Abstract

Background:

An association between child sexual abuse (CSA) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been documented. However, the temporal relationship between these problems and the roles of trauma-related symptoms or other forms of maltreatment remain unclear. This review aims to synthesize available research on CSA and ADHD, assess the methodological quality of the available research, and recommend future areas of inquiry.

Methods:

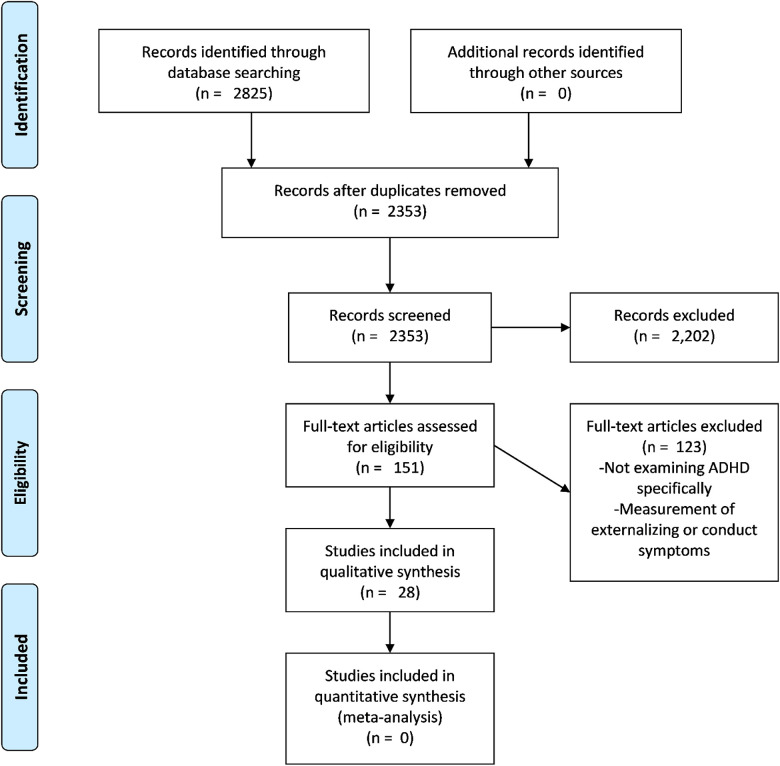

Studies were searched in five databases including Medline and PsycINFO. Following a title and abstract screening, 151 full texts were reviewed and 28 were included. Inclusion criteria were sexual abuse occurred before 18 years old, published quantitative studies documenting at least a bivariate association between CSA and ADHD, and published in the past 5 years for dissertations/theses, in French or English. The methodological quality of studies was systematically assessed.

Results:

Most studies identified a significant association between CSA and ADHD; most studies conceptualized CSA as a precursor of ADHD, but only one study had a longitudinal design. The quality of the studies varied greatly with main limitations being the lack of (i) longitudinal designs, (ii) rigorous multimethod/ multiinformant assessments of CSA and ADHD, and (iii) control for two major confounders: trauma-related symptoms and other forms of child maltreatment.

Discussion:

Given the lack of longitudinal studies, the directionality of the association remains unclear. The confounding role of other maltreatment forms and trauma-related symptoms also remains mostly unaddressed. Rigorous studies are needed to untangle the association between CSA and ADHD.

Keywords: child sexual abuse, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, systematic review

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a major public health concern that can have a long-lasting impact throughout the life span. It is estimated that approximately 20% of girls and 8% of boys will experience CSA before the age of 18 years (Stoltenborgh et al., 2011). CSA has been found to be associated with a myriad of mental health problems that can persist through adulthood, including dissociation (Hillberg et al., 2011), depression (Hillberg et al., 2011), and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety (Chen et al., 2010; Hillberg et al., 2011). An adverse childhood experience such as CSA is likely to disrupt the mastery of core developmental tasks (Irigagay et al., 2013), such as the ability to regulate emotions and to form secure attachments. (Doyle & Cicchetti, 2017). CSA has also been empirically associated with internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in childhood (Berliner, 2011; Langevin et al., 2015) and with difficulties in the school environment (e.g., peer victimization, lower grades, need for special education; Daignault & Hébert, 2009; Hébert et al., 2016; Perfect et al., 2016). CSA, as well as other types of childhood maltreatment, has been associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Fuller-Thomson & Lewis, 2015; González et al., 2019; Sanderud et al., 2016). Although ADHD has been linked to CSA in previous studies, the direction of this association and its relationship to other mental health problems is unclear. Interestingly, this temporality issue with ADHD and CSA only applies to few other consequences/risk factors that have been associated with CSA (e.g., chronic conditions; Assink et al., 2019).

ADHD is a heritable neurodevelopmental disorder with prevalence rates ranging from 2% to 7.1% depending on meta-analytic rates (Sayal et al., 2018; Willcutt, 2012). ADHD typically has a childhood onset (less than 12 years old) and is characterized by inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The associated patterns of behaviors can cause performance-related issues in educational, social, and professional environments that can persist into adulthood (Harpin et al., 2016). For example, Ebejer and colleagues (2012) found ADHD symptoms in adults to be associated with poorer health, lower educational attainment, and higher rates of unemployment. In addition, a Danish study found individuals with ADHD to have higher annual health care costs and to be more likely to receive social services in adulthood (Jennum et al., 2020). In this review, the terms ADHD and ADHD symptoms will be used. ADHD refers to the diagnosis, whereas ADHD symptoms refer to the presence of symptoms that do not necessarily reach the clinical levels of the disorder. ADHD and ADHD symptoms, like CSA, can have dramatic consequences on individual’s adaptation and should be the focus of prevention and intervention efforts aiming to reduce the burden on affected individuals and, more largely, society.

As previously mentioned, CSA has been associated with ADHD in both men and women, but the direction of this association remains unclear. Indeed, some scholars have studied how ADHD can be a risk factor for later sexual victimization, while others have looked at the impact of CSA on the development of ADHD symptoms (Ebejer et al., 2012; Fuller-Thomson & Lewis, 2015; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016). A few mechanisms have been suggested to explain CSA as a risk factor for ADHD (Fuller-Thompson & Lewis, 2015): (1) Stress induced by the exposure to CSA may cause changes in the individual’s brain functioning (e.g., deficits in default mode network connectivity involved in the activation of the medial temporal, prefrontal cortices, and the limbic areas integrated in the posterior cingulate) that could result in ADHD (Anda et al., 2006; Dvir et al., 2014) and (2) learned experiences of threat, such as CSA, could affect the neural development and lead to changes in brain structures that are consistent with ADHD (McLaughlin et al., 2014). Conversely, it has also been demonstrated that ADHD can be a risk factor for CSA (Gotby et al., 2018). Experts speculate that children with ADHD (among other neurodevelopmental disorders) may be perceived as different, and it may be easier for motivated, potential offenders to dehumanize their victims and thus to transgress boundaries (Gotby et al., 2018; Rudman & Mescher, 2012). It is also worthy to mention that several ADHD symptoms overlap with core symptoms of PTSD, raising concerns about potential misdiagnosis of ADHD in traumatized individuals (Spencer et al., 2016).

Despite burgeoning interest in the topic and the multiplication of studies looking at the interrelations between CSA and ADHD in the past decades, to date, no systematic review synthesizing the evidence is available. Given the current state of research on this topic and the mixed perspectives on the direction of the association between ADHD and CSA, integrating the available research will help in identifying future directions of inquiry and help both clinicians and researchers have a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the ADHD–CSA association. In this context, the current systematic review aims to (1) synthesize available research on the associations between CSA and ADHD, its temporality and its relationship to trauma-related symptoms, (2) assess the methodological quality of available research, and (3) recommend directions for future research and practice.

