Abstract

The health of refugees and migrants is determined by a wide range of factors. Among these, the local political climate in the postmigration phase is an important determinant which operates at interpersonal and institutional levels. We present a conceptual framework to advance theory, measurement and empirical evidence related to the small-area factors which shape and determine the local political climate, as these may translate into variations in health outcomes among refugees, migrants and other marginalised population groups. Using the example of Germany, we present evidence of small-area variation in factors defining political climates, and present and discuss potential pathways from local political climates to health outcomes. We show that anti-immigrant and antirefugee violence is a Europe-wide phenomenon and elaborate how resilience of individuals, communities, and the health system may function as moderator of the effects of the local political climate on health outcomes. Building on a pragmatic review of international evidence on spill-over effects identified in other racialised groups, we present a conceptual framework which incorporates direct effects as well as ‘spill-over’ effects on mental health with the aim to spark further academic discussion and guide empirical analysis on the topic. After presenting and discussing methodological challenges, we call for collective efforts to build coalitions between social sciences, conflict and violence studies, political science, data science, social psychologists and epidemiology to advance theory, measurement, and analysis of health effects of local political climates.

Keywords: Health systems, Public Health, Review

Summary box.

The local political climate is an important determinant of migrant and refugee health in the postmigration phase as the aggregate mood or political opinion of a population may translate into individual or collective action, and shape institutional processes and policies towards integration or exclusion.

Small-area variations in local political climates are important as exclusionary ideologies and violent acts can cluster and negatively impact on mental health of those directly affected, while—through so-called spill-overs—other population groups who identify with the immediate victims may be impaired as well.

We present a framework to further advance theory, measurement and empirical analyses of local political climates and their direct and spill-over effects, and call towards this end for enhanced collaboration between social sciences, conflict and violence studies, political science, data science, social psychologists and social epidemiology.

The health of refugees and migrants is determined by a wide range of premigration, perimigration and postmigration factors.1–3 Among these, the local political climate may be an important determinant which operates at interpersonal and institutional levels. Political climate can be understood as the aggregate mood or opinions of a population regarding current political issues. These opinions may translate into individual or collective action as well as institutional processes, expressed, for example, by more restrictive or inclusionary policies.4 5 Different political climates can coexist in a population, varying across political topics and dimensions. However, public health research has mostly considered national level policies, for example, through analyses of welfare generosity4 6 or through the Migrant Integration Policy Index.7 The more complex relation between small-scale political climates, for instance, at county or district level, and health outcomes at population or subgroup level have largely been ignored.

We argue that, in view of the periodic rise of right-wing nationalism across Europe,8 stronger attention needs to be paid to small-area factors, which shape and determine the local political climate, as these may translate into variations in health outcomes among refugees, migrants and other marginalised population groups. We describe the recent rise in right-wing ideology, present evidence of small-area variation in factors defining political climates using the example of Germany and present and discuss potential pathways from local political climates to health outcomes. We present a framework which incorporates both direct effects and indirect (i.e., ‘spill-over’) effects on mental health as social psychological phenomena and elaborate how resilience of individuals, communities and the health system may function as moderators of such effects.

Right-wing antimigrant attitudes and actions, small-area variations and pathways to health

Political attitudes associated with radical right-wing political orientation can include xenophobia, ethnocentricity, bigotry and racism to varying degrees.9 Extreme forms of these beliefs—combined with unconstitutional and antidemocratic ideology, including violence as means of achieving political goals—are described as right-wing extremism.9 Populist radical right parties have gained political power in several European countries, including Germany, United Kingdom, Austria, Italy and France,8 10 giving rise to right-wing discourses targeting migrants and refugees in particular.8 Anti-immigrant political attitudes affect immigrants not only through politics and policy of political representatives. They may also affect actual behaviour of private persons and citizens and thereby impact the everyday life of migrants and refugees through experiences of hostility,11 social isolation,12 discrimination,13 xenophobia14 and violence.15

