Abstract

Background:

COVID-19 outbreak and the followed confinement measures have raised concerns to specialists worldwide regarding the imminent increase in domestic violence cases. The present systematic review aims to identify the international trends in domestic violence during the COVID-19 epidemic and to examine the possible differences among all population groups and different geographic areas worldwide.

Method:

The following databases were accessed: DOAJ, ERIC, Google Scholar, ProQuest, Pubmed, PsycNet, and SCOPUS, up to July 22, 2020.

Results:

A total of 32 studies were considered eligible. Data from North America, Europe, Asia-Pacific Area, Africa, and worldwide researches were retrieved. COVID-19 has caused an increase in domestic violence cases, especially during the first week of the COVID-19 lockdown in each country. In children, however, although the specialists’ estimations suggested an increase in child maltreatment and abuse cases, the rate of police and social services’ reports has declined during the COVID-19 pandemic. School closures that isolated students at home seemed to have contributed to this decrease.

Conclusions:

Domestic violence has been a considerable issue imposed by the COVID-19 epidemic to a worldwide context. The home confinement led to constant contact between perpetrators and victims, resulting in increased violence and decreased reports. In order to minimize such issues, prevention measures and supporting programs are necessary.

Keywords: COVID-19, domestic violence, confinement, intimate partner violence, child abuse

The ongoing pandemic of COVID-19 forced many countries to impose national lockdowns as a measure of protection against the virus spread. Although home confinement due to COVID-19 pandemic was a necessary measure of protection against the virus spread, it induced social, psychological, and economical consequences. One of them was the increase of domestic violence cases (United Nations, 2020). Domestic violence (or domestic abuse) includes various acts of violence—physical, sexual, and emotional—and, although it is usually referred to intimate partner violence, mostly between a male and a female partner, it can also include child, elderly, or sibling abuse (Hegarty et al., 2000). Especially for children, domestic abuse can include not only direct violence toward them but also witnessing violence against other members of their family (e.g., their mothers or siblings) and it can lead to forming violent intimate partner relationships in adulthood (Wood & Sommers, 2011). In this article, domestic violence will be used for all kinds of violence within family or domestic context, including both violence against adults (partners, elders, adult children, or adult siblings) and minors (children and adolescents) or in cases that there is not clear if the reported abuse was against partners or other member of the family (e.g., police reports without specific demographic data), whereas in cases of violence against partners, the term intimate partner violence will be used, and in cases of violence against children, the term child abuse will be used.

Differences in the meaning of violence are presented from culture to culture, promoting mainly the family benefit rather than the individual prosperity (Krauss, 2006). In some communities, predominance of the male point of view is considered legit and the domestic violence is justified as normal, incorporating religious laws (Fagan & Browne, 1994). Thus, a global prevention program is difficult to occur, due to racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic discrimination (αlhabib et al., 2010).

During periods of crisis, increased rates of intimate partner violence, child, and elderly abuse have been reported, in relation to economic instability and stressful environments (Curtis et al., 2000; Mansi et al., 2020; Parkinson & Zara, 2013; Schneider et al., 2016). This observation was made in the United States during the Great Recession (Schneider et al., 2016), and such findings spanned also more recent eras, including the European debt crisis in the 2010s (Kyriakidou et al., 2019). Concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of domestic violence could be higher, due to home confinement, limited access to social services, and supporting organizations for the victims. On the other hand, school closures isolated students at home, distancing them from their teachers, which are the professionals who more frequently submitted the reports of child abuse (20.5% of overall reports; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services et al., 2020).

Because domestic violence is an important issue, data can be derived mainly from police reports but also from helpline calls. However, police reports might describe a small part of reality, because many victims are afraid of reporting domestic violence to the authorities, due to discrimination and labeling (Gqola, 2015). Furthermore, not all police calls for domestic violence were reported or there were changes in reporting, due to lack of evidence (Beland et al., 2020). The lockdown forced the potential victims to stay close to their perpetrators, the latter monitoring any move and effort of contacting the police (Piquero et al., 2020; van Gelder et al., 2020); helplines may have given victims a better opportunity to speak out and to take the situation under control (Elman et al., 2020).

Considering the special circumstances derived from COVID-19, including home confinement and preventing measures imposed by countries worldwide, the research of the impact of domestic violence in partners, children or elderly, is highly recommended. Therefore, this systematic review aims to synthesize international findings and trends regarding domestic violence toward all population groups, examining the differences among different geographic areas during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Method

Study Design

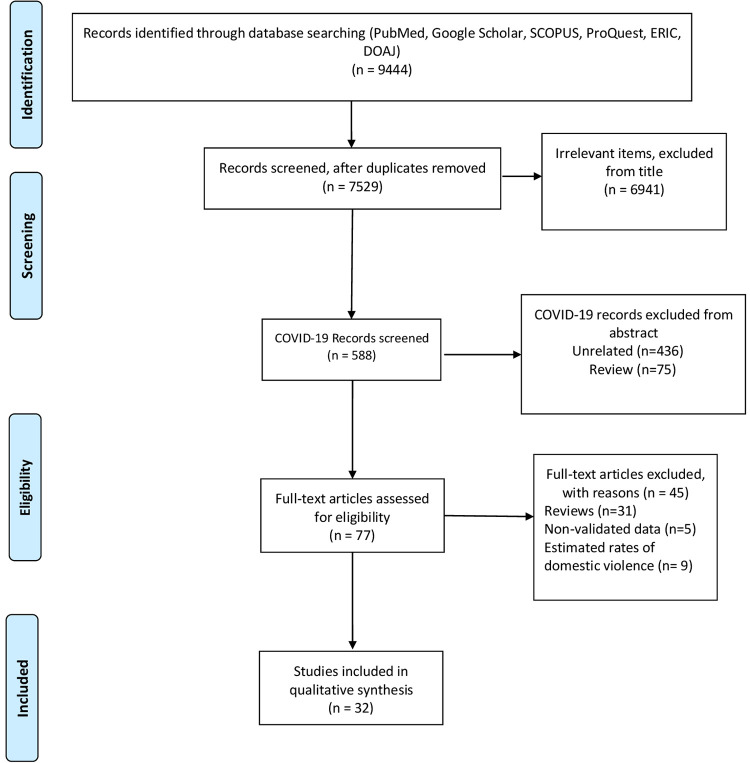

This systematic review was performed under the recommended reference framework of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2020). The search was conducted in the following databases: DOAJ, ERIC, Google Scholar, ProQuest, Pubmed, PsycNet, and SCOPUS, up to July 22, 2020. Th) algorithm used was the following: (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR “2019-nCoV” OR “novel coronavirus”) AND (“domestic violence” OR “family violence” OR “intimate partner violence” OR abuse OR maltreatment OR vulnerability OR assault). Using a snowballing technique, references of eligible studies and relevant reviews were also searched.

Inclusion Criteria

All articles that examined violence within domestic settings in all ages and groups of people (children, adolescents, adult women, elder, disabled people, etc.) during the COVID-19 outbreak (started from December 2019 and continues until the time of drafting this article—July 2020) were considered eligible for this systematic review. Domestic violence is generally used for all kinds of violence within family or domestic context, including both violence against adults (partners, elders, adult children, or adult siblings) and minors (children and adolescents). In cases that it is not clear whether the reported abuse was against partners or other member of the family (e.g., police reports without specific demographic data), the term “domestic violence” was used; in cases of violence against children, the term “child abuse” was used; and in cases of violence between partners, the term “intimate partner violence” was used. Regarding study design, case reports, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, and case-control studies were selected. Data and reports from organizations for domestic abuse, human rights organizations, or police data were also used as supporting evidence. There was no language, gender, age, or other demographic restrictions. Two authors (A.K. and A.S.) working independently to each other in pairs performed the selection of studies.

Data Extraction and Analysis

A piloted data extraction form was used to extract data from eligible articles, which were reviewed simultaneously and independently from two reviewers (A.K. and A.S.). The following data were extracted for each study: name and identity of the article, name of the first author and year of publication, region/country where the survey was conducted, language, study period, study design, sample, sample size, age range, selection of sample, ascertainment and/or association with COVID-19 epidemic, outcomes, statistical analysis, and main findings, including features of intimate violence and child abuse. Discussion through reviewers and team consensus resolved any disagreement.

Quality Assessment

During the screening process, two independent reviewers (A.K. and A.S.) performed the quality assessment, evaluating the risk of bias in eligible studies, through Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies (Modesti et al., 2016) and cohort studies (Stang, 2010) accordingly.

