Keywords: blood brain barrier, microparticles, neutrophil adherence, thrombospondin

Abstract

This project investigated glial-based lymphatic (glymphatic) function and its role in a murine model of decompression sickness (DCS). DCS pathophysiology is traditionally viewed as being related to gas bubble formation from insoluble gas on decompression. However, a body of work implicates a role for a subset of inflammatory extracellular vesicles, 0.1 to 1 µm microparticles (MPs) that are elevated in human and rodent models in response to high gas pressure and rise further after decompression. Herein, we describe immunohistochemical and Western blot evidence showing that following high air pressure exposure, there are elevations of astrocyte NF-κB and microglial-ionized calcium-binding adaptor protein-1 (IBA-1) along with fluorescence contrast and MRI findings of an increase in glymphatic flow. Concomitant elevations of central nervous system-derived MPs coexpressing thrombospondin-1 (TSP) drain to deep cervical nodes and then to blood where they cause neutrophil activation. A new set of blood-borne MPs are generated that express filamentous actin at the surface that exacerbate neutrophil activation. Blood-brain barrier integrity is disrupted due to activated neutrophil sequestration that causes further astrocyte and microglial perturbation. When postdecompression node or blood MPs are injected into naïve mice, the same spectrum of abnormalities occur and they are blocked with coadministration of antibody to TSP. We conclude that high pressure/decompression causes neuroinflammation with an increased glymphatic flow. The resulting systemic liberation of TSP-expressing MPs sustains the neuroinflammatory cycle lasting for days.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY A murine model of central nervous system (CNS) decompression sickness demonstrates that high gas pressure activates astrocytes and microglia triggering inflammatory microparticle (MP) production. Thrombospondin-expressing MPs are released from the CNS via enhanced glymphatic flow to the systemic circulation where they activate neutrophils. Secondary production of neutrophil-derived MPs causes further cell activation and neutrophil adherence to the brain microvasculature establishing a feed-forward neuroinflammatory cycle.

INTRODUCTION

Decompression sickness (DCS) pathophysiology is traditionally viewed as related to gas bubble formation from insoluble gas on decompression. However, the inconsistent presence of bubbles in human studies has prompted investigations focused instead on inflammatory pathways (1–3). A body of work implicates a subset of extracellular vesicles, 0.1–1 µm microparticles (MPs) that are elevated in humans and rodent models exposed to high gas pressure and rise further after decompression (4–14). MPs initiate a systemic inflammatory response related to neutrophil activation (13, 15–17).

DCS is often related to a return to ambient pressure from deep sea excursions while breathing compressed air, but also can occur after diving while holding one’s breath. The prevalence of central nervous system (CNS) manifestations when DCS occurs ranges from ∼30% for compressed air divers to 56% for commercial fisherman breath-hold divers who typically make 60 or more ∼1-min dives per day to depths of 30–40 m of seawater (1, 18–20). Theoretical calculations indicate there is a risk for inert gas supersaturation with these repetitive breath-hold exposures (21). However, breath-hold divers only rarely are found to have intravascular bubbles and when found, they are of low magnitude and clear rapidly from the circulation (4, 21). In a field study of breath-hold human divers, we reported significant elevations of circulating MPs that bore no relationship to intravascular bubbles (4).

High pressures of nitrogen and similar gases activate leukocytes via an oxidative stress process that triggers MPs production (22). The pathway triggering MP formation also activates the leukocyte NOD-like receptor, pyrin-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome responsible for producing mature interleukin (IL)-1β (22, 23). Inflammasome assembly correlates with MP production and the MPs containing high amounts of IL-1β are the primary factor causing diffuse vascular damage in the murine DCS model (14, 24). When these MPs are purified and injected into naïve mice, they cause the same spectrum of injuries as seen in decompressed mice (13, 14, 25).

The glymphatic system drives cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) into the brain parenchyma via astrocyte aquaporin 4 (AQP4) water channels followed by passage of interstitial fluid out of the brain via perivenous channels and ultimately, to deep cervical lymph nodes (26). These structures are depicted in the graphical abstract. This facilitates brain fluid clearance and waste removal in association with advection along meningeal lymphatics (27–33). Neuroinflammation is thought to perturb glymphatic function with an initial increase of flow, but this is not well documented (34). We hypothesized that because of the high-pressure gas effects on leukocytes, glial cells are perturbed causing a disturbance of glymphatic function.

Astrocytes respond to oxidative stress with NF-κB activation which, among other events, results in the generation of TSP-1 and -2 and a variety of extracellular vesicles (35). TSP-1 is a neurogenic factor and can protect mitochondrial functions, however, TSP-1 engagement by several varieties of leukocytes will cause priming, chemotaxis, NLRP3 inflammasome formation/interleukin-1β production, enhance endothelial attachment, and spreading (36, 37). Our results indicate that exposure to high-pressure air and decompression perturb glial cells that increase glymphatic flow along with the release of inflammatory MPs to the circulation that perpetuate a neuroinflammatory cycle.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Materials

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. Antibodies were validated from the purchased company with indicated host specificity and the data sheets of each product were supplied as below: anti-annexin V-PE (Becton Dickinson/PharMingen, BD, San Jose, CA, Cat. No. 556421), anti-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, Cat. No. A-2066), anti-AQP4 (Abcam, Cat. No. ab81355), anti-Ly6G eFluor450 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, Cat. No. 48–5931-82), anti-mouse MPO-PE (Hycult Biotech, Plymouth Meeting, PA, Cat. No. HM1051PE-100), anti-mouse CD31 BV510 (BD Cat. No. 563089), anti-CD41 PerCP Cy5.5 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, Cat. No. 133918), anti-GFAP Brilliant Violet 421 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, Cat. No. 644719), anti-TMEM119-APC (Abcam, Cat. No. ab225494), anti-NPR AF-790 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, Cat. No. sc-390081), anti-MBP PerCP (Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, Cat. No. NBP2-22121PCP), anti-TSP-1 (Santa Cruz, Cat. No. 393504 and 393504FITC), p65 subunit of NF-κB (Abcam, Cat. No. ab32536), and anti-p65 subunit of NF-κB, anti-phosphorylated at serine 536 (Phospho-Ser536) p65 NF-κB) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, Cat. No. 3031). Verification that anti-actin recognizes β-actin was shown by Western blot and mass spectroscopy in a prior publication (25). Antibodies for flow cytometry and Western blots were specifically for that usage as documented by the manufacturers and used at the concentrations recommended. Positive staining in flow cytometry was determined following the fluorescence-minus-one control test.

Animals

All aspects of this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments were performed using young, adult (10–12 wk) mice with approximately equal numbers of males and females in all experimental groups. C57BL/6J mice (Mus musculus) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in the university animal facility.

Mice were housed in the university animal facility with a 12/12-h light-dark cycle. Housing and all experiments were conducted at 22°C–24°C and 40%–70% humidity. Mice received water ad libitum and were fed Laboratory Rodent Diet 5001 (PMI Nutritional Inc., Brentwood, MO). Male and female mice, used in approximately equal numbers, were left to breathe room air (control) or subjected to 2-h exposure to air pressure at 790 kPa. No mice died and none exhibited overt evidence of functional compromise as may be consistent with decompression sickness, the same findings as we have made in prior studies with this model (13, 25).

