Abstract

Background

Multiple rib fractures are common in blunt chest trauma. Until recently, most surgical rib fixations for multiple rib fractures were performed via open thoracotomy. However, due to the invasive nature of tissue dissection and the resulting large wound, an alternative endoscopic approach has emerged that minimizes the postoperative complications caused by the manipulation of injured tissue and lung during an open thoracotomy.

Methods

Our study concentrated on patients with multiple rib fractures who underwent surgical stabilization of rib fractures (SSRF) between June 2018 and May 2020. We found 27 patients who underwent SSRF using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. The study design was a retrospective review of the patients’ charts and surgical records.

Results

No intraoperative events or procedure-related deaths occurred. Implant-related irritation occurred in 4 patients, and 1 death resulted from concomitant trauma. The average hospital stay was 30.2±20.1 days, and ventilators were used for 12 of the 22 patients admitted to the intensive care unit. None of the patients experienced major pulmonary complications such as pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive rib stabilization surgery with the assistance of a thoracoscope is expected to become more widely used in patients with multiple rib fractures. This method will also assist patients in a quick recovery.

Keywords: Trauma, Rib fractures, Flail chest, Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, Minimally invasive surgical procedures

Introduction

Multiple rib fractures are common in blunt chest trauma, with an incidence of up to 40%. They are also associated with high morbidity and mortality [1,2]. Conventionally, a conservative treatment strategy was considered the best approach for traumatic rib fractures, but surgical rib fixation has become increasingly common in recent years [3]. Surgical stabilization of rib fractures (SSRF) is applied to patients with flail chest who require prolonged ventilator treatment or have organ bleeding due to broken ribs, persistent uncontrolled pain, and chest wall deformities [4,5]. However, awareness of SSRF and training to perform this procedure remain limited. Further evidence of its clinical advantages and disadvantages in operative outcomes and patient recovery is needed to establish SSRF through thoracotomy as a procedure [6].

In recent years, to overcome the shortcomings of SSRF via open thoracotomy, endoscopic and minimally invasive surgical technology has been applied to SSRF. There are several advantages to using a thoracoscope for SSRF, including improved visualization of the fractured ribs and a significant reduction in repair-related injuries to thoracic structures. A guided approach to the injury via thoracoscopy also assists in the identification of unsuspected intrathoracic injuries and retained hemothorax. The smaller incision needed for thoracoscopic surgery, compared to open thoracotomy, also significantly benefits the efficacy of inpatient rehabilitation.

In this study, we will report findings from patients with multiple rib fractures and flail chest who underwent minimally invasive SSRF (MISSRF) using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) technology from June 2018 to May 2020.

Methods

Study design

Data were collected from patients who presented to our trauma center with multiple rib fractures from June 2018 to May 2020. Twenty-seven patients, for whom surgical intervention was indicated, underwent MISSRF using VATS. The patients’ characteristics were analyzed, including sex and age, accident mechanism, injury severity score (ISS), concomitant injuries, surgical record, duration of ventilator use, duration of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, duration of hospitalization, complications, and the need for tracheostomy. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Kyungpook National University Hospital (IRB approval no., 2022-10-020), and the requirement for patients to provide informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the evaluation.

Surgery indication and strategy

As per the literature, the indications for SSRF in patients with multiple rib fractures were as follows: flail chest requiring mechanical ventilator use, severe rib fracture displacement resulting in definite or strongly suspected organ damage, manifestation of chest wall deformity, and persistent severe pain unresponsive to analgesic drugs and interventional procedures [4-6]. In principle, our indications for MISSRF were not different from those for SSRF. Based on the anatomical location, we decided that MISSRF was appropriate for posterior or lateral rib fractures, especially in the subscapular space. Although thoracoscopic assistance is not suitable for rib fractures in the parasternal or paraspinal area, a minimal incision technique is considered applicable even in such cases.

Rib fixation was not targeted for every fractured rib, but for ribs that were felt to be essential in maintaining structural stability and eliminating the risk of bleeding and organ damage. Preoperative physical examination and imaging studies were used to determine precise targets, and the final decision was made based on the thoracoscopic findings in the operating room.

