Abstract

Objective

Racial and ethnic minority enrollees in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans tend to be in lower‐quality plans, measured by a 5‐star quality rating system. We examine whether differential access to high‐rated plans was associated with this differential enrollment in high‐rated plans by race and ethnicity among MA enrollees.

Data Sources

The Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File and MA Landscape File for 2016.

Study Design

We first examined county‐level MA plan offerings by race and ethnicity. We then examined the association of racial and ethnic differences in enrollment by star rating by controlling for the following different sets of covariates: (1) individual‐level characteristics only, and (2) individual‐level characteristics and county‐level MA plan offerings.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Not applicable

Principal Findings

Racial and ethnic minority enrollees had, on average, more MA plans available in their counties of residence compared to White enrollees (16.1, 20.8, 20.2, vs. 15.1 for Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and White enrollees), but had fewer number of high‐rated plans (4‐star plans or higher) and/or more number of low‐rated plans (3.5‐star plans or lower). While racial and ethnic minority enrollees had lower enrollment in 4–4.5 star plans than White enrollees, this difference substantially decreased after accounting for county‐level MA plan offerings (−9.1 to −0.5 percentage points for Black enrollees, −15.9 to −5.0 percentage points for Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees, and −12.7 to 0.6 percentage points for Hispanic enrollees). Results for Black enrollees were notable as the racial difference reversed when we limited the analysis to those who live in counties that offer a 5‐star plan. After accounting for county‐level MA plan offerings, Black enrollees had 3.2 percentage points higher enrollment in 5‐star plans than White enrollees.

Conclusions

Differences in enrollment in high‐rated MA plans by race and ethnicity may be explained by limited access and not by individual characteristics or enrollment decisions.

Keywords: access to care, health disparity, high‐quality plan, Medicare Advantage, race, traditional Medicare

What is known on this topic

Prior research has found that racial and ethnic minority individuals enrolled in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are less likely to be enrolled in plans with high‐quality ratings (4‐star plans or higher) and more likely to be enrolled in MA plans with low‐quality ratings (3.5‐star plans or lower) than White enrollees.

This finding has been interpreted as mainly indicating that racial and ethnic minority enrollees had lower awareness or willingness to pay for high‐rated plans than White enrollees.

What this study adds

We examined whether racial and ethnic differences in enrollment in MA plans with high‐star ratings were explained by differential access to MA plans with high‐star ratings.

We showed new evidence that high‐rated plans were relatively less available to racial and ethnic minority enrollees than White enrollees had and that racial and ethnic disparities in enrollment by star rating were driven by differential access to high‐rated plans.

Policymakers should consider ways to ensure that all Medicare beneficiaries have access to high‐rated MA plans.

1. INTRODUCTION

Enrollment in Medicare Advantage (MA), the segment of the Medicare program run by private insurance companies receiving capitated payments from the government, has been increasing over the past decade. Overall, the percentage of Medicare enrollees in MA increased from 23% in 2009 to 35% in 2018, but enrollment growth has been more pronounced among racial and ethnic minority enrollees (1.7%, 1.6%, 1.6%, and 1.0% for the average annual growth rate in MA enrollment among Black, Asian, Hispanic, and White enrollees between 2009 and 2018). 1 However, racial and ethnic minority enrollees had worse patient experience and clinical care measures than White enrollees in MA. 2 Racial and ethnic disparities were also more variable for clinical care measures. Specifically, Black enrollees received worse clinical care than White enrollees for 20 out of 44 measures. Hispanic enrollees received worse clinical care than White enrollees for 19 measures. Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees received worse clinical care than White enrollees for six measures. This suggests the need of developing interventions targeted to improve care for racial and ethnic minority enrollees in MA. Thus, achieving racial equity in health and health care should be a priority for MA plans while addressing the needs of racial and ethnic minority groups. 2

Evidence suggests that substantial racial and ethnic disparities persist in enrollment in high‐quality MA plans. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced a 5‐star quality rating system to improve care quality while helping enrollees compare and choose high‐quality MA plans. Star ratings are measured based on over 40 performance measures. Since 2014, MA contracts with 4 stars or higher have received additional quality bonus payments. However, prior research has found that racial and ethnic minority enrollees were less likely to be enrolled in high‐quality plans (4‐star plans or higher) and more likely to be enrolled in low‐quality plans (3.5‐star plans or lower) than White enrollees (55.3%, 42.2%, 59.9%, and 69.8% for enrollment in 4‐star plans or higher among Black, Asian, Hispanic, and White enrollees and 34.9%, 36.8%, 27.7%, and 22.4% for enrollment in 3.5‐star plans or lower among Black, Asian, Hispanic, and White enrollees). 1 , 3 Also, star ratings were less strongly associated with enrollment for racial and ethnic minority enrollees than White enrollees, especially for Black enrollees (4.6, 7.9, and 11.5 percentage points increase in plan enrollment per 1‐star increase for Black, Hispanic, and White enrollees). 4 Identifying the underlying mechanisms for differential enrollment by race and ethnicity in high‐quality MA plans are of high policy relevance, but little is known.

