Abstract

Cuprate high-Tc superconductors are known for their intertwined interactions and the coexistence of competing orders. Uncovering experimental signatures of these interactions is often the first step in understanding their complex relations. A typical spectroscopic signature of the interaction between a discrete mode and a continuum of excitations is the Fano resonance/interference, characterized by the asymmetric light-scattering amplitude of the discrete mode as a function of the electromagnetic driving frequency. In this study, we report a new type of Fano resonance manifested by the nonlinear terahertz response of cuprate high-Tc superconductors, where we resolve both the amplitude and phase signatures of the Fano resonance. Our extensive hole-doping and magnetic field dependent investigation suggests that the Fano resonance may arise from an interplay between the superconducting fluctuations and the charge density wave fluctuations, prompting future studies to look more closely into their dynamical interactions.

Subject terms: Superconducting properties and materials, Phase transitions and critical phenomena, Electronic properties and materials

Cuprate superconductors are known for their intertwined interactions and coexistence of competing orders. Here, the authors observe a Fano resonance in the nonlinear THz response of La2-xSrxCuO4, which may arise from a coupling between superconducting and charge-density-wave amplitude fluctuations.

Introduction

Interactions between the intrinsic degrees of freedom of a solid (e.g., charge, spin, orbital, and lattice) often lead to interesting physical properties or phenomena, such as BCS superconductivity, colossal magnetoresistance, and have been key to understanding and predicting novel phases of matter including topological insulators and unconventional superconductivity. Often, the signatures of these interactions manifest in the dynamical response of a system. For example, electron-phonon interaction may significantly renormalize the quasiparticle (electronic) dispersion, introducing kinks into the latter, which has been the subject of extensive research in the case of high-Tc superconductors1–3. The same interaction may also introduce discontinuities into the phonon dispersion, a well-known example being the Kohn anomaly arising from an electronic instability driven by Fermi surface nesting. When a discrete excitation interacts with a continuum of excitations, another kind of discontinuity could manifest in its light-scattering amplitude:4,5 an asymmetric amplitude profile may develop across the discrete mode, with one side showing a pronounced suppression (a.k.a. anti-resonance) (Fig. 1b). Known as the Fano resonance or the Fano interference, this quantum mechanical phenomenon is closely related to a classical counterpart, i.e., the driven coupled harmonic oscillators model4. In this classical model, if one oscillator is heavily damped (therefore analogous to a continuum of states) while the other is underdamped, the system would exhibit an anti-resonance where the amplitude of the driven oscillation goes through a minimum while its phase undergoes a negative π jump (opposite to the direction of a resonant phase jump) as a function of the driving frequency. In fact, the negative π phase jump is also intrinsic to a Fano resonance, although this particular phase signature has rarely been experimentally evidenced. In this work, we show that a careful extraction of the optical phase information from a terahertz-driven cuprate high-Tc superconductor allows us to uncover a Fano interference in its nonlinear terahertz response (Fig. 1a). In contrast, we do not find a similar effect in the conventional s-wave superconductors NbN. Such a contrast may arise from the presence of intertwined interactions in cuprate high-Tc superconductors.

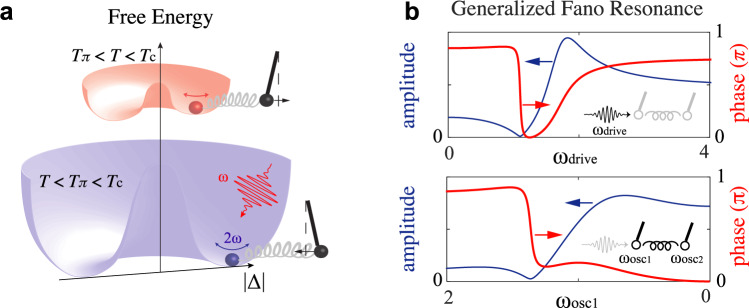

Fig. 1. Nonlinear terahertz spectroscopy of d-wave superconductors.