Surgical method

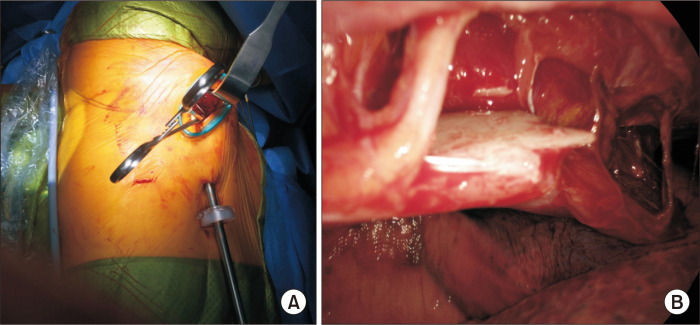

All patients underwent general anesthesia to induce single-lung ventilation, and the intrathoracic cavity was initially examined using thoracoscopy with a 2.0-cm port incision. After exploring the pleural cavity and finding no organ or vessel injuries requiring immediate repair, the rib fracture sites to be fixed were specified. An initial 5.0-cm skin incision was made over the thoracoscopically specified ribs and was extended slightly as necessary. Dissection of the subcutaneous tissue followed, separating the muscle layers along the direction of its fibers. After reaching the skeletal layer, an Alexis wound retractor (Applied Medical Resources Corp., Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA) was installed around the soft tissue to secure the surgical field of view (Fig. 1). Under thoracoscopic guidance through a subcutaneous tunnel, MISSRF using VATS was performed using the RibFix Blu system (Zimmer Biomet, Jacksonville, FL, USA) or ARIX system (Jeil Medical Corp., Seoul, Korea) (Fig. 2). To support aligning the fractured rib segment and to secure a better surgical field of view, we used an Iron Intern® Retractor system (Automated Medical Products Corp., Edison, NJ, USA) as well as various surgical instruments for traction, reduction, and drilling, which were modified or newly manufactured in collaboration with the company.

Fig. 1.

Minimally invasive surgical stabilization of rib fractures with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. (A) The operation field is viewed including a thoracoscope and a small utility incision. (B) The sharp edge of a fractured rib (the reduction and fixation target) is penetrating the parietal pleura.

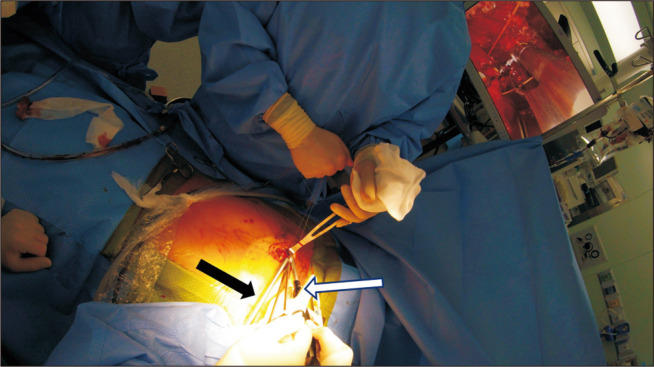

Fig. 2.

Patient with complicated sternal and chondral fractures. Under the thoracoscope (black arrow) guide, the screw is inserted using a right-angled driver (white arrow).

Results

Of the 27 patients who underwent MISSRF using VATS between June 2018 and May 2020, 81% were male and the average age was 56.9±12.9 years (Table 1). No patients underwent conversion to open thoracotomy during MISSRF using VATS. The 2 most common patient injury mechanisms were falling from a height and collision with objects (Table 1). The ISSs of all patients ranged from 9 to 43 (median=17), and 15 patients (56%) had severe trauma with an ISS of 15 or higher. All patients were discharged without major complications except for 1 case of death on postoperative day 1 due to her concomitant injuries; this 89-year-old female patient, with an ISS of 21, had been crushed by a dump truck.

Table 1.

Demographics and injury mechanism of patients with multiple rib fractures

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of cases | 27 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (81) |

| Female | 5 (19) |

| Age (yr) | 56.9±12.9 |

| Trauma mechanism | |

| Motor vehicle | 4 |

| Motorcycle | 4 |

| Bicycle | 1 |

| Pedestrian-motor vehicle | 3 |

| Fall from height | 6 |

| Collision with objects | 6 |

| Other | 3 |

Values are presented as number, number (%), or mean±standard deviation.