Several structural features in payment adjustment and star‐rating could incentivize MA plans to discourage enrollment among racial and ethnic minority beneficiaries, potentially creating and perpetuating structural racism in health and health care. MA plan payments have traditionally been adjusted only minimally for clinical characteristics of enrollees, leading to overpayments for healthier enrollees and underpayments for sicker enrollees. 5 , 6 , 7 This phenomenon may be more pronounced among racial and ethnic minority enrollees due to complex health conditions. 8 , 9 , 10 As payments to MA plans do not account for race or ethnicity as a social risk factor, 11 this may lead to systematic underpayments for racial and ethnic minority enrollees. In addition, MA plans receive a bonus based on a composite 5‐star rating score that reflects each contract's performance. Since star ratings do not account for enrollee characteristics, this may create an incentive for MA plans to avoid enrolling individuals who are perceived to lower the plans' quality score. 12 , 13 One way to achieve this is to avoid offering an MA plan in counties with more racial or ethnic minorities. Consequently, differential enrollment in high‐quality plans by race and ethnicity may be attributable to differential access to high‐quality plans.

In this study, we examined the degree to which access to high‐quality plans, measured by star ratings, explains racial and ethnic disparities in enrollment in high‐quality MA plans.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data and study sample

Our primary data sources were the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) for enrollee characteristics and the MA Landscape File for plan characteristics in 2016. We also used the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files to obtain information on MA enrollee's health status. Since 2008, the MedPAR has included claims from MA enrollees who were admitted to hospitals that receive Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital payments or graduate medical education hospitals, which accounts for 92% of all Medicare discharges from MA‐reporting hospitals. 14

Using the data, we first identified Medicare enrollees 65 years or older with 12 months of continuous enrollment in MA plans. Our sample was limited to the largest four racial and ethnic groups (White, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic). We excluded those in special needs plans (SNP) or Programs of All‐Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) due to different decision process and characteristics; those who younger than 65 years of age and those whose original Medicare eligibility was attributable to end‐stage renal disease due to different care needs, leading to enrollment in MA plans with different decision process and characteristics such as SNPs; those who died at any point in 2016 to avoid biases attributable to incomplete follow‐up and end‐of‐life health care use; and those in plans that were too small or too new to have star ratings as these plans complicate the interpretation of findings.

2.2. Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were access to and enrollment in MA plans by star rating. To measure access, we constructed county‐level measures of the number of MA plan offerings overall as well as by several dimensions that have been shown to be important determinants of plan choice 15 , 16 : star rating (2–2.5, 3–3.5, 4–4.5, or 5), plan type (health maintenance organization, local preferred provider organization, regional preferred provider organization, or other), monthly plan premium ($0, >$0–$50, >$50–$100, or >$100), and maximum out‐of‐pocket limit ($0, >$0–$3000, >$4500–$6000, or >$6000). To measure MA enrollment at the individual level, we constructed binary variables indicating whether the individual was enrolled in each level of each plan characteristic described above.

2.3. Independent variables

Our primary independent variables were race and ethnicity. We used the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) race and ethnicity code to more accurately identify non‐Hispanic White, non‐Hispanic Black, non‐Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic. 17 This variable was developed to enhance classification of Hispanics and Asians/Pacific Islanders by utilizing lists of Hispanic and Asians/Pacific Islander names from the US Census and simple geography. Prior research assessed the sensitivity and specificity of the RTI race and ethnicity code compared with self‐reported race and ethnicity data and found that the variable has high sensitivity and specificity. 18 To control for differences in individual‐level characteristics, we included age, sex, dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and (unstandardized) hierarchical condition category (HCC) risk scores. We used the CMS‐HCC risk adjustment model to estimate HCC risk scores, but only used diagnosis codes from the MedPAR.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We first summarized outcome and independent variables by race and ethnicity. For analyses using county‐level MA plan offering as an outcome, we reported unadjusted values. For analyses using individual‐level MA enrollment status as an outcome, we conducted a linear probability model (LPM) of enrollment by star rating. To examine whether differential access to high‐rated plans was associated with differential enrollment in high‐rated plans by race and ethnicity, we conducted two separate LPMs by controlling for the following different sets of covariates: (1) individual‐level characteristics only, and (2) individual‐level characteristics and county‐level plan offerings. Then, we reported the differences in the adjusted outcome among Black enrollees, Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees, and Hispanic enrollees relative to White enrollees. If findings from the two LPMs differ by race or ethnicity, this indicates that differential enrollment by race or ethnicity may be partly attributable to differential access to MA plans. We used an LPM as main analysis because it allows us to produce comparable findings between the two sets of analyses and due to its ease of use, especially in the presence of a large number of fixed effects. We also conducted the analysis described above by limiting to those in counties with a 5‐star plan and those in counties without a 4‐star plan or higher. We conducted several sensitivity analyses to examine robustness of our findings. First, there may be concerns about measurement error in estimating HCC risk score among MA enrollees because we only used diagnosis codes from the MedPAR. Thus, we conducted the analysis described above by excluding HCC risk scores. Second, there may be county‐level characteristics that might be related to differential access to and enrollment in MA plans. Thus, we performed the LPM while adjusting for individual‐level characteristics, county‐level plan offerings, and county‐fixed effects.

