Abstract

Objective:

Caregivers are critical in advanced care planning (ACP) discussions, which are difficult but necessary to carry out patients’ goals of care. We developed and evaluated feasibility and acceptability of a communication training to equip caregivers of patients with malignant brain tumors with skills to navigate ACP conversations.

Method:

Caregivers completed a two-hour virtual training addressing ACP Discussions with Your Loved One and ACP Discussions with the Medical Team. A pre-training assessment was completed at baseline and a training evaluation was completed one day post-training. A subset of participants completed semi-structured interviews two months post-training.

Results:

Of 15 caregivers recruited, nine attended the training and four completed qualitative interviews. Post-training, 40% felt confident in discussing ACP with loved ones and 67% felt confident doing so with healthcare professionals; 100% reported feeling confident in using skills learned in the training to facilitate these conversations. Data from qualitative interviews highlighted additional benefits of the training in empathic communication skills and fostering social support.

Significance of Results:

Our communication skills training shows promise in supporting caregivers’ skills and confidence in engaging in ACP discussions with patients and healthcare providers. A future randomized controlled trial with a larger and more diverse caregiving sample is needed to determine training efficacy.

Keywords: communication skills, communication training, caregivers, cancer caregivers, advanced care planning

Introduction

The 6 million Americans who care for family or friends with cancer are an essential component of the healthcare system (Kent et al., 2019). Caregivers support patients in all aspects of care and play a key role in advanced care planning (ACP) discussions. Such discussions impact critical outcomes, including prognostic awareness, psychopathology, timely hospice referrals, and the use of aggressive treatments near death (Detering et al., 2010; Nilsson et al., 2009; Temel, 2010; Wright et al., 2010). Despite benefits, 52–79% of patients have no ACP documented before death (Connors et al., 1995; Heyland et al., 2013). Discussing ACP is difficult and made more difficult by distress (Kaplowitz et al., 2002; Marwit et al., 2002; Siminoff et al., 2008). Families often expect healthcare providers (HCPs) to initiate conversations; however, HCPs frequently avoid discussing ACP (Levin et al., 2010) or delay it until it is too late (Heyland et al., 2013; You et al., 2014).

Caregivers are uniquely positioned to broker patient-HCP communication, as they often have more accurate prognostic awareness than patients (Diamond et al., 2017) and manage a range of demanding responsibilities in decision-making, treatment, and care (AARP National Alliance for Caregiving., 2016). Assisting caregivers with communication and providing them with training to engage confidently in ACP discussions is likely more effective than HCP training alone. Interventions that address communication between patients and caregivers exist (Applebaum et al., 2013; Northouse et al., 2010), but have primarily focused on enhancing social support (Baucom et al., 2009; Bernacki et al., 2015; Budin et al., 2008; Campbell et al., 2007; Given et al., 2006; Lyon et al., 2014; Northouse et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2004). To the research team’s knowledge, no interventions have been studied to date addressing communication between caregivers and patients’ HCP.

Caregivers of patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and other malignant gliomas represent a group in urgent need of communication skills. These highly aggressive, devastating neurologic diseases are characterized by headaches, seizures, and deterioration of physical and cognitive function. Even with initial optimal treatment including radiation, surgery, and/or chemotherapy to reduce tumor burden, nearly all malignant gliomas recur (Wen et al., 2008). Personality changes, mood disturbances, and cognitive limitations are unavoidable and make the provision of care particularly challenging (Catt et al., 2008; Salander, 1996), requiring that caregivers quickly take over responsibility for healthcare communication. As such, optimal outcomes for patients may depend on caregivers’ ability to initiate difficult, yet necessary, ACP discussions.

To date, no intervention has specifically provided caregivers with training to improve their skills and confidence as collaborators with both patients and HCPs and, later, as healthcare proxies. The objective of this study was to develop and pilot test a brief communication training to equip caregivers of patients with malignant gliomas with the skills necessary to initiate and successfully navigate challenging ACP conversations.

