Abstract

Background

Depression and diabetes are major health challenges, with heavy economic social burden, and comorbid depression in diabetes could lead to a wide range of poor health outcomes. Although many descriptive studies have highlighted the prevalence of comorbid depression and its associated factors, the situation in Hunan, China, remains unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to identify the prevalence of comorbid depression and associated factors among hospitalized type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients in Hunan, China.

Methods

This cross-sectional study involved 496 patients with T2DM who were referred to the endocrinology inpatient department of Xiangya Hospital affiliated to Central South University, Hunan. Participants’ data on socio-demographic status, lifestyle factors, T2DM-related characteristics, and social support were collected. Depression was evaluated using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-depression subscale. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R software version 4.2.1.

Results

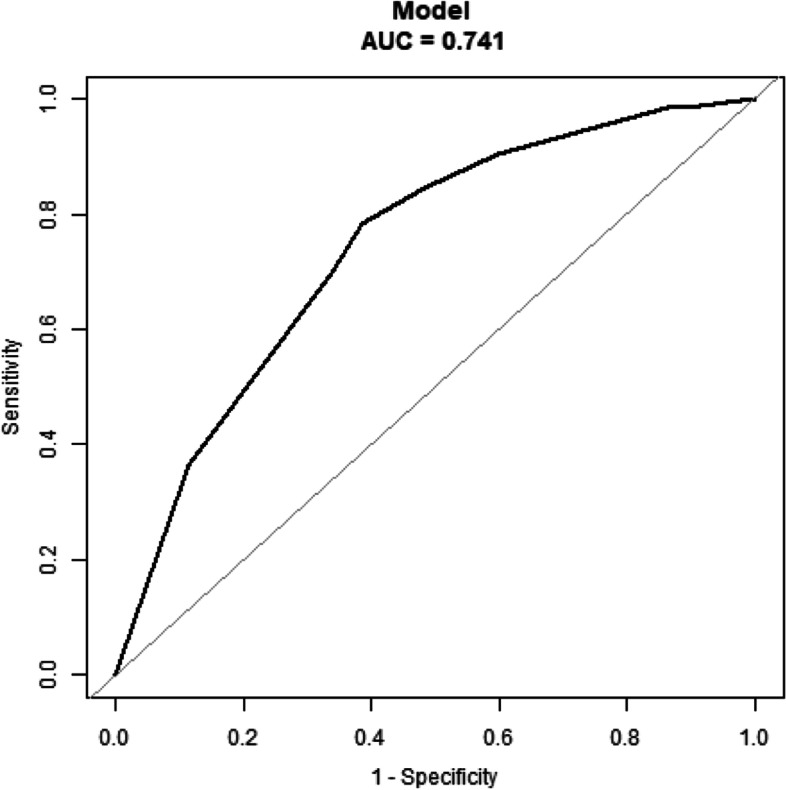

The prevalence of comorbid depression among hospitalized T2DM patients in Hunan was 27.22% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 23.3–31.1%). Individuals with depression differed significantly from those without depression in age, educational level, per capita monthly household income, current work status, current smoking status, current drinking status, regular physical activity, duration of diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, stroke, fatty liver, diabetic nephropathy, diabetic retinopathy, insulin use, HbA1c, and social support. A multivariable logistic regression model showed that insulin users (adjusted OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.02–3.42) had a higher risk of depression, while those with regular physical activity (adjusted OR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.30–0.77) or greater social support (adjusted OR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.11–0.34) had a lower risk of depression. The area under the curve of the receiver operator characteristic based on this model was 0.741 with a sensitivity of 0.785 and specificity of 0.615.

Conclusions

Depression was moderately prevalent among hospitalized T2DM patients in Hunan, China. Insulin treatment strategies, regular physical activity, and social support were significantly independently associated with depression, and the multivariable model based on these three factors demonstrated good predictivity, which could be applied in clinical practice.

Keywords: Depression, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Hospitalized patients, Associated factors, Hunan

Background

Diabetes is one of the fastest growing chronic diseases across the globe, causing microvascular and macrovascular complications and reduced life expectancy [1]. According to the latest data released by the International Diabetes Federation, the global prevalence of diabetes was 10.5% in 2021 and is expected to rise to 12.2% in 2045; the number of people affected by the disease is estimated to increase to 783.2 million in 2045 from 536.6 million in 2021 [2]. China was ranked first by the number of adults with diabetes in 2021 (140.9 million) and is expected to retain its position in 2045 (174.4 million) [2]. According to a nationally-representative cross-sectional study conducted by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the overall standardized prevalence estimation of diabetes increased significantly from 10.9% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 10.4–11.5%) in 2013 to 12.4% (95% CI: 11.8–13.0%) in 2018 [3]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) accounts for the majority of diabetes cases, with its prevalence increasing from 3.7% (95% CI: 3.6–3.8%) in 2008 to 6.6% (95% CI: 6.4–6.7%) in 2017, in Beijing. However, the annual rate of increase slowed from 18.1% (95% CI: 14.4–22.0%) to 1.5% (95% CI: 0.8–2.2%) before and after 2011, respectively [4].