Results

Selection of Studies

The publications retrieved from research in databases were 9,444. Of them, 2,415 were duplicates, and 6,941 were excluded by the title as irrelevant. Thus, 588 articles were screened by abstract with 436 being irrelevant while 75 were reviews. Of 77 full-text articles that were assessed for eligibility, 32 studies were finally included (Armbruster & Klotzbücher, 2020; Asiamah et al., 2021; Baron et al., 2020; Beland et al., 2020; Biddle et al., 2020; Boserup et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2020; Brülhart & Lalive, 2020; Davis et al., 2020; Foster & Fletcher, 2020; Frank et al., 2020; Halford et al., 2020; Huber, 2020; Iob et al., 2020; Jung et al., 2020; Knipe et al., 2020; Leslie & Wilson, 2020; McLay, 2021; Mohler et al., 2020; Nduna & Oyama, 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2020; Pfitzner et al., 2020; Piquero et al., 2020; Roca et al., 2020; Sanga & McCrary, 2020; Sibley et al., 2020; Sidpra et al., 2020; Silverio-Murillo et al., 2020; Stiegler & Bouchad, 2020; Wright et al., 2020a , 2020b; Figure 1, flowchart; Table 1). Among them, two presented data from various countries worldwide (Argentina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Chile, Cyprus, France, India, Lebanon, Mexico, Montenegro, Singapore, Spain, United States, United Kingdom, Italy, and worldwide estimation of child abuse violence based on data from previous years), 11 referred to North America countries (United States: n = 9, Canada: n = 1, and Mexico: n = 1), 10 to Europe (United Kingdom: n = 6, Germany: n = 2, Switzerland: n = 1, and Spain: n = 1), six to the Asia-Pacific region (Australia: n = 5 and New Zealand: n = 1), and the remaining three reported data from Africa (South Africa: n = 2 and Ghana: n = 1). The majority (n = 26) were cross-sectional studies and six were cohort studies (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Included Studies.

| First Author (Year) | Region, Country | Language | Study Period | Study Design | Sample | Sample Size | Age Range | Selection of Sample | Phase of COVID-19 Pandemic | Outcomes, Way/Questionnaires for Measurement | Statistical Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huber (2020) | Argentina, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Brazil, Chile, Cyprus, France, India, Lebanon, Mexico, Montenegro, Singapore, Spain, and United States (domestic violence in general), worldwide (estimation of child abuse violence) | English | NR | Cross-sectional study | NR | NR | NR | People who called to SOS hotline for domestic violence during COVID-19 | COVID-19 outbreak | NR | NR |

| Armbruster & Klotzbücher (2020) | Germany | English | January 1, 2019–April 28, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Users of online telephone counseling hotline “TelefonSeelsorge” | 715,227 (68.3% female, 31.5% male, 0.2% other of 697,929) | 10–80+ | People who used online and telephone counseling hotline “TelefonSeelsorge” during COVID-19 (91 help centers) | COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown | Email, chat, and telephone contacts | Kernel-weighted local polynomial regression |

| Asiamah et al. (2021) | Ghana | English | April 4, 20–April 16, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | General population, 18+ socially isolated due to the mandatory lockdown | 643 (35% female; 65% male) | 18–64 | Residents of three cities in Ghana that were under mandatory lockdown (City 1, City 2, and City 3), who participated in an online survey | COVID-19 lockdown | Online survey-questionnaire (23 multiple-choice questions and a question introducing the mental health measure) | Descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression analysis, with a sensitivity analysis selecting potential covariates for the final regression model |

| Beland et al. (2020) | Canada | English | March 29, 2020–April 3, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Canadians who participated in the online survey (the Canadian Perspective Survey Series) | 4,627 (2,433 women) | 35–55+ | Accessed via email | COVID-19 lockdown | Online survey | NR |

| Biddle et al. (2020) | Australia | English | April–May 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Adult Australians | 2,984 in April and 3,249 in May | 18–75+ | Sample from Life in Australia TM panel | COVID-19 lockdown | Online survey | Regression analysis |

| Sanga & McCrary (2020) | United States | English | January 1, 202–April 24, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | People in America who call 911 | Approximately 50 million calls (not people) | NR | 911 Calls | COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown | Reports to the police | NR |

| Boserup et al. (2020) | United States | English | March 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Police Reports | NR | NR | Data from police departments | COVID-19 outbreak | Reports to the police | Cursory analysis |

| Brown et al. (2020) | Rocky Mountain, USA. | English | April 21, 20–May 9, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Parents over 18 with a child under 18 | 183 | 18–55 | Child- and family-serving agencies and educational settings | COVID-19 lockdown | Online survey | Analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyses and multiple regression analyses |

| Brülhart & Lalive (2020) | Switzerland | English | February 28, 2019–May 6, 2019 and February 28, 2020–May 6, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Adults, mainly German-speaking residents of Switzerland | 63,639 (for 2019 and 2020) | NR | Helpline calls, mainly in German | COVID-19 lockdown | Reports to helpline | Regression analysis |

| Davis et al. (2020) | United States | English | March 17, 2020–May 1, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | U.S. residents over 18+ | 2.045 | 18–91 | Participants recruited via a survey company | COVID-19 lockdown | Jellinek inventory for assessing partner violence (intimate partner violence [IPV]) | Descriptive statistics, Spearman nonparametric correlation analyses, four binary logistic regressions, and univariate analysis |

| Frank et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | English | March 21, 2020–April 2, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Vulnerable individuals in the United Kingdom | 51,417 (female 51.1%) | 18+ | Participants recruited via the COVID-19 Social Study | COVID-19 lockdown | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; +participants indicated whether during the last week they had been “physically harmed or hurt by someone else” or “bullied, controlled, intimidated, or psychologically hurt by someone else”, using a 4-point Likert-type scale and stating if they have been abused more than once during this period) |

Mixture modeling and multivariate logistic regression models |

| Foster & Fletcher (2020) | Australia (New South Wales) | English | March 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Frontline workers and service providers | 80 | NR | NR | COVID-19 outbreak | Survey | Trend, daily effects and weather effects were removed by applying separate linear regressions for each effect. A piecewise linear model approach was adopted which allowed trends to be analyzed sequentially. The resulting residuals from the detrended and deseasoned models were analyzed with auto regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) time series models, The resulting ARIMA model was used, along with the daily effect, the weather effect and trend, to produce a forecast value for each crime type with an associated 95% confidence interval |

| Halford et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | English | March 8, 2020–April 2, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Crime reports | NR | NR | NR | COVID-19 lockdown | Police data | NR |

| Iob et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | English | March 21, 2020–April 20, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Adults in the United Kingdom | 44,775 | 18+ | COVID-19 Social Study | COVID-19 lockdown | PHQ-9 (+Participants indicated whether during the last week they had been “physically harmed or hurt by someone else” or “bullied, controlled, intimidated, or psychologically hurt by someone else”, using a 4-point Likert-type scale and stating if they have been abused more than once during this period) | Regression analysis |

| Jung et al. (2020) | Germany | English | April 1, 2020–April 15, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | NR | 3,545 (83,1% female) | NR | Online survey | COVID-19 lockdown | PHQ-9 | Descriptive statistics |

| Knipe et al. (2020) | Italy, Spain, United States, United Kingdom, and worldwide | English | January1, 2020–March 30, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Google trends | NA | NA | Google searches | COVID-19 outbreak | Google search | Correlation analysis |

| Leslie & Wilson (2020) | United States (Baltimore, MD; Chandler, AZ; Cincinnati, OH; Detroit, MI; Los Angeles, CA; Mesa, AZ; Montgomery County, MD; New Orleans, LA; Phoenix, AZ; Sacramento, CA; Salt Lake City, UT; Seattle, WA; Tucson, AZ; and Virginia Beach, VA) | English | January1, 2019–May 31, 2019, and January 6, 2020–May 31, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Calls for reporting domestic violence in the United States | NR | NR | Domestic violence service calls | COVID-19 lockdown | Police data | Difference-in-differences and event study methods |

| Baron et al. (2020) | United States: Florida | English | January 2015–April 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Child abuse reports in Florida | 13,132 by month observations | NR | Child abuse reports | COVID-19 outbreak | Child abuse hotline data | Regression analysis |

| McLay (2021) | United States: Chicago | English | March 2019 and March 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Domestic violence reports in Chicago | 4,618 reports | NR | Domestic violence police reports | COVID-19 outbreak | Domestic violence police reports | Logistic regression models |

