Abstract

Background

Despite the availability of effective medications, tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a serious global public health problem, primarily affecting low and middle-income nations. Measuring and reporting TB treatment outcomes and identifying associated factors are fundamental parts of TB treatment. The goal of this study was to look at the outcomes of TB treatment and the factors that influence them in Sekota, Northeast Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

A facility-based retrospective study was conducted in Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital, Sekota town, Northeast Ethiopia. All TB patients who registered in the TB log book and had known treatment outcomes at the treatment center between January 1, 2015, and December 30, 2021, were included in this study. The data was gathered utilizing a pretested structured data extraction format that comprised demographic, clinical, and treatment outcome characteristics. Data were entered, cleaned, and analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression analysis were employed. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 552 registered TB patients' data were reviewed. Of these, 49.6% were male, 94.4% were new cases, 64.9% were presented with pulmonary TB, and 18.3% were HIV positive. Regarding the treatment outcome, 11.6% were cured, 82.2% completed their treatment, 1.1% had failed treatment, 1.3% were lost to follow-up, and the remaining 3.8% died during the follow-up. The overall treatment success rate among TB patients was 93.8%. The maximum number of successful treatment outcomes was 94.9% in 2021, while the lowest was 86.7% in 2020. The pattern of successful treatment results changes with the number of years of treatment. In the current study, being a new TB patient (AOR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.31–7.32) and being an HIV-negative patient (AOR = 2.64, 95% CI: 1.20–5.8) were factors independently associated with a successful treatment outcome.

Conclusion

The rate of successful TB treatment outcomes in the current study was satisfactory. This achievement should be maintained and enhanced further by developing effective monitoring systems and educating patients about medication adherence.

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a serious public health issue worldwide, accounting for the 13th leading cause of death and the second leading infectious killer after COVID-19 [1]. Although highly effective treatment has been available for decades, TB remains a challenge, especially in low-income countries [2]. Tuberculosis epidemiology is also closely connected with social and economic conditions, which makes its prevention, care, and control more challenging [3]. In 2021, a projected 10.6 million people became ill with tuberculosis, up from 10.1 million in 2020, and 1.6 million people died from tuberculosis, including 187,000 people living with HIV [1]. Tuberculosis is the leading cause of death among communicable diseases in Ethiopia [4].

In Ethiopia, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of TB cases have been practiced for years as per the guidelines of the Directly Observed Treatment Short-course (DOTS) program that started in 1997 [5]. Despite the DOTS program's adoption, many reports from around the country have suggested that there are obstacles to improving TB treatment outcomes. These include differences in treatment-seeking behavior, poor compliance, the occurrence of HIV/TB coinfection, discrepancies in expert qualifications, and the presence of medication resistance [6, 7].

According to the Ethiopian national TB and leprosy control strategic plan, it has been planned to successfully treat 90% of confirmed TB cases and enroll them in the DOTS program. Moreover, regarding the 2020 Global TB Report, the successful TB treatment outcome in Ethiopia was 88% by the year 2019 [8]. Such results have only been obtained with vigorous treatment and follow-up. Several studies [9–11] conducted in various parts of Ethiopia revealed varying rates of treatment effectiveness and associated factors.

Determining TB trends and treatment outcomes in health facilities is critical for better disease management and control efforts. Nonetheless, data from Ethiopia's rural, urban, and suburban environments demonstrate heterogeneity and inconsistency. Routine monitoring of the extent of the treatment outcome and its drivers is vital; however, studies on TB treatment outcomes and associated factors are rare in Northeast Ethiopia, particularly in the Waghemra zone. As a result, the findings of this study are critical for the study area as well as at the national level in order to reduce the burden and identify predictors of good treatment outcomes. As a result, the purpose of this study was to evaluate TB treatment outcomes and associated factors at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital in Sekota town.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Area, and Period

A facility-based retrospective study was conducted in Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital in Sekota town, the capital of Waghemra zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital is found in the Northeast part of Ethiopia, 720 km from the capital city of Addis Ababa. It serves a total population of 536,129. The hospital provides all types of clinical and diagnostic services, as well as supervisory and mentoring services, to the nearby health centers found in the Waghemra zone. It is the center for TB diagnosis and treatment, including multi-drug or extended drug resistance TB (MDR/XDR-TB) patient treatment, care, and management. TB patient registration documents were reviewed from January 1, 2015, to December 30, 2021. The study period to review the seven-year (2015–2021) data was from January 1 to April 30, 2022.

2.2. Study Population

All TB patients who started treatment in the DOTS clinic and had complete medical records on TB treatment outcomes at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital in the past seven years were included in the study. Patients who had incomplete data from the logbook were excluded from the study.

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

A total of 589 tuberculosis patients were treated from 2015 to 2021 at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital. Then, 552 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in the study.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Data Collection Tool

A structured data abstraction checklist was created and used to extract pertinent information. For content validity, the checklist was pretested and standardized among 5% of the study population at Dehana District Hospital. A data abstraction checklist based on both dependent and independent factors was created. The checklist covers sociodemographics, HIV status, ART status, CPT initiation, tuberculosis type, patient category, and therapy outcome.