Method

Development of Training

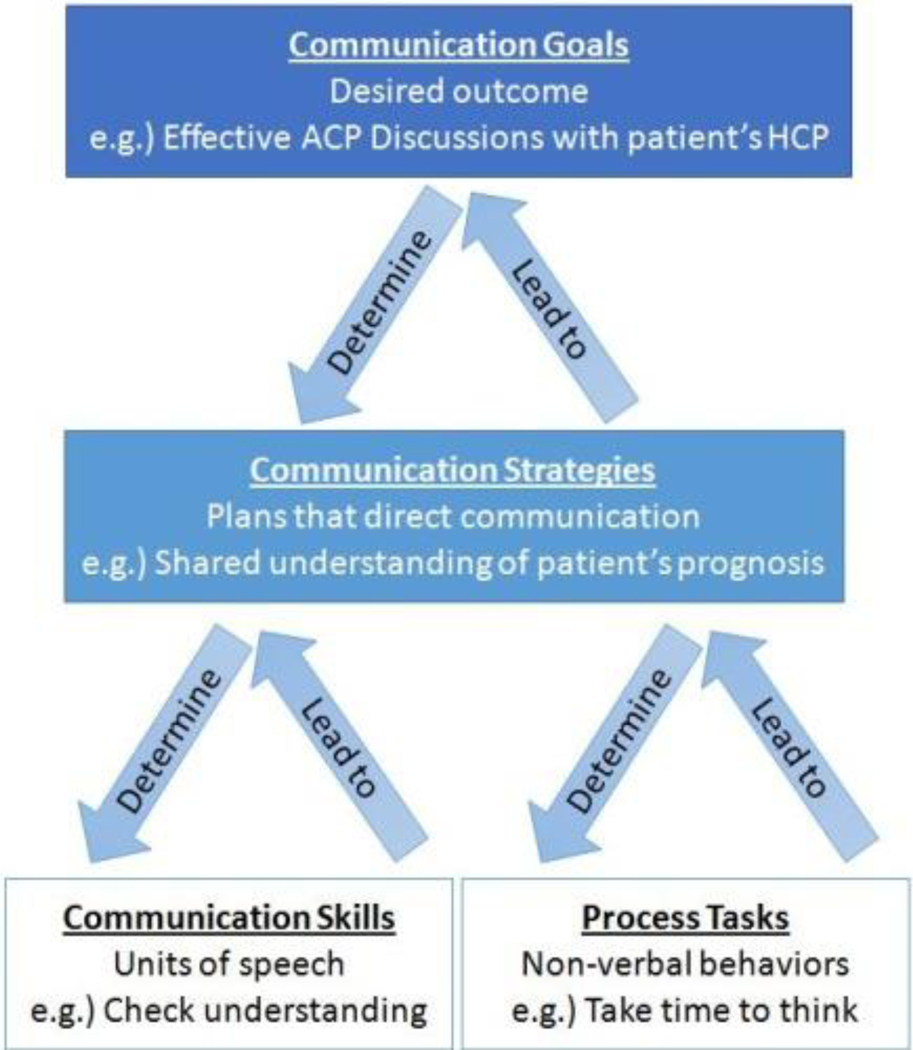

A team of psychologists and neuro-oncologists collaborated with the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) Communication Skills Training and Research Program (Comskil) to create training materials for two modules to address communication challenges identified through literature review and clinical experience of the team. The modules were established through six steps (Brown et al., 2010) outlined in Table 1 and designed after the core communication components in the Comskil Conceptual Model (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Processes used to establish caregiver-specific communication modules

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Conducted literature review to identify communication challenges |

| Step 2 | Held consensus review meetings to form core module components with a team spanning communication training experts, psychologists specializing in caregiver research and clinical care, and neuro-oncology HCPs. Solicited feedback from Patient and Family Advisory Committee (PFAC) to ensure topics of interest and communication needs were covered in a way that is sensitive to caregivers’ experiences. |

| Step 3 | Created modular blueprints of core communication components as outlined in Comskil Conceptual Model, which posits four key interaction components:

These goals, strategies, skills, and process tasks guided all proceeding module development. |

| Step 4 | Produced training materials developed collaboratively by PIs including:

|

| Step 5 | Created experiential role-play scenarios (e.g., “talking to HCPs about becoming a healthcare proxy”) and then tailored them to individual caregivers’ perceived challenges (e.g., “I’m afraid my wife will break down if I bring this up”) while providing a specific example to practice newly learned skills |

| Step 6 | Conducted open trial with 15 caregivers to complete formal evaluations, and make iterative revisions to the training in preparation for an RCT. |

Note: HCPs, healthcare professionals; ACP, advanced care planning; RCT, randomized controlled trial

Figure 1.

