Summary

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to impact mental health and wellbeing globally. There is a lack of scientific documentation highlighting the mental health impact of COVID-19 in Bhutan. We present the mental health burdens and control measures taken, and suggest ways to further strengthen mental health services in Bhutan. During the pandemic, a rise in depression and anxiety had been reported in Bhutan. Depression rose from an average prevalence of 9 per 10,000 between 2011 and 2019 to 16 per 10,000 in 2020 and 32 per 10,000 in 2021. Similarly, anxiety rose from an average prevalence of 18 per 10,000, to 29 per 10,000 in 2020, and 55 per 10,000 in 2021. Psychological impacts related to isolation due to lockdowns, economic losses, and poor coping abilities were associated with negative outcomes. Stigma and discrimination towards mental health disorders discouraged mentally distressed people from seeking care. In response to increased demand, Bhutan's government initiated a range of interventions including home delivery of medicines and tele-counselling to people in need of urgent mental health care. Mental health care in Bhutan can be further improved through investment in services and human resources, and decentralization of services to the community.

Keywords: COVID-19, Bhutan, Wellbeing, Mental health, Control, Gross national happiness

Introduction

Nestled in the Eastern Himalayas, Bhutan is a tiny kingdom located in South Asia with an area of 38,394 square kilometres and an estimated population of approximately 780,000 distributed in 20 districts in 2021.1 The ratio of male to female population was reported at 113.7:100 in 2021 and an overall life expectancy of 72 years in 2020.1,2 Guided by the developmental philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH), the right to free access to essential health services is mandated by the constitution and the expenditure for healthcare services including referrals to a third country is borne by the government.3 GNH is based on the conceptual framework of four pillars, namely, sustainable and equitable socio-economic development, environmental conservation, preservation and promotion of culture, and good governance. These pillars are further expanded to nine domains: psychological well-being, health, time use, education, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and living standards.4 The domains represent the component of the well-being of the Bhutanese population as per the values and principles of GNH.

A comprehensive mental health plan was developed for the first time in Bhutan with the establishment of the National Mental Health Program in 1997.5 Mental healthcare is integrated with the primary healthcare system to provide essential mental care to the patients and health promotion activities in the communities.6 The primary care physician and healthcare professionals (i.e., Health Assistants) working in primary healthcare are trained to provide counselling, follow-up treatment and refilling of psychiatric medicines. While community-based psychiatric units are functional along with general health services in all 20 districts, none of these facilities have a qualified and trained healthcare provider except the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH) in the capital, Thimphu. The JDWNRH has a 20-bed psychiatric ward managed by two psychiatrists and one psychiatric nurse. In addition to hospital or health centre-based mental health services, there are also trained counsellors in the schools, colleges and social service organizations who coordinate with the National Mental Health Program to manage mental illness in their settings. There are no private mental healthcare facilities currently available in the country.

Bhutan reported its first case of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in March 2020 in a 76-year old tourist, who contracted the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in India.7 In a span of 31 months, 62,577 cases and 21 deaths of COVID-19 were reported across the country.8 COVID-19 cases among males were proportionately higher than in females (male vs female: 55% vs 45%).9 Mortality in females and males was similar (male vs female: 10 deaths vs 11 deaths) and associated with pre-existing co-morbidities, predominantly related to chronic kidney disease. This pattern is similar to a global scenario, where the hospitalizations and deaths due to COVID-19 were mostly related to patients with comorbidities, such as diabetes, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver disease and chronic kidney disease.10,11

During the initial phase of the pandemic, Bhutan instituted drastic control measures to limit the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 including movement restrictions from high-risk (international border districts in Southern Bhutan) to low-risk zones, physical distancing, mandatory Druk-trace scanning before entering public places such as vegetable markets, wearing masks, hand-hygiene and nationwide lockdowns. All returning travellers were required to undergo a mandatory 21-day quarantine.7 Druk-trace is a software program developed by the Bhutan government to trace community contacts of COVID-19 anonymously.12

The ongoing pandemic has put a significant strain on the economy and healthcare systems around the world. In particular, the COVID-19 restrictions to contain the disease were associated with debilitating psychological effects, which surged during the pandemic.13 A systematic review of 24 studies that included participants from quarantine facilities reported a high prevalence of stress, depression, irritability, emotional disturbances and anxiety-induced insomnia.14 Another systematic review and meta-analysis involving 68 cross-sectional studies demonstrated that one in three adults in the general population was affected by COVID-19-related psychological distress including anxiety and depression.15 The key risk factors for psychological distress were lower socio-economic status (related to lower income, education and unemployment), residing in rural areas, those with or at higher risk of COVID-19 infection (living in hard-hit areas and those with co-morbidities), and loneliness due to physical distancing.15,16 In children and adolescents, financial hardships, not being optimistic and fear of being infected with COVID-19 were more commonly linked to mental illness.17,18 In healthcare workers, mental illness was linked to work overload, care for critical or complex patients, exposure to biological risk, lack of physical activity and deprivation of private and family life to prevent the spread of the infection.19

