Abstract

Aim

Treatment guidelines are designed to assist patients and health care providers and are used as tools for making treatment decisions in clinical situations. The treatment guidelines of the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders establish treatment recommendations for each severity of depression. The individual fitness score (IFS) was developed as a simple and objective indicator to assess whether individual patients are practicing treatment by the recommendations of the depression treatment guidelines of the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders.

Methods

The EGUIDE project members determined the IFS through the modified Delphi method. In this article, the IFS was calculated based on the treatment of depressed patients treated and discharged between 2016 and 2020 at facilities participating in the EGUIDE project. In addition, we compared scores at admission and discharge.

Results

The study included 428 depressed patients (mild n = 22, moderate/severe n = 331, psychotic n = 75) at 57 facilities. The mean IFS scores by severity were statistically significantly higher at discharge than at admission with moderate/severe depression (mild 36.1 ± 34.2 vs. 41.6 ± 36.9, p = 0.49; moderate/severe 50.2 ± 33.6 vs. 55.7 ± 32.6, p = 2.1 × 10–3; psychotic 47.4 ± 32.9 versus 52.9 ± 36.0, p = 0.23).

Conclusion

We developed the IFS based on the depression treatment guideline, which enables us to objectively determine how close the treatment is to the guideline at the time of evaluation in individual cases. Therefore, the IFS may influence guideline‐oriented treatment behavior and lead to the equalization of depression treatment in Japan, including pharmacotherapy.

Keywords: Delphi method, depression, EGUIDE, guideline, individual fitness score, severity

1. INTRODUCTION

Treatment guidelines are developed to assist patients and health care providers and are used as tools for making treatment decisions in clinical practice. Many countries have developed treatment guidelines. 1 , 2 , 3 The Japanese Society of Mood Disorders (JSMD) published “Japanese Society of Mood Disorders. Treatment Guidelines II. Major Depressive Disorder” in 2012, and this was subsequently revised in 2016. 4 , 5 The depression treatment guidelines of JSMD establish treatment recommendations for the severity levels of depression: mild, moderate/severe, and psychotic.

In 2016, the “Effectiveness of GUIdeline for Dissemination and Education in psychiatric treatment (EGUIDE)” project was started to disseminate guidelines and standardize treatment. 6 This project conducts a training course on these guidelines. It also examines the degree of dissemination of these guidelines through a survey of participants' understanding of the course and the content of inpatient treatment. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 The results showed that participants who attended the training improved their knowledge of the guidelines 7 and practiced the guidelines. 8

In this project, quality indicator (QI) are developed as objective indicators to verify whether the guideline practices treatment. 9 , 10 For depression, eight QIs have been established based on the recommendations of the guidelines of JSMD. Specifically, the QIs are: the rate of diagnosis of depression severity among patients treated at the same institution, the rate of antidepressant monotherapy, the rate of antidepressant monotherapy without the use of any other psychotropics, the rate of no prescription of antianxiety or sleep medication, the rate of modified electroconvulsive therapy (mECT) treatment, the rate of cognitive–behavioral therapy, and the rate of sulpiride prescriptions. Thus, we can compare QI among our facilities, and we can verify changes in QI over time at the same facility. However, it is difficult to use QI for evaluating the treatment of individual patients. Therefore, there is a need for an indicator that can quickly and objectively evaluate whether individual patients are receiving treatment based on the recommendations of the depression treatment guidelines of JSMD. Therefore, in this study, we developed an indicator, individual fitness score (IFS), to visualize whether patients are practicing the recommended treatment according to the depression treatment guidelines of JSMD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Modified Delphi method

The validity of the IFS was determined by the modified Delphi method. The Delphi method is one of the methods used to aggregate the opinions and findings of a group of people to obtain a unified view. The Delphi method is a structured process that collects opinions through questionnaires and rounds that are repeated until a group consensus is reached. 18 The composition of the members and the process of reaching a decision is considered necessary when reaching an agreement using the Delphi method. 19

Members of the EGUIDE project determined the scores for each treatment through the modified Delphi method. The members involved in the modified Delphi method are familiar with the depression treatment guidelines of JSMD, as they are educating Japanese psychiatrists on these guidelines through the EGUIDE project. The members are unbiased in the regions where they work in Japan, and there is diversity in the areas of psychiatric specialty.