Method

Article Search and Selection

Subject headings (when available) and key words were searched from the following databases in this order: (1) MEDLINE Ovid (1946–January 8, 2020), (2) PsycINFO Ovid (1806–January 8, 2020), (3) ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center; 1966–January 8, 2020), (4) Scopus (searched January 8, 2020), and (5) ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (searched January 8, 2020). The initial search was built in Medline (see Appendix). It was peer-reviewed by Dr. Tracie Afifi, Professor at the University of Manitoba, who has expertise in research on child maltreatment and mental health.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Given our specific interest in CSA, to be included in the review, sexual abuse had to have occurred before 18 years of age. Other inclusion criteria included published quantitative studies, dissertations and theses, and conference proceedings, as well as book chapters if they reported original findings. Studies published in English and French were included. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria pertaining to the demographic background of participants nor where the study was conducted or published. Other review papers were not included. All articles published up to the time of article search/extraction (January 8, 2020) were included, except for theses and dissertations (only the past 5 years).

The search resulted in 2,825 articles. After removal of duplicates, 2,353 articles remained, which were imported into Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016) to facilitate the screening process. Following a review of titles and abstracts, 2,202 articles were excluded, resulting in 151 articles deemed eligible for full-text assessment. Following full-text assessment, a further 123 articles were excluded, leaving a final sample of 28 articles for this review. See Figure 1 for a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2009 flow diagram.

Data Extraction and Analysis

To address interrater reliability, the first 60 titles and abstracts were reviewed by the first three authors, after which the second and third authors continued screening, met to discuss discrepancies with each other, as well as consulted with the first author in cases of uncertainty. The same process was conducted for reading the 151 full-text articles; all were read and agreed upon by the second and third author, while consulting the first author. Throughout the process of full-text screening, the last author was also consulted for her expertise in externalizing behaviors. After reading the 151 full-text articles, 123 were excluded due to ADHD not being clearly measured. For instance, many studies examined behavioral or externalizing problems more generally or measured the association between conduct problems and sexual abuse.

The 28 remaining articles were assessed for quality using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, published by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools). This is a 14-item tool that requires readers to assess papers primarily on methods and requires a final rating of “good”, “fair”, or “poor.” The final 28 articles were evenly divided among the first three authors and last author, who appraised and summarized the articles in pairs. A summary template was created, so that each author extracted the same information from their articles including study aims, study design, sample, setting and procedures, measures, principal relevant results, and limitations. The authors met to discuss and resolve discrepancies in appraisal items and the final quality ratings.

Results

The presentation of the findings is subdivided based on the theoretically or empirically postulated direction of the effects between CSA and ADHD. As such, papers conceptualizing CSA as a risk factor for ADHD are presented first, subdivided based on the use of an adult (mean age of 18 years or older) or child sample. Next, papers conceptualizing ADHD as a risk factor for CSA are presented with the same subdivision based on sample type. Finally, papers that did not seem to postulate a specific direction between CSA and ADHD, and therefore that appeared to conceptualize these as comorbid problems, are summarized. Further, presentation of the findings is separated based on the use of bivariate versus more complex analytic approaches accounting for potential confounders in the relation between ADHD and CSA. See Table 1 for details about the included studies.

Table 1.

Review Results Organized by Child and Adult Samples.

| Reference | Study Aims | Sample | Study Setting and Design | Measures | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child/adolescent samples | |||||

| Boyd et al. (2019) | Examining how maltreatment influences attention problems |

7,214 Mother and child dyads with information on child maltreatment | Australia Prospective longitudinal, birth cohort study |

|

14 years of age YSR: in bivariate analyses, but not in multiple

regressions, sexual abuse associated with more attention

problems: F test = 5.221, p = .022 YSR: unstandardized B = .484, SE = 0.266, β = .026, t = 1.82, p = .069 14 years of age CBCL: in bivariate analyses and multiple regressions, sexual abuse associated with more attention problems: F test = 6.755, p = .009 CBCL: unstandardized B = .896, SE = 0.316, β = .039, t = 2.838, p = .005 Confounding factors included for YSR and CBCL at 14 years of age: notification for physical, emotional abuse, or neglect; gender; indigenous Australian; relationship status; family income prior to birth; maternal education; chronic maternal depression; and birthweight 21 years of age YASR: sexual abuse not associated with attention problems in bivariate and multiple regressions: F test = 0.199, p = .655 Unstandardized B = .229, SE = 0.255, β = .015, t = 0.897, p = .370 Confounding factors included at 21 years of age YASR: same as in previous regression + youth income and relationships |

| Ford et al. (2000) | Investigate history of maltreatment in child psychiatry

outpatients with ADHD |

165 Children (mean age = 12, SD = 3.4; 57%

female, 43% male) Study groups: for sexual abuse, 11% in ADHD only group, 18% in ODD only, 31% in ADHD/ODD group, and 0% adjustment disorder group |

United States Retrospective case control |

|

Bivariate analysis: study groups differed significantly in

sexual abuse χ2(3, N = 165) = 15.0, p < .001 Sexual abuse was greatest for the group with both ADHD and ODD |

| Ford et al. (2009) | Identify subgroups of children with psychiatric disorders in

terms of maltreatment history |

397 Psychiatric residents (mean age = 13.4 ± 2.6; 81% male) 126 had sexual abuse history |

United States Cross-sectional, chart review study |

|

Sexual abuse was not a significant predictor of attention

problems: (B = .30, SE = 1.30,

β = .01, t = 0.23, p = .82)

and did not predict Conners’ Teacher scores, B

= .84, SE = 1.06, β = .05, t =

0.79, p = .43. Confounding factors included: female gender, non-White ethnicity, psychotic disorder, internalizing and externalizing disorder, developmental disorder, substance use disorder, complex trauma, parental impairment, nonfamily placement, placed before age 5, multiple placements, and physical abuse |

| Gokten et al. (2016) | To examine the risk of children diagnosed with ADHD to

experience abuse or neglect |

104 Children diagnosed with ADHD; 104 healthy control children

were compared Children between 6 and 12 years old |

Turkey Cross-sectional, case-controlled |

|

Bivariate analysis: no statistically significant difference

between children with and without ADHD in terms of sexual abuse

(p = .149) |

| Gomes-Schwartz et al. (1985) | Evaluate children’s emotional responses following sexual

abuse |

112 Children ranging in age from 4 to 18 | United States Cross-sectional |

|

Bivariate analysis (t tests): Among 7- to 13-year-olds, the mean score of hyperactivity was significantly higher than that of the general population as reported in the norm sample of the Louisville Behavior Checklist (M = 58.62, SD = 14.16, p < .05) |

| González et al. (2019) | Examine associations between maltreatment and ADHD and estimate

associations between repetitive maltreatment and ADHD |

2,480 Latino male and female children aged 5–13 years |

United States Cross-sectional and longitudinal |

|

Logistic regression: no significant association between sexual

abuse and ADHD (OR = 1.44, p =

.59) Confounding factors included: wave (time), study site (New York, Puerto Rico), age, gender (except for stratified analyses), household education and income band, any parental psychopathology, and having taken ADHD medication (time-varying) |

| Gul & Gurkan (2018) | Investigate child and parent factors contributing to maltreatment in children with ADHD | Children with ADHD (n = 100) and a comparison

group without ADHD (N = 100) Children were between 6 and 11 years old (M = 8.4 years, SD = 0.88 years); 73% male |

Turkey Case-control |

|

Bivariate analysis: no significant differences in sexual abuse

between ADHD and control groups |

| Hébert et al. (2006) | Conduct a cluster analysis to identify profiles of children who

had been sexually abused |

123 Children (110 girls and 13 boys) 7 and 13 years old (M = 9.22, SD = 1.53) |

Canada Cluster analysis, case-control study |

|

Cluster analysis: results revealed four clusters of sexually abused children. Three of the four clusters of sexually abused children had higher scores of attention problem than non-abused children (p < .05) |

| Jaisoorya et al. (2016) | Study the prevalence of self-reported ADHD |

7,150 Final sample; 3,631 (50.8%) were boys and 3,519 (49.2%) were girls with a mean age of 15.3 years (range = 12–19 years) | India Cross-sectional |

|

Logistic regression: students with ADHD combined type compared with the non-ADHD group had higher odds of reporting contact sexual abuse (OR = 3.63 [2.56, 5.15]) |

| Kaplow et al. (2008) | Investigate attention problems in children who have experienced

sexual abuse and the roles of gender, trauma, and

disclosure |

129 Girls and 27 boys (mean age = 10.7 years) | United States Longitudinal |

|

Bivariate analysis: significantly higher mean attention score

among children abused by someone within the family compared to

those abused by someone outside of the family Path analysis revealed that intrafamilial abuse significantly predicted greater attention problems (β = .23) Confounding factors included: dissociation and time to follow-up from T1 to T2 |

| McLeer et al. (1994) | Comparing the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among sexually

abused and non-abused children |

26 Sexually abused children (mean age = 9) referred to sexual

abuse clinic for psychiatric evaluation 23 Nonsexually abused children (mean age = 10.4) recruited from an outpatient department |