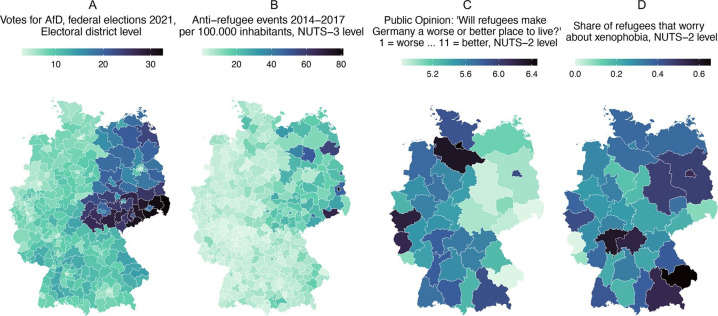

However, anti-immigrant attitudes and actions are not equally distributed but vary across districts, municipalities or even at city and neighbourhood level. In Germany, for example, support for radical right-wing opinion clusters not only by geography (East vs West) (figure 1) but also by socioeconomic characteristics: differences in unemployment rates and feelings of collective deprivation among the 401 German districts explain between 20% and 24% of the variation in district-level extreme right-wing attitudes, electoral support for radical right-wing parties and right-wing crimes.16

Figure 1.

Votes for a Populist Radical Right Party in the General Election 2021 (A), anti-refugee events (including attacks, arson) 2014/2015 (B), public opinion towards refugees in 2020 (C), refugee worries towards xenophobia in 2020 (D), Germany. AfD, Alternative fuer Deutschland; NUTS, The nomenclature of territorial units for statistics. A-D, own visualisations based on secondary data. Data sources: (A): Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2022: Retrieved from: https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/zahlen-und-fakten/bundestagswahlen/340941/waehlerstimmen-in-laendern-und-wahlkreisen/, 15 October 2022. (B): Benček & Straßheim, 2016;15 (C) and (D): Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), 2022: Data for years 1984–2020, SOEP-Core v37, EU Edition, doi:10.5684/soep.core.v37eu.

Political climate can affect mental health of refugees and migrants in two fundamental ways: at (1) institutional and (2) interpersonal levels. First, anti-immigrant attitudes might translate into limited access to health infrastructure at an institutional level. Political actors in more anti-immigrant regions may not offer support for the specific health-related needs of refugees, exert power through inaction to address health needs, make access to services more difficult or even deny services entirely by restricting healthcare entitlements. At macro-level, political climates impact on health through national policies, such as the ‘hostile environment’ policy in the UK,17 healthcare restrictions in Germany18 or restrictive border policies4 and dehumanising encampment and detention at European borders.19 However, empirical links between local political climate and healthcare access using small-area analyses are yet lacking widely.

Second, refugees and migrants can directly experience a hostile and socially exclusive environment at interpersonal level, including discrimination and violence. A large body of literature points to the strong negative effects of social exclusion, discrimination and violence for the mental health and well-being of racialised groups.20–23 Data of the nationally representative Socio-Economic Panel (2022) in Germany show that refugees living in regions with higher antirefugee attitudes express considerably higher worries of xenophobia, and that there is not only an East-West but also a North-South gradient of hostile climates and xenophobia among refugees (see figure 1).

A hostile political climate also clusters—in spatiotemporal dimensions—with incident anti-immigrant violence (see figure 1). In the last three decades, Germany has repeatedly experienced large-scale immigration by refugees. The challenge and responsibility of addressing health and humanitarian needs, as well as long-term integration, was often accompanied by large-scale racist violence against refugees,24 including several pogrom-like incidences during the 1990s25 and violent acts targeting refugee centres in the mid-2010s.26 A total of 160 arson attacks were perpetrated against refugee centres during 2014 and 2015, that is, about one arson attack every 5 days,15 but antirefugee mobilisation in this period also included widespread antimigrant rallies and physical violence.