a An illustration of the amplitude oscillation of the superconducting order parameter (2ω) driven by electromagnetic radiation (ω) and its coupling to another collective mode (black pendulum) at temperatures above and below Tπ, i.e., the anti-resonance temperature. b The generalized Fano resonance model describes the interference between a driven damped (continuum) mode and an underdamped (discrete) mode, here represented as oscillators 1 and 2, respectively. The Fano resonance/interference is characterized by the asymmetrical line shape of the amplitude response (blue), and also by the negative π jump in the phase response (red), a.k.a. the anti-resonance. Upper panel: in typical spectroscopy experiments, the electromagnetic driving frequency (ωdrive) is swept. Lower panel: in our experiment the driving frequency is fixed, but the resonance frequency of oscillator 1 (ωosc1) is swept. Here, oscillator 1 represents the superconducting fluctuations, whose energy scale is a function of temperature. By sweeping temperature from 0 towards Tc, the energy of the superconducting fluctuations decreases from maximum to zero. We chose the direction of the ωosc1 axis as shown so that it corresponds to a temperature axis that increases to the right. Note, however, that sweeping temperature is not entirely equivalent to sweeping driving frequency, as additional parameters like the damping constant may depend on temperature. Details of the generalized Fano resonance model can be found in Supplementary Materials S8.

A microwave/terahertz-driven superconductor has been known to exhibit strong nonlinearities across Tc, particularly in terms of third harmonic generation (THG)6–9. Its origin has been suggested to relate to collective fluctuations inside a superconductor10–13, including the superconducting amplitude fluctuations (i.e., Higgs mode14–18), the Josephson plasma mode/the nonlinear Josephson current, and also the charge fluctuations (a.k.a. the BCS response, not to be confused with charge density wave fluctuations). In particular, for a conventional superconductor, the energy scale of the Higgs mode and the charge fluctuations follow a similar mean-field temperature dependence as 2Δ(T)7,10,17. They are expected to become resonantly driven when 2Δ(T) = 2ω, where ω is the frequency of the terahertz field. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish between these different contributions based on the temperature dependence of THG. Nevertheless, for a BCS superconductor in the clean limit, different polarization dependence has been predicted for THG arising from each mechanism (see Supplementary Materials S6 for a detailed discussion)10–13, providing a potential way for distinguishing the origin of THG in an experiment.

One caveat about such an experiment is that dissimilar to most spectroscopy experiments in which the electromagnetic driving frequency is swept relative to an excitation fixed in energy, here the driving frequency is kept constant but the energy of the superconducting fluctuations, given by 2Δ(T), is swept by varying temperature (Fig.1b). For a reasonably small driving frequency ω, as we increase the temperature from 0 the superconducting fluctuations are first driven below resonance (i.e., 2ω < 2ΔT~0) and then above (i.e., 2ω > 2ΔT~Tc ~ 0). As illustrated in Fig. 1b, this means that as we heat up a superconductor we expect the THG phase to evolve positively across a resonance and negatively across an anti-resonance. For cuprate high-Tc superconductors where 2Δ, according to some experimental interpretations19,20, remains sizeable at Tc, the resonance of the superconducting fluctuations might move beyond Tc for the small terahertz driving frequency of 0.7 THz used in our experiment. Here, the use of a narrow-band multi-cycle terahertz field generated from a superradiant high-field terahertz source TELBE allows us to precisely extract the phase information required for understanding any resonance or anti-resonance behavior of a periodically driven superconductor.

Results

Figure 2a shows the typical THG response of a superconducting cuprate thin film. In the raw transmission data, the THG response (3ω = 2.1 THz) is superposed on top of the transmitted linear driving field (ω = 0.7 THz), which can be separated from each other using Fourier lowpass and highpass filters. From their respective waveforms, we obtain their amplitude (A) and phase (Φ) by fitting them to the equation

| 1 |

(only A, Φ, c are fitting parameters) which allows us to extract the relative phase between the THG response and the linear drive: (the factor 3 in front of Φω accounts for the fact that one period of the linear drive is 3 times that of the THG). As an example, Fig. 2b shows the respective waveforms of the driving field and the THG at two representative temperatures. The phase of the linear transmission shifts between the two temperatures as a result of the superconducting screening effect21. The phase of THG does not simply follow the phase of the driving field: at 45 K its crest precedes that of the driving field while at 30 K its crest lags behind that of the driving field. The relative phase shift between the two, where the screening-induced phase shift of the driving field has been accounted for, reveals the intrinsic phase evolution of THG (See Supplementary Materials S3 and S4 for a detailed discussion about all contributions to phase shifts at ω and 3ω, which are nearly all accounted for by our analysis). It encodes important spectroscopic information about the superconducting fluctuations, such as their resonance or anti-resonance, across which a phase jump is expected.

