Abstract

Poor sleep is associated with the risk of developing chronic pain, but how sleep contributes to pain chronicity remains unclear. Here we show that following peripheral nerve injury, cholinergic neurons in the anterior nucleus basalis (aNB) of the basal forebrain are increasingly active during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. These neurons directly activate vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-expressing interneurons in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), causing disinhibition of pyramidal neurons and allodynia. The hyperactivity of aNB neurons is caused by the increased inputs from the parabrachial nucleus (PB) driven by the injured peripheral afferents. Inhibition of this pathway during NREM sleep, but not wakefulness, corrects neuronal hyperactivation and alleviates pain. Our results reveal that the PB–aNB–S1 pathway during sleep is critical for the generation and maintenance of chronic pain. Inhibiting this pathway during the sleep phase could be important for treating neuropathic pain.

Neuropathic pain is a debilitating chronic pain condition highly comorbid with sleep disorders 1–5. On the one hand, patients with chronic pain often experience sleep disturbances such as insufficient sleep duration, poor sleep quality, and insomnia 4, 5. On the other hand, sleep disturbances frequently increase the risk of individuals developing spontaneous pain symptoms 4–7. Despite the well-established relationship between poor sleep and chronic pain, the precise functions of sleep in chronic pain development are not known. Previous studies in humans and animals have linked the development of neuropathic pain with nerve damage-induced maladaptive plasticity in the pain pathway 8–16. This includes increased activity, excitability, and synapse remodeling of excitatory neurons and disinhibition of local inhibitory circuits in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) 17–20. In mice, continuous but not acute inactivation of S1 after nerve injury prevents sustained pain symptoms 19, suggesting the protracted involvement of somatosensory cortical circuits in chronic pain development. Given the important role of sleep in cortical plasticity and function 21–29, we investigated whether sleep contributes significantly to circuit changes perpetuating neuropathic pain.

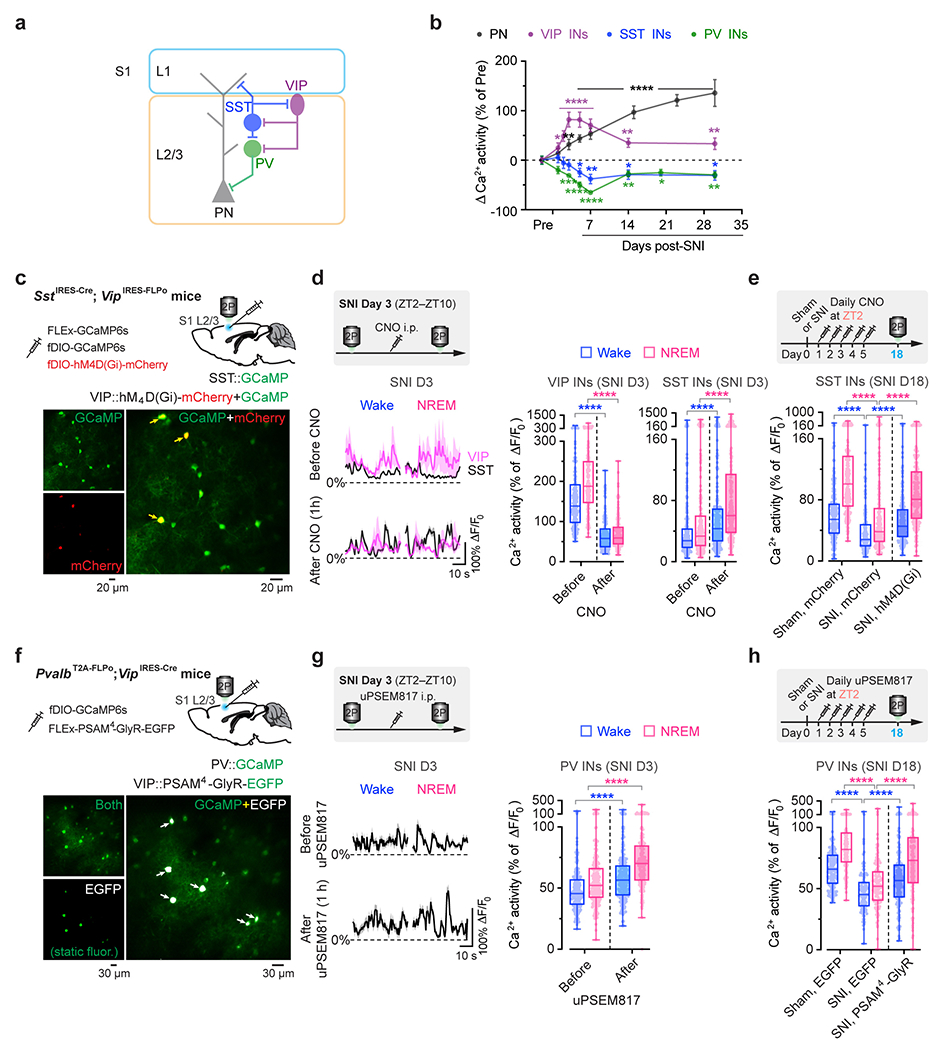

Activation of S1 during NREM sleep

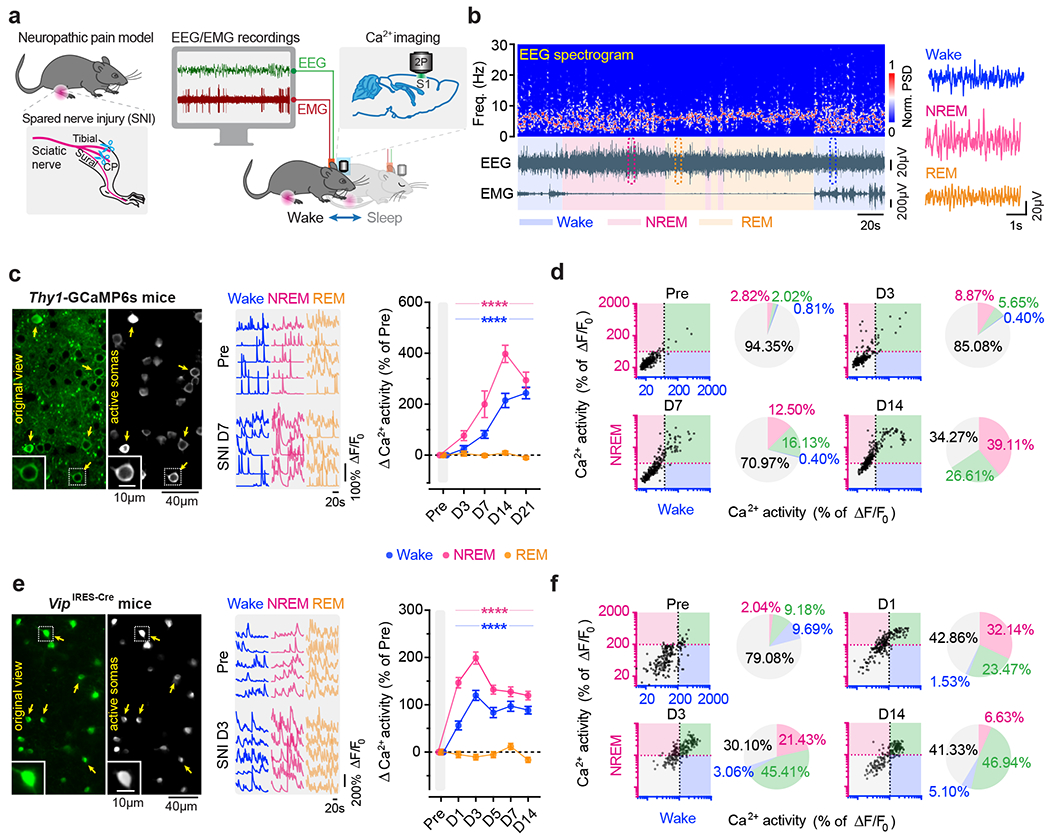

To study the role of sleep in pain-related changes of somatosensory circuits, we examined the activity of S1 neurons across sleep-wake states in a spared nerve injury (SNI) model of peripheral neuropathic pain (Fig. 1a). Pyramidal neurons (PNs) expressing a genetically encoded calcium (Ca2+) indicator GCaMP6s in the hindlimb region of S1 were longitudinally imaged in anesthesia-free mice before and days after SNI with transcranial two-photon microscopy. To directly relate neuronal activity to the animals’ brain states, we simultaneously recorded electroencephalogram (EEG) and electromyography (EMG) signals (Fig. 1b). As compared to pre-surgery, we found that Ca2+ activity in the somas of layer 2/3 (L2/3) PNs progressively increased 3–21 days after SNI during both wakefulness and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, but not during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Fig. 1c). Notably, this hyperactivation of S1 PNs was more pronounced during NREM sleep than during quiet wakefulness. Three days after SNI (the acute phase of neuropathic pain), 15% and 6% of PNs showed increased spontaneous activity under NREM and wake states, respectively, whereas 14 days after SNI (the chronic phase of neuropathic pain), 66% and 27% of PNs showed increased spontaneous activity under NREM and wake states, respectively (Fig. 1d). Together, these results show that S1 PNs are robustly activated during NREM sleep during the progression of neuropathic pain.

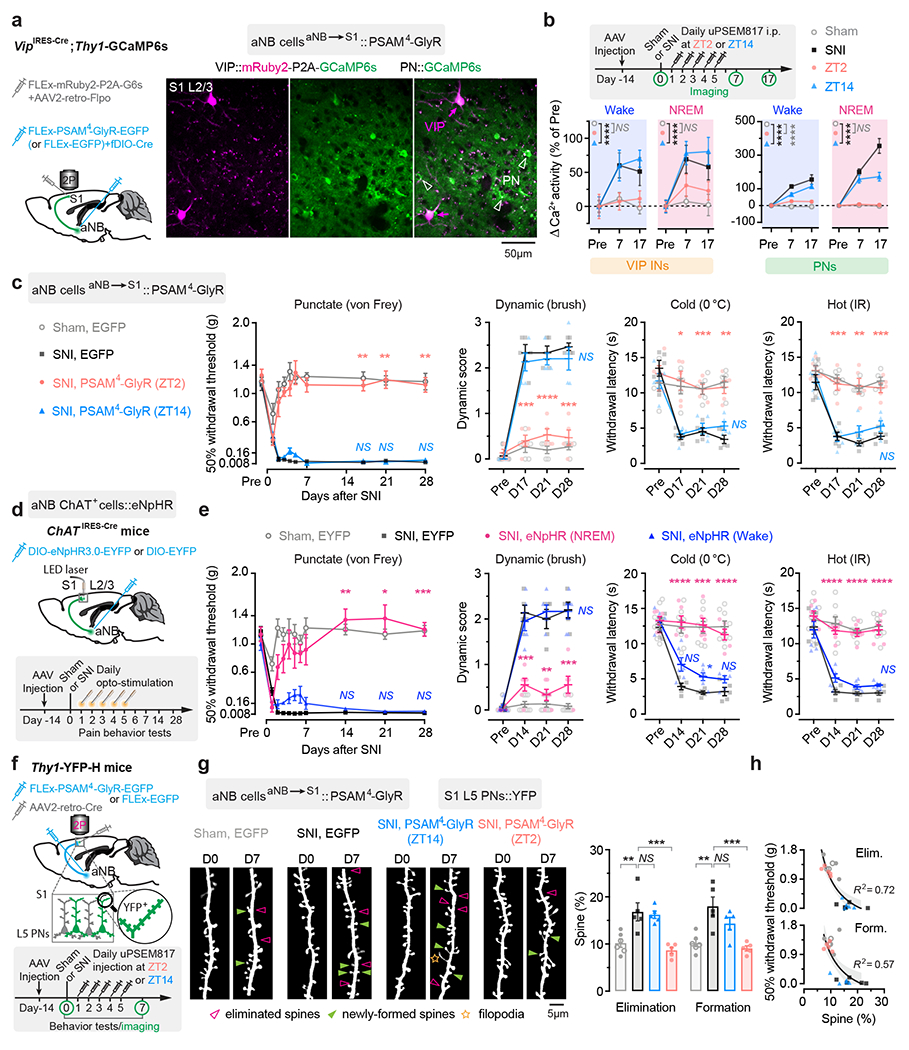

Fig. 1 |. Pyramidal neurons and VIP interneurons are hyperactive during NREM sleep in S1 of mice with neuropathic pain.

a, Schematic of SNI and in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging in S1 combined with EEG/EMG recordings. b, Representative EEG power spectrum (top) and EEG/EMG signals (bottom) under various brain states. Boxed regions are shown magnified on the right. PSD, power spectrum density. c, Left, representative images of L2/3 PNs expressing GCaMP6s (original view) and active somas extracted by the automated analysis pipeline. Insets, zoom-in view of the boxed region. Middle, corresponding Ca2+ traces of active somas (arrows) before and 7 days after SNI. Right, changes in somatic Ca2+ activity under wake (****P < 0.0001 vs. Pre), NREM (****P < 0.0001), and REM (P = 0.89, 0.69, 0.99, 0.0002) states after SNI (n = 248 cells from four mice). d, Longitudinal comparison of Ca2+ activity in individual PNs in NREM and wake before and after SNI. Dashed lines, 1 standard deviation (SD) above the population average pre-SNI. Numbers on the pie graphs indicate percentages of cells in the quadrants. e, f, Similar to (c, d), but for VIP INs under wake (****P < 0.0001 vs. Pre), NREM (****P < 0.0001), and REM (P = 0.98, 0.025, 0.99, 0.23, 0.0004) states (n = 196 cells from four mice). Mean ± SEM. NS, not significant; by two-sided Friedman’s test followed by Dunn’s test (c, e). Detailed statistics in Supplementary Table 1.

Previous studies have shown that local inhibitory interneurons (INs) in L2/3 of S1 shift their activity levels during neuropathic pain development: somatostatin-expressing (SST) and parvalbumin-expressing (PV) INs decrease activity, and vasoactive intestinal peptide-expressing (VIP) INs increase activity one month after SNI 19. To better understand the time course of activity alterations in these three classes of cortical INs, we expressed GCaMP6s via a Cre-dependent adeno-associated virus (AAV) in SstIRES-Cre, PvalbT2A-Cre, and VipIRES-Cre mice and imaged Ca2+ activity of INs over time (Extended Data Fig. 1). During wakefulness, different from the gradual increase of Ca2+ activity in PNs over weeks after SNI, SST and PV INs displayed the lowest levels of activity ~7 days after SNI and remained lower than the pre-SNI baseline afterward. Notably, VIP INs reached the maximum changes in activity within 3 days after SNI, ahead of SST and PV INs, suggesting a crucial role of VIP INs in initiating S1 disinhibition. Further analysis of VIP IN activity during sleep revealed a higher level of Ca2+ activity during NREM sleep than during wakefulness 1–7 days after SNI (Fig. 1e). Individually, 67% and 48% of VIP INs increased spontaneous activity 3 days after SNI under NREM and wake states, respectively (Fig. 1f). These results reveal a rapid and marked shift of VIP neuronal activity during NREM sleep in the acute phase of neuropathic pain.