3. RESULTS

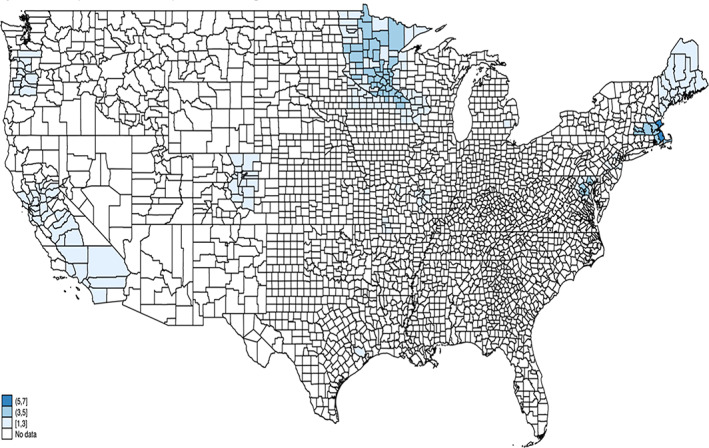

We included a total of 8,569,965 MA enrollees (6,488,700 White enrollees, 772,880 Black enrollees, 334,744 Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees, and 973,641 Hispanic enrollees) (Table 1). Racial and ethnic minority enrollees were more likely to be Medicare‐Medicaid dual eligible than White enrollees (18.0%, 18.6%, and 15.7%, vs. 6.7% for Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and White enrollees). However, racial and ethnic differences in other characteristics were relatively small, including HCC risk scores. Our unadjusted analyses showed that, compared to White enrollees, racial and ethnic minority enrollees were more likely to enroll in 2–2.5 and 3–3.5 star plans, in health maintenance organizations, and in plans with zero monthly premiums, and less likely to enroll in 4–4.5 star plans. Enrollment in 5‐star plans was lower among Black enrollees than White enrollees, and higher among Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic enrollees compared to White enrollees (6.2%, 10.7%, 19.4%, vs. 9.4% for Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and White enrollees). Figure 1 shows county‐level availability of 5‐star MA plans.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for outcome and independent variables among Medicare Advantage enrollees by race and ethnicity

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | White (n = 6,488,700) | Black (n = 772,880) | Asian and Pacific Islander (n = 334,744) | Hispanic (n = 973,641) |

| Age | ||||

| 65–69 | 1,627,386 (25.1) | 238,202 (30.8) | 276,764 (28.4) | 106,896 (31.9) |

| 70–74 | 1,876,547 (28.9) | 218,843 (28.3) | 280,108 (28.8) | 96,953 (29.0) |

| 75–79 | 1,298,044 (20.0) | 152,089 (19.7) | 193,908 (19.9) | 61,668 (18.4) |

| 80–84 | 865,707 (13.3) | 92,281 (11.9) | 121,090 (12.4) | 35,473 (10.6) |

| ≥85 | 821,016 (12.7) | 71,465 (9.2) | 101,771 (10.5) | 33,754 (10.1) |

| Female | 2,763,579 (42.6) | 296,583 (38.4) | 439,685 (45.2) | 154,006 (46.0) |

| Dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid | 434,019 (6.7) | 138,983 (18.0) | 181,488 (18.6) | 52,464 (15.7) |

| Risk scores a | ||||

| 0–0.3 | 613,344 (9.5) | 71,050 (9.2) | 97,831 (10.0) | 39,139 (11.7) |

| >0.3–0.5 | 3,633,446 (56.0) | 425,792 (55.1) | 543,333 (55.8) | 200,156 (59.8) |

| >0.5–1.0 | 1,716,906 (26.5) | 209,614 (27.1) | 276,465 (28.4) | 81,956 (24.5) |

| >1.0–2.0 | 308,081 (4.7) | 36,834 (4.8) | 33,710 (3.5) | 7927 (2.4) |

| >2.0 | 216,923 (3.3) | 29,590 (3.8) | 22,302 (2.3) | 5566 (1.7) |

| MA enrollment by star rating | ||||

| 2.0–2.5 stars | 20,354 (0.3) | 17,931 (2.3) | 2637 (0.3) | 3900 (1.2) |

| 3.0.3–5 stars | 1,590,820 (24.5) | 269,302 (34.8) | 350,413 (36.0) | 99,825 (29.8) |

| 4.0–4.5 stars | 4,265,379 (65.7) | 437,923 (56.7) | 516,838 (53.1) | 166,213 (49.7) |

| 5.0 stars | 612,147 (9.4) | 47,724 (6.2) | 103,753 (10.7) | 64,806 (19.4) |

| MA enrollment by plan type | ||||

| HMO | 4,439,062 (68.4) | 583,328 (75.5) | 880,466 (90.4) | 280,015 (83.7) |

| Local PPO | 1,345,548 (20.7) | 102,821 (13.3) | 51,898 (5.3) | 41,540 (12.4) |

| Regional PPO | 580,338 (8.9) | 76,099 (9.8) | 37,457 (3.8) | 7581 (2.3) |

| Other b | 123,752 (1.9) | 10,632 (1.4) | 3820 (0.4) | 5608 (1.7) |

| MA enrollment by monthly plan premium | ||||

| $0 | 2,736,553 (42.2) | 436,971 (56.5) | 718,255 (73.8) | 195,659 (58.5) |

| >$0–$50 | 1,558,429 (24.0) | 207,366 (26.8) | 168,187 (17.3) | 61,675 (18.4) |

| >$50–$100 | 1,285,725 (19.8) | 95,085 (12.3) | 62,250 (6.4) | 46,635 (13.9) |

| >$100 | 907,993 (14.0) | 33,458 (4.3) | 24,949 (2.6) | 30,775 (9.2) |

| MA enrollment by maximum OOP limit | ||||

| $0–$3000 | 383,117 (5.9) | 33,294 (4.3) | 95,501 (9.8) | 29,204 (8.7) |

| >$3000–$4500 | 1,891,033 (29.1) | 164,222 (21.2) | 438,654 (45.1) | 135,749 (40.6) |

| >$4500–$6000 | 1,724,646 (26.6) | 192,948 (25.0) | 164,000 (16.8) | 81,444 (24.3) |

| >$6000 | 2,489,904 (38.4) | 382,416 (49.5) | 275,486 (28.3) | 88,347 (26.4) |

Abbreviations: MA, Medicare Advantage; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred provider organization; OOP, out‐of‐pocket.