Depression, characterized by persistent sadness and a lack of interest or pleasure in previously rewarding or enjoyable activities [5], is one of the most common mental disorders that coexist with T2DM patients [6–8]. Comorbid depression in T2DM patients significantly worsens prognosis and raises mortality rates by increasing the incidence of microvascular and macrovascular complications, as well as reducing treatment compliance and self-care ability. This could ultimately lead to impaired glycemic control and poor quality of life [9–11]. Additionally, compared with those with only diabetes, comorbid depression combined with diabetes could lead to higher healthcare costs and a greater socioeconomic burden [12, 13]. Therefore, understanding the prevalence of comorbid depression and associated factors among T2DM patients is critical not only for appropriate allocation of psychological intervention resources for healthcare providers but also for the facilitation of early identification of those with a heightened risk of depression.

Globally, numerous studies have addressed the issue of comorbid depression in T2DM patients. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of comorbid depression among T2DM patients was 28% globally, 24% in Europe, 27% in Africa, 29% in Australia, and 32% in Asia [14]. Liu et al. [15] found that the pooled prevalence of comorbid depression among T2DM patients in China was 25.9% (95% CI: 20.6–31.6%), with the figure being higher in females, participants aged ≥60 years, those with a primary school or lower education, individuals with a duration of T2DM ≥10 years, participants with diabetic complications, insulin users and participants living alone, and being lower in those with current alcohol use. However, no study has reported the prevalence of comorbid depression and associated factors among hospitalized patients with T2DM in Hunan, which is located in central China and middle reaches of the Yangtze River. The province covers an area of 211.8 thousand square kilometers, with a registered population of 73 million and a permanent population of 69.18 million in 2020. The present study aimed to identify the prevalence of comorbid depression and associated factors among hospitalized T2DM patients in Hunan, using a cross-sectional study design to comprehensively assess the role of socio-demographic status, lifestyle factors, T2DM-related characteristics, and social support in comorbid depression among T2DM patients.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Hunan, China. All individuals referred to the endocrinology inpatient department of Xiangya Hospital affiliated to Central South University—a top-level general hospital located in the capital city of Hunan Province (Changsha), China—between March and December 2021, with T2DM confirmed by the endocrinologist, and aged ≥40 years were consecutively invited to participate in this study. Those with dementia or who could not speak Mandarin were excluded. The sample size of this study was 496, which was more than the minimum sample required of 385 as determined based on the sample size formula for categorical outcome (proportion) in cross-sectional studies (N = Z2p(1-p)/d2) [16] using these assumptions: Z = 1.96, p = 20.6% (the lower limit of the 95% CI of the pooled prevalence of comorbid depression among T2DM patients in China reported by a previous meta-analysis) [15], and d = 0.2p.

Procedures

Data on socio-demographic status, lifestyle factors, social support, and depression were collected by investigators who underwent unified training and had at least a bachelor’s degree in medicine. Information such as body mass index (BMI), duration of diabetes, family history of diabetes, diabetic complications and comorbidities, and insulin treatment strategies was obtained from electronic medical records. HbA1c was measured as part of routine inpatient visits using an ARKRAY automatic glycohemoglobin analyzer (ARKRAY Factory, Shanghai, China) on the ADAMS A1c HA-8180 system.

Outcome of interest

The primary outcome of this study was the prevalence of comorbid depression. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-depression subscale (HADS-D) was used to evaluate depressive symptoms. The HADS-D, developed by Zigmond and Snaith, is a 7-item self-report scale with 4 response alternatives from 0 to 3 [17]. Its total score ranges between 0 and 21 with a score of ≥8 recommended as the cut off level for depression [18, 19]. Specifically, those with a total score of ≥8 were categorized into depression group, and those with a total score of < 8 were categorized into non-depression group. The HADS-D had satisfactory reliability and validity in the Chinese population. The concurrent validity of the HADS-D compared to the mental component summary of the Chinese version of Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short Form (C-SF-12) (version 2) was described between − 0.53 and − 0.51 [20], and the Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 0.81 to 0.87 [20–22]. In the current study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of HADS-D was 0.837.

Independent variables

The independent variables of this study were socio-demographic status (age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, household income, living status, and current work status), lifestyle factors (current smoking and drinking status, and regular physical activity), T2DM related characteristics (BMI, duration of diabetes, family history of diabetes, diabetic complications and comorbidities, HbA1c, and insulin treatment strategies), and social support.

