Abstract

The mutY homolog gene (mutYDr) from Deinococcus radiodurans encodes a 39.4-kDa protein consisting of 363 amino acids that displays 35% identity to the Escherichia coli MutY (MutYEc) protein. Expressed MutYDr is able to complement E. coli mutY mutants but not mutM mutants to reduce the mutation frequency. The glycosylase and binding activities of MutYDr with an A/G-containing substrate are more sensitive to high salt and EDTA concentrations than the activities with an A/7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (GO)-containing substrate are. Like the MutYEc protein, purified recombinant MutYDr expressed in E. coli has adenine glycosylase activity with A/G, A/C, and A/GO mismatches and weak guanine glycosylase activity with a G/GO mismatch. However, MutYDr exhibits limited apurinic/apyrimidinic lyase activity and can form only weak covalent protein-DNA complexes in the presence of sodium borohydride. This may be due to an arginine residue that is present in MutYDr at the position corresponding to the position of MutYEc Lys142, which forms the Schiff base with DNA. The kinetic parameters of MutYDr are similar to those of MutYEc. Although MutYDr has similar substrate specificity and a binding preference for an A/GO mismatch over an A/G mismatch, as MutYEc does, the binding affinities for both mismatches are slightly lower for MutYDr than for MutYEc. Thus, MutYDr can protect the cell from GO mutational effects caused by ionizing radiation and oxidative stress.

The bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans is extremely resistant to many lethal and mutagenic agents and conditions that damage DNA, including ionizing radiation, UV radiation, and hydrogen peroxide treatment (35). D. radiodurans is one of the most radiation-resistant organisms; exponentially growing cells are 200 times more resistant to ionizing radiation and 20 times more resistant to UV irradiation than Escherichia coli (2, 3). It has been suggested that this elevated resistance of D. radiodurans is due to unusually efficient DNA repair and recombination mechanisms (3, 36), but the molecular mechanisms responsible for radiation resistance remain unknown. Recently, many putative genes involved in DNA repair and recombination have been identified in the genome of D. radiodurans (27, 50). Information regarding the functions of these repair enzymes is emerging.

To protect their genomes from the oxidative DNA damage caused by ionizing radiation, cells have evolved efficient and accurate repair systems to remove DNA lesions (12). 7,8-Dihydro-8-oxoguanine (GO) is the most stable product known to be caused by oxidative damage to DNA. If not repaired, GO lesions in DNA can produce A/GO mismatches during DNA replication (43) and can result in transversions from G · C to T · A (9, 37, 38, 53). In E. coli, three enzymes, MutY, MutM (Fpg), and MutT, are known to be involved in defending against the mutagenic effects of GO lesions (32, 45). MutT hydrolyzes oxidized dGTP and depletes it from the nucleotide pool (28). The function of the MutM (Fpg) protein is to remove the mutagenic GO and other oxidized purines (46). MutY protein is responsible for correcting A/GO mismatches, as well as A/G and A/C mismatches (1, 23, 48). Thus, MutY provides a measure of defense by removing adenines misincorporated opposite GO or G following DNA replication (25, 31, 32). Homologs of putative MutY, MutM, and MutT are present in D. radiodurans (27, 50).

The E. coli MutY (MutYEc) protein is a 39-kDa iron-sulfur protein (33, 48, 49), and its N-terminal domain exhibits structural similarity with those of endonuclease III (endo III) and AlkA (6, 16, 33, 39, 48, 49). This includes the helix-hairpin-helix (HhH) and Gly/Pro…Asp loop motifs. The conserved Asp acts as a general base to activate a nucleophile, such as Lys or water. DNA glycosylases in the endo III superfamily can be divided into two groups (11, 13). Bifunctional DNA glycosylases, including endo III and human 8-oxoG glycosylase (hOGG1), use the conserved lysine (Lys120 in endo III and Lys249 in hOGG1) to form a Schiff base intermediate and also possess strong apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) lyase activity, which cleaves DNA 3′ to an AP site by a β-elimination mechanism (14, 39, 40, 47). Monofunctional glycosylases, such as AlkA, lack both the conserved lysine and AP lyase activity (17, 44, 56). The possession of AP lyase activity by MutY is controversial. MutY AP lyase activity has been detected by some researchers (15, 22, 25, 26, 29, 30, 48) but not by other groups (1, 7, 31, 34, 44). Although MutY lacks the conserved lysine, there is evidence that MutY may be a bifunctional glycosylase. MutY can cleave DNA containing an unmodified AP site (30, 54). The enzyme also forms a covalent complex with its DNA substrates in the presence of sodium borohydride (15, 26, 30, 51, 57), a diagnostic tool for bifunctional glycosylase/AP lyase (13, 40, 44). Lys142 of MutYEc has been shown to form the Schiff base intermediate with DNA (52, 54, 57); however, K142A mutant MutY has glycosylase activity (52, 54) and can promote β/δ elimination with AP-containing DNA (54). This raises the question of whether Schiff base formation is significant for the MutY function.

MutYEc has an additional C-terminal domain that has no counterpart in other members of the HhH family of proteins. Although the N-terminal domain of MutYEc exhibits catalytic activity (15, 29, 30, 41), the C-terminal domain has been shown to play an important role in recognition of GO lesions (15, 20, 41). The truncated MutY has >18-fold-lower binding affinities with GO-containing mismatches than the intact MutY has (20). Deletion of the C-terminal domain of MutY reduces its catalytic preference for A/GO-containing DNA over A/G-containing DNA (10, 20, 41) and confers a mutator phenotype in vivo (10, 20). Moreover, MutY uses its C-terminal domain to attenuate the catalytic activity of MutM (Fpg) protein (20). These findings strongly support the notion that the C-terminal domain of MutY plays an important role in GO recognition and mutation avoidance.

Because D. radiodurans is extremely resistant to oxidative stress, we tried to characterize and compare its MutY homolog (MutYDr) with MutYEc. Like MutYEc, MutYDr does not have the conserved lysine downstream of the HhH motif. In contrast to MutYEc, an Arg is at the position that corresponds to Lys142 of MutYEc. Our results indicate that MutYDr is a monofunctional adenine glycosylase. The substrate specificities and kinetic parameters of MutYDr are similar to those of MutYEc. MutYDr that is expressed is able to complement E. coli mutY mutants but not mutM mutants to reduce the mutation frequency. Although MutYDr can protect D. radiodurans from GO mutational effects, we identified no specific properties of MutYDr that were drastically different from MutYEc properties that could contribute to the high levels of resistance to ionizing radiation and oxidative stress of this organism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and DNA.

