Abstract

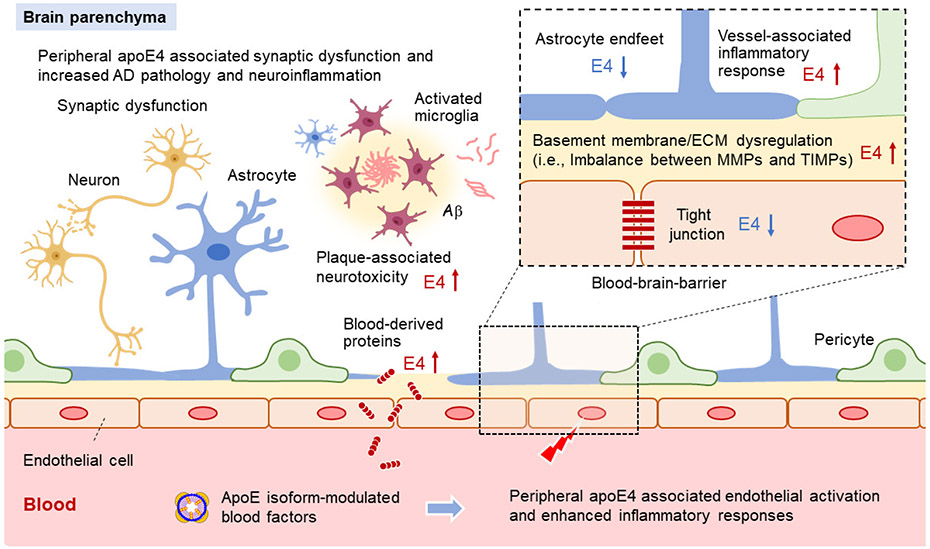

The apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) gene, a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is abundantly expressed in both the brain and periphery. Here, we present evidence that peripheral apoE isoforms, separated from those in the brain by the blood-brain barrier (BBB), differentially impact AD pathogenesis and cognition. To evaluate the function of peripheral apoE, we developed conditional mouse models expressing human APOE3 or APOE4 in the liver with no detectable apoE in the brain. Liver-expressed apoE4 compromised synaptic plasticity and cognition by impairing cerebrovascular functions. Plasma proteome profiling revealed apoE isoform-dependent functional pathways highlighting cell adhesion, lipoprotein metabolism, and complement activation. ApoE3 plasma from young mice improved cognition and reduced vessel-associated gliosis when transfused into aged mice, whereas apoE4 compromised the beneficial effects of young plasma. A human iPSC-derived endothelial cell model recapitulated the plasma apoE isoform-specific effect on endothelial integrity, further supporting a vascular-related mechanism. Upon breeding with amyloid model mice, liver-expressed apoE4 exacerbated brain amyloid pathology, whereas apoE3 reduced it. Our findings demonstrate pathogenic effects of peripheral apoE4, providing a strong rationale for targeting peripheral apoE to treat AD.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease and the leading cause of dementia in the elderly population. The accumulation and deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) in the brain are central events in AD pathogenesis1. Epidemiological studies showed that vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis have significant impacts on AD risk2,3. Cerebrovascular dysfunction, including blood-brain barrier (BBB) leakage and impaired cerebral microcirculation, is tightly linked to neuronal dysfunction4-6. While genetic and environmental factors influence AD pathogenesis, the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene dramatically increases the risk and lowers the age at onset of AD in a gene dose-dependent manner7. The APOE4 also accelerates aging-related cognitive decline in non-demented individuals8. Compared to the common APOE3 or the AD-protective APOE2 allele, APOE4 drives earlier and more abundant Aβ pathology, a major driver in AD pathogenesis9,10. APOE4 also regulates non-Aβ pathways such as vascular function, immune responses, and tau-mediated neurodegeneration11-13. A better understanding on how apoE isoforms impact brain functions and AD-related pathways should allow us to address why apoE4 increases AD risk and how we can target this protein for therapy14.

ApoE is produced primarily by astrocytes in the central nervous system (CNS) and serves as a major lipid carrier to neurons to support membrane homeostasis, synaptic integrity, and injury repair in the brain11. In the periphery, apoE is abundantly produced by the liver and macrophages, released into the blood to modulate lipid-related events. Importantly, peripheral apoE is separated from that in the CNS by the BBB, most evident in a liver transplantation study showing that apoE isoform status in the recipient’s plasma was changed to the donor’s genotype while it remained the same in the CSF15. Despite physical separation, several lines of evidence suggest that peripheral apoE might impact cerebrovascular and brain functions16,17. ApoE4 is a risk factor for hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis, conditions known to increase AD risk18. ApoE4 can also synergize with other risk factors including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and peripheral vascular diseases19, exerting confounding effects on AD. However, due to the presence of apoE in both the periphery and the brain, it has been difficult to assess the specific contribution of peripheral apoE isoforms to CNS functions and AD pathogenesis. To meet this challenge, we developed mouse models that conditionally express human APOE3 or APOE4 in the liver with no detectable apoE in the brain. Importantly, we found that liver-expressed apoE4 compromised synaptic plasticity and cognitive behaviors likely by impairing cerebrovascular functions. With single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq), we showed that expression of apoE4 in the periphery promotes immune responses in endothelial cells along with an increase of vessel-associated gliosis, which may compromise barrier integrity and cerebrovascular functions. We also explored the therapeutic potential of peripheral treatment using young plasma with different APOE genotypes. We demonstrated that apoE3, but not apoE4 young plasma improved cognition and reduced vessel-associated gliosis in aged mice. In addition, liver-expressed apoE4 exacerbated brain amyloid pathology, whereas liver-expressed apoE3 led to beneficial effects on brain functions and ameliorated amyloid deposition. Our findings demonstrate differential effects of peripheral apoE isoforms on brain function and pathological outcomes.

RESULTS

Peripheral apoE isoforms differentially impact brain function

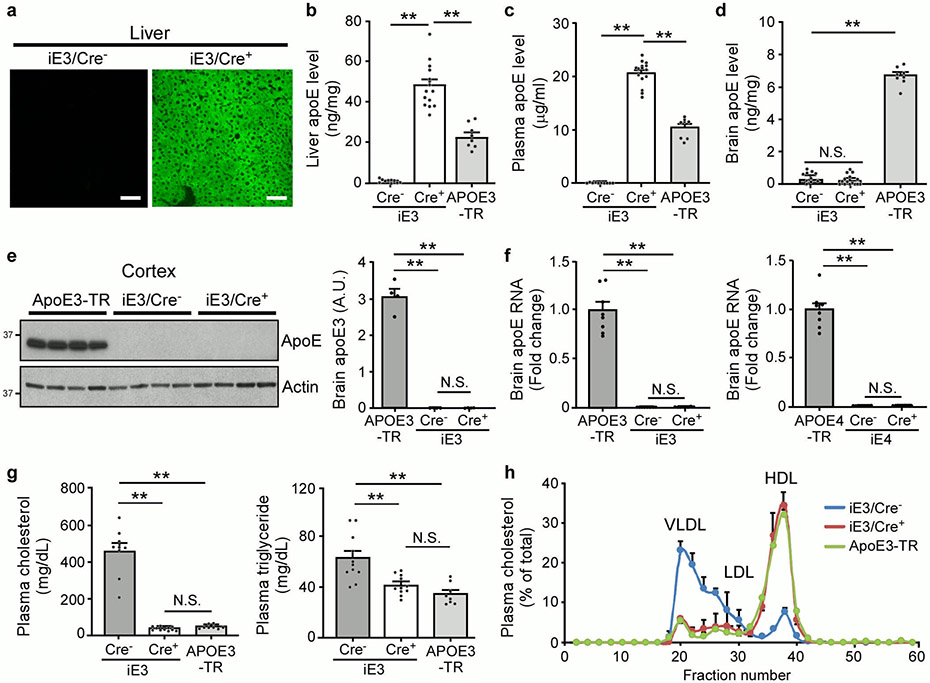

We developed animal models that allow for cell type-specific and inducible expression of apoE3 or apoE4 (termed iE3 and iE4 mice where “i” represents inducible) (Fig. 1a)20. After breeding with liver-specific albumin-Cre (Alb-Cre) mice, we generated mice expressing human apoE3 or apoE4 in the liver in an Apoe knockout (apoe-KO) background, allowing us to specifically address the effect of peripheral apoE on brain function. Further, comparison with apoe-KO littermate controls should provide clues as to whether liver-expressed apoE4 exhibits a gain-of-toxic function or a loss-of-protective function. As anticipated, a strong GFP fluorescence, a surrogate of apoE expression, was observed exclusively in the liver of iE3/Cre+ and iE4/Cre+ mice but not in other tissues or in Cre− mice (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Both apoE3 and apoE4 were expressed in the liver and secreted into the bloodstream in Alb-Cre+ mice with concentrations ~1.5-2 fold higher than those in apoE-targeted replacement (apoE-TR) (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1b, c). Importantly, apoE was undetectable in the mouse brains (Fig. 1d, e and Extended Data Fig. 1d-f). The presence of apoE in the plasma of iE3/Cre+ or iE4/Cre+ mice rescued hypercholesterolemia, elevated triglyceride, and altered plasma lipoprotein profiles in Cre− (apoe-KO) mice to the extent comparable to those in apoE-TR mice (Fig. 1f, g and Extended Data Fig. 1g, h).

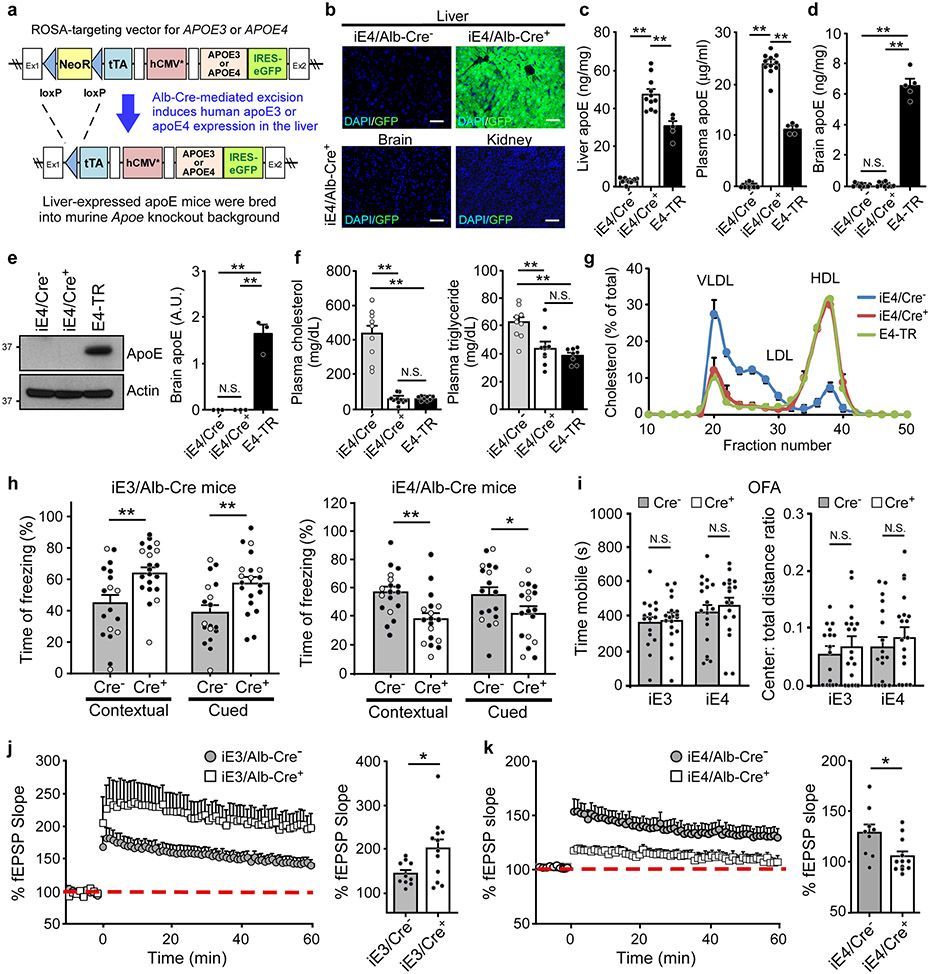

Fig. 1 ∣. Opposing effects of liver-expressed apoE3 and apoE4 on brain cognition and synaptic function.

a, The structure of the ROSA-targeting vector with the Tet-off regulatory cassette for APOE and eGFP expression. Breeding to Alb-Cre mice removed the loxP-flanked Neor gene and led to expression of human apoE3 or apoE4 in the liver. b, GFP was exclusively detected in the liver of iE4/Cre+ mice. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. Scale bar, 50 μm. c, d, ApoE levels in the liver, plasma, or brain of iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=11; Cre+, n=11) and apoE4-TR mice (n=5) at 12-13 months of age were examined by ELISA. **, P<0.0001. e, No apoE was detected in the brains of iE4/Cre mice (n=3/group) at 12-13 months of age by Western blotting. **, P=0.0002. f, Total cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the plasma of iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=9; Cre+, n=10) and apoE4-TR mice (n=8) were examined. Cholesterol: **, P<0.0001; Triglyceride: **, P=0.003 (Cre− vs. Cre+); P=0.0004. g, Distribution of plasma lipoprotein cholesterol in iE4/Cre− or iE4/Cre+ mice (n=3/group). Pooled plasma from apoE4-TR mice (n=3) was included as controls. N.S., not significant. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc test. h, Memory performance of mice expressing apoE3 (Cre−, n=18; Cre+, n=21 for contextual test; **, P=0.003; Cre−, n=18; Cre+, n=20 for cued test; **, P=0.005) or apoE4 (Cre−, n=18; Cre+, n=18; **, P=0.003; *, P=0.048) in the liver examined by fear conditioning tests. The percentage of time spent showing freezing behavior in response to stimulus is shown. Black circle: male; Grey circle: female. i, Analyses of anxiety-related behaviors in iE3/Cre (Cre−, n=16; Cre+, n=19) and iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=18; Cre+, n=18) assessed by open field analysis (OFA). N.S., not significant. j, k, Normalized fEPSP responses to field stimulation were summarized during recordings from the CA1 region of hippocampal slices from iE3/Cre mice (Cre−, n=10; Cre+, n=12) or iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=9; Cre+, n=12). Averages of the last 5 min of fEPSP recording were quantified. Data represent mean ± s.e.m.; iE3: *, P=0.03; iE4: *, P=0.018, two-tailed Student's t-test.