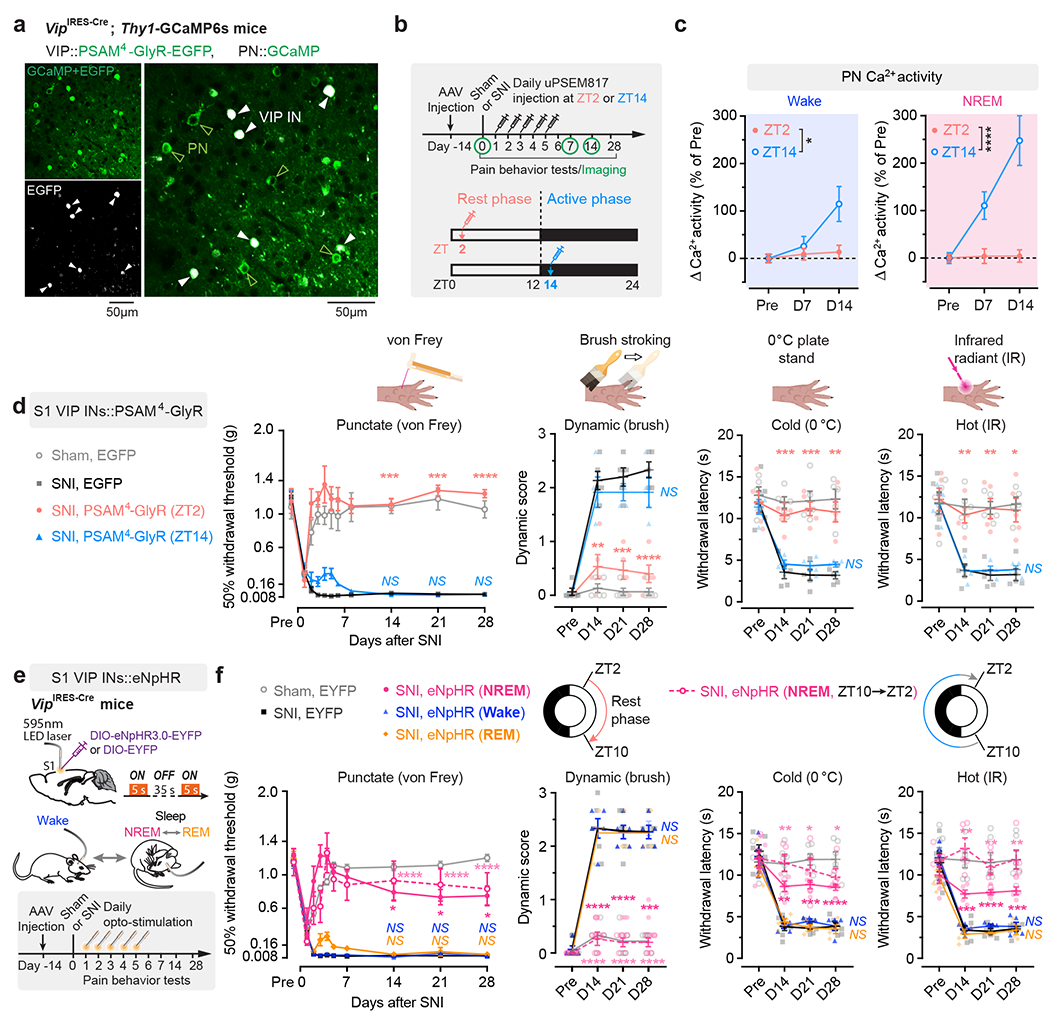

Silencing VIP INs during NREM prevents chronic pain

VIP INs have been shown to provide inhibition to SST and PV INs that directly inhibit PNs 30, 31. To test whether activation of VIP INs during NREM sleep contributes to PN hyperactivation in the S1 and the transition from acute to chronic pain in mice, we decreased VIP activity in vivo using chemo- and optogenetic approaches. For chemogenetic inhibition, we specifically infected VIP INs in L2/3 of S1 with a Cre-dependent AAV encoding PSAM4-GlyR in VipIRES-Cre mice crossed with Thy1-GCaMP6s mice (Fig. 2a). Binding of the ligand uPSEM817 to PSAM4-GlyR strongly suppresses neuronal firing in target cells 32. Indeed, uPSEM817 delivered through an intraperitoneal injection induced a substantial decrease in VIP Ca2+ activity in vivo, which lasted for 5–6 h (Supplementary Fig. 1). Following SNI in mice expressing PSAM4-GlyR in VIP INs, we injected uPSEM817 once per day, either at Zeitgeber time 2 (ZT2) (corresponding to the rest phase of the mouse) or at ZT14 (the active phase), for a total of 5 consecutive days (the acute phase of neuropathic pain) and examined the activity of PNs 1 to 2 weeks later (Fig. 2b). We found that uPSEM817 treatments at ZT2 were sufficient to prevent SNI-induced PN hyperactivity. By contrast, uPSEM817 injections at ZT14 had only mild effects on decreasing PN activity in SNI mice (Fig. 2c). Moreover, chemogenetic inhibition of VIP INs during the rest phase robustly enhanced the activity of SST and PV INs, consistent with the connectivity scheme of VIP→SST/PV→PNs within the local circuits (Extended Data Fig. 1). When we measured the animals’ pain behaviors over time, we found that continuous inhibition of VIP INs during the rest phase prevented the development of mechanical and thermal allodynia, whereas VIP inhibition during the active phase had no effects on the animals’ pain sensations (Fig. 2d). Using a two-compartment conditioned place preference (CPP) test, we further assessed the ongoing pain in these animals (Extended Data Fig. 2). Four weeks after SNI, while non-treated SNI mice preferred to stay in the compartment paired with lidocaine analgesia, SNI mice treated with uPSEM817 during the rest phase showed no such preference in the CPP test (Extended Data Fig. 2), indicating the absence of ongoing pain.

Fig. 2 |. Silencing VIP INs during NREM sleep prevents S1 hyperactivation and nociceptive allodynia.

a, Representative two-photon images of VIP INs expressing PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP and PNs expressing GCaMP6s (7 mice). b, Timeline for chemogenetic inhibition of VIP INs after SNI, at ZT2 (rest phase) or ZT14 (active phase), in vivo Ca2+ imaging, and behavioral testing. c, PN Ca2+ activity in SNI mice with VIP INs inhibited at ZT2 (n = 152 cells from three mice) or ZT14 (n = 182 cells from four mice). Wake, F(1, 996) = 5.31, P = 0.021; NREM, F(1, 996) = 25.12, P < 0.0001. d, Nociceptive thresholds under various conditions (n = 7, 5, 5, 4 mice for von Frey, n = 5, 5, 5, 4 mice for other tests). Daily VIP inhibition at ZT2, but not ZT14, reduces punctate (ZT2 vs. SNI, P = 0.0006, 0.0003, < 0.0001 on day 14, 21, and 28, respectively), dynamic (P = 0.0025, 0.0004, < 0.0001), cold (P = 0.0008, 0.0003, 0.0069) and hot (P = 0.0027, 0.0044, 0.011) allodynia after SNI. IR, infrared radiant. e, Experimental design for brain state-dependent inhibition of VIP INs expressing eNpHR. f, Nociceptive thresholds under various conditions (n = 6, 6, 5, 5, 5, 4 mice). Daily VIP inhibition in NREM, but not wake or REM, reduces punctate (NREMZT2–10 vs. SNI, P = 0.018, 0.015, 0.038; NREMZT10–2 vs. SNI, P < 0.0001), dynamic (NREMZT2–10 vs. SNI, P < 0.0001, < 0.0001, = 0.0002; NREMZT10–2 vs. SNI, P < 0.0001), cold (NREMZT2–10 vs. SNI, P = 0.0012, 0.0003, < 0.0001; NREMZT10–2 vs. SNI, P = 0.0023, 0.034, 0.010), and hot (NREMZT2–10 vs. SNI, P = 0.0006, < 0.0001, 0.0004; NREMZT10–2 vs. SNI, P = 0.0026, 0.0019, 0.0052) allodynia after SNI. Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant; by two-sided two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test (c, d, f). Detailed statistics in Supplementary Table 1.

As mice spent most, but not all, of their time sleeping during the rest phase (Extended Data Fig. 3), we next examined the effects of silencing VIP INs only during sleep using a light-activated chloride channel 33. We unilaterally injected an AAV expressing Cre-dependent halorhodopsins fused with a yellow fluorescent protein (eNpHR3.0-EYFP) into the S1 of VipIRES-Cre mice and then implanted a cannula guiding a fiber-optics of 200 μm diameter right above the injected site to allow for light delivery (Fig. 2e). Post hoc histological analysis revealed that the majority of eNpHR3.0-EYFP+ cells expressed Vip mRNA and that approximately 90% of the total population of VIP INs contained eNpHR3.0-EYFP (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the laser light would mainly inhibit VIP INs. Two weeks after viral injection, following SNI on the contralateral hindlimb, we performed optogenetic inhibition daily in the rest phase, from ZT2–ZT10, for 5 consecutive days. During each optogenetic session, low-frequency laser pulses were applied intermittently (i.e., 5 s ON and 35 s OFF) and temporally paired with wake, NREM, and REM states, respectively, based on EEG and EMG signals (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Fig. 3). On average, the total time of laser ON across 4–5 h NREM sleep was 32.30 ± 0.77 (mean ± SEM) min per day (n = 5 mice) (Supplementary Fig. 3). As a control, a similar time of laser ON (31.74 ± 0.76 min per day; n = 5 mice) was applied during wakefulness. The total time of laser ON for inhibition during REM sleep was 7.48 ± 0.72 min per day (n = 4 mice). Compared with SNI mice that did not receive laser light, we found that light paired with NREM, rather than REM or wake, significantly increased the animals’ nociceptive thresholds (Fig. 2f) and alleviated ongoing pain (Extended Data Fig. 2). In control mice expressing EYFP without eNpHR, light delivery during NREM had no effects on pain sensations. These findings demonstrate that activation of VIP INs during NREM sleep is critical for transitioning from acute to chronic pain after SNI. Suppressing VIP INs across the same amount of NREM sleep (4–5 h) but at a different time of the day (i.e., ZT10–ZT2) had similar effects on pain relief (Fig. 2f, Extended Data Fig. 2), suggesting no involvement of circadian timing in this process.

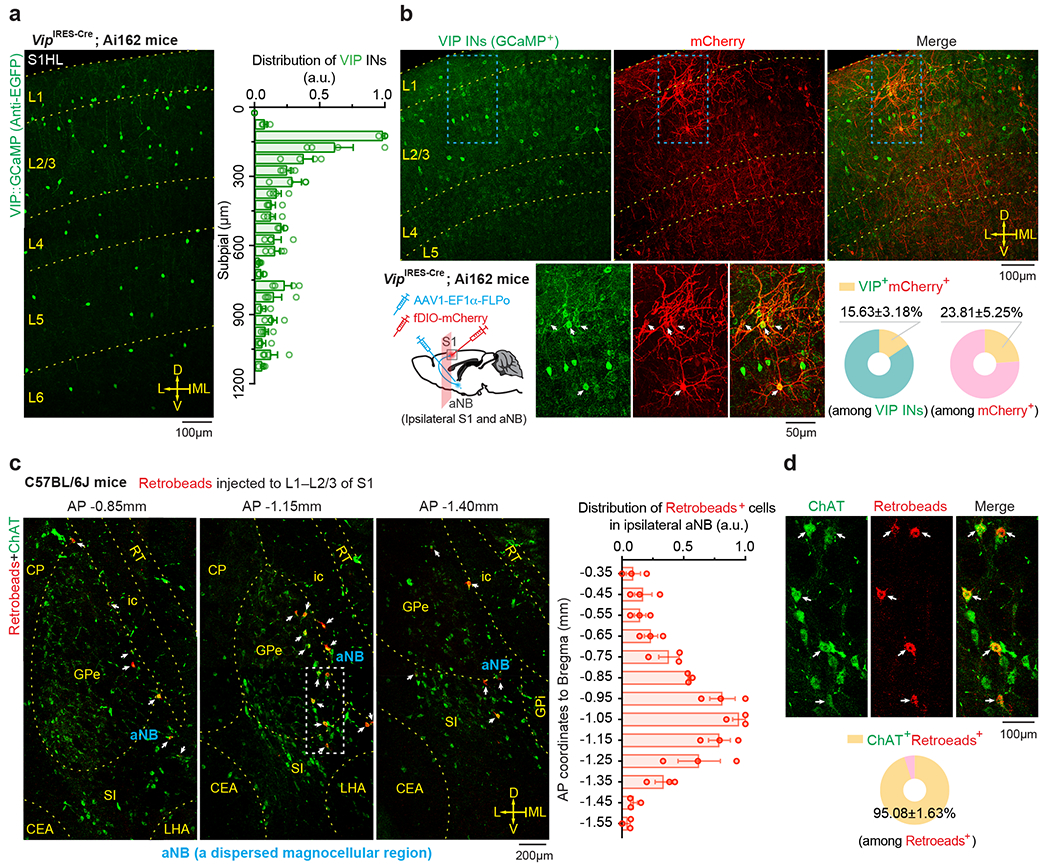

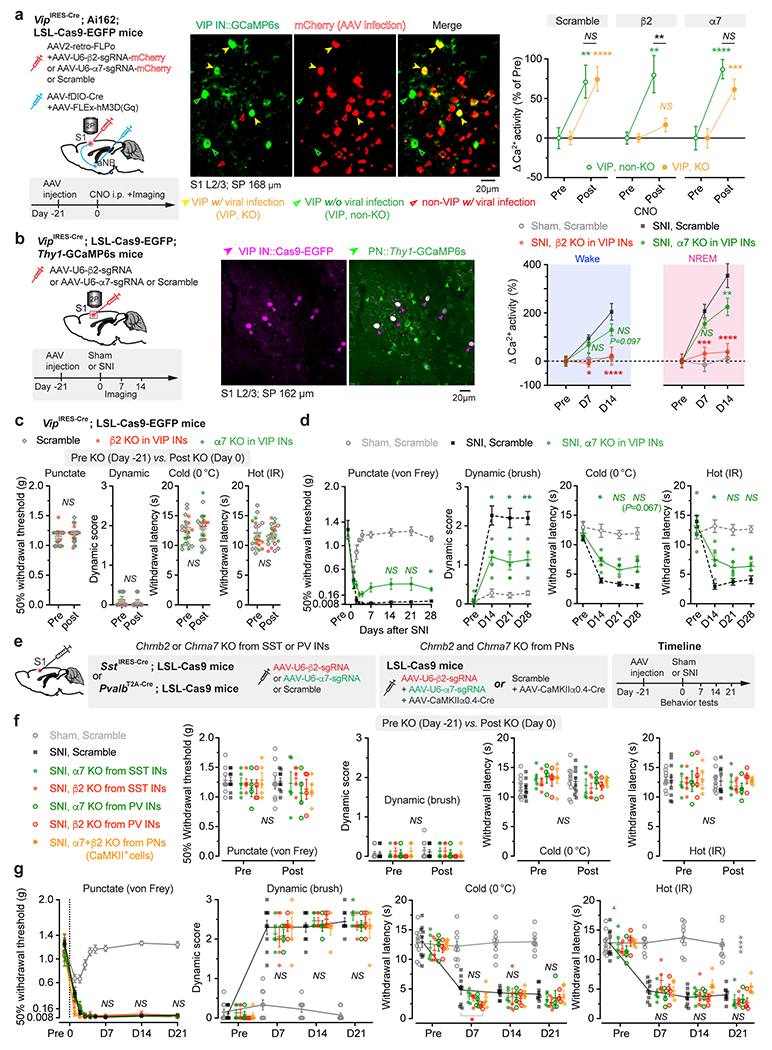

aNB→S1 cholinergic inputs are elevated during NREM

We next investigated the mechanisms underlying the increased VIP neuronal activity during NREM sleep. Cortical VIP INs express cholinergic receptors and can be strongly excited by acetylcholine (ACh) via activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) containing β2 or α7 subunits 34–38. Given intense cholinergic projections from the anterior nucleus basalis (aNB), a subnucleus of the basal forebrain, to the S1 39, we tested whether S1 VIP INs are directly innervated by aNB cholinergic cells 40. We first quantified the percentage of VIP INs that received monosynaptic projections from the aNB. VipIRES-Cre mice were crossed with Ai162 mice to visualize GCaMP-labelled VIP INs (Fig. 3a). The resulting mice were injected into the aNB with an AAV serotype 1 virus (AAV1) encoding flippase (FLP) recombinase to allow transsynaptic delivery of FLP into postsynaptic cells 41. Simultaneously, AAV encoding FLP-dependent mCherry was injected into the S1 to visualize the postsynaptic cells (Fig. 3b). In the S1, mCherry+ cells represented cells receiving monosynaptic projections from the aNB, among which mCherry+GCaMP+ cells were VIP INs that received monosynaptic projections from the aNB (Fig. 3b). We found that ~16% of VIP INs were mCherry+; they accounted for ~24% of the total neuron population in L2/3 of S1 that received aNB→S1 long-range projections (Fig. 3b). In a separate experiment, we quantified the percentage of cholinergic neurons among the aNB→S1 projection cells. We injected red fluorescent Retrobeads into L2/3 of S1 to retrogradely label the presynaptic cells in the aNB and then used ChAT antibodies to label cholinergic neurons in brain slices (Fig. 3c). We found that ~95% of aNB→S1 projection cells were ChAT+ cells (Fig. 3d). Together, these results indicate that ~16% of VIP INs in the S1 receive monosynaptic cholinergic inputs from the aNB.

