Abstract

The present study aimed to investigate the mediating role of state anxiety in the relationship between the fear of COVID-19 and relationship happiness among married individuals. An additional aim of the study also tested the moderating role of joint family activities between state anxiety and relationship happiness. The study sample consisted of 1713 married individuals (1031 women and 682 men). The study findings showed both the significant direct associations among the studied variables and the mediating role of state anxiety in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and relationship happiness. It also found that the path of state anxiety to relationship happiness among married individuals having family activities was significantly lower than those who did not. Directions for future research and application were discussed.

Keywords: fear of COVID-19, state anxiety, relationship happiness, married individuals

The coronavirus pandemic disease (COVID-19) broke out in December of 2019 in the city of Wuhan of Hubei Province, China, and has rapidly spread throughout the world. There have been confirmed cases in almost all countries across the world since the first appearance of the coronavirus (World Health Organization, 2020a). Additionally, WHO (2021) reported that 154.815.600 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 3.236.104 death in the Coronavirus dashboard on the 6th of May 2021. In Turkey, the first cases of COVID-19 appeared on 10 March and the number of confirmed cases has started to expeditiously increase. According to the Turkish Ministry of National Health (2020) reports, cases of COVID-19 reached 4.977.982 including 42.187 deaths as of May 6, 2021.

Governments and public health authorities have declared a state of emergency and taken many measurements such as the closure of schools and offices, closure of places where people gather, cancellation of mass events, travel restrictions, obligatory quarantine, and voluntary social isolation to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus (Ansari & Ahmadi Yousefabad, 2020). The Turkish government has also implied similar restrictions and urged citizens to keep themselves in voluntary quarantine and stay at home. Besides, mandatory quarantine is implemented during weekends in metropolitan provinces and cities with high rates of confirmed coronavirus cases (Ministry of the Interior, 2020).

Scientists worldwide have focused on the physical health and treatment process as the pandemic has a high rate of spread and fatality. Along with its negative effects on biological health, this pandemic, which has an unknown, uncertain, uncontrollable, and unpredictable nature, threatens the mental health of people (Sandín et al., 2020; Satici, Saricali, et al., 2020). Also, increasing mortality rate, impairment of daily routines, and being in quarantine for a long time affect the well-being of people (Lu et al., 2020; Satici, Saricali, et al., 2020; Zandifar & Badrfam, 2020). Some of these negative effects include fear, anxiety disorders, poor sleep quality, depression, psychological distress, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and suicide (Cao et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020; Haktanir et al., 2020; Huang & Zhao, 2020; Mamun & Griffiths, 2020; Satici, Gocet-Tekin, et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020).

Fear is an innate feeling and warning system of the body indicating the real or perceived threat. The function of fear is to prepare the body against encountered threats (Garcia, 2017). On the other hand, anxiety occurs when the threats encountered are unclear, and coping efforts fail (Öhman, 2008). State anxiety is a temporary emotional situation of the person, characterized by subjectively experienced feelings of worry, strain, apprehension, and activation of the autonomic nervous system (Julian, 2011). Extraordinary and uncontrollable conditions such as pandemics and disease outbreaks can trigger the transformation of people’s sense of fear into anxiety (Garcia, 2017; Mertens et al., 2020). Therefore, in the present study, it is expected that fear of COVID-19 predicts state anxiety.