| Mohler et al. (2020) | United States: Indianapolis, Los Angeles | English | January 2, 2020–April 22, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Domestic violence reports Indianapolis and Los Angeles | NR | NR | Crime police data | COVID-19 outbreak | Calls-for-service and reports to the police | Regression analysis |

| Nduna & Oyama (2020) | South Africa | English | March27, 2020–April16, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | People who call to gender-based violence command center call | NR | NR | NR | COVID-19 lockdown | Rapid assessment was used to gather context specific data in response to the COVID-19 lockdown | NR |

| Nguyen et al. (2020) | Australia | English | March 23, 2020–April 2, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Women, men, boys, and girls in Australia | 209 reports | NR | Existing secondary data | COVID-19 outbreak | Rapid gender analysis | NR |

| Payne et al (2020) | Queensland, Australia | English | February 2014–2020 (March–April 2020) | Cohort study | Queensland population | Statewide monthly offense rates per 100,000 | NR | Queensland government’s open data portal | COVID-19 lockdown | ARIMA model | Statistical assessment of the presence of a unit-root (nonstationarity). To explore stationarity, the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test is used. The null-hypothesis of the ADF test is that raw series is nonstationary (i.e., includes unit-root). Failure to reject the null-hypothesis at p < .05 indicates the presence of a unit root and necessitates its removal |

| Pfitzner et al. (2020) | Victoria, Australia | English | April 23 2020–May 24 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Victorian practitioners | 166 | NR | Online anonymous survey through social media outlets (including Twitter and LinkedIn), through the Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre network, and by providing information about the research and survey directly to relevant organizations and agencies in Victoria | COVID-19 lockdown | A series of short demographic questions with a rating scale and open-ended questions | Univariate analyses |

| Piquero et al. (2020) | Dallas, TX, USA | English | January 1, 2020 and April 27, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Incidents of domestic violence | NR | NR | Dallas police records | COVID-19 outbreak | Family violence incident list includes misdemeanor and felony domestic violence, child abuse, elderly abuse, and sexual assault for offenses |

A Dickey–Fuller test for nonstationarity and a correlogram plot to determine whether lagged values are autocorrelated with the domestic violence data series were used, multiple ordinary least squares and Poisson regression models, ARIMA forecast model |

| Roca et al. (2020) | Valencia and Murcia, Spain | English | March 18, 2020–April 10, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Principals, teachers, and school counselors of nine schools | 10 Members of the school staff | 31–50 | Nine schools (preprimary, primary, secondary, and special education) | COVID-19 lockdown | WhatsApp group with the members of the communicative focus group (CFG) and a collaborative Excel sheet shared through Drive with a register of the actions that the teachers entered and three sessions were conducted with the same CFG and interviews with a communicative approach | Dialogic recreation of knowledge |

| Sibley et al. (2020) | New Zealand | English | October–December, 2019 and March, 2020 | Cohort study | New Zealanders | Nprelockdown = 1,003 and Nlockdown = 1,003 | Prelockdown (mean age = 51.7), lockdown (mean age = 51.5) | New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study (NZAVS), propensity score matching | \ | New Zealanders answered the survey during the first 18 days of lockdown. Comparing their responses with those of a propensity-matched control sample who completed the NZAVS late in 2019 (before the pandemic emerged) | A multivariate ANOVA was conducted to assess whether the linear combination of all outcome variables, Levene’s tests of equality of variances, paired-sample t tests |

| Sidpra et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | English | March, 23, 2020–April, 23, 2020, with same period over the previous 3 years | Cohort study | Children | 10 (six boys, four girls) with mean cases at the same period over the previous 3 years | Mean age 192 days | Medical records of Great Ormond Street Hospital For Children National Health Service Foundation Trust, London |

COVID-19 lockdown | A review of the incidence of suspected abusive head trauma in submitting children during lockdown with records of the previous 3 years. Demographic data and clinical findings were recorded, including parental vulnerabilities and socioeconomic indexing by the index of multiple deprivation | NR |

| Silverio-Murillo & Balmori de la Miyar (2020) | Mexico city | English | February, March, April, and the rest 2 weeks of May, for 2019 and 2020 | Cohort study | Calls from women who were married or cohabiting | Number of calls per week for domestic violence per 100,000 inhabitants | NR | Linea Mujeres call-center service records | COVID-19 lockdown | Data on calls related to IPV. Population data come from the National Population Council. Data were used from the 16 municipalities of Mexico City. Week 7 was used as a cutoff reference to analyze the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown. “Control” refers to the six weeks prior to the lockdown, while “treatment” refers to the 8 weeks during the lockdown | A weekly event study model |

| Stiegler & Bouchad (2020) | South Africa | English | April 24, 2020 | Quick assessment (cross-sectional study) | People from different backgrounds and residing in different areas of the country | 32 | 20–75 | NR | COVID-19 lockdown | Six questions, sent via email or text messages | NR |

| Wright et al. (2020b) | United Kingdom | English | April 1, 2020–May 12, 2020 | Longitudinal cohort study | UK adults | 41.909 | 18–65 | COVID-19 social study | COVID-19 outbreak | PHQ-9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder assessment, six categories of adversity, each measured weekly, including COVID-19 illness, financial difficulty, loss of paid work, difficulties acquiring medication, and difficulties accessing food and threats to personal safety. | Fixed-effects regression |

| Wright et al. (2020a) | United Kingdom | English | April 1, 2020–May 12, 2020 | Longitudinal cohort study | UK adults | 46.284 | 18–65 | COVID-19 social study | COVID-19 outbreak | Six categories of adversity, each measured weekly, including COVID-19 illness, financial difficulty, loss of paid work, difficulties acquiring medication, difficulties accessing food, and threats to personal safety. Single item on quality of sleep. Social support with four separate variables for loneliness, perceived social support, social network size, and living alone. Three-item UCLA-3 loneliness, six-item short form of Perceived Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU K-6), psychiatric illness as reporting a clinically diagnosed mental health problem in interview | Random-effect within-between models |

Note. NA = not applicable; NR = not reported.

Descriptive Characteristics

The descriptive characteristics of the eligible studies are presented in Table 1. The majority of studies were conducted during COVID-19 lockdown (Asiamah et al., 2021; Beland et al., 2020; Biddle et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2020; Brülhart & Lalive, 2020; Davis et al., 2020; Frank et al., 2020; Halford et al., 2020; Iob et al., 2020; Jung et al., 2020; Leslie & Wilson, 2020; Nduna & Oyama, 2020; Payne et al., 2020; Pfitzner et al., 2020; Roca et al., 2020; Sibley et al., 2020; Sidpra et al., 2020; Silverio-Murillo et al., 2020; Stiegler & Bouchad, 2020), approximately between March and May 2020, while a few were conducted during COVID-19 outbreak (Armbruster & Klotzbücher, 2020; Baron et al., 2020; Boserup et al., 2020; Foster & Fletcher, 2020; Huber, 2020; Knipe et al., 2020; McLay, 2021; Mohler et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020; Piquero et al., 2020; Sanga & McCrary, 2020; Wright et al., 2020a , 2020b). Moreover, many studies included data from police or helplines reports (eight studies based on police records (Boserup et al., 2020; Halford et al., 2020; Leslie & Wilson, 2020; McLay, 2021; Mohler et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2020; Piquero et al., 2020; Sanga & McCrary, 2020), five studies based on helplines data (Armbruster & Klotzbücher, 2020; Brülhart & Lalive, 2020; Huber, 2020; Nduna & Oyama, 2020; Silverio-Murillo et al., 2020), and two studies that used data stated as domestic abuse reports without clarifying whether they were from police reports or domestic abuse services’ reports (Baron et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020) or data retrieved through online surveys (12 studies), due to the COVID-19 restrictions (Asiamah et al., 2021; Beland et al., 2020; Biddle et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2020; Frank et al., 2020; Iob et al., 2020; Jung et al., 2020; Pfitzner et al., 2020; Stiegler & Bouchad, 2020; Wright et al., 2020a , 2020b). As a rule, subgroups of domestic violence (intimate partner violence, child abuse, elder abuse, or other kind of abuse) were not provided; some studies though gave specific results for one or more specific subgroups (Halford et al., 2020; Huber, 2020).