Current smoking was defined as smoking greater than or equal to 1 cigarette in the past 30 days, current drinking was defined as having at least one drink of any alcoholic beverage in the past 30 days, and regular physical activity was defined as the performance of at least one activity, such as walking, square dancing, and cycling, for at least 30 minutes per day in the past 30 days. T2DM related characteristics were collected from the electronic medical records, and BMI was categorized into < 24 and ≥ 24 based on Chinese Guidelines for Medical Nutrition Treatment of Overweight/Obesity (2021 edition) [23]. The duration of diabetes was categorized into < 10 years and ≥ 10 years based on the findings of previous studies [24–26], and HbA1c was categorized into ≤7 and > 7% according to the Clinical Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in older adults in China (2022 edition) [27].

Social support was measured using the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) [28], which is a 10-item scale with three dimensions—subjective support (4 items), objective support (3 items), and support utilization (3 items). The total score ranges from 12 to 66, with higher scores suggesting greater social support. A total score of > 44 (≤44) was regarded as high (low) social support. The SSRS has been widely used and is well validated in Chinese populations [29, 30], and in the current study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of SSRS was 0.788.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables distributed normally or abnormally were described by mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were described by frequency (n) and proportion (%).

The difference between the depression and non-depression groups by each independent variable was examined using the chi-square test. The contribution of each independent variable to the outcome variable (depression) was quantified by crude OR and its corresponding 95% CI using univariable logistic regression analyses. Independent variables that differed significantly between the depression and non-depression groups were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model, from which the contribution of each independent variable was quantified by adjusted OR (aOR) and its corresponding 95% CI. Finally, the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve based on the multivariable logistic regression model was drawn to evaluate the predictive value of the model. All statistical analyses were two-sided at the 5% significant level and were conducted in the R software version 4.2.1 (https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

The mean age of the study population was 59.57 ± 9.92 with a range of 40 to 96. Among the 496 participants, 284 (57.26%) were men, 469 (94.56%) were Han Ethnicity, 447 (90.12%) were married, and 217 (43.75%) attended high school or above. Regarding lifestyle, 83 (16.73%) were current smokers, 56 (11.29%) were current drinkers, and 320 (64.52%) performed regular physical activity. The mean duration of diabetes was 11.21 ± 7.75 years, with the majority (54.84%) having duration of diabetes ≥10 years. Furthermore, 314 (63.31%), 138 (27.82%), 92 (18.55%), 165 (33.27%), 71 (14.32%), and 117 (23.60%) of the participants had hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, stroke, and fatty liver, respectively, whereas 262 (52.82%), 226 (45.57%), 49 (9.88%), 379 (76.41%), and 235 (47.38%) participants had diabetic nephropathy, diabetic retinopathy, diabetic foot, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and diabetic peripheral vascular disease, respectively. The mean total score of SSRS was 42.14 ± 7.55, and based on the cutoff value of 44, 289 (58.27%) and 207 (41.73%) were categorized as having low and high social support, respectively (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and lifestyle factors of the study participants (n = 496)

| Independent variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40–59 years | 271 | 54.63 |

| ≥60 years | 225 | 45.36 | |

| Sex | Male | 284 | 57.26 |

| Female | 212 | 42.74 | |

| Ethnicity | Han | 469 | 94.56 |

| Minority | 27 | 5.44 | |

| Marital status | Married | 447 | 90.12 |

| Unmarried | 49 | 9.88 | |

| Educational level | Middle school or below | 279 | 56.25 |

| High school or above | 217 | 43.75 | |

| Per capita monthly household income | ≤5000 yuan | 341 | 68.75 |

| > 5000 yuan | 155 | 31.25 | |

| Living alone | Yes | 30 | 6.05 |

| No | 466 | 93.95 | |

| Current work status | Employed | 145 | 29.23 |

| Not employed | 351 | 70.77 | |

| Current smoking status | No | 413 | 83.27 |

| Yes | 83 | 16.73 | |

| Current drinking status | No | 440 | 88.71 |

| Yes | 56 | 11.29 | |

| Regular physical activity | No | 176 | 35.48 |

| Yes | 320 | 64.52 |

Table 2.

T2DM-related characteristics of the study participants (n = 496)

| Independent variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | < 24 | 269 | 54.23 |

| ≥24 | 227 | 45.77 | |

| Duration of diabetes | < 10 years | 224 | 45.16 |

| ≥10 years | 272 | 54.84 | |

| Family history of diabetes | No | 271 | 54.64 |

| Yes | 225 | 45.36 | |

| Hypertension | No | 182 | 36.69 |

| Yes | 314 | 63.31 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | No | 358 | 72.18 |

| Yes | 138 | 27.82 | |

| Coronary heart disease | No | 404 | 81.45 |

| Yes | 92 | 18.55 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | No | 331 | 66.73 |

| Yes | 165 | 33.27 | |

| Stroke | No | 425 | 85.69 |

| Yes | 71 | 14.32 | |

| Fatty liver | No | 379 | 76.41 |

| Yes | 117 | 23.60 | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | No | 234 | 47.18 |