One of the reasons that people experience anxiety during the pandemic is the quarantine process, stay-at-home, and social isolation policies imposed to curb the spread of the pandemic (Jacobson et al., 2020; Rosen et al., 2020). These measures taken in numerous countries have a devastating effect on relationships in general and in family affairs. Families reported losing freedom of movement and social environment as a reaction against quarantine measures. Other noticeable losses contain access to resources, income, and planned activities or celebrations (Luttik et al., 2020). Besides, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the balance between work and family connections and caused dramatically challenging results. With the closure of the schools and daycare centers, families began to be more responsible for childcare and even homeschooling. However, a great number of families also experience financial concerns due to working from home or the loss of jobs (Fisher et al., 2020). These issues have created a family environment where family members face aggression, addiction, domestic violence, or other forms of relational difficulties (Kaukinen, 2020; Lebow, 2020; Luttik et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020). According to the recent report published by the Center for Global Development, intimate partner violence indications have already increased in Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States because of home quarantines (Peterman et al., 2020). Other victims of this violence are children and adolescents who have been exposed to family violence and who are less possibly able to seek professional support (Clarke et al., 2020). Also, another negative result of the quarantine concerning family relations is the increase in divorce rates. For example, China pointed out that the rate of divorce increased during the quarantine period (Prasso, 2020). Recent research studies suggested that anxiety disorders (Zaider et al., 2010), stress (Neff & Karney, 2009), and depression (Fletcher et al., 1990) are negatively related to relationship quality in close relations. Thus, in this research, it is expected that state anxiety will negatively influence relationship happiness among married individuals.

Alternatively, some families have developed their close relations during the quarantine period. This period has also provided an opportunity for all family members to spend time together the whole day. The daily dialog can become an extraordinary advantage to rediscover the value of previously neglected family ties when sharing domestic space or engaging in household chores. The emotional bonds and relationships of families have enhanced due to sharing the same space in a house and fulfilling daily activities. Families maintain their daily routines and rituals together. As a result, the cumulative effects of these interpersonal processes lead the family to cope with quarantine together (Gritti, 2020). Kar et al. (2020) suggested that several lifestyle-related measures such as creative activities, relaxation exercises, indoor play, aerobic exercise, reading, online learning courses, music, yoga/meditation, installation of hope, prayer, and positive thinking could ease the constraints of the stress and help with coping the mental health challenges. Therefore, in this study, it is anticipated that joint family activities will reduce state anxiety, thereby increasing the relationship happiness among married individuals. Indeed, shared self-expanding activities provided an important contribution to maintaining and enhancing close romantic relationships and experienced marital quality (Aron et al., 2001; Aron et al., 2002).

The Current Study

People around the world are worried about the COVID-19 pandemic disaster and its long-term outcomes (Kumar & Nayar, 2020). The WHO similarly pointed out its concern about the mental and psycho-social effects of the pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020c). Pandemic has led to major changes in people’s lives. Additionally, the strict measures to control and manage the epidemiological emergency have indisputably exposed the structure of families to some serious issues and strains, and how long it will take is unknown (Mazza et al., 2020). Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the mediating role of state anxiety in the relationship between the fear of COVID-19 and relationship happiness among married individuals. The second aim was to investigate the moderating role of joint family activities between state anxiety and the relationship happiness among married individuals. Determining the framework of relationships between these variables is important in terms of empirically examining the role of the coping mechanism used in the process of pandemic and quarantine periods. The results of this research will thus provide significant implications and guidelines for existing and upcoming approaches to prevention and intervention.

In line with these explanations and based on previous research results in the literature, the current study suggests the following hypotheses:

H1. There are significant associations among the studied variables.

H2. State anxiety mediates the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and relationship happiness among married individuals.

H3. The negative effect of state anxiety among married individuals having family activities is significantly lower than those who do not.

Method

Participants

The current research was carried out utilizing a web-based cross-sectional mediation design. We used the snowball sampling strategy to reach more participants in this research and we requested participants to share this research form with their contacts. The data of the research were collected between May 23 and June 6, 2020. First, this research consists of 1855 married individuals from 67 different provinces of Turkey. To achieve better accuracy, 142 participants were removed from the data because of some reasons (e.g., not living with their spouses or not having their spouses). Therefore, the research was completed with 1713 married individuals. 682 men (39.8%) and 1031 women (60.2%) were included in the research. 294 participants (17.2%) were between 21 and 29 years, 678 participants (39.6%) were between 30 and 39 years, 491 participants (28.7%) were between 40 and 49 years, 218 participants were between 50 and 59 years (12.7%), and 32 participants (1.9%) were over 60 years. Moreover, the average age of the participants was 38.69 (SD = 9.13, range = 21–75 years). Considering how many years the participants are married, 484 (14.5%) of individuals have been married for 0–5 years, 288 people (16.8%) have been married for 6–10 years, 286 people (16.7%) have been married for 11–15 years, 260 people (15.2%) have been married for 16–20 years, and 395 people (23.1%) have been married for over 21 years. When the socioeconomic level of the participants was classified as low income between 0 and 2500Ł, medium-income between 2501 and 6500Ł, and high income from 6501Ł and above; 148 (8.6%) low-income people, 971 (56.6%) middle-income people, and 594 (34.7%) high-income people were included in the research. On the other hand, we observed that 1385 (80.9%) of the participants had activities with their families during the epidemic period despite 328 (19.1%) did not have. Finally, four people (0.2%) of participants do not graduate from any school level, 52 people (3%) have primary school graduates, 50 people (2.9%) have secondary school graduates, 102 people (6%) have high school degrees, 132 people (7.7%) have associate degrees, 981 people (57.3%) have bachelor’s degrees, and 392 people (22.9%) have master’s degrees.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

It is a form prepared by researchers to find out the participants’ gender, age, education level, socioeconomic level, and marriage years, whether they are active in the coronavirus epidemic period.

The Fear of COVID-19 Scale

The Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) is developed by Ahorsu et al. (2020) and adapted to Turkish by Haktanir et al. (2020). The FCV-19S consists of seven items and each item had five response options. Example item: “When I think of being a coronavirus, my heart rate is accelerating or palpitations.” The factor loads of the FCV-19S items vary between 0.50 and 0.081. In addition, Cronbach’s value of the Turkish form of the FCV-19S was found to be 0.86.

Relationship Happiness Questionnaire

The Relationship Happiness Questionnaire (RHQ) was developed by Fletcher et al. (1990) and includes the evaluation of close relationships. Tutarel-Kışlak (2002) adapted to Turkish and the RHQ consists of six items and each item gets a value between 1 and 7. Example item: “How much do you love your partner.” Cronbach’s value of the Turkish form of the RHQ is .80, and the test–retest reliability value is .86 (p < 0.01). When the reliability of the RHQ was examined with the split-half method, the reliability coefficient was found to be r = .80. Moreover, Marriage Adjustment Scale (MAS) was used to examine the criterion-dependent validity of the RHQ, and the correlation coefficient between the total scores of these two scales is .69 (p < .01).

State Anxiety Inventory

The State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) was developed by Spielberger (1970) and Le compte & Oner (1976) adapted to Turkish (see Eryüksel, 1987). The SAI consists of 20 items and each item has a four-point Likert-type rating system. Example item: “I am nervous right now.” Cronbach’s value of the Turkish form of the SAI was found between 0.94 and 0.96. Also, the test-retest reliability coefficient of the SAI was found between 0.68 and 0.26.

Procedures

Expedited ethics approval was obtained from the Social and Human Sciences Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Necmettin Erbakan University. First, the scales and demographic information form used in the research were converted into a single form in Google Forms and then shared by e-mail, social media (Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn), and other online spreading data platforms to reach married individuals. We requested to complete the items in the form completely from participants.

Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using AMOS 20.0 to test the research model. The item parceling method was used to control possible inflated measurement errors caused by multiple items for latent variables (Bandalos, 2008). The goodness of fit of the structural equation model was evaluated within the values of chi-square/df ratio (x2/df) ≤ 5.0 = acceptable model fit; comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness of fit indicator (GFI), normative fitness index (NFI), and incremental fit index (IFI) ≥ .90 = acceptable model fit; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤.08 acceptable model fit (Anderson & Gerbing, 1984; Kline, 2005). To test the indirect role of state anxiety in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and relationship happiness, the bootstrapping mediation method was used with 5000 re-samples and bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (MacKinnon et al., 2002). Also, the multigroup comparison analysis in AMOS was conducted to determine whether the path of state anxiety on relationship happiness was statistically different between married individuals having family activities and those who did not.

