Abstract

The global groundwater crisis is a perplexing issue, and for its resolution, it is of the utmost importance for delineating groundwater potential zones. This research aims to create a precise groundwater potential map for Bangladesh's Jashore district by combining geospatial approach and an analytical hierarchy process. Fourteen parameters, namely, lineament density, drainage density, land use and land cover, slope, curvature, topographic position index, topographic wetness index, rainfall, geology, roughness, fractional impervious surface, topsoil texture, soil permeability, and general soil types, were considered for the study after an extensive literature review. The weights of these parameters were determined using an analytical hierarchy process, and the scores of each sub-parameter were assigned based on published literature. The final groundwater potential map was then generated using the weighted overlay analysis tool in ArcGIS 10.3 and categorized into five classes. The analysis reveals that very high, high, moderate, low, and very low groundwater potential zones cover 3.96 km2 (0.16%), 444.75 km2 (17.72%), 1615.51 km2 (64.37%), 441.79 km2 (17.60%), and 3.59 km2 (0.14%) of the study area, respectively. The map removal sensitivity analysis shows that geology is the most significant element in groundwater potential zoning, followed by land use and land cover (LULC), slope, and topsoil texture as moderately sensitive elements. Since the groundwater potentiality zones of the study region are clearly delineated, this research may be valuable for implementing an appropriate water resource management strategy.

Keywords: Groundwater potential zone, Analytical hierarchy process, Geographic information system, Remote sensing, Bangladesh

1. Introduction

Groundwater is considered one of the most valuable elements of the natural hydrological process, as it is stored beneath the water table in the voids of rock and soil. About 30% of the fresh water on Earth comes from it [9], and it has always been a more desirable resource due to its reliable chemical composition, fewer pathogens, and low turbidity in contrast to surface water [1,53,87]. Due to its easy and cheap accessibility, it acts as a key element in domestic, agricultural, industrial, and other development activities [12,68]. However, the growing desire for water to fulfill human needs and for development has put tremendous strain on this finite freshwater availability [8]. The amount and reliability of groundwater are severely impacted by urbanization, industrialization, and deforestation (T [17]. It is estimated that 36%, 42%, and 27%, respectively, of the world's groundwater is extracted for home, farming, and manufacturing uses [84]. According to research, groundwater resources constitute more than 70% of the water supply and are increasingly being overused, causing a 545 km3/year depletion [88]. The depletion of groundwater has proceeded at a rate that prevents the water table from recouping its losses. In comparison to the pace of extraction, the recharge process is insufficient [19]. Thus, assessing the availability and ambient quality of groundwater is critical for its long-term use [14].

The presence of groundwater in a certain region is determined by a number of parameters connected to the hydrogeological and hydro-meteorological environment [14,35,70]. According to several studies, geology, soil type, geomorphology, porosity, slope, topographic position index, topographic wetness index, roughness, curvature, land use/land cover (LULC), rainfall, drainage density, lineament density, distance from the river, etc. typically defines groundwater potential zones [8,18,20,21,24,47,63,64,79,80,83]. The availability of groundwater changes considerably across seasons, and river runoff has a significant impact on the recharging process [45]. The most dependable and conventional procedures for identifying spots, aquifer thickness, and other underground details are stratigraphic analysis and test drilling; nevertheless, these procedures are costly, lengthy, and require specialized labor [19,75,76]. Geographic Information System (GIS) and Remote Sensing (RS) techniques, on the other hand, have opened up a new platform for analyzing a vast quantity of geospatial data in order to conduct effective and efficient groundwater research while also saving time and money [81,87]. Several researchers from all over the globe have combined GIS and RS with multi-criteria decision-making analysis (MCDMA) for identifying possible groundwater zones [24]. MCDMA is a process for evaluating a set of criteria for a given goal, the findings of which are used to make judgments [78]. It includes various techniques such as fuzzy set analysis, analytical hierarchy process (AHP), compromise programming (CP), PROMETHEE (I, II, and V), ELECTRE (I, II, III, and IV), multi-attribute utility theory (MAUT), MACBETH, weighted summation, EXPROM, and TOPSIS [32]. One of these strategies that stands out as a great tool for dealing with complex problem in groundwater research is AHP, which was developed by Tomas Saaty in the year 1980. Furthermore, it is a useful tool to assess the reliability of results, therefore eliminating bias in the judgment process [8]. Various approaches like frequency ratio [5,22,24,31,52,61,71], logistic regression model techniques [61,67,77], random forest model [51,62,77], artificial neural network [54,62], evidential belief function [57] and support vector machine [77] were also used successfully to identify possible groundwater recharge zones.

Bangladesh, a low-lying coastal and agriculturally dependent country, is dealing with significant issues such as decreased freshwater accessibility in various regions, which has harmed the decent quality of life of an expanding population and may lead to internal strife in the future [37]. Drought, like other natural catastrophes such as cyclones and floods, is acute in Jashore district, where the rainy season is delayed [40]. The area's agricultural production is largely dependent on groundwater irrigation, and a considerable increase in irrigated agriculture over the last decade has led to significant groundwater demand. Furthermore, the continually changing climatic situation, including the unpredictable intensity and frequency of precipitation annually, makes water resource management challenging. Thus, appraisal of local water resources is essential for the sustainability of livelihoods over the long run. However, there hasn't been much investigation into the potential for groundwater in the study region using GIS and RS techniques. Hence, the current research seeks to create a precise groundwater potential map for Jashore district of Bangladesh using a systematic and rigorous GIS-based analytical hierarchy process (AHP) method for improved devolvement and maintenance of this invaluable asset. A larger set of variables (fourteen variables) have been used for this purpose, including lineament density, drainage density, land use land cover, slope, curvature, topographic position index, topographic wetness index, rainfall, geology, roughness, fractional impervious surface, topsoil texture, soil permeability, and general soil types, all of which either directly or indirectly affect a region's potential groundwater yield. The scores of each sub-parameter were allocated based on published literature, and the weights of these parameters were established utilizing an analytical hierarchy method. The final groundwater potential map was then produced using the weighted overlay analysis tool in ArcGIS 10.3, and it was separated into five categories.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study area

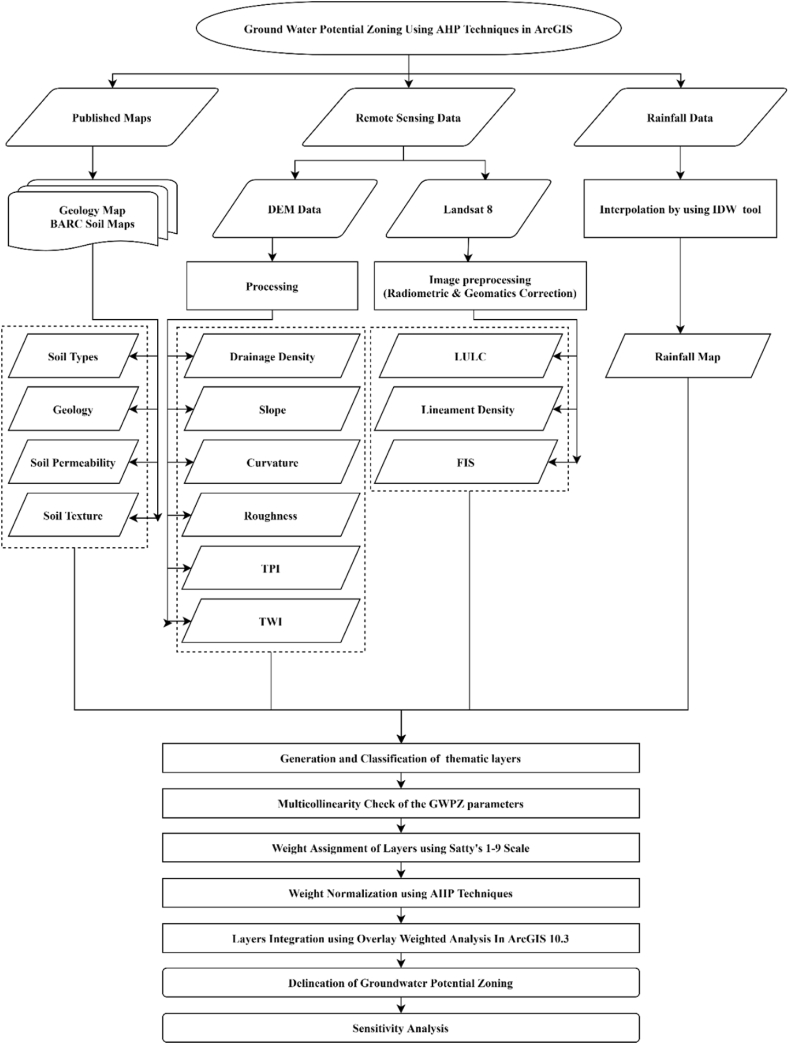

Jashore District (Fig. 1), formerly known by the name of Jessore, is located in the southwestern region of Bangladesh and lies between 21.45° and 23.34° north latitudes and between 89.15° and 89.55°’ east longitudes, comprising an area of about 2606.98 km2 [6]. It is bounded on the west by India, on the south by the district of Khulna and Satkhira, on the east by Khulna and Narail, and to the north by Jhenaidah and Magura district. The area exhibits high precipitation throughout the rainy season, with an average annual rainfall of around 1537 mm. The rainy season in Jashore is hot, humid, and cloudy, whereas the summer season is usually mild and clear. In the winter and summer, the average minimum and maximum temperatures are around 15.3 °C and 38.3 °C, respectively. The research area's surface geology consists of Holocene-age deltaic deposits. The sediments of the delta are the sediments placed on the active delta, south of the river Ganges. The majority of the research area is underlain by deltaic silt. In the northern portion of the research region, there is deltaic sand, marsh clay, and peat in the central-east portion. The population of the district is approximately 2 million and 75 thousand, of which over half are involved in agriculture and its related professions. Indeed, for farming and habitats, water is quite vital. The Bhairab and Kopotakkho are the main rivers flowing through this region. In addition, there are several minor rivers such as Hari, Tekah, Sree, Harihar, Aparbhadra, Buribhadra, Betna, Chitra and Mukteshwari [3]. This river water is used by the residents for drinking, agriculture, household, and industrial applications, along with groundwater. The overall methodological flowchart is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Map showing study area.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the methodology.