| Yes | 262 | 52.82 | |

| Diabetic retinopathy | No | 270 | 54.44 |

| Yes | 226 | 45.57 | |

| Diabetic foot | No | 447 | 90.12 |

| Yes | 49 | 9.88 | |

| Diabetic peripheral neuropathy | No | 117 | 23.59 |

| Yes | 379 | 76.41 | |

| Diabetic peripheral vascular disease | No | 261 | 52.62 |

| Yes | 235 | 47.38 | |

| Insulin use | No | 122 | 24.60 |

| Yes | 374 | 75.40 | |

| HbA1c | ≤7% | 113 | 22.78 |

| > 7% | 383 | 77.22 | |

| Social support | Low | 289 | 58.27 |

| High | 207 | 41.73 |

BMI, body mass index

Prevalence of comorbid depression

The median (IQR) of the total score of HADS-D was 5.00 (6.00), and according to the cutoff value of 8, 135 and 361 participants were categorized into depression group and non-depression group, respectively. The prevalence of comorbid depression among hospitalized T2DM patients in Hunan was 27.22% (95% CI: 23.3–31.1%).

Univariable analyses of factors associated with comorbid depression

Tables 3 and 4 show the results of univariable associations between the independent variables and comorbid depression. The depression and non-depression groups differed significantly in relation to age, educational level, per capita monthly household income, current work status, current smoking status, current drinking status, regular physical activity, duration of diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, stroke, fatty liver, diabetic nephropathy, diabetic retinopathy, insulin use, HbA1c, and social support (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Univariable analyses for the associations of socio-demographic and lifestyle factors with comorbid depression

| Independent variable | Category | Depression group (n = 135, %) | Non-depression group (n = 361, %) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40–59 years | 58 (42.96) | 213 (59.00) | 1 | 0.001** |

| ≥60 years | 77 (57.04) | 148 (41.00) | 1.91 (1.28–2.85) | ||

| Sex | Male | 68 (50.37) | 216 (59.83) | 1 | 0.058 |

| Female | 67 (49.63) | 145 (40.17) | 1.47 (0.99–2.18) | ||

| Ethnicity | Han | 130 (96.30) | 339 (93.91) | 1 | 0.296 |

| Minority | 5 (3.70) | 22 (6.09) | 0.59 (0.22–1.60) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 116 (85.9) | 331 (91.69) | 1 | 0.056 |

| Unmarried | 19 (14.07) | 30 (8.31) | 1.81 (0.98–3.33) | ||

| Educational level | Middle school or below | 96 (71.11) | 183 (50.69) | 1 | < 0.001*** |

| High school or above | 39 (28.89) | 178 (49.31) | 0.42 (0.27–0.64) | ||

| Per capita monthly household income | ≤5000 yuan | 114 (84.44) | 227 (62.88) | 1 | < 0.001*** |

| > 5000 yuan | 21 (15.56) | 134 (37.12) | 0.31 (0.19–0.52) | ||

| Living alone | Yes | 12 (8.89) | 18 (4.99) | 1 | 0.105 |

| No | 123 (91.11) | 343 (95.01) | 0.54 (0.25–1.25) | ||

| Current work status | Employed | 18 (13.33) | 127 (35.18) | 1 | < 0.001*** |

| Not employed | 117 (86.67) | 234 (64.82) | 3.53 (2.05–6.06) | ||

| Current smoking status | No | 120 (88.89) | 293 (81.16) | 1 | 0.040* |

| Yes | 15 (11.11) | 68 (18.84) | 0.54 (0.30–0.98) | ||

| Current drinking status | No | 126 (93.33) | 314 (86.98) | 1 | 0.047* |

| Yes | 9 (6.67) | 47 (13.02) | 0.48 (0.23–0.99) | ||

| Regular physical activity | No | 68 (50.37) | 108 (29.92) | 1 | < 0.001*** |

| Yes | 67 (49.63) | 253 (70.09) | 0.43 (0.23–0.63) |

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001

Table 4.

Univariable analyses for the association of T2DM related characteristics with comorbid depression

| Independent variable | Category | Depression group (n = 135, %) | Non-depression group (n = 361, %) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | < 24 | 74 (54.81) | 195 (54.02) | 1 | 0.874 |

| ≥24 | 61 (45.19) | 166 (45.98) | 0.97 (0.65–1.44) | ||

| Duration of diabetes | < 10 years | 50 (37.04) | 174 (48.20) | 1 | 0.002** |

| ≥10 years | 85 (62.96) | 187 (51.80) | 1.96 (1.27–3.04) | ||

| Family history of diabetes | No | 76 (56.30) | 195 (54.02) | 1 | 0.650 |

| Yes | 59 (43.70) | 166 (45.98) | 0.91 (0.61–1.36) | ||

| Hypertension | No | 100 (74.07) | 214 (59.28) | 1 | 0.002** |

| Yes | 35 (25.93) | 147 (40.72) | 1.96 (1.27–3.04) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | No | 34 (25.19) | 104 (28.81) | 1 | 0.423 |

