-bond analysis was done for all individual residues pairs rather than unique pairs using the plugin. Salt bridge analysis was performed using the “Salt bridges” extension with an Oxygen-Nitrogen cut off of 3.2 Å and further analysis was narrowed down to the set of unique salt bridges acquired from each complex.[62] Inter residue (ACE2:WT/Omicron/Revertant(Omicron+Q493)) salt bridge distances were calculated using the inter residue distance calculation script.[63] Furthermore, binding free energy changes were calculated using the molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area method (MM-PBSA) [64], [65] using the CaFE 1.0 tool.[66] Residues at the ACE2-S1-RBD interface were determined at cut-off distance of 5 Å using PyMOL, “NAMD Energy” VMD plugin was used to perform energy calculations. Center-of-mass distances between paired selections were determined using VMD.[62] The interfacial residues determined by us previously were utilized to determine the interfacial inter-residue distances over the simulations (3 runs each of WT, Omicron and Revertant), that were then normalized with their respective average distances and plotted as a ratio of Omicron to WT and Revertant to WT ACE2-S1-RBD complexes.[29] Python scripts were used to obtain the above-mentioned average distances and standard deviation of the interfacial residue distance values.

The composite snapshot images were prepared from 11 representative trajectory frames captured 10 ns apart and compiled using PyMOL.[67] Trajectory movies representing 100 ns simulations were prepared from 500 trajectory frames (10 frames/ns) generated using VMD Movie Maker plugin [62] and compiled at 60 fps using Fiji distribution of ImageJ software [67].

2.4. Data analysis and figure preparation

Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism (version 9 for macOS, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA; www.graphpad.com) were used for data analysis and graph preparation. Figures were assembled using Adobe Illustrator.

3. Results & discussions

3.1. Omicron variant S1-RBD structural modeling in complex with ACE2 and mapping of mutations

The Omicron variant has been recognized by WHO as a variant of concern (VOC) with a much higher transmission rate compared to other variants such as the Delta (Fig. 1A), suggesting an increased affinity for the variant S1-RBD for ACE2. To understand the mechanism underlying the increased affinity of the Omicron variant S1-RBD, we generated a homology-based structural model of the ACE2-S1-RBD complex containing all mutations (Fig. 1B) using the previously described ACE2-S1-RBD structure (PDB ID:6MOJ) (Fig. 1C) for subsequent use in MD simulations. These include 8 mutations in the ACE2-S1-RBD interface (K417N, G446S, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H) (Fig. 1C) and 7 mutations (G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, N440K, S477N, T478K) in other parts of the protein.

3.2. Altered S1-RBD dynamics in the Omicron variant

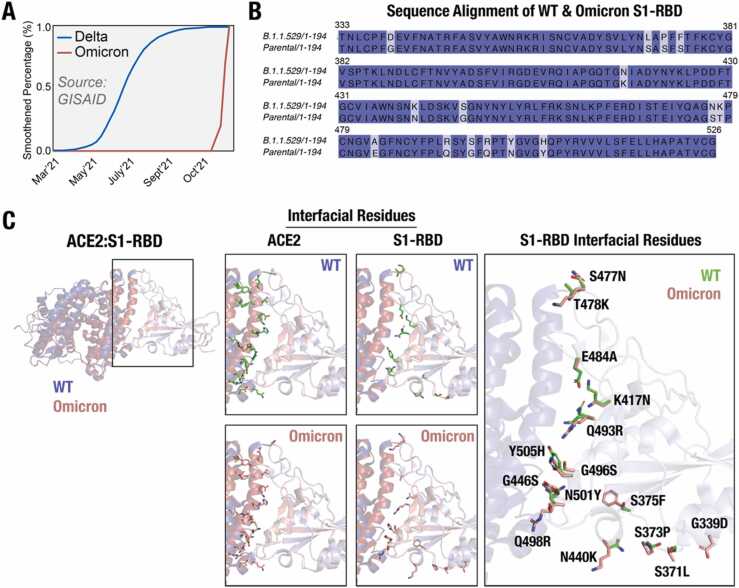

To understand the impact of these mutations in the interaction with ACE2, we performed MD simulations using the structural model of the Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD complex. We utilized previously reported trajectories of the WT ACE2-S1-RBD complex for the purpose of comparison.[57] A evaluation of the MD simulation trajectories of the Omicron variant complex did not show any noticeable difference in the dynamics in ACE2, either in terms of whole structure or in RMSD values (Fig. 2A, B). However, Omicron-S1-RBD showed noticeable decreases in structural fluctuation, as assessed from the RMSF values (Fig. 2A, B). Comparison of RMSF values of individual amino acid residues in ACE2 indicated some differences such as a decrease in RMSF values across residues 118–184, 219–419 and 500–600 in the Omicron complex compared to WT ACE2 over the entire trajectory (Fig. 2C, D). However, a similar analysis of S1-RBD residues revealed substantial decrease (Fig. 2C, D), indicating a change in the structural dynamics of S1-RBD in the Omicron variant over the entire trajectory. Specifically, residue positions from 375-382, 431–450 and 493–509 showed a substantially reduced RMSF values in the Omicron complex (Fig. 2C, D). Overall, these results indicate a decrease in the structural dynamics in S1-RBD in the Omicron variant suggesting an enhanced interaction between ACE2 and S1-RBD in the Omicron variant.

Fig. 2.

Decreased structural dynamics in the Omicron S1-RBD in complex with ACE2. (A) Cartoon representation of the WT (left panel) and the Omicron variant (right panel) ACE2-S1-RBD complex showing structural evolution of the complexes over time in a 100 ns MD simulation. Images were captured every 10 ns. (B,C) Graph showing backbone (Cα) RMSD (B) and RMSF (C) values of ACE2 (left panel) and S1-RBD (right panel) obtained from three independent 100 ns WT and Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD complex MD simulations. Note the general decrease in the fluctuations in the Omicron S1-RBD. (D) Graph showing percentage mean differences in RMSF values of ACE2 and S1-RBD of WT and Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD complexes.