Although particularly prominent in Germany, attacks against asylum seekers and their accommodations are a Europe-wide issue. For example, 47 attacks against reception centres were reported in Finland in 2015, while Sweden recorded 43 such attacks in the same period.27 Greece has a tragic history of systematic police brutality towards asylum seekers and refugees and recorded 75 racist crimes against migrants or refugees in 2015.27 In the Netherlands, hate crimes and assaults against asylum seekers were reported during protests against new asylum accommodations.27 However, most European countries do not systematically collect data on attacks against asylum seekers and their accommodations.27 While efforts of non-governmental organisations closed this data gap in some countries for 2015/2016, these efforts have not recently been systematically repeated. Antirefugee violence is, thus, highly under-reported,28 and its consequences in terms of population-level health impacts go unnoticed.

‘Spill-over’ effects

Violent acts and hate crimes directly affect the health and well-being of individual victims. However, their impact may extend well beyond the injured or affected individual and negatively impact the mental health and well-being of other population groups through ‘spill-overs’.29 The term ‘spill-over’ refers to any effect of an exposure, for example, violence, beyond those directly exposed to it. This includes indirect effects on not only refugee groups but also migrant or non-migrant groups alike. Not only direct exposure to violence but also indirect exposure, for example, witnessing, hearing or knowing about the victimisation from media reports or peers, is associated with negative mental health outcomes.30 Spill-over effects have been well studied in the context of police killings of Black Americans: the body of evidence strongly suggests that the negative effect of violence against racialised groups unfolds beyond the immediate victims, translating into poorer mental health,31 32 higher suicide rates33 and higher emergency department visits for depressive symptoms34 among Black Americans. Such effects are larger with increasing ‘proximity’—in terms of geography or identity—to the victims of direct violence.31–33 With decreasing ‘proximity’, research challenges arise as quantitative effect measurements may weaken. Overall, data and measurement challenges caution researchers to rely on oversimplified approaches which may lead to misclassification of exposures.35 36

Studies support the theory of spill-over effects in other racialised groups as well. For example, Arabic-named women in the USA showed poorer birth outcomes during a period of rapidly rising anti-Muslim attitudes following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.37 Natural experiments have shown that immigration enforcement and related raids among Latin American immigrants in the USA have been associated with worse birth outcomes among Latina women38 and higher stress and lower self-rated health among indirectly affected adults and children.39

Moderating effects through resilience

The effects of local political climate and racially motivated acts of violence on mental health may vary depending on resources available at individual, community and health system levels.

At an individual level, the concept of resilience has been used to describe the ability of individuals to resist developing mental disorders in the face of adversity or stressful events.40 It is commonly conceptualised within a biopsychosocial model, which encompasses genetic, physiological, psychological and social factors.40 Such psychological resilience has been explored since the 1970s and is considered a key protective factor that helps individuals or groups of people to adapt to, cope with and recover from both acute and chronic situations of trauma, crisis or suffering,41 for example, in light of existential threats, interpersonal or collective discrimination, racism or conflict and violence.

Beyond the individual, community resilience contributes to the mental health and well-being of societies faced with sudden disasters or chronic challenges,42 including violence.43 44 Resources available at community level, particularly relating to different forms of social capital, but also aspects of communication, community competence and economic development, have been identified as being key to an adequate response mitigating and preventing negative health effects.42 As for social capital, this includes, for example, civil society actors who practice solidarity with refugees in the contested political space of immigration. During the ‘summer of migration’, civil society actors developed a sense of social solidarity, prevented negative reactions towards immigrants and refugees through their activities supporting integration and by standing up against racism towards a more inclusive society.45 Beyond individual resources inherent in psychological resilience, refugees may be able to draw on the wider social and economic resources of their community to resist the harmful direct and indirect effects of political climate on mental health. This may include aspects of social trust, a sense of belonging in the community and opportunities for community participation as well as community infrastructure, economic and educational opportunities. Social capital at community level has been identified key protective factor for mental health and well-being of refugees,46 47 and interventions fostering social relationships, ties and networks are effective but under-used tools to enhance community resilience and thereby protect mental health of refugees.48 Strengthening community resilience is also paramount to combat hate and racism in the digital era.49

