Abstract

Background

Research focusing on reducing the risk of injuries has increased over the last two decades showing that prevention implementation in real life is challenging.

Objective

To explore the experience and opinions of professional football stakeholders regarding injuries, their prevention and the implementation of preventive measures.

Design

Qualitative study.

Setting

Technical and medical staff from Qatar’s premier football league.

Participants

22 professionals from 6 teams.

Main outcome

Semistructured interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using the thematic analysis method.

Results

All the participants acknowledged the importance of injury prevention. They mentioned teamwork, trust and communication as critical factors for a successful injury prevention implementation. Teams’ doctors see themselves mainly involved in the treatment and recovery process, and to a lesser degree, in the prevention process. Physiotherapists defined their primary responsibilities as screening for injury risk and providing individual exercises to players. The participants declared that the fitness coach is responsible for injury prevention implementation. All stakeholders reported that the fitness coach plays a vital role in communication by bridging the head coach and the medical staff. Stakeholders reported that the Qatari football league has a very particular context around the player, such as socioecological factors influencing injury prevention implementation.

Conclusions

The fitness coach plays a vital role in the injury prevention implementation system, as one of the key actors for the process, as well as the bridge between the medical team and the head coach, resulting from their better communication with the head coaches. The findings support considering and understanding the contextual factors during the development of preventive strategies in football.

Keywords: Soccer, Public health, Injury, Fitness testing

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Understanding of context is key to improve injury prevention implementation.

Listening to the stakeholders may help to explore the injury prevention context and current strategies.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The fitness coach is a critical player in injury prevention implementation in Qatari football, with a crucial role in the communication between the head coach and the medical team.

Teamwork and communication structure is influenced by context.

Cultural and environmental factors influence injury prevention implementation identifying key links in the communication and team work is strategical in the prevention process.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Medical staff would need to take the first step in building a good relationship and communication with the fitness coach in order to get them aligned with their injury prevention strategies.

Introduction

The rate of injuries in football, one of the most popular sports globally, has raised concerns during the past decades and warrants implementing injury prevention programmes.1 Those injuries impact physical and mental health,2 performance3 4 and have financial consequences.5 6 Research focused on reducing the risk of injuries has increased over the last two decades.7 8 Several RCTs testing various injury prevention programmes document that reducing injury risk is possible.9–11 For example, when implemented, the Nordic Hamstring Programme (NHP) reduced new hamstring injuries by 59% and reinjuries by 86%,9 but the implementation process in all professional sports settings can be challenging. For instance, research shows that most European teams did not adopt the NHP described in the articles.12 Similar results were found in a study by Chebbi et al. They followed a professional football team in Qatar for multiple seasons and found that player compliance was a significant element in successfully reducing injuries.13

Finch14 has suggested to understand the implementation context to translate research into injury prevention practice. In light of this, Bolling et al15 reinforced the importance of context driven and multilevel injury prevention approaches with shared responsibility and open communication among stakeholders. Consequently, Tee et al16 concluded that sports injury prevention research needs to move past the idea of finding singular solutions to injury problems. To close this gap, listening to the stakeholders, who practice in the elite athlete context, is essential to recognising the barriers and facilitating factors in injury prevention implementation.8 Qualitative methods allow an exploration of the context and perspectives on injury prevention. Recent studies have shown the value of the insider’s voice and the importance of qualitative research to gain insight into the complex context of injury prevention.15 17 Therefore, this study aimed to explore the experience and opinions of technical and medical staff (head coaches (HCs), fitness coaches (FCs), team doctors and physiotherapists) in professional football regarding injuries, their prevention and implementing preventive measures. The insights gained from this study could provide practical directions on ‘who’ and ‘how’ with regards to injury prevention implementation.

Methods

Study setting/design

This qualitative study followed an exploratory and practice-oriented approach. Semistructured individual interviews were conducted with technical and medical staff from the Qatar Stars League—QSL (Qatar’s premier professional football league). An interpretivist paradigm underpinned the study. Our goal was to understand the beliefs, motivations and reasoning of individuals in their context and focusing on decoding the meaning of the data while connecting with a practice-oriented approach.18 This study has an exploratory nature because we aim to explore the participants’ perception about the broad topic. As an interpretivist paradigm, we acknowledge the beliefs and meaning of individuals to represent their context. The practice-oriented design is justified as our research question focus on building understanding and knowledge for current practice.

Data collection

All the QSL medical staff, including the team doctors (TD) and the physiotherapists (PH), belong to the same organisation. However, the HC and the FCs are hired by their respective teams. In the QSL setting, the HCs bring their own FC, and when the HC changes the club, the FC follow. However, the medical team stays with the same club over the years, except very few cases. For each team, we contacted the interview of four key persons (HC, FC, TD and PH). The TD was responsible for inviting their respective clubs and scheduling interviews with their four representatives.

MT and EV developed the interview guide, which the coauthors reviewed and approved (online supplemental appendix 1). As the interviewees did not have the same native language, the interview guide was developed in English, representing the language that all the interviewees use in their professional communication. This should be taken into consideration while reading the quotes. All interviews were conducted face to face by MT (male) and lasted 30–46 min.

bmjsem-2022-001370supp001.pdf (57.6KB, pdf)

The research team planned to interview the technical and medical staff of the 17 QSL clubs. The interviewing order was determined by an electronic random selection. All the interviews were done team by team. When the four stakeholders of the group had been interviewed, data collection for the next couple started. After the fifth team, the same concepts began to be presented repeatedly, and no new information emerged. One more team was included, and no new insights or concepts emerged, indicating that we had reached saturation. The interviewer was in constant contact with the research team informing on the main concepts of data collection.

