Abstract

Background

Pediatric low-grade gliomas (pLGGs) are the most common central nervous system tumor in children, characterized by RAS/MAPK pathway driver alterations. Genomic advances have facilitated the use of molecular targeted therapies, however, their long-term impact on tumor behavior remains critically unanswered.

Methods

We performed an IRB-approved, retrospective chart and imaging review of pLGGs treated with off-label targeted therapy at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s from 2010 to 2020. Response analysis was performed for BRAFV600E and BRAF fusion/duplication-driven pLGG subsets.

Results

Fifty-five patients were identified (dabrafenib n = 15, everolimus n = 26, trametinib n = 11, and vemurafenib n = 3). Median duration of targeted therapy was 9.48 months (0.12–58.44). The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year EFS from targeted therapy initiation were 62.1%, 38.2%, and 31.8%, respectively. Mean volumetric change for BRAFV600E mutated pLGG on BRAF inhibitors was −54.11%; median time to best volumetric response was 8.28 months with 9 of 12 (75%) objective RAPNO responses. Median time to largest volume post-treatment was 2.86 months (+13.49%); mean volume by the last follow-up was −14.02%. Mean volumetric change for BRAF fusion/duplication pLGG on trametinib was +7.34%; median time to best volumetric response was 6.71 months with 3 of 7 (43%) objective RAPNO responses. Median time to largest volume post-treatment was 2.38 months (+71.86%); mean volume by the last follow-up was +39.41%.

Conclusions

Our integrated analysis suggests variability in response by pLGG molecular subgroup and targeted therapy, as well as the transience of some tumor growth following targeted therapy cessation.

Keywords: low-grade glioma, pediatrics, targeted therapy, volumetric

Key Points.

Variability exists in response to targeted therapy.

Tumor stability can be achieved after cessation, and some immediate growth may be transient.

Volumetric analysis is feasible in assessing response to targeted treatment.

Importance of the Study.

While genomic profiling has significantly advanced our understanding pLGGs, there has been increasing interest in utilizing targeted agents. While these targeted therapies have shown promise in some contexts, there has been limited work with regard to how these agents alter tumor volume during treatment and following cessation of treatment. Moreover, survival outcomes based on both targeted therapy and genomic driver have been limited. Our study is the first to perform quantitative volumetric analysis of pLGGs focused on 4 targeted agents in relation to RAPNO/RANO criteria, with further integration of genomic driver information. Such analysis in larger cohorts of pLGG patients is needed to better understand how these targeted agents alter the natural history of pLGGs.

Pediatric low-grade gliomas (pLGGs) are the most common central nervous system tumor in children, accounting for approximately one-third of pediatric brain tumors.1 Prognosis for these tumors is generally excellent with 10-year overall survival (OS) between 85% and 96%.2–4 Standard treatment for children with progression or symptomatic tumors is complete surgical resection. However, for those patients where surgical resection is not possible or progression occurs despite resection, additional therapy may be required. Chemotherapy regimens most commonly used include the following: carboplatin and vincristine,5,6 vinblastine alone,7 or thioguanine, procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine (TPCV). The natural history of pLGGs is associated with excellent long-term survival, and a very low likelihood of malignant transformation.2 The excellent long-term survival of these patients supports the hypothesis that pLGGs become quiescent in the transition from childhood to adulthood.2,8,9 One-year, 3-year, and 5-year event-free survival (EFS) from a retrospective study of low-grade glioma patients receiving vinblastine and carboplatin were 69.6%, 39.4%, and 34.5% respectively.10 A total of 5-year EFS from the COG vincristine/carboplatin versus TPCV trial for all patients was 45% ± 3.2%. For the vincristine/carboplatin regimen, 5-year EFS was 39% ± 4%, while for the TPCV regimen, 5-year EFS was 52% ± 5%.11

There have been significant advances in understanding the genomic landscape of pLGGs. Genomic profiling efforts have identified a distinct set of driver alterations that lead to activation of the MAPK pathway, including BRAF V600E mutation, BRAF duplications12–14 including KIAA1549-BRAF,15 MYBL1,16 MYB-QKI,17 FGFR1, NTRK2,18 FGFR3, RAF1 fusions, and germline NF1.

Given this improved understanding of the genomic alterations that drive pLGGs, there has been increasing interest in the use of targeted agents, specifically BRAF19–24 and MEK inhibitors.22,25–30 Direct targeting of BRAF using type I RAF inhibitors,31,32 including dabrafenib and vemurafenib, is a promising approach, particularly in patients harboring BRAFV600E mutations. Type II RAF inhibitors33 can also be used to target BRAF. The mTOR inhibitor everolimus has also been evaluated in patients with recurrent, progressive pLGGs34 and in patients with NF1.35,36 Importantly, type I RAF inhibitors can lead to increased ERK signaling in wild-type BRAF and non-V600E contexts. When bound to RAF, these drugs can activate the catalytic domain of the RAF binding partner, resulting in paradoxical activation.37,38

However, the use of these novel targeted agents is not without side effects, with BRAF, MEK, and mTOR inhibition leading to toxicity profiles including rashes, skin infections, and cardiac dysfunction.25 Importantly, given the natural history of pLGGs is known to have excellent long-term survival excellent survival, careful consideration is needed with regards to how different treatments may alter the course of the disease. Limited data are available on the effect of these targeted agents on the natural history of pLGGs.28,39–41 Moreover, the occurrence of rebound growth following cessation of the drug has been noted with other targeted agents including imatinib in adult42,43 and pediatric patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) as well as mTOR inhibition in patients with tuberous sclerosis including SEGAs and angiomyolipomas.