United States Cross-sectional |

|

Bivariate analysis: ADHD was the most prevalent psychiatric disorder diagnosed in children who had been sexually abused, though the difference between sexually abused and nonsexually children was not statistically significant |

| Ohlsson et al. (2018) | To examine whether ADHD symptoms predict self-reported CSA at

age 18 |

4,500 Children participated: 1,902 males, 2,598

females 18 males and 256 females reported sexual victimization |

Sweden Prospective longitudinal, population-based - Child and Adolescent Twin Study |

|

Logistic regression: females with clinical ADHD had higher risk

of experiencing sexual abuse (OR = 2.02,

p < .05); same pattern for males, but

not statistically significant Confounding factor included: overall neurodevelopmental disorder symptoms (autism spectrum and ADHD) |

| Ozbaran et al. (2009) | Evaluating the effects of sexual abuse on children |

20 Parents and children followed for 2 years 9 Girls and 11 boys between the ages of 5 and 16 (M = 9.4) |

Turkey Longitudinal |

|

Bivariate analysis: in comparison to Turkish norms, the sexually abused group of children had significantly higher attention problems both in the first year (p < .001) and third year assessment (p < .01) |

| Ruggiero et al. (2000) | Examine predictors of psychopathology in sexually abused

children |

Primarily African-American sample (84%) 65 Females and 15 males (mean age = 9.4 years) |

United States Cross-sectional study part of a larger longitudinal study |

|

Descriptive analysis: higher scores in attention problems were

associated with a higher frequency of sexual abuse (also

included: gender, age at onset, severity, duration, and

perpetrator type) Confounding factor included: physical abuse history |

| Sonnby et al. (2011) | Examine the prevalence of ADHD and depression in individuals

with experiences of sexual abuse |

All secondary school students (15–16 and 17–18 years old) n = 4,910 (2,473 boys and 2,437 girls) |

Sweden Survey—Survey of Adolescent Life |

|

Logistic regression: ADHD boys, OR = 1.938, CI

[1.184, 3.171] ADHD girls, OR = 2.577, CI [1.732, 3.835] Confounding factors included: separated parents, parental unemployment, type of housing, and non-Scandinavian ethnicity |

| Walrath et al. (2003) | Investigate behavior and functioning in children (aged 5–17.5

years) with histories of sexual abuse |

759 Children with a history of sexual abuse; 2,722 children without sexual abuse history | United States Cross-sectional |

|

Logistic regression: child sexual abuse was associated with

lower rates of ADHD compared to children with no history of

sexual abuse (17.4% vs. 26.7%; OR = 0.58,

SE = .06, p <

.01 For child ratings on CBCL, there was no significant difference between those with and without sexual abuse histories in terms of attention problems (OR = 1.19, SE = .18). For caregiver ratings, there was a significant difference in attention problems for children with and without sexual abuse histories (OR = 1.22, SE = 10, p < .05) Confounding factors included: demographic (gender, age, and race); life challenges (psychiatric hospitalization, physical abuse, runaway attempts, suicide attempts, drug/alcohol use, and sibling in foster care) |

| |||||

| Afifi et al. (2014) | Using a nationally representative sample, examine the relation

between child abuse and mental health |

Canadians aged 18 or older (n = 23,395) | Canada Cross-sectional |

|

Logistic regression: CSA-ADD − OR1 (95% CI) = 2.9 [2.1, 4.0] CSA-ADD − OR2 (95% CI) = 1.7 [1.2, 2.4] OR1 confounding factors included: adjusted for age, sex, visible minority status, Canadian born status, education, income, marital status, and province OR2 Confounding factors included: adjusted for sociodemographic variables listed above, other types of child abuse and any diagnosed mental disorders |

| Ebejer et al. (2012) | Identifying the prevalence of ADHD and exposure to childhood

risk factors |

1,369 Men and 2,426 women, recruited through the National Health and Medical Research Council Twin Registry | Australia Twin study, cross-sectional |

|

Logistic regression: sexual abuse during childhood significantly

predicted inattentive and hyperactivity-impulsive symptoms

(p > .001 and p >

.01, respectively) Confounding factors included: conduct problems included in the regression as a covariate. Other confounding factors included childhood SES, family structure, conflicts with parents, parental arguing, parental tension, parental drinking, and parental rules |

| Ferrer et al. (2017) | Compare maltreatment history among adults with ADHD, BPD, and

comorbid ADHD with borderline |

204 Patients with BPD clinical features 170 (83.3%) women (mean age = 31.17, SD = 9.61; clinical population) |

Spain Cross-sectional |

|

Bivariate analysis: women with BPD and ADHD

have higher scores of CSA than women without BPD

and without ADHD: t(98) =

2.29, p = .02 No significant differences between women with ADHD only and women without BPD and without ADHD (p > .05) Logistic regression: emotional abuse (β = .18), physical abuse (β = −.22), and sexual abuse (β = .15) predicted combined BPD-ADHD diagnosis Confounding factor included: gender |

| Fuller-Thomson and Lewis (2015; same sample as Afifi et al., 2014) | Examine retrospectively reported abuse |

10,496 Men and 12,877 women from the Canadian Community Health

Survey-Mental Health |

Canada Cross-sectional |

|

Logistic regression: sexual abuse was significantly related to

higher odds of having ADHD (men OR = 2.57,

p < .001; women OR =

2.55, p < .001) Confounding factors included age and gender; logistic regression analysis adjusted for parental domestic abuse and physical abuse |

| Fuller-Thomson et al. (2016; same sample as Afifi et al., 2014) | Develop a profile of women with self-reported ADHD in comparison

to those without ADHD |

Women between the ages of 20 and 39 drawn from the 2012 Canadian

Community Health Survey—Mental Health 107 Women self-reported diagnosis of ADHD; 3,801 not diagnose with ADHD |

Canada Cross-sectional |

|

Descriptive analysis; prevalence of CSA: no ADHD: 10.9%

p < .001 ADHD: 35.8%, p < .001 This difference was significant |

|

Jaisoorya

et al. (2019)

|

Document prevalence of retrospectively recalled symptoms of

ADHD |

5,145 College students, 1,750 (34.8%) were men and 3,395 (65.2%)

were women (mean age = 19.4) -143 Participants with ADHD (67 male, 76 female); 5,002 non-ADHD participants (1,716 male; 3,286 female) |

India Cross-sectional |

|

Logistic regression: participants with clinically significant

ADHD symptoms had higher odds of contact (OR =

3.10) and non-contact sexual abuse (OR = 3.29)

Confounding factors included: sex and residence |

| Matsumoto & Imamura (2007) | Examine associations between ADHD and dissociation in

inmates |

799 Male inmates (mean age = 23.7 years); 94 participants reported CSA | Japan Cross-sectional |

|

Bivariate analysis: ADHD symptoms were significantly higher in

participants who reported CSA than those who did not

(p < .001) |

| Ouyang et al. (2008) | Examine the associations between ADHD during childhood and child

maltreatment |

14,322 Youths interviewed twice During Wave 3, participants ranged in age from 18 to 28 years (mean age = 21.8 years) |

United States Longitudinal, population-based—National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health |

|

Logistic regression: ADHD (all types together):