Data analysis

All the interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed through an inductive thematic analysis, enabling themes to emerge from the data. The data analysis was supported by the coding software ATLAS. ti (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany, V.8)

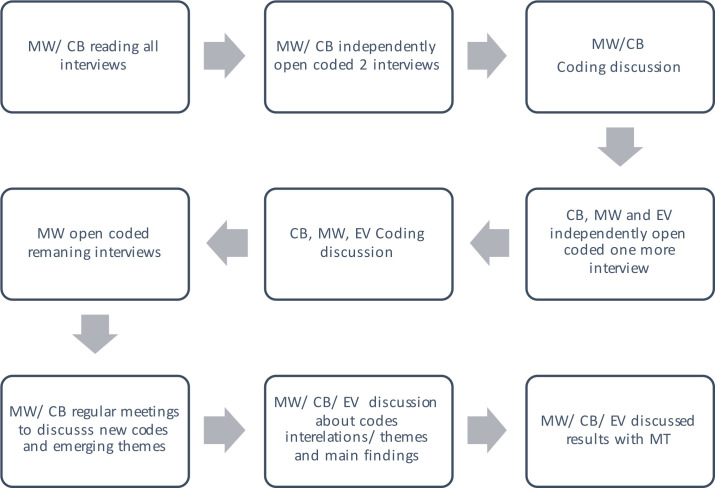

As the researchers who analysed the interviews (CB, MW) were not present during the interviews, they read all the transcripts before starting the data coding to become familiar with the data. After that, two randomly chosen interviews were independently open-coded by MW and CB, followed by a discussion about their coding. Open coding consists of labelling the data while staying close to the words of the participants. A third interview was coded independently by MW, CB and EV. The three coders discussed the principal emergent codes and discussed any potential discrepancies. MW then coded the remaining interviews based on a consensus set after the initial phase. During this period, CB and MW met regularly to discuss codes and emerging themes based on their similarities or overarching concepts. In one final meeting, CB, MW and EV further developed the analysis, looking for the relationships between codes and themes and developing a visual scheme to present the main findings. Finally, the main results of the analysis and the visual scheme were presented to MT (who conducted the interviews). During the analysis, memos were kept promoting reflection on codes, categories and relationships that emerged during the data analysis. A schematic view of this data analysis process is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data analysis structure.

Results

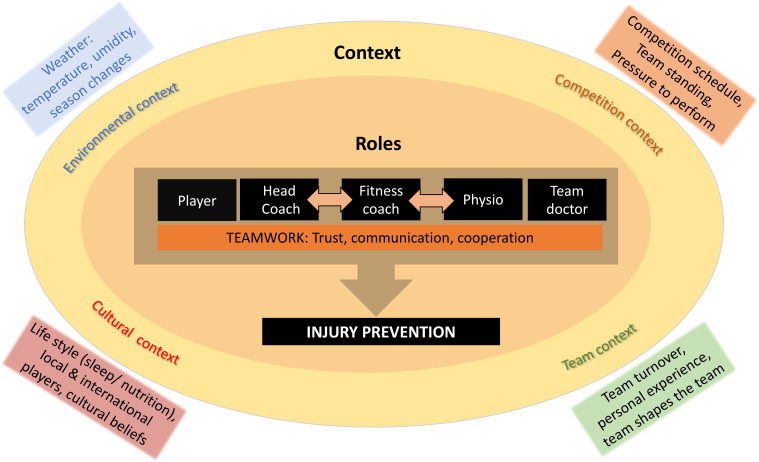

In total, 22 professionals, from diverse nationalities, working with 6 football teams participated in the interviews. All participants were male, and their characteristics are provided in table 1. Three main themes emerged from the analysis and have been entitled as below: Theme 1, Everyone has a role to play in the team; theme 2, It is all about teamwork and 3, The context of Qatar Football. These themes mainly revealed the different stakeholders and their roles in injury prevention, how they work (or should work) together and the contextual factors that influence injury and prevention. Figure 2 illustrates these main themes and how they are interrelated.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics

| Head coaches (N=5) | Fitness coaches (N=5) | Physiotherapists (N=6) | Team doctors (N=6) | |

| Mean age (SD) in years | 46 (4) | 50 (5) | 43 (4) | 53 (4) |

| Mean years of experience in their current role (SD) | 18 (9) | 18 (3) | 17 (2) | 24 (6) |

Figure 2.

Based on our analysis, injury prevention depends on several stakeholders with different roles. For successful injury prevention, all stakeholders must work together as a team. For a team to work effectively, it is important to establish trust, communication and cooperation in a shared-responsibility approach. The Qatari football context is characterised by factors regarding cultural aspects, environmental issues, the team itself and the Qatari league particularities.

Theme 1: everyone has a role to play in the team

All the participants acknowledged the importance of injury prevention and described the different stakeholders and their roles in reducing injury risk. Their background, education and experience shaped their perspectives regarding injury prevention. For example, previous staff members’ experiences were used to justify current strategies for injury prevention. Their function and background also influenced how injury prevention was implemented in practice.

