Abstract

Expression and recombination of the antigenic variation vlsE gene of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi were analyzed in the tick vector. To assess vlsE expression, Ixodes scapularis nymphs infected with the B. burgdorferi strain B31 were fed on mice for 48 or 96 h or to repletion and then crushed and acetone fixed either immediately thereafter (ticks collected at the two earlier time points) or 4 days after repletion. Unfed nymphs also were examined. At all of the time points investigated, spirochetes were able to bind a rabbit antibody raised against the conserved invariable region 6 of VlsE, as assessed by indirect immunofluorescence, but not preimmune serum from the same rabbit. This same antibody also bound to B31 spirochetes cultivated in vitro. Intensity of fluorescence appeared highest in cultured spirochetes, followed by spirochetes present in unfed ticks. Only a dim fluorescent signal was observed on spirochetes at the 48 and 96 h time points and at day 4 postrepletion. Expression of vlsE in vitro was affected by a rise in pH from 7.0 to 8.0 at 34°C. Hence, vlsE expression appears to be sensitive to environmental cues of the type found in the B. burgdorferi natural history. To assess vlsE recombination, nymphs were capillary fed the B. burgdorferi B31 clonal isolate 5A3. Ticks thus infected were either left to rest for 4 weeks (Group I) or fed to repletion on a mouse (Group II). The contents of each tick from both groups were cultured and 10 B. burgdorferi clones from the spirochetal isolate of each tick were obtained. The vlsE cassettes from several of these clones were amplified by PCR and sequenced. Regardless of whether the isolate was derived from Group I or Group II ticks, no changes were observed in the vlsE sequence. In contrast, vlsE cassettes amplified from B. burgdorferi clones derived from a mouse that was infected with B31-5A3 capillary-fed nymphs showed considerable recombination. It follows that vlsE recombination does not occur in the tick vector.

Antigenic variation of surface-exposed proteins has been identified as an important immune evasion mechanism in several pathogenic bacteria and parasites (2, 3, 18, 28, 29). Recently, it was shown that antigenic variation occurs in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi (31). The underlying mechanism entails segmental recombination within a plasmid-borne locus. This locus was named variable-major-protein (Vmp)-like sequence, or vls (31) and is situated on the linear plasmid lp28-1. The vls locus has been characterized extensively in the B31 strain of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (31–33). It consists of an expression site, vlsE, and a ca. 8-kb array of 15 silent cassettes that are located upstream (31). The B31 vlsE gene encodes a lipoprotein, VlsE, which has a predicted molecular mass of 34 kDa (31). The coding sequence of vlsE consists of a variable central cassette segment that is flanked by invariant 5′ and 3′ segments. During an experimental infection in mice, variable regions within the vlsE cassette undergo recombination with the vls silent cassettes via a gene conversion mechanism (32). This recombination leads to variation in the antigenic properties of VlsE (31). Thus far it has been determined that vlsE recombination occurs in the vertebrate host but not in spirochetes cultured in vitro (33). Interestingly, the VlsE protein is indeed expressed in vitro (12–14), thus indicating that vlsE transcription and recombination can occur independently. Each of the three pathogenic genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, namely B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii, is able to express VlsE in vitro (12–14).

The natural history of B. burgdorferi includes a vertebrate host, usually a rodent (the white-footed mouse Peromyscus leucopus in the United States), and an invertebrate host, a tick. Spirochetes cycle primarily between the rodent host and the larval and nymphal stages of ticks from the Ixodes ricinus species complex (in the United States, mostly Ixodes scapularis). Spirochetes, which are acquired by Ixodes larvae from infected rodents, survive larval molting and are then transmitted by the ensuing nymph to another vertebrate host. Infectivity of B. burgdorferi to I. scapularis larvae in the white-footed mouse is inversely dependent on the length of time mice have been infected, diminishing significantly 3 weeks after infection (15). In contrast, virtually all reservoir mice in nature have serum antibodies to several B. burgdorferi antigens, regardless of the intensity of transmission (4). Hence, it is possible that there are available in the wild large numbers of mice that harbor a nontransmissible, low-level infection, or no infection at all, yet still have residual circulating anti-B. burgdorferi antibody. When infected nymphs feed on such mice, it is conceivable that anti-VlsE antibodies taken in by the tick in a blood meal may impair spirochetal infectivity. Under these circumstances, antigenic variation, were it to occur within the tick, might offer a selective advantage to the spirochete. Expansion of the antigenic heterogeneity of a rapidly dividing spirochete population could facilitate its survival in the tick and subsequently in the vertebrate host. Alternatively, if VlsE were not expressed in the tick, anti-VlsE antibodies would be harmless to the spirochete.

In this study, we examined whether vlsE is expressed and undergoes sequence variation in infected ticks and whether vlsE recombination occurs in mice following tick inoculation. In addition, we assessed if expression of vlsE is affected in vitro by environmental cues that may influence B. burgdorferi lipoprotein expression in the tick, such as changes in pH and/or temperature. Expression of the VlsE protein in the tick was determined by immunofluorescence of tick smears before and at different time intervals after feeding on mice, as a way of assessing the effects of a blood meal on VlsE expression. Ticks were also infected with in vitro-cultured spirochetes of the clonal isolate B31-5A3 using the technique of capillary feeding. In this way, the arthropods were infected with a B. burgdorferi population that had not undergone vlsE recombination, as would occur in infection by feeding on mice. The vlsE sequences of individual spirochetal clones isolated from the capillary-inoculated ticks were compared to determine whether vlsE sequence changes occur in infected ticks, both before and after taking a blood meal. Furthermore, ticks infected with B31-5A3 by capillary feeding were allowed to feed on a mouse to assess whether vlsE sequence variation occurred in the mammalian host after tick inoculation, as had been shown following needle inoculation in previous studies (31, 32).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of ticks, capillary feeding, and isolation of spirochetes from ticks.

