Abstract

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a common complication of diabetes. DCM causes extensive lesions on cardiac microvasculature that is predominantly cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMECs). Reducing high glucose (HG)-induced damage such as oxidative damage and apoptosis could alleviate the development of DCM. The natural polyphenol resveratrol (RSV) is widely suggested as a cardioprotective agent that protect against DCM. However, limited evidence supports the protection of RSV against oxidative damage and apoptosis and study on the direct effects of RSV in CMEC is missing. Therefore, the current paper aimed to illustrate if RSV could attenuate oxidative stress and apoptosis in CMEC and to investigate the underlying mechanisms. Our data showed that HG elevated reactive oxygen species, malondialdehyde, decreased superoxide dismutase activity, increased apoptotic cell percentage in CMEC, which were reversed by RSV administration. In addition, RSV demonstrated antioxidative and anti-apoptotic effects in CMEC through AMPK/Sirt1 activation, further confirmed by AMPK inhibition or Sirt1 silencing. This study provides new evidence to support RSV as a potential cardioprotective alternative in treating DCM.

Keywords: Diabetic cardiomyopathy, Cardiac microvascular endothelial cell, Oxidative stress, Apoptosis, Resveratrol, AMPK/Sirt1

Highlights

-

•

Resveratrol attenuates high glucose (HG)-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in primary cultured cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMECs).

-

•

Resveratrol enhances AMPK/Sirt1 signaling and protects CMECs under HG environment potentially by mediating AMPK/Sirt1 signaling.

1. Introduction

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a common diabetic complication that significantly burdens public health worldwide [1,2]. It is the main cause of heart failure in patients with diabetes in which hypertension, atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease are absent. DCM causes extensive focal myocardial necrosis on the basis of metabolic disorders and lesions on cardiac microvasculature [3]. Cardiac microvasculature mainly consists of monolayer cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMECs) and is predominantly located at the end of the heart circulation. By controlling myocardial perfusion and coronary reserve, cardiac microvasculature is the important part of myocardial blood perfusion [4]. Given the direct contact of CMEC with blood, hyperglycemic environment causes CMEC dysfunction and leads to insufficient blood supply to myocardium as well as cardiomyocyte dysfunction [5]. These disorders in cardiac microvascular are closely related to the occurrence and development of DCM [5,6]. Therefore, reducing CMEC injury can improve cardiomyocyte function and alleviate DCM [7,8].

CMEC protection could be achieved by strategies such as mitigating oxidative stress and apoptosis. This could be evidenced by a number of research that suggest oxidative stress and apoptosis as the key contributors to cardiovascular damage [9,10]. Hyperglycemic environment induces the imbalance of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and related defensing mechanisms, damaging macromolecules including lipids, proteins and nucleic acids and exacerbating endothelial cell dysfunction [11]. Additionally, hyperglycemic environment activates the intrinsic death pathway and induces endothelial cell apoptosis [12]. This suggest that the reduction of oxidative stress and apoptosis may improve high glucose (HG)-induced endothelial cell and microvascular barrier dysfunction.

The central metabolic switch AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is involved in modulating an array of cellular processes, including mitochondrial metabolism, apoptosis, inflammation, cell growth, and autophagy [13]. Silent information regulator T1 (Sirt1), a class III histone deacetylase dependent on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), participates in many cellular biological processes, such as redox homeostasis, apoptosis, inflammation, senescence, and longevity [14]. Importantly, the activation of the AMPK/Sirt1 axis plays a role in restoring cardiac function and alleviating DCM [15]. In a diabetic rat model, AMPK/Sirt1 activation inhibited hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis [16]. Consequently, compounds that suppress oxidative stress and/or apoptosis via AMPK/Sirt1 activation may serve as potential therapeutics to reduce CMEC damage and to treat DCM.