2.4.2. Data Collection Procedure

Data were gathered from a secondary source, the TB patients' registration record book. In the tuberculosis clinic, statistics were gathered through medical record reviews of patients using a pre-prepared standard checklist. Supervisors for data collection included two BSc nurses and one laboratory technologist. The TB registry was used to obtain demographic and clinical information such as age, gender, type of tuberculosis, HIV status, cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT), and ART status.

2.4.3. Data Quality Control

The data collectors were instructed for one day about the goal and data abstraction techniques prior to the real data collection. Prior to the actual data collection at Dehana District Hospital, a 5% pretest was conducted to evaluate the validity of the data abstraction checklist. As a result, changes and adjustments were made to the data abstraction checklist. The lead investigator also kept a close eye on the activity on a regular basis. Furthermore, prior to the start of the research, the lead investigator meticulously entered and cleaned the data.

2.5. Definitions of Outcome Terms

The clinical definition and treatment outcome of patients were recorded in accordance with the Ethiopian National TB and Leprosy Control Program (NTLCP) standards and WHO recommendations [12]. In this study, therapy outcomes are classified as successful or unsuccessful. Cases with a successful treatment outcome included “cured” and “treatment completed” cases. In contrast, unsuccessful treatment outcomes included “treatment failure” cases, “defaulters,” and patients who “died.” The patient is deemed cured if he or she completes treatment with a negative bacteriological result at the end of the treatment. The treatment is considered “complete” if the patient completed treatment but did not receive a bacteriological result. Treatment failure: a patient who remained smear-positive during treatment or relapsed five months later; or a patient who was PTB negative at the start but became smear-positive at the end of the intensive phase. A defaulter is a patient who has been on treatment for at least four weeks and has had two or more weeks of therapy interrupted in a row. The patient died as a result of any cause during the course of treatment.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

After checking the data for completeness and consistency, the data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 25. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are presented using descriptive statistics. The findings are presented using frequency tables, graphs, and percentages. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine the relationship between dependent and independent variables. Explanatory variables with a p value of <0.25 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The assumption of model fitness was checked by the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p=0.752).

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of TB Patients

All TB patients who started treatment in the DOTS clinic and documented their registration in the TB log book at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital from January 1, 2015, to December 30, 2021, were included in this study. A total of 589 TB patients were treated from 2015 to 2021 at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital. Of these, 552 had known treatment outcomes that were included in the study. However, 37 TB patients with incomplete data were excluded from the study. From the total participants included in this study, 278/552 (50.4%) cases were female, 175/552 (31.7%) were between 30 and 44 years old, 331/552 (60.0%) were urban dwellers, and 272/552 (49.3%) weighed 38 to 54 kg (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of TB patients at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital, Sekota town, Northeast Ethiopia from January 2015 to December 2021.

| Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 274 | 49.6 |

| Female | 278 | 50.4 | |

|

| |||

| Age category | <15 | 55 | 10.0 |

| 15–29 | 157 | 28.4 | |

| 30–44 | 175 | 31.7 | |

| 45–59 | 110 | 19.9 | |

| ≥60 | 55 | 10.0 | |

|

| |||

| Pretreatment weight | Less than 20 kg | 29 | 5.3 |

| 20–29 kg | 36 | 6.5 | |

| 30–37 kg | 121 | 21.9 | |

| 38–54 kg | 272 | 49.3 | |

| >54 kg | 94 | 17.0 | |

|

| |||

| District | Sekota town | 391 | 70.8 |

| Sekota zuria | 148 | 26.8 | |

| Others | 13 | 2.4 | |

|

| |||

| Residence | Urban | 331 | 60.0 |

| Rural | 221 | 40.0 | |

|

| |||

| Year of treatment | 2015 | 67 | 12.1 |

| 2016 | 82 | 14.9 | |

| 2017 | 99 | 17.9 | |

| 2018 | 64 | 11.6 | |

| 2019 | 78 | 14.1 | |

| 2020 | 45 | 8.2 | |

| 2021 | 117 | 21.2 | |

3.2. Clinical Characteristics of TB Patients

Regarding the TB category, 521/552 (94.4%) were new TB cases. Three hundred fifty-eight (358/552 (64.9%)) of the patients presented with pulmonary TB, and of these, 70/358 (19.6%) were smear-positive. A significant number of the patients, 101/552 (18.3%), were HIV-TB coinfected patients; of these, 100/101 (99.0%) and 99/101 (98.0%) were on ART and took cotrimoxazole preventive treatment (CPT), respectively. During the intensive phase of treatment, 548/552 (99.3%) of TB patients received a combination of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RHZE) as part of their treatment regimen. Moreover, all patients were treated with the standard RH regimen during the continuation phase of therapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of TB patients at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital, Sekota town, Northeast Ethiopia from 2015 to 2021.