North America

Main Findings

Several studies in North America revealed an increase in domestic violence. Multiple studies were conducted in the United States using police data or helpline reports, reporting an increase in domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, domestic violence report rates increased, by 12% on average and 20% during working hours of potential abusers; an increase in first-time abuse (16% on average, 23% during working hours) was also noted (Sanga & McCrary, 2020—study was conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown—Table 1). Leslie and Wilson (2020), at their research in several cities and different states across the United States (Baltimore, MD; Chandler, AZ; Cincinnati, OH; Detroit, MI; Los Angeles, CA; Mesa, AZ; Montgomery County, MD; New Orleans, LA; Phoenix, AZ; Sacramento, CA; Salt Lake City, UT; Seattle, WA; Tucson, AZ; and Virginia Beach, VA) during COVID-19 lockdown also suggested that there was a 7.5% increase in domestic violence service calls during the 12 weeks of social distancing comparing with previous periods (January–May 31; Tables 1 and 2). Police data reports from Dallas (TX) implied that the trend in domestic violence changed twice; it increased after March 24, 2020, and decreased after April 7, 2020, suggesting that there was an increase in domestic violence in the first 2 weeks after the stay-at-home order, but then a decrease was observed (Piquero et al., 2020; Table 2). Furthermore, the study by Mohler et al. (2020) revealed an interesting fact. Even though there was a significant increase in domestic violence calls-for-service, eventually it did not lead to an increase in reported assaults during the COVID-19 outbreak (January–April 2020)

Table 2.

Main Findings Concerning Domestic Violence, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), and Child Abuse During the COVID-19 Epidemic.

| First Author (Year) | Region, Country | Sample | Sample Size | Age Range | Main Findings | Main Findings Regarding IPV | Main Findings Regarding Child Abuse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huber (2020) | Argentina, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Brazil, Chile, Cyprus, France, India, Lebanon, Mexico, Montenegro, Singapore, Spain, United States (domestic violence in general), and worldwide (estimation of child abuse violence) | NR | NR | NR | Increase in calls to domestic violence hotlines: Argentina 25%, Bosnia and Herzegovina 22%, Brazil 18%, Chile 75%, Cyprus 47%, France 30%, India 32%, Lebanon 50%, Mexico 25%, Montenegro 27%, Singapore 33%, Spain 12%, and United States 21.50%. Increase in calls to domestic violence hotlines: 32%. Estimation of increase in violence against children: 264,694,111 (3-month average number of children ages 2–17 exposed to any violence or severe violence), 52,938,822 (a 20% increase), and 84,702,116 (a 32% increase). Stricter states experienced a stronger increase in helpline calls compared to less strict states | NR | Estimation of increase in violence against children: Africa: (3-month average number of children ages 2–17 exposed to any violence or severe violence) 57,440,932; (a 20% increase) 11,488,186; (a 32% increase) 18,381,098. Asia: (3-month average number of children ages 2–17 exposed to any violence or severe violence) 17,889,193; (a 20% increase) 3,577,839; (a 32% increase) 5,724,542. Latin America: (3-month average number of children ages 2–17 exposed to any violence or severe violence) 14,607,329; (a 20% increase) 2,921,466; (a 32% increase) 4,674,345. Europe: (3-month average number of children ages 2–17 exposed to any violence or severe violence) 3,798,000; (a 20% increase) 759,600; (a 32% increase) 1,215,360. Northern America: (3-month average number of children ages 2–17 exposed to any violence or severe violence) 10,048,608; (a 20% increase) 2,009,722; (a 32% increase) 3,215,554. Oceania: (3-month average number of children ages 2–17 exposed to any violence or severe violence) 160,049; (a 20% increase) 32,010; (a 32% increase) 51,216 |

| Armbruster & Klotzbücher (2020) | Germany | Users of online telephone counseling hotline “TelefonSeelsorge” | 715,227 (68.3% female, 31.5% male, 0.2% other of 697,929) | 10–80+ | Physical and sexual violence were highly increased in the first week after the lockdown and they gradually decreased (physical violence: 1.8% of 702,351; sexual violence: 1.2%) | NR | NR |

| Asiamah et al. (2021) | Ghana | General population, 18+ socially isolated due to the mandatory lockdown | 643 (35% female; 65% male) | 18–64 | 8% of participants (n = 50) faced higher risk of domestic violence | NR | NR |

| Beland et al. (2020) | Canada | Canadians who participated in the online survey (the Canadian Perspective Survey Series) | 4,627 (2,433 women) | 35–55+ | There was no correlation between family stress and violence and COVID-19 outbreak. There was correlation between family stress and violence, and financial difficulties as well as difficulties in maintaining social ties (for women). 3% of respondents reported being “extremely” concerned about violence in the home. About 5% of respondents were “very concerned,” 8% are “somewhat” concerned | NR | NR |

| Biddle et al. (2020) | Australia | Adult Australians | 2,984 in April and 3,249 in May | 18–75+ | 9.5% had fear of their partner being violate | 9.5% had fear of their partner being violate. There has no statistical significance between two sexes. Highest rate: 25–34, lowest rate: 65+ | NR |

| Sanga & McCrary (2020) | United States | People in America who call 911 | Approximately 50 million calls (not people) | NR | Increase of domestic violence 12% on average and 20% during working hours. Increase of first-time abuse (16% on average, 23% during working hours) | NR | NR |

| Boserup et al. (2020) | United States | Police reports | NR | NR | 27% increase of domestic violence in Jefferson, AL, 22% in Portland, OR, 18% in San Antonio, TX, and 10% in New York City | NR | NR |

| Brown et al. (2020) | Rocky Mountain, USA | Parents over 18 with a child under 18 | 183 | 18–55 | Greater COVID-19-related disruptions, high anxiety, and depressive symptoms were associated with child abuse potential | NR | Demographics (p < .01), financial assistance (p < .01), anxiety symptoms (p < .05), depressive symptoms (p < .01), and perceived stress (p < .01) were significantly and positively associated with child abuse potential |

| Brülhart & Lalive (2020) | Switzerland | Adults, mainly German-speaking residents of Switzerland | 63,639 (for 2019 and 2020) | NR | −25% calls due to domestic violence compared to the same period in 2019 | NR | NR |

| Davis et al. (2020) | United States | U.S. residents over 18+ | 2.045 | 18–91 | People having symptoms similar to COVID-19 or diagnosed with COVID-19 were more likely to face IPV (psychological or physical) | People reporting COVID-19 positive were approximately 3.5 times more likely to experience psychological IPV (Exp[B] = 3.77, [1.36, 10.42], p < .05) and 2.5 times more likely to experience physical IPV (Exp[B] = 2.77, [1.04, 7.36], p <.05). People who lost their job during COVID-19 outbreak were 2.5–3 times more likely to face IPV (psychological: Exp[B] = 2.56, [1.26, 5.18], p < .01; physical: Exp[B] = 3.21, [1.67, 6.58], p < .01). People who were tested for COVID-19 but were negative were twice as likely to face intimate psychological or physical partner violence (Exp[B] = 2.09, [1.23, 3.57], p < .01; Exp[B] = 2.20, [1.26, 3.86], p < .01). Men were two times more likely to use physical violence in comparison to women (Exp[B] = 2.16, [1.31, 3.56], p < .01) | NR |

| Frank et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | Vulnerable individuals in the United Kingdom | 51,417 (female 51.1%) | 18+ | 11.3% of the participants had experienced psychological or physical abuse on at least one occasion since lockdown began, the odd ratio (OR) of moderate depressive symptoms was 5.34 (5.15; 5.54) for participants who had experienced abuse, the OR of severe depressive symptoms associated with abuse was 13.16 (12.95; 13.37) | NR | NR |

| Foster & Fletcher (2020) | Australia (New South Wales) | Frontline workers and service providers | 80 | NR | 65.2% identified insufficient service availability, 49.2% identified women prioritizing material needs and concerns over their own safety, 44.9% identified escalating and worsening violence, 36.2% identified that women were reporting violence and abuse related to the COVID-19 crisis (e.g., financial pressures or other stresses), and 15.9% identified violence beginning to occur for the first time | NR | NR |

| Halford et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | Crime reports | NR | NR | Domestic abuse was decreased by 45% and vulnerable child offences decreased by 41% | NR | Vulnerable child offenses decreased by 41% |

