Summary

Background

Food processing has been hypothesised to play a role in cancer development; however, data from large-scale epidemiological studies are scarce. This study investigated the association between dietary intake according to amount of food processing and risk of cancer at 25 anatomical sites using data from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study.

Methods

This study used data from the prospective EPIC cohort study, which recruited participants between March 18, 1991, and July 2, 2001, from 23 centres in ten European countries. Participant eligibility within each cohort was based on geographical or administrative boundaries. Participants were excluded if they had a cancer diagnosis before recruitment, had missing information for the NOVA food processing classification, or were within the top and bottom 1% for ratio of energy intake to energy requirement. Validated dietary questionnaires were used to obtain information on food and drink consumption. Participants with cancer were identified using cancer registries or during follow-up from a combination of sources, including cancer and pathology centres, health insurance records, and active follow-up of participants. We performed a substitution analysis to assess the effect of replacing 10% of processed foods and ultra-processed foods with 10% of minimally processed foods on cancer risk at 25 anatomical sites using Cox proportional hazard models.

Findings

521 324 participants were recruited into EPIC, and 450 111 were included in this analysis (318 686 [70·8%] participants were female individuals and 131 425 [29·2%] were male individuals). In a multivariate model adjusted for sex, smoking, education, physical activity, height, and diabetes, a substitution of 10% of processed foods with an equal amount of minimally processed foods was associated with reduced risk of overall cancer (hazard ratio 0·96, 95% CI 0·95–0·97), head and neck cancers (0·80, 0·75–0·85), oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (0·57, 0·51–0·64), colon cancer (0·88, 0·85–0·92), rectal cancer (0·90, 0·85–0·94), hepatocellular carcinoma (0·77, 0·68–0·87), and postmenopausal breast cancer (0·93, 0·90–0·97). The substitution of 10% of ultra-processed foods with 10% of minimally processed foods was associated with a reduced risk of head and neck cancers (0·80, 0·74–0·88), colon cancer (0·93, 0·89–0·97), and hepatocellular carcinoma (0·73, 0·62–0·86). Most of these associations remained significant when models were additionally adjusted for BMI, alcohol and dietary intake, and quality.

Interpretation

This study suggests that the replacement of processed and ultra-processed foods and drinks with an equal amount of minimally processed foods might reduce the risk of various cancer types.

Funding

Cancer Research UK, l'Institut National du Cancer, and World Cancer Research Fund International.

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide, with 19·3 million new cases and 10·0 million deaths in 2020.1 Estimates suggest changes in diet and lifestyle factors could prevent 30–50% of cancer cases.2 Over the past decades, diets have shifted towards the consumption of ultra-processed foods, characterised by increased energy density and reduced nutritional quality.3, 4, 5 According to the NOVA food processing classification system, ultra-processed foods are defined as industrial formulations of chemical compounds that are derived from food and drink but not used in culinary preparations, such as cosmetic additives.6 Ultra-processed foods can contribute to up to 25–60% of the total daily energy intake in high-income and middle-income countries.3, 4, 5, 7 Accumulating evidence suggests intake of ultra-processed food is associated with obesity8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and other adverse health outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, depression, and all-cause mortality.13

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched Medline, Web of Science, and Google Scholar with the search terms “food processing”, “ultra-process*”, “NOVA”, and “cancer”, for publications published in English from database inception until June, 2022. We found that epidemiological evidence has suggested a positive association between consumption of ultra-processed food and breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia outcomes. However, some conflicting results have also been reported. The evidence regarding associations between dietary intakes of minimally processed food, as assessed by the NOVA classification, and cancer risk is scarce, with only a few studies reporting a positive association between consumption of processed food and prostate cancer risk and an inverse association between consumption of minimally processed food and breast cancer risk.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge we have conducted the largest and most comprehensive study to date investigating the association between dietary intake according to the degree of food processing and risk of cancer at 25 anatomical sites using data from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study and assessing whether replacing ultra-processed and processed foods by minimally processed foods might lower cancer risk.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study supports a positive association between the consumption of ultra-processed and processed foods and cancer risk, as found in previous studies (eg, NutriNet-Santé), although some conflicting results were also observed. Most importantly, this study provides robust evidence indicating that the replacement of processed and ultra-processed foods with an equal amount of minimally processed foods should be an important target of cancer prevention strategies in public health, although further research is needed to better understand the best way to achieve this kind of dietary transition.

Intake of ultra-processed foods might increase cancer risk through obesogenic properties and reduced nutritional value, as well as through exposure to food additives and neoformed processing contaminants.14, 15 Although epidemiological evidence has suggested a positive association between consumption of ultra-processed food and overall outcomes of cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, some conflicting results have been reported.16, 17, 18, 19 Furthermore, evidence is scarce regarding associations between dietary intakes of foods exposed to lower levels of processing, as assessed by the NOVA classification, and cancer risk, with one study suggesting a positive association between consumption of processed food and prostate cancer risk20 and another suggesting an inverse association between consumption of minimally processed food and breast cancer risk.16 Therefore, we aimed to investigate the association between dietary intake according to degree of food processing and risk of cancer at 25 anatomical sites using data from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study.

Methods

Study design and participants

EPIC is a multicentre, prospective cohort study, done in 23 centres (eg, universities, university hospitals, cancer research centres) in ten European countries (Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the UK). The ethics committee at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and local ethics centres approved the study. Participants were identified between March 18, 1991, and July 2, 2001, and were excluded from our analysis if they had a cancer diagnosis before recruitment, had missing information for the NOVA classification, or were within the extreme ranking (top and bottom 1%) of the ratio of energy intake to energy requirement. Participant eligibility within each cohort was based on geographical or administrative boundaries.21 All study participants provided written informed consent.

Individuals with cancer were identified after recruitment until Dec 31, 2013, using cancer registries or during follow-up from a combination of sources, including cancer and pathology centres, health insurance records, and active follow-up of participants. The end of follow-up was established as the latest date of follow-up for cancer incidence, death, or end of follow-up, whichever came first. Censoring dates for complete follow-up from cancer registries were between December, 2009, and December, 2013. Only cancer types that have been consistently associated with lifestyle behaviours2, 22 were included in this study: head and neck cancers, oesophageal adenocarcinoma, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, gastric cardia cancer, gastric non-cardia cancer, colon cancer, rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, gallbladder cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, bladder cancer, glioma, thyroid cancer, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, leukaemia, melanoma, breast cancer (premenopausal and postmenopausal), cervical cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer. The codes of each cancer site can be found in the appendix (p 2).

Procedures

At baseline (ie, recruitment into the EPIC cohort) questionnaires were used to obtain information on gender, physical activity, education, smoking, alcohol consumption, and reproductive factors, as described elsewhere.21 Gender data were collected via self-report questionnaires and options were male or female. Bodyweight and height were measured in all centres, except for Oxford (UK), France, and Norway where these data were self-reported. However, these self-reported anthropometric measures were shown to be valid for identifying associations in epidemiological studies.23, 24 Assessed weight and height measurements were used to calculate BMI.

Validated country-specific or centre-specific dietary questionnaires were used to obtain information on food consumption. In most centres, dietary questionnaires were self-administered, except for Ragusa (Italy), Naples (Italy), and Spain, where face-to-face interviews were performed by trained personnel. Extensive semiquantitative dietary questionnaires were used in northern Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, France, and Ragusa (Italy). Semiquantitative food-frequency questionnaires were used in Denmark, Norway, Naples (Italy), Umeå (Sweden), and the UK, whereas a food-frequency questionnaire was used with a 7-day record on hot meals in Malmö (Sweden). We obtained information on the Mediterranean diet score that was calculated by the EPIC cohort investigators.

The standardised EPIC food items were classified according to their level of processing using the NOVA classification system.6 Foods were classified as unprocessed or minimally processed (NOVA 1) if they were natural foods or natural foods altered by methods—eg, freezing, pasteurisation, and other processes that do not add additional salt, sugar, oils or fats, or other food substances. Examples of foods included in NOVA 1 are fresh, dry, or frozen fruits or vegetables; grains, flour, and pasta; fresh or frozen meat; milk; coffee; and beans. We classified processed culinary ingredients (ie, NOVA 2) as substances usually obtained directly from foods in NOVA 1 or from nature (eg, oils, fats, sugar, salt). Foods were classified as processed foods (NOVA 3) if they were industrial products made by foods in NOVA 1 and 2 using preservation methods, such as canning and bottling. Examples of foods included in NOVA 3 are breads, cheeses, beer, wine, and smoked fish. Foods in the ultra-processed group (NOVA 4) included those that were made from formulations of ingredients (ie, salt, sugar, fats, or other substances derived from foods), mostly of exclusive industrial use, and are products resulting from a series of industrial processes. Ultra-processed food usually contains many additives to make it palatable or appealing and is packed using synthetic materials. Examples of foods in this group are processed meats (eg, reconstituted meat products or sausage, ham, and other meat products), carbonated soft drinks, packaged breads and buns, sweet or savoury packaged snacks, chocolate, and ready-to-eat meals.