Results

Descriptive statistics concerning the variables of the study were presented in Table 1. The finding of Pearson correlations demonstrated that fear of COVID-19 was positively associated with state anxiety (r = .40, p < .001) and negatively associated with relationship happiness (r = −.06, p < .05). Also, it was seen that state anxiety was negatively associated with relationship happiness (r = −.32, p <.001). Individuals participating in family activities have a lower state anxiety level (t = −6.598, p < .01) and a higher relationship happiness level (t = 4.720, p < .01) than those did not.

Table 1.

M, SD, K, S, and correlations of all variables.

| Variable | M | SD | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Fear of COVID-19 | 15.24 | 6.39 | — | — | — |

| State anxiety | 36.45 | 11.18 | .40*** | — | — |

| Relationship happiness | 34.69 | 6.91 | −.06* | −.32*** | — |

N = 1827; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; r = correlation coefficient. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

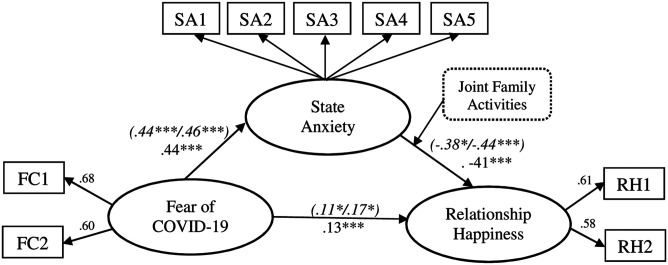

The structural model also provided acceptable fit indexes (χ2/sd = 4.59, p < .001, CFI = .99, GFI = .99, NFI = .99, IFI = .99, RMSEA = .046). The structural model related to the analysis was presented in Figure 1. First, fear of COVID-19 negatively predicted relationship happiness (β = −.06, p < .01). After state anxiety was included in the model as mediating variable, the negative predictor role of fear of COVID-19 in relationship happiness reversed to be positive (β = .13, p < .01). Moreover, fear of COVID positively predicted state anxiety (β = .44, p < .01), and state anxiety negatively predicted relationship happiness (β = −.41, p < .01). According to this result, we see that state anxiety has a fully mediating role in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and relationship happiness. The multigroup unconstrained model comparison of the study was significant (p < .01). The outcomes of the analysis supported the model fit (χ2/sd= 3.11, p < .001, CFI = .99, GFI = .98, NFI = .99, IFI = .99, RMSEA = .035, p< .01). The negative effect of state anxiety among married individuals having family activities was significantly lower than those who did not.

Figure 1.

Mediating model of state anxiety in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and relationship happiness. Note: The factor loadings were standardized (The italic values in the parentheses are for individuals having family activities and those are not, respectively). *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Discussion

In this study, the relationships between COVID-19 fear levels, state anxiety levels, and happiness levels in relationships of married individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic was examined. Findings indicated that the level of situational anxiety of individuals played a mediating role in the relationship between individuals who fear COVID-19 and their level of happiness. Our results are consistent with other studies in the literature (Dvorsky et al., 2020; Liu & Doan, 2020; Ones, 2020; Prime et al., 2020). No study has been found in the literature to explain the mediating role of state anxiety in the relationship between the levels of happiness in the relationship and COVID-19 fear levels of married individuals. Therefore, this study is important to explain the impact of COVID-19 fear on relationships of married individuals.

Our results are consistent with the results obtained and previous research with our H1 hypothesis. The fear levels of COVID-19 for married people have a negative influence on their happiness levels in their relationships, and state anxiety levels of individuals have been found to play an effective role in their relationships between their fear of COVID-19 and their happiness levels. (Balzarini et al., 2020; Coop Gordon & Mitchell, 2020; Pietromonaco & Overall, 2021; Russell et al., 2020). People with low levels of COVID-19 fear and anxiety are shown to have high levels of satisfaction in their relationships. (Stanley & Markman, 2020). The rise in COVID-19 fears of married people increases depressed mood, sleep disorders, and anxiety, while it has been observed that people’s support for each other decreases and the level of happiness in people’s relationships decreases accordingly (Brown et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Moreira & da Costa, 2020). Lebow (2020) concludes that divorces increase as people’s fear of COVID-19 raises their levels of anxiety. In some studies, it is also found that bad family relationships increase anxiety and fear of COVID-19 (Biddle et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2020).