| Iob et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | Adults in the United Kingdom | 44,775 | 18+ | Overall, 4,121 participants (9%) surveyed reported experiencing psychological or physical abuse, 7,984 participants (18%) reported experiencing thoughts of suicide or self-harm in the first month of lockdown, and 2,174 participants (5%) reported harming themselves at least once since the start of the UK’s lockdown. Around 50% of participants experiencing psychological or physical abuse had experienced thoughts of suicide or self-harm and 25% of them had engaged in self-harm behaviors during the previous week | NR | NR |

| Jung et al. (2020) | Germany | NR | 3,545 (83,1% female) | NR | 5% of the participants experienced interpersonal violence, verbal (98.4%), physical (41.9%), or sexual (30.2%). In case of verbal violence, 77.3% reported experiencing more verbal violence lately. In case of physical violence, 19.5% reported experiencing increased levels, and in case of sexual violence, more people reported experiencing increased sexual violence lately (11.1%) | NR | NR |

| Knipe et al. (2020) | Italy, Spain, United States, United Kingdom, and Worldwide | Google trends | NA | NA | Abuse related searches remained stable in the United Kingdom, United States, and Spain. | NR | NR |

| Leslie & Wilson (2020) | United States (Baltimore, MD; Chandler, AZ; Cincinnati, OH; Detroit, MI; Los Angeles, CA; Mesa, AZ; Montgomery County, MD; New Orleans, LA; Phoenix, AZ; Sacramento, CA; Salt Lake City, UT; Seattle, WA; Tucson, AZ; and Virginia Beach, VA) | Calls for reporting domestic violence in the United States | NR | NR | There was a 7.5% increase in domestic violence service calls during the 12 weeks after social distancing began | NR | NR |

| Baron et al. (2020) | United States: Florida | Child abuse reports in Florida | 13,132 by month observations | NR | Reported allegations for child maltreatment were approximately 15,000 lower than expected | NR | Reported allegations for child maltreatment were approximately 15,000 lower than expected |

| McLay (2021) | United States: Chicago | Domestic violence reports in Chicago | 4,618 reports | NR | The number of total cases was slightly lower during March 2020 (70.32% [n = 1,583] of cases took place prior to the shelter in- place and 29.68% [n = 668] of cases took place after) than during March 2019. March 2020 overall: 2.84% cases with sex crimes, 14.83% weapon use, 20.23% arrests, 2.97% child victims involved, and 77.85% residential locations | NR | Cases with child victims were 67% less likely to have occurred |

| Mohler et al. (2020) | United States: Indianapolis, Los Angeles | Domestic violence reports Indianapolis and Los Angeles | NR | NR | Although there was a significant increase in domestic violence calls-for-service, it did not lead to the increase of reported assaults | Volume of calls per day for domestic violence: Los Angeles (Δy = 13.55) and Indianapolis (Δy = 15.22) | NR |

| Nduna & Oyama (2020) | South Africa | People who call to gender-based violence command center call | NR | NR | Received 12,779 calls of them 442 gender-based violence-related, including abandoned children, assault, bullying, child neglect, child pornography, elderly neglect, emotional abuse, hate speech, human trafficking, indecent assault, molestation, verbal abuse or intimidation, rape, sexual harassment, and physical violence. South African news reported that police statistics for the first week of lockdown showed that more than 2,300 complaints of gender-based violence were recorded. Google also shared that there had been a 64% spike in online searches for the words “domestic violence shelters” | Up to 40% of women who normally would not seek help may have reported with the hope that police help will be dispatched sooner | NR |

| Nguyen et al. (2020) | Australia | Women, men, boys, and girls in Australia | 209 reports | NR | Early reports indicated that there had been an increase in family violence with an increase in support requests from 120 per week to 209 in the last week (as of March 29, 2020). Cases reported to included perpetrators using COVID-19 as a means of further controlling their partner’s movements and preventing them from leaving home or threatening to infect women with COVID-19. There were reports of perpetrators using COVID-19 as a form of abuse by telling their partners that they (the partners) had the virus; therefore, they could not leave the house or inviting people into the house where the woman was self-isolating and saying to her that the visitor had COVID-19 and they were going to infect them. Becoming infected with the virus may also prevent women from seeking help, as they were forced to self-quarantine and thereby unable to access walk-in support services | NR | NR |

| Payne et al. (2020) | Queensland, Australia | Queensland population | Statewide monthly offense rates per 100,000 | NR | The observed domestic violence orders (DVO) breach rate in March 2020 was 57.5 per 100,000 which was higher than in the previous month (55.2 per 100,000) and higher than it was in March of the previous year (52.0 per 100,000). As for the observed breach rate of DVO in March 2020, the rate (57.5 per 100,000) was lower than forecast by the model (59.2 per 100,000) but well within the range (54.9 to 63.4 per 100,000) of plausible values given the history of the series. In April, the DVO breach rate declined slightly, although not as much as was forecast and remained within the confidence interval. There was insufficient evidence to suggest that breaches of domestic violence orders increased or decreased in the context of COVID-19 | NR | NR |

| Pfitzner et al. (2020) | Victoria, Australia | Victorian practitioners | 166 | NR | Just under half of the practitioners surveyed (42%, n = 105) reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had resulted in an increase in first time family violence reporting by women | More than half of the respondents reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had led to an increase in the frequency (59%, n = 94) and severity of violence against women (50%, n = 102). New forms of intimate partner women, including enhanced tactics to achieve social isolation and forms of violence specifically relating to the threat and risk of COVID-19 infection | NR |

| Piquero et al. (2020) | Dallas, TX, USA | Incidents of domestic violence | NR | NR | There was statistically significant evidence that the trend in domestic violence changed twice: It increased after March 24 and decreased after April 7, there appeared to be an increase in domestic violence in the first 2 weeks after the stay-at-home order was implemented but then a decrease thereafter | NR | NR |

| Roca et al. (2020) | Valencia and Murcia, Spain | Principals, teachers, and school counselors of nine schools | 10 members of the school staff | 31–50 | Six actions had been implemented with the goal of “opening doors” to foster supportive relationships and a safe environment to prevent child abuse during COVID-19 confinement: dialogic workspaces, dialogic gatherings with students, class assemblies or mentoring, dialogic pedagogical gatherings with teachers and community, mixed committees and community networks, and social network dynamization with preventive messages and the creation of a sense of community | NR | All the schools that participated in the study knew very well that communication through social networks contributed to “open doors” and promoted a sense of community despite confinement. All these schools actively communicated through social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Telegram. In these communications, messages promoted supportive relationships and a sense of community. In addition, they were disseminating messages through social networks for the prevention of child abuse and violence. These actions included elements on elective school-based programs to prevent child abuse and encouraged the preventive socialization of violence. In the online dialogic workspaces created in four of the participating schools, the main action had been to “open doors” to break physical isolation by maintaining supportive relationships. Creating trusted environments involved not only small online workspaces but also their extension to the community by engaging families, fostering the responsibility of society to ensure the safety of children. Five of the schools had promoted solidarity networks through mixed committees formed by teachers, families, and other community members. Class assemblies were among the actions that many of these schools were taking prior to confinement. Five of the schools had maintained these activities during confinement. The assembly was perhaps most specifically where children’s knowledge and skills to prevent abuse and violence were directly addressed |

| Sibley et al. (2020) | New Zealand | New Zealanders | Nprelockdown = 1,003, Nlockdown = 1,003 | Prelockdown (mean age = 51.7), lockdown (mean age = 51.5) | Returning to the main analyses, the postlockdown group reported higher levels of support for investment in reducing domestic violence than did the prelockdown group | NR | NR |

| Sidpra et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | Children | 10 (six boys, four girls) with mean cases at the same period over the previous 3 years | Mean age = 192 days | A significant increase in the number of patients presenting with suspected abusive head trauma (AHT) during the lockdown phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic | NR | Ten children with suspected AHT were seen during this time in comparison with a mean of 0.67 cases per month in the same period over the previous 3 years. This equates to a 1,493% increase in cases of AHT. Age did not vary significantly between years (range = 0.5–13 months). Clinical examination revealed retinal hemorrhages (50%), extensive bruising (50%), scalp swelling (50%), and excoriation marks (10%). Radiological findings included subdural hemorrhage (60%), cerebral edema (40%), parenchymal contusion (40%), skull fractures (40%), subarachnoid hemorrhage (30%), and extracranial fractures (30%) |

| Silverio-Murillo et al (2020) | Mexico city | Calls from women who were married or cohabiting | Number of calls per week for domestic violence per 100,000 inhabitants | NR | In 2019, there was no difference between “treatment” (0.32) and “control” (0.33). IPV-calls increase from 0.32 in 2019 to 0.70 in 2020 for the “treatment” period. Yet, there was no statistically significant difference between “treatment” (0.70) and “control” (0.73) for 2020. This result suggests that IPV-calls did not increase during the confinement | NR | NR |