The genomic DNA of D. radiodurans R1 was obtained from M. J. Bessman. E. coli PR8 (Su− lacZ X74 galK Smr) and PR70 (like PR8 but micA68::modified Tn10) were obtained from M. S. Fox. E. coli CC104 [ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 F′(lacI378 lacZ461 proA+B+)] and CC104/mutYmutM (like CC104 but mutY::mini-Tn10 mutM) were obtained from J. H. Miller. E. coli MV1161 [thr-1 ara-14 leuB6 Δ(gpt-proA)62 lacY1 tsx-33 supE33 galK2 hisG4 rfbD1 mgl-51 rpsL31 kdgK51 xyl-5 mtl-1 argE3 thi-1 rfa-550] and MV3867 (like MV1161 but mutM472::Tn10) were obtained from M. Volkert. E. coli Tuner(DE3) [F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm lacY1 (DE3)] and DH5α [supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZ ΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1] were obtained from Novagen and Life Technologies, Inc., respectively. Cells harboring λDE3 lysogen were constructed by using the procedures described by Invitrogen.

The annealed 19-mer oligonucleotide DNA substrates used in this study were as follows: 5′ CCGAGGAATTXGCCTTCTG 3′ and 3′ GCTCCTTAAYCGGAAGACG 5′ (X = A, C, G, T, 2-aminopurine, or U; Y = C, G, or GO). Duplex DNA containing base mismatches were labeled at the 3′ or 5′ ends as described by Lu (21). After the sticky ends were filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, the 19-mer was converted into a 20-mer. DNA substrates containing U/G or U/GO (300 fmol) were fully converted to AP/G- or AP/GO-containing DNA substrates by treatment with 1.5 U of E. coli uracil DNA glycosylase (Life Technologies, Inc.) at 37°C for 1 h in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 80 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, and 2.9% glycerol.

Cloning of MutYDr.

According to the previously published genomic sequence of D. radiodurans R1 (accession no. NC001263) (50), the putative mutY homolog sequence (DR2285) contains 1,089 base pairs and codes for a 363-residue protein. To clone the MutYDr gene, we synthesized the following set of PCR primers: forward strand, 5′-GCGCGCTCATGACGTTGCCCGTGTCTGCC-3′; and reverse strand, 5′-GGCGCGCCTTACGCCTCGCCCAGCGGGGAACTG-3′. Genomic DNA prepared from D. radiodurans R1 was used as a template for PCRs. The PCR mixtures (100 μl) contained 20 ng of chromosomal DNA, 100 pmol of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 5 U of Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The reactions were performed as follows: 95°C for 2.0 min, 60°C for 1.0 min, 72°C for 2.0 min for 30 cycles, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The 1.1-kb PCR product was purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN), digested with BspHI and AscI, ligated into NcoI- and AscI-digested pETBlue-2 vector (Novagen), and transformed into DH5α cells. Sequence analysis of a selected clone (pETBlue-2DR2285) (GenBank accession no. AF377342) revealed that its DNA sequence is exactly the same as the sequence predicted for MutYDr (accession no. NC001263).

Measurement of mutation frequency.

Plasmid pETBlue-2DR2285 was transferred to E. coli PR70/DE3 (mutY), CC104/DE3/mutYmutM, and MV3867/DE3 (mutM) cells to check their mutation frequencies. Independent overnight cultures were grown to an A590 of 0.7 in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing 50 mg of ampicillin per ml when necessary. After 2.5 h of induction by 0.1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, 0.1 ml of cells from each culture was plated onto LB agar containing 0.1 mg of rifampin per ml. The cell titer of each culture was determined by plating a 106 dilution onto LB agar. The ratio of Rifr cells to total cells was the mutation frequency.

Overexpression and purification of MutYDr.

Plasmid pETBlue-2DR2285 was transferred into Tuner(DE3) cells to express the 39.4-kDa MutYDr protein. Six liters of a MutYDr-overproducing strain was grown to an A590 of 0.7 in LB broth containing 50 mg of carbenicillin per ml at 37°C. The cells were induced by adding isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside to a concentration of 0.8 mM, cultured overnight at 20°C, and harvested by centrifugation.

All column chromatography steps were conducted with a Waters 650E fast protein liquid chromatography system at 4°C, and preparations were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min. Cells (22 g of cell paste) were resuspended in 120 ml of buffer T (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and disrupted with a bead beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.) using 0.1-mm-diameter glass beads. After the cell debris was removed by centrifugation, the supernatant was saved as fraction I, which was then treated with 5% streptomycin sulfate. After 45 min of stirring, the solution was centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected and designated fraction II (172 ml). Ammonium sulfate (50 g) was added to fraction II to a final concentration of 50%, the preparation was stirred for 45 min, and the protein was precipitated overnight. After centrifugation, the protein pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of buffer T and dialyzed against two changes consisting of 1 liter of the same buffer for 1.5 h each. The dialyzed protein sample was diluted to 34.5 ml with buffer T. After centrifugation, the supernatant was designated fraction III (34.5 ml). Fraction III was loaded onto a 30-ml phosphocellulose column which had been equilibrated with buffer A (20 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.2], 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing 25 mM KCl. After a washing with 75 ml of equilibration buffer, proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of KCl (0.025 to 0.5 M) in buffer A. The fractions that eluted between 24.5 and 31.5 mM KCl were pooled and designated fraction IV (65 ml). Fraction IV was loaded onto a 16-ml hydroxylapatite column equilibrated with buffer B (0.01 M potassium phosphate [pH 7.2], 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The flowthrough and early elution fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer A without KCl for 2 h; the resulting preparation was designated fraction V (73 ml). Fraction V was loaded onto an 8-ml MonoQ column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with buffer A containing 25 mM KCl. After the column was washed with 20 ml of equilibration buffer, it was developed with an 80-ml linear gradient of KCl (0.025 to 0.5 M) in buffer A. Fractions containing the MutY glycosylase activity, which eluted between 0.23 and 0.3 M KCl, were pooled and diluted with 2 volumes of buffer A, which yielded fraction VI (22.5 ml). Fraction VI was then applied to a 1-ml MonoS column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) that had been equilibrated with buffer A containing 25 mM KCl. After the column was washed with 20 ml of equilibration buffer A, it was eluted with an 80-ml linear gradient of KCl (0.025 to 0.5 M) in buffer. Fractions containing the MutY glycosylase activity, which eluted between 0.15 and 0.3 M KCl, were pooled (7 ml) and concentrated with Centricon-30 (Millipore) to a volume of 0.5 ml; this yielded fraction VIIc, which was divided into small aliquots that were stored at −80°C. Cleavage of A/GO-containing 20-mer DNA was assayed during purification of the recombinant MutYDr enzyme. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (5).

MutYDr binding assay.

