Abstract

Background

Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors (ATRT) are highly aggressive pediatric brain tumors. The available treatments rely on toxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which themselves can cause poor outcomes in young patients. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARP), multifunctional enzymes which play an important role in DNA damage repair and genome stability have emerged as a new target in cancer therapy. An FDA-approved drug screen revealed that Rucaparib, a PARP inhibitor, is important for ATRT cell growth. This study aims to investigate the effect of Rucaparib treatment in ATRT.

Methods

This study utilized cell viability, colony formation, flow cytometry, western blot, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemistry assays to investigate Rucaparib’s effectiveness in BT16 and MAF737 ATRT cell lines. In vivo, intracranial orthotopic xenograft model of ATRT was used. BT16 cell line was transduced with a luciferase-expressing vector and injected into the cerebellum of athymic nude mice. Animals were treated with Rucaparib by oral gavaging and irradiated with 2 Gy of radiation for 3 consecutive days. Tumor growth was monitored using In Vivo Imaging System.

Results

Rucaparib treatment decreased ATRT cell growth, inhibited clonogenic potential of ATRT cells, induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and led to DNA damage accumulation as shown by increased expression of γH2AX. In vivo, Rucaparib treatment decreased tumor growth, sensitized ATRT cells to radiation and significantly increased mice survival.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that Rucaparib has potential to be a new therapeutic strategy for ATRT as seen by its ability to decrease ATRT tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: ATRT, PARP inhibitor, Rucaparib

Key Points.

Rucaparib treatment decreased ATRT cell growth, and induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in ATRT in vitro and in vivo.

Rucaparib pretreatment sensitizes ATRT cells to radiation.

Rucaparib treatment significantly increased mice survival.

Rucaparib has potential to be a new therapeutic strategy for ATRT.

Importance of the Study.

The present study shows that PARP inhibitor Rucaparib is essential for ATRT cell growth. Moreover, in vivo Rucaparib decreases growth of intracranial orthotopic ATRT tumors, leads to necrosis/apoptosis in ATRT tumors and prolongs survival time in Rucaparib-treated mice. More importantly, Rucaparib sensitizes ATRT cells to ionizing radiation by increasing DNA damage. Therefore, Rucaparib treatment is a highly promising new therapeutic strategy that should be explored to treat the children with such devastating tumors.

Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) is an aggressive pediatric brain tumor with a 5-year overall survival rate of 30–40%.1–4 It is responsible for between 1 and 2% of pediatric brain tumors and 10% of infant central nervous system tumors.5 Current therapies include high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue, followed by radiotherapy in infants and young children (< 5 years old) or the use of intensive multimodal chemotherapy with radiation in patients who are older (6–18 years old).4 Therapy-related toxicity remains a major concern in these young age groups.6,7 Safer and more effective therapeutic approaches are critically needed for children with ATRTs. Because genetic instability is a recurrent issue for cancer cells, especially in DNA repair pathways,8 DNA agents are an attractive antitumor strategy. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARP) are multifunctional enzymes which play important roles in DNA damage repair and genome stability and have emerged as a new target in cancer therapy. Rucaparib, a PARP inhibitor, has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by the European Medicines Agency. In 2016, Rucaparib was approved for advanced ovarian cancer with both germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations. In 2017 and 2018, Rucaparib were approved for the maintenance treatment of recurrent, epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer irrespective of the BRCA status.9 Previous studies have demonstrated Rucaparib has antitumor activity in neuroblastoma,10 childhood neuroblastoma11 and childhood medulloblastoma,8 but its efficacy in ATRT has not been thoroughly investigated. In this study we demonstrate that ATRT treatment with PARP inhibitor Rucaparib leads to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, suppresses intracranial tumor growth, and sensitizes ATRT cells to radiation in vivo and in vitro by enhancing DNA damage.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Reagents

ATRT cell lines were cultured as described in our previous studies.12 The BT16 ATRT cell line (MYC subtype) was a gift from Dr. Peter Houghton (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Center for Childhood Cancer, and Blood Diseases, OH, USA). The MAF737 (TYR subtype), cell line was established from a surgical sample of a 12-month-old male, obtained from the Children’s Hospital Colorado (Colorado, USA) and collected in accordance with local and Federal human research protection guidelines and IRB regulations (approval no. COMIRB 95-500). Consent was provided by the parents. All cell lines were authenticated with STR fingerprinting using Globalfiler System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and processed on ABI 3500Xl Genetic Analyzer. All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using Venor GeM Mycoplasma Detection Kit (# MP0025-1kt, Sigma- Aldrich). Cell lines were typed by RNA seq to assign ATRT subtypes. BT16 is a MYC subtype and MAF737 is a TYR subtype as previously described.13,14 Rucaparib (#HY-10617A) was purchased from Med Chem Express. DMSO was used as a control (DMSO, #D2650; Sigma-Aldrich). A drug screen was performed using a panel of 147 FDA-approved chemotherapeutics targeting various genes and pathways (provided by National Cancer Institute).