| Stiegler & Bouchad (2020) | South Africa | People from different backgrounds and residing in different areas of the country | 32 | 20–75 | Concerning domestic violence, respondents generally agreed that thanks to the ban of alcoholic beverages, domestic violence seemed to have decreased, and this especially in poorer areas | NR | NR |

| Wright et al. (2020b) | United Kingdom | UK adults | 41.909 | 18–65 | Experiences of adversities relating to accessing food, accessing medication, and personal safety were also associated with higher levels of generalized anxiety disorder assessment and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores. Experience of harm was more strongly related to mental health than worry about personal safety. Worries were more strongly related to mental health than experiences for employment and finances, but less for personal safety and catching COVID-19. Adversities relating to personal safety were much more strongly linked with mental health than worries about personal safety and had the strongest link with mental health out of all adversities assessed, which echoes research on the strong negative mental health impact of domestic abuse and violence | NR | NR |

| Wright et al. (2020a) | United Kingdom | UK adults | 46.284 | 18–65 | Worries were significantly related to poorer quality sleep in every category of adversity, with the largest effects found for worries about personal safety (OR = 1.43 [1.35, 1.53]). Experiencing adversities relating to personal safety such as abuse were also related to poor quality sleep (OR = 1.29 [1.14, 1.47]) | NR | NR |

Note. NA = not applicable; NR = nonreferred.

On the other hand, in Chicago, IL, a slight decrease in domestic violence cases seemed to occur, compared with those of the previous year (2,251 cases in March 2020 during the COVID-19 outbreak compared to 2,367 cases in March 2019; McLay, 2021). Similarly, no significant differences in domestic violence cases between 2019 and 2020 were recorded in Mexico City and Canada (Silverio-Murillo et al., 2020), although there was a correlation between family stress and violence and financial difficulties as well as difficulties in maintaining social ties (for women) in the COVID-19 lockdown in Canada (Beland et al., 2020; Table 2).

Intimate Partner Violence

Boserup et al. (2020) highlighted that domestic violence is often synonymous to intimate partner violence and indicated that there was an increase in several states in the United States at the first months of the pandemic outbreak (March 2020). In Jefferson (Alabama), a 27% increase in domestic intimate partner violence was reported, in Portland (Oregon) a 22%, in San Antonio (Texas) 18%, while in New York City, there was a 10% increase in domestic violence reports (Table 2). Moreover, in Davis et al. (2020), online survey was pointed out that people diagnosed with COVID-19 or with symptoms similar to those of COVID-19 were more likely to suffer from domestic violence, which was considered as an additional factor that raises the risk of domestic violence during the pandemic and especially during the lockdown (Table 2).

Child Abuse

According to reports deriving from Chicago, IL, the cases of domestic violence involving child victims during March 2020 were 67% less than in March 2019 (McLay, 2021; Table 2). On the other hand, Baron et al. (2020), supported that in Florida, USA, reported allegations for child maltreatment were approximately 15,000 lower than expected, probably due to school closure. A similar decrease was noted in the past year during December, June, and July, on school breaks. However, Brown et al. (2020) highlighted that COVID-19-related disruptions, such as high anxiety and depressive symptoms, were associated with child abuse potential during the time of the lockdown (Table 2).

Europe

Main Findings

Data from European studies are also in accordance with the data from North America, with a correlation recorded between COVID-19 and domestic violence incidents (Table 2). Most European studies derived from the United Kingdom (Frank et al., 2020; Halford et al., 2020; Iob et al., 2020; Sidpra et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2020a, 2020b), using data which were retrieved from University College of London (UCL) COVID-19 Social Study in the adult population (Frank et al., 2020; Iob et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2020a, 2020b). In the United Kingdom (Halford et al., 2020) and Switzerland (Brülhart & Lalive, 2020), an overall decrease in domestic violence police reports or helpline calls was noted during the lockdown. This might be explained by the fact that the lockdown measures inhibited access to alcohol, and consequently, its consumption has decreased (Halford et al., 2020). It is, however, more likely that the real numbers of domestic violence cases did not decline, but victims did not report their abuse (Halford et al., 2020). In fact, data from 715,227 reports in helplines across Germany suggested a highly significant increase in physical and sexual violence during the first week of the lockdown, which gradually decreased (Armbruster & Klotzbücher, 2020; Table 2).

Intimate Partner Violence

According to Frank et al. (United Kingdom—data retrieved from UCL -University College London- COVID-19 Social Study, 2020), 11.3% of participants had experienced psychological or physical abuse on at least one occasion since lockdown began (Table 2). The odds ratio (OR) of moderate depressive symptoms was 5.34 (95% CI [5.15, 5.54]) for participants who had experienced abuse, and the OR of severe depressive symptoms associated with abuse was 13.16 (95% CI [12.95, 13.37]; Frank et al., 2020). Furthermore, Iob et al. using data from the same survey, indicated that 9% of participants experienced psychological or physical abuse during lockdown, while 50% of them had suicidal or self-harm thoughts and 25% of them had self-harm behaviors during the week before the survey (Table 2).

Moreover, COVID-19 lockdown raised worries about personal safety (i.e., abuse) which were associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms and also led to poor quality of sleep (Wright et al., 2020a, 2020b). In fact, worries about personal safety had the largest effect size in sleep quality (OR = 1.43; 95% CI [1.35, 1.53]) among all types of adversities (personal safety, access to medication employment, access to food, finances, and contracting COVID-19; Table 2). In Germany, data retrieved during the lockdown (April 1–15, 2020) implied that 5% of participants experienced interpersonal violence in verbal (98.4%), physical (41.9%), and/or sexual (30.2%) level (Jung et al., 2020). Furthermore, 77.3% of participants experienced more verbal violence than before, 19.5% more physical violence, and 11.1% more sexual violence (Table 2).

Child Abuse

In the United Kingdom, a 41% decrease in vulnerable child offense police reports was reported (Halford et al., 2020). In Valencia and Murcia, Spain, teachers participated in an online program in order to support their vulnerable students and prevent child abuse during the months of the lockdown (Roca et al., 2020). The teachers implemented six web-based actions, including dialogic workspaces, dialogic gatherings, class assemblies, dialogic pedagogical gatherings with teachers, mixed committees, and dynamization of social networks with preventive messages and the creation of a sense of community (Table 2). The program was considered successful and contributed to the prevention of child abuse. On the other hand, health care practitioners in London, UK, recorded a significant increase in the number of children that were diagnosed with abusive head trauma during COVID-19 lockdown compared to the previous 3 years (Sidpra et al., 2020; Table 2).

Asia-Pacific Region

Main Findings

The eligible studies from the Asia-Pacific region came from Australia and New Zealand (Biddle et al., 2020; Foster & Fletcher, 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2020; Pfitzner et al., 2020; Sibley et al., 2020; Table 2). As far as Australia is concerned, the domestic violence rate in March 2020 was 57.5 per 100,000 people, and in April 2020, it slightly decreased, with the corresponding rates for March and April 2019, to be presented as elevated compared to the previous years (2014–2018; 2014 26 per 100,000; and 2020 57.5 per 100,000 of population; Payne et al., 2020). Early reports in domestic violence cases presented an increase in the pandemic outbreak, as stated in another Australian study (Nguyen et al., 2020; Table 2).

Frontline workers and service providers in New South Wales, Australia, highlighted that domestic violence victims may face several difficulties: 65.2% of them were concerned regarding insufficient service availability, 49.2% supported that women prioritized material needs and concerns over their own safety, 44.9% noticed an escalation in domestic violence, 36.2% identified that there was an increase in women’s reports which was related to the COVID-19 crisis (e.g., financial difficulties), and 15.9% indicated that first-time violence incidents were noted during the COVID-19 pandemic (Foster & Fletcher, 2020; Table 2). The study was conducted at the first months of the outbreak of the pandemic (March 2020—Table 1).