| Yes | 101 (74.81) | 257 (71.19) | 0.83 (0.53–1.31) | ||

| Coronary heart disease | No | 32 (23.70) | 60 (16.62) | 1 | 0.071 |

| Yes | 103 (76.30) | 301 (83.38) | 1.56 (0.96–2.53) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | No | 59 (43.70) | 106 (29.36) | 1 | 0.003** |

| Yes | 76 (56.30) | 255 (70.64) | 1.87 (1.24–2.81) | ||

| Stroke | No | 29 (21.48) | 42 (11.63) | 1 | 0.005** |

| Yes | 106 (78.52) | 319 (88.37) | 2.08 (1.23–3.50) | ||

| Fatty liver | No | 22 (16.30) | 95 (26.32) | 1 | 0.019* |

| Yes | 113 (83.70) | 266 (73.68) | 0.55 (0.33–0.91) | ||

| Diabetic nephropathy | No | 90 (66.67) | 172 (47.65) | 1 | < 0.001*** |

| Yes | 45 (33.33) | 189 (52.35) | 2.20 (1.45–3.32) | ||

| Diabetic retinopathy | No | 77 (57.04) | 149 (41.27) | 1 | 0.002** |

| Yes | 58 (42.96) | 212 (58.73) | 1.89 (1.27–2.82) | ||

| Diabetic foot | No | 16 (11.85) | 33 (9.14) | 1 | 0.368 |

| Yes | 119 (88.15) | 328 (90.86) | 1.34 (0.71–2.52) | ||

| Diabetic peripheral neuropathy | No | 28 (20.74) | 89 (24.65) | 1 | 0.361 |

| Yes | 107 (79.26) | 272 (75.35) | 1.25 (0.71–2.52) | ||

| Diabetic peripheral vascular disease | No | 71 (52.59) | 190 (52.63) | 1 | 0.994 |

| Yes | 64 (47.41) | 171 (47.37) | 1.00 (0.67–1.49) | ||

| Insulin use | No | 21 (15.56) | 101 (27.98) | 1 | 0.004** |

| Yes | 114 (84.44) | 260 (72.02) | 2.11 (1.25–3.54) | ||

| HbA1c | ≤7% | 64 (47.41) | 131 (36.29) | 1 | 0.014* |

| > 7% | 71 (52.59) | 230 (63.71) | 0.24 (0.05–0.44) | ||

| Social support | Low | 114 (84.44) | 175 (48.48) | 1 | < 0.001*** |

| High | 21 (15.56) | 186 (51.52) | 0.17 (0.10–0.29) |

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; BMI, body mass index

Multivariable analyses of factors associated with comorbid depression

Table 5 shows the results of the multivariable logistic regression model on factors associated with comorbid depression among hospitalized T2DM patients in Hunan. Insulin users (aOR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.02–3.42, P = 0.044) were at an increased risk of comorbid depression. Those performing regular physical activity (aOR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.30–0.77, P = 0.002) or having higher social support (aOR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.11–0.34, P < 0.001) had a reduced risk of comorbid depression. The ROC curve based on the multivariable logistic regression model including the factors of insulin treatment strategies, regular physical activity, and social support is shown in Fig. 1. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.741 with a sensitivity of 0.785 and a specificity of 0.615.

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis on factors associated with comorbid depression

| Independent variable | Description | B | SE | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40–59 years Vs ≥60 years | −0.518 | 0.282 | 1.27 (0.74–2.18) | 0.379 |

| Educational level | Middle school or below Vs High school or above | −0.518 | 0.282 | 0.59 (0.34–1.03) | 0.064 |

| Per capita monthly household income | ≤5000 yuan Vs > 5000 yuan | −0.514 | 0.331 | 0.60 (0.31–1.14) | 0.120 |

| Current work status | Employed Vs Not employed | 0.498 | 0.345 | 1.63 (0.83–3.21) | 0.155 |

| Current smoking status | No Vs Yes | −0.501 | 0.384 | 0.61 (0.29–1.30) | 0.204 |

| Current drinking status | No Vs Yes | 0.268 | 0.49 | 1.31 (0.50–3.41) | 0.585 |

| Regular physical activity | No Vs Yes | −0.720 | 0.239 | 0.48 (0.30–0.77) | 0.002** |

| Duration of diabetes | < 10 years Vs ≥10 years | 0.089 | 0.156 | 1.24 (0.59–2.59) | 0.565 |

| Hypertension | No Vs Yes | 0.222 | 0.279 | 1.24 (0.72–2.15) | 0.437 |

| Chronic kidney disease | No Vs Yes | 0.287 | 0.31 | 1.33 (0.72–2.44) | 0.364 |

| Stroke | No Vs Yes | 0.570 | 0.319 | 1.75 (0.94–3.28) | 0.079 |

| Fatty liver | No Vs Yes | −0.246 | 0.311 | 0.79 (0.43–1.45) | 0.447 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | No Vs Yes | 0.108 | 0.316 | 1.11 (0.6–2.07) | 0.734 |

| Diabetic retinopathy | No Vs Yes | 0.426 | 0.255 | 1.54 (0.93–2.54) | 0.091 |

| Insulin use | No Vs Yes | 0.613 | 0.308 | 1.86 (1.02–3.42) | 0.044* |

| HbA1c | ≤7% Vs > 7% | −0.427 | 0.267 | 0.65 (0.38–1.10) | 0.108 |

| Social support | Low Vs High | −1.624 | 0.28 | 0.20 (0.11–0.34) | < 0.001*** |

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001

Fig. 1.