The mice were anesthetized and euthanized for blood and tissue collection at times spanning immediately postexposure to 4 days. Randomization of mice for experimentation was performed by first collecting all mice to be used on a day into a single plastic cage and then randomly selecting an individual mouse for use as the daily control or for an intervention group. Studies were done over a span of 9 mo with acclimatized mice purchased in groups of 6–12 at biweekly intervals. Mice were used according to a block design where individual blocks represented mice selected as control or pressure exposure.

Data were scored and analyzed in a blinded manner such that the scorer did not know an animal’s group assignment. All mice involved in this project were included in the data analysis, and none were excluded. To minimize animal usage and maximize information gain, experiments were largely designed to use both blood and tissue from the same animals. Mice were anesthetized [intraperitoneal administration of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg)], skin was prepared by swabbing with betadine, and blood was obtained into heparinized syringes by aortic puncture, before tissue harvesting.

Cervical Lymph Node MP Acquisition

Cervical lymph nodes were identified and removed from mice as described previously (38). Two to six nodes from a mouse were weighed, placed in a petri dish, and finely cut to pieces with a scalpel. The minced nodes were suspended as 20 µg/mL digestion buffer (DMEM, 2% FBS containing 250 µg dispase) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C with vortexing at 15-min intervals. Tissue aggregates were then broken up by repeated passage through a narrow, flamed tip Pasteur pipette, and 0.1 mL of 50 mM EDTA/mL of node suspension was added to aid dispersion of the particles. After 10-min incubation, the suspension was diluted 1.6-fold with PBS and passed through a 40-µm filter. The suspension was then centrifuged at 600 g for 5 min, the pellet discarded and recentrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min. MPs in the supernatant were then analyzed. Detailed methods along with representative box plots showing the enumeration strategy are published (38).

Blood MP Acquisition and Processing

Blood-borne MPs were isolated and prepared for analysis by flow cytometry as previously described (13, 38). Briefly, heparinized blood was centrifuged for 5 min at 1,500 g. EDTA was added to the supernatant to achieve 12.5 mM to prevent MPs aggregation, centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min, and supernatant was used for analysis.

MPs for Reinjection

MPs donor mice were exposed to the 2-h pressure protocol and euthanized 2 h later. Cervical node and blood MPs were isolated and blood MPs were separated based on F-actin expression using phalloidin-conjugated magnetic beads as previously described (38). For both cervical node and blood MPs, after the initial 15,000 g, the supernatant was obtained, it was parceled among centrifuge tubes at a ratio of 250 µL + 4 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min (typically 3–4 tubes/experiment were used). Supernatant (4 mL) was then carefully removed and the pellet containing the MPs was resuspended in sterile PBS. The MPs were counted and diluted so that 60,000 MPs in 200 µL of PBS were intravenously injected via a tail vein into naïve mice. Recipient mice were then euthanized 2 h later to evaluate glymphatic flow or vascular permeability and elevations of brain inflammatory proteins. Where indicated, for some mice, 30 min before intravenous injections, MPs were first combined with 5 µg of anti-TSP IgG.

MP Analysis

All reagents and solutions used for MP isolation and analysis were filtered with 0.1-µm filter (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). MPs were analyzed as described previously (13, 16). In brief, flow cytometry was performed with an eight-color, triple laser MACSQuant Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec Corp., Auburn, CA) using MACSQuantify software version 2.5 to analyze data. MACSQuant was calibrated every other day with calibration beads ((Miltenyi Biotec Corp., Auburn, CA). Forward and side scatter were set at a logarithmic gain. Photomultiplier tube voltage and triggers were optimized to detect submicron particles. Microbeads of three different diameters, 0.3 µm (Sigma, Inc., St. Louis, MO), 1.0 µm, and 3.0 µm (Spherotech, Inc., Lake Forest, IL), were used for initial settings and before each experiment as an internal control. Samples were suspended in annexin-binding buffer solution (1:10 vol/vol in distilled water; BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA), and antibodies are as listed above. Examples of blood-borne and cervical particle analysis have been published previously (38, 39). All reagents and solutions used for MP analysis were sterile and filtered (0.1 μm filter). MPs were defined as annexin V-positive particles with diameters of 0.3–1 µm diameter. The concentration of MPs in sample tubes was determined by MACSQuant Analyzer according to exact volume of solution from which MPs were analyzed.

Colloidal Silica Endothelium-Enriched Tissue Homogenates and Vascular Permeability Assay

Mice were anesthetized, exsanguinated, and perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove residual blood and then with lysine-fixable tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated dextran (2 × 106 Da, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), followed by colloidal silica according to published methods (13, 16). After centrifugation, the endothelium-enriched pellets were obtained for analysis from the brain and leg skeletal muscle. Vascular leakage was quantified as rhodamine fluorescence after values were normalized to that obtained with a control mouse included in each experiment because of variability in rhodamine-dextran manufacturing as described previously (13). Neutrophil sequestration was evaluated by performing Western blots on tissue homogenates, probing for Ly6G and myeloperoxidase (MPO), and normalizing band density to β-actin bands on the same blots following our published procedures (13, 16).

MRI Assessment of Glymphatic Flow

Images were obtained in the University Core Facility Bruker BioSpec 70/30USR Avance III 7 Tesla horizontal bore MR scanner. The system is equipped with a BGA12S gradient system and interfaced to a Bruker Paravision 6.0 console. A 72-mm Bruker linear-volume radio frequency (RF) coil was used as a transmitter and a Bruker four-element 1H RF array coil served as a receiver. Mice were anesthetized and then maintained with 1.75% isoflurane, and a MR-compatible small-animal gating system was used to monitor respiration rate and maintain body temperature at 35°C–37°C. After initial calibration and T2-weighted anatomic acquisitions, paramagnetic contrast (gadodiamide, Gd, 0.15 mmol (300 µL)/20 g mouse was injected IV at 50 µL/min and a series of 5 min 3 D T1-weighted fast low angle shot acquisitions were obtained in the sagittal view (TR-13.455 ms, TE = 3.82 ms, flip angle = 25°, average = 4, field of view = 18 × 18 ×18 mm3, imaging resolution = 0.15 × 0.15 × 0.40 mm3). Image processing consisted of head motion correction and voxel-by-voxel conversion to % baseline signal.

Cisterna Magna Injections

Mice were anesthetized for surgery 2 or 24 h after pressure treatment with isoflurane and placed in stereotactic head holder. After cisterna magna exposure, a 30-gage needle was inserted that had been attached to PE tubing and microsyringe. Infusion proceeded for 5 min at 2 µL/min with artificial CSF (filter sterilized 119 mM NaCl, 26.2 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.3 mM MgCl2, 10 mm glucose at 37°C) containing 0.5% ovalbumin (MW 45 kDa) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 and 0.5% cadaverine (MW 0.6 kDa) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. At 30 min after the start of infusion, brains were perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, brains were removed, and postfixed in same solution for 24 h. Coronal 100-µm brain sections were collected in sequence from 1.7 mm anterior to 0.7 mm posterior of the bregma from each mouse, mounted on slides, and subjected to epifluorescence and later immunohistochemical imaging.