To examine how peripheral expression of apoE3 or apoE4 impacts brain function, we performed behavioral and electrophysiology studies. Importantly, we found that apoE4 expression in the liver resulted in significant memory deficits in iE4/Cre+ mice compared to controls as assessed by contextual and cued fear conditioning tests, whereas apoE3 expression improved associative memory (Fig. 1h). The anxiety behaviors, locomotor activity, and motor coordination were not affected by apoE3 or apoE4 expression in the liver (Fig. 1i, and Supplementary Fig. 1). Consistently, peripheral apoE4 significantly suppressed synaptic plasticity measured by long-term potentiation (LTP); in contrast, peripheral apoE3 increased it (Fig. 1j, k). These results indicate that peripheral apoE3 has a beneficial effect, whereas peripheral apoE4 exhibits a gain-of-toxic effect, impairing brain function in the absence of brain apoE.

Peripheral apoE4 impairs cerebrovascular functions

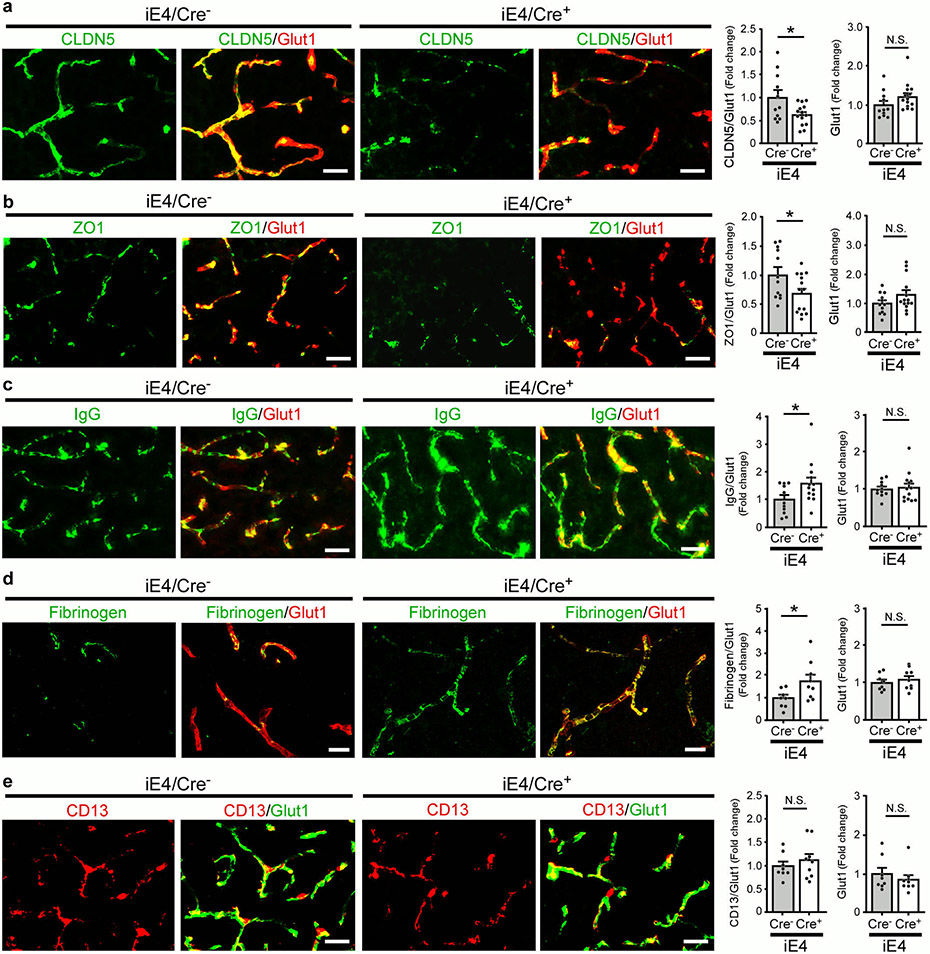

Cerebral hypoperfusion and BBB dysfunction have been implicated in AD pathogenesis5. To explore the potential pathological mechanisms by which liver-expressed apoE4 disrupts brain functions, we investigated the cerebrovascular permeability of mice at 6-7 months of age. Remarkably, an increase in BBB leakage in iE4/Cre+ mice was observed compared to iE4/Cre− mice measured by in vivo two-photon microscopy (Fig. 2a, b), consistent with previous finding in apoE4-TR mice12. We further examined the BBB integrity in mice at 12-13 months of age by analyzing the tight junction (TJ)-associated proteins claudin-5 (CLDN5), and scaffold protein zonula occludens 1 (ZO1) in endothelial cells. Immunostaining demonstrated that the levels of CLDN5 and ZO1 normalized by the vascular marker Glut1 were both reduced in iE4/Cre+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). Upon BBB disruption, blood components and coagulation factors are shown to gain access to the brain12,21. To further assess if peripheral apoE4 impacts the brain vascular permeability, we examined the leakage of serum proteins to the brain by immunostaining for albumin (67 kDa), immunoglobulin G (IgG; 150 kDa) or fibrinogen (340 kDa), robust markers of impaired BBB integrity. An increased level of albumin in some perivascular areas and brain parenchymal regions near vessels was observed in iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 2c). In addition, an elevation of perivascular deposits of IgG was found in iE4/Cre+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 2c). The iE4/Cre+ mice also exhibited an increase of fibrinogen immunoreactivity although mostly confined to vessels (Extended Data Fig. 2d). These results suggest that the chronic BBB leakage might be selective according to the size of the molecules. As pericytes regulate the BBB integrity, we also assessed the CD13-positive pericyte coverage on the brain microvessels and found no differences between iE4/Cre+ and iE4/Cre− mice (Extended Data Fig. 2e).

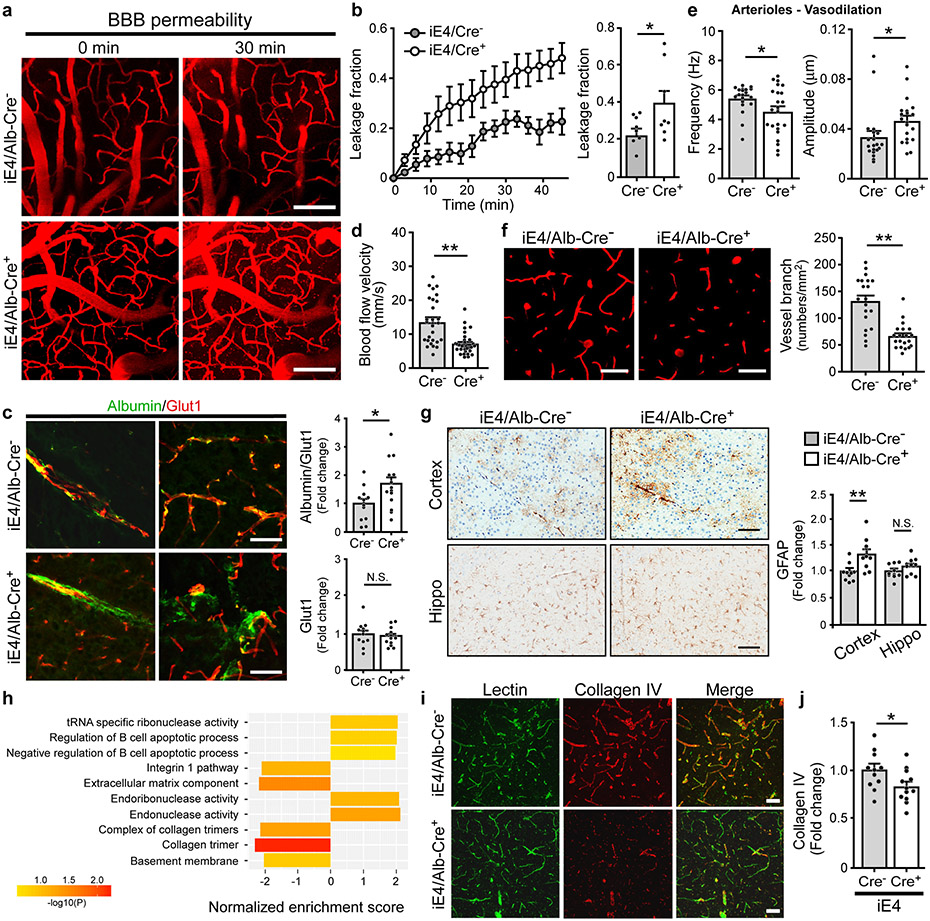

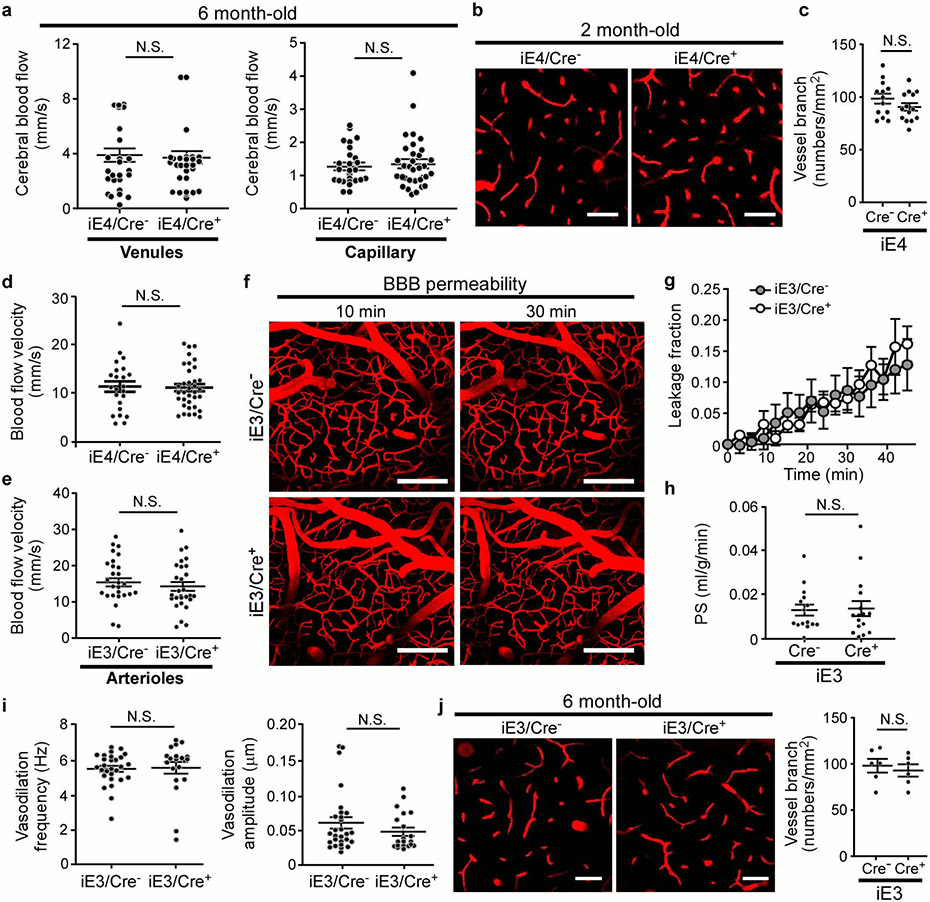

Fig. 2 ∣. Compromised cerebrovascular integrity and astrogliosis associated with liver-specific expression of apoE4.

a-e, Two-photon imaging was used to assess vascular functions in male iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=5; Cre+, n=5) at 6-7 months of age. b, d-f, In two-photon analyses, each data point represents blood vessel-related observation with varying number of measurements in each animal from 5 mice per genotype. a, The representative images at 0 and 30 mins after dextran injection are shown. Scale bar, 100 μm. b, The leakage of dextran signals were monitored over time (left panel). The fraction of BBB leakage at 30 min after injection of dextran was quantified (right panel). *, P=0.045. c, Brain sections from iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=12; Cre+, n=14) at 12-13 months of age were immunostained with albumin and Glut1 antibodies. The total Glut1 (red) and the albumin (green) normalized against Glut1 were quantified. Scale bar, 50 μm. *, P=0.024. d, The cerebral blood flow (CBF) in the cerebral arterioles of iE4/Cre mice at 6-7 months of age was measured. **, P<0.0001. e, The frequency and amplitude of arteriolar oscillation in iE4/Cre mice were measured. The data points represent the measurements for frequency (*, P=0.042) or amplitude (*, P=0.045) of arteriolar oscillation in each vessel from 5 mice/genotype. f, The vessel branch densities in the cerebral arterioles of iE4/Cre mice were examined. **, P<0.0001. Scale bar, 50 μm. g, Brain sections from iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=10; Cre+, n=10) at 12-13 months of age were immunostained with a GFAP antibody and quantified. **, P=0.005. Scale bar, 50 μm. h, Brain tissues from iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=8; Cre+, n=8) were subjected to RNA Sequencing. Top gene ontology and canonical pathways enriched for differential expression signals between Cre− and Cre+ mice were identified by GSEA. Minus sign for down-regulation; Positive sign for up-regulation. i, Collagen IV-positive (Red) basement membrane and lectin-positive endothelium (Green) in the cortex of iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=3; Cre+, n=4). Scale bar, 50 μm. j, Collagen IV levels in iE4/Cre mice (Cre−, n=11; Cre+, n=12) examined by ELISA. *, P=0.045. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. N.S., not significant, two-tailed Student's t-test.

To examine how apoE isoforms affect vascular functions, we next measured the cerebral blood flow (CBF) velocity in the cortical arterioles, capillaries, and venules in mice at 6-7 months of age by two-photon imaging (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, the expression of apoE4 in the liver dramatically suppressed CBF in the arterioles but not in the venules or capillaries (Fig. 2d; Extended Data Fig. 3a). Vascular tone dysregulation has been shown to cause reduced cerebrovascular reactivity and regional hypoperfusion, which can further promote brain Aβ accumulation5. We thus measured the oscillation of cerebral vessel tone by two-photon imaging. Importantly, we found that iE4/Cre+ mice exhibited a lower frequency but higher amplitude in vasodilation in the cerebral arterioles (Fig. 2e), which may contribute to reduced arterial CBF and impaired autoregulation. In addition, a significant reduction in the number of vessel branches was observed in iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 2f). No alteration was observed in vessel branch density and CBF of iE4/Cre+ mice at 2 months of age (Extended Data Fig. 3b-d), indicating that such change was not due to developmental defects. In contrast, we did not observe differences in the BBB permeability, CBF, or arteriolar oscillation in iE3/Cre+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 3e-j). Together, these results demonstrate that apoE4 expression in the periphery negatively impacts brain function likely by impairing cerebrovascular integrity and functions.