HC: decisions, authority and leadership

The HC is the person that has the authority to make decisions about the implementation and the time dedicated to injury prevention. All participants stated that the HC makes choices that could impact the injury risk of players. For example, an HC can decide whether (1) to select a player to play or not for an official game, independent of the player’s injury risk status or (2) to listen to or take advice from medical staff. From the HC perspective, even if they acknowledge their leadership position, injury prevention is valued, but they do not see themselves involved in the practical side of the implementation process. League standings highly influence their decision-making and the pressure experienced.

Since the HC makes decisions, all participants mentioned the importance of communication between the HC and the staff. This dialogue was essential to developing a good atmosphere within the club. These respondents also note that a good atmosphere leads to better communication and trust between the staff and between the staff and players.

TD: diagnosis, treatment and supervision

As described by the TDs, their primary function was to screen players and provide diagnoses. TDs see themselves mainly involved in the treatment and recovery process, and to a lesser degree, in the prevention process. PHs and FCs mentioned that the TDs guide and supervise the other health professionals. They believe that the medical staff advises the technical staff regarding injuries and related features. All the participants acknowledged that when a player is injured, the physician and head PH take the lead in the decision making. Indeed, the return to play process was used as an example of the importance of the medical staff in the decision-making process, injury management and reinjury prevention.

PH: screening, preventive exercises, cooperation with the FC

PHs believe their primary responsibilities were screening for injury risk and providing individual exercises to players. Indeed, they specified that individual preventive exercises were a vital strategy to strengthen weakened areas in players believed to have an increased risk of injury. PHs are also involved in rehabilitation when a player returns to training after injury. Furthermore, PHs stressed the importance of a trusted relationship with the players, the medical and technical staff. The cooperation between the PH and the FC is essential for injury prevention implementation, especially when it concerns the load management of injured players and exercise prescription.

All stakeholders reported that the FCs play an essential role in communication. Some staff members mentioned that FCs are well defined as conduits between the coach and the medical staff. For example, FCs cooperate closely with the medical staff and the HC to manage the player’s load. However, others would prefer a direct line of communication between the coach and medical staff. This difference seems to be related to how the teams were structured. In some clubs, the participants declared that the FC is the main responsible for injury prevention. Moreover, they specified that the FC works mainly with fit players and is responsible for developing strength and conditioning. In contrast, the interviewees declared that the medical staff work with injured players and the return-to-play process.

Players: awareness, acceptance, compliance and education

Despite not being interviewed, the role of the players was mentioned consistently in the interviews. According to the interviewees, players have an essential role as they are meant to benefit from injury prevention. Injury prevention can only be successful if players accept and comply with the programmes. The players play a role in adopting strategies that can reduce the influence of some risk factors. For example, they make lifestyle choices that can affect their performance and risk of injury, indirectly impacting the entire team’s performance.

General managers: finances and resources

The role of the club’s general management was emphasised by the participant, including the administrative management of the club. It was affirmed that the general manager does not directly role in injury prevention but indirectly through allocating budget and other resources. Moreover, respondents highlighted the importance of team management support in implementing injury prevention. Their management position could put pressure on different stakeholders within the club (table 2).

Table 2.

Stakeholders, stakeholder roles and exemplary quotes on the theme ‘everyone has a role to play in the team’

| Stakeholder | Stakeholder roles | Exemplary quotes |

| Head coach | Decision making Authority Leadership Communication |

PH3: “Some coaches they accept, they accept what we say (…) So, we prevent the injury. You have the other ones they don’t want. No. So, when the injury happens, they understand, but we lose the player.” HC3: “It is the coach (…) I wouldn’t say he is the most important person, but he is the leader. He is important, but I think, in my opinion, he can create a very positive atmosphere and communicate. If we go back to big names, big coaches, they don’t have this common style anymore. They are open. They have 3 or 4 assistants. They talk to the medical staff, and it is very rare when we hear a big coach having a problem with the medical staff because they are open-minded, they listen to them, they listen to you.” PH1: “First is the coach, the head coach. Because right now he is the boss, he even interferes on the timing of the lunch and breakfast.” FC1: “With others (head coaches), no, they do whatever they want. If the team loses, they are fired, so they have to decide and help to make a decision. Some coaches listen more. Some listen less.” HC1: “I know the situation is not so easy because here people demand you to win, and then, you would need your best players. Maybe the player is not ready, so injury prevention is also impacting my decision-making.” |

| Team doctor | Diagnosis Treatment Supervision |

HC1: “The physios and the doctor, if the player gets injured, they are kind of the bosses until he (player) is ready to come back to training with us. So, we are preventing this guy from being re-injured.” FC3: “the doctor makes the diagnosis, and then after that, he makes the treatment with the physio.” “We have the doctor who is the one in charge to supervise them [physiotherapists).” PH4: “Ok, for the doctor, he can give the supplementation, plus establishing diagnosis if something is alarming.” TD4: “We, I mean doctors, physiotherapists, nutritionists, nurses, physiologists, we are in the team to support the coach to make them perform.” |

| Physiotherapist | Screening Preventive exercises Cooperation with fitness coach |