Immunohistochemical preparation involved rinsing slides three times with PBS followed by permeabilizing and blocking by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with PBS containing 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 0.3% (vol/vol) glycine, 5% (vol/vol) normal goat serum, and 5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum. Slides were then incubated with a 1:200 dilutions of anti-GFAP, NF-κB, or IBA-1 monoclonal IgG antibody at room temperature for 2 h. After rinsing three times with PBS, the slides were incubated with a 1:200 dilutions of Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig for 1 h followed in some studies by counterstaining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Images were acquired using a Nikon inverted-stage confocal microscope equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63/1.4 numerical aperture oil objective. Fluorophore excitation was provided by 405-, 488- and 633-nm laser lines, and resulting fluorescence was separated using 420–480-, 505- and 650-nm band pass filters.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for four or more independent experiments with analysis using SigmaStat (Jandel Scientific, San Jose, CA). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Statistical analysis in each assay is detailed in figure legends. For two group comparisons, a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test was used. For multiple group comparisons, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Newman-Keuls post hoc test was used. For all studies, we deemed a result to be statistically significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

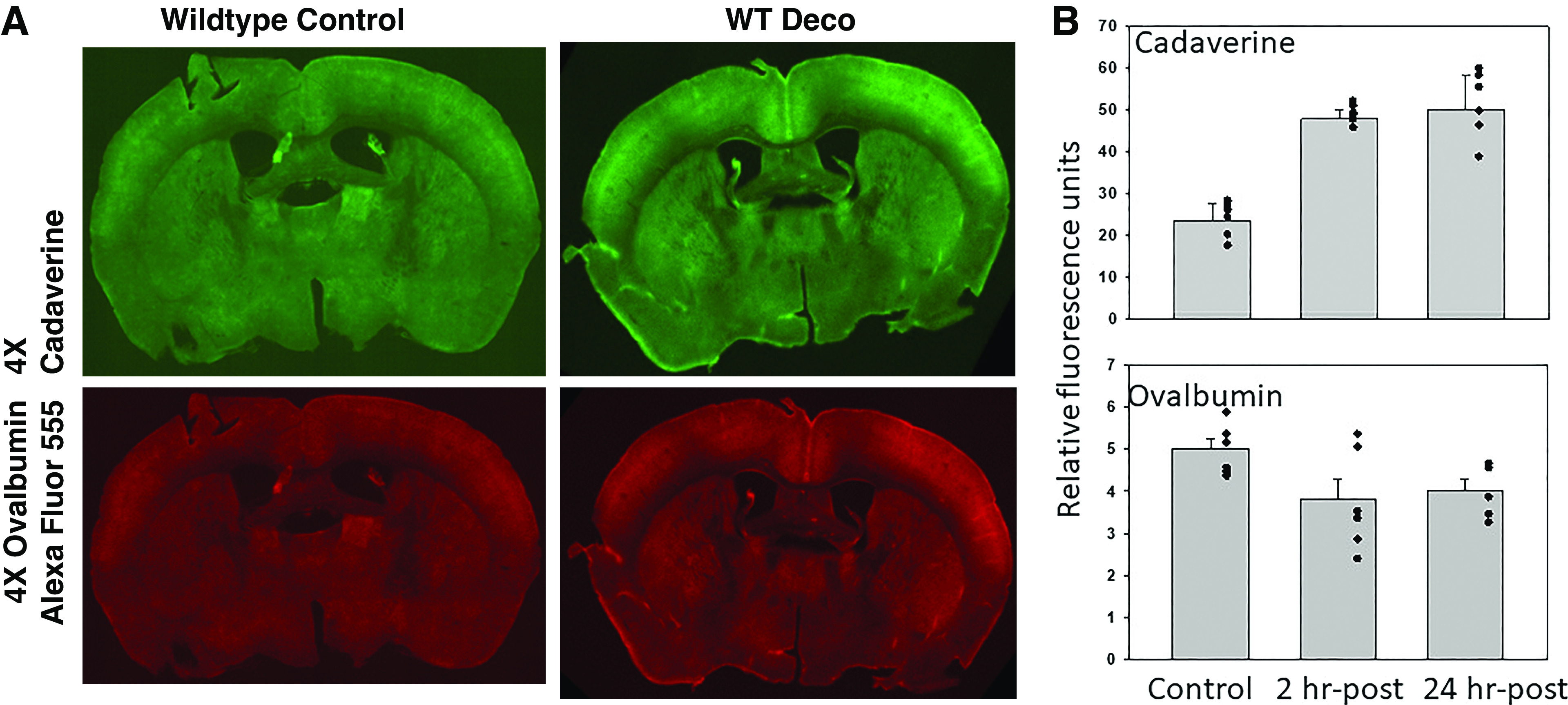

Cisterna Magna Injections and Glymphatic Flow

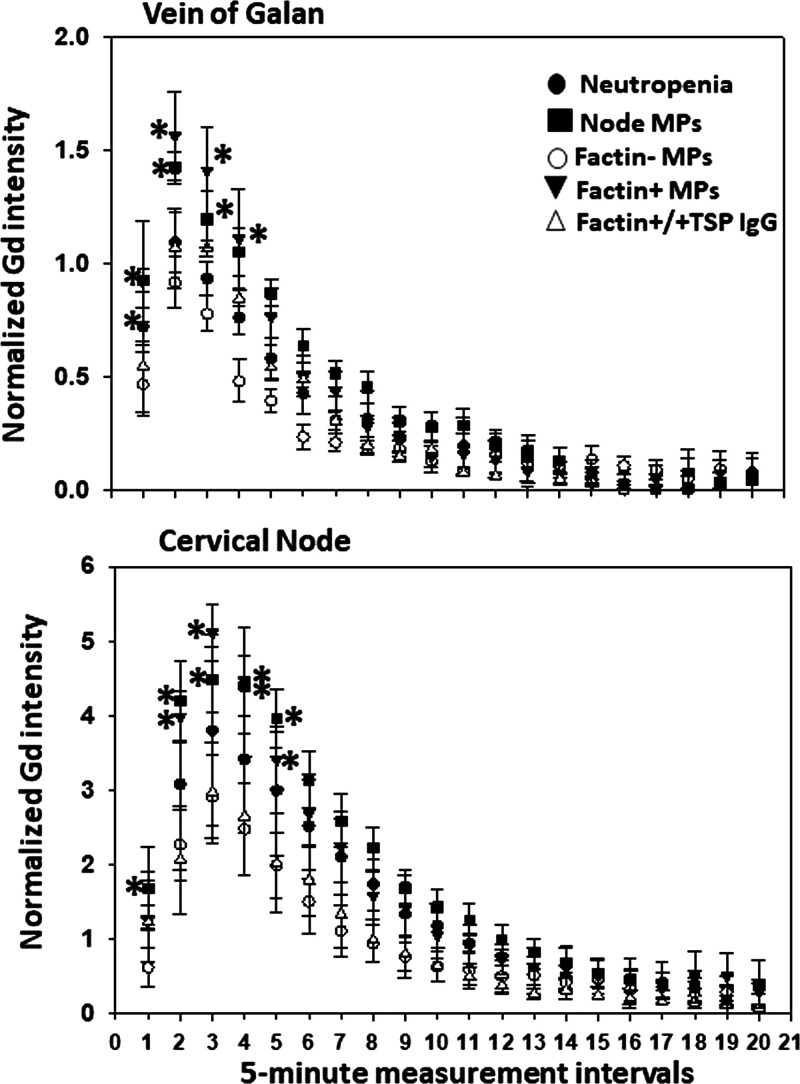

We first evaluated glymphatic flow by intracisternal injections of fluorescent protein tracers. Following decompression from the standard DCS model (2-h exposure to 790 kPa air pressure), mice were injected with a solution containing fluorescent ovalbumin (MW 45 kDa) and cadaverine (MW 640.61 kDa). Ovalbumin passes from the perivascular space to brain interstitial fluid (ISF) via clefts between astrocytes (paracellular path) versus smaller cadaverine that can also enter ISF via astrocytic uptake (transcellular path) (40). Cadaverine uptake nearly doubled after decompression, whereas the ovalbumin signal was not statistically significantly different (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Glymphatic flow assessment by cisterna magna injections. A shows typical 100-µm coronal brain section fluorescence after injections of ovalbumin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 and cadaverine conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. B shows quantitative evaluation of protein uptake in control mice and mice studied 2- or 24-h postexposure to 790 kPa air pressure for 2 h. Values are means ± SD (for control, 3 male and 3 female mice; for 2-h post-air pressure group, 4 male and 3 female mice; for 24-hour post-air pressure group, 3 male and 3 female mice). Evaluations were performed on 8 brain sections/mouse; individual data points are also shown. WTDeco, wild-type mouse subjected to pressure/decompression.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Glymphatic Flow

