Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the major etiologic agents of brain abscesses in humans, occasionally leading to focal neurological deficits and even death. The objective of the present study was to identify key virulence determinants contributing to the pathogenesis of S. aureus in the brain using a murine brain abscess model. The importance of virulence factor production in disease development was demonstrated by the inability of heat-inactivated S. aureus to induce proinflammatory cytokine or chemokine expression or brain abscess formation in vivo. To directly address the contribution of virulence determinants in brain abscess development, the abilities of S. aureus strains with mutations in the global regulatory loci sarA and agr were examined. An S. aureus sarA agr double mutant exhibited reduced virulence in vivo, as demonstrated by attenuated proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression and bacterial replication. Subsequent studies focused on the expression of factors that are altered in the sarA agr double mutant. Evaluation of an alpha-toxin mutant revealed a phenotype similar to that of the sarA agr mutant in vivo, as evidenced by lower bacterial burdens and attenuation of cytokine and chemokine expression in the brain. This suggested that alpha-toxin is a central virulence determinant in brain abscess development. Another virulence mechanism utilized by staphylococci is intracellular survival. Cells recovered from brain abscesses were shown to harbor S. aureus intracellularly, providing a means by which the organism may establish chronic infections in the brain. Together, these data identify alpha-toxin as a key virulence determinant for the survival of S. aureus in the brain.

Staphylococcus aureus is a potent and versatile pathogen of humans. The frequencies of both nosocomial and community-acquired staphylococcal infections have increased steadily over the years (22). In addition, treatment of these infections has become more challenging due to the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains (8, 29). S. aureus infection may be manifested in a wide variety of forms, including focal abscesses, arthritis, endocarditis, and septicemia. Moreover, S. aureus has a diverse arsenal of virulence factors that contribute to the pathogenesis of disease. These can be broadly subdivided into surface and extracellular secreted proteins. Surface proteins include both structural components of the bacterial cell wall, such as peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid, and surface proteins preferentially expressed during exponential growth, including protein A, fibronectin-binding protein, and clumping factor. Secreted proteins are generally elaborated during the stationary phase of bacterial growth and include such proteins as alpha-toxin, enterotoxin B, lipase, and V8 protease.

The differential regulation of surface and extracellular virulence factors during the growth of S. aureus is controlled by at least three global regulatory systems, including sarA, agr, and sae (4, 10, 20). The sarA locus is involved in the expression of exoproteins and cell wall proteins that are potential virulence determinants in experimental infections (4, 6, 13). The agr locus up-regulates the production of extracellular proteins while repressing the synthesis of surface proteins (20, 24, 27, 28). The sae regulatory locus activates the production of several exoproteins, including alpha- and beta-toxin, coagulase, and protein A (10). As an alternative to dealing with antibiotic-resistant strains, the effective targeting and inactivation of these global regulatory loci could have a profound impact on disease therapy. Therefore, an understanding of the host response to S. aureus global regulatory mutants in complex disease models may reveal the importance of key virulence determinants in disease progression.

One virulence mechanism utilized by staphylococci is intracellular survival (21). The intracellular environment protects staphylococci from host defense mechanisms as well as the bactericidal effects of antibiotics. Intracellular survival of S. aureus has been demonstrated in both epithelial cells and neutrophils (12, 16). Staphylococci also produce cytotoxins, such as alpha-toxin, which cause pore formation and induce proinflammatory changes in mammalian cells (11, 30). Both the intracellular survival of S. aureus and the production of virulence factors, such as alpha-toxin, most probably play an important role in the complex response to S. aureus in the host.

In this study we have utilized a murine experimental brain abscess model using S. aureus, one of the major etiologic agents of brain abscesses in humans (23, 31). The course of brain abscess progression in the rodent model closely parallels what is observed in human disease in terms of histological appearance, infiltrating leukocytes, and chronicity (7, 19). Therefore, evaluating the role of bacterial virulence determinants and the host immune response to S. aureus in this model system should approximate conditions encountered during human disease. We have previously demonstrated that S. aureus induces rapid and sustained expression of numerous proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in both the rat (18) and mouse (19) brain abscess models. However, the role of bacterial virulence factors in the expression of these mediators remains to be defined.

The present study was designed to examine the role of S. aureus virulence determinants in brain abscess development. The results demonstrate that staphylococcal strains that lack both the sarA and agr global regulatory loci or alpha-toxin exhibit reduced virulence in vivo. Examination of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression revealed that although both sarA agr and alpha-toxin mutants are capable of inducing mediator expression during the acute phase of infection, this response is rapidly attenuated compared to the strong and sustained expression detected in response to isogenic strains. Moreover, cells recovered from brain abscesses were found to harbor S. aureus intracellularly, providing a mechanism by which this organism can establish chronicity and antibiotic resistance, both features of human central nervous system (CNS) abscesses. These results reveal the importance of S. aureus-derived virulence factors, in particular alpha-toxin, in brain abscess development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Male AKR/J mice 6 to 8 weeks of age were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). The animal use protocol has been approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and is in accord with National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of rodents.

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All of the mutants utilized were derived from the S. aureus strain RN6390.

TABLE 1.

S. aureus strains used in this study

| Strain designation | Genotype | Antibiotic resistance |

|---|---|---|

| ALC132 | RN6390 isogenic strain | None |

| ALC136 | sarA mutant | Ermr |

| ALC134 | agr mutant | Tetr |

| ALC135 | sarA agr double mutant | Ermr Tetr |

| ALC837 | Alpha-toxin | Ermr |

| ALC812 | Lipase-negative | Ermr Tetr |

Preparation of S. aureus-laden agarose beads.

