Abstract

Objective

To evaluate efficacy and safety of the interleukin‐23p19‐subunit inhibitor, guselkumab, in DISCOVER‐1 patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) by prior use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi).

Methods

The phase 3, randomized, placebo‐controlled DISCOVER‐1 study enrolled patients with active PsA (swollen joint count ≥3, tender joint count ≥3, and C‐reactive protein level ≥ 0.3 mg/dl) despite standard therapies; approximately one‐third could have received two or fewer prior TNFi. Patients were randomized to 100 mg of guselkumab every 4 weeks (Q4W); 100 mg of guselkumab at week 0, at week 4, and every 8 weeks (Q8W); or placebo with crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24. Efficacy end points of ≥20% and ≥50% improvement in individual American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria and achieving the minimal disease activity (MDA) components were summarized by prior TNFi status.

Results

In DISCOVER‐1, 118 (31%) patients previously received one or two TNFi. As previously reported, rates for acheiving ≥20% improvement in the composite ACR response at week 24 and week 52 were similar in TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients randomized to guselkumab Q4W (76% and 68%, respectively) and Q8W (61% and 58%, respectively). Similar trends were observed for response rates of ≥20% and ≥50% improvement in individual ACR criteria and for achieving individual MDA components at week 24; TNFi‐naive patients were more likely to achieve end points related to physical function and pain than TNFi‐experienced patients. Overall, response rates were maintained or increased through week 52 regardless of prior TNFi use. Through week 60 in guselkumab‐treated TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients, 62% and 64%, respectively, reported one or more adverse events (AEs); 4% and 6% had serious AEs, respectively.

Conclusion

Through 1 year, 100 mg of guselkumab Q4W and Q8W provided sustained improvements across multiple domains in both TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients with active PsA.

SIGNIFICANCE & INNOVATIONS.

What is already known on this topic?

The DISCOVER‐1 phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study assessed the efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an interleukin‐23p19‐subunit inhibitor, in tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi)‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) through 1 year.

At week 24, guselkumab‐treated patients had significantly greater improvements in signs and symptoms of PsA compared with patients receiving placebo. The treatment effect in the proportion of patients achieving ≥20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology criteria (ACR20) response (DISCOVER‐1 primary end point) observed in TNFi‐experienced patients, who exhibited more severe disease at baseline, was generally consistent with that in TNFi‐naive patients, with sustained efficacy and high retention through 1 year.

Safety results through 1 year of guselkumab treatment in DISCOVER‐1 were consistent with the known safety profile of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis and PsA.

What Does This Study Add?

Guselkumab generally demonstrated a consistent treatment effect in both TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients for achieving multiple end points, including the components of ACR response and minimal disease activity, assessing musculoskeletal and skin manifestations, physical function, and pain, with durable response rates through 1 year.

The guselkumab safety profile was generally comparable in TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients through 1 year and consistent with the known safety profile of guselkumab, with no cases of opportunistic infections, tuberculosis, inflammatory bowel disease, or major adverse cardiovascular events in either TNFi cohort through 1 year of guselkumab treatment.

How might this impact clinical practice or future developments?

By selectively targeting interleukin‐23, guselkumab provides meaningful and durable improvements across multiple domains in the signs and symptoms of PsA regardless of prior TNFi therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a progressive, multidimensional inflammatory disorder associated with aberrations in the interleukin‐23 (IL‐23)/IL‐17 pathway (1). Treatment decisions for patients with PsA are often guided by the domains most affected in the individual patient (2, 3). Although tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) are generally the biologic of first choice for patients with PsA when conventional synthetic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) are ineffective, they have a primary treatment failure rate of 40% for a modest target of ≥20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology criteria (ACR20) response (4, 5). Real‐world evidence from registries of patients with PsA has found shorter treatment persistence in biologic‐experienced patients than in biologic‐naive patients when initiating TNFi therapies (6, 7, 8). In general, the rate of treatment failure increases and persistence decreases with each subsequent TNFi received (6, 7, 8). Additionally, TNFi therapies are associated with a range of toxicities, most commonly an increased risk of infection, including tuberculosis (9, 10, 11). Considering the progressive failure rate when multiple TNFi are prescribed for PsA, the population of TNFi‐experienced patients is increasing over time. The armamentarium available to rheumatologists today includes biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs using mechanisms of action other than TNF inhibition, thus expanding treatment options for patients with PsA who do not respond to or are intolerant of TNFi (2, 3). It is therefore critical to thoroughly evaluate the efficacy and safety of a new biologic mechanism of action in TNFi‐exposed patients with PsA to inform treatment decisions for this patient population.

Guselkumab (Janssen Biotech) (12, 13), a high‐affinity, fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the IL‐23p19 subunit, demonstrated efficacy with a favorable safety profile in reducing the signs and symptoms of active PsA in two phase 3, randomized, placebo‐controlled studies, DISCOVER‐1 (14) and DISCOVER‐2 (15). Most patients enrolled in these trials were biologic‐naive; however, 31% of patients in DISCOVER‐1 had previously received treatment with one or two TNFi. The 1‐year DISCOVER‐1 study demonstrated efficacy of guselkumab through 1 year in this mixed population of patients with PsA who were TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced (16). The more recent phase 3b COSMOS study demonstrated that guselkumab was effective and safe in a more homogenous PsA cohort defined by prior inadequate response (inadequate efficacy or intolerance) to one or two TNFi (TNFi‐IR) (17). We have now comprehensively assessed the demographic and disease characteristics, disposition, guselkumab efficacy across disease domains, and guselkumab safety in the TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced cohorts from DISCOVER‐1.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Patient eligibility criteria for DISCOVER‐1 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03162796) were previously reported (14). Patients met Classification for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria at screening and had active PsA (swollen joint count [SJC] ≥3, tender joint count [TJC] ≥3, and C‐reactive protein [CRP] level ≥0.3 mg/dl). Eligible patients also had a current or documented history of psoriasis and an inadequate response or intolerance to standard therapies for PsA (apremilast, csDMARDs, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]). Patients who received prior treatment with one or two TNFi were eligible but limited to approximately 30% of the study population and could not have received TNFi therapies within the prespecified time frame before the first study agent administration (infliximab or intravenous golimumab: 8 weeks; subcutaneous golimumab, adalimumab, or certolizumab pegol: 6 weeks; etanercept: 4 weeks). Patients were permitted but not required to continue background use of stable doses of one csDMARD, oral corticosteroids (≤10 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent dose), and NSAIDs or other analgesics. Patients with other inflammatory diseases and those who had previously received biologics other than TNFi were excluded. Patients also met criteria for screening laboratory testing and tuberculosis history, testing, and treatment (for latent tuberculosis).