Furthermore, challenges exist to how we define and interpret pLGG radiographic response. pLGGs often have complex shapes and components, making accurate assessment critically important. RANO criteria possess major limitations for pLGGs, including utilization of percent change in contrast enhancement rather than T2/FLAIR and its requirement of more than 50% change in area as response. As such, there remains no published evidence for RANO’s utility in predicting pLGG survival outcomes.44 Recognizing the need, the Response Assessment in Pediatric Neuro-Oncology pLGG working group created consensus definitions and imaging standards for pLGG on MRI in 2020.45 However the criteria are yet to be validated, and practice decisions around stopping and re-starting therapy outside of clinical trials remain incredibly varied.

Thus, a more comprehensive characterization of pLGGs using both clinical and radiographic data on and following the cessation of targeted agents is needed. We sought to review the clinical course of children during and following treatment with targeted agents, with the goal of describing a historical cohort of children with the accompanying genomic correlates. Given the promising phase 2 trial results of BRAF fusion altered pLGG to MEK inhibitors26,46 (NCT01089101) and BRAFV600E mutated pLGG to BRAF inhibitors20 (NCT01677741), we chose a sub-cohort of patients with BRAFV600E mutations treated with BRAF inhibitors and patients with BRAF fusion/duplication alterations treated with MEK inhibitors to perform detailed response analysis, including volume and area comparisons. Herein, we summarize our experience treating patients with pediatric low-grade glioma with targeted therapy off-label at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center over the past decade.

Methods

Patient Selection

Patients treated with targeted agents for low-grade glioma between 2010 and 2020 were identified using an institutional database. Patients were deemed eligible in this retrospective study if they received one of the following targeted agents: Dabrafenib, everolimus, trametinib, or vemurafenib, and were treated at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. Patients were excluded if they were treated in clinical trials to avoid duplicate reporting of data. The study was approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board with the waiver of consent.

Clinical and Genomic Features

Clinical data were extracted from the medical records and included demographic information, clinical features, histopathological features, treatment regimens, clinical course, duration of follow-up, and survival outcomes. Clinical progression was defined as symptomatic progression based on review of clinical documentation from the patient’s primary oncologist. Radiographic progression was defined as progression based on MRI reports and/or interval growth instigating a new clinical intervention. Information regarding driver mutation was obtained from next-generation sequencing (n = 33), fluorescent in situ hybridization for BRAF rearrangements (n = 30), or ddPCR for BRAF V600E mutations (n = 6). Next-generation sequencing utilized the Brigham and Women’s targeted exome sequencing assay (Oncopanel), which interrogates the exons of 447 genes and 191 introns across 60 genes. Structural rearrangements were evaluated with BreaKmer analysis as previously described.

Volumetric and Area Analysis

For all qualified studies, 2D measurements were performed according to RANO and RAPNO criteria by a board-certified pediatric neuroradiologist (7 years of radiology experience, JJC) in a blinded fashion. The radiologist was blinded to the patient history, molecular alteration, and targeted agent. During this sequential review, the best sequences for volumetric analysis were determined (eg, T2, FLAIR, Gadolinium-enhanced T1). Volumetric segmentation of tumors was subsequently performed at the Computational Research Laboratory at Boston Children’s Hospital utilizing the optimal sequences selected for volumetric analysis. All segmentations were performed utilizing ITK-SNAP software (3.8.0). The segmented volume contours were then edited manually with the assistance of the same pediatric neuroradiologist to remove pixels for nontumor regions (eg, surgical cavity, marginal gliosis, and internal hemorrhage). The tumor volume (in cubic centimeters) was calculated by multiplying the total pixel counts with pixel volume. The date of the baseline MRI scan was the closest scan 6 months prior to targeted therapy for patients who had no previous therapy or the first scan after the preceding treatment ended. The date of the last scan was the last scan prior to the start of subsequent therapy or the last available scan for patients who had no subsequent therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with P-values reported using the log-rank test. PFS following initial diagnosis was defined as time from the initial diagnosis to disease progression. PFS following the targeted agent was defined as time from initiation of the targeted agent to disease progression. OS following initial diagnosis was defined as time from initial diagnosis to date of most recent encounter. Duration of targeted therapy was defined as time from initiation of the targeted agent to time of discontinuation. For patients remaining on targeted agent, duration of targeted therapy was defined as time from initiation to date of most recent encounter. Statistical computations were performed using GraphPad Prism v9.1.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego CA). For all statistical tests, P-values were 2-sided with P < .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Fifty-five patients with pediatric low-grade glioma receiving targeted therapy off study were identified. 15 patients received dabrafenib, 26 received everolimus, 11 received trametinib, and 3 received vemurafenib (Figure 1A). The median age at initial diagnosis was 4.42 years (range: 0.13–25.84). None of these patients had metastatic disease. Patient characteristics at diagnosis are summarized in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

(A) Number of patients who received dabrafenib (15/55), everolimus (26/55), trametinib (11/55), and vemurafenib. (B) Swimmer’s plot showing all 55 patients. Each bar indicates a different patient, colored by the targeted agent (dabrafenib red, everolimus orange, trametinib green, vemurafenib blue). (C) The X-axis indicates time in years from initial diagnosis to date of last contact (or date of death if patient is deceased). White circle indicates targeted agent initiation, the purple dot indicates targeted agent cessation (if drug was discontinued), and black dot indicates first progression from targeted agent cessation.