Measure risk scores based on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services‐Hierarchical Condition Category risk adjustment model, but does not account for age, sex, and dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid in our model.

Include private fee‐for‐service plans, cost‐based plans, and Medical Savings Account plans.

FIGURE 1.

County‐level availability of 5‐star MA plans. No data indicate that 5‐star MA plans were not available [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Racial and ethnic minority enrollees had, on average, more MA plans available in their counties of residence compared to White enrollees (16.1, 20.8, 20.2, vs. 15.1 for Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and White enrollees), but had fewer high‐rated plans and/or more low‐rated plans available (Table 2). Specifically, there were two distinct patterns of county‐level plan offerings by star rating. First, Black enrollees had, on average, more low‐rated plans (0.3 vs. 0.2 for 2–2.5 star plans and 8.1 vs. 5.5 for 3–3.5 star plans) and fewer high‐rated plans than White enrollees (7.4 vs. 9.0 for 4–4.5 star plans and 0.3 vs. 0.5 for 5‐star plans). Second, Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic enrollees had a similar number of high‐rated plans available in their counties of residence compared to White enrollees (9.1 and 9.3 vs. 9.0 for 4–4.5 star plans and 0.5 and 0.9 vs. 0.5 for 5‐star plans), but low‐rated plans were more available, especially for 3–3.5 star plans (11.1 and 9.7 vs. 5.5).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Medicare Advantage plans available to racial and ethnic enrollees

| Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | White | Black | Asian and Pacific Islander | Hispanic |

| Total number of MA plans | 15.1 (8.0) | 16.1 (9.2) | 20.8 (9.3) | 20.2 (11.1) |

| Number of MA plans by star rating | ||||

| 2–2.5 stars | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.8) |

| 3–3.5 stars | 5.5 (5.4) | 8.1 (6.8) | 11.1 (6.2) | 9.7 (7.9) |

| 4–4.5 stars | 9.0 (5.5) | 7.4 (5.0) | 9.1 (5.0) | 9.3 (5.3) |

| 5 stars | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.9 (1.0) |

| Number of MA plans by plan type | ||||

| HMO | 9.5 (7.5) | 10.7 (8.6) | 16.7 (9.9) | 16.8 (11.7) |

| Local PPO | 3.7 (3.0) | 3.4 (2.5) | 2.6 (2.2) | 2.4 (2.4) |

| Regional PPO | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.7) | 0.8 (1.3) |

| Other a | 0.5 (2.0) | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.8) | 0.2 (1.0) |

| Number of MA plans by monthly plan premium | ||||

| $0 | 5.2 (5.2) | 6.6 (5.9) | 11.3 (6.6) | 9.1 (7.2) |

| >$0–$50 | 3.8 (3.1) | 4.3 (3.4) | 5.7 (4.6) | 6.7 (5.1) |

| >$50–$100 | 3.0 (2.0) | 3.0 (2.0) | 2.3 (1.8) | 2.2 (2.1) |

| >$100 | 3.2 (2.9) | 2.2 (2.4) | 1.6 (1.6) | 2.2 (2.1) |

| Number of MA plans by maximum OOP limit | ||||

| $0 –$3000 | 0.9 (1.8) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.7 (2.2) | 2.0 (2.7) |

| >$3000–$4500 | 4.5 (4.2) | 4.5 (4.7) | 8.1 (5.2) | 6.4 (5.0) |

| >$4500–$6000 | 3.1 (2.1) | 3.0 (2.2) | 2.4 (1.9) | 3.0 (1.7) |

| >$6000 | 6.7 (5.0) | 7.9 (6.1) | 8.7 (5.4) | 8.7 (6.5) |

Abbreviations: MA, Medicare Advantage; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred provider organization; OOP, out‐of‐pocket.

Include private fee‐for‐service plans, cost‐based plans, and Medical Savings Account plans.

After controlling for individual‐level characteristics, racial and ethnic minority enrollees tended to have higher enrollment in low‐rated plans and/or lower enrollment in high‐rated plans than White enrollees (Table 3). Specifically, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic enrollees had 9.9 percentage points (95% CI: 9.8–10.0), 4.9 percentage points (95% CI: 4.7–5.0), and 11.1 percentage points (95% CI: 11.0–11.2) higher enrollment in 3–3.5 star plans and 9.1 percentage points (95% CI: −9.2 to −9.0), 15.9 percentage points (95% CI: −16.1 to −15.8), and 12.7 percentage points (95% CI: −12.8 to −12.6) lower enrollment in 4–4.5 star plans than White enrollees. However, there were different patterns in enrollment in 2–2.5 star and 5‐star plans by race and ethnicity. Black and Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees had 1.9 percentage points (95% CI: 1.9–2.0) and 0.8 percentage points (95% CI: 0.7–0.8) higher enrollment in 2–2.5 star plans than White enrollees, but there was almost no difference in enrollment in 2–2.5 star plans between Hispanic and White enrollees (−0.1 percentage points [95% CI: −0.1 to −0.1]). While Black enrollees had 2.7 percentage points (95% CI: −2.8 to −2.6) lower enrollment in 5‐star plans than White enrollees, Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic enrollees had 10.3 percentage points (95% CI: 10.2–10.4) and 1.8 percentage points (95% CI: 1.7–1.9) higher enrollment in 5‐star plans than White enrollees.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted rates of Medicare Advantage enrollment by race and ethnicity as well as plan characteristic