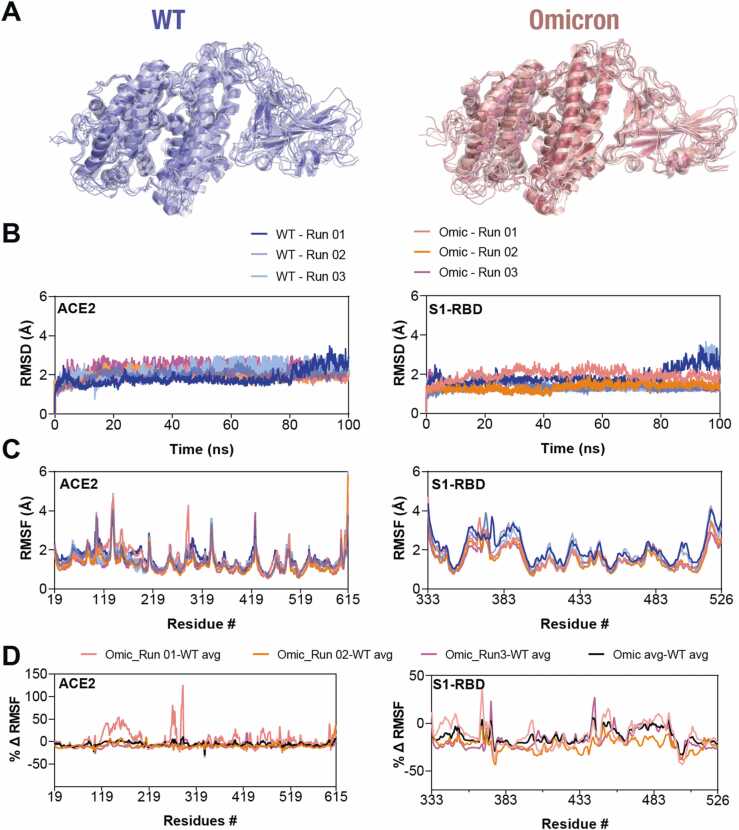

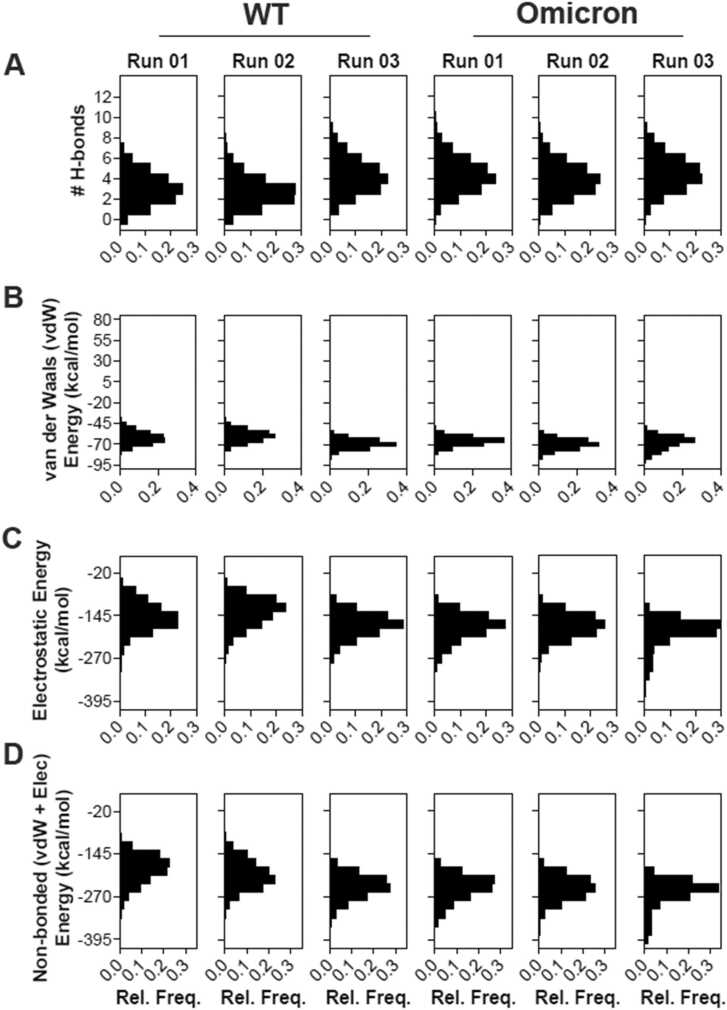

3.3. Increased H-bond and other non-covalent interactions

To understand the mechanism underlying reduced dynamics of residues in the Omicron variant, we first analyzed the trajectories for H-bond formation using cutoffs of 3.5 Å and 20° for H-bond distance and A-D-H angle, respectively. This analysis showed that most of the mutated residues are located within the H-bond formation boundaries with ACE2 and show significantly alter H-bond formation and % occupancy at the interface (Table 1). Newly formed H-bonds in the Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD interface include D38-Q493R and K353-Y505H (Fig. 3B, D), whereas K417N mutation in Omicron led to loss of D30-K417H-bond found in the WT (Fig. 3A). In addition, there was a noticeable increase in the % occupancy of H-bonds formed by S19-N477 and K353-H505 in Omicron (Table 1, Fig. 3B). The unique mutations Q493R and Y505H showed an increased H-bond occupancy in both the Omicron runs while in the WT do not show any interaction. On the other hand, we observed that the % occupancy of other H-bonds formed by non-mutated RBD residues were notably increased in the variant ACE2-S1-RBD interface, including D355-T500, S19-A475, K353-G502 and Q24-A475 (Table1, Fig. 3C) in the Omicron variant. We hypothesized that these increase in the occupancy of H-bonds in the Omicron variant as an effect of interfacial mutated residues that potentially drive the two chains closer at the interface. This is supported by the fact that all H-bonds that showed substantial decrease in the % occupancy were only those formed by residues that were mutated in the Omicron variant (except for D38-Y449, which showed a decreased % occupancy). Overall, these data suggest an increase in the number of H-bonds formed at the interface in the Omicron S1-RBD complex compared to the WT complex (Fig. 4A). Additionally, we observed changes in the van der Waals energy and electrostatic interaction energies in the Omicron variant compared to the WT complex (Fig. 4B-D), suggesting an increased binding affinity of the Omicron variant compared to the WT. We note that the loss of two charged residues due to the K417N and E484A mutations in Omicron variant S1-RBD, which might have a role to play in immune escape [68], [69], [70], could minimally impact its interaction with ACE2 as these residues do not appear to be involved in salt-bridge formation in the WT complex.

