Abstract

Candida albicans is both a commensal and a pathogen at the oral mucosa. Although an intricate network of host defense mechanisms are expected for protection against oropharyngeal candidiasis, anti-Candida host defense mechanisms at the oral mucosa are poorly understood. Our laboratory recently showed that primary epithelial cells from human oral mucosa, as well as an oral epithelial cell line, inhibit the growth of blastoconidia and/or hyphal phases of several Candida species in vitro with a requirement for cell contact and with no demonstrable role for soluble factors. In the present study, we show that oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity is resistant to gamma-irradiation and is not mediated by phagocytosis, nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, and superoxide oxidative inhibitory pathways or by nonoxidative components such as soluble defensin and calprotectin peptides. In contrast, epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity was sensitive to heat, paraformaldehyde fixation, and detergents, but these treatments were accompanied by a significant loss in epithelial cell viability. Treatments that removed existing membrane protein or lipid moieties in the presence or absence of protein synthesis inhibitors had no effect on epithelial cell inhibitory activity. In contrast, the epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity was abrogated after treatment of the epithelial cells with periodic acid, suggesting a role for carbohydrates. Adherence of C. albicans to oral epithelial cells was unaffected, indicating that the carbohydrate moiety is exclusively associated with the growth inhibition activity. Subsequent studies that evaluated specific membrane carbohydrate moieties, however, showed no role for sulfated polysaccharides, sialic acid residues, or glucose- and mannose-containing carbohydrates. These results suggest that oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity occurs exclusively with viable epithelial cells through contact with C. albicans by an as-yet-undefined carbohydrate moiety.

Mucosal candidiasis is a significant problem in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, especially those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (34, 39). The majority of episodes of mucosal candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans, a dimorphic fungal organism of the gastrointestinal and lower female reproductive tracts. As a commensal, C. albicans asymptomatically colonizes epithelial surfaces. Although both the oral and the vaginal mucosa are normally colonized with C. albicans, the oral mucosa is colonized at higher rates (up to 65% of normal healthy individuals versus 5 to 25% of healthy women colonized vaginally) (28, 52). Clinical observations show that symptomatic oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) is often a manifestation of corticosteroid therapy (35), immunosuppression after transplantation (7), and AIDS (34, 39). In contrast, OPC in healthy individuals is relatively rare.

Host defense mechanisms against mucosal candidiasis are poorly understood. Although cell-mediated immunity is considered an important host defense mechanism against mucosal and/or systemic candidiasis (4, 5), the role of systemic cell-mediated immunity against vaginal (20, 21, 22, 23, 58) and, more recently, oral (37) candidiasis has been challenged to various degrees. Likewise, the role of antibodies and innate resistance against oral and vaginal candidiasis is largely unknown and/or controversial (3, 11, 19, 55). Recently, our laboratory reported that primary epithelial cells from murine, nonhuman primate, and human vaginal mucosa (18, 55, 56) and human oral mucosa (54) significantly inhibited the growth of C. albicans in vitro at relatively low effector/target cell (E:T) ratios of 10:1 to 1:1, with oral epithelial cells having significantly greater activity (∼80% versus ∼50% growth inhibition). Additional studies demonstrated that for both vaginal and oral epithelial cell activity, soluble factors collected from epithelial cell-Candida cocultures could not replace the cellular requirement, and cell contact was a strict requirement for activity (54). Subsequent studies with oral epithelial cells showed a wide spectrum of anti-Candida activity against blastoconidia and/or hyphal phases of C. albicans, as well as activity against several Candida species (54). Additionally, oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity was significantly reduced in HIV-positive persons with OPC (54).

In addition to our observations, epithelial cells have recently been recognized as playing active roles in mucosal immune responses. Epithelial cells of the reproductive and gastrointestinal tracts have been shown to express major histocompatibility complex class II molecules and process and present protein antigens to T cells (26, 27, 62). In addition to antigen presentation for T-cell activation, epithelial cells secrete a variety of cytokines and chemokines in response to pathogens that may affect local immune responses (29). Finally, epithelial cells produce a variety of antimicrobial peptides such as defensins, histatins, and calprotectin (2, 60, 63). The purpose of the present study was to further examine characteristics by which oral epithelial cells exert their anti-Candida activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants.

Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and all procedures in the clinical research were carried out in accordance with guidelines of the Institutional Review Board at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, La. Specimens were collected exclusively from healthy volunteers.

Epithelial cell isolation.

Epithelial cells were isolated as previously described (54). Briefly, 10 ml of unstimulated saliva from each participant was expectorated into a sterile polypropylene centrifuge tube. The sample was processed by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min, and the clarified soluble fraction was stored at −70°C. After being washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cell pellet was resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) and passed over a 20-μm-pore-size sterile nylon membrane (Small Parts, Inc., Miami Lakes, Fla.). The epithelial cell-enriched population collected from the membrane was washed, resuspended in cryopreservative (50% fetal bovine serum, 25% RPMI 1640 tissue culture medium, 15% dimethyl sulfoxide), and stored at −70°C until use. Epithelial cells were confirmed by hematoxylin and eosin staining as previously described (55).

Human epithelial cell line.

A human epithelial cell line (KB, catalog no. CCL-17; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) was used. The KB cell line was initially derived from an epidermoid carcinoma in the oral mucosa of an adult male. However, recent reports have shown that KB cells are contaminated with HeLa cells, a human cervical epithelial cell line. Since the contaminating HeLa cells are epithelial in origin, we used the KB-HeLa cell line as a purified epithelial cell population. KB cells were maintained in 90% minimum essential Eagle medium with nonessential amino acids and Earle's balanced salt solution (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and also 1% penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (both from Life Technologies), at 37°C in 10% CO2 and passaged every 3 to 4 days.

Target cells.

C. albicans 3153A was from the National Collection of Pathogenic Fungi (London, United Kingdom). The isolate was grown on Sabouraud-dextrose agar (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) at 30°C, and one colony was used to inoculate 10 ml of Phytone-Peptone (PP) broth (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 0.1% glucose. Broth cultures were grown to stationary phase for 18 h at 25°C in a shaking water bath. The blastoconidia were collected, washed with PBS, and enumerated on a hemacytometer by using trypan blue dye exclusion.

Growth inhibition assay.