We next examined the impacts of peripheral apoE expression on synaptic integrity and neuroinflammation. No significant changes in the PSD-95 and synaptophysin levels were detected in the brains of experimental mice (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The GFAP-positive astrogliosis was significantly increased in the iE4/Cre+ mice, whereas it was decreased in iE3/Cre+ mice (Fig. 2g; Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Interestingly, Iba1-positive microgliosis was significantly reduced in iE3/Cre+ but not in iE4/Cre+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). Furthermore, the increased gliosis in iE4/Cre+ mice was most prominent in regions proximal to cerebral vessels shown by co-immunostaining for astrocytes (anti-GFAP), microglia (anti-Iba1) or perivascular macrophages (anti-CD206) (Supplementary Fig. 4). These results suggest that expression of apoE4 in the periphery promotes BBB dysfunction and vessel-associated gliosis.

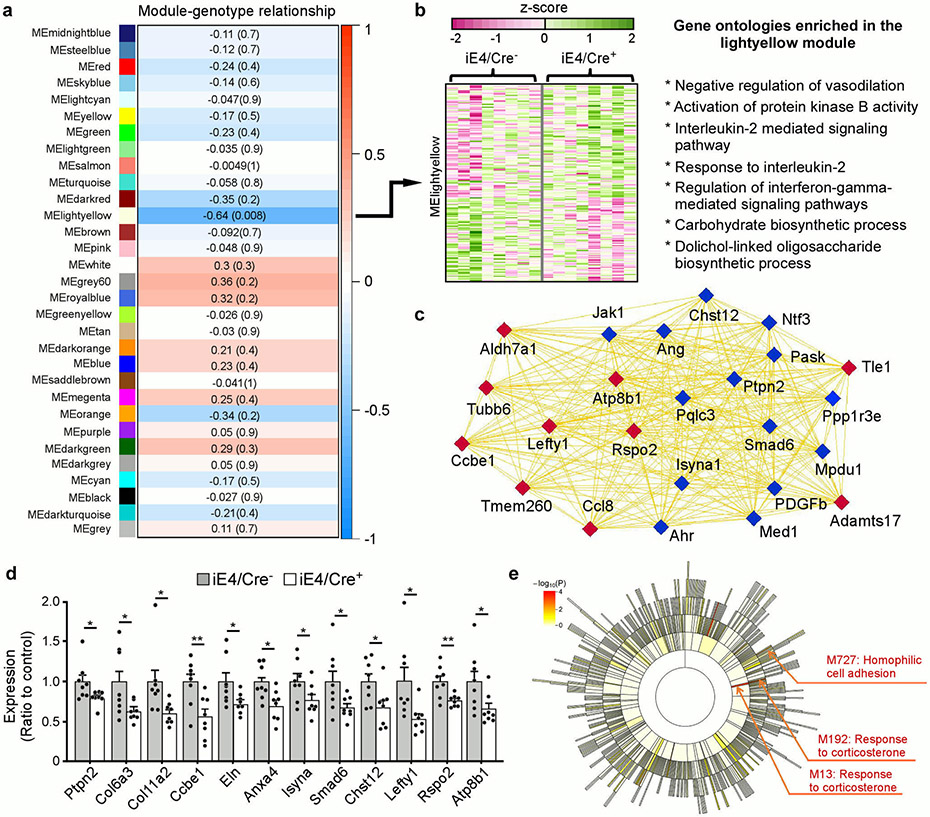

Effects of peripheral apoE isoforms on brain transcriptomic signatures

To further address the molecular mechanisms by which liver-expressed apoE affects brain functions, we performed RNA-Seq analysis to profile the transcriptional changes in mouse brains. Weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA) showed that the cyan module has a significant positive correlation with peripheral apoE3 expression in which multiple pathways including WAVE/SCAR actin nucleation complex, cell-cell adhesion, and galactose metabolism were enriched (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Specifically, peripheral apoE3 expression was associated with the regulation of Pcdha gene clusters (Supplementary Fig. 5c), encoding a family of cell surface proteins that play pivotal roles in synaptic connections, learning, and memory22. More importantly, WGCNA revealed a critical association of peripheral apoE4 expression with the regulation of vasodilation, cell survival, and energy homeostasis (Extended Data Fig. 4a, b). The light yellow module (MElightyellow) which contained multiple genes important for vascular endothelial cell functions and BBB integrity (e.g., Ang, Ptpn-2, Pdgfb and Ahr)23-25 was found to be down-regulated in iE4/Cre+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 4c, d). Notably, Atp8b1, a hub gene in the module, encodes a BBB microvessel-enriched protein that mediates lipid metabolism. These results suggest that peripheral expression of apoE4 may impact brain vascular functions by affecting endothelial integrity. Interestingly, MElightyellow also contained genes linked to carbohydrate biosynthetic and metabolic processes (e.g., Mpdu1 Chst12, Isyna1, Pask, Aldh7a1), implying that dysregulation of cerebrovascular functions may disrupt energy homeostasis in the brain. To further identify coordinated changes at the pathway and network levels, we performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)26 to screen for “enriched” gene ontology (GO) terms. The B-cell apoptotic process and endonuclease activity, which may be related to the regulation of immune responses and tissue/vascular remodeling, were up-regulated, whereas extracellular matrix component (ECM), basement membranes (BMs), collagens and integrin pathways were down-regulated in the brain of iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 2h). In particular, the expression of collagen family members (e.g., Col6a3, Col11a2) and elastin, the dominant ECM components in the arterial wall regulating blood flow, were down-regulated in iE4/Cre+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Moreover, we observed that collagen IV, a major component of the BMs, was more fragmented and reduced in iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 2i, j). Since endothelial and parenchymal cells secrete ECM proteins to generate and maintain the BMs, which directly regulate barrier integrity27, these observations together support that peripheral apoE4 negatively impacts brain functions by impairing BBB integrity.

Furthermore, we employed multiscale embedded gene co-expression network analysis (MEGENA)28 to explicitly build up gene co-expression networks from the RNA-Seq data to analyze how components of different pathways interact. Importantly, we found that the MEGENA modules related to hemophilic cell adhesion and responses to corticosterone were significantly up-regulated in iE4/Cre+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 4e), suggesting that increased neuroinflammation by peripheral apoE4 might contribute to vascular remodeling, conditioning the brain to be more susceptible to stress29,30.

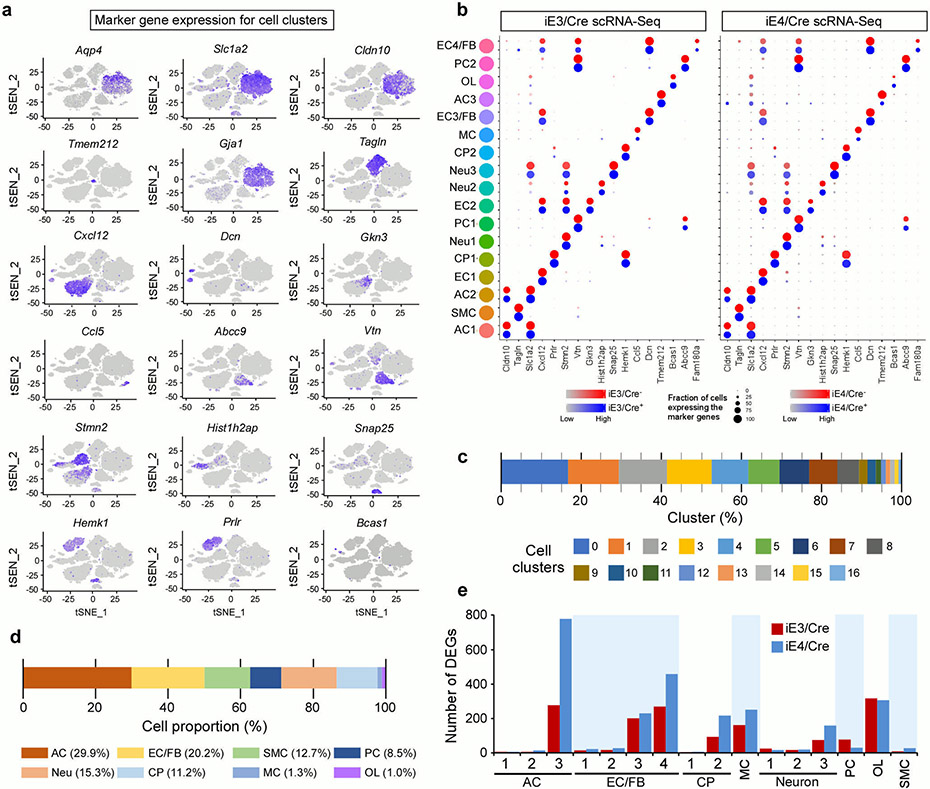

Peripheral apoE4 promotes immune responses in the endothelial cells and increases vessel-associated gliosis

To further examine how liver-expressed apoE isoforms impact the transcriptomic changes within the glio-vascular unit, we performed single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) on vascular cell-enriched cell population isolated from the brains of iE3/Cre and iE4/Cre mice (Fig. 3a). We first performed canonical correlation analysis of all four groups (i.e., iE3/Cre−, iE3/Cre+, iE4/Cre− and iE4/Cre+ mice) to identify common sources of variation, followed by integration analysis to identify cell clusters and conserved cell type markers (Extended Data Fig. 5a)32-34. The same cell clusters were identified in all four groups in which conserved cell markers were observed (Extended Data Fig. 5b). In total, seventeen cell clusters were identified, including astrocytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, pericytes, choroid plexus cells, neurons, oligodendrocytes, and myeloid cells (Fig. 3b; Extended Data Fig. 5c, d). We found that astrocyte, endothelial cell, and oligodendrocyte clusters had the most differentially expressed genes (DEGs), in particular the astrocyte cluster 3 (AC3) and endothelial cell clusters 3 and 4 (EC3 and EC4) (Extended Data Fig. 5e). EC3 and EC4, which are responsive to the peripheral apoE isoform expression, contained genes such as Icam1, Vcam1, Nr2f2, Cgnl1, Mgp, and decorin (Dcn), the latter is an ECM proteoglycan produced by endothelial cells in inflammation-associated angiogenesis32. As Dcn is expressed by stressed vascular endothelial cells as well as fibroblasts (FB), these two cell clusters were termed EC3/FB and EC4/FB.

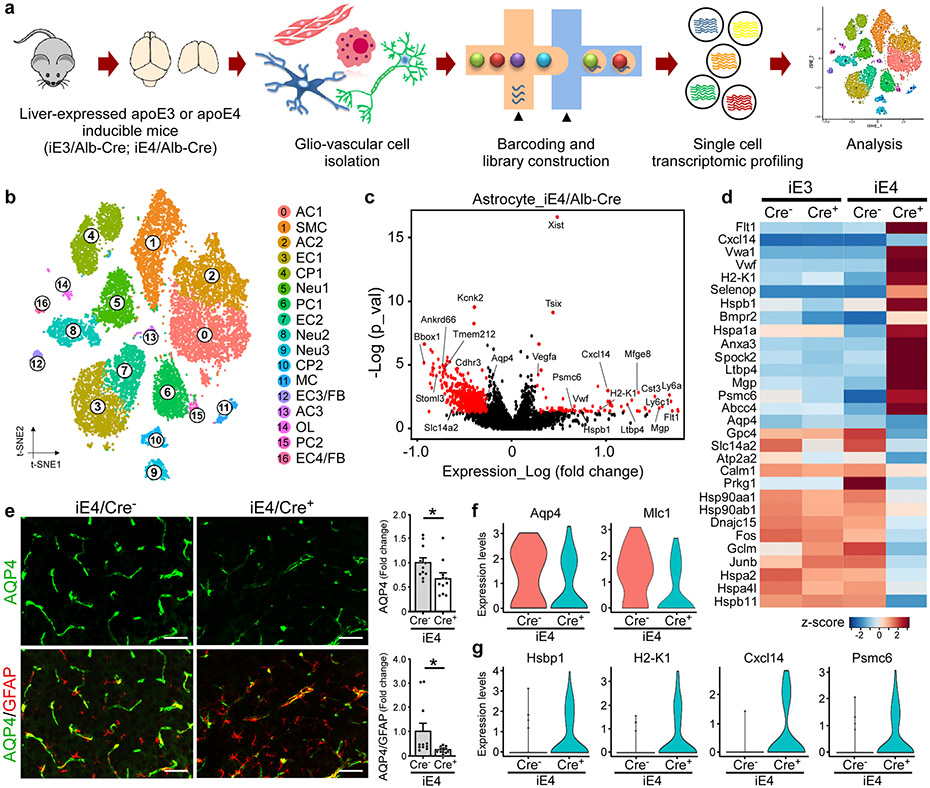

Fig. 3 ∣. Vascular enriched scRNA-Seq reveals reduced astrocytic endfeet and increased immune responses associated with liver-specific expression of apoE4.

Brain cortical tissues from iE3/Cre and iE4/Cre mice (n=4/genotype) at 12-13 months of age were subjected to vascular and glial cell-enriched single cell RNA-Sequencing (scRNA-Seq). a, Diagram showing an overview of the scRNA-seq experiment. b, The t-SNE plot showing the clusters of single cell events captured in scRNA-seq. c, Volcano plot depicting up- and down-regulated genes in astrocytic cell populations (AC1, AC2, AC3) in iE4/Cre+ mice compared to iE4/Cre− control mice. Genes significant at the P value ≤ 0.05 and fold change ≥ 1.2 are denoted red in color. d, Heatmap revealing the scaled expression of differentially expressed genes in astrocytes from iE3/Cre and iE4/Cre mice. e, Brain sections from iE4/Cre− or iE4/Cre+ mice (Cre−, n=11; Cre+, n=11) at 12-13 months of age were immunostained with anti-AQP4 (green) and anti-GFAP (red) antibodies. The AQP4 immunoreactivity with or without normalization to GFAP signal was quantified. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. AQP4: *, P = 0.036; AQP4/GFAP: *, P = 0.038, two-tailed Student's t-test. f, g, Violin plots showing the mean and variance differences between iE4/Cre− and iE4/Cre+ astrocytes for genes regulating astrocyte endfeet (Aqp4 and Mlc1), innate immune response (H2-K1, Cxcl14 and Psmc6), and hypoxia/stress responses (Hsbp1).

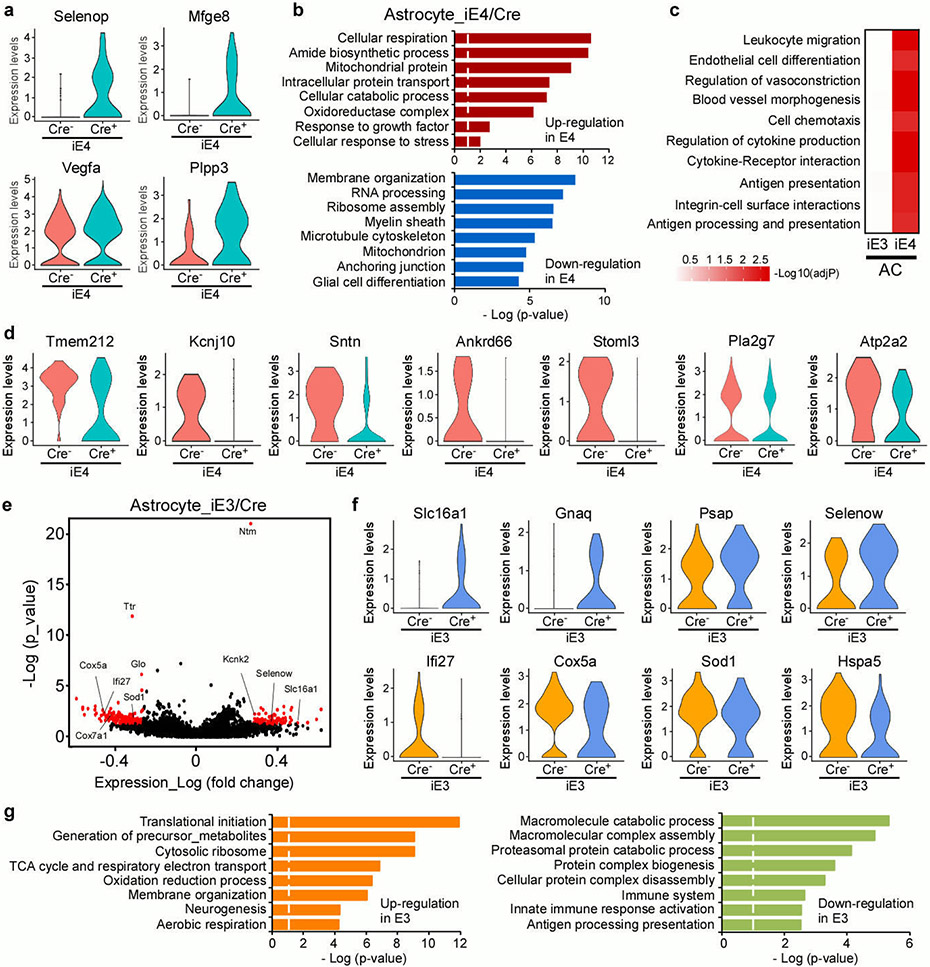

In the astrocyte clusters from iE4/Cre+ mice, we observed an up-regulation of genes involved in innate immunity (Cxcl14, Cst3, Ly6c1, Ly6a), antigen-processing (H2-K1, Psmc6), VEGF signaling (Vegfα, Flt1), matrix remodeling and migration (Vwa1, Mgp, Spock2), oxidative stress (Hspb1, Selenop), and TGF-β signaling (Bmpr2, Ltbp4) (Fig. 3c, d, f, g; Extended Data Fig. 6a). Genes involved in synapse modifying function (Gpc4), energy homeostasis (Atp2a2, Slc1a4), and astrocyte endfeet (Aqp4) were down-regulated (Fig. 3f). GO term enrichment and GSEA analyses revealed common perturbed pathways in iE4 astrocyte clusters, including anchoring junction, regulation of vasoconstriction, cytokine-receptor interaction, and leukocyte migration (Extended Data Fig. 6b, c). Importantly, multiple genes previously identified in astrocyte endfeet transcriptomes (e.g., Aqp4, Tmem212, Mlc1, Kcnj10, Stoml3, Ankrd66, and Sntn) were down-regulated in the iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 3f; Extended Data Fig. 6d). As a robust association between astrocytic endfeet and the vasculature is vital for the BBB integrity, we performed immunostaining for marker of astrocyte endfeet, AQP4, and confirmed the reduction of AQP4 in iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 3e). Together, these findings indicate that peripheral apoE4 expression leads to transcriptional changes of genes involved in perivascular astrocyte endfeet and inflammatory responses within glio-vascular unit. Interestingly, peripheral apoE3 expression regulated transcriptomic alterations in energy homeostasis, cellular metabolism, and brain immune response-related genes in astrocytes (Extended Data Fig. 6e-g).

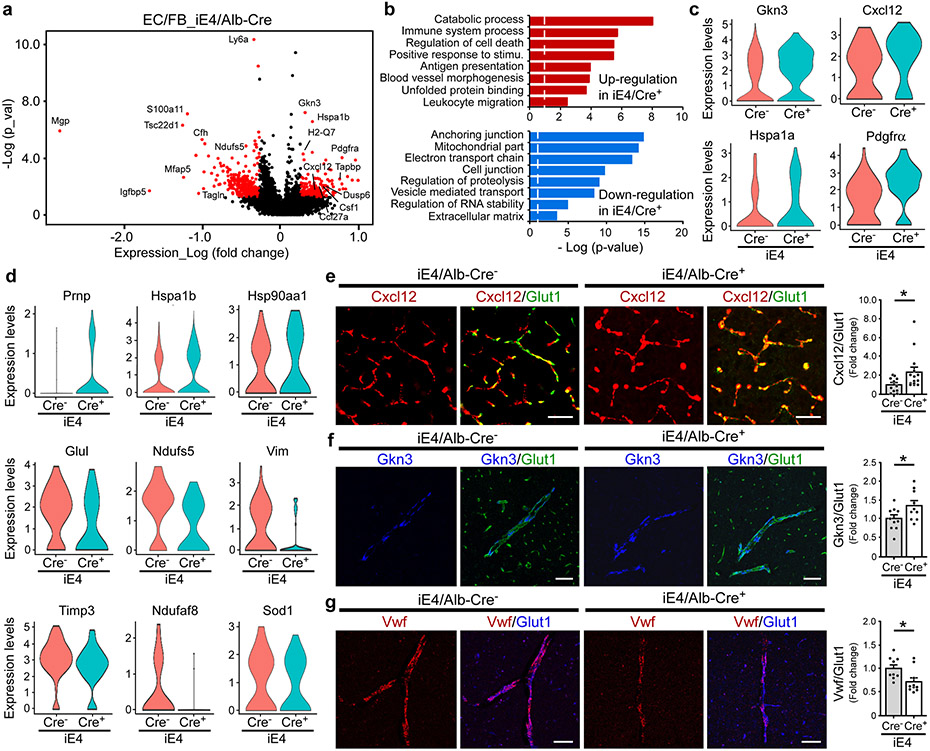

A recent study showed that brain endothelial cells can sense and relay signals between the blood and the brain34. The scRNA-Seq analysis showed that genes involved in IGF signaling (Csnk2a1, Ptpn11), tight junction formation (Vcl, Tcf7l2, Prkacb), actin cytoskeleton signaling (Arpc1b, Rhob), and maintenance of endothelial barrier function (Fgfbp1, Vasp) were up-regulated in the endothelial cells of iE3/Cre+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Major pathways modulated by apoE3 expression included cell junction, basement membrane, translational initiation, immune system processes, and cell death. (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Notably, genes mediating immune response (Ccl27a, Dusp1, Gkn3, Csf-1, Cxcl12), antigen presentation (H2-Q7, H2-T23, Tapbp), cell proliferation (Pdgfrα), and hypoxia/stress response (Hspa1a, Hspa1b, Hsp90aa1) were up-regulated in the endothelial cells of iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 4a, c, d). GO term enrichment analysis indicated that pathways involved in immune processes, antigen processing and presentation, unfolded protein binding, and leukocyte migration pathways were up-regulated, whereas pathways associated with anchoring junction, mitochondrial function, and extracellular matrix were down-regulated in the endothelial cells of iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 4b). Cxcl12 is a critical chemoattractant induced by hypoxia and contributes to the regulation of immune responses in the CNS35. Vwf was shown to play an important role in regulating BBB permeability in response to peripheral inflammatory stimuli36. Using immunostaining, we confirmed that Cxcl12 was up-regulated in the vessels of iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 4e). In addition, we examined the expression of Gkn3 and Vwf by in situ hybridization along with immunostaining for Glut1. We validated that Gkn3 was up-regulated, whereas Vwf was down-regulated in the vessel of iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 4f, g). Together, our data suggest that apoE4 in the periphery promotes immune responses in the brain endothelial cells along with an increase of vessel-associated gliosis, which potentially compromises barrier integrity and cerebrovascular functions.

Fig. 4 ∣. Transcriptional signatures in brain endothelial cells associated with liver-specific expression of apoE4.

a, Volcano plots illustrating up- or down-regulated genes in the endothelial cell populations (EC1, EC2, EC3/FB, EC4/FB) from iE4/Cre mice (Cre+ vs. Cre−). Genes significant at the P value ≤ 0.05 and fold change ≥ 1.2 are denoted red in color. b, Gene ontology analyses for up- or down-regulated genes in the endothelial cell populations of the iE4/Cre mice c, d, Violin plots showing the mean and variance difference between iE4/Cre− and iE4/Cre+ endothelial cells for genes regulating inflammatory response (Cxcl12 and Gkn3), cell proliferation (Pdgfrα), lactate homeostasis (Glu1), mitochondrial function (Ndufs5 and Ndufaf8), matrix assembly (Vim), oxidative stress (Prnp), regulators of MMP family (Timp3), and hypoxia/stress response (Sod1, Hspa1a, Hspa1b, and Hsp90aa1). e, Brain sections from iE4/Cre− or iE4/Cre+ mice (Cre−, n=11; Cre+, n=14) at 12-13 months of age were subjected to co-immunostaining for Cxcl12 (red) and Glut1 (green), and the Cxcl12/Glut1 signals were quantified. *, P = 0.036, two-tailed Student's t-test. Scale bar, 50 μm. f, Brain sections from the iE4/Cre− or iE4/Cre+ mice (Cre−, n=10; Cre+, n=10) at 12-13 months of age were subjected to RNAScope assay for Gkn3 (blue) and co-immunostaining for Glut1 (green). The Gkn3/Glut1 signal was quantified. *, P = 0.039. Scale bar, 50 μm. g, Brain sections from iE4/Cre− or iE4/Cre+ mice (Cre−, n=9; Cre+, n=10) at 12-13 months of age were subjected to RNAScope analysis for Vwf (red) and co-immunostaining for Glut1 (blue). The Vwf/Glut1 signal was quantified. *, P = 0.024. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data represent mean ± s.e.m.

Peripheral expression of apoE isoforms alters plasma proteomes

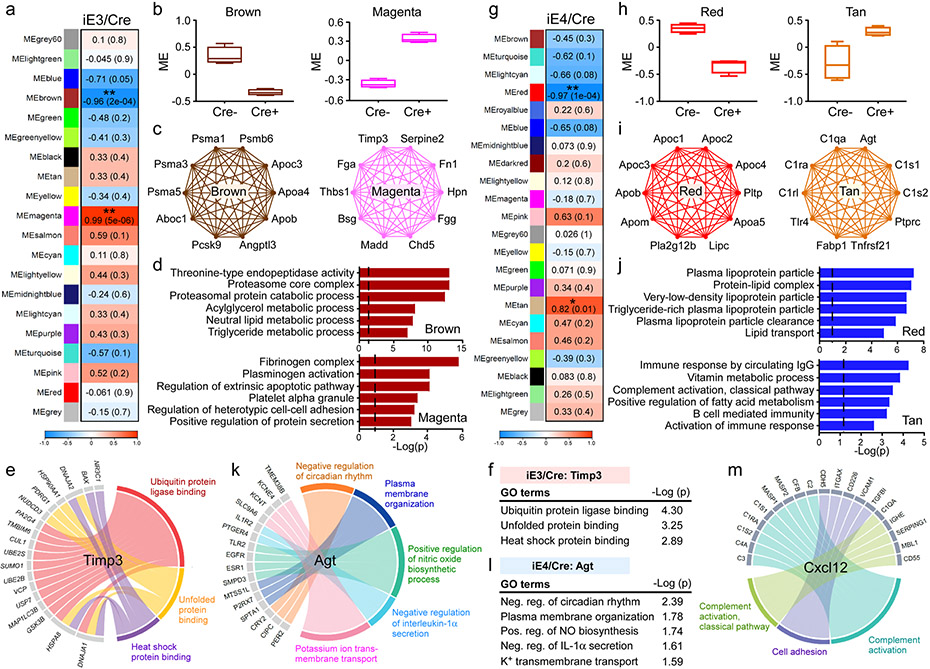

To identify potential blood factors mediating the apoE isoform effects on cerebrovasculature and brain function, we performed unbiased proteomic analysis of the plasma from iE3/Cre and iE4/Cre mice (Supplementary Table 1). With WGCNA analysis, we identified 20 co-expression modules, among which two were significantly associated with apoE3 plasma (Fig. 5a). Specifically, the magenta module was significantly up-regulated, whereas the brown module was down-regulated in iE3/Cre+ mice compared to iE3/Cre− mice (Fig. 5b). Functional annotation showed that proteins in the brown module (e.g., Psma1, Psma3, Aboc1, Apob) were associated with the proteasomal protein catabolic and lipid metabolic processes (Fig. 5c, d). The magenta module containing hub proteins such as Timp3, Bsg, Thbs1, Serpine2, Hpn, and Tgfb1 was enriched for fibrinogen complex, regulation of protein secretion, and cell-cell adhesion pathways (Fig. 5c, d). Timp3 is an ECM-binding protein that modulates the turnover of ECM through inhibiting the activity of metalloproteinases (MMPs)37,38. Thus, the increased Timp3 might be a mechanism contributing to improved vascular health and brain function of iE3/Cre+ mice39. Interestingly, the regulatory network analysis found a negative association between plasma Timp3 and ubiquitin protein ligase binding, unfolded protein, and heat shock protein binding in the endothelial cells of iE3/Cre+ mice (Fig. 5e, f), implying a down-regulation of stress responses.

Fig. 5 ∣. ApoE isoform-specific changes in plasma protein network and the association with vascular related pathway.

Plasma from iE3/Cre (a-f) mice (Cre−, n=4; Cre+, n=4), and iE4/Cre (g-m) mice (Cre−, n=4; Cre+, n=4) were subjected to proteomics analysis. The protein modules (MEs) associated with APOE3 or APOE4 genotype were identified by WGCNA analysis. a, g, Module-genotype correlation. Numbers in the table indicate the correlations of the corresponding module eigengenes and genotype, with the P values shown in parentheses. The red color represents positive correlation and blue represents negative correlation to APOE genotype. b, h, Modules that are significantly correlated with APOE3 (b) or APOE4 (h) genotype. The box in the plots displays 25th and 75th percentile values. The center line represents the median and the whiskers show minimum and maximum values. c, i, Network plots of the proteins with high intramodular connectivity in the brown and magenta modules in the iE3/Cre group (c) and red and tan modules in the iE4/Cre group (i). d, j, Pathway analysis using gene ontology (GO) showing the pathways enriched in the protein-sets of the brown and magenta modules in the iE3/Cre group (d), as well as red and tan modules in the iE4/Cre group (j). Limma’s moderate t-test statistics were used. e, Circos plot showing the associated genes and pathways in the endothelial cell clusters negatively correlated with the changes of plasma Timp3 in the iE3/Cre group. f, Timp3-regulated pathways in the endothelial cell clusters of the iE3/Cre group. k, Circos plot showing the associated genes and pathways in the endothelial cell clusters negatively correlated with the changes of plasma Agt in the iE4/Cre group. l, Agt-regulated pathways in the endothelial cell clusters of the iE4/Cre group. Limma’s moderate t-test statistics were used. m, Circos plot showing the associated proteins and pathways in the plasma correlated with the changes of Cxcl12 in endothelial cell clusters in the iE4/Cre group.

Among the co-expression modules associated with apoE4, the red module was down-regulated, whereas the tan module was up-regulated in iE4/Cre+ mice compared to iE4/Cre− mice (Fig. 5g, h). Hub genes in the red module included Apob, Apoc1, Apoc3, Apom, and Lipc which were involved in lipoprotein metabolism (Fig. 5i). Pathway analysis showed that this module was enriched for plasma lipoprotein particles, lipid transport, and clearance (Fig. 5j). Furthermore, the tan module, enriched for immune response, complement activation (e.g., C1qa, C1ra, C1s1, and C1rl), and fatty acid metabolism (e.g., Agt and Fabp1), was up-regulated in iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 5i, j). The regulatory network analysis found a negative association between plasma angiotensinogen (Agt), known to regulate blood pressure, and pathways related to the regulations of interleukin-1α (IL-1α) secretion, circadian rhythm, nitric oxide biosynthesis, and plasma membrane organization in the endothelial cells of iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 5k, l). Furthermore, a positive regulation of complement activation in the plasma was correlated with Cxcl12 which was increased in the endothelial cells of iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 5m).

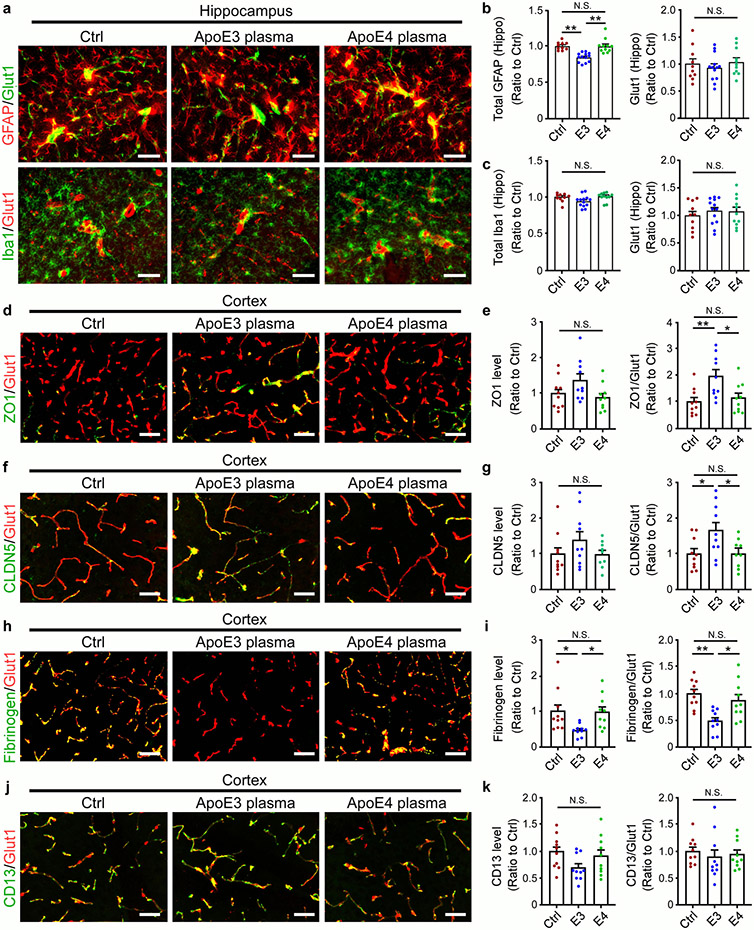

APOE genotype-specific effects of young plasma on brain function

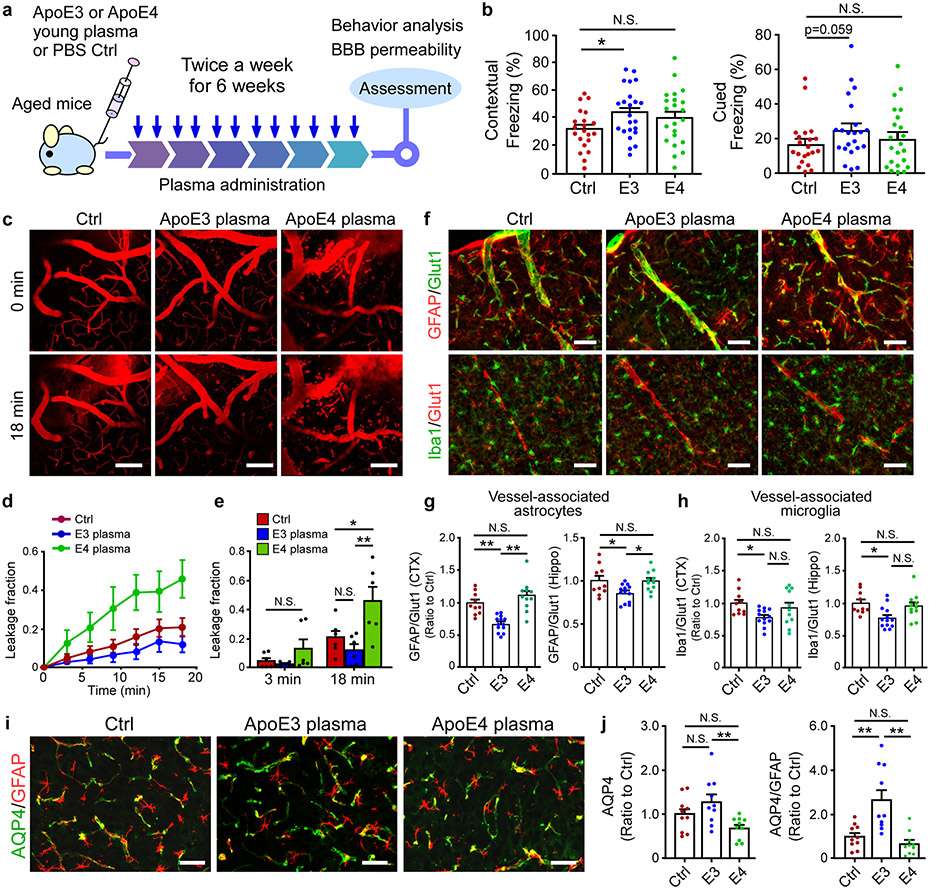

Recent studies showed that exposure to young blood counteracts age-related cognitive decline with the brain vasculature capable of sensing and transmitting the circulatory cues to the brain34,40,41. To examine how young plasma with different human apoE isoforms affects age-associated cognitive functions, plasma from young apoE3 or apoE4 mice was intravenously administrated into aged wild-type mice (Fig. 6a). Intriguingly, apoE3, but not apoE4 young plasma, improved associative memory of the aged animals assessed by contextual fear conditioning test compared to control treatment (Fig. 6b). It is possible that the negative effects of apoE4 offset the beneficial effects of young plasma. We next investigated whether BBB integrity was differentially modulated by peripheral young plasma treatment. As expected, aged animals treated with PBS exhibited apparent BBB impairment (Fig. 6c-e). Remarkably, exposure to young apoE4 plasma exacerbated BBB leakage, whereas young plasma from apoE3 mice trended to improve BBB integrity (Fig. 6c-e). The vessel-associated astrocytes and microglia were reduced in mice treated with apoE3 plasma, in particular in the cortex (Fig. 6f-h, Extended Data Fig. 7a-c). Intriguingly, apoE3 young plasma treatment increased the level of AQP4, whereas apoE4 young plasma did not have an effect (Fig. 6i, j). The levels of TJ proteins ZO1 and CLDN5 were increased in aged mice treated with apoE3, but not apoE4, young plasma (Extended Data Fig. 7d-g). The vessel-associated fibrinogen deposition was decreased in apoE3, but not apoE4, young plasma-treated mice (Extended Data Fig. 7h, i). Finally, young plasma treatment did not impact CD13-positive pericyte coverage in aged animals regardless of apoE isoform (Extended Data Fig. 7j, k). In summary, our results indicated that young plasma affects brain cognition and BBB functions in an apoE isoform-dependent manner.

Fig. 6 ∣. Differential effects of apoE3 and apoE4 young plasma on cerebrovascular integrity and cognitive function in aged mice.

a, Schematic illustration of the experimental procedures for young plasma treatment. b, Memory performance of mice treated with Ctrl, or young plasma from apoE3-TR or apoE4-TR mice examined by fear conditioning contextual test (Ctrl: n=21; E3: n=23; E4: n=22), and cued test (Ctrl: n=21; E3: n=22; E4: n=22). The percentage of time spent showing freezing behavior in response to stimulus in contextual or cued test is shown. *, P=0.046, Wilcoxon rank sum test. c-e, Two-photon imaging was used to assess BBB integrity in 28-month-old mice (n=3/group) treated with Ctrl, apoE3 or apoE4 young plasma. Mice were intravenously injected with Texas Red conjugated dextran (40 kDa), and the BBB permeability was examined. Scale bar, 100 μm. d, The fractions of BBB leakage over time are shown. e, The fractions of BBB leakage at 3 or 18 min after injection of dextran were quantified. *, P = 0.01; **, P = 0.0006. f, g, Vessel-associated astrocytes or microglia in the cortex were examined by double labeling with anti-GFAP (astrocyte) or anti-Iba1 (for microglia) together with endothelial marker Glut1 antibody (for visualizing vasculature). Representative images of cortex from experimental mice are shown. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data from individual animals are shown. g, Fluorescence intensity for GFAP signals surrounding vasculature in the cortex (Ctrl vs. E3: **, P = 0.0009; E3 vs. E4: **, P<0.0001) or hippocampus (Ctrl vs. E3: *, P=0.04; E3 vs. E4: *, P=0.039) of mice (Ctrl: n=10; E3: n=13; E4: n=11) was quantified. h, Fluorescence intensity for Iba1 signals surrounding vasculature in the cortex (*, P=0.045) or hippocampus (*, P=0.017) of mice (Ctrl: n=10; E3: n=13; E4: n=11) was quantified. i, j, Brain sections from young plasma-treated mice (10 mice/group) were immunostained with anti-AQP4 (green) and anti-GFAP (red) antibodies. The AQP4 immunoreactivity (**, P=0.008) and AQP4/GFAP signals (Ctrl vs. E3: **, P=0.002; E3 vs. E4: **, P=0.0002) was quantified. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s post-hoc test.

ApoE4 diminished the beneficial effect of young plasma on the integrity of human brain endothelial cells

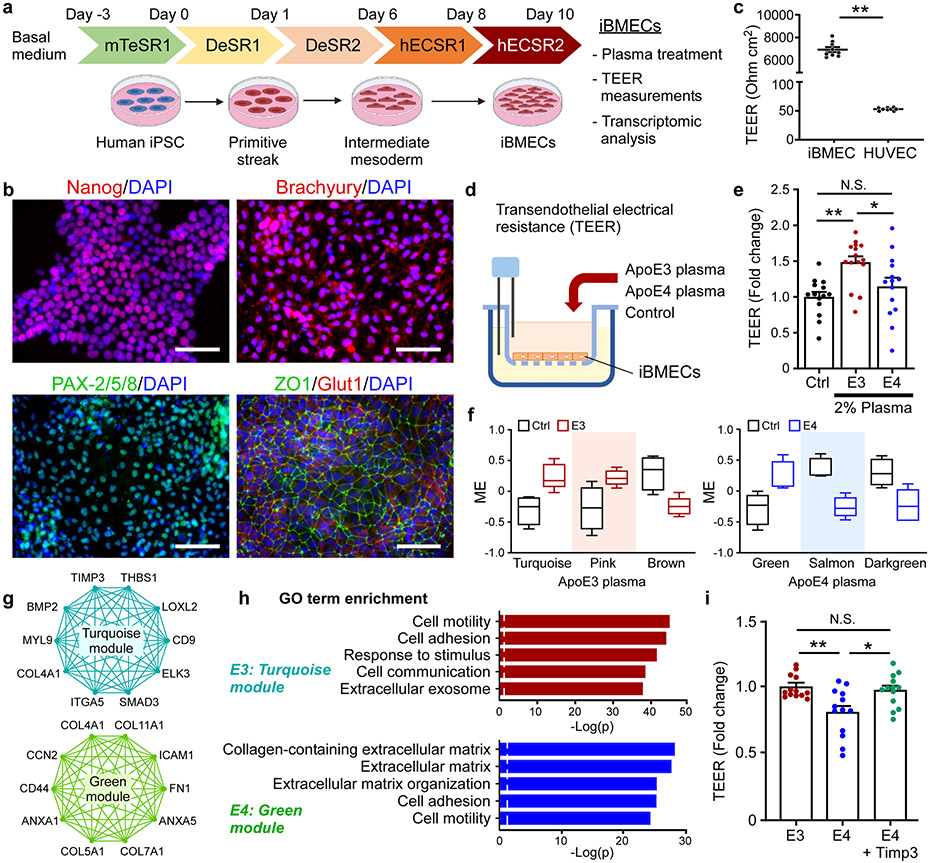

To explore how brain endothelial cells respond to the apoE-regulated blood factors, we established a model of brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) differentiated from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (Fig. 7a). The markers for the pluripotency of human iPSCs, mesodermal differentiation, and endothelial cells (ZO1 and Glut1) were validated (Fig. 7a, b). Furthermore, human iBMECs showed significantly higher trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) values compared to human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), indicating the formation of robust endothelial junctions (Fig. 7c). To investigate the effect of young plasma with different apoE isoforms on the endothelial barrier integrity, iBMECs were treated with control (PBS-citrate), apoE3, or apoE4 young plasma for 24 hours (Fig. 7d). Remarkably, compared to the control, we observed a significant increase of the TEER values in the apoE3, but not in the apoE4, young plasma-treated group (Fig. 7e). This result indicates that apoE3 young plasma increased the barrier integrity of iBMECs, while the apoE4 young plasma failed to do so. To further investigate the associated molecular changes, plasma-treated human iBMECs were subjected to RNA-seq, followed by WGCNA analysis. Two modules (turquoise and pink) were significantly up-regulated, and two modules (brown and purple) were down-regulated in apoE3-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. 7a; Fig. 7f). Three modules were correlated with apoE4, including one up-regulated (green) and two down-regulated modules (darkgreen and salmon) (Supplementary Fig. 7d; Fig. 7f). To further evaluate the functional changes of iBMECs associated with apoE3 or apoE4 plasma treatment, we performed GO term enrichment analysis on these modules. The modules associated apoE3 plasma were enriched for various cellular responses, such as endosome organization, cell division, and double-strand break repair (Supplementary Fig. 7b, c). Importantly, genes in the turquoise module including TIMP3, THBS1, CD9, ITGA5, and ELK3, were enriched for cell adhesion, cell communication, and extracellular exosome pathways (Fig. 7g, h). The modules associated with apoE4 plasma treatment were enriched for lipid biosynthetic and metabolic processes, and ribosome biogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f). Additionally, genes in green module associated with apoE4 plasma treatment were enriched for collagen-containing ECM, and cell mobility, with hub genes including COL4A1, COL11A1, ICAM1, ANXA1, CD44 and FN1 (Fig. 7g, h), suggesting that peripheral apoE4 may affect vascular function through regulating ECM and endothelial junction integrity. Given that Timp3 was up-regulated in the plasma of iE3/Cre+ mice (Fig. 5d), we next examined whether addition of Timp3 can modulate apoE4-mediated endothelial barrier integrity. Interestingly, co-treatment of Timp3 and apoE4 young plasma significantly increased the TEER compared to apoE4 plasma treatment alone (Fig. 7i). This result implies that apoE4 young plasma might have a compromised ability to support the endothelial barrier integrity via influencing Timp3-mediated pathway and/or associated ECM organization.

Fig. 7 ∣. ApoE isoform-specific effects of young plasma on human endothelial barrier integrity and transcriptomic signature.

a, Schematic diagram of human brain endothelial cell (iBMEC) differentiation from iPSCs and the experimental design. b, Characterization of brain endothelial cell differentiation at different time points. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. The iPSC pluripotency and mesoderm lineage differentiation were confirmed by Nanog, Brachyury (a primitive streak marker), or PAX2/5/8 (an intermediate mesoderm marker) staining, respectively. The iPSC-derived iBMECs were stained for Glut1 (an endothelial marker) and ZO1 (a tight junction protein) at Day 12. Scale bars: 100 μm. c, The transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) in iBMECs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) was measured. **, P < 0.0001. d, The transwell setup in which the iBMECs were treated with control or young plasma, followed by the assessment of the endothelial cell integrity. e, Human iBMECs cultured in the transwell system were treated with PBS-citrate (control), apoE3 young plasma (2%) or apoE4 young plasma (2%) for 24 hr. The TEER values were measured and compared to the control. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. **, P=0.002; *, P=0.034; N.S., not significant. One-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s post-hoc test. f, Modules significantly correlated with apoE3 or apoE4 plasma treatment compared to control identified from RNA-Seq. The box in the plots displays 25th and 75th percentile values. The center line represents the median and the whiskers show minimum and maximum values. g, Network plots of the proteins with high intramodular connectivity in the turquoise module of apoE3 group, and in the green module of apoE4 group. h, Pathway analysis using gene ontology showing the pathways enriched in the gene-sets of the turquoise module and green module. i, The human iBMECs were treated with apoE3 or apoE4 young plasma, or apoE4 plasma together with Timp3 (0.5 μg/ml) for 24 hr, and the TEER values were measured. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. **, P=0.003; *, P=0.012; N.S., not significant. One-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to determine the significance between groups.

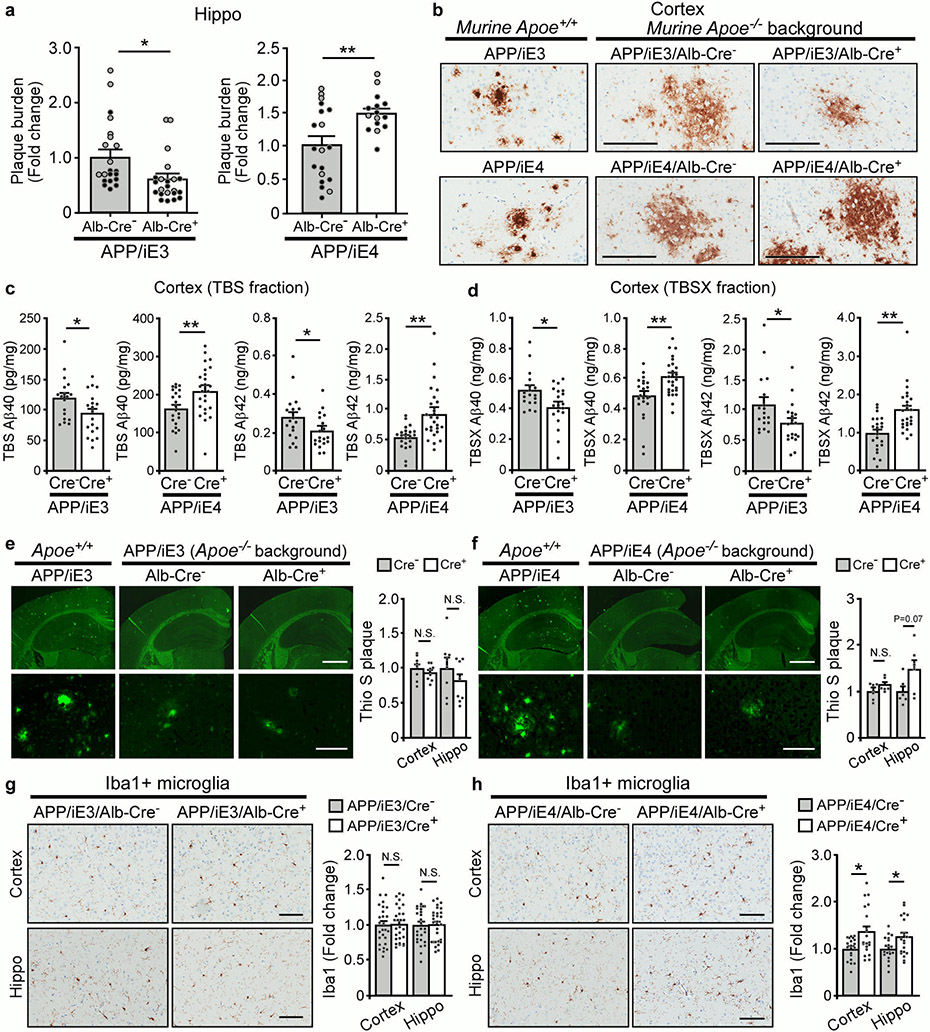

Differential effects of peripheral apoE isoforms on brain amyloid

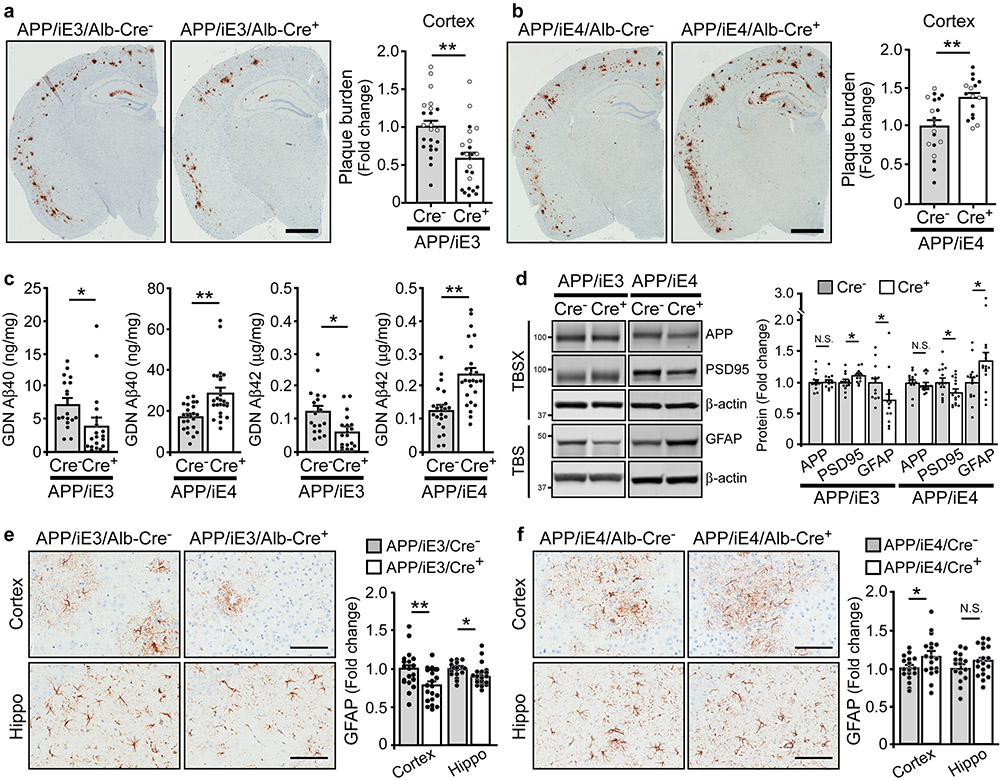

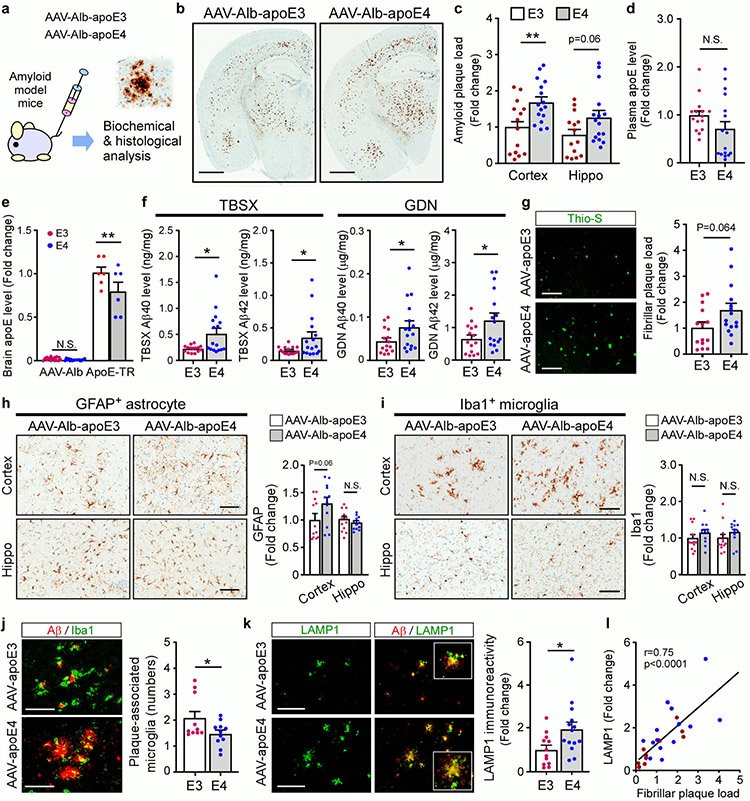

Studies show that brain amyloid deposition is apoE isoform-dependent (E4>E3≥E2)9. However, whether peripheral apoE isoforms affect amyloid pathogenesis and AD-related pathways in vivo remains unclear. We thus bred our liver-specific apoE3 and apoE4 mice with APP/PS1 mice42 in the apoe-KO background to examine their effects on amyloid pathology. Interestingly, we found that expression of apoE3 in the liver suppressed, whereas apoE4 enhanced amyloid pathology (Fig. 8a, b; Extended Data Fig. 8a, b). To analyze how liver-expressed apoE affects the dynamic pools of Aβ, we fractionated brain lysates into TBS-soluble, detergent-soluble (TBSX), and insoluble (guanidine-HCl, GDN) fractions, and quantified Aβ by ELISA43. Consistently, we found that soluble and insoluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were decreased in APP/iE3/Cre+ mice but increased in APP/iE4/Cre+ mice at 9 months of age with total APP levels unchanged (Fig. 8c, d; Extended Data Fig. 8c, d). It is possible that peripheral apoE4 impairs the basement membrane proteins and endothelial functions in cerebral blood vessels which in turn disrupt the efficiency of perivascular drainage of Aβ from the brain44. The absence of apoE in the brain of peripheral apoE models led to minimal fibrillary plaques that were not different among the experimental groups examined by Thioflavin S (Thio S) staining (Extended Data Fig. 8e, f)45,46. In addition, the level of PSD-95 was slightly increased in APP/iE3/Cre+ mice but reduced in APP/iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 8d), suggesting their differential impacts on Aβ-mediated synaptic impairment. Also, we found a profound decrease of astrogliosis in APP/iE3/Cre+ mice, whereas an opposite effect was seen in APP/iE4/Cre+ mice (Fig. 8d-f)20,47. Microgliosis was not changed in APP/iE3/Cre+ mice, whereas a significant increase was observed in APP/iE4/Cre+ mice compared (Extended Data Fig. 8g, h). These results demonstrate that liver-expressed apoE isoforms differentially affect amyloid pathology and related gliosis.

Fig. 8 ∣. Opposing effects of liver-expressed of apoE3 and apoE4 on Aβ plaque deposition and associated neuroinflammation.

a, b, Brain sections from 9-month-old APP/iE3/Alb-Cre mice (Cre−, n=23; Cre+, n=24) and APP/iE4/Alb-Cre mice (Cre−, n=19; Cre+, n=16) were immunostained with a pan-Aβ antibody. Representative images of Aβ staining are shown, and the plaque burden in the cortex was quantified. Scale bar, 1 mm. Black circles are males; grey circles are females. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. E3: **, P=0.005; E4: **, P=0.002, two-tailed Student's t-test. c, Insoluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in the cortex of 9-month-old APP/iE3/Alb-Cre mice (Cre−, n=18; Cre+, n=19) and APP/iE4/Alb-Cre mice (Cre−, n=22; Cre+, n=25) were examined by specific Aβ ELISA. E3: Aβ40 (*, P=0.03); Aβ42 (**, P=0.005). E4: Aβ40 (**, P=0.0004); Aβ42 (**, P<0.0001), two-tailed Student's t-test. d, The levels of APP, postsynaptic marker PSD-95, and GFAP in the cortex of APP/iE3/Alb-Cre mice (Cre−, n=14; Cre+, n=14) and APP/iE4/Alb-Cre mice (Cre−, n=15; Cre+, n=16) at 9 months of age were examined by Western blotting and quantified. E3: PSD-95 (*, P=0.026); GFAP (*, P=0.04). E4: PSD-95 (*, P=0.037); GFAP (*, P=0.037). e, f, Brain sections from APP/iE3/Alb-Cre mice (Cre−, n=19; Cre+, n=21) and APP/iE4/Alb-Cre mice (Cre−, n=17; Cre+, n=18) at 9 months of age were immunostained with GFAP antibody and quantified. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. E3: Cortex (**, P=0.008); Hippo (*, P=0.005). E4: Cortex (*, P=0.046). N.S., not significant, two-tailed Student's t-test.