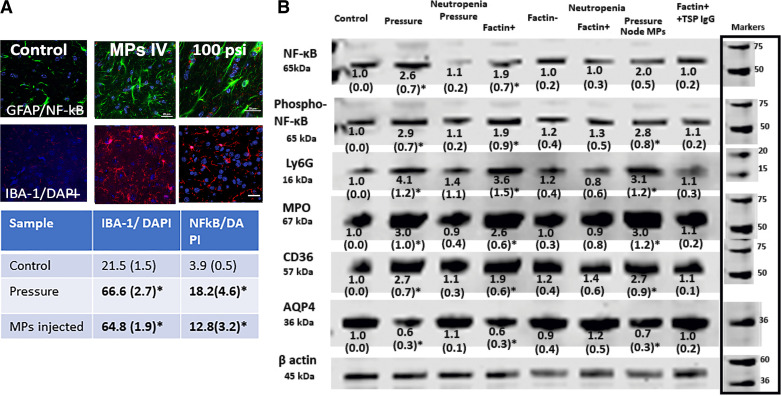

To circumvent potential artifacts due to intracranial pressure alterations from puncturing the cisterna magna, more extensive assessments of glymphatic function were made with MRI following intravenous injection of gadolinium (Gd) (41). As shown in Fig. 2A, the Gd signal is robust near the vein of Galan and at deep cervical nodes. Representative control and decompression mouse images are shown in Fig. 2B. We quantified flow using 1-mm regions of interest at the vein of Galan and deep cervical nodes and normalized the signal by including a vial containing 60 mM Gd beneath the mouse skull within the scanning field. Signal intensity was significantly higher during the first five 5-min measuring periods in decompressed mice (Fig. 2C). The same increased flow results were observed in mice studied at 24 h and 4 days postdecompression (data not shown). Because previous studies have demonstrated a role for neutrophil activation in decompression pathophysiology (13, 15, 22, 24), glymphatic flow was also evaluated in neutropenic mice. Although glymphatic flow was not perturbed when mice were rendered neutropenic by injections of antibody to the neutrophil Ly6G protein (data not shown), we found that glymphatic flow in decompressed mice was also not statistically significantly different from control, suggesting the involvement of systemic responses (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Glymphatic flow assessment by gadolinium (Gd) contrast MRI. A shows a typical image highlighting the signal near the vein of Galan and at deep cervical nodes. Quantified flow was assessed using 1-mm regions of interest at these sites and normalized by including a 60 mM Gd vial beneath the mouse skull within the scanning field. Images of control and decompressed mice are shown in B. Quantifications (C) were plotted on ordinates showing normalized Gd signal (means ± SD, n = 8 mice/group, *P < 0.05, repeated-measures ANOVA) and abscissa showing sequential 5-min 3 D T1-weighted fast low angle shot acquisitions obtained after image calibration and injection of paramagnetic contrast [gadodiamide, Gd, 0.15 mmol (300 µL)/20 g mouse was injected IV at 50 µL/min]. Note that data obtained from mice studied 4 days after decompression demonstrated the same flow increases as those in C done 2 h after decompression (data not shown). DCS, decompression sickness.

Figure 3.

Glymphatic flow assessment in neutropenic mice and naïve mice injected with isolated MPs. Normalized Gd signals at the vein of Galan and deep cervical nodes for control and 2 h post decompression mice first rendered neutropenic by injections of anti-Ly6G antibodies 4 days prior to study. There were no statistically significant differences between control (Fig. 2) and decompressed mice. Also shown are normalized Gd signals for naïve mice injected with blood-borne F-actin-positive or F-actin-negative MPs isolated from 2 h post decompression mice. *Values for F-actin positive and cervical node MPs isolated from decompressed mice were statistically significantly different by repeated-measures ANOVA (n = 4/group). Also shown are normalized Gd signals for naïve mice injected with postdecompression mouse F-actin-positive MPs first incubated with antibody to TSP-1. Anti-TSP-incubated MPs caused no statistically significant glymphatic flow elevation. Gd, gadolinium; MP, microparticle; TSP, thrombospondin-1.

Evidence of Neuroinflammation

Glial cell activation was evident in brains of decompressed mice based on morphological changes, expression of IBA-1 and NF-κB p65 (Fig. 4A). Changes in astrocytes and microglia were diffuse, with no discernible differences among brain regions. To quantify brain neuroinflammation in an alternative manner, Western blots were prepared using homogenates of brains perfused with positively charged colloidal silica in a manner, as reported by others, to enrich samples for endothelium and adjacent glial cells (42). Fig. 4B is a representative blot where, compared with control (lane 1), at 2 h postdecompression (lane 2), there were elevations of the p65 subunit of NF-κB, serine 536 phosphorylated (Phospho-Ser536) p65 NF-κB, Ly6G, MPO, and CD36 with loss of AQP4. Values in neutropenic mice subjected to pressure/decompression were not significantly different from control.

Figure 4.

Neuroinflammation in postpressure mouse brains. A shows typical immunohistochemical images with 20-μm scale bars in lower right of each image. The table below the figure shows means ± SD (n = 6 mice, with 4–6 brain slices quantified per mouse) number of cells in brain slices that demonstrated IBA-1 concurrent with DAPI nuclear staining and triple staining with GFAP, p65 subunit of NF-κB, and DAPI in control mice, 2 h postdecompression mice and mice intravenously injected with 60,000 F-actin-positive MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression. B shows a representative brain homogenate Western blot where numbers below each band indicate means ± SD (n = 4–9 mouse brains per lane) band densities relative to β-actin of control samples from replicate studies. Blots for each protein are contiguous, no cuts/insertions were made. Molecular weight markers for blots are shown on the right margin. Numbers with an asterisk indicate values statistically significant from control (P < 0.05 ANOVA). Blots were probed for the p65 subunit of NF-κB, serine 536 phosphorylated p65 NF-κB (labeled phospho-NF-κB), Ly6G, MPO, CD36, and AQP4. Lanes reflect control mice, those euthanized 2 h postdecompression, neutropenic mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression (note that control neutropenic mice exhibited no statistically significant differences from normal controls but data not shown), naïve mice injected with 60,000 F-actin-positive MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression, naïve mice injected with 60,000 F-actin-negative MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression, neutropenic mice injected with 60,000 F-actin-positive MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression, naïve mice injected with 60,000 cervical node MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression, naïve mice injected with 60,000 F-actin-positive MPs from mice postdecompression that had first been incubated with antibody to TSP-1. MP, microparticle; MPO, myeloperoxidase; TSP, thrombospondin-1.