Genomic Characteristics

A total of 53 out of 55 patients had diagnostic tissue sent for genomic analysis. Two patients never had surgery. Genomic analysis was highly heterogeneous and included fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for BRAF (n = 30), OncoPanel (n = 33), and ddPCR (n = 6). In total, 19/55 (35%) pLGGs in our cohort were found to have BRAF V600E mutation, while BRAF fusion/duplications accounted for an additional 19/55 (35%) alterations. We were unable to identify a driver alteration in 8 patients (2 of these 8 patients never had surgery). A total of 8 patients were found to have other alterations, including MYB-QKI fusion, FGFR1 internal tandem duplication, FGFR3-TACC3, NF1, CUX1-RAF1 fusion, and SRGAP3-RAF1 fusion (Figure 1B).

Of patients identified to harbor BRAF V600E mutations (n = 19), 18/19 (95%) received Type I BRAF inhibitors as the first targeted agent with the majority receiving dabrafenib (15/19) and a few patients (3/19) receiving vemurafenib. One patient with BRAF V600E received trametinib, but subsequently, after cessation of trametinib, the patient was ultimately initiated on dabrafenib. Patients with BRAF fusions were most likely to have received everolimus and trametinib due to the risk of paradoxical activation with Type I BRAF inhibitors.

Treatment Prior to Targeted Therapy

Table 1 details the treatment preceding targeted therapy. Median lines of therapy prior to the initiation of targeted therapy including chemotherapy and radiation was one (range 0–6); only 7% received gross total resection (4/55). The median time from diagnosis to targeted therapy initiation was 4.69 years (0.10–23.77).

Table 1.

Treatment Descriptive Characteristics

| n = 55 | |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | |

| Median (years) | 4.42 |

| Range (years) | 0.13–25.84 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 25 (45%) |

| Male | 30 (55%) |

| Pathology (histology) | |

| WHO Grade I | 23 (42%) |

| WHO Grade II | 10 (18%) |

| Equivocal | 22 (40%) |

| Tumor location | |

| Posterior fossa | 16 (29%) |

| Hypothalamus/optic pathway | 22 (40%) (43%) |

| Supratentorial | 11 (20%) |

| Cervicomedullary | 3 (5.5%) |

| Spine | 3 (5.5%) |

| Metastasis | |

| Metastatic | 0 (0%) |

| Non-metastatic | 55 (100%) |

| Surgery extent prior to targeted therapy | |

| Gross total resection | 4 (7%) |

| Subtotal resection | 29 (53%) |

| Biopsy | 18 (33%) |

| No surgery | 4 (7%) |

| Lines of therapy preceding targeted therapy | |

| 0 | 16 (29%) |

| 1 | 16 (29%) |

| 2 | 5 (9%) |

| 3 | 6 (11%) |

| 4 | 6 (11%) |

| 5 | 3 (5.5%) |

| 6 | 3 (5.5%) |

| Median time from diagnosis to targeted therapy initiation | 4.69 years |

| Rationale for initiation of targeted therapy | |

| Clinical progression | 4 (7%) |

| Radiographic progression | 29 (53%) |

| Both clinical and radiographic progression | 22 (40%) |

| Median targeted therapy duration | 0.79 years |

| Reason for discontinuation | |

| Planned end of therapy | 14 (25%) |

| Toxicity | 8 (14.5%) |

| Progression | 19 (34.5%) |

| N/A | 14 (25%) |

| Treatment following discontinuation | |

| None | 29 (53%) |

| Chemotherapy | 7 (13%) |

| Targeted therapy | 21 (38%) |

| Anti-angiogenic therapy | 3 (5.5%) |

| Median time to next line of therapy post-targeted agent | 0.26 years |

| Median follow-up from initial diagnosis | 9.16 years |

| Median follow-up from targeted therapy initiation | 2.50 years |

| Range of follow-up from targeted therapy initiation | 0.003–12.39 years |

Rationale Around the Initiation and Discontinuation of Targeted Therapy

The most common rationale for the initiation of targeted therapy was the presence of both clinical and radiographic progression (22/55; 40%) (Table 1). The median duration of targeted therapy was 0.79 years (0.01–4.87) (Figure 1C). The median duration for dabrafenib treatment was 1.14 years (0.53–2.13), for everolimus treatment was 0.75 years (0.08–4.87), for trametinib treatment was 0.39 years (0.01–0.47), and for vemurafenib treatment was 0.92 years (0.67–1.06). Of the 55 patients who received targeted therapy, 41 patients had discontinuation of therapy. Of those 41, toxicity was the cause of discontinuation in 33% (3/9), 33% (1/3), 33% (2/6), and 9% (2/23) of dabrafenib, vermurafenib, trametinib, and everolimus treated patients, and progression the cause of discontinuation in 11% (1/9), 0% (0/3), 67% (4/6), and 61% (14/23) respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

Treatment After Targeted Therapy

Post-treatment details are provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. Of the 41 patients who discontinued the first line of targeted therapy, 38% (n = 21) received targeted therapy, 13% (n = 7) received chemotherapy, and 5.5% (n = 3) received anti-angiogenic therapy. The median time to the next line of therapy was 0.26 years.

