Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients could not receive timely healthcare services due to limited availability and access to healthcare resources and services. Previous studies found that access to intensive care unit (ICU) beds saves lives, but they overlooked the temporal dynamics in the availability of healthcare resources and COVID-19 cases. To fill this gap, our study investigated daily changes in ICU bed accessibility with an enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) method in the state of Texas. Along with the increased temporal granularity of measurements, we uncovered two phenomena: 1) aggravated spatial inequality of access during the pandemic, and 2) the retrospective relationship between insufficient ICU bed accessibility and the high case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 in rural areas. Our findings suggest that those locations should be supplemented with additional healthcare resources to save lives in future pandemic scenarios.

Keywords: Spatial accessibility, COVID-19, Healthcare resources, Case-fatality ratio

1. Introduction

Since the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 (Ducharme, 2020), most countries around the world have made an effort to manage healthcare resources and reduce the death toll related to COVID-19. Accordingly, studies investigated spatiotemporal patterns of outbreaks (Desjardins et al., 2020; Lyu et al., 2021) or underlying factors contributing to COVID-19 mortality, such as socioeconomic variables (Sun et al., 2021) and health conditions of patients (Akinwumiju et al., 2022). In addition, the importance of healthcare infrastructure specialized in acute respiratory disease, intensive care unit (ICU) beds as an example, has been spotlighted (Walters, Najmabadi, & Platoff, 2020). Under these circumstances, several accessibility studies examine the spatial interactions among supply (healthcare resources), demand (COVID-19 patients), and mobility (travel between supply and demand) (Kang et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021; Pereira et al., 2021). They contributed to identifying the spatial inequalities of healthcare access and addressing the mismatches between supply and demand during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The existing spatial accessibility literature overlooked the underlying dynamic changes in healthcare availability and confirmed COVID-19 cases, whereas these two variables have significantly fluctuated across space and over time during the COVID-19 pandemic. In detail, some studies were limited to assuming that the entire supply of healthcare resources was available (Kang et al., 2020) or partially implementing the spatial variation of ICU bed availability without its temporal changes (Pereira et al., 2021). Others only focused on the fluctuation in demand (the number of COVID-19 patients) (Kim et al., 2021). However, both variables related to healthcare accessibility have substantial temporal changes during the pandemic. For example, many hospitals in Texas were short of healthcare resources, particularly ICU beds corresponding to the acute increase of COVID-19 patients in July 2020 (Walters et al., 2020). There were only 24 available ICU beds out of 1614 (1.4% availability) on July 15, 2020, in Harris County, Texas. In addition, Harris County had the maximum number of COVID-19 patients (4026) on December 24, 2021, and the minimum number (24) on June 19, 2021 (Southeast Texas Regional Advisory Council, 2020).

Increased availability of data sources related to COVID-19 and recent advancements in computational infrastructure can help address the limitations of existing spatial accessibility literature. For example, Johns Hopkins COVID-19 dashboard is the most widely cited data source that keeps track of COVID-19 cases and deaths worldwide (Dong et al., 2020). Not only does it increase the transparency of data, but it also enables the investigation of the impact of COVID-19. In addition, local governments (e.g., city or state) provide more detailed COVID-19 data, such as healthcare usage, with their own dashboard to actively monitor the spread of the virus within their municipalities (Southeast Texas Regional Advisory Council, 2020). With the help of cyberGIS – cyber-based geographic information science and systems (S. Wang, 2010), many studies investigate complex geospatial problems such as spatial accessibility through computation- and data-intensive approaches (Kang et al., 2020; Lyu et al., 2021).

Under these circumstances, our study aims to capture daily changes in ICU bed accessibility from July 1, 2020, to December 31, 2021, by considering the temporal variations of ICU bed availability and confirmed COVID-19 cases in the state of Texas. On top of the general approach of spatial accessibility investigating the spatial interaction between supply and demand (Luo & Wang, 2003; F. Wang, 2012), we incorporate the daily variations in the two variables (supply: availability of ICU beds, demand: confirmed COVID-19 cases) to reflect the daily changes in ICU bed accessibility. Specifically, we employ an enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) method (Luo & Qi, 2009) with a 60-min threshold travel time and log-logistic distance decay function (Delamater et al., 2013; Jia et al., 2017). We then compare the results of daily accessibility measurements (named dynamic measurements) with those of the static accessibility measurement, which does not consider the temporal changes and assumes the total capacity of ICU beds over the cumulative confirmed COVID-19 cases. The comparison focuses on the following two applications: 1) correlation analyses (Kendall's τ (tau)) between ICU bed accessibility and the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 (the number of deaths per 1000 confirmed cases) and 2) the assessment of spatial access inequality based on the Gini index (Gini, 1912). The following three research questions are addressed: 1) how does ICU bed accessibility differ, as the ICU bed availability (supply) and confirmed COVID-19 cases change over time? 2) how did the daily changes of insufficient accessibility relate to the higher case-fatality ratio of COVID-19? 3) how does static measurement potentially bias the interpretation of accessibility?

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first approach encompassing temporal dynamics observed during the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., decreased availability of healthcare resources and the surge of confirmed COVID-19 cases) for measuring healthcare accessibility. In addition, we discover the retrospective correlation between insufficient ICU bed access and high case-fatality ratio in rural counties in Texas. Furthermore, we uncover potential misinterpretations of access inequality when the temporal aspects are not considered. Given that many patients could not get admitted to hospitals due to the shortage of healthcare resources during the pandemic (Walters et al., 2020), identifying locations of increased death related to insufficient accessibility and their spatial disparity could provide insight to mitigate the case-fatality ratio in the future (Park & Goldberg, 2022).

2. Literature review

The integration of temporal changes into spatial accessibility assessment has been broadly studied for various urban infrastructures, such as grocery stores (Järv et al., 2018), healthcare resources (Xia et al., 2019), and job opportunities (Hu & Downs, 2019). Under the enhanced data availability of high temporal granularity data, the discourse of ‘high-frequency cities’ demonstrated that the use of such data would uncover hidden temporal patterns of spatial dynamics (Batty, 2020; Kandt & Batty, 2021). In this sense, much attention has been particularly paid to the temporal changes that occurred within 24 h in accessibility. Studies aimed to reveal dynamic changes in spatial accessibility owing to time-dependent supply (e.g., opening hours), demand (e.g., various locations of people), and mobility (e.g., estimated travel time under traffic congestion) (Neutens, 2015; Park & Goldberg, 2021). For example, a full set of temporal dynamic inputs (i.e., supply, demand, and mobility) was utilized to assess hourly changes in the measures of spatial accessibility to EV charging stations over 24 h (Park, Kang, Goldberg, & Hammond, 2022 also argued that static measurements of accessibility, which neglect temporal changes of input variables, could not explain the geographical distributions of accessibility during daytime (Hu & Downs, 2019; Järv et al., 2018).

