Abstract

To understand the role of NF-κB in the development of murine tuberculosis in vivo, NF-κB p50 knockout mice were infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis by placing them in the exposure chamber of an airborne-infection apparatus. These mice developed multifocal necrotic pulmonary lesions or lobar pneumonia. Compared with the levels in wild-type mice, pulmonary inducible nitric oxide synthase, interleukin-2 (IL-2), gamma interferon, and tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels were significantly low but expression of IL-10 and transforming growth factor β mRNAs were within the normal ranges. The pulmonary IL-6 mRNA expression level was higher. Therefore, NF-κB and its interaction with host cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis.

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is a ubiquitous dimeric transcription factor whose activity is tightly regulated by various cytokines and other external stimuli (1, 31). It is retained in the cytoplasm in latent form as a heterotrimeric complex consisting of p50, p65 subunits, and an inhibitor, IκB. The genes regulated by this transcription factor encode proteins involved in rapid response to pathogens or stress, including the acute-phase proteins, cytokines, and cellular adhesion molecules (1, 10).

The nature of the signals that lead to activation of NF-κB strongly implies that NF-κB plays a major role in the immune system (for a review, see reference 10). NF-κB plays a role in the activation of immune cells by upregulating the expression of many cytokines essential to the immune responses (1, 10). Anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit NK-κB activation in cultured cells, indicating that NF-κB may be a good target for potential therapy of chronic inflammatory diseases. NK-κB is also involved in mycobacterial infection, according to research carried out in vitro at the cellular level (4, 30). Expression of interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor and activation of IL-6 and IL-8 by Mycobacterium tuberculosis are mediated by NF-κB (30, 33, 35). Lipoarabinomannan from M. tuberculosis stimulates the activation of NF-κB and KBFI in murine macrophages (3, 4). Moreover, a purified protein derivative induces the activation of NF-κB in monocytes from patients with tuberculosis (31). On the other hand, M. avium-intracellulare complex activates NF-κB in different cell types through reactive oxygen intermediates (11).

However, little is known about the role of NF-κB in mycobacterial infection in vivo. The present study was undertaken to determine the role of the p50 subunit of NF-κB in murine tuberculosis in vivo. We demonstrate that NF-κB p50 plays a major role in mycobacterial infection by augmenting the expression of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-2, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Six-week-old C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice were purchased from Japan SLC Co. Ltd. (Shizuoka, Japan). NF-κB KO mice of C57BL/6 origin whose exon 6 of the Nfkb1 gene had been disrupted by insertion of a vector containing the neo resistance gene were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) (22). The mice lacking the p50 subunit of NF-κB showed no developmental abnormalities. Mice lacking the p65 subunit of NF-κB die on day 16 of gestation (10). All mice were housed in a biosafety level 3 facility and given mouse chow and water ad libitum after aerosol infection with mycobacteria.

Experimental infections.

The virulent Kurono strain of M. tuberculosis (ATCC 358121) was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth for 2 weeks and then filtered with a sterile acrodisc syringe filter (Pall Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.) with a pore size of 5.0 μm. Aliquots of the filtrate bacterial solution were stored in a freezer at −80°C until use. The mice were infected by being placed into the exposure chamber of an aerosol generator (Glas-Col, Inc., Terre Haute, Ind.) in which the nebulizer compartment was filled with 5 ml of a suspension containing 106 CFU of Kurono tubercle bacilli under conditions that would introduce about 1,000 bacteria into the lungs of each animal (26, 34).

CFU assay.

At 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 weeks after aerosol infection, groups of mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium, the abdominal cavities were incised, and exsanguination was carried out by splenectomy and transection of the left renal artery and vein. The lungs, spleens, and livers were excised and weighed. The right upper lobes of the lungs and some spleen tissues were weighed separately and used to evaluate the in vivo growth of M. tuberculosis. The lung and spleen tissue samples were each homogenized with a mortar and pestle and then placed in test tubes, and 1 ml of sterile saline was added to each sample. After homogenization, 100 μl of the homogenate was plated in 10-fold serial dilution on 1% Ogawa slant media. Colonies on the media were counted after a 4-week incubation at 37°C.