Larval I. scapularis ticks, a gift from Thomas Mather (University of Rhode Island, Kingston), were fed to repletion on an uninfected 8-week-old outbred mouse of the CD-1 strain (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.). Larvae were allowed to molt, and the resulting nymphs were used for capillary feeding. B. burgdorferi spirochetes from the clonal isolate B31-5A3 (passage 5) were grown in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK)-H medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) to stationary phase (≈108 spirochetes per ml) as described previously (27) and drawn up by capillary action into pulled borosilicate tubes with filament (Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, Calif.). The tubes were drawn into thin capillaries with a needle-pipette puller (model 700C; David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, Calif.). Uninfected nymphs were placed on their backs on double-sided tape. The tape itself was attached to the bottom of a petri dish. Capillary tubes were situated in a groove made in molding clay. Each tube was aligned with the tick such that the pulled tip could be fitted at a 30o angle from the tick's head to cover the hypostome, keeping the palpae free. Two or three ticks were placed on each petri dish, which was then placed in a humidifier tray and incubated for up to 1 h at 37oC. Successful feeding was indicated by the bloating of the tick and subsequent excretion of fluid. Capillary tubes were then removed, and ticks were gently lifted off the tape and maintained thereafter in a humidified environment at 22oC using a photoperiod of 16 h of light and 8 h of dark. Following capillary feeding, ticks were divided into two groups. Ticks of Group I (five nymphs) were maintained for 4 weeks before culturing. Ticks of Group II (four nymphs) were kept for 10 days and then fed on a CD-1 mouse until fully engorged. This group was kept for an additional 4 weeks postrepletion. Infectivity of capillary-fed B31-5A3 spirochetes was confirmed by the recovery of spirochetes from mouse ear punch biopsy cultures. Such spirochetes also were used to assess vlsE recombination within mice. Biopsies were collected 3 weeks postrepletion. To culture tick-borne spirochetes, ticks of both groups were surface sterilized by immersion in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min, followed by an equally long immersion in 70% ethanol. After the ticks were allowed to air dry, each one was placed individually into a sterile 1.7-ml conical microtube with 100 μl of BSK-H medium and crushed using a sterile molecular grinding pestle (Geno Technology, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.). After decanting the larger tick body parts, medium containing spirochetes was transferred to a 15-ml culture and spirochetes were allowed to proliferate. To control contamination, the medium antibiotic concentration was doubled, to a final concentration of 0.5 μg of amphotericin B per ml, 90.8 μg of rifampin per ml, and 0.39 mg of phosphomycin per ml (all from Sigma). Cells were grown to a concentration between 106 and 108 cells per ml and then cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until further testing.

PCR amplification and sequencing of amplified cassette fragments.

Frozen stocks of spirochetes isolated by cultivation from the five ticks of Group I and the four ticks of Group II were grown in BSK-H medium and allowed to reach stationary phase. Spirochetes of each isolate were then subsurface plated on BSK-H agarose as described previously (31). Ten well-separated colonies of each isolate were inoculated into BSK-H, grown to stationary phase, and frozen at −80°C following addition of glycerol to a final concentration of 15%. PCR amplification was performed using 5 μl of the frozen cultures as the source of template DNA and primers F4120 (5′AGTAGTACGACGGGGAAACCAGA) and R4066 (5′GAGTCTGCAGTTCGCAAAGT) (31). These primers hybridize, respectively, within the invariant 5′ and 3′ segments of vlsE, to sequences that are located 28 bases upstream and 6 bases downstream from the 17-bp repeats that confine the vlsE cassette region in the B31 clone 5A3 (31). Amplification was carried out for 35 cycles with initial template denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, and then denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, primer template annealing at 52°C for 45 s, and primer extension at 72°C for 1 min. PCR was also performed using a second set of specific primers (4598, 5′ TTC TGA TGG CAC TGA GCA AAC CA 3′, and 4599, 5′ AAC CCT TTA CAC TTT CTT CGA TTG CGC T 3′) corresponding to a region within the BBF01 (erpD) gene of lp28-1 (19). The resulting PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide following standard procedure (23). Identity of amplicons was confirmed by Southern hybridization with a vlsE-specific probe (corresponding to the insert sequence of DNA clone pJRZ53 (31) and processed for chemiluminescent detection using the Gene Images CDP-Star kit as described by the manufacturer (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.). PCR products were prepared for sequencing using the PCR Kleen-up kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) and then concentrated and desalted in a Microcon-100 filter unit (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). Sequencing was performed at the University of Texas Microbiology and Molecular Genetics Core Facility using an ABI 377 automatic DNA sequencer.

Antibodies

Rabbit antibody to the invariable region (IR) 6 of VlsE from the IP90 strain of B. garinii was obtained as described previously (12). On Western blots, this antibody reacts with the VlsE from spirochetes of the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (including B31), B. garinii, and B. afzelii genospecies (14). Fluorescein-labeled goat antibody against rabbit immunoglobulin was obtained from Sigma and used in indirect fluorescent antibody labeling (IFA) experiments. Fluorescein-labeled anti-B. burgdorferi antibody was purchased from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories (Gaithersburg, Md.) and used in direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) labeling experiments.