Fig. 3 |. Monosynaptic connectivity from basal forebrain to VIP INs in S1.

a, Representative image and distribution of VIP INs in S1 of VipIRES-Cre mice crossed with Ai162 reporter line (n = 4 mice). b, Schematic of experimental design and representative images of S1 showing VIP INs (GCaMP+) and neurons receiving monosynaptic inputs from aNB (mCherry+). Magnification of the boxed regions and quantification are shown in the bottom panel (n = 12 sections from three mice). Arrows indicate the colocalized cells. c, Retrograde labeling of aNB neurons by injecting Retrobeads into L1–L2/3 of S1. Left, representative images showing colocalization of Retrobeads+ and anti-ChAT immunoreactive somas in aNB ipsilateral to the injection site. Arrows indicate Retrobeads+ChAT+ magnocellular neurons in aNB (a dispersed magnocellular region in the basal forebrain). Right, distribution of Retrobeads+ cells along the anterior-posterior (AP) axis in aNB (n = 3 mice). a.u., arbitrary units. d, Magnification of the boxed region in (c) and quantification of Retrobeads+ChAT+ cells (n = 12 sections from three mice). Mean ± SEM. L, lateral; ML, midline; D, dorsal; V, ventral; CEA, central amygdalar nucleus; CP, caudoputamen; GPe, external globus pallidus; GPi, internal globus pallidus; ic, internal capsule; NB, nucleus basalis; S1, primary somatosensory cortex; SI, substantia innominata; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; MEA, medial amygdalar nucleus; MEV, midbrain trigeminal nucleus; RT, reticular nucleus of the thalamus.

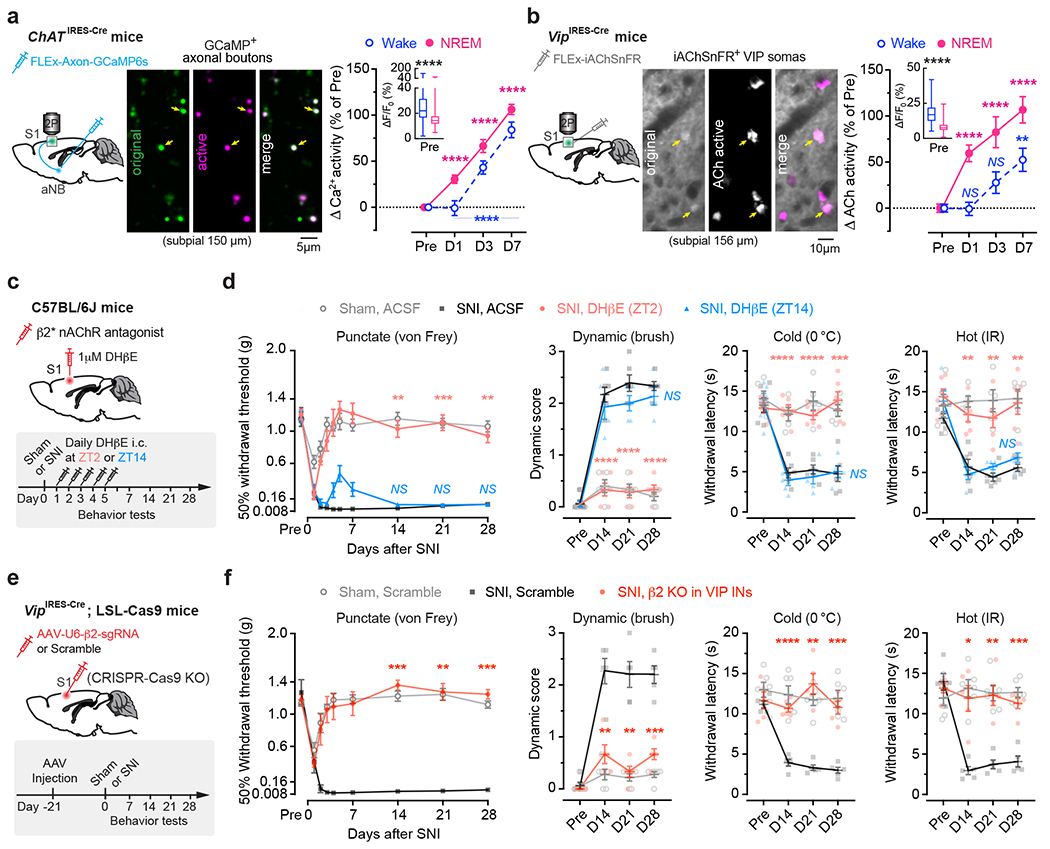

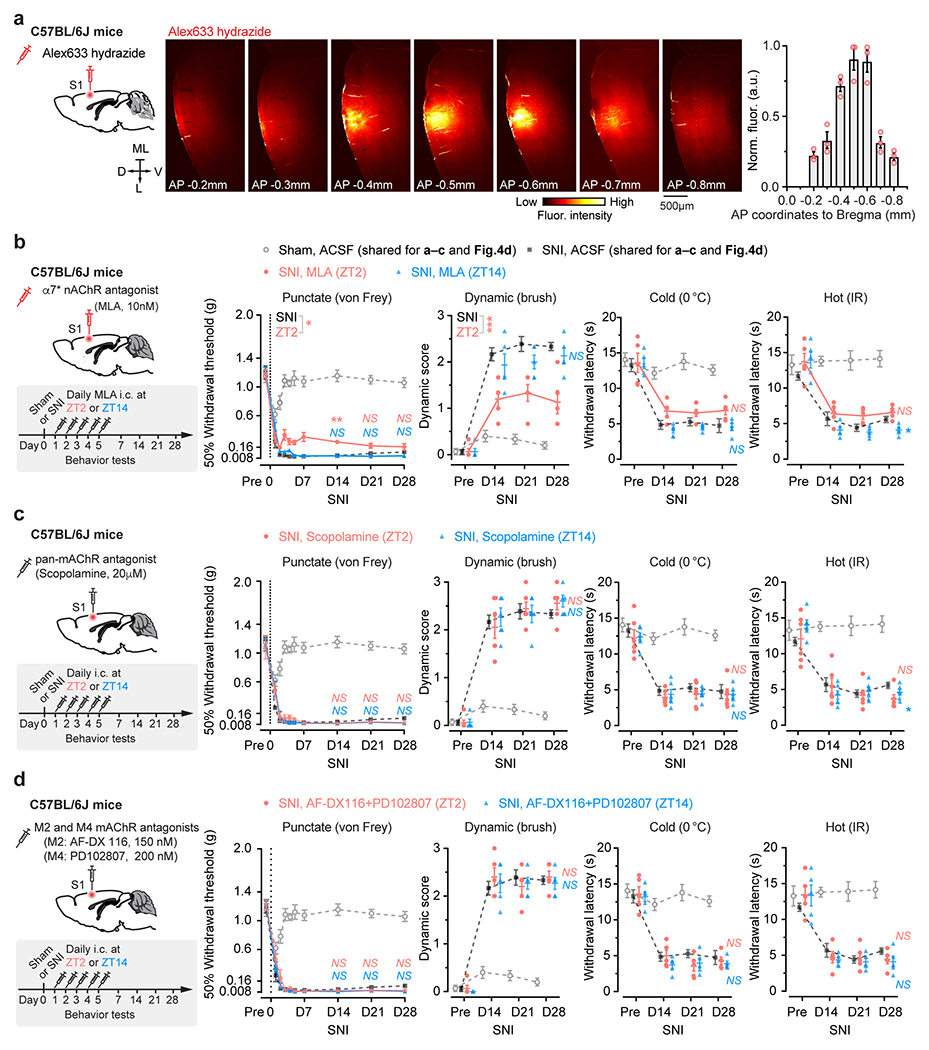

The above findings suggest that aNB cholinergic inputs may have an important role in activating VIP INs during NREM sleep. To test this, we first examined the activity of aNB→S1 cholinergic terminals during NREM sleep. We expressed a Cre-dependent axon-targeted GCaMP6s 42 in the aNB of ChATIRES-Cre mice and imaged axonal Ca2+ in L2/3 of S1 (Fig. 4a). Compared to pre-SNI, aNB→S1 ChAT+ axons exhibited increasing levels of Ca2+ activity during NREM sleep 1–7 days after SNI (Fig. 4a), suggesting an elevated ACh release in the S1. Indeed, when we expressed iAChSnFR 43, a genetically encoded ACh indicator, on the surface of VIP INs, we observed a marked elevation of ACh transients during NREM sleep within the first week after SNI as compared to the pre-SNI baseline (Fig. 4b). Importantly, daily intracortical administration of dihydro-β-erythroidine hydrobromide (DHβE), an antagonist of β2*nAChRs, in the rest phase, abolished persistent allodynia in SNI mice, whereas antagonizing β2*nAChRs in the active phase had no long-lasting behavioral effects (Fig. 4c, d, Extended Data Fig. 4a). Furthermore, daily intracortical administration of methyllycaconitine, an α7*nAChR antagonist, in the rest phase had only minor effects on SNI-induced mechanical allodynia (Extended Data Fig. 4b), and blockade of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) in the rest or active phase had no effects on the animals’ pain behaviors (Extended Data Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4 |. Enhanced aNB→S1 cholinergic inputs during NREM sleep in neuropathic pain.

a, Ca2+ imaging in aNB→S1 axonal terminals. Left, experimental design. Middle, representative image of GCaMP-expressing axonal boutons derived from aNB ChAT neurons. Right, changes in axonal Ca2+ after SNI (n = 268, 206, 200, 216 boutons from three mice) in wake (****P < 0.0001) and NREM (****P < 0.0001). Inset, Ca2+ activity pre-SNI (box bounds and center, quartiles and median; whiskers, min and max; P < 0.0001). b, Similar to (a), but for ACh imaging. Right, SNI-induced changes in ACh activity in wake (P = 0.76, > 0.99, = 0.0023) and NREM (****P < 0.0001), detected by iAChSnFR expressed on VIP INs (n = 102 cells from four mice). Inset, ACh activity pre-SNI (P < 0.0001). c, Experimental design for pharmacological inhibition of β2*nAChRs in S1 by intracortical administration of DHβE at ZT2 or ZT14. d, Nociceptive thresholds under various conditions (n = 5, 6, 6, 5 mice). Antagonizing β2*nAChRs at ZT2, but not ZT14, reduces punctate (ZT2 vs. SNI, P = 0.0019, 0.0007, 0.0010), dynamic (****P < 0.0001), cold (P < 0.0001, < 0.0001, = 0.0003), and hot (P = 0.0023, 0.0032, 0.0068) allodynia 14, 21, and 28 days after SNI. e, Experimental design for conditional knockout (KO) of Chrnb2 (β2) in VIP INs. f, Nociceptive thresholds under various conditions (n = 6, 5, 5 mice). VIP β2 KO reduces punctate (P = 0.0002, 0.0024, 0.0002 vs. scramble), dynamic (P = 0.0041, 0.0028, 0.0006), cold (P < 0.0001, = 0.0033, 0.0007), and hot (P = 0.014, 0.0049, 0.0002) allodynia 14, 21, and 28 days after SNI. Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant; by two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (a), Friedman’s test followed by Dunn’s test (b), Wilcoxon’s test (insets in a, b), or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test (d, f). Detailed statistics in Supplementary Table 1.

Given the broad expression of nAChRs in cortical neurons 44, we employed the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system to specifically delete the Chrnb2 or Chrna7 gene 45 in S1 VIP INs under the guidance of a single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence transduced via a constitutive AAV (Extended Data Fig. 5a). We found that genetic deletion of Chrnb2 in VIP INs markedly reduced SNI-induced PN hyperactivation in the S1 (Extended Data Fig. 5b) and persistent allodynia in mice (Fig. 4e, f). Consistent with pharmacological inhibition results, the improvement in pain behaviors was very limited in SNI mice with Chrna7 deletion in VIP INs (Extended Data Fig. 5c, d). Furthermore, conditional knockout of Chrnb2 and/or Chrna7 in SST INs, PV INs, or PNs had no effects on the animal’s pain behaviors (Extended Data Fig. 5e–g), further confirming the prominent role of VIP β2*nAChRs in mediating neuropathic pain.

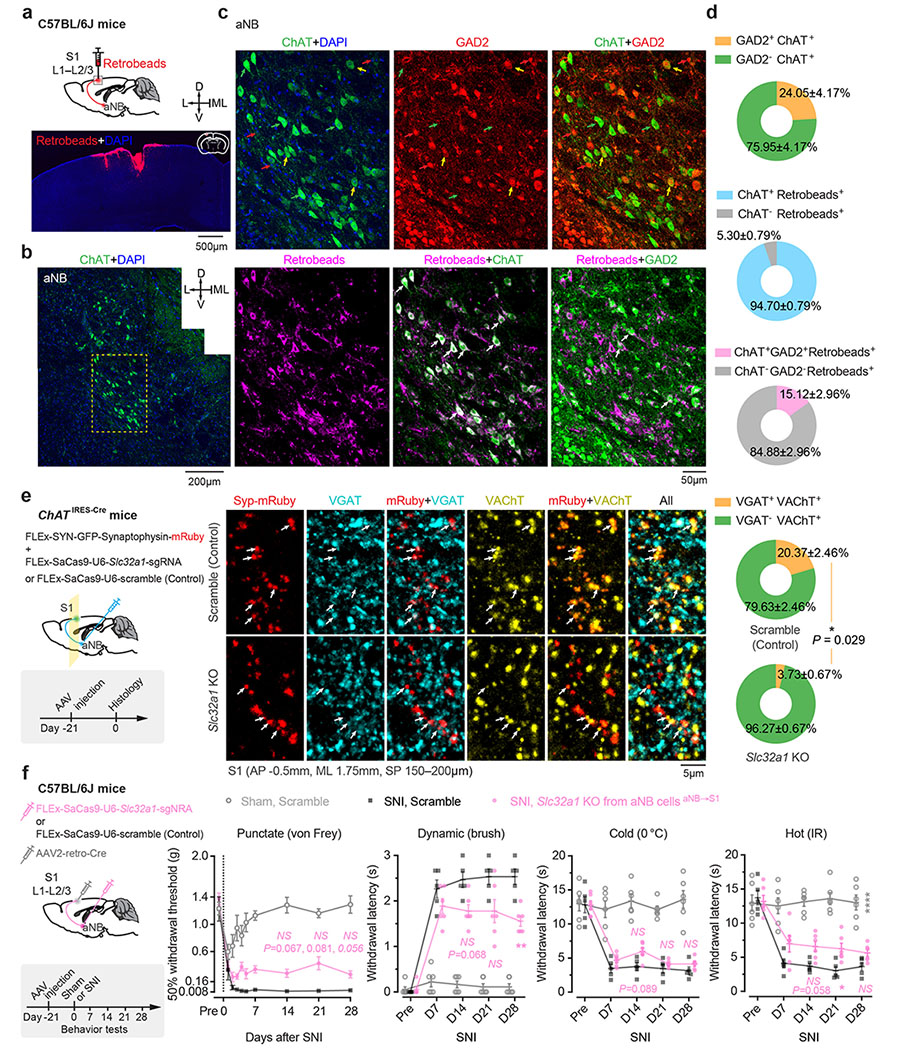

Some cholinergic cells co-release γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) with ACh 46. To test the potential involvement of GABA released from cholinergic terminals, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to selectively delete Slc32a1, a gene encoding vesicular GABA transporter, in aNB→S1 ChAT+ projection neurons 47. Following SNI, mice deleted of Slc32a1 showed no apparent difference in nociceptive thresholds compared to scramble controls (Extended Data Fig. 6), suggesting little contribution of GABA co-release in the development of neuropathic pain. Together, these data indicate that the development of neuropathic pain involves elevated cholinergic inputs from aNB, which communicate with S1 VIP INs mainly through ACh and β2*nAChRs.