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence during COVID-19 lockdown was salient to practitioners who were working with women; 59% of them recorded an increase in the frequency and 50% an increase in the severity of intimate partner violence during this period, respectively, in Victoria, Australia (Pfitzner et al., 2020; Table 2). As a matter of fact, the fear of partner abuse was highly observed in Australian women, particularly between 25 and 34 years old at the first months of the lockdown (Biddle et al., 2020). Surprisingly enough, the same survey concluded that men had the same fear as well. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown was also reflected by the fact that people in New Zealand were more positive toward enhancing support services for reducing and/or preventing domestic violence than they were before the lockdown (Sibley et al., 2020). Moreover, aboriginal females were more likely to face gender-based violence and be restricted by their partners or to be threatened by COVID-19 infection, making it impossible for them to reach help services, a fact that was observed from the first months of the pandemic (Nguyen et al., 2020; Table 2).

Africa

The findings regarding domestic violence in Africa during COVID-19 pandemic were limited and contradictory; in South Africa, overall violence during lockdown decreased due to a reduction in alcohol consumption, especially in poorer areas, whereas there was an increase in gender-based violence during the third week of the lockdown (Stiegler & Bouchard, 2020; Table 2). On the other hand, in Ghana, 8% of the participants in an online survey stated that they faced a higher risk of domestic violence during the lockdown (Asiamah et al., 2021—April 2020), while another study in South Africa (Nduna & Oyama, 2020) reported that between March 27 and April 16 (months of lockdown), a total of 442 gender-based violence related calls were received by Gender-Based Violence Command Center Call, in accordance with the general surge of gender-based violence during the national lockdown. Although alcohol intoxication was not easily recorded, it was considered a risk factor for intimate partner abuse in remote areas, with the police reporting more than 2,300 complaints of gender-based violence (Nduna & Oyama, 2020).

Multinational Studies

Main Findings

The report of World Vision (Huber, 2020) regarding calls to SOS hotlines for domestic violence during COVID-19 pandemic outbreak is quite revealing: There was an increase in domestic violence cases all over the world; more specifically, in Argentina, 25%; in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 22%; in Brazil, 18%; in Chile, 75%; in Cyprus, 47%; in France, 30%; in India, 32%; in Lebanon, 50%; in Mexico, 25%; in Montenegro, 27%; in Singapore, 33%; in Spain, 12%; and in the United States, 21.5% (Table 2). These cases were mostly referred to intimate partner violence. However, there was no significant change in Google search trends regarding abuse or domestic violence during COVID-19 confinement compared to the trends of 2019 (Knipe et al., 2020).

Child Abuse

Bearing in mind the increase in calls regarding domestic violence in SOS helplines during COVID-19 confinement, World Vision’s estimations (Huber, 2020) about the increase in the number of underaged victims (2–17 years old) exposed to any violence or severe violence are terrifying: in Africa, 11,488,186–18,381,098 more victims of child/adolescent abuse; in Asia, 3,577,839–5,724,542; in Latin America, 2,921,466–4,674,345; in Europe, 759,600–1,215,360; in North America, 2,009,722–3,215,554; and in Oceania, 32,010–51,216 (Table 2).

Risk of Bias

Concerning the cross-sectional studies, the majority of them scored intermediate scores (n = 14) in the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, while the others scored either high (n = 6) or low (n = 6). In some cases, the selection of the sample was not detailed. Accordingly, the nonresponder rate was not justified, although the tool (online questionnaires, helpline calls, and police reports) provided was described in detail but not validated. In most studies, the control of confounding factors was conducted through appropriate statistical analysis, but the assessment of the outcome suffered mainly from self-reporting. Furthermore, the six cohort studies provided good (n = 5) and fair quality (n = 1; Online Supplementary eTable 1).

Discussion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people faced new challenges, affecting them not only physically but also mentally and financially. Although home confinement gave the opportunity for families to be united, an increase in domestic violence was noted globally, during the first week of lockdown, according to this systematic review (Armbruster & Klotzbücher, 2020; Asiamah et al., 2021; Boserup et al., 2020; Foster & Fletcher, 2020; Frank et al., 2020; Huber, 2020; Jung et al., 2020; Leslie & Wilson, 2020; Mohler et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2020; Pfitzner et al., 2020; Piquero et al., 2020; Sanga & McCrary, 2020; Sidpra et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2020a, 2020b). Many factors contributed in the appearance of domestic violence through the years, with political, legal, economical, and cultural to be most frequent (Heise et al., 1999; Sokoloff & Pratt, 2005). The COVID-19 epidemic emerged as an aggravating factor to domestic violence, enhancing the preexisting problem. The “shadow pandemic” of violence against women became evident not only in fragile economic states and regions but also in strong ones (Desmidt & Neat, 2020). Rates seemed to decrease, as the pandemic continued, people adapted to the new reality and addressed for help (Brülhart & Lalive, 2020; Halford et al., 2020; Mclay, 2021; Sibley et al., 2020; Silverio-Murillo et al., 2020).

The appearance of DV through the years was enhanced by many factors with political, legal, economic, and cultural to be most frequent (Heise et al., 1999; Sokoloff & Pratt, 2005). In a multicountry study in 2006 including data from 15 countries around the world, the rates of physical and sexual abuse were from 4% to 54% with countries such as Thailand, Bangladesh, or Ethiopia to report sexual abuse more frequent (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006). Those findings incorporate the cultural and religious laws, which consider acceptable from husbands to control or chastise their wives. Moreover, according to previous data, in Latin America and United States, women faced simultaneously physical and sexual abuse or physical abuse only. Differences in domestic violence may appear in countries which are industrialized. Thus, the rates of DV were lower concerning countries that are not mainly due to better information and preventing measures (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). During periods of crisis, such as the Great Recession in the United States (Schneider et al., 2016) and European debt crisis in 2010 and after (Kyriakidou et al., 2019), an increase of intimate partner violence was noted, due to mainly economic instability and stressful environments (Curtis et al., 2000; Mansi et al., 2020; Parkinson & Zara, 2013; Schneider et al., 2016). Although the data including DV are enlightening, they describe only a small part of this issue, due to the lack of reporting or discrimination and labeling (Gqola, 2015).

Intimate violence may occur in many forms; verbal abuse seemed to be the most frequent, as stated in this systematic review (Frank et al., 2020; Jung et al., 2020). Not only an increase in intimate partner violence was noted but also depressive symptoms with suicidal, self-harm thoughts, and sleep disorders were observed (Ammerman et al., 2021; Asiamah et al., 2021; Boserup et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020; Iob et al., 2020; Pfitzner et al., 2020; Stiegler & Bouchard, 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2020a, Xiang et al., 2020). Fear of personal safety was diffusible in both genders, with women to be more restricted by their partners (Davis et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020); women were even threatened with COVID-19 infection by their partners if they did not obey (Nguyen et al., 2020). During the lockdown, women were burdened with more responsibilities, when schools closed and had to take care of the more fragile members of the family (Wenham et al., 2020). The lack of access to health services and support organizations inhibited many people to ask for help. The use of telehealth and helplines gave them the opportunity to speak out for their problems (van Gelder et al., 2020). However, the alertness and training of health providers, in order to recognize early signs of abuse, is of great importance (McCloskey et al., 2007; Sanchez et al., 2020).

Children could not be unaffected by the new reality with school closure to transform their everyday activities. According to this systematic review, individual studies reported a decrease in child abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic (Baron et al., 2020; Halford et al., 2020), but Huber (2020) estimated increased child abuse rates. The school was considered to be a protective environment for many children, with educational personnel to be the first ones to complain about abuse (Souza Marques et al., 2020). Thus, those decreased rates may be misleading. The home confinement created the “behind closed doors” phenomenon, where children had to face changes in their home due to changes in their parents’ behavior (Roje Dapic et al., 2020). Practitioners during the COVID-19 lockdown observed that there was an increase in abusive head traumas in children (Sidpra et al., 2020) which was similarly reported during the economic crisis in 2009 in the United States, in relation to the “shaken baby syndrome” (Berger et al., 2011).

Moreover, although traditionally there is a correlation between domestic violence and homicide cases (Iratzoqui & McCutcheon, 2018), during the COVID-19 confinement measures, there was a reduction in homicide, especially in women (Byard, 2021; Calderon-Anyosa & Kaufman, 2020), despite the increase of intimate partner violence and domestic violence in general. This may be explained due to the fact that in general in most cases where the victim is a woman, their body is found in public places—where the access now is limited due to COVID-19 measures—rather than at home (Calderon-Anyosa & Kaufman, 2020). A closer look, however, reveals that femicide rate (homicide by men against women because of their sex) seems to have increased. In the United Kingdom, for example, in March 2020, the cases of confirmed femicide were three times more compared to the average cases of the same period during the last 10 years, while in Argentina, Spain, and Turkey, the number of femicide cases are worrisome (Weil, 2020).