RT-PCR.

The right lobes of the lungs and the spleen tissues were used for reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis to examine several cytokine mRNA expression levels in these samples during M. tuberculosis infection. These tissue samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −85°C until use. RNA extraction was performed as described previously (25, 26). Briefly, the frozen tissues were homogenized in a microcentrifuge tube. Then the homogenates were treated with total RNA isolation reagent, TRIzol reagent (GIBCO BRL), as specified by the manufacturer. After RNA isolation, total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (GIBCO BRL) following measurement of total RNA concentration, and agarose gel electrophoresis was performed.

PCR was performed with gene-specific primer sets for β-actin, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, transforming growth factor β, (TGF-β), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) genes. For β-actin, samples were subjected to 23 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min), annealing (65°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 2 min); for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12p40, and INOS, they were subjected to 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min), annealing (65°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 2 min); for IL-2 and IL-6, they were subjected to 40 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min), annealing (62°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 2 min); for IL-10, they were subjected to 40 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min) annealing (65°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 2 min); and for TGF-β they were subjected to 25 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min), annealing (60°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 2 min).

The primer sequences and PCR product sizes were as follows: for β-actin, 5′-TGT GAT GGT GGG AAT GGG TCA G-3′ (sense) and 5′-TTT GAT GTC ACG CAC GAT TTC C-3′ (antisense), 514 bp; for IFN-γ, 5′-TAC TGC CAC GGC ACA GTC ATT GAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCA GCG ACT CCT TTT CCG CTT CCT-3′ (antisense), 405 bp; for TNF-α, 5′-ATG AGC ACA GAA AGC ATG ATC-3′ (sense) and 5′-TAC AGG CTT GTC ACT CGA ATT-3′ (antisense), 276 bp; for IL-1β, 5′-CAG GAT GAG GAC ATG AGC ACC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTC TGC AGA CTC AAA CTC CAC-3′ (antisense), 447 bp; for IL-2, 5′-CTT CAA GCT CCA CTT CAA GCT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCA TCT CCT CAG AAA GTC CAC-3′ (antisense), 400 bp; for IL-6, 5′-CAT CCA GTT GCC TTC TTG GGA-3′ (sense) and 3′-CAT TGG GAA ATT GGG GTA GGA AG-3′ (antisense), 463 bp; for IL-10, 5′-CCA GTT TTA CCT GGT AGA AGT GAT-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGT CTA GGT CCT GGA GTC CAG CAG-3′ (antisense), 324 bp; for IL-12p40, 5′-ATC TCC TGG TTT GCC ATC GTT TTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCC CTT TGG TCC AGT GTG ACC TTC-3′ (antisense), 527 bp; for TGF-β, 5′-CGG GGC GAC CTG GGC ACC ATC CAT GAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTG CTC CAC CTT GGG CTT GCG ACC CAC-3′ (antisense), 371 bp; and for iNOS, 5′-TGG GAA TGG AGA CTG TCC CAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGG ATC TGA ATG TGA TGT TTG-3′ (antisense), 306 bp.

Amplification was carried out with a thermal cycler (model 480, Perkin-Elmer Cetus). A 10-μl volume of each PCR product was used for electrophoresis in a 4% agarose–NuSieve GTG (1:3) gel and visualized using ethidium bromide staining.

Light and electron microscopy.

For light microscopy, the left lobes of the lungs were excised and fixed with 20% formalin-buffered methanol solution, Mildform 20NM (containing 8% formaldehyde and 20% methanol) (Wako Pure Chemical Co., Osaka, Japan), dehydrated with a graded ethanol series, treated with xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Sections 5 μm thick were cut from each paraffin block and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or Ziehl-Neelsen stain for acid-fast bacilli.