Binding of MutYDr to various oligonucleotides was assayed by a gel retardation procedure similar to a procedure described previously (21). 32P-labeled 20-bp oligonucleotides (1.8 fmol) were incubated with MutYDr in 20 μl of binding buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 20 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2.9% glycerol, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, and 5 ng of poly(dI-dC) at 37°C for 30 min. MutYDr protein was diluted with a buffer containing 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), 1.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 50 mM KCl, 200 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, and 50% glycerol. Protein-DNA complexes were analyzed on 8% polyacrylamide gels in 50 mM Tris borate (pH 8.3)–1 mM EDTA. The apparent dissociation constants (Kd values) of MutYDr and DNA were determined by using nine MutYDr concentrations, and experiments were repeated at least three times. Bands corresponding to enzyme-bound and free DNA were quantified by using PhosphoImager images, and Kd values were obtained from analyses by using a computer-fitted curve generated by the Enzfitter program (19).

MutYDr glycosylase assay.

Glycosylase assays were carried out like the binding assay except that no poly(dI-dC) was added to 10-μl reaction mixtures. Unless specified otherwise, after incubation at 37°C for 30 min, reaction mixtures were dried with a Speed Vac (Savant), resuspended in 3 μl of formamide dye (90% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% xylene cyanol, 0.1% bromophenol blue), heated at 90°C for 2 min, and loaded onto 14% polyacrylamide–7 M urea sequencing gels that were electrophoresed at 2,000 V. To test for AP lyase activity, the glycosylase reactions were performed in 10-μl reaction mixtures. In reaction condition I, the sample was supplemented with 5 μl of formamide dye and directly loaded onto a gel that was electrophoresed at 1,000 V without drying and heating. The sample in reaction condition II was supplemented with 5 μl of formamide dye and heated at 90°C for 2 min before it was loaded onto a gel without drying. The sample in reaction condition III was treated with 1 M piperidine at 90°C for 30 min after the reaction, dried, resuspended in 3 μl of formamide dye, and heated at 90°C for 2 min.

For time course studies, after enzyme reactions at different times, samples were immediately frozen at −70°C and then heated at 90°C for 30 min with 1 M piperidine, dried, resuspended in 3 μl of formamide dye, and heated at 90°C for 2 min. Data were obtained from PhosphorImager quantitative analyses of gel images in three experiments. The percentages of DNA cleaved were plotted as a function of time. Kinetic analyses were performed by using DNA substrate concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 1,024 mM with 0.5 nM MutYDr. Bands corresponding to cleavage products and intact DNA were quantified by using PhosphoImager images, and Km and Vmax values were obtained from analyses by using a computer-fitted curve generated by the Enzfitter program (19).

Formation of enzyme-DNA covalent complex.

Reactions were carried out as described above for the MutYDr glycosylase assay, except that the reactions were performed in the presence of NaBH4. An NaBH4 stock solution was freshly prepared immediately prior to use. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) dye (final concentrations, 30 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.9], 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1% [wt/vol] SDS, 1% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1 mg of bromophenol blue per ml) was added to the samples, which were heated at 90°C for 2 min and separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of SDS as described by Laemmli (18), and the gel was dried and exposed to a PhosphoImager screen.

RESULTS

Analysis of the MutYDr protein sequence.

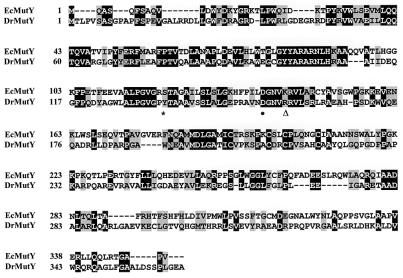

Because D. radiodurans is extremely resistant to oxidative stress, we tried to clone the mutY gene homolog(s) from the sequenced genome (50). A Blast search identified four open reading frames that exhibit high levels of homology with MutYEc: DR2285, DR0289, DR2438, and DR0928. Only DR2285 contains the extra C-terminal domain like MutYEc. Because the C-terminal domain of MutYEc has no counterpart in other proteins belonging to the HhH family, the presence of this domain in DR2285 suggests that DR2285 is a putative MutY homolog. DR2285 (designated MutYDr) contains 363 amino acid residues and exhibits 35% identity to MutYEc, as determined by an ALIGN program (Fig. 1). Specifically, two regions with the highest levels of similarity were found; residues 127 to 132 of MutYDr are located at the conserved HhH motif, and residues 189 to 219 of MutYDr contain the iron-sulfur domain with four conserved Cys residues (16).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of amino acid sequences of MutYDr and MutYEc. Identical and conserved residues are indicated by black and gray boxes, respectively. The sequences used were the sequences of E. coli MutY (EcMutY) (accession no. P17802) and D. radiodurans MutY (DrMutY) (accession no. NC 001263). The conserved Asp residue is indicated by a dot. The position of Ser120 of MutYEc and Tyr134 of MutYDr at the conserved Lys downstream of the HhH motif of the HhH family is indicated by an asterisk. A triangle indicates the position of Lys142 of MutYEc and Arg156 of MutYDr.

Reduction of the mutation frequency of an E. coli mutY mutant by MutYDr.

To demonstrate that the putative MutYDr protein is a functional homolog of MutYEc in vivo, we measured the mutation frequencies of MutYDr-expressing E. coli strains. The mutYDr gene under control of the T7 promoter in the pETBlue-2 vector was expressed in three E. coli strains, PR70/DE3 (mutY), MV3867/DE3 (mutM), and CC104/DE3/mutYmutM (mutY mutM double mutant). As shown in Table 1, the mutY mutant (PR70/DE3) exhibited a 46-fold-higher mutation frequency than the wild-type PR8 strain. PR70/DE3 cells expressing MutYDr had a mutation frequency as low as that of the wild-type cells, while the vector pETBlue-2 alone had a 22-fold-higher mutation frequency than the wild type (Table 1). Table 1 shows that the mutY mutM double mutant (CC104/DE3/mutYmutM) exhibited a mutation frequency that was more than 900-fold higher than that of wild-type strain CC104/DE3. CC104/DE3/mutYmutM cells expressing MutYDr could have a mutation rate close to that of the wild type (Table 1). No obvious effect was observed when MutYDr was expressed in the mutM mutant strain, MV3867/DE3. Thus, MutYDr indeed is a MutYEc functional homolog.

TABLE 1.

Mutation frequencies of E. coli mutY and mutM mutants expressing MutYDr

| Strain | Mutation frequency (Rifr colonies/108 cells) | Increase (fold)a |

|---|---|---|

| PR8 (wild type) | 3 | 1 |

| PR70 (mutY) | 137 | 46 |

| PR70/pETBlue-2 | 65 | 22 |

| PR70/pDrMutY | 8 | 3 |

| CC104 (wild type) | 6 | 1 |

| CC104 (mutY mutM) | 5,619 | 937 |

| CC104/pETBlue-2 | 2,859 | 477 |

| CC104/pDrMutY | 24 | 4 |

| MV1161 (wild type) | 7 | 1 |

| MV3867 (mutM) | 386 | 55 |

| MV3867/pETBlue-2 | 881 | 125 |

| MV3867/pDrMutY | 779 | 111 |

Increase compared with the wild type.

