Abstract

Objectives

To gain insight into the experiences of women with completing and discussing patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) and patient-reported experience measures (PREM), and tailoring their care based on their outcomes.

Design

A mixed-methods prospective cohort study.

Setting

Seven obstetric care networks in the Netherlands that implemented a set of patient-centred outcome measures for pregnancy and childbirth (PCB set), published by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement.

Participants

All women, receiving the PROM and PREM questionnaires as part of their routine perinatal care, received an invitation for a survey (n=460) and an interview (n=16). The results of the survey were analysed using descriptive statistics; thematic inductive content analysis was applied on the data from open text answers and the interviews.

Results

More than half of the survey participants (n=255) felt the need to discuss the outcomes of PROM and PREM with their care professionals. The time spent on completing questionnaires and the comprehensiveness of the questions was scored ‘good’ by most of the survey participants. From the interviews, four main themes were identified: content of the PROM and PREM questionnaires, application of these outcomes in perinatal care, discussing PREM and data capture tool. Important facilitators included awareness of health status, receiving personalised care based on their outcomes and the relevance of discussing PREM 6 months post partum. Barriers were found in insufficient information about the goal of PROM and PREM for individual care, technical problems in data capture tools and discrepancy between the questionnaire topics and the care pathway.

Conclusions

This study showed that women found the PCB set an acceptable and useful instrument for symptom detection and personalised care up until 6 months post partum. This patient evaluation of the PCB set has several implications for practice regarding the questionnaire content, role of care professionals and congruity with care pathways.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study had a prospective design and was incorporated in an implementation project as part of routine perinatal care.

As a result of the embedding in an implementation project, we were able to combine the results of a large sample size of survey participants with semistructured interviews to explore survey answers in-depth, which increased the generalisability of our results.

These are the first experiences from patient perspective regarding completing and discussing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) during routine perinatal care.

A limitation of this study was the unequal representation of time points for PROM and PREM collection in our interview sample, due to the nature of the implementation project.

The evaluation survey had a response rate of 35%, which creates a risk for non-response bias that should be considered when interpreting our results.

Introduction

Healthcare systems are increasingly focusing on creating value for patients.1 Therefore, patient-reported outcome measures and experience measures (PROM and PREM) are progressively used to guide individual patient care, in quality improvement and for research purposes. PROM and PREM are defined as information that is provided by patients concerning the impact of their condition, disease or treatment on their health and functioning.2 3 In routine care, patients complete PROM and PREM via standardised questionnaires—both generic and disease specific—between visits to care professionals. Care professionals receive notifications about alarm symptoms, such as pain or functional complaints and can review longitudinal PROM and PREM reports over time. This way, symptoms and impairments are more likely to be detected, creating an opportunity to personalise care based on individual needs.4 In chronic care settings, this approach has been shown to improve shared decision making, patient–clinician relationship and health outcomes.5 6

In perinatal care, important outcomes expressing quality of life and social participation can be detained from PROM and PREM, such as maternal depression, incontinence and birth experience. PROM and PREM may differ greatly and may be independent of provider-reported outcomes, describing far-reaching effects on women’s lives.7 8 Additionally, PROM and PREM may highlight important outcomes from the patient perspective that remained hidden when collecting provider-reported outcomes only. Therefore, implementation of standardised PROM and PREM, including the adaptation of individual care pathways based on individual outcomes, is essential to further personalise and improve quality of perinatal care from the patient perspective. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) provided a set of patient-centred outcome measures for pregnancy and childbirth (PCB set) for perinatal care containing both provider-reported and patient-reported outcomes.9 Prior research in the Netherlands found this set to be acceptable and feasible for implementation by all important stakeholders including women.10 11 However, little is known regarding women’s experiences with completing the PROM and PREM and receiving care based on their individual outcomes as part of routine perinatal care.

In the Netherlands, a nationwide implementation project was initiated to facilitate shared decision making by implementing the PROM and PREM of the PCB Set in regular perinatal care. To achieve successful implementation, identifying unanticipated influences, facilitators and barriers among the users during the early implementation process of PROM and PREM is crucial.12 Our preimplementation research identified women as important users next to perinatal care professionals.10 11 Insights into first women’s experiences with receiving personalised care based on their individual PROM and PREM during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period will enhance and improve further implementation of PROM and PREM as part of routine perinatal care. Therefore, alongside the nationwide implementation project, we conducted a mixed-methods study to gain insight into the experiences of women with completing and discussing PROM and PREM, and tailoring their care based on their outcomes in a routine perinatal care setting.

Methods

Design

Mixed-method prospective cohort study to gain insight into women’s experiences with using the PROM and PREM of the ICHOM PCB set for perinatal care in clinical practice among women receiving perinatal care.