The ROC curve based on the multivariable logistic regression model

Discussion

Compared with healthy controls, T2DM patients had a two-fold risk of developing depression [6], with comorbid depression in T2DM potentially leading to a wide range of poor health outcomes [31–33]. The present study was aimed at identifying the prevalence of comorbid depression and associated factors among hospitalized T2DM patients in Hunan. Few studies have evaluated the prevalence of comorbid depression among hospitalized patients exclusively. These limited studies showed that the prevalence was 49.2% (70/142) in Pakistan [34], 33.1% (47/142) in Morocco [35], 53.8% (85/160) in Saudi Arabia [36], and 23.2% (50/216) in Vietnam [37]. The prevalence of comorbid depression among hospitalized T2DM patients in Hunan, found in the present study (27.22%, 135/496) was lower than that in Pakistan and Saudi Arabia and almost comparable with that in Vietnam and Morocco. The differences in the economic development level, cultural background, instruments used to assess depression, and sample characteristics in diabetes severity may account for the prevalence differences observed for different countries. Given the negative effects brought by the coexistence of depression and T2DM, it is suggested that in addition to regular blood glucose monitoring, routine screening of depression should be conducted among hospitalized T2DM patients by well-trained healthcare professionals in clinical practice in Hunan. Furthermore, timely and effective support such as psychosocial intervention and cognitive behavioral therapy should be implemented for those with comorbid depression [38, 39].

Socio-demographic characteristics such as sex, age, educational level, and income were found to be associated with comorbid depression among T2DM patients in many previous studies [34, 37, 40–46]. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Liu et al. [15], the pooled prevalence of comorbid depression among population-based T2DM patients in China was found to be higher in females, participants aged ≥60, those with a primary school or lower education, and individuals living alone. However, some studies showed different results. For example, Tran et al. [37] found that sex was not associated with comorbid depression among hospitalized T2DM patients, whereas Huang et al. [42] found that sex was independently associated with the prevalence and incidence of comorbid depression among diabetes patients in Taiwan. Similarly, Khan et al. [34] found that higher scores of depression were significantly associated with sex and age. This study showed that the prevalence of comorbid depression among T2DM patients was univariately but not independently associated with age, educational level, per capita monthly household income, and current work status. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct more studies with a larger sample of hospitalized T2DM patients to identify the association between socio-demographic characteristics and comorbid depression among hospitalized T2DM patients in China.

Regular physical activity is an important component of treatment strategies for diabetes patients, and its association with depression has been well-established among the general population [47, 48]. In diabetic populations, Mendes et al. [49] found that for older outpatients with diabetes, those with non-adherence to physical activity showed more depressive symptoms. Additionally, Ahola et al. [50] found that, after adjustments, more leisure-time physical activity was associated with more depressive symptoms in adult individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, a study using data from the Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey [51] found that moderate intensity physical activity at work and during leisure time affected depression. Similarly, the present study found that regular physical activity in hospitalized T2DM patients was associated with a lower risk of depression after adjustments. Therefore, it is highly recommended for healthcare professionals in China to promote healthy lifestyles, including regular physical activity, among hospitalized T2DM patients to help manage depressive symptoms. Additionally, as family support is crucial for adherence to physical activity, efforts should be made by family members to encourage increased physical activity among hospitalized T2DM patients.

Diabetic neuropathy affects up to 50% of diabetes patients and is a major cause of morbidity and increased mortality. Its clinical manifestations include painful neuropathic symptoms and insensitivity, which increases the risk of burns, injuries, and foot ulceration [52]. The presence of diabetic neuropathy could worsen quality of life and induce changes in social and family roles, thus increasing the risk of depression [53]. A previous meta-analysis with 13 eligible studies involving 3898 individuals confirmed the association between diabetic neuropathy and depression among T2DM patients [54]. However, the present study found that diabetic retinopathy was associated with depression in the univariable analyses but not in the fully adjusted multivariable model. It is worth noting here that in the multivariable model, the contribution of diabetic retinopathy to depression has reached the margin of statistical significance (aOR = 1.54, 95%CI: 0.93–2.54, P = 0.091). Therefore, caution should be taken when interpreting this association.