| Variables | Category | Frequency (n) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of TB | SPPTB | 70 | 12.7 |

| SNPTB | 288 | 52.2 | |

| EPTB | 194 | 35.1 | |

|

| |||

| TB category | New case | 521 | 94.4 |

| Retreatment | 31 | 5.6 | |

|

| |||

| HIV status | HIV-positive | 101 | 18.3 |

| HIV-negative | 451 | 81.7 | |

|

| |||

| Cotrimoxazole preventive therapy initiated | Yes | 99 | 98.0 |

| No | 2 | 2.0 | |

|

| |||

| ART initiated | Yes | 100 | 99.0 |

| No | 1 | 1.0 | |

|

| |||

| Treatment regimen during the intensive phase | RHZE | 548 | 99.3 |

| SERHZ | 4 | 0.7 | |

3.3. Trends in Types of TB Cases across the Seven Years

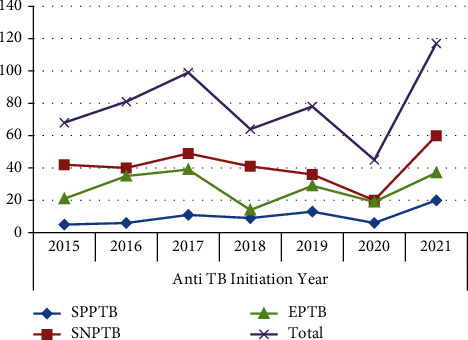

The trend for all forms of TB showed a fluctuating trend. From 2015 to 2017, the number of smear-positive PTB, smear-negative PTB, and EPTB cases increased. However, all forms of TB showed a slight decline from 2017 to 2020 with a certain fluctuation, whereas the number of TB cases increased in the last year of 2021 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends of TB types diagnosed at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital, Sekota town, Northeast Ethiopia from 2015 to 2021.

3.4. Treatment Success and Associated Factors

The overall rate of successful TB treatment outcomes (cured and treatment completed) among patients enrolled in the DOTS program was 518/552 (93.8%). Of these, 64/552 (11.6%) were cured, and 454/552 (82.2%) had completed their treatment. The treatment success rate of HIV-coinfected TB patients included in the TB treatment outcome was 87/101 (86.1%). From a total of 34/552 (6.2%) unsuccessful TB treatment outcome cases, 6/552 (1.1%) had failed treatment, 7/552 (1.3%) were lost to follow-up, and the remaining 21/552 (3.8%) died during the follow-up. Patients from rural areas, women, EPTB patients, and HIV-negative patients had higher treatment success rates. The cure rate showed an increment during the review period, from 5/68 (7.4%) in the year 2015 to 18/117 (15.4%) in the year 2021. The death rate also showed an increment for six consecutive years (2015–2020) and a decline in 2021. However, the rate of treatment completion showed a reduction in the six years (2015–2020) from 61/68 (89.7%) to 32/45 (71.1%) and then started to increase in the final year of the study period (2021) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of treatment outcome with socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of TB patients at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital, Sekota town, Northeast Ethiopia from 2015 to 2021.

| Characteristics | Treatment outcome | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cured (%) | Treatment completed (%) | Treatment failed (%) | Lost to follow-up (%) | Died (%) | |||

| Sex | Male | 29 (10.6) | 226 (82.5) | 2 (0.7) | 7 (2.6) | 10 (3.6) | 274 |

| Female | 35 (12.6) | 228 (83.2) | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (4.0) | 278 | |

|

| |||||||

| Age category | <15 | 2 (3.6) | 49 (89.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) | 55 |

| 15–29 | 35 (22.3) | 116 (73.9) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) | 157 | |

| 30–44 | 19 (10.9) | 140 (80.0) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) | 12 (6.9) | 175 | |

| 45–59 | 6 (5.5) | 97 (88.2) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (3.6) | 110 | |

| ≥60 | 2 (3.6) | 52 (94.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 55 | |

|

| |||||||

| Pretreatment weight | <20 kg | 2 (6.9) | 23 (79.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 3 (10.3) | 29 |

| 20–29 kg | 5 (13.9) | 30 (83.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 36 | |

| 30–37 kg | 16 (13.2) | 94 (77.7) | 2 (1.7)) | 1 (0.8) | 8 (6.6) | 121 | |

| 38–54 kg | 29 (10.7) | 228 (83.8) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) | 8 (2.9) | 272 | |

| >54 kg | 12 (12.8) | 79 (84.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | 94 | |

|

| |||||||

| District | Sekota town | 56 (14.3) | 310 (79.3) | 6 (1.5) | 4 (1.0) | 15 (3.8) | 391 |

| Sekota zuria | 8 (5.4) | 131 (88.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.0) | 6 (4.1) | 148 | |

| Others | 0 (0.0) | 13 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 | |

|

| |||||||

| Place of residence | Urban | 46 (13.9) | 263 (79.5) | 5 (1.5) | 4 (1.2) | 13 (3.9) | 331 |

| Rural | 18 (8.1) | 191 (86.4) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.4) | 8 (3.6) | 221 | |

|

| |||||||

| Year of treatment | 2015 | 5 (7.4) | 61 (89.7) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 68 |

| 2016 | 5 (6.2) | 72 (88.9) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | 81 | |

| 2017 | 12 (12.1) | 84 (84.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.0) | 99 | |

| 2018 | 8 (12.5) | 51 (79.7) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.25) | 64 | |

| 2019 | 9 (11.5) | 61 (78.2) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6.4) | 78 | |

| 2020 | 7 (15.6) | 32 (71.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (13.3) | 45 | |

| 2021 | 18 (15.4) | 93 (79.5) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.7) | 117 | |

|

| |||||||

| Type of TB | SPPTB | 61 (87.1) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.7) | 70 |