Setting

This study was conducted in seven obstetric care networks (OCNs) participating in a nationwide implementation project of the ICHOM PCB set in the Netherlands. Alongside the implementation project in clinic, this study was performed to evaluate women’s experiences with this innovation in routine care. The implementation project aimed integration of the PCB Set into routine perinatal care, that is, that women were invited to complete PROMs and PREMs and discuss them with their care professional as part of routine perinatal care at five time points during their pregnancy or postpartum period. At these time points, different care professionals may have been responsible for the participants’ health (see figure 1). Women received an information leaflet regarding the purpose of the PROM and PREM before filling out their first PROM and PREM questionnaire and could complete the questionnaires digitally at home. Care professionals were informed about the content of the PCB Set (figure 2) and how to interpret the results. Training on how to discuss the outcomes was available if needed. Care professionals discussed the results of the PROM and PREM during the next regular visit directly after each time point, also at 6 months post partum. Implementation plans differed among the OCNs to enhance local implementation; OCNs collected PROM and PREM during at least one time point, this was not necessarily time point 1 (see table 1).

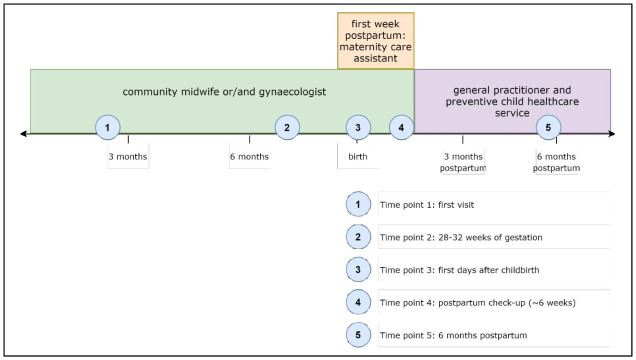

Figure 1.

Time points for data collection (PROM and PREM) and involvement of different care professionals, according to current practice in the Netherlands. The blue dots indicate the five time points for data collection during pregnancy and postpartum. Above the timeline, the involved care professionals are shown. In this project, the outcomes of the PROMs and PREMs were discussed with an obstetric care professional during all time points.9 PREM, patient-reported experience measure; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

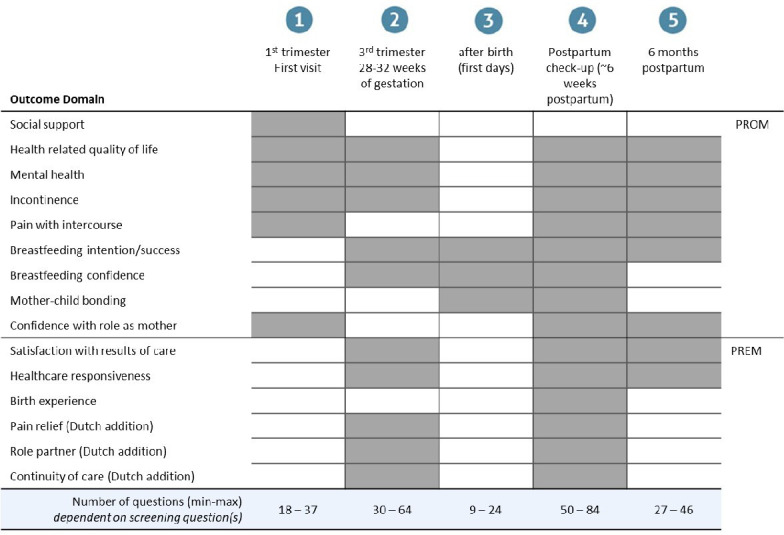

Figure 2.

Pregnancy and childbirth set as applied in the Netherlands: domains and moments to measure (adapted from Depla et al 22). The blue dots indicate the five time points for data collection during pregnancy and post partum (see also figure 1). The outcome domains are divided into patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs). Below, the number of questions of the total questionnaire (PROM and PREM) per time point is shown.

Table 1.

Implementation of time points per obstetric care network

| OCN 1 | OCN 2 | OCN 3 | OCN 4 | OCN 5 | OCN 6 | OCN 7 | |

| Time point 1: first visit | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Time point 2: 28–32 weeks of gestation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Time point 3: first days after childbirth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Time point 4: postpartum check-up | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Time point 5: 6 months post partum |

✓ | ✓ |

OCN, obstetric care network.

Patient and public involvement statement

Simultaneously with the implementation of the PCB set, this study was conducted to gain insight into women’s experiences with completing and discussing PROM and PREM. Both the clinical implementation project and this study were a continuation of previous projects that actively involved women as important stakeholders, resulting in changes into the Dutch PCB set, as well as providing insight into facilitators and barriers to be addressed during the implementation of the PCB set in routine care. In this study, we sent out a survey and conducted interviews with women. The study was designed in close collaboration with care professionals, while taking into account previous findings from surveys, interviews and focus group interviews with women.10 11 13 Also, the PROM and PREM questionnaires used in clinic were tested for comprehensiveness among four women with low health literacy skills supported by Pharos, a national centre of expertise in decreasing health inequities.14 Small language adaptations were made based on this test.