A [3H]glucose uptake assay was employed as previously described (54, 55). Briefly, stationary-phase blastoconidia were added to individual wells of a 96-well microtiter plate at 105 cells/ml in a volume of 100 μl of PP supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Epithelial enriched cells were then added at various E:T ratios in a volume of 100 μl of PP. The cultures were incubated for 9 h at 37°C in 10% CO2 in the presence of 1 μCi of [3H]glucose (ICN, Costa Mesa, Calif.). Controls included Candida and effector cells cultured alone. Thereafter, 100 μl of sodium hypochlorite solution was added to all wells for 5 min, and the cell extracts were harvested onto glass fiber filters by using a PHD Cell Harvester (Cambridge Technologies, Watertown, Mass.). The incorporated [3H]glucose was then measured by liquid scintillation. The incorporation of glucose by Candida and primary epithelial cells during the 9 h assay was generally 30,000 to 40,000 cpm and 1,000 to 5,000 cpm, respectively, and 300 to 2,000 cpm for the KB line cells. The percent growth inhibition was calculated as follows: % growth inhibition = 1 − [(mean experimental cpm − mean effector cell cpm)/mean Candida cpm] × 100.

In specific experiments, a quantitative plate count method was also employed to monitor the growth inhibition of C. albicans (54, 55). Briefly, similar effector-target cocultures were prepared in duplicate without [3H]glucose and incubated at 37°C in 10% CO2 for 9 h. Thereafter, 100 μl of 0.3% Triton X-100 was added to all wells (for Candida removal), and samples of these cultures were then serially diluted (1:10) and plated onto Sabouraud-dextrose agar. CFU counts were determined after 48 h at 30°C. Controls for these studies included cultures and plating of effector cells and C. albicans alone. The percent growth inhibition was calculated as follows: % growth inhibition = 1 − (experimental CFU/Candida CFU) × 100.

Analysis of phagocytosis. The growth inhibition assay was performed in the presence and absence of [3H]glucose. After 9 h, aliquots from nonradioactive epithelial cell/Candida cocultures, effector control wells, and target control wells were collected and cytospun onto slides. The slides were stained with 1% diaethanol (for fluorescent labeling of Candida) (a kind gift from Stuart Levitz, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Mass.) for 1 min at room temperature, washed, and then counterstained with 0.4% trypan blue (Sigma) (38). Coverslips were mounted to each slide for view under fluorescent microscopy. Radioactive cultures were harvested at 9 h and served as a control for anti-Candida activity.

In specific experiments, phagocytosis was evaluated by pretreating the epithelial cells with cytochalasin D, which functions to inhibit microfilament and/or actin tubule formation. For this, epithelial cells were incubated with cytochalasin D (1.2 to 24.0 μM, 25 min at 37°C) (24). Initial concentrations were based on published reports for other cells (24); additional concentrations were used when no effects were observed. Controls included epithelial cells incubated in PBS alone. Thereafter, cells were washed three times with PBS, enumerated, and added to the Candida samples in the [3H]glucose uptake assay.

Examination of oxidative and nonoxidative mechanisms for epithelial cell anti-Candida activity.

To examine oxidative inhibitory pathways, the [3H]glucose uptake assay was performed in the presence of 1 to 3 mM Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; Sigma), 3 × 103 to 2 × 104 U of catalase (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.)/ml, or 6 × 102 to 4.8 × 103 U of superoxide dismutase (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.)/ml. l-NAME, catalase, and superoxide dismutase inhibit nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, and oxygen radicals, respectively (12). Initial concentrations were based on published reports using epithelial cell lines (12); additional concentrations were used when no effect was observed. Controls included conducting the growth inhibition assay in tissue culture medium (PP) without inhibitors. The concentrations of each compound or enzyme alone demonstrated no effect on Candida growth (measured by [3H]glucose uptake).

The nonoxidative mechanisms evaluated included soluble calprotectin and defensins (36, 53). Calprotectin was evaluated by performing the [3H]glucose assay in the presence of 30 μM ZnSO4 (Sigma), which chelates calprotectin (53). Defensins were evaluated by performing the [3H]glucose assay in the presence of Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PP (divalent cations inhibit defensins) (36). Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PP was prepared by incubating PP with Chelex 100 analytical ion-exchange resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) for 1 h at room temperature. The resin was removed thereafter by sterile filtration.

Epithelial cellular treatments.

For physical treatments, epithelial cells were placed in a shaking water bath for 30 min at 60°C (heat inactivation), pretreated with paraformaldehyde (1%, 10 min at room temperature), or gamma-irradiated (1,000 to 4,000 rads) by using a 137Cs source gamma-irradiator. Controls included untreated epithelial cells. The cells were washed three times with PBS, enumerated, and added to the [3H]glucose uptake assay.

For examination of general membrane-associated moieties, epithelial cells were pretreated with detergents, including sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; 1%; 30 s at room temperature) (1) and Nonidet P-40 (NP-40; 1%; 30 min at room temperature) (25, 49) (both from Sigma) in a volume of 1 ml. For analysis of existing membrane-associated protein moieties, epithelial cells were pretreated with proteinase K (50 to 250 μg/ml, 10 min at 37°C) (41) (Roche Corp., Mannheim, Germany) in a volume of 1 ml of PBS in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (for inhibition of de novo protein synthesis [1 to 100 μg/ml, 60 min at 37°C]) (43). Initial concentrations of each reagent were based on published reports for other cells (1, 25, 41, 43, 49); additional concentrations were used when no effects were observed. Controls included epithelial cells incubated in PBS alone. Thereafter, cells were washed three times with PBS, enumerated, and added to Candida in the [3H]glucose uptake assay. To confirm the action of each reagent, supernatants from each epithelial cell treatment and the respective PBS-treated control were collected and assayed for total protein. Briefly, bicinchoninic acid reagent A (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) was added to undiluted and diluted supernatants and standards (2,000 μg/ml of bovine serum albumin serially diluted 1:2) for 30 min at 65°C. Thereafter, the absorbance values were determined at 595 nm by using a Ceres 900 automated microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Wisnooski, Vt.) and Kineticalc software (Bio-Tek).

For examination of lipid moieties, epithelial cells were pretreated with phospholipase A2 (PLA2; 5 to 50 U/ml, 30 min at 37°C; Sigma) (8, 45) in a volume of 1 ml of PBS. To confirm PLA2 enzymatic activity, PLA2 was incubated with autoclaved [14C]oleic acid-labeled Escherichia coli (a kind gift from Richard O'Callaghan, Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Parasitology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans) for 1 h at 37°C (17). The reaction was stopped with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma), the samples were centrifuged, and the products of hydrolysis (free [14C]oleic acid) released into the supernatant were quantified by liquid scintillation.