PH4: “If he [player] has a deficiency in some muscle or some part of his body, we try to help him to strengthen and correct it. So, our role is the correction of their weaknesses.” FC1: “Mm oh, for example, we arrived in July we made the screening, so the physios sent me a report giving me that this guy is having a weakness in adductor or a poor control in whatever.” FC3: “Their role [medical staff as a whole] is to treat the players. Treat the players and to also make the injury prevention program inside the medical staff and also to bring them to the field, to the exercise related to the game, related to the training session to be sure they are ready to come for real.” PH2: “I also need to see what the fitness coach is giving because I can give some prevention and the physical coach is also giving other prevention, so I need to balance if I feel that the player is getting a good dose from certain exercise. Then I need to look for other exercises that the physical coach is not giving him. For example, the physical coach is giving more concentric I will advise the player to do some eccentric, some dynamic stretching.” PH1: “With the fitness coach, because we have to know the load of the training to know what kind of exercise we need to implement, we can implement balance exercises for improving proception and coordination before hard training, but we cannot implement strengthening eccentric work before hard training.” |

| Fitness coach | Communication bridge Health & fitness of fit players |

FC2: “…this is our part; it is the monitoring of the load and the health in general. Health in general, not only fitness.” FC3: “Because I see sometimes, I come, and I don’t make injury prevention program, I decide not to do anything for the muscles (…) For me, every day it is load …load…load. So be careful because if you put the load, too much load, you have to manage. This is my advice.” PH4: “…the physical coach is very well managing the load, so your work will become easier because the recovery will be easier, the injuries will be less, the risk will be less.” HC1: “…I use the fitness coaches to be the guy in communication with the medical team. Because their expertise lies here and also here, (…) so the communication for me if the player is complaining, this problem goes more to fitness coach than to medical team. So, this is, I think, because the communication is better through this channel.” PH1: “The link is the fitness coach. We have to talk to the fitness coach, and he transfers to the coach. Then it is vice versa and from the coach to us, medical staff.” TD1: “For example, in the club, the communication is better through the fitness coach that you already met, [name fitness coach] Before it was direct with the coach. (…) I prefer discussing with the coach. Because he is the person to decide.” |

| Player | Acceptance Compliance Education |

PH2: “I think the player should also be involved. They need to know that they are a major factor in the injury if they don’t rest well, if they don’t recover well, if they don’t give good intensity in training, then they are compromising their performance and their level, their competition. Yes, this is a very important factor.” PH1: “Because since 2011, I tried to do many things, but the player didn’t follow us, you know?! About lifestyle: when they eat, when they have to sleep, their recovery. Because, no, it’s not that we don’t talk, we talked with that to the players. (…) they say we agree. We will do that. Then, after one week when we ask again: what did you do? How was it? They have the same lifestyle as before, especially the local players.” HC2: “Education for prevention, I think it is important that the players understand ‘’the why’’. This is very much necessary, …” TD2: “The most important thing: the players are aware of this (…) the players accept it (…) they accept because they are aware. I think they have the knowledge or the… I think all the system is centralized with Aspetar and Aspire; I think they have this knowledge about prevention.” |

| General manager | Budget Resources |

TD1: “Managers, because they give money, they can influence the decision making; try to communicate with the coach sometimes and also with the player.” |

Theme 2: it is all about the teamwork

All stakeholders have an individual role in prevention and acknowledge that they must work together. In our study, various aspects were stated as influencing effective teamwork. Most participants highlighted the need for trust, communication, cooperation and education to sustain successful collaboration. The lack of such team features was also mentioned as a challenge for injury prevention. The need to work as a team leads to one critical factor cited by the participants: communication. All participants described the importance of sharing information and knowledge and engaging in an open dialogue with other staff members and players. For the participants, communication is a means to facilitate cooperation, support each other, share their opinions from their expertise, and establish a shared responsibility toward injury prevention (table 3).

Table 3.

Main codes and exemplary quotes on the theme “It is all about teamwork”

| Main codes | Quotes |

| Teamwork |

TD1: “It is not really one boss. It is a group, teamwork, yes. Because the fitness coach is performing the warm-up, I don’t interfere too much but sometimes we can suggest exercises for groin or hamstring injuries prevention that he could integrate… but he is responsible.” FC1: “There is no one person… mm we are all involved in the same thing, each one has his own area, the doctor is the doctor, the physio is the physio, so each one provides the information from his area. We gather all the information together, and then we decide, depending on the case.” Ph3: “We are all part of the prevention process. Start with the players, the coaches, the fitness coach, the medical staff, the technical staff. We are all responsible.” TD4: “So, the prevention is a teamwork, like many other things; performance is a teamwork, and recovery is a teamwork.” HC3: “Who has the main responsibility? I think it cannot be one person. I don’t think it can. It is all of us. All of us. We have to take it. If someone is injured, we cannot throw the ball and say, you are responsible, we have to be with him [the player), and we have to take responsibility, all of us.” |

| Trust |

Ph4: “The trust between the physio and the player is very important. With this, you can prevent any injury. Because if you feel he doesn’t have confidence in you, he will hide, he will not say: I have tiredness, I have pain, or I am not comfortable.” HC4: “I have a lot of confidence in the doctor [name doctor] and first physio at the club. I know that they are very good professionals they will take care a lot, this is very important.” |