To further validate our findings in a model where brain apoE is present, we examined the effects of liver-expressed apoE isoforms on amyloid pathology in 5xFAD mice transduced with AAV-Alb-apoE3 or AAV-Alb-apoE4 viruses (Extended Data Fig. 9a). We found that AAV-Alb-apoE4 mice had increased amyloid plaque load in the cortex compared with AAV-Alb-apoE3 mice (Extended Data Fig. 9b, c). The human apoE levels in the plasma were not statistically different between mice expressing apoE3 and apoE4 though it was trending lower in apoE4 mice, while the human apoE was not detectable in the brain (Extended Data Fig. 9d, e). Both detergent-soluble and -insoluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 were higher in mice transduced with AAV-Alb-apoE4 compared to those transduced with AAV-Alb-apoE3 (Extended Data Fig. 9f). A trend of increased fibrillar plaque deposition was observed in mice expressing apoE4 in the liver (Extended Data Fig. 9g). In addition, AAV-Alb-apoE3 mice had a greater number of plaque-associated microglia than AAV-Alb-apoE4 mice, whereas the total immunoreactivity for microglia or astrocytes was not significantly different (Extended Data Fig. 9h-j). Finally, AAV-Alb-apoE4 mice had increased LAMP1-immunoreactive neuritic dystrophy that was positively correlated with fibrillar plaque load (Extended Data Fig. 9k, l). To further evaluate the peripheral apoE isoform effect, we conducted the experiments using the same viruses along with a control AAV-Alb-GFP virus (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Consistently, AAV-Alb-apoE4 mice exhibited an elevated amount of Aβ plaques compared to AAV-Alb-apoE3 mice, whereas their plaque loads were not significantly different from the control cohort (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c). The levels of astrogliosis and microgliosis in AAV-Alb-apoE4 mice were higher than those in AAV-Alb-apoE3 or control mice (Supplementary Fig. 8d-f). Together, our results indicate that peripheral apoE isoforms differentially impact brain amyloidosis, plaque-associated microglial responses, and neuritic dystrophy.

Discussion

APOE4 increases AD risk by multiple pathways. Our current study shows that peripheral apoE4 is sufficient to impair brain functions and exacerbate amyloid pathogenesis. Mice with peripheral apoE4 expression have compromised cerebrovascular integrity and function, and elevated astrogliosis which may collectively contribute to behavioral impairments and accelerated AD pathogenesis. Transcriptomic profiling indicates that apoE4 expression in the liver may lead to an impairment of ECM and basement membranes contributing to endothelial dysfunction. The scRNA-Seq analysis suggests that peripheral apoE isoforms differentially affect immune responses within the glio-vascular units, which in turn can impact vascular function and BBB integrity. Conversely, peripheral expression of apoE3 improves synaptic function and memory, and ameliorates the amyloid pathology. Finally, peripheral administration of young blood plasma with different apoE isoforms shows differential effects on cognitive functions, BBB integrity, and vessel-associated inflammatory responses in aged mice. As drug targeting of apoE for AD therapy will likely involve regulating apoE both in the brain and the periphery, our studies provide mechanistic insights as to how apoE isoforms should be targeted in AD through individualized therapy.

Emerging evidence indicates that peripheral systemic factors, such as blood components, microbial metabolites, and immune cells, can modulate brain homeostasis and functions with age and in diseases48,49. Young blood infusion was found to promote memory function, hippocampal neurogenesis, and vascular remodeling in the aged brain41. A recent AMBAR clinical trial assessing the effects of plasma protein replacement therapy also showed a positive impact in reducing the cognitive decline in mild and moderate AD patients50. These studies support the therapeutic potential of modulating peripheral factors to treat age-related brain dysfunction and AD. Plasma apoE isoform levels have also been shown to correlate with regional brain volume, cerebral glucose metabolism, and possibly cognitive performance51. Our findings show that apoE3 young plasma improves cognitive function and reduces vessel-associated gliosis in aged animals. However, exposure to young apoE4 plasma impairs BBB integrity without deteriorating cognition, likely attributed to the overall beneficial effects of young plasma. It is possible that apoE isoforms influence the systemic factors in the periphery which differentially impact brain functions. Using iBMECs, we show that apoE3, but not apoE4 young plasma is able to increase endothelial junction integrity, whereas addition of exogenous Timp3, one of the blood factors up-regulated in apoE3 plasma, enhanced tight junctions in the presence of apoE4. Loss of Timp3 increases inflammation and aggravates atherosclerosis in apoe-KO mice52. Timp3 levels are decreased in cardiovascular diseases, while replenishment of Timp3 can ameliorate the disease through inhibiting excess MMP activity and inflammation37, supporting a critical role of Timp3 in regulating vascular function. A tight regulation in the levels of Timp family and MMP proteins is critical for vascular ECM remodelling37. It is possible that peripheral apoE3 expression may regulate blood factors, such as Timp3, which improves endothelial integrity and vascular health. Interestingly, LRP1, an apoE receptor, was shown to bind to Timp3 and mediate its endocytosis and degradation53. Additionally, plasma proteomic profiling reveals an up-regulation of immune response and complement upon peripheral apoE4 expression. Complement activation, which regulates the release of cytokines, vascular permeability, and leukocyte extravasation54, may contribute to the vascular dysfunction associated with apoE4. Future studies toward elucidating apoE isoform-dependent differences in plasma proteome, lipidome, and metabolome in preclinical models and plasma samples from healthy individuals and AD patients with different APOE genotypes can facilitate the identification of effective systematic peripheral factors.

Vascular dysfunction and BBB breakdown are implicated in normal aging and AD pathogenesis55. Capillary brain endothelial cells are sensitive to blood circulatory factors and are capable of transducing aging signals to the brain34. We found that peripheral apoE3 expression regulates pathways associated with energy homeostasis, cellular metabolism, cell junction, and brain immune response in glio-vascular units which may contribute to the improvement of cognitive and synaptic functions (Extended Data Fig. 10). Peripheral apoE4 expression leads to up-regulation of immune-related and stress-related pathways, and down-regulation of anchoring junction, mitochondrial function, and ECM pathways in brain endothelial cells. This suggests that peripheral expression of apoE4 may promote vascular inflammation, which transduces inflammatory cues to the brain along with activation of astrocytes and microglia. In addition, liver-expressed apoE4 results in transcriptomic changes in astrocyte endfeet, inflammatory responses, and immune cell infiltration within the glio-vascular unit (Extended Data Fig. 10). It is possible that the aberrant activation of astrocytes in iE4/Cre+ mice compromises the barrier function of perivascular astrocyte endfeet and neurotrophic functions of astrocytes. Finally, an increased accumulation of blood-derived proteins (e.g., albumin, IgG and fibrinogen) in the vessels, perivascular regions, and/or brain parenchyma around the vessels is evident in the iE4/Cre+ mice, likely due to BBB impairment. BBB dysfunction is associated with normal aging and various neurodegenerative diseases56. Fibrinogen leakage upon BBB disruption has been shown to trigger perivascular microglial clustering, microglia-dependent release of neurotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS), synapse loss, and cognitive impairment21,57. Knockout of fibrinogen in AD model mice reduces dystrophic neurites, amyloid plaque load, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) while improving cognition58. Taken together, the vascular related detrimental outcomes may synergistically propagate peripheral apoE4-related effects to the CNS translating to cognitive deficits and exacerbated pathology. Whether microglia and their responses play a vital role in peripheral apoE-mediated brain function and AD pathogenesis requires further investigation.

An early study suggests that greater than 90% of the apoE in the plasma is synthesized by the liver15. However, apoE secreted from macrophages, vascular mural cells, or other organs in the periphery may also affect brain functions. As such, additional studies are required to further define the cell type-specific effects of apoE isoforms on brain functions and AD pathogenesis. In addition, we cannot rule out the possibility that minute amounts of apoE may leak into the brain and contribute to a confounding effect on brain functions. Furthermore, Apoe deficiency in mice leads to vascular deficits, neuronal dysfunction, and memory impairments12,59. As such, we cannot rule out the possibility that apoe-KO background might increase brain susceptibility to peripheral apoE4. This concern is partially alleviated by our complementary approaches using apoE isoform-specific young plasma or AAV-apoE delivery in the wild-type background with similar findings. As astrocytic apoE4 expression is sufficient to drive amyloid pathology20,60, it is reasonable to assume that both CNS and peripheral apoE4 exhibit gain-of-toxic effects on brain functions and AD-related pathology. Supporting this, apoE immunotherapy administered via a peripheral route improves cognitive performance and enhances Aβ clearance in amyloid mouse models61,62. Interestingly, a recent study shows that deletion of apoE in hepatocytes of APP/PS1 mice, which reduces plasma apoE but not brain apoE levels, does not affect the amount of amyloid plaques63. Whether there is a synergistic interaction between peripheral and CNS apoE on amyloid pathogenesis requires further investigation. Importantly, our current findings shed light on potential apoE isoform-dependent mechanisms on cerebrovascular functions. Whether multiple pathways synergistically influence cerebrovascular integrity and brain functions warrants further examination. Future studies should also explore the therapeutic potential of human young plasma with defined APOE genotype such as APOE2/3 and APOE3/3 on cognitive functions in apoE4 model mice. Our findings offer a strong rationale that peripheral apoE is a viable and individualized target alternative to brain apoE for AD therapy.

Methods

Generation of mice expressing apoE isoforms in the liver

The cell type-specific and inducible apoE mouse models were generated by a knock-in strategy targeting the ROSA-26 locus with a vector system containing a floxed STOP cassette and tetracycline-regulatory elements64. The construct for apoE3 or apoE4 includes: 1) ROSA short and long arms at either ends for targeted integration of ROSA26 locus; 2) a loxP-flanked STOP cassette that harbors a Neor gene for selection of integrated clones; 3) a Tet-off cassette that includes tetracycline-controlled transactivator (tTA) (expressed after Cre-mediated excision of the Neor cassette) and a CMV promoter with a tetracycline-responsive element (TRE); 4) human APOE3 or APOE4 cDNA; and 5) an IRES-eGFP cassette. The constructs are termed inducible APOE3-eGFP and inducible APOE4-eGFP. The resulting inducible apoE3 or apoE4 mice were named in short as iE3 and iE4 mice20. To examine the effects of liver-expressed apoE isoforms on brain functions, iE3 and iE4 mice were crossed with Albumin (Alb)-driven Cre recombinase mice (Jackson Lab) and further bred into the murine Apoe knockout background; thus, apoE was exclusively expressed in the liver and not in the brain. The iE3/Alb-Cre mice (named in short as iE3/Cre− and iE3/Cre+) and iE4/Alb-Cre (named in short as iE4/Cre− and iE4/Cre+) mice (including both male and female mice) were used. The iE3/Cre and iE4/Cre mice in the Apoe null background were further bred with APPSWE/PS1ΔE9 (hereafter referred to as APP/PS1) amyloid mouse model42. Mice expressing apoE3 (APP/iE3/Cre− or APP/iE3/Cre+) or apoE4 (APP/iE4/Cre− or APP/iE4/Cre+) in the liver (including both male and female mice) were used to examine the effects of liver-expressed apoE isoforms on amyloid pathology. To examine the effects of liver-expressed human apoE3 and apoE4 in the presence of murine Apoe, 5xFAD amyloid mice (Jackson Lab) were transduced with AAV8-Alb-GFP, AAV8-Alb-apoE3 or AAV8-Alb-apoE4 virus (titer ~1013 vg/ml) at 1-1.5 month of age via intravenous injection. The animals were harvested at 4 months of age for the experiments. The animal housing conditions follows the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Humidity: 30-70% relative humidity; Temperature: 68-79°F). All animal procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Preparation of brain homogenates

Brain tissues were dissected and kept frozen at −80°C until further analysis. Some brain tissues were fixed in 10% neutralized formalin for histological analysis. Mouse brain tissues for biochemical analysis were processed through sequential extraction43. Briefly, frozen brain tissues were homogenized with TBS buffer, supplemented with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma) and PhosSTOP (Sigma), and centrifuged at 100,000g for 60 min at 4°C with supernatant defined as TBS-soluble fraction. Pellets were re-suspended in TBS buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 (TBSX) and mixed gently by rotation at 4°C for 30 min, followed by a second centrifugation at 100,000g for 60 min with supernatant defined as TBSX-soluble fraction. The TBSX-insoluble pellets were re-suspended with 5M guanidine, mixed by rotation at room temperature overnight, and centrifuged at 16,000g for 30 min with supernatant defined as insoluble fraction (GDN-soluble fraction).

Immunohistochemical staining

Paraffin-embedded sections were immunostained with pan-Aβ (Aβ 33.1.1; human Aβ 1-16 specific), anti-GFAP (BioGenex; PU020-UP), and anti-Iba-1 (Wako; 019-19741) antibodies65,66. Immunohistochemically stained sections were captured using the ImageScope AT2 image scanner (Aperio Technologies) and analyzed using the ImageScope software. The immunoreactivities of GFAP and Iba-1 staining in the hippocampus were calculated using the Positive Pixel Count Algorithm available with the ImageScope software (Aperio Technologies). Fibrillar Aβ was stained with Thioflavin S. The images were captured by Aperio Fluorescent Scanner and the stained areas were quantified by Image J. To examine the expression of GFP reporter, frozen slides were mounted and observed under confocal microscopy. For brain Collagen IV staining, frozen brain sections (40 μm thickness) were fixed with acetone/ethanol, and then blocked with 5% normal donkey serum. Sections were incubated in Collagen IV antibody (Rabbit, Millipore, AB756P, 1:300) at 4°C overnight. Sections were then incubated in Alexa Fluor 568 secondary antibody diluted in 1:300. Finally, sections were incubated in fluorescein-labeled Lectin (Vector Laboratories, FL-1171, 1:100) at 4°C overnight to visualize the endothelial cells. Z-stack images of the stained sections were acquired using confocal microscope (model LSM510 Invert, Carl Zeiss), and converted into maximum z-stack projection images. For Cxcl12 and Glut1 co-staining, frozen brain sections were incubated with anti-Cxcl12 (R&D Systems; MAB350; 1:100) and anti-Glut1 (Abcam; ab15309; 1:300) at 4°C overnight. The brain sections were subsequently subjected to incubation with secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse alexa-568 and goat anti-rabbit alexa-488). Images were acquired using Keyence BZ-X800 fluorescence microscope. The area of Cxcl12 signal relative to Glut1 was quantified using ImageJ. Quantification of immunostaining was performed in a blinded manner.