Microparticle Analysis

Inflammatory MPs can be found in deep cervical nodes in response to brain insults (38, 43). MPs were isolated from deep cervical nodes and blood, and the cells responsible for MP production were evaluated by assessing the expression of cell-specific proteins on the MP surface (Table 1, Node and Blood). Significant elevations of the total number of MPs occurred in nodes and blood of mice at 2 h postdecompression. The same statistically significant increases were also found at 4 days postdecompression (data not shown). Notably, although neutropenic mice subjected to pressure/decompression exhibited significant elevations of the total number of node MPs and those expressing GFAP or TSP, no significant MPs elevations were observed in blood. Prior work has identified elevations of neutrophil-derived MPs due to cell activation and production of MPs expressing filamentous (F-)actin (assessed by phalloidin binding) that are responsible for diffuse vascular damage (25). MPs expressing the neutrophil-specific Ly6G protein and those expressing F-actin were elevated postdecompression (Table 1, Blood) but not in neutropenic mice. F-actin-expressing MPs were also assessed in deep cervical nodes but found to not be statistically significantly different between control [2.9% (SD 3.1, n = 9)] and decompressed mice [6.0% (SD 5.5, n = 9)]. Activation of neutrophils by high pressure/decompression was shown as elevations of membrane-bound myeloperoxidase (MPO) and the CD18 component of the β2 integrin (Table 1, Neutrophils).

Table 1.

Microparticle counts and vascular leakage

| Control | Deco (D) | LowN | D+LowN | IV F+MPs | F+MPs/LowN | F-MPs | F+MP+IgG | DNodeMPs | ContMPs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node | ||||||||||

| MPs/µL | 1,120 (73) | 4,088 (979) | 1,380 (98) | 3,830 (948) | 3,805 (578) | 1,894 (514) | 2,106 (292) | 1,440 (208) | 2,374 (745) | 1,675 (91) |

| %GFAP | 50.1 (6.2) | 60.9 (10.4) | 53.5 (13.8) | 58.5 (13.8) | 63.3 (10.3) | 45.1 (14.7) | 54.1 (12.7) | 57.5 (11.1) | 59.1 (8.8) | 54.8 (4.6) |

| %TSP | 3.0 (1.7) | 15.01 (5.0) | 5.1 (3.7) | 18.1 (5.7) | 11.9 (5.1) | 1.0 (1.4) | 5.4 (3.5) | 0.5 (0.5) | 11.8 (4.6) | 4.7 (1.3) |

| %TMEM | 14.2 (9.2) | 31.4 (14.1) | 14.3 (3.6) | 14.3 (3.6) | 36.9 (12.0) | 12.1 (9.1) | 19.7 (12.4) | 13.9 (3.2) | 33.3 (3.0) | 14.2 (3.9) |

| %NPR | 22.9 (13.3) | 27.1 (9.8) | 22.0 (9.1) | 21.0 (9.1) | 33.6 (14.3) | 16.4 (5.9) | 19.7 (3.1) | 15.4 (8.9) | 19.2 (7.2) | 24.4 (1.3) |

| %MBP | 28.8 (17.2) | 39.1 (17.2) | 24.4 (8.8) | 23.1 (10.9) | 32.7 (12.8) | 11.9 (12.0) | 23.1 (9.2) | 8.9 (3.4) | 13.0 (4.9) | 27.6 (3.4) |

| Blood | ||||||||||

| MPs/µL | 651 (39) | 2,550 (521) | 584 (75) | 759 (96.8) | 2,258 (309) | 580 (221) | 772 (311) | 584 (75) | 2,443 (228) | 1,039 (56) |

| %GFAP | 40.1 (11.3) | 48.3 (10.1) | 44.1 (10.6) | 36.3 (5.6) | 45.6 (12.1) | 31.5 (3.8) | 31.5 (3.8) | 37.6 (13.1) | 44.5 (7.1) | 46.2 (5.5) |

| %TSP | 6.1 (5.0) | 22.4 (15.7) | 5.9 (3.1) | 2.5 (1.7) | 21.5 (8.4) | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.8) | 5.1 (3.3) | 13.8 (2.5) | 8.1 (3.6) |

| %TMEM | 15.8 (9.4) | 24.7 (7.9) | 15.4 (4.6) | 22.1 (7.9) | 23.3 (9.8) | 16.7 (6.2) | 16.8 (6.2) | 13.9 (4.6) | 22.2 (6.2) | 22.9 (8.5) |

| %NPR | 21.8 (12.9) | 30.8 (15.0) | 26.1 (8.4) | 24.8 (14.9) | 22.0 (6.8) | 18.3 (9.2) | 18.3 (9.2) | 16.1 (5.4) | 24.7 (5.7) | 19.5 (7.8) |

| %MBP | 26.6 (16.7) | 37.1 (15.3) | 21.2 (9.6) | 16.3 (9.0) | 32.4 (16.1) | 10.4 (7.2) | 16.9 (6.4) | 16.0 (5.5) | 20.3 (8.0) | 26.0 (5.7) |

| %Ly6G | 1.9 (1.8) | 19.4 (9.4) | 0.8 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 15.2 (6.8) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.1) | 11.1 (4.8) | 1.8 (1.9) |

| %Phalloidin | 2.1 (2.0) | 19.6 (7.8) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.7) | 17.3 (9.9) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.2) | 10.1 (2.2) | 6.6 (4.3) |

| %CD41a | 13.5 (9.4) | 12.3 (10.3) | 15.3 (8.9) | 10.1 (5.7) | 8.0 (4.9) | 17.5 (13.1) | 5.6 (4.4) | 14.2 (13.2) | 12.8 (6.0) | 17.7 (9.4) |

| Neutrophils | ||||||||||

| %MPO | 0.9 (0.7) | 6.9 (2.1) | 3.4 (4.7) | 3.4 (4.7) | 3.8 (1.9) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.4) | 3.7 (1.7) | 1.2 (0.7) |

| %CD18 | 2.4 (1.9) | 11.1 (2.5) | 8.8 (5.7) | 8.4 (6.9) | 16.1 (5.3) | 3.3 (1.9) | 0.7 (0.4) | 3.7 (2.2) | 19.7 (5.1) | 2.0 (0.8) |

| Vasc. Leak | ||||||||||

| Brain | 1.0 (0.0) | 3.5 (1.7) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | 2.5 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.1) |

| Skeletal muscle | 1.0 (0.0) | 2.0 (1.7) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) |