Several compounds have been studied for their cardioprotective effects, such as melatonin [17], resveratrol [18]. Melatonin is a pineal gland-secreted amine hormone that regulates sleep cycle and thus is clinically employed to treat short-term insomnia [17]. Given its widely believed free radical scavenging ability [19], we previously reported that melatonin improved HG-induced damage via activating AMPK/Sirt1 signaling in a CMEC model [20]. In contrast to melatonin, resveratrol (RSV) is a natural polyphenol identified in a variety of plants including berries, peanuts, and grapes [21]. Multiple studies have suggested RSV with strong anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-senescence, and cardioprotective properties [18] and potential benefits against DCM [22]. In a neonatal rat cardiomyocyte model, RSV mitigated HG-evoked oxidative stress and apoptosis through AMPK activation [23]. In a DCM rat model, RSV alleviated oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction via modulating Sirt1 to improve DCM [22]. Nevertheless, these investigations are limited in providing direct evidence to elucidate the effects of RSV on CMEC. Although using a CMEC model, RSV was reported to counteract HG-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage [24], the underlying mechanism was not studied.

Therefore, the present study aims to confirm the cardioprotective effects of RSV on CMEC and if AMPK/Sirt1 signaling is associated in how RSV potentially protect against DCM. This study will provide new evidence to strengthen the effectiveness of RSV in DCM.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. CMECs isolation, culture, and high glucose model development

All animal experiments were performed at Shantou University Medical College. All animals used in this study were treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care of Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication no. 86-23, revised 1996). The present study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shantou University Medical College (SUMC2019292). Neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats (1–3 days old) were used and CMECs were isolated from either sex as previously described [25]. CMECs were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, Gibco, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, CA, USA) and endothelial cell growth supplement (15 mg/L, Millipore, MA, USA) in an atmosphere of 95% humidified air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. CMECs were cultured for 3–6 passages before used for any experiments. To develop a high glucose (HG) model that excludes potential interference from osmotic pressure, CMECs were first subjected to either 5.5 mM glucose (normal glucose, NG) without or with 27.5 mM mannitol (isosmotic control; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, CA, USA), or 33 mM glucose (HG; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, CA, USA) without or with 2 μM resveratrol (RSV, CAS 501360; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, CA, USA) for 48 h. In contrast to normal condition where CMEC was cultured using 10% FBS, the HG model in the current study was developed and 2% FBS was selected as the optimal percentage [26]. Media was replaced every 24 h for each group to maintain glucose level, respectively. After treatment, cells were further determined for level of oxidative stress or apoptosis.

2.2. Determination of oxidative stress

To determine intracellular ROS level, CMECs were rinsed thrice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and trypsinized. After centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded and CMECs were resuspended in 1 mL serum-free DMEM containing a 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein acetyl acetate probe (DCFH-DA, 5 μM; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in the dark for 20 min. Subsequently, CMECs were washed thrice with ice-cold PBS and the ROS levels were measured with a BD Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, CA, USA) as previously described [27]. To determine MDA concentration and SOD Activity, CMECs were rinsed thrice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (no. P0013B, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The lysis solution was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration were determined using a commercial kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.3. Flow cytometry

To determine the level of early-stage apoptosis, CMECs were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS. After trypsinization, CMECs were washed twice with PBS and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Subsequently, cells were resuspended in 100 μL Annexin V binding buffer (Dojindo Laboratories, Shanghai, China) containing 5 μL Annexin V-FITC plus 5 μL propidium iodide (PI), before incubation at room temperature (RT) in the dark for 15 min. After resuspending in 400 μL Annexin V binding buffer, the samples were immediately measured by flow cytometry (Accuri™ C6, BD Biosciences, CA, USA).

2.4. TUNEL assay

To determine the level of late-stage apoptosis, CMECs grown on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 30 min. By using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP-nick end labeling (TUNEL) detection kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer's instruction, the images of TUNEL-positive/4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained cells were observed using a confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.5. Western blot analysis

The expression of the apoptosis-related proteins (Bcl-2 and Bax) and AMPK/Sirt1 were determined using Western blotting. Briefly, equivalent protein samples from each group were separated using 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked using 5% skim milk at RT for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies against p-AMPKα (Thr172) (no. 2535, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technologies, MA, USA), Bcl-2 (no. 26539-1-AP, 1:2000, Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei, China), AMPKα (no. 2603, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technologies, MA, USA), Bax (no. 2772, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technologies, MA, USA), Sirt1 (no. 9475, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technologies, MA, USA), and β-actin (no. TA09, 1:2000, ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) at 4 °C overnight. The membranes were rinsed thrice with Tris-buffer saline with 0.25% Tween-20 (v/v) and incubated with a horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (no. BA1054, BA1050, 1:30000, Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, China). The membranes were visualized using a SuperSignal™ West Dura Extended Duration Substrate kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, IL, USA). After exposing the X-ray film, the density of the bands was standardized over β-actin and calculated using a Gel-Pro Image Analysis software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