COVID-19 and its restrictions are likely to increase mental disorders in the South Asia region.20 However, there are limited studies on the effect of COVID-19 on mental health in Bhutan, where GNH is a focus.21 The COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions to contain the disease were associated with psychological effects, which surged during the pandemic.22 To cope with the mental health impact of COVID-19 in Bhutan, with the support of strong leadership, a number of mitigating measures and support were initiated by the government. Herein, we present a report on the mental health impact of COVID-19, and the control measures undertaken to mitigate the rapidly growing problem of poor mental health, with a focus on challenges and ways forward. In addition to informing local mental health policies for strengthening mental health services during the pandemic and beyond in Bhutan, the experience and strategy of Bhutan's response to mental health impact of COVID-19 can provide a critical lesson for other neighbouring nations.

A rise in the mental health problem

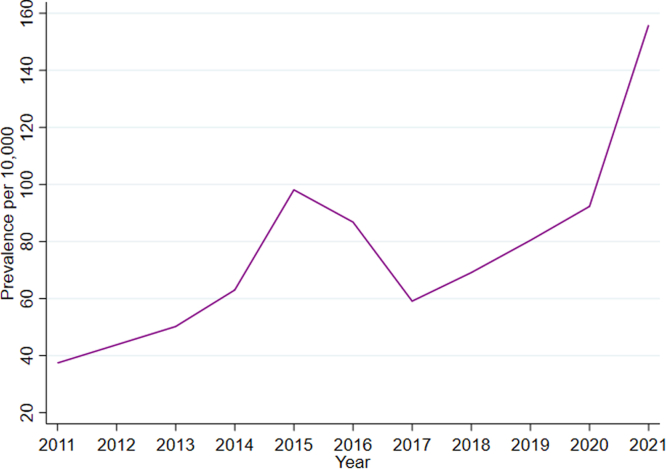

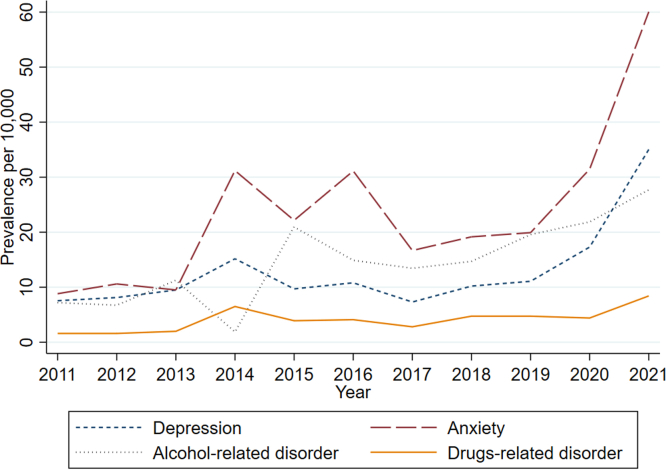

COVID-19 and restrictions imposed by the government have disrupted normal life, leading to heightened mental health problems in Bhutan. As per the Annual Health Bulletin published annually by the Ministry of Health, mental health disorders increased from 87 per 10,000 in 2016 to 156 per 10,000 population in 2021 (Fig. 1).23 In particular, the prevalence of depression and anxiety showed an upward trend during the pandemic that was not seen at any time previously (Fig. 2 and Supplementary file S2 Tables S1–S5). Depression rose from an average prevalence of 9 per 10,000 between 2011 and 2019 to 16 per 10,000 in 2020 and 32 per 10,000 in 2021. Similarly, anxiety rose from an average prevalence of 18 per 10,000 between 2011 and 2019 to 29 per 10,000 in 2020 and 55 per 10,000 in 2021. As compared to 2011, patients with depression were more than twice as likely to have occurred in 2020 (rate ratio [RR]: 2.11, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.91, 2.34), and more than four times as likely to have occurred in 2021 (RR: 4.24, 95% CI: 3.86, 4.66). Prior to the pandemic, the rate ratios for depression were all <2. A rapid survey conducted by UNICEF in partnership with the Department of Youth and Sports under the Ministry of Education among adolescents aged 10–24 years in September 2021 found that as many as 30% were sad and stressed, and 7% were depressed.24 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global prevalence of anxiety and depression have surged by a massive 25%.25 An increase in these mental disorders is most likely related to stress due to social isolation associated with decreased human mobility as reported in the systematic review.26 These restrictions during the pandemic have put a considerable constraint on people's ability to work, seek support and engage with communities. Nonetheless, in Bhutan, the frequencies of mental disorders associated with multiple drug-use and other psychoactive substances before and during the pandemic presented a similar pattern (Fig. 2). Globally, the pattern of substance use varied across different countries, for example, the proportion of substance use had increased in the United States, while Canada reported a decreasing trend during the pandemic.27