Table 1.

Altered H-bond interaction between interfacial residues in the Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD complex. Table showing percentage occupancy of listed H-bonds formed by interfacial residues determined from three independent MD simulations of the WT and the Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD complexes. The H-bonds formed by residues mutated in Omicron and those that are not mutated in Omicron were ranked according to the mean difference (descending order) in percentage occupancy. Note the alteration in H-bond formation by non-mutated residues (T500, G502, A475, Y449) in the Omicron complex and that D38 and Q493(R in the Omicron variant) form multiple H-bonds leading to a cumulative occupancy of > 100%.

| WT |

Omicron |

Difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | ACE2 | RBD | Run 01 | Run 02 | Run 03 | Run 01 | Run 02 | Run 03 | mean ± S.D (p value) | |

| 1 | Residues mutated in Omicron | D38-Side | Q493(R)-Side* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 138.6 | 74.0 | 131.8 | 114.8 ± 13.1 (0.005) |

| 2 | S19-Main | S477(N)-Side* | 2.5 | 1.3 | 8.6 | 29.9 | 22.2 | 49.2 | 29.6 ± 6.7 (0.0237) | |

| 3 | K353-Main | Y505(H)-Side | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 38.5 | 16.0 | 15.7 | 23.4 ± 5.9 (0.0362) | |

| 4 | Y41-Side | Q498(R)-Side | 2.3 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -4.3 ± 2.5 (0.0803) | |

| 5 | K31-Side | Q493(R)-Side | 5.7 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -7.6 ± 3.4 (0.0172) | |

| 6 | Q42-Side | Q498(R)-Side | 16.3 | 8.0 | 10.5 | 4.2 | 6.4 | 0.0 | -8.1 ± 3.5 (0.0599) | |

| 7 | K353-Side | Q498(R)-Side | 11.4 | 6.2 | 13.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -10.4 ± 3.9 (0.0091) | |

| 8 | E37-Side | Y505(H)-Side | 27.7 | 4.3 | 42.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | -24.1 ± 6 (0.093) | |

| 9 | E35-Side | Q493(R)-Side | 45.6 | 23.9 | 45.8 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -36.1 ± 7.4 (0.009) | |

| 10 | D30-Side | K417(N)-Side | 37.8 | 37.6 | 53.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -42.8 ± 8 (0.0011) | |

| 11 | Residues not mutated in Omicron | D355-Side | T500-Side | 2.8 | 14.1 | 23.1 | 49.2 | 50.9 | 50.5 | 36.9 ± 7.4 (0.0033) |

| 12 | K353-Main | G502-Main | 36.1 | 0.0 | 49.0 | 44.1 | 50.2 | 23.8 | 11 ± 4.1 (0.5458) | |

| 13 | Q24-Side | A475-Main | 2.8 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 12.7 | 15.9 | 13.4 | 9.6 ± 3.8 (0.002) | |

| 14 | S19-Side | A475-Main | 24.0 | 20.8 | 18.7 | 32.1 | 22.7 | 23.7 | 5 ± 2.7 (0.2106) | |

| 15 | D38-Side | Y449-Side | 5.6 | 15.3 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -8.9 ± 3.7 (0.0476) | |

Fig. 3.

Altered interfacial residue interaction in the S1-RBD and ACE2 in the Omicron variant. (A) Cartoon representation of ACE2-S1-RBD complexes in the WT and the Omicron variant S1-RBD showing the loss of H-bond interaction between D30 (ACE2) and the WT K417 (S1-RBD) in the Omicron variant (N417) S1-RBD. (B) Cartoon representation of ACE2-S1-RBD complexes in the WT and the Omicron variant S1-RBD showing gain of H-bond interaction due to mutated residues left panel; N477 and H505 in the Omicron variant S477 and Y505 in the WT with S19 and K353 residues in ACE2 and (C) non-mutated residues (right panel; A475, G502 and T500 in S1-RBD with S19, K353 and D355 in ACE2, respectively). (D) Cartoon representation of ACE2-S1-RBD complexes in the WT and the Omicron variant S1-RBD showing switching of interaction R493 in Omicron variant S1-RBD with D38 in ACE2 from Y499 in WT S1-RBD with the same residue in ACE2.

Fig. 4.

Enhanced interaction of the Omicron S1-RBD with ACE2. (A) Histogram showing the number of H-bonds formed by the WT, Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD over three individual 100 ns of MD simulation. An increase in the number of H-bonds were observed in Omicron. (B,C,D) Histograms showing the distribution of van der Waals (vdW) energy (B), electrostatic energy (Ele) (C) and total interaction energy (D) of the WT, Omicron in complex with ACE2 obtained from three independent 100 ns MD simulations. Note the increased non-covalent interaction energies in the Omicron variant.