Core communication components in the Comskil Conceptual Model

Participants

Participants were recruited through physician referral from the MSK Brain Tumor Center and were self-reported current caregivers to a patient with a malignant glioma, fluent in English and age ≥18.

Procedures and Measures

Eligible and interested caregivers provided informed consent. Participants completed a demographic and pre-training questionnaire at baseline and a training evaluation one day post-training. All participants were asked if they would be willing to complete an optional 45-minute interview two months post-training via Webex.

Demographic information (Lichtenthal et al., 2015).

Demographic data including gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, relationship to patient, and caregiving duration were assessed.

Comskil Pre-Training Evaluation (Brown et al., 2010; Lubrano et al., 2010).

Following standard Comskil practice, an anonymous survey was sent electronically one week pre-training which asked two questions about confidence in discussing ACP with loved ones and HCPs. Questions were rated on a five-point Likert scale, anchored at (1) ‘strongly disagree’ and (5) ‘strongly agree.’

Comskil Module Post-Training Evaluation (Brown et al., 2010; Lubrano et al., 2010).

This anonymous form evaluated participants’ perceptions of training modules and was sent electronically one day post-training. The questions were rated on a five-point Likert scale anchored at (1) ‘strongly disagree’ and (5) ‘strongly agree.’

Qualitative Interview.

A 45-minute semi-structured interview guide evaluated participants’ reactions to the training, including the impact of training on engagement in ACP discussions, confidence in engaging in discussions, and areas of refinement.

Intervention

Originally designed to be delivered in-person prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Communication Training took place virtually via Zoom and included two modules: 1) ACP Discussions with your Loved One and 2) ACP Discussions with the Medical Team. Training included a 15-minute lecture and 90 minutes of role-play exercises where caregivers practiced skills with actors trained to portray patients and HCPs. Realistic scenarios were created and tailored to caregivers’ reported concerns, which is standard practice in Comskil (Bylund et al., 2011; Kissane et al., 2012; Pehrson et al., 2016). For example, caregivers specified unique challenges, such as “My husband gets really angry when I try to bring this up,” and actors were coached to portray the angry husband. After role-plays, caregivers set a SMART (Doran, 1981) (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-bound) goal related to ACP conversations to motivate and direct behavior change (Locke et al., 2006). Post-training, caregivers received example documents frequently used in carrying out ACP (e.g., DNR/DNI and healthcare proxy forms) to facilitate discussions. Two weeks post-training, study staff called caregivers to evaluate progress toward SMART goals and review skills as needed.

Analytic Plan

Sample characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. A priori feasibility benchmarks were the ability to recruit 15 caregivers within 12 months and a training completion rate of 10 out of 15 caregivers. Measurement of acceptability was guided by the Kirkpatrick Model, which proposes four assessment levels for evaluating the impact of trainings (Kirkpatrick, 1967). Acceptability (Level 1) was assessed via satisfaction on the Comskil Module Evaluation Form. Results were analyzed descriptively and mean item scores ≥4 were deemed acceptable.

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using thematic content analysis. Transcripts were reviewed independently by the coding team (R.G., M.B., M.L.) to identify key feedback, reach consensus on conceptual findings and identify recurrent themes, which were then refined in a consensus meeting with the PI (A.A.).