To establish appropriate scores, an online questionnaire using a Google Form was administered after members discussed the issue in an online meeting, and the validity of the scores for each treatment was evaluated using the two‐case method. Rounds were conducted four times between April 2021 and November 2021. In each round, the questionnaire collection rate was 100%. Twenty participants attended the final round, and they reached a consensus with the approval of more than 90% (18 participants) of the participants.

2.2. Development of the IFS

The IFS was developed to evaluate whether treatment is practiced by the “Japanese Society of Mood Disorders. Treatment Guidelines II. Major Depressive Disorder” (Table 1, Tables S1–S2). 4 The IFS does not consider the presence of comorbidities but only evaluates the degree to which guideline treatment is practiced. The score ranges from 0 to 100, with 100 for treatment that is entirely guideline‐compliant. The scores will be deducted from 100 for treatment that does not comply with the guidelines. The IFS is determined by adding up the scores for each treatment situation. In developing the IFS, we first developed a version for moderate/severe depression (Table 1). Then, a version for mild depression (Table S1) and a version for psychotic depression (Table S2) was developed based on this version.

TABLE 1.

IFS formula for moderate/severe depression treatment based on the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders

| Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of antidepressants | 0 |

Combination ECT (+) 0 |

combination ECT (−) −80 |

|

| 1 | 0 | |||

| 2 | −20 | |||

| ≧3 | −50 | |||

| Number of drugs | Antidepressants prescribed (+) | Antidepressants prescribed (−) | ||

| Augmentation therapy | Atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilizers (lithium carbonate, valproic acid, carbamazepine, lamotrigine) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | −5 |

Per one Drug −50 |

||

| 2 | −20 | |||

| 3 | −40 | |||

| 4 | −60 | |||

| Hypnotics (barbiturates, chlorpromazine‐promethazine‐phenobarbital combination drugs, and bromovalerylurea are excluded) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | −20 |

Per one Drug −50 |

||

| 2 | −45 | |||

| ≧3 | −70 | |||

| Anxiolytics | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | −25 |

Per one Drug −50 |

||

| 2 | ‐50 | |||

| ≧3 | −75 | |||

| Typical antipsychotics (including sulpiride) | Per one Drug | −50 | ||

| ADHD medications, narcolepsy medications, barbiturates, bromovalerylurea, and chlorpromazine‐promethazine‐phenobarbital combination drugs | Per one Drug | −80 | ||

| Antiepileptics (other than valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine), dopamine agonists, and anticholinergics | Per one Drug | −50 | ||

| EBPT (CBT) | Treatment (+) | −5 | −50 | |

Note: The IFS formula for moderate/severe depression does not deduct points for monotherapy with antidepressants, which is the recommended treatment. However, prescribing two antidepressants results in a score of −25, and prescribing three or more antidepressants results in a score of −50. However, no points are deducted if ECT is used without prescribing antidepressants. CBT, augmentation therapy with antidepressants and prescription of hypnotics and anxiolytics are scored differently depending on whether they are prescribed in combination with antidepressants. For nonprescribers of antidepressants, the score is −50 for CBT and −50 for each prescription of antidepressant augmentation therapy, hypnotics, and anxiolytics. The combination treatment of antidepressant drugs and CBT results in a score of −5. An atypical antipsychotic or mood stabilizer prescribed in combination with an antidepressant results in a score of −5 because both are the recommended treatment when selected as needed. If two atypical antipsychotic or mood stabilizers are prescribed in combination with an antidepressant, the prescription results in a score of −20; if three antipsychotics are prescribed, the prescription results in a score of −40; and if four antipsychotics are prescribed, the prescription results in a score of −60. Hypnotics have a score of −20 for a one‐drug prescription, −45 for a two‐drug prescription, and −70 for three or more drugs. Anxiolytics have a score of −25 for one prescription, −50 for two prescriptions, and −75 for three or more prescriptions. Antipsychotic prescriptions containing sulpiride, which is not a recommended treatment, result in a score of −50 for each prescription, and ADHD, narcolepsy, barbiturates, bromovalerylurea, and chlorpromazine‐promethazine‐phenobarbital combination drugs result in a score of −80 for each prescription.