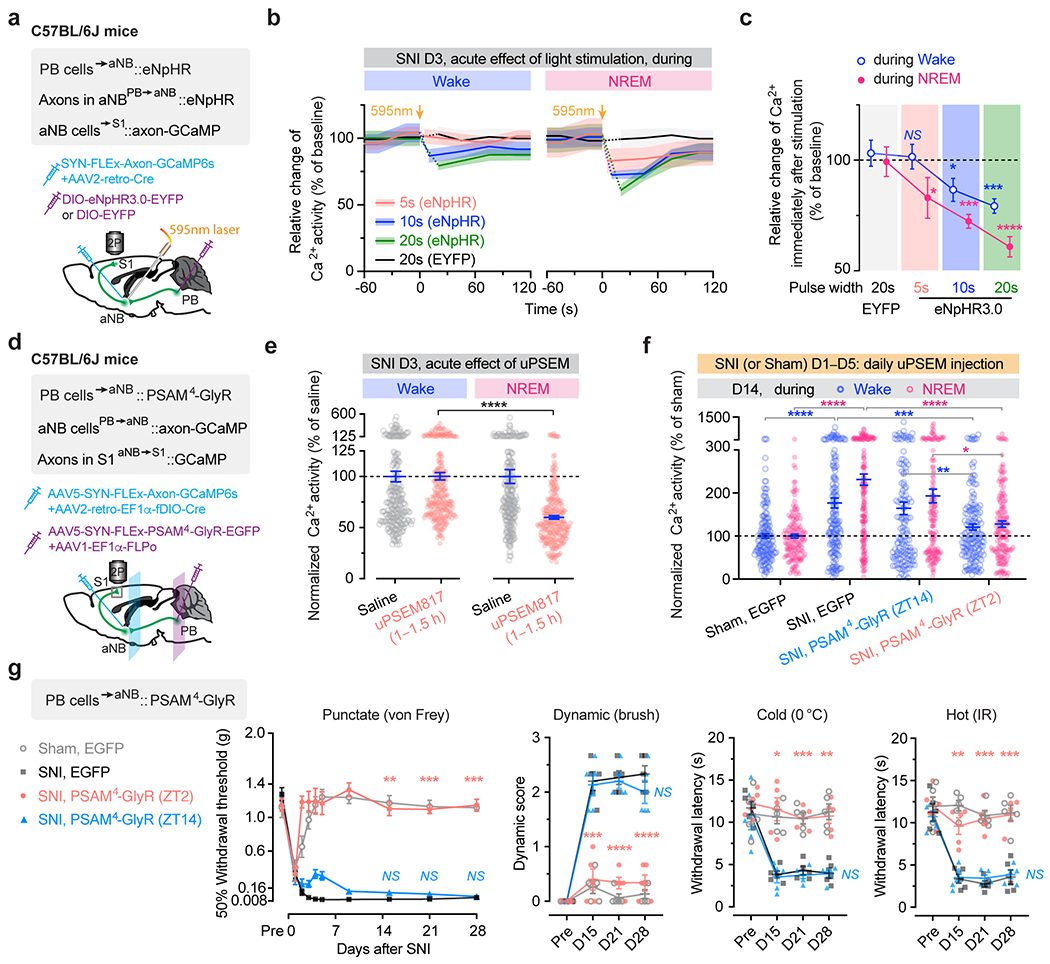

Role of NREM-active aNB→S1 projections

To better understand the role of aNB→VIP INs in neuropathic pain development, we examined the effect of silencing aNB→S1 projections during sleep. Specifically, we injected into the S1 of VipIRES-Cre; Thy1-GCaMP6s mice with Cre-dependent mRuby2-P2A-GCaMP6s and AAV2-retro (a variant of AAV2 permitting robust retrograde access to projection neurons 48) encoding FLP, and simultaneously injected into the aNB with FLP-dependent Cre and Cre-dependent PSAM4-GlyR or EGFP (control) (Fig. 5a). This injection scheme enabled aNB→S1 projection-specific chemogenetic inhibition and Ca2+ imaging of VIP INs and PNs in the S1. Following SNI, mice were injected with uPSEM817 once per day, at either ZT2 or ZT14, for 5 consecutive days (Fig. 5b). As compared to SNI mice expressing EGFP, we found that uPSEM817 treatment of SNI mice expressing PSAM4-GlyR during the rest phase reduced Ca2+ activity in S1 VIP INs and PNs, indicating that silencing aNB→S1 projections during the rest phase prevents SNI-induced S1 hyperactivation. Notably, silencing aNB→S1 projections during the active phase had no effects on SNI-induced persistent Ca2+ elevation in either VIP INs or PNs (Fig. 5b). Consistent with the reduction of activity in S1 neurons, mice with aNB→S1 projection inhibited during the rest phase, but not the active phase, did not develop chronic pain after SNI (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5 |. Silencing aNB→S1 projections during NREM sleep prevents S1 plasticity and pain chronicity.

a, Experimental design for chemogenetic inhibition of aNB→S1 projections (left) and representative two-photon images of VIP INs expressing both mRuby2 and GCaMP6s and PNs expressing GCaMP6s alone. b, Experimental timeline (top) and neuronal Ca2+ activity under various conditions (bottom; VIP, n = 114/four, 92/three, 87/three, 80/four cells/mice; PNs, n = 231/four, 242/three, 228/three, 223/four cells/mice). Daily inhibition of aNB→S1 projections at ZT2 largely prevents SNI-induced VIP (ZT2 vs. sham, wake, F(1, 576) = 0.13, P = 0.72; NREM, F(1, 576) = 2.14; P = 0.14) and PN (wake, F(1, 1356) = 26.16, P < 0.0001; NREM, F(1, 1356) = 2.14, P = 0.57) hyperactivation in S1. c, Nociceptive thresholds under various conditions (n = 5 mice per group). Daily inhibition of aNB→S1 projections at ZT2 reduces punctate (P = 0.0012, 0.0073, 0.0044), dynamic (P = 0.0002, < 0.0001, 0.0002), cold (P = 0.012, 0.0007, 0.0010), and hot (P = 0.0009, 0.0038, 0.0003) allodynia 17, 21, and 28 days after SNI. d, Experimental design and timeline. e, Nociceptive thresholds under various conditions (n = 8, 5, 6, 6 mice). Daily inhibition of aNB→S1 cholinergic projections in NREM sleep reduces punctate (P = 0.0039, 0.010, 0.0007), dynamic (P = 0.0003, 0.0013, 0.0004), cold (P < 0.0001, = 0.0004, < 0.0001), and hot (P < 0.0001, < 0.0001, < 0.0001) allodynia 14, 21, and 28 days after SNI. f, Experimental design and timeline for chemogenetic inhibition of aNB→S1 projections and dendritic spine imaging in S1. g, Daily inhibition of aNB→S1 projections at ZT2, but not ZT14, reduces SNI-induced increase in dendritic spine elimination (P = 0.0041, 0.0092, > 0.99) and formation (P = 0.0017, 0.0007, 0.34) (n = 6, 5, 5, 5 mice). h, Mechanical thresholds correlate with dendritic spine remodeling in S1 (shading, 95% CI). Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant; by two-sided two-way (b, c, e) or one-way (g) ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test. Detailed statistics in Supplementary Table 1.

To silence aNB→S1 ChAT+ projections specifically during NREM sleep, we expressed Cre-inducible eNpHR3.0-EYFP unilaterally in the aNB of ChATIRES-Cre mice and then implanted 200-μm fiber-optics immediately above L2/3 of S1 to deliver the laser light (Fig. 5d) and EEG/EMG electrodes to monitor the brain states. Post hoc histological analysis revealed that the majority of eNpHR3.0-EYFP+ cells expressed ChAT and that approximately 90% of the total population of ChAT+ cells were eNpHR3.0-EYFP+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 4). From days 1 to 5 after SNI, we performed EEG/EMG recordings in mice and coupled laser light with either NREM or wake states during ZT2–ZT10. The accumulative time of laser ON per day was 36.10 ± 0.91 min during NREM or 34.19 ± 0.66 min during wake (n = 6 mice per group) (Supplementary Fig. 3). When we measured the animals’ pain behaviors over time, we found that optical silencing of aNB→S1 ChAT+ projections during NREM sleep alleviated allodynia (Fig. 5e) and persistent ongoing pain (Extended Data Fig. 2) in SNI mice, while inhibition of aNB→S1 ChAT+ projections during wake had no long-lasting effects on the animal’s pain behaviors. Three weeks after the last session of optical modulation, the nociceptive thresholds of mice treated during NREM were not different from those of sham mice, indicating that silencing aNB→S1 ChAT+ projections during NREM sleep after SNI prevents the formation of chronic pain.

The development of neuropathic pain is accompanied by the structural remodeling of postsynaptic dendritic spines in S1 PNs 18, 49. We examined whether silencing aNB→S1 projections after SNI might prevent dendritic spine remodeling in the S1. Using a similar viral infection scheme as described above, we selectively expressed PSAM4-GlyR in aNB→S1 projection cells for chemogenetic inhibition and examined the dynamics of dendritic spines in the S1 of Thy1-YFP mice that express YFP in L5 PNs (Fig. 5f). Consistent with previous reports 18, 49, we observed a marked increase in dendritic spine formation and elimination over 1 week after SNI in mice that express EGFP (control) in aNB→S1 projections (Fig. 5g). In contrast, in mice expressing PSAM4-GlyR and treated with uPSEM817 at ZT2, we found that SNI had no effects on the rates of spine elimination and formation in the S1. Mice treated with uPSEM817 at ZT14 continued to display elevated rates of spine remodeling after SNI (Fig. 5g). There was a strong correlation between the rates of dendritic spine remodeling in the S1 and the mechanical pain thresholds in mice (Fig. 5h). Collectively, these results indicate that inhibition of aNB→S1 projections during NREM sleep after SNI prevents the hyperactivity and synaptic remodeling of PNs in the S1, as well as the development of chronic pain in mice.

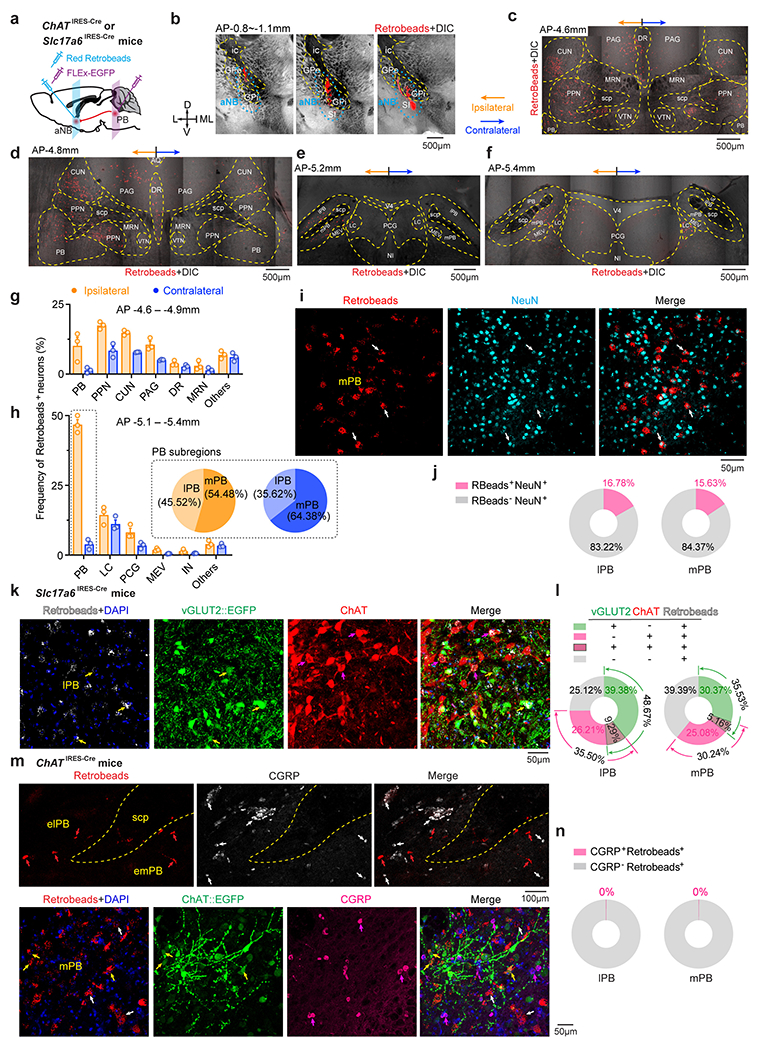

PB inputs drive aNB activation during NREM

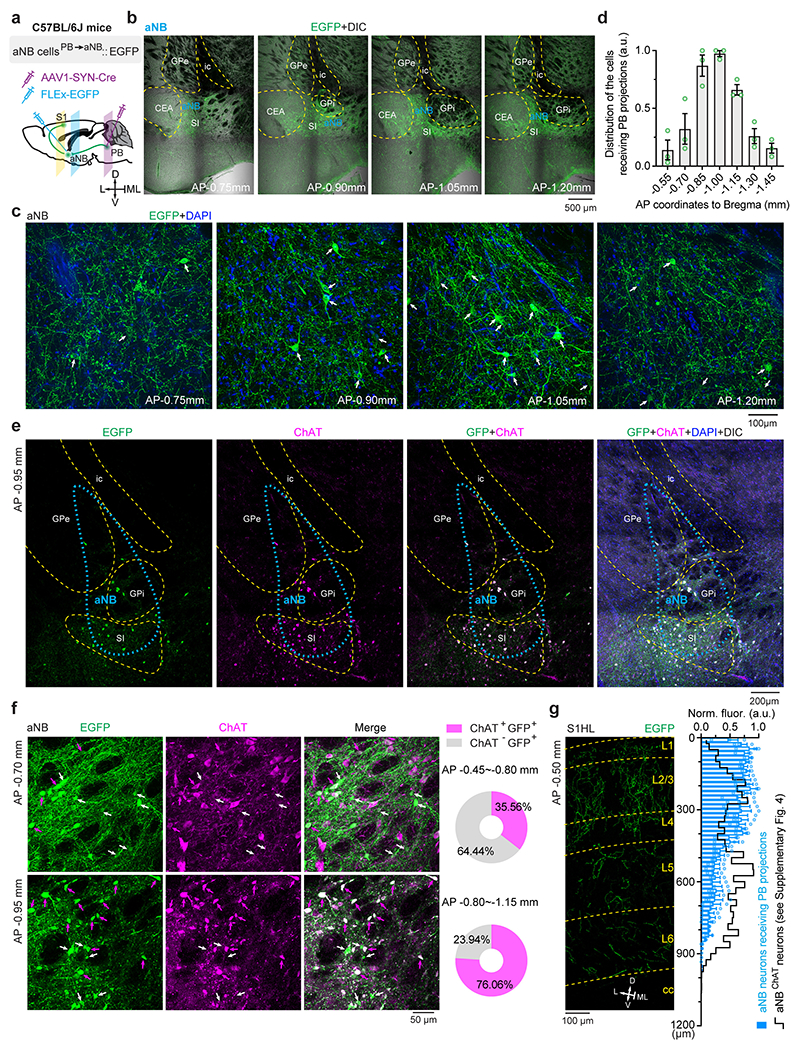

How does peripheral nerve injury cause aNB activation during NREM sleep? The basal forebrain is innervated by inputs from the parabrachial nucleus (PB) 50, 51, a major region of the brain that relays peripheral nociceptive signals 52, 53. PB–basal forebrain connections have been recently implicated in sleep modulation 54. We, therefore, tested whether PB contributes to aNB activation during NREM sleep after SNI. To validate the connections from PB to aNB, we injected red Retrobeads into the aNB and expressed EGFP via a Cre-inducible AAV in the PB of ChATIRES-Cre or Slc17a6IRES-Cre mice (Extended Data Fig. 7a, b). Confocal imaging of PB revealed the colocalization of Retrobeads with ChAT+ and vGLUT2+ neurons (Extended Data Fig. 7c–n), indicating direct PB→aNB projections derived from diverse cell types. To determine whether the postsynaptic neurons in the aNB further project to the S1, we selectively expressed EGFP in the aNB neurons that receive PB projections by injecting AAV1-Cre and Cre-dependent EGFP into the PB and aNB of wildtype mice, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 8a–d). Confocal imaging of aNB showed the colocalization of EGFP with ChAT+ and ChAT− neurons (Extended Data Fig. 8e, f). These EGFP-expressing aNB cells sent intense axon collaterals to L1 and L2/3 of S1 (Extended Data Fig. 8g). Together, these data validate the direct connections of PB→aNB→S1.