Data indicate means ± SD (n = 4–9 mice per lane) and bold numbers are values statistically significantly different from control (P < 0.05 ANOVA). Microparticle (MPs) in deep cervical nodes and blood, neutrophil activation and vascular leak. Flow cytometry was used to evaluate MP production where MPs were identified based on size (0.3 to 1 µm diameter) and surface expression of annexin V. Proteins probed on the surface of the MPs included those from astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP), microglia (transmembrane protein 119, TMEM), oligodendroglia (myelin basic protein, MBP) and neurons (neuronal pentraxin receptor, NPR), neutrophils (Ly6G), platelets (CD41a), and those expressing TSP-1 and F-actin that was assessed by fluorescent labeled phalloidin binding. Columns reflect control mice, those euthanized 2 h postdecompression (deco), neutropenic control mice (LowN), neutropenic mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression (D + LowN), naïve mice injected with 60,000 F-actin-positive MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression (IV F + MPs), neutropenic mice injected with 60,000 F-actin-positive MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression (F + MPs/LowN), naïve mice injected with 60,000 F-actin-negative MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression (IV F-MPs), naïve mice injected with 60,000 F-actin-positive MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression that had first been incubated with antibody to TSP-1 (F + MPs+IgG), naïve mice injected with 60,000 cervical node MPs from mice euthanized 2 h postdecompression (DNodeMPs), and naïve mice injected with 60,000 cervical node MPs from control mice (ContMPs). Table 1, neutrophils, shows the % of neutrophils (identified in the flow cytometer based on Ly6G expression) expressing myeloperoxidase (MPO) and CD18 above a threshold value as an index of cell activation. Table 1, Vasc. leak indicates vascular leakage of 2 × 106 Da rhodamine-labeled dextran assessed for brain and leg skeletal muscle prepared and evaluated as described in methods and materials. Values reflect the fluorescence from rhodamine normalized to values for tissues from control mice.

Effects of MP Injection

Prior work has demonstrated that pathological changes seen with decompression can be recapitulated by injecting naïve mice with F-actin-positive MPs isolated from the blood of decompressed mice, whereas injecting F-actin-negative MPs or MPs from control mice have no effects (13, 14, 25). Injection of the deep cervical node MPs or blood-borne F-actin-expressing MPs from decompressed mice increased glymphatic flow (Fig. 3), node and blood MPs (Table 1, Node and Blood), neutrophil activation (Table 1, Neutrophils), and neuroinflammation assessed by immunohistochemical imaging as well as Western blot (Fig. 4, A and B). These alterations were not observed in neutropenic mice or following injections of MPs from control mice. If F-actin-positive MPs were first incubated with antibody to TSP-1, these changes did not occur (Figs. 3 and 4B, Table 1, Node, Blood, and Neutrophils).

Assessment of Vascular Injury

Vascular integrity in the brain and skeletal muscle of decompressed mice was evaluated by intravenous injections of 2,000 kDa rhodamine-labeled dextran (Table 1, Vasc. Leak). Vascular damage was identified postdecompression and vascular disruption was similar when naïve mice were injected with cervical node MPs or F-actin-expressing blood-borne MPs from decompressed mice, but not when mice were first rendered neutropenic. Notably, neither vascular leak nor elevations of cervical node or blood MPs were found when naïve mice were injected with node MPs from control mice (Table 1, Node, Blood, and Neutrophils).

DISCUSSION

We interpret these results as showing that exposure to high-pressure gas and decompression triggers glial cell activation with an increase of glymphatic flow. The MPs that are generated drain to cervical nodes and then to blood where the TSP-expressing CNS-derived MPs cause neutrophil activation with production of more MPs, some expressing F-actin. Injections into naïve mice of MPs isolated from deep cervical lymph nodes or F-actin-expressing blood MPs from decompressed mice will initiate a brain vascular leak, evidence of neutrophil sequestration (Western blot elevations of neutrophil specific-Ly6G and MPO), and neuroinflammation (based on immunohistochemical changes and Western blot elevations of the p65 subunit of NF-κB and phospho-Ser536 p65 NF-κB), elevation of glymphatic flow, and increases of node and blood MPs. Therefore, we conclude that the TSP-expressing MPs initiate a feed-forward process that causes persistent changes postdecompression that last for at least 4 days.

The neuroinflammatory cycle causes CNS damage reflected by loss of blood-brain barrier integrity and loss of astrocyte AQP4. Neutrophils play a central role as these changes were not found in neutropenic pressure-exposed mice. The data indicate that one pathway for neutrophil activation contributing to neuroinflammation is TSP-expressing MPs, as antibody blocking TSP abrogates the adverse effects of MP injections. TSP-1 receptors on neutrophils include Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4), CD47, and integrins (36, 44). In addition, F-actin-positive MPs in blood that appear from prior publications to be predominantly derived from neutrophils are an alternative cause of the ongoing neutrophil activation (25). Note that cervical node MPs exhibit scant surface F-actin. Recent work has shown that the rigidity caused by the MPs F-actin shell allows the phosphatidylserine on the MPs membrane to be recognized by a complex of neutrophil receptors including CD36, TLR4, and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (45). Finally, it is also possible that some MPs generated by neutrophils are directly due to oxidative stress from high air pressure exposure, a third pathway for cell activation (40).

High gas pressure and decompression pose a dual insult. Studies with human volunteers have demonstrated that elevations in MPs number and F-actin expression occur while under pressure and before decompression (5, 25). However, some MPs contain a gas phase and expand with inert gas uptake on decompression (15–17). The enlarged particles will also cause vascular damage and loss of blood-brain barrier integrity. Furthermore, as a gas phase is present in some MPs in the blood of control animals at ambient pressure, MPs expansion may also occur in association with decompression due to altitude. To our knowledge, however, this has not been investigated with regard to altitude DCS. An additional variable arises due to the effects of oxygen. Studies in humans indicate that hypoxia and hyperoxia elicit still more complex MP responses versus other respired gases, and hyperbaric oxygen can influence MP production in response to decompression (24, 46).

CD36, which based on Western blot data is increased in response to gas pressure/decompression and to MP injections, could play several roles in the neuroinflammatory cycle. CD36 is a class B pattern recognition receptor expressed in many tissues and found in microvascular endothelium, macrophages, B lymphocytes, and platelets (44, 47, 48). In healthy brain, CD36 is found predominantly on endothelial cells and shown to increase in astrocytes and microglia over a span of hours (49, 50). As phosphatidylserine is a CD36 ligand that is heavily expressed on MP membrane, this receptor could exacerbate MP sequestration. CD36 is also expressed in neutrophils where it plays a role in fatty acid trafficking and, as mentioned above, is involved with binding MPs (45). Therefore, further work is needed to elucidate the role of CD36 between endothelium and neutrophil activation.

Human divers exhibit similar elevations of blood-borne MPs and neutrophil activation as are seen in decompressed mice (4–14). The numbers of blood-borne MPs are higher in those with DCS and persist for longer than in asymptomatic, healthy divers (51). Work is underway to evaluate whether MPs bearing CNS-specific proteins are elevated in human divers. Because data in this study show that intra-CNS events can be initiated by systemic injection of MPs, the primary event leading to the feed-forward cycle could occur either in the brain or in the systemic circulation. Hence, further work is needed to evaluate whether MPs contribute to CNS DCS, where complaints include confusion, lethargy, impaired concentration, visual, vestibular, and auditory disturbances, as well as peripheral motor and sensory changes. The basis for global CNS manifestations remains unclear, whereas development of hemisensory deficits and hemiplegia are thought to occur due to gas embolism (1). A recent population-based study demonstrated that those sustaining DCS have a 5.7-fold increased risk of developing a long-term sleep disorder (52). This could be related to a glymphatic function disturbance. Glymphatic function is normally most active while sleeping, and function is perturbed by lack of sleep (53). The reverse is also true: impaired glymphatic function perturbs sleep (54–57).