Study design

The study design and procedures for the DISCOVER‐1 phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study were previously detailed (14). Patients were assigned to receive subcutaneous injections of 100 mg of guselkumab every 4 weeks (Q4W); 100 mg of guselkumab at week 0, at week 4, and every 8 weeks (Q8W); or placebo Q4W with crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24 (placebo→Q4W) through week 48. At week 16, patients with less than 5% improvement from baseline in both SJC and TJC were eligible for early escape and had the option to initiate treatment with or increase the dose of NSAIDs or other analgesics, oral corticosteroids, or csDMARDs at the discretion of the investigator up to predefined limits.

DISCOVER‐1 was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with Good Clinical Practices. The protocol was approved by each site's governing ethical body, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient at enrollment.

Assessments and outcomes

Clinical efficacy was assessed using the ACR response criteria, comprising TJC (0‐68), SJC (0‐66, excluding hips), patient assessment of pain (visual analog scale [VAS]; 0‐10 cm), patient global assessment (PtGA) (arthritis, VAS; 0‐10 cm), physician global assessment (PhGA) (VAS; 0‐10 cm), physical function as determined by the Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index (HAQ DI) (score of 0‐3), and CRP level (mg/dl) (5). Enthesitis was assessed using the Leeds enthesitis index (LEI) (score of 0‐6). Skin disease was assessed using the investigator's global assessment (IGA) of psoriasis (0 = cleared, 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, and 4 = severe) and the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) (score of 0‐72). Minimal disease activity (MDA), defined as meeting five of the seven following criteria, was also assessed: TJC ≤1, SJC ≤1, PASI score ≤1, patient pain VAS score ≤15 (0‐100 mm), PtGA VAS score ≤20 (arthritis and psoriasis; 0‐100 mm), HAQ DI score ≤0.5, and tender entheseal points ≤1.

Efficacy outcomes that were prespecified in the overall DISCOVER‐1 study included the proportions of patients achieving ACR20 (5) and ACR50 responses, MDA, and HAQ DI response (improvement from baseline ≥0.35 in patients with a baseline HAQ DI score ≥0.35). Prespecified skin efficacy end points were assessed in patients with ≥3% body surface area (BSA) affected by psoriasis and IGA ≥2 at baseline and included an IGA score of 0 (IGA 0), an IGA score of 0 or 1 plus a ≥2‐grade improvement from baseline (IGA 0/1), and ≥75% improvement in PASI score (PASI 75), PASI 90, and PASI 100 responses. Post hoc analyses were performed to evaluate these end points and the proportions of patients achieving ≥20% improvement and ≥50% improvement in the individual ACR components and achieving the individual MDA components among TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients.

Patients were monitored through week 60 for the occurrence of adverse events (AEs). Safety outcomes included rates of AEs, serious AEs (SAEs), and AEs leading to discontinuation of study treatment. Other AEs of interest included infections, tuberculosis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) (predefined as cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke), malignancies, and death.

Data analyses

Efficacy outcomes were summarized by randomized treatment groups and by prior TNFi use (naive or experienced). Through week 24, patients who met treatment failure criteria (14) or had missing data for any reason were classified as nonresponders. After week 24, patients who had missing data for any reason were classified as nonresponders (nonresponder imputation), and no treatment failure criteria were applied. These analyses were exploratory; no formal hypothesis testing was performed. AEs were summarized for all treated patients according to actual treatment received and by prior TNFi use.

RESULTS

Patient disposition and characteristics

Among the 381 randomized and treated patients in DISCOVER‐1, 118 (31%) previously received one (n = 102) or two (n = 16) TNFi. Of the 134 total prior TNFi exposures, 21 (16%) were less than 6 months in duration and 113 (84%) were 6 months or more in duration. A total of 44 patients (37%) (Q4W: n = 17; Q8W: n = 15; placebo: n = 12) reported discontinuing their prior TNFi therapy because of inadequate response. No reason for discontinuing the prior TNFi was given for 30 patients; among patients with a documented reason for discontinuing their prior TNFi therapy, reasons other than inadequate response were contraindication (n = 4 [3%]), AEs (n = 6 [5%]), financial and/or insurance (n = 43 [36%]), and patient preference (n = 1 [1%]). Baseline patient demographic and disease characteristics of the overall study population in DISCOVER‐1 were previously detailed (14). TNFi‐experienced patients, on average, tended to be slightly older and have a longer duration of PsA, higher TJC and SJC, higher levels of systemic inflammation, and greater impairment of physical function than TNFi‐naive patients (Table 1). TNFi‐experienced patients were more likely to have a body mass index of 30 or more and have more extensive skin involvement with a longer duration of psoriasis and were more likely to be receiving concomitant methotrexate (MTX) at baseline relative to TNFi‐naive patients. At baseline, 63% (166 of 263) of TNFi‐naive patients and 70% (83 of 118) of TNFi‐experienced patients had ≥3% BSA psoriasis involvement and IGA ≥2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographic and disease characteristics for TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients

| All | TNFi‐naive | TNFi‐experienced | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 381 | n = 263 | n = 118 | |

| Age, y | 48.4 ± 11.4 | 47.6 ± 11.7 | 50.2 ± 10.5 |

| Male | 195 (51.2) | 133 (50.6) | 62 (52.5) |

| Weight, kg | 86.0 ± 18.8 | 86.3 ± 18.8 | 85.4 ± 18.7 |

| Body mass index | 29.8 ± 5.8 | 29.8 ± 6.0 | 29.9 ± 5.5 |

| Normal (<25) | 79 (20.7) | 58 (22.1) | 21 (17.8) |

| Overweight (≥25 and <30) | 136 (35.7) | 95 (36.1) | 41 (34.7) |

| Obese (≥30) | 166 (43.6) | 110 (41.8) | 56 (47.5) |

| PsA disease duration, y | 6.8 ± 6.6 | 5.6 ± 6.2 | 9.4 ± 6.9 |

| SJC (0‐66) | 9.8 ± 7.6 | 9.5 ± 7.0 | 10.6 ± 8.7 |

| TJC (0‐68) | 19.3 ± 14.0 | 17.9 ± 13.1 | 22.4 ± 15.3 |

| PtGA of arthritis, VAS 0‐10 cm | 6.3 ± 2.1 | 6.0 ± 2.2 | 6.7 ± 1.9 |

| PhGA, VAS 0‐10 cm | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 6.7 ± 1.6 |

| Patient assessment of pain, VAS 0‐10 cm | 5.9 ± 2.1 | 5.6 ± 2.1 | 6.5 ± 1.9 |

| Psoriasis disease duration, y | 17.0 ± 12.7 | 16.4 ± 13.3 | 18.3 ± 11.1 |

| Patients with ≥3% BSA affected by psoriasis | 281 (73.9) a | 191 (72.9) b | 90 (76.3) |

| Patients with IGA ≥2 and ≥3% BSA | 249 (65.4) a | 166 (63.4) b | 83 (70.3) |

| HAQ DI (0‐3) | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.7 |

| CRP, mg/dl | |||

| Mean | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 1.1 ± 1.8 | 1.9 ± 2.3 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.3‐1.6) | 0.6 (0.3‐1.0) | 1.2 (0.5‐2.5) |

| Concomitant medications | |||

| csDMARD use | 247 (64.8) | 160 (60.8) | 87 (73.7) |

| Methotrexate use | 211 (55.4) | 133 (50.6) | 78 (66.1) |

Note: Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%) unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; CRP C‐reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; HAQ DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index; IGA, investigator's global assessment; IQR, interquartile range; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PhGA, physician's global assessment; PtGA, patient's global assessment; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; VAS, visual analog scale.

N = 380.

N = 262.

Ninety percent (347 of 381) of randomized and treated patients completed study treatment through week 48 (Figure 1). Among the 263 TNFi‐naive patients, 241 (92%) completed study treatment through week 48. Among the 118 TNFi‐experienced patients, 106 (90%) completed study treatment through week 48.

Figure 1.

Disposition of patients through week 48 for TNFi‐naive (A) and TNFi‐experienced (B) patients in DISCOVER‐1. Through week 24, 11 TNFi‐naive patients (Q4W: 3; Q8W: 3; PBO: 5) and eight TNFi‐experienced patients discontinued study treatment (Q4W: 0; Q8W: 1; PBO: 7). GUS, guselkumab; PBO, placebo; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Efficacy

Overall response

As previously reported, the DISCOVER‐1 primary end point was met, with significantly greater proportions of patients in the Q4W (59%) and Q8W (52%) groups achieving an ACR20 response at week 24 when compared with the placebo group (22%) (both P < 0.0001); similar results were observed in TNFi‐experienced (58% and 56% vs. 18%, respectively) and TNFi‐naive (60% and 50% vs. 24%, respectively) patients (14). Response rates in patients randomized to the Q4W and Q8W groups were maintained over time through week 52 in both TNFi‐experienced (68% and 58%, respectively) and TNFi‐naive (76% and 61%, respectively) patients (16). Similar trends were observed for ACR50 response (14, 16).

Among all patients, significantly greater proportions of those treated with guselkumab achieved MDA at week 24 compared with those receiving placebo (14). Similar trends were seen regardless of prior TNFi use, with higher response rates observed in TNFi‐naive patients (Q4W: 32%; Q8W: 26%; placebo: 15%) than in TNFi‐experienced patients (26%, 17%, and 3%, respectively) (16). Response rates increased at week 52 in both the TNFi‐naive (Q4W: 43%; Q8W: 34%; placebo→Q4W: 31%) and TNFi‐experienced (29%, 22%, and 13%, respectively) cohorts (16).

Domain‐specific responses

Musculoskeletal manifestations

Numerically greater proportions of guselkumab‐treated patients achieved ≥20% improvement in SJC, ≥50% improvement in SJC, and SJC ≤1 at week 24 versus placebo‐treated patients, with similar response rates for both TNFi‐naive (83%‐90%, 71%‐81%, and 45%‐60%, respectively) and TNFi‐experienced (85%‐92%, 73%‐82%, and 54%‐55%, respectively) patients. Similar trends were observed for achieving ≥20% improvement in TJC, ≥50% improvement in TJC, and TJC ≤1 at week 24 (Figure 2). At week 52, response rates in the Q4W and Q8W groups were maintained or increased across all SJC and TJC outcomes and were similar in TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients.

Figure 2.

Proportions of patients achieving improvements in SJC and TJC at week 24 and week 52 by prior TNFi use. A, ≥20% improvement in SJC. B, ≥50% improvement in SJC. C, SJC ≤1. D, ≥20% improvement in TJC. E, ≥50% improvement in TJC. F, TJC ≤1. GUS, guselkumab; PBO, placebo; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Among patients who crossed over from placebo to Q4W, response rates for achieving these SJC and TJC end points at week 52 were similar to those in the Q4W and Q8W groups for TNFi‐naive patients; however, TNFi‐experienced patients had numerically lower response rates (Figure 2).