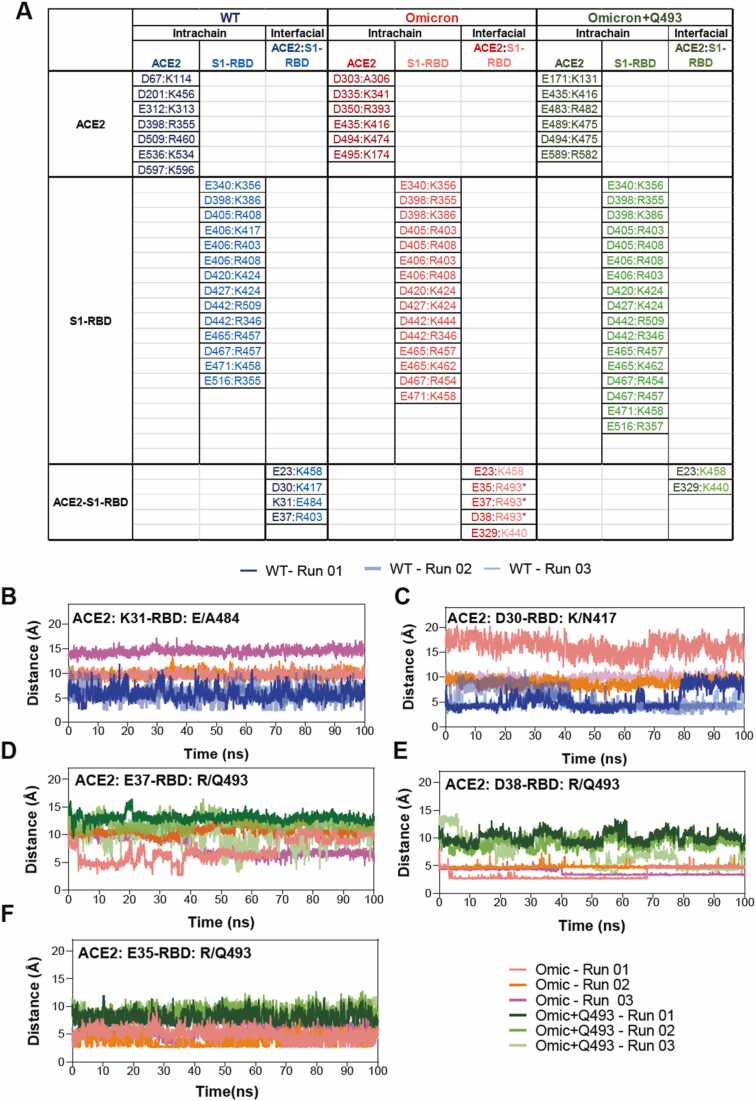

3.4. Salt bridge analysis reveals novel interactions through the Q493R mutation in the Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD complex

While we observed a generally increased H-bond formed by some residues in the Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD complex, we also observed a decreased fractional occupancy of the D38-Y449H-bond apparently due to D38 shifting orientation at the interface to form a salt bridge interaction with the Q493R in the Omicron RBD. Therefore, we performed a comprehensive analysis and comparison of salt bridge interactions formed in the WT and the Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD complexes. This is particularly relevant since the Omicron variant possesses 6 mutations that results in a gain of charged residues (G339D, N440K, T478K, Q493R, Q498R, and Y505H) in the S1-RBD, which raises the possibility of increased number salt bridges formed in the variant complex. This analysis revealed the loss of several WT ACE2 intra-chain salt bridge interactions (D201:K456, E312:K313, D398:R355, D509:R460, D597:K596), while new salt bridge interactions (E435:K416, E495:K174, D335:K341, D494:K474, D350:R393, D303:A306 and many more) were formed in ACE2 of the Omicron variant complex (Fig. 5A) including some of the charged residues forming additional partners such as D405 interacts with R408 and R403 in the Omicron and Revertant complex. These likely reflect an alteration in the conformation of ACE2 in the complex. Similarly, the intrachain salt bridge interaction between residues in ACE2 and D442:K444 was newly formed in S1-RBD in the Omicron variant complex and were lost in the Revertant complex suggesting a crucial role played by the Q493R mutation (Fig. 5A, D-F). Remarkably, three interfacial salt bridge interactions formed by ACE2 and S1-RBD residues D30 and K417, K31 and E484 and E37 and R403 were lost while three new salt bridge interactions were formed by E37, E35 and D38 residues in ACE2 and R493 residue in the S1-RBD in the Omicron variant complex (Fig. 5A-F). E23 and K458 ACE2-S1-RBD complex were found in the WT, Omicron and Omicron+Q493 (Fig. 5A). Thus, amongst the six mutations resulting in the substitution of charged residues, only Q493R mutation appears to drive the increased salt bridge interaction-dependent ACE2-S1-RBD interaction in the Omicron variant.

Fig. 5.

Increased salt bridge interactions in the Omicron variant ACE2:S1-RBD complex. (A) Table summarizing the inter and intra-salt bridge analysis of WT, Omicron and revertant (Omicron+Q493) S1-RBD complexed with ACE2. The asterisk indicates mutated S1-RBD residues in Omicron. (B,C) Graph showing distance between ACE2:K31 and S1-RBD:E484 or A484 (Omicron) (B) and ACE2:D30 and S1-RBD:K417 or N417 (Omicron) (C) showing the loss of salt bridge interaction over the simulation period. (D,E,F) Graph showing distance between ACE2:E37 and S1-RBD:R493 or Q493 (revertant) (D), ACE2:D38 and S1-RBD: R493 or Q493 (revertant) (E) and ACE2:E35 and S1-RBD: R493 or Q493 (revertant) showing the loss of salt bridge interaction in revertant over the simulation period. Note the novel salt bridges formed by R493 in the Omicron complex.