Immunofluorescence.

Expression of VlsE in ticks was assessed in B31-infected I. scapularis nymphs that were either unfed or allowed to feed on mice for 48 or 96 h or to repletion. Ticks were crushed and prepared for immunofluorescence either immediately (48- and 96-h samples) or 4 days after repletion. The contents of each tick were equally distributed on three microscope slides. The tick smears were air dried on the slides, acetone fixed, and stored at −20°C until the slides were used. One of the three slides was used to confirm the presence of spirochetes within the tick by DFA tests with the anti-B. burgdorferi antibody. A second slide served as a negative control for IFA binding and was incubated with preimmune serum from the rabbit that was immunized with IR6. The third slide was incubated with rabbit anti-IR6 antiserum to assess expression of VlsE. Slides were incubated with 40 μl of a 1:10 dilution of the anti-B. burgdorferi antibody or a 1:50 dilution of rabbit preimmune or rabbit anti-IR6 serum for 30 min at 37°C. Following washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the IFA slides were incubated with the fluorescein-labeled anti-rabbit antibody at 1:150 for 30 min at 37°C. Slides were washed in PBS, dried, and examined under the fluorescence microscope. As a positive control for detection of VlsE by IFA testing with the anti-IR6 serum, spirochetes cultured in vitro were used. Spirochetes of the B31 strain were grown in BSK-H medium to stationary phase (108 cells/ml). A 0.5-ml volume of this culture was collected and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was washed twice with PBS and resuspended in 0.5 ml of the same buffer. An 8-μl volume of this suspension was transferred to a glass microscope slide, allowed to air dry, fixed with acetone, and stored at −20°C until the slides were used. IFA binding was performed on these slides as described above.

Analysis of VlsE expression in vitro.

B. burgdorferi B31 spirochetes (passage 5) were grown in BSK-H medium to a density of approximately 107 cells per ml, diluted with BSK-H medium to 5 × 105 cells per ml, and then incubated at 24°C for 1 week. These 24°C-adapted cultures were then used as a source to inoculate cultures adjusted to various temperatures and/or pH, as follows: (i) BSK-H at normal pH (7.5) and 24°C, (ii) BSK-H at pH 7.0 and 34°C, (iii) BSK-H at pH 8.0 and 34°C. The pH of the medium was adjusted either with HCl or NaOH solutions, and cultures were inoculated at an initial density of 5 × 105 cells per ml in 10-ml tubes filled up to the top and tightly capped. Upon reaching stationary phase, cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellets were washed with HEPES wash buffer (20 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]) and resuspended in 100 μl of wash buffer. Samples were normalized for cell mass as described previously (22), and Western blots were prepared also as described before (1, 9). Two Western blots were prepared, each with extracts from cells cultured under each of the three culture conditions. One of the blots was incubated with the antiflagellin monoclonal antibody H9724 (purchased from the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio), and the other was incubated with the rabbit anti-IR6 serum at appropriate dilutions. The blots were then developed with the ABC Vectastain kit as per the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) with appropriate secondary antibodies. Densitometric quantification of bands was performed as described previously (22).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The VlsE cassette region amino acid sequences of clonal isolates 2441 to 2445 (as shown in Fig. 4B) have been deposited with GenBank under accession numbers AAL06259 to AAL06263, respectively. The corresponding nucleotide sequences are provided under accession numbers AY043397 to AY043401. The sequences depicted in Fig. 4A are identical to those of B. burgdorferi B31-5A3 (GenBank accession no. U76405) and thus were not submitted to GenBank.

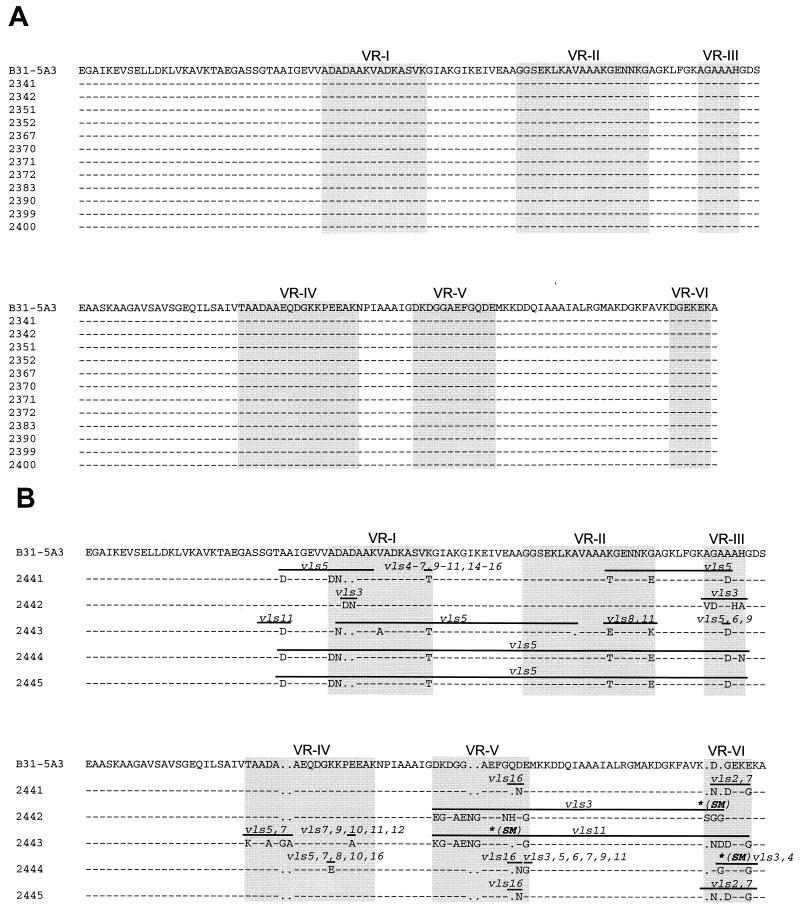

FIG. 4.