For examination of carbohydrate moieties, epithelial cells were pretreated with periodic acid (5 mM, 10 min at 37°C) (31, 44, 57) and a series of specific carbohydrate-removing enzymes, either separately or in combination, including heparinase, heparitinase, chondroitinase (2 to 10 U/ml, 60 min at 37°C for all), PNGase F (0.05 to 0.2 U/ml, 30 min at 37°C) (all from Sigma) (33, 64), alpha-glucosidase (50 to 150 U/ml, 10 min at 37°C; Roche Corp, Mannheim, Germany) (46), mannosidase (10 to 50 U/ml, 30 min at 37°C; Sigma) (50), and/or neuraminidase (0.5 to 2.5 U/ml, 60 min at 37°C; Sigma) (42). Initial concentrations were based on published reports for other cells (33, 42, 46, 50, 64); additional concentrations were used when no effects were observed. Controls included epithelial cells incubated in PBS alone. Thereafter, cells were washed three times with PBS, enumerated, and added to Candida in the [3H]glucose uptake assay. In experiments with periodic acid pretreatments, initial experiments indicated that, although periodic acid pretreatment had no effect on epithelial cell viability, [3H]glucose uptake by epithelial cells was affected, potentially creating false interpretations. Therefore, quantitative plate count analysis was performed to measure growth inhibition activity. Previous parallel analyses have shown no differences in the percent growth inhibition between quantitative plate count analysis and the [3H]glucose uptake assay (54). To confirm the effects of each carbohydrate enzyme pretreatment, supernatants from each treatment were collected and assayed for total carbohydrate content (15). Briefly, 25 μl of 80% phenol and 2.5 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid (both from Sigma) were added to undiluted and diluted supernatants and standards (250 μg/ml of mannose serially diluted 1:2) for 20 min at room temperature. Thereafter, the absorbance values were determined at 490 nm by using a Ceres 900 automated microplate reader (Bio-Tek).

Adherence assay.

A modified adherence assay was performed (51, 61). Briefly, epithelial cells (105 cells/ml) were added after periodic acid pretreatment to C. albicans (107 cells/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Controls included PBS-treated epithelial cells. Thereafter, the coculture was centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 s, and the supernatant was discarded. The epithelial cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of PBS and passed over a sterile 10-μm-pore-size nylon membrane. The epithelial cells retained on the membrane were collected and centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 s, and aliquots of the epithelial cell pellet were viewed microscopically.

Assessment of epithelial cell viability.

After all epithelial cell treatments, epithelial cell viability was assessed by trypan blue dye exclusion before addition of the cells to the culture wells for the growth inhibition assay.

Statistical analysis.

The unpaired Student t test was used to analyze data. Significant differences were defined at a confidence level where P was <0.05.

RESULTS

Role of oxidative and nonoxidative inhibitory pathways and epithelial cell anti-Candida activity.

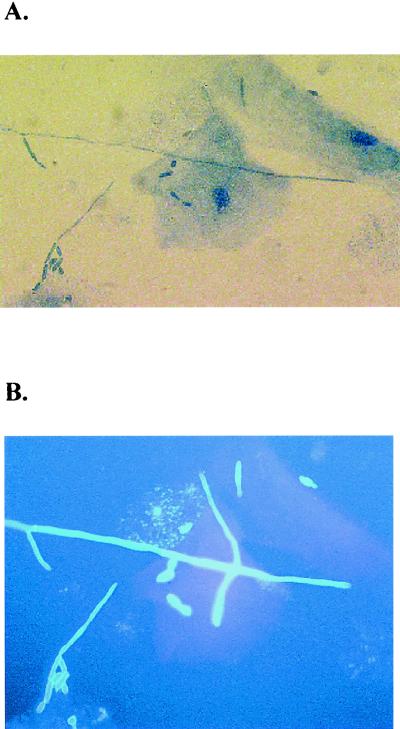

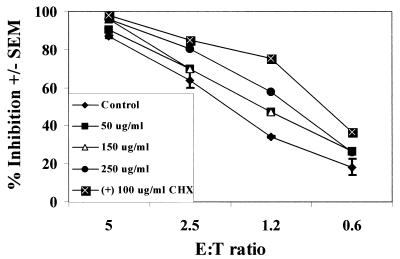

Based on our previous observation that cell contact was required for epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity (54), we first asked whether phagocytosis and/or inhibition by oxidative mechanisms occurred during the inhibition activity. For evaluation of phagocytosis, epithelial cells in the cocultures were examined for internalized Candida by fluorescent staining. The results illustrated in Fig. 1 show that all C. albicans blastoconidia and hyphae associated with the epithelial cells observed under light microscopy also fluoresced under fluorescent microscopy and thus were considered external to the epithelial cells. We further investigated whether epithelial cells phagocytize C. albicans by pretreating the epithelial cells with cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of microfilament formation. The results showed no difference in anti-Candida activity by cytochalasin D-treated cells compared to those treated with PBS (at an E:T ratio of 5:1, 94.4% versus 95.1% inhibition for PBS- versus cytochalsin D-treated epithelial cells, respectively). Despite this lack of phagocytosis, previous reports have shown that epithelial cells exert bactericidal activity through oxidative mechanisms (12). To address this, [3H]glucose uptake assays were performed in the presence of several concentrations of inhibitors of nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, and oxygen radicals. Compared to controls, the presence of l-NAME (nitric oxide inhibitor), catalase (hydrogen peroxide inhibitor), or superoxide dismutase (oxygen radical inhibitor) had no effect on anti-Candida activity by primary oral epithelial cells (at an E:T ratio of 5:1, 89.3% ± 4.3% inhibition for controls, 84.4% ± 6.2% inhibition for l-NAME, 88.2% ± 11.5% inhibition for catalase, and 85.7% ± 13.7% inhibition for superoxide dismutase). Similar results were observed with the epithelial cell line (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

No evidence of phagocytosis in oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. Whole unstimulated saliva was collected from healthy human volunteers (n = 3), and epithelial cell-enriched populations were isolated by nylon membrane retention. Enriched epithelial cells were then examined for in vitro growth inhibition of C. albicans. Aliquots from nonradioactive cultures were cytospun onto slides and stained with 1% diaethanol for analysis of phagocytosis. The figure illustrates a representative preparation viewed under light (A) and fluorescent (B) microscopy. Magnification, ×400.