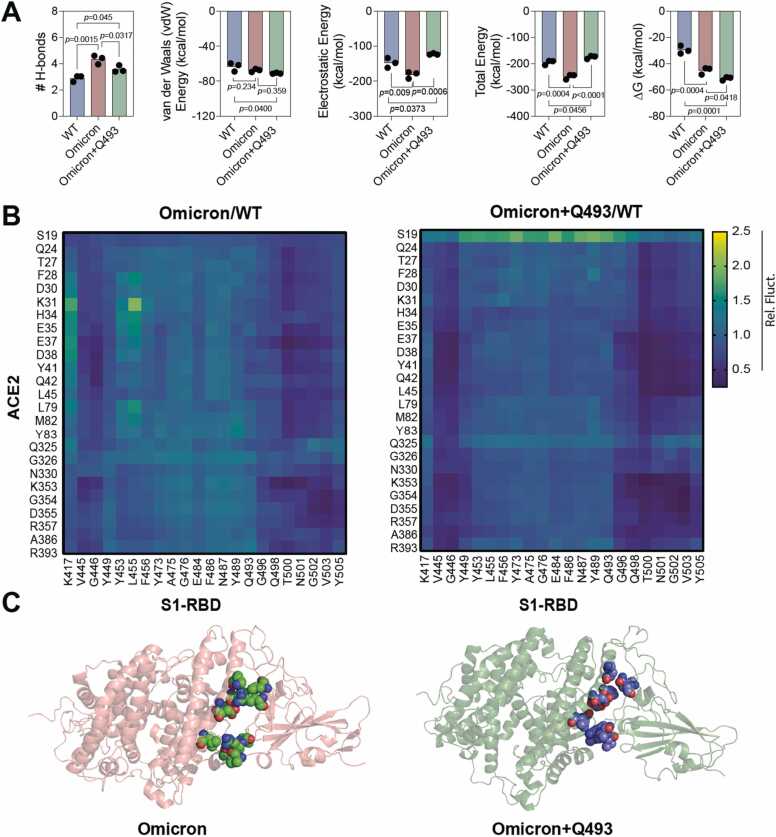

3.5. Unraveling the vital role of R493 using Revertant-S1-RBD in complex with ACE2

Given the three new interfacial salt bridge interactions formed by the R493 residue in the Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD complex, we attempted to understand if indeed it can play a significant role in driving the increased interaction of the Omicron S1-RBD with ACE2. For this, we performed three independent, 100 ns long all-atom MD simulation runs with the Omicron S1-RBD containing all but without the Q493R mutation (henceforth referred to as Revertant). Trajectory analysis revealed a greater RMSD value for ACE2 in the Revertant (2.27 ± 0.26 Å) compared to either the WT (1.91 ± 0.23 Å) or the Omicron variant (2.01 ± 0.26 Å) suggesting a general increase in the structural dynamics in ACE2 in the Revertant complex (Supp. Fig. 2, Fig. 3B,C). Additionally, the S1-RBD RMSD fluctuation was seen to be lowest in the Omicron complex (1.24 ± 0.16 Å) followed by the Revertant (1.37 ± 0.13 Å) and WT (1.40 ± 0.23 Å) suggesting that the key residue plays an important role in the S1-RBD structural stability in the Omicron complex. Further, many of the H-bond interactions seen in the Omicron variant complex were lost in the Revertant complex (Fig. 5, Supp. Table 1). However, the van der Waals interaction was increased in the Revertant ACE2-S1-RBD complex (−70.99 ± 5.77 kcal/mol) compared to either the WT (−63.42 ± 7.83 kcal/mol) or the Omicron variant (−67.62 ± 6.51 kcal/mol) ACE2-S1-RBD complex (Fig. 6A, Supp. Fig. 4). Furthermore, salt bridge analysis revealed that the interfacial salt bridge interactions observed in the Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD complex (E37, E35 and D38 residues in ACE2 and R493 residue in S1-RBD) were lost in the Revertant complex (Fig. 5A,D-F), although certain new intrachain salt bridge interactions were formed such as between E516 and R357 residues in the S1-RBD (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that the Q493R mutation in the Omicron variant ACE2-S1-RBD complex drives the enhanced interaction between ACE2 and S1-RBD. While these results suggest that the Q493R mutation as the driver for the increased interaction in the Omicron variant S1-RBD, we note that this mutation may not be the sole reason behind the increased affinity of the Omicron variant S1-RBD for ACE2. As certain interactions that were observed in the Omicron variant S1-RBD such as the H-bond between D335 in ACE2 and T500 in S1-RBD, few salt bridges E340:K356, D398:K386, D467:R454, E406:R403 and D405:R408 remained preserved in the ACE2-Revertant S1-RBD complex. Interestingly, free energy change (ΔG) calculations showed an increased affinity of the Revertant S1-RBD (−50.6 ± 11.40) compared to the Omicron (−43.80 ± 12.00) (one-way ANOVA using the Dunnett’s multiple comparison test adjusted p-value = 0.0418 for Omicron vs Revertant (Omicron+Q493) (Fig. 6A). To gain insight into the underlying mechanism, we focussed our attention on the interfacial residues and calculated the pair-wise residue distances that form the ACE2-S1-RBD interface. This included 25 residues in ACE2 and 22 residues in S1-RBD resulting in overall 550 interfacial residue pairs at the interface. The analysis method was adopted from our previous study[29] as follows: the average distance (mean) and standard deviation of each residue pair across the 5000 trajectory frames were calculated for WT, Omicron and Revertant. The respective standard deviation (averaged over all 3 MD simulation runs) was normalized with the mean distances for each residue pair over three MD simulation runs. Finally, the ratio of the standard deviations obtained for interfacial residue distances for Omicron/WT complex and Revertant/WT complex we compared. A value lesser than 1 indicated decreased interfacial distance fluctuation, suggesting a stabilizing effect at the ACE2-S1-RBD interface (Fig. 6B). The heat maps revealed that the Revertant showed a relatively lesser fluctuation compared to the Omicron. This likely is a manifestation of the greater free energy change observed with the Revertant complex. Interestingly, the stabilizing effect in the Revertant complex were prominent with the residues that were sequentially near to the Q493 residue (R498, T500, N501, G502, V503) and few residues that were structurally closer (V445 and L455) (Fig. 6B). Overall, the structural analysis shows a broad stabilizing spanning over the entire interface in Revertant whereas Omicron shows increased interactions clustered at certain areas at the interface (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, this analysis elaborates potential mechanism underlying the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron lineages to BA.4, BA.5, BA.2.75, BQ.1 and XBB reverting R493Q mutation.

Fig. 6.