Consistent with the results of our research with the H2 hypothesis, state anxiety has a mediator role between fear of COVID and relationship happiness. When the literature is examined, there is no difference in terms of anxiety in individuals who do and do not perform activities during the epidemic process. (Biddle et al., 2020; Elder et al., 2020). However, in some studies, it has been found that married individuals can reduce their anxiety levels by doing activities together (e.g., walking, exercising, and watching movies) and supporting each other sincerely during the epidemic process (Brock & Laifer, 2020; Dobson, 2020; Maiti et al., 2020).

Our H3 hypothesis is consistent with the results of our research. When previous studies are examined, it has been observed that psychological distress (e.g., anxiety and fear) decreases and the level of happiness in relationships increases as individuals’ joint activities (e.g., eating, exercising, and sharing household chores) increase (Günther‐Bel et al., 2020; Mikocka-Walus et al., 2021;Stanley & Markman, 2020; Behar-Zusman et al. 2020). Due to the fact that married individuals spend more time with each other during the quarantine process and get away from negative factors from the outside world, their anxiety levels decrease and their relationship satisfaction is high (Overall et al., 2021; Pietromonaco & Overall, 2021). Similarly, family therapists found that their anxiety levels decreased as married couples increased their activities together, and the level of satisfaction in their relationships increased during the epidemic (Lee, 2020; Sahebi, 2020). For example, a study found digital socializing and day-level physical activity at home during the Covid-19 pandemic significantly decreased daily negative affect and were positively linked with Turkish individuals’ happiness (Cetin & Kokalan, 2021).

Limitations

Besides these remarkable results, the research has some limitations. The study is a cross-sectional study and it is far from examining the course of relationships within the family during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the data are collected with self-report scales, it is based on the participants' own opinions. The chronic illness of the participants may affect their fear and anxiety levels. However, this variable was not added to the model in the study. Besides, many variables affect the happiness of the marital relationship, as well as the fear and anxiety of COVID-19. This research only examined the effects of COVID-19 fear, state anxiety, and joint family activities. It is also can be considered as a limitation that research conducted with only participants from Turkey. Because one of the factors affecting the change in family relations experienced during the pandemic period may be the perspective of societies toward the family.

Recommendations and Implications

Considering the results and limitations of the study, we can list the implications and recommendations as follows: Qualitative and longitudinal studies can be conducted to better understand the structure of family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. Motivating family members to actively join family activities represents a promising objective to mitigate the negative effect of state anxiety, which fear of coronavirus reveals, on married individuals’ relationship happiness. As the use of technology and social media increases during the COVID-19 pandemic and family activities decrease, governments can implement policies that encourage family activities. Mental health professionals can also encourage family activities by limiting families’ use of technology to support families to cope with anxiety and increase marital happiness.

Conclusion

Research results confirmed the hypotheses suggested by the researchers. State anxiety had a mediating role in the relationship between coronavirus fear and relationship happiness among married individuals. In the model, the mediating role of state anxiety was valid for both those who did joint activities with the family and those who did not. The negative effect of state anxiety on relationship happiness among married individuals was significantly lower in those who did activities with their family during the pandemic process and those who did not.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Ali Karababa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0458-3437

Zeynep Şimşir https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2353-8922