Besides the investigation of temporal changes within a day, a few studies examined and compared spatial accessibility with a longer temporal extent (e.g., monthly or yearly). Yang and Mao (2018) explored how spatial accessibility to physicians had changed within a period of three decades (from 1990 to 2010), as more healthcare resources and road infrastructure were provided in the state of Florida. In their study, the impact of road network expansion was more marginal than the ones of population growth and physician increase, meaning that the surge and decrease of supply and demand have a more significant role in tracking longer temporal changes in spatial accessibility. A similar approach was also conducted in the context of COVID-19. Kim et al. (2021) incorporated the temporal variation of COVID-19 cases into accessibility measurements and delineated how the spatial clusters of sufficient accessibility locations change according to the surge and decline of patients.

The importance of incorporating temporal aspects into spatial accessibility measurements has been widely recognized. However, combining the fluctuation in supply (e.g., healthcare availability) and demand (e.g., confirmed COVID-19 cases) has not been well addressed in spatial accessibility studies regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. Given that this fluctuation over time is normal in the real world, capturing the fluctuation in spatial accessibility measurement would enable better understanding of the relationship between spatial accessibility to healthcare and case-fatality ratio of COVID-19. In addition, considering temporal variation for a longer-term (e.g., over the years) would provide a solid understanding of where vulnerable locations from a disease are, resulting in more mortality rate (Han & Rogerson, 2003; Rogerson et al., 2006). Furthermore, temporal uncertainty in healthcare accessibility is a cause of spatial inequality of access and is potentially related to the high case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 due to unreliable access (Park & Goldberg, 2022). Therefore, our experiment is designed to identify vulnerable locations with limited access to healthcare resources (Kang et al., 2020; Luo & Qi, 2009; Luo & Wang, 2003) under the daily changes of accessibility-related variables and reveal which locations should have better infrastructure access (Kim et al., 2021; Pereira et al., 2021).

3. Research design

3.1. Study area and period

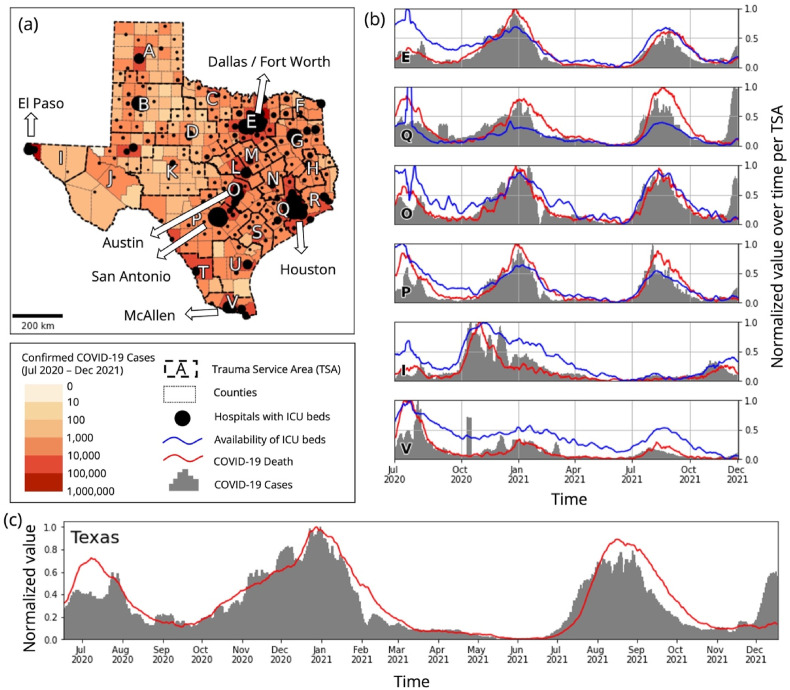

Our study area is the state of Texas in the United States (Fig. 1 (a)), which is the second-most populous state with a population of 29 million and has four major metropolitan statistical areas with more than two million residents: Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington (7.6 million), Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land (7.1 million), San Antonio-New Braunfels (2.5 million), and Austin-Round Rock (2.2 million). There are 254 counties in the study area, and they are grouped as 22 trauma service areas (TSA), which develop and provide emergency medical service trauma system plans. Please see Appendix 1 for the list of counties associated with TSA. The choropleth map and proportional symbols of Fig. 1(a) show the accumulated COVID-19 cases per county and the number of staffed ICU beds, respectively. Most confirmed COVID-19 cases were observed in large cities, such as Houston (TSA Q) and Dallas-Fort Worth (TSA E), where most healthcare resources are also located.

Fig. 1.

Study area (the state of Texas) and period (July 1, 2020–December 31, 2021): (a) spatial distribution of confirmed COVID-19 cases and staffed ICU beds, (b) temporal changes in confirmed cases and deaths of COVID-19 and the availability of ICU beds per TSA, and (c) overall temporal changes in confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths across the state.

The focus time of our analysis is from July 1, 2020, to December 31, 2021 (18 months) to cover the starting point of the first major spread of COVID-19 in Texas (July 2020) to the initial surge of Omicron (Fig. 1(c)). While the first case of the disease in Texas was announced on March 4, 2020 (Chris Van Deusen, 2020), the spread was relatively under control until July 2020. As of May 1, 2022, there have been four COVID-19 outbreaks in Texas: July and August 2020, November 2020–January 2021, July–September 2021, and December 2021–February 2022 (Texas Department of State Health Services, 2020). Fig. 1(b) demonstrates the temporal changes in COVID-19 cases (grey bars), death (a red line), and ICU bed availability (a blue line) per TSA. Given the considerable size of Texas, TSAs provided various temporal patterns of COVID-19 cases and death. For example, populous areas in the east and central Texas (TSAs E, Q, O, and P) experienced a similar surge and decline in COVID-19 cases and deaths to the overall trend of the entire state. On the other hand, locations bordering Mexico, such as El Paso (TSA I) and McAllen (TSA V) counties, had an acute increase of cases during the earlier outbreak, and their cases were relatively under control for the other periods. In addition, each TSA provided a distinctive temporal change in the ICU bed availability (blue lines) compared to other TSAs.