Results

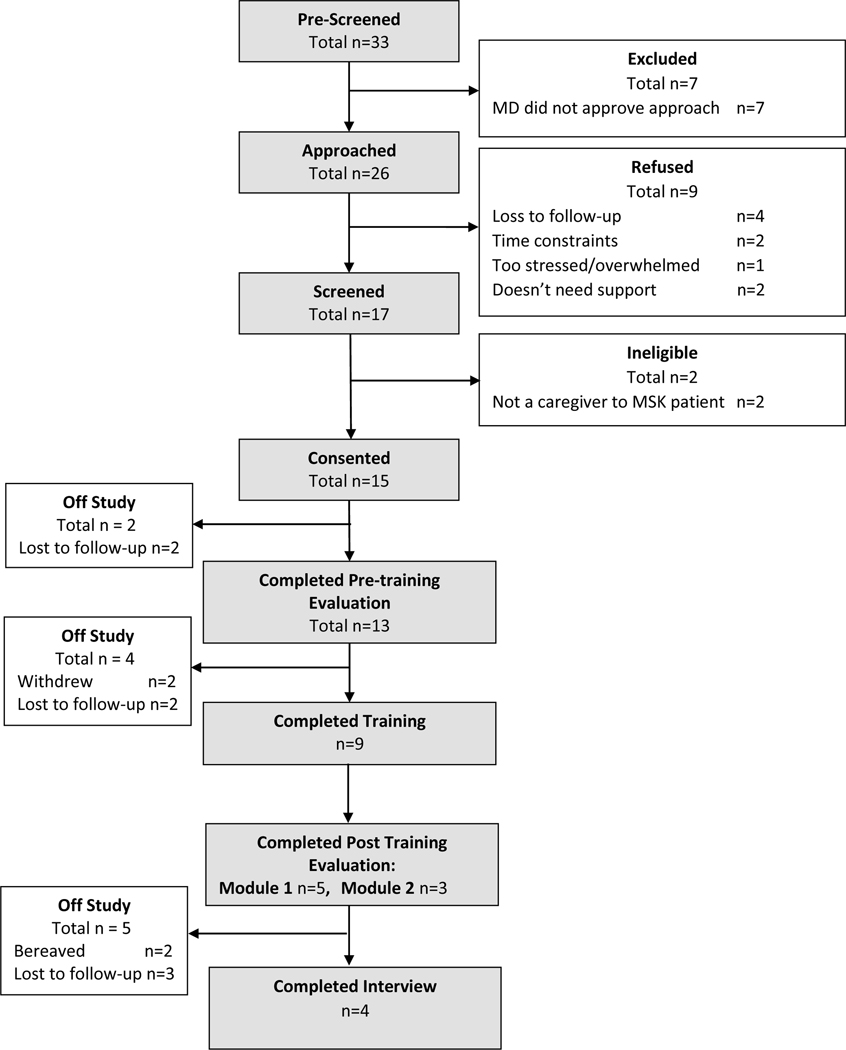

Over 12 months, 15 caregivers enrolled, 9 of whom participated in one of five trainings; 4 completed the qualitative interview (Figure 2). Of these, 8 submitted SMART goals (Table 2). Participant demographic and medical characteristics are presented in Table 3. Pre-training, 62% reported “mixed feelings” regarding confidence in discussing ACP with their loved ones (n=8, M=2.92), and 77% (n=10, M=4.0) reported confidence in discussing ACP with HCPs. Post-training, 5 participants completed the anonymous survey evaluating Module 1 (ACP Discussions with Your Loved One), and 3 for Module 2 (ACP Discussions with the Medical Team) (Table 4). Most felt confident that they would use skills learned with their loved one and HCPs and indicated these skills would help their loved one receive optimal care. Most agreed that the timing of the training was appropriate and two shared additional feedback (i.e., one suggested setting SMART goals before concluding the training day as opposed to after, and one requested resources to help prepare for future caregiving responsibilities).

Figure 2.

Consort diagram

Table 2.

Participant Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-bound (SMART) goals

| Study ID | SMART Goal |

|---|---|

| 1003 | “My SMART goal was to talk to [the patient] about planning for the future. Including a will and his wishes.” |

| 1004 | “I will discuss with [the patient] the importance of having his wishes concerning his medical treatment documented. I will assist him in completing forms such as a DNR, Living Will, NYS MOLST and/or Power of Attorney forms as applicable per his wishes. I will also review with [the patient] his current Health Care Proxy to confirm that he doesn’t want to make any changes.” |

| 1006 | “Have a conversation about the ‘what if’s’; just have a conversation acknowledging the need to have that conversation.” |

| 1007 | “Get legal paperwork in order (along with tax matters) regarding legal & finance aspects of life, plan summer with [the patient], have more in depth talk about when [the patient] is not in capacity and what his wishes are. Go to therapy!” |

| 1008 | “Funeral planning” |

| 1011 | “Make a folder of the example documents provided by the hospital, and other resources I’ve gathered regarding ‘getting affairs in order’ and leave on my desk in their home, along with a letter explaining my passion for supporting them through this process, and list ways I can support them...” |

| 1013 | “Start talking about advanced care planning. Find out my husband’s wishes and what he wants for his care.” |

| 1014 | “Start having smaller conversations to make my husband feel comfortable talking about these things. Asking him questions ‘have you thought about this?’ ‘How do you feel about this?’ to prepare him in advance of their next appointment and making me his healthcare proxy.” |