Survival Outcomes From Initiation of Targeted Therapy

A total of 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year PFS from initiation of targeted therapy for the entire cohort was 64.1% (95% CI 49.6%–75.4%), 38.2% (95% CI 23.3%–53.0%), and 31.8% (95% CI 16.1%–48.8%), respectively. In total, 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival (OS) from initiation of targeted therapy was 96.2% (95% CI 85.7%–99.0%), 96.2% (95% CI 85.7%–99.0%), and 92.2% (95% CI 76.0%–97.6%) (Figure 2A). Only 2 of the 4 patients who passed away within our cohort had autopsies, therefore malignant transformation could only be definitively excluded as the cause of death in those 2 cases. None of these 4 patients was receiving treatment at the time of death. One patient died from cerebral edema secondary to tumor growth, brainstem compression, and venous congestion with autopsy at time of death consistent with pLGG. One patient died from worsening tumor burden with autopsy at time of death also consistent with pLGG. All 4 patients received everolimus in our retrospective study, and 3 of the 4 patients had multiple lines of therapy prior to receiving their first targeted agent (3, 5, and 6). One of these patients had no surgery prior to initiation of targeted treatment, one had a biopsy only, and the maximal surgical intervention prior to targeted therapy for the other 2 patients was STR.

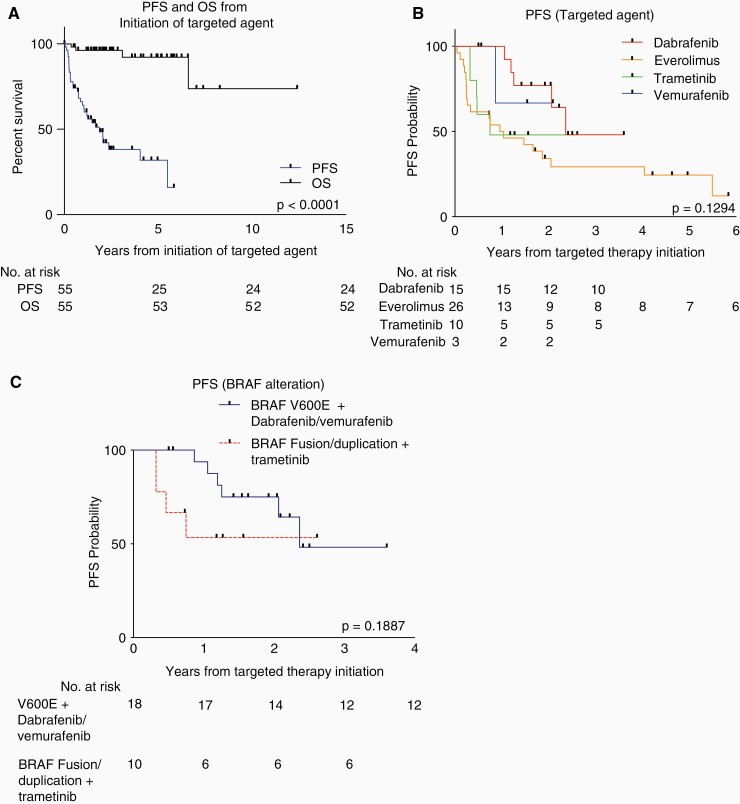

Figure 2.

(A) Progression-free survival (PFS) and OS from initiation of targeted agent. (B) PFS from initiation of targeted agent based on targeted agent received. (C) PFS from initiation of targeted agent based on driver alteration (BRAFV600E treated with BRAF inhibition and BRAF fusion/duplication treated with trametinib).

When stratified by targeted agent, PFS trended toward significance (Figure 2B, P = .1294).

For patients receiving dabrafenib, 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year PFS were 100%, 48.1% (95 % CI 13.7%–76.4%), and 48.1% (95 % CI 13.7%–76.4%); while for patients receiving vemurafenib, 1-year, 3-year, and 5- year PFS were 66.7% (95% CI 5.4%– 4.5%). Patients receiving everolimus had 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year PFS of 50.0% (95% CI 29.9%–67.6%), 29.3% (95% CI 13.1%–47.6%), and 24.4% (95% CI 9.7%–42.8%), respectively; while for patients receiving trametinib, 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year PFS were 48.0% (95% CI 16.1%–74.5%).

For patients with BRAFV600E mutations receiving dabrafenib or vemurafenib, 1-year and 3-year PFS were 93.8% (95% CI 63.2%–99.1%) and 48.2% (95% CI 14.8%–75.7%), while for patients with BRAF fusion/duplications receiving trametinib, 1-year and 3-year PFS were both 53.3% (95% CI 17.7%–79.6%) (Figure 2C, P = .1887).

Radiographic Volumetric and Response Analysis During and Following Targeted Therapy

A sub-cohort of patients with BRAFV600E mutations treated with dabrafenib (Figure 3A) or vemurafenib (Figure 3B) and patients with BRAF fusion/duplication alterations treated with trametinib (Figure 3C) had detailed radiologic analysis by volume and area (Supplementary Figure 1) using both RANO and RAPNO criteria (Table 2). Differences in tumor size (%) by area and volume are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Volumetric analysis of (A) BRAFV600E tumors treated with dabrafenib and (B) vemurafenib as well as (C) BRAF fusion/duplications treated with trametinib. Volumes are shown as normalized to the first radiographic timepoint, defined as the closest scan to 6 months prior to initiation of targeted therapy or the first scan after the preceding treatment ended (for patients who received prior therapy). The white open circle indicates the scan date prior to the initiation of therapy. The red-filled circle indicates the first scan date following cessation of therapy.

Table 2.