OR = 2.31, p <

.001) Inattentive type: OR = 2.61, p < .001 Combined type: OR = 2.90, p < .001 All three ADHD categories were associated with contact sexual abuse Confounding factors included: race, sex, age cohort, family structure, whether the mother was a teenager when the child was born, whether the biological father was ever jailed, parent education level, and family size adjusted poverty status |

| Rucklidge et al. (2006) | Investigate the prevalence of child abuse in individuals who

were identified with ADHD in adulthood, and the impact of ADHD

and abuse on psychosocial functioning |

-Only participants who believed they had problems with attention

when they were children not diagnosed with ADHD until

adulthood -114 Participants: 17 men and 40 women with ADHD; 40 men and 17 women without ADHD |

Canada Cross-sectional |

|

Bivariate analysis: -23.1% of women with ADHD and 12.5% of men with ADHD reported experiencing moderate to severe sexual abuse -Females who experienced sexual abuse had higher ADHD scores compared to the three other groups (female controls, male controls, and males with ADHD) Confounding variables included: SES |

| Sanderud et al. (2016) | Investigate the relationship between child maltreatment and ADHD

in adulthood |

Sample of 4,718 young adults (24 years of age). Interviews conducted with 2,980 participants | Denmark Cross-sectional, national study |

|

Logistic regression: sexual abuse predicted probable ADHD (OR = 2.07, p < .05) |

|

White &

Buehler (2012)

|

Examine the association between ADHD symptoms experienced before

age 12 and sexual victimization during adolescence |

Subsample of 374 participants (mean age = 18.9 years,

SD = 2.90) who did not experience sexual abuse before age 13; 43 participants had experienced child sexual abuse |

United States Cross-sectional |

|

Mediation analyses: ADHD symptoms were associated with greater

sexual victimization experiences (Sobel t =

2.67, p = .007) and were linked to sexual

victimization through risky sexual behaviors Moderators included: SES, primary caregiver employment status, race, and family structure. Association between ADHD and sexual victimization was stronger for Black women |

| White et al. (2014; same sample as White & Buehler, 2012) | To investigate the mediating effects of risky behaviors in the

association between child ADHD and adolescent sexual

victimization |

417 Women recruited through university psychology classes (mean age = 18.90 years, SD = 2.90) | United States Cross-sectional |

|

There was a significant direct association between childhood

ADHD symptoms and adolescent sexual victimization (β =

.15) Risky sexual behavior explained the association between ADHD symptoms and adolescent sexual victimization Moderation analysis showed consensual sexual activity and staying out all night interacted with ADHD to increase risky behavior and sexual risk-taking Confounding factors included: early onset of alcohol or marijuana use, consensual sexual activity, and staying out all night interacted with childhood ADHD symptoms to increase general risky behavior and sexual risk-taking |

Note. OR = odds ratio; ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CSA = child sexual abuse; CTQ-SF: Conflict Tactics Scale-Short Form; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self Report; YASR = Young Adult Self Report; K-SADS-PL-T = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; DISC-IV = Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV; CRS = Conners’ Rating Scales; BAARS-IV = The Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale–IV; BPD = borderline personality disorder; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; SES = socioeconomic status.

CSA as a Predictor of ADHD—Adult Samples (n = 7)

Two studies conceptualizing CSA as a risk factor for ADHD and using adult samples only provided bivariate associations. In their study of male inmates (n = 799), Matsumoto and Imamura (2007) found that ADHD symptoms were higher for sexually abused than nonabused men. According to Sanderud et al. (2016; n = 2,980, community sample), young adults with a history of CSA were 2.07 times more likely to report ADHD than nonabused adults.

Five of the seven studies with adult samples conceptualizing CSA as a predictor of ADHD included potentially confounding factors in their analyses; all but one identified significant associations between CSA and ADHD. Using a representative sample of Canadian adults (n = 23,395, population-based sample), Afifi et al. (2014) showed that CSA victims were 1.7 times more at risk of reporting suffering from attention deficit disorder (inattentive subtype of ADHD) than nonvictims after controlling for sociodemographic factors, other types of child abuse, and any diagnosed mental disorders, including PTSD. Using the same sample, Fuller-Thomson and Lewis (2015; n = 10,496 men, 12,877 women; population-based sample) found that both men and women were around 2.5 times more likely to have attention deficit disorder (renamed ADHD by the authors) if they reported a history of CSA, after controlling for age, parental domestic abuse, and physical abuse. After accounting for conduct problems and various childhood factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, parental conflicts and rules, family structure), CSA significantly predicted ADHD symptoms in another study (Ebejer et al., 2012; n = 3,795, community sample). Women with borderline personality disorder and ADHD had higher scores of CSA than women without borderline personality and ADHD, while women only reporting ADHD did not differ in terms of CSA scores from women without ADHD and borderline personality (Ferrer et al., 2017; n = 204, clinical sample). In this study, combined ADHD and borderline personality was significantly and uniquely predicted by childhood emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. Finally, the only study including confounding variables that did not show a significant association between CSA and ADHD in their adult sample is Boyd et al. (2019; n = 7,214, community sample). In this longitudinal study, CSA did not predict self-reported attention problems at 21 years old in bivariate analyses and multiple regressions controlling for several sociodemographic factors, birthweight, maternal depression, and other child maltreatment types.

CSA as a Predictor of ADHD—Child Samples (n = 9)

Three studies conceptualizing CSA as a predictor of ADHD with child samples documented bivariate associations. Comparing hyperactivity scores in their sample of sexually abused children (n = 112, clinical sample) to the sample used to create the norms of the measure used, Gomes-Schwartz et al. (1985) identified a positive association with CSA. In comparison to the Turkish norms, another study found higher scores of attention problems (hyperactivity not measured) in sexually abused children over a 3-year period (Ozbaran et al., 2009; n = 20, clinical sample). In contrast to the findings in these clinical samples, González et al. (2019) found no associations between CSA and ADHD in their Latino community sample (n = 2,480).

Of the nine studies conceptualizing CSA as a predictor of ADHD using a child sample, six considered potential confounding factors; all but one found significant associations. In their longitudinal study, Boyd et al. (2019) found that after accounting for several sociodemographic factors and other maltreatment types, CSA was associated with more attention problems (hyperactivity not measured) at 14 years old as documented using parent reports, but not youth reports. Walrath et al. (2003; n = 759 children with CSA; 2,722 children with no CSA; clinical sample), after accounting for demographics (gender, age, and race) and life challenges (psychiatric hospitalization, physical abuse, runaway attempts, suicide attempts, drug/alcohol use, sexual abuse, and sibling in foster care), also had different results depending on the respondent for ADHD symptoms. Based on clinicians’ ratings of primary diagnosis, children with a history of sexual abuse had lower rates of ADHD than nonabused children. However, the relation was reversed when using caregivers’ reports of attention problems using the Child Behavior Checklist, and no difference was found when using children’s ratings. Sonnby et al. (2011) found that boys and girls (n = 4,910, community sample) were more likely to have symptoms of ADHD if they were sexually abused, even after accounting for familial and sociodemographic factors, although this association was stronger among girls. Two studies examined the impact of CSA characteristics. One of them showed that while controlling for dissociation, intrafamilial abuse was associated with greater attention problems (hyperactivity not measured) than extrafamilial abuse (Kaplow et al., 2008; n = 127, clinical sample). The other showed that when gender, age at onset of the CSA, severity, frequency, duration, perpetrator type, and physical abuse history were considered, children with higher frequencies of CSA had more attention problems (hyperactivity not measured; Ruggiero et al., 2000; n = 80 children with CSA, community sample). Finally, the one study that did not identify CSA as a significant predictor of ADHD symptoms was Ford et al. (2009; n = 397, residential treatment sample). In their analyses, they controlled for several potential confounding factors including gender, ethnicity, other mental disorders (psychotic, internalizing and externalizing, developmental, and substance use), complex traumatic experiences, parental impairment, placement history, and physical abuse.