2.6. AMPK inhibition and Sirt1 silencing

To further confirm the potential effects of RSV on AMPK/Sirt1 regulation, AMPK inhibition and Sirt1 silencing were performed by supplementing the AMPK inhibitor compound C (CC, 1 μM; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) [28] and small-interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection, respectively. The sequences of Sirt1 and negative control (NC) siRNAs (Bio-tend Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) were as follows: Sirt1, 5′-GAU CCU CGA ACA AUU CUU AdTdT-3’ (sense) and 5′-UAA GAA UUG UUC GAG GUC dTdT-3’ (antisense); NC, 5′- CGU UUG UUC GCU UCC UGA GTT-3’ (sense) and 5′- CUC AGG AAG CGA ACA AAC GTG-3’ (antisense). 5 μL Sirt1 or NC (20 μM) siRNA was inoculated into 250 μL Opti-MEM medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Subsequently, siRNA was mixed with 250 μL Opti-MEM medium containing 5 μL LipofectamineTM 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and settled at RT for 20 min. Once CMEC reaches 70–80% confluence in 6-well plates, cells were treated with the mixture supplemented with 1500 μL Opti-MEM medium per well and incubated under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 5 h.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All experiments in this study were conducted in triplicates. Data are represented as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance followed by a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons test using a GraphPad Prism software (version 8.3.0; San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. RSV reduces HG-evoked oxidative stress in CMEC

To investigate the effects of RSV on oxidative damage in HG-treated CMECs, ROS level, MDA concentration, and SOD activity were determined. For ROS production, the mannitol group was not statistically different in contrast to the NG group, whereas the HG group showed a significant elevation (Fig. 1A–B). This elevation in ROS production was significantly reduced in the NG + RSV group (Fig. 1A–B). For MDA concentration, the HG and HG + RSV groups mirrored effects on ROS production (Fig. 1C). For SOD activity, while the mannitol group was not significantly different to the NG group, the HG group showed a significant decrease (Fig. 1D). This decrease was significantly reversed by the HG + RSV group (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Resveratrol (RSV) reduces oxidative stress in high glucose (HG)-cultured cardiac micro-vascular endothelial cell (CMEC). (A–B) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production examined by flow cytometry. (C–D) malondialdehyde (MDA) contents and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity detected using commercial kits. All data were represented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the NG group, #P < 0.05 vs. the HG group. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

3.2. RSV suppresses HG-evoked apoptosis in CMEC

While no significant difference was observed between the NG and mannitol groups in change in fraction of apoptotic cells, the HG group markedly increased the fraction of apoptotic cells (Fig. 2A–B). This increase was significantly lowered in the HG + RSV group (Fig. 2A–B). To further confirm the anti-apoptotic effects of RSV, expression of Bcl-2 and Bax proteins was measured and TUNEL staining was performed. Similarly, the mannitol group did not exhibit any significant change in either Bcl-2 or Bax expression, or number of TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 2C–E). In contrast, the HG group significantly suppressed Bcl-2 expression, increased Bax expression and number of TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 2C–E). These changes were significantly blunted in the HG + RSV group (Fig. 2C–E).

Fig. 2.

RSV suppresses HG-evoked apoptosis in CMEC. (A–B) Apoptosis examined by flow cytometry. (C–D) level of Bcl-2 and Bax expression analyzed by western blotting. (E) TUNEL/DAPI staining. All data were represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the NG group, #P < 0.05 vs. the HG group.

