Abstract

β-lactams are the most prescribed class of antibiotics due to their potent, broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities. However, alarming rates of antimicrobial resistance now threaten the clinical relevance of these drugs, especially for the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales expressing metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs). Antimicrobial agents that specifically target these enzymes to restore the efficacy of last resort β-lactam drugs, that is, carbapenems, are therefore desperately needed. Herein, we present a cyclic zinc chelator covalently attached to a β-lactam scaffold (cephalosporin), that is, BP1. Observations from in vitro assays (with seven MBL expressing bacteria from different geographies) have indicated that BP1 restored the efficacy of meropenem to ≤ 0.5 mg/L, with sterilizing activity occurring from 8 h postinoculation. Furthermore, BP1 was nontoxic against human hepatocarcinoma cells (IC50 > 1000 mg/L) and exhibited a potency of (Kiapp) 24.8 and 97.4 μM against Verona integron-encoded MBL (VIM-2) and New Delhi metallo β-lactamase (NDM-1), respectively. There was no inhibition observed from BP1 with the human zinc-containing enzyme glyoxylase II up to 500 μM. Preliminary molecular docking of BP1 with NDM-1 and VIM-2 sheds light on BP1’s mode of action. In Klebsiella pneumoniae NDM infected mice, BP1 coadministered with meropenem was efficacious in reducing the bacterial load by >3 log10 units’ postinfection. The findings herein propose a favorable therapeutic combination strategy that restores the activity of the carbapenem antibiotic class and complements the few MBL inhibitors under development, with the ultimate goal of curbing antimicrobial resistance.

Keywords: β-Lactam-Metallo-β-Lactamase Inhibitor, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, human hepatocarcinoma cells, Verona integron-encoded MBL, New Delhi metallo β-lactamase, Klebsiella pneumoniae

The emergence of resistance to the β-lactam (BL) antibiotics, that is, the most important class and last resort antimicrobials, arises when bacteria produce β-lactamase enzymes that destroy the BL scaffold, thereby reducing drug activity.1 The World Health Organization has stated that the most concerning resistant bacteria are the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.2 For the past four decades, β-lactamase inhibitors have effectively neutralized the effects of this resistance.3 However, bacteria have evolved resistance mechanisms, such as the carbapenemases, with various modes of action; these are divided into two groups according to their active sites: (i) serine β-lactamases (Ambler classes A, C, and D) and (ii) metallo-β-lactamases (MBL, class B). Currently, our clinical arsenal lacks MBL inhibitors to fortify public health against resistant infections.3−7

Combating resistance to lactam antibiotics has been accomplished by coadministering the BL antibiotic with a suicide BL such as clavulanic acid, tazobactam, or sulbactam.4 However, these regimens are currently only effective for serine β-lactamases and still pose significant challenges for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria.2 Of recent concern are the MBLs; these enzymes rely on zinc ion chelation in the active site that facilitates hydrolysis of the BL drug.8 Unlike serine β-lactamases, MBLs are not inhibited by irreversible binding to sacrificial BLs.3 There is an urgent need for MBL inhibitors, which are now being labeled as an unattended global threat.6 The impact of COVID-19 has overwhelmed hospitals worldwide, providing cannon fodder for the issue at hand and creating an environment for the upsurge of antimicrobial resistance.9

The two main strategies that have emerged to combat resistance due to the bacterial production of novel lactamases are as follows: (1) the discovery of new BL antibiotics (more resistant to β-lactamase hydrolysis) and (2) the use of β-lactamase inhibitors. However, despite the success of strategy (2) in combating resistance to serine β-lactamases none of the six FDA-approved inhibitors (clavulanic acid, sulbactam, tazobactam [based on a BL warhead], avibactam, relebactam [based on the diazabicyclooctane series], and vaborbactam [boron based]) target the inhibition of MBLs.6,10 Newer BL inhibitors such as zidebactam (non-BL bicyclo-acyl hydrazide inhibitor administered with cefepime)11 and nacubactam (non-BL diazabicyclooctane inhibitor administered with meropenem)12 are antimicrobial agents that act as BL enhancers by offering a dual mode of action by which, they target penicillin-binding protein 2 in Gram negative bacteria and inhibit the produced β-lactamase.10

A promising method to selectively target the MBLs’ mode of action is via the use of metal ion chelators that remove the essential zinc ions from the active site of the MBL enzyme.5,13 Several scaffolds including N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridinylmethyl)-1,2-ethanediamine (TPEN)14 and analogues,15 thiosemicarbazone,16 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (DOTA) analogues,17,18 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (NOTA),18 2-picolinic acid, phosphonates19 rhodanine, thioenolates,20 magnalol,21 tris-picolylamines,22N-acylhydrazone,23 2,6-pyridine dicarboxylates (H2dpa’s),24 and 1,2,4-triazole-3-thione,25 have shown good activity against the New Delhi metallo β-lactamase (NDM-1) and the Verona integron-encoded MBL (VIM-2) expressing bacteria, partially restoring meropenem activity. In many cases, these chelators have been conjugated with dipeptides that mimic the bacterial cell wall sequence. Despite the ubiquity of metal chelators, off-target activity often accompanies potent chelators26 leading to unwanted physiological effects,26 as is also seen for chelators that possess eukaryotic cytotoxicity.19 In the context of β-lactamase inhibitors, compounds bearing bicyclic boronates, such as taniborbactam27 and xeruborbactam (QPX7728),28 display good activity to type B β-lactamases. These compounds are currently in phase III and phase I clinical trials; respectively. The design of the bicyclic boronate inhibitors was inspired by the X-ray image of TEM-1 SBL harbored in E. coli covalently modified by (1R)-1-acetamido-2-(3-carboxy-2-hydroxyphenyl)ethylboronic acid (PDB 1ERQ, 1.9 Å).29 Within the structure of TEM-1, hydrogen bond interactions between the phenol group in the modified ligand and the oxygen atom of the catalytic serine seemed to create a coordination site for the Zn2+ ion. This prompted Burns et al.,30 (Protez Pharmaceuticals) to develop the first class of bicyclic boronates that were able to inhibit both SBLs and MBLs in 2010. Venatorx Pharmaceuticals further developed this idea by modifying the side chain of the ligand to produce taniborbactam.31 Research at Qpex Biopharma Inc. investigated the effects of substitution on the aromatic core of the 3,4-dihydro 2H-benzo[e][1,2]oxaborinin-2-ol scaffold which led to the discovery of xeruborbactam (QPX7728), which displays ultrabroad-spectrum activity that includes inhibition of MBLs and OXA-type enzymes.32

An area gaining traction is the employment of BL conjugates as prodrugs and inhibitors, forming a relatively stable enzyme-hydrolyzed product complex to target the MBL.21,33,34 In this study, our novel approach was to covalently attach a well-binding metal/zinc chelator to a BL scaffold (cephalosporin) in order to improve selectivity and biodistribution of the chelator. This approach gives both compounds an equal chance to reach the bacterial cell wall-producing target enzymes, thereby providing a lethal duo of high specificity to eradicate the bacterial infection. Here, we report the synthesis and preclinical profiling of an MBL inhibitor (BP1) with promising in vitro and in vivo efficacy.