Participants

As our study was conducted within a large implementation project of the PCB set, all women who received PROM and PREM questionnaires as part of their routine perinatal care in one of the participating OCNs were eligible for this study. Women were invited to participate in this study via a digital link immediately after filling out a PROM/PREM questionnaire at home. They were asked to complete a short evaluation survey and optionally participate in a telephone interview regarding their experiences with completing and discussing the PROM and PREM.

Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows:

Women completed at least one questionnaire of the PCB set.

Women were 16 years or older during the first data collection time point.

Women gave their informed consent to use their answers for research.

Data collection

Data collection was performed from March 2020 to September 2021. The researchers composed of a short evaluation survey (online supplemental table 1). This anonymous survey was offered to participants via a digital link directly after completing their PROM and PREM. One OCN collected this evaluation survey on paper. No case mix questions were asked to minimise response burden for women who had already completed the PROM and PREM questionnaire. Answers to this survey were not visible to care professionals. At the end of this evaluation survey, participants were asked to provide their telephone number for an in-depth evaluation interview by phone. First, all participants who provided their telephone number were approached for a semistructured interview by one of the researchers (see for topic list table 2). Further on, purposive sampling was performed, for example, selecting women that had filled out PROM and PREM at time points 3–5, or women who gave specific answers in the evaluation survey. Additionally, care professionals were asked to actively recruit women with decreased health literacy skills for an interview by the researchers. Data collection was ended as soon as thematic saturation was accomplished (see the Data analysis section). All interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim.

Table 2.

Topic list used for the interviews

| Topics | Sub topics |

| Course pregnancy/childbirth | General health/experiences pregnancy |

| Time spent on completing PROM and PREM—experiences | Experiences completing PROM and PREM Experience on time spend Motivation for completion of PROM and PREM Reasons for (not) completing PROM and PREM in the future Time points 1 and 2: thoughts regarding completing PROM and PREM multiple times during pregnancy and after childbirth Time points 3–5: experiences with completing PROM and PREM after childbirth up until 6 months post partum |

| Comprehensiveness PROM and PREM | Understanding PROM and PREM: language used, reason why PROM and PREM were asked, information provision Social desirability PREM regarding experiences with care providers: completing and discussing |

| Discussing PROM and PREM with care professionals | Experiences regarding discussing PROM and PREM Adverse outcomes of PROM and PREM Taboo topics Bond with care professional Unexpected outcomes Resistance regarding discussing PROM and PREM Advantages and gains of discussing PROM and PREM |

| Improvements and suggestions | Results of evaluation survey Previously completed PROM and PREM Important topics |

| Preferred care provider | Time point Outcomes that are discussed |

| Shared decision making | Care pathway—participant’s influence Discussing wishes and fears regarding pregnancy and childbirth Patient—care professional relationship |

PREM, patient-reported experience measures; PROM, patient-reported outcome measures.

bmjopen-2022-064452supp001.pdf (230.7KB, pdf)

Data analysis

The quantitative data from the evaluation survey were analysed using descriptive statistics with SPSS V.25 (IBM). Free-text answers were analysed with thematic analysis supported by Microsoft Excel (V.16). The transcriptions from the interviews were checked for accuracy with the original audiotapes by LTL. The software program Atlas.ti V.9 was used to support thematic inductive content analysis.15 LTL and SSK independently coded the transcripts to create a set of preliminary codes and compared the codes to reach consensus. To detect emerging themes, we merged matching codes and explored links between codes. An overview was constructed of themes and subthemes for women’s experiences with completing and discussing PROM and PREM. This overview was compared with the free-text answer analysis of the open-ended questions from the survey and combined into an integrated overview. The integrated overview was discussed with ALD, ML-dR and MNB and subthemes were identified as facilitators and barriers. Reporting followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.16

Results

Survey

A total of 460 participants (35%) filled out the patient evaluation survey from a total of 1318 women who completed at least one PROM and PREM questionnaire. Descriptive statistics of the survey are shown in online supplemental table 2 and online supplemental figure 1a–d. Regarding the time spent on completing the questionnaires, 87% of participants indicated this as ‘good’. The comprehensiveness of the questions was indicated as ‘good’ by most participants (78%). The need to discuss the outcomes of the questionnaires with the care professional differed: of the participants 39% answered ‘not really’, and 35% ‘a little’, and 20% ‘yes’. Of the participants that wanted to discuss the outcomes, the majority preferred their obstetric care professional for this. The answers from the open-ended questions are to be discussed below.

bmjopen-2022-064452supp002.pdf (150.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064452supp003.pdf (242.7KB, pdf)

Interviews

Twenty-six participants provided their telephone number for the interview, none of these participants had completed PROM and PREM during time point 3 (maternity week). Sixteen interviews were conducted. We interviewed two participants that completed PROM and PREM during time points 1 and 4, nine during time point 2, and three during time point 5. The average age of participants was 34 years (29–39 years) and the majority were higher educated (14 of 16), that is, completed an education at a university or university of applied sciences. Four participants received perinatal care for the first time; they were pregnant for the first time or had given birth to their first child. Six participants had received perinatal care by a community midwife, five by a gynaecologist in the hospital, and five by both community midwives and gynaecologists.