The proportions of patients in the Q4W and Q8W groups achieving the MDA component of an LEI score ≤1 at week 24 were similar between TNFi‐naive (72% and 71%, respectively) and TNFi‐experienced (84% and 73%, respectively) patients and were generally maintained at week 52 (Figure 3). In the placebo→Q4W group, response rates were numerically lower in TNFi‐experienced patients at weeks 24 and 52 (41% and 54%, respectively) than in TNFi‐naive patients (60% and 74%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Proportions of patients achieving an LEI score ≤ 1 at week 24 and week 52 by prior TNFi use. GUS, guselkumab; LEI, Leeds enthesitis index; PBO, placebo; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Skin manifestations

Among all patients with ≥3% BSA affected by psoriasis and IGA ≥2 at baseline in DISCOVER‐1, the proportions of patients achieving IGA 0/1, IGA 0, and PASI 90/100 responses at week 24 were significantly greater in the guselkumab groups compared with the placebo group, with response rates in the guselkumab groups maintained through 1 year (14, 16). Similar results were observed in both TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients for acheiving IGA 0/1, PASI 90, and PASI 100 responses (16).

In the current analyses, numerically greater proportions of patients in the Q4W and Q8W groups achieved IGA 0 when compared with those in the placebo group in both TNFi‐naive (57% and 45% vs. 12%%, respectively) and TNFi‐experienced (46% and 24% vs. 0%, respectively) patients (Figure 4). Response rates in the guselkumab groups increased at week 52 in both TNFi cohorts, with TNFi‐naive patients generally demonstrating higher response rates (Figure 4). Additionally, greater proportions of guselkumab‐treated patients achieved a PASI score of ≤1 at week 24 versus placebo‐treated patients, with TNFi‐naive patients (Q4W 76% and Q8W 71% vs. 38%) having higher response rates than TNFi‐experienced patients (Q4W 68% and Q8W 54% vs. 13%); however, by week 52, response rates were comparable between the TNFi cohorts (Figure 4). After crossing over to guselkumab at week 24, IGA and PASI response rates for patients in the placebo→Q4W group at week 52 were generally similar to those observed for patients who had been receiving guselkumab from baseline in both TNFi cohorts.

Figure 4.

Proportions of patients achieving IGA 0 (among patients with ≥3% body surface area affected by psoriasis and IGA ≥2 at baseline) (A) and PASI ≤1 (B) at week 24 and week 52 by prior TNFi use. IGA 0/1 response is defined as an IGA score of 0 or 1 with ≥2‐point improvement from baseline. GUS, guselkumab; IGA, investigator's global assessment; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PBO, placebo; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Patient‐reported outcomes

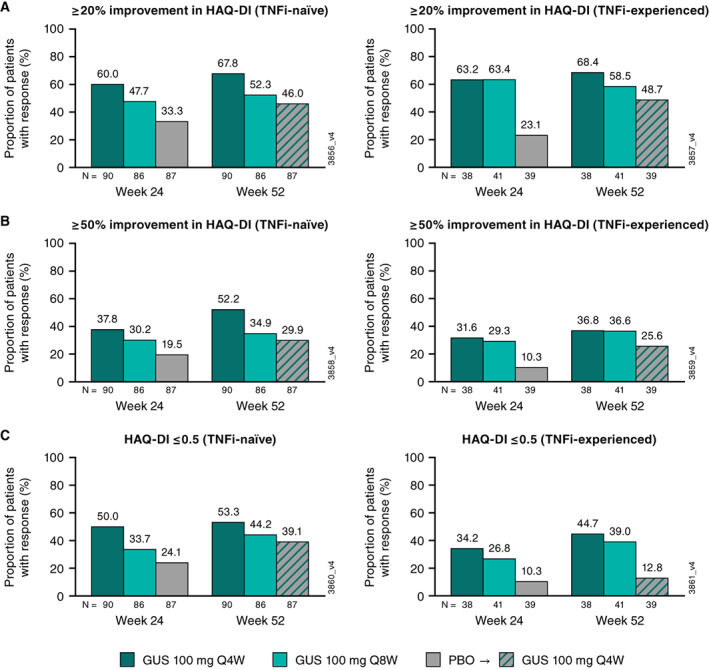

As previously reported, clinically meaningful improvement (≥0.35) in the HAQ DI score at week 24 was achieved by more than 50% of guselkumab‐treated patients versus 29% of placebo‐treated patients (14). The proportions of guselkumab‐treated patients achieving ≥20% and ≥50% improvement in HAQ DI at week 24 were similar between TNFi cohorts (Figure 5). Response rates for achieving a normalized HAQ DI score (≤0.5) at week 24 (Figure 5) tended to be numerically greater in TNFi‐naive patients than in TNFi‐experienced patients. At week 52, the proportions of guselkumab‐randomized patients achieving ≥20% improvement were maintained and were similar between the TNFi cohorts, whereas response rates for achieving ≥50% improvement in the HAQ DI score and a HAQ DI score ≤0.5 were numerically higher in TNFi‐naive patients (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Proportions of patients achieving ≥20% improvement in HAQ DI (A), ≥50% improvement in HAQ DI (B), and HAQ‐DI ≤0.5 (C) at week 24 and week 52 by prior TNFi use. GUS, guselkumab; HAQ DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index; PBO, placebo; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Among placebo→Q4W patients, similar proportions of TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients achieved ≥20% improvement in the HAQ DI score at week 52, whereas response rates for achieving ≥50% improvement in the HAQ DI or an HAQ DI score ≤0.5 tended to be higher in TNFi‐naive patients.