(A) Absence of predicted amino acid sequence differences in VlsE resulting from complete absence of vlsE recombination in ticks. (B) Predicted amino acid sequence differences in VlsE resulting from recombination following tick inoculation of a mouse with B. burgdorferi. The mouse was inoculated using ticks infected with B. burgdorferi B31-5A3 through capillary feeding, as outlined in Fig. 3. Alignment of the cassette region sequence of B31-5A3 VlsE (vls1) with those of five B. burgdorferi clones cultured from the mouse 3 weeks postinfection are shown. Dashes indicate sequence identity, whereas letters indicate conservative (lower case) and nonconservative (upper case) amino acid differences. Gaps are shown as periods. Probable recombinations are designated by the silent cassette sequences involved; lines indicate the predicted minimal range of the recombinations. In some cases, multiple silent cassettes could account for the recombination in a given region. Asterisks correspond to single nucleotide differences. These resulted in silent mutations (SM).

RESULTS

Expression of VlsE in the tick.

Ticks infected at the larval stage by feeding on a B. burgdorferi B31-infected mouse were allowed to molt to the nymphal stage. VlsE expression was assessed by immunofluorescence in the following: unfed nymphs, nymphs that had fed (on uninfected CD-1 mice) for either 48 or 96 h, and nymphs at 4 days postrepletion. Specimens from the midguts of four to eight ticks were examined separately at each time point. Changes in outer surface protein C (OspC) and OspA expression by B. burgdorferi in feeding nymphs have been reported to occur early, during the first 36 h of feeding (17). Hence, at the time points chosen to investigate VlsE expression, changes in lipoprotein expression are occurring apace. This time interval encompasses the periods of preferential expression of both OspC-type (48-h feeding) and OspA-type proteins (4 days postrepletion) (17).

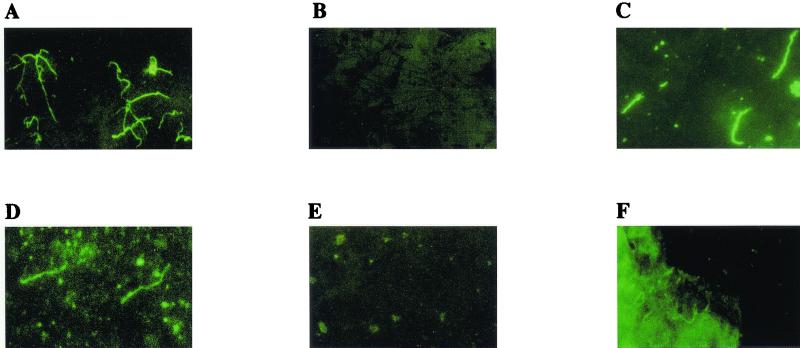

Spirochetes expressed VlsE when cultivated in vitro, as manifested by the ability of acetone-fixed cultured organisms to bind rabbit anti-IR6 antibody but not immunoglobulin from preimmune serum of this same rabbit (Fig. 1A and B, respectively). In flat ticks, VlsE was clearly detected with the anti-IR6 rabbit antiserum but not with the corresponding preimmune serum (Fig. 1D and E, respectively). After feeding commenced, VlsE was faintly detectable in spirochetes attached to tissue fragments of the tick, probably the midgut, in ticks that had fed for 48 h (Fig. 1F). In contrast, while spirochetes still could be faintly visualized with the anti-IR6 antibody at 96 h after initiation of feeding and at 4 days postrepletion, the organisms were no longer attached to midgut tissue (not shown). Spirochetes could be visualized in the ticks at all time points by DFA with the fluorescein-labeled anti-B. burgdorferi antibody (Fig. 1C, showing spirochetes in unfed ticks). Preimmune rabbit serum did not bind to tick-borne spirochetes at any time point.

FIG. 1.

VlsE expression in vitro and in the tick. B. burgdorferi B31 spirochetes cultured in vitro (A and B) or present in a tick squash (C, D, E, and F) were incubated with rabbit anti-IR6 antiserum and fluorescein-labeled anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibody (A, D, and F), with a preimmune bleed of the same rabbit (B and E) or with a fluorescein-labeled anti-B. burgdorferi antibody (C). Tick squashes were either from unfed ticks (C, D, and E) or from ticks that had fed for 48 h (F). All preparations were acetone fixed.

Changes in VlsE expression in vitro in response to changes in pH and/or temperature.

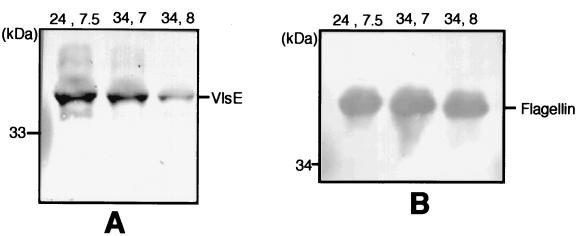

Expression of VlsE in vitro was sensitive to an increase in the pH of the medium. When spirochetes cultivated in normal BSK-H medium (pH 7.5) were grown at 24°C they expressed the VlsE protein at a level comparable to that of spirochetes cultivated at 34°C and pH 7.0. Thus, a decrease in the pH of the medium accompanied by an increase in temperature did not appear to influence VlsE expression. This can be seen in Fig. 2A, where a Western blot in which the same number of spirochetes was loaded in each lane shows similar intensities of the VlsE band, as visualized by the rabbit anti-IR6 antiserum. In contrast, VlsE expression was diminished fourfold, as estimated by densitometry, in spirochetes cultured at 34°C and pH 8.0 (Fig. 2A). Flagellin expression remained unaltered (Fig. 2B). This experiment was performed twice, with the same results.

FIG. 2.

Effects of temperature and/or pH on VlsE expression in vitro. Spirochetes (B31) were cultured in BSK-H medium at 24°C and pH 7.5 (24, 7.5), 34°C and pH 7.0 (34, 7), or 34°C and pH 8.0 (34, 8). Material solubilized from equal numbers of spirochetes was applied to each lane, electrophoresed, and blotted as described in Materials and Methods. Blots were developed either with a rabbit anti-IR6 antiserum (A) or with monoclonal antibody H9725 antiflagellin (B).

vlsE recombination in tick-borne spirochetes.

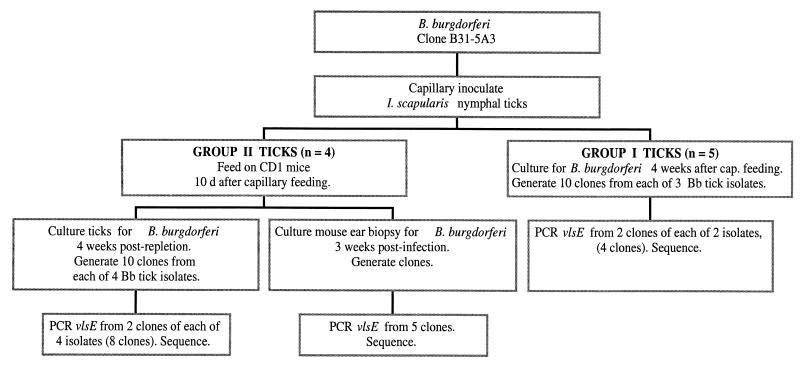

To assess whether vlsE recombination occurs in the arthropod environment, ticks were inoculated by capillary feeding with B. burgdorferi clone B31-5A3 cultured in vitro. This approach permitted the infection of ticks with borreliae that were of a single vlsE genotype, as vlsE variation has not been detected in organisms of this strain cultured in vitro (33). A flowchart depicting the relevant aspects of the experimental design is presented in Fig. 3. Ticks inoculated by capillary feeding either were cultured for spirochetes 4 weeks thereafter (Group I) or, 10 days after capillary feeding, were allowed to feed to repletion on an uninfected mouse and held for an additional 4 weeks prior to culture (Group II) (Fig. 3). Frozen stocks of spirochetes isolated by cultivation from the five ticks of Group I and the four ticks of Group II were grown in BSK-H medium and allowed to reach stationary phase. Three isolates of Group I and all of the isolates of Group II were amplified by PCR using primers F4120 and R4066 (see Materials and Methods). An amplicon of the predicted size (660 bp) was obtained from each isolate and was confirmed to be derived from the vlsE gene by Southern hybridization with a vlsE-specific probe (data not shown). Spirochetes of each of these isolates were subsurface plated, and 10 separate clones per isolate were obtained, expanded, and frozen. Clones from two isolates (1 and 5) of Group I and of all four of the isolates of Group II were assessed further.

FIG. 3.

Flowchart of experiments performed to assess vlsE recombination in ticks and in mice infected via tick bite.

PCR products obtained from two clones of each of the two selected isolates of Group I (clones 2341 and 2342 from isolate 1 and 2351 and 2352 from isolate 5) and two clones from each of the four isolates of Group II (clones 2367 and 2370 from isolate 1, 2371 and 2372 from isolate 2, 2383 and 2390 from isolate 3, and 2399 and 2400 from isolate 4) were sequenced as described in Materials and Methods. A comparison of the nucleotide sequence of each of the clones with that of the parent clonal isolate B31-5A3 revealed that vlsE recombination was not detectable in tick-borne spirochetes regardless of whether spirochetes were isolated from ticks before or after a blood meal. For brevity, only the aligned deduced amino acid sequences corresponding to the PCR-amplified vlsE regions are depicted in Fig. 4A. The amino acid (and nucleotide) sequences of the amplified fragments were identical to that of the parent strain, B31-5A3.

To verify that absence of vlsE recombination was not the consequence of failure of the spirochetes delivered by capillary feeding to actively divide in the blood-engorged ticks, three nymphs of a group of eight that had been capillary fed with the same B31-5A3 clonal isolate and passage used in the previous experiment were placed on a mouse and allowed to feed for 72 h. The five unfed and the three blood-fed ticks were crushed and acetone fixed, and spirochetes bound with the fluorescein-labeled anti-B. burgdorferi antibody were counted. Between 100 and 150 spirochetes were counted in each squash preparation. The average number of spirochetes per field prior to feeding was 0.51 ± 0.13 (mean ± standard error), whereas after a blood meal this number increased to 13.5 ± 3.3 spirochetes per field. This 26-fold expansion in the spirochetal density indicates that spirochetes within the capillary-infected ticks were actively dividing in the ticks during feeding.

In marked contrast with the absence of vlsE recombination found in tick-borne spirochetes, when spirochetes were isolated from ear punch biopsy cultures of mice that had been infected by the bite of B. burgdorferi B31-5A3-capillary-fed nymphs, the spirochetes showed numerous vlsE sequence differences (Fig. 4B). The clonal isolates were all different from each other as well as from the parental strain. This result is consistent with the occurrence of vlsE recombination in mice after tick-borne infection, as was found previously following needle inoculation (31–33).

Changes in vlsE sequences appear to correspond to gene conversion events in which segments of the vls silent cassettes recombine into the vlsE cassette region (31). These apparent recombination events were deduced by alignment of the variant amino acid and nucleotide sequences (marked 2441 through 2445) with those of the B31-5A3 vlsE sequence and the silent cassette sequences (data not shown). The minimal ranges of the silent cassette sequences involved in the predicted recombinations are indicated by lines in Fig. 4B. Most of these assignments were unambiguous, but some changes could be due to a recombination with one of several different silent cassettes (e.g., vls5, vls6, and vls9 in the VR-III region of clone 2443). Several gene conversion events were evident in other clones. In clone 2442, the sequence differences were consistent with three separate recombinations with the silent cassette vls3 (31). Each region matching vls3 was separated by a sequence that corresponded to the parental B31-5A3 sequence; thus, the sequence changes did not result from a single, large recombination event. In a few instances there were single nucleotide changes or reversions within the region of a silent cassette recombination; these are marked with asterisks and caused silent mutations (Fig. 4B). In one case (nucleotide 552 of the vlsE cassette sequence 2444, located in VR-VI), the nucleotide (C) did not correspond to any of the nucleotides encoded in vlsE1 or the vls silent cassettes. The surrounding region is consistent with a vls4 silent cassette segmental recombination; the T 224 C transition is silent, i.e., it does not result in a change at the amino acid level (both GGT and GGC encode glycine). This finding is consistent with the occurrence of a point mutation rather than a recombination at this location.

lp28-1 is not required for B. burgdorferi survival in ticks.

In the course of characterizing the B. burgdorferi clones isolated from infected ticks, it was found that many of these lacked lp28-1, the linear plasmid that contains the vls locus. In cultures obtained from two Group I and four Group II ticks, the numbers of lp28-1-positive clones ranged from 2 of 10 to 10 of 10, with the total being 32 of 60. A retrospective analysis of the original B31-5A3 stock indicated that 20 of 20 clones contained lp28-1, whereas the subsequent passage used for tick inoculation yielded a detectable vlsE PCR product in only 17 of 20 clones. The presence or absence of lp28-1 was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization using a vls sequence probe and also by PCR amplification of a second region within the gene BBF01 (erpD) at the other end of the plasmid (19). The results of each of these analyses corresponded exactly, indicating that lp28-1 was indeed absent from a portion of the tick- and in vitro culture-derived clones (data not shown). Thus, lp28-1 was apparently lost from some clones during the two to three intervening in vitro passages; rapid loss of lp28-1 and other B. burgdorferi plasmids had been noted previously (21, 33). The fact that many of the B. burgdorferi clones recovered from infected ticks lacked lp28-1 indicates that this plasmid is not required for survival of B. burgdorferi during the tick phase of its life cycle. In contrast, all clones obtained from the mouse infected by the Group II ticks contained lp28-1. This observation is consistent with previous results indicating that this plasmid is required for optimal survival and multiplication of B. burgdorferi in the mammalian environment (10, 11, 16, 21, 33).

DISCUSSION

We have analyzed whether the VlsE protein is expressed by B. burgdorferi within I. scapularis nymphs. VlsE expression was examined in the unfed nymph, the feeding nymph at 48 h after initiation of feeding, when spirochetal transmission is occurring (20), at 96 h, the time of repletion, and 4 days postrepletion. VlsE expression, as evidenced by IFA labeling with the anti-IR6 antibody, was detectable at all time points, albeit with markedly different fluorescence intensities. Fluorescence was most intense in spirochetes from unfed nymphs. At the 48 h time point, spirochetes were found closely attached to portions of tissue. We surmised this tissue to be part of the tick midgut. The fluorescence intensity was low but still distinguishable from that of organisms incubated with the preimmune rabbit serum. At the 96 h time point and at 4-days postrepletion, spirochetes were no longer attached to tissue fragments but the fluorescence intensity due to binding of anti-IR6 antibody also was lower than in unfed ticks. Thus, it is possible that the expression of VlsE is down-regulated at the initiation of tick feeding, perhaps in a manner similar to that of OspA (5, 7, 17, 24–26). In contrast with the OspA expression pattern, however, the VlsE protein is expressed in vivo immediately after infection (12, 13).

Recently, Yang et al. (30) found that a decrease in pH, in conjunction with increases in temperature and cell density, acted interdependently on the up-regulation of ospC expression and the down-regulation of ospA expression in vitro, in a manner that modeled the tick midgut environment during feeding (30). Other genes also were found to be regulated in a reciprocal fashion. Such genes were either ospC-like, e.g., ospF, mlp-8, and rpoS, or ospA-like (lp6.6 and p22). From our results, and borrowing from the nomenclature of Yang et al., it appears that vlsE is neither ospA- nor ospC-like. Since the VlsE lipoprotein was expressed in vitro at 24°C, or at 34°C and pH 8.0, it is not OspC-like. The OspC lipoprotein is not expressed at 23°C at any pH or at 37°C and pH 8.0, whereas it is expressed at the higher temperature at pH 6.8 and 7.5 (30). VlsE also is not OspA-like, in that OspA is expressed at lower levels at 37°C and pH 6.8 and increases its expression level as the pH rises to 7.5 and 8.0 (30), whereas VlsE decreased its expression level at 34°C as the pH of the medium changed from 7.0 to 8.0. VlsE also does not appear to be P21-like, for this protein is expressed neither in the tick nor in vitro but only in the mammalian host (6). In our hands VlsE was expressed in vitro, in the tick, and in the mammalian host (12, 13, 31). Its level of expression, however, appears to be susceptible to environmental cues of the type found in the spirochetal life cycle.

Other proteins involved in antigenic variation, such as the variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) of African trypanosomes, cease to be expressed when trypanosomes are taken up by the vector tsetse fly and enter the so-called procyclic stage (8). Procyclic trypanosomes are not coated with VSG. Instead they express a new surface coat composed of the protein procyclin (8). Expression of VSG is reinitiated only during differentiation to the metacyclic stage in the salivary glands of the tsetse fly. Metacyclic trypanosomes are infective to mammals. Their newly acquired VSG coat is thought to be essential for parasite survival and proliferation following infection (8). We did not specifically assess expression of VlsE in the tick salivary glands, but considering that this lipoprotein is expressed in the tick midgut and early after infection of the mammalian host, it is likely that its expression is not interrupted during the passage through the salivary glands. The pattern of expression of VlsE by B. burgdorferi is similar to that of Vmp, the antigenic variation protein of the relapsing-fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii: as with VlsE, Vmp is expressed both in the mammalian host and in the vector tick (25).

We found no evidence of vlsE recombination, either in flat nymphs that were capillary fed with spirochetes and then allowed to rest for 4 weeks or in capillary-infected, blood-fed ticks at 4 weeks postrepletion. This result is in stark contrast with the vlsE recombination we observed in mice at 3 weeks postinfection. Since the same clonal isolate of B31 was used for both experiments, our result indicates that recombination is either actively inhibited by as yet unknown tick-derived factors or elicited by vertebrate-host factors that are present neither in the unfed nor in the blood-fed tick. B. burgdorferi antigenic variation had been previously observed in mice that were experimentally infected via needle inoculation (31, 33). Our result proves that this phenomenon also occurs in mice that were inoculated with B. burgdorferi via tick bite and underscores the already paradigmatic notion that antigenic variation of B. burgdorferi occurs in nature.

In a recent paper, Ohnishi et al. presented the results of an analysis of vlsE recombination in ticks (17). Their experimental design differed substantially from the one we employed herein. They isolated DNA from B. burgdorferi-infected nymphal ticks that were either unfed or fed on mice for 48 h. The nymphs had been infected at the larval stage by allowing larvae to feed on mice at 4 weeks after needle inoculation with a clonal isolate of B. burgdorferi B31 (19). Four weeks is ample time for vlsE recombination to occur in mice (33). Hence, the larvae, and thereafter the nymphs, were infected with spirochetes that must have borne vlsE genes of diverse sequence. The cassette region of vlsE was PCR amplified using as template the DNA isolated from the unfed and fed nymphs, and the vlsE amplicons were inserted into an appropriate Escherichia coli plasmid vector (17). After transformation, vlsE inserts of 30 E. coli clones derived from unfed-tick DNA and 24 clones from 48-h-fed-tick DNA were analyzed by restriction fragment length polymorphism. For this purpose the inserts were digested with the restriction endonucleases AluI and MboI (17). Only 2 of the 30 clones from unfed ticks had patterns that differed from those of the parental strain. In contrast, the 24 clones derived from feeding ticks had 13 different restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns, all of which were different from that of the parental strain (17). The authors offer two interpretations of this result. Their preferred one is that the increased vlsE sequence diversity of the clones derived from fed ticks is due to VlsE recombination that occurs postfeeding. The alternative explanation they suggested is that, as the spirochetal population was expanded in the feeding tick, spirochetal subpopulations bearing preexisting variant vlsE became preferentially more numerous (17). In view of our results, we believe the latter to be the correct explanation.