References

- Ahorsu D. K., Lin C., Imani V., Saffari M., Griffiths M. D., Pakpour A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. C., Gerbing D. W. (1984). The effect of sampling error on convergence, improper solutions, and goodness-of-fit indices for maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis. Psychometrika, 49(2), 155-173. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari M., Ahmadi Yousefabad S. (2020). Potential threats of COVID-19 on quarantined families. Public Health, 183, 1-1. 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A., Norman C. C., Aron E. N. (2001). Shared self-expanding activities as a means of maintaining and enhancing close romantic relationships. In Harvey J., Wenzel A. (Eds.), Close romantic relationships (pp. 55-74). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Aron A., Norman C. C., Aron E. N., Lewandowski G. (2002). Shared participation in self-expanding activities: Positive effects on experienced marital quality. In Noller P., Feeney J. A. (Eds.), Understanding marriage: Developments in the study of couple interaction (pp. 177-194). New York, NY: Cambrige University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini R. N., Muise A., Zoppolat G., Di Bartolomeo A., Rodrigues D. L., Alonso-Ferres M., Slatcher R. B. (2020). Love in the time of covid: Perceived partner responsiveness buffers people from lower relationship quality associated with covid-related stressors. Retreived fromhttps://psyarxiv.com/e3fh4

- Bandalos D. L. (2008). Is parceling really necessary? A comparison of results from item parceling and categorical variable methodology. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 15(2), 211-240. 10.1080/10705510801922340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behar‐Zusman V., Chavez J. V., Gattamorta K. (2020). Developing a measure of the impact of COVID‐19 social distancing on household conflict and cohesion. Family Process, 59(3), 1045-1059. 10.1111/famp.12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle N., Edwards B., Gray M., Sollis K. (2020). Mental health and relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, 1-28. [Google Scholar]

- Brock R. L., Laifer L. M. (2020). Family Science in the Context of the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Solutions and New Directions. Family Process, 59(3), 1007-1017. 10.1111/famp.12582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. M., Doom J. R., Lechuga-Peña S., Watamura S. E., Koppels T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104699. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Fang Z., Hou G., Han M., Xu X., Dong J., Zheng J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetin M., Kokalan O. (2021). A multilevel analysis of the effects of indoor activities on psychological wellbeing during COVID-19 pandemic. Anales De Psicologia, 37(3), 500-507. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A., Olive P., Akooji N., Whittaker K. (2020). Violence exposure and young people's vulnerability, mental and physical health. International Journal of Public Health, 65, 357-366. 10.1007/s00038-020-01340-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop Gordon K., Mitchell E. A. (2020). Infidelity in the Time of COVID‐19. Family Process, 59(3), 956-966. 10.1111/famp.12576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson K. S. (2020). Coping with Covid 19: The challenges ahead. World Confederation of Cognitive and Behavioural Therapies, 1-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z., Q., Ma J., Hao Y., N., Shen X., L., Liu F., Gao Y., Zhang L. (2020). The social psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical staff in China: A cross-sectional study. European Psychiatry : The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 63(1), e65-e68. 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorsky M. R., Breaux R., Becker S. P. (2020). Finding ordinary magic in extraordinary times: child and adolescent resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1007/s00787-020-01583-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G., J., Alfonso-Miller P., Atkinson C., M., Santhi N., Ellis J., G. (2020). Testing an early online intervention for the treatment of disturbed sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sleep COVID-19): Structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials Electronic Resource, 21(1), 704-713. 10.1186/s13063-020-04644-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eryüksel G., N. (1987). Ergenlerde kimlik statülerinin incelenmesine ilişkin kesitsel bir çalışma ([A cross-sectional study on the examination of identity status in adolescents] Master dissertation). Ankara: Hacettepe University. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J., Languilaire J.-C., Lawthom R., Nieuwenhuis R., Petts R. J., Runswick-Cole K., Yerkes M. A. (2020). Community, work, and family in times of COVID-19. Community, Work & Family, 23(3), 247-252. 10.1080/13668803.2020.1756568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher G. J. O., Fitness J., Blampied N. M. (1990). The link between attributions and happiness in close relationships: The roles of depression and explanatory style. Journal of Submicroscopic Cytology and Pathology, 9(2), 243-255. [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Zheng P., Jia Y., Chen H., Mao Y., Chen S., Wang Y., Fu H., Dai J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. Plos One, 15(4), e0231924. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia R. (2017). Neurobiology of fear and specific phobias. Learning & Memory, 24(9), 462-471. 10.1101/lm.044115.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti P. (2020). Family systems in the era of Covid-19: From openness to quarantine. Journal of Psychosocial Systems, 4(1), 1-5. 10.23823/jps.v4i1.64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Günther‐Bel C., Vilaregut A., Carratala E., Torras‐Garat S., Pérez‐Testor C. (2020). A mixed‐method study of individual, couple, and parental functioning during the state‐regulated COVID‐19 lockdown in Spain. Family Process, 59(3), 1060-1079. 10.1111/famp.12585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Cheng C., Zeng Y., Li Y., Zhu M., Yang W., Li X. (2020). Mental health disorders and associated risk factors in quarantined adults during the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e20328. 10.2196/20328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haktanir H., Seki T., Dilmaç B. (2020). Adaptation and evaluation of Turkish version of the fear of COVID-19 Scale (1-9). Advance online publication. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1773026.Death Studies [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Zhao N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112954. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N. C., Lekkas D., Price G., Heinz M. V., Song M., O’Malley A. J., Barr P. J. (2020). Flattening the Mental Health Curve: COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Orders Are Associated With Alterations in Mental Health Search Behavior in the United States. JMIR Mental Health, 7(6), e19347. 10.2196/19347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian LJ. (2011). Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care & Research, 63(Supp 11), S467-S472. 10.1002/acr.20561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar S. K., Yasir Arafat S. M., Kabir R., Sharma P., Saxena S. K. (2020). Coping with mental health challenges during COVID-19, Medical Virology: From Pathogenesis to Disease Control. In Saxena S. K. (Ed.), In coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (pp. 199-213). Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kaukinen C. (2020). When stay-at-home orders leave victims unsafe at home: Exploring the risk and consequences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice: AJCJ, 45(4), 668-669. 10.1007/s12103-020-09533-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. B. (2005). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (3th ed.). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Nayar KR. (2020). COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 180(6), 1-2. 10.1080/09638237.2020.1757052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le compte W., A., Oner N. (1976). Development of the Turkish edition of the State-trait anxiety inventory. Cross-Cultural Anxiety, 1, 51-67. [Google Scholar]