Abbreviations: CBT, Cognitive behavioral therapy; EBPT, Evidence‐based psychotherapy; ECT, modified electroconvulsive therapy.

The depression treatment guidelines of JSMD define “recommended treatment”, “recommended treatment selected as needed”, and “not recommended treatment”. The recommended treatment for moderate or severe depression is antidepressant prescriptions or mECT. The recommended treatment selected as needed is treatment that combines antidepressant prescriptions and cognitive behavioral therapy and augmentation of antidepressant medications with atypical antipsychotics, lithium carbonate, or mood stabilizers. Treatment not recommended is the prescription of sulpiride, central nervous system stimulants, and barbiturates. Monotherapy with benzodiazepines without antidepressants and monotherapy with antipsychotics are also not recommended. 4 As a general rule for setting the score in the IFS, no points will be deducted if the recommended treatment is administered. The score will be −5 when a treatment that corresponds to the recommended treatment is selected and performed as needed. If the patient receives a treatment that is not recommended, a score of −50 or −80 will be assigned. Anticholinergic and anti‐parkinsonism drugs are not generally prescribed for depression. Therefore, if the patients received these drugs, the IFS score is −50.

2.3. IFS evaluation subjects

In a cross‐sectional, retrospective, observational study, we examined the treatment of depressed patients discharged in the first half (April to September) of each year from 2016 to 2020 at facilities participating in the EGUIDE project. The study included sex, age, cognitive–behavioral therapy and mECT, and prescriptions at admission and discharge. The study population consisted of patients who had been treated before attending an educational program on the treatment guidelines of depression and whose severity of illness was noted on their discharge treatment summary. The definition of severity was based on DSM‐5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) 20 and classified into mild, moderate/severe, and psychotic groups. Since the depression treatment guidelines of JSMD recommend similar treatment for moderate and severe depression, 4 both were evaluated together.

The Ethics Board approved the study at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and participating EGUIDE centers. This study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Registry (UMIN000022645).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Sex, number of antidepressant prescriptions, prescriptions of anxiolytics and hypnotics, concurrent prescriptions of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and percentage of mECT among severity levels were tested using the chi‐square test. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for age, imipramine equivalent, chlorpromazine equivalent, and diazepam equivalent. In addition, the IFS on admission and discharge for each severity of illness was verified. The difference between the mean IFS values on admission and discharge for each severity was evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. The correlation between mean IFS and QIs in patients with moderate/severe depression was analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). We set the significance level at p < 0.05 and used the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

3. RESULTS

Of the 815 depressed patients at 79 facilities, 428 patients at 57 facilities whose severity was noted on their discharge treatment summary were included. Of these, 22 had mild depression, 331 had moderate/severe depression, and 75 had psychotic depression. Antidepressant monotherapy prescription rates were 72.7% for mild depression, 74.3% for moderate/severe depression, and 70.7% for psychotic depression. Treatment that showed significant differences between severity levels were the percentage of patients without antipsychotic prescriptions (63.6% mild, 58.0% moderate/severe, 29.3% psychotic, p = 2.5 × 10−5) and the mean diazepam equivalent (mild 7.2 ± 5.7 mg, moderate/severe 10.5 ± 11.1 mg, psychotic 6.9 ± 4.5 mg, p = 3.3 × 10−3) and the percentage of patients receiving mECT (mild 0%, moderate/severe 15.4%, psychotic 44.0%, p = 7.7 × 10−9) (Table S3).