To account for potential changes in industrialisation and exposure to processed foods over time, and since the dietary intake assessments were done in the 1990s, we created lower-bound, middle-bound, and upper-bound scenarios to categorise foods according to the NOVA classification. The most probable scenario (ie, middle-bound scenario) is the most common environment for food processing in the past 25 years in the countries of interest. If a food was less processed than the middle-bound scenario (eg, home-cooked), it was assigned to a less processed NOVA group for the lower-bound scenario. For example, in countries such as the UK, bread is predominantly industrially produced but was produced in artisanal bakeries in the past. Therefore, it was assigned to NOVA 4 in the middle-bound scenario and NOVA 3 for the lower-bound scenario. When it was uncertain whether the food item could be more processed than the middle-bound scenario, it was assigned to a more processed NOVA group for the upper-bound scenario. For example, in countries such as France, bread is sometimes industrially produced and was mainly produced in artisanal bakeries in the past; thus, it was assigned to NOVA 3 in the middle-bound scenario and to NOVA 4 for the upper-bound scenario. More details on the classification of EPIC foods into the NOVA classification system and the different scenarios are included in a published descriptive paper.25 For each NOVA group, the daily total absolute intake in grams and calories as well as their percentage contribution to the total daily intake in grams and calories were calculated. For NOVA groups 3 and 4, this classification process was repeated after removing alcoholic drinks.

Statistical analysis

The main analyses were performed using the middle-bound scenario for the NOVA classification. The daily percentage intake in grams was used because it also considers foods that do not provide energy (eg, artificially sweetened drinks) and non-nutritional factors associated with food processing (eg, neoformed contaminants). Baseline characteristics were examined for the total population and by sex-specific quartiles for the daily percentage intake in grams of each NOVA food group. Descriptive analyses were performed for each NOVA food group considering the absolute daily intake in calories and grams and the percentage intake. Individuals with missing data for the NOVA category were not included.

The associations between the percentage intake of each NOVA group in grams and the incidence of cancers were assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models. The models were stratified by age at recruitment (in 1-year categories) and centre and adjusted for sex, smoking status and intensity, educational level, physical activity, height, and diabetes (model 1). To investigate the putative effect of food processing independent of the nutritional quality and energy content of foods (eg, due to processing contaminants), we also adjusted for the potential effect of body size, dietary intake and quality, and alcohol intake by adjusting the models further for BMI, Mediterranean diet, alcohol intake, total energy intake, and total fat, sodium, and carbohydrate intakes at recruitment (model 2). Colorectal cancers were further adjusted for fibre and calcium intake in model 2. Renal cell carcinoma was further adjusted for hypertension, and female-specific cancer sites were further adjusted for menopausal status, hormone therapy, oral contraceptive use, age at menarche, and age at first full-term pregnancy in models 1 and 2. In these models, time at entry was age at recruitment and exit time was age at cancer diagnosis, end of follow-up, loss to follow-up, or death, whichever came first. These analyses were repeated using the processed and ultra-processed food groups without alcoholic drinks. To test the proportional hazards assumption, we generated log–log (survival) versus log–time plots.

Since the percentage intake of the NOVA groups corresponds to compositional data, a substitution analysis was performed. To assess the effect of replacing 10% of processed foods and ultra-processed foods with minimally processed foods on cancer risk, we used Cox proportional hazards regression models. For each cancer site, we included the relative intakes corresponding to NOVA groups 1, 2, and 4 in the same model. As a result, NOVA 3 served as a reference, and the relative risk estimate for NOVA 1 represented the substitution of 10% of NOVA 3 by 10% of NOVA 1, while keeping the other NOVA groups constant. We repeated the same analyses using NOVA 4 as the reference. The models were stratified by age at recruitment (in 1-year categories) and centre and adjusted for the same covariates as in the associations analyses. Similarly, the analyses were also repeated using the processed and ultra-processed food groups without alcoholic drinks.

Sensitivity analyses were performed (1 SD increment only) by excluding individuals diagnosed with cancer during their first 2 years of follow-up. The adjustment for total water intake was tested in the models using the daily percentage intake of NOVA food in grams. The association between food processing and cancer risk was also tested using daily percentage calorie intake, as well as lower-bound and upper-bound scenarios for the NOVA classification. Statistical tests used in the analysis were all two-sided, and Bonferroni correction for 26 tests was applied for multiple testing. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA (version 11.0), and graphs were created with R (version 3.6.3).

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Between March 18, 1991, and July 2, 2001, 521 324 participants were recruited and 450 111 were included in this analysis. 71 213 participants were excluded because they had a cancer diagnosis before recruitment, had missing information for the NOVA classification, or were within the extreme ranking (top and bottom 1%) of the ratio of energy intake to energy requirement. Participants from Greece had to be excluded due to data access issues for this country. 318 686 (70·8%) of 450 111 participants were female individuals and 131 425 (29·2%) were male individuals, and 47 573 participants were diagnosed with cancer, with a mean of 14·1 follow-up years (SD 3·9). Participants had a mean age of 51 years (SD 9·7) and a mean BMI of 25·3 kg/m2 (SD 4·2) at recruitment. Participants in the highest quartile of ultra-processed food consumption were younger, taller, less likely to have higher education, and more likely to be physically active, had a higher intake of energy, sodium, fat, and carbohydrate and a lower intake of alcohol, and had a lower score for the Mediterranean diet than participants in the lowest quartile of ultra-processed food consumption (appendix pp 3–4).

Minimally processed foods (NOVA 1) contributed a mean of 71·5% (SD 12·1) to the total daily diet in grams (table 1), with France showing the highest mean contribution for this NOVA group (table 2). Processed culinary ingredients (NOVA 2) contributed a mean of 1·2% (1·0) to the total daily diet in grams and processed foods (NOVA 3) contributed 13·6% (10·0) to the total diet in grams. Italy showed the highest contribution to the total daily diet in grams for processed culinary ingredients and for processed foods (table 2). Overall, ultra-processed foods (NOVA 4) contributed a mean of 13·7% (8·8) to the total daily diet in grams, and Norway had the highest contribution. The description of the contributions by food groups can be found in the appendix (pp 5–6).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for all participants and sex-specific quartiles of percentage daily intake of ultra-processed foods in diet in grams

| All participants (n=450 111) | 1st quartile | 2nd quartile | 3rd quartile | 4th quartile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of grams in total diet | ||||||

| NOVA 1 | 71·5% (12·1) | 76·8% (12·7) | 75·1% (10·8) | 72·1% (9·6) | 63·0% (10·3) | |

| NOVA 2 | 1·2% (1·0) | 1·6% (1·09) | 1·2% (1·1) | 1·1% (1·0) | 0·9% (0·8) | |

| NOVA 3 | 13·6% (9·9) | 16·9% (12·1) | 14·5% (10·2) | 12·6% (8·9) | 10·8% (7·5) | |

| NOVA 4 | 13·7% (8·8) | 4·6% (1·7) | 9·2% (1·5) | 14·2% (1·8) | 25·3% (7·8) | |

| Proportion of kcals in total diet | ||||||

| NOVA 1 | 35·9% (10·5) | 41·7% (10·8) | 37·4% (9·8) | 34·8% (9·4) | 30·9% (8·9) | |

| NOVA 2 | 7·4% (6·0) | 11·3% (6·3) | 7·8% (6·0) | 6·1% (5·4) | 4·8% (4·6) | |

| NOVA 3 | 24·6% (11·8) | 31·3% (12·0) | 26·6% (10·9) | 22·8% (10·6) | 18·7% (10·0) | |

| NOVA 4 | 32·0% (14·9) | 15·6% (9·0) | 28·1% (10·3) | 36·1% (10·5) | 45·6% (11·3) | |

| Age, years | 51·1 (9·7) | 52·9 (7·7) | 52·5 (8·7) | 51·2 (10·1) | 48·2 (11·1) | |

| Height, cm | 166·2 (8·8) | 163·8 (8·5) | 166·0 (8·9) | 166·9 (8·8) | 167·7 (8·6) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25·3 (4·2) | 25·4 (4·3) | 25·2 (4·1) | 25·2 (4·1) | 25·2 (4·3) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 131 425 (29·2%) | 27 931 (27·8%) | 33 591 (29·4%) | 34 688 (29·7%) | 35 215 (29·8%) | |

| Women | 318 686 (70·8%) | 72 613 (72·2%) | 80 713 (70·6%) | 82 266 (70·3%) | 83 094 (70·2%) | |

| Education | ||||||

| None | 15 551 (3·5%) | 8146 (8·1%) | 3389 (3·0%) | 2287 (2·0%) | 1729 (1·5%) | |