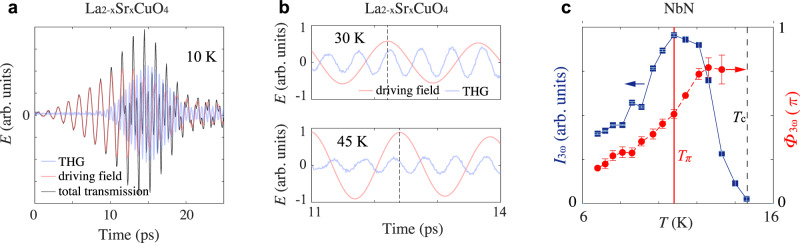

Fig. 2. Third harmonic generation from terahertz-driven superconducting fluctuations.

a Terahertz transmission from an overdoped superconducting La2−xSrxCuO4 thin film as it is pumped by a 0.7 THz driving pulse. The latter drives the 2ω amplitude oscillation of the superconducting order parameter (see Supplementary Materials S5 for a clear experimental visualization of this 2ω oscillation from transient reflectivity measurements). This 2ω collective excitation scatters the driving photon, leading to third harmonic generation (THG) in transmission. The driving field (red) and the THG (blue) waveforms are extracted from the raw transmission data (black) using 1.4 THz Fourier lowpass and highpass filters. b Zoomed-in view of the transmitted driving field and THG from an optimally doped La2−xSrxCuO4 thin film at 30 K and 45 K. The dotted line marks the crest of the driving field, which shifts in time due to the superconducting screening effect. It can be seen that THG does not remain in phase with the driving field at the two temperatures. c THG intensity (I3ω) and phase (Φ3ω, i.e., relative to the linear driving field phase) as a function of temperature from NbN. The peak in I3ω(T) and the continuous evolution of Φ3ω(T) across Tπ indicate the resonance in THG. The error bars on I3ω indicate the noise floors of the FFT power spectra; the error bars on Φ3ω denote the uncertainties in fitting the THG phase and the linear drive phase.

In the conventional s-wave superconductor NbN (Tc ~14 K, 2ΔT=0 ~5 meV), we observe a peak in THG intensity (I3ω) simultaneous with a positive evolution of its phase (Φ3ω) across T = 10.7 K (Fig. 2c), which indicates the resonance of the superconducting fluctuations under a periodic drive. The resonance temperature 10.7 K is roughly expected from the resonance condition 2ω = 2Δ(T), where the driving frequency ω used for this measurement is 0.5 THz (~2 meV) and 2Δ(T) follows a mean field-like temperature dependence. In the (optimally doped) cuprate high-Tc superconductors, we observe a slight positive evolution of Φ3ω at low temperatures (Fig. 3b, see Supplementary Materials S11 for results from the bilayer cuprate DyBa2Cu2O7−x, where the positive phase evolution at low temperature is more apparent). The positive phase evolution, however, is interrupted at some higher temperature (Tπ) by an abrupt jump of nearly π in the negative direction. The phase jump is also accompanied by a dip in I3ω(T). Together, these features identify an anti-resonance, an essential part of Fano interference implying that the periodically driven superconducting fluctuations are coupled to another collective excitation.

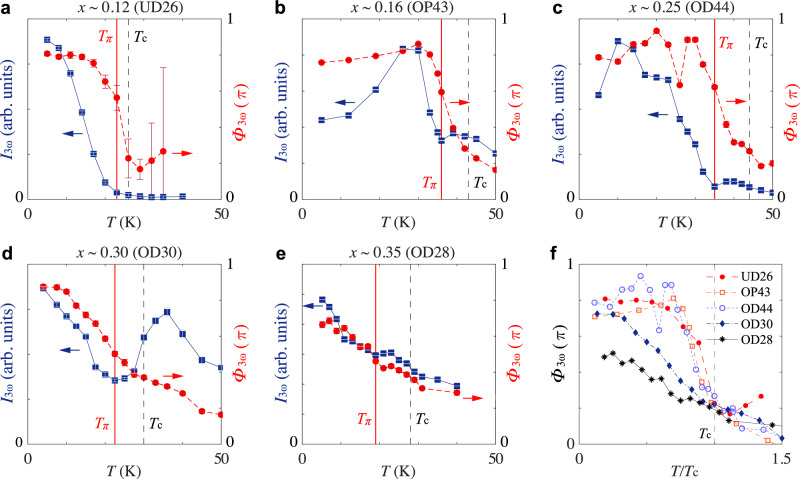

Fig. 3. Doping dependence of Fano interference in La2−xSrxCuO4.