Results and Discussion

Our research group has previously demonstrated that metal chelating agents, like NOTA, DOTA, and DPA, are potent MBL inhibitors, acting on MBL-producing CREs.35,36 These compounds exhibited undetectable toxic effects at effective concentrations in vitro.35 However, the highly polar nature of the isolated chelators made detection in plasma impossible, and they are likely rapidly excreted through renal clearance. This prompted us to investigate the cyclic zinc chelator’s capacity to inhibit MBLs when attached to a BL moiety, which should improve the molecule’s overall pharmacological properties. BP137 was synthesized in five steps through a procedure adapted from Dutta et al.38

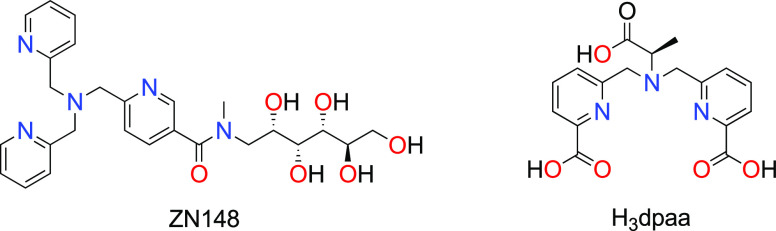

A desirable β-lactamase inhibitor should simultaneously neutralize MBLs, while preserving the activity of existing carbapenem antibiotics, thereby targeting antimicrobial resistance and restoring the efficacy of BLs. BP1 demonstrated the potential to achieve this, as observed in the in vitro experiments. According to Table 1 BP1 and NOTA each administered alone, do not possess any activity towards NDM harboring and susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae strains, while BP1 restores the efficacy of meropenem, thus indicating that BP1 and NOTA specifically target the MBLs and potentiate the activity of meropenem in carbapenemase-producing bacteria. The results were confirmed by the observed to be greater than eight-fold reduction in the MICs of the seven MBL-expressing bacteria (from different geographies) used for this study (Table 2). Importantly, meropenem can be administered at therapeutically acceptable concentrations, defined herein as a meropenem MIC of <2 mg/L coupled with a BP1 MIC of <64 mg/L. More importantly, our MIC breakpoints concur with the CLSI guidelines as well as the more stringent EUCAST recommendations. The pairing of BP1 with meropenem in combination therapy has the potential to be a favorable solution since both antimicrobials work synergistically to target the MBL and the pathogen (Table 2). Martin and co-workers34 also attached a chelator to a cephalosporin as a potential MBLI, however, their BL acts as a prodrug and upon hydrolysis releases a zinc binding thiol moiety to the enzyme active site. Their MIC data indicates that higher concentrations (≥32 mg/L) of their most potent compounds are required to resensitize the clinical isolates to meropenem, with the compounds having more activity towards bacteria expressing imipenemase (IMP) MBLs in comparison to VIM and NDM.33,34 It should be noted that BP1 is active against IMP, NDM, and VIM MBLs at lower concentrations. When comparing our results to other potential MBLI chelators that are based on nitrogen-bearing ligands, we came across the noteworthy contributions from Samuelsen et al.,22 where the MIC of meropenem reaches concentrations <2 mg/L with 50 μM of their most potent compound, which is ZN148, based on a tris-picolylamine ligand (Figure 1). In comparison, BP1 utilizes a lower MBLI concentration (32 mg/L or 29 μM), resulting in more efficacious meropenem MICs of <0.5 mg/L.

Table 1. Comparison of MICs for the Test Drug (BP1) against Meropenem and the Chelating Agent (NOTA), Alone or in Combination with Meropenema.

| MIC (mg/L) |

||

|---|---|---|

| drug or drug combination | Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 | Klebsiella pneumoniae NDM |

| meropenem (alone) | 0.03 | 128 |

| chelating agent (NOTA) | resistant from 256 to 0.125 | resistant from 256 to 0.125 |

| NOTA pre-complex to Zn | resistant from 256 to 0.125 | resistant from 256 to 0.125 |

| meropenem + NOTA | 0.03 + 0 | 0.25 + 16 |

| BP1 | resistant from 512 to 0.25 | resistant from 512 to 0.25 |

| meropenem + BP1 | 0.03 + 0 | 0.25 + 16 |

All experiments were conducted in triplicate. NOTA was derivatized by coupling it to a β-lactam to create BP1.

Table 2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of BP1 and Meropenem Across Seven MBL Harboring Bacteria Utilizing the Broth Microdilution Assaya.

| MIC (mg/L) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bacterial reference | bacterial strain | MBL produced | MEM alone | BP1 alone | BP1 + MEM | FICI |

| ATCC 25922 | E. coli | N/A | 0.06 | N/A | 0 + 0.06 | N/A |

| AUS 271 | E. coli | NDM-1 | 128 | >256 | 16 + 0.25 | 0.1 |

| FEK | E. coli | NDM-4 | 128 | >256 | 16 + 0.5 | 0.1 |

| JAP | E. coli | IMP-1 | 8 | >256 | 8 + 0.03 | 0 |

| TWA | E. coli | IMP-8 | 4 | >256 | 8 + 0.25 | 0.1 |

| IR 386 | E. cloacae | NDM-1 | 32 | >256 | 16 + 0.125 | 0.1 |

| KAR | E. cloacae | VIM-1 | 16 | >256 | 32 + 0.5 | 0.2 |

| USA 449 | K. pneumoniae | NDM | 128 | >256 | 16 + 0.5 | 0.1 |

MEM = meropenem. N/A = not applicable. Synergy, FICI < 0.5; additive 0.5–1; indifference, >0.5 FICI <4; and antagonism, FICI >4. All assays were conducted in triplicate. Compound (2), that is, the cephalosporin component of BP1, displayed no activity on its own. BP1 + meropenem and NOTA + meropenem did not show activity towards S. marcescens KPC-2 and E. coli OXA-28, indicating that BP1/NOTA has specific activity towards MBLs.

Figure 1.

Examples of recent nitrogen-bearing chelators as promising MBLIs.22,24

The most recent studies from another promising MBLI class of pentadentate-chelating N–O ligands, that is H2dpa derivatives24 (Figure 1), report similar activity as BP1. Although BP1 displays a broader spectrum of inhibition compared to the H2dpa derivatives, both compounds share a similar synergistic effect with meropenem according to the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) values of <0.13.

Serum had no considerable effect on the MIC of BP1 + meropenem combinations for the seven bacteria studied. To study the cytotoxicity of BP1, a cellular LDH assay was undertaken. LDH leakage is a marker of cellular membrane damage. Employing HepG2 cell lines, LDH was significantly reduced (***p < 0.0001) across the various evaluated BP1 concentrations (Figure S1). Therefore, BP1 did not induce cell necrosis after 24 h exposure and was deemed safe to administer with a low potential for toxicity.

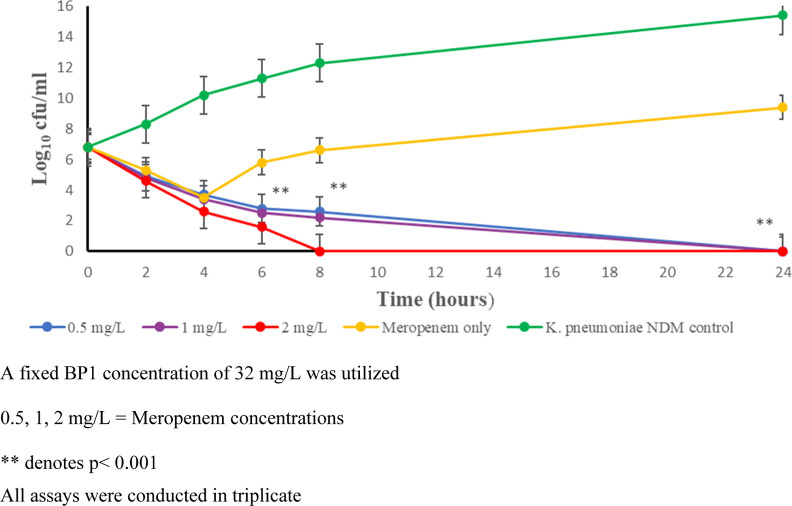

Time-kill kinetic studies (Figure 2) indicate that using 32 mg/L of BP1 in combination with varying meropenem doses of either 0.5, 1, or 2 mg/L resulted in complete bactericidal activity over 24 h. The concentration of 32 mg/L of BP1 was determined by studying the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of BP1 in combination with meropenem, which correlated to 2× the MIC. Our findings show a similar time-kill response as the H2dpa derivatives,24 however, their study employed a two-fold dilution decrease in meropenem and inhibitor concentrations. Furthermore, BP1 achieved complete killing, whereas the H2dpa derivatives reduced the bacterial load to 10 cfu/mL.