Transfection of ATRT Cells

Luciferase-expressing BT16 ATRT cell line was obtained by transfecting with the pLV[Exp]-Bsd-EF S>Luc2(ns):T2A:TurboGFP vector (VectorBuilder, Inc.), as previously described by us.12

Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS)

Cells were plated at 3000 cells/well in a 96-well dish and exposed to DMSO or Rucaparib for 72 h at 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2 μM. Cell viability was assessed on Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek) with Cell Proliferation Assay (#G3580, Promega) as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Colony Formation Assay

The assays were performed as previously described in triplicate.12 The BT16 and MAF737 ATRT cell lines were seeded in six-well plates, in triplicate, at a density of 500 cells/well, treated with Rucaparib (100, 150, 200, 250, 500, 800 and 1000 nM) and cultured for 10 days. The cells were stained with 0.25% crystal violet in methanol for 15 min at room temperature. Crystal violet-positive colonies (>50 cells per colony) were counted using a Precise Electronic Counter (Heathrow Scientific, LLC) and a light inverted microscope at ×2 magnification (Olympus S751; Olympus Corporation). IC50 was calculated by comparing the colony numbers in treated and untreated cells.

Irradiation In vivo

Irradiation In vivo was performed as previously described.12 10 Female athymic nude mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and placed in a prone position in the X-RAD SmART irradiator. (Precision X-Ray Irradiation, Madison CT). A fractionated dose of 2 Gy per day was given on 3 consecutive days using the SmART irradiator to deliver a 225 kVp photon beam using 0.3 mm Cu filtration and a 1 cm diameter circular.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot assay on BT16 and MAF737 cells was performed as described in our previous studies.12 The following primary antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. were used: TP53 (# 9282), P21 (#2947), PUMA (#12450), γH2AX (#9282), Tubulin (#3873). Secondary antibodies: α-mouse-HRP (#7076) and α-rabbit-HRP (#7074) (both diluted to 1:5000) (both from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.).

In vivo Xenograft Models

In vivo xenograft models were performed as previously described.12 A total of 20 female athymic nude (Foxn1 nu) mice (6-weeks-old; weight, 18–20 g) from Harlan Laboratories were used. Luciferase-expressing Bt16 ATRT cells (300 000 cells in 3 µl serum-free medium) were injected into the cerebellum. Carprofen (5 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously after the surgery, once daily, for 3 days. After the tumor was established in the cerebellum, the animals were randomized into 4 groups, 5 mice per group: Control (DMSO in Corn oil #C8267, Sigma), Rucaparib (50 mg/kg; 5 days per week for 2 weeks by oral gavage), Radiation group (2 Gy, 3 consecutive days), Radiation following Rucaparib pretreatment group (50 mg/kg; 5 days per week for 5 days by oral gavage, then 2 Gy radiation 3 consecutive days). For bioluminescence analysis, d-luciferin potassium salt solution (10 µl/g from a stock solution of 15 mg/ml; Gold Biotechnology, inc.) was injected, via intraperitoneal injection and imaged using the Xenogen IVIS 200 in vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Inc.). Tumor bioluminescence was analyzed using the Living Image v2.60.1 software (Caliper Life Sciences; PerkinElmer, Inc.). The body weight of all mice was measured weekly. Mice were monitored daily and euthanized with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation when they reached the endpoint of the experiment (>15% loss in body weight, irreversible neurological effects, or inability to eat or drink). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Colorado Anschutz Campus Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval number 00052).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue from the experimental animals was fixed in 10% formalin and submitted to the University of Colorado Denver Tissue Histology Shared Resource for sectioning and staining with Ki67 (1:500; #RM-9106; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), P53 (1:50; #2527; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and Caspase3 (1:1000; #9661; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) as we previously described.12 The images were captured using a BZ-X710 all-in-one fluorescence microscope (Keyence Corporation) and quantified with BZ-X viewer v.01.03.01.01.01 (Keyence Corporation).

Irradiation In vitro

Irradiation in vitro was done as we described previously.12 The BT16 cell line was radiated with 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 Gy.

Combination of Rucaparib and Ionizing Radiation

For the combination of Rucaparib treatment and ionizing radiation, the BT16 cell line was seeded at different densities (500, 1000, 2000, 4000, 6000 and 8000 cells/per well) in a six-well plate in triplicate for 24 h before the addition 105 nm Rucaparib (IC30 counted from colony formation assay) or DMSO. The cells were treated with Rucaparib for 3 days, then drug-containing medium was aspirated and normal culture medium (RPMI, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep) was added. The cells were then immediately irradiated with 2, 4, 6, 8 or 10 Gy.

10 days later the cells were stained with 0.25% crystal violet and counted as described above.12

The survival curves were generated after normalizing to Rucaparib treatment. Non-linear regressions were calculated. The radiation dose intersecting the non-linear regression for a 10% (SF0.1) and 50% (SF0.5) surviving fraction was calculated for drug dose. The sensitizer enhancement ratio (SER) was then calculated as follows: SER = SFx DMSO/SFx X nM Rucaparib. The SER allows for direct comparison of the effect of the putative sensitizing agent relative to control treated cells.

Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Assays

BT16 cells were seeded into six-well plates (100 000 cells/well) and 24 h later were treated with 0.5, 1 and 10 μM of Rucaparib. For cell cycle assay the cells were harvested 72 h later and fixed with chilled 70% ethanol for 24 h. Fixed cells were then washed and stained with propidium iodide-containing cell cycle reagent (#4500-0220, Millipore). For apoptosis assay the cells were stained using Guava Nexin reagent (#4500-0455, Millipore). Both analyses were performed on the Guava EasyCyte Plus flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo v10.8 Software.

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic and non-apoptotic populations for active Caspase3 measured by cleaved Caspase3 as we previously described.12 BT16 cells were treated with 1 µM of Rucaparib for 72 h to induce apoptosis. Cells were subsequently stained with the FITC rabbit anti-active Caspase3 antibody (#5460901). Flow cytometric analysis was performed on the Amnis FlowSight flow cytometer (Millipore, Burlington, MA).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence assay was performed as previously described.12 The BT16 ATRT cell line (3000 cells) were seeded in poly-d‑lysine‑coated chamber slides. The next day, the cells were treated with 1 μM of Rucaparib, or DMSO. The cells were irradiated with 6 Gy radiation 72 h later. The following antibodies were used: γH2AX (1:300; #9718; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; #560445; BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences). DAPI (#36935; Sigma‑Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was used for nuclear stain.12 The images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (BZ‑X700; Keyence Corporation), at x40 magnification.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Either one- or two-way ANOVA, or one- or two-tailed Student’s t-test (unpaired) was used for comparisons between groups. Kaplan–Meier survival curve comparisons were performed using log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. P < .05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The experiments were repeated independently three times.

Results

Rucaparib Inhibits ATRT Cell Growth In vitro

To find drugs which are important for ATRT cell growth, an FDA-approved 147 drug screening panel was performed. Screening revealed that Rucaparib is essential for ATRT cell growth (Figure 1A). Rucaparib is a PARP inhibitor, approved for various cancers but of unknown value as an ATRT treatment. To identify the IC50 for ATRT cells, we treated BT16 (MYC subtype) and MAF737 (TYR Subtype) ATRT cells with various Rucaparib concentrations. Cell proliferation and IC50 measurements were performed 72 h later using MTS assay. In both BT16 and MAF737 cell lines, Rucaparib treatment significantly decreased cell growth compared to control after 72 h in a dose‑dependent manner, with IC50 916 and 973 nM respectively (Figure 1B and C). To evaluate a longer-term impact, we performed colony formation assays on ATRT cells treated with varying concentrations of Rucaparib for 10 days. Rucaparib treatment significantly decreased the ability of ATRT cells to form colonies and the IC50 calculated from colony formation assay was 176 and 262 nM for BT16 and MAF737, respectively (Figure 1D and E; P < .0005 for BT16 cells and P < .05 for MAF737 cells). Notably, inhibition was much more pronounced in colony formation than in cell proliferation despite the lower dose. Our findings demonstrate that Rucaparib significantly inhibits ATRT cell growth in vitro.

Figure 1.

Rucaparib treatment is important for cell growth. (A) FDA-approved 147 drug screening panel revealed that Rucaparib treatment is important for ATRT cell growth. (B, C) Rucaparib treatment inhibits BT16 and MAF 737 ATRT cell growth. Cells were treated for 3 days, and cell proliferation was measured by MTS assay. IC50 for BT16 and MAF737 cells was 916 and 973 nM respectively. (D, E) Rucaparib inhibits clonogenic potential of BT16 and MAF737 ATRT cells treated for 10 days. Quantification of colony formation with representative wells in DMSO and Rucaparib-treated BT16 and MAF737 cells on the right (*P < .05; *P < .0005). Error bars represent SEM.