| Cooperation |

TD2: “First, they need to be altogether from both medical and technical staff sides. Just imagine as if the medical staff wants to do some prevention, but the technical staff is thinking of a different idea and focus. This might be challenging. But if it is important to do, both the technical and medical staff together and they want to do the same thing, to understand this is the best way to do it.” FC2: “… all the involved supporting staff around the player could have different ways to approach it, to do it, but all are involved in the injury prevention.” PH2: “Some of them they come, and they ask for our advice for help, some of them whatever you say they hear from one ear, and it goes from the other so… it is difficult to implement something when the other part is not willing to cooperate it is very difficult.” |

| Communication |

PH2: “I think that you need to have a good understanding of good communication with the team, medical, technical, administrative staffs. They all need to sit together and discuss this issue and listen to each other, you know, questions like ‘’what do you feel is better?’’ or what about the training load?’’, ‘’what about the rest days?’’, ‘’do you think this program is good enough?’’, ‘’should we do double, or should we do a single training daily session?” FC3: “Once the physical training is our job, then we need to convince the coach, ‘’this player can train, this one cannot’’, ‘’this player can play and this player cannot, he is not ready to play the match’’. Once you convince the coach and you have arguments that what you are saying is true, you also reduce the risk. If you cannot convince the coach that this player is not ready to play, you also increase the risk of injury.” HC1: “… related to this, the communication in my experience is important because the coach is the guy in control of everything. it is a little bit humiliating when there is no direct contact or communication with the first coach… mm, so it is good to have a direct communication lane.” |

| Education |

HC2: “Communication, talking to them [the players), not from us, maybe from people like you from(pointing at the interviewer who is a scientist, working in a sports medicine hospital)… Because ok the coach, they always look at him as a coach give them advice, he is someone they see every day, but when it comes from a specialist. specialist, like one of you guys, comes from Aspetar, a special day just for… and the risk of injuries show them examples on the videos, give them like… I don’t know examples like the history of players.” Ph4: “Is bringing meeting with all coaches, physical coaches and medical staff and presenting this, this is our protocol, and we want to do this at least one time per week, it will be like 20 min or 30 min. And this is very important, and we make an education session for them with the presentation, all coaches we invite them, we present them our project, ‘’we were working on this for years, and this is very helpful, with statistics and we explain for them the importance of such a program’’.” |

Theme 3: the context of Qatar football

Many participants of this study had previous experiences working in other countries, clubs, sports and performance levels. An overarching concept presented during the interviews was the Qatari football context: cultural aspects, environmental issues and the particularities of the Qatari league/teams. Contextual factors were mentioned as part of the injury and prevention processes.

Cultural context

Many participants mentioned general lifestyle aspects that they related to culture. These lifestyle habits differ between players. Respondents distinguished two types of players regarding lifestyle habits. This was sometimes presented by comparing local players (born in Qatar or resident in Qatar since the youth age) and international players (coming to Qatar specifically for a professionally football contact)—saying that some ‘players are not true professionals’ because they don’t have the same attitude to take care of themselves; some have other occupations and priorities. Sleep and nutrition habits were often mentioned, linking their impact on performance and injuries. These habits in themselves can also result in fatigue. Smoking was also stated as a ‘bad’ habit related to culture and impacting health and performance. Some of these habits were mentioned to be part of their culture. For example, participants mentioned Ramadan intermittent fasting, its impact on sleep and nutrition, and the potential impact on performance and injury risk.

Environmental context

The central theme regarding the environment was the weather. The weather in Qatar, especially in summer, is scorching and very humid for several months. The importance of hydration and scheduling outside training activities were regularly mentioned. The weather conditions can also lead to bad quality of the training fields and hydration problems for the players. Also, respondents noted that they think the competitions start too early [early summer, when the weather is scorching and can be very humid]. Because of that, they need to prepare during summer when the temperatures are high and deal with the heat and dehydration.

Competition context

The respondents highlighted the increased number of matches/competitions compared with previous seasons, which resulted in a high load on the players. The number of participating leagues’ teams rose from 14 to 18, and one friendly sponsored championship was introduced during the past 2 years. All respondents stressed the importance of managing player load. While the match schedule is not flexible, training can be. The participants mentioned the importance of personalised load adjustment and that training should ‘be specific for each player’. The constant pressure to win was highlighted, and some respondents mentioned that this pressure could be higher in Qatar than in previous working experiences. The league standings influence the pressure to perform, leading to decisions that increase the risk of injuries. The results of the team in the competition also impact teamwork. Due to the performance outcomes, some teams’ constant turnover of HC or staff hampers cooperation or leads to inconsistencies in injury prevention strategies.

Team context

Our participants also emphasised some contextual factors of the team itself. They believed that communication and cooperation are necessary, but who is part of the team shapes the team. The individuals and their experience and education influenced the implementation of injury prevention. Professionals who already had experience with injury prevention strategies in other clubs and previous jobs or had the topic as part of their education were more willing to develop preventive interventions. So, the individual experience with injury prevention could help to support or hamper the implementation. Having listened to professionals with different teams, it was clear those in the team dictate injury prevention, especially the HC, who can facilitate or hinder the implementation of preventive strategies (table 4).

Table 4.