2.2. Selection of the parameters

Previous groundwater-related research has shown that physiographic factors have a strong relationship with groundwater potential [59,90]. The groundwater level fluctuates depending on the geology, LULC, slope, topsoil texture, drainage density, general soil types, lineament density, soil permeability, rainfall, roughness, curvature, etc. The majority of scientific studies used criteria such as lineament density, drainage density, LULC, slope, rainfall, geology, soil texture, soil types, and so on to identify groundwater potential areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Review of the criteria used in prior research for delineating Ground Water Potential Zones.

| Reference | LD | DD | LULC | Sl | Rf | Ge | TT | GST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [34] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [50] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [2] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [41] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [11] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [44] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [29] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [89] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [33] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [66] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [30] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [72] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [58] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [65] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [8] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [15] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [82] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [7] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [13] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [17] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [43] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [4] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [10] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [88] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

LD = Lineament Density; DD = Drainage Density; LULC = Land Use Land Cover; Sl = Slope; Rf = Rainfall; Ge = Geology; TT = Topsoil Texture; GST = General Soil Types.

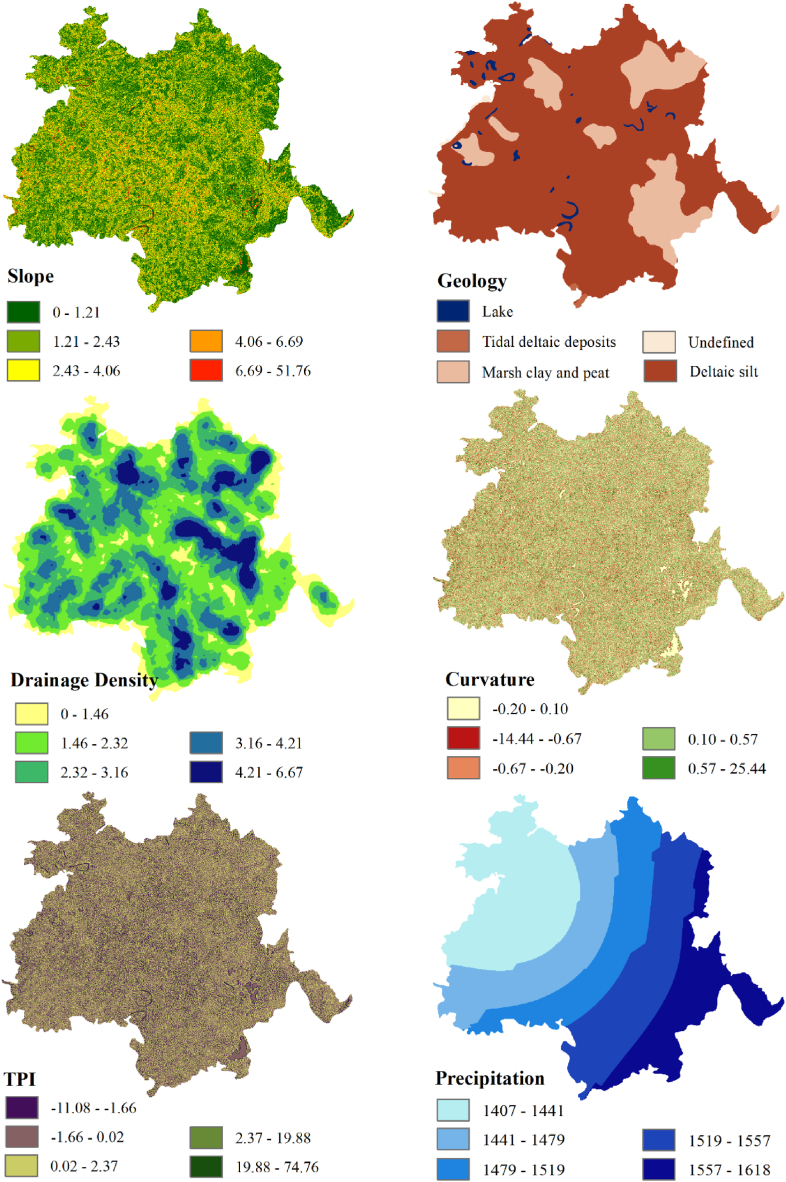

Additionally, some studies also indicate that factors such as curvature, topographic position index (TPI), topographic wetness index (TWI), soil permeability, roughness, fractional impervious surface (FIS), etc. also have a vital influence on the fluctuational level of groundwater [8,76]. The prospective groundwater zone has been defined by the cumulative influence of these factors [89]. There is a shift in the level of groundwater due to these factors. Thus, criteria such as lineament density, drainage density, LULC, slope, curvature, TPI, TWI, rainfall, geology, roughness, FIS, topsoil texture, soil permeability, and general soil types were selected for identifying GWPZ through the application of weighted overlay analysis. The spatial distribution of parameters aree shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5.

Fig. 3.

Spatial variations of slope, geology, drainage density, curvature, TPI, and precipitation of the study area.

Fig. 4.

Spatial variations of roughness, FIS, soil texture, LULC, TWI, and lineament density of the study area.

Fig. 5.

Spatial variations of soil permeability, and soil types of the study area.

2.3. Used dataset and generation of the thematic layers

The extraction of thematic layers, which were then utilized for weighted overlay analysis, included the use of satellite images, rainfall, soil data, previously published geology maps, reports, and data from many sources (Table 2).

Table 2.

Specifics of the data used to derive thematic layers for the GWPZ.

| Data Type | Data detail | Time/Duration | Sources | File | Layer extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall | Annual Precipitation (mm) | 2010–2020 | Climatic Research Unit (CRU) Data (Available at https://sites.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/) | .NetCDF | Annual Rainfall |

| Satellite Imagery | Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) Level-1T images with 30 m spatial resolution | Acquired on 2021-03-17 | NASA LP DAAC – Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (Available at https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) | .Geotiff | LULC FIS Lineament Density |

| Copernicus GLO-30 Digital Elevation Model with 30 m spatial resolution | Acquired on 2015 | European Space Agency, Sinergise (Available at https://opentopography.org/) | .Geotiff | Drainage Slope TWI TPI Curvature Roughness | |

| Geological Map | Geological Map of Bangladesh published by Geological Survey of Bangladesh in Scale of 1:1,000,000 | Acquired on 1990 & compiled in 2001 | United States Geological Survey (USGS) Publications Warehouse (Available at https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/) | .Geotiff | Geology |

| Soil Data | Land Resources Appraisal of Bangladesh for Agricultural Development, 1988 (BGD/81/035) | Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council (BARC) (Available at http://www.barc.gov.bd/) | ESRI.shp |

|

In ArcGIS 10.3 and QGIS 3.16 environments, thematic maps were developed for comprehending basic information about various groundwater parameters. The published map of the Geological Survey of Bangladesh at a scale of 1:100,000 was digitally converted into the geological map of Jashore using ArcGIS 10.3.

For a period of ten years, the Climate Research Unit (https://sites.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/) collected data on the yearly average rainfall (2010–2020). The online page of the high-resolution grid data sets was then selected for downloading NetCDF-formatted precipitation data. Using the tool “Make NetCDF Raster Layer” in ArcGIS 10.3, the NetCDF rainfall data were converted to a raster layer. The raster layer was then turned into points using “Raster to Point”. Points were then used as input data for interpolation using the “IDW” technique to generate a contour map of annual average rainfall. The precipitation map for the study area was then extracted using the “Extract by Mask” tool.