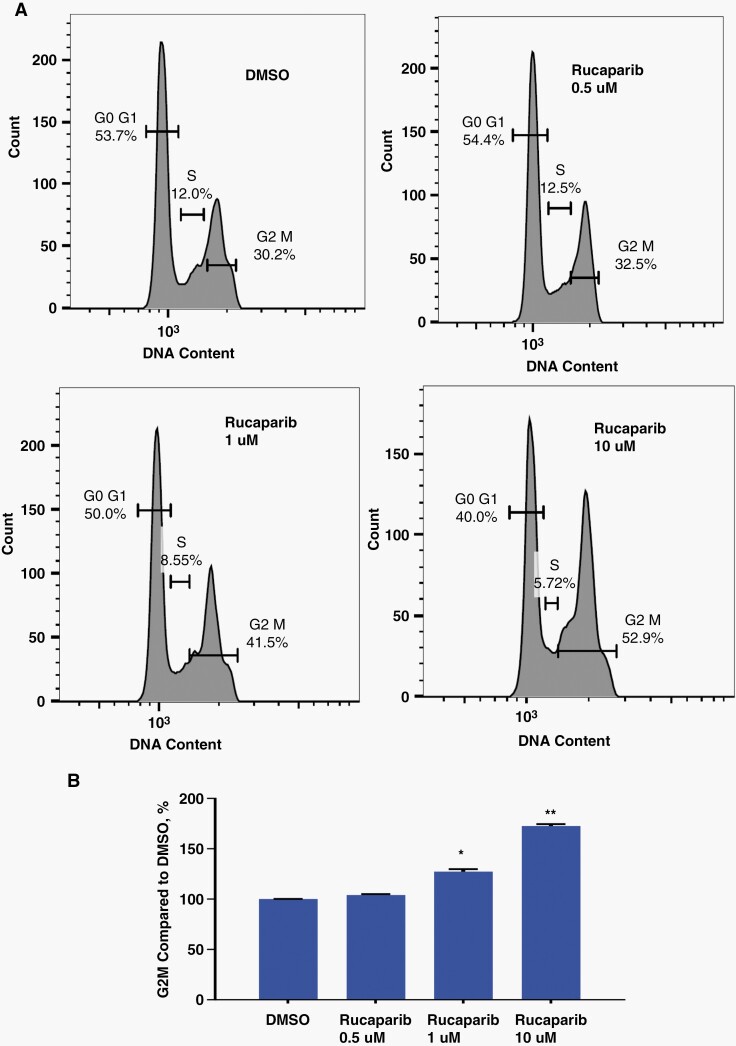

Rucaparib Inhibits ATRT Cell Growth by Perturbing the Cell Cycle

To determine whether the decreased cell growth seen with Rucaparib treatment was due to cell cycle effects, we examined its impact on the cell cycle distribution of BT16 ATRT cells. BT16 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Rucaparib (0.5, 1 and 10 μM) for 72 h. Cell cycle assay was performed with Guava flow instrument and analyzed by FLOW JO software. We found that after 72 h treatment with 1 and 10 μM of Rucaparib, the percentage of cells accumulated in G2/M phase was increased by 28% (P < .05) and 72% (P < .01) respectively compared with DMSO-control, leading to G2/M phase arrest in BT16 ATRT cells (Figure 2A, B and Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Rucaparib treatment leads to G2M phase arrest in BT16 ATRT cells. (A) Cell cycle flow plots with different Rucaparib concentration. (B) Quantification of cell cycle fractions. As compared to control untreated cells, exposure to 1 and 10 μM Rucaparib increased cell accumulation in G2/M phase by 28% and 72% respectively (*P < .05, **P < .01). Moreover, in the cells expose to 1 and 10 μM of Rucaparib S phase was 10% (P = .05) and 42% (P < .05) shorter respectively than in control DMSO-treated group, showing less DNA synthesis in Rucaparib-treated BT16 ATRT cells (Figure 2A, B and Supplementary Figure S1).

Moreover, in the cells exposed to 1 and 10 μM of Rucaparib, S phase was 10% (P = .05) and 42% (P < .05) shorter respectively than in control DMSO-treated group, showing less DNA synthesis in Rucaparib-treated BT16 ATRT cells (Figure 2A, B and Supplementary Figure S1).

Rucaparib Treatment Induces Apoptosis in ATRT Cells

We next examined whether apoptosis was a contributor to ATRT cell growth suppression and inhibition of clonogenicity by Rucaparib. BT16 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0.5, 1 and 10 μM) of Rucaparib for 72 h. Cells were collected and stained with Annexin-V. We measured Annexin-V expression on the surface of Rucaparib-treated ATRT cells by Guava flow cytometry instrument. Representative plots are shown for BT16 cells (Figure 3A). We found that number of apoptotic cells increased with increasing dose concentration, as shown, and quantified in Figure 3A and B. Compared to DMSO-treated cells, exposure to 0.5, 1 and 10 μM Rucaparib increased apoptosis by 51, 120 and 225%, respectively (**P < .01). These data demonstrate that Rucaparib treatment strongly induces apoptosis in ATRT.

Figure 3.

Rucaparib treatment induces apoptosis in BT16 ATRT cells. (A) Representative flow plots of Annexin-V expression. (B) Quantification of apoptosis in the DMSO-control and Rucaparib-treated cells. Rucaparib treatment leads to apoptosis starting at 0.5 μM (**P < .01). (C) Caspase3 assay with ImageSight imaging flow cytometry instrument. (D) Quantification of Caspase3 assay. Percentage of active Caspase3 was significant in 1 μM Rucaparib-treated cells (***P < .0005).

We then examined apoptosis associated Caspase3, and its activation in BT16 cells with the FlowSight imaging flow cytometry instrument. The BT16 cells were treated with 1 μM of Rucaparib for 72 h. We found that Caspase3 activation was significantly higher (P < .05) in the Rucaparib-treated cells compared with DMSO-control, which suggests activation of apoptosis pathways with Rucaparib treatment (Figure 3C and D).