RAPNO/RANO Responses and Volumetric Measurements

| Case | Targeted Agent | RAPNO Best Response During Therapy | RANO Best Response During Therapy | Area Best Response During Therapy (Change from the Initial Scan) | Volume Best Response During Therapy (Change from Initial Scan) | RAPNO Response After Cessation | RANO Response After Cessation | Area After Cessation (Change from Initial Scan) | Volume after Cessation (Change from Initial Scan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Trametinib | Partial response | Partial response | −50% | −76% | Stable disease | Stable disease | 0% | 5% |

| 5 | Trametinib | Progressive disease | Progressive disease | 42% | 137% | Progressive disease | Progressive disease | 79% | 144% |

| 6 | Trametinib | Progressive disease | Progressive disease | 422% | 272% | Progressive disease | Progressive disease | 850% | 1600% |

| 7 | Trametinib | Progressive disease | Progressive disease | 25% | −80% | Partial response | Partial response | −53% | −90% |

| 11 | Trametinib | Stable disease | Stable disease | −21% | −32% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 12 | Trametinib | Minor response | Stable disease | −29% | −8% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 18 | Trametinib | Progressive disease | Progressive disease | 34% | 69% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | Dabrafenib | Partial response | Partial response | −50% | −14% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | Dabrafenib | Partial response | Partial response | −65% | −88% | Partial response | Partial response | −71% | −87% |

| 8 | Dabrafenib | Partial response | Partial response | −59% | −39% | Minor response | Stable disease | −31% | −31% |

| 10 | Dabrafenib | Stable disease | Stable disease | −12% | −45% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 14 | Dabrafenib | Minor response | Stable disease | −47% | −66% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 16 | Dabrafenib | Progressive disease | Progressive disease | 28% | 39% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 17 | Dabrafenib | Major response | Partial response | −88% | −91% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 19 | Dabrafenib | Minor response | Stable disease | −39% | −89% | Minor response | Stable disease | −39% | −89% |

| 20 | Dabrafenib | Major response | Partial response | −80% | −96% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 9 | Vemurafenib | Minor response | Stable disease | −30% | −21% | Stable disease | Stable disease | 0% | 2% |

| 13 | Vemurafenib | Minor response | Stable disease | −38% | −55% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 15 | Vemurafenib | Stable disease | Stable disease | −10% | 5% | Stable disease | Stable disease | 12% | 0 |

Amongst patients with BRAFV600E mutations treated with dabrafenib or vemurafenib, 92% (11/12) showed a decrease in volume during treatment, while 75% (9/12) had an objective response by RAPNO criteria and 42% (5/12) by RANO criteria. There were 17% (2) major, 25% (3) partial, and 33% (4) minor RAPNO responses and 42% (5) partial RANO responses. The median time to best response (lowest volume) from initiation of targeted agent was 8.28 months (0.69 years, range 0.22–1.80 years or 2.64–21.63 months). The mean volumetric change was a reduction of 54.11% when compared to the volume at the time of targeted therapy initiation.

Of the BRAFV600E mutated pLGG patients who discontinued BRAF inhibition (n = 7), post-cessation tumor area and volumes were available for 5, with a median follow-up of 0.90 years post-cessation (range 0.21–3.24 years). Using the initial baseline scan for comparison, at last, off-therapy follow-up there were still 40% (2) minor, and 20% (1) partial RAPNO responses, and 20% (1) partial RANO responses. None of the 5 patients had progressive disease by either criterion. Of these 5 patients with post-cessation tumor volumes, the median time to the largest post-cessation volume was 0.24 years (2.86 months). Compared to volume at the time of cessation, the largest post-cessation volume was a mean increase of 13.49% (n = 5). At last, follow-up, the volumetric change was a mean reduction of 14.02% (n = 5).

Amongst patients with BRAF fusion/duplications treated with trametinib, 43% (3/7) showed a decrease in volume during treatment, while 43% (3/7) had objective response by RAPNO criteria and 14% (1/7) by RANO criteria. There were 14% (1) minor and 29% (2) partial RAPNO responses, and 14% (1) partial RANO responses. One patient (Case 7) had such a short duration of treatment (5 days) that meaningful volumetric analysis could not be assessed. The median time to best response (lowest volume) from initiation of targeted agent for 3/7 patients was 6.71 months (0.56 years, range 0.04–0.57 years or 0.46–6.87 months). Mean volumetric change for 6/7 patients was an increase of 7.34% compared to the volume at the time of targeted therapy initiation (Figure 3).

Of the BRAF fusion/duplication pLGG patients who discontinued MEK inhibition (n = 5), post-cessation tumor areas and volumes were available for 4 out of 5 of these patients, with median follow-up of 0.43 years post-cessation (range 0.07–0.99 years). Using the initial baseline scan for comparison, at last, off-therapy follow-up there was a 25% (1)_partial RAPNO response, and 25% (1) partial RANO response. Fifty percent of patients had progressive disease by both RAPNO and RANO criteria. The median time to the largest post-cessation volume was 0.20 years (2.38 months). Compared to volume at the time of cessation, the largest post-cessation volume was a mean increase of 71.86% (n = 4). At last, follow-up, the volumetric change was a mean increase of 39.41% (n = 4). Of note, 2 of these 4 patients had reductions in tumor volume after cessation (Case 5, 7) (Figure 3).

Discussion

The natural history of pediatric low-grade gliomas shows excellent long-term survival outcomes, however, survivors face long-term neurocognitive, psychological, and functional morbidities as a result of their tumor and treatment experiences. Identification of molecular alterations has led to targeting the MAPK pathway as a promising opportunity for treatment, should the strategy preserve the natural history while reducing long-term morbidity. We, therefore, sought to better understand the clinical and radiographic outcomes of pLGG patients following treatment with targeted therapies at our institution.