For electron microscopy, the right upper lobe of the lung was fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) (PB) at 4°C overnight, washed three times with cold PB, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in PB at 4°C for 1 h, dehydrated with a graded acetone series, and finally embedded with Spurr's low-viscosity resin. Ultrathin sections were obtained using a Reichert Ultracut microtome and stained with uranyl acetate and Sato's lead solution. The stained ultrathin sections were examined using a 1200EX electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical methods.

The values were compared by Student's t test. For all statistical analyses, differences at P < 0.01 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Mycobacterial burden in the lungs and spleens of NF-κB KO mice.

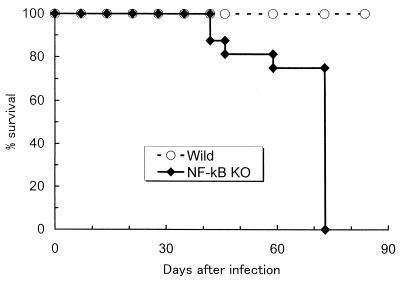

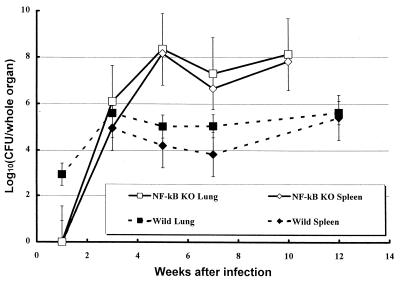

NF-κB is a transcription factor that plays an important role in the expression of many immunological mediators, including cytokines, their receptors, and components of their signal transductions. To clarify the role of NF-κB in experimental tuberculosis, C57BL/6 WT mice and mice lacking the p50 subunit of NF-κB (Nfkb1 gene disrupted) (NF-κB KO mice) were infected with the virulent Kurono strain of M. tuberculosis using an aerosol infection apparatus (26, 28). C57BL/6 WT mice survived the entire 12-week experimental period, but NF-κB KO mice began to succumb to the disease at 6 weeks after infection, and all mice had died by 10 weeks after infection (Fig. 1). The numbers of recovered tubercle bacilli from the lungs and spleen tissue of infected animals after aerosol infection are shown as CFU in Fig. 2. At 1 week after infection, tubercle bacilli were recovered only from the lung tissues of C57BL/6 WT mice. However, by 3 weeks after infection, the mycobacterial load in the organs had increased in NF-κB KO mice. Both the WT and KO groups showed similar patterns of bacterial growth in the lungs and spleen. Surprisingly, at 5 weeks after infection, NF-κB KO mice contained 2,500-fold more tubercle bacilli in the lungs and 1,000-fold more tubercle bacilli in the spleen tissues than the WT mice did. Furthermore, this high bacterial load continued up to 10 weeks after infection, although a slight decrease in CFU was observed at 7 weeks. On the other hand, in WT mice, the CFU in both the lung and spleen tissues reached a peak at 3 weeks after infection and there was no major change in the number of CFU after 5 weeks.

FIG. 1.

Survival curves of mice infected with M. tuberculosis Kurono strain. The data presented are from two separate experiments with 10 mice in each group.

FIG. 2.

CFU in lung and spleen tissues of NF-κB KO and WT mice (10 mice each) exposed to 106 CFU of M. tuberculosis Kurono strain by the airborne route. At the indicated days after infection, three mice from each group were sacrificed and homogenates of lung and spleen tissues were plated. Error bars indicate standard deviations of the means.

Light and electron microscopic observation of infected lungs.