The slope and curvature maps in ArcGIS 10.3 were created using the spatial analyst tools “Slope” and “Curvature,” respectively, using the Copernicus GLO-30 Digital Elevation Model with a spatial resolution of 30 m. Drainage was also developed using the digital elevation model data. The drainage density map, which shows the length of the drainage per km2, was created after streams were created using “Hydrology Tools” and the “Line Density” tool. The roughness layer was developed by utilizing the Neighborhood tool to produce the mean (FSmean), minimum (FSmin), and maximum (FSmax) focal statistics layer of the DEM, and then Eq [26]. with the support of the Raster Calculator was applied for calculating the roughness.

“TOPMODEL”, a model that enhances watershed hydrological fluxes, was utilized in developing the Topographic Wetness Index (TWI). For the TWI calculation, the following equation was applied:

α = Upslope contributing area; β = Topographic gradient (Slope).

The Topographic position index (TPI) is an algorithm generally utilized for measuring and automating landform gradations on topographical slope positions. The Jenness method was used to calculate the topographic position index.

where, M0 = Elevation of the evaluation model point, Mn = grid elevation, n = total number of neighboring points included in the assessment.

The shape file, which is accessible at the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council (BARC), was used to create the soils map, which displays the research area's topsoil texture, soil permeability, and general soil types.

Pre-processing of Jashore's satellite imagery, including radiometric and other corrections, was performed using the QGIS 3.16 application, which uses a semiautomatic classification plugin (SCP). The LULC map was created using a supervised classification method using Landsat 8 satellite data with a spatial resolution of 30 m.

Analysis was carried out on a high-quality Landsat-8 OLI satellite picture to detect lineaments. Principal component analysis for image enhancement was initially done in ERDAS 2015, followed by automated line extraction in PCI Geomatica 2016. Through using line density tool in ArcGIS 10.3, a map of lineament density (km/km2) was then generated.

Impermeable surface indicates any region's environmental quality. NDVI satellite derived data was utilized for the derivation of fractional vegetation covers (FVC) [42]. The relationship between the FVC and fractional impervious surface area (FIS) has been shown by Refs. [60,73] as follows:

2.4. Multicollinearity check

A statistical problem known as multicollinearity occurs when at least one input variable is strongly correlated with a number of other input variables. It demonstrates that one input variable may be anticipated linearly out of another input variable (for example, slope and aspect), leading to a nontrivial accuracy of the model's output. Therefore, the multicollinearity between the input parameters needs to be evaluated before the regression model is performed. A linear regression analysis was conducted for such a validation when one of the input parameters was regarded as the dependent variable while the other input variable as the independent variable, and R2 was computed. The tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) of these factors were further calculated by utilizing the given equation correspondingly.

Ta = Tolerance of the “a” variable; VIFa = VIF of the “a” variable.

For each parameter, the procedures were replicated. Multicollinearity issues reflect a tolerance of 0.10 or a VIF of >10. Parameters with tolerance levels of 0.10 or VIF values of >10 must be omitted from the analysis. In order to assess multicollinearity among the parameters, the “create random points” tool was used for the selection of 400 points from the research region. Data were also extracted for the points from each theme layer using the ArcGIS 10.3 tool “Extract point values”. After that, the SPSS (v25) program was used to run the test .

2.5. Analytical hierarchy process

Saaty developed the analytical hierarchy process as an MCDM method for multi-parameter assessment. It allows decision-makers to tackle environmental policy with spatially complex issues. For water resources management, because of its considerable strengths in quantitative and qualitative approaches, the AHP technique is used effectively worldwide. The major benefit of AHP is that it is possible to evaluate the factors, and there is flexibility in resetting the rankings in case of lesser accuracy by experts. Prior to determining ranking and weights in the current research, a number of previously published works were carefully reviewed to ensure that the ranking and weights of elements in various places and environments were correctly taken into account. Using pairwise comparison matrix (PCM) (Table 4), weight of each parameter was determined. The Saaty rating scale (Table 3) was used to determine the relative importance of two separate parameters. A score of 1 signifies that both parameters are equally important, while a score of 9 shows how much more important one parameter is than the other.

Table 4.

Pairwise comparisons matrix for AHP.

| LD | DD | LULC | Sl | Cu | TPI | TWI | Rf | Ge | Rn | FIS | TT | SP | GST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| DD | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.17 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 |

| LULC | 5.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 0.50 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 6.00 |

| Sl | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.33 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Cu | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 2.00 |

| TPI | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.50 |

| TWI | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Rf | 2.00 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Ge | 5.00 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 |

| Rn | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| FIS | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.20 |

| TT | 3.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 |

| SP | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.25 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| GST | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.20 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

LD = Lineament Density; DD = Drainage Density; LULC = Land Use Land Cover; Sl = Slope; Cu= Curvature; TPI = Topographic Position Index; TWI = Topographic wetness Index; Rf = Rainfall; Rn = Roughness; FIS= Fractional Impervious Surface; Ge = Geology; TT = Topsoil Texture; SP= Soil Permeability; GST = General Soil Types.

Table 3.

Rating scale of Satty's for AHP.

| Intensity of significance | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 1 | Equal significance |

| 3 | Weak significance of one over another |

| 5 | Essential significance |

| 7 | Demonstrated significance |

| 9 | Absolute significance |

| 2,4,6,8 | Intermediate Values Between the two adjacent judgements |

The weights indicate the importance of the parameters and their placement in the hierarchy. Therefore, the normalized pairwise comparison matrix (NPCM) was developed (Table 5). Each pairwise judgment value is divided by the total of the same column to get the quotients that make up the NPCM. Each row's quotient values were added together, and the total of each row's values was then divided by the number of factors. End result represents each parameter's significance or weight. Every parameter in NPCM has a weight that ranges from 0 to 1, and the total of all eight parameters is always 1 (see Table 6).

Table 5.

Normalized pairwise matrix for AHP.

| LD | DD | LULC | Sl | Cu | TPI | TWI | Rf | Ge | Rn | FIS | TT | SP | GST | Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.0582 |

| DD | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.0701 |

| LULC | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.1423 |

| Sl | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.1226 |

| Cu | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.0373 |

| TPI | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.0331 |

| TWI | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.0533 |

| Rf | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.0408 |

| Ge | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.1828 |

| Rn | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0356 |

| FIS | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.0223 |

| TT | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.0857 |

| SP | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.0566 |

| GST | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.0592 |

Table 6.

Consistency matrix.

| LD | DD | LULC | Sl | Cu | TPI | TWI | Rf | Ge | Rn | FIS | TT | SP | GST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| DD | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.12 |

| LULC | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.36 |

| Sl | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| Cu | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| TPI | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| TWI | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Rf | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Ge | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.30 |

| Rn | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| FIS | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| TT | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.12 |

| SP | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| GST | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

2.6. Consistency analysis

There may be some degree of discrepancy at the time of the AHP pair-wise evaluation of the parameters. Therefore, it is important to analyze how logically consistent the paired analysis is. The Saaty-introduced consistency ratio (CR) is used to assess the consistency level of the parameter weight. The probability of uncertainty was assessed using the principal Eigen value and the consistency index (CI). The consistency index was generated from the given formula as a measurement of accuracy.

where, λmax = 15.76 is the principal eigen value from PCM, and n is the total number of classes.

The Consistency Ratio (CR) is the indicator of reliability in pairwise comparison matrices and is computed using the following equation.

where, RI is the random consistency index value shown in Table 7. The consistency value must be below 0.1. Where the CR is below 10% (0.10%) it is regarded more accurate, otherwise it is required to reassign the value of PCM and recalculate the weight of parameters. The value achieved is 0.08, thus the PCM and computed weights can be judged to be appropriate .

Table 7.

RI values for various number of parameters.

| N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCI value | 0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 1.49 | 1.51 | 1.48 | 1.56 | 1.57 |

2.7. Score determination

The rating is assigned on a scale between 1 and 9 depending on ideal conditions and groundwater identification relevancy. Maximum points (9) were assigned to the most suitable sub-criteria, minimum points (1) to the least suitable sub-criteria, and intermediate points to the moderately acceptable sub-criteria for GPZ identification (Table 8). The score was consequently given for selected parameters, including lineament density, drainage density, land use land cover, slope, curvature, topographic position index, topographic wetness index, rainfall, geology, roughness, fractional impervious surface, topsoil texture, soil permeability, and general soil types.

Table 8.