The Fano interference of the driven superconducting fluctuations is identified by the dip in THG intensity (I3ω) concomitant with the negative jump in THG phase (Φ3ω) at the temperature denoted by Tπ (red solid line). The dip-peak feature in I3ω(T) near and above Tπ gives the typical asymmetrical line shape associated with the Fano resonance/interference, compounded by an additional superconducting screening factor9,21. a–e Temperature dependence of I3ω (blue squares) and Φ3ω (red dots) in a x ~0.12 (UD26), b x ~0.16 (OP43), c x ~0.25 (OD44), d x ~0.30 (OD30), e x ~0.35 (OD28). The peak terahertz driving field strength used for these measurements are a ~10 kV/cm, b ~25 kV/cm, c ~25 kV/cm, d ~25 kV/cm, and e ~20 kV/cm. f Temperature dependence of Φ3ω from all five samples plotted on the reduced temperature (T/Tc) scale. The anti-resonance becomes increasingly broadened with hole-doping, indicating a broadening of the coupled mode on the overdoped side.

To investigate the identity of the coupled mode, we look at the hole-doping dependence of the Fano interference first. We measured five La2−xSrxCuO4 thin films grown under similar conditions spanning the underdoped, optimally-doped, and overdoped regimes. As shown in Fig. 3, the salient features of the anti-resonance can be identified at almost all doping levels. In particular, Φ3ω(T) is found to exhibit a more systematic evolution than I3ω(T) across different samples. This is because the temperature-dependent screening effect also causes a superconductor to reflect part of the incoming electromagnetic wave, leading to a variation of the driving field inside the sample as a function of temperature. Since I3ω depends on both the intrinsic THG susceptibility (i.e., arising from the superconducting fluctuations) and the strength of the driving field, its evolution with temperature and hole-doping is not straightforward. In comparison, the relative phase difference Φ3ω is free from the screening effect as explained above, therefore its evolution appears to be much more systematic. Based on the evolution of Φ3ω(T) in all five samples, it is clear that the anti-resonance is sharp in the underdoped and the optimally-doped samples and broadens with further hole-doping, which makes the dip in I3ω(T) more visible on the overdoped side. Within the generalized Fano resonance model, a broadening of the anti-resonance indicates that the coupled mode becomes more heavily damped. Overall, the doping dependence of the Fano interference indicates that the coupled mode is well-defined in the underdoped and up to the optimally doped samples, beyond which it becomes increasingly heavily damped at low temperatures.

In addition to the doping dependence, we also looked at the magnetic field dependence of the Fano interference. We measured the THG response of the x ~0.16 (OP43) and x ~0.30 (OD30) samples under a c-axis magnetic field. As shown in Fig. 4, a broadening of the anti-resonance is manifest in both the amplitude and phase response of THG: the dip feature in I3ω(T) disappears while the sharp jump in Φ3ω(T) widens. Together, these observations suggest that the coupled mode becomes heavily damped or softened upon the application of a magnetic field.

Fig. 4. Magnetic field dependence of Fano interference in La2-xSrxCuO4.

a, c Temperature dependence of I3ω with a magnetic field applied along the c-axis of a x ~0.16 (OP43), c x ~0.30 (OD30). b, d Corresponding temperature dependence of Φ3ω from the two samples. The peak terahertz driving field strength used for these measurements is ~25 kV/cm. The anti-resonance becomes increasingly broadened by the magnetic field, indicating a broadening/softening of the coupled mode with a magnetic field.