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants who completed trainings

| Characteristic | N = 9 |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 9 (100%) |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 48.4 (12.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 49 (43, 52) |

| Race and ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (22%) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 7 (78%) |

| Relationship status, n (%) | |

| Single | 1 (11%) |

| Married | 7 (78%) |

| Living in a married-like relationship | 1 (11%) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Vocational school or some college | 1 (11%) |

| College degree | 5 (56%) |

| Professional or graduate School | 3 (33%) |

| Income, n (%) | |

| $5,000 to $9,999 | 1 (11%) |

| $40,000 to $74,999 | 1 (11%) |

| $75,000 or more | 7 (78%) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Paid full-time employment | 5 (56%) |

| Paid part-time employment | 1 (11%) |

| Self-employed | 1 (11%) |

| On leave with pay | 1 (11%) |

| Homemaker | 1 (11%) |

| Patient’s cancer type, n (%) | |

| Glioblastoma Multiforme | 7 (78%) |

| Anaplastic Astrocytoma | 1 (11%) |

| Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma | 1 (11%) |

| Months spent providing care | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.56 (4.48) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (6, 11) |

| Hours/day spent providing care | |

| Mean (SD) | 8.33 (8.36) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3.3, 9.5) |

| Relationship to the patient, n (%) | |

| Spouse/Partner | 7 (78%) |

| Child | 2 (22%) |

| Caregiver/patient cohabitation, n (%) | |

| Yes, all of the time | 7 (78%) |

| Yes, since his/her initial diagnosis | 1 (11%) |

| No | 1 (11%) |

Note: SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range

Table 4.

Module 1 (ACP Discussions with your Loved One) and Module 2 (ACP Discussions with the Medical Team) evaluation responses

| Module 1 (ACP Discussions with your Loved One) N = 5 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item | N (%) Agreed or Strongly Agreed | Mean |

| Now that I have attended this workshop, I feel confident discussing ACP with my loved one. | 2 (40%) | 3.6 |

| I feel confident that I will use the skills I learned today with my loved one. | 5 (100%) | 4.6 |

| The skills I learned today will allow my loved one to receive optimal care. | 4 (80%) | 4.4 |

| The workshop prompted me to critically evaluate my own communication skills with my loved one. | 5 (100%) | 4.5 |

| The small group facilitators were effective. | 5 (100%) | 4.6 |

| Module 2 (ACP Discussions with the Medical Team) N = 3 | ||

| Item | N (%) Agreed or Strongly Agreed | Mean |

| Now that I have attended this workshop, I feel confident discussing ACP with my loved one’s medical team. | 2 (67%) | 4.0 |

| I feel confident that I will use the skills I learned today with my loved one’s medical team. | 3 (100%) | 4.7 |

| The skills I learned today will allow my loved one to receive optimal care. | 3 (100%) | 4.7 |

| The workshop prompted me to critically evaluate my own communication skills with my loved one’s medical team. | 3 (100%) | 4.3 |

| The timing of this training was appropriate. | 2 (67%) | 4.3 |

| I would have preferred to participate in this training earlier on, when my loved one was first diagnosed. | 2 (67%) | 2.3 |

Four caregivers participated in in-depth interviews from which 5 key themes emerged (Table 5): 1) The training increased caregivers’ willingness and confidence to discuss ACP; 2) The structure and components (i.e., didactic presentation, role-play, and follow-up call) of the training were helpful in promoting ACP discussions; 3) The training provided social support; 4) Empathic communication was the most helpful skill learned; and 5) The optimal timing for training depends on patients’ illness trajectories.

Table 5.