Effects of salt and EDTA on the binding and glycosylase activities of MutYDr.

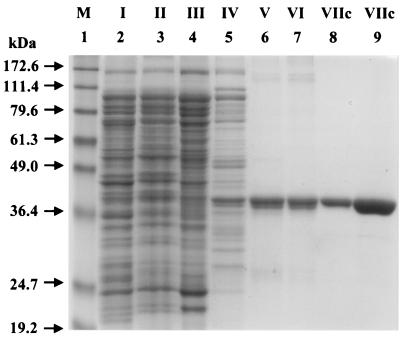

To further demonstrate that MutYDr encodes a functional MutY protein, we purified the recombinant MutYDr expressed in E. coli Tuner(DE3) and assayed its activities. The MutYDr protein was purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation and phosphocellulose, hydroxylapatite, MonoQ, and MonoS chromatographic steps. We recovered about 19 mg of MutYDr protein from 22 g of cell paste. As judged on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel, the protein was purified to >99% homogeneity (Fig. 2, lane 9). The mobility of MutYDr (the single band in Fig. 2, lane 8) in the denatured gel matched the predicted size (39.4 kDa). The MutYDr band in fraction VIIc cross-reacted weakly with polyclonal antibodies against MutYEc and the MutY homolog (MYH) of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel analysis of MutYDr. The proteins were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of SDS and stained with Coomassie blue. Protein markers (Gibco BRL prestained protein marker) were run in lane 1. Lanes 2 to 9 contained fractions I (11 μg; crude cell extract), II (11 μg; fraction after streptomycin sulfate treatment), III (7.3 μg; fraction after ammonium sulfate treatment), IV (3 μg; fraction after phosphocellulose column elution), V (1.8 μg; fraction after hydroxylapatite column elution), VI (1.5 μg; fraction after MonoQ column elution), VIIc (1.5 μg; fraction after MonoS column elution), and VIIc (7.5 μg; fraction after MonoS column elution), respectively. Excess protein was loaded in lane 9 to show the degree of homogeneity.

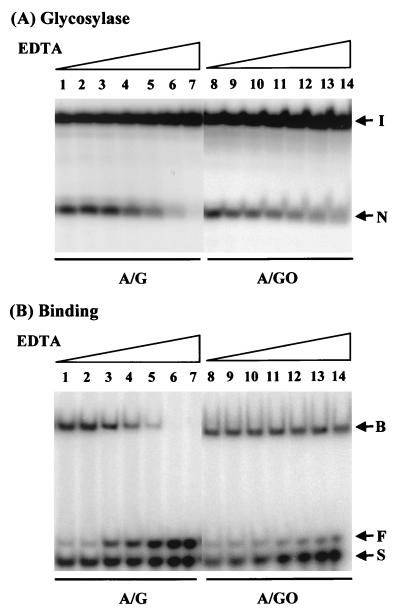

Because S. pombe MYH glycosylase activity with an A/G mismatch is sensitive to EDTA and NaCl (24), we tried to find the optimal reaction conditions for MutYDr. When the NaCl concentration was 80 mM, the MutYDr glycosylase activities with A/G and A/GO mismatches were 40 and 60%, respectively, of the activities in the absence of salt (data not shown). At an NaCl concentration of 80 mM, while the MutYDr binding to an A/G mismatch was 23% of the binding in the absence of salt, the binding to an A/GO mismatch was comparable to the binding in the absence of salt (data not shown). The effect of EDTA on the glycosylase and binding activities of MutYDr is shown in Fig. 3. The MutYDr glycosylase activities with A/G and A/GO mismatches were not inhibited by 10 mM EDTA (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 10), but the glycosylase activity with an A/G mismatch was eliminated by 50 mM EDTA (Fig. 3A, lane 7). Like the glycosylase activity, MutYDr binding to an A/G mismatch was more sensitive to high concentrations of EDTA than binding to an A/GO mismatch was (Fig. 3B). Thus, a reaction buffer containing 20 mM NaCl and 0.1 mM EDTA was used in the MutYDr assay.

FIG. 3.

Effects of EDTA on MutYDr binding and glycosylase activities with A/G- and A/GO-containing DNA. (A) Glycosylase activity. Oligonucleotide 20-mer DNA containing an A/G (lanes 1 to 7) or A/GO (lanes 8 to 14) mismatch was reacted with MutYDr for 30 min at 37°C in the presence of different EDTA concentrations. MutYDr reactions were carried out in buffers in the presence of 1 mM (lanes 1 and 8), 5 mM (lanes 2 and 9), 10 mM (lanes 3 and 10), 20 mM (lanes 4 and 11), 30 mM (lanes 5 and 12), 40 mM (lanes 6 and 13), and 50 mM (lanes 7 and 14) EDTA. The reaction products were analyzed on a 14% polyacrylamide DNA sequencing gel. The arrows indicate the positions of intact oligonucleotide (arrow I) and nicking product (arrow N). (B) DNA binding activity. The EDTA concentrations used were similar to those used in the experiment whose results are shown in panel A. Protein-DNA complexes were analyzed on 8% polyacrylamide gels in 50 mM Tris borate (pH 8.3)–1 mM EDTA. The arrows indicate the positions of protein-bound DNA (arrow B), protein-free double-stranded DNA (arrow F), and single-stranded DNA (arrow S).

MutYDr exhibits adenine DNA glycosylase activity and weak guanine DNA glycosylase activity but limited AP lyase activity.

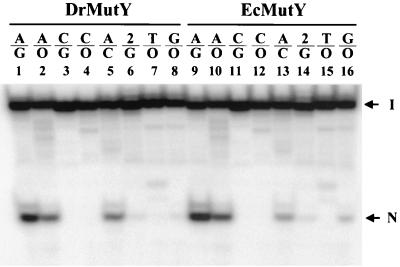

The glycosylase activities of MutYDr and MutYEc with several mismatches were compared. As shown in Fig. 4, MutYDr could cleave a 20-mer oligonucleotide containing an A/G, A/GO, or A/C mismatch. An A/C mismatch was a better substrate for MutYDr than for MutYEc (Fig. 4, compare lanes 5 and 13). MutYDr also exhibited weak guanine DNA glycosylase activity with G/GO mismatch-containing DNA, and this activity was weaker than that of MutYEc (Fig. 4, compare lanes 8 and 16). In addition, 2-aminopurine/G was also a weak substrate of MutYDr (Fig. 4, lane 6). MutYDr exhibited no catalytic activity with C/G, C/GO, and T/GO mismatches (Fig. 4, lanes 3, 4, and 7). This substrate specificity is very similar to that of MutYEc (Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 to 8 with lanes 9 to 16).