Weights and ranks assigned for different subclasses of parameters.

| Parameters | Weight | Influence | Sub-category/value | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineament Density | 0.06 | 6 | Very low (<0.47) | 2 |

| Low (0.47–0.73) | 4 | |||

| Moderate (0.73–0.96) | 6 | |||

| High (0.96–1.21) | 8 | |||

| Very high (>1.21) | 9 | |||

| Drainage Density | 0.07 | 7 | Very low (<0.75) | 9 |

| Low (0.75–1.5) | 8 | |||

| Moderate (1.5–2.25) | 6 | |||

| High (2.25–3.00) | 4 | |||

| Very High (>3.00) | 3 | |||

| LULC | 0.14 | 14 | Built up land | 2 |

| Agriculture land | 4 | |||

| Fallow land | 5 | |||

| Vegetation/Forest | 8 | |||

| Water bodies | 9 | |||

| Slope | 0.12 | 12 | Flat (0–3.98) | 8 |

| Gentle (3.98–8.37) | 6 | |||

| Moderate (8.37–14.95) | 4 | |||

| Steep (14.95–24.32) | 3 | |||

| Very Steep (24.32–51.00) | 2 | |||

| Curvature | 0.04 | 4 | Very low (<−1.10) | 2 |

| Low (−1.10 to 0.25) | 3 | |||

| Moderate (0.25–1.61) | 4 | |||

| High (1.61–4.33) | 6 | |||

| Very High (4.33–25.44) | 8 | |||

| TPI | 0.03 | 3 | −12.13 to 1.87 | 5 |

| −1.87–7.58 | 4 | |||

| 7.58–24.14 | 3 | |||

| 24.14–128.24 | 2 | |||

| TWI | 0.05 | 5 | 3.16–5.28 | 3 |

| 5.28–7.61 | 4 | |||

| 7.61–9.94 | 5 | |||

| 9.94–12.27 | 6 | |||

| 12.27–23.06 | 7 | |||

| Rainfall | 0.04 | 4 | 1407–1441 | 3 |

| 1441–1479 | 3 | |||

| 1479–1519 | 4 | |||

| 1519–1557 | 4 | |||

| 1557–1618 | 5 | |||

| Geology | 0.18 | 18 | U | 5 |

| Deltaic Silt | 5 | |||

| Marshy Clay & peat | 4 | |||

| Waterbody | 8 | |||

| Tidal Deltaic Deposits | 6 | |||

| Roughness | 0.04 | 4 | 0.009–0.383 | 7 |

| 0.383–0.456 | 5 | |||

| 0.456–0.521 | 4 | |||

| 0.521–0.593 | 3 | |||

| 0.593–1 | 2 | |||

| FIS | 0.02 | 2 | <0.40 | 8 |

| 0.4–0.5 | 6 | |||

| 0.5–0.6 | 4 | |||

| 0.6–0.7 | 3 | |||

| 0.7–1 | 2 | |||

| Topsoil Texture | 0.09 | 9 | Clay | 1 |

| Silty Clay | 3 | |||

| Sandy Clay | 4 | |||

| silty loam | 6 | |||

| Clay Loam | 7 | |||

| Soil Permeability | 0.06 | 6 | Rapid | 7 |

| Moderate | 6 | |||

| Mostly Moderate WS Slow | 4 | |||

| Slow | 2 | |||

| Mostly Slow WS Moderate | 3 | |||

| Lake | 9 | |||

| General Soil Types | 0.06 | 6 | Calcareous Brown/Dark gray Floodplain | 4 |

| Non-calcareous Dark Gray Floodplain | 6 | |||

| Peat | 8 | |||

| Waterbodies | 9 | |||

| Urban | 2 |

2.8. Identification of groundwater potential zones

The GWPI is a dimensionless quantity that represents the GWPZs of a specific region which is derived using the following equation.

Wj = Weight of the parameter j; Ri = Class rank of parameter i; n = Number of parameters.

The GWPI was calculated on the basis of the equation for each grid using the ArcGIS 10.3 Weighted Overlay Analysis Tool. For users, the WOA is a strategy to address complicated spatial problems in site suitability based on common evaluations of many variables. The WOA technique was therefore utilized for GWPZ mapping.

LD = Lineament Density; DD = Drainage Density; LULC = Land Use Land Cover; Sl = Slope; Cu= Curvature; TPI = Topographic Position Index; TWI = Topographic wetness Index; Rf = Rainfall; Rn = Roughness; FIS= Fractional Impervious Surface; Ge = Geology; TT = Topsoil Texture; SP= Soil Permeability; GST = General Soil Types and the symbol ‘w’ indicates the weight of parameters, and ‘r’ indicates the rank of sub parameters.

2.9. Sensitivity analysis

This research employs the map removal sensitivity analysis approach to comprehend the influential thematic layers of the created GPZ. The sensitivity analysis was conducted in the ArcGIS 10.3 platform using the “Raster Calculator” and “Raster Properties” tools. This investigation was conducted to determine the effects of removing any of the thematic layers from the GWPZ computation. The sensitivity index was calculated by selectively erasing one theme layer at a time, then superimposing the remaining layers.

SI = Sensitivity index; GWPZ = Groundwater potential zone determined by combining all thematic layers; GWPZʹ = Groundwater potential zone determined by eliminating one thematic layer; N = Number of parameters considered for generating the GWPZ map; and n = Number of parameters considered for generating the GPWZʹ map.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Multicollinearity analysis

The result of multicollinearity analysis shows that the tolerance values and VIF values for all 14 thematic layers are greater than 0.10 and less than 10, respectively, at 0.01 and 0.05 (Table 9). It indicates that there is no collinearity among the thematic layers and, hence, no uncertainties that might affect the result owing to the multicollinearity issue .

Table 9.

Collinearity Statistics of the parameters of GWPZ.

| Parameters | Tolerance | VIF | Parameters | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | 0.640 | 1.563 | TWI | 0.540 | 1.852 |

| curvature | 0.520 | 1.924 | FIS | 0.628 | 1.593 |

| Drainage density | 0.858 | 1.165 | Lineament Density | 0.858 | 1.166 |

| LULC | 0.690 | 1.449 | Soil types | 0.853 | 1.172 |

| Rainfall | 0.896 | 1.116 | Soil permeability | 0.455 | 2.200 |

| Geology | 0.840 | 1.191 | Soil Texture | 0.543 | 1.842 |

| TPI | 0.442 | 2.265 | Roughness | 0.889 | 1.125 |

3.2. Evaluation of thematic layers

3.2.1. Geology

Geological context is critical to the presence and spatial distribution of groundwater in any region as it has a direct impact on the permeability and porosity of aquifers [8,24]. The geological formations of the Jashore district are divided into four main categories, such as waterbodies, tidal deltaic deposits, deltaic silt, marshy clay, and peat. The lake covers around 1.34% of the study area and is predicted to promote groundwater replenishment. Tidal deltaic deposits are fine sand to silty sand that is light to yellowish gray in color and is deposited primarily during floods in channels, crevasse splays, natural levees, and flood plains, including channel bars and point bars. It covers only around 0.24% of the study area. Deltaic silt is light gray to gray-colored fine sand to clay silt deposited by distributaries in flood basins and covers around 81.15% of the study area. Gray or bluish gray clay, black herbaceous peat, and yellowish gray silt mainly fall under the category of marshy clay and peat. Alternating beds of peat and peaty clay are usual in beels. This category covers around 17.26% of the area. The geological categories are graded as lake > tidal deltaic deposits > deltaic silt > marshy clay and peat, relying on their hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity for groundwater replenishment.

3.2.2. LULC

The land use and land cover of an area are largely controlled by groundwater, that also performs a crucial role in the establishment and accessibility of this asset. Various hydrogeological processes, such as infiltration, evapotranspiration and surface runoff are governed by it [41]. As it was anticipated that waterbodies would promote replenishment and raise groundwater table at proximate sites, they were assigned the highest score. The deeper plant roots cause the ground to become loose and the rocks to crumble which leads to greater water penetration and improvement of groundwater levels. Thus, the forest and vegetation cover was scored higher. The surface drainage rate on fallow land is higher owing to thin soil, so it receives a lower score. For groundwater recharge, agricultural land is preferred over fallow, rocky, or built-up land because loose soils affect water penetration into the subsurface. Consequently, agricultural land got a passable grade. Due to the concrete construction of the built-up region, there is high surface drainage and little absorption. As a result, it received the lowest score. In the study area, forest or vegetation is the dominant land use or land cover, covering 1270.71 km2 (50.19%), agriculture, covering 567.313 km2 (22.41%), built-up area, covering 340.99 km2 (13.47%), waterbodies, covering 237.42 km2 (9.38%), and fallow land, covering 115.26 km2 (4.55%).

3.2.3. Slope

The slope of an area has a prominent function in regulating surface drainage and thus water percolation capacity [37]. Slope of the study area ranges from 0° to 51.77°. About 1840.26 km2 (72.69%) of the area has a flat slope (0°–3.98°). Gentle (3.98°–8.37°), moderate (8.37°–14.95°), steep (14.95°–24.32°), and very steep (24.32°–51.00°) slopes cover 459.11 km2 (18.13%), 222.88 km2 (8.80%), 9.44 km2 (0.37%), and 0.02 km2 (0.001%) of the area, respectively. Areas with a flat and gentle slope encourage high water penetration and groundwater replenishment, on the other hand, areas with a steep slope enable high storm water runoff and therefore have less infiltration [28,39]. It is noted that vast area in Jashore district contains flat to gentle slope, which may be characterized as “excellent” for groundwater resources due to high infiltration capability.

3.2.4. Topsoil texture

Soil texture is an important indicator for evaluating soil physical qualities since it is strongly correlated to the composition, porosity, adherence, and viscosity of soil [17]. It is considered as a major element in controlling the rate of water penetration, which affects groundwater replenishment. Five different types of topsoil textures are found in Jashore district and are graded as clay loam > silty loam > sandy clay > silty clay > clay on the basis of porosity as well as permeability. Clay loam, silty loam, sandy clay, silty clay, and clay cover 37.1%, 14%, 20.94%, 13.61%, 13.84%, and 13.31% of the study area, respectively.