Themes

The facilitators and barriers identified from the open-ended questions and interviews were allocated to four overarching themes (see table 3): (1) Content of the PROM and PREM, (2) Application of the outcomes of PROM and PREM in perinatal care, (3) Discussing PREM and (4) Data capture tool. These themes including facilitators and barriers are described below in detail, with illustrative quotes.

Table 3.

Overarching themes and identified facilitators and barriers

| Themes | Facilitators | Barriers |

| 1. Content of PROM and PREM questionnaires | Clear language PROM and PREM covering all important topics Good length of questionnaires Awareness of taboo topics |

Language of some questions too difficult Some PROM questions not specific in time or location Discrepancy questions with care path and situation Absence of answer option ‘I don't know (yet)’ or ‘not applicable’ No opportunity to explain answers or pointing out important outcomes Too little attention to physical problems (time point 2) (Timing of) PROM breast feeding |

| 2. Application of the outcomes in individual care | Better preparation for next visit/appointment Discussing topics that were not discussed before Care is personalised based on individual outcomes Discussing outcomes at time point 5 |

Insufficient information on the aim personalised care based on PROM and PREM Uncertainty when outcomes are discussed Feeling of impersonalised care Unsure of impact on individual quality of care Discontinuity of care professional |

| 3. Discussing PREMs | PREM being included in the questionnaires Insight into individual PREM improves individual quality of care Discussing PREM at time point 5 important for reflection on pregnancy and childbirth Analysis of aggregate PREM for care improvement Completing PREM safer option in case of dissatisfaction |

Receiving multiple questionnaires regarding experiences Negative PREM preferably face to face Dependency of care professional |

| 4. Data capture tool | Completing questionnaires digitally Availability on mobile phones or tablets |

Technical problems and bugs Privacy issues |

PREM, patient-reported experience measures; PROM, patient-reported outcome measures.

Content of PROM and PREM questionnaires

Most participants found the language of the PROM and PREM clear and understood the questions. Participants felt that the PROM and PREM covered most important topics and were of a good length. Most participants emphasised the importance of PROM and PREM addressing taboo topics, such as incontinence, depression and pain with intercourse. In the interviews, participants shared that completing PROM and PREM on these topics created awareness about their current health status and potential problems during pregnancy, childbirth and first months post partum (see quote 1).

Quote 1 Awareness of taboo topics:

[Complete PROM/PREM to prepare for their next visit] “I assume [advantages] for both parties: for yourself because you think about everything, also things you wouldn’t consider at first. And I expect it [capturing PROM and PREM] would be helpful for a care professional as well, because he can ask further than just the topics a patient brings up at that moment.” (T4)

However, the language of some questions was too difficult, especially for lower educated women, and several PROMs were not specific in timing or location of physical complaints. This led to different interpretations of the questions. Regarding the content of the PREM, participants experienced discrepancy between the timing of the questions and the care received. For example, at time point 2, options for pain management during childbirth had often not been discussed yet, thus participants answered negative to the PREM addressing this. Another issue mentioned by the interview participants in relation to PREM, was that they often received care from multiple care professionals. They stated that they had to average their experiences when completing the PREM. Several participants reported that they missed the answer option ‘I don’t know (yet)’ or ‘not applicable’ in some questions, and the possibility to explain their answers. Also, participants missed the possibility in the questionnaires to point out important outcomes. This topic was expanded during the interviews; participants wanted to be able to indicate outcomes important to discuss during the following visit (see quote 2).

Quote 2 No opportunity to explain answers or pointing out important topics

[Opportunity for explanation during completion of PROM and PREM] “You should have a choice: whether you want to discuss it [your answers] or not, whether you want to be referred or not. […] You could put it [an open text field] at the end of the questionnaire: ‘If you want consultation on this, if you have a top 3 or top 5 or something of the things that were just asked, what are the topics you would like to discuss with your midwife?’” (T2)

Although most important topics were covered in the PROM and PREM, some participants stated that there was too little attention for prevalent physical problems. They missed questions concerning pelvic pain and haemorrhoids, especially at time point 2. Lastly, the timing of one specific topic was debated by several participants: the PROM breast feeding. At time point 2, this topic was experienced as too early since most women did not know whether they intended to breastfeed and could not properly answer the full questionnaire about self-efficacy. At time point 4, participants indicated it felt too late to discuss problems with breast feeding.

Application of the outcomes of PROM and PREM in perinatal care

Most participants indicated that filling out PROM and PREM helped them in preparing their next visit to their obstetric care professional. They stated that thinking about the topics addressed by the questionnaires made them know better what to expect from and to discuss in the following visit. Interview participants also pointed out that the use of PROM and PREM led to discussion of topics that previously were no part of the conversation with their care professional. Some participants indicated that they were unaware of some topics being pregnancy related, such as psychological problems. Furthermore, some participants from the interviews said that they felt their care was personalised based on their individual outcomes, for example, extra attention, information, or a referral for specialised care (see quote 3 and quote 4).