FIG. 4.

Glycosylase activities of MutYDr (DrMutY) and MutYEc (EcMutY) with different mismatches. Oligonucleotide substrates (3′-end-labeled 20-mers; 1.8 fmol) containing the mismatches indicated above the lanes were incubated with 3.6 nM MutYDr (lanes 1 to 8) or 3.6 nM MutYEc (lanes 9 to 16) for 30 min at 37°C. Abbreviations: O, GO; 2, 2-aminopurine. The arrows indicate the positions of intact DNA substrate (arrow I) and the cleaved DNA fragment (arrow N). The minor band above the cleaved product was derived from an impurity of DNA substrates that appeared above the intact DNA.

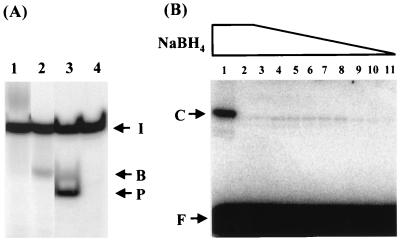

In order to determine whether MutYDr exhibits AP lyase activity, the reaction products of MutYDr with 5′-end-labeled A/GO-containing DNA were treated under different conditions and separated on a sequencing gel electrophoresed at a lower voltage than that used for the gel shown in Fig. 4. Three reactions were carried out for the MutYDr cleavage assays. In reaction condition I the sample was directly loaded onto the gel without drying and heating, in reaction condition II the sample was not dried but was heated at 90°C for 2 min before loading onto the gel, and in reaction condition III the sample was treated with 1 M piperidine for 30 min at 90°C after the reaction in addition to being dried and heated at 90°C for 2 min. In the reaction condition I experiment, MutYDr did not produce a cleavage product, but a smeared band that migrated more slowly than the intact DNA was observed (Fig. 5A, lane 1). The smeared band may have been a MutYDr-DNA complex. In the reaction condition II experiment with 90°C heating, a weak cleavage product with a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde was observed (Fig. 5A, lane 2, arrow B). Further treatment of the products with piperidine at 90°C (a treatment that promotes β- and δ-elimination) for 30 min resulted in a significant increase in the extent of cleavage (Fig. 5A, lane 3). The major product was a small fragment with a 3′ phosphate group (Fig. 5A, arrow P). This suggests that the majority of products of MutYDr are in the intact AP/GO form. The condition used in the experiment, the results of which are shown in Fig. 4, resulted in a level of cleavage similar to that obtained in the reaction condition III experiment (data not shown). When AP/G- and AP/GO-containing DNA substrates were reacted with MutYDr, no cleavage of unmodified AP-containing DNA was observed with increasing amounts of MutYDr (data not shown). In contrast, MutYEc has detectable cleavage activity with AP-containing DNA (54). Thus, MutYDr lacks efficient AP lyase activity.

FIG. 5.

MutYDr exhibits limited AP lyase activity. (A) Glycosylase reactions performed under different reaction conditions. Lane 1, sample supplemented with 5 μl of formamide dye and directly loaded onto a gel that was electrophoresed at 1,000 V without drying and heating; lane 2, sample supplemented with 5 μl of formamide dye and heated at 90°C for 2 min before it was loaded onto a gel without drying; lane 3, sample treated with 1 M piperidine at 90°C for 30 min after the reaction, dried, resuspended in 3 μl of formamide dye, and heated at 90°C for 2 min; lane 4, DNA alone. The samples were from concurrent experiments, but the products were separated on nonadjacent lanes in one sequencing gel. The arrows indicate the positions of intact oligonucleotide (arrow I), products with a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde formed via β-elimination (arrow B), and products with a 3′ phosphate formed via β/δ-elimination by piperidine (arrow P). (B) Formation of covalent complexes of MutYDr and A/GO-containing DNA in the presence of various concentrations of NaBH4. Lane 1, reaction mixture containing 72 fmol of E. coli MutY in MutYEc buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, 2.9% glycerol) in the presence of 100 mM NaBH4; lanes 2 to 11, reaction mixtures containing 14.4 fmol of MutYDr with different concentrations of NaBH4 (100, 80, 60, 50, 40, 30, 20, 15, 10, and 5 mM, respectively). The products after heating at 90°C for 2 min were fractionated in an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel. The positions of free oligonucleotide (arrow F) and a covalent complex (arrow C) are indicated by arrows.

If MutYDr has AP lyase activity and uses a mechanism similar to that of MutYEc (15, 26, 30, 51, 57), an imino intermediate should be reduced by sodium borohydride (NaBH4) to form a stable covalent protein-DNA complex. Thus, DNA containing an A/GO mismatch was incubated with MutYDr in the presence of different concentrations of NaBH4. As shown in Fig. 5B, MutYDr could be weakly trapped in covalently linked protein-DNA complexes in the presence of NaBH4. The efficiency was much lower than that observed with MutYEc. The optimal trapping concentration of NaBH4 was about 20 to 60 mM. At 100 mM NaBH4, MutYEc could be trapped efficiently, but the ability to trap MutYDr was minimal (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 1 and 2). The effect of NaBH4 is consistent with the inhibition of MutYDr cleavage activity by 80 mM NaCl (data not shown). Because an arginine residue is present in MutYDr at the position corresponding to MutYEc Lys142, the weak covalent complexes of MutYDr with DNA substrates suggest that MutYDr may use a different lysine residue to react with the nearby AP site. Because Schiff base formation is an important criterion for bifunctional DNA glycosylase activity with AP lyase activity, our results suggest that the MutYDr protein has limited AP lyase activity.

Kinetic parameters of MutYDr.

The efficiencies of cleavage by MutYDr and MutYEc of a 20-mer oligonucleotide containing A/G or A/GO were compared (Table 2). As measured at a protein concentration of 0.5 nM, the Km and Vmax values for MutYDr with an A/G mismatch were slightly higher than the MutYEc values. The turnover number (Kcat) for MutYDr with an A/G 20-mer was two times higher than that of MutYEc. However, MutYDr and MutYEc have similar reactivities with both A/G- and A/GO-containing DNA, as measured by specificity constants (Kcat/Km).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of MutYDr and MutYEc

| Enzyme | DNA | Km (nM) | Vmax (pM · min−1) | kcat (min−1) | kcat · Km−1 (min−1 · μM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MutYDr | A/G-20b | 8.5 ± 1.3 | 34 ± 2 | 0.068 ± 0.003 | 8 |

| A/GO-20 | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 8.6 ± 1.0 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 4 | |

| MutYEca | A/G-20 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 21 ± 2 | 0.026 ± 0.002 | 10 |

| A/GO-20 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 17 ± 2 | 0.021 ± 0.002 | 3 |

Data for MutYEc were obtained from reference 26.