At week 24, the proportions of patients achieving improvements in PtGA VAS scores (≥20% and ≥50% improvement and PtGA ≤20) and patient assessment of pain VAS scores (≥20% and ≥50% improvement and pain ≤15) were numerically greater in the guselkumab groups compared with the placebo group; response rates among guselkumab‐treated patients were generally similar in the TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced cohorts (Figure 6). These response rates were maintained or increased at week 52. For patients in the placebo→Q4W group, those who were TNFi‐experienced tended to have lower response rates for PtGA and patient‐reported pain end points at week 52 compared with TNFi‐naive patients (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proportions of patients achieving improvements in PtGA VAS and patient assessment of pain VAS at week 24 and week 52 by prior TNFi use. A, ≥20% improvement in PtGA VAS. B, ≥50% improvement in in PtGA VAS. C, PtGA ≤20. D, ≥20% improvement in pain VAS, E, ≥50% improvement in pain VAS. F, Pain VAS ≤15. GUS, guselkumab; PBO, placebo; PtGA, patient global assessment; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; VAS, visual analog scale.

PhGA of disease and CRP

At week 24, more than three‐quarters of guselkumab‐treated patients achieved ≥20% improvement in PhGA, with similar response rates in TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients (Figure 7). At week 52, more than 80% of guselkumab‐randomized patients in both TNFi cohorts had ≥20% improvement in PhGA. In the guselkumab groups, an improvement of ≥50% in PhGA score was achieved by 55% to 59% of TNFi‐naive patients and 61% to 74% of TNFi‐experienced patients at week 24 and by 62% to 77% and 73% to 87%, respectively, at week 52 (Figure 7). In the placebo→Q4W group, response rates for achieving ≥20% or ≥50% improvement in PhGA at week 52 were similar to those in the guselkumab groups for TNFi‐naive patients; however, for TNFi‐experienced patients, response rates in the placebo→Q4W group were numerically lower than those in the guselkumab groups.

Figure 7.

Proportions of patients achieving ≥20% and ≥50% improvement in PhGA (A and B) and ≥20% and ≥50% improvement in CRP (C and D) at week 24 and week 52 by prior TNFi use. CRP, C‐reactive protein; GUS, guselkumab; PBO, placebo; PhGA, physician global assessment; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Across treatment groups, the proportions of guselkumab‐treated patients achieving ≥20% improvement and ≥50% improvement in CRP level at week 24 were generally similar in TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients and were maintained or increased at week 52.

Safety

Detailed safety findings in the overall DISCOVER‐1 population have been previously published (14, 16). Among TNFi‐naive patients, 51%, 56%, and 59% in the Q4W, Q8W, and placebo groups, respectively, experienced one or more AEs through week 24; among TNFi‐experienced patients, 63%, 49%, and 64%, respectively, reported one or more AEs during the placebo‐controlled period. Through week 24, one serious infection (leg abscess [TNFi‐naive, no concomitant csDMARDs]) and two deaths (pneumonia and cardiac failure [MACE]; both were TNFi‐experienced patients receiving concomitant MTX) occurred, all in patients receiving placebo. Iridocyclitis was reported in one patient receiving placebo (TNFi‐naive, concomitant MTX).

Through week 60, among all patients who received at least one guselkumab administration, 62% of TNFi‐naive and 64% of TNFi‐experienced patients reported one or more AEs (Table 2). The types and incidences of AEs through week 60 in guselkumab‐treated patients were generally consistent with those during the placebo‐controlled period. Overall, the rates of SAEs and serious infections through week 60 were low among all guselkumab‐treated patients, with numerically higher proportions of TNFi‐experienced patients (7 [6%] and 3 [3%], respectively) reporting SAEs and serious infections through week 60 compared with TNFi‐naive patients (9 [4%] and 1 [0.4%], respectively). There were no opportunistic infections; cases of tuberculosis, IBD, or MACE; or deaths in patients receiving guselkumab. Two patients (one in the Q8W group and one in the placebo group) reported a history of uveitis at baseline; no cases of uveitis occurred in guselkumab‐treated patients.

Table 2.

AEs through week 60 in TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients

| Placebo | Placebo→Q4W | Guselkumab 100 mg | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 0‐24 | Weeks 24‐60 a | Q4W weeks 0‐60 | Q8W weeks 0‐60 | Combined weeks 0‐60 | ||||||

| TNFi‐naive | TNFi‐experienced | TNFi‐naive | TNFi‐experienced | TNFi‐naive | TNFi‐experienced | TNFi‐naive | TNFi‐experienced | TNFi‐naive | TNFi‐experienced | |

| Patients, n | 87 | 39 | 82 | 32 | 90 | 38 | 86 | 41 | 258 | 111 |

| Patients with ≥1 | ||||||||||

| AE | 51 (58.6) | 25 (64.1) | 37 (45.1) | 18 (56.3) | 59 (65.6) | 30 (78.9) | 64 (74.4) | 23 (56.1) | 160 (62.0) | 71 (64.0) |

| SAE | 2 (2.3) | 3 (7.7) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (9.4) | 4 (4.4) | 0 | 4 (4.7) | 4 (9.8) | 9 (3.5) | 7 (6.3) |

| AE leading to discontinuation | 0 | 3 (7.7) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 4 (4.7) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (2.7) | 2 (1.8) |

| Infection | 23 (26.4) | 9 (23.1) | 19 (23.2) | 11 (34.4) | 30 (33.3) | 19 (50.0) | 41 (47.7) | 13 (31.7) | 90 (34.9) | 43 (38.7) |

| Serious infection | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 2 (6.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (2.7) |

| Opportunistic infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancy | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| MACE | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Iridocyclitis | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Deaths | 0 | 2 (5.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: Data are presented as n (%).

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; placebo→Q4W, placebo Q4W with crossover to guselkumab Q4W; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; SAE, serious adverse event; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Includes only AEs that occurred after crossing over to guselkumab at week 24.