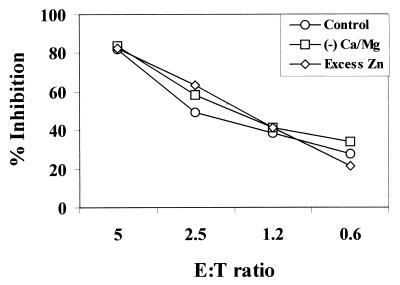

Although we previously found that soluble factors could not replace the requirement for cell contact (54), the possibility that soluble factors contributed to the inhibitory activity exclusively in the presence of cell contact by some nonoxidative mechanism could not be eliminated. Defensins and calprotectin, small antimicrobial peptides, are potent epithelial cell-derived anti-Candida compounds (36, 53). Since defensins may be inhibited by low concentrations of divalent cations (Ca2+-Mg2+), their function can easily be identified by increased inhibitory activity under divalent cation-free culture conditions. In contrast, calprotectin can be identified by reducing inhibitory activity in the presence of excess Zn2+ that replaces the zinc (required for Candida growth) chelated by calprotectin. However, the results illustrated in Fig. 2 show no effect, either positively or negatively, on epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. Similar results were observed with the epithelial cell line at each E:T ratio (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

No evidence for nonoxidative soluble factors in oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. Whole unstimulated saliva was collected from healthy human volunteers (n = 3), and epithelial-enriched populations were isolated by nylon membrane retention. Enriched epithelial cells were then examined for in vitro growth inhibition of C. albicans in medium containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ (control), Ca2+- and Mg2+-free medium (for evaluation of defensins), and medium containing excess Zn2+ (for evaluation of calprotectin). The figure shows representative results from three separate experiments.

Physical characteristics of epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity.

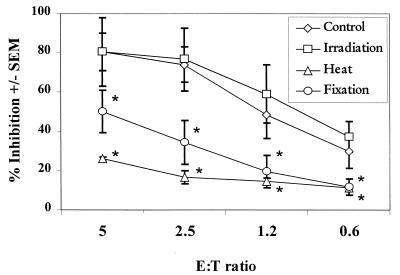

To address the physical characteristics of the oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity, epithelial cells were subjected to gamma-irradiation, fixation, and heat and then evaluated for growth inhibition of C. albicans. The results presented in Fig. 3 show that epithelial cells that were fixed with paraformaldehyde or subjected to heat resulted in a significant decrease in anti-Candida activity at all of the E:T ratios examined (P < 0.05). Further studies revealed that heat and fixation resulted in a loss of epithelial cell viability (>80% viability for controls versus <10% and <30% viabilities for heat and fixation, respectively). In contrast, growth inhibition activity by the epithelial cells was unaffected by as much as 4,000 rads of gamma-irradiation. Epithelial cell viability was not affected by this level of radiation. Similar results were observed when we used the epithelial cell line (at an E:T ratio of 10:1, 46.6% ± 7.0% inhibition was observed for controls, 49.2% ± 6.5% inhibition occurred for irradiation, 10.7% ± 2.0% inhibition occurred for heat [P < 0.0005], and 20.7% ± 2.7% inhibition occurred for fixation [P < 0.014]), with a similar pattern of loss in cell viability.

FIG. 3.

Physical characteristics of oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. Whole unstimulated saliva was collected from healthy human volunteers (n = 3), and epithelial cell-enriched populations were isolated by nylon membrane retention. Enriched epithelial cells were pretreated with various doses of gamma-irradiation, 1% paraformaldehyde, or heat (65°C) and then washed and examined for in vitro growth inhibition of C. albicans by measuring [3H]glucose uptake. The figure shows cumulative results (mean % inhibition ± the standard error of the mean [SEM]). Asterisks represent significant differences compared to controls (P < 0.05).

Role of membrane moieties in epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity.

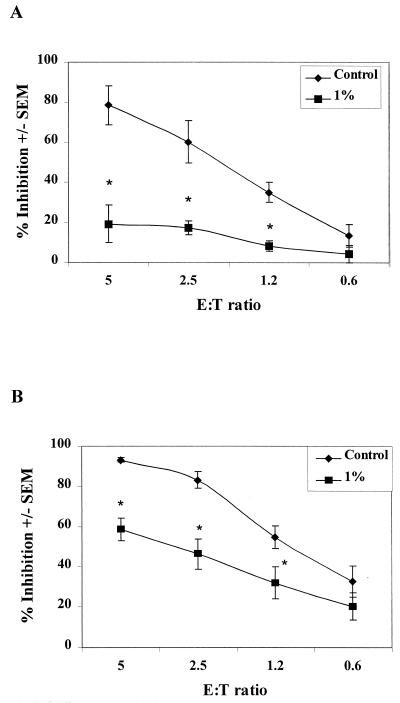

To examine general membrane-associated moieties, epithelial cells were pretreated with SDS and NP-40, which both function to disrupt cell membranes, resulting in protein and carbohydrate solubilization and/or release. The total protein concentrations in supernatants after each treatment were as follows: SDS, 136.1 ± 65.6 μg/ml versus 29 ± 13.5 μg/ml for PBS-treated cells; NP-40, 314.6 ± 69.7 μg/ml versus 66.4 ± 22.5 μg/ml for PBS-treated cells. The detergent-treated epithelial cells, along with epithelial cells incubated in PBS alone as a control, were evaluated in the growth inhibition assay. Figure 4 shows that the epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity was significantly reduced after each detergent treatment (for SDS at E:T ratios of 5, 2.5, and 1.2:1, P < 0.006, 0.009, and 0.005, respectively; for NP-40, P < 0.01, 0.007, and 0.04, respectively). Additional studies revealed that the detergent treatment, while not affecting cellular integrity, significantly reduced cell viability (>80% viability before treatment versus <10% viability after treatment). Similar results were observed with the epithelial cell line (at an E:T ratio of 10:1, 0% inhibition was observed for both SDS and NP-40), together with a similar loss of cell viability (>80% viability before treatment versus <20% viability after treatment).

FIG. 4.

Protein moieties are not involved in oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. Whole unstimulated saliva was collected from healthy human volunteers (n = 3), and epithelial cell-enriched populations were isolated by nylon membrane retention. Enriched epithelial cells were pretreated with SDS (A) and NP-40 (B). Thereafter, cells were washed and examined for in vitro growth inhibition of C. albicans by measuring [3H]glucose uptake. The figure shows show cumulative results (mean % inhibition ± the SEM). Asterisks represent significant differences compared to controls (P < 0.05).