Live S. aureus cells were encapsulated in agarose beads prior to implantation in the brain as previously described (18, 19). The use of agarose beads prevents bacterial dissemination or rapid wound sterilization by the host. Briefly, bacterial strains were grown to postexponential phase at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.). A total of 109 bacteria were added to a solution of 1.4% low-melting-point agarose (type XII; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 40°C. The mixture was then added to rapidly swirling heavy mineral oil (Sigma) prewarmed to 37°C and quickly cooled to 0°C on crushed ice. Beads were washed four times in 1× Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Mediatech Cellgro, Herndon, Va.) to remove mineral oil. Beads with diameters between 50 and 100 μm, as determined by phase-contrast microscopy, were used for implantation into the brain. Heat-inactivated bacteria were prepared by incubating organisms for 1 h at 56°C prior to encapsulation. The bacterial viability or sterility of bead preparations was confirmed by overnight culture in BHI medium and quantitative culture on blood agar plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.).

Induction of experimental brain abscesses.

Mice were anesthetized with avertin (z-z-z-tribromoethanol) intraperitoneally, and a 1-cm longitudinal incision was made along the vertex of the skull extending from the ear to the eye, exposing the frontal sutures. A burr hole was drilled 1 mm anterior and 1 mm lateral to the frontal suture of the calvarium. A Hamilton syringe fitted with flexible tubing and a pulled, fine-tipped glass micropipette (diameter < 0.1 mm) was used to deliver beads into the brain parenchyma. A total of 3 μl of beads (105 CFU) was slowly infused 3 mm deep from the external surface of the calvarium to prevent reflux during injection. Using this approach, bacteria were reproducibly deposited into the head of the caudate or adjacent frontal lobe white matter. To collect brain abscess tissues for analysis, lesion sites were demarcated by the stab wound created during injections. Brain tissues were sectioned 0.5 mm on all sides of the stab wound, and cortical material was removed in order to focus on changes occurring in the white matter. Previous studies have established that implantation of agarose beads alone induces minimal proinflammatory cytokine or chemokine expression or cellular infiltration, indicating that neither the stab wound nor the deposition of foreign material (agarose beads) induces inflammatory changes in the brain (18, 19). The mortality rate associated with brain abscess induction was minimal, with >95% of animals surviving the procedure.

Quantification of viable bacteria associated with brain abscesses in vivo.

To quantify the numbers of viable bacteria associated with brain abscesses in vivo, homogenates were prepared by disrupting brain abscess tissues (consisting of both solid tissue and purulent material) in 0.5 ml of DPBS supplemented with a complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.). Serial 10-fold dilutions of homogenates were plated onto blood agar plates (Becton Dickinson). Titers were calculated by enumerating colony growth and are expressed as the mean log10 CFU per milliliter of homogenate.

Immunohistochemistry.

To prepare tissues for immunohistochemistry, animals were perfusion fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The brain was removed, postfixed in paraformaldehyde for 30 min, and washed in 0.2 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, overnight. Tissues were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for 24 h and then snap frozen at the optimal cutting temperature for immunohistochemistry.

Frozen sections of fixed tissues were processed for immunohistochemistry using the avidin-peroxidase method as previously described (14). The following antibodies were used for analysis: anti-GR-1 (neutrophil-specific); anti-CD11b, which reacts with the beta-integrin subunit expressed on neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and microglia; and the isotype control antibody rat immunoglobulin G2b (all from BD PharMingen). Sections were then incubated with a biotinylated secondary anti-rat immunoglobulin G antibody (Vector Laboratories) and developed using the substrate 3,3′-diaminobenzidene.

Isolation of cells from brain abscesses.

Brain abscesses were collected from animals at days 5 and 7 following bacterial exposure to recover infiltrating and resident cells for gentamicin protection assays. Briefly, mice were perfused transcardially with DPBS to eliminate intravascular leukocytes. Tissue blocks containing the brain abscesses were pooled, minced into fine pieces using forceps, and incubated with collagenase type II (final concentration, 1 mg/ml; Sigma) for 20 min at 37°C. The resulting cell suspension was layered onto a discontinuous Percoll gradient (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) to separate myelin debris from cells. Cells were washed twice with 1× DPBS, and viability was determined by using trypan blue exclusion dye analysis.

Gentamicin protection assay.

To determine whether cells recovered from brain abscesses harbored viable S. aureus intracellularly, gentamicin protection assays were performed. The S. aureus parental strain used in this study, RN6390, is sensitive to gentamicin and rifampin (T. Kielian, unpublished observations). Gentamicin kills extracellular S. aureus, but because its ability to permeate the eukaryotic cell membrane is limited, intracellular organisms are protected from its bactericidal activity. Following the isolation of cells from brain abscesses, an aliquot of cells was taken to determine the total bacterial titer (extra- plus intracellular organisms). In addition, cells were treated with gentamicin (100 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C to kill extracellular organisms. After 2 h, cells were washed twice to remove the gentamicin and serial dilutions of each treatment were performed to determine bacterial titers (log10 CFU). To ensure that intracellular bacteria were sensitive to an antibiotic which can penetrate mammalian cell membranes, cells were incubated with rifampin (1 mg/ml), which effectively reduced the number of intracellular CFU.

RPA.

Cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in brain abscess tissues were examined by RNase protection assay (RPA) using the RiboQuant RPA kit (BD PharMingen). The multiprobe template sets used for analysis include mCK-2, mCK-3b, and mCK-5. All template sets contain probes for the housekeeping genes L32 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, which serve as internal controls for the assay. Probes were synthesized using [α-33P]UTP, resulting in an average specific activity of 4 × 106 cpm/μl. RPA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, using 10 μg of total RNA per sample. Products were resolved on a 6% acrylamide gel, dried, and exposed to film (BioMax MR; Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

Statistics.

Significant differences between experimental groups were determined by using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test at the 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

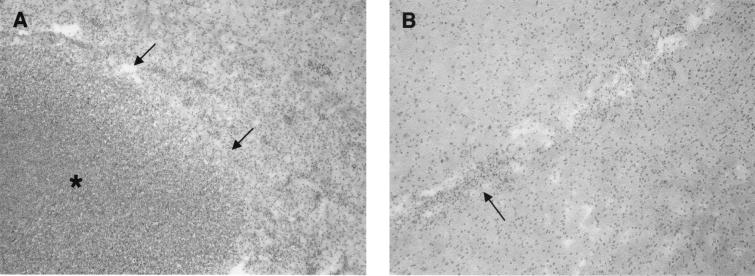

Brain abscesses are induced by live, but not heat-inactivated, S. aureus

To determine whether brain abscess formation requires ongoing bacterial replication and/or the production of extracellular virulence factors, the ability of heat-inactivated bacteria to induce abscesses was examined. An advantage of using heat-inactivated organisms as the inflammatory stimulus is that the contribution of an evolving or resolving infectious process can be eliminated. In addition, virulence factors are not produced by heat-inactivated organisms, allowing the direct assessment of the importance of these mediators in abscess pathogenesis. Heat inactivation of S. aureus was confirmed by the inability of organisms to grow in BHI medium or on blood agar plates (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 1A, animals receiving live S. aureus developed large brain abscesses associated with a significant neutrophil and mononuclear cell infiltrate. In contrast, there was no evidence of abscess formation or any cellular infiltrates in those animals receiving heat-inactivated S. aureus (Fig. 1B). To determine whether the inability of heat-inactivated organisms to induce abscess formation was related to the number of bacteria inoculated into the brain, animals were challenged with 1-log-greater numbers of heat-inactivated S. aureus. Even increasing the number of heat-inactivated bacteria by 1 log was not sufficient to induce abscess formation (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Brain abscesses are induced by live, but not heat-inactivated, S. aureus. Mice were implanted with live (A) or heat-inactivated (B) encapsulated organisms as described in Materials and Methods. Animals were euthanized 7 days later, and brain lesions were collected for histological analysis. Brain tissues (5-μm sections) were stained using hematoxylin and eosin to reveal changes in tissue architecture. (A) Note the formation of a large, well-demarcated abscess in the animal which received live S. aureus. The arrows delineate the margin between surrounding brain parenchyma and the abscess, which is denoted by an asterisk. (B) The arrow denotes a small inflammatory focus associated with the stab wound created during the injection of heat-inactivated organisms. Results presented in both panels are representative of three independent experiments. Original magnification, ×22.5.

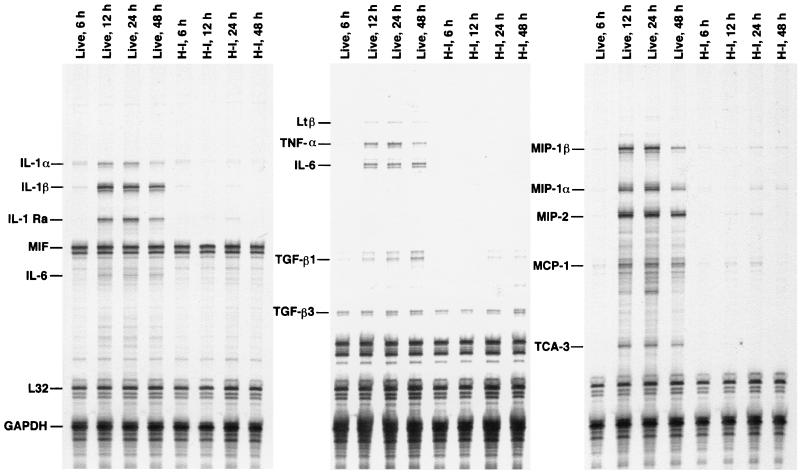

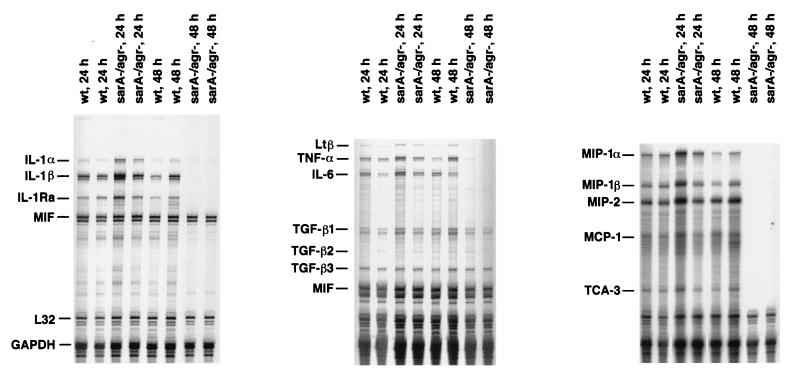

We have previously demonstrated that live S. aureus induces the rapid and sustained expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the brain (18, 19). The inability of heat-inactivated organisms to induce abscess formation suggested that their ability to initiate proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production might be impaired. Indeed, both proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine induction in the brain was significantly attenuated in those animals receiving heat-inactivated compared to live organisms (Fig. 2). Increasing the number of heat-inactivated organisms inoculated into the brain by 1 log was not sufficient to attain the levels of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression observed in response to live bacteria (data not shown). These results suggest that some factor(s) produced by viable organisms is critical to the induction of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression and brain abscess development.

FIG. 2.

Live, but not heat-inactivated, S. aureus induces potent proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression in the brain. Mice were implanted with live or heat-inactivated (H-I) encapsulated organisms as described in Materials and Methods. Animals were euthanized at the indicated time points, and inoculation sites were collected for RNA extraction and analysis by RPA. The identity of each experimental mRNA is denoted at the left. Results presented are representative of three independent experiments.