Among the 27 patients, 8 patients were diagnosed with a flail chest and 5 had concomitant traumatic brain injuries (Table 2). All patients underwent surgery within 7 days of trauma, except for 1 patient who had surgery on the 11th day due to patient refusal. Four patients underwent emergency surgery (Table 3). Among the 3 patients with concomitant sternal fracture, 2 underwent concurrent sternal reduction and fixation along with MISSRF using VATS. Two patients with moderate lung lacerations on intraoperative thoracoscopic examination underwent pulmonary wedge resection and lung suture procedures, respectively (Table 3).

Table 2.

Combined injuries in 27 patients with multiple rib fractures

| Combined injuries | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Thoracic injuries | |

| Flail chest | 8 |

| Sternal fracture | 3 |

| Lung laceration | 5 |

| Extra-thoracic injuries | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 5 |

| Spinal compression fracture | 5 |

| Pelvic bone fracture | 5 |

| Spleen laceration | 3 |

| Liver laceration | 1 |

Table 3.

Surgery and hospital course in patients who underwent MISSRF using VATS

| No. | Sex | Age (yr) | No. of implanted plate(s) | Additional procedure | Complication | Arrival to time of operation (day) | Time on ventilator (day) | ICU stay (day) | Hospital stay (day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 60 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 30 | ||

| 2 | F | 67 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 27 | ||

| 3 | M | 42 | 1 | 6 | 13 | 16 | 27 | ||

| 4 | M | 47 | 3 | Second MISSRF Plate removal |

0 | 8 | 11 | 44 | |

| 5 | M | 58 | 6 | Plate removal | 1 | 0 | 2 | 16 | |

| 6 | M | 73 | 2 | Sternal fixation | Plate removal | 2 | 0 | 6 | 20 |

| 7 | F | 55 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 31 | ||

| 8 | M | 37 | 2 | Lung wedge resection | Plate removal | 5 | 5 | 20 | 99 |

| 9 | M | 61 | 3 | Sternal fixation | 1 | 0 | 2 | 15 | |

| 10 | M | 75 | 1 | 2 | 30 | 38 | 69 | ||

| 11 | M | 59 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 32 | ||

| 12 | M | 61 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 15 | 59 | ||

| 13 | M | 59 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14 | ||

| 14 | M | 61 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 26 | ||

| 15 | M | 32 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||

| 16 | M | 49 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 35 | ||

| 17 | F | 89 | 3 | Expired | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 18 | M | 66 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 15 | ||

| 19 | M | 70 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 25 | ||

| 20 | M | 59 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 29 | ||

| 21 | M | 45 | 1 | Lung suture | 3 | 0 | 0 | 17 | |

| 22 | F | 64 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 10 | ||

| 23 | M | 62 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 26 | ||

| 24 | M | 58 | 1 | 3 | 11 | 15 | 50 | ||

| 25 | M | 48 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 22 | ||

| 26 | M | 73 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 22 | ||

| 27 | F | 80 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 18 |

MISSRF, minimally invasive surgical stabilization of rib fractures; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery; ICU, intensive care unit; M, male; F, female.

The average hospital stay for 26 patients, excluding the 1 expired patient, was 30.2±20.1 days. Of the 26 patients, 22 patients were admitted to the ICU, and the average ICU stay was 8.77±8.72 days (Table 3). Mechanical ventilation was used in 12 of the 22 patients admitted to the ICU. Four patients required ventilation for >10 days and 1 patient underwent tracheostomy (Table 3).

No patients had major pulmonary complications such as pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome. There were no complications such as wound infection, bedsores, or venous thromboembolism. Major organ failure did not occur in any patient. However, implant-related complications occurred in 4 patients. One patient complained of persistent implant-related skin irritation and the other 3 patients were examined and found to have screws and plates dislodged. All screw and plate dislodgements developed in second or third costal cartilage fractures. All 4 patients underwent implant removal surgery within 5 months postoperatively (Table 3). One patient underwent MISSRF using VATS a second time because of intractable pain at another fracture site after the initial surgery.