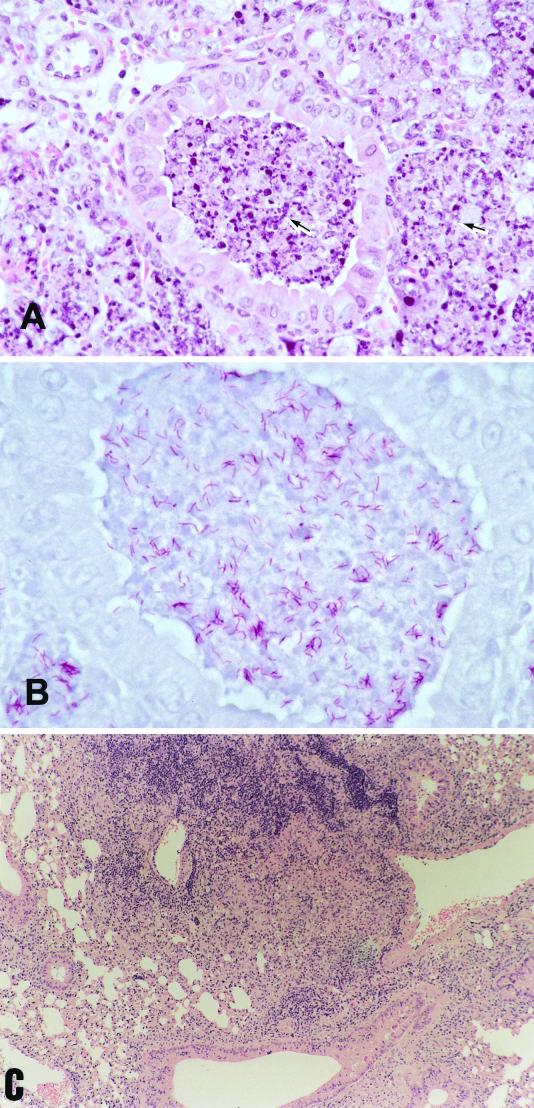

In accordance with the CFU changes, histopathological findings obtained from C57BL/6 WT and NF-κB KO mice showed similar changes at 3 weeks after infection, but at 5 weeks, NF-κB KO mice showed extremely severe pathological changes, especially in the infected lung tissues (Fig. 3). Pulmonary histopathology in the NF-κB KO mice at 5 weeks after infection revealed findings characterictic of lobar pneumonia, which was induced by the tubercle bacilli. In the pulmonary lesions, there was severe inflammation in which numerous macrophages ingesting many mycobacteria filled up the alveolar spaces, and some necrotic changes were noted, especially in the middle lobes. These severe pathological changes were not observed in the WT mice.

FIG. 3.

Histologic examination of lung tissues. Mice were killed 5 weeks after airborne infection with M. tuberculosis Kurono strain, and formalin-fixed sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A and C) or Ziehl-Neelsen stain for acid-fast bacilli (B). (A) Pulmonary tissue from an NF-κB KO mouse infected with Kurono strain. Almost necrotic lesions with numerous neutrophils and epithelioid macrophages (arrow) are shown. Magnification, ×315. (B) Pulmonary tissue from an NF-κB KO mouse infected with Kurono strain. Many acid-fast bacilli are recognized in the necrotic lesion by Ziehl-Neelsen staining. Magnification,×540. (C) Pulmonary tissue from a WT mouse infected with Kurono strain. A discrete granulomatous lesion is recognized. Magnification, ×135.

