Abstract

Nutrition cues on ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages (RTDs) may create an illusion of healthfulness; however, nutrition information on alcohol in Canada is seldom regulated. This research aimed to systematically record the use of nutrition cues on a subsample of RTDs sold in grocery stores. In July 2021, all available RTDs were purchased from three major grocery store banners in Québec City, Canada. Data regarding container size, purchase format, alcohol-by-volume (ABV), presence of nutrition cues (nutrient claims, other food-related claims and nutrition facts tables [NFTs]) and container surface occupied by nutrition cues were recorded. RTDs were classified as hard seltzers or pre-mixed cocktails and their ABV as “light-strength” (3.5%–4.0% ABV) and “regular-strength” (>4.0%–7.0% ABV). In total (n = 193), 23% were hard seltzers and 17% light-strength. Most RTDs (68%) had ≥1 type of nutrition cue, most often natural flavour claims (45%), an NFT (38%), and calorie claims (29%). Light-strength beverages were more likely than regular-strength to carry any nutrient claim (97% vs. 19%, p < 0.0001), an NFT (97% vs. 26%, p < 0.0001) and other food-related claims (e.g., natural flavour) (88% vs. 52%, p = 0.0002). In adjusted regression analyses, hard seltzers were more likely than pre-mixed cocktails to carry any nutrient claim (AOR = 19.1, 95% CI:7.5,48.7), any other food-related claim (AOR = 7.5, 95% CI:2.9,19.4), and an NFT (AOR = 45.5, 95% CI:12.6,163.9). The mean container surface occupied by nutrition cues was higher for hard seltzers compared to pre-mixed cocktails (13% vs 3%, p < 0.0001). The high proportion of RTDs carrying nutrition cues supports the need to further regulate labelling and marketing of RTDs.

Abbreviation: RTDs, ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages; ABV, Alcohol by volume; NFT, Nutrition facts table

Keywords: Nutrient claim, Nutrition claim, Alcohol labels, Alcohol policy, Alcoholic beverages, Food environment

1. Introduction

Alcohol consumption is associated with more than 200 negative health conditions, including cancers, liver diseases and mental health consequences (World Health Organization, 2018, Paradis et al., 2023). Alcohol is both an addictive psychoactive substance and a commonly consumed commodity that is heavily marketed and widely available (World Health Organization, 2018).

Health consciousness among consumers is a growing phenomenon in Canada and globally (Euromonitor International, 2021). In ongoing efforts to increase their consumer base and maintain sales trajectories, the alcohol industry has created or rebranded beverage categories, such as ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages (RTDs), to more effectively reach health-conscious consumers (Keric and Stafford, 2019). The alcohol industry has also developed promotion strategies to create an illusion of healthfulness such as claims on principal panel container labels of select alcoholic beverages (e.g., “natural”, “low carb”) (Keric and Stafford, 2019), which may also decrease perceived health risks of alcohol consumption (Miller et al., 2010) by creating a health halo effect (Cao et al., 2022). This occurs when consumers infer that one particular nutrient being “low” (e.g., 0 g sugar) means the product is “healthy”, making consumers more likely to choose and consume a product or consume it in greater quantities (Choi et al., 2013, Hall, 2020, Kaur et al., 2017).

Alcohol advertising and promotion restrictions are often limited to traditional media (e.g., television, radio) and mostly apply to product placement and sales promotions. These restrictions generally have limited authority over other key advertising channels, including product packaging. The Canadian Food and Drugs Act prohibits the use of label statements or advertising of a food product that may mislead or create an erroneous impression regarding its composition or safety (Department of Justice Canada, 2021). Similarly, in the province of Québec, the Act Respecting Offences Relating to Alcoholic Beverages forbids the representation of an alcoholic beverage as “beneficial to health or possess[ing] nutritive or curative value” (Ministère du Travail, 1979). However, there are currently no specific regulations prohibiting the use of nutrient claims (e.g., calorie, carbohydrate, and sugar claims) and other food-related claims (e.g., natural flavour, organic, etc.) about or on alcohol products in Canada. Unlike most packaged food and beverages in Canada, alcoholic beverages of more than 0.5% alcohol by volume (ABV) are not mandated to display a nutrition facts table (NFT) unless “a representation about or implying nutritional or health related properties” is made, among other conditions (Government of Canada, 2022).

Given the possible adverse impacts of nutrition cues (nutrient claims, other food-related claims, and NFTs) on select alcoholic beverage containers on consumers’ perceptions of alcoholic products, research on their prevalence is warranted. The objective of this study was to record the use of nutrition cues among a subsample of RTD containers sold in grocery stores in Québec City (QC), Canada.

2. Methods

2.1. Environmental scan

In the Canadian province of Québec, only malt-, cider- and wine-based alcoholic beverages are sold in grocery stores (Government of Québec, 2018), whereas spirits and spirit-based RTDs are exclusively sold in government-owned outlets. In this study, RTDs were defined as alcoholic products (malt-, cider- or wine-based) pre-mixed with another non-alcoholic beverage, that were packaged ready for consumption in a single serve container (equivalent to 1 to 1.5 Canadian standard drinks (Government of Canada, 2021), excluding standard beer, wine and cider. These non-traditional drinks were selected because they are highly marketed and popular among younger consumers (Huckle, 2008, Mosher and Johnsson, 2005), who may also be more health conscious (MarketLine, 2018a). These beverages represented the fastest growing alcoholic drinks category in Canada in 2019–2020 (Statistics Canada, 2021), and a recent Australian study found that RTDs were the alcohol category most frequently carrying nutrition cues on container labels (Barons et al., 2022).

In July 2021, available RTDs were purchased in three grocery stores from three major store banners in Québec City, Québec. Every flavour of every product from all brands was purchased. Duplicates were not purchased multiple times. If a product was only available in a multiple-container package (multi-pack), the smallest multi-pack available (e.g., a 4-pack, 6-pack or 12-pack) was purchased. Low alcohol products (containing <1.1% ABV) were excluded as ABV is not required to be declared on their labels (Government of Canada, 2022).

2.2. Database creation

Information present on the individual containers (brand, container size, purchase format (i.e., multi-pack, individual can), flavour, ABV, presence/absence of list of ingredients, nutrient claims, other food-related claims, NFT, quantitative nutritional information when available) was systematically coded in a database. Container size (355 ml vs 473 ml), as well as ABV (light- vs regular-strength) were coded. Light-strength was defined as 1.1% to 4.0% ABV, whilst regular-strength was defined as >4.0% ABV, as per labelling requirements for beer and cider in Canada (Government of Canada, 2020, Government of Canada, 2020).

RTDs were classified as pre-mixed cocktails (pre-mixed beverage with alcohol and a non-alcoholic product, for example regular Palm Bay or Smirnoff Ice products) or hard seltzers (carbonated water, alcohol, and flavouring, for example White Claw). The distinction between a hard seltzer and a pre-mixed cocktail was not always clear as some pre-mixed cocktails use similar terminology (e.g., hard soda water) to hard seltzers. Thus, hard seltzers were defined as such if it was explicitly described as “seltzer” on the product. Available products containing caffeine were included.

2.2.1. Québec vs Canadian/multinational brand

Brand location was coded as only available in Québec or available elsewhere, using data from the website of the largest alcohol retailer in Canada owned and operated by the Canadian province of Ontario (the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO)) (Canadian Free Trade Agreement, 2020). Brands not found on the LCBO website were considered only available in the province of Québec.

2.2.2. Nutrition cues

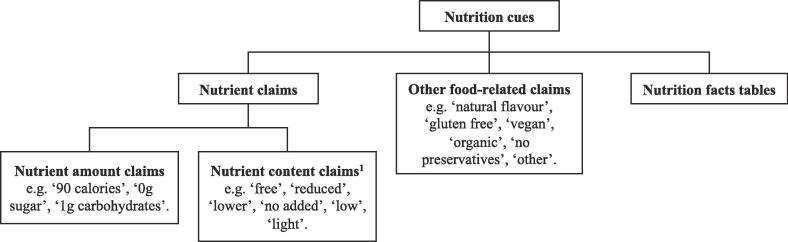

In the current study, the term “nutrition cues” is used to describe all nutrition-related information present on packages, including: 1) nutrient claims about sugar, carbohydrates, and calories (including both nutrient amount claims [e.g., “90 calories”] and nutrient content claims [e.g., “free of”]); 2) other food-related claims (e.g., “natural flavour”, “gluten free”, etc.); and 3) NFTs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Taxonomy of nutrition cues used on RTDs in this study (Québec City (QC), Canada in July 2021). RTDs = ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages. 1 As per Health Canada’s definition of sugar, carbohydrate and calorie claims on foods and non-alcoholic beverages (Government of Canada, 2021, Government of Canada, 2021).

2.2.2.1. Nutrient claims

Nutrient claims included nutrient amount claims and nutrient content claims about sugar, carbohydrates or calories (Fig. 1). Nutrient amount claims were defined as the mention of sugar or carbohydrate (in grams) or calorie (kcal) amount (e.g., “90 calories”). Nutrient content claims included statements of “free”, “reduced”, “lower”, “no added”, “low”, “light”, in alignment with Health Canada’s definition of sugar, carbohydrate and calorie claims on foods (Government of Canada, 2021, Government of Canada, 2021). Presence/absence of each claim was coded as a binary variable.

2.2.2.2. Other food-related claims

Binary variables for presence/absence of other food-related claims were created for “natural flavour”, “gluten free”, “vegan”, “organic”, “no preservatives” and “other” for less common claims, such as “made from real fruit”.

2.2.2.3. Nutrition facts tables

The presence/absence of an NFT on containers was coded as a binary variable.

2.2.3. Estimated percentage of container surface occupied by nutrition cues

Each individual container was photographed using the camera panorama function whilst the container rotated on a turning table to capture 360-degree flat photos of the label. Pictures were uploaded on Microsoft PowerPoint. A rectangle was drawn over the container to cover the entire surface (360-degrees), and the surface dimensions were recorded. The same procedure was used to record the size of each individual claim and NFT, when applicable (Supplementary Fig. S1). The estimated percentage of container surface occupied by nutrition cues was calculated by dividing the total surface of the nutrition cues by the surface of the container. Claims in English and French, the two official languages in Canada, were both considered. The current study did not assess nutrition cues on multi-pack packaging, such as boxes or plastic wrapping.

2.3. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics included sample characteristics of the containers and percentage of RTDs in the sample with nutrient claims, other food-related claims and an NFT, overall and by RTD and ABV category. The mean percentage of container surface occupied by nutrition cues overall and by RTD category was assessed descriptively, and differences between RTD categories were assessed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

Separate logistic regression models were conducted to predict the presence of any nutrient claim (all sugar, carbohydrate and calories claims combined) and for sugar, carbohydrate and calorie claims individually, as well as for the presence of an NFT, on RTD categories (hard seltzer vs pre-mixed cocktail), adjusting for container size (355 ml vs 473 ml) and purchase format (from multi-pack vs individual can). The same analysis was conducted for any other food-related claim (all other food-related claims combined) and for each type of other food-related claim, adjusting for the variables described above. Sensitivity analyses examining brand location (Québec vs Canadian /multinational brand) in regression models were conducted. Models were not adjusted for ABV category (light-strength vs regular-strength) because this variable almost perfectly predicted the presence of a claim, leading to instability in the models. Chi-square tests were used in analyses pertaining to ABV category. For all analyses, 95% confidence intervals were used. Statistical analyses were computed using SAS Studio 3.8. The current study did not include human participants.

3. Results

3.1. Sample description

A total of 193 unique RTDs were identified, from which 77% were pre-mixed cocktails and 23% were hard seltzers, representing a total of 49 distinct brands. Most products (67%) were produced by Québec-based brands, and 33% of products were produced by Canadian or multinational brands available elsewhere in Canada. The mean ABV for all products was 5.0%, ranging from 4.0% to 5.0% (hard seltzers) and 3.5% to 7.0% (pre-mixed cocktails). Light-strength beverages (1.1% to 4.0% ABV) represented 17% of the sample. Most products were sold in 355 ml containers (62%), and 38% were in 473 ml containers; and most products were purchased individually (62%).

3.2. Frequency of nutrition cues

The frequency of products carrying nutrition cues for all products and by RTD category is shown in Table 1. Overall, 68% of products had at least one type of nutrition cue, and 65% of products had at least one type of claim (nutrient or other food-related claim). Other food-related claims were the most common nutrition cue (displayed on 86% of hard seltzers, 49% of pre-mixed cocktails [X2 = 19.41, p < 0.0001]), followed by NFTs (91% of hard seltzers, 22% of pre-mixed cocktails [X2 = 68.29, p < 0.0001]) and nutrient claims (82% of hard seltzers, 17% of pre-mixed cocktails [X2 = 64.55, p < 0.0001]). Overall, all RTDs carrying a nutrient claim also had an NFT, in line with Canadian regulations. Few RTDs (6%) carried an NFT without having any nutrient claim, and this was similar for both RTD categories. The prevalence of nutrition cues on products carrying at least one instance of nutrition cue by alcohol strength is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Frequency of RTDs (n = 193) with nutrition cues in Québec City (QC), Canada in July 2021.

| Type of nutrition cue |

All products (n = 193) |

Pre-mixed cocktails (n = 149) |

Hard seltzers (n = 44) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Any nutrient claim | 62 | 32 | 26 | 17 | 36 | 82 |

| Sugar | 39 | 20 | 20 | 13 | 19 | 43 |

| Carbohydrate | 20 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 17 | 39 |

| Calorie | 56 | 29 | 22 | 15 | 34 | 77 |

| Any other food-related claim | 111 | 58 | 73 | 49 | 38 | 86 |

| Natural flavour | 87 | 45 | 55 | 37 | 32 | 73 |

| Gluten free | 25 | 13 | 20 | 13 | 5 | 11 |

| Vegan | 13 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 18 |

| Organic | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| No preservatives | 9 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Other | 19 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 20 |

| Nutrition facts table | 73 | 38 | 33 | 22 | 40 | 91 |

| Nutrition facts table without any nutrient claim* | 11 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 9 |

Abbreviations: RTDs = ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages.

*These alcoholic beverages are not required to carry a nutrition facts table according to Health Canada regulations because they do not carry a nutrient claim (Government of Canada, 2022).

3.3. Presence of nutrient claims and NFT

Regarding sugar and carbohydrate claims, only nutrient amount claims (e.g., “1g sugar”; “1g carbs”) and “low sugar” or “low carbohydrate” claims were observed. Similarly, only calorie amount (e.g., 100 calories) and “light” claims were observed for calorie claims. Estimates from separate logistic regression models examining the presence of nutrient claims or NFTs on RTDs are shown in Table 2. The presence of any nutrient claim differed significantly by RTD category. In adjusted models, hard seltzers were more likely to have sugar, carbohydrate and calorie claims, and an NFT than pre-mixed cocktails. Light-strength beverages were more likely to carry any nutrient claim (97% vs. 19%, X2 = 73.76, p < 0.0001) and an NFT (97% vs. 26%, X2 = 56.88, p < 0.0001) than regular-strength beverages. Specifically, light-strength beverages were more likely to have a sugar claim and a calorie claim (69% vs. 11%, X2 = 56.06, p < 0.0001; 91% vs. 17%, X2 = 70.69, p < 0.0001, respectively) than regular-strength beverages. Sensitivity analyses revealed that products available only in Québec were less likely to carry an NFT compared to products available elsewhere (AOR = 0.3, 95 %CI:0.1, 0.7).

Table 2.

Estimates from separate logistic regression models examining the presence of nutrient claims and a nutrition facts table on RTDs (n = 193) in Québec City (QC), Canada in July 2021.

| Parameter | Any nutrient claim** |

Sugar claim |

Carbohydrate claim |

Calorie claim |

Nutrition facts table |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | |

| RTD category | 38.0* | 10.1* | 23.7* | 38.3* | 34.1* | |||||

| Hard seltzer vs pre-mixed cocktail | 19.08 (7.47,48.70) | 3.66 (1.64,8.17) | 27.26 (7.20,103.19) | 18.47 (7.34,46.51) | 45.49 (12.62,163.93) | |||||

| Container size | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 2.7 | |||||

| 355 ml vs 473 ml | 1.74 (0.61,4.97) | 1.40 (0.48,4.08) | 1.11 (0.25,4.94) | 2.56 (0.84,7.73) | 2.70 (0.83,8.75) | |||||

| Purchase format | 6.8* | 4.4* | 0.0 | 5.0* | 14.6* | |||||

| From pack vs individual can | 3.48 (1.37,8.85) | 2.78 (1.07,7.23) | 1.42 (0.35,5.72) | 2.92 (1.14,7.46) | 6.60 (2.50,17.40) | |||||

Abbreviations: RTDs = ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages. AOR = adjusted odds ratio. CI = confidence interval.

*: Indicates significant Wald χ2 test (p < 0.05).

**: Any nutrient claim includes: “sugar” and “carbohydrate” and “calorie” claims.

Notes: The variable listed second is the reference variable.

3.4. Presence of other food-related claims

Estimates from separate logistic regression models examining the presence of other food-related claims on RTDs are shown in Table 3. Due to the low prevalence of “vegan”, “organic” and “no preservatives” claims, models could not be run for these variables, but they are collectively included in the category “any other food-related claim”. Overall, hard seltzers were more likely to have any other food-related claim, and more likely to have a natural flavour claim than pre-mixed cocktails. Light-strength beverages were more likely to have any other food-related claim (88% vs. 52%, X2 = 14.12, p = 0.0002) compared to regular-strength beverages. Specifically, light-strength beverages were more likely to have a natural flavour claim (78% vs. 39%, X2 = 16.92, p < 0.0001), a vegan claim (16% vs. 5%, X2 = 4.83, p = 0.0280), an organic claim (6% vs 0%, X2 = 10.17, p = 0.0014) and a no preservatives claim (28% vs. 0%, X2 = 47.50, p < 0.0001) than regular-strength beverages. Sensitivity analyses revealed products available only in Québec were less likely to carry a natural flavour claim compared to products available at the Canadian/multinational level (AOR = 0.4, 95 %CI:0.2, 0.8).

Table 3.

Estimates from separate logistic regression models examining the presence of other food-related claims on RTDs (n = 193) in Québec City (QC), Canada in July 2021.

| Parameter | Any other food-related claim** |

Natural flavour |

Gluten free |

Other |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | AOR (95% CI) | |

| RTD category | 17.0* | 13.8* | 0.4 | 3.4 | ||||

| Hard seltzer vs pre-mixed cocktail | 7.47 (2.87,19.43) | 4.28 (1.98,9.22) | 1.46 (0.46,4.65) | 2.63 (0.94,7.40) | ||||

| Container size | 0.7 | 0.8 | 8.2* | 2.2 | ||||

| 355 ml vs 473 ml | 1.38 (0.66,2.90) | 0.72 (0.34,1.51) | 4.24 (1.57,11.40) | 0.31 (0.07,1.44) | ||||

| Purchase format | 1.5 | 0.9 | 12.6* | 4.3* | ||||

| From pack vs individual can | 0.62 (0.28,1.35) | 1.44 (0.67,3.10) | 0.09 (0.02,0.33) | 5.13 (1.09,24.12) | ||||

Abbreviations: RTDs = ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages. AOR = adjusted odds ratio. CI = confidence interval.

*: Indicates significant Wald χ2 test (p < 0.05).

**: Any other food-related claim includes: “natural flavour” and “gluten free” and “vegan” and “organic” and “no preservatives” and “other” claims.

Notes: The variable listed second is the reference variable.

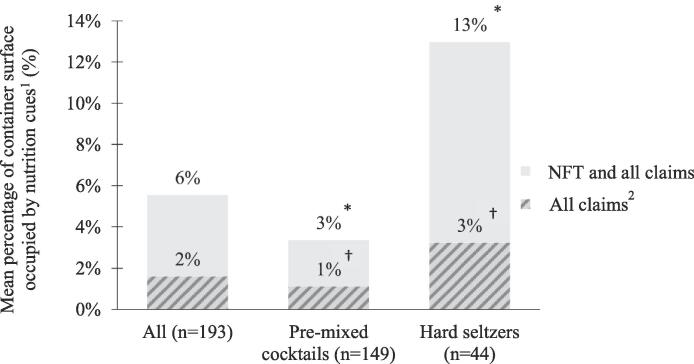

3.5. Mean percentage of container surface occupied by nutrition cues

Fig. 2 shows the mean percentage of container surface occupied by nutrition cues for all products and by RTD category. The mean percentage of container surface occupied by nutrition cues was 6% and differed significantly between RTD categories (3% for pre-mixed cocktails vs 13% for hard seltzers [p < 0.0001]). The mean percentage of container surface occupied by all claims was significantly different between RTD categories (1% for pre-mixed cocktails vs. 3% for seltzers [p < 0.0001]).

Fig. 2.

Mean percentage of container surface occupied by nutrition cues overall and by RTD category (n = 193) in Québec City (QC), Canada in July 2021. Abbreviations: RTDs = ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages, NFT = nutrition facts table. 1 Nutrition cues include NFT and all claims (nutrient claims and other food-related claims). 2 All claims exclude “other claims” of the other food-related claims category. *, †: significantly different (p < 0.0001) (Wilcoxon rank sum test). Similar symbols mean there is a significant difference (p < 0.0001) according to a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

4. Discussion

The use of nutrition cues in this sample of RTDs was pervasive: the majority of sampled products (68%) had at least one type of nutrition cue on their container, and on average, 6% of the container surface was dedicated to nutrition cues. The presence of nutrition cues, such as nutrition claims, can have an impact on consumer’s perception of products by increasing consumer’s perceived healthiness (Cao et al., 2022) as well as selection and intake of the products carrying claims (Hall, 2020, Kaur et al., 2017). The current widespread use of nutrition cues on RTD container labels may mislead the consumer to think these alcoholic beverages are of better nutritional value and are less harmful than products not displaying nutrition cues, despite still containing comparable levels of ethanol which is an addictive psychoactive and toxic substance that increases risks for serious negative health and societal impacts, even when consumed at lower volumes (Keric et al., 2021, Rumgay et al., 2021, World Health Organization, 2018). By doing so, consumers may choose and consume more of these alcoholic beverages than they normally would (Kaur et al., 2017), with potential negative health consequences.

An Australian study reported that 85% of alcoholic beverages using nutrition cues such as claims about nutrients were full-strength ABV products according to Australian classifications of >3.5% ABV (Keric et al., 2021). In the current study, light-strength beverages were more likely to carry any nutrient and any other food-related claim. This may be explained by a higher cutoff for light-strength in the current study (4.0% ABV). The results of the current study are not surprising considering alcohol is an energy-dense nutrient (29 kJ/g of ethanol), meaning light-strength beverages containing less alcohol may be lower in calories, and therefore carry nutrient claims to highlight this attribute. Hard seltzers, which are similar to beer and cider products in ABV, were more likely to carry any nutrient and any other food-related claims, which may make these beverages stand out and appear as a healthier option for consumers compared to other RTDs, or other alcoholic beverage categories. In addition, a greater percentage of the label was dedicated to nutrition cues on hard seltzers (13% vs. 3%), although this was less than the amount of label space that has been shown to be dedicated to branding on alcoholic beverages in other countries (Kersbergen and Field, 2017).

The proportion of RTDs that carried any type of claim (nutrient or other food-related claims) in the current study (65%) was slightly higher than a comparable Australian study (53%) (Haynes et al., 2022). This could be explained by the higher proportion of hard seltzers in our sample, and hard seltzers more frequently carried any type of claim. A higher proportion of RTDs carried any type of claim (nutrient content or health claims) compared to non-alcoholic beverages in another Canadian study (47.9%) (Franco-Arellano et al., 2017), which may suggest RTDs are being more aggressively promoted as “healthy” than non-alcoholic beverages. Highlighting nutrition information and nutrition-related characteristics of alcoholic beverages may further normalize their regular consumption as they appear similar to their non-alcoholic counterparts and can often be purchased adjacent to non-alcoholic beverages in some retail environments. There has been a proliferation of non-alcoholic “diet” beverages largely in response to an increase in health-consciousness among consumers (Euromonitor International, 2022, Euromonitor International, 2022, MarketLine, 2018b). A study among young people ages 16–30 in Canada in 2016 suggested that 61% were trying to consume less sugar, one of the most common dietary efforts reported, and 38% made an effort to consume less calories (Vergeer et al., 2020). The labelling of the majority of RTDs with nutrient and other food-related claims may be an analogous industry response to consumers being increasingly health-conscious and seeking products that are lower in calories or sugar.

Highlighting nutrition cues on containers may also prey upon consumers’ confusion and lack of knowledge around the nutritional and energy content of alcoholic beverages. Evidence suggests that consumers have difficulty estimating the calorie content of alcoholic drinks (Hobin et al., 2022, Robinson et al., 2021) and individuals in Canada who use alcohol consume on average 11% of their daily estimated energy requirements through alcohol (Sherk et al., 2019). Researchers have previously suggested calorie labelling on alcohol containers as a strategy to inform consumers of the energy content of these drinks. Consumers report wanting this information on alcohol containers, and disclosing standardized information may decrease calorie intake from alcohol in the population (Robinson et al., 2021, Sherk et al., 2019). In the current regulatory context, which does not restrict nutrient and other food-related claims on select alcoholic beverage labels in Canada, the alcohol industry may be better able to use nutrition cues as a promotion strategy as opposed to an information tool that is consistently available to consumers on all products.

The role that nutrition information panels, such as an NFT, play in alcohol promotion is unclear. In Canada, NFTs are mandatory on most packaged foods and are closely regulated, but alcoholic beverages of more than 0.5% ABV are exempt from this law unless a nutrient content claim is made (Government of Canada, 2022, Government of Canada, 2019). In the current study, NFTs were used nearly exclusively when a nutrient claim was present, as required by Canadian regulations. We observed that hard seltzers were more likely to carry nutrient claims, and consequently NFTs, than pre-mixed cocktails. Due to current labelling requirements, when a nutrient claim is made, a much greater percentage of the container surface of alcoholic products is dedicated to nutrition cues, as observed in our study. Non-standardized nutrition information on alcoholic products (e.g., present on some beverages and not others) may create additional confusion for consumers, who may infer products with more nutrition cues on the container are a healthier option and make these products appear more similar to non-alcoholic beverages.

5. Policy implications

The frequent use of nutrition cues on alcoholic beverages, particularly in some RTD categories, warrants regulatory consideration. Regulations that aim to restrict promotion and advertising should comprehensively define what type of health-oriented nutrition messaging is permitted. For example, reporting the amount of a nutrient is a way of bypassing regulations and still promoting a product for its apparent positive nutritive aspects (Keric and Stafford, 2019). The World Health Organization suggests that economic operators in alcohol production and trade “eliminate and prevent any positive health claims, and ensure, within regulatory frameworks, the availability of easily-understood consumer information on the labels of alcoholic beverages” (World Health Organization, 2021). At present, these restrictions are largely voluntary action by the industry. Alcohol container labels warning “Alcohol can cause cancer” are another strategy to reduce per capita alcohol consumption (Zhao et al., 2020), and could potentially be used to counter misleading nutrition cues on containers, but future research is warranted. Regardless of the approach, the labelling of alcoholic beverages should be standardized across alcoholic beverage categories.

In addition, how nutrition information induces health halos and the potential for nutrition information to increase intentions to buy and use alcohol requires further examination (Robinson et al., 2021).

6. Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the prevalence of nutrition cues on alcoholic beverage containers in Canada and one of few internationally. However, the sample of beverages may not be representative of the availability of RTDs across Canada and within the province of Québec, as the craft alcohol beverage industry differs across and within provinces. The alcohol industry rapidly develops new products following trends in consumers’ interests; this study only represents the offer available at one time point. This study does not capture other promotional strategies on containers, which may potentially create an erroneous impression for the consumer, such as brand names or imagery (e.g., images of fruit) suggesting health-related outcomes.