ADHD as a Predictor of CSA—Adult Samples (n = 4)

All studies using an adult sample and conceptualizing ADHD as a risk factor for CSA accounted for potential confounding factors, and all uncovered significant associations. Adjusting only for gender and place of residence, Jaisoorya et al. (2019) found that the risk of contact and noncontact sexual abuse in college students (n = 5,145, community sample) with clinically significant ADHD symptoms was three-fold as compared to non-ADHD students. While controlling for several sociodemographic and family factors, Ouyang et al. (2008) found that ADHD inattentive and combined types were associated with an increased risk of contact sexual abuse (n = 14,322, population-based sample). Finally, two studies using the same sample of young women recruited through university psychology classes (n = 417, community sample; White & Buelher, 2012; White et al., 2014) found that after accounting for sociodemographic variables, ADHD symptoms were associated with greater sexual victimization experiences during adolescence and that this association was mediated by risky sexual behaviors.

ADHD as a Predictor of CSA—Child Samples (n = 4)

Conducting only bivariate analyses, Gul and Gurkan (2018) found no differences in CSA rates between the ADHD (n = 100) and control group (n = 100) in their Turkish clinical sample. Gokten et al. (2016) also found no difference in rates of CSA between children with (n = 104) and without ADHD (n = 104; clinical sample). Conversely, Jaisoorya et al. (2016; n = 7,150, community sample) found that teenagers with ADHD combined type (inattention and hyperactivity) had higher odds (odds ratio [OR] = 3.63) of contact sexual abuse than non-ADHD teenagers.

One study using a child sample and conceptualizing ADHD as a predictor of CSA included potential confounding factors in their analyses. Ohlsson et al. (2018; n = 4,500, population-based) found that girls with clinical ADHD had two times the risk of being sexually abused when compared to non-ADHD girls. A similar pattern was found with boys, but it was nonsignificant. Ohlsson et al. (2018) only controlled for overall neurodevelopmental disorder symptoms as potential confounding factors in these analyses.

CSA and ADHD as Comorbid Problems—Adult Samples (n = 2)

No study conceptualizing CSA and ADHD as comorbid problems, without clear directionality, and using an adult sample included potential confounders in their analyses. Fuller-Thomson et al. (2016) found a significant difference in prevalence rates of CSA among adult women with (n = 107) and without ADHD (n = 3,801, subsample from the population-based sample used by Afifi et al., 2014). Rucklidge et al. (2006) reported a positive association between ADHD scores and CSA among women (n = 114, community sample).

CSA and ADHD as Comorbid Problems—Child Samples (n = 3)

Among the three studies documenting the association between CSA and ADHD without clear hypothesized directionality and using child samples, none included covariates. Ford et al. (2000; n = 165, clinical sample) found positive associations between ADHD and sexual abuse, with the highest rate being among children with both ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder. In their cluster analysis study, Hébert et al. (2006) found that three of the four clusters of sexually abused children (n = 123, clinical sample) had higher scores of inattention (hyperactivity not measured) than the comparison group of nonabused children (n = 123, community sample). Finally, McLeer et al. (1994) failed to identify a significant association between ADHD diagnosis and sexual abuse in their small clinical sample (n = 26 sexually abused children, 23 nonsexually abused children).

Methodological Quality of Reviewed Papers

The methodological quality of the 28 studies included in this review varied greatly. Of all of the articles, seven were rated highly (Afifi et al., 2014; Boyd et al., 2019; González et al., 2019; Ruggiero et al., 2000; Sonnby et al., 2011; White & Buehler, 2012; White et al., 2014), nine fairly (Ebejer et al., 2012; Ferrer et al., 2017; Fuller-Thomson & Lewis., 2015; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016; Jaisoorya et al., 2016; Kaplow et al., 2008; Ohlsson et al., 2018; Ozbaran et al., 2009; Sanderud et al., 2016), nine poorly (Ford et al., 2000; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016; Gomes-Schwartz et al., 1985; Gul & Gurkan, 2018; Hébert et al., 2006; Jaisoorya et al., 2019; Matsumoto & Imamura, 2007; McLeer et al., 1994; Rucklidge et al., 2006; Walrath et al., 2003), two fell between fair and poor (Ford et al., 2009; Ouyang et al., 2008), and one between fair and good (Gokten et al., 2016). The main limitations related to the design, the sample, the measures, and the statistical analyses. Almost all studies had cross-sectional designs (n = 27), and only one study was prospective longitudinal (Boyd et al., 2019), the most robust design for determining an association between CSA and ADHD. In addition, the outcome assessors were often unblinded to the CSA status of the participants (n = 23) which could have biased their assessment of ADHD symptoms. Of the 28 studies, only two presented a justification for their sample size in the form of a power analysis. Of the 26 studies that did not, eight had large samples which did not raise concerns over statistical power considerations, leaving a subsample of 18 studies that might have been underpowered. On the other hand, most studies (n = 23) recruited participants from the same or similar populations (including the same time period) with predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria that were consistently applied to all participants.

Regarding the measures, in over half (n =17) of the studies, the CSA measure were considered valid and reliable while 10 were not. Additionally, for one study, due to unclear information about the measures, it was not possible to determine whether the CSA measure used was valid. For 23 of the studies, the ADHD measure was considered valid and reliable, with only five studies that did not reach such standards. Moreover, for the assessment of CSA, 23 studies used questionnaires and parent-report and/or child self-report measures whereas five studies used more robust methods of assessment such as chart reviews or corroborated cases by child protective services. For the assessment of ADHD, 26 studies used questionnaires and parent-report, teacher-report, and/or child self-report measures whereas two studies used more robust measures, such as diagnosis by a clinician.

In terms of the analyses performed to examine the associations between ADHD and CSA, confounding variables of other maltreatment types and sociodemographic/other variables (e.g., sex, age, family structure, and income) were adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship in only eight studies. In 17 studies, either sociodemographic/other variables or other maltreatment types were controlled for, and in most of these cases, it was the sociodemographic factors that were included. Only one study controlled for the presence of PTSD (Afifi et al., 2014); one study controlled for dissociation symptoms (Kaplow et al., 2008). Three studies only conducted bivariate analysis to document the association between CSA and ADHD.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized and critically assessed the methodological quality of available research on the association between CSA and ADHD. Over the past 35 years, 12 studies documented these associations using an adult sample, 15 using a child or adolescent sample, and one had a longitudinal design encompassing both adolescence and early adulthood (Boyd et al., 2019). Most studies (82%) uncovered significant associations between CSA and ADHD or ADHD symptoms and, surprisingly, this proportion did not differ much depending on the number of confounding factors included in the main analyses. A little over half of the studies reviewed (57%) included at least one potentially confounding factor in their examination of the associations between CSA and ADHD, but only 21% of included studies controlled for other maltreatment types, despite the well-documented high rates of co-occurrence between different forms of child maltreatment and family adversity (e.g., Turner et al., 2010). The most frequent confounding factors incorporated were sociodemographic factors and family characteristics such as family size, parental conflicts, and parental psychopathology. Comorbid psychiatric disorders were also controlled for in 17.8% (n = 5) of included studies, and only two studies (7.1%) controlled for PTSD or trauma-related symptoms (i.e., dissociation), consequently limiting greatly our ability to disentangle the associations between CSA, ADHD, and trauma symptoms. More than half of the included studies were based on samples from the United States or Canada (see Table 1 study setting for the list of countries). Associations would need to be explored further in more diverse samples and samples from other countries which might have varying rates of ADHD and CSA. Indeed, cross-cultural studies have inconsistent findings, some showing similar rates of ADHD across cultures (Bauermeister et al., 2010; Polanczyk et al., 2014), and others showing overrepresentation of some ethnic groups (e.g., African American, Hispanic American) in children diagnosed with ADHD (Flowers & McDougle, 2010; Gomez-Benito et al., 2019). CSA is also known to have highly varying rates globally (Stoltenborgh et al., 2011).