For T2DM patients, insulin is the cornerstone of treatment for lowering glucose and HbA1c concentrations [55]. Although the optimal timing and indications for insulin therapy remain controversial, most of the patients inevitably require insulin therapy to attain adequate glycemic control in the natural history of T2DM [56, 57]. In the present study, 75.40% of the participants were treated with insulin, and this group had a 1.86-fold risk of developing depression compared with their counterparts. This is consistent with a previous meta-analysis that included 12 eligible studies [58]. Compared with those who were not on insulin treatment, those on insulin treatment were more likely to have advanced T2DM with less endogenous insulin, increasing their susceptibility to metabolic dysregulation; hence, they were more vulnerable to develop depression [59]. Therefore, those on insulin treatment may need more regular check-ups for depression in clinical practice.

Social support is a psychosocial element that influences people by providing them with emotional, informational, companionship, and financial support to increase their adherence to diabetes treatment and management guidelines [60]. The protective role of social support against depression has been identified in different populations in secondary data analyses [61–63]. Accordingly, Azmiardi et al. [64] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 eligible studies involving a total of 3151 individuals and found that T2DM patients with lower social support had a two-fold risk of depression than those with greater social support. Similarly, this study found that higher social support was associated with a lower risk of depression after adjustments. These findings, therefore, underscore the importance of social support in the control and management of depression among hospitalized T2DM patients in China. Additionally, to build a systematic approach to reduce the burden of comorbid depression in T2DM, further studies on the mechanisms underlying this relationship are required.

This study found that nearly one fourth of hospitalized T2DM patients suffered from depression in Hunan, China. Considering the linkage between comorbid depression and subsequent poor health outcomes, routine screening for depression among hospitalized T2DM patients in this area is highly recommended. Insulin treatment strategies, regular physical activity, and social support were independently associated with depression. Therefore, the risk of comorbid depression among hospitalized T2DM patients might be reduced through enhancing physical activity and offering more social support in clinical practice, and those on insulin treatment should be paid special attention for preventing comorbid depression.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of the present study. This was a cross-sectional study, implying that the associations of insulin treatment strategies, regular physical activity, and social support with comorbid depression might be bidirectional. Based on the considerations of recall bias, this study collected information on current smoking and drinking instead of the amount and frequency of smoking and drinking, which might play an important role in the presence of depression. Therefore, future prospective studies are needed to elucidate the causal relationships. Additionally, this study was hospital-based with a single-centre of participants aged ≥40 in Hunan, and the mean duration of diabetes of the participants was 11.21 ± 7.75 years with the majority having duration of diabetes ≥10 years. This may preclude the possibility of identifying the association between newly-diagnosed diabetes and depression, and whether the findings can be generalized into all T2DM patients in Hunan remains unclear. Therefore, future studies with larger, more representative samples of T2DM patients are needed.

Conclusions

Depression is moderately prevalent with 27.22% of hospitalized T2DM patients suffering from depression in Hunan. Routine screening for depression among hospitalized T2DM patients in this area is highly recommended. Participants undergoing insulin treatment have a higher risk of comorbid depression, and those with regular physical activity or higher social support were at a lower risk of comorbid depression. The multivariable model based on the foregoing factors showed good predictivity, suggesting that it may be useful in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the patients participating in the study and all the staff involved at the Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- aOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence Interval