3.2. Data

We collected data from four different sources. First, we obtained COVID-19 data from the Texas Department of State Health Services COVID-19 Data (Texas Department of State Health Services, 2020). This includes daily confirmed cases and deaths of COVID-19 per county and the hospital usage data over time by TSA. Second, the number of staffed ICU beds per hospital data was provided by Definitive Healthcare (Definitive Healthcare, 2020). The dataset has the healthcare resources (e.g., the numbers of licensed, staffed, and ICU beds) along with the location information of associated hospitals. Third, we gathered the estimated population of each census tract from the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Lastly, a Python package, OSMnx, was employed to collect the road network from the OpenStreetMap across the state of Texas (Boeing, 2017).

3.3. Analytical workflow

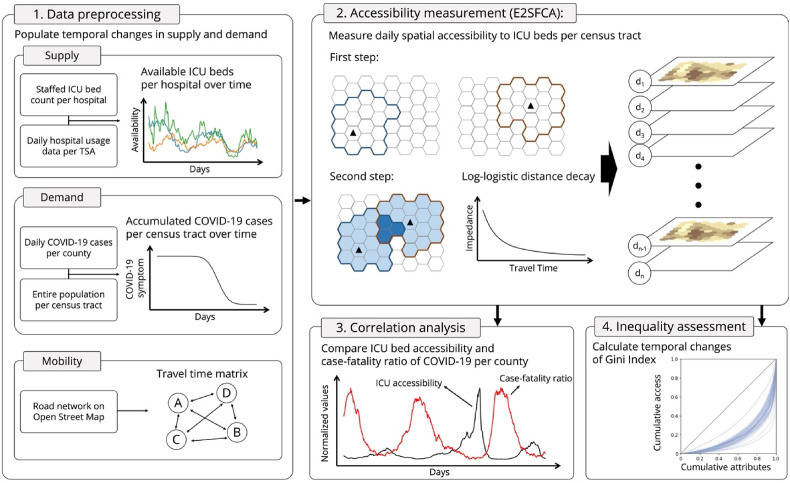

Our analysis is conducted in the following four steps (Fig. 2 ): data preprocessing, accessibility measurement, correlation analysis, and inequality assessment. The data processing step aims to populate temporal changes in supply (available ICU beds per hospital) and demand (confirmed COVID-19 cases per census tract). We also computed a travel time matrix between the hospitals (supply locations) and census tracts (demand locations) to facilitate further analysis. The second step, accessibility measurement, assesses daily ICU bed accessibility by capturing the temporal changes of both supply and demand variables. Third, we compare the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 with the measures of accessibility to uncover the retrospective linkage between increased death and insufficient access. Fourth, we calculate the daily changes in access inequality with the Gini index. In the third and fourth steps, we also examine different results obtained from static (without temporal changes) and dynamic (with temporal changes) accessibility measurements and explore the benefits of incorporating temporal changes into spatial accessibility assessments.

Fig. 2.

Analytical workflow: data preprocessing, accessibility measurement, correlation analysis, and inequality assessment.

3.3.1. Data preprocessing

The data preprocessing step prepared the supply, demand, and mobility data to be fed for the accessibility measurement step. First, we multiplied the availability of ICU beds per TSA each day and the number of staffed ICU beds per hospital to obtain the daily changes of available ICU beds per hospital (supply). Here, the availability of ICU beds refers to the sum of unoccupied ICU beds and the ones that were utilized by the COVID-19 patients, given that we measure ICU bed accessibility for confirmed COVID-19 patients. Second, we estimated COVID-19 cases per census tract each day by multiplying the proportion of the population of census tracts and the daily COVID-19 cases per county. We then accumulated the daily COVID-19 cases up to 25 days based on a cumulative probability distribution, which was computed based on COVID-19 recovery time, 18.70 ± 2.50 (Wu et al., 2020). Third, the travel time matrix between supply and demand locations was computed, considering the different travel speeds of road networks to increase measurement accuracy. Here, we assume that the travel time between locations is constant over time.

3.3.2. Spatial accessibility measurement

We utilized an E2SFCA method to assess daily changes in spatial accessibility to ICU beds during the COVID-19 pandemic under the interaction between the temporal changes of available ICU beds (supply) and the accumulated COVID-19 cases (demand). The method (Luo & Qi, 2009) enhances the original 2SFCA method (Luo & Wang, 2003), which employs multiple travel-time zones to integrate distance decay. Distance decay formalizes the idea that those further from a resource are less likely to utilize it. We used a large catchment area of 60 min to ensure that rural areas of Texas would have some level of access to ICU beds rather than being reported as completely unable to reach any hospital. Due to this large catchment area, we chose to use 10 different travel zones of 5-min increments up to 45 min and then 45–60 min (0–5, 5–10, …, 40–45, 45–60 min). Each travel-time zone has a weight applied to it based on the log-logistic function starting with 1 for those within the 0–5 min travel zone, falling to 0.0832 for the 45–60 min travel zone. These choices were informed by Delamater et al. (2013) and Jia et al. (2017).

Using these travel-time zones and weights, the E2SFCA method calculates access using two conceptually simple steps: calculating the supply-to-demand ratio for each hospital and then aggregating these ratios across space. We calculate the first step using:

| (1) |

where denotes the supply-to-demand ratio each day, represents the number of available ICU beds each day (d) at a hospital (j), indicates the accumulated COVID-19 cases at a census tract (k) each day (d), and is a distance decay weight provided by the log-logistic distribution.

This first step tells us about the weighted ratio for each hospital each day between available ICU beds and surrounding COVID-19 patients within 60 min of the hospital in our study area. The second step then aggregates these ratios across space by summing ratios at each demand location using:

| (2) |

where is the ratio of available ICU beds to the COVID-19 patients across space each day.

Variables in both steps are depreciated based on a log-logistic distance decay function which is defined as follows:

| (3) |

where indicates the travel time between locations i and j, and represents threshold travel time (i.e., 60 min). The scale () and shape () parameters are defined as 13.89 and 1.82, respectively, according to a hospital travel pattern survey (Delamater et al., 2013).

We also replicated the conventional approach from the literature (Kang et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021) to examine the significance of temporal changes in supply and demand. We named our approach dynamic measurement and the conventional approach static measurement for the rest of this paper. While dynamic measurement covers the temporal changes in both supply and demand, static measurement assumes that the full capacity of ICU beds is available for its supply. In addition, it also ignores temporal changes in confirmed COVID-19 cases and takes the entire COVID-19 cases over the study period as its demand. In other words, it does not take into account the variable representing each day (d) in Equations (1), (2)).