A/G-20 and A/GO-20 are 20-mer oligonucleotides containing A/G and A/GO mismatches, respectively.

Time course of MutYDr activity with A/G- and A/GO-containing DNA.

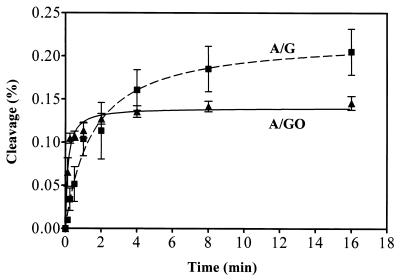

The steady-state kinetics of the MutYDr reaction (Table 2), as measured at 37°C for 30 min, cannot reflect the true reactivity because the enzyme may have a low turnover rate. Thus, we used single-turnover glycosylase kinetics to compare the reactivities of MutYDr with A/G- and A/GO-containing DNA substrates. Time course studies to determine the extents of glycosylase activity with both A/G- and A/GO-containing substrates were performed. As shown in Fig. 6, the rate of cleavage of MutYDr with A/G-containing DNA was lower than the rate of cleavage with A/GO-containing DNA for the first 2 min. The times required to reach 50% of the maximum levels with A/G- and A/GO-containing DNA were 1.28 and 0.14 min, respectively. The difference in the reaction rates was more than ninefold. Figure 6 also shows that at a steady state (>3 min), the MutYDr glycosylase activity with a A/GO mismatch was weaker than that with A/G-containing DNA. This result is similar to previous findings for MutYEc (20).

FIG. 6.

Time course studies of MutYDr glycosylase activities with A/G- and A/GO-containing DNA. A/G-containing (▪) and A/GO-containing (▴) 20-mer oligonucleotides (1.8 fmol) were incubated at 37°C with 72 fmol of MutYDr for various times. After reaction, the products were treated with piperidine, dried, resuspended in formamide dye, heated at 90°C for 2 min, and analyzed on a 14% polyacrylamide denaturing sequencing gel. Data were obtained from PhosphorImager quantitative analyses of gel images from three experiments. The percentages of DNA cleaved were plotted as a function of time.

Binding affinities of MutYDr and MutYEc with different mismatches.

Because MutYDr and MutYEc have similar glycosylase activities with different substrates (Fig. 4), we determined the apparent dissociation constants (Kd) of MutYDr with A/G-, AP/G-, and GO-containing mismatches. As shown in Table 3, MutYDr exhibited >100-fold-greater affinity with A/GO-containing DNA than with A/G-containing DNA. MutYDr also exhibited affinity with the reaction products AP/G and AP/GO. The affinity of MutYDr with the AP/G product was 5.5-fold higher than that with the A/G substrate, while the affinity with the AP/GO product was slightly lower than that with the A/GO substrate. The MutYDr binding to a C/GO mismatch was 250-fold lower than that to a A/GO mismatch but only 2-fold lower than that to an A/G mismatch. MutYDr exhibited high affinity to a weakly catalytic G/GO substrate and a noncatalytic T/GO substrate (Fig. 4). The Kd values for MutYDr are similar to those for MutYEc, but the binding affinities of MutYDr with all of the substrates tested were slightly lower than those of MutYEc.

TABLE 3.

Apparent dissociation constants of MutYDr and MutYEc for mismatch-containing DNA

| DNA duplex | MutYDrKd (nM) | MutYEcKd (nM) | MutYDr/ MutYEc ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| A/G-20c | 19.9 ± 2.3 | 5.3 ± 0.5a | 3.8 |

| A/GO-20 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.01a | 2.4 |

| AP/G-20 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.3b | 1.7 |

| AP/GO-20 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.11b | 1.6 |

| C/GO-20 | 40.1 ± 2.1 | 11.5 ± 3.8b | 3.5 |

| T/GO-20 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.01b | 1.8 |

| G/GO-20 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 0.11 ± 0.01b | 3.3 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that the DR2285 open reading frame of D. radiodurans encodes a MutY homolog. Expressed MutYDr is able to complement the mutator phenotypes of an E. coli mutY mutant and an E. coli mutY mutM double mutant (Table 1). This conservation of the repair function is not surprising as MutYDr has high sequence homology with MutYEc (Fig. 1). This is the first demonstration that an enzyme involved in repairing oxidized bases of D. radiodurans can complement E. coli mutants. We also demonstrated biochemically that MutYDr has MutYEc-like activities. Thus, the biological significance of MutYDr is similar to that of MutYEc in terms of removal of adenines misincorporated opposite GO lesions and reduction of C · G→A · T transversions in the D. radiodurans R1 genome.

Biochemical activities of MutYDr resemble activities of MutYEc. Like the MutYEc protein, purified recombinant MutYDr expressed in E. coli exhibits adenine glycosylase activity with A/G, A/C, and A/GO mismatches and weak guanine glycosylase activity with G/GO mismatches. The substrate specificity and kinetic parameters of MutYDr are similar to those of MutYEc. An A/C mismatch substrate is a better substrate and a G/GO mismatch substrate is a worse substrate for MutYDr than for MutYEc. Although the Km and Vmax values for MutYDr with A/G mismatches are slightly higher than the corresponding MutYEc values, the specificity constants (Kcat/Km) with the same mismatches are similar for the two enzymes. The binding affinities of MutYDr with all of the substrates tested are slightly lower than those of MutYEc. It is interesting that the affinities of MutYDr and MutYEc with the AP/G product were 5.5- and 2-fold fold higher, respectively, than those with the A/G substrate. The tighter binding to AP/G may recruit other enzymes to complete the repair process.

MutYDr has much less AP lyase activity than MutYEc. First, very limited DNA strand cleavage was observed if the product was not heated at 90°C. Piperidine treatment significantly increased strand cleavage by β- and δ-elimination (Fig. 5). Second, when AP/GO-containing DNA was used as the substrate, as the concentration of MutYDr was increased, the amount of the β-elimination product did not increase compared with the control (enzyme dilution only). Third, MutYDr could form only a weak covalent protein-DNA complex in the presence of sodium borohydride, while the catalytic activity of MutYDr was similar to that of MutYEc. This may have been due to an arginine residue that is present in MutYDr at the position corresponding to MutYEc Lys142, which forms the Schiff base with DNA. Thus, MutYDr most likely belongs to the group of monofunctional DNA glycosylases.