In vivo two-photon imaging and data analyses

For cranial window preparation, the experimental male mice were anesthetized by the inhalation of isoflurane (4% for induction; 2% for surgery, and 0.5 to 1% for imaging) and immobilized on a custom-made stereotactic apparatus. Approximately 5-10 min before the surgery, dexamethasone (2 mg/kg) and buprenorphine (0.2 mg/kg) were subcutaneously administered to reduce inflammation and pain. Body temperature was monitored by a rectal probe and maintained at 37°C by a heating blanket (Homeothermic blanket systems, Harvard Apparatus). After the removal of the scalp, a surgical drill was used to make a 3-4 mm-diameter craniotomy over the somatosensory and motor cortex, and a 5 mm cover slip was added onto the exposed cortex for protection. Experiments were performed only if physiological variables remained within normal limits.

Dextran conjugated with Texas Red (40 kDa, 50 mg/kg, Sigma) was systemically administered to visualize the vasculature and blood flow in the cerebral cortex. Time-lapse imaging of small cortical sub-volumes (30-40 image planes with 1-2 μm axial spacing) was performed for at least 40 min to track the permeability in the cerebral cortex. The interval duration between stack sequences was 2-3 min; PMT settings (including gain and offset) and laser excitation power were kept constant during time-lapse imaging. In addition, a three-dimension stack image (step size: 1 μm) was captured to track and visualize 3D morphology of vasculature. Arterioles, veins, and capillaries (diameter < 5 μm) were discriminated by the following three criteria: blood flow direction from the pial surface, the patterns of line scan, and vessel diameter (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Line scan was performed along the central axis of the single vessel and perpendicular to a single vessel to measure blood flow velocity and vessel diameter, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

The upright laser scanning microscope (BX61WI, Olympus) attached to a Ti:sapphire pulsed laser system (80 MHz repetition rate, <100 fs pulse width, Spectra Physics) and the Prairie view 5.3 software (Bruker) was used for two-photon fluorescence imaging. The 20x (NA, 1.00; WD, 2 mm, Olympus) and 40x water-immersion objectives (NA 0.80; WD, 3.3 mm, Olympus) were used for fluorescent imaging in vivo. An excited wavelength of 830 nm was applied to excite the fluorescence of Texas Red-conjugated dextran, and emission light was differentiated and detected with 615/50 filters. The average laser power for imaging was less than 50 mW.

For data analysis, images were processed using open-source software Fiji (NIH) and commercial software Matlab (Version 8.5.0 R2015a, Mathworks). Registration had been taken to perform the intensity-based alignment of images at the different time points with imregister function in Matlab and StackReg plugin in Fiji. To measure the BBB permeability in the cerebrovasculature, regions of interest (ROIs) were manually circumscribed within the brain parenchyma and a corresponding vessel (5-6 ROIs), and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each ROI was calculated minute by minute. The relative intensity of fluorescence signals (leakage fraction) in the brain parenchyma was defined as ΔF= (Fn–F0)/F0 (where Fn and F0 were fluorescence intensity at any given time point and the initial time point respectively). The BBB permeability surface (PS) area product was calculated by the following equation12: PS=(1-Hct) 1/lv x Vx dlt/dt. Hct is the hematocrit (45%); lv is the initial fluorescence intensity of ROI within the vessel. lt is the intensity of corresponding ROI within the brain at time t. V is the vessel volume, assuming 1 gram of brain is equal to 50 cm2. Our current permeability data indicated that the fluorescence intensity increased linearly with the time, so the PS product was simulated and calculated with the linear regression model of dlt/dt. In addition, Radon transform algorithm had been used to measure blood flow velocity in the cerebral cortex67. Maximum intensity projection was used to calculate vessel diameter and diameter change, and full width at half maximum intensity was defined as vessel diameter.

Lipid and lipoprotein analysis

Plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels were determined by Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and Triglyceride Assay Kit (Cayman) according to manufacturer's instructions, respectively. To determine plasma lipoprotein profiles, the plasma from iE3/Cre (Cre− or Cre+) and iE4/Cre (Cre− or Cre+) mice (n=3/group) at 12 months of age was fractionated by size exclusion chromatography using fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) (GE Healthcare) with tandem Superose 6 columns (GE Healthcare) in PBS containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, PH 7.4, with 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.02% sodium azide at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min68. As controls, pooled plasma from three apoE3-TR or three apoE4-TR mice was included. The total cholesterol in the fractions was measured by Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay (ThermoFisher Scientific) and the percentage of cholesterol was shown. Human high density lipoproteins (HDL), low density lipoproteins (LDL) and very-low density lipoproteins (VLDL) (Athens Research & Technology) were included as controls.

Behavioral studies

Open field assay, elevated plus maze (for anxiety), fear conditioning (for associative learning and memory), and rotarod (for motor learning and coordination) were performed as previously described69. For open field analysis, the animals were placed in the open field chamber (40 x 40 x 30 cm) for 15 min in standard room-lighting conditions. Activity in the open field was monitored by an overhead camera to track movement with AnyMaze software (Stoelting Co.). Mice were analyzed for multiple measures, including total distance traveled, average speed, and the time spent in the center of the chamber (digitally designated by an 8 × 8 cm region) compared to the perimeter. For elevated plus maze, the apparatus consisted of two opposing open arms (50 x 10 cm) and two opposing closed arms with roofless gray walls (40 cm) connected by a central square platform and positioned 50 cm above the ground. Mice were placed in the open arms facing an open arm, and their behavior was tracked for 5 min with an overhead camera and AnyMaze software. The fear conditioning test was conducted in a sound attenuated chamber with a grid floor capable of delivering an electric shock. Freezing was measured with an overhead camera and FreezeFrame software (Actimetrics). Mice were initially placed into the chamber and undisturbed for 2 min, during which time baseline freezing behavior was recorded. An 80-dB white noise served as the conditioned stimulus (CS) and was presented for 30 sec. During the final 2 sec of this noise, mice received a mild foot shock (0.5 mA), which served as the unconditioned stimulus (US). After 1 min, another CS-US pair was presented. The mouse was removed 30 sec after the second CS-US pair. To assess contextual learning, the animals were placed back into the training context 24 hr post-training and scored for freezing for 5 min. To assess cued learning, the animals were then placed in a different context (novel odor, cage floor, and visual cues) for 3 min and then the auditory CS was presented and freezing was recorded for another 3 min. Baseline freezing behavior obtained during training was subtracted from the context or cued tests to control for animal variability. For the rotarod test, mice were placed on the rotating rod with a linear increase in rotation speed from 4 to 40 rpm and ability to maintain balance on a rotating cylinder was measured. Mice were subjected to 4 trials per day for 2 consecutive days, and the latency to remain on the rotarod was averaged for each trial.

Extracellular field recording from hippocampal slices

To examine the LTP in the hippocampus of experimental mice, extracellular recordings were performed as described with modification70. Mice were sacrificed and transverse slices were prepared for electrophysiological experimental paradigms in ice-cold cutting solution containing 110 mM sucrose, 60 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 28 mM NaHCO3, 0.6 mM sodium ascorbate, 5 mM glucose, 7 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM CaCl2. Field excitatory post-synaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were obtained from area CA1 stratum radiatum with the use of a glass microelectrodes (2–4 mΩ) filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM CaCl2. The fEPSPs were evoked through stimulation of the Schaffer collaterals using a 0.1 msec biphasic pulse delivered every 20 sec. After a consistent response to a voltage stimulus was established, threshold voltage for evoking fEPSPs was determined and the voltage was increased incrementally every 0.5-1 mV until the maximum amplitude of the fEPSP was reached (I/O curve). All other stimulation paradigms were induced at the same voltage, defined as 50-60% of the stimulus voltage used to produce the maximum fEPSP amplitude, for each individual slice. Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) was induced with two paired-pulses given with an initial delay of 20 msec and the time to the second pulse incrementally increased 20 msec until a final delay of 300 msec was reached. A fEPSP baseline response was then recorded for 20 min. The tetanus used to evoke LTP was a theta-burst stimulation (TBS) protocol consisting of five trains of four pulse bursts at 200 Hz separated by 200 msec, repeated six times with an inter-train interval of 10 sec. Following TBS, fEPSPs were recorded for 60 min. Potentiation was measured as the increase of the mean fEPSP descending slope following TBS normalized to the mean fEPSP descending slope of baseline recordings.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated by using Trizol (Invitrogen) followed by RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN). For real-time PCR analysis, cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The primer sequences were as follows: Human apoE, TGTCTGAGCAGGTGCAGGAG; TCCAGTTCCGATTTGTAGG. Mouse β-actin, AGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGTA; GCCAGAGCAGTAATCTCCTTC. Mouse PTPN-2, GTGATCCATTGCAGTGCG; TTCCATCAGAACAAGACAGGTAT. Mouse Smad6, ATCACCTCCTGCCCCTGT; CTGGGGTGGTGTCTCTGG. Mouse Chst12, GCCCCCAGCAAGCCAGT-CTTG; AGGCTGGCGTTGGCACAGAAGT. Mouse Isyna, CCTTGGTGCTCCATAATACCT-G; AGTCTGTGCAGAAGCTCACG. Mouse Lefty1, TGTGTGTGCTCTTTGCTTCC; GGGGATTCTGTCCTTGGTTT. Mouse Rspo2, ATAGAGGCCGCTGCTTTG; TGCCGTGTT-CTGGTTTCC. Col11a2 (Mm.PT.58.6983762), Ccbe1 (Mm.PT.58.6423596), and Anxa4 (Mm.PT.58.9558059) predesigned primers were ordered from IDT-DNA. Mouse Col6a3, and Eln primers were purchased from Qiagen. Reactions were prepared using a 20-μl mixture containing universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Real-time quantification was performed on CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Relative mRNA levels were calculated by ΔΔCt method with β-actin used as a reference.

Western blotting

The detailed procedures were carried out as previously described20. Briefly, after the membranes were blocked, proteins were detected with primary antibody. Membrane was probed with LI-COR IRDye secondary antibodies and detected using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR). To examine whether apoE was detectable in the brain, blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, detected by SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce). The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-GFAP (Millipore; MAB360), anti-apoE (WUE4; NB110-60531) anti-PSD-95 (Cell Signaling; #3450), anti-synaptophysin (Millipore; MAB5258), and anti-β-actin (Sigma; A2228) antibodies.

ELISA quantification

ApoE was measured by ELISA as previously described68. Aβ levels in the brain lysates were determined by ELISA with end-specific mAb 2.1.3 (human Aβx-42 specific) and mAb 13.1.1 (human Aβx-40 specific) for capture and HRP-conjugated mAb Ab5 (human Aβ1-16 specific) for detection as described71. The ELISAs were developed using Super Slow ELISA TMB (Sigma). The level of brain Collagen IV was examined by mouse Collagen IV ELISA (LifeSpan BioSciences) according to manufacturer's instructions. Colorimetric quantification was performed on a Synergy HT plate reader (BioTek).

RNA sequencing, quality control, and normalization

RNAs were extracted via the Trizol/chloroform method, followed by DNase and Cleanup using RNase-Free DNase Set and RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). The quantity and quality of all RNA samples were determined by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Chip (Agilent Technologies, CA). A total of 32 samples (8 samples/ genotype) with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 9.0 were used for RNA sequencing (RNAseq) at Mayo Clinic Core facility using Illumina HiSeq 4000. Reads were mapped to the mouse genome mm10. Raw gene read counts, along with sequencing quality control, were generated using the Mayo Clinic RNA-Seq analytic pipeline: MAP-RSeq Version 2.1.172. Conditional Quantile Normalization (CQN) was performed on the raw gene counts to correct for GC bias and gene length differences, and to obtain similar quantile-by-quantile distributions of gene expression levels across samples73. Based on the bi-modal distribution of the CQN normalized and log2-transformed reads per kb per million (RPKM) gene expression values, genes with average log2 RPKM >= 0 in at least one genotype group were considered expressed above detection threshold. Using this selection threshold, 18,841 genes were included in the downstream analysis. One iE3 sample was determined as an outlier by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and excluded from further analyses. It is noted that the mouse Apoe mRNA was detected in RNA-Seq analysis likely due to the gene inactivation approach initially used to generate this apoe-KO mice31. Nonetheless, we confirmed that there is no mouse apoe protein detected in the brain.

Weighted correlation network analysis

To identify groups of genes that are correlated with the APOE genotype, we performed weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA)74 using residual expression values calculated from adjusting for tissue harvest batch, which contributed significantly to the variation of gene expression based on source of variation analysis. Separate WGCNA analyses were performed for the iE3 and iE4 datasets. Unsigned hybrid co-expression networks were built for both WGCNA analyses. Based on the relationships between power and scale independence, the power of 12 was chosen for building scale-free topology for the iE3 dataset, and the power of 8 was chosen for the iE4 dataset. We used hybrid dynamic tree cutting, a minimum module size of 60 genes, and a minimum height for merging modules at 0.4. Each module was summarized by the first principal component of the scaled (standardized) module expression profiles (module eigengene). Each module was assigned a unique color identifier, and genes that did not fulfil these criteria for any of the modules were assigned to the gray module. To assess the correlation of modules to genotype, we defined the iE3/Cre− genotype as 0, and iE3/Cre+ as 1 for the iE3 dataset, and iE4/Cre− genotype as 0, and iE4/Cre+ as 1 for the iE4 dataset. Modules significantly associated with genotype were annotated using WGCNA R function GOenrichmentAnalysis. Genes with high connectivity in the respective modules were considered hub genes. Intramodular gene-gene connection was visualized using VisANT.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis and co-expression network analysis

Gene functional enrichment analysis was executed in a cutoff-free manner with Broad Institute’s Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to screen for “enriched” MSigDB gene ontology (GO) and canonical pathway annotation gene sets26. In GSEA, limma’s moderate t-test statistics were used to rank the transcriptome-wide gene-phenotype association.