3.2.5. Drainage density

The potential for groundwater is greatly influenced by drainage density, which is a crucial metric for evaluating an area's lithology and infiltration rate [8,24]. It is computed by dividing the sum of the lengths of all the streams by the entire surface area of the drainage basin [24] and is inversely proportional to soil permeability [38]. The area's groundwater level is negatively impacted by high drainage density since it leads to little infiltration. On the other hand, poor drainage density indicates strong infiltration, as a result, makes a significant contribution to groundwater potential [69,86]. Therefore, lower drainage density regions are given a higher score, whereas higher drainage density regions are given a lower score. The drainage density of the study area varies from 0 to 6.67 km2/km2. Very low (0.75 km/km2), low (0.75–1.5 km/km2), moderate (1.5–2.25 km/km2), high (2.25–3.00 km/km2), and very high (>3.00 km/km2) drainage densities cover 75.93 km2 (2.99%), 274.38 km2 (10.84%), 747.41 km2 (29.52%), 674.05 km2 (26.62%), and 759.93 km2 (30.01%) of the study area, respectively.

3.2.6. General soil types

The capacity of the area to retain water and the pace of storm water infiltration are strongly affected by the type of soil there. As a consequence, it might be considered one of the essential factors for identifying groundwater potential zones [87]. This criterion is classified into five categories, such as calcareous brown or dark gray floodplains, non-calcareous dark gray floodplains, peatlands, waterbodies, and urban areas. Because waterbody is positively associated with groundwater replenishment and urban is negatively associated with groundwater replenishment, these are assigned the highest and lowest scores, respectively. Again, on the basis of infiltration capability, the three soil types are graded as follows: peat > non-calcareous dark gray floodplain > calcareous brown or dark gray floodplain. Peat soil generally contains organic material at the top or embedded behind a mineral soil surface at a depth of up to 40 cm. Calcareous dark gray floodplains have a cambic B-horizon and non-calcareous dark gray topsoil and subsoil. Calcareous brown or dark gray floodplain soils have a cambic B-horizon that is predominantly oxidized, containing lime in the profiles. From the general soil type map of the study area, it can be depicted that about 97.44% of the area is covered with calcareous brown or dark gray floodplain. Thus, it implies that the soil of the study area has a lower infiltration ability to replenish ground water and that the region has a lower prospect for groundwater availability and development.

3.2.7. Lineament density

Lineaments comprise linear or curvilinear characteristics of earth surface like faults, joints, folds, dikes, crustal cracks, etc. (T [17]. and is a significant hydrological indicator that aids in understanding groundwater occurrence [24]. The flow and availability of groundwater are determined by the water penetration of lineaments. Higher lineament density means more groundwater replenishment, while lower density means less chance of a potential groundwater zone [21]. Therefore, considering this concept, areas with high lineament density were assigned a higher score than those with low lineament density. The study area was categorized into five zones in terms of lineal density. Very low (0.47 km/km2), low (0.47–0.73 km/km2), moderate (0.73–0.96 km/km2), high (0.96–1.21 km/km2), and very high (>1.21 km/km2) lineament density covers 2148.37 km2 (84.86%), 304.78 km2 (12.04%), 62.96 km2 (2.49%), 15.18 km2 (0.60%), and 0.40 km2 (0.02%) of the study area, respectively. Thus, most of the study area has very low lineament density, which indicates lower groundwater replenishment in the region. According to the lineament density map, high lineament density can be found in just a tiny fraction of the area's eastern, northwestern, and southwestern parts.

3.2.8. Soil permeability

The degree to which a soil allows water to pass through it is known as its permeability. The gaps between soil particles, or a soil's porosity, are most closely related to how permeable it is; however, the shape of the pores and how they are connected to one another also have an effect. Soil layering can also have a substantial impact in natural soils. This makes it one of the crucial components in the identification of groundwater potential zones. Five kinds of soil permeability are used in the research area: rapid, moderate, mostly moderate, slow, mostly slow, and lake. Rapid soil permeability in the area enables more groundwater replenishment and is assigned a high score. From the soil permeability map of Jashore district, it can be seen that most of the area, which is about 85.06% of the study area, has moderate to mostly moderate soil permeability.

3.2.9. Topographic wetness index (TWI)

The Topographic Wetness Index (TWI) is commonly applied to calculate topographic influence on hydrological phenomena and to indicate possible groundwater penetration driven by topographic impacts [48]. The TWI values of the study area range between 3.16 and 23.01. Based on the maximum and minimum value, these are categorized into five classes, such as 3.16–5.28, 5.28–7.61, 7.61–9.94, 9.94–12.27, and 12.27–23.06. Areas with low TWI values, indicating a propensity for surface runoff, are given a lower score, while areas with high TWI values, indicating a propensity for soil moisture retention, are given a higher score. The TWI map of Jashore district depicts that about 76.6% of the area has TWI values ranging from 5.28 to 9.94.

3.2.10. Rainfall

Rainfall is important in the hydrological cycle because it regulates groundwater accumulation and replenishment, which affects how much water is present to seep into groundwater aquifers [85]. Infiltration is strongly affected by rainfall quantity and period. High intensity but brief duration rainfall indicates less absorption and much overflow, and vice versa [14]. A high yearly precipitation distribution in general implies the existence of high groundwater levels in certain regions. The area's average yearly precipitation varies between 1407 mm and 1618 mm. Based on the maximum and minimum value of average yearly precipitation, rainfall has been categorized into three classes such as low (1407–1479 mm), moderate (1479–1557 mm) and high (1557–1618 mm) rainfall. During the study, areas with high average yearly precipitation were given a higher score than those with low average yearly precipitation. From the rainfall map of the study area, it can be observed that eastern portion of the area receives high yearly rainfall, whereas central portion of the area experiences moderate and western part of the area experiences less amount of rainfall.

3.2.11. Roughness

Roughness reflects the degree of elevation variation among adjoining pixels in a digital elevation model (DEM) [74]. It indicates fluctuation of the elevation in general. The greater the roughness value, the more the elevation fluctuates, and vice versa [8]. Undulated terrain is typical of a hilly location, wherein erosion and weathering activities continually transform rough terrain into a uniform and level landscape in the long term [56]. The roughness values in the study area vary from 0.01 to 0.95 and are categorized into five classes for determining the groundwater potential zones. A roughness value of 0.01–0.38, 0.38–0.46, 0.46–0.52, 0.52–0.59, and 0.59–1.00 covers 39.31%, 33.48%, 18.89%, 6.79%, and 1.53% of the area, respectively. For areas with minimal roughness values, high scores are given, and vice versa.

3.2.12. Curvature

Curvature, which may be convex or concave, is a mathematical expression of the kind of surface protrusion [56]. Convex and concave planes both have a propensity to flow downward and gather water, respectively. The curvature values for the study area range from −14.44 to 25.29 and are classified into five categories, such as very low (−1.10), low (−1.10–0.25), moderate (0.25–1.61), high (1.61–4.33), and very high (4.33–25.44). Areas with a high value of curvature are assigned a high score, and vice versa. The curvature map of Jashore district depicts that about 92.76% of the area has low and moderate curvature values ranging from −1.10 to 1.61.

3.2.13. Topographic position index (TPI)

A prominent technique for identifying topographic slopes and generating landform classification is the topographic position index (TPI) [23]. An area can be categorized as ridgetops, cliffs, mountaintops, or mid-slope (TPI > a specific threshold), valley bottoms or recessions (TPI a specific threshold), or flatlands (TPI = 0) based on this indicator value [55]. A high value for this indicator implies increased storm water runoff and reduced water penetration, resulting in inadequate groundwater recharge [49]. The TPI values of the study area range from −11.09 to 74.76 and are categorized into four classes: 12.13 to −1.87, −1.87 to 7.58, 7.58 to 24.14, and 24.14 to 128.24. Areas with high TPI values are given a low score, and vice versa. The TPI map of the study area shows that about 80.12% of the area has TPI values ranging from −1.87 to 7.58.

3.2.14. Fractional impervious surface (FIS)

Impervious surfaces, whether natural or man-made, are hard surfaces that impede rainfall penetration and groundwater replenishment while promoting higher portions of runoff and less time for absorption [76]. Thus, impervious surface assessment plays an essential role in the determination of groundwater availability. Since a large proportion of impervious surface limits a region's groundwater occurrence, areas with low FIS values are given a high score and are regarded as having a high groundwater potentiality. The values of FIS in the study area range from −1.07597E−006 to 1 and are classified into five categories, such as 0.40, 0.4–0.5, 0.5–0.6, 0.6–0.7, and 0.7–1. On the FIS map of Jashore district, it can be seen that about 83.49% of the area has FIS values ranging between 0.7 and 1, which indicate poor groundwater availability.