| SNPTB | 1 (0.3) | 268 (93.1) | 2 (0.69) | 5 (1.7) | 12 (4.2) | 288 | |

| EPTB | 2 (1.0) | 184 (94.8) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.6) | 194 | |

|

| |||||||

| TB category | New case | 57 (10.9) | 432 (82.9) | 6 (1.2) | 6 (1.2) | 20 (3.8) | 521 |

| Retreatment | 7 (22.6) | 22 (71.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 31 | |

|

| |||||||

| HIV status | HIV-positive | 15 (14.9) | 72 (71.3) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.0) | 11 (10.9) | 101 |

| HIV-negative | 49 (10.9) | 382 (84.7) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) | 10 (2.2) | 451 | |

|

| |||||||

| Total | 64 (11.6) | 454 (82.2) | 6 (1.1) | 7 (1.3) | 21 (3.8) | 552 | |

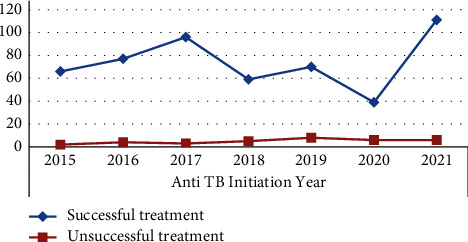

The maximum number of successful treatment outcomes was 111/117 (94.9%) in 2021, while the lowest was 39/45 (86.7%) in 2020. The pattern of successful treatment results changes with the number of years of treatment. This means that the trend of successful TB treatment results rose gradually from 2015 to 2017. However, the number of TB patients who had successful treatment varied greatly from 2017 to 2020, peaking in 2021 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trend of successful TB treatment outcomes of TB patients at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital, Sekota, Northeast Ethiopia from 2015 to 2021.

In the bivariate analysis, variables with a p value of <0.25 were age, pretreatment weight, year of treatment initiated, type of TB, patient category, and HIV status. In the multivariate logistic regression, TB patient category and HIV status were independently and significantly associated with the treatment outcome. The odds of treatment success were 1.75 (AOR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.31–7.32) times higher among new TB patients than retreatment TB cases. Similarly, HIV-negative patients had 2.64 times higher odds of (AOR = 2.64, 95% CI: 1.20–5.8) having treatment success than HIV-positive patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis of treatment outcome with socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of TB patients at Tefera Hailu Memorial General Hospital, Sekota town, Northeast Ethiopia from 2015 to 2021.

| Variables | Successful TB treatment outcome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | COR (95% CI) | p value | AOR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | ||||||

| Sex | Male | 255 (93.1) | 19 (6.9) | 1 | |||

| Female | 263 (94.6) | 15 (5.4) | 1.31 (0.65–2.63) | 0.453 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Age category | <15 | 51 (92.7) | 4 (7.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 15–29 | 151 (96.2) | 6 (3.8) | 4.24 (0.49–39.17)∗ | 0.203 | 1.32 (0.09–20.58) | 0.842 | |

| 30–44 | 159 (90.9) | 16 (9.1) | 2.15 (0.25–18.23)∗ | 0.184 | 1.43 (0.16–12.88) | 0.751 | |

| 45–59 | 103 (93.6) | 7 (6.4) | 5.43 (0.70–41.95)∗ | 0.105 | 3.48 (0.43–28.17) | 0.242 | |

| ≥60 | 54 (98.2) | 1 (1.8) | 3.67 (0.44–30.61)∗ | 0.230 | 1.69 (0.46–6.16) | 0.428 | |

|

| |||||||

| Pretreatment weight | <20 kg | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 20–29 kg | 35 (97.2) | 1 (2.8) | 4.85 (1.02–23.12)∗ | 0.047 | 8.56 (0.94–77.86) | 0.057 | |

| 30–37 kg | 110 (90.9) | 11 (9.1) | 0.87 (0.09–8.61)∗ | 0.203 | 1.19 (0.09–15.17) | 0.893 | |

| 38–54 kg | 257 (94.5) | 15 (5.5) | 3.03 (0.82–11.20)∗ | 0.096 | 2.67 (0.69–10.40) | 0.157 | |

| >54 kg | 91 (96.8) | 3 (3.2) | 1.77 (0.50–6.26)∗ | 0.375 | 1.688 (0.46–6.16) | 0.428 | |

|

| |||||||

| Residence | Urban | 309 (93.4) | 22 (6.6) | 0.81 (0.39–1.67) | 0.561 | ||

| Rural | 209 (94.6) | 12 (5.4) | 1 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Year of treatment | 2015 | 66 (97.1) | 2 (2.9) | 1 | |||

| 2016 | 77 (95.1) | 4 (4.9) | 0.56 (0.11–2.86)∗ | 0.216 | 0.94 (0.17–5.10) | 0.945 | |

| 2017 | 96 (97.0) | 3 (3.0) | 0.96 (0.26–3.52)∗ | 0.152 | 1.28 (0.33–5.04) | 0.721 | |

| 2018 | 59 (92.2) | 5 (7.8) | 0.58 (0.14–2.37)∗ | 0.147 | 0.74 (0.174–3.15) | 0.683 | |

| 2019 | 70 (89.7) | 8 (10.3) | 1.57 (0.46–5.35)∗ | 0.123 | 1.965 (0.53–7.30) | 0.313 | |