Figure 2.

Time-kill kinetic study of BP1 with meropenem at varying concentrations. K. pneumoniae NDM control (green circles) represents the bacterial growth curve unhindered by the addition of BP1 and meropenem. The meropenem-only test group (yellow circles) highlights the ineffectiveness of meropenem when administered without BP1. Sterilizing activity was achieved with BP1 at all concentrations of meropenem used by 24 h (blue, purple, and red circles).

Enzyme inhibition studies were performed to investigate the binding efficacy of BP1 in the NDM-1 and VIM-2 MBLs. BP1 was found to display good potency toward VIM-2 (Kiapp = 24.8 μM) and fair potency toward NDM-1 (Kiapp = 97.4 μM) (Figure S2 and Table S1). Enzyme inhibition activity of ZN148 was reported for NDM-1 (Ki = 310 μM) and VIM-2 (Ki = 24 μM).22 Zn chelators are expected to sequester one Zn atom from the active site and therefore act as slow-acting irreversible inhibitors that would require more detailed kinetic analyses than hitherto reported for such inhibitors.

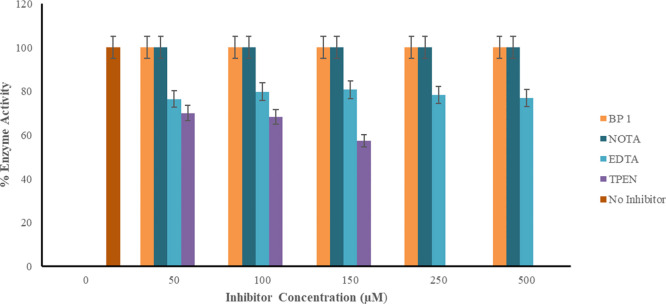

MBLs have been well known to possess active sites similar to the binding sites for mammalian enzymes that are essential for normal cellular functions. The human glyoxalase II (Glo2) enzyme shares a closely related protein fold and key zinc binding residues of MBLs.39 The inhibitory activity of BP1 against Glo2 (Figure 3) indicates that BP1 does not bind to zinc in this enzyme and is, by extension, less likely in other mammalian metalloproteins. This suggested that BP1 remained specific to binding to zinc within the MBLs at 50–500 μM, while zinc chelators, EDTA and TPEN, reduced the activity of the glyoxylase II by 39 and 48%, respectively (Table S2).

Figure 3.

Activity of human recombinant glyoxylase II in the presence of four inhibitors. All assays were conducted in triplicate. Normal glyoxylase II activity is denoted by the legend representing no inhibitor added. BP1 did not decrease the activity of glyoxylase II in comparison to the metal chelating agents EDTA and TPEN. NOTA a component of BP1, also did not reduce the activity of glyoxylase II.

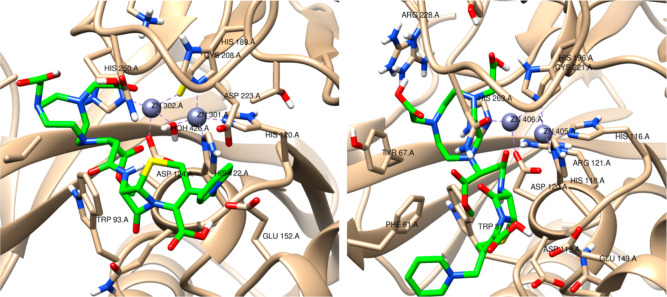

Next, we performed molecular docking of BP1 with NDM-1 and VIM-2, followed by a molecular dynamic simulation. The docked poses in NDM-1 and VIM-2 show that the chelator region of BP1 interacts with the Zn2+ ion via the carboxylic moiety (Figure 4). The NDM-1—BP1 had a docking score of −6.5 kcal/mol, while VIM-2—BP1 had −6.1 kcal/mol. It is likely that BP1 could ultimately remove the zinc ions from the active site, immobilizing the enzyme completely. This is supported by the absence of a MIC value when NOTA precomplexed to zinc was evaluated as a potential MBL inhibitor (Table 1), confirming that BP1’s zinc chelation is required for inhibition. Subsequent studies will use PACs–MD40 to determine if NOTA chelation of the zinc ion is energetically feasible.

Figure 4.

3D structures of NDM1—BP1 and VIM2—BP1 complexes, respectively. BP1 compounds are shown in green. In NDM1, the Zn301 (grey sphere) is coordinated to three histidines, and a water molecule (HOH426) coordinates the two zinc ions, while Zn302 is coordinated to histidine, aspartate, and cysteine residues. In VIM2, the Zn405 is coordinated to three histidines, and Zn06 is coordinated to one histidine, one aspartate, and one cysteine residue.

In order to prove that the NDM enzyme did not hydrolyze BP1, we incubated BP1 (up to 1000 μM) with the NDM enzyme and monitored the mass for 30 and 60 min without detecting any measurable change in intensity.