Main codes, subcodes and exemplary quotes on the theme ‘the context of Qatar Football’

| Main codes | Subcodes | Quotes |

| Cultural context | Lifestyle Religious background Nutrition Sleep pattern |

TD3: What time the player goes to sleep at 4 o’clock or 6 o’clock (am). During Ramadan, it is 7/8 am, and here we come for training at 3 (pm). No breakfast, no lunch the player is coming to training only with nothing in his stomach, (…) The quality, this is the first part of lifestyle including the sleep, the hydration, the nutrition, they don’t take care of all of this. This is my opinion.” Ph3: “The lifestyle. The lifestyle here is like a reverse lifestyle. Lack of sleeping, and I know he doesn’t feel like he has energy. It is like mmm I don’t know; he needs more energy for work, more energy for… He cannot give himself more than he can, or what you ask him. So many injuries happen because of lack of concentration, and lack of energy. And we have other players. They have a good lifestyle. The big number I don’t know the percentage, but many players’ lifestyles are not good. Not good. It’s a risk factor.” FC3: “Lifestyle. If they go to bed at 3 am, Then at 3 pm, they wake up. At 3 in the afternoon, they take only one bread and one coffee, and they come directly to the training session. This is Arabic culture.” Ph2: “It’s two parts, you know. With professional players, it’s very easy, very easy to implement because you give them one program, they will follow by the book you know. For… they are supposed to be professional, but I will call them ‘’local players’’. You give the program he will do it for one week, and then he will start to skip two, three days.” |

| Environmental context | Climate Humidity Heat |

Ph1: “Mm, the weather. The field, quality of the grass. The grass, for example, is ok. Right now, we are training in Aspire. The grass is good is soft, but before in (name club), it was too hard. “Football shoes, I don’t like many football shoes, because I was a football player, and in my opinion the new football shoes it is not adequate for this kind of weather or field. I mean because it is too hot, so the field is… I mean, it is dry, it is hard, and they are using the same football shoes like in Europe.” TD2: “So, it can be the field because, for example, in the last game, everybody told me that ‘I have pain in the tendons. The field wasn’t very technical, very stable (…) So, this is a little tough for athletes.” HC1: “It s was the round that they played outdoors, and they played the 1st rounds in an airconditioned stadium with a temp of 19 degrees [Celcius). And last weekend was the 1st round which we played outside with a temperature of 40 degrees and 80% humidity. So 90 min full action, and we had a lot of injuries. In these conditions… So, we prepare a plan on how we can minimize the risk of injuries and fatigue, and I think fatigue related to heat is probably, here, the biggest factor.” |

| Competition context | League Training and load |

HC1: “So, it depends on the player, on the situation, it depends where we are in the league, it depends on the importance of the game. So, it is a lot of things. Maybe it is the last game of the season, you need to win, so you take the chance. Maybe now it’s the beginning of the season, so I don’t want any player to have a long-term injury. So, it is cleverer to listen to the guys and be careful, because it is a long way to the end of the season and we don’t want to lose a player at this period. Maybe when it is closer to the end, maybe you take more risks, but at this stage in time, I think it’s the way you play the game.” Ph4: “Recovery for regeneration, physical regeneration, they don’t have enough time for this thing. And also, the more important thing is, if you want to work, for example, the prevention in our case, every 3 days we have a game. This is impossible, even if you ask the coach. The only prevention that we can do, as I told you, is specific (…). But if you tell me you will work Nordic or Copenhagen? He [coach] will not accept it, even the player, he will say ‘I am tired I cannot, exhausted.’” TD2: “Because always here many competitions also. (…) it’s a small cup, big cup, and champions leagues. So, yes many. |

| Team context | Individual experiences Education and background |

FC3: “By years, experience by years. What I have now as experience, I didn’t have it 10 years ago. So, it is something like; you get by the time because you also had a bad experience. Like why I didn’t take the player out before the training? So, I am not going to take the risk that it is going to happen again.” Ph1: “We can explain to everyone, but at the end, each person they can interfere and give their own experience or their comments, related to the prevention.” Ph3: “For me, for example, I have some coaches that are cooperative with us. They understand the staff, all the staff. And, we have some coaches that their schools are ‘’work, work, work, and work.” HC1: “Second is the education. So, I come from a medical background, so I listen to people who have professionalism in these areas. If they say this player is close to being injured, and you have to be careful, then I listen. Sometimes I disagree, but I listen, and normally they are right, and normally, in the long term, it is better to listen.” HC3: “Sometimes coaches, unfortunately, don’t want to listen to anyone, they just think about the result and the matchday, and it is not nice.” Ph3: ‘We had one physical coach, well, his coach also was not easy. He didn’t want to understand what is a prevention program.” |

Discussion

Our study explored the perceptions of critical technical and medical staff members of injuries and their prevention in Qatari professional football. The perceptions of HCs, FCs, TDs (team doctors) and PHs (physiotherapists) were investigated, providing insights into injury prevention and its implementation in Qatar’s specific context of professional football. All respondents described injury prevention as necessary. The main themes demonstrate that injury prevention depends on the teamwork of multiple stakeholders and that it is influenced by a context that stretches from culture to environment.