3.3. RSV activates AMPK/Sirt1 signaling in HG-mediated CMECs

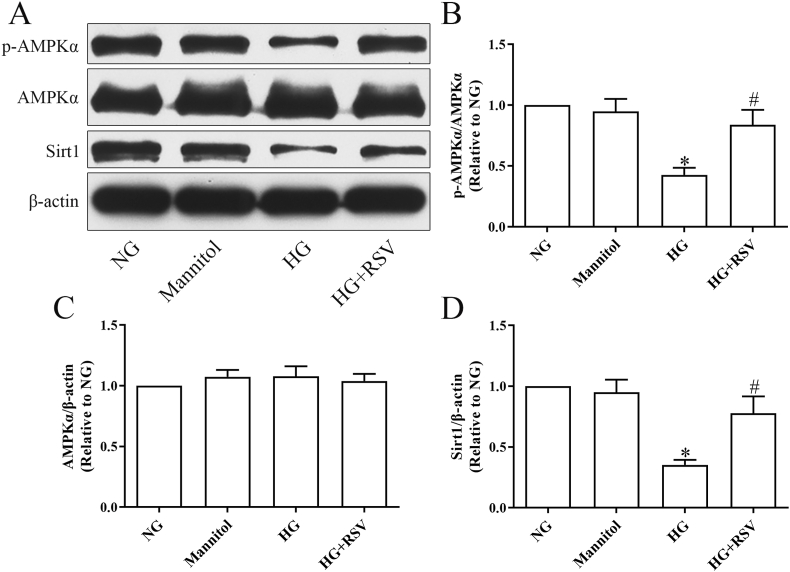

We further investigated if RSV was associated with regulatory influences on AMPK and/or Sirt1 signaling. In contrast to the NG group, the mannitol group did not exhibited any change in the expression of phosphorylated AMPKα (p-AMPKα), total AMPKα or Sirt1 (Fig. 3). While the HG group did not affect total AMPKα expression (Fig. 3A and C), significantly downregulated p-AMPKα and Sirt1 expression were observed (Fig. 3A, B and D). The reduced proportion of AMPKα phosphorylation (p-AMPKα/AMPKα) and reduced level of Sirt1 expression were significantly elevated in the HG + RSV group (Fig. 3A, B and D).

Fig. 3.

RSV activates the AMPK/Sirt1 axis in HG-challenged CMECs. (A–D) Western blot analysis of p-AMPKα (Thr172), AMPKα, Sirt1 expression in CMECs. All values were presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the NG group, #P < 0.05 vs. the HG group.

Considering the potential reciprocal activation between AMPK and Sirt1 [29], we employed the AMPK inhibitor compound C [28] and Sirt1 siRNA to further verify if either AMPK or Sirt1 is upstream. For total AMPKα expression, neither negative control siRNA (si-NC), Sirt1 siRNA (si-Sirt1) nor compound C exhibited any significant change (Fig. 4A and C). For p-AMPKα/AMPKα and Sirt1 levels, RSV significantly restored HG-induced downregulation, despite the presence of si-NC (Fig. 4A–B and 4D). RSV-restored p-AMPKα/AMPKα and Sirt1 levels were significantly blunted by compound C (Fig. 4A–B and 4D). In the presence of si-Sirt1, while RSV-restored p-AMPKα/AMPKα level was not significantly affected (Fig. 4A–B), RSV-restored Sirt1 level was significantly blunted (Fig. 4A and D).

Fig. 4.

Effects of compound C or Sirt1 silencing on RSV-mediated AMPK/Sirt1 signaling. (A) Western blot and (B–D) statistical analysis of p-AMPKα (Thr172), AMPKα, Sirt1 expression in CMECs. All data were presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the NG group, #P < 0.05 vs. the HG group, $P < 0.05 vs. the HG + RSV group, &P < 0.05 vs. the HG + si-NC group, †P < 0.05 vs. HG + si-NC + RSV group. CC, compound C.

3.4. RSV mitigates HG-induced oxidative damage by enhancing AMPK/Sirt1 activation in CMEC

We further verified if RSV exerted its antioxidative effects via promoting AMPK/Sirt1 activity. In contrast to the NG control, HG significantly elevated ROS generation (Fig. 5A–B) and MDA concentration (Fig. 5C), while lowered SOD level (Fig. 5D), despite the presence of si-NC (Fig. 5B–D). RSV significantly counteracted HG-induced elevation in ROS (Fig. 5A–B) and MDA (Fig. 5C) and SOD decrease (Fig. 5D). These effects of RSV on ROS and MDA decrease, and SOD upregulation were further blunted by the presence of either compound C or si-Sirt1 (Fig. 5A–D).

Fig. 5.