| 2020 | 39 (86.7) | 6 (13.3) | 2.11 (0.70–6.35)∗ | 0.082 | 2.48 (0.77–7.96) | 0.1282 | |

| 2021 | 111 (94.9) | 6 (5.1) | 2.85 (0.87–9.35)∗ | 0.085 | 3.54 (0.99–12.69) | 0.053 | |

|

| |||||||

| Type of TB | SPPTB | 63 (90.0) | 7 (10.0) | 0.64 (0.26–1.58)∗ | 0.229 | 2.18 (0.69–6.85) | 0.183 |

| SNPTB | 269 (93.4) | 19 (6.6) | 0.39 (0.14–1.11)∗ | 0.078 | 1.37 (0.56–3.38) | 0.491 | |

| EPTB | 186 (95.9) | 8 (4.1) | 1 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| TB category | New case | 489 (93.9) | 32 (6.1) | 1.05 (0.54–5.12)∗ | 0.144 | 1.75 (1.31–7.32)∗ | 0.020 |

| Retreatment | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | 1 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| HIV status | HIV-positive | 87 (86.1) | 14 (13.9) | 1 | |||

| HIV-negative | 431 (95.6) | 20 (4.4) | 3.47 (1.69–7.13)∗ | 0.001 | 2.64 (1.20–5.80)∗ | 0.016 | |

∗ Statistically significant at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

An institution-based seven-year retrospective study was done to extract and review 552 registered TB patients at the DOTS clinic. Females were nearly equal to males in this study, accounting for 50.4%. In contrast to this study, previous studies reported that males were dominant, such as a study in Dessie [9], Goba [10], and Harar [11]. The burden of TB was higher among the age groups of 15–29 and 30–44 years, with 28.4% and 31.7%, respectively, which was in agreement with the previous study in southern Ethiopia [13]. This might be indicating a negative influence of TB on the socioeconomic state of society, particularly in low-income countries.

Of all patients enrolled in the DOTS clinic, 18.3% were HIV-positive, comparable with the reports done in Woldia (18.5%) [14], East Gojam (22.9%) [6], Goba (17.4%) [10], and Harar (22.8%) [11]. Human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals with low immunity might be coinfected with a variety of pathogens, including TB, in varying degrees of clinical manifestations. Previous studies in Debre Tabor (12.7%) [15], Gondar (13.4%) [16], Tigray region (8.6%) [17], Iran (2.7%) [18] and Malaysia (6.6%) [19] found lower HIV-TB coinfection. This high TB-HIV coinfection in our study could be due to the higher proportion of HIV in urban settings, where the majority of the study participants lived. More than half of the participants (52.2%) had smear-negative pulmonary TB, which was higher than the study reported in East Gojam (42%) [6], and Wolyta Sodo (34.5%) [13]. Patients who came to the health facility with TB signs and symptoms and had a negative result for AFB microscopy were clinically diagnosed as smear-negative PTB. This smear microscopy-based detection might contribute to lowering the rate of smear-positive PTB cases, as most of the health facilities in Ethiopia have been using AFB microscopy due to limited resources. Smear microscopy has low sensitivity (40–45%) and might contribute to lower notification rates of smear-positive PTB [20].

The trend analysis result showed that TB cases were fluctuating over the past seven years but ultimately showed an increment in the most recent year. Other studies reported in Northern Ethiopia [21] and the Sidama Zone [22] found a similar fluctuating but increasing trend. Different factors may contribute to the variation of TB cases, including altitude variations, ecological and natural variables, social and economic factors, control efforts, population vulnerability, and drug resistance [23].

Although trends in the number of cases vary by year, 2020 showed a significantly lower number of cases. This could be attributed to the reorganization of hospitals and health centers for COVID-19 care, detection, and isolation; patients' fear of being isolated if their infection is COVID-19; patients' fear of contracting COVID-19 in health facilities; and the reallocation of healthcare professionals for COVID-19 care and management in Ethiopia during the pandemic in 2020. An increase in the number of cases was observed since 2017 and reached its peak in 2021. A considerable decline in TB case detection due to missed diagnoses has resulted in an accumulation of undiscovered TB, resulting in continued TB transmission and higher rates of latent TB infection. Moreover, huge numbers of people immigrated from their local areas to Sekota town due to internal conflict in Ethiopia. This also might be due to the high rates of TB transmission among homeless persons, injection drug users, and persons with HIV infection, according to the WHO protocol [24].

The overall magnitude of successful TB treatment outcomes was 93.8% (95% CI, 91.8–95.7). Of these, 11.6% were cured, and 82.2% completed their treatment. The overall successful treatment outcome recorded in the present study was in agreement with the retrospective studies conducted in Gojam, Northwest Ethiopia, 94.8% [25], 92.4% in Hawassa [26], 92.5% in Harar [11], 91.9% in East Wollega [27], 94.9% in Pakistan [28], 91.7% in Iran [29], 95.1% in Russia [30], and the WHO 2030 international target of 90% [8].

On the contrary, the successful treatment outcome of this study was higher than reports from other studies, with a treatment success rate of 80.7% in Woldia [14], 90.1% in Debre Tabor [20], 89.5% in Northern Ethiopia [21], 91.2% in Goba (91.2%) [10], 80.4% in Tepi [31], 82.5% in Wolayta Sodo [13], 86.0% pooled prevalence in Ethiopia [7], 75.7% in Sudan [32], 57.7% in Nigeria [33], and 50.7% in China [34]. This could be due to improved patient adherence to anti-TB medication, an increased focus on TB prevention and control programs in our study, and changes in study duration.