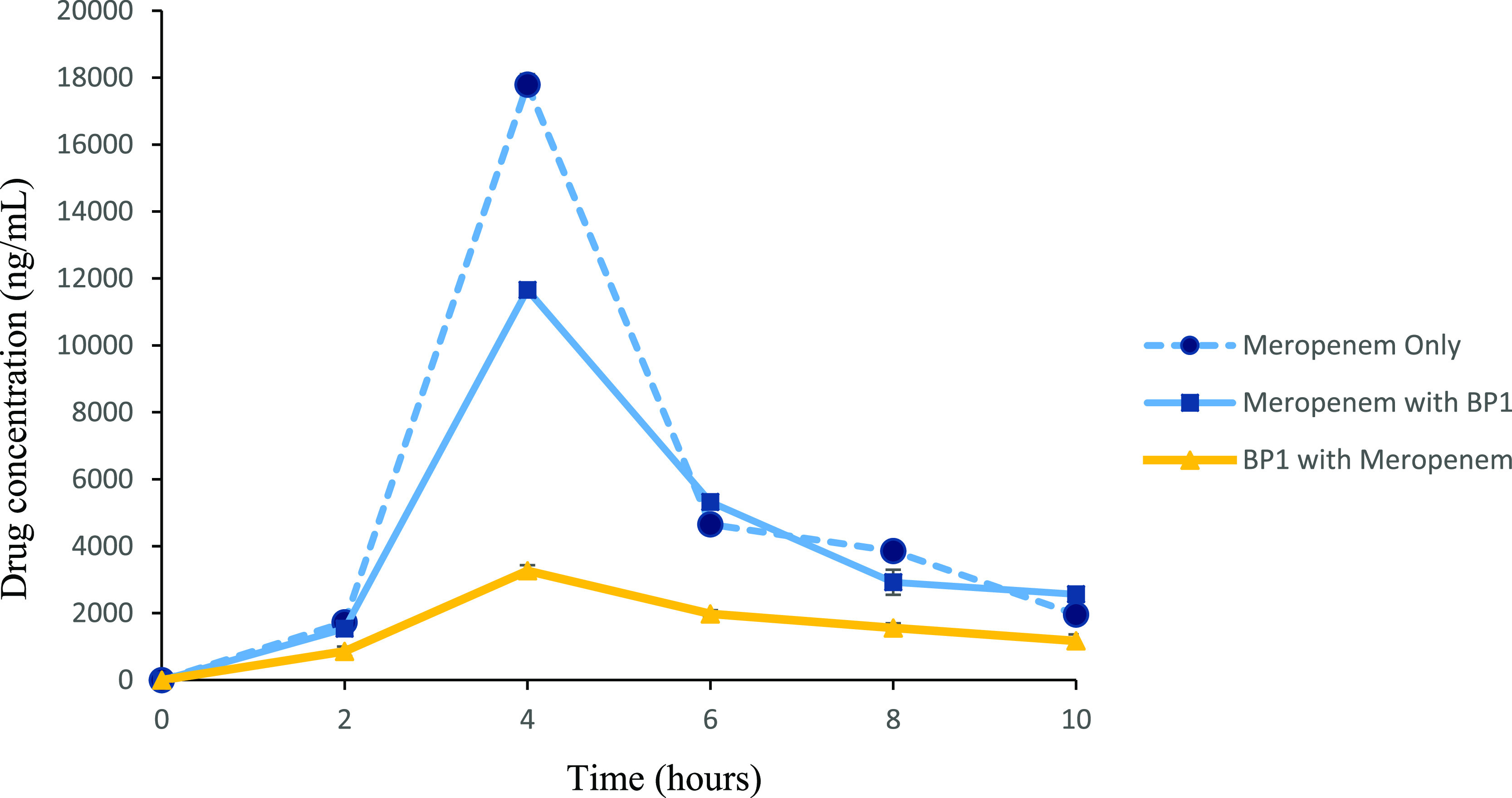

To further elucidate the potential of BP1, in vivo studies were conducted to investigate if the in vitro effect could be successfully replicated in an animal model. Prior to the in vivo efficacy study, we conducted a single dose pharmacokinetic experiment to determine the dose of BP1 required to reach safe therapeutic concentrations in plasma and, thus, an appropriate dosing schedule. We found that BP1 and meropenem shared a similar PK profile, reaching peak concentrations (Cmax) at 15 min post drug administration before reaching constant concentrations after 2 h (Figure S3). At a dose of 10 mg/kg.b.w, we achieved a plasma concentration of 1.93 μg/L, which was well below the cytotoxicity concentrations seen in the cell viability assays, advocating for the safe increase of the treatment dose to 100 mg/kg.b.w, which allowed us to reach therapeutic concentrations in plasma without the possibility of toxicity.

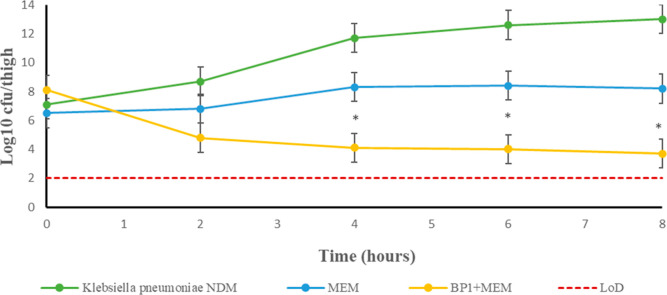

A murine thigh infection model was investigated to determine if combination therapy could reduce the bacterial burden. Prior to infection, animals were rendered neutropenic via the administration of cyclophosphamide, as discussed by Asempa et al.41 This allows for the evaluation of the efficacy of the proposed therapy removing the confounding effect of the innate immune response and also suggests that a larger dose was required to achieve a similar change in bacterial burden, and the inhibition of the immune system allowed for the establishment of an infection.41 The mice were successfully infected with Klebsiella pneumoniae NDM, as inflammation of the localized area was visible; this correlated with the cfu/thigh data expressed (Tables S3–S5). The mice were randomly grouped into three treatment regimens: S (saline only), M (meropenem only), and BP1 combination therapy (BP1 + meropenem). Since renal DHP-1 hydrolyzes meropenem at a rapid rate,42 dosing intervals with meropenem and BP1 were set 2 h apart to account for their short half-lives (as determined by single-dose pharmacokinetic studies) and promote the in vivo efficacy trial (Figure 5). The mice received four doses of both drugs (100 mg/kg each) over eight hours, with no observations of toxicity (total drug dose 800 mg/kg).

Figure 5.

Plasma BP1 and meropenem concentrations over the eight hour treatment period. BALB/c mice were infected i.m with K. pneumoniae NDM. Treatment was initiated 2 h post-infection with either S, M, or BP1. Four treatment doses were administered via IP. Data are presented as a mean ± SD (n = 6). Meropenem only—animals treated with meropenem only, meropenem (BP 1)—meropenem concentration when animals were treated with the combination of BP1 (meropenem)—BP1 concentration when animals were treated with the combination.

The outcome was successful, as shown by the significant reduction of >3 log10 units in the cfu/thigh count (Figure 6). These results show high statistical significance (Tables S3–S5), since the deviation among the data is <10%, while maintaining the effectiveness of combination therapy (p < 0.0018), as highlighted in Table 3. Upon closer inspection of Figure 6, one can note that the mice belonging to the combination therapy regimen were infected with a higher initial bacterial density than the S and M only treatment group. This could account for the reduction in the bacterial density not reaching a log10 cfu/mL count below 3.9. From our data, we can extrapolate that the bactericidal effect would continue up until 24 h postdosing; however, in terms of animal welfare, this is not ethically appropriate since the control animals will be at risk of severe inflammation and/or death. It is also impractical to repeatedly dose an experimental animal at 2 h intervals throughout a 24 h period. Nevertheless, the in vivo activity of BP1 is concordant with the in vivo efficacy reported for ZN148, where a decrease in the bacterial load is observed to a count of approximately 3 log10 units.22

Figure 6.

Efficacy of BP1 combination therapy over monotherapy in a murine thigh infection model. Neutropenic BALB/c mice were infected i.m with 0.1 mL of 106–108 cfu/mLof NDM producing K. pneumoniae. Four treatment doses, were administered via i.p over an 8 h period. The co-administration of BP1 and meropenem resulted in a significant decrease in K. pneumoniae NDM cfu/mL (yellow circles) in comparison to the S (green circles) and M (blue circles) treatments. This clearly indicates that BP1 + meropenem is a favorable treatment strategy.

Table 3. Evaluation of Statistical Parameters Measuring the Bactericidal Activity of BP1a.

| *time

kill assay |

in vivo efficacy study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| parameter | BP1 + 0.5 mg/L MEM | BP1 + 1 mg/L MEM | BP1 + 2 mg/L MEM | BP1 + MEM (100 mg/kg) |

| R2 | 0.6367 | 0.6451 | 0.6617 | 0.6509 |

| mean squares | 80.32 | 84.06 | 99.18 | 40.36 |

| F ratio | 13.14 | 13.63 | 14.67 | 11.19 |

| P value | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0018 |

*BP1 was administered as a fixed dose of 32 mg/L. MEM = meropenem. All assays were done in triplicate.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a BL-derived MBL inhibitor that can restore the MIC of meropenem in MBL expressing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. A preliminary evaluation found that BP1 is safe to administer at the utilized doses, with no signs of toxicity at therapeutic concentrations. The co-administration of BP1 with meropenem was highly efficacious in reducing the bacterial load to susceptible therapeutic concentrations. BP1’s bactericidal activity was evident, both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, the presence of human serum did not have a significant effect on the efficacy of this combination. A computational study supported the hypothesis that BP1 inhibits the MBL by binding to the Zn2+ ions. Taken together, our findings suggest that BP1 is a promising MBL inhibitor with potential for further development.