Furthermore, we were unable to clarify the directionality of the association between CSA and ADHD. A little over half of studies conceptualized CSA as a risk factor for ADHD (53%), while 29% conceptualized ADHD as a risk factor for future CSA, and a minority of studies (18%) did not make clear assumptions regarding the temporal association between these variables. While there seems to be a tendency to consider CSA a risk factor for the development of ADHD symptoms, only one study had an appropriate design—prospective longitudinal—to ascertain such directionality (Boyd et al., 2019). According to Boyd et al.’s (2019) findings, CSA only predicts ADHD symptoms in adolescence when parental reports are used.

Recently, Craig et al. (2020) published a systematic review on child maltreatment and ADHD and reported only five longitudinal studies, showing that early maltreatment is a risk factor for developing ADHD symptoms later on. However, the authors note that these findings are not consistent. Whereas some studies reported maltreatment predicting attention problems (Thompson & Tabone, 2010), the associations were not as clear in other studies. For example, Stern et al. (2018) found ADHD and maltreatment associations concurrently across development. Relevant to the topic of this review, dissociative symptoms are common following sexual abuse (Trickett et al., 2011) and can make differential diagnosis difficult, especially in children, since periods of dissociation may cause children to appear dazed, inattentive, and unfocused in the classroom (Ford & Courtois, 2013). On the other hand, Lugo-Candelas et al. (2020) highlight that the reverse relationship of ADHD predicting adverse experiences has been understudied. Based on a longitudinal population-based study, they found that children with ADHD at Wave 1, specifically the inattentive, were more likely to experience adverse childhood experiences later on. Based on a sample of adults with childhood histories of ADHD (n = 97) and a comparison group of adults with no ADHD history (n = 121), Wymbs and Gidycz (2020) also reported that those with ADHD histories were more likely to experience sexual assault, assessed at or after the age of 14. Although these findings contribute to the literature on ADHD as a risk factor for abuse, this was a cross-sectional study and sexual abuse before the age of 14 was not analyzed.

While some included studies were rated strongly, there are several other limitations that were uncovered through the systematic assessment of the methodological quality of the available research, and these limitations compromise even further our ability to untangle the associations between CSA and ADHD based on the current evidence base. Hence, only a quarter of included studies was rated as high quality regarding the pursued objectives of the current review. Highly ranked studies had strengths such as large and representative samples and validated measures of CSA and ADHD (e.g., structured interviews, multiinformant measurement, validated questionnaires), in addition to using appropriate statistical analysis controlling for major confounders (e.g., other traumatic events, trauma symptoms). One third of included studies were rated as fair or good-to-fair, meaning that they had some important limitations regarding their sample (e.g., small, unrepresentative), recruitment procedures (e.g., convenience sampling), measures (e.g., unvalidated, self-report only), or statistical procedures (e.g., few confounding factors included). Finally, 40% of included studies were considered poor or poor-to-fair quality, highlighting major limitations such as the use of small, unrepresentative samples, unclear methods limiting reproducibility, unvalidated measures of ADHD and CSA, and poor control for confounding factors such as sociodemographic factors, other maltreatment types, and mental health symptoms.

In addition to these general ratings, it is worth mentioning that even though a gold standard assessment of ADHD usually requires a structured battery of neuropsychological tests, parent and teacher reports, and in-depth clinical interviews to avoid misdiagnoses (Wolraich et al., 2011), almost all studies included in this review based their assessment of one or two informants using questionnaires. Thus, risks of confusion between actual ADHD symptoms and symptoms related to other psychopathologies (e.g., anxiety, mood; Mao & Findling, 2014) or typical reactions to psychosocial stressors or traumatic experiences (Szymanski et al., 2011), especially in the context of the study of CSA (Mii et al., 2020), are extremely high. Findings from Walrath et al. (2003) seem to confirm this risk of misdiagnosis when using self- or parent-report measures of ADHD instead of official diagnoses from clinicians. Indeed, they found that nonsexually abused children, when compared to abused children, were at higher risk of having ADHD as a primary diagnosis given by a clinician, while parent reports indicated higher attention problems in sexually abused children. This could be explained by the fact that clinicians are better able to discriminate between trauma and ADHD symptoms than parents, but also by the fact that questionnaires, such as the Child Behavior Checklist, do not offer enough sensitivity and contextualization to allow determining the cause behind the observed behavior, increasing the risk of mislabeling symptoms (e.g., labeling dissociation symptoms as attention deficit). However, an alternative explanation might be that clinicians misinterpret ADHD symptoms as trauma symptoms when assessing sexually abused children. Finally, the measurement of CSA was also problematic in several studies. Indeed, given problems with the sole use of retrospective recall or single question assessments (e.g., memory, underreporting), but also the limitations of relying only on official child protection records (e.g., major underreporting), a multimethod assessment is desirable (Baldwin et al., 2019); none of the studies used such an approach.

In light of these major limitations, several recommendations may be made. First, there is a pressing need for prospective longitudinal studies documenting the associations over time of CSA and ADHD. Only such studies could clarify the temporal relationship between CSA and ADHD and might even show that transactional processes are at play between these two variables. For example, ADHD could increase the risk of being sexually abused, and in turn, CSA could increase already existing ADHD symptoms; or CSA could lead to ADHD symptoms that in turn increase someone’s risk of later sexual revictimization. Second, there needs to be rigorous assessment of both CSA and ADHD in participants, including differential diagnosis using neuropsychological tests for ADHD, and the integration of both self- and parent reports of CSA using validated questionnaires or interviews, and official child protection services data which would necessitate the use of clinical samples. Complementary to fine-grained analyses of clinical samples, there is a need for large and representative samples to minimize selection bias and ensure appropriate statistical power, and for cross-cultural studies or studies with diverse samples. Finally, studies should assess and control major confounding factors such as other forms of child maltreatment and family adversity, sociodemographic and cultural factors, and comorbid psychopathologies, especially trauma-related symptoms (e.g., PTSD, dissociation). The consideration of the potential impact of CSA characteristics, and even of the characteristics of the other maltreatment experiences where applicable, could also be appropriate given findings from Kaplow et al. (2008) and Ruggiero et al. (2000).

Our review itself is not without limitations. Despite our efforts to ensure every relevant study would be included (e.g., including every major database related to the topic, having our search strategy peer-reviewed), there is always a risk of missing some due to the selection of databases, the search strategy used, or mistakes during the screening process. Also, we did not include gray literature and unpublished dissertations older than 5 years. Further, we were not able to combine the studies using a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of included papers in terms of measures, samples, and designs. Therefore, we are not able to test for impactful moderators or to determine the strength of the association between CSA and ADHD.

Implications and Conclusion

In line with research on this topic, clinicians have also reported on the associations between CSA and ADHD (Burke Harris, 2018). Our rigorous systematic review revealed 28 studies. Of those, 16 were rated as at least fair using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies; only one was longitudinal in nature and was highly rated in terms of quality; only two controlled for trauma-related symptoms, one of which was highly rated and one of which was fair. Although most studies pointed to a general link between CSA and ADHD, clearly, high quality, controlled, longitudinal evidence is sparse at best. Implications are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy.

| Implications for research |

|

| Implications for practice |

|

| Implications for policy |

|

Given the paucity of research in this area, it is difficult to make specific clinical recommendations. Nevertheless, clinicians working with victims of CSA or individuals with ADHD symptoms should be aware of possible comorbidities. Although research has not been able to address directionality of these different problems, or disentangle the effect of trauma symptomatology, that does not mean that individual clinicians cannot address these issues with clients on a case-by-case basis. One method that could be used is rigorous testing for ADHD using neuropsychological batteries and in-depth interviews to establish the time line between these problems and identify other trauma symptoms, schizophrenia, or psychotic disorders (Burke Harris, 2018). If CSA occurred before ADHD symptoms appeared, it might be relevant to undergo a detailed differential diagnosis process to ensure that trauma-related symptoms are not mislabeled as ADHD, so appropriate treatment can be offered (Craig et al., 2020). In cases of real comorbidity between CSA and ADHD, it could be appropriate to formulate a treatment plan, in collaboration with the affected individual, that could address both of these issues concurrently or in sequence based on collaborative priority rating among interested parties (e.g., the practitioner, the parent, and the child; the practitioner and the individual). Clinical guidelines for treating ADHD and PTSD are available; however, guidelines are lacking when it comes to treating the comorbidity of these problems (Barnett et al., 2018).