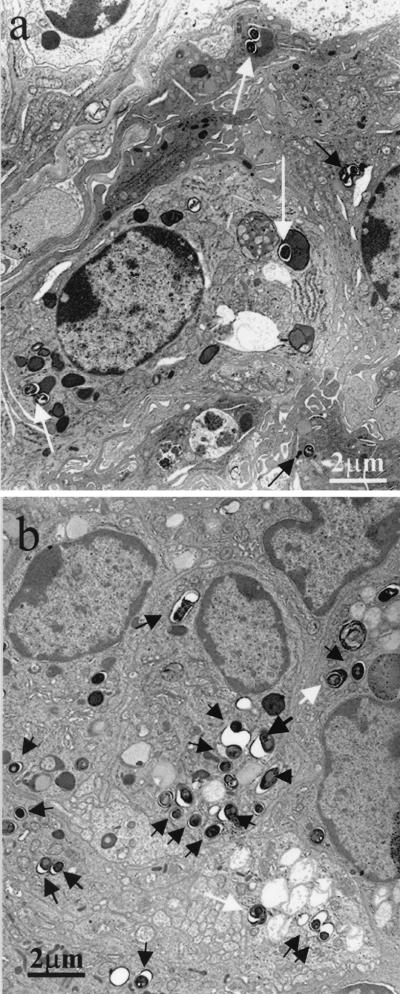

Electron microscopy demonstrated that alveolar macrophages in NF-κB KO mice phagocytosed more tubercle bacilli and that the engulfed tubercle bacilli were located in phagosomes and appeared to escape the host cell killing mechanism. No escape by M. tuberculosis from phagosomes to the cytoplasm was observed. Tubercle bacilli in the phagosomes of macrophages were relatively long and contained many large vacuole-like structures (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Electron micrographs of lung tissue from WT (a) and NF-κB KO (b) mice infected with Kurono strain, obtained 5 weeks after airborne infection. (a) Phagolysosomal fusion (arrows) incorporating many tubercle bacilli is prominent. Magnification, ×5,000. (b) Many phagosomes (arrows) ingest tubercle bacilli. Magnification, ×5,000.

RT-PCR analysis.

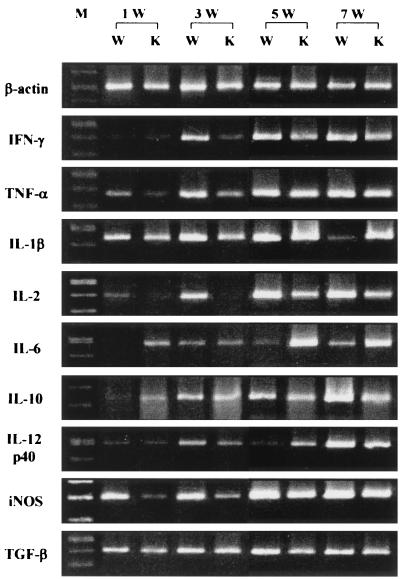

Because the mycobacterial CFU assay and histopathological examination indicated that NF-κB KO mice were much more susceptible to M. tuberculosis infection than WT mice were, we performed RT-PCR to compare the expression levels of major cytokine mRNAs in the lung and spleen tissues of NF-κB KO mice with those in tissues of WT mice. Figure 5 shows the results of RT-PCR in the infected lung tissues at 1, 3, 5, and 7 weeks after infection. Expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and iNOS mRNAs in NF-κB KO mice was significantly lower than that in WT mice until 3 weeks after infection. In particular, IL-2 mRNA expression was very low at 1 and 3 weeks. From 5 weeks after infection onward, the expression levels of these cytokine mRNAs became comparable to those in WT mice. NK-κB KO mice exhibited reduced IL-1β mRNA expression compared to that of WT mice at 1 and 3 weeks after infection. Except at 5 weeks after infection, NF-κB KO mice exhibited reduced IL-12 p40 mRNA expression compared to that of WT mice. On the other hand, expression of IL-10 and TGF-β mRNAs in NF-κB KO mice was similar to that in WT mice, and there was no significant difference in expression intensity between the two groups (P < 0.01). The level of expression of IL-6 mRNA in the two groups was reversed, because the amplified band of the RT-PCR products in NF-κB KO mice was more intense than that of WT mice for the entire experimental period.

FIG. 5.