Since detergent treatment resulted in a significant loss of epithelial cell viability, we could not predict roles for protein, lipid, or carbohydrate moieties in the inhibitory activity. For assessment of protein moieties, epithelial cells were pretreated with proteinase K (nonspecific protein cleavage) in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (inhibition of de novo protein synthesis) and examined for anti-Candida activity. Total protein concentrations in supernatants from epithelial cells treated with proteinase K were 1,150.0 ± 117.1 μg/ml versus 140.1 ± 7.6 μg/ml for PBS-treated cells. Proteinase K had no effect on epithelial cell viability. The results shown in Fig. 5 show that proteinase K treatment in the presence or absence of cycloheximide had no effect on oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. Similar results were observed with the epithelial cell line (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

No role of membrane protein moieties in oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. Whole unstimulated saliva was collected from healthy human volunteers (n = 3), and epithelial cell-enriched populations were isolated by nylon membrane retention. Enriched epithelial cells were pretreated with various concentrations of proteinase K in the presence or absence of cycloheximide. Thereafter, cells were washed and examined for in vitro growth inhibition of C. albicans by [3H]glucose uptake. The figure shows representative results for three separate concentrations of proteinase K, proteinase K (250 μg/ml) in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX; 100 μg/ml), and cumulative results of controls for each concentration of proteinase K employed (mean % inhibition ± the SEM).

To assess the potential role of lipids in epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity, epithelial cells were pretreated with PLA2 (which cleaves phospholipid moieties). PLA2 activity was confirmed through release of autoclaved [14C]oleic acid-labeled Escherichia coli (1,621 ± 422 cpm) compared to controls (353 ± 153 cpm). The results showed that PLA2 had no effect on epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity (for an E:T ratio of 5:1, 68.7% ± 4.3% inhibition observed for controls versus 57.7, 66.5, and 67.6% inhibition for 5, 20, and 50 U/ml, respectively) or epithelial cell viability.

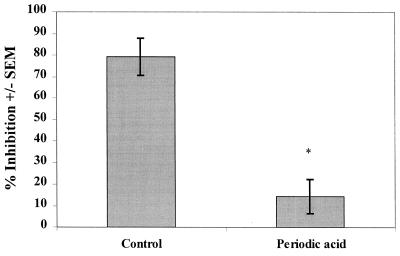

To address the role of membrane carbohydrates, epithelial cells were pretreated first with periodic acid to remove any carbohydrate moiety. Total carbohydrate concentration in supernatants after periodic acid treatment was 21 ± 3.9 μg/ml versus 1.7 ± 1.0 μg/ml for PBS-treated control cells. The results shown in Fig. 6 indicate a significant decrease in anti-Candida activity by periodic acid-treated epithelial cells (P < 0.0007). There was no demonstrable effect of periodic acid on epithelial cell viability. Results from the epithelial cell line showed similar results (83% inhibition for PBS-treated cells versus 17% inhibition for periodic acid-treated cells that had a 18-fold release of carbohydrate into the supernatant posttreatment). Other studies investigated whether carbohydrates removed from the epithelial cell surface alone had inhibitory activity. The results showed that neutralized supernatants collected from periodic acid-treated cells did not inhibit the growth of C. albicans.

FIG. 6.

Role of membrane carbohydrate moieties in oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. Whole unstimulated saliva was collected from healthy human volunteers (n = 3), and epithelial cell-enriched populations were isolated by nylon membrane retention. Enriched epithelial cells were pretreated with periodic acid and thereafter washed and examined for in vitro growth inhibition of C. albicans by quantitative plate counts. The figure shows cumulative results (mean % inhibition ± the SEM) at an E:T ratio of 5:1. Asterisks represent significant differences compared to controls (P < 0.05).

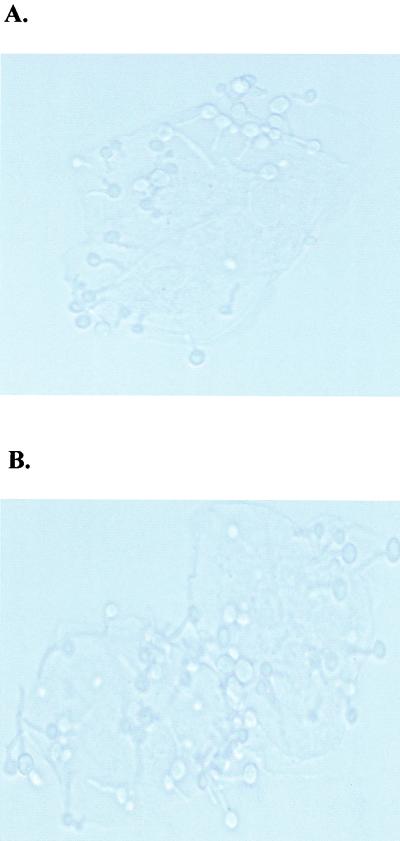

To address the role of whether the reduction in growth inhibition activity by periodic acid-treated epithelial cells was associated with a reduction in adherence, we examined the adherence of C. albicans to the treated epithelial cells. The results illustrated in Fig. 7 show that the adherence of C. albicans to periodic acid-treated epithelial cells was virtually identical (per cell) to their adherence to PBS-treated epithelial cells. In a parallel assay to control for the function of the treated cells, periodic acid-treated epithelial cells inhibited 50% C. albicans growth versus 90% inhibition by PBS-treated cells.

FIG. 7.

Periodic acid treatment of epithelial cells does not affect adherence to C. albicans. Whole unstimulated saliva was collected from healthy human volunteers (n = 3), and epithelial cell-enriched populations were isolated by nylon membrane retention. Enriched epithelial cells were pretreated with periodic acid and then washed and examined for adherence to oral epithelial cells by using a standard adherence assay. The figure shows a representative preparation of PBS-treated cells (A) and periodic acid-treated cells (B) viewed under light microscopy. Magnification, ×400.

To address the role of specific membrane carbohydrate moieties, epithelial cells were pretreated with heparinase, heparitinase, and chondroitinase for the removal of sulfated polysaccharides, neuraminidase for the removal of sialic acid residues, and alpha-glucosidase and mannosidase for the removal of glucose- and mannose-containing carbohydrates and with PNGase F for the removal of asparagine-linked carbohydrate moieties. Total carbohydrate concentrations after heparinase, heparitinase, chondroitinase, alpha-glucosidase, mannosidase, and neuraminidase treatment were 6.7 ± 1.0, 6.4 ± 0.8, 14 ± 2.8, 385.5 ± 164.5, 13.8 ± 4.7, and 21.9 ± 21.0 μg/ml, respectively, versus 6.3 ± 0.6 μg/ml for PBS-treated control cells. PNGase F was the only enzyme that did not release any measurable carbohydrate from the cell surface. Since only chondroitinase, alpha-glucosidase, mannosidase, and neuraminidase treatment resulted in significant elicitation of carbohydrates into the culture supernatants, chondroitinase-, alpha-glucosidase-, mannosidase-, and neuraminidase-treated epithelial cells were subsequently evaluated in the growth inhibition assay. Results showed that removal of each type of carbohydrate moiety alone had no effect on the epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity (for an E:T ratio of 5:1, we found 75.8% ± 3.4%, 78.2% ± 4.2%, 90.1% ± 1.3%, 75.1% ± 8.1%, and 77.3% ± 8.1% inhibition for PBS-, chondroitinase-, alpha-glucosidase-, mannosidase-, and neuraminidase-treated epithelial cells, respectively). Similar results were observed with the epithelial cell line (data not shown). Additional studies that examined the combination of all of the above mentioned carbohydrate-specific enzymes also showed no effect on the anti-Candida activity.