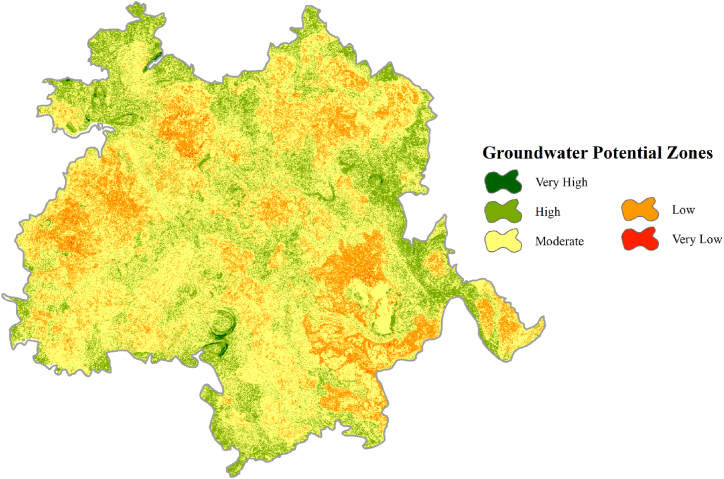

3.3. Assessment of groundwater potential zones

The fourteen thematic layers were combined on a GIS platform to generate a single groundwater potential map that displays the appropriate groundwater zone. The map was divided into five different categories, namely very low, low, moderate, high, and very high (Fig. 6). A vast portion of the study area covering 1615.51 km2 (64.37%) is classified as moderate groundwater potential zone. Again, high groundwater potential zone and low ground water potential zone covers 444.75 km2 (17.72%) and 441.79 km2 (17.60%) of the Jashore district. A very little portion of the study area covering 3.59 km2 (0.14%) and 3.96 km2 (0.16%) is classified as very low and very high ground water potential zones. A significant fraction (82.12%) of the study area demonstrates very low to moderate ground water potential which indicates that the groundwater supply is fairly constrained and in a decreasing stage in the area.

Fig. 6.

Groundwater potential zones of the study area.

3.4. Sensitivity analysis of the groundwater potential map

The geology thematic layer in groundwater potential zoning is the most sensitive one, according to the findings of the map removal sensitivity study (Table 10). The mean variation index for this thematic layer is 0.804%, while the standard deviation (SD) is 0.161%. Slope and land use/land cover (LULC) thematic layers have mean variation indices of 0.798% and 0.784%, respectively, and standard deviations of 0.266% and 0.433%, respectively. Higher values of the variation index are obtained after omitting the geology thematic layer, accompanied by LULC and slope, suggesting that these elements have a significant impact on groundwater availability. The removal of the geology thematic layer also reveals that the regions with very low and low groundwater potentialities grow by 11.26% and 44.69%, respectively, whereas the areas with moderate, high, and very high groundwater potentialities decline by 38.15%, 17.64%, and 0.16%, respectively. The region with very low and low groundwater potentiality increases by 5.27% and 61.17%, respectively, whereas the areas with moderate, high, and very high groundwater potentiality drop by 48.64%, 17.65%, and 0.16%, respectively, when the LULC thematic layer isn't there. The removal of the slope thematic layer led to a rise in the area of very low and low groundwater potentiality by 12.13% and 42.19%, respectively, and a reduction in the area of moderate, high, and very high groundwater potentiality by 36.67%, 17.49%, and 0.16%, respectively. Omission of other thematic layers such as general soil types, topsoil texture, soil permeability, drainage density, lineament density, TWI, rainfall, curvature, roughness, TPI, and FIS leads to an rise in the zone of very low groundwater potentiality by 0.66%, 0.65%, 0.37%, 0.89%, 0.17%, 0.62%, 0.24%, 0.24%, 0.29%, 0.17%, and 0.03%, respectively, as well as an rise in the zone of low groundwater potentiality by 10.82%, 24.72%, 15.32%, 15.24%, 5.88%, 11.00%, 6.39%, 6.16%, 7.54%, 5.27%, and 1.46%, respectively. Change in the area of moderate groundwater potentiality can be seen due to the removal of general soil types, topsoil texture, soil permeability, drainage density, lineament density, TWI, rainfall, curvature, roughness, TPI, and FIS thematic layers by +0.22%, −8.21%, −0.82%, −0.07%, +2.49%, +0.47%, +1.44%, +1.24%, and +1.62%, respectively (Table 11). With the removal of each thematic layer, the regions with high and very high groundwater potential also exhibit significant changes. It indicates that any criterion's removal will significantly affect how the groundwater potential is defined since such criterion help water percolate for groundwater replenishment.

Table 10.

Statistical analysis of map removal sensitivity analysis.

| Thematic layer Removal |

Variation Index (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

| General Soil Types | 0 | 0.484809 | 0.178047 | 0.044774 |

| Topsoil Texture | 0 | 0.95921 | 0.253697 | 0.136618 |

| Soil Permeability | 0 | 0.456323 | 0.081149 | 0.096368 |

| Geology | 0.311629 | 2.342696 | 0.803849 | 0.161256 |

| LULC | 0 | 1.948567 | 0.783847 | 0.43336 |

| Slope | 0 | 1.554428 | 0.797611 | 0.26643 |

| Drainage Density | 0 | 0.823398 | 0.157447 | 0.089793 |

| Lineament Density | 0 | 0.43464 | 0.332304 | 0.075484 |

| TWI | 0 | 0.405937 | 0.173694 | 0.073105 |

| Rainfall | 0.056354 | 0.43464 | 0.318616 | 0.051015 |

| Curvature | 0 | 0.461538 | 0.329705 | 0.055515 |

| Roughness | 0 | 0.464217 | 0.282172 | 0.098353 |

| TPI | 0.177242 | 1.574545 | 0.361726 | 0.028191 |

| FIS | 0.208517 | 0.520091 | 0.480971 | 0.017893 |

Table 11.

Changes in the groundwater potential zones due to removal of the thematic layer.

| Thematic layer Removal | Very low | Low | Moderate | High | Very high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Soil Types | +0.66% | +10.82% | +0.22% | −11.58% | −0.13% |

| Topsoil Texture | +0.65% | +24.72% | −8.21% | −17.00% | −0.16% |

| Soil Permeability | +0.37% | +15.32% | −0.82% | −14.74% | −0.14% |

| Geology | +11.26% | +44.69% | −38.15% | −17.64% | −0.16% |

| LULC | +5.27% | +61.17% | −48.64% | −17.65% | −0.16% |

| Slope | +12.13% | +42.19% | −36.67% | −17.49% | −0.16% |

| Drainage Density | +0.89% | +15.24% | −0.07% | −15.94% | −0.12% |

| Lineament Density | +0.17% | +5.88% | +2.49% | −8.43% | −0.11% |

| TWI | +0.62% | +11.00% | +0.47% | −11.97% | −0.11% |

| Rainfall | +0.24% | +6.39% | +1.44% | −7.99% | −0.08% |

| Curvature | +0.24% | +6.16% | +1.24% | −7.58% | −0.07% |

| Roughness | +0.29% | +7.54% | +1.62% | −9.35% | −0.10% |

| TPI | +0.17% | +5.27% | +1.31% | −6.68% | −0.07% |

| FIS | +0.03% | +1.46% | +0.93% | −2.38% | −0.03% |

| 0.14% | 17.60% | 64.37% | 17.72% | 0.16% |

4. Conclusion

The GIS-based AHP approach, which is demonstrated to be a potent and useful tool, has been utilized to map the geographical distribution of groundwater potential zones in the Jashore district of Bangladesh. Fourteen criteria, including lineament density, drainage density, land use land cover, slope, curvature, topographic position index, topographic wetness index, rainfall, geology, roughness, fractional impervious surface, topsoil texture, soil permeability, and general soil types, with a score weight of 6%, 7%, 14%, 12%, 4%, 3%, 5%, 4%, 18%, 4%, 2%, 9%, 6%, and 6% respectively, were combined in ArcGIS to assess the groundwater potential of various places within the study region. The analysis reveals that a vast portion, covering 64.37% of the study region has moderate groundwater potential zone. Again, high and very high groundwater potential zones cover 17.72% and 0.16% of the study area, respectively. On the other hand, low and very low groundwater potential zones cover 17.60% and 0.14% of the study area, respectively. A significant fraction covering 82.12% of the study area demonstrates very low to moderate groundwater potential, suggesting that the area's groundwater supply is somewhat limited and in a falling stage. For extensive groundwater management, very high and very high groundwater potential zones do not have substantial restrictions. For effective surface and groundwater management, the areas designated as moderate groundwater potential zones must organize their agriculture, plantations, and other suitable economic activities properly. Very low and low groundwater potential zones are observed to have a significant portion of built-up areas and fallow lands; as a result, these regions require particular attention and management for extraction and usage of water resources. The groundwater potential map's sensitivity analysis shows that the most important factor in zoning for groundwater potential is geology. However, thematic layers such as land use and land cover (LULC) and slope have been found to be moderately sensitive elements.