Taking context into account

Our results align with Bolling et al,15 we found that context matters in how injury prevention is perceived and carried out. The Qatari context (environment, culture) has an influence on injury prevention and also on how team communication is structured. In the case of this study and supported by Verhagen et al19’, the behaviour and lifestyle of individual players are believed to play an essential role in preventing injuries. Indeed, lifestyle habits have been proven to be a risk factor for injuries.20 21 Studies found that well-regulated lifestyle habits like a consistent sleep pattern and high sleep quality result in better performance and fewer injuries in professional football players.22 In this context, Khalladi et al23 showed that 68,5% of a sample of players from the Qatari league had poor sleep quality. This is in line with what the respondents of our study mentioned: many players report poor sleeping patterns. Therefore, understanding the life behaviour of each player is important to address all related injury risk factors. Recently, Tabben et al24 have shown24 that karate athletes, educated on injury prevention and supported by FCs, are more likely to practice injury prevention. The strategy of player education can also be applied in the Qatari football context to improve injury prevention, mentioning the importance of considering lifestyle habits when implementing injury prevention strategies for all staff.

The management’s pressure on the HCs was described as higher in Qatar than in other countries, based on personal HCs’ experience reports. This is illustrated by the constant turnover of coaching staff in the teams. This factor, which does not favour long-term strategies, has been mentioned as potentially leading to more injury-related risk-taking decisions from the HC. This point probably explains HC behaviour regarding training time management—‘Performance comes first’—despite the literature showing that a player’s performance is strongly linked to a player’s health.25 This discrepancy could be tackled by working on the communication between team management and HCs, having a longer-term HC strategy applied in clubs, or suggesting performance directors who can ensure this happens.

Communication and teamwork

The respondents in our study agreed that good communication (among staff and between staff and players) is essential for injury prevention, supporting the existing literature showing that football teams with poor communication suffer more injuries.26 While diverse ideas and experiences can be a significant asset if harnessed well through good communication, shared responsibility and decision-making, the existing diversity can also lead to misunderstandings, which should be considered to avoid miscommunication. For instance, this study showed that the FC plays an essential role in communication and is usually the communication channel between the medical staff and the HC. The medical staff sometimes did not perceive this well, preferring direct contact with the HC. In most cases, this FC communication channel is a consequence of him being usually hired by the HC himself and, most of the time, working with him for a long time. Bizzini et al27 considered communication with the HC in their works. They concluded that information, education and speaking a common language (line of thinking) are essential to prevent professional football injuries. Based on our findings, medical staff would need to take the first step in building a good relationship and communication with the FC in order to get them aligned with their injury prevention strategies. Especially that in the Qatari context, where it is more probable to change the technical team than the medical team.

Communication between the staff and the players is also important. Education and experience can also play a role in this form of communication. In this context, ‘trust’ has also been essential for optimal communication. Thus, coaching and medical staff members should carefully consider that trust between a player and a staff member can help the player comply with prevention exercises or even impact the player’s lifestyle habits. Staff turnover could also negatively impact communication and the trustworthy relations between players and staff.

Our study confirms previous studies that injury prevention is seen as teamwork.28 29 All staff members and, importantly, the players are deemed responsible for the success of the injury prevention implementation process. Every staff member has their task and responsibility for this. A respondent mentioned that if one job is not carried out properly, the circle is not round anymore and injury prevention is not as effective as it should be. So, injury prevention is teamwork, and everyone is involved but with different and complementary tasks. However, the main goal of the technical staff is to win games. At the same time, the medical staff might be focused on the recovery and health of the players.30 Therefore, shared decision making must be considered to keep the sensitive balance of both team performance and player health.30

Methodological considerations

To ensure the quality of our study, several methodological strategies were used.31 32 The study included the multiple perspectives of key staff members with critical roles. However, future studies should also consider interviewing players, as they also have an essential role in injury prevention.

To improve confirmability, there were multiple independent coders for the first interviews. Also, the data analysis was not carried out by the researcher in charge of the data collection, ensuring a neutral view of the data. During the data analysis, constant reflectivity occurred through regular meetings between the coders and the researcher responsible for the data collection.

The study looks at a specific context, namely professional football in Qatar. Competition, player lifestyle, culture and the environment differ between countries and leagues. Consequently, transferring our findings into other sports or other regional contexts should be done with utmost diligence.

Conclusion

In Qatar, injury prevention in professional football is seen as an essential and shared responsibility of all team members, with trust playing a crucial role. However, communication between the medical and technical teams is necessary to implement injury prevention strategies. The FC plays a vital role in convincing the HC—the decision-maker—about the importance of injury prevention. The context of the Qatar football league, specifically the cultural and environmental-related factors, play a role in successfully implementing injury prevention strategies. Such factors need to be acknowledged and considered in any approach. Consequently, a single approach to injury prevention in professional football is unlikely an ideal strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants from (1) the National Sports Medicine Program Department of Aspetar (club doctors and/or physiotherapists), as well as (2) the QSL head and fitness coaches, for their engagement in the study. Our thanks also go to Rima Tabanji for her help in the transcription of the interviews.

