Abstract

This cross-sectional study sought to quantify the frequency of change in race category in the electronic medical record (EMR) of a pediatric population.

The collection, use, and meaning of race in biomedical research is complicated by the tension between the requisite interrogation of health disparities associated with race and the risk of continued insinuation of race as a biologic entity when interspersed with health outcomes.1,2,3 As a social construct, the literature supports that, assessed at the individual level, race as a category has a nontrivial change with repeated assessment. For instance, 12.5% of childrens’ US census records had a changed racial category from 2000 to 2010 at the individual response level.4 Thus, given the duality of race as important yet mutable, we sought to quantify the frequency of change in race category in the electronic medical record (EMR) of a pediatric population.

Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted within a large academic pediatric health care system. The study was not considered human research by the institutional review board of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania. Demographic data were abstracted from a shared EMR (EpicCare; Epic Systems). Eligibility criteria included age younger than 18 years within the study period (January 1, 2012, to September 20, 2021) and at least 1 system encounter with demographic data entry. EMR race categories (which did not change during the study period) were American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Indian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, other, White, or refused. Multiracial identity occurred when 2 or more races were selected. Primary analysis excluded records with Hispanic identity given literature supporting differential drivers of racial identity (evidence suggests that Hispanic individuals have differential racial group selection practices, possibly due to a stronger linkage between racial and ethnic identity).5 From current documented race, we calculated the percentage of individuals with previous change in race category. Results were stratified by system encounter count (1-4, 5-15, or ≥16). Data cleaning and analyses were conducted using R, version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and implementing the bigrquery, tidyverse, stargazer, circlize, and irr packages. This study followed the STROBE reporting guideline.