RSV Mitigates HG-Induced Oxidative Damage by Enhancing AMPK/Sirt1 Activation in CMEC. (A–B) ROS production examined by flow cytometry. (C–D) MDA contents and SOD activity. All data were represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the NG group, #P < 0.05 vs. the HG group, $P < 0.05 vs. the HG + RSV group, &P < 0.05 vs. the HG + si-NC group, †P < 0.05 vs. the HG + si-NC + RSV group. CC, compound C. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

3.5. RSV alleviates HG-induced CMEC apoptosis by enhancing AMPK/Sirt1 axis

Next, we assessed whether the anti-apoptotic effects of RSV were associated with AMPK/Sirt1 signaling. In contrast to the NG control, HG significantly elevated apoptotic cell percentage (Fig. 6A –B), while lowered Bcl-2 expression (Fig. 6C), despite the presence of si-NC (Fig. 6B–C). RSV significantly counteracted HG-induced elevation in apoptotic cell percentage (Fig. 6A–B) and Bcl-2 downregulation (Fig. 6C). These effects of RSV on reducing apoptotic cell percentage, and Bcl-2 upregulation were further blunted by the presence of either compound C or si-Sirt1 (Fig. 6A–C).

Fig. 6.

RSV Alleviates HG-Induced apoptosis by Enhancing AMPK/Sirt1 Activation in CMEC. (A–B) CMECs apoptosis examined by flow cytometry. (C) Representative western blot images for Bcl-2 expression in CMEC. All values were presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the NG group, #P < 0.05 vs. the HG group, $P < 0.05 vs. the HG + RSV group, &P < 0.05 vs. the HG + si-NC group, †P < 0.05 vs. HG + si-NC + RSV group. CC, compound C.

4. Discussion

Impaired CMECs and dysfunction of cardiomyocytes are the main manifestations of DCM [30]. Previous studies on the protective effects of RSV against DCM in rats mostly focused on streptozotocin-induced DCM model, while in vitro studies mostly focused on HG-induced primary rat cardiomyocyte or H9c2 cell model [22,23]. One of the major differences of CMEC in contrast to cardiomyocyte is that CMECs barely express L-type calcium channels (unpublished data). In addition, cleaved caspase-3 expression, one of the apoptosis biomarkers, could hardly be detected in CMEC under an array of stress conditions (such as hypoxia/reoxygenation, HG), and compared to large vascular endothelial cells (unpublished observation). In fact, during the development of DCM, CMEC damage precedes cardiomyocyte damage as it can affect cardiomyocyte function and subsequently impair cardiac function [7,30]. Although a plethora of studies demonstrated the protective effect of RSV against HG-induced injury in cardiomyocytes or human umbilical vein endothelial cells [23,28], none reported such protective effects of RSV in rat primary CMEC. Given the unique characteristics suggested by our findings, we demonstrated for the first time that RSV attenuates HG-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in primary rat CMEC.

Oxidative stress refers to a state of imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and the endogenous antioxidant defense system [31]. It plays an extremely important role in CMEC injury [32]. Compared to physiological level of ROS that can maintain cell function, accumulation of ROS is largely associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced activity of endogenous antioxidant defense system under stress conditions such as hyperglycemia and hypoxia [33,34]. It is widely acknowledged that hyperglycemia induces mitochondrial dysfunction and lead to oxidative damage in CMEC [7]. Consistently, our data suggested increased ROS and MDA levels in CMECs under HG condition. As a member of the endogenous antioxidant defense system, SOD scavenges free radicals, and the decrease of its activity is an important sign of oxidative damage [35]. This decrease in SOD activity was also observed in the current study on CMEC. In addition, our study reported that RSV reversed the observed oxidative stress in CMEC. This further confirms the potent antioxidant properties of RSV that is also reported by accumulating research on diabetes and diabetic complications [22,36]. Although the change in ROS levels were determined by DCFH-DA probe, whether RSV could attenuate HG-induced mitochondrial ROS generation remains unknown. Hence, the role of RSV on mitochondrial ROS generation under HG conditions needs further exploration by probes such as MitoSOX.