Finally, the cyclic process we describe with high pressure/decompression may be a common feature with brain injuries. MPs and other extracellular vesicles generated systemically can exacerbate traumatic and other causes of brain injury and reciprocally, CNS-derived MPs cause peripheral vascular disorders once liberated to the bloodstream (17, 58, 59). Further work is needed to examine the role of extracellular vessels in CNS pathophysiology.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the US Office of Naval Research N00014-20-1–2641 and N00014-22-1–2818 (to S. R. Thom), the National Institutes for Health (NINDS) R01-NS122855 (to S. R. Thom), and from the University of Maryland Baltimore, Institute for Clinical & Translational Research (ICTR).

DISCLAIMERS

The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.R.T. conceived and designed research; S.R.T., V.M.B., A.R.B., A.K.A., D.R., G.Q., X.L., S.T., and S.X. performed experiments; S.R.T. and S.X. analyzed data; S.R.T. interpreted results of experiments; S.R.T. prepared figures; S.R.T. drafted manuscript; S.R.T., V.M.B., A.R.B., A.K.A., D.R., G.Q., S.T., and S.X. edited and revised manuscript; S.R.T., V.M.B., A.R.B., A.K.A., D.R., G.Q., S.T., and S.X. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Francis TJ, Pearson RR, Robertson AG, Hodgson M, Dutka AJ, Et F. Central nervous system decompression sickness: latency of 1070 human cases. Undersea Biomed Res 15: 403–417, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bigley NJ, Perymon H, Bowman GC, Hull BE, Stills HF, Henderson RA. Inflammatory cytokines and cell adhesion molecules in a rat model of decompression sickness. J Interferon Cytokine Res 28: 55–63, 2008. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin JD, Thom SR. Vascular leukocyte sequestration in decompression sickness and prophylactic hyperbaric oxygen therapy in rats. Aviat Space Environ Med 73: 565–569, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barak OF, Janjic N, Drvis I, Mijacika T, Mudnic I, Coombs GB, Thom SR, Madic D, Dujic Z. Vascular dysfunction following breath-hold diving. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 98: 124–130, 2020. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2019-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brett KD, Nugent NZ, Fraser NK, Bhopale VM, Yang M, Thom SR. Microparticle and interleukin-1β production with human simulated compressed air diving. Sci Rep 9: 13320, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vince RV, McNaughton LR, Taylor L, Midgley AW, Laden G, Madden LA. Release of VCAM-1 associated endothelial microparticles following simulated SCUBA dives. Eur J Appl Physiol 105: 507–513, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0927-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Madden LA, Chrismas BC, Mellor D, Vince RV, Midgley AW, McNaughton LR, Atkin SL, Laden G. Endothelial function and stress response after simulated dives to 18 msw breathing air or oxygen. Aviat Space Environ Med 81: 41–45, 2010. doi: 10.3357/asem.2610.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thom SR, Milovanova TN, Bogush M, Bhopale VM, Yang M, Bushmann K, Pollock NW, Ljubkovic M, Denoble P, Dujic Z. Microparticle production, neutrophil activation and intravascular bubbles following open-water SCUBA diving. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 1268–1278, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01305.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thom SR, Milovanova TN, Bogush M, Yang M, Bhopale VM, Pollock NW, Ljubkovic M, Denoble P, Madden D, Lozo M, Dujic Z. Bubbles, microparticles and neutrophil activation: Changes with exercise level and breathing gas during open-water SCUBA diving. J Appl Physiol (1985) 114: 1396–1405, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00106.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pontier J-M, Gempp E, Ignatescu M. Blood platelet-derived microparticles release and bubble formation after an open-sea dive. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37: 888–892, 2012. doi: 10.1139/h2012-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Madden D, Thom SR, Milovanova TN, Yang M, Bhopale VM, Ljubkovic M, Dujic Z. Exercise before SCUBA diving ameliorates decompression-induced neutrophil activation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46: 1928–1935, 2014. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Madden D, Thom SR, Yang M, Bhopale VM, Milovanova TN, Ljubkovic M, Dujic Z. High intensity cycling before SCUBA diving reduces post-decompression microparticle production and neutrophil activation. Eur J Appl Physiol 114: 1955–1961, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00421-014-2925-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thom SR, Yang M, Bhopale VM, Huang S, Milovanova TN. Microparticles initiate decompression-induced neutrophil activation and subsequent vascular injuries. J Appl Physiol (1985) 110: 340–351, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00811.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Yu K, Yang M. Provocative decompression causes diffuse vascular injury in mice mediated by microparticles containing interleukin-1β. J Appl Physiol (1985) 125: 1339–1348, 2018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00620.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thom SR, Yang M, Bhopale VM, Milovanova TN, Bogush M, Buerk DG. Intra-microparticle nitrogen dioxide is a bubble nucleation site leading to decompression-induced neutrophil activation and vascular injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 114: 550–558, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01386.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang M, Milovanova TN, Bogush M, Uzan G, Bhopale VM, Thom SR. Microparticle enlargement and altered surface proteins after air decompression are associated with inflammatory vascular injuries. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 204–211, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00953.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang M, Kosterin P, Salzberg BM, Milovanova TN, Bhopale VM, Thom SR. Microparticles generated by decompression stress cause central nervous system injury manifested as neurohypophiseal terminal action potential broadening. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 1481–1486, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00745.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lemaitre F, Fahlman A, Gardette B, Kohshi K. Decompression sickness in breath-hold divers: a review. J Sports Sci 27: 1519–1534, 2009. doi: 10.1080/02640410903121351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cross ER. Taravana diving syndrome in the tuamotu diver. In: Physiology of Breath‐Hold Diving and the AMA of Japan: Papers, edited by Rahn E, Yokoyama T. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 1965, p. 205–219. Vol. 1341. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schipke JD, Gams E, Kallweit O. Decompression sickness following breath-hold diving. Res Sports Med 14: 163–178, 2006. doi: 10.1080/15438620600854710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lemaître F, Kohshi K, Tamaki H, Nakayasu K, Harada M, Okayama M, Satou Y, Hoshiko M, Ishitake T, Costalat G, Gardette B. Doppler detection in Ama divers of Japan. Wilderness Environ Med 25: 258–262, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Yang M. Neutrophils generate microparticles during exposure to inert gases due to cytoskeletal oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 289: 18831–18845, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m113.543702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Yu K, Huang W, Kane MA, Margolis DJ. Neutrophil microparticle production and inflammasome activation by hyperglycemia due to cytoskeletal instability. J Biol Chem 292: 18312–18324, 2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m117.802629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Yang M. Microparticle-induced vascular injury in mice following decompression is inhibited by hyperbaric oxygen: effects on microparticles and interleukin-1β. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 1006–1014, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01109.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhopale VM, Ruhela D, Brett KD, Nugent NZ, Fraser NK, Levinson SL, DiNubile MJ, Thom SR. Plasma gelsolin modulates the production and fate of IL-1β-containing microparticles following high-pressure exposure and decompression. J Appl Physiol (1985) 130: 1604–1613, 2021. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01062.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Plog BA, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system in central nervous systemc health and disease: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 13: 379–394, 2018. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-051217-111018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, Benveniste H, Vates GE, Deane R, Goldman SA, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 4: 147ra111, 2012. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, Feng T, Logan J, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest 123: 1299–1309, 2013. doi: 10.1172/JCI67677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ringstad G, Vatnehol SAS, Eide PK. Glymphatic MRI in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Brain 140: 2691–2705, 2017. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Leon MJ, Li Y, Okamura N, Tsui WH, Saint-Louis LA, Glodzik L, Osorio RS, Fortea J, Butler T, Pirraglia E, Fossati S, Kim H-J, Carare RO, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H, Rusinek H. Cerebrospinal fluid clearance in Alzheimer disease measured with dynamic PET. J Nucl Med 58: 1471–1476, 2017. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.187211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Absinta M, Ha S-K, Nair G, Sati P, Luciano NJ, Palisoc M, Louveau A, Zaghloul KA, Pittaluga S, Kipnis J, Reich DS. Human and nonhuman primate meninges harbor lymphatic vessels that can be visualized noninvasively by MRI. eLife 6: e29738, 2017. doi: 10.7554/elife.29738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aspelund A, Antila S, Proulx ST, Karlsen TV, Karaman S, Detmar M, Wiig H, Alitalo K. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med 212: 991–999, 2015. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, Derecki NC, Castle D, Mandell JW, Lee KS, Harris TH, Kipnis J. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523: 337–341, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nature14432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morgensen FL-H, Delle C, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system (en)during inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 22: 7491, 2021. doi: 10.3390/ijms22147491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Verkhratsky A, Matteoli M, Parpura V, Mothet JP, Zorec R. Astrocytes as secretory cells of the central nervous system: idiosyncrasies of vesicular secretion. EMBO J 35: 239–257, 2016. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Majluf-Cruz A, Manns JM, Uknis AB, TYang X, Comlman RW, Harris RB, Frazier W, Lawler J, DeLa Cadena RA. Residues F16-G33 and A784-N823 within platelet thrombospondin-1 play a major role in binding human neutrophils: evaluation by two novel binding assays. J Lab Clin Med 136: 292–302, 2000. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.109407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martin-Manso G, Galli S, Ridnour LA, Tsokos M, Wink DA, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin 1 promotes tumor macrophage recruitment and enhances tumor cell cytotoxicity of differentiated U937 cells. Cancer Res 68: 7090–7099, 2000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-08-0643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ruhela D, Bhopale VM, Yang M, Yu K, Weintraub E, Greenblatt A, Thom SR. Blood-borne and brain-derived microparticles in morphine-induced anti-nociceptive tolerance. Brain Behav Immun 87: 465–472, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bhullar J, Bhopale VM, Yang M, Sethuraman K, Thom SR. Microparticle formation by platelets exposed to high gas pressures – an oxidative stress response. Fr Radic Biol Med 101: 154–162, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang C, Lin J, Wei F, Song J, Chen W, Shan L, Xue R, Wang G, Tao J, Zhang G, Xu GY, Wang L. Characterizing the glymphatic influx by utilizing intracisternal infusion of fluorescently conjugated cadaverine. Life Sci 201: 150–160, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taoka T, Jost G, Frenzel T, Naganawa S, Pietsch H. Impact of the glymphatic system on the kinetic and distribution of gadodiamide in the rat brain: observations by dynamic MRI and effect of circadian rhythm on tissue gadolinium concentrations. Invest Radiol 53: 529–534, 2018. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beaulieu E, Demeule M, Ghitescu L, Beliveau R. P-glycoprotein is strongly expressed in the luminal membranes of the endothelium of blood vessels in the brain. Biochem J 326: 539–544, 1997. doi: 10.1042/bj3260539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ruhela D, Bhopale VM, Kalakonda S, Thom SR. Astrocyte-derived microparticles initiate a neuroinflammatory cycle due to carbon monoxide poisoning. Brain Behav Immun Health 18: 100398, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Greenwalt DE, Lipsky RH, Ockenhouse CF, Ikeda H, Tandon NN, Jamieson GA. Membrane glycoprotein CD36: a review of its roles in adherence, signal transduction, and transfusion medicine. Blood 80: 1105–1115, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Arya AK, Ruhela D, Bhat AR, Mitra N, Hoffstad O, Malay DS, Mirza ZK, Landis JC, Lev-Tov HA, Kirsner RS, Hsia R, Levinson SL, DiNubile MJ, Margolis DJ. Blood-borne microparticles are an inflammatory stimulus in type-2 diabetes mellitus. Immunohorizons 7: 71–80, 2023. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.2200099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Balestra C, Arya AK, Leveque C, Virgili F, Germonpre P, Lambrechts K, Lafere P, Thom SR. Varying oxygen partial pressure elicits blood-borne microparticles expressing different cell-specific proteins—toward a targeted use of oxygen? Int J Mol Sci 23: 7888, 2022. doi: 10.3390/ijms23147888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Silverstein RL, Febbraio M. CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci Signal 2: re3, 2009. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.272re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Won W-J, Bachmann MF, Kearney JF. CD36 is differentially expressed on B cell subsets during development and in responses to antigen. J Immunol 180: 230–237, 2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Febbraio M, Silverstein RL. CD36: implications in cardiovascular disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 39: 2012–2030, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cho S, Park EM, Febbraio M, Anrather J, Park L, Racchumi G, Silverstein RL, Iadecola C. The class B scavenger receptor CD36 mediates free radical production and tissue injury in cerebral ischemia. J Neurochem 25: 2504–2512, 2005. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0035-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thom SR, Bennett M, Banham ND, Chin W, Blake DF, Rosen A, Pollock NW, Madden D, Barak O, Marroni A, Balestra C, Germonpre P, Pieri M, Cialoni D, Le PN, Logue C, Lambert D, Hardy KR, Sward D, Yang M, Bhopale VB, Dujic Z. Association of microparticles and neutrophil activation with decompression sickness. J Appl Physiol (1985) 119: 427–434, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00380.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tseng W-S, Chien W-C, Chung C-H, Chou Y-C, Tzeng N-S. Risk of sleep disorders in patients with decompression sickness: a nationwide, population-based study in Taiwan. Psychiatra Danubina 31: 172–181, 2019. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2019.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sullan MJ, Asken BM, Jaffee MS, DeKisky ST, Bauer RM. Glymphatic system disruption as a mediator of brain trauma and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 84: 316–324, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, O’Donnell J, Christensen DJ, Nicholson C, Iliff JJ, Takano T, Deane R, Nedergaard M. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 342: 373–377, 2013. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kanbayashi T, Shimohata T, Nakashima I, Yaguchi H, Yabe I, Nishizawa M, Shimizu T, Nishino S. Symptomatic narcolepsy in patients with neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis: new neurochemical and immunological implications. Arch Neurol 66: 1563–1566, 2009. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rainey-Smith SR, Mazzucchelli GN, Villemagne VL, Brown BM, Porter T, Weinborn M, Bucks RS, Milicic L, Sohrabi HR, Taddei K, Ames D, Maruff P, Masters CL, Rowe CC, Salvado O, Martins RN, Laws SM; AIBL Research Group. Genetic variation in Aquaporin-4 moderates the relationship between sleep and brain Aβ-amyloid burden. Transl Psychiatry 8: 47, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Larson SMU, Landolt H-P, Berger W, Nedergaard M, Knudsen GM, Hoist SC. Haplotype of the astrocytic water channel AQP4 is associated with slow wave energy regulation in human NREM sleep. PLoS Biol 18: e3000623, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kumar A, Stoica BA, Loane DJ, Yang M, Abulwerdi G, Khan N, Kumar A, Thom SR, Faden AI. Microglial-derived microparticles mediate neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 14: 47, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0819-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhao Z, Zhou Y, Tian Y, Li M, Dong J-F, Zhang J. Cellular microparticles and pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Protein Cell 8: 801–810, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0414-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.