Finally, given the adverse and persisting effects that both CSA and ADHD can have on children and adults, this area of research requires further development. Longitudinal studies with diverse samples using validated and multimethod measures of both CSA and ADHD would be particularly beneficial to advancing the state of knowledge.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Dr. Tracie Afifi, University of Manitoba, for the revision of the search strategy.

Author Biographies

Rachel Langevin is a psychologist and an assistant professor in the Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology at McGill University. Her research focuses on the impacts of family violence on the socioemotional development of children and adolescents with a particular interest in identifying the mechanisms involved in the intergenerational continuity of trauma and violence.

Carley Marshall is a PhD student in the School/Applied Child Psychology program at McGill University. She is interested in child trauma and resilience. Her research is focused on the intergenerational continuity of child sexual abuse to identify multilevel risk and protective factors.

Aimée Wallace completed an undergraduate degree in psychology at McGill University. She is now completing a masters in sexology at Université du Québec à Montréal. Her research focuses on the risk factors associated with cyber victimization in the dating relationships of sexually abused teenage girls.

Marie-Emma Gagné completed a master’s degree in counselling psychology. She is currently a PhD student in counselling psychology. Her research interests are trauma-related disorders and the intergenerational transfer of risk.

Emily Kingsland is an associate librarian at McGill University Library and Archives, where she specializes in educational and counselling psychology, and psychology. She holds a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Library and Information Studies, both from McGill University.

Caroline Temcheff is a psychologist and an associate professor in the Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology at McGill University. Her research focuses on longitudinal trajectories of mental health problems and health service utilization among boys and girls with and without conduct problems.

Appendix

| Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL <1946 to January 8, 2020 > | |

|---|---|

| # | Search Statement |

| 1 | exp Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity/ |

| 2 | exp “Attention Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders”/ |

| 3 | exp Central Nervous System Stimulants/ |

| 4 | exp Child Behavior Disorders/ |

| 5 | adhd.mp. |

| 6 | “attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity”.mp. |

| 7 | “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder”.mp. |

| 8 | “attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder”.mp. |

| 9 | “attention deficit disorder”.mp. |

| 10 | (attention adj3 deficit).mp. |

| 11 | addh.mp. |

| 12 | (ad hd or ad?? hd).mp. |

| 13 | “Attention Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders”.mp. |

| 14 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 |

| 15 | exp Rape/ |

| 16 | exp Incest/ |

| 17 | exp Sex Offenses/ |

| 18 | exp Pedophilia/ |

| 19 | exp Sex/ |

| 20 | exp Violence/ |

| 21 | 19 and 20 |

| 22 | exp Crime Victims/ |

| 23 | 19 and 22 |

| 24 | exp Child Abuse, Sexual/ |

| 25 | (sex$ adj3 abuse$).mp. |

| 26 | incest$.mp. |

| 27 | (sex$ adj3 child$).mp. |

| 28 | (sex$ adj3 offens$).mp. |

| 29 | molest$.mp. |

| 30 | rape$.mp. |

| 31 | (sex$ adj3 crim$).mp. |

| 32 | (sex$ adj3 abuse$).mp. |

| 33 | (sex$ adj3 assault$).mp. |

| 34 | (sex$ adj3 offen$).mp. |

| 35 | (sex$ adj3 exploit$).mp. |

| 36 | (sex$ adj3 victim$).mp. |

| 37 | (sex$ adj3 coerc$).mp. |

| 38 | (sex$ adj3 maltreat$).mp. |

| 39 | (groom$ adj3 sex$).mp. |

| 40 | (Sex$ adj3 violen$).mp. |

| 41 | (sex$ adj3 trauma).mp. |

| 42 | 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 21 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 |

| 43 | 14 and 42 |

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Rachel Langevin  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7671-745X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7671-745X