| Primary school | 111 064 (24·7%) | 27 646 (27·5%) | 29 374 (25·7%) | 27 791 (23·8%) | 26 253 (22·2%) | |

| Secondary or technical school | 197 692 (43·9%) | 37 949 (37·7%) | 48 923 (42·8%) | 52 782 (45·1%) | 58 038 (49·1%) | |

| Longer education | 108 931 (24·2%) | 24 657 (24·5%) | 29 498 (25·8%) | 28 699 (24·5%) | 26 077 (22·0%) | |

| Not specified | 16 873 (3·7%) | 2146 (2·1%) | 3120 (2·7%) | 5395 (4·6%) | 6212 (5·3%) | |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never | 219 294 (48·7%) | 51 597 (51·3%) | 55 449 (48·5%) | 55 867 (47·8%) | 56 381 (47·7%) | |

| Former | 122 680 (27·3%) | 24 955 (24·8%) | 31 695 (27·7%) | 33 545 (28·7%) | 32 485 (27·5%) | |

| Current | 99 714 (22·2%) | 21 734 (21·6%) | 25 327 (22·2%) | 25 699 (22·0%) | 26 954 (22·8%) | |

| Unknown | 8423 (1·9%) | 2258 (2·2%) | 1833 (1·6%) | 1843 (1·6%) | 2489 (2·1%) | |

| Smoking intensity | ||||||

| Never | 191 403 (42·5%) | 39 634 (39·4%) | 46 545 (40·7%) | 50 967 (43·6%) | 54 257 (45·9%) | |

| Current, one to 15 cigarettes per day | 52 440 (11·7%) | 9875 (9·8%) | 13 264 (11·6%) | 13 967 (11·9%) | 15 334 (13·0%) | |

| Current, 16–25 cigarettes per day | 27 623 (6·1%) | 6060 (6·0%) | 6924 (6·1%) | 7 119 (6·1%) | 7520 (6·4%) | |

| Current, ≥26 cigarettes per day | 6559 (1·5%) | 1965 (2·0%) | 1658 (1·5%) | 1 457 (1·2%) | 1479 (1·3%) | |

| Former, quit ≤10 years | 43 340 (9·6%) | 9218 (9·2%) | 10 724 (9·4%) | 11 397 (9·7%) | 12 001 (10·1%) | |

| Former, quit 11–20 years | 37 670 (8·4%) | 8145 (8·1%) | 9794 (8·6%) | 10 210 (8·7%) | 9521 (8·0%) | |

| Former, quit >20 years | 36 845 (8·2%) | 6716 (6·7%) | 9878 (8·6%) | 10 610 (9·1%) | 9641 (8·1%) | |

| Current, pipe, cigar, or occasional smoker | 39 907 (8·9%) | 16 234 (16·1%) | 12 266 (10·7%) | 7419 (6·3%) | 3988 (3·4%) | |

| Unknown | 14 324 (3·2%) | 2 697 (2·7%) | 3251 (2·8%) | 3808 (3·3%) | 4568 (3·9) | |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Inactive | 88 032 (19·5%) | 25 063 (24·9%) | 22 456 (19·6%) | 21 292 (18·2%) | 19 221 (16·2%) | |

| Moderately inactive | 149 941 (33·3%) | 35 710 (35·5%) | 39 663 (34·7%) | 38 576 (33·0%) | 35 992 (30·4%) | |

| Moderately active | 120 199 (26·7%) | 24 494 (24·34%) | 28 879 (25·3%) | 30 653 (26·2%) | 36 173 (30·6%) | |

| Active | 83 115 (18·5%) | 14 900 (14·8%) | 21 845 (19·1%) | 23 380 (20·0%) | 22 990 (19·4%) | |

| Missing | 8824 (2·0%) | 377 (0·4%) | 1461 (1·3%) | 3053 (2·6%) | 3933 (3·3%) | |

| Energy intake, kcal/day | 2076 (618·8) | 2027·5 (612·1) | 2061 (601·7) | 2086·3 (604·2) | 2123·4 (650·5) | |

| Alcohol intake, g/day | 11·7 (16·8) | 15·2 (21·2) | 13·3 (17·4) | 10·9 (14·7) | 8·1 (12·4) | |

| Fibre intake, g/day | 22·8 (7·8) | 23·1 (8·0) | 22·6 (7·6) | 22·7 (7·7) | 22·8 (7·9) | |

| Calcium intake, g/day | 1079 (447·3) | 1144·2 (509·8) | 1095·5 (452·9) | 1067 (417·7) | 1018 (402·4) | |

| Total fat intake, g/day | 81·5 (29·6) | 79·1 (28·1) | 81·3 (28·5) | 82·5 (29·6) | 82·7 (31·7) | |

| Sodium intake, g/day | 2608 (1147) | 2473·8 (952·8) | 2648·7 (1096) | 2631·1 (1180·5) | 2659·6 (1292·9) | |

| Carbohydrate intake, g/day | 254·2 (80·7) | 236·3 (75·9) | 243·6 (72·3) | 255·8 (75·1) | 277·8 (91·2) | |

| Mediterranean diet | ||||||

| Low | 114 222 (25·4%) | 11 447 (11·4%) | 27 213 (23·8%) | 34 716 (29·7%) | 40 846 (34·5%) | |

| Medium | 211 941 (47·1%) | 41 596 (41·4%) | 55 576 (48·6%) | 57 731 (49·4%) | 57 038 (48·2%) | |

| High | 123 948 (27·5%) | 47 501 (47·2%) | 31 515 (27·6%) | 24 507 (21·0%) | 20 425 (17·3%) | |

Data are mean (SD) or n (%). All differences in baseline characteristics between quartiles were significant (all p<0·001). Quartile 1 contains participants with the lowest consumption of ultra-processed foods, and quartile 4 contains those with the highest consumption of ultra-processed foods. NOVA 1=unprocessed or minimally processed foods. NOVA 2=processed culinary ingredients. NOVA 3=processed foods. NOVA 4=ultra-processed foods.

Table 2.

Percentage and absolute contributions of NOVA groups to the total daily diet by mass and energy, for the total cohort and by country

| Absolute contribution by mass (g) | Percentage contribution by mass (%) | Absolute contribution by energy (kcal) | Percentage contribution by energy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimally processed foods (NOVA 1) | ||||

