Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of vericiguat in patients with heart failure (HF).

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive literature review of the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases up to 14 December 2022 for studies comparing vericiguat with placebo in patients with HF. Clinical data were extracted and cardiovascular deaths, adverse effects, and HF-related hospitalization were analyzed using Review Manager software (version 5.3), after quality assessment of the enrolled studies.

Results

Four studies (6705 patients) were included in this meta-analysis. There were no significant differences in the basic characteristics of the included studies. There was no significant difference in adverse effects between the vericiguat group and placebo group, and no significant differences between the groups in terms of cardiovascular death and HF hospitalization.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis indicated that vericiguat was not an effective drug for HF; however, more clinical trials are required to verify its efficacy.

Keywords: Vericiguat, heart failure, soluble guanylate cyclase, ejection fraction, adverse effect, hospitalization

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome and an advanced stage of various heart diseases, characterized by dyspnea, fatigue, and fluid retention, including pulmonary congestion and peripheral edema.1 Current guidelines divide HF into three categories with reduced ejection fraction (EF, HFrEF), intermediate EF (HFmEF), and preserved EF (HFpEF), respectively.2 There is still no satisfactory treatment for HF, but many drugs, including newly developed drugs such as soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulators, have been applied in recent years.

The nitric oxide (NO)–sGC–cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway is closely related to cardiovascular disease.3 Endothelial cells produce endogenous NO under the action of endothelial-derived NO synthase.4 The combination of NO and sGC promotes cGMP production from guanosine triphosphate (GTP).5 Increasing NO levels, activating sGC, and inhibiting GTP degradation are thus three possible ways of improving heart function, leading to the development of sGC activators and stimulators. The first accepted sGC stimulator was riociguat, which was later replaced by vericiguat, as a newly developed sGC activator approved for HFpEF in 2021.6 Vericiguat is characterized by a long half-life and high oral bioavailability in animal models.7

Although several clinical trials of vericiguat for HF have been carried out during the past decade, including VISOR, VENICE, and the phase II and III clinical trials VITALITY, VICTOR, SOCRATES, and VICTORIA, the effect of vericiguat on HF is still not fully understood.8,9 We therefore conducted a meta-analysis to study the efficacy and safety of vericiguat in HF, with the aim of providing information to help clinical decision-making.

Methods

The present study was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and the meta-analysis was registered in INPLASY (ID: INPLASY2021120057). This was a non-clinical study and ethical approval was therefore not required.

Search strategies

We performed comprehensive literature searches of the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases up to 14 December 2022, using the keywords heart failure, vericiguat, and their Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms, according to the different database instructions. The full search strategy in PubMed was as follows: (“Heart Failure”[MeSH Terms] OR (“Heart Failure”[Title/Abstract] OR “cardiac failure”[Title/Abstract] OR “heart decompensation”[Title/Abstract] OR “decompensation heart”[Title/Abstract] OR “heart failure right sided”[Title/Abstract] OR “heart failure right sided”[Title/Abstract] OR “right sided heart failure”[Title/Abstract] OR “right sided heart failure”[Title/Abstract] OR “myocardial failure”[Title/Abstract] OR “congestive heart failure”[Title/Abstract] OR “heart failure congestive”[Title/Abstract] OR “heart failure left sided”[Title/Abstract] OR “heart failure left sided”[Title/Abstract] OR “left sided heart failure”[Title/Abstract] OR “left sided heart failure”[Title/Abstract])) AND (“vericiguat”[Supplementary Concept] OR (“vericiguat”[Title/Abstract] OR “verquvo”[Title/Abstract] OR “bay 1021189”[Title/Abstract])).

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies met the following criteria: 1) inclusion of patients diagnosed with HF; 2) inclusion of at least two groups, including placebo and vericiguat (irrespective of dose); 3) randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT); and 4) display of data in English.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was cardiovascular mortality. Secondary outcomes were all-cause adverse effects and HF hospitalization.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (JM and BL) independently screened the titles and abstracts (and occasionally the full text) of each paper to identify studies that met the criteria. The basic data, including country, population, sample size, age, heart function, duration, interventions, and relevant outcomes, were extracted from each included study (Table 1). Data extraction was performed by two authors (JM and BL) and any disagreements between the two authors were resolved by a third author (SG).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Country | Follow-up | Patients in placebo vs. vericiguat groups | NYHA class | Ejection fraction | Dose of vericiguat (mg) | Cardiovascular-related deaths (event:total) |

HF hospitalizations (event:total) |

Adverse events (event:total) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| placebo | vericiguat | placebo | vericiguat | placebo | vericiguat | |||||||

| Gheorghiade et al.10 | Europe, North America, and Asia | 16 weeks | 92: 364 | II–IV | <45% | 1.5, 2.5, 5, 10 | 6:92 | 15:364 | 16:92 | 50:364 | 71:92 | 267:363 |

| Armstrong et al.11 | 42 countries | 12 months | 2515:2519 | I–IV | <45% | 10 | 225:2515 | 206:2519 | 747:2519 | 691:2515 | 2027:2519 | 2036:2515 |

| Pieske et al.12 | 25 countries | 12 weeks | 93:334 | II–IV | ≥45% | 1.5, 2.5, 5, 10 | 1:93 | 1:334 | NA | NA | 68:93 | 379:525 |

| Armstrong et al.13 | 21 countries | 24 weeks | 262: 526 | II–III | ≥45% | 10, 15 | 4:262 | 20:526 | NA | NA | 172:262 | 335:526 |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; HF, heart failure; NA, not available.

Evaluation of risk bias

The risk bias of the included studies was assessed by two authors (JM and BL) using Review Manager 5.3. The following seven aspects of the included studies were assessed as “high risk”, “unclear risk”, or “low risk”: domains of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager (version 5.3). Risk ratios (RR) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for primary and secondary outcomes. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I2 statistic. A fixed-effects model (Mantel–Haenszel) was used to analyze continuous variables if I2 <50%; otherwise, a random-effects model was adopted. Subgroup analyses were performed for patients with different EFs.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

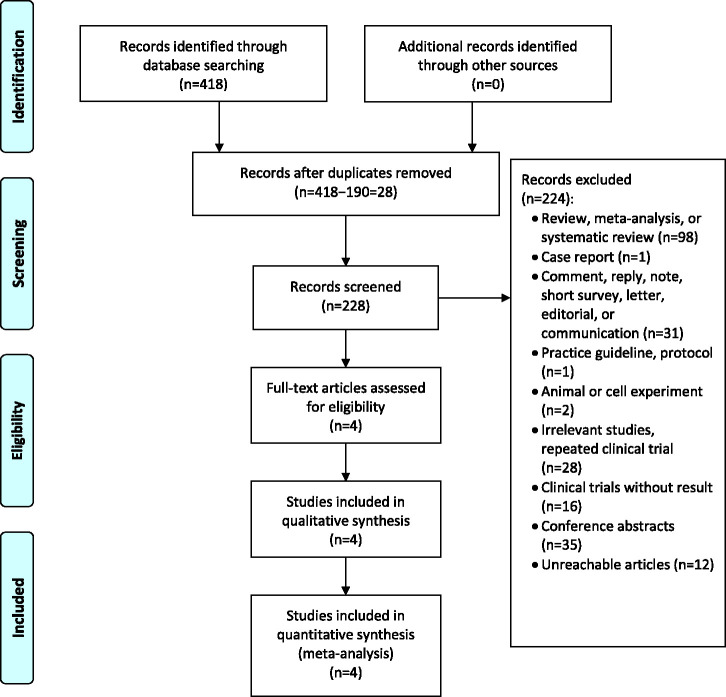

After searching the three databases, 418 articles were obtained (73 from Cochrane Library, 196 from Embase, and 149 from PubMed). Irrelevant articles were excluded after screening, the full texts of seven articles were reviewed, and four articles were finally included. The detailed process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the meta-analysis.

The RCTs included in this meta-analysis10–13 (Table 1) comprised 6705 patients who were randomized to either the placebo group (n = 2962) or vericiguat group (n = 3743). There were no significant differences in basic characteristics between the two groups. Different trials used different doses of vericiguat (2.5, 5, 10, 15, and 20 mg).

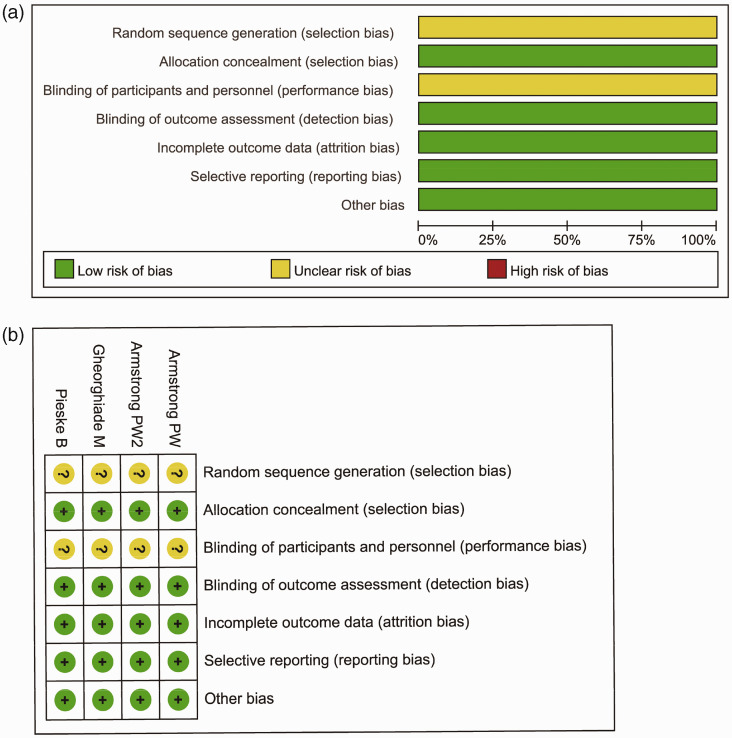

Risk of bias assessment and publication bias

We used the Cochrane Collaboration tool in Review Manager 5.3 to perform quality assessments. All four trials10–13 were conducted in more than 40 countries. None of the entries showed a high risk of bias. However, none of the four studies mentioned random sequence generation or blinding of participants and personnel during the trials (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias. (a) Review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies and (b) Review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

References: Armstrong PW11; Armstrong PW213; Gheorghiade M10; Pieske B.12

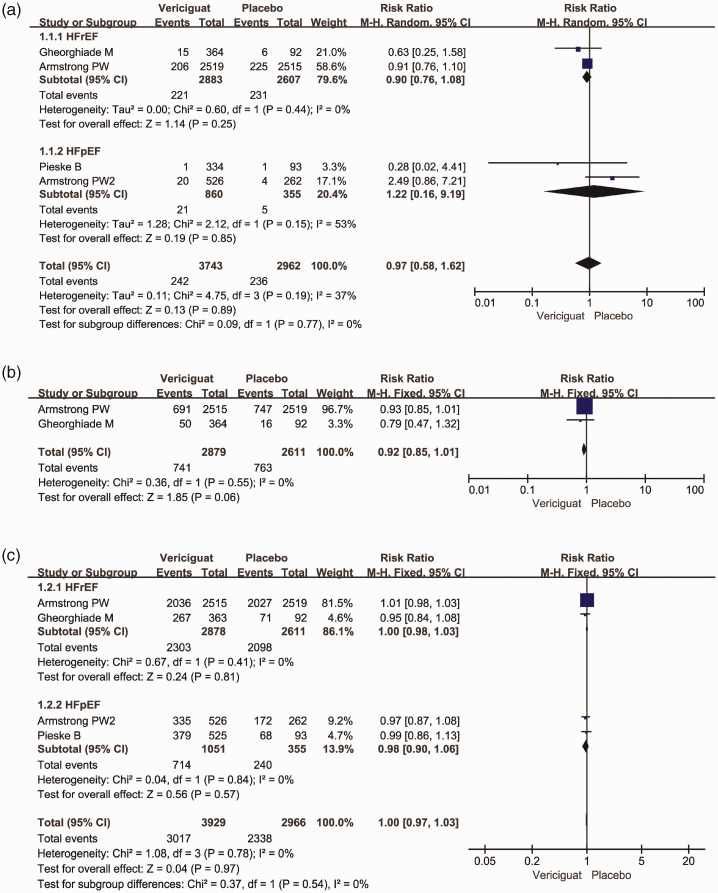

Primary and secondary outcomes

All included RCTs10–13 reported the cardiovascular death data (primary outcome). Two clinical trials focused on HFrEF and the others focused on HFpEF. There was no significant difference in cardiovascular death between the vericiguat and placebo groups (RR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.58–1.61, I2 = 37%). In addition, vericiguat did not reduce HF hospitalization in HFrEF and HFpEF patients (RR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.85–1.01, I2 = 0%), and there was no significant difference in adverse effects between the two groups (RR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.97–1.03, I2 = 0%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Outcomes in the included studies. Forest plot of vericiguat- and placebo-treated heart failure comparisons for (a) cardiovascular death, (b) heart failure hospitalization, and (c) adverse effects

References: Armstrong PW11; Armstrong PW213; Gheorghiade M10; Pieske B.12

M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

HF is a complex clinical syndrome caused by a variety of abnormal changes in cardiac structure and/or function.14 Many drugs, including angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists have been used to alleviate the manifestations of HF and improve heart function, especially EF.15,16 The effects of these drugs on HF however are still unsatisfactory,17 and new drugs, such as sGC stimulators, have accordingly been developed.

Vericiguat has been reported to reduce inflammation, fibrosis, and hypertrophy in the heart and to have beneficial effects on the blood vessels and kidneys.18 To date, four clinical trials of vericiguat, including VICTORIA, SOCRATES-PRESERVED, SOCRATES-REDUCED, and VITALITY-HFpEF, have been conducted to determine the appropriate dose and evaluate the effect of vericiguat in patients with HF;10–13 however, none of these trials has observed any positive effect of vericiguat, except regarding adverse effects, indicating that vericiguat is as safe as placebo. Vericiguat had no beneficial effect on cardiovascular death compared with placebo, indicating that it did not reverse heart function impairments. In the VICTORIA trial, vericiguat showed no advantage over placebo in improving the EF in patients with EF ≥40%, and patients in both groups experienced similar progression.11,19

A recent network meta-analysis focusing on therapies for HF indicated that vericiguat was less efficient than β-blockers for reducing all-cause mortality in patients with left ventricular EF ≥45%, and showed no difference compared with placebo.17 However, a systematic review revealed that sGC stimulators, including vericiguat, decreased the incidence of HF-related hospitalization and cardiovascular death with good tolerability and safety, but did not improve the 6-minute walking distance or N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels in HF patients.20

Among the completed clinical trials, the VICTORIA study is the most widely recognized. Before publication of the VICTORIA results, one researcher speculated that vericiguat would technically be a positive drug but may not have positive effects on hospitalization and mortality.21 Upon publication, the effect of vericiguat was not satisfied. Several network meta-analyses compared the effect of vericiguat and concluded that sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and β-blockers were more effective than vericiguat in patients with HF;17,22,23 however, other studies proposed that vericiguat was effective in reducing HF-related hospitalization and cardiovascular death.24

Pharmacological research showed that vericiguat could reduce coronary perfusion pressure but did not affect heart contractility during the drug screening period in rats,7 and that sGC was designed to improve cGMP levels in vascular smooth muscle cells, but not in cardiomyocytes;7 however, heart function is more dependent on cardiomyocytes than on smooth muscle cells. We therefore suspected that the unsatisfactory effects of vericiguat and other sGC stimulators in HF may be partially due to their focus on non-relevant target cells.

Our meta-analysis had several limitations. First, only four clinical trials were included. Second, several important endpoints such as N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, 6-minute walking distance, and quality of life measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire were not included in our meta-analysis, which may have prevented a fuller analysis of the effects of vericiguat on HF. In addition, some studies also recommended taking vericiguat in HF.25,26 Finally, due to the study design, studies reporting the effects of combinations of drugs in patients with HF were not included in the present meta-analysis. Notably however, recent studies of the combination of vericiguat with isosorbide mononitrate (VISOR study) and nitroglycerin (VENICE study) showed that vericiguat slightly lowered blood pressure, similar to the placebo group, indicating minimal adverse effects of vericiguat in HF. Follow-up clinical trials are needed to clarify the implications of the combined use of vericiguat.

Conclusion

Vericiguat is safe in patients with HF; however, its effect on HF (irrespective of EF) may be overestimated. More clinical trials are therefore urgently needed to confirm the effect of vericiguat in both HFrEF and HFpEF, and to assess its effect in combination with other drugs. More attention should also be paid to the theory behind the use of sGC stimulators for HF.

Research Data

Research Data for Efficacy and safety of vericiguat in heart failure: a meta-analysis by Jianhua Ma, Sheng Guo, Huan Jiang and Bo Li in Journal of International Medical Research

Footnotes

Author contributions: Jianhua Ma and Bo Li conceived the idea; Jianhua Ma and Sheng Guo performed the literature search, data collection, and data analysis; Jianhua Ma, Sheng Guo, Huan Jiang, and Bo Li wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest in preparing this article

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD: Bo Li https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7663-6051

References

- 1.Stretti L, Zippo D, Coats AJS, et al. A year in heart failure: an update of recent findings. ESC Heart Fail 2021; 8: 4370–4393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauersachs J, Soltani S. [Guidelines of the ESC 2021 on heart failure]. Herz 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gheorghiade M, Marti CN, Sabbah HN, et al. Soluble guanylate cyclase: a potential therapeutic target for heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2013; 18: 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh P, Vijayakumar S, Kalogeroupoulos A, et al. Multiple avenues of modulating the nitric oxide pathway in heart failure clinical trials. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2018; 15: 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandner P, Vakalopoulos A, Hahn MG, et al. Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators and their potential use: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2021; 31: 203–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markham A, Duggan S. Vericiguat: first approval. Drugs 2021; 81: 721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Follmann M, Ackerstaff J, Redlich G, et al. Discovery of the soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator vericiguat (BAY 1021189) for the treatment of chronic heart failure. J Med Chem 2017; 60: 5146–5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia J, Hui N, Tian L, et al. Development of vericiguat: The first soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator launched for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Biomed Pharmacother 2022; 149: 112894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kansakar S, Guragain A, Verma D, et al. Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators in heart failure. Cureus 2021; 13: e17781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gheorghiade M, Greene SJ, Butler J, et al. Effect of vericiguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator, on natriuretic peptide levels in patients with worsening chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: the SOCRATES-REDUCED randomized trial. JAMA 2015; 314: 2251–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong PW, Pieske B, Anstrom KJ, et al. Vericiguat in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1883–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pieske B, Maggioni AP, Lam CSP, et al. Vericiguat in patients with worsening chronic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: results of the SOluble guanylate Cyclase stimulatoR in heArT failurE patientS with PRESERVED EF (SOCRATES-PRESERVED) study. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 1119–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong PW, Lam CSP, Anstrom KJ, et al. Effect of vericiguat vs placebo on quality of life in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: the VITALITY-HFpEF randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 1512–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dzhioeva O, Belyavskiy E. Diagnosis and management of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF): current perspectives and recommendations. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2020; 16: 769–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho IJ, Kang SM. Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor in patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2021; 40: 555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xi Q, Chen Z, Li T, et al. Time to switch angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers to sacubitril/valsartan in patients with cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction. J Int Med Res 2022; 50: 3000605211067909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Y, Wu M, Liao B, et al. Comparison of pharmacological treatment effects on long-time outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol 2021; 12: 707777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lombardi CM, Cimino G, Pagnesi M, et al. Vericiguat for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Curr Cardiol Rep 2021; 23: 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voors AA, Mulder H, Reyes E, et al. Renal function and the effects of vericiguat in patients with worsening heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from the VICTORIA (Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with HFrEF) trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2021; 23: 1313–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Li Z, Li T, et al. Efficacy and safety of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmazie 2021; 76: 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coats AJS. Vericiguat for heart failure and the VICTORIA trial – the dog that didn't bark? Eur J Heart Fail 2020; 22: 576–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aimo A, Pateras K, Stamatelopoulos K, et al. Relative efficacy of sacubitril-valsartan, vericiguat, and SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2021; 35: 1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aimo A, Castiglione V, Vergaro G, et al. The place of vericiguat in the landscape of treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Heart Fail Rev 2022; 27: 1165–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran BA, Serag-Bolos ES, Fernandez J, et al. Vericiguat: the first soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator for reduction of cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization in patients with heart failure reduced ejection fraction. J Pharm Pract. Epub ahead of print 31 March 2022. DOI: 10.1177/08971900221087096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta R, Lin M, Maitz T, et al. Vericiguat: a novel soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator for use in patients with heart failure. Cardiol Rev 2022; 31: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell N, Kalabalik-Hoganson J, Frey K. Vericiguat: a novel oral soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator for the treatment of heart failure. Ann Pharmacother 2022; 56: 600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Research Data for Efficacy and safety of vericiguat in heart failure: a meta-analysis by Jianhua Ma, Sheng Guo, Huan Jiang and Bo Li in Journal of International Medical Research