We then examined the activity of PB→aNB projection neurons during NREM sleep before and after SNI. We injected AAV2-retro-Cre and Cre-dependent GCaMP6s into the aNB and PB of wildtype mice, respectively, and then implanted a gradient-index (GRIN) lens above the PB to enable Ca2+ imaging in vivo (Fig. 6a). Comparing to pre-SNI, we observed robust activation of PB neurons projecting to aNB during NREM sleep 1–7 days after SNI (Fig. 6b), suggesting that PB may play a role in activating aNB→S1 circuits during NREM sleep in the acute phase of neuropathic pain.

Fig. 6 |. Activation of PB→aNB→S1 circuits during NREM sleep drives the development of chronic pain.

a, Experimental design for in vivo Ca2+ imaging of PB neurons projecting to aNB. b, Representative images of PB→aNB projection neurons expressing GCaMP6s (left; the boxed region shown in the bottom panel), Ca2+ traces (middle), and Ca2+ activity in NREM before and after SNI (right; n = 234 cells from five mice; ****P < 0.0001). c, Experimental design for optogenetic inhibition of PB→aNB projections and Ca2+ imaging of aNB axons in S1. Opto-inhibition was performed during ZT2–10, in wake or NREM, for 5 days following SNI. d, Ca2+ activity of aNB→S1 axonal boutons during wake and NREM 14 days after SNI (n = 123, 105, 103, 110 boutons from three mice per group; wake, P < 0.0001, = 0.0004, 0.0005, 0.0073; NREM, ****P < 0.0001, = 0.014). e, Nociceptive thresholds (mean ± SEM) under various conditions (n = 5 mice per group). Daily inhibition of PB→aNB projections in NREM, but not wake, reduces punctate (NREM vs. SNI, P < 0.0001, = 0.0001, P < 0.0001), dynamic (P = 0.0001, < 0.0001, < 0.0001), cold (P = 0.0003, < 0.0001, = 0.0022), and hot (P = 0.0004, 0.0002, 0.0012) allodynia 14, 21, and 28 days after SNI. f, Representative two-photon images of DRG neurons expressing GCaMP6s (left), Ca2+ traces in NREM (middle), and Ca2+ activity before and after SNI (n = 140 cells from four mice; ****P < 0.0001). In b, d, f, box plot bounds and center, quartiles and median; whiskers, min and max. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant; by two-sided Friedman’s test followed by Dunn’s test (b, f), Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (d), two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test (e). Detailed statistics in Supplementary Table 1.

To test this, we first performed in vivo Ca2+ imaging in aNB→S1 projection terminals while optogenetically silencing PB→aNB projections. Specifically, we injected AAV2-retro-Cre and Cre-dependent axon-targeted GCaMP6s into the aNB and simultaneously injected Cre-dependent eNpHR3.0-EYFP into the PB of wildtype mice (Fig. 6c). This injection scheme allows the axonal expression of GCaMP6s in aNB neurons and selective expression of eNpHR3.0 in the PB cells projecting to aNB. We found that acute photoinhibition of PB→aNB projections dose-dependently decreased axonal Ca2+ activity in the aNB cells projecting to the S1 (Extended Data Fig. 9a–c). Next, we coupled laser light with NREM or wake states during the rest phase, 8 h per day (ZT2–ZT10), for a total of 5 days following SNI (Supplementary Fig. 3). Fourteen days after SNI (i.e., 9 days after the last optogenetic session), in vivo imaging was performed in L2/3 of S1 where Ca2+ signals in axonal terminals of aNB neurons were visualized. We found that in SNI mice expressing eNpHR in the PB, light paired with NREM sleep significantly reduced Ca2+ activity in aNB→S1 projection terminals as compared to SNI mice expressing EYFP in the PB, whereas light paired with wake had no effects on SNI-induced elevation of Ca2+ activity in aNB→S1 projection terminals (Fig. 6d). These results indicate that silencing PB→aNB projection neurons during NREM sleep prevents the activation of aNB→S1 projections after SNI.

Behaviorally, photoinhibition of PB→aNB projection neurons during NREM sleep, rather than wake, alleviated allodynia (Fig. 6e) and ongoing pain (Extended Data Fig. 2) in mice after SNI. Consistently, using the design resembling the optogenetic experiments above, chemogenetic inhibition of PB→aNB projection neurons during the rest phase, but not the active phase, also prevented aNB axonal hyperactivity in the S1 and restored nociceptive thresholds in SNI mice (Extended Data Fig. 9d–g). Together, these results indicate that increased PB→aNB inputs during NREM sleep contribute to the hyperexcitability of aNB→S1 projections in neuropathic pain.

Finally, we assessed whether the activation of PB during NREM sleep is due to increased nociceptive inputs from injured peripheral nerves. Using a newly developed imaging technique 55, we performed Ca2+ imaging of primary sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) of Thy1-GCaMP6s mice before and after SNI during NREM sleep. We found that the spontaneous Ca2+ activity of DRG neurons during NREM sleep was significantly higher within one day after SNI compared to pre-SNI and continued to increase over the next one week (Fig. 6f). Importantly, blockade of DRG sensory neuron activity by local application of lidocaine to the nerve injury site significantly decreased Ca2+ activity in PB neurons during NREM sleep (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results indicate that activation of PB during NREM sleep is caused by the increased spontaneous firing of primary sensory neurons after nerve injury.

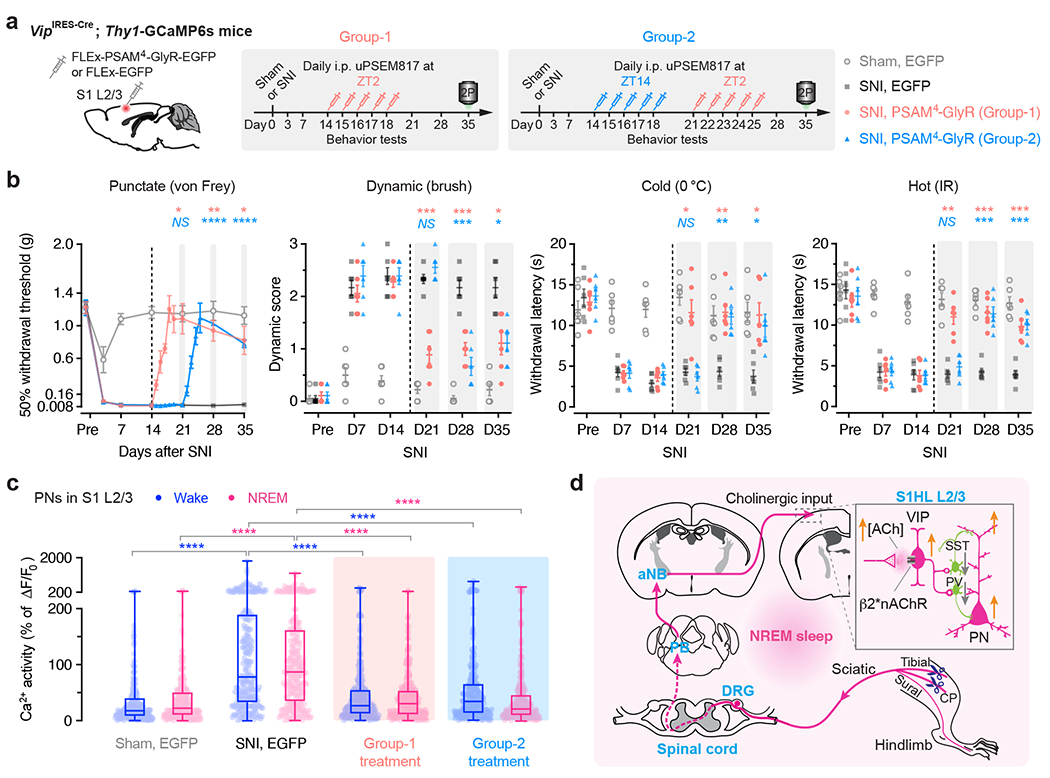

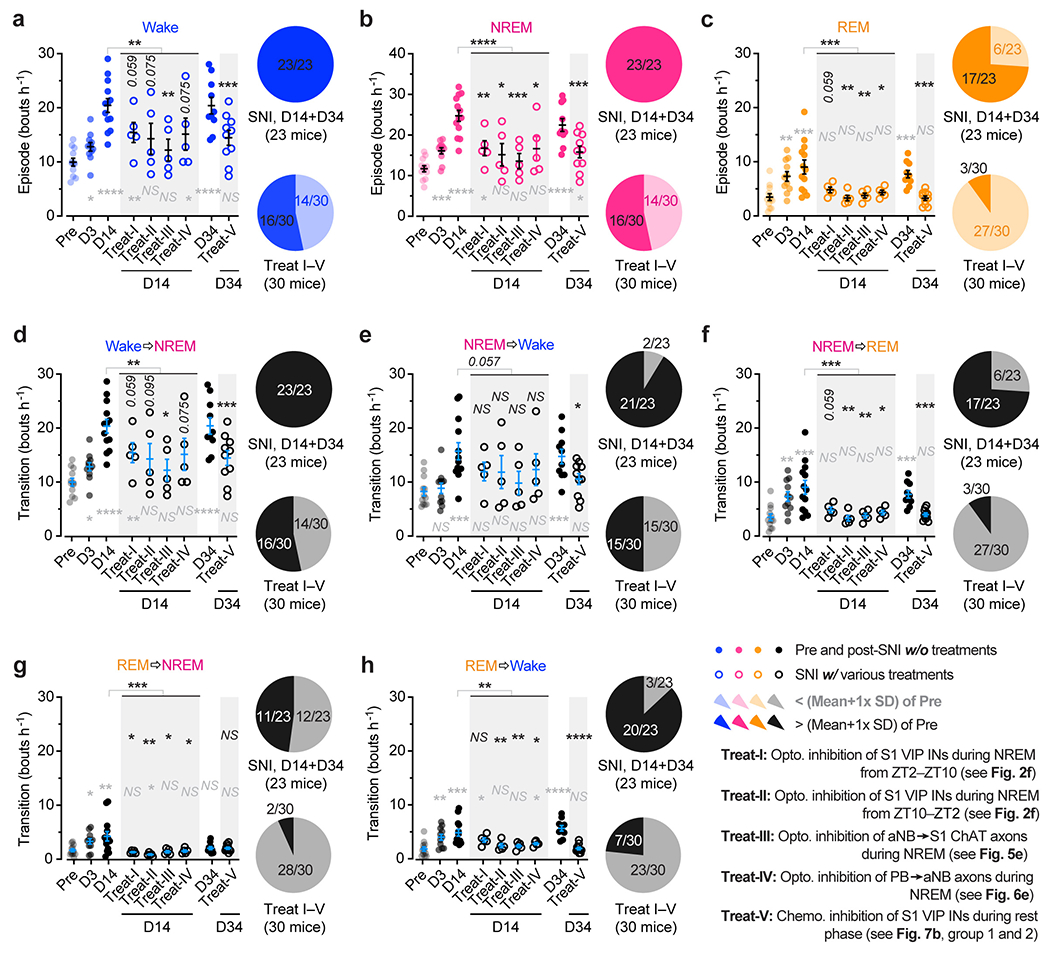

Targeting sleep phase to reverse established chronic pain

The results above demonstrate the beneficial effects of silencing PB–aNB–S1 circuits during sleep in preventing the formation of chronic pain. However, whether this sleep-specific circuit modulation could effectively reverse established chronic pain symptoms remains unknown. To test this possibility, we chemogenetically inhibited S1 VIP INs during the sleep phase in mice with chronic neuropathic pain and measured the animals’ pain behaviors over time (Fig. 7a). For these experiments, mice expressing PSAM4-GlyR in S1 VIP INs were injected uPSEM817 at ZT2 or ZT14 starting at 14 days after SNI. We found that daily uPSEM817 injection at ZT2 for 5 consecutive days was sufficient to alleviate allodynia (Fig. 7b) and ongoing pain (Extended Data Fig. 2) in SNI mice as compared to saline-treated controls. In contrast, uPSEM817 injections at ZT14 had no effects on the established pain behaviors.

Fig. 7 |. The sleep phase-targeted VIP inhibition reverses the established chronic neuropathic pain.

a, Experimental design and timeline for chemogenetic inhibition of S1 VIP INs expressing PSAM4-GlyR, behavioral testing, and in vivo Ca2+ imaging. Mice in Group-1 were injected uPSEM817 daily at ZT2 from days 14 to 18 after SNI. Mice in Group-2 were first injected at ZT14 from days 14 to 18, then at ZT2 from days 21 to 25. b, Nociceptive thresholds (mean ± SEM) under various conditions (n = 6 mice per group). Daily inhibition of VIP INs at ZT2, but not ZT14, in the chronic phase of neuropathic pain reduces allodynia in mice. Group-1 vs. SNI for day 21, 28, 35: punctate, P = 0.017, 0.0057, 0.042; dynamic, P = 0.0004, 0.0007, 0.029; cold, P = 0.028, 0.0020, 0.015; hot, P = 0.0011, 0.0002, 0.0096. Group-2 vs. SNI for day 21, 28, 35, punctate, P = 0.99, < 0.0001, < 0.0001; dynamic, P = 0.88, 0.0004, 0.011; cold, P = 0.99, 0.0013, 0.031; hot, P = 0.99, 0.0007, 0.0002. c, PN Ca2+ activity 35 days after SNI (n = 237, 255, 272, 254 cells from four mice per group; box bounds, quartiles and median; whiskers, min and max; ****P < 0.0001 vs. SNI). d, Schematic summary. Due to increased firing of DRG sensory neurons after nerve injury, ChAT+ neurons in aNB receive elevated inputs from PB during NREM sleep and, in turn, excite VIP INs in S1 to cause disinhibition of PNs and sustained pain sensations. Activation of PB–aNB–S1 circuits during NREM sleep is crucial for the development and maintenance of chronic pain. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant; by two-sided two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test (b) or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (c). Detailed statistics in Supplementary Table 1.

Interestingly, when mice in the ZT14 group were subsequently administered uPSEM817 at ZT2 for another 5 days (Fig. 7a), allodynia (Fig. 7b) and ongoing pain (Extended Data Fig. 2) were reversed, indicating the importance of sleep-targeted inhibition of VIP neurons in treating chronic pain. Ten to 17 days after the last uPSEM817 injection at ZT2 (35 days post-SNI), the nociceptive thresholds of SNI mice remained comparable with those of sham mice. When we measured Ca2+ activity in S1 PNs, we found that inhibition of VIP INs during the sleep phase abolished SNI-induced PN hyperactivation (Fig. 7c). These results demonstrate that inactivating S1 in sleep reverses established chronic pain features at the cellular and behavioral level.

Discussion

Despite the prevalence of neuropathic pain, there is limited understanding of how the pain pathway is persistently modified after peripheral nerve injury, leading to persistent pain sensations 8, 9, 17–20. Moreover, while chronic pain is highly comorbid with sleep disorders 4, 5, how sleep contributes to pain chronicity remains unclear. Here we show that due to the increased spontaneous firing of primary sensory neurons after nerve injury, the hyperactivation of PB–aNB–S1 circuits during NREM sleep, but not wakefulness, plays a pivotal role in the development and maintenance of chronic pain (Fig. 7d).