The current research confirms that the fusion of GIS and AHP is a cost-effective strategy for groundwater prospecting that requires less manpower and overcomes the time restrictions of conventional methods. It offers a valuable database for groundwater planning and management. It can be used as a guide for the relevant authorities and decision-makers to design future artificial recharge initiatives to ensure sustainable groundwater consumption for the study area's current and future generations. Additionally, this study has enormous potential for enhancing irrigation systems and raising agricultural productivity. Since the methodology used in this study was quite effective and precise, it might be taken into account for groundwater investigation in various regions. In this study, only a restricted number of thematic layers were considered; however, the inclusion of a few more thematic layers, such as aquifer's thickness, groundwater depth during pre- and post-monsoon, recharge rate, the quantity of water drawn for agriculture and household use, distance to rivers, and pond frequency, would have provided more trustworthy results. We were unable to use them in our research work because of the limited availability of data on a geographical scale. The actual groundwater prospects of the observation wells could have been compared with the determined groundwater potential zones to make the work more thorough. But due to data unavailability, we were unable to perform this validation. The study's results are still reliable and logical, despite these limitations and flaws in the research methodology. Water bodies need to be quickly restored since they have been recognized as a key requirement for groundwater potential. According to the findings of this study, forest and vegetation cover are also valuable conditioning components. However, it is an irrefutable reality that forests are declining and degrading. Protecting the forest cover may thus help keep the groundwater recharge rate high.

Ethical approval

The authors declare No ethical approval required. Ethical approval for this type of study is not required by our institute.

Author contribution statement

Kaniz Fatema; Md. Ashikur Rahman Joy; F.M. Rezvi Amin: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Showmitra Kumar Sarkar: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Kaniz Fatema, Email: kanizfatema1013@gmail.com.

Md. Ashikur Rahman Joy, Email: joy1617047@stud.kuet.ac.bd.

F.M. Rezvi Amin, Email: rezviamin.kuet@gmail.com.