In TNFi‐experienced patients, three patients receiving guselkumab experienced a serious infection: pyelonephritis and urosepsis in the placebo→Q4W group and cellulitis in the Q8W group; all three were receiving concomitant MTX. Other SAEs that occurred in TNFi‐experienced patients were one instance of a head injury due to a motor vehicle accident in the placebo→Q4W group and one patient each with ileus (no concomitant csDMARDs), cervical dysplasia (concomitant MTX), and supraventricular arrhythmia (concomitant MTX) in the Q8W group. Across all treatment groups, no TNFi‐experienced patient reported a malignancy through week 60.

Among TNFi‐naive patients, one serious infection occurred (acute bronchitis, Q8W group, no concomitant csDMARDs). Two malignancies, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma in situ, were reported as nonserious‐AEs in one TNFi‐naive patient (no concomitant MTX); one malignancy occurred that was classified as an SAE (Q8W, multiple myeloma, concomitant MTX) (14). Other SAEs in this cohort were atrial fibrillation in one patient in the placebo→Q4W group (no concomitant csDMARDs), renal colic (concomitant MTX) and a hand fracture (no concomitant MTX) in the Q8W group, and foot deformity (concomitant MTX), worsening of mammary hypertrophy (no concomitant csDMARDs), meniscus injury (no concomitant MTX), and venous thrombosis (concomitant MTX) in the Q4W group.

DISCUSSION

Guselkumab has demonstrated robust efficacy for the treatment of psoriatic skin disease in patients with plaque psoriasis (18, 19) and the domains of PsA (14, 15). Given that TNFi‐experienced patients constitute a substantial proportion of the PsA population requiring treatment with biologics (7, 20) and that treatment failure increases with each subsequent TNFi prescribed (6), a number of studies have evaluated the efficacy and safety of alternate mechanisms of action, such as inhibiting IL‐17 and IL‐23, in TNFi‐IR patients (ie, patients who received prior TNFi and discontinued because of lack of efficacy or intolerance) (17, 21, 22).

Most of the TNFi‐experienced patients in DISCOVER‐1 discontinued their prior TNFi because of inadequate response, because of insurance coverage, or for unspecified reasons; few discontinued because of an AE or contraindication. Approximately 84% of prior TNFi exposures were 6 months or longer, suggesting that most patients did not discontinue because of a primary nonresponse. Overall, 90% of patients enrolled in DISCOVER‐1 completed study treatment through 1 year (16), including 94% of TNFi‐experienced patients randomized to guselkumab at baseline.

Guselkumab‐treated patients in both TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced cohorts from DISCOVER‐1 demonstrated numerically higher response rates in achieving overall clinical response (ACR20 and ACR50 response and MDA) at week 24 compared with placebo‐treated patients, and response rates were maintained through 1 year in both TNFi cohorts (16). In the current analyses, similar trends were observed across all individual response domains assessed (musculoskeletal [TJC, SJC, and enthesitis], skin [PASI and IGA responses], and patient‐reported outcomes [pain and physical function]) in both the TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced populations, with some notable exceptions. Achieving the MDA criteria for HAQ DI, PtGA, and patient‐reported pain appeared to be more difficult for TNFi‐experienced patients. These findings could relate to the stringent criteria for MDA, as well as the fact that patients with longstanding disease and who may have more established joint damage could be less likely to achieve the MDA criteria related to physical function and pain (23). Of note, results from the current analyses suggest that the difficulty in achieving the MDA criterion for patient‐reported pain was related to factors other than enthesitis because more than 70% of patients in both TNFi cohorts achieved an LEI score of ≤1. Additionally, response rates for achieving the stringent skin response of IGA 0 tended to be numerically lower in the TNFi‐experienced cohort compared with the TNFi‐naive cohort, which was consistent with previous PASI 90 and PASI 100 analyses in this study population (16).

Among guselkumab‐randomized patients, response rates within each TNFi cohort were generally similar between the two dosing regimens. However, among TNFi‐experienced patients, numerically higher response rates were observed with the Q4W dosing regimen compared with the Q8W dosing regimen for the stringent outcomes of MDA and IGA 0. A new phase 3b study of guselkumab, SOLSTICE (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04936308), has been designed to evaluate the possible effects of more frequent dosing with the Q4W regimen in TNFi‐IR patients with PsA and is currently enrolling participants.

Overall, the increase in response rates (using nonresponder imputation) from week 24 to week 52 for many of the end points evaluated here suggest that some patients continue to improve through at least 1 year of treatment. However, some patients remained on treatment despite not achieving an ACR20 response at week 24. Based on skin and enthesitis data reported here, as well as improvements in fatigue previously demonstrated in guselkumab‐treated patients (24), we speculate that some patients may have had improvements in disease domains beyond those captured in the ACR criteria.

Among patients randomized to placebo, those who were TNFi‐experienced tended to have lower response rates at week 24 than TNFi‐naive patients. Patients who crossed over to guselkumab Q4W demonstrated improvements at week 52; however, response rates sometimes failed to match those of patients who had received guselkumab from baseline more frequently in the TNFi‐experienced patients. This suggests that delaying treatment in these patients may adversely affect long‐term outcomes. Together with the observation of lower rates of achieving MDA criteria in TNFi‐experienced patients (patients with more severe and longer duration of disease), this reinforces the need to treat early with an agent that is effective across multiple domains, particularly in limiting progression of joint damage, which can have irreversible effects on physical function and pain. Otherwise, the goals of normalized physical function and no to minimal pain, which are critical to achieving MDA, may be difficult to achieve.

Psoriatic nail disease was not assessed in DISCOVER‐1 or DISCOVER‐2; however, the effect of guselkumab Q8W on nail disease was evaluated in the phase 3 VOYAGE 1 (18) and VOYAGE 2 (19) studies of patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. In a pooled analysis of the VOYAGE studies, a significantly greater proportion of guselkumab‐treated patients achieved cleared or minimal nail psoriasis compared with placebo‐treated patients at week 16 (47% vs. 15%, P < 0.001) (25).