Discussion

Below, we offer an interpretation of our results based on a hypothesized interaction between the terahertz-driven superconducting amplitude fluctuations (i.e., Higgs mode) and the CDW fluctuations, which are often found to coexist in the phase diagram of hole-doped cuprates (see Supplementary Materials S7 for a discussion about other possible scenarios for this coupled interaction). Such a hypothesis has also been put forth by previous pump–probe studies focusing on the CDW amplitude fluctuations in underdoped cuprates22, and is corroborated by recent reports of ubiquitous charge order fluctuations in a large part of the cuprate phase diagram overlapping with the superconducting dome and the pseudogap23,24. Note that this interpretation is predicated on assuming THG below Tc predominantly arises from the terahertz-driven Higgs oscillations7,9,11 (see Supplementary Materials S5 and S6 for a discussion about the different origins of THG in a superconductor).

To facilitate the discussion, we quickly summarize the current experimental understanding about the CDW/charge order in hole-doped cuprates: (1) the CDW correlation is strongest in underdoped cuprates and weakens with increasing hole-doping or temperature25 (note that recent studies nonetheless show evidence of CDW in overdoped LSCO and Tl220126,27); (2) at ambient pressure the CDW correlation is generally two-dimensional and short-ranged at all temperatures and its growth upon cooling is pre-empted by the superconducting transition28,29. The second point here implies that any means that enhances the 2D CDW correlation, such as lowering temperature28–31 (i.e., until Tc), applying a uniaxial pressure32 or magnetic field33, will bring the order parameter closer to its critical point and cause its collective excitations to soften.

Having this in mind, we recall that the doping dependence of the Fano interference indicates that the coupled mode is well-defined in the underdoped and optimally doped samples and becomes increasingly heavily damped in the overdoped samples. This is consistent with the doping dependence of the CDW correlation generally expected for cuprates. Second, a magnetic field is expected to suppress superconductivity macroscopically and enhance the CDW correlation33. As the CDW order parameter approaches the critical point, we expect its collective fluctuations to soften, which would also lead to a broadening of the anti-resonance. Here, we emphasize again that although the CDW correlation is strengthened by a magnetic field, its collective fluctuation is expected to soften because at ambient pressure it sits above the putative critical point inside a generic cuprate superconductor28–30. Finally, we note that a recent mean-field investigation of NbSe2 in which superconductivity and CDW coexist and dynamically interact indeed suggests that its THG response manifests a characteristic anti-resonance34,35, similar to our experimental observations above (see also Supplementary Materials S10).

While the interpretation of the Higgs-CDW amplitude mode interaction remains speculative at this stage, we note another interesting finding from the magnetic field dependence study: despite significant changes in I3ω(T) near Tπ (i.e., the suppression of the Fano interference), the overall suppression of THG by the applied field is small up to 10 T in both samples above and below Tc. This can be clearly seen for the OD30 sample in Fig. 3c but is more evident for both samples from the field-sweep measurements performed at constant temperatures (see Supplementary Materials S9). As the THG signal is sensitive to small fluctuations and drifts in the driving power (i.e., I3ω ∝ Iω3) and a complete temperature-sweep measurement as shown in Fig. 3 takes many hours to acquire, the true field dependence of THG is more accurately reflected by the field-sweep results. The lack of field dependence in I3ω away from Tπ suggests that the length scale relevant to the THG process is more likely related to the superconducting coherence length (ξab ~20–30 Å in cuprates) than the London penetration depth (λab ~several hundred nm). The latter is known to increase in the presence of a magnetic field36, which would have led to a decrease in I3ω at any given temperature. The coherence length, on the other hand, is more robust to external fields as it scales with the upper critical field Hc2 as ξab ∝ Hc2−1/2, where Hc2 is on the order of several tens of Teslas in these materials. Adopting such an interpretation would immediately suggest that the above-Tc THG, which is also observed in our studies, may arise from local preformed Cooper pairs. In comparison, in NbN THG drops to zero above Tc, consistent with the absence of preformed Cooper pairs in conventional superconductors.

The above interpretation carries an important implication as in some of our measurements an above-Tc anti-resonance phase jump may also be inferred (Supplementary Materials S11), implying a non-vanishing interaction between preformed Cooper pairs and CDW above Tc. Such an interpretation naturally reminds the intimate relationship between the two orders in the pseudogap region of the cuprate phase diagram. We note that a recent theoretical model, the pair density wave (PDW) model37, predicts a common origin of these two microscopic orders and an interference between Cooper pairs/CDW/PDW already above Tc. To investigate the potential link between the PDW model and our findings, and to unlock the longstanding mysteries of high-Tc superconductors, we anticipate future studies to expand our results to greater details and shed further light on the nature of the Fano interference universally manifested by different families of cuprates.