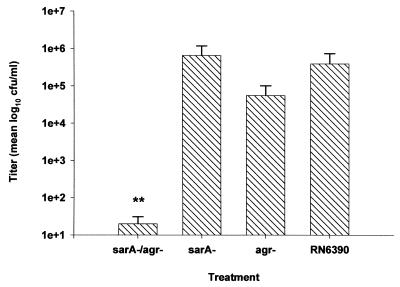

A sarA agr S. aureus global regulatory mutant exhibits reduced virulence in an experimental brain abscess model.

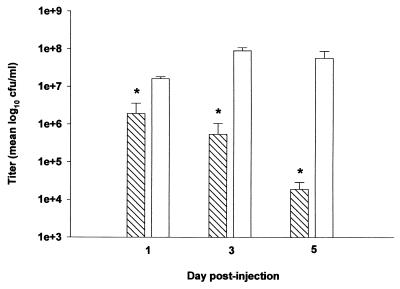

The findings obtained with heat-inactivated organisms suggested that S. aureus produces a virulence factor(s) which participates in brain abscess formation. The sarA and agr global regulatory loci are two major regulators of virulence factor expression in S. aureus. To determine what effect global regulatory loci play in brain abscess development, the ability of a sarA, agr, and sarA agr double mutant to induce disease was examined. Since each global regulatory loci mutant displays a particular virulence factor phenotype, analysis of each mutant would allow identification of a smaller subset of specific factors for further examination. The replication of a sarA agr double mutant was markedly attenuated compared to its isogenic control strain RN6390 at day 5 following bacterial exposure (Fig. 3). Interestingly, both sarA and agr single mutants replicated to the same extent as RN6390 in the brain parenchyma, suggesting an additive effect by the mutations in both regulatory loci. To determine whether the attenuated virulence of the sarA agr double mutant was related to an inability to replicate versus enhanced bacterial clearance, the kinetics of bacterial replication was evaluated for this mutant. As shown in Fig. 4, the number of viable organisms recovered from the brains of animals inoculated with the sarA agr double mutant was reduced as early as 24 h following bacterial exposure compared to its isogenic strain RN6390. However, the sarA agr double mutant was capable of replication to a limited extent, as evidenced by the small increase in bacterial titers observed at day 3 following bacterial exposure (Fig. 4). By day 5, the number of viable organisms in the brains of animals receiving the sarA agr double mutant was dramatically reduced compared to that in brains of animals receiving the wild type, with 3-log-fewer CFU in the former.

FIG. 3.

Replication of a sarA agr S. aureus mutant is attenuated in the brain. Animals were implanted with either sarA (n = 5), agr (n = 7), or sarA agr (n = 7) mutants or the isogenic strain RN6390 (n = 7) as described in Materials and Methods. Animals were euthanized 5 days following bacterial exposure, and the number of viable organisms in the brain was determined by quantitative culture. Titers are expressed as the mean log10 CFU per milliliter of brain abscess homogenate from three separate experiments. Significant differences are denoted with asterisks (∗∗, P < 0.001). Error bars, standard deviations.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of growth kinetics between the sarA agr and RN6390 strains. Animals were implanted with either the sarA agr double mutant (hatched bars) or RN6390 isogenic strain (open bars) as described in Materials and Methods. Animals (n = 3 to 6 per group) were euthanized at the indicated time points, and the number of viable organisms in the brain was determined by quantitative culture. Titers are expressed as the mean log10 CFU per milliliter of brain abscess homogenate from two separate experiments. Significant differences are denoted with asterisks (∗, P < 0.05). Error bars, standard deviations.

To determine whether the reduced virulence of the sarA agr double mutant correlated with an attenuated host immune response in the brain, proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression was evaluated in animals inoculated with either the sarA agr double mutant or RN6390. Initially, there were no observable differences in the amount of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression elicited by either strain (Fig. 5). However, within 48 h following bacterial exposure, proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression was undetectable in the brains of animals inoculated with the sarA agr double mutant compared to the continued induction in response to its isogenic strain RN6390 (Fig. 5). The cytokine and chemokine response to RN6390 was still detected at days 3 and 5 following bacterial exposure, whereas the response to the sarA agr mutant remained negative (data not shown). Even though bacterial burdens and mediator expression were attenuated in response to the sarA agr double mutant, these animals still developed rudimentary abscesses, albeit the lesions were dramatically smaller compared to those of animals receiving RN6390 (data not shown). This suggests that a virulence factor(s), whose expression is reduced or absent in the sarA agr mutant, must play an important role in the pathogenic response to S. aureus in the brain.

FIG. 5.

Proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression in the brain is attenuated in response to an S. aureus sarA agr double mutant. Mice were implanted with either the sarA agr mutant or RN6390 isogenic strain as described in Materials and Methods. Animals were euthanized at the indicated time points, and inoculation sites were collected for RNA extraction and analysis by RPA. The identity of each experimental mRNA is denoted at the left. Results presented are representative of two independent experiments.

Diminished virulence of an alpha-toxin mutant of S. aureus in experimental brain abscesses.

The reduced virulence of the sarA agr double mutant in the brain suggested that any one of a number of virulence factors could be involved in mediating tissue damage in this model. An important factor, the expression of which is greatly attenuated in the sarA agr double mutant, is alpha-toxin. Previous studies have demonstrated that alpha-toxin expression by the sarA agr double mutant is significantly lower compared to that by either sarA or agr single mutants (5). Alpha-toxin mediates its activity through forming pores in mammalian cell membranes, resulting in cell destruction by osmotic lysis. Because of its importance in other disease models (3, 15, 17), the role of alpha-toxin in brain abscess development was evaluated.