In our findings, 6.2% of TB patients had an unsuccessful or poor TB treatment outcome. Poor adherence to anti-TB treatment due to treatment failures lost to follow-up and irregular treatment might lead to more severe illness, treatment failure, relapse, a longer infection, drug resistance, and even death. Defaulting and irregular anti-TB medicine intake presented a problem and a worry for both the patient and the community and needed to be addressed appropriately. One of the most difficult issues during the TB control campaign is finding treatment failures and ensuring follow-up. The rate of treatment failure among TB patients was 1.1%, which was lower than the findings documented in Debre Tabor (3.5%) [15] and in Tigray Region (3.7%) [17]. Our study's lower treatment failure rate could be attributed to better implementation of DOT strategies such as defaulter tracing, supervision, and health education activities for inpatients, outpatients, and the community.

In our study, 1.3% of the TB patients were identified as lost to follow-up. The findings were similar to those of similar studies conducted in Hosanna (1.4%) [35] and Sidama, Ethiopia (1.0%) [22]. This figure was lower than the reports in Northern Ethiopia (2.5%) [36], Hawassa (2.6%) [26], Wolayta Sodo (11.2%) [13], Harar (2.4%) [11], Dilla (11.1%) [37], and East Wollega (2.9%) [27]. This low loss to follow-up rate could be attributed to the community's effective execution of the DOT's plan, counseling services, and good healthcare utilization and seeking behavior. In addition, the TB-related death rate was 3.8% in this study. This figure was in line with reports in Gondar (3.27%) [38], Tigray Region (3.9%) [17], Addis Ababa (3.7%) [39], and Harar (3.9%) [11]. However, this finding was lower than the mortality rates reported for Wolayta Sodo (4.7%) [13], Goba (5.1%) [10], Nigeria (11.5%) [40], and Yemen (12.2%) [41]. This could be explained by greater access to and utilization of TB control services, as well as increased disease awareness in our study area.

According to our findings, patients treated in 2021 have a higher chance of a successful TB treatment outcome than those treated between 2015 and 2020. This finding is supported by a study conducted at Woldia [14], Awi Zone, Northwest Ethiopia [42], and Addis Ababa [43]. This could be due to the patient's better awareness of the treatment schedule, improved adherence to anti-TB treatment, and receiving better care over time. Identification of factors related to TB treatment results is critical in order to address the factors responsible for poor treatment outcomes. Our findings revealed that being a new TB case and HIV-negative was independently and significantly associated with successful treatment outcomes.

New TB cases were nearly twice as likely as their counterparts to have successful treatment outcomes. This finding was in agreement with studies conducted in the Arsi Zone, Ethiopia [44], Somalia [45], Nigeria [40], and Turkey [46]. Recurrence instances, on the other hand, could be drug-resistant TB, a recurrence due to a weakened immune system, or other comorbidities that enhance the probability of an unsatisfactory treatment outcome. Furthermore, individuals who had HIV-negative TB patients were nearly three times more likely than HIV-positive patients to have good treatment outcomes. The finding was similar to the study in Woldia [14] and in Harar, Eastern Ethiopia [11]. This could be explained by the fact that HIV-negative TB patients have better immune systems than HIV-positive patients, and HIV-positive patients may not take the medicine as prescribed due to concerns about drug interactions and side effects [47].

4.1. Limitation of the Study

As retrospective secondary data was obtained from the TB registration log book, it was not possible to determine all factors that could affect the patient's treatment outcomes. Moreover, since the study was conducted in a single hospital, it was difficult to generalize the findings to all TB patients in the country.

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

The success rate of TB treatment in the study area was generally good when compared to other studies conducted in Ethiopia, and it was higher than the aim established by the national TB and leprosy control program in Ethiopia. Being a new TB case and being HIV-negative were both predictors of effective treatment outcomes. Early detection of TB and the timely beginning of effective anti-TB drug treatment, as well as increased HIV prevention and health education activities, are critical for improving the treatment outcomes of TB patients. Furthermore, more prospective studies are needed to determine other predictors that may affect TB patient' treatment success.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to the Tefera Hailu Memorial Hospital TB clinic staff for their unwavering support and cooperation in making this study a success.

Data Availability

All relevant data are included in the published article.