Health systems, understood as socially constructed complex adaptive system,50 can provide further resources to mediate the potential negative effects of political climate and violence on health. Health system resilience comprises three capacities—absorptive, adaptive and transformative51—which can be mobilised to uphold or restore a systems function. These capacities may operate at different levels (individual, community and system)52 and may be affected by dynamics in other societal sectors (eg, economic sector, political sector) creating complex interactions between sectors and across multiple levels.53 On the one hand, health systems can re-enforce othering54 and exclusion and further amplify negative effects of local political climates through healthcare encounters and interactions at interpersonal level determined by attitudes of healthcare professionals.55 On the other hand, the local political climate may determine the quality and scope of health infrastructure available to refugees,55 while at the structural level, exclusionary ideologies may manifest themselves in form of policies which actively uphold modifiable barriers to healthcare.56 For example, the resilience of the health system for refugees in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic was highly dependent on the constellation and interests of local political actors.57

Individual, community and health system resilience can, hence, be understood as nested levels within a complex adaptive system53 whose relationships among each other and vis á vis the local political climate have so far been insufficiently investigated in the health systems literature.

Advancing the evidence: a conceptual framework and call for action

Despite surging anti-immigrant attitudes and actions,58 there is only little research in Europe23 on the potential population-level health impact of local political climates or spatial clusters of anti-immigrant and antirefugee violence. The potential mental health impact may, as we have shown, also extend beyond immigrant populations and affect other population groups who may be targeted due to their ethnic, political, sexual or religious identity.

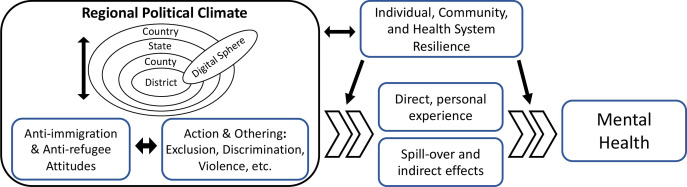

As it is time to reconcile migration and health in Europe,59 we urge researchers to study these effects and related causal chains and pathways. To this end, we provide a simplified and preliminary framework to not only initiate academic discourse but also spark further conceptual and empirical work (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of local political climate and direct and indirect health effects.

The framework regards the local political climate as shaped by a combination of attitudes and actions, with non-linear, reciprocal relationships which may re-enforce or contradict each other. Attitudes can be elicited (eg, verbally expressed) or latent and emerge and relate to the cognitive domain, while actions relate to the behavioural domain.60 The relationship between attitude and action, however, is complex and subjected to several theoretical and methodological considerations, of which the most important one is that there is no one-way simplistic causal relation from one to the other.60

Another layer of complexity is added by the fact that the local political climate is not confined to a distinct geospatial location. Through intersections with the technological sphere, it extends well beyond geography and includes the digital space—as place ‘without places’—in which attitudes are shaped and formed. Especially, virtual hate61 and online othering62 as emerging phenomena affect and reproduce exclusionary political attitudes against refugees63 and may constitute virtual stages of real action. For example, the mobilisation of anti-Muslim attitudes and large-scale violence against Rohingya in Myanmar was evidently fueled by hate speech in social media.64 65 While this is an extreme case, the question in how far local (violent) actions against refugees and immigrants are fueled by digitally produced climates of hate requires stronger empirical analysis. Such analysis entails several methodological challenges66 but may have the potential for early warning or surveillance systems to be developed for violence prevention.

The local political climate, understood as the assemblage of the cognitive, behavioural, spatial and technological sphere, may affect individuals directly through experience of elicited attitudes or behaviour and action at interpersonal, and also at institutional level (e.g., expressed through policies). At the same time, the framework considers potential ‘spill-over’ effects of the political climate on mental health of immigrant or other population groups with proximity (defined by identity or geography). Resilience, at level of individuals, communities and health systems, may be a moderator on the causal pathway for both direct and indirect effects (figure 2).