- Lebow J. L. (2020). Family in the Age of COVID‐19. Family Process, 59(2), 309-312. 10.1111/famp.12543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. Y. (2020). The Musings of a Family Therapist in Asia When COVID‐19 Struck. Family Process, 59(3), 1018-1023. 10.1111/famp.12577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Doan SN. (2020). Psychosocial stress contagion in children and families during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clinical Pediatrics, 59(9-10), 853-855. 10.1177/0009922820927044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W., Yuan L., Xu J., Xue F., Zhao B., Webster C. (2020). The psychological effects of quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: Sentiment analysis of social media data. Retrieved from 10.1101/2020.06.25.20140426. [DOI]

- Luttik M., A., Mahrer-Imhof R., Garcia-Vivar C., Brodsgaard A., Dieperink K., B., Imhof L., Konradsen H. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: A family affair. (2020). Journal of Family Nursing, 26(2), 87-89. 10.1177/1074840720920883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M., Hoffman J. M., West S. G., Sheets V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83-104. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti T., Singh S., Innamuri R., Hasija A. D. (2020). Marital distress during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: A brief narrative. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 8(2), 426-433. 10.25215/0802.257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun M. A., Griffiths M. D. (2020). First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102073. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza M., Marano G., Lai C., Janiri L., Sani G. (2020). Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113046. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens G., Gerritsen L., Duijndam S., Salemink E., Engelhard I. M. (2020). Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102258. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikocka-Walus A., Stokes M. A., Evans S., Olive L., Westrupp E. (2021). Finding the power within and without: How can we strengthen resilience against symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression in Australian parents during the COVID-19 pandemic? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 145, 4441113–1128.. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Interior (2020). Curfew restrictions to be applied in 31 provinces between 30.04.2020-03.052020. Retrieved from https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/31-ilde-30042020-03052020-tarihlerinde-uygulanacak-sokaga-cikma-kisitlamasi