In vivo expression of various cytokines and iNOS mRNA in Kurono strain-infected mice by RT-PCR. The lung tissues of NF-κB KO and WT mice were removed 1, 3, 5, and 7 weeks after airborne infection. β-Actin gene primer sets were used as an internal control. IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-1β, IL-12, iNOS, and TNF-α mRNA expression is low in NF-κB KO mice. W, wild type; K, knockout; M, size marker.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the role of NF-κB in mycobacterial infection in vivo. In the absence of NF-κB activation, the NF-κB KO mice were highly susceptible to M. tuberculosis infection. Under these conditions, Th1 cytokine IL-2 and IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion levels were significantly low. Although it is reported that NF-κB is required for transcription of Th1 type cytokines, the equivalent mRNA expression levels between WT and NF-κB p50 KO are recognized at 5 and 7 weeks after infection (10). There may be another mechanism of transcription (for example, activation of AP-1). It has been reported that IFN-γ and TNF-α play a major role in defense against mycobacterial infection (2, 5, 7, 8, 17, 25). It is also known that IL-2 augments NK cell activity and stimulates macrophages (19). NF-κB stimulates the production of various cytokines (reviewed in reference 10). Furthermore, some of these cytokines activate NF-κB themselves, thus initiating an autoregulatory feedback loop. In NF-κB KO mice, NF-κB cannot induce the expression of IL-2, IFN-γ or TNF-α mRNA. This is why NF-κB KO mice cannot survive mycobacterial infection for very long. The NF-κB p50 KO mice used in our experiments are known to have B-cell dysfunction, although they show no developmental abnormalities (22). B cells do not proliferate in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide and are defective in basal and specific antibody production in these mice. It is thought that humoral immunity abonormality has little effect on the development of murine tuberculosis because B cells are not involved in the mycobacterial inflammatory process (13).

iNOS mRNA expression was also depressed in NF-κB p50 KO mice. As evaluated by electron microscopy, tubercle bacilli were proliferating in macrophage phagosomes. In fact, the NO activity of alveolar macrophages from NF-κB KO mice was significantly lower than that from wild-type mice as assessed by an NO assay with Griess agent (reference 12 and data not shown). Low NO activity is due to reduced iNOS mRNA expression in the absence of NF-κB p50.

Although IL-1 activates NF-κB, the level of expression of IL-1β mRNA was within the normal range. Two IL-1-mediated signaling pathways result in the activation of NF-κB and activating protein (AP-1) to express inflammatory cytokines (6, 19, 32). In NF-κB KO mice, AP-1 is induced to express IL-1 although NF-κB is not induced at all; this explains the normal expression of IL-1β mRNA. However, AP-1 is not involved in the TNF-α-mediated signaling event, which explains the low TNF-α mRNA expression in the infected NF-κB KO mice. Although it is expected that IL-6 mRNA expression will be depressed in NF-κB KO mice, IL-6 mRNA expression was higher than that is WT mice. Our NK-κB KO mouse strain is a p50 KO strain, and p65 functions in these mice. Mice lacking this p65 gene die on day 16 of gestation (10). IL-6 is produced by macrophages and Th2. It is known that IL-10 inhibits IL-6 production and expression of IL-6 mRNA posttranscriptionally in monocytic cell lines (27). In our present study, the IL-10 mRNA expression level is low, and this explains the high expression of IL-6 mRNA. IL-6 mRNA expression may be activated in the NF-κB p50 KO mice. Further study is required to explain the high IL-6 mRNA expression in the NK-κB p50 KO mice.

IL-10 and IL-12 mRNA expression levels are low in the NK-κB p50 KO mice. It is known that IFN-γ augments IL-12 production by macrophages (18). Low IFN-γ production may explain the low IL-12 level in our NK-κB KO mice. Low IL-12 mRNA expression may be associated with lack of p50 NF-κB activation (23). It is remain unclear whether low IL-10 mRNA expression is associated with low IL-12 mRNA expression. Similar to the report that human monocyte-derived macrophages infected with M. smegmatis 19-kDa lipoprotein result in reduced production of IL-12 and IL-10, such an event may occur in M. tuberculosis infection (21).