| Differences in adjusted rate of MA enrollment relative to White enrollees, percentage points (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusting for individual characteristics only a | Adjusting for individual characteristics a + county‐level plan offering b | |||||

| Characteristics | Black | Asian and Pacific Islander | Hispanic | Black | Asian and Pacific Islander | Hispanic |

| All counties | ||||||

| 2–2.5 stars | 1.9 (1.9 to 2.0) | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.8) | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.1) | 1.6 (1.6 to 1.6) | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.1) |

| 3–3.5 stars | 9.9 (9.8 to 10.0) | 4.9 (4.7 to 5.0) | 11.1 (11.0 to 11.2) | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.4) | 4.6 (4.5 to 4.8) | 1.7 (1.6 to 1.8) |

| 4–4.5 stars | −9.1 (−9.2 to −9.0) | −15.9 (−16.1 to −15.8) | −12.7 (−12.8 to −12.6) | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.4) | −5.0 (−5.2 to −4.8) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) |

| 5 stars | −2.7 (−2.8 to −2.6) | 10.3 (10.2 to 10.4) | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) | −0.7 (−0.7 to −0.6) | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.3) | −2.4 (−2.5 to −2.3) |

Abbreviation: MA, Medicare Advantage.

Include age, sex, race, dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid, and risk scores based on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services‐Hierarchical Condition Category risk adjustment model.

Include the following county‐level plan offerings as access to MA plans: total number of MA plans and numbers of MA plans by star rating (2–2.5, 3–3.5, 4–4.5, or 5), plan type (health maintenance organization, local preferred provider organization, regional preferred provider organization, or other), monthly plan premium ($0, >$0–$50, >$50–$100, or >$100), and maximum out‐of‐pocket (OOP) limit ($0, >$0–$3000, >$4500–$6000, or >$6000).

After accounting for both individual‐level characteristics and county‐level plan availability, differential enrollment by race and ethnicity substantially decreased (Table 3). Specifically, the magnitude of the change in enrollment in 3–3.5 and 4–4.5 star plans was notable. The difference in enrollment between Black enrollees and White enrollees almost disappeared, from 9.9 percentage points (95% CI: 9.8–10.0) to −0.5 percentage points (95% CI: −0.6 to −0.4) for 3–3.5 star plans, and from −9.1 percentage points (95% CI: −9.2 to −9.0) to −0.5 percentage points (95% CI: −0.6 to −0.4) for 4–4.5 star plans. The difference in enrollment between Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees and White enrollees decreased from 4.9 percentage points (95% CI: 4.7–5.0) to 4.6 percentage points (95% CI: 4.5–4.8) for 3–3.5 star plans and from −15.9 percentage points (95% CI: −16.1 to −15.8) to −5.0 percentage points (95% CI: −5.2 to −4.8) for 4–4.5 star plans. The difference in enrollment between Hispanic enrollees and White enrollees decreased from 11.1 percentage points (95% CI: 11.0–11.2) to 1.7 percentage points (95% CI: 1.6–1.8) for 3–3.5 star plans, and from −12.7 percentage points (95% CI: −12.8 to −12.6) to 0.6 percentage points (95% CI: 0.5–0.7) for 4–4.5 star plans. Also, the difference in enrollment in 5‐star plans among Black enrollees relative to White enrollees also decreased (−2.7 percentage points [95% CI: −2.8 to −2.6] to −0.7 percentage points [95% CI: −0.7 to −0.6]). However, the difference in enrollment in 5‐star plans among Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic enrollees relative to White enrollees reversed (10.3 percentage points [95% CI: 10.2–10.4] to −0.5 percentage points [95% CI: −0.6 to −0.3] among Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees and 1.8 percentage points [95% CI: 1.7–1.9] to −2.4 percentage points [95% CI: −2.5 to −2.3] among Hispanic enrollees). There were relatively marginal changes in enrollment in 2–2.5 star plans.

Our findings remained similar when we excluded HCC risk score from analysis (Table S1). Also, we found that adjusting for other county‐level plan characteristics via county‐fixed effects led to further decrease the racial and ethnic disparities in enrollment by star rating, but a similar pattern of results was found (Table S2).

Similar results were found when we limited the analysis to those who live in counties that offer a 5‐star plan, or the opposite, the counties that do not offer a 4‐star plan or higher (Table 4). Particularly, there were notable changes in the likelihood of enrollment in 3–3.5 and 4–4.5 star plans in counties with at least a 5‐star plan, both without and with accounting for county‐level plan availability (8.1 percentage points [95% CI: 7.9–8.3] to 0.9 percentage points [95% CI: 0.7–1.1] and −9.2 percentage points [95% CI: −9.5 to −8.9] to −4.1 percentage points [95% CI: −4.4 to −3.8] for enrollment in 3–3.5 and 4–4.5 star plans among Black enrollees, 12.6 percentage points [95% CI: 12.4–12.8] to 11.2 percentage points [95% CI: 11.0–11.4] and −9.6 percentage points [95% CI: −9.8 to −9.3] to −3,3 percentage points [95% CI: −3.6 to −3.1] for enrollment in 3–3.5 and 4–4.5 star plans among Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees, and 8.6 percentage points [95% CI: 8.5–8.7] to 5.8 percentage points [95% CI: 5.7–5.9] and −4.4 percentage points [95% CI: −4.6 to −4.2] to −0.3 percentage points [95% CI: −0.5 to −0.1] for enrollment in 3–3.5 and 4–4.5 star plans among Hispanic enrollees).