In E. coli, MutY, MutM, and MutT are involved in defending against the mutagenic effects of GO lesions (32, 45), and similar mechanisms to protect cells from the deleterious effects of GO are present in human cells. Homologs of putative MutY, MutM, and MutT proteins are present in D. radiodurans (27, 50). An activity similar to MutMEc activity has been detected in D. radiodurans R1 (4, 42). In contrast to MutMEc (8), MutMDr is able to excise GO from A/GO mismatches at a detectable rate (42), and the excision rates for 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxyl-5-formamidopyrimidine (FapyGua) and 4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine (FapyAde) are significantly greater than that for GO when these lesions are paired with C (42). Remarkably, there are 21 potential MutT homologs called Nudix hydrolases in the D. radiodurans R1 genome (27, 50). The D. radiodurans R1 Nudix hydrolases contain the conserved Nudix box (GX5EX7REUXEEXGU, where U is usually I, V, or L) and can hydrolyze nucleoside diphosphate derivatives (55). However, it is unlikely that many of these Nudix hydrolases are functional homologs of MutTEc because several of them cannot complement an E. coli mutT strain (55). Bauche and Laval (4) reported that MutY-like activity could not be detected in crude extracts of D. radiodurans R1. Our study showed that D. radiodurans R1 does have MutYDr activity that removes adenines from A/G- and A/GO-containing DNA and can complement an E. coli mutY mutation. Thus, MutYDr can protect D. radiodurans from GO mutational effects. However, no specific properties of MutYDr were found to be drastically different from MutYEc properties and to contribute to the high resistance to ionizing radiation and oxidative stress of the organism. On the other hand, MutYDr may have undiscovered activities that are different from MutYEc activities. So far, the reason(s) for the high tolerance to oxidative stress remains unknown. Comparison of repair and recombination enzymes of D. radiodurans and another highly radiation-resistant bacterium, Rubrobacter radiotolerans, may shed some slight on this.