3.3.3. Correlation analysis

In the third step, we investigated the retrospective relationship between ICU bed accessibility and the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 at a county level. In detail, we employed Kendall's τ (tau) correlation coefficients because the distributions of those two variables are not linear. The method considers the variables based on their ranks but keeps their pairs. In addition, we matched the geographical unit of accessibility measures to the county level where the official COVID-19 data is provided. We multiplied the population and the accessibility of each census tract, summed the results, and then divided them by the total population of each county. Furthermore, we compared the correlation coefficients between static and dynamic measurements and examined how the static implementation may bias the interpretation of the retrospective linkage between insufficient access and increased case-fatality ratio.

3.3.4. Inequality assessment

For the final step, the Gini index is used to explore the spatial inequality of ICU access based on both static and dynamic measurements. We first compare the Gini index between static and dynamic measurements to examine how inequality would intensify when considering dynamics in ICU bed availability and confirmed COVID-19 cases. We then investigate the temporal changes of the disparity observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given dynamic changes in those variables were a substantial concern, we thoroughly assessed the inequality of access towards three different underlying attributes: cumulative distributions of location count, populations, and confirmed COVID-19 cases.

4. Results

4.1. Daily changes in ICU bed accessibility

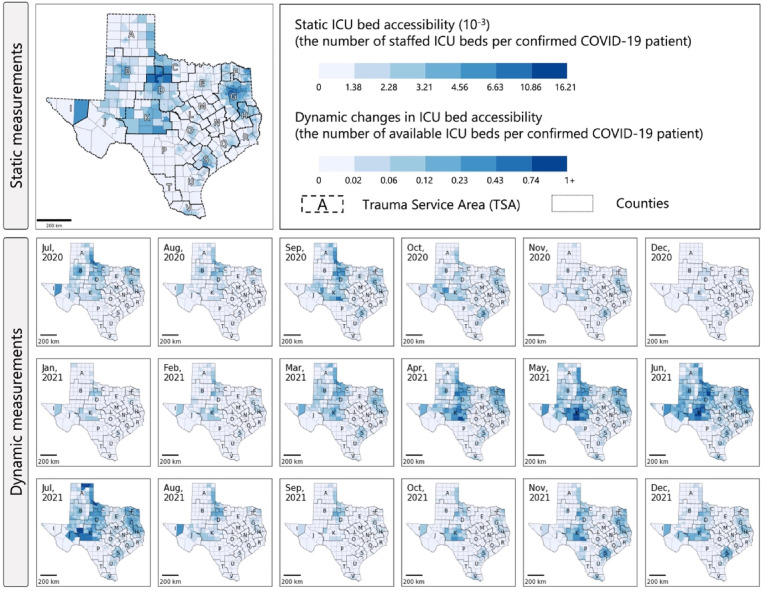

The maps in Fig. 3 represent the spatial distribution of ICU bed accessibility based on the static and dynamic measurements. Saturation in the maps indicates the level of accessibility of census tracts, and the boundaries of counties and TSA were provided to help with the understanding of the locations. Due to the nature of the employed datasets, the maps of the static and dynamic measurements in Fig. 3 are illustrated with different metrics. The static measurement assumed that the total capacity of healthcare resources is available for the accumulated confirmed COVID-19 cases for 18 months. The dynamic measurement considered temporal changes in supply (i.e., the available ICU bed each day) and demand (i.e., the accumulated confirmed COVID-19 cases for up to the past 25 days). The maps of the dynamic measurements that were taken from the 15th of each month demonstrate spatiotemporal patterns well, although our analysis was run for each day.

Fig. 3.

ICU bed accessibility per census tract during the COVID-19 pandemic in the state of Texas obtained from static and dynamic measurements.

Note: measures of 1+ indicate the locations that have ICU beds available more than the COVID-19 patients.

Daily assessment of ICU bed accessibility captures significant spatiotemporal changes, different from the results of static measurement (Fig. 3). The static measurement presented high accessibility for the census tracts within TSA D and G, a moderate degree of accessibility for the locations within TSA C, K, and S, and insufficient accessibility for those within TSA A, J, M, and P. However, the dynamic measurements revealed significant changes in locations showing high accessibility. In general, state-wide ICU bed accessibility was suppressed during the outbreaks identified by the Texas Department of State Health Services (2020) (July, August, November, and December of 2020, and January, February, August, and September of 2021). Their patterns contrasted with the COVID-19 positivity rate (see Appendix 2), as the accessibility measurement took the confirmed patients as its demand. In the meantime, some spatial disparities were also detected. Rural counties in West Texas (TSA C, D, and K) provided sufficient accessibility during the outbreak. In contrast, populous counties in North Texas (TSA E), Southeast Texas (TSA Q), and Central Texas (TSA O and P) showed marginal accessibility even outside of outbreak periods.

The differences of accessibility patterns between the static and dynamic measurements were attributed to how supply and demand variables were considered. The static measurement assumed that the staffed ICU beds (supply) were fully available and counted confirmed COVID-19 cases with a fixed time window as their demand. However, the dynamic measurements considered the temporal changes of the underlying variables (i.e., the availability of ICU beds and confirmed COVID-19 cases).