Reversal of R493Q mutation in Omicron stabilizes the ACE2-S1-RBD interface. (A) Graphs showing mean H-bonds, non-covalent interaction energy and free energy change (ΔG) in WT, Omicron and Revertant (Omicron+Q493) complexes across three independent MD simulations (mean ± S.D.). Note the decrease in the H-bond and electrostatic interaction in the Revertant (Omicron+Q493) complex compared to the Omicron complex. Additionally, observe the decrease in ΔG of Revertant (Omicron+Q493) in comparison to Omicron. All the triplicate data were validated with one-way ANOVA using the Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and adjusted p value for Omicron vs WT, Omicron vs Revertant (Omicron+Q493) and WT vs Revertant (Omicron+Q493) (B) Heatmap showing the ratio of the inter-residue distance fluctuation in the Omicron/WT and Revertant (Omicron+Q493)/WT ACE2-S1-RBD complexes. An overall decreased interfacial dynamic of the Revertant (Omicron+Q493)/WT is seen especially, shown by the neighboring residues adjacent to the Q493 and few others indicating a stabilizing effect of the reversion R493Q. (C) Schematic showing interfacial residues displaying reduced dynamics in the Omicron (left panel) and the Revertant (Omicron+Q493) complex.

4. Conclusion

To conclude, the structural analysis of the Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD complex performed here combining molecular modelling and MD simulations provides a mechanistic insight into the vital role of unique Q493R mutation at the interface and enhanced binding of the Revertant variant compared to the Omicron S1-RBD. Specifically, we show that the Omicron S1-RBD forms increased number of H-bond, van der Waals and electrostatic interactions with ACE2 compared to the WT S1-RBD (Fig. 6A). Importantly, we demonstrate exceptional role of the unique Q493R mutation in the formation of new highly stable interaction, either H-bond or salt bridge, with the D38, E37 and E35 residue in ACE2 and certain S1-RBD intrachain salt bridges. This is further supported by additional analysis performed using a Revertant (Omicron+Q493) S1-RBD that showed loss of H-bond and salt bridges that were prominent in Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD complex. Interestingly, despite the loss of several covalent and non-covalent interactions the, ΔG calculations showed an enhanced free energy of the Revertant ACE2-S1-RBD complex compared to the Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD complex (Fig. 6A). The above observation suggests that the driving factor must be linked to the interfacial dynamic fluctuation associated with the protein-protein interaction entropy changes. The pair-wise inter-residue distance calculations performed at the interface revealed a decrease in the interfacial residue interaction of Revertant ACE2-S1-RBD complex compared to the Omicron ACE2-S1-RBD complex at the interface (Fig. 6B). These results are in line with the similar studies that provide a deeper insights for the prevalence of two Omicron lineages 22 A & 22B (BA.4 & BA.5) and newly emerging 22D (BA.2.75), 22E (BQ.1), 22 F (XBB) without the Q493R mutation.[71], [72] Studies have reported sub-nanomolar affinity of BA.2.75 (KD = 0.45 nM), BA.2 with R493Q (KD = 0.55 nM), Alpha (KD =1.5 nM), BA4/5 (KD = 2.4 nM), BA.2 with R493 (KD = 4.0 nM), Wuhan (KD = 7.3 nM), BA/1 (KD = 7.8 nM) indicating an increase in affinity to the ACE2 receptor with variants harboring R493Q mutation.[73], [74] We also note that the Revertant Omicron BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5 subvariants has also been reported to possess increased immune evasion capability compared to the Omicron variant [74], [75], [76]. We believe that the insights gained from the current study will aid in understanding the mechanism of increased binding of the Omicron S1 spike protein and thus, in understanding the increased rate of transmission of the variants [77], [78] besides the possibility of aiding in the development of improved therapeutic inhibitors of S1 spike protein-ACE2 interaction such as synthetic peptides and proteins.[4], [79], [80], [81], [82].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

K.H.B. conceived the experiments. A.M.P., W.S.A, and K.H.B. performed experiments, analyzed data, prepared figure panels, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by an internal funding from the College of Health & Life Sciences, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, a member of the Qatar Foundation. A.M.P. and W.A. are supported by scholarships from the College of Health & Life Sciences, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, a member of the Qatar Foundation. Some of the computational research work reported in the manuscript were performed using high-performance computer resources and services provided by the Research Computing group in Texas A&M University at Qatar. Research Computing is funded by the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development (http://www.qf.org.qa).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.02.019.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

References

- 1.Leung N.H.L. Transmissibility and transmission of respiratory viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(8):528–545. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00535-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehman M.Fu, Fariha C., Anwar A., Shahzad N., Ahmad M., Mukhtar S., et al. Novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: a recent mini review. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:612–623. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeller M., Gangavarapu K., Anderson C., Smither A.R., Vanchiere J.A., Rose R., et al. Emergence of an early SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the United States. Cell. 2021;184(19):4939–4952. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.030. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Rienzo L., Monti M., Milanetti E., Miotto M., Boffi A., Tartaglia G.G., et al. Computational optimization of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 for SARS-CoV-2 Spike molecular recognition. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:3006–3014. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581(7807):215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q., Wang Y., Leung E.L., Yao X. In silico study of intrinsic dynamics of full-length apo-ACE2 and RBD-ACE2 complex. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:5455–5465. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;183(6):1735. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J., Maschietto F., Guberman-Pfeffer M.J., Reiss K., Allen B., Xiong Y., et al. Computational insights into the membrane fusion mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 at the cellular level. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:5019–5028. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/. December 2, 2021.

- 11.Spratt A.N., Kannan S.R., Woods L.T., Weisman G.A., Quinn T.P., Lorson C.L., et al. Evolution, correlation, structural impact and dynamics of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:3799–3809. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alpert T., Brito A.F., Lasek-Nesselquist E., Rothman J., Valesano A.L., MacKay M.J., et al. Early introductions and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 in the United States. Cell. 2021;184(10):2595–2604. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.061. e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostrov D.A., Knox G.W. Emerging mutation patterns in SARS-CoV-2 variants. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;586:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tegally H., Wilkinson E., Martin D., Moir M., Brito A., Giovanetti M., et al. Continued emergence and evolution of omicron in South Africa: new BA.4 and BA.5 lineages. medRxiv. 2022 2022.05.01.22274406. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Wu Y.N., Zhang S., Kang X.P., Jiang T. Deep learning based on biologically interpretable genome representation predicts two types of human adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Brief Bioinforma. 2022;23(3) doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.https://covid19-country-overviews.ecdc.europa.eu/index.html. 2022.