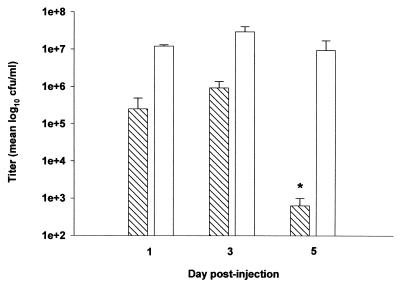

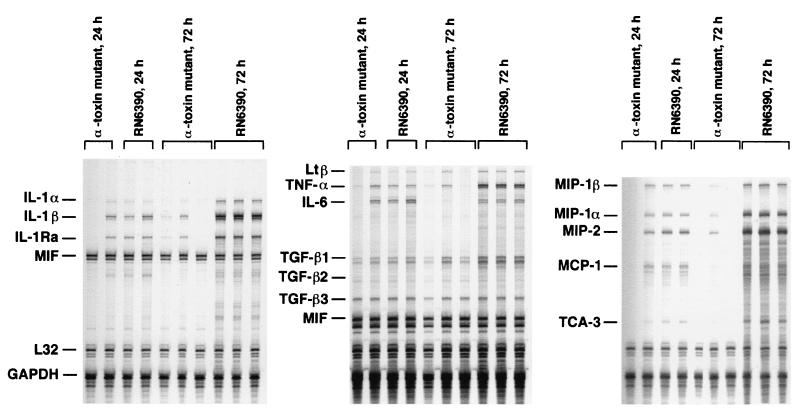

Replication of an S. aureus alpha-toxin mutant was markedly attenuated in the brain compared to that of RN6390, with the number of viable bacteria recovered approximately 3 to 4 logs lower in the former (Fig. 6). To determine whether the reduced virulence of the alpha-toxin mutant correlated with an attenuated host immune response in the brain, proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression was evaluated in animals inoculated with either the alpha-toxin mutant or RN6390. Similar to the results obtained with the sarA agr double mutant, the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines was attenuated in animals receiving the alpha-toxin mutant at 48 h following bacterial exposure (Fig. 7). However, the alpha-toxin mutant was capable of inducing mediator expression as demonstrated by the production of numerous mediators as early as 24 h, but this response was short-lived. The cytokine and chemokine response to RN6390 was still detected at days 3 and 5 following bacterial exposure, whereas the response to the alpha-toxin mutant remained negative (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

The replication of an S. aureus alpha-toxin mutant is attenuated in the brain. Animals were implanted with either the alpha-toxin mutant (hatched bars) or RN6390 isogenic strain (open bars) as described in Materials and Methods. Animals (n = 4 to 6 per group) were euthanized at the indicated time points, and the number of viable organisms in the brain was determined by quantitative culture. Titers are expressed as the mean log10 CFU per milliliter of brain abscess homogenate from two separate experiments. Significant differences are denoted with asterisks (∗, P < 0.05). Error bars, standard deviations.

FIG. 7.

Proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression in the brain is attenuated in response to an S. aureus alpha-toxin mutant. Mice were implanted with either alpha-toxin mutant or RN6390 encapsulated organisms as described in Materials and Methods. Animals were euthanized at the indicated time points, and inoculation sites were collected for RNA extraction and analysis by RPA. The identity of each experimental mRNA is denoted at the left. Results presented are representative of two independent experiments.

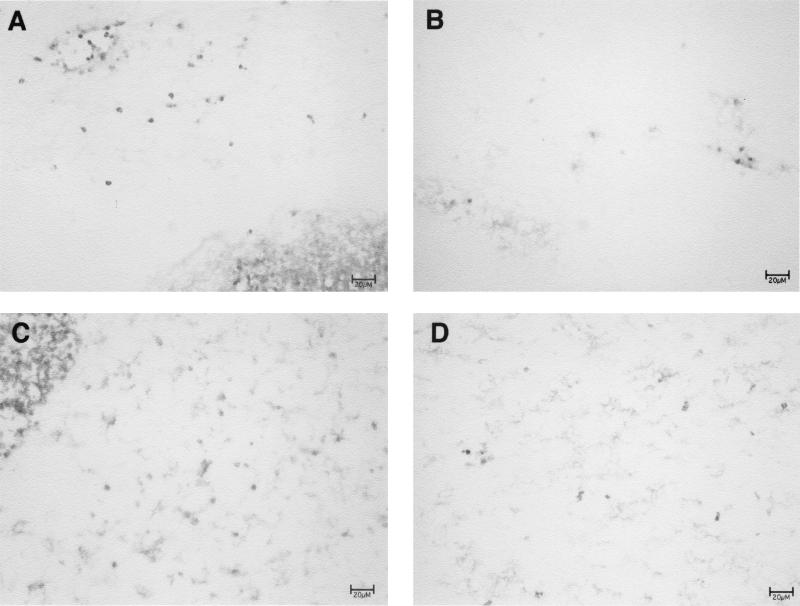

Since both bacterial burdens and proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine responses were attenuated in animals receiving an alpha-toxin mutant, the ability of these organisms to produce brain abscesses was investigated. We were able to detect only small inflammatory foci in the brains of animals inoculated with the alpha-toxin mutant, compared to the large, well-formed abscesses in those mice receiving the isogenic strain RN6390 (Fig. 8). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed a paucity of neutrophils in the brains of animals injected with the alpha-toxin mutant, whereas these cells were the predominant type infiltrating abscesses in response to RN6390 (Fig. 8). Together, these data indicate that alpha-toxin is an important, and possibly pivotal, virulence determinant in CNS abscess formation.

FIG. 8.