Methods

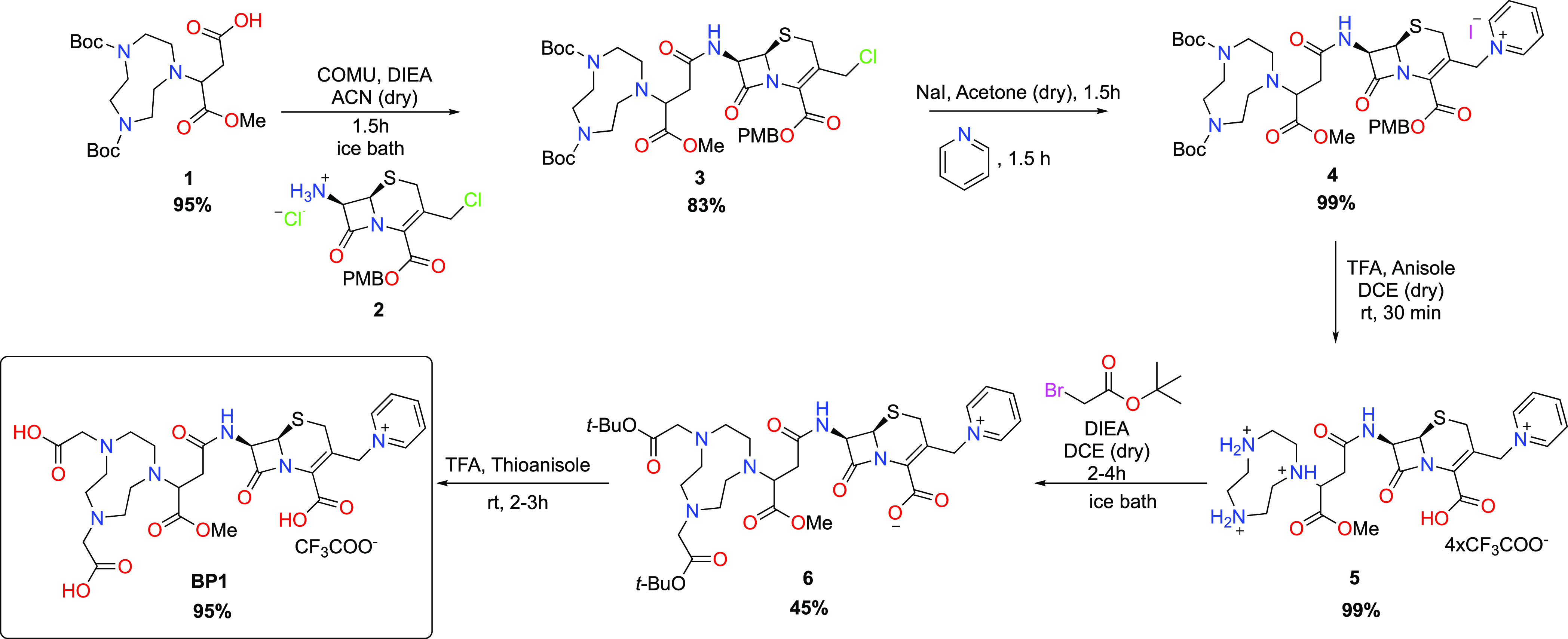

Synthesis of BP1

4-Methoxy-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-butanoic acid analogue (1) was coupled with a commercially available cephalosporin, 7-amino-3-chloromethyl-3-cephem-4-carboxylic acid p-methoxybenzyl ester hydrochloride (2), using the peptide coupling agent COMU in the presence of diisopropylethylamine to produce product (3) in 83% yield in its racemic form (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route of BP1.

The leaving group at the 3-position of the cephalosporin was then subjected to a pyridination to yield (4), which was isolated in 99% yield using supercritical fluid chromatography, followed by a Boc deprotection to furnish compound (5). Thereafter, the amines on the cyclononane were alkylated (6), and the protecting groups were subsequently removed using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to produce the deprotected final product (7 aka BP1) in 95% yield as an off-white solid. All reactions were monitored and optimized using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), and products were fully characterized using standard methods.

Bacterial Source

Well-characterized CRE strains producing MBLs or SBLs were acquired from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (U914), Paris, France.43K. pneumoniae NDM was obtained from Hartford Hospital, USA.44E. coli ATCC 25922 was employed as a carbapenem-susceptible control. All bacterial stock solutions were preserved in trypticase soy broth supplemented with 10% glycerol and contained 4 mm glass beads at −80 °C.

Antimicrobial Agents

Meropenem was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany), and BP1 was synthesized in our labs vide supra (see Supporting Information for experimental details). Meropenem was prepared in distilled water (m/v), and BP1 was prepared in 50% (m/v) DMSO. The final DMSO concentration was <1.0%. Antimicrobial stock solutions were stored at −80 °C.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

The drug susceptibility profile of meropenem, in combination with BP1, was conducted using the checkerboard assay. The assay was performed according to a previously described protocol45 and as per CLSI antimicrobial susceptibility guidelines.46 Briefly, two-fold dilutions of meropenem with BP1 were made in Mueller Hinton broth (MHB). A 0.5 McFarland-standardized bacterial inoculum was added to each well, generating a final volume of 100 μL, and plates were incubated at 35 °C for 18–20 h. The checkerboard assays were performed in triplicate. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration at which no visible growth was present. The FICI was calculated from the equation of FICI = FICa (MIC of drug A in combination/MIC of drug A alone) + FICb (MIC of drug B in combination/MIC of drug B alone).47 The FICI was categorized as follows: synergistic, FICI < 0.5; additive, 0.5 < FICI < 1; indifferent, > 0.5 FICI < 4; and antagonistic, FICI > 4.48

Effects of Human Serum

To study the effects of human serum on the MIC values, the above antimicrobial susceptibility testing protocol was adopted; however, the broth was prepared differently. MHB was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Oxoid Ltd, Thermo Fisher Scientific, United Kingdom). Thereafter, equal volumes of broth and 100% human serum were utilized to generate a medium that contained 50% human serum.

Time Kill Kinetic Study

Time kill studies were performed according to previously published methods,49 including those described in CLSI document M26-A.46 In summary, an overnight culture of K. pneumoniae NDM was diluted to approximately 106 cfu/mL. The prepared bacterial suspensions were added to wells containing a fixed dose of 32 mg/L BP1 and meropenem in concentrations of 0.5, 1, or 2 mg/L. Plates were incubated at 35 °C with 100 rpm shaking. A bacterial control without the addition of drugs and a meropenem-only control were included under similar conditions. Viability counts were performed at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h by sampling 0.1 mL and spreading onto Mueller Hinton agar (MHA). These plates were incubated at 35 °C for at least 18 h, followed by the enumeration of colony-forming units per milliliter (cfu/mL).

Cytotoxicity Assay

Cell Culture

Human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) cells were cultured in 25 mL cell culture flasks using Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% pen-strep-fungizone, and 1% l-glutamine and maintained in a humidified incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) until approximately 80% confluent.