Results

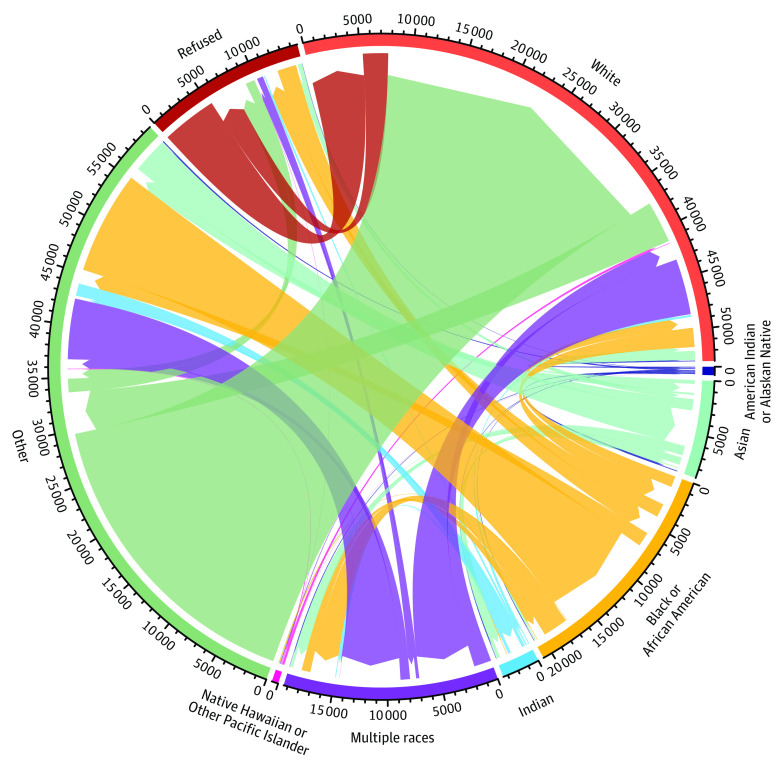

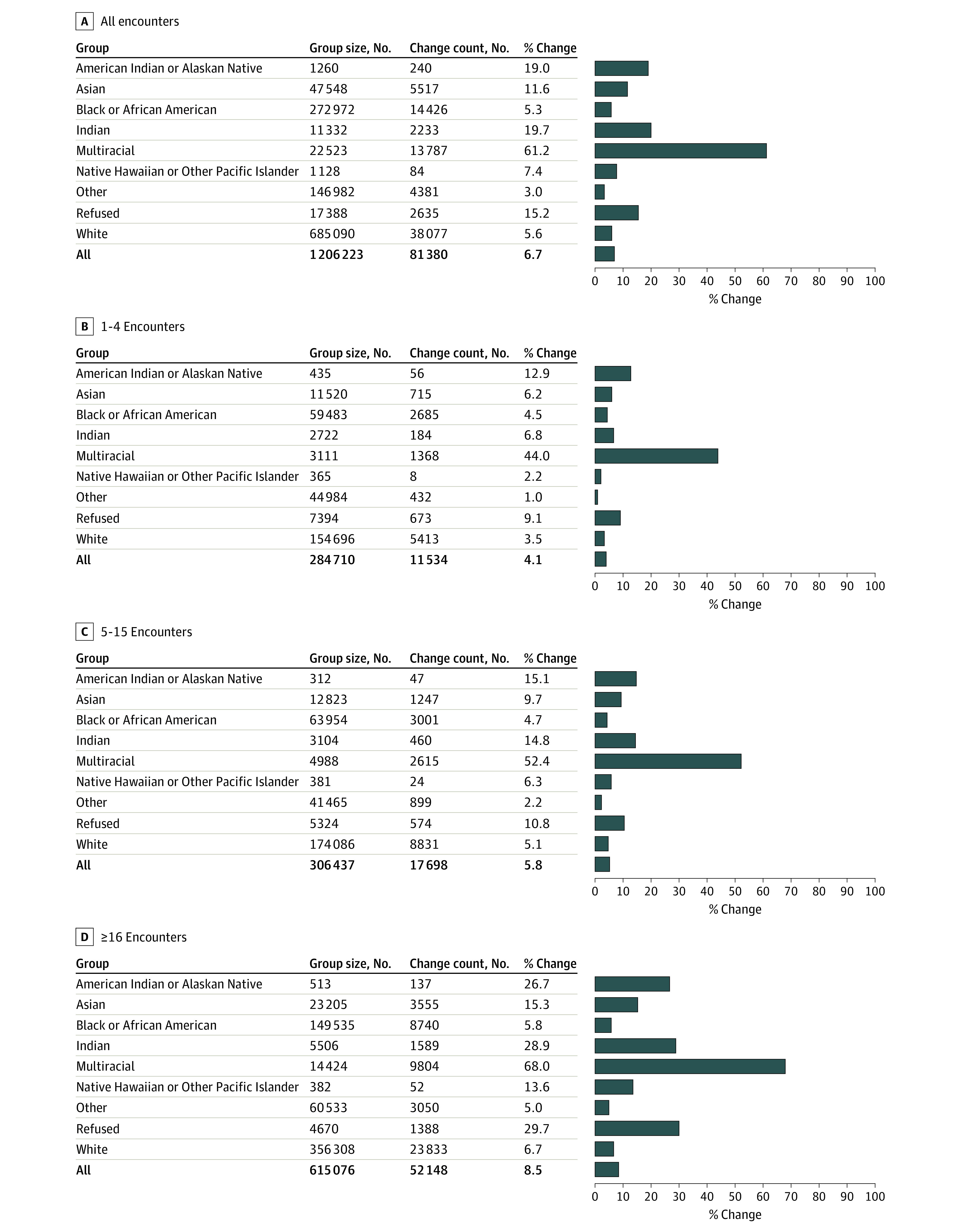

Within the total cohort (N = 1 206 223), 81 380 individuals (6.7%) had at least 1 change in race category. Within each race category, the percentage of individuals with a prior change ranged from 3% for other (4381 of 146 982) to 61.2% for multiracial individuals (13 787 of 22 523) (Figure 1A). There were bidirectional connections between almost all race categories (Figure 2). When stratified by encounter counts, the proportion of the population with a change in race category increased with increasing encounter count from 4.1% (1-4 encounters) to 8.5% (≥16 encounters) (Figure 1B-D) across all race categories. Sensitivity analysis within an all-ethnicity cohort demonstrated similar overall change in race category (5.9%).

Figure 1. Overall and Health System Use Stratified Changes in Race Category in the Electronic Medical Record.

Counts of individuals in racial groups and those with prior change, stratified on health system use: overall (all encounters [A]), low (1-4 encounters [B]), moderate (5-15 encounters [C]), and high (≥16 encounters [D]). Racial categories were stratified by 7 single race categories, composed multiracial, and refused. “Other” indicates other race not listed.

Figure 2. Race Category Patterns and Directions of Change.

Chord diagram of magnitude and direction of 90 764 race category changes. Individuals may be represented more than once. The pointed end of the color arc represents the destination group, and the flat end of the color arc represents the origin group. “Other” indicates other race not listed.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of longitudinal pediatric EMR data, change in race category was not uncommon, increased with encounter count, and was more prominent in multiracial and low-frequency racial groups (ie, groups with low numbers; more specifically, American Indian or Alaska Native, Indian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or multiracial). Users of EMR data should be aware that a change in race category may occur at the individual level, as seen in other data, such as social and behavioral determinants of health.6

Several factors may be associated with a change in race category, including data collection methods, choice architecture of racial categories, and/or change in self-identity, with lack of putative information a limitation of this study.1 These factors may differ based on ethnicity, which limits the generalizability of these results. Institutions should ensure accuracy of EMR race category data by using gold standard data collection methods, typically self-report. Nonrandom variation in race categories may represent a previously unappreciated source of confounding in studies assessing associations of racism with health outcomes. The influence of this variation may be further pronounced in queries related to low-frequency racial groups or multiplicative effects comparing across data acquisitions. Confounding can be addressed methodologically by modeling random change dynamics or considering race as a time-varying covariate in longitudinal studies.

In conclusion, race, a social construct, may change with repeated acquisition across time and setting. The cumulative, even if unintentional, reinforcement of race as a fixed biologic structure is harmful, and there is an urgent need for recalibration of its use.1,2,3

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Borrell LN, Elhawary JR, Fuentes-Afflick E, et al. Race and genetic ancestry in medicine—a time for reckoning with racism. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):474-480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2029562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ioannidis JPA, Powe NR, Yancy C. Recalibrating the use of race in medical research. JAMA. 2021;325(7):623-624. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chokshi DA, Foote MMK, Morse ME. How to act upon racism—not race—as a risk factor. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(2):e220548. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liebler CA, Porter SR, Fernandez LE, Noon JM, Ennis SR. America’s churning races: race and ethnicity response changes between Census 2000 and the 2010 Census. Demography. 2017;54(1):259-284. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0544-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Compton E, Bently M, Ennis S, Rastogi S. 2010 Census race and hispanic origin alternative questionnaire experiment. United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/2010/program-management/cpex/2010-cpex-211.html

- 6.Feller DJ, Zucker J, Walk OBD, Yin MT, Gordon P, Elhadad N. Longitudinal analysis of social and behavioral determinants of health in the EHR: exploring the impact of patient trajectories and documentation practices. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2020;2019:399-407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement