Abstract

The humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination has shown to be temporary, although may be more prolonged in vaccinated individuals with a history of natural infection. We aimed to study the residual humoral response and the correlation between anti-Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) IgG levels and antibody neutralizing capacity in a population of health care workers (HCWs) after 9 months from COVID-19 vaccination.

In this cross-sectional study, plasma samples were screened for anti-RBD IgG using a quantitative method. The neutralizing capacity for each sample was estimated by means of a surrogate virus neutralizing test (sVNT) and results expressed as the percentage of inhibition (%IH) of the interaction between RBD and the angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Samples of 274 HCWs (227 SARS-CoV-2 naïve and 47 SARS-CoV-2 experienced) were tested. The median level of anti-RBD IgG was significantly higher in SARS-CoV-2 experienced than in naïve HCWs: 2673.2 AU/mL versus 610.9 AU/mL, respectively (p <0.001). Samples of SARS-CoV-2 experienced subjects also showed higher neutralizing capacity as compared to naïve subjects: median %IH = 81.20% versus 38.55%, respectively; p <0.001. A quantitative correlation between anti-RBD Ab and inhibition activity levels was observed (Spearman's rho = 0.89, p <0.001): the optimal cut-off correlating with high neutralization was estimated to be 1236.1 AU/mL (sensitivity 96.8%, specificity 91.9%; AUC 0.979).

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 hybrid immunity elicited by a combination of vaccination and infection confers higher anti-RBD IgG levels and higher neutralizing capacity than vaccination alone, likely providing better protection against COVID-19.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Vaccination, Healthcare workers, Immune response, Neutralizing capacity

Although the immune protection conferred by natural SARS-CoV-2 infection or by primary COVID-19 vaccination varies widely among different population categories, the burden of anti-S IgG response is high, ranging between 85 and 100% [1], and likely higher in COVID-19 experienced subjects who have been subsequently vaccinated [1,2].

A waning of immune humoral response, as defined by both anti-S IgG titers and neutralizing antibody (nAb) levels, has been reported over 6 months in both vaccinated subjects and convalescent patients [3,4]. Therefore, additional doses of vaccine were recommended to the original regimen. However, besides the waning of total antibody levels, the antibody neutralizing capacity, i.e. the ability to prevent viral entry by inhibiting the binding of the viral Spike Receptor-Binding Domain (S-RBD) and the cell receptor angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), is crucial to estimate the functionality of humoral response. Neutralizing activity can be studied by both direct tests, which represent the golden standard but require extensive protective measures due to the use of viable virions or by surrogate tests, which study the binding competition between antibodies and target receptors. Several surrogate virus neutralizing tests (sVNT) have been recently studied in COVID-19 experienced and vaccinated subjects, showing a good correlation between sVNT and conventional virus neutralization test (cVNT) and a high specificity, sensitivity and robustness [5,6]. These tests may be therefore useful in large-scale human sero-epidemiological studies for obtaining additional information regarding the quality of the humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or vaccination.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the residual humoral response against SARS-CoV-2 in previously infected and naïve health care workers (HCWs) after 9 months from primary COVID-19 vaccination, and to study the correlation between anti-RBD IgG levels and antibody neutralizing capacity.

Between October and November 2021 and before the administration of the third “booster” dose of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, HCWs at the Luigi Sacco-University Hospital in Milan, were invited to participate to a cross-sectional serological survey and 274 who accepted were enrolled. They were asked to fill in a questionnaire that, in addition to demographic and occupational data, included questions concerning whether they had ever had a positive swab for SARS-CoV-2 or had tested positive for anti-N SARS-CoV-2 antibodies at any time during the period 2020–2021.

The study population included BTN162b2 mRNA vaccine recipients who either were SARS-CoV-2 naïve or had been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Milan (Comitato Etico Università degli Studi di Milano, n. 23/21) and was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Plasma samples were stored at −20 °C until serological tests were performed. Samples were screened for antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (anti-N IgG) using the Abbott chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Abbott, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) and for IgG antibodies against the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the viral S1 spike protein (anti-RBD IgG), which levels showed a strong correlation with neutralizing activity [7], using the SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant assay (Abbott, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA), kindly provided by Abbott. The assay cut-off is ≥ 50 AU/ml, with linear quantification of detected results from 50 to 40,000 AU/ml reported by the manufacturer [8].

The neutralizing capacity for each plasma sample was investigated using the SARS-CoV-2 nAb kit (SGM Italy; REF 8003), a particle-enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay (PETIA) kindly provided by Abbott. This surrogate virus neutralization test conforms to requirements of the European Directive 98/79/EC for in vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVDDs) and is used to quantify in vitro the serum nAbs that bind specifically to RBD [interaction site of RBD and ACE2 protein]. The automated assay performed on the platform Abbott Alinity C, uses the principle of antigen–antibody reaction and competition between antigens. Briefly, latex particles coated with recombinant RBD are added to the samples: the presence of anti-RBD antibodies leads to the agglutination of the antigen-antibody complex; when latex-coated ACE2 is eventually added, its binding with anti-RBD antibodies results to be inhibited. The higher the concentration of neutralizing antibodies and the level of inhibition, the weaker the reaction between ACE2 antigen and RBD would be, and the lower the absorbance detected through the change in the opaqueness of the reaction solution on a spectrophotometer. According to the manufacturer, the results can be interpreted as follows: the reference value, intended as the cut-off value, corresponds to 25% of inhibition, a value between 25% and 56% indicates a low to moderate inhibition, whereas a value >56% indicates a high inhibition.

Comparison of categorical and continuous variables was performed using the Chi-square or Fisher's exact test and the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test, respectively. Correlation between continuous variables was performed by using Spearman's rho test. We then calculated the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, the associated Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Youden Index (Y) to determine the optimal antibody level cut-off. All statistics were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 and p-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

After 9 months from the primary COVID-19 vaccination with the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine, and just before the administration of the “booster” dose, a total of 274 HCWs were tested (Table 1 ): their median age was 47 years and 209 (76.3%) were women. Forty-seven (17.2%) HCWs had a previous history of SARS-CoV-2 infection which dated back to more than 6 months in 41 subjects and within the previous 6 months in 6 subjects. All SARS-CoV-2 naïve and 39 of experienced subjects (most of whom had been infected for more than 6 months) resulted negative for anti-N IgG. Anti-RBD IgG were detected in all HCWs but two and the median IgG level was significantly higher in SARS-CoV-2 experienced than in SARS-CoV-2 naïve subjects: 2673.2 AU/mL [IQR 1105.3, 7056.2] versus 610.9 AU/mL [IQR 376.9, 1035.0], respectively (p <0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and humoral immune response of the study population.

| Overall | SARS-CoV-2 experienced | SARS-CoV-2 naïve | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 274 | N = 47 (17.2%) | N = 227 (82.8%) | |||

| Age (years) median [IQR] | 47 [37, 56] | 44 [33, 55] | 48 [38, 56] | 0.181 | |

| Sex, N (%) | Females | 209 (76.3) | 35 (74.5) | 174 (76.7) | 0.711 |

| Males | 65 (23.7) | 12 (25.5) | 53 (23.3) | 0.519 | |

| Anti-N Ab positive HCWs, N (%) | 8 (2.9) | 8 (17.0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| Anti-RBD Ab (AU/mL), median [IQR] | 735.70 [403.73, 1295.73] | 2673.20 [1105.30, 7056.20] | 610.90 [376.95, 1035.00] | <0.001 | |

| %IH, median [IQR] | 42.30 [28.90, 58.30] | 81.20 [56.95, 100.00] | 38.55 [27.30, 50.68] | <0.001 | |

| %IH, N (%) | <25 | 44 (16.1) | 1 (2.1) | 43 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| 25–56 | 154 (56.2) | 10 (21.3) | 144 (63.4) | ||

| >56 | 76 (27.7) | 36 (76.6) | 40 (17.6) |

IQR: interquartile range; Anti-N Ab: antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein; HCWs: Healthcare workers; Anti-RBD Ab: IgG antibodies against the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike protein; %IH: percentage of inhibition.

Overall, the median level of inhibition, used as an estimate of the percentage of nAbs out of the total anti-RBD antibodies, was of 42.30% [IQR 28.90, 58.30], being below the cut-off in the 16.1% of the study subjects, and between 25 and 56% (moderate inhibition) and >56% (high inhibition) in 56.2% and 27.7% of the subjects, respectively (Table 1).

The median percentage of inhibition (%IH) was significantly higher in SARS-CoV-2 experienced subjects than in naïve ones: 81.20% [56.95, 100.00] versus 38.55% [27.30, 50.70], respectively; p <0.001. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 experienced subjects whose infection dated back to more than 6 months showed lower levels of inhibition as compared to those who had the infection during the 6 months before the test: 79.80% [53.30, 100.00] versus 100% [83.95, 100.00].

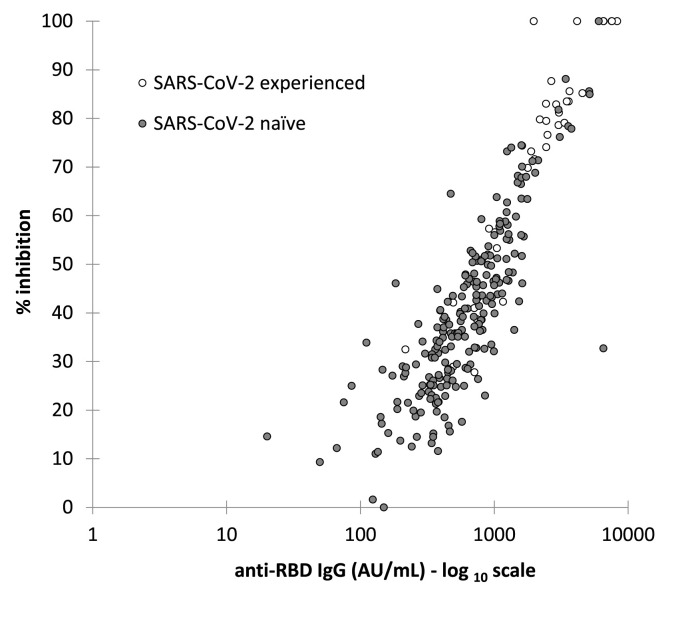

A quantitative correlation between anti-RBD Ab levels and inhibition activity was observed in the whole cohort (Spearman's rho = 0.89, p <0.001), as well as for the SARS-CoV-2 experienced (rho = 0.93, p <0.001) and naïve subgroups (rho = 0.85, p <0.001), as reported in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Quantitative correlation between anti-RBD IgG levels and percentage of inhibition (%IH) in experienced and naïve HCWs. Spearman's rho: SARS-CoV-2 experienced (ρ = 0.929; p <0.0001); SARS-CoV-2 naïve (ρ = 0.847; p <0.0001).

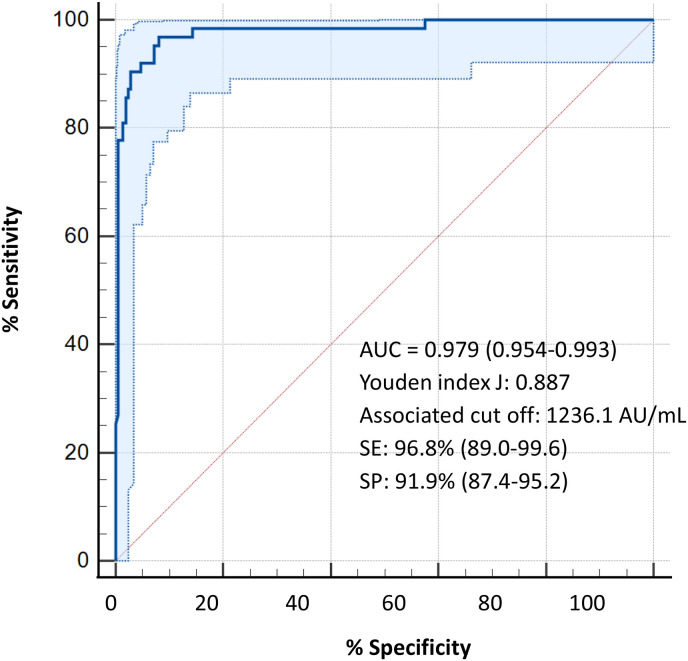

The optimal antibody level cut-off to identify a high neutralizing activity (>56%) by Youden's index calculated on the ROC curves was 1236.1 AU/mL (sensitivity 96.8% and specificity 91.9%; AUC 0.979) and did not differ between SARS-CoV-2 experienced and naïve subjects (1162.7 AU/mL and 1236.1 AU/mL, respectively; sensitivity and specificity of 100% in experienced HCWs and of 93.1% and 91.4% in naïve HCWs) (Fig. 2 ). According to the anti-RBD IgG cut-off level of 1236.1 AU/mL, associated with high neutralizing activity (>56%), 72.3% of SARS-CoV-2 experienced HCWs were above this level while only 19.8% of SARS-CoV-2 naïve HCWs showed such high neutralizing activity.

Fig. 2.

ROC curve for the identification of the optimal anti-RBD IgG level cut-off to determine a percentage of inhibition >56%.

The duration of immunity and the level of protection against SARS-CoV-2 elicited either by natural infection or by vaccination are still matter of concern, although it has been suggested that natural immunity may be associated with longer and broader coverage [9,10].

Albeit there is a wide agreement on the observation that anti-S-RBD response is still detectable after 6 months from COVID-19 vaccination [11], though at a significantly decreased level, a reliable threshold of anti-RBD Abs consistent with a high neutralizing activity has not been identified.

In this study, we examined the residual anti-S antibody levels and the neutralizing activity (percentage of inhibition) in 274 HCWs after 9 months from the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. We used a novel automated sVNT to quantify the percentage of neutralizing antibodies. Our findings showed that both the anti-RBD response and the neutralizing capacity were still detectable before the booster dose of vaccine at a significantly higher level in SARS-CoV-2 experienced than naïve subjects, thus confirming previous data on the longer durability of the natural over the vaccine-induced immunity against SARS-CoV-2 [10,12]. Furthermore, a consistent threshold value of anti-S antibodies able to discriminate an inhibitory percentage >56% was identified with a good sensitivity and specificity (96.8% and 91.9%, respectively). Interestingly, the strong correlation we found between anti-RBD Ab levels and neutralization activity, which is consistent with data of previous studies [13,14], suggests that high levels of anti-RBD antibodies may represent a reliable tool to determine the level of protection provided by vaccination or natural infection over time. This observation might be worthwhile for evaluating the immunogenicity of COVID-19 convalescent plasma pools as well as in population studies for planning vaccination policies and the timing of further vaccine boosters.

Since discordant results exist on the correlation between different sVNT and cell-based neutralization assays [5,6], the main limitation of the study is the lack of a direct comparison of sVNT with a cell-based VNT. Another limitation is represented by the small number of HCWs who became infected within 6 months before the sera collection, thus lowering the power to detect a difference among SARS-CoV-2 experienced HCWs according to the time of their previous infection. Lastly, due to the cross-sectional design of the study, we could not evaluate the actual relationship between the magnitude and length of humoral response and the risk of infection, reinfection and of severity of disease.

In conclusion, anti-SARS-CoV-2 hybrid immunity elicited by a combination of vaccination and infection confers higher anti-RBD IgG levels and higher neutralizing capacity than vaccination alone, likely providing better protection against COVID-19. The spectrum of neutralizing activity addressed by sNVT that uses the traditional spike viral protein to measure immunogenicity of BNT162b2 vaccine resulted suitable to evaluate neutralizing immunity to SARS-CoV-2 variants detected in Italy up to the study period: B.1.1.7 (alfa >90%) and P.1 (gamma; <10%), gradually replaced by B.1.617.2 (delta) [15]. However, the subsequent emergence of Omicron variants carrying mutations in the spike protein and in the RBD, potentially raises the question about the current and future reliability of commercial anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG assays and sVNTs available at the time of our study. Since a correlate of protection will undoubtedly be variant-specific, continued sero-epidemiological studies might be needed to address the efficiency of current available tests over time.

Authors contribution

LP, LM and ALR designed the study; LO was responsible for the statistical analysis. LP, LM, ALR, GC, MB, SC, AL and ALR contributed to patient enrolment, and to the collection of samples. CK, LC and CO contributed to perform the tests and interpretation of data. LP, LM and ALR supervised the project. LP and LM prepared a preliminary draft of the manuscript, which was critically reviewed by ALR and SA. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank the healthcare workers of Luigi Sacco Hospital, who kindly and eagerly participated in the study.

Footnotes

All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria.

References

- 1.Anderson M., Stec M., Rewane A., Landay A., Cloherty G., Moy J. SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in infection-naive or previously infected individuals after 1 and 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2021.19741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milazzo L., Pezzati L., Oreni L., Kullmann C., Lai A., Gabrieli A., et al. Impact of prior infection status on antibody response to the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers at a COVID-19 referral hospital in Milan, Italy. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17:4747–4754. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.2002639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin E.G., Lustig Y., Cohen C., Fluss R., Indenbaum V., Amit S., et al. Waning immune humoral response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine over 6 months. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:e84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA2114583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg Y., Mandel M., Bar-On Y.M., Bodenheimer O., Freedman L., Haas E.J., et al. Waning immunity after the BNT162b2 vaccine in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:e85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA2114228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer B., Reimerink J., Torriani G., Brouwer F., Godeke G.J., Yerly S., et al. Validation and clinical evaluation of a SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralisation test (sVNT) Emerg Microb Infect. 2020;9:2394–2403. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1835448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan C.W., Chia W.N., Qin X., Liu P., Chen M.I.C., Tiu C., et al. A SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test based on antibody-mediated blockage of ACE2-spike protein-protein interaction. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:1073–1078. doi: 10.1038/S41587-020-0631-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujigaki H., Inaba M., Osawa M., Moriyama S., Takahashi Y., Suzuki T., et al. Comparative analysis of antigen-specific anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody isotypes in COVID-19 patients. J Immunol. 2021;206:2393–2401. doi: 10.4049/JIMMUNOL.2001369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan A., Pepper G., Wener M.H., Fink S.L., Morishima C., Chaudhary A., et al. Performance characteristics of the Abbott architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG assay and seroprevalence in boise, Idaho. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00941-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chivu-Economescu M., Bleotu C., Grancea C., Chiriac D., Botezatu A., Iancu I.V., et al. Kinetics and persistence of cellular and humoral immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthcare workers with or without prior COVID-19. J Cell Mol Med. 2022;26:1293–1305. doi: 10.1111/JCMM.17186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattiuzzi C., Lippi G. Primary COVID-19 vaccine cycle and booster doses efficacy: analysis of Italian nationwide vaccination campaign. Eur J Publ Health. 2022;32:328–330. doi: 10.1093/EURPUB/CKAB220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrotri M., Navaratnam A.M.D., Nguyen V., Byrne T., Geismar C., Fragaszy E., et al. Spike-antibody waning after second dose of BNT162b2 or ChAdOx1. Lancet (London, England) 2021;398:385–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01642-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitcombe A.L., McGregor R., Craigie A., James A., Charlewood R., Lorenz N., et al. Comprehensive analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics in New Zealand. Clin Transl Immunol. 2021;10 doi: 10.1002/CTI2.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cristiano A., Pieri M., Sarubbi S., Pelagalli M., Calugi G., Tomassetti F., et al. Evaluation of serological anti-SARS-CoV-2 chemiluminescent immunoassays correlated to live virus neutralization test, for the detection of anti-RBD antibodies as a relevant alternative in COVID-19 large-scale neutralizing activity monitoring. Clin Immunol. 2022;234 doi: 10.1016/J.CLIM.2021.108918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franzese M., Coppola L., Silva R., Santini S.A., Cinquanta L., Ottomano C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses before and after a third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine in Italian healthcare workers aged ≤60 years: one year of surveillance. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2022.947187/FULL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monitoraggio delle varianti del virus SARS-CoV-2 di interesse in sanità pubblica in Italia n.d. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/sars-cov-2-monitoraggio-varianti-rapporti-periodici accessed.