Abstract

Early romantic relationships are salient to the development of healthy future relationships. Yet, little is known about the evolution of romantic relationships of emerging adults since most of the research has been conducted on married or well-established couples. The current study aims to examine how relationship satisfaction and negative communication evolve and are interrelated during emerging adulthood. Using age as a time metric, we conducted group-based dual trajectory modeling analyses on 1566 unmarried Canadian individuals (from 17 to 24 years old) in a relationship, who could either stay with the same partner or change partner over time. A four-group model for relationship satisfaction and a four-group model for negative communication were found. Dual analyses highlighted the high concordance between specific trajectories of both constructs. These findings demonstrate that relationship satisfaction and negative communication do not evolve in the same ways for everyone and provide useful insights to existing clinical interventions.

Keywords: emerging adulthood, romantic relationship, relationship satisfaction, dyadic communication, dual trajectories, longitudinal research

Emerging adulthood is the period between the late teens and mid-twenties characterized by identity exploration and independence from parents before committing to adult roles and responsibilities, such as spousal or parental roles (Fincham & Cui, 2010). This transitional period is crucial in the development of skills needed for future romantic relationships and deserves a special attention. Indeed, early romantic experiences have an influence on later relationship functioning, life satisfaction, and psychosocial adjustment (Gonzalez et al., 2021; Meier & Allen, 2009). In addition, romantic relationships in emerging adulthood can be different than those of committed and married couples. While many emerging adults are committed to their partner, others tend to have lower levels of engagement as an increasing number appear to want to “explore their options” before committing to a serious relationship (Rauer et al., 2013). Emerging adulthood is described by developmental theorists as a time of romantic exploration (Arnett, 2015; Fincham & Cui, 2010) and emerging adults differ considerably in their perceptions and experiences in romantic relationships (Roberson et al., 2017). Taken together, existing research has made it clear that emerging adults’ romantic relationships vary in stability and relational characteristics (Beckmeyer & Jamison, 2021; Manlove et al., 2014; Roberson et al., 2017). However, the way emerging adults’ romantic relationships evolve over time remains unclear. The current study will focus on how relationship satisfaction and negative communication, two important indicators of relationship functioning. It goes without saying that each partner must be able to solve conflicts efficiently, communicate their expectations and needs and to be heard by their partner in order to be fulfilled in their relationship (Courtain & Glowacz, 2018). Likewise, they must be satisfied with their roles and responsibilities within their relationship, as well as with the climate and dynamics of their relationship, to experience happiness and be more likely to stay together (Arriaga, 2001; Zhou et al., 2021). Indeed, emerging adults who experience stable levels of relationship satisfaction are less at risk of separating (Arriaga, 2001). The current study aims to better understand the trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication and how they are interrelated in emerging adults ranging from 17 to 24 years old. Relationship satisfaction and negative communication occupy a major role within most prominent theories and clinical models of romantic relationships (see Christensen et al., 2020; Johnson, 2020; McNulty et al., 2021).

Theoretical and Empirical Background

To the best of our knowledge, no study has previously looked at the evolution of negative communication as well as its joint evolution with relationship satisfaction during this transition period. However, it is possible to draw hypotheses from the existing research on emerging adults’ romantic relationships and from theoretical models and research on married couples’ relationship development. One study observed fluctuations in satisfaction over time in undergraduate college students involved in newly formed romantic relationships. In this study, the author measured the patterns of variability in satisfaction between two time points (i.e., steady or fluctuating) and did not look at the trajectories of relationship satisfaction across time points (e.g., increasing, decreasing, or stable). They found that higher levels of fluctuations in relationship satisfaction were associated with a higher chance of separation (Arriaga, 2001). At the cross-sectional level, a typology based on relationship satisfaction and negative interactions (among other relational dimensions) identified five types of romantic relationships in emerging adults (Beckmeyer & Jamison, 2021). The first one consisted of happily independent relationships (18.9%) that were characterized by moderate relationship length (M = 1.72 years), high relationship satisfaction and low negative interactions. The second type was named happily consolidated relationships (30.8%) and were also characterized by high relationship satisfaction and low negative interactions but had longer relationships on average (M = 3.41 years). The third type consisted of exploratory relationships (17.9%) and reflected low relationship satisfaction and high negative interactions with the shortest relationship length on average (M = 0.89 years). The fourth type was named stuck relationships (23.0%) and was characterized by low relationship satisfaction and high negative interactions but with the longest relationship length on average (M = 3.53 years). Finally, the fifth type consisted of high-intensity relationships (9.3%) and was described by high levels of relationship satisfaction and high levels of negative interactions (average relationship length of 2.14 years). These studies allowed us to expect that a number of different trajectories of satisfaction and negative communication may be found among emerging adults.

The work carried out with married adult couples can also be a relevant source of information for theorizing about these trajectories in emerging adults, whether they are with the same partner or not. Researchers have used different theoretical frameworks to explain the development of couple functioning across time, including relationship satisfaction and negative communication. However, whether these models apply to emerging adults in dating relationships necessitate further research. The oldest framework is the belief that relationship satisfaction follows a U-shaped curve (Anderson et al., 1983). This model suggests that levels of satisfaction and positive behaviors start high for the first years of marriage (for emerging adults, it could be the beginning of the relationship), then decline after the birth of the first child, and increase again when the last child leaves the family home. This model involved a decline after very specific events (i.e., birth of a child), but in emerging adults, other events could probably trigger similar declines in relationship satisfaction (e.g., one partner wanting to explore their options). Another popular framework is the gradual disillusionment model, also referred to as “the honeymoon is over, which is characterized by high levels of relationship satisfaction and low negative communication at the beginning of the relationship followed by a gradual decrease in couple satisfaction and increase in negative communication over time (VanLaningham et al., 2001; Williamson, 2021). Additionally, the enduring dynamics model suggests that partners’ individual differences dictate how they act in their relationship and are therefore more likely to follow the same pattern over time (Huston, 1994). With regard to emerging adults, it would be interesting to see whether they maintain the same patterns of negative communication and relationship satisfaction over time and even potentially despite a change of partner. An alternative theory of relationship development is the emergent distress model, which suggests that relationships deteriorate over time due to an increase in previously overlooked problems, such as conflicts and negative interactions (Bradbury et al., 1998). Thus, couples would exhibit high and stable negative communication over time, but with high relationship satisfaction at the beginning that gradually decreases over time. This model could be applied to emerging adults in dating relationships since initial high levels of negative communication that remain high over the years could contribute to the deterioration of relationship satisfaction, whether they change partner or not. Overall, these theoretical models all received empirical support among married couples (e.g., James, 2015; Lavner et al., 2020; Williamson, 2021), but not with emerging adults in dating relationships. It is therefore not possible to generalize existing empirical work to this population.

Duality of the Trajectories of Relationship Satisfaction and Negative Communication

Although the presented models of relationship development offer well-defined frameworks to better understand the individual trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication, the emergent distress model is the only one that offers clear predictions on how both trajectories may evolve together. Indeed, this model states that couples experience high relationship satisfaction and high negative communication at the beginning of their relationship until the accumulation of negative interactions begins to deteriorate relationship satisfaction over time. In addition to the emergent distress model, the typology of romantic relationships by Beckmeyer and Jamison (2021) presented above can also be used to make predictions on how trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication will be interrelated among a population of emerging adults. For instance, it could be expected to find that some emerging adults experience high satisfaction and low negative communication (happily independent and consolidated relationships), low relationship satisfaction and high negative communication (exploratory and stuck relationships), and high relationship satisfaction and high negative communication (high-intensity relationships). Moreover, the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA) model could also explain how negative communication influences relationship satisfaction across time. The VSA model is a popular and comprehensive framework suggesting that relationship satisfaction is impacted by each partner’s vulnerabilities or individual differences (V), their adaptive processes (A) which include the way they communicate together, and the stressors (S) they encounter (McNulty et al., 2021). In other words, this model proposes that partners’ own individual vulnerabilities and the life stressors they face would interact together and impact the way they communicate, which would in turn impact relationship satisfaction positively or negatively over time. In this model, it is assumed that negative communication and relationship satisfaction will evolve in parallel, meaning that when one is high, the other is low and vice versa. In addition, there is an abundance of cross-sectional studies showing an association between high relationship satisfaction and low negative communication and of longitudinal studies highlighting that better satisfaction at a given time is associated with lower negative communication at a later time point and vice versa (e.g., Lavner & Bradbury, 2010; Markman et al., 2010). One would therefore expect the trajectories to be associated in parallel, meaning that high relationship satisfaction will be associated with low negative communication, moderate satisfaction will be associated with moderate negative communication, and low relationship satisfaction will be associated with high negative communication.

So far, no studies have looked at the joint trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication over time, including with a population of emerging adults. However, two studies have looked at the interrelation between the trajectories of relationship satisfaction and the levels of conflict in married individuals of different ages and relationship lengths. Results supported the idea of a parallel association between relationship satisfaction and the levels of conflict (James, 2015; Kamp Dush & Taylor, 2012). For instance, the majority of James’ sample (2015) reported high happiness and low or moderate conflict over time and 20% of their sample reported low happiness and high or moderate conflict across time. However, Kamp Dush and Taylor (2012) found that part of their sample was either in the high happiness/high conflict group, the moderate happiness/high conflict group, or the moderate happiness/low conflict group. These associations suggest that the trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication may not always follow each other parallelly, meaning that one may feel satisfied while also communicating negatively and vice versa. These results highlight the importance of continuing the examination of joint trajectories to confirm existing models or highlight new models of relationship development.

Unique Challenges of Studying Emerging Adults’ Relationships

Emerging adults are in a period of identity exploration in which they could date a number of people to clarify what type of person they like and what they want or do not want in a relationship (Fincham & Cui, 2010). They can also be free from the responsibilities and obligations of the adult roles of committed partners or parents, which leaves an open world of relationship possibilities (Meier & Allen, 2009). Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood can be unstable since they tend to change partners frequently. In fact, over a third of emerging adults will experience a breakup over a 20-month period (Rhoades et al., 2011). It is thus essential to study emerging adults who remained with the same partner as well as those who changed partner over the years to increase findings generalization.

Cultural Context

In the recent years, researchers have become increasingly aware of the role of culture in romantic experiences. Previous studies have found that there are substantial cross-cultural differences in adolescents and emerging adults’ romantic experiences, notably in the frequency of romantic involvement and the quality of romantic relationships (Connolly et al., 2014; Marshall, 2008). The current study uses a sample of French Canadian emerging adults. The relational context in Canada, and more specifically the Province of Quebec, is similar to other Western societies (Western societies include European and related cultures in Canada, the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand), that is, intimacy varies widely among emerging adults, going from one-night-stands to committed long-term relationships. In Canada, approximately 60% of are in serious/committed relationships (NettingReynolds, 2018) and the same proportion (60%) was found among French Canadians ranging from 18 to 29 years old (Boucher Bégin et al., 2021). Keeping this context in mind, we expect to find variability in relationship satisfaction and negative communication among our sample of French Canadian emerging adults, akin to previous studies conducted on American emerging adults (Beckmeyer & Jamison, 2021).

Goals and Research Questions

The aim of the current study is to examine trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication and to determine whether they are interrelated among dating emerging adults from 17 to 24 years who either stayed with the same partner or changed partner over time. Given that we are interested in the period of emerging adulthood between the late teens and mid-twenties, age was the most appropriate time metric rather than the calendar year. Indeed, using the calendar year has been criticized for only informing how relationships evolve between arbitrary dates (Anderson et al., 2010). Using an exploratory approach, this study posed three research questions. First, how does relationship satisfaction evolve over time in dating emerging adults? Second, how does negative communication evolve over time in dating emerging adults? Third, how are the trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication paired together? Given that no one to our knowledge has examined these trajectories in a sample of emerging adults, we did not have specific hypotheses and conducted these analyses in an exploratory manner.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The final sample consisted of 1566 emerging adults ranging from 17 to 24 years old who were involved in a romantic relationship but not married. The present study is indeed part of a larger longitudinal research study that took place from 2004 to 2017. Participants were recruited on a volunteer basis from different high schools and colleges in an Eastern region of Canada. At Time 1 (T1), research assistants met the potential participants directly in their classrooms and gave them the questionnaire package in a prepaid envelope. They were instructed to mail the completed questionnaire package to the research team. Seven cohorts of participants were followed for 6 years, the first one beginning in May 2004 and ending in September 2010 and the last one beginning in May 2011 and ending in May 2017. This longitudinal study consisted of four-time waves, the time intervals between each time point were 34 months, 18 months, and 19 months. Participants received 5$ at each time point for their participation. This study was approved by the research ethics board of a Canadian university.

Two thousand seven hundred and fifty-four (2754) Canadian adolescents and emerging adults, who were either involved or not in a romantic relationship, participated at least once throughout the study. Among them, 972 participants were not involved in a romantic relationship at any time points and were therefore excluded from the present study. In addition, 68 couples participated in the study, therefore one member of each couple was randomly deleted (n = 68) to ensure the nonindependence of the data. In order to use age as a time metric rather than the calendar year, we created an “age” scale ranging from 13 to 26. In doing so, 26 participants were excluded from the analyses because they did not provide their age or date of birth. Age groups between 13 and 16 and between 25 and 27 years old were too small and thus were not included in the trajectory analyses. This led to the exclusion of 122 participants. Therefore, the final sample of the current study is 1566 participants ranging from 17 to 25 years old. Each age group had a minimum of 133 participants and the exact number of participants per age group is included in Table 1. A large percentage of our sample has changed partner between the beginning and the end of the study (99.7%). More details on sociodemographic characteristics of the final sample can be found in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Study Variables for Each Age Group.

| Study Variables | n | % | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship satisfaction | ||||||

| Age 17 | 544 | 34.7 | 17.09 | 3.05 | 2.00 | 21.00 |

| Age 18 | 478 | 30.5 | 17.15 | 2.92 | 5.00 | 21.00 |

| Age 19 | 367 | 23.4 | 16.88 | 3.16 | 5.00 | 21.00 |

| Age 20 | 286 | 18.2 | 16.89 | 2.79 | 8.00 | 21.00 |

| Age 21 | 267 | 17.1 | 16.80 | 3.21 | 4.00 | 21.00 |

| Age 22 | 221 | 14.1 | 17.13 | 2.98 | 4.00 | 21.00 |

| Age 23 | 185 | 11.8 | 16.91 | 2.63 | 7.00 | 21.00 |

| Age 24 | 133 | 8.5 | 17.14 | 2.73 | 7.00 | 21.00 |

| Negative communication | ||||||

| Age 17 | 544 | 34.7 | 15.10 | 8.70 | 5.00 | 40.00 |

| Age 18 | 478 | 30.5 | 14.86 | 8.44 | 5.00 | 45.00 |

| Age 19 | 367 | 23.4 | 16.57 | 8.53 | 5.00 | 38.00 |

| Age 20 | 286 | 18.2 | 16.40 | 8.50 | 5.00 | 41.00 |

| Age 21 | 267 | 17.1 | 16.63 | 8.48 | 5.00 | 40.00 |

| Age 22 | 221 | 14.1 | 15.65 | 8.66 | 5.00 | 38.00 |

| Age 23 | 185 | 11.8 | 16.85 | 8.94 | 5.00 | 37.00 |

| Age 24 | 133 | 8.5 | 15.58 | 7.89 | 5.00 | 33.00 |

Note. N = 1566.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Final Sample (N = 1566).

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | M | SD | Min | Max | % | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 75.0 | 1175 | ||||

| Male | 25.0 | 391 | ||||

| Age at T1 | 18.34 | 1.37 | 17.00 | 24.00 | ||

| Years of education | 11.85 | 1.38 | 6.00 | 19.00 | ||

| Same partner from T1 to T2 | 21.7 | 340 | ||||

| Same partner from T2 to T3 | 17.2 | 269 | ||||

| Same partner from T3 to T4 | 15.5 | 321 | ||||

| Same partner from T1 to T4 | 0.3 | 5 | ||||

| Same partner from T1 to T3 | 1.2 | 19 | ||||

| Same partner from T2 to T4 | 7.4 | 116 | ||||

| Relationship length at 17 (in Months) | 13.05 | 12.67 | 1.00 | 63.00 | ||

| Relationship length at 18 (in Months) | 12.79 | 11.83 | 2.00 | 54.00 | ||

| Relationship length at 19 (in Months) | 17.36 | 14.53 | .25 | 65.00 | ||

| Relationship length at 20 (in Months) | 19.21 | 15.26 | .75 | 60.00 | ||

| Relationship length at 21 (in Months) | 21.51 | 19.47 | 1.00 | 72.00 | ||

| Relationship length at 22 (in Months) | 25.63 | 17.57 | 2.00 | 60.00 | ||

| Relationship length at 23 (in Months) | 22.43 | 24.42 | 2.00 | 80.00 | ||

| Relationship length at 24 (in Months) | 29.33 | 27.74 | 4.00 | 102.00 |

Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire

This questionnaire was used to collect relevant social and demographic information (e.g., age, years of education) as well as relationship demographics (e.g., relationship status and length of relationship).

Relationship Satisfaction

The French version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale-4 items (DAS-4; Sabourin et al., 2005) was used to assess the degree of relationship satisfaction for individuals involved in a romantic relationship. Responses for items 1–3 were reported using a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (all the time) to 5 (never), and responses for Item 4 were scored with a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (extremely unhappy) to 6 (perfect). Items included “How often do you discuss or have you considered divorce, separation, or terminating your relationship” and “In general, do you think that things between you and your partner are going well?” Given its conceptual similarity with the construct of communication, we tested whether the item “I confide into my partner” was strongly correlated with negative communication. Although the correlation was statistically significant (r = −.20, p < .001), results showed that among all four items of the DAS-4, the item “I confide into my partner” was the least correlated with negative communication (r = −.43, p < .001 for item 1, r = −.37, p < .001 for item 2 and r = −.38, p < .001 for item 4). Thus, it was decided to keep the item “I confide into my partner” in the statistical analyses. Higher scores indicative of higher relationship satisfaction and the total score was used in the current study. Sabourin et al. (2005) reported a coefficient of .84. For the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were .78 at T1, .81 at T2, .77 at T3, and .78 at T4.

Negative Communication

The French version of the Communication Patterns Questionnaire – Short Form (CPQ-6; Lafontaine et al., 2021) was used to measure negative communication patterns in their relationship. This version is an abridged 6-item measure of the original CPQ (Christensen, 1987). Five items of negative communication are included in this version, including two items based on the demand/withdraw communication pattern, one item of critic/defense, and one item of mutual blame. One item of the CPQ-6 measures positive communication and was not included in the current study. Each item is rated on a 9-point scale, ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 9 (very likely). Higher scores are indicative of greater negative communication, and the total score was used in our analyses. Using the same sample at T1, Lafontaine et al. (2021) found good psychometric properties, including a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .81. For the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were .81 at T1, .82 at T3, .83 at T4, and .81 at T5.

Data Analysis Strategy

SPSS version 28.0 and SAS version 9.4. were used to perform analyses. Using PROC TRAJ, a SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories (Jones et al., 2001), we applied maximum likelihood estimations to handle missing values. Therefore, all participants who minimally participated at one time point were included in the analyses, regardless of their missing data. The maximum likelihood approach allows researchers to utilize all available data for parameter estimation, which has been found to be a superior method for dealing with a high number of missing values (Yuan et al., 2012). The joint trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication were examined using group-based dual trajectory modeling (GBDTM; Nagin, 2005). It is a person-centered approach that uses semiparametric mixture models to identify memberships to different groups and examine their longitudinal associations (Nagin & Odgers, 2010). There are no statistical analyses or well-established guidelines for determining sample sizes or analyses to assess power in GBTM (Frankfurt et al., 2016). However, studies with fewer than 500 participants have been found to often be underpowered, due to the division of the sample in smaller subgroups (Hensen et al., 2007).

Trajectories of negative communication and satisfaction were estimated using a censored normal distribution, which is appropriate for continuous scales that are censored to a minimum or a maximum (Jones & Nagin, 2007). A series of group-based trajectory models were fitted to determine the optimal trajectory models for relationship satisfaction and negative communication. The best number and shapes of the trajectories were determined based on the smallest Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value, parsimony and theoretical justification (Nagin, 2005; Zang & Max, 2020). Smaller BIC and AIC values indicate a better the fit of the model (Nagin, 2005). After identifying the optimal number of trajectory groups, the best fitting model was identified by re-estimating the models with different functional forms (i.e., zero-order, linear, quadratic, or cubic) for each trajectory group. Following the best practice guidelines, groups that included less than 3% of the sample were excluded (Nagin, 2005).

Dual trajectory analyses allow researchers to analyze the interrelations between the trajectories of two outcomes that are evolving simultaneously (Nagin & Odgers, 2010). Compared with analyses of single trajectories, dual trajectory analyses can provide information on the likelihood of following a trajectory on a first outcome given their membership in one of the trajectory groups on a second outcome. In the current study, three interrelations were assessed with estimated linkage probabilities: (a) probability of group membership in a trajectory of negative communication conditional on satisfaction, (b) probability of group membership in a trajectory of satisfaction conditional on negative communication, and (c) joint probabilities of group membership in both negative communication and satisfaction. Linkage probabilities range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher membership likelihood. A probability greater than .70 indicates acceptable classification (Frankfurt et al., 2016).

Profile analyses will also be conducted in order to examine how emerging adults’ sociodemographics will be distributed across the trajectories. Thus, we will examine differences in gender, relationship length, change of partner, and years of education across the final trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication. In order to examine how changing partner was distributed in each trajectory, we created three dummy variables, one representing those who have remained with the same partner over the years (no variability), one representing those who have changed partner one time only (some variability) and one variable representing those who have changed partner at least twice throughout the 6 years of the study (high variability). Relationship length was averaged by calculating the mean of each participant’s relationship length at T1, T2, T3 and T4. Chi-square test will be used for categorical variables (i.e, gender and change of partner) and one-way ANOVAs will be conducted for continuous variables (i.e., relationship length and years of education).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

An evaluation of missing data using a Little’s MCAR test was performed and confirmed that all values were missing completely at random, χ2(N = 1566) = 2132.56, p = .819. Within-wave missing data found that there were no more than 5% missing data. In order to examine whether excluded participants (participation at only one time) were different on the study variables than those included (participation at two time points or more), one-way ANOVAs across all study variables were conducted. Results showed that there were no significant differences between excluded and included participants. Thirty-seven univariate outliers across both variables on all time points were identified using standardized values and two multivariate outliers were identified using a test of Mahalanobis distance. All outliers were examined and it was decided to include them since they were legitimate cases from the intended population, following the recommendations given by Tabachnick and Fidell (2019) against data transformations. Normality was not evaluated since this type of analysis can accommodate for non-normal distributions (Nagin & Odgers, 2010).

Descriptive Analyses

Means and standard deviations of relationship satisfaction and negative communication for each age group are presented in Table 1. Linear multilevel modeling was used with SPSS 28.0 to examine whether there was a difference across the four time points (T1, T2, T3 and T4) in both study variables. Using maximum likelihood to handle missing data, results revealed no significant differences across time in relationship satisfaction (F (3, 1189.07) = .137, p = .938) or negative communication (F (3, 1195.09) = .1.700, p = .165). Mean comparisons between all sociodemographic variables and study variables for all ages were calculated using independent sample t-tests and one-way ANOVAs. There were no statistically significant differences in participants’ relationship satisfaction and negative communication according to their gender, years of education, and relationship status and all effect sizes were not meaningful (d < 0.2). In order to test the impact of the change of partner, a dichotomous variable was created for each age group (starting at 18 years old) to represent whether they were with the same partner since their previous participation or not. Mean comparisons using independent sample t-tests showed that participants at age 19 who changed partners reported higher relationship satisfaction communication (M = 16.94, SD = .2.60) than those who were still involved with the same partner (M = 16.12, SD = 4.37) since their last participation (t (85) = 35.227, p = .024, d = 0.27). Thus, whether they are with the same partner was added as a time-varying covariate in the trajectory analyses.

Main Statistical Analyses

Trajectories of Relationship Satisfaction

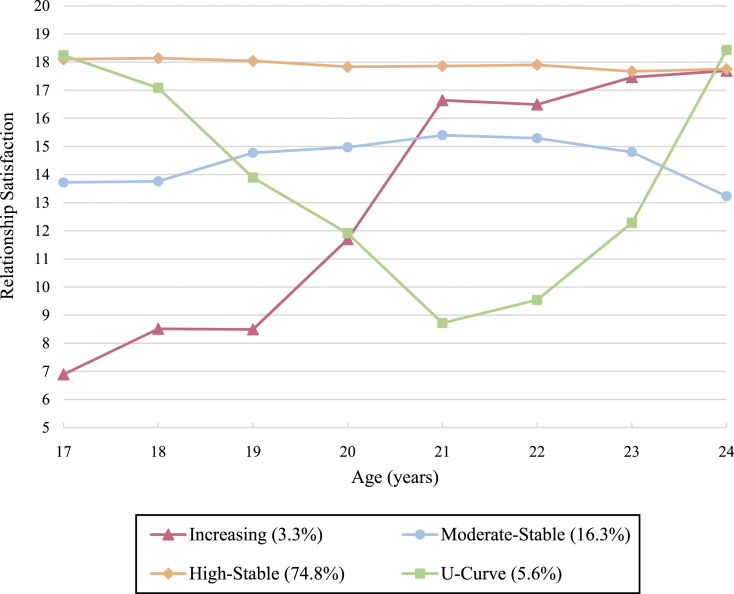

For relationship satisfaction, a four-group model was identified as best fitting the data (BIC = −366.96; see Table 3). Although the five and six-group models had smaller BIC and AIC values (see Table 3), the models were excluded because they contained groups with very small proportions of the observations (<2%). The trajectories of the four-group model of relationship satisfaction were obtained controlling for whether the participants changed partners or not (see Figure 1). The first trajectory is linear and represents an increase in relationship satisfaction across ages (increasing, n = 52, 3.3%). The second trajectory is also linear and represents a moderate and stable relationship satisfaction across all ages (moderate-stable, n = 255, 16.3%). The third linear trajectory and represents high and stable relationship satisfaction across all ages (high-stable, n = 1171, 74.8%). The fourth trajectory is quadratic (curvilinear) and represents a decrease in relationship satisfaction between 17 and 21 years old, followed by an increase around age 22 (U-Curve, n = 88, 5.6%).

Table 3.

Model Fit Statistics.

| Number of Groups | Negative Communication | Relationship Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | BIC | AIC | BIC | |

| 2 | −3016.48 | −3043.19 | −319.15 | −417.86 |

| 3 | −2985.63 | −3025.70 | −338.39 | −378.46 |

| 4 | −2957.21 | −3010.64 | −313.53 | −366.96 |

| 5 | −2962.21 | −3028.99 | −289.63 | −356.41 |

| 6 | −2938.16 | −3018.30 | −268.17 | −348.32 |

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criteria. BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of relationship satisfaction. Note. N = 1566.

Trajectories of Negative Communication

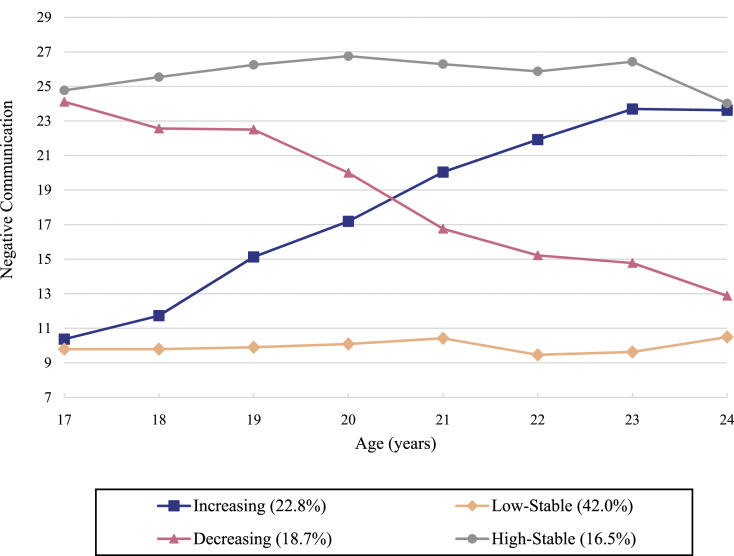

For negative communication, a four-group model of linear trajectories best fitted the data (BIC = −3010.64; see Table 3). Although the five and six-group models had smaller BIC and AIC values (see Table 3), the models were excluded because they contained groups with very small proportions of the observations (<2.5%). The trajectories of the four-group model of negative communication are all linear and are illustrated in Figure 2. The first trajectory represents participants who experienced an increase in negative communication across all ages (increasing, n = 357, 22.8%). The second trajectory represents participants who remained low on negative communication over time (low-stable, n = 658, 42.0%). The third trajectory consists of participants who experienced a decrease in negative communication between the ages of 17 and 24 years old (decreasing, n = 293, 18.7%). The fourth linear trajectory represents participants who reported high and stable negative communication across all ages (decreasing, n = 258, 16.5%).

Figure 2.

Trajectories of negative communication. Note. N = 1566.

Dual Trajectory Model: Joint Analyses

The joint analyses led to the same four-group model for relationship satisfaction and four-group model for negative communication found in the trajectories analyses described above. The probabilities of relationship satisfaction conditional on negative communication are presented in Table 4, part A (the probabilities in each row sum to 1.0). These conditional probabilities represent the likelihood of membership in one of the relationship satisfaction groups, given membership in one of the negative communication trajectories. For instance, there was a 92% likelihood that a youth in the low-stable group of negative communication would follow the high-stable trajectory of relationship satisfaction. In addition, a 73% chance that a youth would follow the moderate-stable trajectory of satisfaction if they were in the decreasing group of negative communication. There was also a 74% likelihood that a youth in the high-stable group of negative communication would follow the moderate-stable group of relationship satisfaction. No other probabilities were higher than .70, which is the threshold for an acceptable classification (Frankfurt et al., 2016). There was zero probability of following the increasing trajectory of relationship satisfaction if also on the increasing group of negative communication. There was also 0% chance of a youth in the high-stable group of negative communication to follow the high-stable trajectory of relationship satisfaction.

Table 4.

Conditional and Joint Probabilities of Negative Communication and Relationship Satisfaction.

| Negative Communication Trajectory | Relationship Satisfaction Trajectory | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Increasing (n = 52) | 2. Moderate-Stable (n = 255) | 3. High-Stable (n = 1171) | 4. U-Curve (n = 88) | |

| A) Probability of relationship satisfaction conditional on negative communication | ||||

| 1. Increasing (n = 357) | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.09 |

| 2. Low-stable (n = 658) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.92 | 0.02 |

| 3. Decreasing (n = 293) | 0.26 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| 4. High-stable (n = 258) | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| B) Probability of negative communication conditional on relationship satisfaction | ||||

| 1. Increasing (n = 357) | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.57 | 0.30 |

| 2. Low-stable (n = 658) | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.35 |

| 3. Decreasing (n = 293) | 0.18 | 0.73 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| 4. High-stable (n = 258) | 0.44 | 0.17 | 0.00 | .39 |

| C) Probability of joint relationship satisfaction and negative communication | ||||

| 1. Increasing (n = 357) | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| 2. Low-stable (n = 658) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.38 | .01 |

| 3. Decreasing (n = 293) | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| 4. High-stable (n = 258) | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

Note. N = 1566.

The probability of negative communication conditional on relationship satisfaction was also examined (see Table 4, part B; the probabilities in each column sum to 1.0). These probabilities represent the likelihood of membership in one of the negative communication groups, given membership in one of the relationship satisfaction trajectories. There was 73% chance that a youth following the moderate-stable trajectory of satisfaction would also follow the decreasing trajectory of negative communication. No other probabilities were higher than .70, which is the threshold for an acceptable classification (Frankfurt et al., 2016). A youth in the high-stable group of satisfaction had a zero probability of being in the high-stable group of negative communication.

Joint probabilities of membership are reported in Table 4 (part C). The probability in all cells sum to 1.0. Four groups accounted for 73% of the sample. The largest group (38%) represented the emerging adults who belonged in both the high-stable group of satisfaction and the low-stable group of negative communication. The second largest group (13%) represented emerging adults in both the increasing satisfaction group and the moderate-stable negative communication group. The third largest group (12%) was composed of emerging adults in both the high-stable group of relationship satisfaction and the moderate-stable group of negative communication. Finally, the fourth largest group (10%) represented the emerging adults in the increasing group of relationship satisfaction and the high-stable group of negative communication.

Profile Analyses

We examined differences in sociodemographic characteristics across the final four trajectories of relationship satisfaction (Table 5) and four trajectories of negative communication (Table 6). No significant differences across the trajectory groups for relationship satisfaction and negative communication emerged regarding gender, relationship length, change of partner or years of education (p > .05). In addition, the effect sizes for all sociodemographic variables were small or negligible (η2 < .01, φ < .3).

Table 5.

Profiles of Relationship Satisfaction Trajectories.

| 1. Increasing (n = 52) | 2. Moderate-Stable (n = 255) | 3. High-Stable (n = 1171) | 4. U-Curve (n = 88) | χ2/F | p | Effect Size (φ/η2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .572 | .903 | .019 | ||||

| Female (% (n)) | 80.0% (42) | 75.5% (193) | 74.7% (875) | 75.0% (66) | |||

| Male (% (n)) | 20.0% (10) | 24.5% (62) | 24.5% (287) | 25.0% (22) | |||

| Remained with the same partner (% (n)) | 0% (0) | 0.9% (2) | 0.2% (2) | 0% (0) | 3.299 | .348 | .152 |

| Changed partner once (% (n)) | 5% (3) | 9.8% (25) | 14.5% (170) | 7.5% (7) | 1.504 | .618 | .103 |

| Changed partners more than once (% (n)) | 95% (49) | 89.3% (228) | 85.3% (999) | 92.5% (81) | 2.462 | .482 | .131 |

| Relationship length (M (SD)) | 16.92 (11.33) | 17.10 (14.30) | 17.75 (15.22) | 14.58 (11.22) | .631 | .595 | .001 |

| Years of education (M (SD)) | 11.83 (1.24) | 11.90 (1.46) | 11.84 (1.38) | 11.82 (1.06) | .130 | .942 | .000 |

Note. N = 1566. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables (gender and change of partner) and one-way ANOVAs were conducted for continuous variables (relationship length and years of education).

Table 6.

Profiles of Negative Communication Trajectories.

| 1. Increasing (n = 357) | 2. Low-Stable (n = 658) | 3. Decreasing (n = 293) | 4. High-Stable (n = 258) | χ2/F | P | Effect Size (φ/η2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 2.823 | .420 | .042 | ||||

| Female (% (n)) | 76.3% (272) | 73.5% (484) | 77.9% (228) | 76.5% (197) | |||

| Male (% (n)) | 23.7% (85) | 26.5% (174) | 22.1% (65) | 23.5% (61) | |||

| Remained with the same partner (% (n)) | 0% (0) | 0.2% (1) | 0.7% (2) | 0.4% (1) | 2.269 | .519 | .126 |

| Changed partner once (% (n)) | 9.1% (33) | 7.4% (49) | 7.4% (22) | 7.4% (19) | 1.940 | .585 | .116 |

| Changed partners more than once (% (n)) | 90.9% (324) | 92.6% (608) | 92.6% (269) | 92.6% (238) | 2.149 | .542 | .123 |

| Relationship length (M (SD)) | 19.34 (15.66) | 16.75 (14.48) | 17.25 (15.18) | 19.43 (15.33) | 2.531 | .056 | .006 |

| Years of education (M (SD)) | 11.90 (1.31) | 11.82 (1.35) | 11.84 (1.51) | 11.91 (1.36) | .353 | .787 | .001 |

Note. N = 1566. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables (gender and change of partner) and one-way ANOVAs were conducted for continuous variables (relationship length and years of education).

Discussion

The aim of the current study is to investigate the different trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication and to examine whether they are interrelated among dating emerging adults as they get older. Given the importance of early romantic experiences on later relationship functioning and the lack of previous research on emerging adults’ dating relationships, this study contributes to the literature in a new and meaningful way by using participants’ age as a time metric and sophisticated statistical analyses. An exploratory approach was used given that this is the first study to investigate these trajectories in a sample of emerging adults. We found different individual and joint trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication in our sample, controlling for the change of partners over the years.

Individual Trajectories

Our results revealed that relationship satisfaction and negative communication both evolved following four distinct trajectories. The U-shaped curve was observed in 5.6% of our sample for relationship satisfaction. This trajectory is consistent with recent findings showing that there is a portion of married individuals for whom relationship satisfaction followed a pattern similar to a U-shaped curve (Anderson et al., 2010; James, 2015). In the current study, it is possible that this U-shaped curve is linked to different life events (e.g., a change of partner or a long distance relationship) and may be representing emerging adults who are establishing the basis of their future relationships. Akin to previous studies, an inverted U-shaped curve was not found for negative communication.

Consistent with studies conducted on married couples, a high and stable trajectory of relationship satisfaction was found. In fact, approximately three quarters of our sample reported high relationship satisfaction that remained stable throughout the study, despite some emerging adults changing partners over the years. In addition, a moderate and stable trajectory of satisfaction was also found in 16.3% of our sample. Regarding negative communication, two stable trajectories were found, one representing emerging adults who reported high negative communication over time (16.5%) and one representing emerging adults who reported low negative communication across all ages (42.0%). These four trajectories are consistent with the findings from Beckmeyer and Jamison (2021) who identified high and low levels of relationship satisfaction and negative communication in their sample of emerging adults. Akin to married couples, some emerging adults in dating relationships can function quite well romantically in the long term despite potentially changing partners and being in a period of identity consolidation (Luyckx et al., 2011). These stable trajectories also provide support to the enduring dynamics model and are consistent with recent longitudinal evidence of stability in relationship satisfaction and negative communication in married couples (Lavner et al., 2020; Williamson, 2021; Williamson & Lavner, 2020). It is possible that the stability observed in relationship satisfaction and negative communication in married couples begin well before marriage and even transcend relationships. Some individuals may be more likely to always be satisfied or dissatisfied – or communication positively or negatively – notwithstanding their partner.

Our results provided evidence that, for some emerging adults, relationship satisfaction tends to improve over time. Three percent of our sample experienced a drastic increase in relationship satisfaction over the years, despite their change in partners. Similarly, around 19% of our sample experienced a drastic decrease in their use of negative communication as they got older. We named this phenomenon “Getting wiser with age”. It is possible that these emerging adults gained experience with age and may have developed more relational skills necessary for the functioning of their relationship(s). Indeed, romantic relationships have been found to become less intense and turbulent as adolescents enter adulthood and this decline for some emerging adults in the use of negative communication and increase in relationship satisfaction could be explained by the emergence of skills and experience at handling complex couples’ dynamics in early adulthood (Lantagne & Furman, 2017; Rueda et al., 2021). They could also have experienced a developmental shift in identity formation that is crucial in the process of selecting a romantic partner. Some studies have found that adolescents tend to focus more on popularity and physical attractiveness while adults tend to prefer warmth and trustworthiness when selecting a partner (Gerlach et al., 2019; Simon et al., 2008). While it would need further investigation, choosing a partner based on warmth and trust may have helped these emerging adults to improve their relationship satisfaction and communication.

Moreover, one trajectory was characterized by an increase in the use of negative communication over the years. For these emerging adults, problems in communication might continue as they get older throughout their future relationships. This tendency was actually found in some married couples (Lindahl et al., 1998; Umberson et al., 2006) and may thus have started well before marriage highlighting the importance of helping emerging adults improve their communication skills early on. That being said, this decline across time could be domain specific as none of the trajectories of relationship satisfaction represented a decline over the years notwithstanding whether they change partners over the years or not. Negative communication consists of observable behaviours and exchanges between both partners and could therefore be perceived by emerging adults as a skill that can be improved. In contrast, relationship satisfaction is a state characterized by the perception of the degree of satisfaction in the relationship. It is therefore possible that emerging adults who experienced a steady decline in their relationship satisfaction, without any light at the end of the tunnel, may have decided to terminate the relationship for this reason, allowing them to find a partner with whom the satisfaction was greater.

Supplementary analyses were performed to determine whether the participants’ gender, change of partner, relationship length, or years of education was significantly different across the final trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication. No statistically significant differences were found, suggesting that these variables did not play a role in the participants’ membership to one trajectory versus another. It is possible that other relational characteristics may have had more impact, such as the level of engagement, attachment security, trust, and/or jealousy. Other individual characteristics may also have helped distinguish the participants in the different trajectories, such as personality traits, perfectionism, decision-making abilities, or communication skills.

Joint Trajectories

Looking at the combined trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication, a high concordance between the two dimensions was observed. Our most prevalent group (38%) consisted of emerging adults who reported both stable and high relationship satisfaction and stable and low negative communication across time (i.e., parallel trajectories). This is consistent with findings from Beckmeyer and Jamison (2021) who observed that approximately 50% of their sample of emerging adults reported at one point in time high relationship satisfaction and low negative interactions (i.e., happily independent and consolidated relationships). We did not find trajectories in line with the exploratory and stuck relationships previously found by Beckmeyer and Jamison (2021) that were characterized by low relationship satisfaction and high negative communication. Moreover, a third of our sample (33%) followed unparallel trajectories. For 12% of emerging adults, they experienced moderate and stable relationship satisfaction and high and stable negative communication. Similarly, 23% of our sample followed the high/moderate trajectory of relationship satisfaction while also experiencing increasing and stable negative communication. For these emerging adults, negative communication did not seem to impact their relationship satisfaction negatively. These trajectories are similar to the description of high-intensity relationships defined by Beckmeyer and Jamison (2021). However, in their study, they found a small proportion of emerging adults in this group (9.3%) in contrast with 33% in the current study. It is possible that this difference is due to the age of the participants. The emerging adults from the current study are younger (17–24 years old compared to 18–29 years old in Beckmeyer and Jamison, 2021). As mentioned above, emerging adults generally tend to improve their communication skills over time and their romantic relationships often become less intense and turbulent as they age (Lantagne & Furman, 2017; Rueda et al., 2021).

A difference in the probabilities of relationship satisfaction conditional on negative communication was noted between the moderate-stable and high-stable trajectories. Of note, when following the low-stable trajectory of negative communication, participants had a 4% probability of being in the moderate-stable group of relationship satisfaction and a 94% chance of being in the high-stable group of relationship satisfaction. Similarly, when following the high-stable trajectory of negative communication, participants had a 74% chance of being in the moderate-stable trajectory of relationship satisfaction and a 0% chance of being in the high-stable trajectory of relationship satisfaction. Although the moderate-stable and high-stable trajectories of relationship satisfaction do not appear very different from one another at first glance, it is believed that they differ clinically in a significant way. The moderate-stable trajectory of relationship satisfaction is close to the borderline range identified by the authors who validated the DAS-4 (Sabourin et al., 2005). The borderline range corresponds to scores between 12 and 14 on the DAS-4, while those with scores under 12 are categorized as clinically distressed. While the high-stable trajectory of relationship satisfaction is well above the borderline range, which scores consistently close to 18, the moderate-stable trajectory is between 13 and 15.5. Thus, for these emerging adults, it makes sense that they are more likely to report high levels of negative communication.

Limitations and Future Directions

The use of the participants’ age as a time metric is constitute a strength of this study. It allowed us to observe the trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication of emerging adults between the ages of 17 and 24 years old, despite the variations in the stability of their relationships. Nonetheless, this needs to be considered when comparing our results with studies that used relationship length as a time metric. In addition, our results complement studies conducted using a sample of long-term established couples, but generalization should be limited to dating emerging adults. Large-scale longitudinal studies following participants from adolescence to late adulthood would help bridge the gap between our results and those found in married couples. Regarding our sample, while we achieved to recruit a large number of emerging adults, it is important to note that our sample was composed in majority of self-identified women in opposite-sex relationships. Further studies could pursue the replication process across samples with broader diversity of gender and gender expression, sexual orientation, as well as cultural and ethnic background. Moreover, despite the use of questionnaires allowing researchers to reach out to more participants, particularly in large longitudinal studies, self-report questionnaires can be affected by the participants’ mood at the time of completion, a lack of introspection, and/or to recall and social desirability biases. Future studies may find pertinent to use questionnaires, daily diaries and direct observations of relationship satisfaction and the communication patterns between partners to verify whether measurement can lead to different results.

Clinical Implications

This is important given that relationship satisfaction and dyadic communication can be considered as the backbone of relationship functioning (see Bélanger et al., 2017; Eid & Lachance-Grzela, 2017). Because of their upmost importance, empirically validated couples’ interventions have included the improvement of relationship satisfaction and negative communication patterns in their intervention’s goals. For instance, integrative couple behavioral therapy (ICBT) targets the way partners communicate together in order to improve their relationship satisfaction (Christensen et al., 2020) while emotionally focused therapy (EFT) attempts to reduce negative interactions between partners by encouraging them to be emotionally attuned to their partner (Johnson, 2020). The current study provides useful insights to these clinical interventions since our results demonstrated that relationship satisfaction and negative communication do not evolve in the same ways for everyone. For some emerging adults, a change in negative communication may not be associated with a change in their relationship satisfaction and vice versa, demonstrating the importance of continuously monitoring both dimensions throughout intervention. In addition, our results revealed that a fairly large proportion of emerging adults communicate negatively very early on in their dating life but still report high relationship satisfaction. For these emerging adults, targeted prevention programs, such as the Hold-Me-Tight Relationship-Education program (Johnson, 2010) or an IBCT-based conflict prevention program (Barraca et al., 2021), would be useful to improve their communication skills before their relationship satisfaction begin to decline. These programs could also be helpful for those who experience low relationship satisfaction from the beginning of their dating life.

Conclusion

The current study shed light on the evolution of relationship satisfaction and negative communication in emerging adults whether they were with the same partner or not across time. Our results provided evidence for the most prevalent theoretical models of relationship development and also revealed novel single and joint trajectories of relationship satisfaction and negative communication specific to emerging adults. Taken together, these results have highlighted not only the different relational trajectories of emerging adults, but also the different ways in which these trajectories are interrelated. The main take home message of this study is that relationship satisfaction and negative communication do not evolve in the same way for all emerging adults. It is therefore important to continue studying the evolution of these two dimensions in order better understand on which individual (e.g., personality traits, self-esteem, perfectionism), relational (e.g., romantic attachment, intimate partner violence, sexual satisfaction), and cultural (e.g., eastern societies, religion) characteristics they differ.

Author Biographies

Stephanie Jolin, B.A., is completing her Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology at the School of Psychology of the University of Ottawa. She is a member of the Couple Research Lab. Her research interests include relationship satisfaction, communication, emerging adults, adult romantic attachment, and sexuality.

Marie-France Lafontaine, Ph.D., is a Full Professor and the Director of the Couple Research Lab at the School of Psychology of the University of Ottawa. Her research interests include couple relationships, romantic attachment, intimate partner violence, self-injury, telepsychotherapy, and family health.

Yvan Lussier, Ph.D., is a Full Professor in the Department of Psychology of the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières. He is the Director of the Couple Psychology Laboratory and a researcher at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Spousal Problems and Sexual Assault. His research interests include romantic relationships, relationship satisfaction and dyadic adjustment, adult romantic attachment, and intimate partner violence.

Audrey Brassard, Ph.D., is a Full Professor in the Department of Psychology at the Université de Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada, and Director of “Us” Couple and Sexuality research lab. Her research and clinical interests include intimate relationships, romantic attachment, intimate partner violence, communication, and sexuality.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: We hereby declare that there is no conflict of interest to disclose and that we have complied with APA ethical standards in the treatment of our research participants. This project was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada. Doctoral scholarships from the SSHRC of Canada, the Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS), and the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture (FQRSC) were awarded to the first author.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Data Availablity Statement: The raw data, analysis code/syntax, and materials used in this study are not openly available but are available upon request to the corresponding author. This study did not pre-register the plan for data collection or analysis.

ORCID iDs

Stephanie Jolin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0633-9024

Marie-France Lafontaine https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4185-6326

Audrey Brassard https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2292-1519

References

- Anderson J. R., Van Ryzin M. J., Doherty W. J. (2010). Developmental trajectories of marital happiness in continuously married individuals: A group-based modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 587–596. 10.1037/a0020928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. A., Russell C. S., Schumm W. R. (1983). Perceived marital quality and family life-cycle categories: A further analysis. Journal of Marriage and the FamilyJournal of Marriage and the Family, 45(1), 127–139. 10.2307/351301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. (2015). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga X. B. (2001). The ups and downs of dating: Fluctuations in satisfaction in newly formed romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(5), 754–765. 10.1037/0022-3514.80.5.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraca J., Nieto E., Polanski T. (2021). An integrative behavioral couple therapy (IBCT)-Based conflict prevention program: A pre-pilot study with non-clinical couples. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 9981. 10.3390/ijerph18199981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmeyer J., Jamison T. B. (2021). Identifying a typology of emerging adult romantic relationships: Implications for relationship education. Family Relations, 70(1), 305–318. 10.1111/fare.12464 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger C., Marcaurelle R., Lazaridès A., Gravel Crevier M., Lafontaine M-F. (2017). Communication, résolution de problèmes et satisfaction conjugale [Communication, conflicts resolution, and relationship satisfaction]. In Lussier Y., Bélanger C., Sabourin S. (Eds), Les fondements de la psychologie du couple (pp. 359–390). Presses de l’Université du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher Bégin N., Boislard M.-A., Otis J. (2021). Pourquoi les adultes émergents actifs sexuellement ne se font-ils pas systématiquement dépister pour les ITSS ? [Why do sexually active adults not systematically get tested for STIs]. Sexologies: European Journal of Sexology, 30(2), 122–131. 10.1016/j.sexol.2021.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury T. N., Cohan C. L., Karney B. R. (1998). Optimizing longitudinal research for understanding and preventing marital dysfunction. In Bradbury T. N. (Ed), The developmental course of marital dysfunction (pp. 279–311). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A. (1987). Detection of conflict patterns in couples. In Hahlweg Dans K., Goldstein M. J. (Eds), The Family Process Press monograph series. Understanding major mental disorder: The contribution of family interaction research (pp. 250–265). Family Process Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A., Doss B. D., Jacobson N. S. (2020). Integrative behavioral couple therapy: A therapist’s guide to creating acceptance and chance, 2nd ed. W. W. Norton & company. Psychology : Research & Practice, 35(6), 608–614. 10.1037/0735-7028.35.6.608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J., McIsaac C., Shulman S., Wincentak K., Joly L., Heifetz M., Bravo V. (2014). Development of romantic relationships in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Implications for community mental health. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 33(1), 7–19. 10.7870/cjcmh-2014-002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courtain A., Glowacz F. (2018). Youth”s conflict resolution strategies in their dating relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(2), 256–268. 10.1007/s10964-018-0930-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid P., Lachance-Grzela M. (2017). Ruptures amoureuses [Romantic breakups]. In Lussier Y., Bélanger C., Sabourin S. (Eds), Les fondements de la psychologie du couple (pp. 621–646). Presses de l’Université du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham F. D., Cui M. (2010). Emerging adulthood and romantic relationships: An introduction. In Fincham D., Cui M. (Eds), Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood (pp. 3–12). Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt S., Frazier P., Syed M., Jung R. K. (2016). Using group-based trajectory and growth mixture modeling to identify classes of change trajectories. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(5), 622–660. 10.1177/0011000016658097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach T. M., Arslan R. C., Schultze T., Reinhard S. K., Penke L. (2019). Predictive validity and adjustment of ideal partner preferences across the transition into romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(2), 313–330. 10.1037/pspp0000170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A., Finn C., Neyer F. (2021). Patterns of romantic relationship experiences and psychosocial adjustment from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(3), 550–562. 10.1007/s10964-020-01350-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensen J., Reise S., Kim K. (2007). Detecting mixtures from structural model differences using latent variable mixture modeling: A comparison of relative model fit statistics. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(2), 202–226. 10.1080/10705510709336744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huston T. L. (1994). Courtship antecedents of marital satisfaction and love. In Erber R., Gilmour R. (Eds), Theoretical frameworks for personal relationships (pp. 43–65). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- James S. L. (2015). Variation in trajectories of women’s marital quality. Social Science Research, 49, 16–30. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. M. (2010). The hold me tight program: Conversations for connection. International Centre for Excellence in Emotionally Focused Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. M. (2020). The field of couple therapy and EFT. In Johnson S. (Ed), The practice of emotionally focused couple therapy: Creating connection (3rd ed., pp. 3–24). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. L., Nagin D. S. (2007). Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociological Methods & Research, 35(4), 542–571. 10.1177/0049124106292364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. L., Nagin D. S., Roeder K. (2001). A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods and Research, 29(3), 374–393. 10.1177/0049124101029003005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp Dush C. M., Taylor M. G. (2012). Trajectories of marital conflict across the life course: Predictors and interactions with marital happiness trajectories. Journal of Family Issues, 33(3), 341–368. 10.1177/0192513X11409684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine M.-F., Jolin S., Séguin M., Brassard A., Lussier Y. (2021). Validation des versions abrégées francophones du Communication. School of Psychology, University of Ottawa. Pattern Questionnaire [Validation of brief French versions of the Communication Pattern Questionnaire] [Unpublished manuscript]. [Google Scholar]

- Lantagne A., Furman W. (2017). Romantic relationship development: The interplay between age and relationship length. Developmental Psychology, 53(9), 1738–1749. 10.1037/dev0000363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner J. A., Bradbury N. B. (2010). Patterns of change in marital satisfaction over the newlywed years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1171–1187. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00757.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner J. A., Williamson H. C., Karney B. R., Bradbury T. N. (2020). Premarital parenthood and newlyweds’ marital trajectories. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), 279–290. 10.1037/fam0000596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl K., Clements M., Markman H. (1998). The development of marriage: A 9-year perspective. In Bradbury T. N. (Ed), The developmental course of marital dysfunction (pp. 205–236). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511527814.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K., Schwartz S. J., Goossens L., Beyers W., Missotten L. (2011). Processes of personal identity formation and evaluation. In Schwartz S. J., Luyckx K., Vignoles V. L. (Eds), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 77–98). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J., Welti K., Wildsmith E., Barry M. (2014). Relationship types and contraceptive use withing young adult dating relationships. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 46(1), 41–50. 10.1363/46e0514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman H. J., Rhoades G. K., Stanley S. M., Ragan E. P., Whitton S. W. (2010). The premarital communication roots of marital distress and divorce: The first five years of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(3), 289–298. 10.1037/a0019481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall (2008). Cultural differences in intimacy: The influence of gender-role ideology and individualism—collectivism. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(1), 143–168. 10.1177/0265407507086810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty J. K., Meltzer A. L., Neff L. A., Karney B. R. (2021). How both partners' individual differences, stress, and behavior predict change in relationship satisfaction: Extending the VSA model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(27), e2101402118. 10.1073/pnas.2101402118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A., Allen G. (2009). Romantic relationships from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence from the National longitudinal study of adolescent health. Sociological Quarterly, 50(2), 308–335. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01142.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. (2005). Group based modeling of development. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. S., Odgers C. L. (2010). Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1), 109–138. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netting, Reynolds M. K. (2018). Thirty years of sexual behaviour at a Canadian university: Romantic relationships, hooking up, and sexual choices. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 27(1), 55–68. 10.3138/cjhs.2017-0035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauer A. J., Pettit G. S., Lansford J. E., Bates J. E., Dodge K. A. (2013). Romantic relationship patterns in young adulthood and their developmental antecedents. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2159–2171. 10.1037/a0031845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades G. K., Kamp Dush C. M., Atkins D. C., Stanley S. M., Markman H. J. (2011). Breaking up is hard to do: The impact of unmarried relationship dissolution on mental health and life satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(3), 366–374. 10.1037/a0023627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson P. N., Norona J. C., Fish J. N., Olm- stead S. B., Fincham F. (2017). Do differences matter? A typology of emerging adult romantic relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Rela- Tionships, 34(3), 334–355. 10.1177/0265407516661589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda H. A., Yndo M., Williams L. R., Shorey R. C. (2021). Does gottman’s marital communication conceptualization inform teen dating violence? Communication skill deficits analyzed across three samples of diverse adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(11-12), 6411–6440. 10.1177/0886260518814267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin S., Valois P., Lussier Y. (2005). Development and validation of a brief version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale using a nonparametric item analysis model. Psychological Assessment, 17(1), 15–27. 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon V. A., Aikins J. W., Prinstein M. J. (2008). Romantic partner selection and socialization during early adolescence. Child Development, 79(6), 1676–1692. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01218.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B. G., Fidell L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., Williams K., Powers D. A., Liu H., Needham B. (2006). You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(1), 1–16. 10.1177/002214650604700101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanLaningham J., Johnson D. R., Amato P. (2001). Marital happiness, marital duration, and the U-shaped curve: Evidence from a five-wave panel study. Social Forces, 79(4), 1313–1341. 10.1353/sof.2001.0055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson H. C. (2021). The development of communication behavior over the newlywed years. Journal of Family Psychology : JFP : Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 35(1), 11–21. 10.1037/fam0000780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson H. C., Lavner J. A. (2020). Trajectories of marital satisfaction in diverse newlywed couples. Social Psychology and Personality Science, 11(5), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1948550619865056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K.-H., Yang-Wallentin F., Bentler P. M. (2012). ML versus MI for missing data with violation of distribution conditions. Sociological Methods & Research, 41(4), 598–629. 10.1177/0049124112460373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang E., Max J. T. (2020). Bayesian estimation and model selection in group-based trajectory models. Psychological Methods. Advance online publication https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/met0000359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Bhatia V., Luginbuehl T., Davila J. (2021). The association between romantic competence and couple support behaviors in emerging adult couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(3), 1015–1034. 10.1177/0265407520980533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]