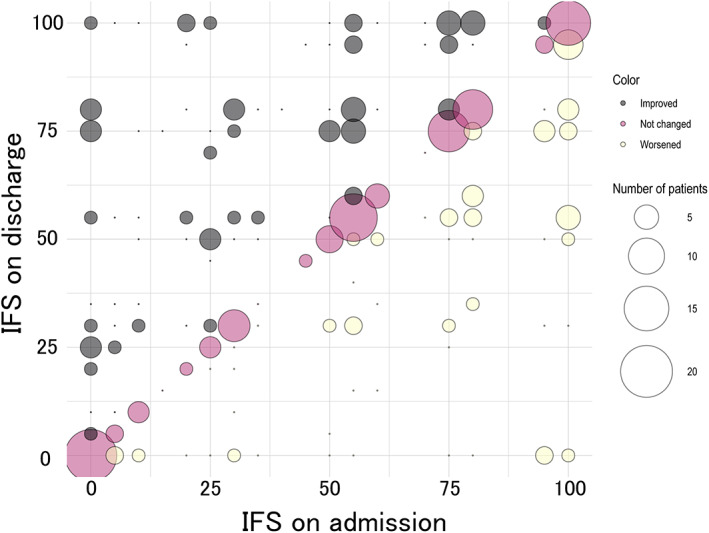

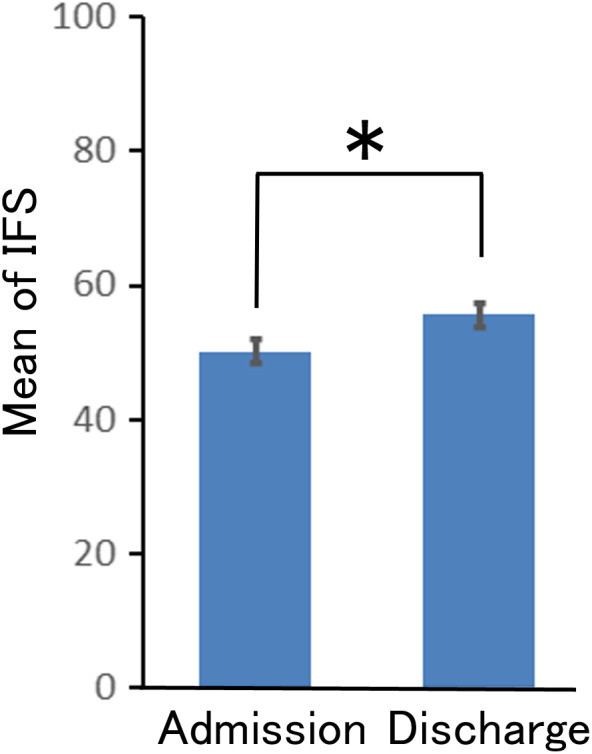

Bubble blots show the association between the IFS on admission and the IFS on discharge for individual patients (Figure 1 and Figure S2). For all severity levels, the IFS on admission and on discharge ranged from 0 to 100. The mean IFS scores by severity were statistically significantly higher on discharge than on admission only for patients with moderate/severe illness (mild 36.1 ± 34.2 vs. 41.6 ± 36.9, p = 0.49; moderate/severe 50.2 ± 33.6 vs. 55.7 ± 32.6, p = 2.1 × 10−3; psychotic 47.4 ± 32.9 vs. 52.9 ± 36.0, p = 0.23) (Figure 2, Table S4). There was no difference in the mean IFS between severity on admission and on discharge (on admission; p = 0.149, on discharge; p = 0.146).

FIGURE 1.

The association between the IFS on admission and the IFS on discharge for individual patients with moderate/severe depression patients. The size of the circles indicates the number of patients. The IFS on discharge is higher than the IFS at admission is shown in black, unchanged in pink, and lower in yellow

FIGURE 2.

The mean IFS on admission and on discharge for patients with moderate/severe depression. Y‐axis shows the mean IFS (mean ± S.E.) for patients with moderate/severe depression (n = 331) on discharge. Black bar: admission, gray bar: discharge, *p < 0.005

To examine the distribution of mean IFS scores across facilities, 28 facilities with at least four cases of moderate/severe depression were included. Mean IFS varied between facilities, ranging from 25.0 to 83.4 on admission and 21.0 to 85.0 on discharge (Figure S1). In addition, these facility data were used to test whether there was a correlation between IFS and QI. Results showed a correlation between IFS and QI‐1 (Proportion of patients receiving antidepressant monotherapy) and QI‐2 (Proportion of patients receiving antidepressant monotherapy without the use of any other psychotropics) (QI‐1 r s = 0.73, p = 8.5 × 10−6, QI‐2 r s = 0.57, p = 1.6 × 10–3) (Table S5). The number of facilities with at least four cases of mild or psychotic depression was small (mild: n = 1, psychotic: n = 6). Therefore, the validation between facilities could not examine.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed an IFS to verify whether the recommended treatment by the “Japanese Society of Mood Disorders Treatment Guidelines II: Major Depressive Disorder” was practiced, and it was possible to confirm in each case. Notably, the IFS is the first attempt to develop an index of treatment based on depression treatment guidelines; as there have been no reports of such an attempt. In individual cases, the IFS on admission and discharge were widely distributed between 0 and 100 (Figure 1 and Figure S2). The mean IFS on discharge was also calculated for the EGUIDE project participating institutes, and the scores were also distributed among the institutes (Figure S1). A previous examination of depression treatment at facilities participating in the EGUIDE project by QI reported similarly large variations in QI from institution to institution as in the present results. 9 The distribution of scores on the IFS in the present study was similar, suggesting that the IFS adequately assesses guideline treatment.