It is important to examine the roles of various transcription factors in inflammatory processes because they control major cytokine expression. We have previously reported that NF-IL6 KO mice developed lethal multifocal necrotic mycobacterial lesions in the lungs, spleen, and liver (26). Since NF-IL6 controls granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression (28), we stressed the relative importance of neutrophils stimulated by G-CSF in the early phase of mycobacterial infection. It has also been reported that activation of IL-6 by M. tuberculosis or lipopolysaccharide is mediated by NF-IL6 and NF-κB (35). Both NF-IL6 and NF-κB are required for efficient expression of IL-6. In the present study, the importance of NF-κB in the development of murine tuberculosis was demonstrated. The importance of NF-κB in infection by other intracellular pathogens and parasites, such as Listeria monocytogenes, M. avium-intracellulare, Treponema pallidum, Rickettsia rickettsii, Theileria parva, and Salmonella enterica seravor Typhimurium, has also been reported (9, 11, 14, 15, 20). Intracellular invasion was found to be a prerequisite for the activation of NF-κB.

In summary, NF-κB activation is a consequence of the interaction of host cells with mycobacterium, and this interaction may play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported in part by an International Collaborative Study Grant to the chief investigator, Isamu Sugawara, from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacuerle P, Henkel T. Function and activation of NK-kappa B in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekker L-G, Moreira A L, Bergtold A, Freeman S, Ryffel B, Kaplan G. Immunopathologic effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha in murine mycobacterial infection are dose dependent. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6954–6961. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6954-6961.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernier R, Barbeau B, Olivier M, Tremblay M J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan can induce NK-kappa B-dependent activation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat in T cells. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:1353–1361. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-6-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown M C, Taffet S M. Lipoarabinomannans derived from different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis differentially stimulate the activation of NF-κB and KBF1 in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1960–1968. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1960-1968.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper A M D, Dalton D K, Stewart T A, Griffin J P, Russel D G, Orme I M. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon-γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinarello C A. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn J L, Chan J, Triebold K J, Dalton D K, Stewart T A, Bloom B R. An essential role for interferon-γ in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–2254. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn J L, Goldstein M M, Chan J, Triebold K J, Pfeffer K, Lowenstein C J, Schreiber R, Mak T W, Bloom B R. Tumor necrosis factor-α is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity. 1995;2:561–572. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gewirtz A T, Rao A S, Simon P O, Jr, Merlin D, Carnes D, Madara J L, Neish A S. Salmonella typhimurium induces epithelial IL-8 expression via Ca2+-mediated activation of the NF-κB pathway. J Clin Investig. 2000;105:79–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI8066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh S, May M J, Kopp E B. NK-κB and REL proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giri D K, Mehta R T, Kansal R G, Aggarwal B B. Mycobacterium avium-intratacellulare complex activates nuclear transcription factor-κB in different cell types through reactive oxygen intermediates. J Immunol. 1998;161:4834–4841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green S J, Crawford R M, Hockmeyer J T, Meltzer M S, Nacy C A. Leishmania major amastigotes initiate the l-arginine-dependent killing mechanism in IFN-γ stimulated macrophages by induction of tumor necrosis factor-α. J Immunol. 1990;145:4290–4297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn H, Kaufmann S H E. The role of cell mediated immunity in bacterial infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:1221–1250. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.6.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauf N, Goebel W, Serfling E, Kuhn M. Listeria monocytogenes infection enhances transcription factor NF-κB in P388D1 macrophage-like cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2740–2749. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2740-2747.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivanov V, Stein B, Baumann I, Dobbelaere D A, Herrlich P, Williams R O. Infection with the intracellular protozoan parasite Theileria parva induces constitutively high levels of NF-κB in bovine T lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4677–4686. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko H, Yamada H, Mizuno S, Udagawa T, Kazumi Y, Sekikawa K, Sugawara I. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in mycobacterium-induced granuloma formation in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-deficient mice. Lab Investig. 