Methods

Sample preparation

The La2−xSrxCuO4 samples are grown by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) method on LaSrAlO4 substrate. All samples are 40 nm thick. Tc is determined from mutual inductance measurements as shown in Supplementary Materials S2.

Experimental method

The THG experiment is performed using the schematic shown in Supplementary Materials S1. The multicycle terahertz driving pulse is generated from the TELBE super-radiant undulator source at HZDR38. For the data presented in the main text, we use a driving frequency of 0.7 THz and place a 2.1 THz bandpass filter after the sample for filtering the THG response. The transmitted terahertz pulse is measured using electro-optical sampling inside a 2 mm ZnTe crystal and by using 100 fs gating pulses with a central wavelength of 800 nm. The accelerator-based driving pulse and the laser gating pulse have a timing jitter characterized by a standard deviation of ~20 fs. Synchronization is achieved through pulse-resolved detection as detailed in ref. 39.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jingda Wu, Ziliang Ye, Francesco Gabriele, and Lara Benfatto for valuable discussions, and the ELBE team for the operation of the TELBE facility. Parts of this research were carried out at ELBE at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden—Rossendorf e. V., a member of the Helmholtz Association. This research was undertaken thanks in part to funding from the Max Planck-UBC-UTokyo Center for Quantum Materials and the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, Quantum Materials, and Future Technologies Program. This project is also funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC); the Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship (A.D.); the Canada Research Chairs Program (A.D.); the CIFAR Quantum Materials Program; the Double First Class University Plan of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (H.C.); the National Natural Science Foundation of China No. 12274286 (H.C.) and No. 11888101 (N.W.); and the Yangyang Development Fund (H.C.).

Author contributions

H.C. and S.Ka. conceived the project. H.C., S.Ka., S.Ko., and J.-C.D. developed the experimental plan. Measurements on the cuprate samples were performed at the TELBE facility. S.Ko., H.C., L.F., M.-J.K., H.L.P., K.H., R.D.D., M.C., N.A., A.N.P., I.I., M.Z., S.Z., M.N., J.-C.D., and S.Ka. conducted the beamtime experiment. Measurements on NbN were performed by Z.X.W., T.D., and N.W. at Peking University. H.C. performed data analysis and interpreted the results together with M.B., F.B., M.M., D.M., S.Ka., and B.K. L.S., R.H., M.P., and D.M. performed theoretical modeling. G.K., D.P., G.C., and G.L. provided and characterized the cuprate samples. H.C. wrote the paper with S.Ka., D.M., A.D., L.S., and M.P. with inputs from all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the online repository 10.14278/rodare.1692.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hao Chu, Sergey Kovalev.

Contributor Information

Hao Chu, Email: haochusjtu@sjtu.edu.cn.

Stefan Kaiser, Email: s.kaiser@fkf.mpg.de.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-36787-4.