- Moreira D. N., da Costa M. P. (2020). The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the precipitation of intimate partner violence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 71, 101606-6. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff L. A., Karney B. R. (2009). Stress and reactivity to daily relationship experiences: How stress hinders adaptive processes in marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(3), 435-450. 10.1037/a0015663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A. (2008). Fear and anxiety: Overlaps and dissociations. In Lewis M., Haviland-Jones J. M., Barrett L. F. (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 709-728). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ones L. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: A family affair. Journal of Family Nursing, 26(2), 87-89. 10.1177/1074840720920883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall N. C., Chang V. T., Pietromonaco P. R., Low S. T., Henderson A. M. E. (2021). Partners’ attachment in security and stress predict poorer relationship functioning during COVID-19 quarantine. Social Psychological and Personality Science, . 10.1177/1948550621992973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman A., Potts A., O’Donnell M., Thompson K., Shah N., Oertelt-Prigione S., Van Gelder N. (2020). Pandemics and violence against women and children. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco P. R., Overall N. C. (2021). Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. American Psychologist, 76(3), 438-450. 10.1037/amp0000714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasso S. (2020). China’s divorce spike is a warning to rest of locked-down world. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved fromhttps://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-31/divorces-spike-in-china-after-coronavirus-quarantines.

- Prime H., Wade M., Browne D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631-643. 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen Z., Weinberger-Litman S. L., Rosenzweig C., Rosmarin D. H., Muennig P., Carmody E. R., Rao S. T., Litman L. (2020). Anxiety and distress among the first community quarantined in the U.S due to COVID-19: Psychological implications for the unfolding crisis. Retrieved from 10.31234/osf.io/7eq8c. [DOI]

- Russell B. S., Hutchison M., Tambling R., Tomkunas A. J., Horton A. L. (2020). Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: Caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent-child relationship. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 51, 671-682. 10.1007/s10578-020-01037-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahebi B. (2020). Clinical Supervision of Couple and Family Therapy during COVID‐19. Family Process, 59(3), 989-996. 10.1111/famp.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandín B., Valiente R. M., García-Escalera J., Campagne D. M., Chorot P. (2020). Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: Negative and positive effects in Spanish population during the mandatory national quarantine. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 25(1), 1-21. http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/rppc. [Google Scholar]

- Satici B., Gocet-Tekin E., Deniz M. E., Satici S. A. (2020). Adaptation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satici B., Saricali M., Satici S. A., Griffiths M. D. (2020). Intolerance of uncertainty and mental wellbeing: serial mediation by rumination and fear of COVID-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00305-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. (1970). The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley S. M., Markman H. J. (2020). Helping Couples in the Shadow of COVID‐19. Family Process, 59(3), 937-955. 10.1111/famp.12575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Sun Z., Wu L., Zhu Z., Zhang F., Shang Z., Jia Y., Gu J., Zhou Y., Wang Y., Liu N., Liu W. (2020). Prevalence and risk factors of acute posttraumatic stress symptoms during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. MedRxiv. 10.1101/2020.03.06.20032425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Ministry of National Health (2020). Current situation in Turkey. Retrieved fromhttps://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/.

- Tutarel-Kışlak Ş. (2002). İlişkilerde Mutluluk Ölçeği (İMÖ): Güvenirlik ve geçerlik çalışması [Relationship Happiness Questionnaire (RHQ): Reliability and validity in Turkish Sample]. Kriz Dergisi [Journal of Crisis], 10(1), 37-43. 10.1501/Kriz_0000000174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020a). Numbers at a glance. Retrieved fromhttps://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- World Health Organization (2020c). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Retrieved fromhttps://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf.

- Zaider T. I., Heimberg R. G., Iida M. (2010). Anxiety disorders and intimate relationships: A study of daily processes in couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(1), 163-173. 10.1037/a0018473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandifar A., Badrfam R. (2020). Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 101990. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]