Showmitra Kumar Sarkar, Email: mail4dhrubo@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Abdalla F., Moubark K., Abdelkareem M. Groundwater potential mapping using GIS, linear weighted combination techniques and geochemical processes identification, west of the Qena area, Upper Egypt. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2020;14(1):1350–1362. doi: 10.1080/16583655.2020.1822646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal E., Agarwal R., Garg R.D., Garg P.K. Delineation of groundwater potential zone: an AHP/ANP approach. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013;122(3) doi: 10.1007/s12040-013-0309-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed M.T., Hasan M.Y., Monir M.U., Samad M.A., Rahman M.M., Islam Rifat M.S., Islam M.N., Khan A.A.S., Biswas P.K., Jamil A.H.M.N. Evaluation of hydrochemical properties and groundwater suitability for irrigation uses in southwestern zones of Jashore, Bangladesh. Groundwater Sustain. Dev. 2020;11 doi: 10.1016/j.gsd.2020.100441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajay Kumar V., Mondal N.C., Ahmed S. Identification of groundwater potential zones using RS, GIS and AHP techniques: a case study in a part of Deccan Volcanic Province (DVP), Maharashtra, India. J. Ind. Soc. Remote Sens. 2020;48(3) doi: 10.1007/s12524-019-01086-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Abadi A.M., Al-Temmeme A.A., Al-Ghanimy M.A. A GIS-based combining of frequency ratio and index of entropy approaches for mapping groundwater availability zones at Badra–Al Al-Gharbi–Teeb areas, Iraq. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2016;2(3):265–283. doi: 10.1007/s40899-016-0056-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ara M.H., Mondal U.K., Dhar P.K., Uddin M.N. Presence of heavy metals in Vegetables collected from Jashore, Bangladesh: human health risk assessment. J. Chem. Health Risks. 2018;8:277–287. doi: 10.22034/jchr.2018.544710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arshad A., Zhang Z., Zhang W., Dilawar A. Mapping favorable groundwater potential recharge zones using a GIS-based analytical hierarchical process and probability frequency ratio model: a case study from an agro-urban region of Pakistan. Geosci. Front. 2020;11(5) doi: 10.1016/j.gsf.2019.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arulbalaji P., Padmalal D., Sreelash K. GIS and AHP techniques based delineation of groundwater potential zones: a case study from southern western Ghats, India. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38567-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arunbose S., Srinivas Y., Rajkumar S., Nair N.C., Kaliraj S. Groundwater for Sustainable Development Remote sensing, GIS and AHP techniques based investigation of groundwater potential zones in the Karumeniyar river basin, Tamil Nadu, southern India. Groundwater Sustain. Dev. 2021;14 doi: 10.1016/j.gsd.2021.100586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arunbose S., Srinivas Y., Rajkumar S., Nair N.C., Kaliraj S. Remote sensing, GIS and AHP techniques based investigation of groundwater potential zones in the Karumeniyar river basin, Tamil Nadu, southern India. Groundwater Sustain. Dev. 2021;14 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awawdeh M., Obeidat M., Al-Mohammad M., Al-Qudah K., Jaradat R. Integrated GIS and remote sensing for mapping groundwater potentiality in the Tulul al Ashaqif, Northeast Jordan. Arabian J. Geosci. 2014;7(6) doi: 10.1007/s12517-013-0964-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayazi M.H.A., Pirasteh S., Pili A.∼K.A., Biswajeet P., Nikouravan B., Mansor S. Disasters and risk reduction in groundwater: Zagros Mountain, Southwest Iran using geoinformatics techniques. Disaster Adv. 2010;3(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjmel K., Amraoui F., Boutaleb S., Ouchchen M., Tahiri A., Touab A. Mapping of groundwater potential zones in crystalline terrain using remote sensing, GIS techniques, and multicriteria data analysis (Case of the ighrem region, Western Anti-Atlas, Morocco) Water. 2020;12(2) doi: 10.3390/w12020471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhry A.K., Kumar K., Alam M.A. Mapping of groundwater potential zones using the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and geospatial technique. Geocarto Int. 2019:1–22. doi: 10.1080/10106049.2019.1695959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choubin B., Rahmati O., Soleimani F., Alilou H., Moradi E., Alamdari N. Spatial Modeling in GIS and R for Earth and Environmental Sciences. 2019. Regional groundwater potential analysis using classification and regression trees. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dar I.A., Sankar K., Dar M.A. Deciphering groundwater potential zones in hard rock terrain using geospatial technology. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011;173(1–4) doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dar T., Rai N., Bhat A. Delineation of potential groundwater recharge zones using analytical hierarchy process (AHP) Geol., Ecol., Landscapes. 2020:1–16. doi: 10.1080/24749508.2020.1726562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das B., Pal S.C. Assessment of groundwater recharge and its potential zone identification in groundwater-stressed Goghat-I block of Hugli District, West Bengal, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020;22(6):5905–5923. doi: 10.1007/s10668-019-00457-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das B., Pal S.C., Malik S., Chakrabortty R. Modeling groundwater potential zones of Puruliya district, West Bengal, India using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Geol., Ecol., Landscapes. 2019;3(3):223–237. doi: 10.1080/24749508.2018.1555740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das N., Mukhopadhyay S. Application of multi-criteria decision making technique for the assessment of groundwater potential zones: a study on Birbhum district, West Bengal, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020;22 doi: 10.1007/s10668-018-0227-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das S., Gupta A., Ghosh S. Exploring groundwater potential zones using MIF technique in semi-arid region: a case study of Hingoli district, Maharashtra. Spatial Inf. Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s41324-017-0144-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das S., Pardeshi S.D. Integration of different influencing factors in GIS to delineate groundwater potential areas using IF and FR techniques: a study of Pravara basin, Maharashtra, India. Appl. Water Sci. 2018;8(7):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s13201-018-0848-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Reu J., Bourgeois J., Bats M., Zwertvaegher A., Gelorini V., De Smedt P., Chu W., Antrop M., De Maeyer P., Finke P., Van Meirvenne M., Verniers J., Crombé P. Application of the topographic position index to heterogeneous landscapes. Geomorphology. 2013;186:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doke A.B., Zolekar R.B., Patel H., Das S. Geospatial mapping of groundwater potential zones using multi-criteria decision-making AHP approach in a hardrock basaltic terrain in India. Ecol. Indicat. 2021;127 doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Etikala B., Golla V., Li P., Renati S. Deciphering groundwater potential zones using MIF technique and GIS: a study from Tirupati area, Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh, India. HydroResearch. 2019;1 doi: 10.1016/j.hydres.2019.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans I.S. vol. 6. 2019. General geomorphometry, derivatives of altitude, and descriptive statistics. (Spatial Analysis in Geomorphology). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fashae O.A., Tijani M.N., Talabi A.O., Adedeji O.I. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in the crystalline basement terrain of SW-Nigeria: an integrated GIS and remote sensing approach. Appl. Water Sci. 2014;4(1) doi: 10.1007/s13201-013-0127-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fashae O.A., Tijani M.N., Talabi A.O., Adedeji O.I. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in the crystalline basement terrain of SW-Nigeria: an integrated GIS and remote sensing approach. Appl. Water Sci. 2014;4(1):19–38. doi: 10.1007/s13201-013-0127-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh P.K., Bandyopadhyay S., Jana N.C. Mapping of groundwater potential zones in hard rock terrain using geoinformatics: a case of Kumari watershed in western part of West Bengal. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016;2(1) doi: 10.1007/s40808-015-0044-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gnanachandrasamy G., Zhou Y., Bagyaraj M., Venkatramanan S., Ramkumar T., Wang S. Remote sensing and GIS based groundwater potential zone mapping in Ariyalur district, Tamil Nadu. J. Geol. Soc. India. 2018;92(4) doi: 10.1007/s12594-018-1046-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guru B., Seshan K., Bera S. Frequency ratio model for groundwater potential mapping and its sustainable management in cold desert, India. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2017;29(3):333–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2016.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hajkowicz S., Collins K. A Review of multiple criteria analysis for water resource planning and management. Water Resour. Manag. 2007;21(9):1553–1566. doi: 10.1007/s11269-006-9112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussein A.-A., Govindu V., Nigusse A.G.M. Evaluation of groundwater potential using geospatial techniques. Appl. Water Sci. 2017;7(5) doi: 10.1007/s13201-016-0433-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutti B. Identification of groundwater potential zone using geoinformatics in Ghataprabha basin, north Karnataka, India. Int. J. Geomatics Geosci. 2011;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim-Bathis K., Ahmed S.A. Geospatial technology for delineating groundwater potential zones in Doddahalla watershed of Chitradurga district, India. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2016;19(2):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrs.2016.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ifediegwu S.I. Assessment of groundwater potential zones using GIS and AHP techniques: a case study of the Lafia district, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Appl. Water Sci. 2022;12(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jahan C.S., Rahaman M.F., Arefin R., Ali M.S., Mazumder Q.H. Delineation of groundwater potential zones of Atrai–Sib river basin in north-west Bangladesh using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2019;5(2):689–702. doi: 10.1007/s40899-018-0240-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jahan C.S., Rahaman M.F., Arefin R., Ali S., Mazumder Q.H. Morphometric analysis and hydrological inference for water resource management in Atrai-Sib river basin, NW Bangladesh using remote sensing and GIS technique. J. Geol. Soc. India. 2018;91(5):613–620. doi: 10.1007/s12594-018-0912-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaiswal R.K., Mukherjee S., Krishnamurthy J., Saxena R. Role of remote sensing and GIS techniques for generation of groundwater prospect zones towards rural development--an approach. Int. J. Rem. Sens. 2003;24(5):993–1008. doi: 10.1080/01431160210144543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kabir M.D.H. Impact of climate change on agriculture especially in Jessore and Sathkhira districts according to farmers' mitigation strategies to climate change; evidence from farmer level data. J. Geogr. Nat. Disasters. 2015;5(3) doi: 10.4172/2167-0587.1000152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaliraj S., Chandrasekar N., Magesh N.S. Identification of potential groundwater recharge zones in Vaigai upper basin, Tamil Nadu, using GIS-based analytical hierarchical process (AHP) technique. Arabian J. Geosci. 2013;7 doi: 10.1007/s12517-013-0849-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasperson R.E. Risk Governance: the Articulation of Hazard, Politics and Ecology. 2015. Risk governance and the social amplification of risk: a commentary. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolli M.K., Opp C., Groll M. Mapping of potential groundwater recharge zones in the Kolleru lake catchment, India, by using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Nat. Resour. 2020;11(3) doi: 10.4236/nr.2020.113008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar T., Gautam A.K., Kumar T. Appraising the accuracy of GIS-based Multi-criteria decision making technique for delineation of Groundwater potential zones. Water Resour. Manag. 2014;28(13) doi: 10.1007/s11269-014-0663-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuriqi A., Ali R., Pham Q.B., Montenegro Gambini J., Gupta V., Malik A., Linh N.T.T., Joshi Y., Anh D.T., Nam V.T., Dong X. Seasonality shift and streamflow flow variability trends in central India. Acta Geophys. 2020;68(5):1461–1475. doi: 10.1007/s11600-020-00475-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magesh N.S., Chandrasekar N., Soundranayagam J.P. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in Theni district, Tamil Nadu, using remote sensing, GIS and MIF techniques. Geosci. Front. 2012;3(2) doi: 10.1016/j.gsf.2011.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maity D.K., Mandal S. Identification of groundwater potential zones of the Kumari river basin, India: an RS & GIS based semi-quantitative approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019;21(2):1013–1034. doi: 10.1007/s10668-017-0072-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mokarram M., Roshan G., Negahban S. Landform classification using topography position index (case study: salt dome of Korsia-Darab plain, Iran) Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2015;1(4):40. doi: 10.1007/s40808-015-0055-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukherjee I., Singh U.K. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in a drought-prone semi-arid region of east India using GIS and analytical hierarchical process techniques. Catena. 2020;194 doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2020.104681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukherjee P., Singh C.K., Mukherjee S. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in arid region of India-A remote sensing and GIS approach. Water Resour. Manag. 2012;26(9) doi: 10.1007/s11269-012-0038-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naghibi S., Pourghasemi H., Dixon B. GIS-based groundwater potential mapping using boosted regression tree, classification and regression tree, and random forest machine learning models in Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015;188 doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-5049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naghibi S., Pourghasemi H., Pourtaghi Z., Rezaei A. Groundwater qanat potential mapping using frequency ratio and Shannon's entropy models in the Moghan watershed, Iran. Earth Sci. Inf. 2014;8:171–186. doi: 10.1007/s12145-014-0145-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naghibi S.A., Moghaddam D.D., Kalantar B., Pradhan B., Kisi O. A comparative assessment of GIS-based data mining models and a novel ensemble model in groundwater well potential mapping. J. Hydrol. 2017;548:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2017.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naghibi Seyed Amir, Pourghasemi H.R., Abbaspour K. A comparison between ten advanced and soft computing models for groundwater qanat potential assessment in Iran using R and GIS. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018;131(3):967–984. doi: 10.1007/s00704-016-2022-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nair H., Joseph A., Gopinathan V.P. GIS Based landform classification using digital elevation model: a case study from two river basins of Southern Western Ghats, Kerala, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2018;4:1355–1363. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nair H., Padmalal D., Joseph A., Vinod P.G. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in river basins using geospatial tool – an example from southern western Ghats, Kerala, India. J. Geovisual. Spatial Anal. 2017;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nampak H., Pradhan B., Manap M.A. Application of GIS based data driven evidential belief function model to predict groundwater potential zonation. J. Hydrol. 2014;513:283–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.02.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nasir M.J., Khan S., Zahid H., Khan A. Delineation of groundwater potential zones using GIS and multi influence factor (MIF) techniques: a study of district Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018;77(10) doi: 10.1007/s12665-018-7522-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nowreen S., Newton I.H., Zzaman R.U., Islam A.K.M.S., Islam G.M.T., Alam M.S. Development of potential map for groundwater abstraction in the northwest region of Bangladesh using RS-GIS-based weighted overlay analysis and water-table-fluctuation technique. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021;193(1) doi: 10.1007/s10661-020-08790-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Owen S.M., Boissard C., Hagenlocher B., Hewitt C.N. Field studies of isoprene emissions from vegetation in the Northwest Mediterranean region. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1998;103(D19) doi: 10.1029/98JD01817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ozdemir A. GIS-based groundwater spring potential mapping in the Sultan Mountains (Konya, Turkey) using frequency ratio, weights of evidence and logistic regression methods and their comparison. J. Hydrol. 2011;411(3):290–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pal S., Kundu S., Mahato S. Groundwater potential zones for sustainable management plans in a river basin of India and Bangladesh. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;257 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pande C.B., Moharir K.N., Singh S.K., Varade A.M. An integrated approach to delineate the groundwater potential zones in Devdari watershed area of Akola district, Maharashtra, Central India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020;22(5):4867–4887. doi: 10.1007/s10668-019-00409-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parameswari K., Padmini T.K. Assessment of groundwater potential in Tirukalukundram block of southern Chennai Metropolitan Area. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018;20 doi: 10.1007/s10668-017-9952-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patra S., Mishra P., Mahapatra S.C. Delineation of groundwater potential zone for sustainable development: a case study from Ganga Alluvial Plain covering Hooghly district of India using remote sensing, geographic information system and analytic hierarchy process. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;172 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pinto D., Shrestha S., Babel M.S., Ninsawat S. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in the Comoro watershed, Timor Leste using GIS, remote sensing and analytic hierarchy process (AHP) technique. Appl. Water Sci. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1007/s13201-015-0270-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pourtaghi Z.S., Pourghasemi H.R. GIS-based groundwater spring potential assessment and mapping in the Birjand Township, southern Khorasan Province, Iran. Hydrogeol. J. 2014;22(3):643–662. doi: 10.1007/s10040-013-1089-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pradhan B. Groundwater potential zonation for basaltic watersheds using satellite remote sensing data and GIS techniques. Cent. Eur. J. Geosci. 2009;1:120–129. doi: 10.2478/v10085-009-0008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]