| All countries | 1965·0 (832·9) | 71·5% (12·1) | 752·5 (271·5) | 35·9% (10·5) |

| France | 2492·0 (796·1) | 79·6% (8·0) | 854·8 (282·8) | 39·8% (9·8) |

| Italy | 1125·7 (365·1) | 61·1% (10·9) | 788·1 (262·7) | 34·7% (7·7) |

| Spain | 1376·7 (391·9) | 70·9% (12·7) | 916·4 (265·4) | 42·7% (10·1) |

| UK | 2070·7 (613·3) | 73·0% (10·7) | 767·4 (252·4) | 37·6% (10·8) |

| Netherlands | 2186·3 (621·8) | 73·3% (10·2) | 727·6 (217·7) | 34·0% (8·6) |

| Germany | 1853·3 (765·8) | 64·2% (13·4) | 514·9 (190·2) | 24·6% (7·7) |

| Sweden | 1941·1 (737·7) | 73·8% (9·9) | 750·1 (275·6) | 37·1% (10·4) |

| Denmark | 2731·1 (799·8) | 74·1% (11·6) | 767·4 (251·6) | 34·8% (8·8) |

| Norway | 1190·6 (381·1) | 68·1% (9·7) | 622·6 (189·5) | 37·6% (8·7) |

| Processed culinary ingredients (NOVA 2) | ||||

| All countries | 28·8 (23·5) | 1·2% (1·0) | 160·1 (145·2) | 7·3% (6·0) |

| France | 42·8 (19·4) | 1·4% (0·6) | 225·8 (104·8) | 10·5% (4·3) |

| Italy | 50·1 (21·0) | 2·7% (1·0) | 351·7 (136·4) | 15·5% (4·6) |

| Spain | 43·2 (21·4) | 2·2% (1·0) | 306·5 (142·1) | 13·9% (5·0) |

| UK | 15·7 (16·7) | 0·6% (0·6) | 67·5 (87·5) | 3·1% (3·8) |

| Netherlands | 23·4 (23·1) | 0·8% (0·8) | 122·3 (105·3) | 5·4% (4·2) |

| Germany | 28·2 (23·4) | 1·0% (0·8) | 159·1 (119·7) | 7·4% (4·9) |

| Sweden | 27·9 (25·4) | 1·1% (1·0) | 112·9 (119·3) | 5·3% (5·0) |

| Denmark | 16·5 (13·6) | 0·5% (0·4) | 70·6 (76·2) | 3·1% (3·1) |

| Norway | 12·5 (8·7) | 0·7% (0·5) | 67·2 (55·5) | 4·0% (3·0) |

| Processed foods (NOVA 3) | ||||

| All countries | 357·2 (307·7) | 13·6% (10·0) | 540·7 (335·9) | 24·6% (11·8) |

| France | 356·5 (196·7) | 11·9% (6·4) | 665·8 (319·9) | 30·1% (10·8) |

| Italy | 482·8 (255·6) | 25·8% (10·4) | 803·7 (353·2) | 34·4% (9·7) |

| Spain | 394·3 (328·3) | 18·9% (11·7) | 650·2 (398·8) | 27·8% (11·3) |

| UK | 226·7 (230·1) | 7·8% (6·6) | 305·6 (181·6) | 14·4% (6·9) |

| Netherlands | 328·1 (271) | 10·9% (7·1) | 602·9 (269·8) | 27·2% (8·0) |

| Germany | 525·8 (406·0) | 18·3% (10·8) | 753·6 (314·7) | 35·0% (10·0) |

| Sweden | 311·5 (217·5) | 11·9% (6·7) | 509·7 (253·4) | 24·2% (8·0) |

| Denmark | 453·1 (425·3) | 12·1% (9·8) | 420·7 (228·3) | 18·6% (8·2) |

| Norway | 140·9 (74·5) | 8·3% (4·2) | 208·0 (96·9) | 12·4% (4·8) |

| Ultra-processed foods (NOVA 4) | ||||

| All countries | 363·7 (264·2) | 13·7% (8·8) | 684·1 (394·1) | 32·0% (14·9) |

| France | 215·5 (135·6) | 7·2% (4·5) | 430·1 (237·1) | 19·6% (8·9) |

| Italy | 194·1 (146·2) | 10·4% (6·5) | 355·8 (207·5) | 15·5% (7·5) |

| Spain | 156·9 (140·7) | 8·0% (6·4) | 349·2 (239·9) | 15·6% (9·3) |

| UK | 520·5 (294·6) | 18·6% (9·1) | 957·8 (408·0) | 44·9% (11·3) |

| Netherlands | 444·9 (237·5) | 15·0% (7·1) | 737·4 (293·1) | 33·4% (8·2) |

| Germany | 463·9 (294·8) | 16·5% (9·0) | 725·3 (361·6) | 32·9% (10·3) |

| Sweden | 340·0 (205·3) | 13·3% (6·8) | 702·5 (319·5) | 33·4% (9·4) |

| Denmark | 482·1 (294·6) | 13·3% (7·4) | 984·7 (380·2) | 43·5% (10·0) |

| Norway | 386·9 (163·2) | 22·8% (8·8) | 776·7 (254·7) | 46·1% (9·0) |

Data are mean (SD).

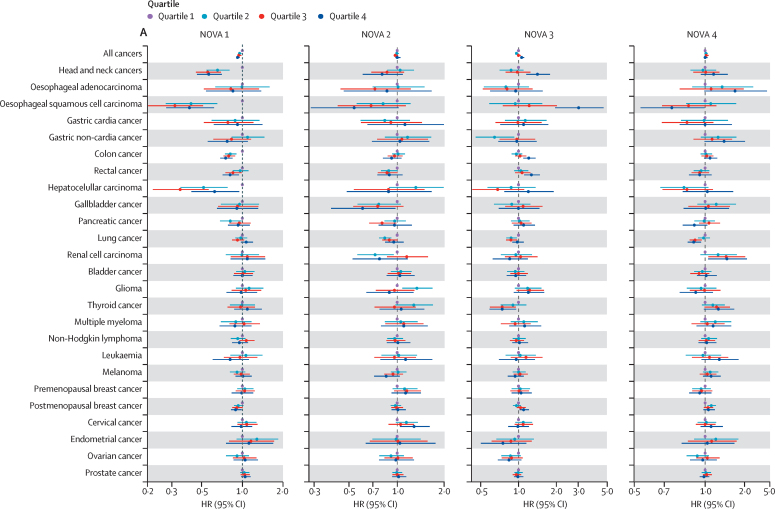

The association between the percentage dietary intake of each NOVA group in grams and risks for overall cancer and 25 cancer sites are shown by quartiles in the figure. In model 1, after adjustment and Bonferroni correction for sociodemographic and lifestyle variables (excluding diet), increased intake of minimally processed foods (NOVA 1) was associated with reduced risk for overall cancer, head and neck cancers, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colon cancer, rectal cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma (table 3). Results by quartiles showed a significant trend for all these associations (figure A; appendix pp 7–9). Increased intake of processed food (NOVA 3) was associated with increased risk of overall cancer, head and neck cancers, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colon cancer, rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and postmenopausal breast cancer (table 3). In the analysis by quartiles, all these associations showed a significant trend apart from hepatocellular carcinoma and postmenopausal breast cancer, which were not significant after Bonferroni correction (figure A). Increased intake of ultra-processed foods (NOVA 4) was associated with increased risk of cancers of the head and neck only after Bonferroni correction.

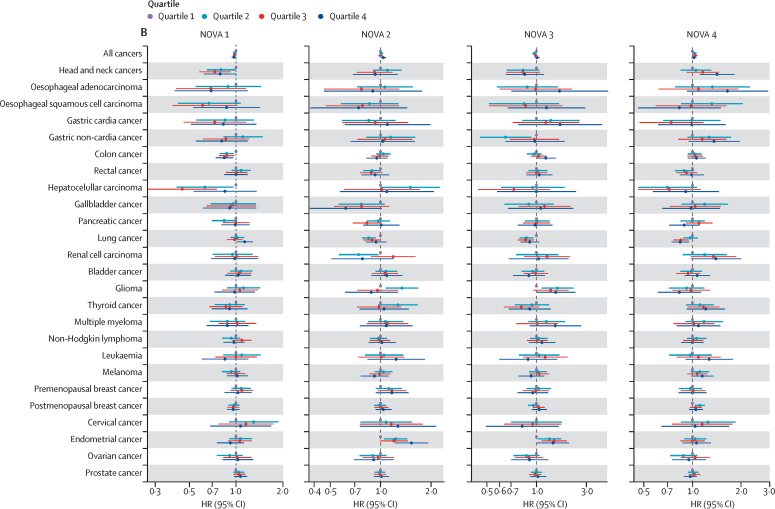

Figure.

Forest plot for the association between daily percentage intake of NOVA groups in grams and cancer risk by quartiles in model 1 (A) and model 2 (B)

Quartile 1 contains participants with the lowest consumption of that specific NOVA group and was used as the reference group, and quartile 4 contains those with the highest consumption. HRs, 95% CIs, and p values are presented in the appendix (pp 7–12). HR=hazard ratio. NOVA 1=unprocessed or minimally processed foods. NOVA 2=processed culinary ingredients. NOVA 3=processed foods. NOVA 4=ultra-processed foods.

Table 3.

Associations between percentage daily intake of NOVA group foods by mass (g) and cancer risk

| NOVA 1 | NOVA 2 | NOVA 3 | NOVA 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n=47 573) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·96 (0·95–0·97)s*† | 1·00 (0·99–1·02) | 1·04 (1·03–1·05)*† | 1·00 (0·99–1·01) |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·97–0·99)*† | 1·02 (1·00–1·03)* | 1·02 (1·01–1·04)* | 1·01 (0·99–1·02) |

| Head and neck (n=821) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·76 (0·71–0·82)*† | 0·93 (0·85–1·02) | 1·21 (1·14–1·28)*† | 1·14 (1·06–1·24)*† |

| Model 2 | 0·86 (0·78–0·94)*† | 0·98 (0·89–1·08) | 0·98 (0·89–1·08) | 1·25 (1·15–1·35)*† |

| Oesophageal adenocarcinoma (n=223) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·89 (0·77–1·02) | 1·02 (0·86–1·21) | 0·98 (0·84–1·13) | 1·21 (1·05–1·39)* |

| Model 2 | 0·79 (0·66–0·95)* | 1·01 (0·84–1·21) | 1·12 (0·88–1·42) | 0·79 (0·64–0·96)* |

| Oesophageal sqamous cell carcinoma (n=194) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·61 (0·53–0·70)*† | 0·92 (0·75–1·12) | 1·75 (1·56–1·95)*† | 0·79 (0·64–0·96) |

| Model 2 | 0·83 (0·69–0·99)* | 1·04 (0·85–1·28) | 1·33 (1·11–1·59)*† | 0·90 (0·72–1·11) |

| Gastric cardia (n=239) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·00 (0·87–1·16) | 1·14 (0·96–1·34) | 0·96 (0·84–1·10) | 1·02 (0·87–1·19) |

| Model 2 | 0·96 (0·80–1·14) | 1·14 (0·95–1·35) | 1·04 (0·83–1·30) | 1·00 (0·85–1·19) |

| Gastric non-cardia (n=379) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·88 (0·78–0·98)* | 1·07 (0·95–1·20) | 1·06 (0·95–1·19) | 1·10 (0·98–1·24) |

| Model 2 | 0·87 (0·75–1·00) | 1·08 (0·95–1·22) | 1·12 (0·95–1·32) | 1·07 (0·95–1·22) |