Rucaparib Treatment Increases Expression of Apoptotic Tumor Suppressors and Leads to DNA Damage Accumulation

To determine whether ATRT inhibition alters apoptotic proteins, we performed western blot analysis. BT16 and MAF737 cells were treated with various Rucaparib concentrations (0.5, 1, 2 and 10 μM) for 72 h. Rucaparib treatment increased expression of apoptotic tumor suppressors P21 and P53 (Figure 4A, B and Supplementary Figures S2, S3). It also increased expression level of pro-apoptotic protein Puma, confirming apoptosis in treated cells (Figure 3A, B and Supplementary Figures S2, S3). Furthermore, γH2AX expression, a marker of DNA damage, was increased with Rucaparib treatment in both cell lines checked (Figure 3A, B and Supplementary Figures S2, S3).

Figure 4.

Rucaparib treatment alters apoptotic proteins and leads to DNA damage accumulation in ATRT cells. Western blot analysis was performed in the BT16 and MAF 737 cell lines following 72 h Rucaparib treatment with increasing concentration. (A, B) Western blot of Rucaparib-treated ATRT cells, showing that Rucaparib increased expression the level P21, P53 and pro-apoptotic protein Puma in the BT16 and MAF737 ATRT cells. Moreover, Rucaparib treatment led to DNA damage accumulation as seen by increased expression of γH2AX in both cell lines checked (A and B). Western blot quantification in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3.

Rucaparib Treatment Decreases Tumor Growth and Prolongs Mice Survival in Intracranial Orthotopic Xenograft Model of ATRT

We next investigated Rucaparib’s effectiveness in a mouse intracranial xenograft model. The BT16 cell line was transduced with a luciferase-expressing vector and injected into the cerebellum of immunocompromised nude mice. The mice were randomized and treated orally with Vehicle (10% DMSO in corn oil) or Rucaparib 50 mg/kg: 5 days per week for 2 weeks. Tumor formation was identified and analyzed by measuring bioluminescence signal. Treatment with Rucaparib resulted in decreased bioluminescent signal, suggesting attenuation of tumor growth (Figure 5A and B). Moreover, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed a significant improvement in overall survival time in mice treated with Rucaparib compared with those treated with vehicle (21 days vs 14 days, P < .05) (Figure 5C). Histological evaluation confirmed diffusely infiltrating ATRT tumors (Figure 5D), with decreased proliferative index in Ki67 staining in Rucaparib-treated animals (P < .05; Figure 5D and E). Furthermore, analysis of tumor tissues revealed an increased number of P53 and Caspase3-positive cells in the Rucaparib-treated group, further demonstrating induction of apoptosis/necrosis in vivo (P < .05; Figure 5D and E).

Figure 5.

Rucaparib slowed tumor growth and prolongs survival in vivo. (A) BT16/LUC cells were injected in normal mice cerebellum (300 000 cells/3 µl). After tumor was detected by IVIS, Rucaparib treatment started (50 mg/kg by oral gavaging, 2 weeks). 10% DMSO in corn oil was used for Vehicle control. IVIS images of mice on different days of treatments. Treatment started on day 0 and the results were subsequently quantified (B). Rucaparib slowed tumor growth. The error bars show the standard error of the mean. (C) Survival analysis of mice from all groups. Rucaparib prolongs survival in vivo significantly (*P < .05). (D) H&E, Ki67, P53 and Caspase3 Immunohistochemical (IHC) stains of cerebellar tumors from BT16 injected mice are shown (×40 magnification). H&E stain confirms ATRT tumors in vivo xenograft model. (E) Quantification of D. Plots show values from quantification of 5 representative images. Rucaparib treatment decreased proliferation marker Ki67 significantly (*P < .05), increased P53 and Caspase3 accumulation (*P < .05), inducing apoptosis (necrosis) in mouse tumors.

Rucaparib Enhances Radiation Sensitivity of the ATRT Cells In vitro and In vivo

Radiation is one of the main treatment methods in most ATRT clinical protocols. To investigate whether Rucaparib treatment alters the ATRT cells’ sensitivity to radiation, the BT16 cells were treated with 105 nM of Rucaparib (IC30 calculated from colony formation assay) for 24 h before irradiation with 2, 4 and 6 Gy and the effects were evaluated using a colony formation assay (Figure 6A). The sensitizer enhancement ratio (SER) was calculated at the 10% (SF0.1) and 50% (SF0.5) surviving fraction in Rucaparib and DMSO-treated cells. For the BT16 cell line pretreated with Rucaparib, the SERs were 1.48 for SF0.1 and SF0.5 (Figure 5B). The SER demonstrates the effect of the sensitizing agent relative to the control in the presence of radiation. A SER greater than one indicates a synergistic effect of the sensitization agent with radiation. Thus, the radiation survival curves obtained using the colony formation assay showed that Rucaparib pretreatment sensitized human ATRT cells to ionizing radiation. To investigate whether Rucaparib and radiation treatment in combination increased DNA damage, the BT16 cell line was cultured and treated with DMSO or 1 μM of Rucaparib and concurrently treated with 6 Gy radiation. After 24 h, the cells were evaluated for γH2AX expression using immunofluorescence, as a surrogate marker of DNA damage. Compared with that in the DMSO-control, Rucaparib alone significantly induced phosphorylation of γH2AX in the ATRT cell line (P < .001; Figure 6C, D). Radiation treatment also resulted in the accumulation of γH2AX foci (P < .001; Figure 6C, D), which was significantly enhanced by Rucaparib in the ATRT cell line (P < .0001; Figure 6C, D).