DISCUSSION

Previous results from our laboratory showed that oral epithelial cells possessed potent in vitro inhibitory activity against both morphological phases of several Candida species. Further studies found that the inhibitory activity was strictly dependent on cell contact (54). The present study aimed to characterize the properties of this anti-Candida activity so as to gain a better understanding of this potentially important innate host defense mechanism. We first examined whether phagocytosis and oxidative mechanisms were involved in the epithelial cell activity. Some reports have shown that epithelial cells phagocytize C. albicans (14), while others have shown that epithelial cells are unable to phagocytize particles greater than 1.0 μm in diameter (32), which is approximately half the size of the blastoconidia form of C. albicans. Our studies found no evidence of phagocytosis. Furthermore, the lack of observable phagocytosis was consistent with the lack of effects of cytochalasin D treatment, as well as the lack of any evidence for oxidative killing by the epithelial cells.

With respect to nonoxidative mechanisms, although previous studies indicated that soluble factors alone could not replace the requirement for cell contact in the epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity, we could not rule out some role for soluble factors against Candida in the direct presence of cell contact. Accordingly, we tested for possible roles of calprotectin and defensins, two antimicrobial peptides common to epithelial cells with known antifungal activity. However, we found no evidence that either played a role in the epithelial cell-mediated inhibitory activity against Candida. Although it remains possible that other nonoxidative soluble factors play a role in the epithelial cell-mediated inhibitory process, calprotectin and defensins were considered the most likely candidates based on their presence at the oral mucosa (6, 48) and the fact that they are derived from epithelial cells (2, 60). Current studies are under way to evaluate other nonoxidative soluble factors.

Further studies focusing specifically on the physical limitations of the oral epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity showed that, although the anti-Candida activity was resistant to gamma-irradiation, both heat and fixation abrogated the anti-Candida activity. Heat is often employed to degrade proteins and other membrane constituents, and fixation techniques are often used to preserve cells by cross-linking membrane moieties. Thus, our results initially indicated that the epithelial cell-mediated growth inhibition activity may involve a membrane-associated moiety sensitive to such degradation or cross-linking. However, both heat and fixation also resulted in a considerable loss in epithelial cell viability, which alone may have affected anti-Candida activity.

Subsequent studies have therefore evaluated the role of the epithelial cell membrane moieties in the anti-Candida activity. These studies began by evaluating the effects of two commonly used detergents, SDS and NP-40, which remove membrane constituents by binding to and cleaving internal hydrophobic moieties of the cell membrane. Both detergent treatments resulted in significant cleavage of membrane proteins and a significant decrease in anti-Candida activity. However, as with heat and fixation, these detergent treatments also resulted in a loss of epithelial cell viability despite the fact that cellular integrity was maintained. A second series of studies investigated the effects of proteinase K, an enzyme which exhibits no protein cleavage specificity and is considered to be the most active endopeptidase known. However, despite confirmation of proteinase K enzymatic activity at all concentrations examined, no effect on epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity was observed. Results did not differ in the added presence of cycloheximide. Importantly, neither proteinase K nor cycloheximide affected epithelial cell viability. Together, these results suggest that the epithelial cell inhibitory activity, while requiring cell contact, does not appear to involve a constitutively expressed or de novo-synthesized membrane protein moiety. However, it remains possible that higher concentrations of proteinase K and/or cycloheximide may be required to affect anti-Candida activity. A third series of studies investigated the role of lipids in the epithelial cell anti-Candida activity. Results demonstrated that pretreatment of the epithelial cells with several concentrations of PLA2 had no effect on anti-Candida activity. As with the proteinase K pretreatments, PLA2 had no effect on epithelial cell viability at all of the concentrations examined. Therefore, phospholipids affected by PLA2 enzymatic activity, including phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylinositol, do not appear to play a role in the epithelial cell anti-Candida activity. Although concentrations up to 10-fold above that recommended for other cells were employed and the enzyme was found to be active in a [14C]oleic acid release assay, which is similar to the protein experiments, we cannot exclude the remote possibility that yet higher concentrations of PLA2 would be required to hydrolyze phospholipids that may be critical for anti-Candida activity. Nevertheless, taken together, these results suggest that epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity is not mediated by a protein or lipid moiety and the abrogation of inhibitory activity observed with heat, fixation, and detergent treatments was most likely a direct result of the loss in epithelial cell viability.

A fourth series of studies evaluated the role of carbohydrate moieties. The abrogation of inhibitory activity after pretreatment of the epithelial cells with periodic acid, which oxidizes internal carbon-carbon bonds of carbohydrates to form aldehydes, suggested that the effector moiety on the primary oral epithelial cell membrane was of carbohydrate origin. This was further supported by similar results employing the epithelial cell line. In fact, all results from studies with the primary oral epithelial cells were confirmed by the epithelial cell line, thus providing additional support and confidence in the interpretations. Interestingly, C. albicans was capable of adhering to epithelial cells lacking the critical carbohydrate moiety(s) in a standard adherence assay. This is significant since these results suggest that the carbohydrate moiety truly functions to inhibit yeast growth rather than simply a loss or reduction in cell contact required for the epithelial cell anti-Candida activity.

Studies to identify a specific carbohydrate moiety showed no role for chondroitin sulfate-, glucose-, and mannose-associated residues and sialic acid residues in the epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity. The lack of release of carbohydrate moieties with PNGase F, heparinase, and heparitinase at concentrations at and above those recommended suggests that carbohydrates sensitive to these enzymes (asparagine-like moieties, heparin sulfate) are not present or are present at very low concentrations on primary oral epithelial cells. However, we again cannot exclude the possible requirement of higher enzyme concentrations to release such moieties. Another possibility is that several of these moieties contribute to the activity against Candida such that removal of any one does not affect the inhibitory activity. However, the likelihood of this possibility was reduced by the fact that a similar lack of effect on inhibitory activity was observed when all of the carbohydrate-specific enzymes were combined as one epithelial cell pretreatment. Current studies are under way to investigate additional membrane carbohydrate moieties.