Methodological and measurement challenges

Public health research could play a significant role by defining, documenting and comparing within and across countries the effects of the local political climate on population health. A central task is the linkage of different data types across disciplines, for instance, socioeconomic large-scale (longitudinal) survey data, health (survey) data, aggregated local and regional indicators on social structures and political sentiment, geocoded social media data and geocoded data on local violence and crime. Such innovative linkage approaches would also help to improve health information systems with respect to refugee and migration health.67 A mix of methodological approaches will be necessary to analyse the complex data required, including big spatial data management procedures to store and preprocess data and small-area estimation techniques to increase the robustness of estimates for lower level regions. Moreover, innovative methods are needed to facilitate the measurement of (local) political climate in the digital sphere, especially in social media. Challenges relate to accessibility of data,68 69 the geoinformation available,70 71 and natural language processing methods for extracting meaning out of unstructured social media and online textual data.72 73 Another challenge refers to the delocalised nature of the digital sphere: if everyone is exposed, no epidemiological assessment is possible. The challenge will hence be to assess regional variation of consumers, producers and/or victims of hate speech and online othering in order to re-localise the exposures and their potential consequences. Qualitative designs may further help to disentangle mechanisms and causal chains of local political climates to health outcomes. They are furthermore instrumental in giving voice to those affected by right-wing antimigrant attitudes and actions, avoiding victimisation and contextualising their agency within discursive fields that are predominantly shaped by power relations, for example, of media, authorities, political and humanitarian organisations and science.74

Last but not least, efforts are required to standardise definitions of anti-immigrant and racist violence, including the set-up of systematic monitoring approaches based on existing cross-national efforts28 to measure the potential direct and indirect population-level health impacts.

Overcoming these measurement challenges, however, will not suffice to generate robust evidence on causal pathways. At the core of the pathways outlined in the conceptual framework is an ecological association, from a small-area contextual exposure (eg, local political climate or intensity of racial violence) to population-level health outcomes among refugees, migrants or non-migrant groups. While it may be argued that the ecological nature limits the investigation of causal pathways per se, we believe that this is the only approach which allows for the identification of population-level determinants of poor (mental) health. Following the rationale of Geoffrey Rose’s seminal paper on aetiology in public health, the concern of study here is much more the identification of the determinants of incidence of poor (mental) health as opposed to the identification of determinants of individual cases with poor (mental) health.75 Studies analysing refugee mental health in contexts where they are exposed to a homogenous level of political climates (or ignoring this factor a priori) will fail to identify it as relevant determinant and create an individualistic fallacy which attributes variation in health to individual-level factors alone. Exploiting the regional variation in local political climates at small-area level can help to identify its causal effects on population-level health outcomes. However, for causal inference to be free of compositional bias, studies need to rule out self-selection of individuals and population groups into contexts. The use of natural experiment designs, if available, or analytical strategies such as instrumental variables, propensity score matching and/or difference-in-difference analysis will be required to ensure that contextual effects of local political climates are studied while minimising compositional bias through selective migration.76

A deeper knowledge of the relationships of political climate and population health may help to design interventions—at societal, community, health system or individual level—to counter exclusionary policies, prevent racist violence or mitigate its negative effects. We call for collective efforts among public health scientists in Europe to build coalitions between social sciences, conflict and violence studies, political science, data science, social psychologists and epidemiology to advance the theory, measurement, and analysis of such relationships.

Acknowledgments

We thank the two reviewers for their constructive comments on our manuscript.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

KB and SK contributed equally.

Contributors: Conceptualisation: KB, SK. Data curation: SK. Formal analysis: SK. Validation: KB, LB. Visualisation: SK. Writing—original draft: KB. Writing—review & editing: SK, LB.

Funding: The work was produced in the scope of the PH-LENS Research Unit (DFG FOR 2928 / GZ: KU 4200 / GZ BO 5233, REPOSOM).