Methyl Thiazol Tetrazolium Assay

The MTT assay was one of the methods used to determine the in vitro cell viability of BP1 in HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells (15,000 cells/well) were seeded into a 96-well microtiter plate and allowed to adhere overnight (37 °C, 5% CO2). Thereafter, the cells were incubated (37 °C, 5% CO2) with a range of BP1 concentrations (0, 1, 8, 10, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) in triplicate for 6 h. After the 6 h incubation, the cells were washed with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with MTT salt solution (5 mg/mL in 0.1 M PBS) and 100 μL CCM for 4 h (37 °C, 5% CO2). The MTT salt solution was removed, and DMSO (100 μL/well) was added and incubated for 1 h. The optical density was measured using a spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek μQuant) at 570/690 nm. Results are expressed as % cell viability versus BP1 concentration (μg/mL).

Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay

The LDH assay was used to assess membrane damage in HepG2 cells. The supernatant collected from the control and BP1-treated cells was centrifuged (400g, 24 °C, 10 min) and dispensed (100 μL/well) in triplicate into a 96-well microtiter plate. LDH reagent (100 μL, 11644793001, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well. The plate was incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Absorbance was read using a spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek μQuant) at 500 nm. Results are represented as a relative fold change compared to the untreated control.

Inhibition Assay

A dose-dependent enzyme inhibition assay was performed using a Biotek PowerWave XS2(Biotek Instruments, Inc, USA) plate reader. NDM-1 and VIM-2 enzymes were purchased from RayBiotech (RayBiotech Life Inc, USA). Enzymes in the quantity of 1 nM (NDM-1) or 4.5 nM (VIM-2) were used in this study with a fixed nitrocefin concentration of either 120 μM (NDM-1) or 50 μM (VIM-2) and varying BP1 concentrations ranging from 10 to 500 μM (NDM-1) and 1 to 400 μM (VIM-2) in 50 mM HEPES buffer supplemented with 100 μg/mL BSA and 10 μM ZnCl2. Inhibition was measured at 482 nm at 25 °C. All assays were conducted in triplicate. Refer to the accompanying Supporting Information (Figure S2) for further details.

Binding Specificity

To determine the binding specificity of the inhibitors to other zinc containing enzymes, glyoxylase (BioVision Inc, USA) was utilized to measure the level of specificity exhibited by BP1. The methodology has been previously described,22 with minor modifications in utilizing a temperature of 37 °C, measuring the absorbance at 520 nm, and the inclusion of positive controls: EDTA and TPEN (purchased from Merck KGaA, Germany).

Computational Studies

Computational methods are detailed in the Supporting Information (pages S7–S9)

Ethical Statement

All animal experiments carried out in this study were approved by the institutional Animal Research Ethics Committee at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, with approval reference AREC/013/016D (for the pharmacokinetic study) and AREC/00002618/2021 (for the in vivo efficacy study). All sample sizes used in this study were estimated using G*Power version 3.1.9.4.

In Vivo Single-Dose Pharmacokinetics

Female Bragg inbred albino c-strain (BALB/c) (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from the Biomedical Resource Unit (BRU). The animals were collected two weeks prior to the experimental procedures to allow for acclimatization. The animals were housed in well-ventilated cages, located in temperature- and humidity-controlled housing units, with a 12 h/12 h light–dark cycle. Environmental enrichment, in the form of shredded paper and plastic tunnels, were added to the cage. The animals were provided with commercially pelleted feed and clean water ad libitum. Experimental animals received a combination of meropenem (10 mg/kg.b.w) and BP1 (10 mg/kg.b.w) via intraperitoneal (IP) administration. Animals were then sacrificed periodically at 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min post-dosing (=3) to determine the pharmacokinetics of meropenem and BP1. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

In Vivo Efficacy

A murine thigh infection model described by Michail et al.50 was established with minor modifications. Male BALB/c mice weighing 18–22 g (n = 90) were used, and these animals were randomly assigned to treatment groups using simple randomization. Each of the three groups constituted of n = 30 mice, with n = 6 mice receiving treatment every 2 h. Prior to infection, mice were treated IP with 150 mg/kg cyclophosphamide on day one and 100 mg/kg on day four of the trial. This was done to induce neutropenia in the mice; neutropenia was confirmed by a neutrophil count of <100/mm3. On day five of the trial, animals received a 0.1 mL inoculum containing 106–108 cfu/mL of K. pneumoniae NDM intramuscularly (i.m) into the right thigh of the mice. Meropenem monotherapy (M), BP1 + meropenem (BP1) combination therapy, or normal saline (S) was administered every 2 h over an eight-hour treatment period. Mice were euthanized, by isoflurane overdose, at 2, 4, 6, and 8 h post-dosing. Our initial preclinical pK study showed that the drug concentration was sufficiently reduced after a 2 h period to allow for subsequent dosing without the risk of cytotoxicity. The right thigh muscle was then aseptically removed and homogenized in 5 mL of PBS. Homogenates were spread onto Mueller–Hinton agar and MacConkey agar plates, followed by incubation at 35 °C for 24 h and enumeration of the cfu/thigh. (Since BP1 did not have activity towards MBL resistance on its own, we did not study the standalone effect of BP1 in vivo, as it is not ethical to study the effect of a drug alone when it does not provide acceptable MICs. Our animal studies were done in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines and aimed to reduce the animal numbers utilized in this study.)

LC–MS Quantification

A Shimadzu Nexera Series (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) liquid chromatography system coupled with a Shimadzu LCMS-8050 tandem mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a Shim-Pack Velox SP-C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm particle size) with a gradient mobile phase comprised of Millipore water (0.1% v/v TFA) (A) and acetonitrile (0.1% v/v TFA) (B). The gradient method started from 5.0 to 95.0% B in 3 min and then held at 50% for 7 min thereafter, and it was brought back to 5% at 7.1 min. The column equilibration time was 2.9 min with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min, and the column oven temperature was 40 °C. The injection volume was 15 μL, and the total run time of the method was 10 min. Quantitative and qualitative studies were conducted by using the MRM mode via an ESI interface with the following source parameters: nitrogen nebulizer gas flow of 3 L/min, heat gas 10 L/min, and interface temperature of 300 °C. The precursor and product ions optimized were m/z: 325.2 → 80.15 for BP1, m/z: 384.50 → 68.25 for meropenem, and m/z: 350.50 → 304.40 for ampicillin (IS). Results were analyzed using the LabSolutions Insight LCMS. All data are expressed as a mean ± SD.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Linear and nonlinear regression models were used to determine parameters from the enzyme inhibition and fluorescence quenching assays. A one- and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the bactericidal effect expressed in the time kill and in vivo efficacy studies. In the time kill assay, each experimental BP1 and meropenem dose, was assessed against meropenem monotherapy and the bacterial control. However, for the in vivo efficacy study, the three treatment groups, namely, S (saline only), M (meropenem only), and BP1 combination therapy (BP1 + meropenem), were compared. Statistical significance was represented by a decrease in the p value (p < 0.05) and an increase in the F ratio.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Profs Patrice Nordmann and David P. Nicolau for the CRE and NDM strains, respectively. Drs E. Padayachee and S. B. Maseko are thanked for their guidance on the enzyme kinetic assays. A. Gouws is thanked for his assistance with the graphical abstract.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00485.

Synthesis, assay preparation, computations, and in vivo dosing schedule of BP1; cytotoxicity; potency; binding specificity; in vivo pharmacokinetics; in vivo efficacy; computational analyses; spectra of BP1 have been included; and summary of results, explanations, and in vivo dosing schedules (PDF)

Author Contributions

○ B.K.P. and N.R. are contributed equally.