References

- Afifi T. O., MacMillan H. L., Boyle M., Taillieu T., Cheung K., Sareen J. (2014). Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186 (9), 324–332. 10.1503/cmaj.131792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anda R. F., Felitti V. J., Bremner J. D., Walker J. D., Whitfield C., Perry B. D., Dube S. R., Giles W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience, 256, 174–186. 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assink M., van der Put C. E., Meeuwsen M. W. C. M., de Jong N. M., Oort F. J., Stams G. J. J. M., Hoeve M. (2019). Risk factors for child sexual abuse victimization: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5), 459–489. 10.1037/bul0000188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J. R., Reuben A., Newbury J. B., Danese A. (2019). Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(6), 584–593. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R. A., Murphy K. R. (1998). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A clinical workbook. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett E. R., Cleary S. E., Neubacher K., Daviss W. B. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorders and ADHD. In Daviss W. B. (Ed.), Moodiness in ADHD: A clinician’s guide (pp. 55–72). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister J. J., Canino G., Polanczyk G., Rohde L. A. (2010). ADHD Across Cultures: Is There Evidence for a Bidimensional Organization of Symptoms? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(3), 362–372. 10.1080/15374411003691743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berliner L. (2011). Child sexual abuse: Definitions, prevalence, and consequences. In Myers J. E. B. (Ed.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (3rd ed., pp. 215–232). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M., Kisely S., Najman J., Mills R. (2019). Child maltreatment and attentional problems: A longitudinal birth cohort study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke Harris N. (2018). The deepest well: Healing the long-term effects of childhood adversity. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. P., Murad M. H., Paras M. L., Colbenson K. M., Sattler A. L., Goranson E. N., Elamin M. B., Seime R. J., Shino zaki G., Prokop L. J., Zirakzadeh A. (2010). Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 85, 618–629. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S. G., Bondi B. C., O’Donnell K. A., Pepler D. J., Weiss M. D. (2020). ADHD and exposure to maltreatment in children and youth: A systematic review of the past 10 years. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(12), 1–14. 10.1007/s11920-020-01193-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daignault I. V., Hébert M. (2009). Profiles of school adaptation: Social, behavioral and academic functioning in sexually abused girls. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 102–115. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle C., Cicchetti D. (2017). From the cradle to the grave: The effect of adverse caregiving environments on attachment and relationships throughout the lifespan. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 24, 203–217. 10.1111/cpsp.12192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul G. J., Power T. J., Anastopoulos A. D., Reid R. (1998). ADHD rating scale-IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Dvir Y., Ford J. D., Hill M., Frazier J. A. (2014). Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 22(3), 149–161. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebejer J. L., Medland S. E., van der Werf J., Gondro C., Henders A. K., Lynskey M., Martin N. G., Duffy D. L. (2012). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Australian adults: Prevalence, persistence, conduct problems and disadvantage. PLoS One, 7(10). 10.1371/journal.pone.0047404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer M., Óscar A, Calvo N, Ramos-Quiroga J. A., Prat M., Corrale M., Casas M. (2017). Differences in the association between childhood trauma history and borderline personality disorder or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnoses in adulthood. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 267(6), 541–549. 10.1007/s00406-016-0733-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers A., McDougle L. (2010). In search of an ADHD screening tool for African American children. Journal of the National Medical Association, 102(5), 372–374. 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30571-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J. D., Connor D. F., Hawke J. (2009). Complex trauma among psychiatrically impaired children: A cross-sectional, chart-review study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(8), 1155–1163. 10.4088/JCP.08m04783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J. D., Courtois C. A. (2013). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders in children and adolescents: Scientific foundations and therapeutic models. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ford J. D., Racusin R., Ellis C. G., Daviss W. B., Reiser J., Fleischer A., Thomas J. (2000). Child maltreatment, other trauma exposure, and posttraumatic symptomatology among children with oppositional defiant and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders. Child Maltreatment, 5(3), 205–217. 10.1177/1077559500005003001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E., Lewis D. A. (2015). The relationship between early adversities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child Abuse & Neglect, 47, 94–101. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E., Lewis D. A., Agbeyaka S. K. (2016). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder casts a long shadow: Findings from a population-based study of adult women with self-reported ADHD. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(6), 918–927. 10.1111/cch.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokten E. S., Saday Duman N., Soylu N., Uzun M. E. (2016). Effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 62, 1–9. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Schwartz B., Horowitz J. M., Sauzier M. (1985). Severity of emotional distress among sexually abused preschool, school-age, and adolescent children. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 36(5), 503–508. 10.1176/ps.36.5.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Benito J., Van de Vijver F. J. R., Balluerka N., Caterino L. (2019). Cross-cultural and gender differences in ADHD among young adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(1), 22–31. 10.1177/1087054715611748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González R. A, Vélez-Pastrana M. C, McCrory E, Kallis C, Aguila J, Canino G, Bird H. (2019). Evidence of concurrent and prospective associations between early maltreatment and ADHD through childhood and adolescence. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(6), 671–682. 10.1007/s00127-019-01659-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotby V. O., Lichtenstein P., La°ngstroüm N, Pettersson E. (2018). Childhood neurodevelopmental disorders and risk of coercive sexual victimization in childhood and adolescence—A population-based prospective twin study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(9), 957–965. 10.1111/jcpp.12884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gul H., Gurkan C. K. (2018). Child maltreatment and associated parental factors among children with ADHD: A comparative study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(13), 1278–1288. 10.1177/1087054716658123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpin V., Mazzone L., Raynaud J. P., Kahle J., Hodgkins P. (2016). Long-term outcomes of ADHD: A systematic review of self-esteem and social function. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(4), 295–305. 10.1177/1087054713486516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M., Langevin R., Daignault I. (2016). The association between peer victimization, PTSD, and dissociation in child victims of sexual abuse. Journal of Affective Disorders, 193, 227–232. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Parent N, Daignault I. V, Tourigny M. (2006). A typological analysis of behavioral profiles of sexually abused children. Child Maltreatment, 11(3), 203–216. 10.1177/1077559506287866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillberg T., Hamilton-Giachritsis C., Dixon L. (2011). Review of meta-analyses on the association between child sexual abuse and adult mental health difficulties: A systematic approach. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 12(1), 38–49. 10.1177/1524838010386812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irigaray T. Q., Pacheco J. B., Grassi-Oliveira R., Fonseca R. P., Leite J. C. C., Kristensen C. H. (2013). Child maltreatment and later cognitive functioning: A systematic review. Psicologia: Reflexão E Crítica, 26(2), 376–387. 10.1590/S0102-79722013000200018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irmak T. Y. (2008). Prevalance of child abuse and neglect and resilience factors [Doctoral thesis]. Ege University, Izmir, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Jaisoorya T. S., Beena K. V., Beena M., Ellangovan K., Jose D. C., Thennarasu K., Benegal V. (2016). Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use among adolescents attending school in Kerala, India. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35(5), 523–529. 10.1111/dar.12358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaisoorya T. S., Desai G., Nair B. S., Rani A., Menon P. G., Thennarasu K. (2019). Association of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms with academic and psychopathological outcomes in Indian college students: A retrospective survey. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 29(4), 124–128. 10.12809/eaap1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennum P., Hastrup L. H., Ibsen R., Kjellberg J., Simonsen E. (2020). Welfare consequences for people diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A matched nationwide study in Denmark. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 37, 29–38. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow J. B., Hall E., Koenen K. C., Dodge K. A., Amaya-Jackson L. (2008). Dissociation predicts later attention problems in sexually abused children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(2), 261–275. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss M. P., Gidycz C. A., Wisniewski N. (1987). The scope of rape: incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimizationin a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 55(2), 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosson D. S., Kelly J. C., White J. W. (1997). Psychopathy-related traits predict self-reported sexual aggression among college men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12, 241–254. 10.1177/088626097012002006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin R., Hébert M, Cossette L. (2015). Emotion regulation as a mediator of the relation between sexual abuse and behavior problems in preschoolers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 46, 16–26. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Candelas C., Corbeil T., Wall M., Posner J., Bird H., Fisher P. W., Suglia S. F., Duarte C. S. (2020). ADHD and risk for subsequent adverse childhood experiences: Understanding the cycle of adversity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 10.1111/jcpp.13352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mao A. R., Findling R. L. (2014). Comorbidities in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A practical guide to diagnosis in primary care. Postgraduate Medicine, 126(5), 42–51. 10.3810/pgm.2014.09.2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T., Imamura F. (2007). Association between childhood attention-deficit–hyperactivity symptoms and adulthood dissociation in male inmates: Preliminary report. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 61(4), 444–446. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01683.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K. A., Sheridan M. A., Winter W., Fox N. A., Zeanah C. H., Nelson C. A. (2014). Widespread reductions in cortical thickness following severe early-life deprivation: A neurodevelopmental pathway to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 76, 629–638. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeer S. V., Callaghan M., Henry D., Wallen J. (1994). Psychiatric disorders in sexually abused children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(3), 313–319. 10.1097/00004583-199403000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mii A. E., McCoy K., Coffey H. M., Meidlinger K., Sonnen E., Huit T. Z., Flood M. F., Hansen D. J. (2020). Attention problems and comorbid symptoms following child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 29(8), 924–943. 10.1080/10538712.2020.1841353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson G. V., Lichtenstein P., La°ngstroüm N, Pettersson E. (2018). Childhood neurodevelopmental disorders and risk of coercive sexual victimization in childhood and adolescence—A population-based prospective twin study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 59(9), 957–965. 10.1111/jcpp.12884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang L., Fang X., Mercy J., Perou R., Grosse S. D. (2008). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and child maltreatment: A population-based study. The Journal of Pediatrics, 153(6), 851–856. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210–210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbaran B., Erermis S., Bukusoglu N., Bildik T., Tamar M., Ercan E. S., Aydin C., Cetin S. K. (2009). Social and emotional outcomes of child sexual abuse: A clinical sample in turkey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(9), 1478–1493. 10.1177/0886260508323663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent N., Hébert M. (1995). Questionnaire sur la victimisation de l’enfant [Questionnaire on the victimization of the child]. French adaptation of History of Victimization Form by Wolfe, Gentile, & Boudreau (1987). Département de mesure et évaluation, Université Laval. [Google Scholar]

- Perfect M. M., Turley M. R., Carlson J. S., Yohanna J., Saint Gilles M. P. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. School Mental Health, 8(1), 7–43. 10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G. V., Willcutt E. G., Salum G. A., Kieling C., Rohde L. A. (2014). ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 434–442. 10.1093/ije/dyt261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucklidge J. J., Brown D. L., Crawford S., Kaplan B. J. (2006). Retrospective reports of childhood trauma in adults with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 9(4), 631–641. 10.1177/1087054705283892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman L. A., Mescher K. (2012). Of animals and objects: Men’s implicit dehumanization of women and likelihood of sexual aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 734–746. 10.1177/0146167212436401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero K. J., McLeer S. V., Dixon J. F. (2000). Sexual abuse characteristics associated with survivor psychopathology. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(7), 951–964. 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00144-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderud K., Murphy S., Elklit A. (2016). Child maltreatment and ADHD symptoms in a sample of young adults. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1). 10.3402/ejpt.v7.32061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayal K., Prasad V., Daley D., Ford T., Coghill D. (2018). ADHD in children and young people: Prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(2), 175–186. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30167-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnby K., Aslund C, Leppert J., Nilsson K. W. (2011). Symptoms of ADHD and depression in a large adolescent population: Co-occurring symptoms and associations to experiences of sexual abuse. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 65(5), 315–322. 10.3109/08039488.2010.545894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer A. E., Faraone S. V., Bogucki O. E., Pope A. L., Uchida M., Milad M. R., Spencer T. J., Woodworth K. Y., Biederman J. (2016). Examining the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(1), 72–83. 10.4088/JCP.14r09479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]