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. See references for data sources under figure 1.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Ziersch A, Due C. A mixed methods systematic review of studies examining the relationship between housing and health for people from refugee and asylum seeking backgrounds. Soc Sci Med 2018;213:199–219. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jannesari S, Hatch S, Prina M, et al. Post-migration social-environmental factors associated with mental health problems among asylum seekers: a systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health 2020;22:1055–64. 10.1007/s10903-020-01025-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2005;294:602–12. 10.1001/jama.294.5.602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juárez SP, Honkaniemi H, Dunlavy AC, et al. Effects of non-health-targeted policies on migrant health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e420–35. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30560-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bozorgmehr K, Jahn R. Adverse health effects of restrictive migration policies: building the evidence base to change practice. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e386–7. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundberg O, Yngwe MA, Stjärne MK, et al. The role of welfare state principles and generosity in social policy programmes for public health: an international comparative study. Lancet 2008;372:1633–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61686-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IOM . Summary report on the MIPEX health strand & country reports. Brussels: International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Office Brussels, Migration Health Division, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mudde C. Three decades of populist radical right parties in western europe: so what? Eur J Polit Res 2013;52:1–19. 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02065.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mudde C. The ideology of the extreme right. Manchester University Press, 2002. 10.7228/manchester/9780719057939.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muis J, Immerzeel T. Causes and consequences of the rise of populist radical right parties and movements in Europe. Curr Sociol 2017;65:909–30. 10.1177/0011392117717294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Louis WR, Duck JM, Terry DJ, et al. Why do citizens want to keep refugees out? threats, fairness and hostile norms in the treatment of asylum seekers. Eur J Soc Psychol 2007;37:53–73. 10.1002/ejsp.329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strang AB, Quinn N. Integration or isolation? refugees’ social connections and wellbeing. J Refug Stud 2021;34:328–53. 10.1093/jrs/fez040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edge S, Newbold B. Discrimination and the health of immigrants and refugees: exploring Canada’s evidence base and directions for future research in newcomer receiving countries. J Immigr Minor Health 2013;15:141–8. 10.1007/s10903-012-9640-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marfouk A. I’m neither racist nor xenophobic, but: dissecting European attitudes towards a ban on Muslims’ immigration. Ethnic and Racial Studies 2019;42:1747–65. 10.1080/01419870.2018.1519585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benček D, Strasheim J. Refugees welcome? A dataset on anti-refugee violence in Germany. Research & Politics 2016;3:205316801667959. 10.1177/2053168016679590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rees JH, Rees YPM, Hellmann JH, et al. Climate of hate: similar correlates of far right electoral support and right-wing hate crimes in Germany. Front Psychol 2019;10:2328. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiam L, Steele S, McKee M. Creating a “ hostile environment for migrants ”: the British governme’t's use of health service data to restrict immigration is a very bad idea. Health Econ Policy Law 2018;13:107–17. 10.1017/S1744133117000251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozorgmehr K, Wenner J, Razum O. Restricted access to health care for asylum-seekers: applying a human rights lens to the argument of resource constraints. Eur J Public Health 2017;27:592–3. 10.1093/eurpub/ckx086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orcutt M, Mussa R, Hiam L, et al. Eu migration policies drive health crisis on greek islands. Lancet 2020;395:668–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33175-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devakumar D, Selvarajah S, Shannon G, et al. Racism, the public health crisis we can no longer ignore. Lancet 2020;395:e112–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31371-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0138511. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, et al. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 2014;140:921–48. 10.1037/a0035754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bracco E, De Paola M, Green C, et al. The spillover of anti-immigration politics to the schoolyard. Labour Economics 2022;75:102141. 10.1016/j.labeco.2022.102141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bozorgmehr K, Biddle L, Razum O. Das jahr 2015 und die reaktion des gesundheitssystems: bilanz aus einer resilienzperspektive. In: Handbuch Migration und Gesundheit. Bern: Hogrefe, 2021: 243–56. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung . 25 jahre brandanschlag in solingen bonn: bundeszentrale für politische bildung. 2018. Available: www.bpb.de/politik/hintergrund-aktuell/161980/brandanschlag-in-solingen