TABLE 4.

Adjusted rates of Medicare Advantage enrollment in counties with a 5‐star plan or counties without a 4‐star plan or higher by race and ethnicity as well as plan characteristic

| Differences in adjusted rate of MA enrollment relative to White enrollees, percentage points (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusting for individual characteristics only a | Adjusting for individual characteristics a + county‐level plan offering b | |||||

| Characteristics | Black | Asian and Pacific Islander | Hispanic | Black | Asian and Pacific Islander | Hispanic |

| Counties with a 5‐star plan | ||||||

| 2–2.5 stars | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.6) | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.1) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 1.2 (1.2 to 1.2) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.1) |

| 3–3.5 stars | 8.1 (7.9 to 8.3) | 12.6 (12.4 to 12.8) | 8.6 (8.5 to 8.7) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 11.2 (11.0 to 11.4) | 5.8 (5.7 to 5.9) |

| 4–4.5 stars | −9.2 (−9.5 to −8.9) | −9.6 (−9.8 to −9.3) | −4.4 (−4.6 to −4.2) | −4.1 (−4.4 to −3.8) | −3.3 (−3.6 to −3.1) | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.1) |

| 5 stars | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | −4.6 (−4.8 to −4.4) | −4.3 (−4.4 to −4.1) | 3.2 (2.9 to 3.4) | −9.0 (−9.3 to −8.8) | −5.6 (−5.8 to −5.4) |

| Counties without a 4‐star plan or higher | ||||||

| 2–2.5 stars | 4.9 (4.6 to 5.2) | 1.7 (0.2 to 3.1) | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.2) | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.8) | 1.0 (0.0 to 2.0) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.7) |

| 3–3.5 stars | −4.9 (−5.2 to −4.6) | −1.7 (−3.1 to −0.2) | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.5) | −1.6 (−1.8 to −1.3) | −1.0 (−2.0 to 0.0) | −0.5 (−0.7 to −0.2) |

| 4–4.5 stars | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) |

| 5 stars | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) |

Abbreviation: MA, Medicare Advantage.

Include age, sex, race, dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid, and risk scores based on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services‐Hierarchical Condition Category risk adjustment model.

Include the following county‐level plan offerings as access to MA plans: total number of MA plans and numbers of MA plans by star rating (2–2.5, 3–3.5, 4–4.5, or 5), plan type (health maintenance organization, local preferred provider organization, regional preferred provider organization, or other), monthly plan premium ($0, >$0–$50, >$50–$100, or >$100), and maximum out‐of‐pocket (OOP) limit ($0, >$0–$3000, >$4500–$6000, or >$6000).

We also found differential patterns of enrollment in 5‐star plans by race and ethnicity. After accounting for county‐level plan offerings, Black enrollees had 3.2 percentage points (95% CI: 3.2–3.4) higher enrollment in 5‐star plans than White enrollees. However, the difference in enrollment in 5‐star plans increased among Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic enrollees relative to White enrollees (−4.6 percentage points [95% CI: −4.8 to −4.4] to −9.0 percentage points [95% CI: −9.3 to −8.8] among Asian/Pacific Islander enrollees and − 4.3 percentage points [95% CI: −4.4 to −4.1] to −5.6 percentage points [95% CI: −5.8 to −5.4] among Hispanic enrollees). For those in counties without a 4‐star plan or higher, the difference in enrollment in 2–2.5 and 3–3.5 star plans among Black enrollees relative to White enrollees decreased (4.9 percentage points [95% CI: 4.6–5.2] to 1.6 percentage points [95% CI: 1.3–1.8] for enrollment in 2–2.5 star plans and −4.9 percentage points [95% CI: −5.2 to −4.6] to −1.6 percentage points [95% CI: −1.8 to −1.3] for enrollment in 3–3.5 star plans). However, the changes the likelihood of MA enrollment by star rating among Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic enrollees were small.

4. DISCUSSION

Consistent with prior research, 13 , 19 , 20 we found no evidence that the total number of MA plans was lower in counties with more racial and ethnic minorities. However, we showed new evidence that high‐rated plans were relatively less available and low‐rated plans were more available to racial and ethnic minority enrollees than White enrollees. This indicates suggestive evidence that high‐rated plans may have incentives not to operate in counties with more racial and ethnic minorities, who tend to have more clinical and social risk factors. Since quality‐based incentive payments do not sufficiently account for enrollee characteristics, 12 , 13 MA performance scores decrease as the proportion of enrollees with complex health and social needs increases. 21 Consequently, compared to plans with fewer sociodemographically disadvantaged enrollees, plans with more sociodemographically disadvantaged enrollees have lower performance scores, 22 , 23 leading to a lower likelihood of qualifying for bonus payments.