Figure 6.

Rucaparib sensitizes the BT16 ATRT cells radiation in vitro and in vivo. (A) Representative images of colony formation wells. The BT16 cell line was treated with different doses of radiation following 6 h pretreatment with 105 nM Rucaparib (IC30), then 10 days later a colony formation assay was performed. (B) The surviving fraction was calculated 10 days later according to the number of colonies. Sensitivity enhancement (SER) ratio was calculated at 10% and 50% of the surviving fraction. Rucaparib increased radiosensitization of BT16 ATRT cells with SER = 1.48. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of γH2AX accumulation in the BT16 ATRT cells, following treatment with Rucaparib (1 µM; 72 h), then irradiated with 6 Gy radiation. The cells were stained with γH2AX and DAPI 24 h after radiation. (D) Quantification of immunofluorescence. **P < .001, ***P < .0001 vs DMSO. (E) BT16/LUC cells were injected in normal mice cerebellum (300 000 cells/3 µl). After the tumor was detected by IVIS, treatment started. Mice received next treatments: Rad group: 2 Gy of radiation, 3 consecutive days. Rad+Ruca group: Rucaparib 50mg/kg by oral gavaging, 5 days, then 2 Gy of radiation, 3 consecutive days. IVIS images of mice on different days of treatments. Treatment started on day 0 and the results were subsequently quantified (F). The error bars show the standard error of the mean. (G) Survival analysis of mice. Rucaparib pretreatment sensitize ATRT cells to radiation in vivo and increased mice survival significantly (*P < .05 Ruca+Rad vs Rad).

To test our hypothesis that Rucaparib pretreatment will sensitize ATRT cells in vivo, we used our mouse orthotopic xenograft model. As described above, 300 000 BT16 cells were transduced with a luciferase-expressing vector and stereotactically injected into the cerebellum of immunocompromised nude mice. 5 mice were pretreated with Rucaparib for 5 days and then irradiated with 2 Gy of radiation for 3 consecutive days and 5 mice received 2 Gy of radiation only. Pretreatment with Rucaparib decreased bioluminescent signal and slowed down tumor growth (Figure 6E, F). Median survival of mice pretreated with Rucaparib and then radiated was significantly longer than in group radiated only mice (30 days vs 20 days, P < .05), Figure 6G.