Although our results did not identify one specific carbohydrate moiety responsible for the epithelial cell activity, the epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity, at the very least, requires contact with a carbohydrate on viable epithelial cells. Therefore, based on our data, binding of Candida to viable epithelial cells may be a mechanism by which overgrowth of Candida is controlled, with the remaining colonizing organisms detected as asymptomatic colonization. It is both interesting and intriguing that a carbohydrate moiety is involved in the epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity and not a protein that is more commonly involved in receptor-mediated events. However, studies show that mannose receptors, as well as inflammatory mediators, have been implicated in anti-Candida activity by several kinds of epidermal cells (10, 13). Clearly, the lack of a role for protein moieties and the role for cell contact in the epithelial cell activity eliminate these mechanisms. Carbohydrate moieties, on the other hand, have recently gained importance in both microbial interactions and immune cell interactions with host cells. Studies have shown that secretion of membrane-associated glycosaminoglycans by intestinal mast cells inhibits parasite attachment and thereby prohibits nematode infection (40). Other studies have shown that carbohydrate moieties on host cells serve as a receptor for bacterial toxins such as that produced by Clostridium botulinum (16) and are also critical in L-selectin–ligand interactions (30, 47). Additionally, several studies have shown that C. albicans uses carbohydrate moieties, such as fucose and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, on host cells for attachment (9, 59).