Importantly, we found evidence that racial and ethnic disparities in enrollment by star rating were driven by differential access to high‐rated plans. Previous research showed that star ratings were less strongly associated with enrollment for racial and ethnic minority enrollees than White enrollees, especially for Black enrollees. 4 Some interpreted this finding to mean that Black enrollees had lower awareness or willingness to pay for high‐rated plans than White enrollees. 24 However, our findings suggest this interpretation could be misleading as it does not account for differential access to high‐rated plans by race and ethnicity. We found that, after controlling for county‐level plan offerings, racial and ethnic disparities in enrollment largely decreased. This was especially pronounced for Black enrollees. In counties with a 5‐star plan, Black enrollees had higher enrollment in 5‐star plans than White enrollees, suggesting that low enrollment in 5‐star plans among Black enrollees overall may reflect supply constraints. However, we found relatively low enrollment in 4–4.5 star plans among Black enrollees, worthy of further study. Also, there was a distinct pattern of enrollment in 5‐star plans among Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic enrollees. As we did not examine the underlying mechanisms in which the racial and ethnic differences in enrollment in 5‐star plans reversed or increased after accounting for county‐level plan availability, this needs to be explored in further research.

Our prior research found substantially higher rates of hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC) among Black enrollees compared to White enrollees in both traditional Medicare (TM) and MA. However, these racial differences were greater in MA than TM (59.0 vs. 45.6 ACSC hospitalizations per 10,000 enrollees). 25 As ACSC hospitalization could be potentially preventable with timely access to appropriate primary care, 26 a potential mechanism for these disparities may be that Black enrollees have limited access to high‐quality primary care relative to White enrollees. Our current findings confirm that racial and ethnic minority enrollees in MA plans had fewer high‐rated plans and/or more low‐rated plans available in their counties of residence than White enrollees in MA plans. Because lower enrollment in high‐rated MA plans by race and ethnic minorities may lead to racial and ethnic disparities in access to high‐quality primary care, this might increase racial and ethnic disparities in ACSC hospitalizations. Thus, further research is warranted to investigate whether differences in enrollment by race and ethnicity in MA plans with high‐star ratings are associated with differences in ACSC hospitalizations.

Our findings of structural barriers to high‐quality MA plans for racial and ethnic minorities have important policy implications, suggesting that policy should target increasing high‐quality plan availability in geographic areas that serve racial and ethnic minorities. Indeed, we found that there were no 5‐star plans in the South where health disparities in care and outcomes are generally the most pronounced. This indicates that there may be differential effects in other regions of the country. Thus, risk adjustment that includes social risk could help level the playing field and encourage more plan offerings. Because the current MA star‐ratings system does not adjust for social risk, it limits incentives to enroll more racial and ethnic minorities. Research has shown that a similar star‐ratings system for nursing homes that does not account for social risk factors in estimating performance leads to gaming the system by excluding racial and ethnic minority groups and results in increased disparities in quality. 27 Indeed, accounting for socioeconomic status in plan performance increased rankings for MA plans with higher proportions of sociodemographically disadvantaged enrollees. 12

Policies could also address social risk factors in communities with more racial and ethnic minorities, which could incentivize high‐quality plans to operate in these communities. Evidence suggests that health care is necessary but not sufficient to improve population health. 28 , 29 , 30 Nearly 90% of the variation in health outcomes is attributable to social, behavioral, and economic factors. 31 Since 2018, CMS has allowed MA plans to provide supplemental non‐medical benefits to address enrollees' social determinants of health. Financial support to MA plans operating in counties with more racial ethnic minorities for these supplemental benefits could be conditional on plan quality and take the form of premium subsidies, rebates, and/or tax exemption, which would encourage greater high‐quality plan participation in communities that do not currently have sufficient access.

Furthermore, policymakers should consider other approaches to improving care for racial and ethnic enrollees in MA plans. For instance, providing assistance in plan choice and enrollee incentives to choose high‐quality plans is critical to increase enrollment in high‐quality plans. Evidence suggests that Medicare enrollees choose suboptimal coverage in terms of cost and quality, which may be attributable to limited health insurance literacy. 32 Providing subsidies for enrollment in high‐quality plans could increase enrollment in these plans.

Our study had several limitations. First, we could not account for all potential factors that might affect racial and ethnic disparities in enrollment. Our measure of health status is based on inpatient data only, possibly raising some concerns about imperfect adjustment. Also, we could not include individual‐level social risk factors. Second, star ratings may be a limited measure of quality of care. The star‐ratings system uses a subset of measures, and thus plans may concentrate on improvement for those particular measures. Also, star ratings are determined at the contract level and apply to all plans within the same contract, leading to discrepancies in quality of care for some plans. Thus, it is needed to report quality performance at the plan level. Third, we excluded those who died, and thus this may systematically bias our sample to be healthier. If those who died were both racial and ethnic groups and enrolled in high‐rated plans, then there may be greater racial and ethnic disparities in enrollment in high‐rated plans. Fourth, there may be other factors affecting MA plans' decisions on county‐level offering such as each county's MA benchmark. However, we did not explicitly account for all relevant factors. Finally, our findings are associations and not causal. Thus, there may be selection bias and the magnitude of the bias may be more pronounced in high‐rated plans.

Our findings suggest that differential enrollment in high‐rated MA plans by race and ethnicities was partly explained by limited access to high‐rated plans, and not by individual characteristics or enrollment decisions. Policies aimed at improving access to high‐rated plans have the potential to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in enrollment by star ratings. Policymakers should consider ways to ensure that all Medicare beneficiaries have access to high‐rated MA plans.