1999;79:379–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufmann S H E. Immunity to intracellular bacteria. In: Paul W, editor. Fundamental immunology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 1335–1371. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy T L, Cleveland M G, Kulesza P, Magram J, Murphy K M. Regulation of interleukin 12 p40 expression through an NF-κB half-site. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5258–5267. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIKI kappa B as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature. 1999;398:252–256. doi: 10.1038/18465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norgard M V, Arndt L L, Akins D R, Curetty L L, Harrich D A, Radolf J D. Activation of human monocytic cells by Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and synthetic lipopeptides proceeds via a pathway distinct from that of lipopolysaccharide but involves the transcriptional activator NF-κB. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3845–3852. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3845-3852.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Post F A, Manca C, Neyrolles O, Ryffel B, Young D B, Kaplan G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19-kilodalton lipoprotein inhibits Mycobacterium smegmatis-induced cytokine production by human macrophages in vitro. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1433–1439. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1433-1439.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sha W C, Liou H C, Tuomanen E I, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of the p50 subunit of NF-κB leads to multifocal defects in immune responses. Cell. 1995;80:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sica A, Saccani A, Bottazzi B, Polentarutti N, Vecchi A, van Damme J, Mantovani A. Autocrine production of IL-10 mediates defective IL-12 production and NF-κB activation in tumor-associated macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164:762–767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugawara I, Yamada H, Kazumi Y, Doi N, Otomo K, Aoki T, Mizuno S, Udagawa T, Tagawa Y, Iwakura Y. Induction of granulomas in interferon-γ gene-disrupted mice by avirulent but not by virulent strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:871–877. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-10-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugawara I, Yamada H, Kaneko H, Mizuno S, Takeda K, Akira S. Role of IL-18 in mycobacterial infection in IL-18 gene-disrupted mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2585–2589. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2585-2589.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugawara I, Mizuno S, Yamada H, Matsumoto M, Akira S. Disruption of nuclear factor-interleukin-6 (NF-IL6), a transcription factor, results in severe mycobacterial infection. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:361–366. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63977-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeshita S, Gage J R, Kishimoto T, Vredevoe D L, Martinez-Maza O. Differential regulation of IL-6 gene transcription and expression by IL-4 and IL-10 in human monocytic cell lines. J Immunol. 1996;156:2591–2598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka T, Akira S, Yoshida K, Umemoto M, Yoneda Y, Shirafuji N, Fujiwara H, Suematsu S, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T. Targeted disruption of the NF-IL6 gene discloses its essential role in bacteria killing and tumor cytotoxicity by macrophages. Cell. 1995;80:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tchou-Wong K M, Tanabe O, Chi C, Yie T A, Rom W N. Activation of NF-κB in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced interleukin-2 receptor expression in mononuclear phagocytes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1323–1329. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9710105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toossi Z, Hamilton B D, Phillips M H, Averill L E, Ellner J J, Salvekar A. Regulation of nuclear factor-kappa B and its inhibitor I kappa B-alpha/MAD-3 in monocytes by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and during human tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1997;159:4109–4116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verma I M, Stevenson J K, Schwarz E M, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallach D. Cell death induction by TNF: a matter of self control. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:107–109. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wickremasinghe M I, Thomas L H, Friedland J S. Pulmonary epithelial cells are a source of IL-8 in the response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: essential role of IL-1 from infected monocytes in a NF-kappa B-dependent network. J Immunol. 1999;163:3936–3947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamada H, Mizuno S, Horai R, Iwakura Y, Sugawara I. Protective role of interleukin-1 in mycobacterial infection in IL-1α/β double-knockout mice. Lab Investig. 2000;80:759–767. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Broser M, Rom W N. Activation of the interleukin 6 gene by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or lipopolysaccharide is mediated by nuclear factor NF-IL6 and NF-kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;91:2225–2229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]