A comparison of the IFSs on admission and discharge revealed that treatment for moderate and severe depression at discharge was closer to guideline recommendations than at admission (Figure 2, Table S4). It is presumed that the treatment plan was reevaluated after hospitalization, resulting in drug adjustments that bring the treatment closer to the guideline recommendations. The mean IFS for mild and psychotic depression was higher on discharge than on admission, but the difference was insignificant. This may be due to the small sample size.

This study had the following three limitations: first, because the IFS was developed for each severity level according to the guidelines, it was not possible to verify for depressed patients whose severity was not evaluated. Muraoka et al. reported that the severity diagnosis rate for depression was 56.8% overall. 12 Thus, it is important to continue to encourage evaluation of the severity levels of depression in patients in Japan. Second, the IFS cannot be used to evaluate treatment by considering the effects of comorbidities. Third, the scores on admission and discharge were calculated based on only inpatient treatment data from institutions that participated in the EGUIDE project. In addition, the results of this study do not reflect the actual treatment situation at all psychiatric institutions in Japan since depressed patients attending outpatient appointments were not included in the assessment in this study.

In conclusion, this study developed an IFS based on depression treatment guidelines. Using this IFS, it became possible to objectively ascertain how close the treatment was to the guidelines for individual cases at the time of evaluation. In general clinical practice, there are many situations in which the treatment plan needs to be reconsidered, such as when psychiatric symptoms worsen when a patient is referred from another hospital, when a primary care physician takes over, or when an outpatient is admitted to a hospital. In addition, the use of the IFS can lead to the visualization of treatment between physicians and patients and may become a new tool for shared decision‐making. The IFS may influence guideline treatment behavior and lead to the equalization of depression treatment in Japan, including drug treatment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KF was involved in data collection and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FK and HM were involved in data collection and data analysis. NH, HH, KI, YY, HI, KO, SO, KI, NY‐F, and HY were involved in the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. NH, MU, TN, HK, TO, TN, RF, KA, MK, SK, HY, TK, MM, TH, MT, CK, TA, EK, AH, TO, JM, KM, and KO contributed to the interpretation of the data and data collection. KW and KI were involved in the study design and contributed to the interpretation of the data. RH supervised the entire project, collected the data, and was involved in the data's design, analysis, and interpretation. All authors contributed to and approved the final article.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Number JP16dk0307060, JP19dk0307083, and JP22dk0307112, JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP21K17261, the Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants (H29‐Seishin‐Ippan‐001, 19GC1201), the Japanese Society of Neuropsychopharmacology, the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, the Japanese Society of Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology, the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Approval of the Research Protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: This study was approved by the ethics committees of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (B2022‐044) and each participating university, hospital, and clinic.

Informed Consent: All participants provided their written informed consent.

Trial Registration Number: The University Hospital Medical Information Network Registry (UMIN000022645).

Animal Studies: n/a.

Supporting information

Figure S1 –S2

Table1 S1–S5

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We appreciate the cooperation of all the individuals who participated in this study.

Fukumoto K, Kodaka F, Hasegawa N, Muraoka H, Hori H, Ichihashi K, et al. Development of an individual fitness score (IFS) based on the depression treatment guidelines of in the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2023;43:33–39. 10.1002/npr2.12301

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions (i.e., we did not obtain informed consent on the public availability of raw data).