Previous studies have shown that basal forebrain cholinergic neurons are primarily activated during arousal and movement in awake rodents but not during NREM sleep 37, 44, 56, 57. Following nerve injury, our findings indicate that cholinergic neurons in the aNB are abnormally activated during NREM sleep, increasing ACh release in the S1. This enhanced cholinergic input drives the activity of VIP INs, mainly through β2*nAChRs, resulting in PN hyperactivation in the S1. As sleep is essential for promoting neuronal plasticity associated with learning and memory consolidation 24–27, the increased activation of S1 neurons during NREM sleep likely facilitates the persistent remodeling of the somatosensory cortex, which is vital for the maintenance of chronic pain. Together, our findings underscore the critical function of basal forebrain activation during sleep in promoting synaptic and neuronal circuit plasticity in the mouse model of peripheral neuropathic pain. In the future, it would be interesting to investigate whether the basal forebrain is also abnormally active during sleep in patients with chronic pain.

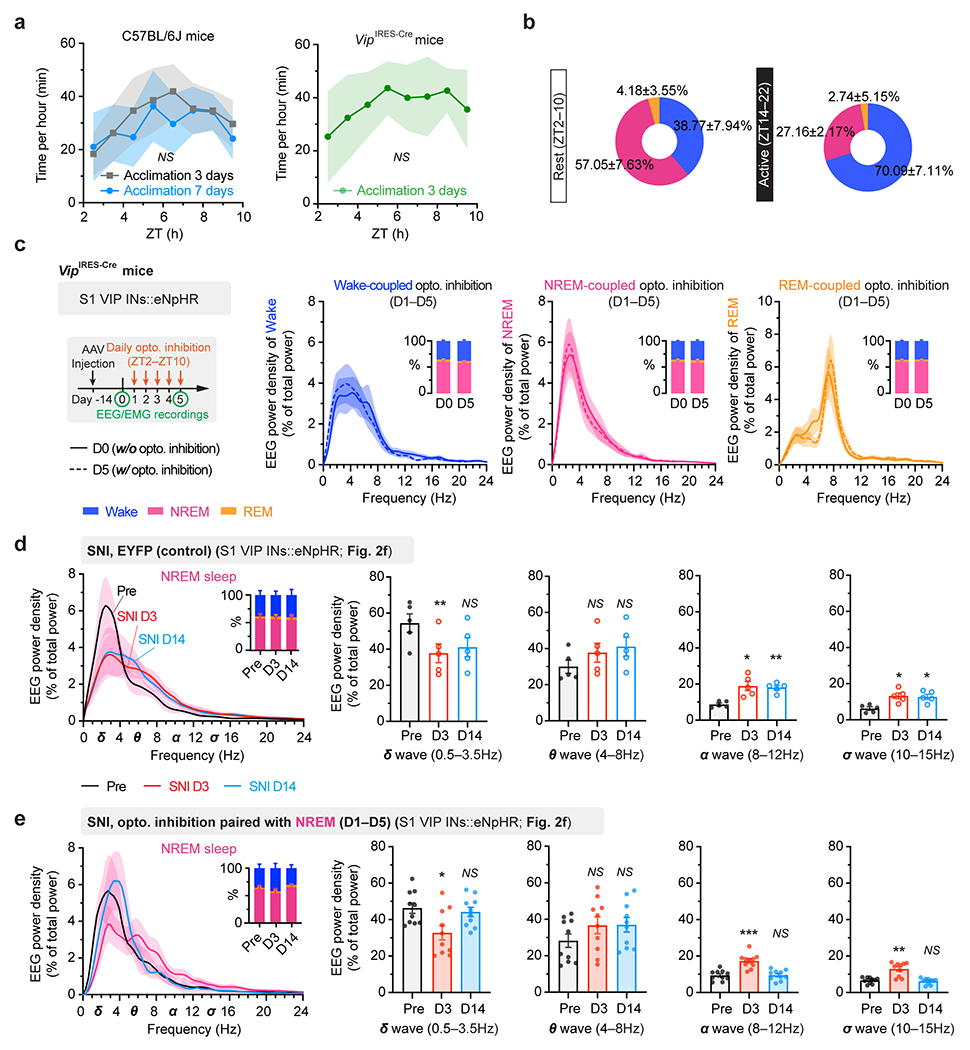

Our studies show that the activation of cholinergic neurons in the aNB during NREM sleep is driven by the inputs from PB in mice with neuropathic pain. The activation of PB neurons during NREM sleep is caused by the increased spontaneous firing of DRG sensory neurons after axotomy. Notably, both PB and basal forebrain are involved in sleep regulation 58, 59. Previous studies have suggested that the projections from PB to aNB contribute to the maintenance and transition of brain states under various conditions, including arousal 60, 61, whereas perturbations of basal forebrain cholinergic neuronal activity cause disruptions in the sleep-wake cycle 58, 62. Thus, besides its role in initiating S1 plasticity and persistent pain, increased activation of the PB–aNB circuit after peripheral nerve injury may also contribute to sleep disruption. Indeed, while sleep macrostructure appears unaltered, mice with neuropathic pain show increased EEG power in the α (8–12 Hz) frequency spectrum (Extended Data Fig. 3) and more frequent arousals during NREM sleep (Extended Data Fig. 10), which is in line with prior reports in patients with chronic pain 63 and animal models 64. Furthermore, inhibiting PB–aNB–S1 in SNI mice reduces sleep fragmentation and restores EEG power distribution (Extended Data Fig. 3 and 10), suggesting the involvement of this circuit in neuropathic pain-related sleep disturbances. Future studies are needed to investigate the impact of the abnormal activity in the PB–aNB pathway on sleep to better understand the comorbidity of chronic pain and sleep disruption.

Our data highlight the sleep phase as the preferred timing for neuropathic pain intervention. Targeting the PB–aNB–S1 circuit, we have selectively inhibited different neuronal populations at specific timing (rest vs. active phase; sleep vs. wake) using chemo- and optogenetic approaches. In all cases, we find that neuronal inhibition during the rest phase or NREM sleep is maximally effective in achieving sustained pain relief, even in mice with established chronic neuropathic pain. It is important to note that the aNB also receives noxious inputs from the central amygdala 51, 65, and the PB also sends outputs to other projection targets outside the aNB 52. Thus, the formation and maintenance of chronic pain could involve sleep-dependent neural plasticity in other pain-processing regions as well. At present, we do not know how sleep-associated neuronal activation encodes chronic pain memory in the neural network. We also do not know whether sleep alterations per se contribute to sustained cholinergic inputs leading to VIP neuronal activation in sleep. Nevertheless, our findings converge with prior work in other systems (e.g., visual, motor), where sleep-dependent reactivation of learning-activated neuronal ensembles is critical for memory consolidation, and inhibition of neuronal ensembles during post-learning sleep disrupts the consolidation of the new information into stable memory (reviewed in 24, 66).

In summary, our study uncovers a sleep-active PB–aNB–S1 pathway that is important for the development and maintenance of chronic neuropathic pain and suggests the prospect of developing time-controlled pain treatment approaches.

Methods

Animals

Transgenic mice expressing GCaMP6 slow in L2/3 pyramidal neurons (PNs), Thy1-GCaMP6s founder line 3, were described previously 67. Thy1-YFP-H mice (Jackson Laboratory; Stock No: 003782) were used for dendritic spine imaging experiments. AAV experiments were conducted with mice purchased from the Jackson Laboratory: C57BL/6J (Stock No: 000664), VipIRES-Cre (Stock No: 010908) 68, VipIRES-FLPo (Stock No: 028578) 69, SstIRES-Cre (Stock No: 013044) 68, PvalbT2A-Cre (Stock No: 012358) 70, PvalbT2A-FLPo (Stock No: 022730) 70, ChATIRES-Cre (Stock No: 006410) 71, Slc17a6IRES-Cre mice (i.e., Vglut2IRES-Cre; Stock No: 016963) 72, and Rosa26-LSL-Cas9-EGFP mice (Stock No: 026175) 73. All transgenic lines were backcrossed to the C57BL/6J background. Mice were group-housed in temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms on a 12-h light-dark cycle (light: ZT0–12; dark: ZT12–24) and were randomly assigned to different treatment groups. Two- to 3-month-old animals of both sexes were used, and the mouse sex information is listed in Supplementary Table 2. As no significant differences were observed between male and female mice, data from both sexes were grouped for analysis. All experiments were carried out according to protocols approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in line with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The experimenters were blinded to treatment groups.

Viruses

Recombinant AAV viral vectors were obtained from Addgene unless otherwise noted. Aliquoted AAVs were stored at −80 ºC, thawed on ice, and centrifuged before use. AAVs were stereotaxically injected into the targeted brain region using a picospritzer (5 p.s.i., 12 ms pulse width, 0.3–0.4 Hz) at a speed of ~10–15 min per 0.1 μl, allowing another 10–15 min to spread at the injection site before withdrawing the glass micropipette. The coordinates for viral injections were as follows unless otherwise stated: L2/3 of S1 (anterior-posterior (AP) −0.5 mm, midline (ML) 1.7 mm, subpial (SP) 150 μm), aNB (AP −0.95 mm, ML 2.1 mm, SP 4.7 mm), PB (AP −5.2 mm, ML 1.25 mm, SP 2.6 mm). Viruses were injected into the S1, aNB, or PB within the same hemisphere of brain at least two weeks before experiments.

The titer (genome copies per ml, gc ml−1) and catalog number for each vector were as follows. AAV5-SYN-FLEx-Axon-GCaMP6s (1.5×1013 gc ml−1; Stock No. 112010), AAV1-CAG-FLEx-mRuby2-GSG-P2A-GCaMP6s (1.8×1013; 68717), AAV1-SYN-FLEx-NES-jRGECO1a (2.4×1013; 100853), AAV9-SYN-FLEx-GCaMP6s (2.1×1013; 100845), AAV8-EF1a-fDIO-GCaMP6s (2.2×1013; 105714) AAV1-CaMKII0.4-Cre (1.6×1013; 105558), AAV9-CaMKII0.4-Cre (2.1×1013; 105558), AAV1-SYN-Cre (2.6×1013; 105553), AAV9-EF1a-fDIO-Cre (2.5×1013; 121675), AAV2-retro-PGK-Cre (9.3×1012; 24593), AAV2-retro-EF1a-fDIO-Cre (9.14×1012; 121675), AAV1-EF1a-FLPo (7.84×1012; 55637), AAV2-retro-EF1a-FLPo (1.1×1013; 55637), AAV1-EF1a-fDIO-mCherry (1.6×1013; 114471), AAV9-EF1a-DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP (3.9×1013; 26966), AAV9-SYN-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry (2.7×1013; 44362), AAV9-SYN-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry (2.1×1013; 44361), AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-IRES-EGFP (2.0×1013; 119741), AAV9-FLEx-tdTomato (3.8×1013; 28306), AAV1-CAG-FLEx-EGFP (2.1×1013; 51502), and AAV9-EF1a-DIO-EYFP (2×1013; 27056). AAV5-SYN-fDIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry (5.2×1012; 1011; Canadian Neurophotonics Platform Viral Vector Core Facility; RRID: SCR_016477). AAV1-FLEx-SaCas9-U6-sgSlc32a1 (2.0×1013; 159905) and AAV1-FLEX-SaCas9-U6-sgRNA-scramble (2.0×1013; 124844) 47 were produced by Virovek (Hayward, CA, USA). AAV2/1-CAG-FLEx-iAChSnFR (3.4×1013; inventor code X513 v6) 43 was a gift from Dr. Loren Looger’s laboratory at Janelia Research Campus. AAV5.2-U6-β2-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry (2.28×1013; 128343), AAV5.2-U6-α7-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry (2.04×1013; 128342) and AAV5.2-U6-control-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry (2.26×1013; 128347) 45 were gifts from Dr. Ryan Drenan’s laboratory at Wake Forest University.

Spared nerve injury

Spared nerve injury (SNI) or sham operation was performed under sterile conditions 74. Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 100 mg kg−1 ketamine and 15 mg kg−1 xylazine (Covetrus). A skin incision (~2–3 mm) was made in the thigh, where the tibial and common peroneal branches of the sciatic nerve were ligated and cut, leaving the sural nerve intact. Muscle and skin were closed and sutured in two layers. The sciatic nerve was exposed for sham operation but not ligated or cut.

Surgical preparation for in vivo imaging

To prepare a thinned-skull window for chronic imaging in the S1 75, mice were deeply anesthetized and a head frame was attached to the animal’s skull surface with glue (Loctite 495) and dental cement (Metabond; Parkell). A small skull region above the S1 (AP −0.5 mm and ML 1.6–1.8 mm) was thinned to ~30 μm in thickness. A round coverslip (No. 0 glass) was tightly glued onto the thinned skull for protection during chronic imaging. Before imaging, mice were habituated three times (10 min each time) in the imaging platform to minimize the potential stress associated with head restraining and imaging.

To image neurons in the PB, a gradient-index (GRIN) lens of 0.5 mm in diameter and 6.049 mm in length (CLHS050GFT039; Go!Foton) was implanted above the PB following the attachment of the head frame. A custom-made needle (maximum diameter 0.5 mm) with a blunt tip was slowly inserted (~10 min mm−1) using a stereotaxic apparatus into brain tissues at AP −5.25 mm, ML 1.25 mm, SP 2.5 mm, and maintained for 20 min. Following the needle withdrawal, a GRIN lens was slowly inserted through the tunnel to the same depth. The exposed end was glued to the skull and protected with a plastic cap. Buprenorphine (0.1 mg kg−1, i.p.) was administered for 3 days to provide post-surgical analgesia. Animals recovered for at least 14 days before experiments began.

To image primary sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) of awake mice, a vertebral window was implanted as previously described 55. Imaging took place 1 week after vertebral window implantation.

EEG/EMG recordings and analysis

An electrocorticographic (EEG) and electromyographic (EMG) recording headstage (~0.12 g in weight) was implanted together with the cranial or vertebral window to determine the animals’ brain states during imaging. The headstage was custom-made by soldering a miniature multichannel connector to four electrodes, two for EEG and two for EMG recordings. Two small areas of the skull (~0.5 mm in diameter; ~0.5 mm in between) close to lambda and midline were thinned using a high-speed drill, through which EEG electrodes were inserted, touching the dura mater, and fixed in place using glue and dental cement. EMG electrodes were placed in the nuchal muscles.

Before recording sessions, mice were acclimated to the recording system (BL-420, v2.1) for 3 days (2 h per day) to ensure normal sleep expression (Extended Data Fig. 3a). During in vivo two-photon imaging, EEG and EMG signals were simultaneously recorded and analyzed post hoc to determine the brain states corresponding to each imaging session. For recording in freely moving mice, mice were habituated to the recording device for another 2 h before the signal collection. EEG and EMG signals were amplified 500 times at a sampling frequency of 5 kHz. EEG data were analyzed using fast Fourier transform (FFT) (matplotlib.mlab.specgram in Python), the spectrum of EEG waveform was generated with a 0.1-s sampling bin width and a 16384 (i.e. 214) FFT size (NFFT) using the Hanning window. The frequency resolution of the spectrum was 0.3052 Hz. In the EEG spectrogram (Fig. 1b), spectrum power values were generated between 0 and 30 Hz and normalized to the peak in each sampling bin. EEG power density at different frequencies was normalized to the total power in the respective state (wake, NREM, or REM) (Extended Data Fig. 3c–e).

Ca2+ and ACh imaging and data analysis

The genetically-encoded Ca2+ indicators GCaMP6s and jRGECO1a were used for in vivo Ca2+ imaging. A genetically-encoded acetylcholine sensor iAChSnFR 43 was used for in vivo acetylcholine (ACh) imaging. Thy1-GCaMP6s mice were used for Ca2+ imaging of pyramidal neurons (PNs) in the S1 and primary sensory neurons in the DRG. For Ca2+ imaging of interneurons (INs), 0.2 μl AAV9-SYN-FLEx-GCaMP6s was injected into L2/3 of S1 of VipIRES-Cre, SstIRES-Cre, and PvalbT2A-Cre mice. In some experiments, AAV1-CAG-FLEx-mRuby2-GSG-P2A-GCaMP6s or AAV1-SYN-FLEx-NES-jRGECO1a were used for VIP Ca2+ imaging. To image Ca2+ in aNB→S1 cholinergic axons, 0.1 μl AAV5-SYN-FLEx-Axon-GCaMP6s was injected into the aNB of ChATIRES-Cre mice. To image Ca2+ in PB→aNB projection neurons, 0.1 μl AAV2-retro-PGK-Cre was injected into the aNB, and 0.1 μl AAV9-SYN-FLEx-GCaMP6s was injected into the PB of C57BL/6J mice. Seven to 10 days after that, a GRIN lens was implanted ~100 μm above the PB for in vivo imaging. To image ACh in the S1, 0.15 μl AAV2/1-CAG-FLEx-iAChSnFR was injected into L2/3 of S1 of VipIRES-Cre mice.