An S. aureus alpha-toxin mutant fails to induce abscess formation in the brain. Mice were implanted with either the isogenic strain RN6390 (A and C) or an alpha-toxin mutant (B and D) as described in Materials and Methods. Animals were euthanized at day 7 following bacterial exposure to evaluate brain abscess formation and cellular infiltrates. Serial sections of brain lesions were stained with the neutrophil-specific antibody GR-1 (A and B) or anti-CD11b (C and D), which reacts with neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and resident microglia. Note the outer edge of an abscess in the animal receiving RN6390 (dense staining area in the corners of panels A and C), whereas a well-defined abscess was not detected in response to the alpha-toxin mutant. Results presented are representative of two independent experiments. Bars, 20 μm.

Lipase is not a critical virulence determinant in brain abscess formation.

In our experimental model, brain abscesses are induced in the white matter, which contains a large amount of lipid, namely, myelin. Therefore, we reasoned that bacterial lipase expression might be a key virulence determinant involved in the invasion and spread of bacteria throughout the brain parenchyma. To examine this possibility, the virulence of an S. aureus lipase mutant was evaluated. The growth kinetics of both the lipase mutant and RN6390 were identical (data not shown), suggesting that lipase does not contribute significantly to the virulence of S. aureus in the brain.

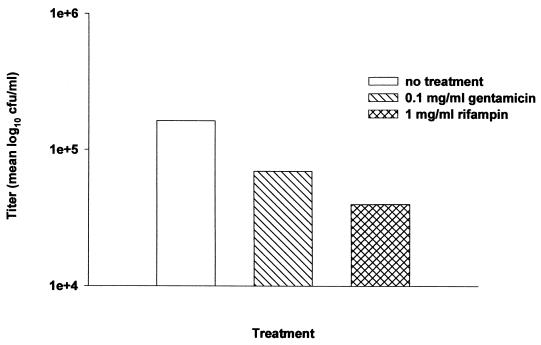

S. aureus survives intracellularly within cells recovered from brain abscesses.

S. aureus has the ability to survive and replicate intracellularly within neutrophils and epithelial cells (12, 16). Currently, it is not known whether bacteria persist within cells associated with brain abscesses. To determine whether cells isolated from abscesses harbor viable S. aureus, gentamicin protection assays were performed on cells recovered from abscesses 5 days following bacterial injection. This time point was selected for evaluation since it is when bacterial loads are maximal or on the decline. Viable bacteria were still detected in abscess-derived cells treated with gentamicin, despite the fact that the antibiotic effectively reduced the overall number of bacteria by elimination of extracellular organisms (Fig. 9). Treatment of cells with rifampin further reduced the number of viable S. aureus cells, demonstrating the sensitivity of bacteria to an antibiotic capable of penetrating mammalian cells, and thus supporting the argument for their probable intracellular location. These findings indicate that S. aureus can survive intracellularly within cells associated with brain abscesses in vivo, providing a mechanism by which this organism can establish chronic infections in the CNS.

FIG. 9.

Abscess-associated cells harbor viable S. aureus intracellularly. Mice were implanted with RN6390-containing agarose beads and euthanized at day 5 following bacterial exposure. Cells were recovered from brain abscesses as described in Materials and Methods, and the presence of intracellular organisms was demonstrated using gentamicin protection assays. An aliquot of cells was taken prior to antibiotic treatment to demonstrate the total number of abscess-associated bacteria. Rifampin was included as a control to verify the susceptibility of intracellular organisms to an antibiotic which can penetrate the mammalian cell membrane. Results are expressed as the mean log10 CFU per milliliter of brain abscess cells and are representative of five independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Staphylococci produce a wide array of virulence determinants that play a role in the complex interactions between the organism and its host. While the in vivo function of these virulence factors is incompletely understood, it is probable that the identification of key factors required for disease progression may lead to novel therapies in the treatment of staphylococcal infections. This study investigates the importance of virulence factors produced by S. aureus in experimental brain abscess development.

To establish whether ongoing bacterial replication and/or virulence factor production was required for brain abscess induction, the response to heat-inactivated organisms was examined. Heat-inactivated S. aureus itself was not sufficient to induce proinflammatory cytokine or chemokine expression or abscess formation in the brain. These findings suggested that the active secretion of a virulence factor(s) was important for disease induction. However, it was also conceivable that brain abscess formation was influenced by structural components of the bacterial cell wall which were limiting in these experiments. To ensure that the inability to induce cytokine or chemokine expression was not merely a result of suboptimal concentrations of cell wall products, we increased the amount of heat-inactivated organisms inoculated into the brain. We were unable to induce significant mediator expression or abscess formation following the introduction of a 1-log-greater number of heat-inactivated organisms, suggesting that virulence factor production is important for brain abscess formation. However, our results cannot discount a potential additive effect between virulence determinants and an increasing mass of cell wall products produced by viable organisms. We are currently evaluating the ability of purified peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid to induce pathology in the brain. Nonetheless, these data suggest an important role for virulence factor expression in the host response to S. aureus in the brain.

To delineate virulence factors which potentially participate in abscess pathogenesis, the growth of S. aureus global regulatory mutants was examined in the brain. Interestingly, an S. aureus sarA agr double mutant was markedly less virulent in vivo, whereas both single mutants behaved similarly to the parental strain RN6390 in terms of bacterial replication and immune activation in the brain. This finding cannot be explained by impaired replication of the sarA agr double mutant, since previous studies have established that its growth rate is identical to that of its isogenic strain RN6390 (5). Additionally, this mutant replicated successfully during the first three days following implantation into the brain. This suggested that virulence factors, the expression of which are dramatically reduced in the sarA agr double mutant, are pivotal for brain abscess induction.