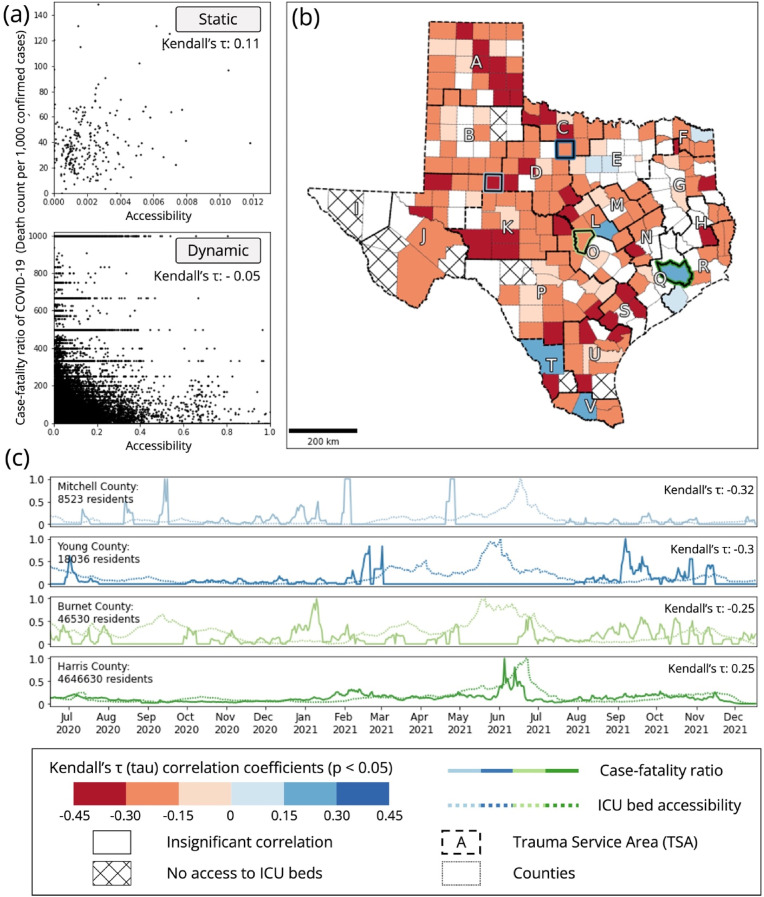

4.2. Correlation analysis between accessibility and case-fatality ratio per county

Correlation analysis based on Kendall's τ (tau) was employed to uncover the linkage between ICU bed accessibility (Fig. 3) and the COVID-19 case-fatality ratio (Appendix 3) during the pandemic. The scatter plots in Fig. 4 (a) demonstrate the overall relationship between accessibility (x-axis) and case-fatality ratio (y-axis), obtained from the static and dynamic measurements. Here, we aggregated the measures of accessibility at the county level to match the geographical unit of both data. The COVID-19 data was obtained at the county level, while the measures of accessibility were assessed at the census tract level.

Fig. 4.

County-level correlation analysis (Kendall's τ (tau)) between ICU bed accessibility and the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19: (a) scatter plots of accessibility and the case-fatality ratio for both static and dynamic measurements, (b) spatial distribution of Kendall's τ calculated between ICU bed accessibility and the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19, and (c) temporal changes in accessibility and case-fatality ratio for counties that provided high negative correlation coefficients.

Interestingly, the static and dynamic measurements provided opposite correlation coefficients to each other. The dynamic accessibility measurements presented a negative correlation coefficient (Kendall's τ: −0.05, p-value <0.05) with the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19, while the static accessibility measurements showed a positive correlation coefficient (Kendall's τ: 0.11, p-value <0.05). In other words, the dynamic measurements indicated that a high case-fatality ratio might be related to insufficient accessibility. However, the static measurements alluded that high case-fatality ratios were observed along with sufficient accessibility.

We further examined the retrospective relationship focusing on each county, and the spatial distributions of the correlation coefficients are shown in Fig. 4 (b). Here, we utilized Bonferroni Correction (Bonferroni, 1936) to provide more conservative statistical results, lowering the p-value from 0.05 to 0.0002 (i.e., 0.05/254 (number of counties)). Out of 254 counties in Texas, 179 counties presented statistically significant results; negative correlation coefficients were observed in 171 counties, and positive correlation coefficients were provided by eight counties. The remaining 75 counties were either statistically insignificant (65 counties) or had no access to ICU beds within the 60-min threshold travel time (10 counties). Fig. 4 (c) shows the temporal changes in the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 (solid lines) and ICU bed accessibility (dotted lines). Strong negative correlation coefficients were mainly presented from counties with small residential populations and far from major cities, such as Mitchell (sky blue boundary; Kendall's τ: −0.32, p-value <0.0002) and Young (blue boundary; Kendall's τ: −0.3, p-value <0.0002) counties. In addition, suburban counties (e.g., Burnet County; light green boundary; Kendall's τ: −0.25, p-value <0.0002) showed negative correlation coefficients. However, counties with big cities presented insignificant correlation results (e.g., Dallas County) or positive correlation coefficients (e.g., Harris County; green boundary; Kendall's τ: +0.25, p-value <0.0002).

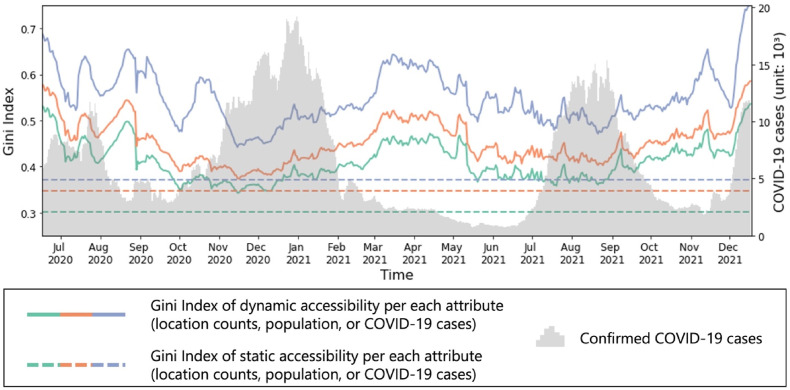

4.3. Inequality of ICU bed accessibility

With the Gini index, we assessed the inequality of ICU bed accessibility captured from the static and dynamic measurements (Fig. 5 ). The dashed and solid lines in the figure indicate the Gini index calculated from the static and dynamic measurements, respectively. Static measurement provided the Gini index of 0.31, 0.34, and 0.37 for the cumulative distribution of locations, populations, and confirmed COVID-19 cases, indicating that the spatial disparity of accessibility is not severe. However, the dynamic measurements showed an escalated Gini index, with a max of 0.54, 0.59, and 0.75 for the cumulative distribution of locations, populations, and confirmed COVID-19 cases, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Temporal changes in the inequality (Gini index) ICU bed accessibility over cumulative distributions of location counts, populations, and COVID-19 cases.

Significant temporal changes were also observed in the inequality of ICU bed accessibility during the pandemic. In general, the inequality was high during early outbreaks (i.e., July and August 2020) and gradually mitigated over time, given that more ICU beds were allocated for the COVID-19 patients in the later outbreaks. Before the surge of Omicron (i.e., December 2021), the cumulative distribution of locations (0.53), populations (0.58), and confirmed cases (0.69) provided the maximum Gini index on July 1, 2020. The minimum Gini index was observed on November 30, 2020, for the cumulative distribution of locations (0.34) and populations (0.37). The cumulative distribution of confirmed COVID-19 cases showed a minimum Gini index of 0.44 on November 29, 2020.

5. Discussion

Our analysis indicated that it is essential to consider temporal changes in the input variables, such as healthcare availability (supply) and confirmed COVID-19 cases (demand), to reveal the daily changes in accessibility and inequalities during the pandemic. In other words, static measurement, which was often employed in existing accessibility studies regarding COVID-19 (Kang et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021; Pereira et al., 2021), may cause biased interpretations of accessibility from the following two perspectives. First, the static measurement may misconstrue that the increased case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 was not related to ICU bed accessibility, given that the correlation analysis provided a positive correlation coefficient (Kendall's τ: 0.11, p-value <0.05). However, the dynamic measurements could explain their retrospective relationship (Kendall's τ: −0.05, p-value <0.05) as well as provide the heterogeneous spatial distribution of the correlation coefficients between ICU bed access and case-fatality ratio. Indeed, it was a critical issue that COVID-19 patients could not get proper service due to limited access to healthcare resources during the pandemic (Walters et al., 2020). These phenomena were more intensified in rural counties in Texas. Second, static measurements could overlook the issue of access disparity (Gini index 0.34), as they assume that the total capacity of healthcare resources is available. However, dynamic measurements revealed extremely high access inequality (Gini index 0.59) during the pandemic as the approach considers dynamic changes in both supply and demand.