| Colon (n=3993) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·88 (0·85–0·92)*† | 0·96 (0·92–1·01) | 1·12 (1·08–1·17)*† | 1·04 (1·00–1·09)* |

| Model 2 | 0·91 (0·86–0·96)*† | 0·97 (0·93–1·02) | 1·12 (1·06–1·19)*† | 1·03 (0·98–1·08) |

| Rectal (n=2162) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·91 (0·86–0·96)*† | 0·93 (0·86–0·98)* | 1·12 (1·07–1·18)*† | 1·00 (0·94–1·06) |

| Model 2 | 0·99 (0·93–1·06) | 0·93 (0·86–0·98)* | 1·03 (0·95–1·11) | 0·98 (0·93–1·04) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (n=215) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·72 (0·62–0·82)*† | 0·95 (0·79–1·14) | 1·22 (1·08–1·38)*† | 1·23 (1·07–1·42)* |

| Model 2 | 0·79 (0·67–0·94)* | 0·99 (0·83–1·19) | 1·19 (0·98–1·44) | 1·14 (0·97–1·34) |

| Gallbladder (n=335) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·95 (0·84–1·09) | 0·94 (0·81–1·10) | 1·09 (0·96–1·23) | 0·96 (0·84–1·10) |

| Model 2 | 0·97 (0·84–1·14) | 0·96 (0·82–1·13) | 1·15 (0·96–1·40) | 0·93 (0·80–1·09) |

| Pancreatic (n=1236) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·96 (0·90–1·03) | 0·96 (0·89–1·04) | 1·05 (0·98–1·13) | 0·98 (0·92–1·05) |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·90–1·06) | 0·97 (0·89–1·06) | 1·00 (0·91–1·11) | 1·01 (0·94–1·10) |

| Lung (n=3783) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·00 (0·97–1·04) | 1·01 (0·97–1·06) | 1·02 (0·99–1·06) | 0·94 (0·90–0·98)* |

| Model 2 | 1·02 (0·97–1·07) | 1·01 (0·96–1·05) | 1·02 (0·97–1·08) | 0·96 (0·91–1·00) |

| Renal cell carcinoma (n=464) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·01 (0·91–1·14) | 0·91 (0·78–1·05) | 0·92 (0·82–1·02) | 1·10 (0·99–1·23) |

| Model 2 | 0·95 (0·82–1·08) | 0·90 (0·77–1·05) | 0·97 (0·81–1·15) | 1·09 (0·96–1·24) |

| Bladder (n=1586) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·00 (0·94–1·06) | 1·02 (0·96–1·09) | 1·01 (0·96–1·06) | 0·98 (0·92–1·05) |

| Model 2 | 1·01 (0·94–1·08) | 1·04 (0·97–1·11) | 0·98 (0·90–1·07) | 1·00 (0·93–1·06) |

| Glioma (n=653) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·98 (0·89–1·07) | 0·95 (0·85–1·06) | 1·06 (0·97–1·15) | 0·97 (0·88–1·08) |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·87–1·09) | 0·94 (0·84–1·05) | 1·14 (0·99–1·31) | 0·96 (0·86–1·06) |

| Thyroid (n=759) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·03 (0·93–1·13) | 1·00 (0·90–1·10) | 0·89 (0·80–0·98)* | 1·08 (0·98–1·18) |

| Model 2 | 0·93 (0·84–1·05) | 0·98 (0·88–1·09) | 1·02 (0·88–1·18) | 1·06 (0·96–1·18) |

| Multiple myeloma (n=588) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·96 (0·87–1·05) | 1·08 (0·98–1·20) | 1·02 (0·92–1·13) | 1·04 (0·94–1·15) |

| Model 2 | 0·94 (0·83–1·06) | 1·08 (0·97–1·20) | 1·09 (0·94–1·27) | 1·01 (0·91–1·13) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=2356) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·99 (0·94–1·04) | 1·03 (0·97–1·09) | 1·01 (0·97–1·07) | 1·00 (0·96–1·05) |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·93–1·05) | 1·03 (0·97–1·09) | 1·05 (0·97–1·14) | 0·98 (0·93–1·04) |

| Leukaemia (n=503) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·94 (0·84–1·05) | 1·03 (0·92–1·16) | 1·00 (0·89–1·12) | 1·08 (0·97–1·20) |

| Model 2 | 0·97 (0·85–1·10) | 1·04 (0·92–1·18) | 0·96 (0·81–1·14) | 1·05 (0·94–1·17) |

| Melanoma (n=2312) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·00 (0·94–1·05) | 0·96 (0·90–1·02) | 0·98 (0·93–1·04) | 1·02 (0·97–1·07) |

| Model 2 | 0·99 (0·93–1·05) | 0·98 (0·92–1·05) | 0·97 (0·89–1·06) | 1·03 (0·97–1·09) |

| Premenopausal breast (n=2223) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·01 (0·94–1·08) | 1·02 (0·95–1·10) | 1·07 (0·99–1·16) | 0·94 (0·88–1·00) |

| Model 2 | 1·03 (0·95–1·11) | 1·02 (0·95–1·10) | 1·02 (0·90–1·13) | 0·96 (0·90–1·02) |

| Postmenopausal breast (n=7724) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·96 (0·92–0·99)* | 1·00 (0·96–1·04) | 1·07 (1·03–1·12)*† | 1·01 (0·97–1·05) |

| Model 2 | 0·99 (0·95–1·03) | 1·01 (0·97–1·05) | 1·02 (0·97–1·09) | 1·00 (0·96–1·04) |

| Cervical (n=354) | ||||

| Model 1 | 0·96 (0·83–1·13) | 1·04 (0·87–1·25) | 0·98 (0·80–1·19) | 1·04 (0·91–1·20) |

| Model 2 | 0·94 (0·78–1·11) | 1·10 (0·92–1·32) | 1·08 (0·83–1·41) | 1·03 (0·89–1·19) |

| Endometrial (n=1932) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·02 (0·95–1·10) | 1·03 (0·95–1·12) | 0·94 (0·86–1·03) | 1·01 (0·94–1·08) |

| Model 2 | 1·00 (0·92–1·08) | 1·09 (1·00–1·19)* | 1·04 (0·92–1·17) | 0·97 (0·90–1·05) |

| Ovarian (n=1415) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·00 (0·92–1·09) | 0·99 (0·90–1·09) | 0·93 (0·84–1·04) | 1·04 (0·96–1·13) |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·89–1·08) | 0·96 (0·87–1·06) | 0·98 (0·85–1·14) | 1·03 (0·95–1·11) |

| Prostate (n=6926) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1·02 (1·00–1·05) | 1·02 (0·99–1·05) | 0·98 (0·96–1·01) | 0·99 (0·96–1·02) |

| Model 2 | 1·03 (1·00–1·07) | 1·01 (0·98–1·05) | 0·97 (0·93–1·01) | 0·99 (0·96–1·02) |

Data are hazard ratio (95% CI). NOVA 1=unprocessed and minimally processed foods. NOVA 2=processed culinary ingredients. NOVA 3=processed foods. NOVA 4=ultra-processed foods.

Significant (p<0·05) before Bonferroni correction.

Significant (p<0·002) after Bonferroni correction, which considered analysis for all cancers and 25 cancer-specific sites.

After further adjustment for dietary intake and quality, alcohol intake, and body size factors (model 2), and Bonferroni correction, increased intake of minimally processed food (NOVA 1) remained associated with reduced risk of overall cancer and cancers of the head and neck and colon. Results by quartiles showed a significant trend for the associations with cancers of the head and neck and colon, but they did not reach significance after Bonferroni correction (figure B). The intake of processed culinary ingredients (NOVA 2) was borderline positively associated with endometrial cancer risk (table 3), and results by quartiles showed a significant trend (figure B; appendix pp 10–12). Processed food intake (NOVA 3) remained associated with an increased risk of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and colon cancer. However, neither of these associations were significant in the quartile analysis (figure B). The proportion of ultra-processed food intake (NOVA 4) in the total diet remained associated with an increased risk of head and neck cancers (table 3), and results by quartiles showed a significant trend, but it did not reach significance after Bonferroni correction (figure B).

Analyses were repeated for processed and ultra-processed food groups (NOVA 3 and 4) after removing alcoholic drinks from the NOVA classification to investigate the putative effect of food processing while excluding the effect of alcoholic beverages (appendix p 13). After Bonferroni correction, increased intake of processed food (NOVA 3) remained associated with increased risk of colon cancer in model 1 (hazard ratio [HR] 1·07, 95% CI 1·02–1·13) and model 2 (1·08, 1·03–1·14). However, this association was not significant when assessed by quartiles (appendix pp 14–15). After Bonferroni correction, increased ultra-processed food intake (NOVA 4) remained associated with increased risk of head and neck cancers in model 1 (1·18, 1·10–1·27) and model 2 (1·21, 1·12–1·31) and with increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in model 1 (1·29, 1·13–1·48) and model 2 (1·16, 1·00–1·35). Results by quartiles showed a significant trend for the association with head and neck cancers only.