In vivo imaging was performed using a Scientifica two-photon system equipped with a Ti: Sapphire laser (Vision S, Coherent) tuned to 920 nm. For Ca2+ imaging in the S1, images were collected at a depth of 200–350 μm below the pial surface for detecting somas of L2/3 PNs, 150–300 μm for detecting somas of L2/3 INs, and ~150 μm for detecting long-range projecting axons, respectively. For Ca2+ imaging in the PB through GRIN lenses, images were collected at 200–500 μm below the lens surface of the tissue-contacting end. For Ca2+ imaging of primary sensory neurons, images were collected at 100–300 μm below the surface of DRG. Time-lapse imaging was performed at one focal plane for longitudinal comparison in each animal. All the experiments were performed using a 25× objective (1.05 N.A.) immersed in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF), with a digital zoom of 1× for DRG neurons, 1.2 or 1.5× for cortical INs, 2 or 2.5× for cortical PNs, and 4× for axons. All images were acquired at a frame rate of 1.69 Hz (2-μs pixel dwell time) at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels. Image acquisition was performed using ScanImage software (v5.4; Vidrio Technologies). Imaging with excessive movement were removed from analyses.

Imaging data were analyzed using CaImAn 76 (Python version 1.9.12; released on Github.com). This automated analysis pipeline was used to correct the motion of raw image series (using NoRMCorre algorithm 77), identify the active somas/axonal boutons on a statistical basis, calculate ΔF/F0 [i.e. (F – F0)/F0 × 100%, where F0 is the baseline fluorescence], deconvolute ΔF/F0 signals, and generate the analysis reports. For Ca2+ imaging, active somas/boutons were defined as the morphologically constrained regions of interest (ROIs) with at least one Ca2+ event during the 142-s imaging session. A segment of the temporal sequence of an ROI was accepted as a Ca2+ event only if its average ΔF/F0 was more than 1.5× signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) above baseline ΔF/F0 and lasted longer than 0.9 s. 1.5× SNR was chosen empirically based on manual proofreading. The mean and SNR of baseline ΔF/F0 were estimated by a 60-frame (~36 s) iterative window. The activity events were extracted by temporal deconvolution of ΔF/F0 signals based on the improved fast non-negative deconvolution method 78, 79. The figures show original views of fluorescent somas/boutons and active ones automatically extracted by CaImAn for comparison.

Dendritic spine imaging and data analysis

Thy1-YFP-H mice were used for imaging dendritic spines of L5 PNs in the S1 through a thinned-skull window. Dendritic spine dynamics were quantified using NIH ImageJ software (Fiji 2.3.0/1.53s) as previously described 80, 81. For each dendritic segment analyzed, filopodia were identified as long, thin protrusions with a ratio of head to neck diameter < 1.2:1 and a ratio of length to neck diameter > 3:1. The remaining protrusions were classified as spines. A total of more than 150 spines were analyzed per animal. Spine formation or elimination rates were measured as the number of spines formed or eliminated between two views divided by the number of spines existing in the first view.

Chemogenetic manipulation

For VIP inhibition, 0.2 μl AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP 32 or AAV1-CAG-FLEx-EGFP (control) was injected into L2/3 of S1 of VipIRES-Cre mice.

To validate the acute effects of activating PSAM4-GlyR on VIP neuron activity (Supplementary Fig. 1), a 0.2 μl mixture (volume ratio 1:1) of AAV1-SYN-FLEx-NES-jRGECO1a and AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP was injected into L2/3 of S1 of VipIRES-Cre mice. To determine the effect of VIP inhibition on SST activity (Extended Data Fig. 1c, d), a 0.2 μl mixture (1:1:1) of AAV5-SYN-fDIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry, AAV8-EF1a-fDIO-GCaMP6s and AAV9-SYN-FLEx-GCaMP6s was injected into the S1 of SstIRES-Cre; VipIRES-FLPo mice. This design allows simultaneous Ca2+ imaging of VIP and SST INs during clozapine N-oxide (CNO)-mediated DREADD 82 inhibition of VIP INs. To examine SST activity after daily inhibition of VIP INs (Extended Data Fig. 1e), a 0.2 μl mixture (1:1) of AAV5-SYN-fDIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry and AAV9-SYN-FLEx-GCaMP6s was injected into the S1 of SstIRES-Cre; VipIRES-FLPo mice. To determine the effects of VIP inhibition on PV activity (Extended Data Fig. 1f–h), a 0.2 μl mixture (1:1) of AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP and AAV8-EF1a-fDIO-GCaMP6s was injected into the S1 of PvalbT2A-FLPo; VipIRES-Cre mice.

To inhibit aNB→S1 projection neurons, 0.2 μl AAV2-retro-PGK-Cre was injected into L2/3 of S1, and 0.2 μl AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP or AAV1-CAG-FLEx-EGFP was injected into the aNB of C57BL/6J mice. To inhibit aNB→S1 projection neurons and image Ca2+ in S1 PNs and VIP INs, a 0.2 μl mixture (volume ratio 1:5) of retrograde AAVs encoding FLP (AAV2-retro-EF1α-FLPo) and AAV1-CAG-FLEx-mRuby2-GSG-P2A-GCaMP6s was injected into L2/3 of S1; 0.2 μl mixture (1:5) of AAV9-EF1α-fDIO-Cre and AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP was injected into the aNB of VipIRES-Cre ; Thy1-GCaMP6s mice. To inhibit aNB→S1 projection neurons and examine dendritic spine dynamics in the S1, 0.2 μl AAV2-retro-PGK-Cre was injected into the S1, and 0.2 μl AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP or AAV1-CAG-FLEx-EGFP (control) were injected into the aNB of Thy1-YFP-H mice.

To delete Chrnb2 or Chrna7 in S1 VIP INs and activate aNB→S1 projection neurons (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b), 0.15 μl mixture (volume ratio 2:1) of AAV9-SYN-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry and AAV9-EF1a-fDIO-Cre were injected into the aNB, and 0.2 μl mixture (3:1) of AAVs encoding sgRNA (or scrambled sequences) and AAV2-retro-EF1α-FLPo were injected into the S1 of VipIRES-Cre; Ai162; LSL-Cas9-EGFP mice. This scheme of AAV injections allows examining Ca2+ activity in S1 VIP INs in response to DREADD activation of aNB→S1 projection neurons. Notably, both EGFP and GCaMP6s were expressed in VIP INs, resulting in a higher F0 and a lower ΔF/F0, but the relative changes in ΔF/F0 still inform the changes in VIP activity.

To inhibit PB→aNB projection neurons, 0.1 μl AAV2-retro-PGK-Cre was injected into the aNB, and 0.1 μl AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP or AAV1-CAG-FLEx-EGFP (control) was injected into the PB of C57BL/6J mice. To inhibit PB→aNB projection neurons and image Ca2+ in aNB→S1 axons, 0.1 μl mixture (volume ratio 1:5) of AAV2-retro-EF1α-fDIO-Cre and AAV5-SYN-FLEx-Axon-GCaMP6s was injected into the aNB, and 0.1 μl mixture (1:5) of AAV5-SYN-FLEx-PSAM4-GlyR-EGFP and AAV1-EF1α-FLPo was injected into the PB of C57BL/6J mice. AAV2-retro not only infected the cells in the injection site but also retrogradely infected the projection cells in other regions 48. This scheme of AAV injections allows imaging of the aNB→S1 projection terminals derived from the aNB neurons receiving inputs from PB (Extended Data Fig. 9).

For chronic inhibition experiments, mice expressing PSAM4-GlyR were administered 0.3 mg kg−1 ligand uPSEM817 (6866; Tocris) i.p. daily, at either ZT2 or ZT14, from days 1 to 5 after SNI or sham surgery. For validating the acute effect of activating PSAM4-GlyRs on VIP INs in naïve mice (Supplementary Fig. 1), 0.3 mg kg−1 uPSEM817 or saline was injected i.p. at ZT4. For other acute inhibition experiments, 0.3 mg kg−1 uPSEM817 or saline was injected i.p. at ZT4 on day 3 after SNI. For acute manipulation, mice expressing DREADD-hM3D(Gq) or -hM4D(Gi) receptors were injected i.p. with 5 mg kg−1 CNO (C0832; Sigma-Aldrich); for chronic inhibition, mice expressing hM4D(Gi) were injected 2 mg kg−1 CNO at ZT2 from days 1 to 5 after SNI.

Optogenetic manipulation

To inhibit S1 VIP INs, 0.2 μl AAV9-EF1α-DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP was injected into the S1 of VipIRES-Cre mice. To inhibit aNB→S1 cholinergic axons, 0.15 μl AAV9-EF1α-DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP was injected into the aNB of ChATIRES-Cre mice. To inhibit PB→aNB axons, a 0.15 μl mixture (volume ratio 5:1) of AAV9-EF1α-DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP or DIO-EYPF (control) and AAV1-SYN-Cre was injected into the PB. Seven to 10 days after virus injections, a custom-prepared cannula was slowly inserted through the skull to the designated depth (for silencing VIP INs and aNB→S1 axons in the S1, SP 80–100 μm; for PB→aNB axons in aNB, SP 4.4–4.5 mm) led by a stereotaxic apparatus. The animals recovered for at least 1 week before the experiment began.

During optogenetic experiments, a 595 nm laser (~5 mW mm−2 in power) was generated by a fiber-coupled LED (M595F2; ThorLabs) triggered by a TTL pulse generator (OTPG-4; Doric Lenses) programmed in Doric Neuroscience Studio software (Doric Lenses). The laser light was manually turned on/off by experienced researchers based on the real-time EEG/EMG signals to pair optical modulation with different brain states. Following the transition of brain states, the laser light was turned on/off based on ~5–10 s epochs. The laser pulse with 5 s ON and 35 s OFF (0.025 Hz) was delivered during NREM sleep or wake, and 5 s ON and 5 s OFF (0.1 Hz) during REM sleep. For optical modulation during NREM sleep in the rest phase, the session started at ZT2 and ended at ZT10. The accumulative time of laser ON from ZT2 to ZT10 was ~34 min per daily session (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the wake modulation group, a similar number of laser pulses was applied at the same frequency during wakefulness. As mice spent less time awake in the rest phase, the optical modulation ended around ZT11 or 12, allowing the same number of laser pulses to be delivered. Optical modulation during REM sleep was performed during ZT2 to ZT10. As the total time of REM sleep was ~20 min during this period, we applied a higher frequency of laser pulses. The accumulative time of laser ON during REM sleep was ~7 min per day (Supplementary Fig. 3). For sham and SNI mice expressing EYFP (control) without eNpHR3.0, the same frequency and total time of laser ON (~34 min) were applied during NREM sleep. In a separate experiment, the same amount of laser ON (~34 min per daily session) was applied during NREM sleep from ZT10 to ZT2 to examine the involvement of circadian timing in the development of chronic pain.

To image aNB→S1 axons during acute optogenetic inhibition of PB→aNB projections, a low-profile cannula was implanted at 66.7° angle horizontally (to avoid obstruction to the 25X objective during imaging) to reach the site (AP −0.95 mm, ML −2.1 mm, SP 4.4 mm) above the aNB. In Extended Data Fig. 9b, c, a single light pulse with 5 s-, 10 s- or 20 s-duration was delivered to characterize the responses of axonal Ca2+ in the S1. For all the optogenetic experiments, the output of the LED laser was tuned to ensure the working power of ~160 μW (~5 mW mm−2) at the tip of fiber-optics, which was adjusted individually for each custom-prepared cannula before implantation.

Pharmacological inhibition of AChRs

To locally inhibit β2 subunit-containing (β2*) or α7 subunit-containing (α7*) nAChRs, 0.15 μl DHβE (1 μM), methyllycaconitine (MLA, 10 nM) or vehicle (ACSF) was injected into the S1 (AP −0.5 mm, ML 1.7 mm, SP 100 μm), once per day, at either ZT2 or ZT14, for 5 consecutive days following SNI or sham surgery. To locally inhibit muscarinic AChRs (mAChRs), 0.15 μl pan-mAChR antagonist scopolamine (20 μM) was injected. To locally inhibit M2- and M4-containing mAChRs, 0.15 μl mixture of AF-DX116 (150 nM) and PD102807 (200 nM) was injected. To assess the spread of drug at the injection site, 0.15 μl of Alexa Fluor 633 hydrazide (A30634; Invitrogen) in ACSF was injected, and the brain slices were examined using confocal microscopy.

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing

To selectively delete the Chrnb2 or Chrna7 gene in S1 VIP INs, 0.2 μl AAV5.2-U6-β2-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry that encodes a sgRNA sequence (ATCAGCTTGTTATAGCGGGA) for Chrnb2 or AAV5.2-U6-α7-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry that encodes a sgRNA sequence (GGTGAGCGGCTGCGAGTCGT) for Chrna7 45 was injected into the S1 of VipIRES-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mice (for behavior tests) or VipIRES-Cre; LSL-Cas9-EGFP; Thy1-GCaMP6s mice (for imaging Ca2+ in S1 PNs). To delete Chrnb2 or Chrna7 in SST or PV INs in L2/3 of S1, 0.2 μl mixture (volume ratio 1:1) of AAV5.2-U6-β2-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry and AAV5.2-U6-α7-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry were injected at the coordinates (AP −0.5 mm, ML 1.7 mm, SP 200 μm) in SstIRES-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mice or at the coordinates (AP −0.5 mm, ML 1.7 mm, SP 300 μm) in PvalbT2A-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mice. The same amount of AAV5.2-U6-control-gRNA-SYN-mCherry encoding a scrambled RNA sequence (GCGAGGTATTCGGCTCCGCG) 45 was injected into the S1 of control mice. To delete both Chrnb2 and Chrna7 genes in S1 PNs, 0.3 μl mixture (1:1:1) of AAV5.2-U6-β2-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry, AAV5.2-U6-α7-sgRNA-SYN-mCherry, and AAV9-CaMKII0.4-Cre were injected into L2/3 of S1 (AP −0.5 mm, ML 1.7 mm, SP 200 μm) in Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mice. As a control, the same amount of AAV5.2-U6-control-gRNA-SYN-mCherry and AAV9-CaMKII0.4-Cre (2:1) was injected into L2/3 of S1 in a separate group of Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mice. To delete Slc32a1 in aNB cholinergic neurons, 0.2 μl AAV1-FLEx-SaCas9-U6-sgSlc32a1 (sgRNA sequence, AGGAGCGCCGCCGCGCTGATA) or AAV-FLEX-SaCas9-U6-sgRNA-scramble (control)47 was injected into the aNB of ChATIRES-Cre mice. To delete Slc32a1 in aNB→S1 projection cells, 0.15 μl AAV2-retro-PGK-Cre was injected into the S1, and 0.2 μl AAV1-FLEx-SaCas9-U6-sgSlc32a1 or AAV1-FLEX-SaCas9-U6-sgRNA-scramble (control) was injected into the aNB of C56BL/6J mice. SNI or sham surgery was performed on the contralateral hindlimb 3 weeks after viral injections.