Key themes from qualitative interviews. (n=4)

| Theme | Representative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Training increased caregivers’ willingness and confidence to discuss ACP |

“This reinforced the importance of communication… But I felt that the study, the program, was helpful in giving me an opening, like how to bring it up.” (P1008)

“I feel that I maybe have some tools, like I learned a little bit about advanced care planning and just kind of watching the videos, it normalized it for me, like oh yeah I’m not doing the wrong thing by just trying to talk about it. It’s very much a part of our lives right now. And so, I think just the permission and the encouragement that it is important was really helpful.” (P1011) “I would say that feeling more confident in communication has made me less stressed.” (P1008) |

| Structure of the training was helpful in motivating caregivers to engage in ACP discussions with their loved ones |

“When I sat down with [the patient] to speak to him it kind of helped me ask the questions, like because I had already done it with the actor. So it kind of, I was able to sit with [the patient] and ask him the same questions and talk to him about what we needed to discuss and regarding being taking care of, taking care of him, what does he want.” (P1013)

“It sort of encouraged me to talk about things that I didn’t want to talk about. So that was very helpful. It was after that call that I talked to him about, we started talking about end-of-life care, and stuff like that. I brought that up. So that was helpful.” (P1008) |

| The training provided social support for caregivers |

“I found purpose because there was somebody else in the training, and I felt like my vulnerability could impact her… I found great purpose in sharing space with another woman that was going through the same thing I was.” (P1011)

“It was interesting to get the perspective of another person who is going through this.” (P1008) |

| Empathic communication was the most helpful skill learned |

“Validating his feelings, that’s something I’ve been really trying to work on.” (P1003)

“What I’ve been trying to do is say things like ‘I know this is disgusting to talk about, I know this is really hard.’ Trying to acknowledge his feelings, not just be all in my own head. And that’s something that we talked a lot about in the communication study, and that’s been helpful for both of us. I am trying to see things more from his perspective.” (P1008) |

| The optimal timing for training depends on patients’ illness trajectory |

“Well I think it depends on because I had my own caregiving journey, if he had been sicker, I would have needed it earlier.” (P1008)

“Because the diagnosis is the diagnosis, right? And the clock is ticking. It’s not very beneficial to have access to support months later, and not have any sort of support from the beginning.” (P1011) |

Note: ACP, Advanced Care Planning

Discussion

We developed a communication training for caregivers to promote ACP discussions and evaluated its feasibility and acceptability. Despite occurring during the initial year of the Covid-19 pandemic, recruitment was feasible as 15 caregivers of 33 screened enrolled in one year, consistent with previous studies (Diamond et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018) and the investigative team’s recruitment goals. Nine caregivers attended the training, a completion rate (60%) that is slightly lower than our target of 67%, though likely a reflection of the well-documented challenges caregivers face in utilizing psychosocial support in addition to the unique challenges imposed by the pandemic.

The adoption of communication skills helped caregivers feel more willing to open ACP discussions, a shift that was underscored by participants’ SMART goals (Table 2). It is unsurprising that not all participants reported overall confidence in engaging in ACP discussions with patients post-training; such discussions are emotionally difficult and, in most cases, must be repeated throughout the illness journey. In terms of the impact of training on communication with HCPs, caregivers reported confidence in engaging in such discussions and making use of the specific skills taught.

There was mixed feedback regarding timing of the training. On average, training occurred 8 months into participants’ caregiving journeys, long after patients’ initial diagnoses. It is likely that earlier delivery of the training could help caregivers navigate treatment planning in advance of being required to assume responsibility for healthcare communication. This desire to provide communication skills earlier, however, must be balanced with sensitivity to the emotional devastation of newly diagnosed families. As malignant gliomas can be aggressive, with most patients dying within 9 months of recurrence (Wen et al., 2008), caregivers may benefit from receiving the training closer to the patient’s initial diagnosis, though only after they have had time to adjust to such life-altering news.

In-depth interviews highlighted a particular benefit of training in empathic communication skills, which caregivers felt would be particularly helpful in navigating discussions with loved ones. Role-play scenarios provided the opportunity to practice these skills and verbalize specific empathic statements in advance of doing so with loved ones. Additionally, caregivers shared that participation helped them feel less isolated. While not an explicit goal of the training, the program brought caregivers together and created a sense of community among participants. This added value can be fostered in future trainings with larger groups of caregivers and follow-up sessions with continued opportunity for connection. While engaging caregivers for in-person appointments is often challenging, telemedicine removes many barriers to care (e.g., transportation, coverage for patient’s care) and makes the possibility of larger groups more feasible.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study had several limitations. The small and sociodemographically-limited sample of predominantly White, non-Hispanic, and high socioeconomic status participants limits generalizability of findings. Our data are also limited by the relatively low completion rate of post-training evaluations, which may reflect the heavy burden of caregiving for a patient with a malignant glioma. Additionally, anonymous evaluations precluded the ability to perform pre-post data analyses or associations with participant characteristics; however, it also supports validity of evaluations by reducing demand characteristics. Future trainings should evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of the training in larger, more diverse samples.