In our substitution analysis, for model 1, a 10% substitution of processed foods (NOVA 3) with an equal amount of minimally processed foods (NOVA 1) was associated with reduced risk of overall cancer, head and neck cancers, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colon cancer, rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and postmenopausal breast cancer (table 4). A 10% substitution of ultra-processed foods (NOVA 4) with 10% minimally processed foods (NOVA 1) was associated with reduced risks of head and neck cancers, colon cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In model 2, the 10% substitution of processed foods (NOVA 3) with 10% of minimally processed foods (NOVA 1) remained associated with reduced risk of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and colon cancer. The substitution of ultra-processed foods (NOVA 4) with minimally processed foods (NOVA 1) remained associated with reduced risk of head and neck cancers. These associations were shown to be a good fit according to the likelihood-ratio test, after Bonferroni correction. The substitution analysis considering the NOVA classification without alcoholic drinks mirrored previous results (appendix pp 13–15).

Table 4.

Substitution models replacing 10% of processed foods (NOVA 3) and ultra-processed foods (NOVA 4) with 10% of minimally processed foods (NOVA 1) and their effect on cancer risk

|

NOVA classification with alcoholic drinks |

NOVA classification without alcoholic drinks |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substitution of NOVA 3 by NOVA 1 | Substitution of NOVA 4 by NOVA 1 | p value | Substitution of NOVA 3 by NOVA 1 | Substitution of NOVA 4 by NOVA 1 | p value | |

| All | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·96 (0·95–0·97)* | 0·99 (0·97–1·00)* | <0·0001*† | 0·96 (0·96–0·97)* | 0·97 (0·96–0·97)* | <0·0001* |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·97–1·00)* | 0·99 (0·97–1·00)* | 0·0012*† | 0·98 (0·97–0·99)* | 0·98 (0·97–0·99)* | 0·0011* |

| Head and neck | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·80 (0·75–0·85)* | 0·80 (0·74–0·88)* | <0·0001*† | 0·76 (0·72–0·81)* | 0·76 (0·72–0·81)* | <0·0001*† |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·90–1·08) | 0·78 (0·71–0·85)* | <0·0001*† | 0·83 (0·76–0·89)* | 0·83 (0·76–0·89)* | <0·0001*† |

| Oesophageal adenocarcinoma | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·98 (0·84–1·14) | 0·80 (0·68–0·94) | 0·15 | 0·90 (0·79–1·02) | 0·90 (0·79–1·02) | 0·41 |

| Model 2 | 0·87 (0·69–1·11) | 0·79 (0·66–0·96) | 0·17 | 0·80 (0·69–0·94) | 0·80 (0·69–0·94) | 0·071 |

| Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·57 (0·51–0·64)* | 1·08 (0·86–1·36) | <0·0001*† | 0·66 (0·59–0·75)* | 0·66 (0·59–0·75)* | <0·0001*† |

| Model 2 | 0·75 (0·63–0·90)* | 1·07 (0·84–1·38) | 0·042 | 0·88 (0·75–1·04) | 0·88 (0·75–1·04) | 0·21 |

| Gastric cardia | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1·03 (0·89–1·18) | 0·98 (0·82–1·17) | 0·64 | 0·99 (0·87–1·12) | 0·99 (0·87–1·12) | 0·49 |

| Model 2 | 0·96 (0·77–1·20) | 0·98 (0·81–1·19) | 0·69 | 0·96 (0·81–1·12) | 0·96 (0·81–1·12) | 0·47 |

| Gastric non-cardia | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·91 (0·82–1·02) | 0·87 (0·76–1·00) | 0·15 | 0·91 (0·82–1·01) | 0·91 (0·82–1·01) | 0·17 |

| Model 2 | 0·88 (0·75–1·05) | 0·90 (0·77–1·04) | 0·18 | 0·90 (0·79–1·02) | 0·90 (0·79–1·02) | 0·30 |

| Colon | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·88 (0·85–0·92)* | 0·93 (0·89–0·97)* | <0·0001*† | 0·90 (0·87–0·93)* | 0·90 (0·87–0·93)* | <0·0001*† |

| Model 2 | 0·88 (0·84–0·94)* | 0·95 (0·90–1·00)* | 0·0004*† | 0·93 (0·89–0·98)* | 0·93 (0·89–0·98)* | 0·0010*† |

| Rectal | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·90 (0·85–0·94)* | 0·98 (0·92–1·04) | <0·0001† | 0·91 (0·87–0·95)* | 0·91 (0·87–0·95)* | 0·0001*† |

| Model 2 | 0·97 (0·90–1·05) | 1·03 (0·95–1·10) | 0·11 | 0·99 (0·93–1·05) | 0·99 (0·93–1·05) | 0·15 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·77 (0·68–0·87)* | 0·73 (0·62–0·86)* | <0·0001*† | 0·72 (0·65–0·81)* | 0·72 (0·65–0·81)* | <0·0001*† |

| Model 2 | 0·82 (0·68–0·99) | 0·84 (0·70–1·00) | 0·031 | 0·80 (0·69–0·92) | 0·80 (0·69–0·92)* | 0·034 |

| Gallbladder | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·92 (0·81–1·05) | 1·03 (0·88–1·21) | 0·53 | 1·01 (0·89–1·14) | 1·01 (0·89–1·14) | 0·26 |

| Model 2 | 0·86 (0·71–1·04) | 1·08 (0·91–1·28) | 0·35 | 1·04 (0·90–1·21) | 1·04 (0·90–1·21) | 0·28 |

| Pancreatic | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·95 (0·88–1·01) | 1·01 (0·93–1·09) | 0·35 | 0·95 (0·90–1·01) | 0·95 (0·90–1·01) | 0·26 |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·89–1·09) | 0·98 (0·90–1·07) | 0·89 | 0·96 (0·89–1·04) | 0·96 (0·89–1·04) | 0·49 |

| Lung | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·98 (0·95–1·02) | 1·06 (1·01–1·11)* | 0·013 | 1·01 (0·98–1·04) | 1·01 (0·98–1·04) | 0·66 |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·93–1·04) | 1·05 (0·99–1·10) | 0·24 | 1·02 (0·98–1·07) | 1·02 (0·98–1·07) | 0·52 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1·08 (0·97–1·20) | 0·91 (0·80–1·03) | 0·12 | 1·04 (0·94–1·15) | 1·04 (0·94–1·15) | 0·33 |

| Model 2 | 1·02 (0·86–1·21) | 0·91 (0·79–1·05) | 0·28 | 0·97 (0·85–1·10) | 0·97 (0·85–1·10) | 0·38 |

| Bladder | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·99 (0·94–1·04) | 1·03 (0·95–1·10) | 0·85 | 1·00 (0·95–1·06) | 1·00 (0·95–1·06) | 0·94 |

| Model 2 | 1·02 (0·95–1·11) | 1·01 (0·93–1·09) | 0·72 | 1·03 (0·97–1·10) | 1·03 (0·97–1·10) | 0·52 |

| Glioma | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·95 (0·86–1·04) | 1·02 (0·91–1·13) | 0·48 | 0·98 (0·91–1·07) | 0·98 (0·91–1·07) | 0·65 |

| Model 2 | 0·87 (0·76–1·00) | 1·05 (0·94–1·18) | 0·14 | 0·99 (0·90–1·10) | 0·99 (0·90–1·10) | 0·57 |

| Thyroid | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1·12 (1·01–1·24) | 0·92 (0·83–1·03) | 0·12 | 1·02 (0·93–1·11) | 1·02 (0·93–1·11) | 0·96 |

| Model 2 | 0·97 (0·84–1·12) | 0·93 (0·83–1·04) | 0·76 | 0·92 (0·83–1·02) | 0·92 (0·83–1·02) | 0·63 |

| Multiple myeloma | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·97 (0·88–1·08) | 0·95 (0·85–1·06) | 0·45 | 0·97 (0·89–1·06) | 0·97 (0·89–1·06) | 0·43 |

| Model 2 | 0·92 (0·79–1·07) | 0·98 (0·87–1·11) | 0·33 | 0·97 (0·87–1·08) | 0·97 (0·87–1·08) | 0·33 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·98 (0·93–1·03) | 0·99 (0·94–1·05) | 0·65 | 1·00 (0·95–1·04) | 1·00 (0·95–1·04) | 0·48 |

| Model 2 | 0·95 (0·88–1·03) | 1·01 (0·95–1·08) | 0·44 | 1·00 (0·95–1·06) | 1·00 (0·95–1·06) | 0·39 |

| Leukaemia | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·99 (0·88–1·10) | 0·91 (0·81–1·03) | 0·60 | 0·95 (0·86–1·05) | 0·95 (0·86–1·05) | 0·78 |