Accumulation of ROS induces oxidative damage, triggers intrinsic death pathways, and subsequently lead to apoptosis [37]. Members of the Bcl-2 family proteins play an important role in intrinsic apoptotic pathway and are important factors that regulate the release of cytochrome C from mitochondria. Cytochrome C could trigger the activation of caspase cascade, thus resulting in cell apoptosis. When activated, free pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 subfamily proteins (Bax, Bid and Bak) elicit mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP). Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) bind to pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins and prevent their conformational change and dimerization [38]. Hence, Bax could change mitochondrial permeability and promote the release of cytochrome C from mitochondria. Bcl-2 has stable mitochondrial membrane function and can block mitochondrial release of cytochrome C, thus inhibiting the activation of caspases and the apoptotic processes of caspase cascade. Therefore, pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins are considered as a crucial checkpoint for the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. This was replicated by our study in which HG induces apoptosis in CMEC by lowering anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 expression, elevating pro-apoptotic protein Bax expression and apoptotic cell percentage. It was reported that the classical ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine attenuated HG-induced apoptosis in retinal capillary cells [39], which suggested that inhibition of oxidative stress could reduce the occurrence of apoptosis. Therefore, it is not surprising that RSV may reduce HG-evoked apoptosis by inhibiting oxidative stress. Although our data demonstrated that RSV promoted Bcl-2, reduced Bax expression and apoptotic cell percentage, the current study consistently reveals that RSV mitigates HG-induced apoptosis. This confirms the anti-apoptotic nature of RSV in CMEC under HG conditions.

RSV has been repeatedly demonstrated for its protection against a variety of disease including diabetes and diabetic complications [22,40]. This is reported to act upon one of the shared underlying mechanisms, AMPK and Sirt1 activation. Consistently, our data suggest decreased AMPK and Sirt1 levels that are reversed by RSV in CMEC under HG conditions. On the one hand, Sirt1 overexpression is known to increase the expression of liver kinase B-1 (LKB1), an upstream molecule of AMPK, thereby enhancing AMPK activity [41]. On the other hand, AMPK can also promote Sirt1 expression by increasing NAD+ level [42]. Given this mutual induction, our employment of the AMPK inhibitor compound C inhibited RSV-mediated Sirt1 upregulation, and AMPK expression was not affected by silencing Sirt1 in CMEC. This indicates that AMPK is an upstream signaling molecule of Sirt1. In addition, our data demonstrated that the use of compound C or Sirt1 silencing blunted RSV-mediated protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis in CMEC. This further illustrates that RSV acts as an antioxidative and anti-apoptotic agent against HG via AMPK/Sirt1 activation in CMEC.