References

- 1.Bogdanov PV, et al. Evidence for an energy scale for quasiparticle dispersion in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;85:2581. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanzara A, et al. Evidence for ubiquitous electron-phonon coupling in high-Tc superconductor. Nature. 2001;412:510. doi: 10.1038/35087518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eschrig M. The effect of collective spin-1 excitations on electronic spectra in high-Tc superconductors. Adv. Phys. 2006;55:47–183. doi: 10.1080/00018730600645636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limonov MF, Rybin MV, Poddubny AN, Kivshar YS. Fano resonances in photonics. Nat. Photon. 2017;11:543–554. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2017.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luk’yanchuk B, et al. The Fano resonance in plasmonic nanostructures and metamaterials. Nat. Mat. 2010;9:707–715. doi: 10.1038/nmat2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S-C, et al. Doping-dependent nonlinear Meissner effect and spontaneous currents in high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2005;71:014507. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.71.014507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsunaga R, et al. Light-induced collective pseudospin precession resonating with Higgs mode in a superconductor. Science. 2014;345:1145–1149. doi: 10.1126/science.1254697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajasekaran S, et al. Probing optically silent superfluid stripes in cuprates. Science. 2018;359:575–579. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu H, et al. Phase-resolved Higgs response in superconducting cuprates. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1793. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cea T, Castellani C, Benfatto L. Nonlinear optical effects and third-harmonic generation in superconductors: Cooper pairs versus Higgs mode contribution. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;93:180507. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.180507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuji N, Nomura Y. Higgs-mode resonance in third harmonic generation in NbN superconductors: multiband electron-phonon coupling, impurity scattering, and polarization-angle dependence. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020;2:043029. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.043029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seibold G, Udina M, Castellani C, Benfatto L. Third harmonic generation from collective modes in disordered superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;103:014512. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.103.014512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriele F, Udina M, Benfatto L. Non-linear terahertz driving of plasma waves in layered cuprates. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:752. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson PW. Plasmons, gauge invariance, and mass. Phys. Rev. 1963;130:439–442. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.130.439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgs PW. Broken symmetries and the masses of gauge bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964;13:508–509. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pekker D, Varma C. Amplitude/Higgs modes in condensed matter physics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2015;6:269–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031214-014350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volkov AF, Kogan SM. Collisionless relaxation of the energy gap in superconductors. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 1973;65:2038. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsunaga R, et al. Higgs amplitude mode in the BCS superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;111:057002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.057002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reber TJ, et al. Prepairing and the “filling” gap in the cuprates from the tomographic density of states. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;87:060506. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.87.060506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo T, et al. Point nodes persisting far beyond Tc in Bi2212. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7699. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dressel M. Electrodynamics of metallic superconductors. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys. 2013;2013:104379. doi: 10.1155/2013/104379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinton JP, et al. New collective mode in YBa2Cu3O6+x observed by time-domain reflectometry. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;88:060508. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.060508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arpaia R, Ghiringhelli G. Charge order at high temperature in cuprate superconductors. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021;90:111005. doi: 10.7566/JPSJ.90.111005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boschini F, et al. Dynamic electron correlations with charge order wavelength along all directions in the copper oxide plane. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:597. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20824-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keimer B, Kivelson SA, Norman MR, Uchida S, Zaanen J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature. 2015;518:179–186. doi: 10.1038/nature14165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miao H, et al. Charge density waves in cuprate superconductors beyond the critical doping. npj Quantum Mater. 2021;6:31. doi: 10.1038/s41535-021-00327-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tam CC, et al. Charge density waves and Fermi surface reconstruction in the clean overdoped cuprate superconductor Tl2Ba2CuO6+δ. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:570. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28124-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghiringhelli G, et al. Long-range incommensurate charge fluctuations in (Y,Nd)BaCuO6+x. Science. 2012;337:821–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1223532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang J, et al. Direct observation of competition between SC and CDW order in YBa2Cu3O6.67. Nat. Phys. 2012;8:871. doi: 10.1038/nphys2456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tacon ML, et al. Inelastic X-ray scattering in YBa2Cu3O6.6 reveals giant phonon anomalies and elastic central peak due to charge-density-wave formation. Nat. Phys. 2014;10:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nphys2805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu H, et al. A charge density wave-like instability in a doped spin–orbit-assisted weak Mott insulator. Nat. Mat. 2017;16:200–203. doi: 10.1038/nmat4836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim H-H, et al. Uniaxial pressure control of competing orders in a high-temperature superconductor. Science. 2018;362:1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerber S, et al. Three-dimensional charge density wave order in YBa2Cu3O6.67 at high magnetic fields. Science. 2015;350:949–952. doi: 10.1126/science.aac6257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cea T, Benfatto L. Nature and Raman signatures of the Higgs amplitude mode in the coexisting superconducting and charge-density-wave state. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;90:224515. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.224515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwarz L, Haenel R, Manske D. Phase signatures in the third-harmonic response of Higgs and coexisting modes in superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;104:174508. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.104.174508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schafgans AA, et al. Towards a two-dimensional superconducting state of La2-xSrxCuO4 in a moderate external magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;104:157002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.157002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agterberg DF, et al. The physics of pair-density waves: cuprate superconductors and beyond. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2020;11:231–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031119-050711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green B, et al. High-field high-repetition-rate sources for the coherent THz control of matter. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22256. doi: 10.1038/srep22256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovalev S, et al. Probing ultra-fast processes with high dynamic range at 4th-generation light sources: arrival time and intensity binning at unprecedented repetition rates. Struct. Dyn. 2017;4:024301. doi: 10.1063/1.4978042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the online repository 10.14278/rodare.1692.