The South African National Research Foundation (grant nos. 120419, 137979, 145774, 105236, 105216, and 105303), the Technology Innovation Agency of South Africa (UKZN_17-18_1), and the University of KwaZulu-Natal, College of Health Sciences.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Walsh T. R.; Toleman M. A.; Poirel L.; Nordmann P. Metallo-β-lactamases: the quiet before the storm?. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 306–325. 10.1128/cmr.18.2.306-325.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti M.; Garau J. Current and future perspectives in the treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, iv23–iv37. 10.1093/jac/dkab352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drawz S. M.; Bonomo R. A. Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 160–201. 10.1128/cmr.00037-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X.; Kim H. S.; Baugh K.; Huang Y.; Kadiyala N.; Wences M.; Singh N.; Wenzler E.; Bulman Z. P. Therapeutic options for metallo-β-lactamase-producing enterobacterales. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 125. 10.2147/idr.s246174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy N.; Shungube M.; Arvidsson P. I.; Baijnath S.; Kruger H. G.; Govender T.; Naicker T. A. A 2018-2019 patent review of metallo beta-lactamase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020, 30, 541–555. 10.1080/13543776.2020.1767070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica M. F.; Rossi M.-A.; Vila A. J.; Bonomo R. A. The urgent need for metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors: an unattended global threat. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e28–e34. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30868-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. S.; Gigante V.; Sati H.; Paulin S.; Al-Sulaiman L.; Rex J. H.; Fernandes P.; Arias C. A.; Paul M.; Thwaites G. E. Analysis of the clinical pipeline of treatments for drug resistant bacterial infections: despite progress, more action is needed. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e01991-21 10.1128/aac.01991-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani K. H.; Martin N. I. β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations: an update. Medchemcomm 2018, 9, 1439–1456. 10.1039/c8md00342d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariyawasam R. M.; Julien D. A.; Jelinski D. C.; Larose S. L.; Rennert-May E.; Conly J. M.; Dingle T. C.; Chen J. Z.; Tyrrell G. J.; Ronksley P. E.; Barkema H. W. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (November 2019–June 2021). Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 45. 10.1186/s13756-022-01085-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a Rawson T. M.; Ming D.; Ahmad R.; Moore L. S. P.; Holmes A. H. Antimicrobial use, drug-resistant infections and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 409–410. 10.1038/s41579-020-0395-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ruiz J. Enhanced antibiotic resistance as a collateral COVID-19 pandemic effect?. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 107, 114–115. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcione D.; Siracusa C.; Sulejmani A.; Leoni V.; Intra J. Old and new beta-lactamase inhibitors: Molecular structure, mechanism of action, and clinical Use. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 995. 10.3390/antibiotics10080995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlowsky J. A.; Hackel M. A.; Bouchillon S. K.; Sahm D. F. In vitro activity of WCK 5222 (Cefepime-zidebactam) against worldwide collected Gram-negative bacilli not susceptible to carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01432-20 10.1128/AAC.01432-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallalieu N. L.; Winter E.; Fettner S.; Patel K.; Zwanziger E.; Attley G.; Rodriguez I.; Kano A.; Salama S. M.; Bentley D.; Geretti A. M. Safety and pharmacokinetic characterization of nacubactam, a novel β-lactamase inhibitor, alone and in combination with meropenem, in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02229-19 10.1128/AAC.02229-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade N.; Tehrani K. H.; Brüchle N. C.; Haren M. J.; Mashayekhi V.; Martin N. I. Mechanistic investigations of metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors: strong zinc binding Is not required for potent enzyme inhibition. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1651–1659. 10.1002/cmdc.202100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S.; Zou Y.; Zhan M.; Guo Q.; Zhang Y.; Zhang Z.; Li B.; Zhang S.; Chu H. Zinc Chelator N, N, N′, N′-Tetrakis (2-Pyridylmethyl) Ethylenediamine Reduces the Resistance of Mycobacterium abscessus to Imipenem. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 2883. 10.2147/idr.s267552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoum R.; Rubinstein A.; Dembitsky V. M.; Srebnik M. Boron containing compounds as protease inhibitors. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4156–4220. 10.1021/cr608202m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a Prandina A.; Radix S.; Le Borgne M.; Jordheim L. P.; Bousfiha Z.; Fröhlich C.; Leiros H.-K. S.; Samuelsen Ø.; Frøvold E.; Rongved P. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new dipicolylamine zinc chelators as metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 1525–1540. 10.1016/j.tet.2019.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pape V. F.; Tóth S.; Füredi A.; Szebényi K.; Lovrics A.; Szabó P.; Wiese M.; Szakács G. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of thiosemicarbazones, hydrazinobenzothiazoles and arylhydrazones as anticancer agents with a potential to overcome multidrug resistance. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 117, 335–354. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a Summers K. L. A structural chemistry perspective on the antimalarial properties of thiosemicarbazone metal complexes. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 569–590. 10.2174/1389557518666181015152657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Kao R. Y. T.; Wang R.; Lai T. P.; Zhang H.; Li H.. Bismuth (III) Compounds and Methods Thereof. U.S. Patent. 20,180,085,335 A1, 2018.

- Somboro A. M.; Amoako D. G.; Osei Sekyere J.; Kumalo H. M.; Khan R.; Bester L. A.; Essack S. Y. 1,4,7-Triazacyclononane restores the activity of β-lactam antibiotics against metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: exploration of potential metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e02077-18 10.1128/aem.02077-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliffe P.; Tanner C. A.; Krismanich A. P.; Labbé G.; Goodfellow V. J.; Marrone L.; Desoky A. Y.; Calvopiña K.; Whittle E. E.; Zeng F.; Avison M. B.; Bols N. C.; Siemann S.; Spencer J.; Dmitrienko G. I. Structural and kinetic studies of the potent inhibition of metallo-β-lactamases by 6-phosphonomethylpyridine-2-carboxylates. Biochem 2018, 57, 1880–1892. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y.; Chen C.; Wang W.-M.; Xu L.-W.; Yang K.-W.; Oelschlaeger P.; He Y. Rhodanine as a potent scaffold for the development of broad-spectrum metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 359–364. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.; Yang H.; Yu T.; Chen F.; Liu R.; Xue S.; Zhang S.; Mao W.; Ji C.; Wang H.; Xie H. Stereochemically altered cephalosporins as potent inhibitors of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 232, 114174. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsen Ø.; Åstrand O. A. H.; Fröhlich C.; Heikal A.; Skagseth S.; Carlsen T. J. O.; Leiros H.-K. S.; Bayer A.; Schnaars C.; Kildahl-Andersen G. ZN148 is a modular synthetic metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor that reverses carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative pathogens in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02415-19 10.1128/aac.02415-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Li J.-Q.; Kang P.-W.; Chigan J.-Z.; Wang H.; Liu L.; Xu Y.-S.; Zhai L.; Yang K.-W. N-acylhydrazones confer inhibitory efficacy against New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 114, 105138. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.; Bai M.; Liu W.; Kong H.; Zhang T.; Yao H.; Zhang E.; Du J.; Qin S. H2dpa derivatives containing pentadentate ligands: An acyclic adjuvant potentiates meropenem activity in vitro and in vivo against metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 224, 113702. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legru A.; Verdirosa F.; Hernandez J.-F.; Tassone G.; Sannio F.; Benvenuti M.; Conde P.-A.; Bossis G.; Thomas C. A.; Crowder M. W.; Dillenberger M.; Becker K.; Pozzi C.; Mangani S.; Docquier J.-D.; Gavara L. 1, 2, 4-Triazole-3-thione compounds with a 4-ethyl alkyl/aryl sulfide substituent are broad-spectrum metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors with re-sensitization activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 226, 113873. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. A.; Cheng Z.; Yang K.; Hellwarth E.; Yurkiewicz C. J.; Baxter F. M.; Fullington S. A.; Klinsky S. A.; Otto J. L.; Chen A. Y.; Cohen S. M.; Crowder M. W. Probing the mechanisms of inhibition for various inhibitors of metallo-β-lactamases VIM-2 and NDM-1. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 210, 111123. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2020.111123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Trout R. E. L.; Chu G.-H.; McGarry D.; Jackson R. W.; Hamrick J. C.; Daigle D. M.; Cusick S. M.; Pozzi C.; De Luca F. Discovery of taniborbactam (VNRX-5133): a broad-spectrum serine-and metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor for carbapenem-resistant bacterial infections. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 2789. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker S. J.; Reddy K. R.; Lomovskaya O.; Griffith D. C.; Rubio-Aparicio D.; Nelson K.; Tsivkovski R.; Sun D.; Sabet M.; Tarazi Z.; Parkinson J.; Totrov M.; Boyer S. H.; Glinka T. W.; Pemberton O. A.; Chen Y.; Dudley M. N. Discovery of cyclic boronic acid QPX7728, an ultrabroad-spectrum inhibitor of serine and metallo-β-lactamases. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 7491–7507. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness S.; Martin R.; Kindler A. M.; Paetzel M.; Gold M.; Jensen S. E.; Jones J. B.; Strynadka N. C. Structure-Based Design Guides the Improved Efficacy of Deacylation Transition State Analogue Inhibitors of TEM-1 β-Lactamase,. Biochem 2000, 39, 5312–5321. 10.1021/bi992505b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns C. J., Goswami R., Jackson R. W., Lessen T., Li W., Pevear D. C., Tirunahari P. K., Xu H.. Beta-lactamase inhibitors. WO 2010130708 A1, 2010.