Discussion

Multiple rib fractures are one of the most common injuries encountered in trauma centers and are associated with approximately 40% of blunt chest injuries. In our study, 36% of patients with an ISS score of 15 or higher had rib fractures (Table 4).

Table 4.

Incidence of rib fractures and surgical stabilizations at a single trauma center

| Year | Total patients | Total patients with ISS >15 | Patients with rib fractures (%) | Patients with rib fractures and ISS >15 (%) | Patients who underwent SSRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 1,980 | 470 | 295 (14.9) | 186 (39.6) | 13 |

| 2019 | 2,059 | 574 | 332 (16.1) | 195 (34.0) | 24 |

| 2020 | 2,003 | 461 | 280 (14.0) | 161 (34.9) | 17 |

| Total | 6,042 | 1,505 | 907 (15.0) | 542 (36.0) | 54 |

Values are presented as number (%).

ISS, injury severity score; SSRF, surgical stabilization of rib fractures.

Previous treatment of rib fractures in patients with polytrauma was focused on the evaluation of brain or abdominal organ injuries, or on the prevention of various complications including pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and wound infection. Rib fractures were previously considered to be manageable with nonsurgical conservative treatment [6]. However, complications and mortality rates have been shown to rise with an increase in the patients’ age and the number of fractured ribs [6,7]. According to Kent et al. [8], patients with multiple rib fractures of 3 or more and chest abbreviated injury scores ≥3 have significantly higher in-hospital mortality than those who do not, regardless of concomitant injuries [9].

Therefore, the treatment of multiple rib fractures began to turn from conservative treatment to surgical intervention. The expansion of surgical treatment for rib fractures was supported by instruments such as the rib fixation plate system that was developed from various percutaneous traction devices, and intramedullary splints [10]. A study that analyzed 3,467 patients with flail chest from 2007 to 2009 demonstrated that only 0.7% of patients underwent SSRF [11], while another study of 293 patients with flail chest from 2014 to 2016 reported that 7.8% of patients were treated with SSRF [12].

As SSRF has become more accepted by trauma surgeons, there have been ongoing discussions about when and for whom SSRF is indicated. Many studies have demonstrated that patients with 3 or more rib fractures who underwent SSRF showed better clinical outcomes than patients who received conservative treatment in terms of the incidence of respiratory failure, rate of tracheostomy, duration of ventilator usage, and pulmonary capacity over long-term follow-up [13-15].

Conventionally, posterolateral thoracotomy has been used for SSRF. Because of the spiral and curved anatomical nature of ribs, a disadvantage of open thoracotomy is that it provides only a limited 3-dimensional surgical view of multiple fractures. Long skin incisions and muscle divisions that can cause additional tissue damage to the primarily injured chest wall are often required, and extensive surgical manipulation of the injured tissue can lead to unnecessary perioperative damage to intercostal blood vessels and nerves. This manipulation under a restricted surgical view increases the risk of wound infection, failures in postoperative pain management, and ultimately impacts the effectiveness of inpatient rehabilitation [16-19].

To overcome the limitations of SSRF via open thoracotomy, skin incision and tissue dissection should be minimized. The application of selective rib fixations may also provide better clinical outcomes.

For many reasons, applying the VATS technique, which is already commonly used in thoracic surgery, can greatly benefit patients with multiple traumatic rib fractures. First, the presence of organ damage or bleeding foci not found in the preoperative examination can be re-evaluated and resolved. In patients with hemopneumothorax, a blood clot that has not been drained via the indwelling chest tube, can be completely evacuated, and the point of air leakage from injured visceral pleura can be precisely identified and repaired. Second, the type of fracture and status of the fracture can be directly examined from multiple viewpoints with the thoracoscope, which allows easy selection of the ribs that need to be fixed and minimizes the size of the skin incision.

The advantages of rib stabilization using MISSRF using VATS expands the surgical benefits for patients who were previously treated conservatively and assists them in a quicker recovery from traumatic rib fractures.

Conclusion

In this study, MISSRF using VATS was performed in patients with multiple rib fractures and showed acceptable mortality and complication rates. Considering the aforementioned advantages, minimally invasive rib stabilization surgery with the assistance of a thoracoscope is expected to be more widely applicable to patients with multiple rib fractures and flail chest. Long-term follow-up will be required to assess the effects on patients’ recovery status and quality of life after trauma.