Despite our discovery that RSV activates AMPK/Sirt1 in CMEC, the downstream targets of Sirt1 and signaling that eventually lead to RSV-protected oxidative stress and apoptosis remain to be investigated. Sirt1 can alleviate oxidative stress by deacetylating a variety of proteins and protect against mitochondrial dysfunction by regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) [43]. This is also consistent with our previous work in which Sirt1 overexpression promoted the deacetylation of Forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1) as well as SOD overexpression to antagonize oxidative stress [44]. Like PGC-1α and FoxO1, nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is widely known as another downstream target of Sirt1. Nrf2 binds to antioxidant responsive elements in the promoter regions of target genes to regulate the expression of many antioxidant and detoxifying proteins, including glutathione peroxidase, glutathione S-transferase, thioredoxin reductase, catalase, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone-1 (NQO1) and SOD, to further reduce oxidative damage [45,46]. In a study using diabetic rats, Sirt1/Nrf2 activation to reduce oxidative stress was reported to improve kidney function [47]. RSV may mediate downstream targets by regulating the AMPK/Sirt1 signaling axis, such as PGC-1α, FoxO1 and Nrf2 to improve mitochondrial function and enhance ROS scavenging, thus inhibiting intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Nevertheless, whether PGC-1α, FoxO1, Nrf2 or other potential downstream targets are involved in RSV-mediated antioxidant or anti-apoptotic effects will be investigated in the future. In addition, further studies using in vivo models are needed to replicate data of the current research and to promote the potential of RSV against DCM.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we firstly investigated if RSV could alleviate oxidative stress and apoptosis in rat CMEC and investigated the associated underlying mechanisms. Our data exhibited that HG elevated ROS production, MDA contents, apoptotic cell percentage and Bax expression, decreased SOD activity and Bcl-2 expression in CMEC, which were reversed by RSV administration. Additionally, RSV showed antioxidative and anti-apoptotic effects in CMEC through AMPK/Sirt1 activation. These results provide new evidence and strengthen the robustness of RSV as a potential cardioprotective agent to help treating DCM.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jinyu Li, Zikai Feng and Bin Wang: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Jinyu Li and Bin Wang: Project administration. Binger Lu, Xinzhe Fang and Bin Wang: Performed experiments. Jinyu Li and Danmei Huang: Software and data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81703508) and Medical Science Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (A2022398).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2023.101444.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Paolillo S., Marsico F., Prastaro M., et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: definition, diagnosis, and therapeutic implications. Heart Fail. Clin. 2019;15(3):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murtaza G., Virk H.U.H., Khalid M., et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy - a comprehensive updated review. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019;62(4):315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dillmann W.H. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2019;124(8):1160–1162. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.118.314665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou H., Hu S., Jin Q., et al. Mff-dependent mitochondrial fission contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiac microvasculature ischemia/reperfusion injury via induction of mROS-mediated cardiolipin oxidation and HK2/VDAC1 disassociation-involved mPTP opening. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3) doi: 10.1161/jaha.116.005328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell D.J., Somaratne J.B., Jenkins A.J., et al. Impact of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome on myocardial structure and microvasculature of men with coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2011;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aneja A., Tang W.H., Bansilal S., Garcia M.J., Farkouh M.E. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: insights into pathogenesis, diagnostic challenges, and therapeutic options. Am. J. Med. 2008;121(9):748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou H., Wang S., Zhu P., et al. Empagliflozin rescues diabetic myocardial microvascular injury via AMPK-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial fission. Redox Biol. 2018;15:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juni R.P., Kuster D.W.D., Goebel M., et al. Cardiac microvascular endothelial enhancement of cardiomyocyte function is impaired by inflammation and restored by empagliflozin, JACC. Basic to translational science. 2019;4(5):575–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diao L., Bai L., Jiang X., Li J., Zhang Q. Long-chain noncoding RNA GAS5 mediates oxidative stress in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells injury. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234(10):17649–17662. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu D., Zhang X., Wang F., et al. Irisin rescues diabetic cardiac microvascular injury via ERK1/2/Nrf2/HO-1 mediated inhibition of oxidative stress. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022;183 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maruhashi T., Higashi Y. Pathophysiological association between diabetes mellitus and endothelial dysfunction. Antioxidants. 2021;10(8) doi: 10.3390/antiox10081306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng C., Ma J., Gao X., et al. High glucose induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells are regulated by FoxO3a. PLoS One. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang S., Li T., Ji T., et al. AMPK: potential therapeutic target for ischemic stroke. Theranostics. 2018;8(16):4535–4551. doi: 10.7150/thno.25674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rada P., Pardo V., Mobasher M.A., et al. SIRT1 controls acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by modulating inflammation and oxidative stress. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018;28(13):1187–1208. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D., Yin Y., Wang S., et al. FGF1(ΔHBS) prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy by maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and reducing oxidative stress via AMPK/Nur77 suppression. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2021;6(1):133. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00542-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue T., Inoguchi T., Sonoda N., et al. GLP-1 analog liraglutide protects against cardiac steatosis, oxidative stress and apoptosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Atherosclerosis. 