| Model 2 | 1·04 (0·88–1·22) | 0·95 (0·83–1·08) | 0·80 | 0·97 (0·87–1·09) | 0·97 (0·87–1·09) | 0·81 |

| Melanoma | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1·01 (0·96–1·07) | 0·98 (0·92–1·04) | 0·43 | 1·00 (0·95–1·05) | 1·00 (0·95–1·05) | 0·63 |

| Model 2 | 1·02 (0·94–1·11) | 0·97 (0·91–1·03) | 0·61 | 0·99 (0·93–1·04) | 0·99 (0·93–1·04) | 0·92 |

| Premenopausal breast | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·94 (0·87–1·01) | 1·06 (0·99–1·14) | 0·10 | 1·00 (0·94–1·07) | 1·00 (0·94–1·07) | 0·95 |

| Model 2 | 0·99 (0·89–1·11) | 1·05 (0·97–1·13) | 0·62 | 1·04 (0·97–1·11) | 1·04 (0·97–1·11) | 0·74 |

| Postmenopausal breast | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0·93 (0·90–0·97)* | 0·98 (0·95–1·02)* | 0·028* | 0·95 (0·92–0·98)* | 0·95 (0·92–0·98)* | 0·016* |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·92–1·03) | 1·00 (0·96–1·04) | 0·89 | 0·98 (0·94–1·02) | 0·98 (0·94–1·02) | 0·72 |

| Cervical | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1·01 (0·83–1·24) | 0·95 (0·81–1·11) | 0·95 | 0·95 (0·82–1·09) | 0·95 (0·82–1·09) | 0·94 |

| Model 2 | 0·94 (0·72–1·23) | 0·96 (0·81–1·14) | 0·70 | 0·93 (0·79–1·09) | 0·93 (0·79–1·09) | 0·68 |

| Endometrial | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1·07 (0·97–1·17) | 0·99 (0·92–1·07) | 0·55 | 1·02 (0·96–1·09) | 1·02 (0·96–1·09) | 0·84 |

| Model 2 | 0·98 (0·87–1·11) | 1·02 (0·95–1·11) | 0·24 | 1·03 (0·96–1·11) | 1·03 (0·96–1·11) | 0·18 |

| Ovarian | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1·06 (0·96–1·18) | 0·96 (0·88–1·04) | 0·46 | 0·99 (0·92–1·07) | 0·99 (0·92–1·07) | 0·98 |

| Model 2 | 1·01 (0·87–1·16) | 0·97 (0·88–1·06) | 0·79 | 0·98 (0·90–1·07) | 0·98 (0·90–1·07) | 0·85 |

| Prostate | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1·02 (0·99–1·04) | 1·01 (0·98–1·05) | 0·35 | 1·02 (0·99–1·04) | 1·02 (0·99–1·04) | 0·37 |

| Model 2 | 1·04 (1·00–1·08) | 1·01 (0·98–1·05) | 0·27 | 1·02 (0·99–1·05) | 1·02 (0·99–1·05) | 0·37 |

Data are hazard ratio (95% CI) and p value for the likelihood ratio test (the model fit for each analysis; substitution of NOVA 3 by NOVA 1 or NOVA 4 by NOVA 1). NOVA 1=unprocessed and minimally processed foods. NOVA 2=processed culinary ingredients. NOVA 3=processed foods. NOVA 4=ultra-processed foods.

Significant (p<0·05) before Bonferroni correction.

Significant (p<0·002) after Bonferroni correction, which considered analysis for all cancers and 25 cancer-specific sites.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the caloric proportion of NOVA groups in the total diet and showed a lower number of significant associations than in the main analyses (appendix pp 16–17). Findings were similar when sensitivity analyses for the daily percentage contribution in grams of each NOVA group were performed using upper-bound (appendix pp 20–21) and lower-bound scenarios, as well as excluding patients diagnosed with cancer during the first 2 years of each participant's follow-up (data not shown). The additional adjustment for total water intake also provided similar results (appendix pp 18–19).

Discussion

In this large, multicentre, prospective cohort study, we show that increased consumption of minimally processed and fresh foods were associated with reduced risks of overall cancer and specific cancers, whereas the converse was true for processed and ultra-processed foods. Replacing 10% of processed foods (and for some cancers ultra-processed foods) with an equal amount of minimally processed foods was associated with reduced risks of overall cancer, head and neck cancers, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colon cancer, rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and postmenopausal breast cancer. These results are broadly in line with current evidence, summarised by the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research, showing that increased intake of minimally processed foods, including wholegrains, dairy products, non-starchy vegetables, and coffee, is likely to protect against several cancers.2

Compared with previous studies,16 we found consistent results for the inverse association between minimally processed food consumption and risk of overall cancer and postmenopausal breast cancer. Some inconsistencies between our findings and previous findings16, 17, 18, 19 were observed for some cancer sites—eg, we found a positive association with consumption of processed food and risk of colorectal cancer and postmenopausal breast cancer, whereas other studies did not.16, 17, 18, 19 For breast cancer, a significant positive association had been reported with the consumption of ultra-processed foods in the NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort,16 whereas our analysis in this study did not provide evidence for such association. Our study, using data from the large-scale EPIC cohort, is the largest study investigating these associations between food processing and cancer risk and therefore has greater power to detect differences in populations, potentially explaining why we found overall more significant results for different cancer sites than other cohorts.

Intake of ultra-processed and processed foods might increase cancer risk through obesogenic properties and low nutritional value. Diets rich in ultra-processed foods tend to have a low dietary quality, have a high energy density,3, 4, 5, 7, 26 and be associated with obesity,8, 9, 10, 11 an established risk factor for at least 13 cancer sites, including the head and neck.2, 22 Diets rich in processed foods tend to have an increased energy density,2 as well as a high contribution of alcoholic drinks, which might have partly explained the association between processed foods and cancer risk in this study. When alcoholic drinks were removed from the NOVA classification, the associations between intake of processed food and rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and postmenopausal breast cancer became non-significant, suggesting that drinking alcohol probably drove those associations.

Even when accounting for nutritional profile and BMI (ie, in model 2), processed food intake was associated with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and colon cancer, and ultra-processed food intake was associated with head and neck cancers. Increased intake of processed and ultra-processed foods might additionally increase cancer risk through exposure to chemical contaminants from food packaging with carcinogenic properties, such as di(ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP)27 and bisphenol-A (BPA).28, 29 Other non-nutritional compounds that might be implicated in cancer risk are specific food additives (eg, preservatives) widely used in ultra-processed and processed foods, and cosmetic additives (eg, flavours and emulsifiers) used only in the production of ultra-processed foods.6 Sodium nitrate, for example, is used by manufacturers to preserve processed and ultra-processed meat and poultry. Some studies suggested that this compound might increase cancer risk30 due to formation of nitroso compounds that could yield carcinogenic nitrosamines.31 Additionally, some emulsifiers have been postulated to promote inflammation in the gut,32 a metabolic alteration also potentially associated with the cause of cancer.33 Another concern is the possible effect of artificial sweeteners on cancer risk, which remains controversial.34

Our results using caloric contributions showed a lower number of significant associations than results using contributions in grams. This finding reinforces the relevance of using the percentage contribution in grams as a main exposure since it also considers the effect of non-nutritional compounds on cancer risk, which would not otherwise be captured. The results using contributions in grams remained similar even after further adjusting the models for the total water intake (appendix pp 18–19).

Our study has several strengths including analysis of data from a large-scale prospective cohort, with long-term follow-up and a high number of incident cancer cases. The NOVA coding in EPIC was performed by a team of international nutrition experts on this topic. However, this analysis also has limitations. For example, the NOVA classification was performed on dietary data collected more than 20 years ago (when participants were recruited into EPIC) as a proxy for long-term dietary exposure. Since then, the presence of ultra-processed foods in the marketplace has risen substantially (eg, ready-to-eat meals and packaged snacks).35 In this study, intake of ultra-processed foods contributed to 32% of total daily energy intake, but nowadays it could represent 60% of total daily energy intake in European countries.4 This discrepancy might explain the fewer significant associations observed between ultra-processed foods and cancer risk than in processed foods and cancer risk. However, the sensitivity analysis that classified food products on the basis of the modern food environment (upper-bound scenario) showed similar results (appendix pp 20–21). This similarity between middle-bound and upper-bound scenarios suggests that the population (generation) being studied, that grew up eating less ultra-processed foods than younger generations, might still not consume higher proportions of ultra-processed foods at present. If correct, the estimates in this study might offer a reasonable representation of long-term exposure to ultra-processed foods. However, the effect of the intake of ultra-processed food on cancer risk at present could be higher than the effect shown in this study. Although differences in dietary questionnaires between the EPIC centres could have affected the NOVA classification, models were stratified by centre to control for this issue and the NOVA classification considered differences in food intake between countries. Additionally, NOVA misclassification might have occurred since many assumptions had to be made while classifying the foods according to NOVA groups due to the absence of food processing information in the dietary questionnaires. However, data collected via 24-h dietary recalls in a subsample of individuals in all countries were used to assist assumption choices and minimise misclassification. Covariates included in the study might have also changed over time, such as physical activity, alcohol intake, and smoking, potentially causing residual confounding by these factors. Under-reporting of foods with a high energy density among people with obesity could lead to an underestimation of dietary consumption of ultra-processed foods. Additionally, analyses were performed by large cancer subgroups and in-depth analyses within each subgroup should be performed to further investigate these associations and potential pathways due to the causal heterogeneity within each subgroup. Finally, the exclusion of participants without substantial dietary data at baseline could have potentially led to selection bias.