In both TNFi cohorts, the frequency of AEs in guselkumab‐treated patients through 1 year was similar to that reported through week 24, indicating a stable safety profile through the first and second 6‐month periods, which was consistent with results from the overall DISCOVER‐1 population (16). The safety profile of guselkumab was generally consistent for TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients treated through week 60, with comparable rates of AEs, AEs leading to discontinuation, and infections. SAEs and serious infections were numerically higher in TNFi‐experienced than in TNFi‐naive patients. They were all singular events with no discernable pattern and did not require discontinuation, except for a TNFi‐naive patient diagnosed with multiple myeloma. There were no reports of opportunistic infections, tuberculosis, IBD, MACE, or death among guselkumab‐treated patients in either TNFi subgroup. A larger pooled analysis of one phase 2 study and three phase 3 studies (DISCOVER‐1, DISCOVER‐2, and COSMOS) of guselkumab in adults with active PsA found that the numbers of AEs/100 patient‐years (including SAEs, serious infections, and AEs leading to discontinuation) through the end of the studies were similar in TNFi‐naive (n = 1138) and TNFi‐experienced (n = 416) patients (26).

The recent phase 3, randomized, placebo‐controlled COSMOS study (17) demonstrated the efficacy and consistent safety profile of guselkumab Q8W through 1 year in TNFi‐IR patients with PsA. Among the 285 TNFi‐IR patients enrolled in COSMOS, 44% of those receiving guselkumab Q8W achieved an ACR20 response at week 24 versus 20% of those receiving placebo, with a safety profile consistent with that of guselkumab in previous studies, including DISCOVER‐1 and DISCOVER‐2 (17). ACR20 and ACR50 response rates from the subset of DISCOVER‐1 patients who discontinued their prior TNFi because of inadequate efficacy (14, 15) support those of COSMOS that indicated guselkumab may be an appropriate therapy for TNFi‐IR patients with PsA. Altogether, guselkumab efficacy and safety has been demonstrated in three PsA populations defined by prior TNFi use: TNF‐naive, TNFi‐experienced, and TNFi‐IR.

TNFi therapies continue to be widely used in patients with PsA that is not well controlled with conventional therapies. However, for patients with PsA that is recalcitrant to TNFi therapy, several other treatment options are available, with current treatment guidelines recommending switching to an alternative mechanism of action rather than repeated switching among TNFi (2, 3). Thus, understanding the efficacy and safety of the available therapeutic agents in patients who have received prior TNFi therapy is important to clinicians and patients. Although multiple studies conducted in TNFi‐exposed patients with PsA demonstrate higher response rates with various therapies compared with placebo, differences in study design make comparison challenging. Ustekinumab was reported to be less efficacious in a TNFi‐experienced population compared with a TNFi‐naive population (27). Anti‐IL‐17 antibodies have slightly lower but substantial and sustainable efficacy in a TNFi‐IR population than in a TNFi‐naive population (17, 22). In phase 3 studies, apremilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, demonstrated lower response rates in the biologic‐exposed than in the biologic‐naive population (28, 29, 30). In patients treated with the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib (31, 32), response rates were lower in patients who had an inadequate response to bDMARDs, including TNFi, than in TNFi‐naive patients. A similar trend was observed with the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib (33, 34), although it should be noted that the study evaluating patients with an inadequate response to bDMARDS included patients who had received three or more prior bDMARDs. However, response rates with these alternate agents in the TNFi‐experienced study populations generally appear better than those observed in patients with PsA who switched to a second and third TNFi in the DANBIO registry (35).

It is unknown why patients who are unresponsive to TNFi would improve on an alternate mechanism of action. Potentially, the different mode of action may more specifically target the disease pathophysiology specific to a particular PsA subtype or patient phenotype. In previous studies, no difference in treatment persistence with a first TNFi was demonstrated between patients with axial versus peripheral involvement and between those with polyarticular versus oligoarticular PsA (36). However, characteristics such as more severe disease and female sex, together with obesity, have been associated with a higher likelihood of switching biologic therapies (36, 37). Further research is needed to identify whether or not specific therapies may be more likely to achieve clinical response in certain patients with PsA; however, it is encouraging that guselkumab is effective across subgroups defined by multiple baseline characteristics in both TNFi‐IR and biologic‐naive patients with PsA (14, 15, 17). Biomarker analyses evaluating molecular distinctions between TNFi‐IR and biologic‐naive patients with PsA and associations with clinical response are underway. Additionally, a pragmatic study, EVOLUTION (NCT05669833), has been specifically designed to evaluate if switching to guselkumab is more effective than cycling to a second TNFi in patients who experienced inadequate efficacy with a prior TNFi.

The TNFi‐experienced cohort in DISCOVER‐1 was limited to approximately 30% of the study population, and it is a heterogenous group regarding reasons for discontinuation of prior TNFi therapy. Additionally, reliable comparisons of guselkumab efficacy and safety with and without concomitant MTX within the TNFi‐experienced cohort could not be performed because of the relatively small sample sizes. However, results for this cohort, which provides a broad representation of patients with PsA who have received prior treatment with TNFi and require additional therapy, support the findings of TNFi‐IR patients treated with guselkumab in the COSMOS study. Finally, this study was not designed with the primary purpose of comparing TNFi‐naive with TNFi‐experienced patients with PsA, and, as such, many of the analyses are post hoc.

Treatment with 100 mg of guselkumab Q4W and Q8W resulted in improvements in multiple domains of PsA, including musculoskeletal and skin symptoms, enthesitis, and patient‐reported outcomes (including physical function), that were maintained through 1 year in both TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐experienced populations. A consistent and positive safety profile was observed in both TNFi populations and was consistent with the guselkumab safety profile established for PsA and psoriasis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Federico Zazzetti had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Ritchlin, Deodhar, Soriano, Kollmeier, Xu, Shawi, Sheng, Helliwell.