7. Future research

Future studies could examine prevalence of nutrition cues on all categories of alcoholic beverages, sold in other locations and sold in different formats as use of nutrition cues may differ. Future research should also assess perceptions and drinking intentions of consumers of alcoholic beverages carrying nutrition cues and differences by demographic characteristics (Public Health Advocacy Institute of Western Australia and Cancer Council Western Australia, 2019). Last, future research should assess the broader marketing of RTDs using nutrition cues beyond the product label, such as on social media or in advertising campaigns.

8. Conclusion

The large proportion of RTDs carrying nutrition cues as a promotion strategy supports the need to further regulate labelling and marketing of RTDs in the province of Québec and across Canada. Future research on nutrition cues used on alcoholic beverage containers is warranted to inform regulatory decisions.

Funding

This work was supported in full by the Centre Nutrition, Santé et Société (NUTRISS), at Université Laval. NUTRISS is supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS). The funder played no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the article for publication. ÉDP and AGH are supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canada Graduate Scholarship - Master’s award and a Fonds de recherche du Québec – santé (FRQS) Master’s Training Award for Applicants with a Professional Degree (#311447, #312301, respectively). VP is the Scientific Director of the Food Quality Observatory (funded by the Government of Quebec). LV is a Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS) scholar.

Author contributions

LV, VP and ÉDP: designed the research; ÉDP and AGH: conducted the research; ÉDP: analyzed the data; ÉDP: wrote the paper; LV: had primary responsibility for the final content; AGH, EH, VP, MN, ABG and LV: read and approved the final manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Élisabeth Demers-Potvin: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. Alexa Gaucher-Holm: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Erin Hobin: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Véronique Provencher: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Manon Niquette: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Ariane Bélanger-Gravel: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Lana Vanderlee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102164.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Barons K.P., et al. Nutrition-related information on alcoholic beverages in Victoria, Australia, 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19(8):4609. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Free Trade Agreement, 2020. Ontario Alcohol Laws. 2020; Available from: https://alcohollaws.ca/ontario/#:∼:text=The%20LCBO%20is%20the%20largest%20alcohol%20retailer%20in,communities%20without%20convenient%20access%20to%20an%20LCBO%20store%29.

- Cao S., et al. The health halo effect of 'low sugar' and related claims on alcoholic drinks: an online experiment with young women. Alcohol Alcohol. 2022 doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agac054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H., et al. Presence and effects of health and nutrition-related (HNR) claims with benefit-seeking and risk-avoidance appeals in female-orientated magazine food advertisements. Int. J. Advert. 2013;32(4):587–616. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice Canada, 2021. Food and Drugs Act. 2021; Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/f-27/fulltext.html.

- Euromonitor International, 2021. Voice of the Industry: Alcoholic Drinks. 2021; Available from: https://www.euromonitor.com/voice-of-the-industry-alcoholic-drinks/report.

- Euromonitor International, 2022. Soft Drinks in Canada - Country Report. 2022; Available from: https://www.euromonitor.com/soft-drinks-in-canada/report.

- Euromonitor International, 2022. Carbonates in Canada - Country Report. 2022; Available from: https://www.euromonitor.com/carbonates-in-canada/report.

- Franco-Arellano B., et al. Assessing nutrition and other claims on food labels: a repeated cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian food supply. BMC Nutr. 2017;3:74. doi: 10.1186/s40795-017-0192-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada, 2019. Nutrition facts tables. 2019; Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/understanding-food-labels/nutrition-facts-tables.html.

- Government of Canada, 2020. Product specific information for beer. 2020; Available from: https://inspection.canada.ca/food-label-requirements/labelling/industry/alcohol/eng/1392909001375/1392909133296?chap=9.

- Government of Canada, 2020. Voluntary claims & statements - Alcoholic beverages. 2020; Available from: https://inspection.canada.ca/food-label-requirements/labelling/industry/alcohol/eng/1392909001375/1392909133296?chap=8#s7c8.

- Government of Canada, 2021. Energy and calorie claims. 2021; Available from: https://inspection.canada.ca/food-label-requirements/labelling/industry/nutrient-content/specific-claim-requirements/eng/1389907770176/1389907817577?chap=2.

- Government of Canada, 2021. Carbohydrate and sugars claims. 2021; Available from: https://inspection.canada.ca/food-label-requirements/labelling/industry/nutrient-content/specific-claim-requirements/eng/1389907770176/1389907817577?chap=11.

- Government of Canada, 2021. Low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines. 2021; Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/alcohol/low-risk-alcohol-drinking-guidelines.html.

- Government of Canada, 2022. Labelling requirements for alcoholic beverages. 2022; Available from: https://inspection.canada.ca/food-labels/labelling/industry/alcoholic-beverages/eng/1624281662154/1624281662623.

- Government of Québec, 2018. Act Respecting Liquor Permits. 2018; Available from: http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cs/p-9.1.

- Hall M.G., et al. The impact of front-of-package claims, fruit images, and health warnings on consumers' perceptions of sugar-sweetened fruit drinks: Three randomized experiments. Prev. Med. 2020;132 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.105998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes A., et al. Health-oriented marketing on alcoholic drinks: an online audit and comparison of nutrition content of Australian Products. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2022;83(5):750–759. doi: 10.15288/jsad.21-00356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobin E., et al. Efficacy of calorie labelling for alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages on restaurant menus on noticing information, calorie knowledge, and perceived and actual influence on hypothetical beverage orders: a randomized trial. Can. J. Public Health. 2022;113(3):363–373. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00599-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckle T., et al. Ready to drinks are associated with heavier drinking patterns among young females. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(4):398–403. doi: 10.1080/09595230802093802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur A., Scarborough P., Rayner M. A systematic review, and meta-analyses, of the impact of health-related claims on dietary choices. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017;14(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0548-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keric D., Myers G., Stafford J. Health halo or genuine product development: are better-for-you alcohol products actually healthier? Health Promot. J. Austr. 2021 doi: 10.1002/hpja.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keric D., Stafford J. Proliferation of 'healthy' alcohol products in Australia: implications for policy. Public Health Res Pract. 2019;29(3) doi: 10.17061/phrp28231808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersbergen I., Field M. Alcohol consumers' attention to warning labels and brand information on alcohol packaging: findings from cross-sectional and experimental studies. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MarketLine, 2018a. Key Trends in Alcoholic Beverages: Powerful changes shaping the wine, beer, spirits and alcohol-free beverages industry. 2018; [p.2]. Available from: https://store.marketline.com/report/key-trends-in-alcoholic-beverages-powerful-changes-shaping-the-wine-beer-spirits-and-alcohol-free-beverages-industry/.

- MarketLine, 2018b. Key Trends in Non-Alcoholic Beverages: Powerful changes shaping the soft drinks, hot drinks, enhanced water and packaging segment. 2018; [p.2]. Available from: https://store.marketline.com/report/key-trends-in-non-alcoholic-beverages-powerful-changes-shaping-the-soft-drinks-hot-drinks-enhanced-water-and-packaging-segment/.

- Miller P.G., et al. The growing popularity of “low-carb” beers: good marketing or community health risk? Med. J. Aust. 2010;192(4):235. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministère du Travail, d.l.E.e.d.l.S.s., 1979. Act respecting offences relating to alcoholic beverages. 1979; Available from: http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/document/cs/I-8.1.

- Mosher J.F., Johnsson D. Flavored alcoholic beverages: an international marketing campaign that targets youth. J. Public Health Policy. 2005;26(3):326–342. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, C., Butt, P., Shield, K., Poole, N., Wells, S., Naimi, T., Sherk, A. Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction 2023; Available from: https://ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2023-01/CCSA_Canadas_Guidance_on_Alcohol_and_Health_Final_Report_en.pdf.

- Public Health Advocacy Institute of Western Australia and Cancer Council Western Australia, 2019. How alcohol is marketed to women in Australia. 2019; Available from: https://eucam.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/PHAIWA-CCWA-The-Instagrammability-of-pink-drinks-How-alcohol-is-marketed-to-women-in-Australia-2019.pdf.

- Robinson E., Humphreys G., Jones A. Alcohol, calories, and obesity: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of consumer knowledge, support, and behavioral effects of energy labeling on alcoholic drinks. Obes. Rev. 2021;22(6):e13198. doi: 10.1111/obr.13198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumgay H., et al. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(8):1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherk A., et al. Calorie intake from alcohol in Canada: why new labelling requirements are necessary. Can. J. Diet Pract. Res. 2019;80(3):111–115. doi: 10.3148/cjdpr-2018-046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada, 2021. Control and sale of alcoholic beverages, year ending March 31, 2020. 2021; Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210421/dq210421b-eng.htm.

- Vergeer L., et al. Vegetarianism and other eating practices among youth and young adults in major Canadian cities. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(4):609–619. doi: 10.1017/S136898001900288X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2018. Global status report on alcohol and health.

- World Health Organization, 2021. Global alcohol action plan 2022-2030 to strengthen implementation of the Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol. 2021; [p.19]. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/alcohol/alcohol-action-plan/first-draft/global_alcohol_acion_plan_first-draft_july_2021.pdf?sfvrsn=fcdab456_3&download=true.

- Zhao J., et al. The Effects of alcohol warning labels on population alcohol consumption: an interrupted time series analysis of Alcohol Sales in Yukon, Canada. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2020;81(2):225–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.