Quote 3 Care is personalised based on individual outcomes

“Then she [the care professional that discussed her outcomes with her] said she could refer me to a clinic for pelvic problems if I wanted to. […] I thought that was very good. They directly did a follow-up and offered me sort of an option like ‘you could this’.” (T5)

Quote 4 Care is personalised based on individual outcomes

[her PROM answers indicated depressive symptoms] “Well… personally I think I, and they too [care professionals], gave some extra attention to my mental health.” (T2)

At time point 5, one participant from the interviews felt relieved that her care professional paid attention to her incontinence and psychological problems. She felt that otherwise she would not have had any care professional to discuss these issues with.

Despite the availability of an information leaflet and their care professionals’ explanation, many participants had misunderstood the aim of the project. They thought it was a research project and that their answers would be used for research purposes only. This indicates that the information about the purpose of PROM and PREM for individual care was insufficient, which posed a major barrier to complete questionnaires multiple times (see quote 5).

Quote 5 Insufficient information on the aim personalised care based on PROM and PREM

“It was not clear to me why it [PROM and PREM] was asked. And I also can’t remember that it [PROM and PREM questionnaires] included an introduction text or something like that… maybe that was included you know… but for me it was not clear what they wanted to do with that information [her answers]” (T2)

Furthermore, some participants stated it was uncertain when the outcomes of their questionnaire would be discussed with them; not all participants had their outcomes discussed during the first visit after completing the PROM and PREM. One participant said that her outcomes had never been discussed with her. Several participants mentioned that completing PROM and PREM gave them the feeling of ‘impersonalised care’, as if care professionals tried to avoid the conversation about these topics. Other interview participants felt unsure about how the outcomes of the PROM and PREM would impact the quality of care of their individual care pathway. For example, when filling out negative experiences regarding one specific care professional, they preferred to receive care from another care professional because of their negative experience. Some participants, from both the survey and the interviews, felt that discontinuity in care professionals posed a barrier to discuss the outcomes. They did not feel at ease discussing outcomes with a care professional they had never met before (see quote 6). Interview participants also did not always know which care professional was responsible for their outcomes.

Quote 6 Discontinuity of care professional

“Nothing really popped up [from her answers to the questionnaires], but if that would have been the case than I think it is harder to discuss some topics with a person [care professional] that I have never met. Especially because some of these topics are sensitive and vulnerable.” (T1)

Discussing PREM

Participants stated that the PREM was an important facilitator for them to complete the PROM and PREM. They stressed that they found it very important that care professionals in general have insight into patients’ experiences with their provided care. Additionally, participants from the interviews thought that the insight into individual PREM may lead to improved quality of individual care. Especially participants that had completed PREM at time point 5 stated that the PREM was important to complete and to discuss, because it helped them to process the pregnancy and postpartum period (see quote 7).

Quote 7 Discussing PREM at time point 5 important for reflection on pregnancy and childbirth

[After completing the T5 questionnaire] “The fact that she [care professional] called back, that she called back actually concerned, and just … just was talking with me and explained things. That has really, also in my head, enormously helped to sort things out. […] Yes, I really look back on that [childbirth and postpartum period] better now.” (T5)

Additionally, analysis of aggregate PREM results may indicate improvement topics, according to the interview participants. At the same time, a barrier was identified in overlap; some participants received PREM and other evaluation questionnaires from their community midwives post partum, and it was unclear for them whether these outcomes were also sent to their midwives. Ambiguous opinions were found regarding discussing PREM individually. Some participants, who were satisfied with the care they received, indicated they would have preferred addressing negative experiences directly with their care professional, instead of via PREM (see quote 8). In contrast to participants who had negative experiences: they explained it felt easier to indicate this via PREM instead of discussing it face to face with their care professional.

Quote 8 Negative PREM preferably face to face

[addressing care experiences with care professional] “I believe it is fairer when they [care professionals] hear it from me personally, but I can imagine that some people don’t feel comfortable with that and prefer to leave their feedback anonymously and that eventually it will reach the care professional anyway.” (T2)

Additionally, some participants stated to feel dependent of their care professional during their care pathway, which posed a barrier to report negative experiences in the PREM.

Data capture tool

Participants indicated that they preferred to complete PROM and PREM digitally. Completing the PROM and PREM on mobile phones or tablets was preferred by most women. However, participants pointed out technical issues as a major barrier; PROM and PREM questions and answers that were not entirely visible on a mobile phone led to incomplete or incorrect outcomes according to some women (see quote 9).