Discussion

Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor is a highly aggressive, malignant brain tumor with poor outcome that occurs mainly in childhood.1–5 The poor outcome has resulted in a lack of clear treatment guidelines which includes highly toxic chemotherapy, radiation and autologous stem cell transplant.6,7 To improve outcomes and decrease morbidity, more targeted therapy is required. The multifunctional enzyme Poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) plays an important role in DNA damage repair and genome stability. Studies show that PARP is critical for single strand break (SSB) repair and base excision repair (BER) pathways15 and the recruitment of DNA repair proteins to the damage sites.16,17 Moreover, PARP regulates the expression of BRCA1 and RAD51 which are involved in homologous recombination18 and modulates double-strand break repair.19,22,23,20,21 For many years, PARP inhibitors have been investigated as an alternative cancer targeting therapy.9,24,25 In the present study, we performed a drug screen using a panel of 147 FDA-approved chemotherapeutics targeting various genes and pathways. One of the PARP inhibitors, Rucaparib, was found to be essential for ATRT cell growth. Rucaparib is an FDA-approved PARP1 inhibitor, with its ability to inhibit different PARPs (PARP1, PARP2, PARP5A, and PARP5B) and mono (ADP-ribosyl) transferases (PARP3, PARP4, PARP10, PARP15, and PARP16)26,27 for treatment of germline and/or advanced ovarian cancer with BRCA 1 and BRC2 mutation, epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer regardless of BRCA status. Besides using Rucaparib in ovarian cancer treatment with remarkable efficacy,28–31 this drug shows encouraging data in treatment of BRCA-mutant prostate32 and pancreatic cancers.33 However, clinical and research data on the effects of PARP inhibitors in the central nervous system (CNS) tumors is very limited. We show evidence that Rucaparib treatment decreases ATRT cell growth, inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Our results correlate with earlier findings.34 Using single-cell time-lapse microscopy, previous studies found that Rucaparib increased P53 pulse duration, altering the temporal expression of multiple P53 target genes. The most consistent obstacle to using PARP inhibitors in CNS brain tumors is blood brain barrier (BBB) penetration. A few studies demonstrated less effectiveness of Rucaparib in BBB penetration as compared to other PARP inhibitors.35–37 Central nervous system penetration and PARP activity inhibition in brain by Rucaparib was demonstrated on childhood medulloblastoma models.8 Recently, Nguyen et al38 showed that Rucaparib has promising pharmacokinetic activity and antitumor efficacy using intracranial triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) mouse model with a BRCA1-mutation. Moreover, Nguyen et al38 demonstrated that in patients with germline BRCA2-mutant breast cancer and CNS progressive disease clinical activity has been observed and brain tumor size decreased after 1 cycle of rucaparib treatment (600 mg PO BID). We found that Rucaparib treatment decreased tumor growth in ATRT intracranial xenograft model and significantly prolonged mice survival. P53 and Caspase3 accumulation in mice tumors treated with Rucaparib were significantly higher than in control, confirming apoptosis pathway activation and BBB penetration. The unique properties of Rucaparib cause an accumulation of PARP-DNA complex that cause further DNA damage as well as apoptosis.9 Radiation is one of the main treatment methods in most ATRT clinical protocols4 and by itself leads to DNA damage. Our data demonstrates that in vivo Rucaparib synergized ATRT cells to radiation in vitro with SER 1.48 and significantly increased survival mice treated with Rucaparib and then radiated. Our data is consistent with previous authors,10 that show Rucaparib as a radiosensitizer for medulloblastoma treatment. Our findings show a promise that Rucaparib administration may have a beneficial effect when administrated with radiation. Based on our findings, it is clear that Rucaparib treatment affects ATRT growth in vitro and in vivo. Additional in vivo studies are required to establish dosing schedules, combining Rucaparib with radiation The limitation of our work is that only one model of ATRT has been tested in vivo and further work is required to examine impact on all subtypes of ATRT in vivo. In this study, we specifically examined the combination of Rucaparib with radiation. Current Protocols, including COG 0333 and the Boston Protocol, use radiation as a key component of ATRT treatment. However, we did not examine Rucaparib in the context of cytotoxic chemotherapy, which may be useful in future protocols that omit radiation. Our perspective is that all patients with ATRT require radiation as optimal therapy for obtaining cures. We envision adding Rucaparib to radiation regimens as part of future trials. As such our data support further evaluation of the clinical potential of Rucaparib in ATRT treatment. We anticipate validating our studies with additional ATRT models in vivo and examining the addition of cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy as part of these pre-clinical in vivo studies to identify optimal regimens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contribution of University of Colorado Pathology Shared Resource, Research Histology Division, The University of Colorado Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource, The Skin Diseases Research Core and Animal Imaging Shared Resource (Colorado, USA).

Contributor Information

Irina Alimova, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Gillian Murdock, Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Angela Pierce, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Dong Wang, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Krishna Madhavan, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Breauna Brunt, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Sujatha Venkataraman, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA; The Morgan Adams Foundation Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program, Children’s Hospital, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Rajeev Vibhakar, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA; The Morgan Adams Foundation Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program, Children’s Hospital, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders, Children’s Hospital, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Department of Neurosurgery, University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Funding

This study was supported by the Morgan Adams Foundation Pediatric Research Program (to R.V.) and the University of Colorado Cancer Center National Cancer Institute grant (1R25CA240122 to G.M.). The University of Colorado Pathology Shared Resource, Research Histology Division, Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource, Animal Imaging Shared Resource were supported by the Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA046934). The Skin Diseases Research Cores Grant (P30AR057212).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