Our novel communication training intervention promotes ACP by equipping caregivers with vital skills to maneuver difficult, but crucial conversations. As a next step, we will evaluate the efficacy of this training through a fully powered randomized controlled trial with caregivers of patients with malignant gliomas, and then subsequently among caregivers of patients with a variety of cancers. As all caregivers can benefit from the skills taught in this training, our goal is to refine this program to be beneficial to as many caregivers as possible.

Funding Details:

This research was supported by funding from the American Cancer Society (PEP-21-041-01-PCSM, PI: Allison Applebaum, Ph.D.), the T.J. Martell Society (PI: Allison Applebaum, Ph.D.) and from the National Institutes of Health (P30CA008748, PI: Craig Thompson, MD).

Disclosure Statement:

Dr. Applebaum receives funding from Blue Note Therapeutics. Dr. Diamond discloses unpaid editorial support from Pfizer Inc and serves on an advisory board for Day One Therapeutics and Springworks Therapeutics, both outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Data Sharing: Participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly. Individual requests for data sharing will need to be approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center IRB.

References

- AARP National Alliance for Caregiving. (2016). Cancer Caregiving in the U.S. An Intense, Episodic, and Challenging Care Experience. http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CancerCaregivingReport_FINAL_June-17-2016.pdf

- Applebaum AJ, & Breitbart W. (2013). Care for the cancer caregiver: a systematic review. Palliative and Supportive Care, 11(3), 231–252. 10.1017/s1478951512000594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Gremore TM, Wiesenthal N, Aldridge W, Fredman SJ, Stanton SE, Scott JL, Halford KW, & Keefe FJ (2009). A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology, 18(3), 276–283. 10.1002/pon.1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, Smith G, Paladino J, Lipsitz S, Gawande AA, & Block SD (2015). Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: a randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open, 5(10), e009032. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RF, Bylund CL, Gueguen JA, Diamond C, Eddington J, & Kissane D. (2010). Developing Patient-Centered Communication Skills Training for Oncologists: Describing the Content and Efficacy of Training. Communication Education, 59(3), 235–248. 10.1080/03634521003606210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budin WC, Hoskins CN, Haber J, Sherman DW, Maislin G, Cater JR, Cartwright-Alcarese F, Kowalski MO, McSherry CB, Fuerbach R, & Shukla S. (2008). Breast cancer: education, counseling, and adjustment among patients and partners: a randomized clinical trial. Nursing research, 57(3), 199–213. 10.1097/01.nnr.0000319496.67369.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund CL, Brown RF, Bialer PA, Levin TT, Lubrano di Ciccone B, & Kissane DW (2011). Developing and implementing an advanced communication training program in oncology at a comprehensive cancer center. Journal of Cancer Education, 26(4), 604–611. 10.1007/s13187-011-0226-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, McKee DC, Edwards CL, Herman SH, Johnson LE, Colvin OM, McBride CM, & Donatucci C. (2007). Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners. A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer, 109(2 Suppl), 414–424. 10.1002/cncr.22355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catt S, Chalmers A, & Fallowfield L. (2008). Psychosocial and supportive-care needs in high-grade glioma. Lancet Oncology, 9(9), 884–891. 10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70230-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA, Fulkerson WJ, Goldman LE, Knaus WA, Lynn J, Oye R, Bergner M, Damiano AM, Hakim RB, Murphy DJ, Teno JM, Virnig BA, Wagner DP, Wu AW, Yasui Y, Robinson DK, & Kreling B. (1995). A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA, 274 20, 1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, & Silvester W. (2010). The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 340, c1345. 10.1136/bmj.c1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond EL, Prigerson HG, Correa DC, Reiner A, Panageas K, Kryza-Lacombe M, Buthorn J, Neil EC, Miller AM, DeAngelis LM, & Applebaum AJ (2017). Prognostic awareness, prognostic communication, and cognitive function in patients with malignant glioma. Neuro-Oncology, 19(11), 1532–1541. 10.1093/neuonc/nox117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran GT (1981). There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Given B, Given CW, Sikorskii A, Jeon S, Sherwood P, & Rahbar M. (2006). The impact of providing symptom management assistance on caregiver reaction: results of a randomized trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 32(5), 433–443. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, Dodek P, Lamontagne F, You JJ, Tayler C, Porterfield P, Sinuff T, & Simon J. (2013). Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(9), 778–787. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz SA, Campo S, & Chiu WT (2002). Cancer patients’ desires for communication of prognosis information. Health Communication, 14(2), 221–241. 10.1207/s15327027hc1402_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent EE, Mollica MA, Buckenmaier S, & Wilder Smith A. (2019). The Characteristics of Informal Cancer Caregivers in the United States. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 35(4), 328–332. 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick DL (1967). Evaluation in Training. In Craig RL (Ed.), Training and Development Handbook (pp. 87–112). McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, Bialer PA, Levin TT, Maloney EK, & D’Agostino TA (2012). Communication skills training for oncology professionals. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(11), 1242–1247. 10.1200/jco.2011.39.6184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin TT, Moreno B, Silvester W, & Kissane DW (2010). End-of-life communication in the intensive care unit. General Hospital Psychiatry, 32(4), 433–442. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Corner GW, Sweeney CR, Wiener L, Roberts KE, Baser RE, Li Y, Breitbart W, Kissane DW, & Prigerson HG (2015). Mental Health Services for Parents Who Lost a Child to Cancer: If We Build Them, Will They Come? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(20), 2246–2253. 10.1200/jco.2014.59.0406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke EA, & Latham GP (2006). New Directions in Goal-Setting Theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265–268. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lubrano B, Brown RF, Gueguen JA, Bylund CL, & Kissane DW (2010). Interviewing patients using interpreters in an oncology setting: initial evaluation of a communication skills module. Annals of Oncology, 21(1), 27–32. 10.1093/annonc/mdp289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, & Wang J. (2014). A longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial of advance care planning for teens with cancer: anxiety, depression, quality of life, advance directives, spirituality. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(6), 710–717. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwit SJ, & Datson SL (2002). Disclosure preferences about terminal illness: an examination of decision-related factors. Death Studies, 26(1), 1–20. 10.1080/07481180210144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson ME, Maciejewski PK, Zhang B, Wright AA, Trice ED, Muriel AC, Friedlander RJ, Fasciano KM, Block SD, & Prigerson HG (2009). Mental health, treatment preferences, advance care planning, location, and quality of death in advanced cancer patients with dependent children. Cancer, 115(2), 399–409. 10.1002/cncr.24002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, & Schafenacker A. (2005). Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology, 14(6), 478–491. 10.1002/pon.871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, & Mood DW (2010). Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 60(5), 317–339. 10.3322/caac.20081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehrson C, Banerjee SC, Manna R, Shen MJ, Hammonds S, Coyle N, Krueger CA, Maloney E, Zaider T, & Bylund CL (2016). Responding empathically to patients: Development, implementation, and evaluation of a communication skills training module for oncology nurses. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(4), 610–616. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salander P. (1996). Brain Tumor as a Threat to Life and Personality. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 14(3), 1–18. 10.1300/J077v14n03_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JL, Halford WK, & Ward BG (2004). United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1122–1135. 10.1037/0022-006x.72.6.1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Zyzanski SJ, Rose JH, & Zhang AY (2008). The Cancer Communication Assessment Tool for Patients and Families (CCAT-PF): a new measure. Psychooncology, 17(12), 1216–1224. 10.1002/pon.1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PD, Martin B, Chewning B, Hafez S, Leege E, Renken J, & Smedley Ramos R. (2018). Improving health care communication for caregivers: A pilot study. Gerontology & geriatrics education, 39(4), 433–444. 10.1080/02701960.2016.1188810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings A, & Lynch TJ (2010). Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 363(8), 733–743. 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen PY, & Kesari S. (2008). Malignant gliomas in adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(5), 492–507. 10.1056/NEJMra0708126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AA, Mack JW, Kritek PA, Balboni TA, Massaro AF, Matulonis UA, Block SD, & Prigerson HG (2010). Influence of patients’ preferences and treatment site on cancer patients’ end-of-life care. Cancer, 116(19), 4656–4663. 10.1002/cncr.25217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You JJ, Fowler RA, & Heyland DK (2014). Just ask: discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. Cmaj, 186(6), 425–432. 10.1503/cmaj.121274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]