Acquisition of data

Kollmeier, Xu, Jiang, Sheng.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Ritchlin, Deodhar, Boehncke, Soriano, Kollmeier, Xu, Zazzetti, Shawi, Jiang, Sheng, Helliwell.

ROLE OF THE STUDY SPONSOR

Janssen Research & Development facilitated the study design, provided writing assistance for the manuscript, and reviewed and approved the manuscript prior to submission. The authors independently collected the data, interpreted the results, and had the final decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Substantive manuscript review was provided by Cynthia Guzzo, MD (consultant funded by Janssen). Medical writing support was provided by Rebecca Clemente, PhD (Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC), under the direction of the authors in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022;175:1298–1304). Janssen Research & Development also approved this manuscript prior to submission.

Supporting information

Disclosure Form

This study was funded by Janssen Research & Development, LLC.

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinicaltrials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through the Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Author disclosures are available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/downloadSupplement?doi=10.1002%2Facr2.11523&file=acr211523-sup-0001-Disclosureform.pdf.

REFERENCES

- 1. Suzuki E, Mellins ED, Gershwin ME, et al. The IL‐23/IL‐17 axis in psoriatic arthritis. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1060–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mease P. Psoriatic arthritis and spondyloarthritis assessment and management update. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2013;25:287–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glintborg B, Loft AG, Omerovic E, et al. To switch or not to switch: results of a nationwide guideline of mandatory switching from originator to biosimilar etanercept. One‐year treatment outcomes in 2061 patients with inflammatory arthritis from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harrold LR, Stolshek BS, Rebello S, et al. Impact of prior biologic use on persistence of treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis enrolled in the US Corrona registry. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saad AA, Ashcroft DM, Watson KD, et al. Persistence with anti‐tumour necrosis factor therapies in patients with psoriatic arthritis: observational study from the British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costello R, David T, Jani M. Impact of adverse events associated with medications in the treatment and prevention of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 2019;41:1376–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Girolomoni G, Altomare G, Ayala F, et al. Safety of anti‐TNFα agents in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2012;34:548–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kamata M, Tada Y. Efficacy and safety of biologics for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their impact on comorbidities: a literature review. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tremfya [package insert]. Horsham (PA): Janssen Biotech, Inc.; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boehncke WH, Brembilla NC, Nissen MJ. Guselkumab: the first selective IL‐23 inhibitor for active psoriatic arthritis in adults. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2021;17:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, et al. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic‐naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER‐1): a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;395:1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Guselkumab in biologic‐naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER‐2): a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;395:1126–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ritchlin CT, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, et al. Guselkumab, an inhibitor of the IL‐23p19 subunit, provides sustained improvement in signs and symptoms of active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of a phase III randomised study of patients who were biologic‐naive or TNFα inhibitor‐experienced. RMD Open 2021;7:e001457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coates LC, Gossec L, Theander E, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who are inadequate responders to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results through one year of a phase IIIb, randomised, controlled study (COSMOS). Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:359–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase III, double‐blinded, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76:405–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double‐blind, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76:418–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sewerin P, Borchert K, Meise D, et al. Real‐world treatment persistence with biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs among German patients with psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective database study. Rheumatol Ther 2021;8:483–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Orbai AM, Husni ME, Gladman DD, et al. Secukinumab efficacy on psoriatic arthritis GRAPPA‐OMERACT core domains in patients with or without prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use: pooled analysis of four phase 3 studies. Rheumatol Ther 2021;8:1223–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Orbai AM, Gratacos J, Turkiewicz A, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis and inadequate response to TNF inhibitors: 3‐year follow‐up (SPIRIT‐P2). Rheumatol Ther 2021;8:199–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mease PJ, Kavanaugh A, Coates LC, et al. Prediction and benefits of minimal disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis and active skin disease in the ADEPT trial. RMD Open 2017;3:e000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rahman P, Mease PJ, Helliwell PS, et al. Guselkumab demonstrated an independent treatment effect in reducing fatigue after adjustment for clinical response‐results from two phase 3 clinical trials of 1120 patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2021;23:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foley P, Gordon K, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab compared with adalimumab and placebo for psoriasis in specific body regions: a secondary analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154:676–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman, P., Boehncke, W.‐H., Mease, P. J, et al. Safety of guselkumab with and without prior TNF‐α inhibitor treatment: Pooled results across four studies in patients with psoriatic arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology 2023; jrheum.220928. 10.3899/jrheum.220928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti‐IL‐12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non‐biological and biological anti‐tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6‐month and 1‐year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:990–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cutolo M, Myerson GE, Fleischmann RM, et al. A phase III, randomized, controlled trial of apremilast in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results of the PALACE 2 trial. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1724–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edwards CJ, Blanco FJ, Crowley J, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with psoriatic arthritis and current skin involvement: a phase III, randomised, controlled trial (PALACE 3). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1065–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez‐Reino JJ, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo‐controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1020–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1525–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1537–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McInnes IB, Kato K, Magrey M, et al. Upadacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to non‐biological therapy: 56‐week data from the phase 3 SELECT‐PsA 1 study. RMD Open 2021;7:e001838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mease PJ, Lertratanakul A, Papp KA, et al. Upadacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis and inadequate response to biologics: 56‐week data from the randomized controlled phase 3 SELECT‐PsA 2 study. Rheumatol Ther 2021;8:903–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Krogh NS, et al. Clinical response, drug survival, and predictors thereof among 548 patients with psoriatic arthritis who switched tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: results from the Danish Nationwide DANBIO Registry. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Costa L, Perricone C, Chimenti MS, et al. Switching between biological treatments in psoriatic arthritis: a review of the evidence. Drugs R D 2017;17:509–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mulder ML, Wenink MH, Vriezekolk JE. Being overweight is associated with not reaching low disease activity in women but not men with psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61:770–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclosure Form