Another important issue is whether the epithelial cell-mediated anti-Candida activity functions by killing versus inhibition of growth. The lack of any additional growth on culture plates incubated up to 5 days would suggest a fungicidal effect. Studies are currently in progress to address this issue more formally. In any event, taken together, these are the first data to suggest that a carbohydrate moiety is important in antifungal activity. Not only do epithelial cells themselves represent a potentially novel innate antifungal host defense mechanism, but also their anti-Candida effector function through a membrane carbohydrate moiety appears to be novel.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant DE-12178 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Biology, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradway S D, Bergey E J, Jones P C, Levine M J. Oral mucosal pellicle. Adsorption and transpeptidation of salivary components to buccal epithelial cells. Biochem J. 1989;261:887–896. doi: 10.1042/bj2610887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandtzaeg P, Gabrielsen T O, Dale I, Muller F, Steinbakk M, Fagerhol M K. The leucocyte protein L1 (calprotectin): a putative nonspecific defense factor at epithelial surfaces. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;371:201–206. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1941-6_41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassone A, Boccanera M, Adriani D A, Santoni G, De Bernardis F. Rats clearing a vaginal infection by Candida albicans acquire specific, antibody-mediated resistance to vaginal infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2619–2624. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2619-2624.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cenci E, Mencacci A, Spaccapelo R, Tonnetti L, Mosci P, Enssle K H, Puccetti P, Romani L, Bistoni F. T helper cell type 1 (Th1)- and Th2-like responses are present in mice with gastric candidiasis but protective immunity is associated with Th1 development. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1279–1288. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cenci E, Romani L, Vecchiarelli A, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. T cell subsets and IFN-gamma production in resistance to systemic candidosis in immunized mice. J Immunol. 1990;144:4333–4339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Challacombe S J, Sweet S P. Salivary and mucosal immune responses to HIV and its co-pathogens. Oral Dis. 1997;3:S79–S84. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clift R A. Candidiasis in the transplant patient. Am J Med. 1984;77:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cottrell R C. Phospholipase A2 from bee venom. Methods Enzymol. 1981;71:698–702. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)71082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Critchley I A, Douglas L J. Role of glycosides as epithelial cell receptors for Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:637–643. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-3-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Csato M, Kenderessy A S, Judak R, Dobozy A. Inflammatory mediators are involved in the Candida albicans killing activity of human epidermal cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 1990;282:348–350. doi: 10.1007/BF00375732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Bernardis F, Boccanera M, Adriani D, Spreghini E, Santoni G, Cassone A. Protective role of antimannan and anti-aspartyl proteinase antibodies in an experimental model of Candida albicans vaginitis in rats. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3399–3405. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3399-3405.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deitch E A, Haskel Y, Cruz N, Xu D, Kvietys P R. Caco-2 and IEC-18 intestinal epithelial cells exert bactericidal activity through an oxidant-dependent pathway. Shock. 1995;4:345–350. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobozy A, Szolnoky G, Gyulai R, Kenderessy A S, Marodi L, Kemeny L. Mannose receptors are implicated in the Candida albicans killing activity of epidermal cells. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 1996;43:93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drago L, Mombelli B, De Vicchi E, Bonaccorso C, Fassina M C, Gismondo M R. Candida albicans cellular internalization: a new pathogenic factor. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;16:545–547. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckhardt M, Barth H, Blocker D, Aktories K. Binding of Clostridium botulinum C2 toxin to asparagine-linked complex and hybrid carbohydrates. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2328–2334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fichorova R N, Anderson D J. Differential expression of immunobiological mediators by immortalized human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:508–514. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.2.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fidel P L, Jr, Cutright J L, Steele C. Effects of reproductive hormones on experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:651–657. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.651-657.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fidel P L, Jr, Ginsburg K A, Cutright J L, Wolf N A, Leaman D, Dunlap K, Sobel J D. Vaginal-associated immunity in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: evidence for vaginal Th1-type responses following intravaginal challenge with Candida antigen. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:728–739. doi: 10.1086/514097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fidel P L, Jr, Luo W, Steele C, Chabain J, Baker M, Wormley F L. Analysis of vaginal cell populations during experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3135–3140. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3135-3140.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fidel P L, Jr, Lynch M E, Redondo-Lopez V, Sobel J D, Robinson R. Systemic cell-mediated immune reactivity in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1458–1465. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fidel P L, Jr, Lynch M E, Sobel J D. Effects of preinduced Candida-specific systemic cell-mediated immunity on experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1032–1038. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1032-1038.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fidel P L, Jr, Lynch M E, Sobel J D. Circulating CD4 and CD8 T cells have little impact on host defense against experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2403–2408. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2403-2408.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filler S G, Swerdloff J N, Hobbs C, Luckett P M. Penetration and damage of endothelial cells by Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:976–983. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.976-983.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujino T, Ishikawa T, Inoue M, Beppu M, Kikugawa K. Characterization of membrane-bound serine protease related to the degradation of oxidatively damaged erythrocyte membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1374:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonella P A, Neutra M R. Membrane-bound and fluid-phase macromolecules enter separate prelysosomal compartments in absorptive cells of suckling rat ileum. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:909–917. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonella P A, Wilmore D W. Co-localization of class II antigen and endogenous antigen in the rat enterocyte. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:937–940. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.3.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauman C H, Thompson I O, Theunissen F, Wolfaart P. Oral carriage of Candida in healthy and HIV-seropositive persons. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:570–572. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90064-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedges S R, Agace W W, Svanborg C. Epithelial cytokine responses and mucosal cytokine networks. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:266–270. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88941-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemmerich S, Bertozzi C R, Leffler H, Rosen S D. Identification of the sulfated monosaccharides of GlyCAM-1: an endothelial-derived ligand for L-selectin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4820–4829. doi: 10.1021/bi00182a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herlander A, Hansson G C, Svennerholm A M. Binding of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli to isolated enterocytes and intestinal mucus. Microb Pathog. 1997;23:335–346. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Innes N, Ogden G. A technique for the study of endocytosis in human oral epithelial cells. Arch Oral Biol. 1999;44:519–523. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(99)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isaacs R D. Borrelia burgdorferi bind to epithelial cell proteoglycans. J Clin Investig. 1994;93:809–819. doi: 10.1172/JCI117035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein R S, Harris C A, Small C B, Moll B, Lesser M, Friedland G H. Oral candidiasis in high-risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:354–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight L, Fletcher J. Growth of Candida albicans in saliva: stimulation by glucose associated with antibiotics, corticosteriods and diabetes mellitus. J Infect Dis. 1971;123:371–377. doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehrer R, Ganz T, Szklarek D, Seisted M. Modulation of the in vitro candidiacidal activity of human neutrophil defensins by target cell metabolism and divalent cations. J Clin Investig. 1988;81:1829–1835. doi: 10.1172/JCI113527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leigh J E, Barousse M, Swoboda R K, Myers T, Hager S, Wolf N A, Cutright J L, Thompson J, Sobel J D, Fidel P L., Jr Candida-specific systemic cell-mediated immune reactivities in HIV-infected persons with and without mucosal candidiaisis. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:277–285. doi: 10.1086/317944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levitz S, DiBenedetto D J, Diamond R D. A rapid fluorescent assay to distinguish attached from phagocytized yeast particles. J Immunol Methods. 1987;101:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macher A M. The pathology of AIDS. Public Health Rep. 1988;103:246–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maruyama H, Yabu Y, Yoshida A, Nawa Y, Ohta N. A role of mast cell glycosaminoglycans for the immunological expulsion of intestinal nematode Strongyloides venezuelensis. J Immunol. 2000;164:3749–3754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyata R, Iwabuchi K, Watanabe S, Sato N, Nagaoka I. Exposure of intestinal epithelial cell HT29 to bile acids and ammonia enhances Mac-1-mediated neutrophil adhesion. Inflamm Res. 1999;48:265–273. doi: 10.1007/s000110050458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nohara K, Kunimoto M, Fujimaki H. Antibody against ganglioside GD1c containing NeuGcα2-8NeuGc cooperates with CD3 and CD4 in rat T cell activation. J Biochem. 1998;124:194–199. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Obrig T G, Culp W J, McKeehan W L, Hardesty B. The mechanism by which cycloheximide and related antibiotics inhibit peptide synthesis on reticuloctye ribosomes. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:174–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okuma K, Matsuura Y, Tatsuo H, Inagaki Y, Nakamura M, Yamamot N, Yanagi Y. Analysis of molecules involved in human T-cell leukaemia virus type 1 entry by a vesicular stomatitis virus pseudotype bearing its envelope glycoproteins. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:821–830. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-4-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pikula S, Epstein L, Martonosi A. The relationship between phospholipid content and Ca2+-ATPase activity in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1196:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez-Acosta F A, Galindo B, Cesari I M. Chemical nature of the interaction between macrophage fusion factor and macrophage membranes. Scand J Immunol. 1983;18:407–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1983.tb00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosen S D, Bertozzi C R. The selectins and their ligands. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:663–673. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sahasrabudhe K S, Kimball J R, Morton T H, Weinberg A, Dale B A. Expression of the antimicrobial peptide, human beta-defensin 1, in duct cells of minor salivary glands and detection in saliva. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1669–1674. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790090601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakakibara A, Furusre M, Saitou M, Ando-Akatsuka Y, Tsukita S. Possible involvement of phosphorylation of occludin in tight junction formation. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1393–1401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Savage S M, Donaldson L A, Sopori M L. T cell-B cell interaction: autoreactive T cells recognize B cells through a terminal mannose-containing superantigen-like glycoprotein. Cell Immunol. 1993;146:11–27. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwab U, Milatovic D, Braveny I. Increased adherence of Candida albicans to buccal epithelial cells from patients with AIDS. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:848–851. doi: 10.1007/BF01700418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sobel J D. Pathogenesis and epidemiology of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;544:547–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb40450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sohnle P G, Hahn B L, Santhanagopalan V. Inhibition of Candida albicans growth by calprotectin in the absence of direct contact with the organisms. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1369–1372. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steele C, Leigh J E, Swoboda R K, Fidel P L., Jr Growth inhibition of Candida by human oral epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1479–1485. doi: 10.1086/315872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steele C, Ozenci H, Luo W, Scott M, Fidel P L., Jr Growth inhibition of Candida albicans by vaginal cells from naive mice. J Med Mycol. 1999;37:251–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steele C, Ratterree M, Fidel P L., Jr Differential susceptibility to experimental vaginal candidiasis in macaques. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:802–810. doi: 10.1086/314964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sussich F, Cesaro A. The kinetics of periodate oxidation of carbohydrates: a calorimetric approach. Carbohydr Res. 2000;239:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor B N, Saavedra M, Fidel P L., Jr Local Th1/Th2 cytokine production during experimental vaginal candidiasis. J Med Mycol. 2000;38:419–431. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.6.419.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tosh F D, Douglas L J. Characetrization of a fucoside-binding adhesin of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4734–4739. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4734-4739.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weinberg A, Krisanaprakornkit S, Dale B A. Epithelial antimicrobial peptides: review and significance for oral applications. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:399–414. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams D W, Walker R, Lewis M A, Allison R T, Potts A J. Adherence of Candida albicans to oral epithelial cells differentiated by Papanicolaou staining. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:529–531. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.7.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wira C R, Rossoll R M. Antigen-presenting cells in the female reproductive tract: influence of the estrous cycle on antigen presentation by uterine epithelial and stromal cells. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4526–4534. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu T, Levitz S M, Diamond R D, Oppenheim F G. Anticandidal activity of major human salivary histatins. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2549–2554. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2549-2554.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang J P, Stephens R S. Mechanism of C. trachomatis attachment to eukayrotic host cells. Cell. 1992;69:861–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90296-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]