- Lence E.; González-Bello C. Bicyclic Boronate β-Lactamase Inhibitors: The Present Hope against Deadly Bacterial Pathogens. Adv. Ther. 2021, 4, 2000246. 10.1002/adtp.202000246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lomovskaya O.; Nelson K.; Rubio-Aparicio D.; Tsivkovski R.; Sun D.; Dudley M. N. Impact of intrinsic resistance mechanisms on potency of QPX7728, a new ultrabroad-spectrum beta-lactamase inhibitor of serine and metallo-beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother 2020, 64, e00552-20 10.1128/AAC.00552-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haren M. J.; Tehrani K. H.; Kotsogianni I.; Wade N.; Brüchle N. C.; Mashayekhi V.; Martin N. I. Cephalosporin Prodrug Inhibitors Overcome Metallo-β-Lactamase Driven Antibiotic Resistance. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 3806–3811. 10.1002/chem.202004694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani K. H.; Wade N.; Mashayekhi V.; Brüchle N. C.; Jespers W.; Voskuil K.; Pesce D.; van Haren M. J.; van Westen G. J.; Martin N. I. Novel Cephalosporin Conjugates Display Potent and Selective Inhibition of Imipenemase-Type Metallo-β-Lactamases. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 9141–9151. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somboro A. M.; Tiwari D.; Bester L. A.; Parboosing R.; Chonco L.; Kruger H. G.; Arvidsson P. I.; Govender T.; Naicker T.; Essack S. Y. NOTA: a potent metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1594–1596. 10.1093/jac/dku538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a Azumah R.; Dutta J.; Somboro A.; Ramtahal M.; Chonco L.; Parboosing R.; Bester L.; Kruger H.; Naicker T.; Essack S.; Govender T. In vitro evaluation of metal chelators as potential metallo- β -lactamase inhibitors. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 860–867. 10.1111/jam.13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omolabi K. F.; Reddy N.; Mdanda S.; Ntshangase S.; Singh S. D.; Kruger H. G.; Naicker T.; Govender T.; Bajinath S. The in vitro and in vivo potential of metal-chelating agents as metallo-beta-lactamase inhibitors against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2023, 370, fnac122. 10.1093/femsle/fnac12210.1093/femsle/fnac122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters B. K.; Kruger H. G.; Arvidsson P. I.; Naicker T.; Govender T.. Metallo-Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors; World Intellectual Property Organisation. PCT/IB2022/056748, 2023. Can be found on: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2023007325&_cid=P11-LDVGWL-84895-1

- Dutta J.; Chinthakindi P. K.; Arvidsson P. I.; Beatriz G.; Kruger H. G.; Govender T.; Naicker T.; Albericio F. A Facile synthesis of NODASA-functionalized peptide. Synlett 2016, 27, 1685–1688. 10.1055/s-0035-1561970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daiyasu H.; Osaka K.; Ishino Y.; Toh H. Expansion of the zinc metallo-hydrolase family of the β-lactamase fold. FEBS Lett. 2001, 503, 1–6. 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada R.; Kitao A. Parallel cascade selection molecular dynamics (PaCS-MD) to generate conformational transition pathway. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 035103. 10.1063/1.4813023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asempa T. E.; Abdelraouf K.; Nicolau D. P. Activity of β-lactam antibiotics against metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales in animal infection models: a current state of affairs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02271-20 10.1128/aac.02271-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett M.; Sprynski N.; Coelho A.; Castandet J.; Bayet M.; Bougnon J.; Lozano C.; Davies D. T.; Leiris S.; Zalacain M.; Morrissey I.; Magnet S.; Holden K.; Warn P.; De Luca F.; Docquier J. D.; Lemonnier M. Discovery of a Novel Metallo-β-Lactamase Inhibitor That Potentiates Meropenem Activity against Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00074-18 10.1128/AAC.00074-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann P.; Poirel L.; Dortet L. Rapid Detection of Carbapenemase-producingEnterobacteriaceae. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1503. 10.3201/eid1809.120355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacVane S. H.; Crandon J. L.; Nichols W. W.; Nicolau D. P. Unexpected In Vivo Activity of Ceftazidime Alone and in Combination with Avibactam against New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in a Murine Thigh Infection Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 7007–7009. 10.1128/aac.02662-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh M. H.; Yu M. Y.; Yu L. Y.; Chow J. W. Synergy assessed by checkerboard a critical analysis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1993, 16, 343–349. 10.1016/0732-8893(93)90087-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Approved Twenty-: Document M100-S28; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne PA, USA, 2018; Vol. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bardbari A. M.; Arabestani M. R.; Karami M.; Keramat F.; Aghazadeh H.; Alikhani M. Y.; Bagheri K. P. Highly synergistic activity of melittin with imipenem and colistin in biofilm inhibition against multidrug-resistant strong biofilm producer strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 443–454. 10.1007/s10096-018-3189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacometti A.; Cirioni O.; Kamysz W.; D’Amato G.; Silvestri C.; Del Prete M. S.; Łukasiak J.; Scalise G. Comparative activities of cecropin A, melittin, and cecropin A-melittin peptide CA(1-7)M(2-9)NH2 against multidrug-resistant nosocomial isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Peptides 2003, 24, 1315–1318. 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosibo S. C.; Somboro A. M.; Amoako D. G.; Osei Sekyere J.; Bester L. A.; Ngila J. C.; Sun D. D.; Kumalo H. M. Impact of Pyridyl Moieties on the Inhibitory Properties of Prominent Acyclic Metal Chelators Against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae: Investigating the Molecular Basis of Acyclic Metal Chelators’ Activity. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019, 25, 439–449. 10.1089/mdr.2018.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michail G.; Labrou M.; Pitiriga V.; Manousaka S.; Sakellaridis N.; Tsakris A.; Pournaras S. Activity of tigecycline in combination with colistin, meropenem, rifampin, or gentamicin against KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a murine thigh infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 6028–6033. 10.1128/aac.00891-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.