In view of the fact that MutMDr can excise GO from A/GO mismatches and cleave at AP sites (42), it is important that MutYDr binds tightly to A/GO and AP/GO. MutYDr should be the preferred enzyme to act on A/GO mismatches in which adenines are misincorporated opposite template GO. After the removal of adenines from A/GO mismatches by MutYDr, the remaining AP/GO is a substrate for MutMDr (4). If MutYDr were to release this product before repair synthesis, MutMDr would incise both the AP site and the GO lesion, resulting in a double-stranded break. Strong binding to AP/GO by MutYDr minimizes this potential lethal action. The tight binding of MutYDr to the catalytically inactive substrate T/GO and weak substrate G/GO may also have biological significance. It has been shown that MutYEc can attenuate the MutMec glycosylase activity (20). Similar to the E. coli MutY-MutM interaction, the binding of MutYDr to T/GO and G/GO may inhibit MutMDr activity with these substrates. It remains to be determined whether MutMDr can act on T/GO and G/GO mismatches. The modulation of MutM activity is especially important if T/GO and G/GO mismatches arise from misincorporation of T and G opposite oxidized guanines on the template strand and if T/GO mismatches are derived from deamination of 5-methylcytosine opposite GO. The removal of GO from T/GO and G/GO mismatches, when GO is on the parental strand, can lead to G · C→A · T transitions and G · C→C · G transversions, respectively. Hence, it is reasonable that MutMDr activity with these unfavorable substrates is inhibited.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maurice J. Bessman at Johns Hopkins University for kindly providing the genomic DNA of D. radiodurans R1.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM 35132 from NIGMS, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Au K G, Clark S, Miller J H, Modrich P. Escherichia coli mutY gene encodes an adenine glycosylase active on G/A mispairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8877–8881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battista J R. Against all odds: the survival strategies of Deinococcus radiodurans. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:203–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battista J R, Earl A M, Park M J. Why is Deinococcus radiodurans so resistant to ionizing radiation? Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:362–365. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauche C, Laval J. Repair of oxidized bases in the extremely radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:262–269. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.262-269.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruner S D, Norman D P, Verdine G L. Structural basis for recognition and repair of the endogenous mutagen 8-oxoguanine in DNA. Nature. 2000;403:859–866. doi: 10.1038/35002510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulychev N V, Varaprasad C V, Dorman G, Miller J H, Eisenberg M, Grollman A P. Substrate specificity of Escherichia coli MutY protein. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13147–13156. doi: 10.1021/bi960694h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castaing B, Geiger A, Seliger H, Nehls P, Laval J, Zelwer C, Boiteux S. Cleavage and binding of a DNA fragment containing a single 8-oxoguanine by wild type and mutant FPG proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2899–2905. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.12.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng K C, Cahill D S, Kasai H, Nishimura S, Loeb L A. 8-Hydroxyguanine, an abundant form of oxidative DNA damage, causes G-T and A-C substitutions. J Biol Chem. 1991;267:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chmiel N H, Golinelli M P, Francis A W, David S S. Efficient recognition of substrates and substrate analogs by the adenine glycosylase MutY requires the C-terminal domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:553–564. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David S S, Williams S D. Chemistry of glycosylase and endonuclease involved in base-excision repair. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1221–1261. doi: 10.1021/cr980321h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demple B, Harrison L. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: enzymology and biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:915–948. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodson M L, Michaels M L, Lloyd R S. Unified catalytic mechanism for DNA glycosylases. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32709–32712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodson M L, Shrock R D I, Lloyd R S. Evidence for an imino intermediate in the T4 endonuclease V reaction. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8284–8290. doi: 10.1021/bi00083a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gogos A, Cillo J, Clarke N D, Lu A-L. Specific recognition of A/G and A/8-oxoG mismatches by Escherichia coli MutY: removal of the C-terminal domain preferentially affects A/8-oxoG recognition. Biochemistry. 1996;35:16665–16671. doi: 10.1021/bi960843w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan Y, Manuel R C, Arvai A S, Parikh S S, Mol C D, Miller J H, Lloyd S, Tainer J A. MutY catalytic core, mutant and bound adenine structures define specificity for DNA repair enzyme superfamily. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:1058–1064. doi: 10.1038/4168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labahn J, Scharer A, Long A, Ezaz-Nikpay K, Verdine G L, Ellenberger T E. Structural basis for the excision repair of alkylation-damaged DNA. Cell. 1996;86:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leatherbarrow R J. Enzfitter: a non-linear regression analysis program for IBM PC. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publisher BV; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Wright P M, Lu A-L. The C-terminal domain of MutY glycosylase determines the 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-guanine specificity and is crucial for mutation avoidance. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8448–8455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu A-L. Repair of A/G and A/8-oxoG mismatches by MutY adenine DNA glycosylase. In: Vaughan P, editor. DNA repair protocols, prokaryotic systems. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu A-L, Chang D-Y. A novel nucleotide excision repair for the conversion of an A/G mismatch to C/G base pair in E. coli. Cell. 1988;54:805–812. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu A-L, Chang D-Y. Repair of single base pair transversion mismatches of Escherichia coli in vitro: correction of certain A/G mismatch is independent of dam methylation and host mutHLS gene functions. Genetics. 1988;118:593–600. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.4.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu A-L, Fawcett W P. Characterization of the recombinant MutY homolog, an adenine DNA glycosylase, from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25098–25105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu A-L, Tsai-Wu J-J, Cillo J. DNA determinants and substrate specificities of Escherichia coli MutY. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23582–23588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu A-L, Yuen D S, Cillo J. Catalytic mechanism and DNA substrate recognition of Escherichia coli MutY protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24138–24143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makarova K S, Aravind L, Wolf Y I, Tatusov R L, Minton K W, Koonin E V, Daly M J. Genome of the extremely radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans viewed from the perspective of comparative genomics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:44–79. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.1.44-79.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maki H, Sekiguchi M. MutT protein specifically hydrolyses a potent mutagenic substrate for DNA synthesis. Nature. 1992;355:273–275. doi: 10.1038/355273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manuel R C, Czerwinski E W, Lloyd R S. Identification of the structural and functional domains of MutY, an Escherichia coli DNA mismatch repair enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16218–16226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manuel R C, Lloyd R S. Cloning, overexpression, and biochemical characterization of the catalytic domain of MutY. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11140–11152. doi: 10.1021/bi9709708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michaels M L, Cruz C, Grollman A P, Miller J H. Evidence that MutM and MutY combine to prevent mutations by an oxidatively damaged form of guanine in DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7022–7025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michaels M L, Miller J H. The GO system protects organisms from the mutagenic effect of the spontaneous lesion 8-hydroxyguanine (7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-guanine) J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6321–6325. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6321-6325.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michaels M L, Pham L, Nghiem Y, Cruz C, Miller J H. MutY, an adenine glycosylase active on G-A mispairs, has homology to endonuclease III. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3841–3845. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michaels M L, Tchou J, Grollman A P, Miller J H. A repair system for 8-oxo-7:8-dihydrodeoxyguanine (8-hydroxyguanine) Biochemistry. 1992;31:10964–10968. doi: 10.1021/bi00160a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minton K W. DNA repair in the extremely radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minton K W. Repair of ionizing-radiation damage in the radiation resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mutat Res. 1996;363:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moriya M. Single-stranded shuttle phagemid for mutagenesis studies in mammalian cells: 8-oxoguanine in DNA induces targeted G-C to T-A transversions in simian kidney cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1122–1126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moriya M, Ou C, Bodepudi V, Johnson F, Takeshita M, Grollman A P. Site-specific mutagenesis using a gapped duplex vector: a study of translesion synthesis past 8-oxodeoxyguanosine in Escherichia coli. Mutat Res. 1991;254:281–288. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90067-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nash H M, Bruner S D, Scharer O D, Kawate T, Addona T A, Spooner E, Lane W S, Verdine G L. Cloning of a yeast 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase reveals the existence of a base-excision DNA-repair protein superfamily. Curr Biol. 1996;6:968–980. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00641-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nash H M, Lu R, Lane W S, Verdine G L. The critical active-site amine of human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase, hOgg1: direct identification, ablation and chemical reconstitution. Chem Biol. 1997;4:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noll D M, Gogos A, Granek J A, Clarke N D. The C-terminal domain of the adenine-DNA glycosylase MutY confers specificity for 8-oxoguanine.adenine mispairs and may have evolved from MutT, an 8-oxo-dGTPase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6374–6579. doi: 10.1021/bi990335x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senturker S, Bauche C, Laval J, Dizdaroglu M. Substrate specificity of Deinococcus radiodurans Fpg protein. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9435–9439. doi: 10.1021/bi990680m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shibutani S, Takeshita M, Grollman A P. Insertion of specific bases during DNA synthesis past the oxidation-damaged base 8-oxodG. Nature. 1991;349:431–434. doi: 10.1038/349431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun B, Latham K A, Dodson M L, Lloyd R S. Studies on the catalytic mechanism of five DNA glycosylases: probing for enzyme-DNA imino intermediates. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19501–19508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tchou J, Grollman A P. Repair of DNA containing the oxidatively-damaged base 8-hydroxyguanine. Mutat Res. 1993;299:277–287. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(93)90104-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tchou J, Kasai H, Shibutani S, Chung M-H, Grollman A P, Nishimura S. 8-Oxoguanine (8-hydroxyguanine) DNA glycosylase and its substrate specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4690–4694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thayer M M, Ahern H, Xing D, Cunningham R P, Tainer J A. Novel DNA binding motifs in the DNA repair enzyme endonuclease III crystal structure. EMBO J. 1995;14:4108–4120. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai-Wu J-J, Liu H-F, Lu A-L. Escherichia coli MutY protein has both N-glycosylase and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease activities on A-C and A-G mispairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8779–8783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai-Wu J-J, Radicella J P, Lu A-L. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli micA gene required for A/G-specific mismatch repair: identity of MicA and MutY. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1902–1910. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1902-1910.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White O, Eisen J A, Heidelberg J F, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Dodson R J, Haft D H, Gwinn M L, Nelson W C, Richardson D L, Moffat K S, Qin H, Jiang L, Pamphile W, Crosby M, Shen M, Vamathevan J J, Lam P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Zalewski C, Makarova K S, Aravind L, Daly M J, Fraser C M, et al. Genome sequence of the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans R1. Science. 1999;286:1571–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams S D, David S S. Evidence that MutY is a monofunctional glycosylase capable of forming a covalent Schiff base intermediate with substrate DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5123–5133. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams S D, David S S. Formation of a Schiff base intermediate is not required for the adenine glycosylase activity of Escherichia coli MutY. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15417–15424. doi: 10.1021/bi992013z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wood M L, Dizdaroglu M, Gajewski E, Essigmann J M. Mechanistic studies of ionizing radiation and oxidative mutagenesis: genetic effects of single 8-hydroxyguanine (7-hydro-8-oxoguanine) residue inserted at a unique site in a viral genome. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7024–7032. doi: 10.1021/bi00482a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright P M, Yu J, Cillo J, Lu A-L. The active site of the Escherichia coli MutY DNA adenine glycosylase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29011–29018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu W, Shen J, Dunn C A, Desai S, Bessman M J. The Nudix hydrolases of Deinococcus radiodurans. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:286–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamagata Y, Kato M, Odawara K, Tokuno Y, Nakashima Y, Matsushima N, Yasumura K, Tomita K, Ihara K, Fujii Y, Nakabeppu Y, Sekiguchi M, Fujji S. Three-dimensional structure of a DNA repair enzyme, 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase II, from Escherichia coli. Cell. 1996;86:311–319. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zharkov D O, Grollman A P. MutY DNA glycosylase: base release and intermediate complex formation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12384–12394. doi: 10.1021/bi981066y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]