Quote 9 Technical problems and bugs

[Completing PROM and PREM] “On my smartphone I can’t see all the questions. On the iPad, some answer options disappear, so I must check three times whether my answers are completed correctly. For example, satisfaction is measured on a scale from 1 to 4. But when I go to the next page and back, it appears to be a scale from 1 to 10.” (T2)

Also, some participants received PROM and PREM belonging to a different time point or received the same PROM and PREM multiple times. Furthermore, several interviewed participants stated that it was unclear which organisation sent the invitation to complete the questionnaires and which care professionals had access to their answers. This made them have doubts regarding privacy (see quote 10).

Quote 10 Privacy issues

[Completing questions regarding incontinence, mental health, physical complaints]: “And yes, those are questions of a kind that you would only complete honestly if you are completely sure that you can trust that they will end up at the right person.” (T2)

Discussion

This mixed-methods study provides insight into the first experiences of women with completing and discussing PROM and PREM at different time points during and after pregnancy as part of routine perinatal care. The evaluation survey results showed that the time spent on completing the PROM and PREM was acceptable, and their content was comprehensive. Most survey participants felt the need to discuss the outcomes. In the interviews, participants were mainly positive about discussing their individual PROM and PREM outcomes with their perinatal care professionals. Women’s barriers and facilitators to complete and discuss PROM and PREM individually were identified in four overarching themes.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the prospective design, incorporated in an implementation project as part of regular care. Its results supported further implementation of the outcome set, as they were directly translated into adaptations in the clinical project, such as IT improvements and an option to further explain an answer. Accordingly, by providing PROMs and PREMs throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period, women can become aware of what high-quality care encompasses, and of complications or symptoms that can occur. This awareness can empower women and support them to adjust their care pathway to their individual preferences and values. Another strength was the large sample size of survey participants combined with semistructured interviews to explore survey answers in-depth, which increased the generalisability of our results. Also, the participation threshold was lowered by conducting the survey anonymously and the interviews by telephone, limiting the risk of selection bias. However, the survey response rate of 35% does create a risk for non-response bias. Despite our efforts to minimise the risk of selection bias with purposive sampling, mostly higher educated women were included, and only Dutch speaking women could participate to the surveys. This was inevitable to some extent, as the sample was taken from an already selected population: women completing the PROM and PREM were Dutch speaking only and had a relatively good health literacy, as no support was provided with completing them. This limitation should be taken into account when interpreting our findings and stresses the importance of future efforts to engage all women when implementing PROM and PREM to prevent further health inequities. Nevertheless, this exploration of patient experiences with individual PROM and PREM was the first among women receiving perinatal care. A second limitation, resulting from the outline of the implementation project, was the unequal representation of time points for PROM and PREM collection in our interviews. Despite our strategy to ask care professionals to recruit participants for the interviews directly, that is, without filling out the survey, we could not interview women who had completed PROM and PREM at time point 3 (maternity week).

Compared with literature

In line with findings in other disciplines, discussing PROM and PREM with care professionals as part of routine perinatal care was found to improve patient satisfaction and willingness to complete the questionnaires.6 17–19 Participants felt better prepared for their next visit and discussed topics that were not discussed before, which reconfirms results from large studies in chronic care settings.19–21 At the same time, a significant part of our survey respondents did not feel the need to discuss their outcomes. Moreover, for some women completing the questionnaires even felt as impersonalised care. As the survey was offered directly after completing the PROM and PREM, survey participants had not yet discussed their outcomes with their care professional. These findings indicate that discussing outcomes are an essential part of using PROM and PREM in clinical practice.6 Another explanation could be inadequate information provision, as several women stated that the purpose of the PROM and PREM was unclear to them. As women’s perception of this purpose largely depends on their care professional, care professionals may improve this by actively using PROM and PREM as a part of routine care. For example, by encouraging women to consider which outcomes they want to discuss in the next visit.

Using individual outcomes to tailor care was an important facilitator to complete PROM and PREM over the course of pregnancy and postpartum. Nevertheless, two important barriers to use PROM and PREM individually were raised by our participants as well. First, discrepancy between the timelines of provided care and the PROM and PREM was pointed out. For example, a PREM questioning information provision on pain relief was sent to women, before care professionals addressed this topic according to standard care. Synchronising the time points of the PCB set with routine perinatal care pathways may solve this barrier. Based on compliance to the PROM and PREM and results of the PROM and PREM, concrete recommendations to adapt the PCB set’s content and timeline have been suggested in a recent publication, and are in accordance with women’s experiences found in this study.22 Second, discontinuity in care professional was posed as a barrier, as discussing PROM and PREM with different care professionals lead to discomfort among participants. Discussing outcomes in the multidisciplinary setting of perinatal care may be easier if a principal care professional is allocated to every pregnant woman. A relationship of trust between care professional and patients may be a crucial facilitator for completing and discussing PROM and PREM, especially when discussing taboo topics such as incontinence.23 This may provide opportunity to improve perinatal care outcomes, as several taboo topics have been shown highly prevalent and only 15% of the affected women bring them up during a postpartum check-up.22 24 Additionally, although hard to accomplish by perinatal care professionals, our participants stated that evaluating their outcomes at 6 months post partum with a perinatal care professional was of added value to the regular postpartum check-up. This reconfirms previously reported patient views regarding time point 5 of the PCB set.10 11 Compared with the check-up at 6 weeks post partum, at 6 months post partum, most women have further recovered in multiple domains and resumed their work and social life. Hence, at this moment, the sustainability and severity of physical or mental problems can be determined and referred for, improving long-term outcomes of perinatal care.