2015;240(1):250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Y.J., Zhong C.B., Wu W. Cardioprotective effects of melatonin: focusing on its roles against diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2020;128 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia N., Daiber A., Förstermann U., Li H. Antioxidant effects of resveratrol in the cardiovascular system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017;174(12):1633–1646. doi: 10.1111/bph.13492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Z., Xiang Q., Wang J., Zhang Y. The potential role of melatonin in retarding intervertebral disc ageing and degeneration: a systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021;70 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang B., Li J., Bao M., et al. Melatonin attenuates diabetic myocardial microvascular injury through activating the AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/8882130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang X.T., Li X., Xie M.L., et al. Resveratrol: review on its discovery, anti-leukemia effects and pharmacokinetics. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019;306:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang W.J., Wang C.J., He Y., et al. Resveratrol alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats by improving mitochondrial function through PGC-1α deacetylation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018;39(1):59–73. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo S., Yao Q., Ke Z., et al. Resveratrol attenuates high glucose-induced oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis through AMPK. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015;412:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joshi M.S., Williams D., Horlock D., et al. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in hyperglycaemia-induced coronary microvascular dysfunction: protective role of resveratrol. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2015;12(3):208–216. doi: 10.1177/1479164114565629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Y., Shi G., Zheng J., et al. The protective effects of Egr-1 antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotide on cardiac microvascular endothelial injury induced by hypoxia-reoxygenation. Biochemistry and cell biology = Biochimie et biologie cellulaire. 2010;88(4):687–695. doi: 10.1139/o10-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding H., Aljofan M., Triggle C.R. Oxidative stress and increased eNOS and NADPH oxidase expression in mouse microvessel endothelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;212(3):682–689. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu S., Zhang Y., Zhong S., et al. N-n-butyl haloperidol iodide protects against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells by regulating the ROS/MAPK/Egr-1 pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;7:520. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou D.Y., Su Y., Gao P., et al. Resveratrol ameliorates high glucose-induced oxidative stress injury in human umbilical vein endothelial cells by activating AMPK. Life Sci. 2015;136:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruderman N.B., Xu X.J., Nelson L., et al. AMPK and SIRT1: a long-standing partnership? Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2010;298(4):E751–E760. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00745.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu J., Wang S., Xiong Z., et al. Exosomal Mst1 transfer from cardiac microvascular endothelial cells to cardiomyocytes deteriorates diabetic cardiomyopathy, Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease. 2018;1864(11):3639–3649. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaganjac M., Milkovic L., Zarkovic N., Zarkovic K. Oxidative stress and regeneration. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022;181:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou J., Yuan Y., Chen P., et al. Pathological roles of oxidative stress in cardiac microvascular injury. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang Q., Yang C. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 2020;37 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chazelas P., Steichen C., Favreau F., et al. Oxidative stress evaluation in ischemia reperfusion models: characteristics, limits and perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(5) doi: 10.3390/ijms22052366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi H., Gu L., Xu D., et al. β-Hydroxybutyrate inhibits cardiac microvascular collagen 4 accumulation by attenuating oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and high glucose treated cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021;899 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang D.D., Shi G., Jiang Y., Yao C., Zhu C. A review on the potential of Resveratrol in prevention and therapy of diabetes and diabetic complications. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2020;125 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Circu M.L., Aw T.Y. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48(6):749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li K., van Delft M.F., Dewson G. Too much death can kill you: inhibiting intrinsic apoptosis to treat disease. EMBO J. 2021;40(14) doi: 10.15252/embj.2020107341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J., Yu S., Ying J., Shi T., Wang P. Resveratrol prevents ROS-induced apoptosis in high glucose-treated retinal capillary endothelial cells via the activation of AMPK/Sirt1/PGC-1α pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/7584691. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song Y.J., Zhong C.B., Wu W. Resveratrol and diabetic cardiomyopathy: focusing on the protective signaling mechanisms. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/7051845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng Z., Chen H., Li J., et al. Sirtuin 1-mediated cellular metabolic memory of high glucose via the LKB1/AMPK/ROS pathway and therapeutic effects of metformin. Diabetes. 2012;61(1):217–228. doi: 10.2337/db11-0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cantó C., Gerhart-Hines Z., Feige J.N., et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458(7241):1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y., Zhang J., Zheng Y., et al. NAD(+) improves cognitive function and reduces neuroinflammation by ameliorating mitochondrial damage and decreasing ROS production in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion models through Sirt1/PGC-1α pathway. J. Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02250-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bao M., Huang W., Zhao Y., et al. Verapamil alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating oxidative stress via activation of SIRT1. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.822640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang T.C. Nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and mitochondrial dynamics/mitophagy in neurological diseases. Antioxidants. 2020;9(7) doi: 10.3390/antiox9070617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grismaldo Rodríguez A., Zamudio Rodríguez J.A., Mendieta C.V., et al. Effect of platelet-derived growth factor C on mitochondrial oxidative stress induced by high d-glucose in human aortic endothelial cells. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(5) doi: 10.3390/ph15050639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang G., Li Q., Peng J., et al. Fucoxanthin regulates Nrf2 signaling to decrease oxidative stress and improves renal fibrosis depending on Sirt1 in HG-induced GMCs and STZ-induced diabetic rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021;913 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.