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of the combined/overall mental health disorders in Bhutan between 2011 and 2021. Depression, anxiety and other mental disorders, such as dementia, alcohol and psychoactive substance-related mental and behaviour disorders were combined together to generate an overall mental health disorders.

Source: Annual Health Bulletin, 2012–2022, Ministry of Health.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of commonly reported mental health disorders in Bhutan between 2011 and 2021.

Source: Annual Health Bulletin, Ministry of Health.

The pandemic also saw an apparent increase in the number of deaths due to suicides, particularly in the remote areas of Bhutan.28 The annual number of deaths by suicides between 2017 and 2019 stands at 12 per 100,000 populations. However, the incidence in 2020 rose to 12.7 per 100,000 populations (Supplementary file S2 Table S6).23 Suicides in countries of the South East Asia are more commonly reported in rural compared to urban areas.29 People living in remote areas tend to have poor literacy, are financially disadvantaged and lack jobs making them more vulnerable to mental disorders and suicide.30,31 COVID-19 pandemic has further aggravated mental health problems through lockdowns, financial hardships and lack of access to basic amenities such as educational resources.32 However, there is a lack of comprehensive research on suicide in Bhutan, aforementioned reasons for suicide in the region could be applicable due to some similarities in culture and social fabric.33

Domestic violence and violence against women and girls were also more frequently reported in Bhutan. During the first three months of COVID-19 restrictions, 22 cases of sexual assaults were reported to the UNFPA-supported One-Stop Crisis Centre, housed in JDWNRH.28 Since then cases related to sexual assaults were reported on average every four days.28 Pema, a counsellor volunteer at the UNFPA, has been vocal regarding the urgent need to provide mental and psychosocial support to victims of sexual violence, stating “This lockdown has brought the whole country to a standstill, but domestic violence and violence against women and girls have proliferated. I had to continuously respond and provide tele-counselling services to the victims of domestic and sexual violence since the lockdown. Today, my client has called me over seven times, and I am a bit worried”.34 Over 200 such services were provided in the first month of the COVID-19 restrictions in the country.34 The National Commission for Women and Children (NCWC) conducted an in-depth assessment of the domestic violence during the pandemic.35 Gender-based violence among adults was reported at 6% in adults and 5% in children, mostly related to emotional and physical violence.35 Similar increases in domestic violence were also reported in other countries: in Jordan, the prevalence of domestic violence was 20.5%,36 while in Ethiopia, 24.1% women experienced violence in the last 12 months of the pandemic.37 Anecdotal evidence indicates that abusers are leveraging their power of stay-at-home mandates or using fear-based tactics to exaggerate the risk of virus contraction leading the victims to further isolation and dependency on the abusive partner.38 In Bhutan, alcohol use within the confines of their homes might have contributed to an increase in domestic and sexual violence during the pandemic. Alcohol is an intrinsic part of Bhutanese culture and one of the highest in the South-East Asia Region.39

Mental health disorders are subjected to high levels of social stigma and discrimination in Bhutan.40 The attitude that mental illness is caused by black magic, evil spirits, witchcraft, a curse or bad deeds from past lives (i.e., karma) contributes to the social stigma. Social stigma drives sufferers to alternative healing practices like religious/faith healing and psychiatric consultation is often the last option of treatment.6,41 Often mentally ill people are unjustly treated due to social stigma and stereotype, which lowers their self-esteem pushing them to use alcohol and drugs as a coping mechanism.6,42 People with mental illness are unfairly branded as a “mad person” or “psycho”.40 People with such disabilities are often subjected to missed opportunities through less opportunities for jobs and other services.43 The Mental Health Program has been highly critical of the challenges associated with social stigma on mental health care stating “the stigma associated with mental disorders hinders the service-availing behaviours of people but this is improving with increasing number of people gradually seeking the services”. Improving public awareness and knowledge of mental health is key to addressing the aforementioned issues.28