Confirming preimplementation studies, our participants emphasised that PREM were an important facilitator to complete the questionnaires.10 11 However, evidence on individual PREM use as part of clinical practice is scarce. This study revealed different opinions among women: some preferred to address negative experiences face to face, some felt PREM made it easier to raise and others felt too dependent on their care professional to discuss a negative experience at all. Future research should evaluate the possible effects of offering each woman a choice whether her individual answers are visible to care professionals and discussed as part of her care.

As shown before from a professional perspective, a good functioning data capture tool for assessment and real-life visualisation of patient-reported measures is essential for successful implementation.6 25 26 In our patient evaluation, technological issues of the data capture tools were also a major barrier for completing the questionnaires. Although challenging in terms of interorganisational collaboration and IT infrastructure, this project was one of the first to attempt system-wide implementation of PROM and PREM as a standard part of individual perinatal care to guide individual care and personalised care pathways. In the transformation towards healthcare systems that provide patient-centred care over the full cycle of care, it is essential to use data capture tools that facilitate information exchange between all healthcare tiers involved with a disease or condition.

Future research and implications

To achieve personalised care based on PROM and PREM, patient engagement is essential but requires efforts at several points. For successful implementation, women will benefit from a system-wide data capture tool, a principal care professional to discuss their outcomes with and a timeline of PROM and PREM collection that fits clinical care: matching their appointments and content of care pathways. Also, an open-text field to explain answers and point out outcomes they want to discuss could empower women to take an active role in their care. Lastly, when completing PROM and PREM, women should be clearly informed about (1) the purpose of using their answers for personalised care and (2) the topics addressed by the questionnaires at each time point and their relation to PCB. Since care professionals are crucial in providing this information and in discussing the outcomes, future research may focus on the experiences of care professionals with PROM and PREM use in perinatal care. To engage care professionals, it would be useful to evaluate training strategies, but also their perceived benefits when working with PROM and PREM. These could include direct improvement of individual care for their patients, as well as insight into the results of their efforts in terms of patient outcomes.13 These practice implications resulting from women’s reflections on individual level PROM and PREM use can advance structural integration of women’s perspective in clinical care. Although clinical integration can enable group level use, further research is still needed to explore how PROM and PREM can contribute to embed patients’ perspective in research and management decisions as well.

Conclusions

This study reported the first patient experiences with completing and discussing PROM and PREM as part of perinatal care. The ICHOM PCB set was found to be an acceptable and useful instrument for symptom detection and personalised perinatal care up until 6 months postpartum. Women’s reflections on these PROMs and PREMs allow several practice implications to improve the questionnaire content, the role of care professionals and congruity with routine care pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the women participating in this study. We thank the participating care professionals for approaching women and for discussing the PROMs and PREMs.

Footnotes

Collaborators: BUZZ project team: Jolanda H. Vermolen (Maternity care organization De Waarden, Schoonhoven, the Netherlands), Simone A. Vankan-Buitelaar (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Wilhemina Children’s Hospital, University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands), Monique Klerkx (Integrated obstetric care organization Annature Geboortezorg, Breda, the Netherlands), Pieter-Kees de Groot (Department of Obstetrics, Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem, the Netherlands), Nikkie Koper (Midwifery practice Duo, Zwanenburg, the Netherlands), Hilmar H. Bijma (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Division Obstetrics and Foetal Medicine, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), Bas van Rijn (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Division Obstetrics and Foetal Medicine, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), Elise Neppelenbroek (Midwifery practice Verloskundigen Bakerraad, Zwolle, the Netherlands), Sebastiaan W.A. Nij Bijvank (Department of Obstetrics, Isala Clinics, Zwolle, the Netherlands), Marieke Veenhof (Department of Obstetrics, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands), Margo Lutke Holzik (Department of Obstetrics, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands), Jelle Baalman (Department of Obstetrics, Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede, the Netherlands), Josien Vrielink-Braakman (Midwifery practice Verwacht!, Vriezenveen, the Netherlands).

Contributors: AF, HEE-S, JAH and MNB led the overall implementation project in practice and established its funding. Collaborators of the BUZZ team led local implementation and recruited study participants. This study was designed by LTL, ALD and ML-dR under supervision of AF, HEE-S and MNB. LTL and SSK performed the interviews for data collection and analysed the data under supervision of MNB. LTL, ALD and MNB interpreted the data. LTL and ALD wrote the first version of the manuscript and made adaptations after feedback of the other authors under supervision of MNB. MNB, AF, JAH, HEE-S, ML-dR, SSK and the BUZZ team reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. MNB is the guarantor for the final product.