- 17.Sun Y., Lin W., Dong W., Xu J. Origin and evolutionary analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. J Biosaf Biosecur. 2022;4(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jobb.2021.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller N.L., Clark T., Raman R., Sasisekharan R. Insights on the mutational landscape of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant receptor-binding domain. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3(2) doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakur V., Ratho R.K. OMICRON (B.1.1.529): a new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern mounting worldwide fear. J Med Virol. 2022;94(5):1821–1824. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colman E., Puspitarani G.A., Enright J., Kao R.R. Ascertainment rate of SARS-CoV-2 infections from healthcare and community testing in the UK. J Theor Biol. 2023;558 doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2022.111333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Focosi D., Novazzi F., Genoni A., Dentali F., Gasperina D.D., Baj A., et al. Emergence of SARS-COV-2 spike protein escape mutation Q493R after treatment for COVID-19. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(10):2728–2731. doi: 10.3201/eid2710.211538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guigon A., Faure E., Lemaire C., Chopin M.C., Tinez C., Assaf A., et al. Emergence of Q493R mutation in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein during bamlanivimab/etesevimab treatment and resistance to viral clearance. J Infect. 2021;84:248–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donzelli S., Spinella F., di Domenico E.G., Pontone M., Cavallo I., Orlandi G., et al. Evidence of a SARS-CoV-2 double Spike mutation D614G/S939F potentially affecting immune response of infected subjects. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:733–744. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann M., Krüger N., Schulz S., Cossmann A., Rocha C., Kempf A., et al. The Omicron variant is highly resistant against antibody-mediated neutralization: Implications for control of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cell. 2022;185(3):447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.032. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannar D., Saville J.W., Zhu X., Srivastava S.S., Berezuk A.M., Tuttle K.S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: antibody evasion and cryo-EM structure of spike protein-ACE2 complex. Science. 2022;375:760–764. doi: 10.1126/science.abn7760. eabn7760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han P., Li L., Liu S., Wang Q., Zhang D., Xu Z., et al. Receptor binding and complex structures of human ACE2 to spike RBD from omicron and delta SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2022;185:630–640.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rath S.L., Padhi A.K., Mandal N. Scanning the RBD-ACE2 molecular interactions in Omicron variant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;592:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russo G., Di Salvatore V., Sgroi G., Parasiliti Palumbo G.A., Reche P.A., Pappalardo F. A multi-step and multi-scale bioinformatic protocol to investigate potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine targets. Brief Bioinforma. 2021;23(1) doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed W.S., Philip A.M., Biswas K.H. Decreased interfacial dynamics caused by the N501Y mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike:ACE2 complex. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.846996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian F., Tong B., Sun L., Shi S., Zheng B., Wang Z., et al. N501Y mutation of spike protein in SARS-CoV-2 strengthens its binding to receptor ACE2. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.69091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barton M.I., MacGowan S.A., Kutuzov M.A., Dushek O., Barton G.J., van der Merwe P.A. Effects of common mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD and its ligand, the human ACE2 receptor on binding affinity and kinetics. eLife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.70658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodcroft E.B., et al. Emergence and spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03677-y. 2020.10.25.20219063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mondeali M., Etemadi A., Barkhordari K., Mobini Kesheh M., Shavandi S., Bahavar A., et al. The role of S477N mutation in the molecular behavior of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: an in-silico perspective. J Cell Biochem. 2023 doi: 10.1002/jcb.30367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh T.-Y., Contreras G.P. Tajima D test accurately forecasts omicron / COVID-19 outbreak. medRxiv. 2021 2021.12.02.21267185. [Google Scholar]

- 35.https://covariants.org/shared-mutations. December 2, 2021.