The recombination mechanism underlying VlsE antigenic variation, as well as the expression of this protein, seems sensitive to environmental conditions. When spirochetes are cultured in vitro or are present in the tick, VlsE is expressed but no vlsE recombination occurs (31). In the mammalian host both recombination and expression take place (33). If, as we posited in the introduction, an array of anti-VlsE antibodies coexists with tick-borne spirochetes during the life cycle of B. burgdorferi in the wild, its possible deleterious effect upon the spirochete is not offset by absence of VlsE expression or presence of vlsE recombination within the tick. Perhaps the initial antigenic diversity of the spirochetal population in the unfed tick is sufficient to allow transmission of selected variants to occur, despite the presence of anti-VlsE antibodies in the mammalian host.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH-NCRR grant RR00164 (M.T.P.), NIH-NIAID grant AI37277 (S.J.N.) and Texas Advanced Technology Program grant 011618-0236-1999 (S.J.N.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aydintug M K, Gu Y, Philipp M T. Borrelia burgdorferi antigens that are targeted by antibody-dependent, complement-mediated killing in the rhesus monkey. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4929–4937. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4929-4937.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barstad P A, Coligan J E, Raum M G, Barbour A G. Variable major proteins of Borrelia hermsii, epitope mapping and partial sequence analysis of CNBr peptides. J Exp Med. 1985;161:1302–1314. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.6.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borst P. Molecular genetics of antigenic variation. Immunol Today. 1991;12:A29–A33. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(05)80009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunet L R, Sellitto C, Spielman A, Telford S R., III Antibody response of the mouse reservoir of Borrelia burgdorferi in nature. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3030–3036. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3030-3036.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman J L, Gebbia J A, Piesman J, Degen J L, Bugge T H, Benach J L. Plasminogen is required for efficient dissemination of B. burgdorferi in ticks and for enhancement of spirochetemia in mice. Cell. 1997;89:1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das S, Barthold S W, Giles S S, Montgomery R R, Telford III S R, Fikrig E. Temporal pattern of Borrelia burgdorferi p21 expression in ticks and the mammalian host. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:987–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI119264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fingerle V, Liegl G, Munderloh U, Wilske B. Expression of outer surface proteins A and C of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ricinus ticks removed from humans. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1998;187:121–126. doi: 10.1007/s004300050083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham S V, Wymer B, Barry J D. Activity of a trypanosome metacyclic variant surface glycoprotein gene promoter is dependent upon life cycle stage and chromosomal context. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1137–1146. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Indest K J, Ramamoorthy R, Sole M, Gilmore R D, Johnson B J, Philipp M T. Cell-density-dependent expression of Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins in vitro. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1165–1171. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1165-1171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyer R, Hardham J M, Wormser G P, Schwartz I, Norris S J. Conservation and heterogeneity of vlsE among human and tick isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1714–1718. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1714-1718.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labandeira-Rey M, Skare J T. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with loss of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect Immun. 2001;69:446–455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.446-455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang F T, Alvarez A L, Gu Y, Nowling J M, Ramamoorthy R, Philipp M T. An immunodominant conserved region within the variable domain of VlsE, the variable surface antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 1999;163:5566–5573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang F T, Steere A C, Marques A R, Johnson B J B, Miller J M, Philipp M T. Sensitive and specific serodiagnosis of Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a peptide based on an immunodominant conserved region of Borrelia burgdorferi VlsE. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3990–3996. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3990-3996.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang F T, Bowers L C, Philipp M T. The C-terminal invariable domain of VlsE is immunodominant but its antigenicity is scarcely conserved among strains of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3224–3231. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3224-3231.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindsay L R, Barker I K, Surgeoner G A, McEwen S A, Campbell G D. Duration of Borrelia burgdorferi infectivity in white-footed mice for the tick vector Ixodes scapularis under laboratory and field conditions in Ontario. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33:766–775. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-33.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDowell J V, Sung S Y, Labandeira-Rey M, Skare J T, Marconi R T. Analysis of mechanisms associated with loss of infectivity of clonal populations of Borrelia burgdorferi B31MI. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3670–3677. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3670-3677.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohnishi J, Piesman J, de Silva A M. Antigenic and genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi populations transmitted by ticks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:670–675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer G H, Brown W C, Rurangirwa F R. Antigenic variation in the persistence and transmission of the ehrlichia Anaplasma marginale. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piesman J. Standard system for infecting ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) with the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Med Entomol. 1993;30:199–203. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/30.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piesman J, Oliver J R, Sinsky R J. Growth kinetics of the Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi) in vector ticks (Ixodes dammini) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:352–357. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purser J E, Norris S J. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13865–13870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramamoorthy R, Philipp M T. Differential expression of Borrelia burgdorferi proteins during growth in vitro. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5119–5124. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5119-5124.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwan T G, Piesman J, Golde W T, Dolan M C, Rosa P A. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2909–2913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwan T G, Hinnebusch B J. Bloodstream- versus tick-associated variants of a relapsing fever bacterium. Science. 1998;280:1938–1940. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwan T G, Piesman J. Temporal changes in outer surface proteins A and C of the Lyme disease-associated spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, during the chain of infection in ticks and mice. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:382–388. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.382-388.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solé M, Bantar C, Indest K, Gu Y, Ramamoorthy R, Coughlin R, Philipp M T. Borrelia burgdorferi escape mutants that survive in the presence of antiserum to the OspA vaccine are killed when complement is also present. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2540–2546. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2540-2546.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoenner H G, Dodd T, Larsen C. Antigenic variation of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1297–1311. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van der Ploeg L H T, Gottesdiener K, Lee M G S. Antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. Trends Genet. 1992;8:452–457. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang X, Goldberg M S, Popova T G, Schoeler G B, Wikel S K, Hagman K E, Norgard M V. Interdependence of environmental factors influencing reciprocal patterns of gene expression in virulent Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1470–1479. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J R, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris S J. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J R, Norris S J. Genetic variation of the Borrelia burgdorferi gene vlsE involves cassette-specific, segmental gene conversion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3698–3704. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3698-3704.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J R, Norris S J. Kinetics and in vivo induction of genetic variation of vlsE in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3689–3697. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3689-3697.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]