The COVID-19 pandemic has also exacerbated the psychological distress of frontline healthcare workers in Bhutan. A survey involving 133 nurses providing care for COVID-19 patients found 40.6% and 30.8% had moderate and high mental health impacts due to fear of COVID-19 infection and high workload.22 This finding is similar to an umbrella review of seven meta-analyses that reported an increased prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the pandemic.44 Elevated stress among healthcare workers in other countries was contributed by numerous factors, including fear of contracting COVID-19, heavy workload and long working hours, multi-tasking, and short-notice assignment to new working environments without prior experience.45

Mitigating strategies

Bhutan initiated several measures to address the rising mental health problem associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The first and foremost is due to the strong leadership of Their Majesties, the Fourth King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck and the Fifth King, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. Throughout the pandemic, Their Majesties ensured the safety of every citizen, even endangering their own life by trekking across diverse geographical terrain from high mountains to southern borders and meeting the frontline workers and people.

A welfare scheme “Druk Gyalpo's Relief Kidu” was launched upon the Royal Command of His Majesty the King.46 This scheme provided income to people who lost their livelihood due to the pandemic. A total of 54,783 affected individuals received income support between April 2020 and March 2022 from the relief fund.47 Without such critical social assistance, the number of mental health problems including depression and anxiety might have potentially flared up due to economic hardship.

The Prime Minister, the Health Minister and the Foreign Minister were involved in the successful implementation of the COVID-19 National and Regional Task Force committees responsible for planning and implementing all COVID-19 related initiatives.7 A National COVID-19 Mental Health and Psychological Response Team was instituted under the Royal Command to provide psychological support to those affected by COVID-19. The team adapted WHO Psychological First Aid+ (PFA+) guide and trained more than 20,000 frontline workers including health workers, counsellors and community volunteers to identify risk factors for suicide and provide basic psychosocial support to people in distress and identify cases that need referrals. In addition, 140 first responders including medical doctors, mental health workers and clinical counsellors were trained to manage self-harm and suicides.48 The response team also developed “Media guidelines for responsible reporting of mental health and suicide” and disseminated to all media representatives.

An emergency measure was implemented to ensure uninterrupted delivery of essential healthcare services during the nationwide lockdowns.49 The essential healthcare services prioritized patients with mental health problems, dental procedures, non-communicable diseases, HIV, tuberculosis, maternal and child health services including immunization, antenatal care, institutional deliveries and postnatal care.50 These services were provided to individual residences via mobile clinic and telehealth, including videoconferences and teleconferences. Dedicated hotline numbers and online social media helplines at both the national and community levels were set up to provide telemedicine for mental health problems even to far-flung areas which otherwise were not accessible. Services included counselling, screening and even referral to seek advanced mental care. As a result, in-person consultations in hospitals was reduced thus preventing the transmission of COVID-19.49 Such technology-enabled interventions have been demonstrated to be as effective as in-person consultation for mental health services in other countries.51 Therefore, such services should be continued to the far-flung communities in Bhutan and other countries can pilot such services.

The Ministry of Education and UNICEF jointly launched the “OnMyMind” campaign in October 2021 to increase awareness of mental health and strengthen the support-seeking behaviour of youths and adolescents. The campaign allowed children and parents/caregivers to share their experiences at home, in schools or in the community with the aim to encourage others to start talking about their mental health. The overall goal of the campaign was to end abuse and child adversities that drive poor mental health outcomes.52 Future studies are needed to understand and evaluate the impact of such campaign.

In November 2021, Her Majesty The Gyaltsuen (The Queen) Jetsun Pema Wangchuck graced the construction of a hospital for mental health and well-being, named The Pema Centre. The goal of the centre is that mental health will receive a higher national priority and lead a coordinated and holistic approach to strengthen and harmonize all mental health related interventions across the country. The centre also envisages extending services to families and friends of individuals with mental health challenges to help them better understand the distress that their loved ones are going through.53

Medications for chronic mental illness were distributed by hospital pharmacies, to zones established for COVID-19 control, from where the medicines were delivered to patients.54 The zoning system was implemented in urban centres with higher risks for COVID-19 to limit the movement of people for collecting essential commodities like food and medicines during the lockdowns.55

The national tobacco ban was temporarily lifted in July 2020, and in June 2021 the National Assembly of Bhutan passed a resolution to lift the ban owing to the increasingly lucrative clandestine black market for tobacco and the increasing number of smugglers crossing the border from India.56 Although this ad hoc decision from the government was not free from public backlash and criticism, in particular from the conservative members of the society and medical professionals due to its harmful effects, there was a certain value in this approach in curbing the risk of importation of COVID-19 infection and the inherent benefit to the tobacco user in preventing adverse effects following the sudden withdrawal of tobacco.57 Otherwise, the number of tobacco smugglers illegally crossing the international border were pervasive and damaging the country's lockdown protocols.58 Closure of alcohol sales outlets in Kerala, India, led to withdrawal symptoms and suicides in alcoholics, killing more people than COVID-19 in the first 2–3 months of the pandemic.59 Bhutan avoided such a catastrophe by taking proactive initiative at the very beginning of the pandemic by taking orders and distributing alcohol and tobacco to the hands of the consumers.60