The findings obtained with the sarA agr mutant led us to examine the potential role of two virulence factors, alpha-toxin and lipase, in brain abscess development. Similar to the findings obtained with the sarA agr double mutant, the replication of an alpha-toxin mutant was significantly attenuated compared to that of its isogenic strain RN6390. Importantly, the virulence of a lipase mutant was equivalent to that of its isogenic strain RN6390, indicating that the results obtained with the alpha-toxin mutant were specific. In addition to its impaired replication and enhanced clearance, the alpha-toxin mutant did not induce well-defined abscesses in the brain; rather, minimal inflammation and few infiltrating cells were observed. This finding may be explained by the following. The rapid replication of wild-type S. aureus (RN6390) induces prolonged cytokine and chemokine expression and direct damage to the brain parenchyma by bacterial products, leading to abscess formation. RN6390 produces alpha-toxin, which forms small transmembrane pores spanning the plasma membrane of mammalian cells, leading to osmotic lysis. Secretion of alpha-toxin is an effective way to eliminate infiltrating neutrophils and other leukocytes, cells which play a pivotal role in containing bacterial burdens. The lack of toxin expression in the alpha-toxin mutant now allows more leukocytes to survive in the brain, rapidly reducing bacterial loads. The quick and effective containment of the alpha-toxin mutant in the brain prevents these immune responses and bacteria from persisting, which most likely explains the absence of well-defined abscesses. The striking reduction in virulence associated with the alpha-toxin mutant also indicates that alpha-toxin is the major virulence determinant in the brain and its activity cannot be substituted by the gamma- and delta-toxins which are still produced by this mutant. The finding that animals inoculated with the sarA agr double mutant develop microabscesses can also be explained on the basis of alpha-toxin expression. Although alpha-toxin production is significantly decreased in the sarA agr mutant, some protein is still detected due to induction by other regulatory systems (5). The small amount of alpha-toxin produced by the sarA agr double mutant may be sufficient to transiently compromise the host response, which eventually contains the infection without inducing much damage to the brain parenchyma, resulting in microscopic abscesses. However, it is likely that an additional factor(s) participates in S. aureus infection in the brain since the alpha-toxin mutant was not completely avirulent. Our findings demonstrating the importance of alpha-toxin in the brain are in agreement with others using various model systems (3, 15, 17, 26).

S. aureus induces potent proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression in the brain (18, 19). Since both sarA agr and alpha-toxin mutants exhibited a significant reduction in tissue damage in the brain, we were interested in determining whether this correlated with an attenuation in the host immune response. Both sarA agr and alpha-toxin mutants were initially capable of inducing proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression. However, this response was transient in that mediator production was undetectable 48 h following bacterial exposure, which correlated with a decrease in the numbers of viable organisms in the brain. This suggests that during the initial stage of infection, sufficient organisms are present within the brain parenchyma to trigger activation of host immune responses. However, as the replication of these mutants is rapidly held in check, the immune response begins to diminish. Alternatively, there may be less of a quorum-sensing function to activate hemolysin production as the number of organisms begins to decline. This would, in effect, minimize damage to the surrounding normal brain parenchyma resulting from an overactive immune response which is thought to contribute to abscess severity in response to fully virulent strains of S. aureus.

Work by others has demonstrated a critical role(s) for the agr (1, 9) and sarA (25) loci in regulating S. aureus virulence in vivo. However, our results differ from these studies in that we observed a reduction in virulence only for an S. aureus strain in which both regulatory loci were inactivated. Our findings are in agreement with Cheung et al. who demonstrated diminished virulence of an S. aureus sarA agr double mutant in a rabbit model of endocarditis (5). In addition, Booth et al. also demonstrated that inactivation of both the sarA and agr loci led to near-complete attenuation of virulence in experimental endophthalmitis (2). Our data in experimental brain abscesses suggest that the residual virulence factor expression detected in either the sarA or agr single mutants is sufficient to allow these organisms to replicate and induce tissue pathology similar to wild-type strains. Only the inactivation of both regulatory loci effectively reduces virulence factor expression, effectively compromising bacterial replication and minimizing tissue damage in the brain.

Recently, S. aureus has been demonstrated to survive intracellularly within neutrophils and epithelial cells (12, 16). Therefore, we were interested in identifying whether viable organisms were associated with abscess-derived cells. This virulence mechanism could explain the phenomenon of daughter abscess formation in the brain which occurs in a small percentage of affected individuals. As abscesses evolve, the fibrotic wall surrounding the lesion may become weakened, allowing contents to permeate neighboring tissue and establish a new nidus of infection. This seeding of small microabscesses resembles “beads on a string” and is life-threatening if intraventricular rupture occurs, emptying purulent material into the cerebrospinal fluid. The survival of bacteria within the initial abscess may be a prerequisite for daughter abscess formation. The question remains whether bacteria survive extracellularly or persist within cells associated with brain abscesses. Indeed, we found that cells recovered from brain abscesses harbored viable organisms. However, the identity of these cells is currently not known. One possibility is that S. aureus is contained within neutrophils infiltrating the brain parenchyma. Previous studies have established that neutrophils constitute the majority of cells infiltrating acute brain abscesses (19). However, the half-life of an activated neutrophil is relatively short, which does not fit the profile of a cell that would persist, allowing a daughter abscess to become established. Another possibility is that S. aureus may survive within resident microglia, the resident macrophage population in the brain. We are currently investigating the cellular localization of S. aureus in the brain using a strain that constitutively expresses green fluorescent protein. These studies should allow identification of cells that are capable of supporting bacterial survival in the brain.

In summary, these studies have revealed the central importance of alpha-toxin in brain abscess development. It has been well documented that many immune responses in the CNS are distinct from those observed in peripheral tissues. However, as shown here, the pivotal role of alpha-toxin in the CNS has also been observed in other models of S. aureus infection in the periphery. It will be interesting to determine whether other virulence factors such as V8 protease and staphylococcal enterotoxin B contribute to CNS disease as they do in the periphery, or if this is where the similarities between these divergent compartments end.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS40730) and the Hitchcock Foundation (both to T.K.) and NIH grant NS-27321 (to W.F.H.).