Limitation

This study was conducted retrospectively and the patient sample was small; therefore, selection bias may have been an issue. In addition, because of the ambiguous and heterogeneous nature of the trauma events, there was no control group. Further research comparing SSRF with open thoracotomy and SSRF using VATS may be useful.

Acknowledgments

We certify that this study is our own work and all sources of information used in this study have been fully acknowledged.

Funding Statement

Funding This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-forprofit sectors.

Article information

Author contributions

Data curation: CMB, YJL, SCL. Formal analysis: CMB, SCL. Writing–original draft: CMB, SCL. Project Supervisior: SCL. Writing–review & editing: all authors.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sirmali M, Turut H, Topcu S, et al. A comprehensive analysis of traumatic rib fractures: morbidity, mortality and management. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24:133–8. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(03)00256-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulger EM, Arneson MA, Mock CN, Jurkovich GJ. Rib fractures in the elderly. J Trauma. 2000;48:1040–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200006000-00007. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nwiloh J, Walker M, Nwiloh M. Surgical stabilization of blunt traumatic chest wall bony injuries. Niger J Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;1:43–8. doi: 10.4103/2468-7391.195926. https://doi.org/10.4103/2468-7391.195926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan EG, Stefancin E, Cunha JD. Rib fixation following trauma: a cardiothoracic surgeon's perspective. J Trauma Treat. 2016;5:4. doi: 10.4172/2167-1222.1000339. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-1222.1000339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pieracci FM, Majercik S, Ali-Osman F, et al. Consensus statement: surgical stabilization of rib fractures rib fracture colloquium clinical practice guidelines. Injury. 2017;48:307–21. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.11.026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2016.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fokin AA, Hus N, Wycech J, Rodriguez E, Puente I. Surgical stabilization of rib fractures: indications, techniques, and pitfalls. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2020;10:e0032. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.19.00032. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.ST.19.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liman ST, Kuzucu A, Tastepe AI, Ulasan GN, Topcu S. Chest injury due to blunt trauma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:374–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00813-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent R, Woods W, Bostrom O. Fatality risk and the presence of rib fractures. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2008;52:73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Z, Zhang D, Xiao H, et al. The ideal methods for the management of rib fractures. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(Suppl 8):S1078–89. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.04.109. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.04.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bemelman M, Poeze M, Blokhuis TJ, Leenen LP. Historic overview of treatment techniques for rib fractures and flail chest. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2010;36:407–15. doi: 10.1007/s00068-010-0046-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-010-0046-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dehghan N, de Mestral C, McKee MD, Schemitsch EH, Nathens A. Flail chest injuries: a review of outcomes and treatment practices from the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:462–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000086. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naidoo K, Hanbali L, Bates P. The natural history of flail chest injuries. Chin J Traumatol. 2017;20:293–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2017.02.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjtee.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beks RB, de Jong MB, Houwert RM, et al. Long-term follow-up after rib fixation for flail chest and multiple rib fractures. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45:645–54. doi: 10.1007/s00068-018-1009-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-1009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marasco S, Lee G, Summerhayes R, Fitzgerald M, Bailey M. Quality of life after major trauma with multiple rib fractures. Injury. 2015;46:61–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.06.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pieracci FM, Lin Y, Rodil M, et al. A prospective, controlled clinical evaluation of surgical stabilization of severe rib fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:187–94. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000925. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miranda AP, de Souza HC, Santos BF, et al. Bilateral shoulder dysfunction related to the lung resection area after thoracotomy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1927. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001927. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000001927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bemelman M, van Baal M, Yuan JZ, Leenen L. The role of minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis in rib fixation: a review. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;49:1–8. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2016.49.1.1. https://doi.org/10.5090/kjtcs.2016.49.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Song L, Ning S, Xie H, Li N, Wang Y. Recent advances in rib fracture fixation. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(Suppl 8):S1070–7. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.04.99. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.04.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pieracci FM. Completely thoracoscopic surgical stabilization of rib fractures: can it be done and is it worth it? J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(Suppl 8):S1061–9. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.01.70. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.01.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]