Footnotes

Twitter: @evertverhagen, @cs_bolling

Contributors: MT, KC, RB, CB and EV led the project and were responsible for data collection, project management and writing the initial Draft of the manuscript. MT was responsible for conducting the interviews. MW, CB and EV were responsible for the data analysis. MT, CB, EV and KC analysed and interpreted the results. BH, KA, YS and MC have revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version. MT is acting as guarantor. We, therefore, agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. The data are completely confidential.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the AZF Institutional Review Board, Ministry of Public Health of Qatar IRB-AOSM-2020-007. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Pfirrmann D, Herbst M, Ingelfinger P, et al. Analysis of injury incidences in male professional adult and elite youth soccer players: a systematic review. J Athl Train 2016;51:410–24. 10.4085/1062-6050-51.6.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eirale C, Farooq A, Smiley FA, et al. Epidemiology of football injuries in asia: a prospective study in qatar. J Sci Med Sport 2013;16:113–7. 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eirale C, Tol JL, Farooq A, et al. Low injury rate strongly correlates with team success in Qatari professional football. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:807–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hägglund M, Waldén M, Magnusson H, et al. Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:738–42. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stege JP, Stubbe JH, Verhagen E, et al. Risk factors for injuries in male professional soccer: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:375–6. 10.1136/bjsm.2011.084038.185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eliakim E, Morgulev E, Lidor R, et al. Estimation of injury costs: financial damage of english premier league teams’ underachievement due to injuries. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2020;6:e000675. 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.OʼBrien J, Finch CF. Injury prevention exercise programs for professional soccer: understanding the perceptions of the end-users. Clin J Sport Med 2017;27:1–9. 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Brien J, Finch CF. The implementation of musculoskeletal injury-prevention exercise programmes in team ball sports: a systematic review employing the RE-AIM framework. Sports Medicine (Auckland, NZ) 2014;44:1305–18. 10.1007/s40279-014-0208-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen J, Thorborg K, Nielsen MB, et al. Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in men’s soccer: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:2296–303. 10.1177/0363546511419277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldén M, Atroshi I, Magnusson H, et al. Prevention of acute knee injuries in adolescent female football players: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344:e3042. 10.1136/bmj.e3042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bizzini M, Dvorak J. Fifa 11+: an effective programme to prevent football injuries in various player groups worldwide-a narrative review. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:577–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahr R, Thorborg K, Ekstrand J. Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention is not adopted by the majority of champions league or norwegian premier league football teams: the nordic hamstring survey. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1466–71. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chebbi S, Chamari K, Van Dyk N, et al. Hamstring injury prevention for elite soccer players: a real-world prevention program showing the effect of players’ compliance on the outcome. J Strength Cond Res 2022;36:1383–8. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finch C. A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. J Sci Med Sport 2006;9:3–9; 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolling C, van Mechelen W, Pasman HR, et al. Context matters: revisiting the first step of the “sequence of prevention” of sports injuries. Sports Med 2018;48:2227–34. 10.1007/s40279-018-0953-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tee JC, McLaren SJ, Jones B. Sports injury prevention is complex: we need to invest in better processes, not singular solutions. Sports Med 2020;50:689–702. 10.1007/s40279-019-01232-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhagen E, Bolling C. We dare to ask new questions. are we also brave enough to change our approaches? Transl SPORTS Med 2018;1:54–5. 10.1002/tsm2.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCallum J, Howes D. Defining exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. 2018.

- 19.Verhagen EALM, van Stralen MM, van Mechelen W. Behaviour, the key factor for sports injury prevention. Sports Med 2010;40:899–906. 10.2165/11536890-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahr R, Holme I. Risk factors for sports injuries -- a methodological approach. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:384–92. 10.1136/bjsm.37.5.384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva A, Narciso FV, Soalheiro I, et al. Poor sleep quality’s association with soccer injuries: preliminary data. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2020;15:671–6. 10.1123/ijspp.2019-0185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malone S, Owen A, Newton M, et al. Wellbeing perception and the impact on external training output among elite soccer players. J Sci Med Sport 2018;21:29–34. 10.1016/j.jsams.2017.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalladi K, Farooq A, Souissi S, et al. Inter-relationship between sleep quality, insomnia and sleep disorders in professional soccer players. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2019;5:e000498. 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabben M, Augustovičová D, Coquart J, et al. Karatekas educated on injury prevention and supported by fitness coaches are more likely to practise injury prevention. Biol Sport 2023;40:171–7. 10.5114/biolsport.2023.112089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chamari K, Bahr R. Training for elite sport performance: injury risk management also matters! Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2016;11:561–2. 10.1123/IJSPP.2016-0207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekstrand J, Lundqvist D, Davison M, et al. Communication quality between the medical team and the head coach/manager is associated with injury burden and player availability in elite football clubs. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:304–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bizzini M, Junge A, Dvorak J. Implementation of the FIFA 11+ football warm up program: how to approach and convince the football associations to invest in prevention. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:803–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolling C, Delfino Barboza S, van Mechelen W, et al. Letting the cat out of the bag: athletes, coaches and physiotherapists share their perspectives on injury prevention in elite sports. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:871–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin F, Wu Z, Song B, et al. The effectiveness of multicomponent pressure injury prevention programs in adult intensive care patients: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;102:103483. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dijkstra HP, Pollock N, Chakraverty R, et al. Return to play in elite sport: a shared decision-making process. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:419–20. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract 2018;24:120–4. 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frambach JM, van der CP, Durning SJ. AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research. Acad Med 2013;88:552. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2022-001370supp001.pdf (57.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. The data are completely confidential.