Ethical Approval

An official letter was sought from the Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, and permission to undertake the retrospective study was obtained from the Waghemra Zone Health Bureau before the data collection. Patient-informed consent was not required because the data were obtained from a retrospective record review. The data were collected after written informed consent was obtained from the clinical director. The information obtained was made anonymous and deidentified prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality. The study was also conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Habtu Debash, Jemberu Nega, Habtye Bisetegn, and Daniel Getacher Feleke conceived and designed the study, prepared the proposal, supervised data collection, and analyzed and interpreted the data. Habtu Debash, Jemberu Nega, Gebru Tesfaw, Hussen Ebrahim, Alemu Gedefie, Mihret Tilahun, Ousman Mohammed, Ermiyas Alemayehu, Melaku Ashagrie Belete, Abdurahaman Seid, and Agumas Shibabaw had participated in data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of the result; collecting scientific literature; critical appraisal of articles for inclusion; and analysis and interpretation of the findings. Habtu Debash drafted and prepared the manuscript for publication. Agumas Shibabaw, Habtye Bisetegn, Daniel Getacher Feleke, and Melaku Ashagrie Belete critically reviewed the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Bagcchi S. WHO’s global tuberculosis report 2022. The Lancet Microbe . 2023;4(1):p. e20. doi: 10.1016/s2666-5247(22)00359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding E. WHO global progress report on tuberculosis elimination. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine . 2020;8(1):p. 19. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raviglione M., Sulis G. Tuberculosis 2015: burden, challenges and strategy for control and elimination. Infectious Disease Reports . 2016;8(2):p. 6570. doi: 10.4081/idr.2016.6570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kebede Y., Andargie G., Gebeyehu A., et al. Tuberculosis and HIV are the leading causes of adult death in northwest Ethiopia: evidence from verbal autopsy data of Dabat health and demographic surveillance system, 2007–2013. Population Health Metrics . 2017;15:27–13. doi: 10.1186/s12963-017-0139-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biadglegne F., Sack U., Rodloff A. C. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Ethiopia: efforts to expand diagnostic services, treatment and care. Antimicrobial Resistance And Infection Control . 2014;3(1):31–10. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meseret Tadele M., Tizazu G., Temesgen Denekew H., Tesfa Gebeyehu M. Successful tuberculosis treatment outcome in East Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study design. Alexandria Journal of Medicine . 2022;58(1):60–68. doi: 10.1080/20905068.2022.2090064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seid M. A., Ayalew M. B., Muche E. A., Gebreyohannes E. A., Abegaz T. M. Drug-susceptible tuberculosis treatment success and associated factors in Ethiopia from 2005 to 2017: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open . 2018;8(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022111.e022111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Global. Tuberculosis Report 2020 . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seid A., Metaferia Y. Factors associated with treatment delay among newly diagnosed tuberculosis patients in Dessie city and surroundings, Northern Central Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health . 2018;18(1):931–1013. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5823-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamo A., Mama M., Solomon D., Mohammed M. Treatment outcomes and predictors among tuberculosis patients at madda walabu university Goba referral hospital, southeast Ethiopia. Infection and Drug Resistance . 2021;13:4763–4771. doi: 10.2147/idr.s285542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tola A., Minshore K. M., Ayele Y., Mekuria A. N. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and associated factors among TB patients attending public hospitals in Harar town, Eastern Ethiopia: a five-year retrospective study. Tuberculosis research and treatment . 2019;2019:11. doi: 10.1155/2019/1503219.1503219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health Ethiopia. Manual for Tuberculosis, Leprosy and TB/HIV Prevention and Control Program . Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Health Ethiopia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teferi M. Y., Didana L. D., Hailu T., Woldesenbet S. G., Bekele S., Mihret A. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and associated factors among tuberculosis patients at Wolayta Sodo Teaching and Referral Hospital, Southern Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Journal of Public Health Research . 2021;10(3):p. 2046. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2021.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Getie A., Alemnew B. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and associated factors among patients treated at Woldia general hospital in NortheastNortheast Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Infection and Drug Resistance . 2020;13:3423–3429. doi: 10.2147/idr.s275568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melese A., Zeleke B., Ewnete B. Treatment outcome and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in Debre Tabor, Northwestern Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Tuberculosis research and treatment . 2016;2016:8. doi: 10.1155/2016/1354356.1354356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinshaw Y., Alemu S., Fekadu A., Gizachew M. Successful TB treatment outcome and its associated factors among TB/HIV co-infected patients attending Gondar University Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: an institution based cross-sectional study. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2017;17(1):132–139. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2238-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berhe G., Enquselassie F., Aseffa A. Treatment outcome of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health . 2012;12(1):537–539. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khazaei S., Hassanzadeh J., Rezaeian S., et al. Treatment outcome of new smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Hamadan, Iran: a registry-based cross-sectional study. Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis . 2016;65(4):825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcdt.2016.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liew S. M., Khoo E. M., Ho B. K., et al. Tuberculosis in Malaysia: predictors of treatment outcomes in a national registry. International Journal of Tuberculosis & Lung Disease . 2015;19(7):764–771. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worku S., Derbie A., Mekonnen D., Biadglegne F. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment short-course at Debre Tabor General Hospital, northwest Ethiopia: nine-years retrospective study. Infectious diseases of poverty . 2018;7(1):16–17. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0395-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdulkader M., van Aken I., Niguse S., Hailekiros H., Spigt M. Treatment outcomes and their trend among tuberculosis patients treated at peripheral health settings of Northern Ethiopia between 2009 and 2014: a registry-based retrospective analysis. BMC Research Notes . 2019;12(1):786–795. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4824-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dangisso M. H., Datiko D. G., Lindtjørn B. Trends of tuberculosis case notification and treatment outcomes in the Sidama Zone, southern Ethiopia: ten-year retrospective trend analysis in urban-rural settings. PLoS One . 