Funding: This work was supported by Zorginstituut Nederland (ZIN) grant number 2018026697.

Competing interests: AF and ML-dR were chair and member respectively of the ICHOM working group that developed the PCB standard outcome set. The other authors have nothing to declare.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

the BUZZ project team:

Jolanda H Vermolen, Simone A Vankan-Buitelaar, Monique Klerkx, Pieter-Kees de Groot, Nikkie Koper, Hilmar H Bijma, Bas van Rijn, Elise Neppelenbroek, Sebastiaan W.A. Nij Bijvank, Marieke Veenhof, Margo Lutke Holzik, Jelle Baalman, and Josien Vrielink-Braakman

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants but the Medical Ethics Committee Erasmus Medical Centre (MEC-2020-0129) declared that the rules laid down in the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (also known as WMO) do not apply to this study. This study was exempt from formal medical ethical assessment. Local approval of the regional ethical boards was obtained in each participating OCN. All participants signed written informed consent. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining health care: creating value-based competition on results. Harvard Business Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gliklich RD, Leavy M. Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: A user’s guide [Internet]. 2014. [PubMed]

- 3. U.S. Department of Health Services Human F.D.A. Center for Drug Evaluation Research, U.S. Department of Health Human Services F.D.A. Center for Biologics Evaluation Research, U.S. Department of Health Human Services F.D.A . Center for devices radiological health, guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to supportlabeling claims: draft guidance. health qual life outcomes. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basch E. Patient-Reported outcomes-harnessing patients' ’oices to improve clinical care. N Engl J Med 2017;376:105–8. 10.1056/NEJMp1611252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basch E, Barbera L, Kerrigan CL, et al. Implementation of patient-reported outcomes in routine medical care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;38:122–34. 10.1200/EDBK_200383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Egdom LSE, Oemrawsingh A, Verweij LM, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in clinical breast cancer care: a systematic review. Value Health 2019;22:1197–226. 10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hollins Martin CJ, Martin CR. Development and psychometric properties of the birth satisfaction scale-revised (BSS-R). Midwifery 2014;30:610–9. 10.1016/j.midw.2013.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mason L, Glenn S, Walton I, et al. The experience of stress incontinence after childbirth. Birth 1999;26:164–71. 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1999.00164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nijagal MA, Wissig S, Stowell C, et al. Standardized outcome measures for pregnancy and childbirth, an ICHOM proposal. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:953. 10.1186/s12913-018-3732-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Depla AL, Ernst-Smelt HE, Poels M, et al. A feasibility study of implementing a patient-centered outcome set for pregnancy and childbirth. Health Sci Rep 2020;3:e168. 10.1002/hsr2.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laureij LT, Been JV, Lugtenberg M, et al. Exploring the applicability of the pregnancy and childbirth outcome set: a mixed methods study. Patient Educ Couns 2020;103:642–51. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Depla AL, Crombag NM, Franx A, et al. Implementation of a standard outcome set in perinatal care: a qualitative analysis of barriers and facilitators from all stakeholder perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:113. 10.1186/s12913-021-06121-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pharos . 2022. Available: www.pharos.nl/

- 15. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. Sage, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:1–24.:211. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 2017;318:197–8. 10.1001/jama.2017.7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lapin BR, Honomichl R, Thompson N, et al. Patient-Reported experience with patient-reported outcome measures in adult patients seen in rheumatology clinics. Qual Life Res 2021;30:1073–82. 10.1007/s11136-020-02692-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lapin B, Udeh B, Bautista JF, et al. Patient experience with patient-reported outcome measures in neurologic practice. Neurology 2018;91:e1135–51. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Horst C. Personalized health care for orofacial cleft patients. In: van N, Hazelzet J, eds. Personalized Specialty Care: Value-Based Healthcare Frontrunners from the Netherlands. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021: 41–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Depla AL, Lamain-de Ruiter M, Laureij LT, et al. Patient-Reported outcome and experience measures in perinatal care to guide clinical practice: prospective observational study. J Med Internet Res 2022;24:e37725. 10.2196/37725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oemrawsingh A, Hazelzet J, Koppert L. The state of patient-centered breast cancer care: an academic center’s experience and perspective. Personalized Specialty Care: Springer, 2021: 127–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schütze S, Hohlfeld B, Friedl TWP, et al. Fishing for (in) continence: long-term follow-up of women with OASIS-still a taboo. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2021;303:987–97. 10.1007/s00404-020-05878-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foster A, Croot L, Brazier J, et al. The facilitators and barriers to implementing patient reported outcome measures in organisations delivering health related services: a systematic review of reviews. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2018;2:46. 10.1186/s41687-018-0072-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arora J, Haj M. Implementing ICHOM’s standard sets of outcomes: cleft lip and palate at erasmus university medical centre in the netherlands. In: International Consortium for Hea lth Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM). London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-064452supp001.pdf (230.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064452supp002.pdf (150.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064452supp003.pdf (242.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.