- 36.Lam S.D., et al. Insertions in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike N-Terminal Domain May Aid COVID-19 Transmission. bioRxiv. 2021 2021.12.06.471394. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah M., Ahmad B., Choi S., Woo H.G. Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD are responsible for stronger ACE2 binding and poor anti-SARS-CoV mAbs cross-neutralization. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:3402–3414. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams A.H., Zhan C.G. Generalized methodology for the quick prediction of variant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binding affinities with human angiotensin-converting enzyme ii. J Phys Chem B. 2022;126(12):2353–2360. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c10718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cameroni E., Saliba C., Bowen J.E., Rosen L.E., Culap K., Pinto D., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu L., et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04388-0. 2021.12.14.472719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roy U. Comparative structural analyses of selected spike protein-RBD mutations in SARS-CoV-2 lineages. Immunol Res. 2022;70(2):143–151. doi: 10.1007/s12026-021-09250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roy U. Molecular investigations of selected spike protein mutations in SARS-CoV-2: delta and omicron variants and omicron subvariants. bioRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.3390/pathogens13010010. 2022.05.25.493484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mannar D., Saville J.W., Zhu X., Srivastava S.S., Berezuk A.M., Zhou S., et al. Structural analysis of receptor binding domain mutations in SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern that modulate ACE2 and antibody binding. Cell Rep. 2021;37(12) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beidler I., Robb C.S., Vidal-Melgosa S., Zühlke M.K., Bartosik D., Solanki V., et al. Structural analysis of Spike proteins from SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern highlighting their functional alterations. Future Virol. 2022;17(10):723–732. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2022-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biswas K.H., Shenoy A.R., Dutta A., Visweswariah S.S. The evolution of guanylyl cyclases as multidomain proteins: conserved features of kinase-cyclase domain fusions. J Mol Evol. 2009;68(6):587–602. doi: 10.1007/s00239-009-9242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saha S., Biswas K.H., Kondapalli C., Isloor N., Visweswariah S.S. The linker region in receptor guanylyl cyclases is a key regulatory module: mutational analysis of guanylyl cyclase C. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(40):27135–27145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed W.S., Geethakumari A.M., Biswas K.H. Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5): structure-function regulation and therapeutic applications of inhibitors. Biomed Pharm. 2021;134 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biswas K.H., Groves J.T. A microbead supported membrane-based fluorescence imaging assay reveals intermembrane receptor-ligand complex dimension with nanometer precision. Langmuir. 2016;32(26):6775–6780. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b01377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Biswas K.H., Zhongwen C., Dubey A.K., Oh D., Groves J.T. Multicomponent supported membrane microarray for monitoring spatially resolved cellular signaling reactions. Adv Biosyst. 2018;2(4) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581(7807):215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eswar N., Eramian D., Webb B., Shen M.Y., Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;426:145–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laskowski R.A., MacArthur M.W., Moss D.S., Thornton J.M. PROCHECK - a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16) doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. 1781-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Best R.B., Zhu X., Shim J., Lopes P.E., Mittal J., Feig M., et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(9):3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Altamash, T., et al., Intracellular Ionic Strength Sensing Using NanoLuc. International journal of molecular sciences. 22(2): p. E677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Wu L., Peng C., Yang Y., Shi Y., Zhou L., Xu Z., et al. Exploring the immune evasion of SARS-CoV-2 variant harboring E484K by molecular dynamics simulations. Brief Bioinforma. 2021;23(1) doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmed W.S., Philip A.M., Biswas K.H. Decreased interfacial dynamics caused by the N501Y mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 S1 Spike:ACE2 complex. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.846996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ribeiro J.V., Bernardi R.C., Rudack T., Stone J.E., Phillips J.C., Freddolino P.L., et al. QwikMD - integrative molecular dynamics toolkit for novices and experts. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26536. doi: 10.1038/srep26536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J.D., Impey R.W., Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79(2):926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Altamash T., Ahmed W., Rasool S., Biswas K.H. Intracellular ionic strength sensing using nanoLuc. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms22020677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brielle E.S., Arkin I.T. Quantitative analysis of multiplex h-bonds. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142(33):14150–14157. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c04357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chiang H., Robinson L.C., Brame C.J., Messina T.C. Molecular mechanics and dynamics characterization of an in silico mutated protein: a stand-alone lab module or support activity for in vivo and in vitro analyses of targeted proteins. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2013;41(6):402–408. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kollman P.A., Massova I., Reyes C., Kuhn B., Huo S., Chong L., et al. Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33(12):889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yan F.-F., Gao F. Comparison of the binding characteristics of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 RBDs to ACE2 at different temperatures by MD simulations. Brief Bioinforma. 2021;22(2):1122–1136. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu H., Hou T. Vol. 32. 2016. CaFE: a tool for binding affinity prediction using end-point free energy methods; pp. 2216–2218. (Bioinformatics). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cosar B., Karagulleoglu Z.Y., Unal S., Ince A.T., Uncuoglu D.B., Tuncer G., et al. SARS-CoV-2 mutations and their viral variants. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021;63:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2021.06.001. S1359-6101(21)00053-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang R., Zhang Q., Ge J., Ren W., Zhang R., Lan J., et al. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 variant mutations reveals neutralization escape mechanisms and the ability to use ACE2 receptors from additional species. Immunity. 2021;54(7):1611–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.06.003. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greaney A.J., Starr T.N., Barnes C.O., Weisblum Y., Schmidt F., Caskey M., et al. Mapping mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD that escape binding by different classes of antibodies. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4196. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cao Y., Yisimayi A., Jian F., Song W., Xiao T., Wang L., et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron infection. Nature. 2022;608(7923):593–602. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04980-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Q., Iketani S., Li Z., Liu L., Guo Y., Huang Y., et al. Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants. Cell. 2023;186(2):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.018. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huo J., Dijokaite-Guraliuc A., Liu C., Zhou D., Ginn H.M., Das R., et al. A delicate balance between antibody evasion and ACE2 affinity for Omicron BA.2.75. Cell Rep. 2022;42 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tuekprakhon A., Nutalai R., Dijokaite-Guraliuc A., Zhou D., Ginn H.M., Selvaraj M., et al. Antibody escape of SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.4 and BA.5 from vaccine and BA.1 serum. Cell. 2022;185(14):2422–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.005. e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park Y.-J., Pinto D., Walls A.C., Liu Z., De Marco A., Benigni F., et al. Imprinted antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 omicron sublineages. Science. 2022;378(6620):619–627. doi: 10.1126/science.adc9127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hachmann N.P., Miller J., Collier A.Y., Ventura J.D., Yu J., Rowe M., et al. Neutralization Escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(1):86–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2206576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bansal K., Kumar S. Mutational cascade of SARS-CoV-2 leading to evolution and emergence of omicron variant. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2022.198765. 2021.12.06.471389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zahradnik J., et al. Receptor binding and escape from Beta antibody responses drive Omicron-B.1.1.529 evolution. bioRxiv. 2021 2021.12.03.471045. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yin J., Li C., Ye C., Ruan Z., Liang Y., Li Y., et al. Advances in the development of therapeutic strategies against COVID-19 and perspectives in the drug design for emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:824–837. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lim H., Jeon H.N., Lim S., Jang Y., Kim T., Cho H., et al. Evaluation of protein descriptors in computer-aided rational protein engineering tasks and its application in property prediction in SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:788–798. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu C.H., Lu C.H., Lin L.T. Pandemic Strategies with Computational and Structural Biology against COVID-19: A Retrospective. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scott T.A., Supramaniam A., Idris A., Cardoso A.A., Shrivastava S., Kelly G., et al. Engineered extracellular vesicles directed to the spike protein inhibit SARS-CoV-2. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2022;24:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.