RV and IA designed the study and wrote the manuscript. IA and GM conducted experiments, performed data analysis, and prepared the figures. AP developed and performed in vivo studies. DW performed and analyzed Caspase3 assay. KM developed and performed radiation studies. BB performed in vivo intracranial injections and mice treatment. SV and RV conceived the project and edited the manuscript. IA and RV confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors were involved in the writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Rorke LB, Packer RJ, Biegel JA.. Central nervous system atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors of infancy and childhood: definition of an entity. J Neurosurg. 1996;85(1):56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buscariollo DL, Park HS, Roberts KB, Yu JB.. Survival outcomes in atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor for patients undergoing radiotherapy in a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis. Cancer. 2012;118(17):4212–4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fruhwald MC, Biegel JA, Bourdeaut F, Roberts CW, Chi SN.. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors-current concepts, advances in biology, and potential future therapies. Neuro-oncology. 2016;18(6):764–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoffman LM, Richardson EA, Ho B, et al. Advancing biology-based therapeutic approaches for atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors. Neuro-oncology. 2020;22(7):944–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chi SN, Zimmerman MA, Yao X, et al. Intensive multimodality treatment for children with newly diagnosed CNS atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):385–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lafay-Cousin L, Fay-McClymont T, Johnston D, et al. Neurocognitive evaluation of long term survivors of atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors (ATRT): The Canadian registry experience. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2015;62(7):1265–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Daniel RA, Rozanska AL, Mulligan EA, et al. Central nervous system penetration and enhancement of temozolomide activity in childhood medulloblastoma models by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor AG-014699. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(10):1588–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slade D. PARP and PARG inhibitors in cancer treatment. Genes Dev. 2020;34(5–6):360–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nile DL, Rae C, Hyndman IJ, Gaze MN, Mairs RJ.. An evaluation in vitro of PARP-1 inhibitors, rucaparib and olaparib, as radiosensitisers for the treatment of neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2016 Aug 11;16:621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daniel RA, Rozanska AL, Thomas HD, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 enhances temozolomide and topotecan activity against childhood neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(4):1241–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alimova I, Wang D, Danis E, et al. Targeting the TP53/MDM2 axis enhances radiation sensitivity in atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors. Int J Oncol. 2022 Mar;60(3):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alimova I, Pierce A, Danis E, et al. Inhibition of MYC attenuates tumor cell self-renewal and promotes senescence in SMARCB1-deficient Group 2 atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors to suppress tumor growth in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2019 Apr 15;144(8):1993–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ho B, Johann PD, Grabovska Y, et al. Molecular subgrouping of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (ATRT)—a reinvestigation and current consensus. Neuro-oncology. 2020 May 15;22(5):613–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rouleau M, Patel A, Hendzel MJ, Kaufmann SH, Poirier GG.. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(4):293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu C, Vyas A, Kassab MA, Singh AK, Yu X.. The role of poly ADP-ribosylation in the first wave of DNA damage response. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(14):8129–8141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ray Chaudhuri A, Nussenzweig A.. The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(10):610–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hegan DC, Lu Y, Stachelek GC, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase down-regulates BRCA1 and RAD51 in a pathway mediated by E2F4 and p130. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(5):2201–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ceccaldi R, Liu JC, Amunugama R, et al. Homologous-recombination-deficient tumours are dependent on Poltheta-mediated repair. Nature. 2015;518(7538):258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Audebert M, Salles B, Calsou P.. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and XRCC1/DNA ligase III in an alternative route for DNA double-strand breaks rejoining. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(53):55117–55126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mateos-Gomez PA, Gong F, Nair N, et al. Mammalian polymerase theta promotes alternative NHEJ and suppresses recombination. Nature. 2015;518(7538):254–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chan SH, Yu AM, McVey M.. Dual roles for DNA polymerase theta in alternative end-joining repair of double-strand breaks in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(7):e1001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kent T, Chandramouly G, McDevitt SM, Ozdemir AY, Pomerantz RT.. Mechanism of microhomology-mediated end-joining promoted by human DNA polymerase theta. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(3):230–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zheng F, Zhang Y, Chen S, et al. Mechanism and current progress of Poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020 Mar;123:109661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Min A, Im SA.. PARP inhibitors as therapeutics: beyond modulation of PARylation. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Feb 8;12(2):394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas HD, Calabrese CR, Batey MA, et al. Preclinical selection of a novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor for clinical trial. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(3):945–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wahlberg E, Karlberg T, Kouznetsova E, et al. Family-wide chemical profiling and structural analysis of PARP and tankyrase inhibitors. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(3):283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10106):1949–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ledermann JA, Oza AM, Lorusso D, et al. Rucaparib for patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL3): post-progression outcomes and updated safety results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):710–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kristeleit R, Shapiro GI, Burris HA, et al. A phase i–ii study of the oral parp inhibitor rucaparib in patients with germline BRCA1/2-mutated ovarian carcinoma or other solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(15):4095–4106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, et al. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abida W, Patnaik A, Campbell D, et al. Rucaparib in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer harboring a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene alteration. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(32):3763–3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reiss KA, Mick R, O’Hara MH, et al. Phase II study of maintenance rucaparib in patients with platinum-sensitive advanced pancreatic cancer and a pathogenic germline or somatic variant in BRCA1, BRCA2, or PALB2. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(22):2497–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hanson RL, Batchelor E.. Rucaparib treatment alters p53 oscillations in single cells to enhance DNA-double-strand-break-induced cell cycle arrest. Cell Rep. 2020;33(2):108240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Durmus S, Sparidans RW, van Esch A, et al. Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) and P-glycoprotein (P-GP/ABCB1) restrict oral availability and brain accumulation of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib (AG-014699). Pharm Res. 2015;32(1):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parrish KE, Cen L, Murray J, et al. Efficacy of PARP Inhibitor rucaparib in orthotopic glioblastoma xenografts is limited by ineffective drug penetration into the central nervous system. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(12):2735–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kizilbash SH, Gupta SK, Chang K, et al. Restricted delivery of talazoparib across the blood-brain barrier limits the sensitizing effects of parp inhibition on temozolomide therapy in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(12):2735–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nguyen M, Robillard L, Harding T, et al. Abstract 3888: intracranial evaluation of the in vivo pharmacokinetics, brain distribution, and efficacy of rucaparib in BRCA-mutant, triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:3888. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.