- 26.Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung . Straf- und gewalttaten von rechts: was sagen die offiziellen statistiken? Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: Bonn, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights . Current migration situation in the EU: hate crime. Vienna, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Network Against Racism . Racist crime and institutional racism in europe: ENAR shadow report 2014-2018. Brussels, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharkey P. The long reach of violence: a broader perspective on data, theory, and evidence on the prevalence and consequences of exposure to violence. Annu Rev Criminol 2018;1:85–102. 10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmerman GM, Posick C. Risk factors for and behavioral consequences of direct versus indirect exposure to violence. Am J Public Health 2016;106:178–88. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtis DS, Washburn T, Lee H, et al. Highly public anti-black violence is associated with poor mental health days for black Americans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118:e2019624118. 10.1073/pnas.2019624118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eichstaedt JC, Sherman GT, Giorgi S, et al. The emotional and mental health impact of the murder of George floyd on the US population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118:e2109139118. 10.1073/pnas.2109139118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyriopoulos I, Vandoros S, Kawachi I. Police killings and suicide among black americans. Soc Sci Med 2022;305:114964. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Das A, Singh P, Kulkarni AK, et al. Emergency department visits for depression following police killings of unarmed african americans. Soc Sci Med 2021;269:113561. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, et al. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet 2018;392:302–10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nix J, Lozada MJ. Police killings of unarmed black Americans: a reassessment of community mental health spillover effects. Police Practice and Research 2021;22:1330–9. 10.1080/15614263.2021.1878894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauderdale DS. Birth outcomes for arabic-named women in California before and after September 11. Demography 2006;43:185–201. 10.1353/dem.2006.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso AM. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:839–49. 10.1093/ije/dyw346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez WD, Kruger DJ, Delva J, et al. Health implications of an immigration raid: findings from a Latino community in the midwestern United States. J Immigr Minor Health 2017;19:702–8. 10.1007/s10903-016-0390-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davydov DM, Stewart R, Ritchie K, et al. Resilience and mental health. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:479–95. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur Psychol 2013;18:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, et al. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:127–50. 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmed R, Seedat M, van Niekerk A, et al. Discerning community resilience in disadvantaged communities in the context of violence and injury prevention. South African Journal of Psychology 2004;34:386–408. 10.1177/008124630403400304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sousa CA, Haj-Yahia MM, Feldman G, et al. Individual and collective dimensions of resilience within political violence. Trauma Violence Abuse 2013;14:235–54. 10.1177/1524838013493520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamann U, Karakayali S. Practicing willkommenskultur: migration and solidarity in Germany. Intersections 2016;2. 10.17356/ieejsp.v2i4.296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pieloch KA, McCullough MB, Marks AK. Resilience of children with refugee statuses: a research review. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne 2016;57:330–9. 10.1037/cap0000073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lecerof SS, Stafström M, Westerling R, et al. Does social capital protect mental health among migrants in Sweden? Health Promot Int 2016;31:644–52. 10.1093/heapro/dav048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Villalonga-Olives E, Wind TR, Armand AO, et al. Social-capital-based mental health interventions for refugees: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2022;301:114787. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jakubowicz A, Dunn K, Mason G, et al. Cyber racism and community resilience. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. 10.1007/978-3-319-64388-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Savigny D, Adam T. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blanchet K, Nam SL, Ramalingam B, et al. Governance and capacity to manage resilience of health systems: towards a new conceptual framework. Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;6:431–5. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ziglio E. Strengthening resilience: A priority shared by health 2020 and the sustainable development goals. Copenhagen, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bozorgmehr K, Zick A, Hecker T. Resilience of health systems: understanding uncertainty uses, intersecting crises and cross-level interactions Comment on “ government actions and their relation to resilience in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic in New South Wales, Australia and Ontario, Canada. ” Int J Health Policy Manag 2022;11:1956–9. 