We thank John Hutchins for image analysis and excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelnour A, Arvidson S, Bremell T, Ryden C, Tarkowski A. The accessory gene regulator (agr) controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in a murine arthritis model. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3879–3885. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3879-3885.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Booth M C, Cheung A L, Hatter K L, Jett B D, Callegan M C, Gilmore M S. Staphylococcal accessory regulator (sar) in conjunction with agr contributes to Staphylococcus aureus virulence in endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1550–1556. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1550-1556.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callegan M C, Engel L S, Hill J M, O'Callaghan R J. Corneal virulence of Staphylococcus aureus: roles of alpha-toxin and protein A in pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2478–2482. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2478-2482.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung A L, Koomey J M, Butler C A, Projan S J, Fischetti V A. Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus (sar) distinct from agr. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6462–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung A L, Eberhardt K J, Chung E, Yeaman M R, Sullam P M, Ramos M, Bayer A S. Diminished virulence of a sar−/agr− mutant of Staphylococcus aureus in the rabbit model of endocarditis. J Clin Investig. 1994;94:1815–1822. doi: 10.1172/JCI117530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung A L, Bayer M G, Heinrichs J H. sar genetic determinants necessary for transcription of RNAII and RNAIII in the agr locus of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3963–3971. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3963-3971.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flaris N, Hickey W F. Development and characterization of an experimental model of brain abscess in the rat. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:1299–1307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank A L, Marcinak J F, Mangat P D, Schreckenberger P C. Community-acquired and clindamycin-susceptible methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:993–1000. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199911000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillaspy A F, Hickmon S G, Skinner R A, Thomas J R, Nelson C L, Smeltzer M S. Role of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in pathogenesis of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3373–3380. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3373-3380.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giraudo A T, Cheung A L, Nagel R. The sae locus of Staphylococcus aureus controls exoprotein synthesis at the transcriptional level. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:53–58. doi: 10.1007/s002030050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouaux E. Alpha-hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus: an archetype of beta-barrel, channel-forming toxins. J Struct Biol. 1998;121:110–122. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gresham H D, Lowrance J H, Caver T E, Wilson B S, Cheung A L, Lindberg F P. Survival of Staphylococcus aureus inside neutrophils contributes to infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:3713–3722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinrichs J H, Bayer M G, Cheung A L. Characterization of the sar locus and its interaction with agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:418–423. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.418-423.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickey W F, Gonatas N K, Kimura H, Wilson D B. Identification and quantitation of T-lymphocyte subsets found in the spinal cord of Lewis rats with acute EAE. J Immunol. 1983;131:2805–2809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji Y, Marra A, Rosenberg M, Woodnutt G. Regulated antisense RNA eliminates alpha-toxin virulence in Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6585–6590. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6585-6590.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahl B C, Goulian M, van Wamel W, Herrmann M, Simon S M, Kaplan G, Peters G, Cheung A L. Staphylococcus aureus RN6390 replicates and induces apoptosis in a pulmonary epithelial cell line. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5385–5392. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5385-5392.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kernodle D S, Voladri R K, Menzies B E, Hager C C, Edwards K M. Expression of an antisense hla fragment in Staphylococcus aureus reduces alpha-toxin production in vitro and attenuates lethal activity in a murine model. Infect Immun. 1997;65:179–184. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.179-184.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kielian T, Hickey W F. Proinflammatory cytokine, chemokine, and cellular adhesion molecule expression during the acute phase of experimental brain abscess development. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:647–658. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64575-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kielian T, Barry B, Hickey W F. CXC chemokine receptor-2 ligands are important for neutrophil-mediated host defense in experimental brain abscesses, J. Immunol. 2001;166:4634–4643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornblum J, Kreiswirth B, Projan S J, Ross H, Novick R P. Molecular biology of the staphylococci. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers; 1990. agr: a polycistronic locus regulating exoprotein synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. In R. P. Novick (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowy F D. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowy F D. Is Staphylococcus aureus an intracellular pathogen? Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:341–343. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathisen G E, Johnson J P. Brain abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:763–781. doi: 10.1086/515541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morfeldt E, Janzon L, Arvidson S, Lofdahl S. Cloning of a chromosomal locus (exp) which regulates the expression of several exoprotein genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;211:435–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00425697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson I-M, Bremell T, Ryden C, Cheung A L, Tarkowski A. Role of the staphylococcal accessory gene regulator (sar) in septic arthritis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4438–4443. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4438-4443.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Callaghan R J, Callegan M C, Moreau J M, Green L C, Foster T J, Hartford O M, Engel L S, Hill J M. Specific roles of alpha-toxin and beta-toxin during Staphylococcus aureus corneal infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1571–1578. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1571-1578.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng H L, Novick R P, Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Schlievert P. Cloning, characterization, and sequencing of an accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4365–4372. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4365-4372.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rescei P, Kreiswirth B, O'Reilly M, Schlievert P, Gruss A, Novick R P. Regulation of exoprotein gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus by agr. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;202:58–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00330517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soriano A, Martinez J A, Mensa J, Marco F, Almela M, Moreno-Martinez A, Sanchez F, Munoz I, Jimenez de Anta M T, Soriano E. Pathogenic significance of methicillin resistance for patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:368–373. doi: 10.1086/313650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomita T, Kamio Y. Molecular biology of the pore-forming cytolysins from Staphylococcus aureus, alpha- and gamma-hemolysins and leukocidin. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:565–572. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Townsend G C, Scheld W M. Infections of the central nervous system. Adv Intern Med. 1998;43:403–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]