This study provides additional evidence of the effect of food processing on cancer risk and suggests that substituting processed and ultra-processed food products with minimally processed food might reduce risk for overall cancer, head and neck cancers, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colon cancer, rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and postmenopausal breast cancer. Therefore, recommendations to encourage increased consumption of fresh and minimally processed foods, while reducing the consumption of processed and ultra-processed foods, could be integrated into public health cancer prevention strategies. Future research is needed to replicate these analyses in cohorts with dietary data collected more recently and to explore the mechanistic basis of the observed associations.

Data sharing

Data access can be requested via https://epic.iarc.fr/access/index.php. The request will be assessed by the EPIC working groups and the EPIC Steering Committee. After approval by the EPIC Steering Committee, deidentified data will be made available. An agreement will be signed specifying the study protocol, variables, statistical analysis plan, researchers involved, and length of time that the data will be available.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK (C33493/A29678), World Cancer Research Fund International (IIG_FULL_2020_033), and the Institut National du Cancer (INCa number 2021–138). The coordination of EPIC is financially supported by the IARC and the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, which has additional infrastructure support provided by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. The national cohorts are supported by the Danish Cancer Society (Denmark); Ligue Contre le Cancer, Institut Gustave Roussy, Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM; France); German Cancer Aid, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke (DIfE), Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; Germany); Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro-AIRC–Italy, Compagnia di SanPaolo and National Research Council (Italy); Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), Netherlands Cancer Registry (NKR), LK Research Funds, Dutch Prevention Funds, Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland), World Cancer Research Fund, Statistics Netherlands (Netherlands); Health Research Fund (FIS)—Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Regional Governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia and Navarra, and the Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO; Spain); Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Research Council and County Councils of Skåne and Västerbotten (Sweden); and Cancer Research UK (14136 to EPIC–Norfolk; C8221/A29017 to EPIC–Oxford) and Medical Research Council (1000143 to EPIC–Norfolk; MR/M012190/1 to EPIC–Oxford; UK). Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer or WHO, they are responsible for the views expressed in this Article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer or WHO.

Contributors

FR, RBL, IH, GN, and CC generated the food processing indicators. NK, with assistance from VV, MJG, and IH, did the analyses. NK, VV, MJG, IH, CAM, CM, FR, RBL, EPV, RC, and HF wrote the Article considering the comments and suggestions of the other coauthors. All authors had the opportunity to comment on the analysis and interpretation of the findings and approved the final version for publication. All authors were permitted full access to the data in the study, and NK and IH accessed and verified the data in the study. All authors accept responsibility to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Cancer Research Fund. American Institute for Cancer Research . World Cancer Research Fund International; Washington DC, USA: 2018. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective, a summary of the Third Expert Report. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cediel G, Reyes M, Corvalán C, Levy RB, Uauy R, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods drive to unhealthy diets: evidence from Chile. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:1698–1707. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019004737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rauber F, da Costa Louzada ML, Steele EM, Millett C, Monteiro CA, Levy RB. Ultra-processed food consumption and chronic non-communicable diseases-related dietary nutrient profile in the UK (2008–2014) Nutrients. 2018;10:587. doi: 10.3390/nu10050587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louzada MLDC, Ricardo CZ, Steele EM, Levy RB, Cannon G, Monteiro CA. The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:94–102. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, et al. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22:936–941. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018003762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez Steele E, Popkin BM, Swinburn B, Monteiro CA. The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul Health Metr. 2017;15:6. doi: 10.1186/s12963-017-0119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juul F, Martinez-Steele E, Parekh N, Monteiro CA, Chang VW. Ultra-processed food consumption and excess weight among US adults. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:90–100. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauber F, Chang K, Vamos EP, et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of obesity: a prospective cohort study of UK Biobank. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:2169–2180. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02367-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendonça RD, Pimenta AM, Gea A, et al. Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1433–1440. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.135004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canhada SL, Luft VC, Giatti L, et al. Ultra-processed foods, incident overweight and obesity, and longitudinal changes in weight and waist circumference: the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA–Brasil) Public Health Nutr. 2020;23:1076–1086. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019002854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beslay M, Srour B, Méjean C, et al. Ultra-processed food intake in association with BMI change and risk of overweight and obesity: a prospective analysis of the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. PLoS Med. 2020;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagliai G, Dinu M, Madarena MP, Bonaccio M, Iacoviello L, Sofi F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2021;125:308–318. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520002688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pouzou JG, Costard S, Zagmutt FJ. Probabilistic assessment of dietary exposure to heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from consumption of meats and breads in the United States. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;114:361–374. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman M. Acrylamide: inhibition of formation in processed food and mitigation of toxicity in cells, animals, and humans. Food Funct. 2015;6:1752–1772. doi: 10.1039/c5fo00320b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiolet T, Srour B, Sellem L, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ. 2018;360:k322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Queiroz SA, de Sousa IM, Silva FRM, Lyra CO, Fayh APT. Nutritional and environmental risk factors for breast cancer: a case-control study. Sci Med (Porto Alegre) 2018;28 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solans M, Fernández-Barrés S, Romaguera D, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed food and drinks and chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the MCC-Spain study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romaguera D, Fernández-Barrés S, Gracia-Lavedán E, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and drinks and colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trudeau K, Rousseau MC, Parent MÉ. Extent of food processing and risk of prostate cancer: the PROtEuS study in Montreal, Canada. Nutrients. 2020;12:637. doi: 10.3390/nu12030637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riboli E, Hunt KJ, Slimani N, et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:1113–1124. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body fatness and cancer—viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:794–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:561–565. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skeie G, Mode N, Henningsen M, Borch KB. Validity of self-reported body mass index among middle-aged participants in the Norwegian Women and Cancer study. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:313–323. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S83839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huybrechts I, Rauber F, Nicolas G, et al. Characterisation of the degree of food processing in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition: application of the Nova classification and validation using selected biomarkers of food processing. Front Nutr. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1035580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machado PP, Steele EM, Levy RB, et al. Ultra-processed foods and recommended intake levels of nutrients linked to non-communicable diseases in Australia: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caldwell JC. DEHP: genotoxicity and potential carcinogenic mechanisms—a review. Mutat Res. 2012;751:82–157. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seachrist DD, Bonk KW, Ho SM, Prins GS, Soto AM, Keri RA. A review of the carcinogenic potential of bisphenol A. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;59:167–182. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emfietzoglou R, Spyrou N, Mantzoros CS, Dalamaga M. Could the endocrine disruptor bisphenol-A be implicated in the pathogenesis of oral and oropharyngeal cancer? Metabolic considerations and future directions. Metabolism. 2019;91:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldman R, Shields PG. Food mutagens. J Nutr. 2003;133(suppl 3):965S–973S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.965S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sindelar JJ, Milkowski AL. Sodium nitrite in processed meat and poultry meats: a review of curing and examining the risk or benefit of its use. 2011. https://meatscience.org/publications-resources/white-papers/docs/default-source/publications-resources/white-papers/2011-11-amsa-nitrite-white-paper

- 32.Viennois E, Bretin A, Dubé PE, et al. Dietary emulsifiers directly impact adherent-invasive E coli gene expression to drive chronic intestinal inflammation. Cell Rep. 2020;33 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viennois E, Merlin D, Gewirtz AT, Chassaing B. Dietary emulsifier-induced low-grade inflammation promotes colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2017;77:27–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soffritti M, Padovani M, Tibaldi E, Falcioni L, Manservisi F, Belpoggi F. The carcinogenic effects of aspartame: the urgent need for regulatory re-evaluation. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57:383–397. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vandevijvere S, Jaacks LM, Monteiro CA, et al. Global trends in ultraprocessed food and drink product sales and their association with adult body mass index trajectories. Obes Rev. 2019;20(suppl 2):10–19. doi: 10.1111/obr.12860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data access can be requested via https://epic.iarc.fr/access/index.php. The request will be assessed by the EPIC working groups and the EPIC Steering Committee. After approval by the EPIC Steering Committee, deidentified data will be made available. An agreement will be signed specifying the study protocol, variables, statistical analysis plan, researchers involved, and length of time that the data will be available.