Cell-type specific circuit dissection

To retrogradely label cells projecting to the S1, 0.1 μl red fluorescent Retrobeads (LumaFluor) were unilaterally injected into the S1 of C57BL/6J mice. Brain coronal sections confirmed that the injected Retrobeads were contained in L1–3 of S1. To label the S1 cells receiving monosynaptic projections from the aNB, 0.1 μl AAV1-EF1α-FLPo was injected into the aNB and 0.2 μl AAV1-EF1a-fDIO-mCherry was injected into the ipsilateral S1 of VipIRES-Cre mice crossed with Ai162 reporter line. VIP INs were visualized by immunostaining using an anti-GFP antibody. To label the aNB-derived cholinergic axons in the S1 (Supplementary Fig. 4), 0.1 μl AAV1-CAG-FLEx-EGFP was injected into the ipsilateral aNB of ChATIRES-Cre mice. To label the aNB cells receiving monosynaptic projections from the PB, 0.1 μl AAV1-SYN-Cre was injected into the PB, and 0.1 μl AAV1-CAG-FLEx-EGFP was injected into the ipsilateral aNB of C57BL/6J mice. This experimental design was also used to visualize in the S1 the axons derived from the aNB cells that receive monosynaptic inputs from the PB. To retrogradely label the PB cells projecting to the aNB, 0.1 μl red Retrobeads were unilaterally injected into the aNB, and 0.1 μl AAV1-CAG-FLEx-EGFP was injected into the ipsilateral PB of Slc17a6IRES-Cre or ChATIRES-Cre mice.

For Retrobeads tracing experiments, mice were transcardially perfused 7–10 days after injections. For viral tracing experiments, mice were perfused 2–3 weeks after injections. For experiments combining the Retrobeads tracing and viral labeling, mice were transcardially perfused 2 weeks after injections. The fixed brain tissue was coronally sectioned for histological examinations to determine cell types.

Abbreviations of brain regions marked in the figures are as follows. AQ, cerebral aqueduct; CEA, central amygdalar nucleus; CP, caudoputamen; CUN, cuneiform nucleus; DR, dorsal nucleus raphe; fi, fimbria; GPe, external globus pallidus; GPi, internal globus pallidus; ic, internal capsule; LC, locus coeruleus; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; MEA, medial amygdalar nucleus; MEV, midbrain trigeminal nucleus; MRN, midbrain reticular nucleus; NB, nucleus basalis; NI, nucleus incertus; PAG, periaqueductal gray; PB, parabrachial nucleus; PCG, pontine central gray; PPN, pedunculopontine nucleus; RT, reticular nucleus of the thalamus; S1, primary somatosensory cortex; scp, superior cerebellar peduncles; SI, substantia innominata; st, stria terminalis; uf, uncinate fascicle; V4, fourth ventricle; VTN, ventral tegmental nucleus.

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

Mice were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with a phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brain was removed and post-fixed in 4% PFA for 3 days and rinsed three times in PBS. Embedded in 1.5% agarose and immersed in PBS, the brain was sectioned with a Leica vibratome (VT 1000 S) at 50 μm and 20 μm thickness for immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), respectively. Sections were post-fixed in 4% PFA for 1 h and washed three times in PBS. Floating sections were permeabilized and blocked at room temperature in 0.1% Triton X-100 with 5% donkey serum in PBS for 1.5 h and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: mouse anti-NeuN (1:500; MAB377; Millipore), rabbit anti-GFP (1:1,500; ab6556; Abcam), mouse anti-mCherry (1:500; SAB2702295; SigmaAldrich), mouse anti-CGRP (1:400; C7113; SigmaAldrich), goat anti-ChAT (1:400; AB144P; Millipore), mouse anti-ChAT (1:200; PIMA531382; Invitrogen), mouse anti-VAChT (1:300; 139103; Synaptic Systems), rabbit anti-VGAT (1:300; 131011; Synaptic Systems). The sections were subsequently washed three times in PBS and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies: donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; A21206; Invitrogen), donkey anti-rabbit CF488A (1:500; 20015; Biotium), donkey anti-rabbit CF543 (1:500; 20308; Biotium), donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (1:500; A31573; Invitrogen), donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; A21202; Invitrogen), donkey anti-mouse CF543 (1:500; 20305; Biotium), donkey anti-mouse CF647 (1:500; 20046; Biotium), donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; A11055; Invitrogen), donkey anti-goat CF543 (1:500; 20314; Biotium), donkey anti-goat CF647 (1:500; 20048; Biotium). The sections were washed and mounted in medium with (010020; SouthernBiotech) or without (010001; SouthernBiotech) DAPI for confocal imaging.

For FISH (Supplementary Fig. 2), brain slices were mounted on a slide. Pre-treatment procedures (post-fixation and dehydration) and fluorescent multiplex assay (Multiplex Fluorescent v2 Assay; ACD) were performed following the manufacturer’s manual (323100-USM; ACD). An RNA probe for Vip (RNAscope Probe-Mm-Vip; 415961; ACD) was hybridized to Vip mRNA. A fluorophore (TSA plus Cy5; NEL745001KT; Akoyabio) was used to visualize the hybridized probes.

Confocal imaging was performed with a 10× or 20× objective on a Nikon Ti laser scanning confocal system (Nikon). Images were taken at 1024 × 1024 pixels with the resolution of 0.622 μm pixel−1 for visualizing somas and 0.104 μm pixel−1 for visualizing axons and boutons. The fluorophores of Alexa Fluor 488/CF488A, CF543/Red Retrobeads/Cy5, and Alexa Fluor 647/CF647 were excited by 488, 561, and 640 nm lasers, respectively. A Z-stack of images was obtained at 2-μm and 0.5-μm step size for soma and axon/bouton visualization, respectively, and was projected at maximum intensity to generate the final multi-channel images, which were then analyzed using ImageJ software (Fiji 2.3.0/1.53s).

Pain behavior tests

von Frey test.

Mice were individually placed in clear acrylic boxes (10 cm × 7 cm × 7 cm) on a mesh table and habituated for at least 30 min before testing procedures. Dixon’s up and down method measured the animals’ paw withdrawal threshold 83. In brief, a series of von Frey fibers were presented in consecutive ascending order. 50% response threshold was calculated as 50% g threshold = 10(Xf + κδ – 4) where Xf is the value (in log units) of the final von Frey fiber used; κ is the tabular value for the pattern of positive/negative responses 84; and δ = mean difference (in log units) between stimuli (here, 0.2699).

Dynamic tactile allodynia.

Dynamic tactile allodynia was measured as previously reported 85. In brief, the external lateral edge of the hind paw was lightly stroked by a paintbrush (5/0; Princeton Art & Brush Co.) from heel to toe. The tip of the paintbrush was trimmed blunt to avoid extra stimulation to the skin. The mouse’s response was manually scored based on the criteria used previously 85. Three successful tests were performed for each mouse at intervals of > 5 min to obtain a mean score.

Cold test.

Cold allodynia was tested using a custom-built cold plate. Before testing, mice were individually placed in a clear acrylic container (10 cm × 7 cm × 20 cm) on the plate at room temperature and habituated for 30 min. During testing, the temperature of the cold plate was set at 0°C. A stopwatch was used to record the latency of the withdrawal response of the hind paw with SNI or sham surgery. Hind paw lifting coupled with flinching was used to determine withdrawal latencies.

Thermal test.

Mice were individually placed in clear acrylic boxes (10 cm × 7 cm × 7 cm) on the transparent glass pane of an infrared plantar testing system (Model 37370, Ugo Basile, Italy) and habituated for at least 30 min before testing procedures. During testing, the lateral plantar aspect (the sural nerve skin territory) of the hind paw was stimulated through the glass pane by the thermal emitter, which delivers radiant heat at thermal energy level 15 as defined by the manufacturer’s power scale. The latency of paw withdrawal was scored automatically. Each mouse was tested 3–4 times at intervals of more than 1 h to obtain a mean score. A cutoff time of 20 s was used to prevent tissue damage.

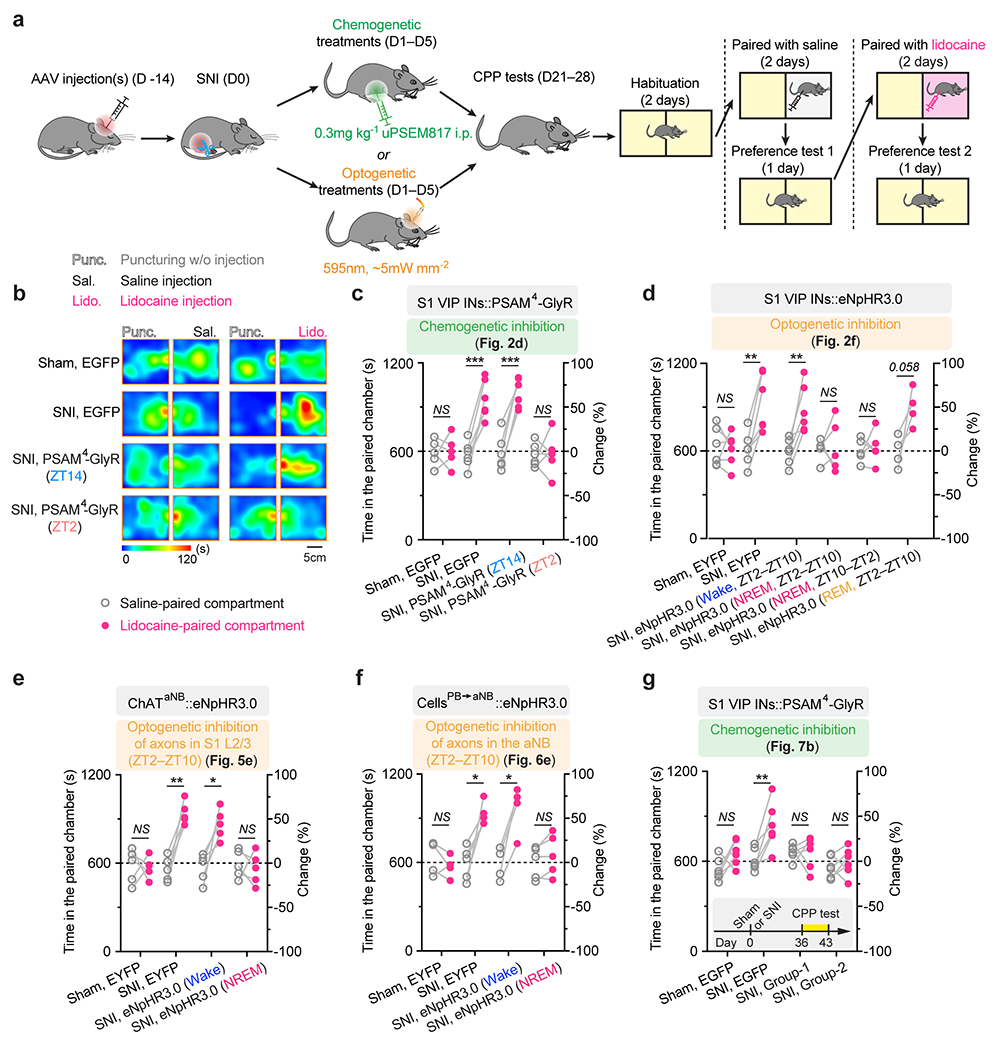

Conditioned place preference.

The conditioned place preference (CPP) test was performed in a two-compartment chamber (Ugo Basile; Italy). Before testing, mice were habituated to the chamber for 2 consecutive days with three 20-min sessions per day. In the pre-conditioning phase, animals were placed in the CPP chamber with the door removed and recorded for 20 min. The animals showing strong unconditioned preference (> 25% above chance level, i.e., > 750 s in one chamber) were excluded. Mice were conditioned and tested in two separate sessions with saline or lidocaine injected into the surgical site. For the saline conditioning, mice were first subjected to vehicle injection (puncturing but without injection) and immediately confined to the randomly assigned compartment for 30 min; about 6 h later, mice were injected with 50 μl saline and immediately placed in the other compartment for 30 min. The procedures were repeated the next day. The mice were tested on the third day with free access to both compartments for 20 min. The subsequent lidocaine conditioning was similar to the saline conditioning, but lidocaine (0.2% in 50 μl saline) was injected instead of saline. The time spent in saline- and lidocaine-paired compartments were compared to assess the animal’s ongoing pain.

Statistics

Summary data are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine samples sizes, but our sample sizes for in vivo imaging and behavioral studies are similar to those reported in previous publications 19, 49, 86, 87. We tested the data for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and performed nonparametric (or parametric) statistical tests if normality was (or was not) rejected. We used Wilcoxon rank sum and Mann-Whitney U tests (or t-test) to compare two groups and Friedman (or one- or two-way ANOVA) to compare more than two groups. Friedman’s tests (or one- or two-way ANOVA) were followed by Dunn’s test (or Bonferroni’s test) when more than one comparison was made. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to compare the cumulative distribution of neuronal activity. All tests were conducted as two-sided tests. Significant levels were set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (v8.4). Statistical details can be found in figure legends and Supplementary Table 1.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Alterations in S1 inhibitory neuronal Ca2+ activity are reduced by silencing VIP INs during sleep after SNI.

a, Schematic of S1 local circuitry. b, SNI-induced changes in neuronal Ca2+ activity (mean ± SEM) in S1 of resting awake mice (n = 192, 93, 100, and 86 cells from three mice per group). PNs, P = 0.23 (day 1), 0.0026 (day 3), < 0.0001 (day 5–30); VIP, P = 0.017 (day 1), < 0.0001 (day 2–7), 0.0046, 0.0036; SST, P = 0.46, 0.68, 0.53, 0.034, 0.0043, 0.018, 0.014; PV, P = 0.083, 0.0006, < 0.0001 (day 5, 7), 0.004, 0.023, 0.007. c, Top, experimental design for chemogenetic inhibition of S1 VIP INs via hM4D(Gi) and Ca2+ imaging of VIP and SST INs. Bottom, representative two-photon images of GCaMP/mCherry-expressing VIP INs (arrows) and GCaMP-expressing SST INs (bottom; 4 mice). d, Average Ca2+ traces (mean with 95% CI) of VIP and SST INs before and 1 h after CNO injection (n = 168 and 226 cells from four mice). Acute inhibition of VIP INs (****P < 0.0001) increases SST neuron activity (****P < 0.0001) in SNI mice. e, Daily inhibition of VIP INs at ZT2 reduces SNI-induced SST hypoactivity (n = 217, 177, 190 cells from four mice per group; ****P < 0.0001). f, Top, experimental design for chemogenetic inhibition of S1 VIP INs via PSAM4-GlyR and Ca2+ imaging of PV INs. Bottom, two-photon images of EGFP-expressing VIP INs and GCaMP-expressing PV INs (13 mice). g, Similar to (d), but for PV INs before and after uPSEM817 injection (n = 203 cells from four mice; ****P < 0.0001). h, Similar to (e), but for PV INs after VIP inhibition (n = 142, 116, 148 cells from three mice per group; ****P < 0.0001). Box bounds and center, quartiles and median; whiskers, min and max (d, e, g, h). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by two-sided Wilcoxon (b, d, g) or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (e, h). Detailed statistics in Supplementary Table 1.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Silencing S1 VIP INs during sleep prevents persistent ongoing pain after SNI.

a, Schematic of experimental timeline and the conditioned place preference (CPP) test. Two weeks after viral infection, mice were subjected to SNI and daily inhibition of the target cells in the sleep or wake phase for 5 days. CPP tests were performed 2–3 weeks after the last inhibition session. b, Representative heat maps showing time spent in CPP chambers. c, Time spent in the saline- and lidocaine-paired chambers for individual mice (n = 5, 5, 5, 6 mice; saline vs. lidocaine, P = 0.87, 0.0004, 0.0001, 0.90; related to Fig. 2d). d, Time spent in the saline- and lidocaine-paired chambers for individual mice (n = 6, 6, 6, 5, 5, 4 mice; saline vs. lidocaine, P = 0.81, 0.0035, 0.0063, 0.18, 0.74, 0.058; related to Fig. 2f). e, Time spent in the saline- and lidocaine-paired chambers for individual mice (n = 5 mice per group, saline vs. lidocaine, P = 0.91, 0.0022, 0.019, 0.66; related to Fig. 5e). f, Time spent in the saline- and lidocaine-paired chambers for individual mice (n = 4, 5, 4, 5 mice; saline vs. lidocaine, P = 0.36, 0.012, 0.011, 0.12; related to Fig. 6e). g, Time spent in the saline- and lidocaine-paired chambers for individual mice (n = 6 mice per group; saline vs. lidocaine, P = 0.11, 0.0010, 0.97, 0.49; related to Fig. 7b). Inset, experimental timeline. Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant; by two-sided paired t-test. Detailed statistics in Supplementary Table 1.