2014;9(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114225.e114225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millet J. P., Moreno A., Fina L., et al. Factors that influence current tuberculosis epidemiology. European Spine Journal . 2013;22(4):539–548. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2334-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakaya J., Petersen E., Nantanda R., et al. The WHO Global Tuberculosis 2021 Report–not so good news and turning the tide back to End TB. International Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2022;124(1):26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebreegziabher S. B., Yimer S. A., Bjune G. A. Tuberculosis case notification and treatment outcomes in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a five-year retrospective study. Journal of Tuberculosis Research . 2016;4(1):23–33. doi: 10.4236/jtr.2016.41004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsegaye B., Bedewi Z., Asnake S. L. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at adare general hospital, Hawassa, southern Ethiopia.(A five year retrospective study) Research Square . 2019;2019(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muluye A. B., Kebamo S., Teklie T., Alemkere G. Poor treatment outcomes and its determinants among tuberculosis patients in selected health facilities in East Wollega, Western Ethiopia. PLoS One . 2018;13(10):2062277–e206315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jehangir F., Hashmi R., Lateef T. K. K. A., et al. Prevalence and outcomes of tuberculosis treatment in a primary care center in Karachi, Pakistan. Archives of Medicine . 2020;12(6):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alavi S. M., Salmanzadeh S., Bakhtiyariniya P., Albagi A., Hemmatnia F., Alavi L. Prevalence and treatment outcome of pulmonary and extrapulmonary pediatric tuberculosis in southwestern Iran. Caspian journal of internal medicine . 2015;6(4):213–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterlikov S., Testov V., Aksenova V. Treatment outcomes of new TB cases among children in Russia. European Respiratory Journal . 2015;46 doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2015.PA1521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zewudie S., Sirna A., Terefe A., Asres A. Trends and outcomes of tuberculosis among cases on directly observed short course treatment (DOTS) at Tepi public health center Southwest Ethiopia. Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases . 2021;25 doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2021.100264.100264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Legesse T., Elduma M. H., Awad N. M., et al. Trends of tuberculosis treatment outcomes of notified cases in three refugee camps in Sudan: a four-year retrospective analysis, 2014–2017. Sudan Journal of Medical Sciences . 2021;16(2):259–275. doi: 10.18502/sjms.v16i2.9293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sariem C. N., Odumosu P., Dapar M. P., Musa J., Ibrahim L., Aguiyi J. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a fifteen-year retrospective study in jos-north and mangu, plateau state, north-Central Nigeria. BMC Public Health . 2020;20(1):1224–1311. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09289-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Q., Yang D., Qiu B., et al. Drug resistance gene mutations and treatment outcomes in MDR-TB: a prospective study in Eastern China. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases . 2021;15(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009068.e0009068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammed T., Daniel K., Helamo D., Leta T. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients in nigist Eleni Mohammed general hospital, hosanna, southern nations, nationalities and peoples region, Ethiopia: a five year (June 2009 to August 2014) retrospective study. Archives of Public Health . 2017;75(1):16–10. doi: 10.1186/s13690-017-0184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adane K., Spigt M., Dinant G. J. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and predictors in northern Ethiopian prisons: a five-year retrospective analysis. BMC Pulmonary Medicine . 2018;18(1):37–38. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0600-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woldesemayat E. M., Azeze Z. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis at Dilla referral hospital, gedeo zone, southern Ethiopia: a retrospective study. PLoS One . 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249369.e0249369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atalell K. A., Birhan Tebeje N., Ekubagewargies D. T. Survival and predictors of mortality among children co-infected with tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. A retrospective follow-up study. PLoS One . 2018;13(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197145.e0197145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Getahun B., Ameni G., Biadgilign S., Medhin G. Mortality and associated risk factors in a cohort of tuberculosis patients treated under DOTS programme in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2011;11(1):127–128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Babatunde O. Factors affecting treatment outcomes of tuberculosis in a tertiary health center in Southwestern Nigeria. International Review of Social Sciences and Humanities . 2013;4(2):209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaber A. A. S., Ibrahim B. Evaluation of risk factors associated with drug-resistant tuberculosis in Yemen: data from centres with high drug resistance. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2019;19(1):464–469. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4069-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alemu T., Gutema H. Trend in magnitude of tuberculosis in Awi Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a five-year tuberculosis surveillance data analysis. BMC Research Notes . 2019;12(1):209–215. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Getahun B., Ameni G., Medhin G., Biadgilign S. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2013;17(5):521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamusse S. D., Demissie M., Teshome D., Lindtjørn B. Fifteen-year trend in treatment outcomes among patients with pulmonary smear-positive tuberculosis and its determinants in Arsi Zone, Central Ethiopia. Global Health Action . 2014;7(1):p. 25382. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali M. K., Karanja S., Karama M. Factors associated with tuberculosis treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients attending tuberculosis treatment centres in 2016-2017 in Mogadishu, Somalia. The Pan African medical journal . 2017;28(1):p. 197. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.197.13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sengul A., Akturk U. A., Aydemir Y., Kaya N., Kocak N. D., Tasolar F. T. Factors affecting successful treatment outcomes in pulmonary tuberculosis: a single-center experience in Turkey, 2005–2011. The journal of infection in developing countries . 2015;9(08):821–828. doi: 10.3855/jidc.5925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puga M. A. M., Bandeira L. M., Pompilio M. A., et al. Screening for HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis infections among bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis prisoners: an urgent action required. PLoS One . 2019;14(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221265.e0221265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the published article.