Domestic violence is an issue facing methodological limitations because of its context. In this systematic review, data were derived mainly from police and helpline reports, which are susceptible to bias due to human factors, as self-report statements. People calling in helplines may report different issues (such mental or health issues), including domestic violence. So, discrimination between the occurrence of domestic violence during COVID-19 pandemic and a preexisting condition could not be controlled. Furthermore, in many cases, there was no clarification whether domestic violence referred to intimate partner violence or child abuse with no distinction between age ranges. However, police reports might describe a small part of reality, because many victims are afraid of reporting domestic violence to the authorities, due to discrimination and labeling (Gqola, 2015). Furthermore, not all police calls for domestic violence were reported or there were changes in reporting, due to lack of evidence (Beland et al., 2020).

Due to racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic discrimination, a global prevention program is difficult to occur, but some interventions can be implemented (αlhabib et al., 2010). Although the COVID-19 restriction measures limited access to help, the use of international code “mask-19” from victims triggered the immediate response of pharmacists for assistance (Bukhari et al., 2020). The use of technology, not only for entertainment or health issues, promoted in the emergence of apps and phone numbers specifically used from domestic violence victims (Gasparikova & Djurickovic, 2020; Tandon & Swaminathan, 2020). Furthermore, several campaigns via television or social media have been fostered by world organizations, nongovernmental organizations, or via state funding, raising public awareness in domestic violence victims, professionals, and in every individual in general (e.g., Council of Europe campaign, hotlines in various countries).

There were, however, minimal data for domestic violence among queer, transgender, and bisexual people during the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting the limited data in domestic violence in these groups in general (Konnoth, 2020). While the “same-sex” violence in gay and lesbian couples had been addressed in the past, the nonheterosexual people were unpresented (Kaschak, 2001). In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first article that systematically reviews and provides summaries on the global trends of domestic violence and highlights the fact that domestic violence is a considerable issue imposed by the COVID-19 epidemic to a worldwide context. The home confinement isolated victims with their perpetrators, resulting in increased violence but also decreased reports. Children were left alone in cases of violence as the school’s closure interrupted direct contact with their teachers. The fact that there is an increase in reports of domestic violence in many countries must be taken in serious consideration as it seems that many victims remained “hidden.” Prevention measures and supporting programs should be established in order to minimize such issues in the future.

Critical Findings

Domestic violence is a considerable issue imposed by COVID-19 epidemic to a worldwide context

The home confinement led to constant contact between perpetrators and victims, resulting in increased violence but also decreased reports

School closures isolated students at home and probably contributed to the decrease of child abuse reports

An increase was observed in helplines calls

Implications

Prevention measures and supporting programs should be established in order to protect domestic violence victims during the pandemic

School closures should be considered a factor which leads to child abuse increase

Helplines need to increase and strengthen

There is a need for helplines addressed especially to domestic violence

Domestic violence in many countries must be taken in serious consideration as it seems that many victims remained “hidden”

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-tva-10.1177_15248380211038690 for Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review by Anastasia Kourti, Androniki Stavridou, Eleni Panagouli, Theodora Psaltopoulou, Chara Spiliopoulou, Maria Tsolia, Theodoros N. Sergentanis and Artemis Tsitsika in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-tva-10.1177_15248380211038690 for Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review by Anastasia Kourti, Androniki Stavridou, Eleni Panagouli, Theodora Psaltopoulou, Chara Spiliopoulou, Maria Tsolia, Theodoros N. Sergentanis and Artemis Tsitsika in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

Author Biographies

Anastasia Kourti, MSc, is a primary school teacher/SEN teacher working in public schools in Greece and collaborates with the Adolescent Health Unit of Second Department of Pediatrics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. Her research focuses on cognitive psychology as well as in children and adolescents’ mental health and well-being. Furthermore, she has published several educational books for children with learning difficulties.

Androniki Stavridou, MSc, is a military psychologist (first lieutenant), which collaborates with the Adolescent Health Unit of Second Department of Pediatrics, “P. & A. Kyriakou” Children’s Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. Her research work focuses on the importance of early detection and treatment of mental health issues in the army. She is interested in the psychosocial consequences of COVID-19 pandemic.

Eleni Panagouli, MD, PhD, is a pediatrician and academic fellow at the Adolescent Health Unit of the Second Department of Pediatrics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and a research associate in the Department of Anatomy, Medical School of Athens. Her research interest focuses on anatomy, pediatrics, and adolescent health. She is interested in the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic in all fields.

Theodora Psaltopoulou, MD, PhD, is a Professor in the Department of Clinical Therapeutics, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. Her research fields are epidemiology, public health, preventive medicine cancer epidemiology, meta-analysis, research methodology, biostatistics and the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic in all fields.

Chara Spiliopoulou, MD, PhD, is a Professor of forensic medicine and Toxicology at University of Athens, Greece. Her research interests include forensic medicine, domestic violence, abuse, toxicology, and bioethics. Her research fields include domestic violence, especially during the COVID-19 pandemics, not only in high risk populations (children, adolescents, or elderly) but also in general.

Maria Tsolia, MD, PhD, is a Professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases of the second pediatric clinic of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Her research focuses on the epidemiology of vaccine-preventable infections, respiratory tract infections, and tuberculosis.

Theodoros N. Sergentanis, MD, PhD, is an academic fellow in the Department of Clinical Therapeutics, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece, and a collaborator of the Adolescent Health Unit of the Second Department of Pediatrics. His research fields are cancer epidemiology, meta-analysis, research methodology, study design, and biostatistics. He is interested in the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic.

Artemis Tsitsika, MD, PhD, is an Assοciate Professor in pediatrics/adolescent health at the Adolescent Health Unit of the Second Department of Pediatrics of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Her research interest focuses on adolescent health, eating disorders, obesity, and sexuality issues. She is interested in the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic in all fields.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Anastasia Kourti and Androniki Stavridou contributed equally to this article as first authors. Additionally the senior authors Theodoros N. Sergentanis and Artemis Tsitsika contributed equally to this article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Eleni Panagouli  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8764-1059

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8764-1059

Supplemental Material: The supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Alhabib S., Nur U., Jones R. (2010). Domestic violence against women: Systematic review of prevalence studies. Journal of Family Violence, 25(4), 369–382. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman B. A., Burke T. A., Jacobucci R., McClure K. (2021). Preliminary investigation of the association between COVID-19 and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the U.S. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 134, 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster S., Klotzbücher V. (2020). Lost in lockdown? COVID-19, social distancing, and mental health in Germany. Diskussionsbeiträge. No. 2020-04. Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Wilfried-Guth-Stiftungsprofessur für Ordnungs- und Wettbewerbspolitik, Freiburg i. Br. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/218885 [Google Scholar]

- Asiamah N., Opuni F. F., Mends-Brew E., Mensah S. W., Mensah H. K., Quansah F. (2021). Short-term changes in behaviors resulting from COVID-19-related social isolation and their influences on mental health. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(1), 79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron E. J., Goldstein E. G., Cullen W. (2020). Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. Journal of Public Economics, 190, 104258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beland L. P., Brodeur A., Haddad J., Mikola D. (2020). Covid-19, family stress and domestic violence: Remote work, isolation and bargaining power. GLO Discussion Paper, 571. Global Labor Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Berger P. R., Fromkin B. J., Stutz H., Makoroff K., Scribano V. P., Fekdman K., Tu L., Fabio A. (2011). Abusive head trauma during a time of increased unemployment: A multicenter analysis. Pediatrics, 128, 637–643. 10.1542/peds.2010-2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle N., Edwards B., Gray M., Sollis K. (2020). Mental health and relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mental Health and Relationships. Retrieved July 22, 2020, fromhttps://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2020/7/Mental_health_and_relationships.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. (2020). Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(12), 2753–2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. M., Doom J., Watamura S., Lechuga-Pena S., Koppels T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brülhart M., Lalive R. (2020). Daily suffering: Helpline calls during the Covid-19 crisis. Covid Economics, 19,143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari N., Rasheed H., Nayyer B., Babar Z. (2020). Pharmacists at the frontline beating the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice, 13, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byard R. (2021). Geographic variability in homicide rates following the COVID-19 pandemic. [Epub ahead of print]. Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology, 1–3. https://doi.org.10.1007/s12024-021-00370-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Anyosa A., Kaufman J. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. Preventive Medicine, 143, 106331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]