Challenges

Notwithstanding these initiatives and supports for the mental health problem in Bhutan, there were a number of challenges. Firstly, the noble initiative of counselling service provided via hotlines were interrupted by some fake and unrelated calls. This might be related to the confusion or lack of clarity in the dissemination of information to the general population in regards to the types of services. Such untoward events hampered tele-counselling services.61 This highlights the need to strengthen awareness and understanding of telehealth services to avoid unrelated calls and maximise the benefit of such services. Secondly, there were inadequate and variable mental health services across the country. Most of the services and resources were located in the capital city Thimphu and urban areas, efforts were made to institute outreach services. Other challenges included a lack of adequate clinical counsellors, designated units and spaces for mental health (to provide privacy) in the regional and district hospitals. This might be due to the limited budget for mental health at the national planning level - only 1% of the health budget was allocated to mental health programs and the amount remained constant over the years despite the increase in mental health needs.28

Thirdly, there was under-reporting because many patients did not seek care in hospitals due to perceived stigma and discrimination.40 Despite advocacies and awareness campaigns on mental health, limited assessment on the effectiveness of these health education has been undertaken till date. These include the uptake of health education messages, inclusiveness of vulnerable sub-populations including visually impaired and deaf individuals, and differently abled individuals. In addition, the health messaging also need to consider other major languages including Tshangla and Lhotsham kha to reach out to a wider population.

Finally, despite the development of national mental health policy since 1997,5 Bhutan still does not have separate legislation for mental health to safeguard and protect the rights and treatment of people with mental disorders. The Ministry of Health needs to initiate this legislation and seek support from the legislature to improve mental health services in the country.

Way forward

Telehealth

The government's initiative to implement telemedicine for mental health should be strengthened to cover all 20 districts. Telehealth can be used to manage patients clinically (patient consultations), and for non-clinical purpose, such as, meetings, educational sessions and case conferencing.62 Reliable network coverage and affordable services should be supported so that telehealth uptake will increase. In addition, outreach services may be used as an adjunct to telehealth in places without adequate network coverage. Outreach health services in the country are organized by healthcare providers and involve travelling to remote villages to increase immunization and maternal and child health coverage, as well as providing essential care to elderly patients.

Mental health triage and care

Healthcare providers at the primary healthcare centres and hospitals should be trained on mental health triage to identify people at risk, provide psychological support on the spot and arrange referral to consult psychiatrist at the national referral hospital in Thimphu. As the pandemic continues with new strains such as Omicron sub-lineages, and as a long-term measure, it is of paramount importance to have trained and skilled workers to manage mental health problems in primary healthcare centres across the country.

Health equity

Mental health problems including suicides are higher in the rural areas possibly due to lack of adequate health education and delayed medical care from specialty hospital. This happens due to inadequate infrastructures such as poor internet and road connectivity in rural areas. Moreover, health services in rural areas are predominantly provided by primary health centres that focus on health promotion and primary care. In light of these disadvantages to the rural people, strengthening primary health centres through training, and setting telemedicine could potentially improve the care of patients with mental and other illnesses.

Stigma and discrimination

Strategies to reduce and stop stigma and discrimination against mental illness should be strengthened, in particular, with the involvement of communities and monastic organizations, and health promotion activities. Educating the public to develop a positive attitude towards people with mental illness should be started in earnest.63 Mental health literacy is one of the key pillars to influence health-seeking behaviour and the human rights of people with mental problems. Therefore, advocacy and education against stigma and discrimination should be done using both formal and non-formal communication channels. Non-formal approaches might include setting up awareness stalls where people congregate in large numbers-such as Tshechu (local festival) and national day celebrations. Currently used social media and platforms including the national television channel (BBSTV), radio (BBS), and newspapers (Kuensel), Facebook pages of the Ministry of Health, Prime Minister's Office, and Adolescent Friendly Health Service Bhutan should be strengthened. Finally, this education should be done in other commonly used languages (Tsangla and Lhotshampa kha) besides Dzongkha and English.