REFERENCES

- 1. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Depression in adults: The treatment and management of depression in adults. Available from [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs8] [PubMed]

- 2. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Grigoriadis S, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. III Pharmacotherapy. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S26–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, et al. World Federation of Societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13:318–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Japanese Society of Mood Disorders . Treatment Guidelines II. Major Depressive Disorder 2016. 2019. (in Japanese). https://www.secretariat.ne.jp/jsmd/iinkai/katsudou/data/20190724‐02.pdf

- 5. Baba H, Kito S, Nukariya K, Takeshima M, Fujise N, Iga J, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of depression in older adults: a report from the Japanese society of mood disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022(in printing);76:222–34. 10.1111/pcn.13349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takaesu Y, Watanabe K, Numata S, Iwata M, Kudo N, Oishi S, et al. Improvement of psychiatrists' clinical knowledge of the treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and major depressive disorders using the 'Effectiveness of guidelines for dissemination and education in psychiatric treatment (EGUIDE)' project: a nationwide dissemination, education, and evaluation study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73:642–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Numata S, Nakataki M, Hasegawa N, Takaesu Y, Takeshima M, Onitsuka T, et al. Improvements in the degree of understanding the treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and major depressive disorder in a nationwide dissemination and implementation study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2021;41(2):199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamada H, Motoyama M, Hasegawa N, Miura K, Matsumoto J, Ohi K, et al. A dissemination and education programme to improve the clinical behaviours of psychiatrists in accordance with treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and major depressive disorders: the effectiveness of guidelines for dissemination and education in psychiatric treatment (EGUIDE) project. BJPsych Open. 2022;8:e83. 10.1192/bjo.2022.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iida H, Iga J, Hasegawa N, Yasuda Y, Yamamoto T, Miura K, et al. Unmet needs of patients with major depressive disorder ‐ findings from the 'Effectiveness of guidelines for dissemination and education in psychiatric treatment (EGUIDE)' project: a nationwide dissemination, education, and evaluation study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74:667–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ichihashi K, Hori H, Hasegawa N, Yasuda Y, Yamamoto T, Tsuboi T, et al. Prescription patterns in patients with schizophrenia in Japan: first‐quality indicator data from the survey of "effectiveness of guidelines for dissemination and education in psychiatric treatment (EGUIDE)" project. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2020;40:281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hori H, Yasui‐Furukori N, Iga J, Takaesu Y, Ochi S, et al. Prescription of antiparkinsonian drugs in patients with schizophrenia: interinstitutional and interantipsychotic analysis. Front Psych. 2022;13:823826. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.823826 eCollection 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muraoka H, Kodaka F, Hasegawa N, Yasui‐Furukori N, Fukumoto K, et al. Characteristics of the treatments for each severity of major depressive disorder: A real‐world multi‐site study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;74:103174. 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yasui‐Furukori N, Muraoka H, Hasegawa N, Ochi S, Numata S, Hori H, et al. Association between the examination rate of treatment‐resistant schizophrenia and the clozapine prescription rate in a nationwide dissemination and implementation study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2022;42:3–9. 10.1002/npr2.12218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Furihata R, Otsuki R, Hasegawa N, Tsuboi T, Numata S, Yasui‐Furukori N, et al. Hypnotic medication use among inpatients with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder: results of a nationwide study. Sleep Med. 2021;89:23–30. 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hashimoto N, Yasui‐Furukori N, Hasegawa N, Ishikawa S, Numata S, Hori H, et al. Characteristics of discharge prescriptions for patients with schizophrenia or major depressive disorder: real‐world evidence from the effectiveness of guidelines for dissemination and education (EGUIDE) psychiatric treatment project. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;63:102744. 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ichihashi K, Kyou Y, Hasegawa N, Yasui‐Furukori N, Shimnizu Y, et al. The characteristics of patients receiving psychotropic pro re nata medication at discharge for the treatment of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder: a nationwide survey from the EGUIDE project. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;69:103007. 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ogasawara K, Numata S, Hasegawa N, Nakataki M, Makinodan M, Ohi K, et al. Subjective assessment of participants in education programs on clinical practice guidelines in the field of psychiatry. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2022;42:221–5. 10.1002/npr2.12245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20476. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Association AP. Depressive disorders: DSM‐5® selections. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 –S2

Table1 S1–S5

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions (i.e., we did not obtain informed consent on the public availability of raw data).