Given our patients’ prior treatment experience, known institutional practice over the preceding decade, and the relatively lower 5-year OS of our cohort, we speculate our review represents more aggressive pLGG than the treatment-naive pLGG treated in prior chemotherapy studies.10,11 Within our cohort, for patients with BRAF fusion/duplications receiving trametinib, 1-year and 3-year PFS were both 53.3%, slightly lower than the 2-year PFS in both phase I25 (69 ± 9.8%) and phase II26 (73.8 ± 9.3%) selumetinib trials. Our 3-year PFS of 48.2% for BRAFV600E mutant pLGG was similar to prior multi-institutional retrospective series using BRAF inhibition.47 These survival outcomes, in light of our cohort’s clinical and treatment characteristics, lend further support for the use of MEK inhibition for BRAF fusion/duplication pLGG and BRAF inhibition for BRAFV600E mutant pLGG to provide a durable response.

While not chosen for sub-cohort response analysis given the still unknown predictive molecular target population, the 3- and 5-year PFS of pLGG patients (29.3% and 24.4%, respectively) treated on everolimus were not dissimilar from the Pediatric Oncology Experimental Therapeutics Consortium phase 2 trial results for recurrent pLGG34 (NCT00782626). Results from the Pacific Pediatric Neuro-Oncology phase 2 trial are pending, which may shed light on the predictive molecular driver(s) (NCT01734512). No longer in monotherapy trial testing, everolimus is currently being studied in combination with trametinib for recurrent pLGG (NCT04485559), and its potential to mitigate resistance as a combinatorial agent may still be determined.

In patients with BRAFV600E mutant pLGGs, we found evidence of a dramatic response to BRAF inhibition consistent with prior retrospective analyses.47–49 The median time to best volume response was 8.28 months with a wide range of 0.22–1.80 years, lending validity to the common 2-year trial duration design. We were able to provide further novel descriptions of BRAFV600E mutant pLGG behavior after BRAF inhibitor cessation. While rebound growth was evident 2 months following cessation (increase of 13.49%), at last follow-up without further treatment there was actually a reduction in tumor volume (decrease of 14.02%), suggesting a judicious approach should be taken in this population when deciding on conditions for re-starting therapy.

In our cohort, patients with BRAF fusions/duplications treated with trametinib showed a less dramatic response to MEK inhibition, similar to prior reports.22,28,41 However, in light of the median duration of treatment (0.39 years) compared to the median time to best response (0.56 years), premature discontinuation of treatment likely limited our findings. Growth was evident soon after cessation with the largest volume of growth occurring 2.38 months after stopping therapy (vs. 2.86 months in BRAFV600E cohort). Similar to the BRAFV600E cohort, while the largest post-cessation volume reached a mean increase of 71.86%, without further treatment the volumetric change eventually reduced to a mean increase of 39.41%, at the last, follow-up. It is likely these findings represent a mixed picture of true progression and transient growth, that is pseudoprogression. We are the first to describe the potential occurrence of post-targeted therapy pseudoprogression in the pLGG population, and more robust datasets are required to determine the true incidence and risk factors.

The post-treatment growth behavior we found for both BRAFV600E and BRAF fusion/duplication pLGG sub-cohorts would have been difficult to recognize had we limited our analysis to RAPNO/RANO criteria. Recent comparisons of volumetric and 2D tumor assessments found discordant responses in 20% of 70 pLGG patients,50 lending concern for the accuracy of the 2D assessment. While comparing response classifications between methodologies was beyond the scope of this study, we were able to show both volume and area change on and after treatment for a sub-cohort of patients. Of note, 13% (2/15) had contrasting positive and negative size differences based on area versus volume calculation. Of particular concern, case 7 met the criteria for progressive disease by RANO and RAPNO criteria, however, had an 80% volume reduction. Furthermore, 17% of BRAFV600E mutated pLGG on BRAF inhibition had on therapy volume reduction without meeting minor response criteria, while there was no discrepancy in the BRAF fusion/duplication cohort. On therapy, RANO criteria largely underestimated objective response rate compared to RAPNO criteria for both sub-cohorts (41% vs. 75% for BRAFV600E mutated pLGG on BRAF inhibitors, 14% vs. 43% for BRAF fusion/duplication pLGG on trametinib). As RANO remains the standard response criteria used for trial testing without proven utility, it is imperative for RAPNO criteria to be incorporated into all future pLGG trials. Then, should RAPNO measures be prospectively validated as correlative to PFS, their accuracy in comparison to the more labor-intensive volumetric segmentation will become of less concern.

There are several notable limitations of this retrospective, single-institution analysis. The response analysis was performed was on a small cohort of patients. Not all patients had cessation of targeted therapy, therefore it was difficult to comprehensively evaluate post-treatment growth. Given the nature of our methods, the timing of scans in relation to treatment was not uniform across the cohort. To most accurately determine pLGG targeted therapy response, consensus must be reached regarding the timing and frequency of scans, as well as chosen MRI comparisons and response criteria. As the targeted therapy landscape evolves, for whom, when, and how long to deliver newer agents such as type II pan-RAF inhibitors or combinatorial MAPK inhibitors is becoming of increasing interest, and was beyond the scope of this study. Integrating genomic, clinical, and response analysis will be critical in the future to better understand the appropriate duration of treatment, the timing of rebound growth after cessation, and the use of targeted agents in relation to specific molecular alterations. Larger studies of this type will be necessary for a comprehensive understanding of the natural history of pLGGs in the era of targeted therapy.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- GTR

gross total resection

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- pLGG

pediatric low-grade glioma

- STR

subtotal resection

Contributor Information

Jessica W Tsai, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Jungwhan John Choi, Department of Radiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Hakim Ouaalam, Department of Radiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Efrain Aguilar Murillo, Department of Radiology, Division of Neuroradiology and Neurointervention, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Kee Kiat Yeo, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Jayne Vogelzang, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Cecilia Sousa, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Jared K Woods, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Keith L Ligon, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Department of Pathology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston Massachusetts, USA; Department of Pathology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Simon K Warfield, Department of Radiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Pratiti Bandopadhayay, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Tabitha M Cooney, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Funding

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the following funding sources: National Institutes of Health [R01 LM013608 to S.K.W; T32 CA251062 to J.K.W.; R01CA215489, P50CA165962, U19CA264504 to K.L.L.], PLGA Fund at PBTF (P.B. and K.L.L.), Team Jack Foundation (P.B. and K.L.L.), and the PLGA Program at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (P.B. and K.L.L.).

Authorship statement

Extraction of clinical data: JWT, JV, CS, JKW. Clinical data analysis: JWT. Volumetric analysis: JJC, HO, EAM, SKW. Manuscript writing and editing: JWT, JJC, HO, EAM, KKY, JV, CS, JKW, KLL, SKW, PB, TMC. Supervision of the overall study: TMC.

Conflict of interest statement

PB receives grant funding from Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research, and has received funding from Deerfield Therapeutics. She has also served as a consultant for QED Therapeutics. TC has served as a consultant for Taconic Research LLC. KLL receives grant funding from BMS and Lilly and receives consulting fees from Travera, Integragen, BMS, and holds equity in Travera.

References

- 1. Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012-2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019; 21(Suppl 5):v1–v100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bandopadhayay P, Bergthold G, London WB, et al. Long-term outcome of 4,040 children diagnosed with pediatric low-grade gliomas: an analysis of the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014; 61(7):1173–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ostrom QT, de Blank PM, Kruchko C, et al. Alex’s lemonade stand foundation infant and childhood primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007-2011. Neuro Oncol. 2015; 16(Suppl 10):x1–x36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood central nervous system malignancies in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009; 101(13):946–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gnekow AK, Kaatsch P, Kortmann R, Wiestler OD. HIT-LGG: effectiveness of carboplatin-vincristine in progressive low-grade gliomas of childhood--an interim report. Klin Padiatr. 2000; 212(4):177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gnekow AK, Kortmann RD, Pietsch T, Emser A. Low grade chiasmatic-hypothalamic glioma-carboplatin and vincristin chemotherapy effectively defers radiotherapy within a comprehensive treatment strategy -- report from the multicenter treatment study for children and adolescents with a low grade glioma -- HIT-LGG 1996 -- of the Society of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology (GPOH). Klin Padiatr. 2004; 216(6):331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lassaletta A, Scheinemann K, Zelcer SM, et al. Phase II weekly vinblastine for chemotherapy-naive children with progressive low-grade glioma: a Canadian pediatric brain tumor consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2016; 34(29):3537–3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Blank P, Bandopadhayay P, Haas-Kogan D, Fouladi M, Fangusaro J. Management of pediatric low-grade glioma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019; 31(1):21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaw EG, Wisoff JH. Prospective clinical trials of intracranial low-grade glioma in adults and children. Neuro Oncol. 2003; 5(3):153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nellan A, Wright E, Campbell K, et al. Retrospective analysis of combination carboplatin and vinblastine for pediatric low-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2020; 148(3):569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ater JL, Zhou T, Holmes E, et al. Randomized study of two chemotherapy regimens for treatment of low-grade glioma in young children: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30(21):2641–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pfister S, Janzarik WG, Remke M, et al. BRAF gene duplication constitutes a mechanism of MAPK pathway activation in low-grade astrocytomas. J Clin Invest. 2008; 118(5):1739–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacob K, Albrecht S, Sollier C, et al. Duplication of 7q34 is specific to juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas and a hallmark of cerebellar and optic pathway tumours. Br J Cancer. 2009; 101(4):722–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yu J, Deshmukh H, Gutmann RJ, et al. Alterations of BRAF and HIPK2 loci predominate in sporadic pilocytic astrocytoma. Neurology. 2009; 73(19):1526–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, et al. Tandem duplication producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas. Cancer Res. 2008; 68(21):8673–8677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ramkissoon LA, Horowitz PM, Craig JM, et al. Genomic analysis of diffuse pediatric low-grade gliomas identifies recurrent oncogenic truncating rearrangements in the transcription factor MYBL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110(20):8188–8193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bandopadhayay P, Ramkissoon LA, Jain P, et al. MYB-QKI rearrangements in angiocentric glioma drive tumorigenicity through a tripartite mechanism. Nat Genet. 2016; 48(3):273–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones DT, Hutter B, Jager N, et al. Recurrent somatic alterations of FGFR1 and NTRK2 in pilocytic astrocytoma. Nat Genet. 2013; 45(8):927–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lassaletta A, Guerreiro Stucklin A, Ramaswamy V, et al. Profound clinical and radiological response to BRAF inhibition in a 2-month-old diencephalic child with hypothalamic/chiasmatic glioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016; 63(11):2038–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hargrave DR, Bouffet E, Tabori U, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabrafenib in pediatric patients with braf v600 mutation-positive relapsed or refractory low-grade glioma: results from a phase I/IIa study. Clin Cancer Res. 2019; 25(24):7303–7311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kieran MW, Geoerger B, Dunkel IJ, et al. A Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of oral dabrafenib in children and adolescent patients with recurrent or refractory BRAF V600 mutation-positive solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2019; 25(24):7294–7302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kondyli M, Larouche V, Saint-Martin C, et al. Trametinib for progressive pediatric low-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2018; 140(2):435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kondyli ME, Saint-Martin C, Farmer JP, et al. PDCT-08. Trametinib and dabrafenib for refractory/inoperable pediatric low grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2017; 19(6):185. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sievert AJ, Lang SS, Boucher KL, et al. Paradoxical activation and RAF inhibitor resistance of BRAF protein kinase fusions characterizing pediatric astrocytomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110(15):5957–5962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Banerjee A, Jakacki RI, Onar-Thomas A, et al. A phase I trial of the MEK inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244) in pediatric patients with recurrent or refractory low-grade glioma: a Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium (PBTC) study. Neuro Oncol. 2017; 19(8):1135–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fangusaro J, Onar-Thomas A, Poussaint TY, et al. A phase II trial of selumetinib in children with recurrent optic pathway and hypothalamic low-grade glioma without NF1: a Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium study. Neuro Oncol. 2021; 23(10):1777–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fangusaro JO, Poussaint TY, Wu S, et al. LGG-08. A phase II prospective study of selumetinib in children with recurrent or refractory low-grade glioma (LGG): a Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium (PBTC) study. Neuro Oncol. 2017; 19(4):34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Manoharan N, Choi J, Chordas C, et al. Trametinib for the treatment of recurrent/progressive pediatric low-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2020; 149(2):253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bouffet EK, Hargrave D, Roberts S, et al. LGG-46. Trametinib therapy in pediatric patients with low-grade gliomas (LGG) with BRAF gene fusion; a disease-specific cohort in the first pediatric testing of trametinib. Neuro Oncol. 2018; 20(2):114. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Robison NP, Malvar J, Gruber-Filbin M, et al. LGG-44. A phase I dose escalation trial of the MEK1/2 inhibitor MEK162 (binimetinib) in children with low-grade gliomas and other Ras/Raf pathway-activated tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2018; 20(2):114. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holderfield M, Merritt H, Chan J, et al. RAF inhibitors activate the MAPK pathway by relieving inhibitory autophosphorylation. Cancer Cell. 2013; 23(5):594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Holderfield M, Nagel TE, Stuart DD. Mechanism and consequences of RAF kinase activation by small-molecule inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2014; 111(4):640–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun Y, Alberta JA, Pilarz C, et al. A brain-penetrant RAF dimer antagonist for the noncanonical BRAF oncoprotein of pediatric low-grade astrocytomas. Neuro Oncol. 2017; 19(6):774–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wright KD, Yao X, London WB, et al. A POETIC Phase II study of continuous oral everolimus in recurrent, radiographically progressive pediatric low-grade glioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021; 68(2):e28787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ullrich NJ, Prabhu SP, Packer RJ, et al. Visual outcomes following everolimus targeted therapy for neurofibromatosis type 1-associated optic pathway gliomas in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021; 68(4):e28833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ullrich NJ, Prabhu SP, Reddy AT, et al. A phase II study of continuous oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus for recurrent, radiographic-progressive neurofibromatosis type 1-associated pediatric low-grade glioma: a Neurofibromatosis Clinical Trials Consortium study. Neuro Oncol. 2020; 22(10):1527–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010; 464(7287):431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, Shokat KM, Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010; 464(7287):427–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller C, Guillaume D, Dusenbery K, Clark HB, Moertel C. Report of effective trametinib therapy in 2 children with progressive hypothalamic optic pathway pilocytic astrocytoma: documentation of volumetric response. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017; 19(3):319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Paul MR, Pehlivan KC, Milburn M, et al. Trametinib-based treatment of pediatric CNS tumors: a single institutional experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020; 42(8):e730–e737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Selt F, van Tilburg CM, Bison B, et al. Response to trametinib treatment in progressive pediatric low-grade glioma patients. J Neurooncol. 2020; 149(3):499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mahon FX, Rea D, Guilhot J, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010; 11(11):1029–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thielen N, van der Holt B, Cornelissen JJ, et al. Imatinib discontinuation in chronic phase myeloid leukaemia patients in sustained complete molecular response: a randomised trial of the Dutch-Belgian Cooperative Trial for Haemato-Oncology (HOVON). Eur J Cancer. 2013; 49(15):3242–3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pope WB, Hessel C. Response assessment in neuro-oncology criteria: implementation challenges in multicenter neuro-oncology trials. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011; 32(5):794–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fangusaro J, Witt O, Hernaiz Driever P, et al. Response assessment in paediatric low-grade glioma: recommendations from the Response Assessment in Pediatric Neuro-Oncology (RAPNO) working group. Lancet Oncol. 2020; 21(6):e305–e316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fangusaro J, Onar-Thomas A, Young Poussaint T, et al. Selumetinib in paediatric patients with BRAF-aberrant or neurofibromatosis type 1-associated recurrent, refractory, or progressive low-grade glioma: a multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019; 20(7):1011–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nobre L, Zapotocky M, Ramaswamy V, et al. Outcomes of BRAF V600E pediatric gliomas treated with targeted BRAF inhibition. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020; (4):561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cabanillas ME, Patel A, Danysh BP, et al. BRAF inhibitors: experience in thyroid cancer and general review of toxicity. Horm Cancer. 2015; 6(1):21–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bavle A, Jones J, Lin FY, et al. Dramatic clinical and radiographic response to BRAF inhibition in a patient with progressive disseminated optic pathway glioma refractory to MEK inhibition. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017; 34(4):254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. D’Arco F, O’Hare P, Dashti F, et al. Volumetric assessment of tumor size changes in pediatric low-grade gliomas: feasibility and comparison with linear measurements. Neuroradiology. 2018; 60(4):427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.