Research

In order to address limited research on mental health in Bhutan, mental health programs and related stakeholders need to create a paradigm-changing platform to facilitate collaborative and partnership research to identify risk factors of mental health and the impact of public interventions on it. Targeting at-risk populations will lead to the effective utilization of limited public health resources rather than providing a blanket or poorly targeted interventions without evidence. Evidenced-based healthcare practices are the best way to tackle public health problem. Policies and guidelines developed based on evidence gain trust and confidence needed for its compliance and better outcomes.64

Data quality and reporting

To strengthen mental illness data, healthcare providers need to be trained in identifying cases of mental disorders, recording and reporting it to the Health Management Information System. Regular monitoring and evaluation of mental health data should commence and strengthened. Good quality data are essential to develop evidence-based policies to mitigate mental health problems.

Human and resource constraints

The concentration of the mental health workforce in Thimphu (capital city) is a major impediment to the efficient delivery of effective mental health services. Although essential mental health services such as counselling, follow-treatment and refilling of medicines are integrated with primary healthcare in all 20 districts in Bhutan, diagnosis and treatment with psychiatric medications are done only in JDWNRH. Strategies to strengthen regional uniformity of services, as enshrined in GNH, should be undertaken in earnest. The program noted the gaps in the treatment of mental health disorders due to inadequate human resources and mental health professionals and felt the urgent need to recruit adequate number of qualified mental health professionals. With the recent establishment of a course on Clinical Counselling in the Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan, trained clinical counsellors will be recruited soon across health centres in the country. This will support the existing pool of school counsellors, social workers and nurse counsellors in mental health care in Bhutan. In addition, posting psychiatrists or clinical psychologists at regional hospitals can improve advanced psychological care and management of patients with complex mental health problems. Further, this can save time and costs of travel to patients and patient load in the JDWNRH could be reduced.

GNH and mental health

All national developmental policies and plans in Bhutan are guided by the GNH philosophy which has positively impacted mental health of its population when the country was threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, GNH domains including health, psychological well-being, good governance and community vitality on mental health were visible.65 The happiness and wellness centres were established in 2019 across all colleges under the Royal University of Bhutan.66 The aim of such centres were to provide mental care including counselling and mindfulness to student, staffs, the local community, government agencies and non-governmental organizations. Therefore, capacity building of these centres with the counsellors in the schools and social service organizations with adequate training on psychosocial support can go a long way in improving the mental health and well-being of the people in Bhutan. As majority of the Bhutanese seek spiritual or religious help for both physical and mental health problems, engaging religious organizations will be instrumental to promote psychological well-being through supportive faith-based community networks and by providing individuals a sense of realizing their purpose in life and belonging to the community. Studies have shown better ability to cope with stress, anxiety, depression and addictions among those with religious involvement.67

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised the visibility and relevance of mental health and the need to strengthen services for mental health in Bhutan. During the pandemic, the government has initiated a number of mental health programs in partnership with donors and relevant stakeholders. This included strong leadership to gain public solidarity, use of telemedicine and teleconsultation to provide mental care, health promotion campaigns to encourage people to seek mental care, uninterrupted care and home-delivery of psychoactive medicines to chronic mental illness, and social assistance for financial security. However, there are still several areas that can be strengthened to further improve mental health in Bhutan. This includes, improving telehealth, decentralization of mental health services, standardization of services across the country, and building a national agenda to prevent stigmatization and discrimination against sufferers of mental illness.

Contributors

TT and KW conceived this study. TT undertook literature review and drafted the manuscript. KW helped in the drafting and revision of manuscript. DC, ND, HPP, DJG and ACAC were involved in the critical revision of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

Funding: This study did not receive any external funding. KW is funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council 2021 Investigator Grant (2008697).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100179.

Contributor Information

Tsheten Tsheten, Email: tsheten.tsheten@anu.edu.au.

Dan Chateau, Email: Dan.Chateau@anu.edu.au.

Nima Dorji, Email: dorji_405@yahoo.com.

Hari Prasad Pokhrel, Email: hppokhrel@health.gov.bt.

Archie C.A. Clements, Email: archie.clements@plymouth.ac.uk.

Darren J. Gray, Email: darren.gray@anu.edu.au.

Kinley Wangdi, Email: kinley.wangdi@anu.edu.au.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.StatisticsTimes.com . 2021. Demographics of Bhutan.https://statisticstimes.com/demographics/country/bhutan-demographics.php Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/country/bhutan?view=chart Available online:

- 3.Royal Government of Bhutan . 2008. The constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masaki K., Tshering J. Exploring the origins of Bhutan's Gross national happiness. J South Asian Dev. 2021;16:273–292. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization WHO-AIMS report on mental health system in Bhutan. 2007. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206150 Available online:

- 6.Pelzang R. Mental health care in Bhutan: policy and issues. WHO South-East Asia. J Public Health. 2012;1:339–346. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.207030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsheten T., Wangchuk S., Wangmo D., Clements A.C.A., Gray D.J., Wangdi K. COVID-19 response and lessons learned on dengue control in Bhutan. J Med Entomol. 2021;58:502–504. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjaa225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . 2023. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/data Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health . 2023. National situational update on COVID-19.https://www.moh.gov.bt/national-situational-update-on-covid-19-429/ Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vardavas C.I., Mathioudakis A.G., Nikitara K., et al. Prognostic factors for mortality, intensive care unit and hospital admission due to SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies in Europe. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31 doi: 10.1183/16000617.0098-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AbuRuz S., Al-Azayzih A., ZainAlAbdin S., Beiram R., Al Hajjar M. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality among COVID-19 hospitalized patients in UAE: does ethnic origin have an impact. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorji T., Wangmo K., Yezer, Wangchuk T., Tshokey, Wangdi K. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward COVID-19 among Sherubtse college students in Bhutan: a web-based cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.721493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loiwal M. India Today; 2020. 20% increase in patients with mental illness since coronavirus outbreak: survey.https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/20-per-cent-increase-in-patients-with-mental-illness-since-coronavirus-outbreak-survey-1661584-2020-03-31 Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., Kala M.P., Jafar T.H. Factors associated with psychological distress during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the predominantly general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seifert A., Hassler B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness among older adults. Front Sociol. 2020;5 doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.590935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golberstein E., Wen H., Miller B.F. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:819–820. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie X., Xue Q., Zhou Y., et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:898–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bassi M., Negri L., Delle Fave A., Accardi R. The relationship between post-traumatic stress and positive mental health symptoms among health workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Lombardy, Italy. J Affect Disord. 2021;280:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hossain M.M., Rahman M., Trisha N.F., et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in South Asia during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tshering K., Dema K. Psychological impact during COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based cross-sectional study among students studying at College of Science and Technology (CST), Phuentsholing, Bhutan. PLoS One. 2022;17(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gyaltshen K., Hengudomsub P., Wacharasin C. vol. 29. J Faculty Nurs Burapha University; 2021. pp. 102–114. (Psychological impact and its affecting factors among nurses working in COVID-19 designated hospitals in Bhutan). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health, Royal Government of Bhutan . Health Management Information System and Research Section, Policy and Planning Division, Ministry of Health; 2021. Annual health bulletin. Thimphu. [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNICEF. Bhutan Case Study . 2021. Situation analysis on the effects of and responses to COVID-19 on the education sector in Asia.https://www.unicef.org/rosa/documents/bhutan-case-study Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide Available online:

- 26.Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts A., Rogers J., Mason R., et al. Alcohol and other substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;229(Pt A) doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tshedup Y. Kuensel; 2021. Suicide cases on the rise.https://kuenselonline.com/suicide-cases-on-the-rise/ Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vijayakumar L., Daly C., Arafat Y., Arensman E. Suicide prevention in the Southeast Asia region. Crisis. 2020;41:S21–S29. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rehkopf D.H., Buka S.L. The association between suicide and the socio-economic characteristics of geographical areas: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006;36:145–157. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500588X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferretti F., Coluccia A. Socio-economic factors and suicide rates in European Union countries. Leg Med. 2009;11:S92–S94. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farooq S., Tunmore J., Wajid Ali M., Ayub M. Suicide, self-harm and suicidal ideation during COVID-19: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2021;306 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dendup T., Zhao Y., Dorji T., Phuntsho S. Risk factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in Bhutan: an analysis of the 2014 Bhutan STEPS Survey data. PLoS One. 2020;15(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.United Nations Populatio Fund . 2020. Pandemic and rising tide of violence increase demand for mental health.https://www.unfpa.org/news/pandemic-and-rising-tide-violence-increase-demand-mental-health-psychosocial-care psychosocial care [press release] Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Commision for Women and Children, Royal Government of Bhutan . 2021. Covid-19 impact on women and children (Bhutan) Thimphu. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aolymat I. A cross-sectional study of the impact of COVID-19 on domestic violence, menstruation, genital tract health, and contraception use among women in Jordan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104:519–525. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shitu S., Yeshaneh A., Abebe H. Intimate partner violence and associated factors among reproductive age women during COVID-19 pandemic in Southern Ethiopia, 2020. Reprod Health. 2021;18:246. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01297-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Usher K., Bhullar N., Durkin J., Gyamfi N., Jackson D. Family violence and COVID-19: increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29:549–552. doi: 10.1111/inm.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wangdi K., Jamtsho T. Prevalence and correlates of current alcohol use among Bhutanese adults: a nationally representative survey data analysis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41:38–45. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_412_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, Bhutan . 2021. Let's not stigmatise mental health.https://www.unicef.org/bhutan/stories/lets-not-stigmatise-mental-health Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zam N. The Diplomat; 2018. Bhutan: the mental state of the happy kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dema C. 2021. Incident of stigma, discrimination, bullying and violence, business Bhutan.https://businessbhutan.bt/the-untold-stories-of-key-populations-social-stigma-discrimination-and-its-consequences/ Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Psychiatric A . 2019. Stigma, prejudice and discrimination against people with mental illness.https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/stigma-and-discrimination Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahebi A., Nejati-Zarnaqi B., Moayedi S., Yousefi K., Torres M., Golitaleb M. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mokhtari R., Moayedi S., Golitaleb M. COVID-19 pandemic and health anxiety among nurses of intensive care units. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(6):1275–1277. doi: 10.1111/inm.12800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Council of Bhutan Social and cultural affairs committee consults the team leader of national Covid 19 mental health and psychosocial response team Thimphu 2021. https://www.nationalcouncil.bt/dz/media/view_news_detail/807 Available online:

- 47.Druk gyalpo's relief Kidu. https://royalkidu.bt/category/news-press-release/ PRESS RELEASE, 21 March 2022. Available online:

- 48.World Health Organization Suicide prevention in Bhutan: scaling-up during the pandemic 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/suicide-prevention-in-bhutan-scaling-up-during-the-pandemic Available online:

- 49.Gyeltshen D., Dorji T. Doorstep delivery of essential healthcare services during the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown in Bhutan. Popul Med. 2020;2:43. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dema T., Gyeltshen D. Provision of dental health services during the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown in Bhutan. Popul Med. 2021;3:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bashshur R.L., Shannon G.W., Bashshur N., Yellowlees P.M. The empirical evidence for telemedicine interventions in mental disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(2):87–113. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dolkar D. Business Bhutan; 2021. Towards addressing the emerging mental health issue in the country.https://businessbhutan.bt/towards-addressing-the-emerging-mental-health-issue-in-the-country/#respond Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 53.Editorial. Mental health and well-being. Kuensel; 2021. https://kuenselonline.com/mental-health-and-well-being/ Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chhetri A. The Bhutanese; 2020. Over 60 calls associated with mental health in total since the lockdown.https://thebhutanese.bt/over-60-calls-associated-with-mental-health-in-total-since-the-lockdown/ Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barcella C.A., Polcwiartek C., Mohr G.H., et al. Severe mental illness is associated with increased mortality and severe course of COVID-19. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144:82–91. doi: 10.1111/acps.13309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wangdi P., Gyeltshen N. Nikkei Asia; 2020. Bhutan lifts tobacco ban to block COVID spillover from India.https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Bhutan-lifts-tobacco-ban-to-block-COVID-spillover-from-India Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clancy L., Gallus S., Leung J., Egbe C.O. Tobacco and COVID-19: understanding the science and policy implications. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18:105. doi: 10.18332/tid/131035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tamang S.T., Lhendup K., Dorji T. Control of travel-related COVID-19 in Bhutan. J Travel Med. 2021;28(7) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taab137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yayakumar P.B. Business Today; 2020. Alcohol non-availability kills more than coronavirus in Kerala; foreign liquor served as 'medicine'.https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/economy-politics/story/alcohol-non-availability-kills-more-than-coronavirus-in-kerala-foreign-liquor-served-as-medicine-253499-2020-03-31 Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 60.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2022. Policy response to alcohol consumption and tobacco use during the COVID-19 pandemic in the WHO South-East Asia Region: preparedness for future pandemic events. Snapshot series on alcohol control policies and practice. Brief 7, July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dorji P. 2020. Number of people dealing with anxiety and depression on the rise during the lockdown.http://www.bbs.bt/news/?p=135963 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ummer O., Scott K., Mohan D., Chakraborty A., LeFevre A.E. Connecting the dots: Kerala's use of digital technology during the COVID-19 response. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Corrigan P.W., Watson A.C. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2002;1(1):16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith K., Ostinelli E., Macdonald O., Cipriani A. COVID-19 and telepsychiatry: development of evidence-based guidance for clinicians. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(8) doi: 10.2196/21108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dorji T. The Gross national happiness framework and the health system response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Bhutan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104(2):441–445. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dem P. 2021. RUB colleges establish happiness and wellbeing centres.https://kuenselonline.com/rub-colleges-establish-happiness-and-wellbeing-centres/ Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 67.Doma D., Dolkar T. vol. 26. Shukutoku University Graduate School of Integrated Human and Social Welfare Studies bulletin; 2019. pp. 149–160. (Overview of counseling in Bhutan). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.