10.34172/ijhpm.2022.7279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grove NJ, Zwi AB. Our health and theirs: forced migration, othering, and public health. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:1931–42. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jahn R, Biddle L, Ziegler S, et al. Conceptualising difference: a qualitative study of physicians’ views on healthcare encounters with asylum seekers. BMJ Open 2022;12:e063012. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bozorgmehr K, Razum O. Lost in ambiguity: facilitating access or upholding barriers to health care for asylum seekers in germany? In: Korntheuer A, Pritchard P, Maehler D, et al., eds. Refugees in Canada and Germany: From Research to Policies and Practice. GESIS-Schriftenreihe. Cologne: GESIS Leibniz-Institute for Social Sciences, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Biddle L, Jahn R, Perplies C, et al. COVID-19 in collective accommodation centres for refugees: assessment of pandemic control measures and priorities from the perspective of authorities. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2021;64:342–52.:1. 10.1007/s00103-021-03284-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koehler D. Right-wing extremism and terrorism in europe: current developments and issues for the future. PRISM 2016;6:84–105. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blanchet K. Time to reconcile migration and health in Europe. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022;21:100500. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schuman H, Johnson MP. Attitudes and behavior. Annu Rev Sociol 1976;2:161–207. 10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.001113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kilvington D. The virtual stages of hate: using goffman’s work to conceptualise the motivations for online hate. Media, Culture & Society 2021;43:256–72. 10.1177/0163443720972318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harmer E, Lumsden K. Online othering: an introduction. In: Lumsden K, Harmer E, eds. Online othering: exploring digital violence and discrimination on the web. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ozduzen O, Korkut U, Ozduzen C. Refugees are not welcome’: digital racism, online place-making and the evolving categorization of syrians in turkey. New Media & Society 2021;23:3349–69. 10.1177/1461444820956341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brooten L. When media fuel the crisis: fighting hate speech and communal violence in myanmar. In: Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities. Springer, 2020: 215–30. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fink C. Dangerous speech, anti-muslim violence, and facebook in myanmar. J Int Aff 2018;71:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crosset V, Tanner S, Campana A. Researching far right groups on Twitter: methodological challenges 2.0. New Media & Society 2019;21:939–61. 10.1177/1461444818817306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bozorgmehr K, Biddle L, Rohleder S, et al. What is the evidence on availability and integration of refugee and migrant health data in health information systems in the WHO european region? Copenhagen 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kennedy H, Moss G. Known or knowing publics? social media data mining and the question of public agency. Big Data & Society 2015;2:205395171561114. 10.1177/2053951715611145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Batrinca B, Treleaven PC. Social media analytics: a survey of techniques, tools and platforms. AI & Soc 2015;30:89–116. 10.1007/s00146-014-0549-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rieder Y, Kühne S. Geospatial analysis of social media data-A practical framework and applications. computational social science in the age of big data concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications. DGOF schriftenreihe. Köln: Herbert van Halem Verlag, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nguyen HL, Tsolak D, Karmann A, et al. Corrigendum: efficient and reliable geocoding of German Twitter data to enable spatial data linkage to official statistics and other data sources. Front Sociol 2022;7:995770. 10.3389/fsoc.2022.995770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Skaik R, Inkpen D. Using social media for mental health surveillance. ACM Comput Surv 2021;53:1–31. 10.1145/3422824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mozafari M, Farahbakhsh R, Crespi N, eds. A BERT-based transfer learning approach for hate speech detection in online social media. International Conference on Complex Networks and Their Applications; 2019: Springer, [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sigona N. The politics of refugee voices: representations. In: The Oxford handbook of refugee and forced migration studies. 2014: 369–82. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 1985;14:32–8. 10.1093/ije/14.1.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Biddle L, Hintermeier M, Costa D, et al. Context and health: a systematic review of natural experiments among migrant populations. Public and Global Health [Preprint]. 10.1101/2023.01.18.23284665 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. See references for data sources under figure 1.