Supporting information

Data S1 Supplementary information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Park S, Werner RM, Coe NB. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and enrollment in high‐quality Medicare Advantage plans. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(2):303‐313. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13977

Funding information This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging, the National Institutes of Health (R01AG057501; P30AG012836). This work was supported by the Ewha Womans University Research Grant of 2022.

[Correction added on 7 July 2022, after first online publication: A funder was added.]

REFERENCES

- 1. Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M, Trivedi AN. Growth in Medicare Advantage greatest among Black and Hispanic enrollees. Health Aff. 2021;40(6):945‐950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martino SC, Elliott MN, Dembosky JW, et al. Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Disparities in Health Care in Medicare Advantage. CMS Office of Minority Health; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meyers DJ, Belanger E, Joyce N, McHugh J, Rahman M, Mor V. Analysis of drivers of disenrollment and plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):524‐532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, Shrank WH. Association between Medicare Advantage plan star ratings and enrollment. JAMA. 2013;309(3):267‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McWilliams JM, Hsu J, Newhouse JP. New risk‐adjustment system was associated with reduced favorable selection in Medicare Advantage. Health Aff. 2012;31(12):2630‐2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newhouse JP, Price M, Huang J, McWilliams JM, Hsu J. Steps to reduce favorable risk selection in Medicare Advantage largely succeeded, boding well for health insurance exchanges. Health Aff. 2012;31(12):2618‐2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Newhouse JP, Price M, McWilliams JM, Hsu J, McGuire TG. How much favorable selection is left in Medicare Advantage? Am J Health Econ. 2015;1(1):1‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Virnig BA, Lurie N, Huang Z, Musgrave D, McBean AM, Dowd B. Racial variation in quality of care among Medicare+Choice enrollees. Health Aff. 2002;21(6):224‐230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elliott MN, Haviland AM, Orr N, Hambarsoomian K, Cleary PD. How do the experiences of Medicare beneficiary subgroups differ between managed care and original Medicare? Health Serv Res. 2011;46(4):1039‐1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Epstein AM. Racial disparities in the quality of care for enrollees in medicare managed care. JAMA. 2002;287(10):1288‐1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buntin MB, Ayanian JZ. Social risk factors and equity in Medicare payment. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(6):507‐510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Durfey SNM, Kind AJH, Gutman R, et al. Impact of risk adjustment for socioeconomic status on Medicare Advantage plan quality rankings. Health Aff. 2018;37(7):1065‐1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weinick R, Haviland A, Hambarsoomian K, Elliott MN. Does the racial/ethnic composition of Medicare Advantage plans reflect their areas of operation? Health Serv Res. 2014;49(2):526‐545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huckfeldt PJ, Escarce JJ, Rabideau B, Karaca‐Mandic P, Sood N. Less intense postacute care, better outcomes for enrollees in Medicare Advantage than those in fee‐for‐service. Health Aff. 2017;36(1):91‐100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Atherly A, Dowd BE, Feldman R. The effect of benefits, premiums, and health risk on health plan choice in the Medicare program. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):847‐864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jacobs PD, Buntin MB. Determinants of Medicare plan choices: are beneficiaries more influenced by premiums or benefits? Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(7):498‐504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eicheldinger C, Bonito A. More accurate racial and ethnic codes for Medicare administrative data. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29(3):27‐42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jarrin OF, Nyandege AN, Grafova IB, Dong X, Lin H. Validity of race and ethnicity codes in Medicare administrative data compared with gold‐standard self‐reported race collected during routine home health care visits. Med Care. 2020;58(1):e1‐e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson G, Figueroa JF, Zhou X, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Recent growth in Medicare Advantage enrollment associated with decreased fee‐for‐service spending in certain US counties. Health Aff. 2016;35(9):1707‐1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McWilliams JM, Afendulis CC, McGuire TG, Landon BE. Complex Medicare advantage choices may overwhelm seniors–especially those with impaired decision making. Health Aff. 2011;30(9):1786‐1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DuGoff EH, Boyd C, Anderson G. Complex patients and quality of care in Medicare Advantage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(2):395‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30‐day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765‐774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen LM, Epstein AM, Orav EJ, Filice CE, Samson LW, Joynt Maddox KE. Association of practice‐level social and medical risk with performance in the Medicare physician value‐based payment modifier program. JAMA. 2017;318(5):453‐461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, Conway PH, Shrank WH. The roles of cost and quality information in Medicare Advantage plan enrollment decisions: an observational study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):234‐241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park S, Fishman P, Coe NB. Racial disparities in avoidable hospitalizations in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Med Care. 2021;59(11):989‐996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305‐311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Konetzka RT, Grabowski DC, Perraillon MC, Werner RM. Nursing home 5‐star rating system exacerbates disparities in quality, by payer source. Health Aff. 2015;34(5):819‐827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable health communities—addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daniel H, Bornstein SS, Kane GC. Addressing social determinants to improve patient care and promote health equity: an American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(8):577‐578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Willink A, DuGoff EH. Integrating medical and nonmedical services ‐ the promise and pitfalls of the CHRONIC care act. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2153‐2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):129‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park S, Langellier BA, Meyers DJ. Association of health insurance literacy with enrollment in traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and plan characteristics within Medicare Advantage. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2146792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Supplementary information.