Our study could support policy optimization on where extra resources should be allocated to save lives from future pandemic scenarios. Given that death caused by COVID-19 is closely related to socioeconomic status (Akinwumiju et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2021), locations that showed a high case-fatality ratio may be hit hard by future pandemics as well. In this context, our findings suggest placing additional healthcare resources, such as ICU beds or ventilators, in geographic areas that exhibited strong negative correlation coefficients between ICU bed accessibility and case-fatality ratio. Counties with big cities did not yield significant correlation coefficients (e.g., Dallas County) or positive correlation (e.g., Harris County), in contrast, rural or suburban locations had a substantial relationship. This may be attributed to the following two reasons. First, rural counties (e.g., Mitchell and Young counties) may have limited healthcare resources to treat their residents, so their availability fluctuated significantly even with a small number of inpatients. Second, insufficient accessibility in suburban counties (e.g., Burnet County) may be caused by decreased availability of healthcare resources in nearby major cities. In case the availability of healthcare resources decreases due to the surge of confirmed COVID-19 cases, major city residents could access alternative hospitals as many healthcare resources might be available in surrounding areas. However, suburban residents may have to rely on a limited number of hospitals.

The use of cyberGIS and spatial data science approach, harnessing high-performance computing infrastructure (S. Wang, 2016), enabled our accessibility measurements. To address the computational intensity challenge from the large-scale spatiotemporal analysis (i.e., daily changes of accessibility at a state level), we took advantage of parallel computing of accessibility measurements, as done by Kang (2020). The widespread shortage of healthcare resources was a bigger concern than initially anticipated and impacted access to healthcare resources in ways we have not seen before (Jacobs, 2021; Shalal & Nebehay, 2020; Walters et al., 2020). Rapidly updating measures of spatial accessibility, which accounts for temporal changes in supply and demand, can help policymakers and stakeholders make more informed decisions on where and when to allocate how much healthcare resources.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we assessed daily changes in spatial accessibility to ICU beds and investigated their relationship with the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 observed in Texas during the pandemic. We incorporated temporal changes in available ICU bed counts (i.e., supply) and confirmed COVID-19 cases (i.e., demand) into measurements to reveal the spatial and temporal variations in ICU bed accessibility. With the increased temporal granularity of spatial accessibility, our analysis uncovered the retrospective relationship between insufficient ICU bed accessibility and the high case-fatality ratio of COVID-19. For example, rural counties (e.g., Mitchell and Young counties) and suburban counties (e.g., Burnet County) showed increased death from COVID-19 when their ICU bed accessibility was insufficient. Given that these counties may have been impacted by both limited availability and spatial accessibility, they should be supplemented with additional healthcare resources to save lives for future pandemic scenarios and to mitigate access disparity. In addition, we found that the consideration of dynamic variables could help gain a better understanding of spatial inequality issues, as the dynamic measurements showed high inequality compared to the static measurement. Therefore, our study highlights that temporal aspects should be incorporated into spatial accessibility measurements to provide insight for policymakers.

Despite significant methodological findings and policy implications, our study has the following limitations. First, homogeneous temporal changes were assumed for larger geographical units due to the lack of fine granularity data. ICU bed availability data was provided at the TSA level, and COVID-19 data was collected at the county level. Second, our measurements estimated the degree of supply (available ICU beds) based on the availability ratio instead of the actual count. This means that our model also did not consider the increase in ICU bed capacity for some hospitals in response to the surge of COVID-19 patients. Third, the mobility-related variables, such as threshold travel time and log-logistics distance decay, were based on pre-pandemic hospitalization patterns. But the patterns of COVID-19 patients could be different. Fourth, we did not consider temporal changes in travel time from a location to a hospital, due to the lack of high-resolution mobility data over the entire state. Our future research will focus on improving the accuracy of the accessibility measurement with high spatial and temporal granularity data for both healthcare resources and patients. In addition, we will employ advanced 2SFCA methods, such as balanced FCA (Paez et al., 2019) or adjusted FCA (Lin & Cromley, 2022), to address the issues of overestimated demand in the metric and to better explain the people's flow on avoiding congested locations.

Data and code availability statement

The data and codes that support the finding of this study are published with a DOI at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20398995 and the CyberGISX Platform (https://cybergisxhub.cigi.illinois.edu/notebook/daily-changes-in-spatial-accessibility-to-intensive-care-unit-icu-beds-and-their-relationship-with-the-case-fatality-ratio-of-covid-19-in-the-state-of-texas)

Author statement

Jinwoo Park: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Project administration. Alexander Michels: Data Curation, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft. Fangzheng Lyu: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Su Yeon Han: Writing - Review & Editing. Shaowen Wang: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under grant number: 2112356. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NSF. Our computational work used Virtual ROGER, which is a geospatial supercomputer supported by the CyberGIS center for Advanced Digital and Spatial Studies and the School of Earth, Society and Environment at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Handling Editor: Dr. Y.D. Wei

Appendix 1. Counties associated with Trauma Service Area (TSA)

| TSA | Population | Counties |

|---|---|---|

| A | 428,102 | Armstrong, Briscoe, Carson, Childress, Collingsworth, Dallam, Deaf Smith, Donley, Grey, Hall, Hansford, Hartley, Hemphill, Hutchinson, Lipscomb, Moore, Ochiltree, Oldham, Parmer, Potter, Randall, Roberts, Sherman, Swisher, Wheeler |

| B | 494,388 | Bailey, Borden, Castro, Cochran, Cottle, Crosby, Dawson, Dickens, Floyd, Gaines, Garza, Hale, Hockley, Kent, King, Lamb, Lubbock, Lynn, Motley, Scurry, Terry, Yoakum |

| C | 218,722 | Archer, Baylor, Clay, Foard, Hardeman, Jack, Montague, Wichita, Wilbarger, Young |

| D | 300,946 | Brown, Callahan, Coleman, Comanche, Eastland, Fisher, Haskell, Jones, Knox, Mitchell, Nolan, Shackelford, Stephens, Stonewall, Taylor, Throckmorton |

| E | 7,712,809 | Collin, Cooke, Dallas, Denton, Ellis, Erath, Fannin, Grayson, Hood, Hunt, Johnson, Kaufman, Navarro, Palo Pinto, Parker, Rockwall, Somervell, Tarrant, Wise |

| F | 271,962 | Bowie, Cass, Delta, Hopkins, Lamar, Morris, Red River, Titus |

| G | 954,053 | Anderson, Camp, Cherokee, Franklin, Freestone, Gregg, Harrison, Henderson, Houston, Marion, Panola, Rains, Rusk, Shelby, Smith, Trinity, Upshur, Van Zandt, Wood |

| H | 270,029 | Angelina, Nacogdoches, Polk, Sabine, San Augustine, San Jacinto, Tyler |

| I | 842,691 | Culberson, El Paso, Hudspeth |

| J | 469,024 | Andrews, Brewster, Crane, Ector, Glasscock, Howard, Jeff Davis, Loving, Martin, Midland, Pecos, Presidio, Reeves, Terrell, Upton, Ward, Winkler |

| K | 170,475 | Coke, Concho, Crockett, Irion, Kimble, McCulloch, Mason, Menard, Reagan, Runnels, Schleicher, Sterling, Sutton, Tom Green |

| L | 482,707 | Bell, Coryell, Hamilton, Lampasas, Milam, Mills |

| M | 345,763 | Bosque, Falls, Hill, Limestone, McLennan |

| N | 352,598 | Brazos, Burleson, Grimes, Leon, Madison, Robertson, Washington |

| O | 2,241,686 | Bastrop, Blanco, Burnet, Caldwell, Fayette, Hays, Lee, Llano, San Saba, Travis, Williamson |

| P | 2,775,583 | Atascosa, Bandera, Bexar, Comal, Dimmit, Edwards, Frio, Gillespie, Gonzales, Guadalupe, Karnes, Kendall, Kerr, Kinney, La Salle, Maverick, Medina, Real, Uvalde, Val Verde, Wilson, Zavala |

| Q | 6,237,465 | Austin, Colorado, Fort Bend, Harris, Matagorda, Montgomery, Walker, Waller, Wharton |

| R | 1,263,163 | Brazoria, Chambers, Galveston, Hardin, Jasper, Jefferson, Liberty, Newton, Orange |

| S | 176,519 | Calhoun, DeWitt, Goliad, Jackson, Lavaca, Victoria |

| T | 293,061 | Jim Hogg, Webb, Zapata |

| U | 596,602 | Aransas, Bee, Brooks, Duval, Jim Wells, Kenedy, Kleberg, Live Oak, McMullen, Nueces, Refugio, San Patricio |

| V | 1,362,508 | Cameron, Hidalgo, Starr, Willacy |

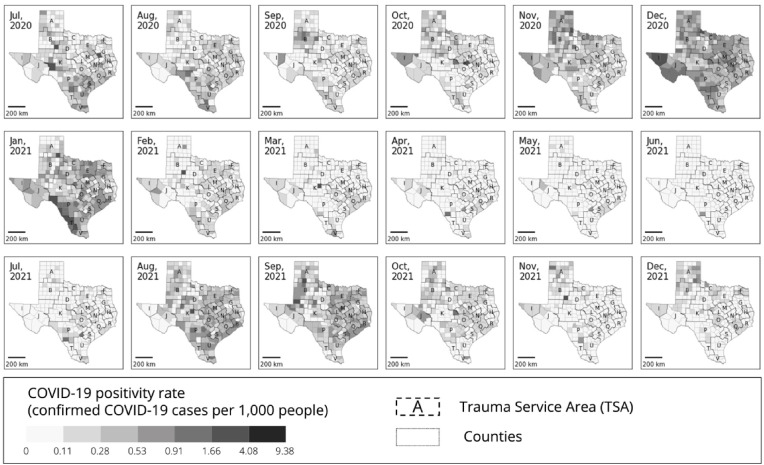

Appendix 2. Spatiotemporal changes in the positivity rate of confirmed COVID-19 cases

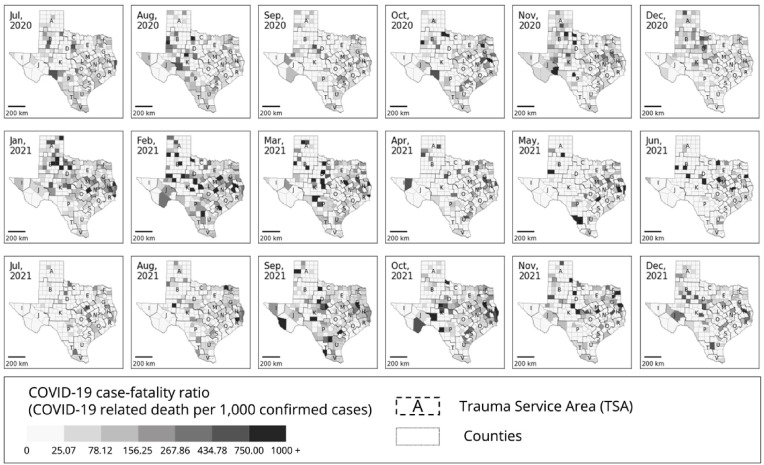

Appendix 3. Spatiotemporal changes in the case-fatality ratio of COVID-19

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Akinwumiju A.S., Oluwafemi O., Mohammed Y.D., Mobolaji J.W. Geospatial evaluation of COVID-19 mortality: Influence of socio-economic status and underlying health conditions in contiguous USA. Applied Geography. 2022;141 doi: 10.1016/J.APGEOG.2022.102671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty M. The routledge companion to smart cities. Routledge; 2020. Defining smart cities; pp. 51–60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boeing G. OSMnx: New methods for acquiring, constructing, analyzing, and visualizing complex street networks. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. 2017;65:126–139. doi: 10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2017.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonferroni C. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilita. Pubblicazioni Del R Istituto Superiore Di Scienze Economiche e Commericiali Di Firenze. 1936;8:3–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chris Van D. DSHS announces first Case of COVID-19 in Texas. 2020. https://www.dshs.texas.gov/news/releases/2020/20200304.aspx

- Delamater P.L., Messina J.P., Grady S.C., WinklerPrins V., Shortridge A.M. Do more hospital beds lead to higher hospitalization rates? A spatial examination of roemer's law. PLoS One. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins M.R., Hohl A., Delmelle E.M. Rapid surveillance of COVID-19 in the United States using a prospective space-time scan statistic: Detecting and evaluating emerging clusters. Applied Geography. 2020;118 doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme J. (2020, March 11). The WHO just declared coronavirus COVID-19 a pandemic | time. https://time.com/5791661/who-coronavirus-pandemic-declaration/

- Gini C. Variabilità e mutabilità. C. Cuppini; Bologna: 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Han D., Rogerson P.A. In: Geographic information systems and health applications. Khan O.A., Skinner R., editors. IGI Global; 2003. Application of a GIS-based statistical method to access spatio-temporal changes in breast cancer clustering in the northeastern United States; pp. 114–138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare D. Definitive healthcare bed locations. 2020. https://www.definitivehc.com/

- Hu Y., Downs J. Measuring and visualizing place-based space-time job accessibility. Journal of Transport Geography. 2019;74:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs A. Nursing is in crisis’: Staff shortages put patients at risk. The New York Times. 2021 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/21/health/covid-nursing-shortage-delta.html? Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Järv O., Tenkanen H., Salonen M., Ahas R., Toivonen T. Dynamic cities: Location-based accessibility modelling as a function of time. Applied Geography. 2018;95:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2018.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia P., Wang F., Xierali I.M. Using a Huff-based model to delineate hospital service areas. The Professional Geographer. 2017;69(4):522–530. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2016.1266950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kandt J., Batty M. Smart cities, big data and urban policy: Towards urban analytics for the long run. Cities. 2021;109 doi: 10.1016/J.CITIES.2020.102992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J.Y., Michels A., Lyu F., Wang S., Agbodo N., Freeman V.L., Wang S. Rapidly measuring spatial accessibility of COVID-19 healthcare resources: A case study of Illinois, USA. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2020;19(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12942-020-00229-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Ghorbanzadeh M., Horner M.W., Ozguven E.E. Identifying areas of potential critical healthcare shortages: A case study of spatial accessibility to ICU beds during the COVID-19 pandemic in Florida. Transport Policy. 2021;110:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Cromley G. A narrative analysis of the 2SFCA and i2SFCA methods. International Journal of Geographical Information Science. 2022;36(5):943–967. doi: 10.1080/13658816.2021.1986831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W., Qi Y. An enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) method for measuring spatial accessibility to primary care physicians. Health & Place. 2009;15(4):1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W., Wang F. Measures of spatial accessibility to health care in a GIS environment: Synthesis and a case study in the Chicago region. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. 2003;30(6):865–884. doi: 10.1068/b29120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu F., Kang J.-Y., Wang S., Han S.Y., Li Z., Wang S. In: Human dynamics in smart cities. Shaw S.-L., Sui D., editors. Springer; Cham: 2021. Multi-scale CyberGIS analytics for detecting spatiotemporal patterns of COVID-19; pp. 217–232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neutens T. Accessibility, equity and health care: Review and research directions for transport geographers. Journal of Transport Geography. 2015;43:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paez A., Higgins C.D., Vivona S.F. Demand and level of service inflation in Floating Catchment Area (FCA) methods. PLoS One. 2019;14(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Goldberg D.W. A review of recent spatial accessibility studies that benefitted from advanced geospatial information: Multimodal transportation and spatiotemporal disaggregation. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2021;10(8):532. doi: 10.3390/ijgi10080532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Goldberg D.W. An examination of the stochastic distribution of spatial accessibility to intensive care unit beds during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of the greater Houston area of Texas. Geographical Analysis. 2022 doi: 10.1111/gean.12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Kang J.-Y., Goldberg D.W., Hammond T.A. Leveraging temporal changes of spatial accessibility measurements for better policy implications: A case study of electric vehicle (EV) charging stations in seoul, South Korea. International Journal of Geographical Information Science. 2022;36(6):1185–1204. doi: 10.1080/13658816.2021.1978450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira R.H.M., Braga C.K.V., Servo L.M., Serra B., Amaral P., Gouveia N., Paez A. Geographic access to COVID-19 healthcare in Brazil using a balanced float catchment area approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;273 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson P.A., Sinha G., Han D. Recent changes in the spatial pattern of prostate cancer in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(2 SUPPL.):S50–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalal A., Nebehay S. Reuters; 2020. WHO warns of global shortage of medical equipment to fight coronavirus.https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-idUSKBN20Q14O Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Southeast Texas Regional Advisory Council COVID tracker. 2020. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYjU5MzU4NjAtZWJjMC00MTllLTkwYjYtMzE4ODY1YjAyMGU2IiwidCI6ImI3MjgwODdjLTgwZTgtNGQzMS04YjZmLTdlMGUzYmUxMGUwOCIsImMiOjN9

- Sun Y., Hu X., Xie J. Spatial inequalities of COVID-19 mortality rate in relation to socioeconomic and environmental factors across England. Science of the Total Environment. 2021;758 doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2020.143595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Texas Department of State Health Services Texas COVID-19 data. 2020. https://dshs.texas.gov/coronavirus/additionaldata/

- U.S. Census Bureau Total population - census Bureau table. 2020. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Population%20Total&g=0400000US48%241400000&tid=ACSDT5Y2020.B01003

- Wang S. A cyberGIS framework for the synthesis of cyberinfrastructure, GIS, and spatial Analysis. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2010;100(3):535–557. doi: 10.1080/00045601003791243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters E., Najmabadi S., Platoff E. The Texas Tribune; 2020. Texas hospitals are running out of drugs, beds, ventilators and even staff | the Texas Tribune.https://www.texastribune.org/2020/07/14/texas-hospitals-coronavirus/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. Measurement, optimization, and impact of health care accessibility: A methodological review. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2012;102(5):1104–1112. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.657146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. CyberGIS and spatial data science. GeoJournal 2016 81:6. 2016;81(6):965–968. doi: 10.1007/S10708-016-9740-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Li W., Shi X., Chen Z., Jiang B., Liu J., Wang D., Liu C., Meng Y., Cui L., Yu J., Cao H., Li L. Early antiviral treatment contributes to alleviate the severity and improve the prognosis of patients with novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Journal of Internal Medicine. 2020;288(1):128–138. doi: 10.1111/JOIM.13063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T., Song X., Zhang H., Song X., Kanasugi H., Shibasaki R. Measuring spatio-temporal accessibility to emergency medical services through big GPS data. Health & Place. 2019;56:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Mao L. Understanding temporal change of spatial accessibility to healthcare: An analytic framework for local factor impacts. Health & Place. 2018;51:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and codes that support the finding of this study are published with a DOI at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20398995 and the CyberGISX Platform (https://cybergisxhub.cigi.illinois.edu/notebook/daily-changes-in-spatial-accessibility-to-intensive-care-unit-icu-beds-and-their-relationship-with-the-case-fatality-ratio-of-covid-19-in-the-state-of-texas)