- HADS-D

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-depression subscale

- IQR

Interquartile range

- OR

Odds ratio

- ROC

Receiver operator characteristic

- SD

Standard deviation

- SSRS

The Social Support Rating Scale

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Authors’ contributions

WD contributed to the concept and design of this study. RM, WC, JX, ACK, XYW, LC, JY, and AL contributed to the data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. RM and WC drafted the manuscript. JX, ACK, XYW, LC, JY, and AL critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of publication.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82103939), the National Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant number 2021JJ40805), the start-up research fund of Central South University (grant number 202044003), and the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2020YFC2008600).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author Wenjie Dai (Email: m18673965791@163.com) on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed under the guidance of the Declaration of Helsinki (2008). The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (No. XYGW-2019-47). Informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rehanguli Maimaitituerxun and Wenhang Chen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Heald AH, Stedman M, Davies M, Livingston M, Alshames R, Lunt M, et al. Estimating life years lost to diabetes: outcomes from analysis of National Diabetes Audit and Office of National Statistics data. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab. 2020;9(4):183–185. doi: 10.1097/XCE.0000000000000210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Peng W, Zhao Z, Zhang M, Shi Z, Song Z, et al. Prevalence and treatment of diabetes in China, 2013-2018. JAMA. 2021;326(24):2498–2506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.22208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Wu Y, Wu J, Wang M, Wang X, Wang J, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes among adults in Beijing, China, from 2008 to 2017. Diabet Med. 2021;38(9):e14487. doi: 10.1111/dme.14487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . Depression. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(Suppl):S8–21. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(12)70004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semenkovich K, Brown ME, Svrakic DM, Lustman PJ. Depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Drugs. 2015;75(6):577–587. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukherjee N, Chaturvedi SK. Depressive symptoms and disorders in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(5):416–421. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin EH, Rutter CM, Katon W, Heckbert SR, Ciechanowski P, Oliver MM, et al. Depression and advanced complications of diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):264–269. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou Y, You W, Wang J, Wang F, Tian Z, Lu J, et al. Depression and retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2021;83(3):239–246. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2398–2403. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egede LE, Walker RJ, Bishu K, Dismuke CE. Trends in costs of depression in adults with diabetes in the United States: medical expenditure panel survey, 2004-2011. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):615–622. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3650-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tardif I, Guénette L, Zongo A, Demers É, Lunghi C. Depression and the risk of hospitalization in type 2 diabetes patients: a nested case-control study accounting for non-persistence to antidiabetic treatment. Diabetes Metab. 2022;48(4):101334. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2022.101334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khaledi M, Haghighatdoost F, Feizi A, Aminorroaya A. The prevalence of comorbid depression in patients with type 2 diabetes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on huge number of observational studies. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56(6):631–650. doi: 10.1007/s00592-019-01295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Li Y, Guan L, He X, Zhang H, Zhang J, et al. A systematic review and Meta-analysis of the prevalence and risk factors of depression in type 2 diabetes patients in China. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:759499. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.759499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolarinwa OA. Sample size estimation for health and social science researchers: the principles and considerations for different study designs. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2020;27(2):67–75. doi: 10.4103/npmj.npmj_19_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melin EO, Thunander M, Svensson R, Landin-Olsson M, Thulesius HO. Depression, obesity, and smoking were independently associated with inadequate glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168(6):861–869. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melin EO, Thunander M, Landin-Olsson M, Hillman M, Thulesius HO. Depression, smoking, physical inactivity and season independently associated with midnight salivary cortisol in type 1 diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:75. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Lin Y, Hu C, Xu Y, Zhou H, Yang L, et al. The Chinese version of hospital anxiety and depression scale: psychometric properties in Chinese cancer patients and their family caregivers. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;25:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olssøn I, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. The hospital anxiety and depression rating scale: a cross-sectional study of psychometrics and case finding abilities in general practice. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Z, Huang X, Liu X, Hou J, Wu W, Song A, et al. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Chinese version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in people living with HIV. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:346. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guidelines for medical nutrition treatment of overweight/obesity in China (2021 edition). Chinese J Front Med Sci (Electronic Version). 2021;13(11):1–55.

- 24.Naskar S, Victor R, Nath K. Depression in diabetes mellitus-a comprehensive systematic review of literature from an Indian perspective. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;27:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majdan M, Krajcovicova L, Pekarcikova J, Chereches R, O'Mullane M. Predictors of depression symptoms in patients with diabetes in Slovakia. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;44(4):351–366. doi: 10.2190/PM.44.4.e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebrahim M, Tamiru D, Hawulte B, Misgana T. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among diabetic outpatients attending diabetic clinic at public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211066244. doi: 10.1177/20503121211066244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clinical guidelines for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly in China (2022 edition). Chin J Internal Med 2022;61(1):12–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Xiao S. The theoretical basis and research application of social support rating scale. J Clin Psychol Med. 1994;02:98–100. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guoyu Y, Zhengzhi F, Benli X, Tiejun Z, Yunbo L, Tao W, et al. The reliability, validity and National Norm of social support scale in servicemen in Chinese. Chin Ment Health J. 2006;05:309–312. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Changfei L, Cunxian J, Jiyu Z, Xinxin W, Dongfang W, Liyuan L. Reliability and validity of social support rating scale in rural suicides in Chinese. Chin Ment Health J. 2011;25(3):218–22.

- 31.van Dooren FE, Nefs G, Schram MT, Verhey FR, Denollet J, Pouwer F. Depression and risk of mortality in people with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofmann M, Köhler B, Leichsenring F, Kruse J. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in individuals with diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farooqi A, Khunti K, Abner S, Gillies C, Morriss R, Seidu S. Comorbid depression and risk of cardiac events and cardiac mortality in people with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;156:107816. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan P, Qayyum N, Malik F, Khan T, Khan M, Tahir A. Incidence of anxiety and depression among patients with type 2 diabetes and the predicting factors. Cureus. 2019;11(3):e4254. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benmaamar S, Lazar N, El Harch I, Maiouak M, Qarmiche N, Otmani N, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with diabetes in a Moroccan region. Encephale. 2022;48(6):601–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Alzahrani A, Alghamdi A, Alqarni T, Alshareef R, Alzahrani A. Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among patients with type II diabetes attending primary healthcare centers in the western region of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13:48. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tran NMH, Nguyen QNL, Vo TH, Le TTA, Ngo NH. Depression among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence and associated factors in Hue City, Vietnam. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2021;14:505–513. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S289988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang ZD, Xia YF, Zhao Y, Chen LM. Cognitive behavioural therapy on improving the depression symptoms in patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Biosci Rep. 2017;37(2):BSR20160557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Xie J, Deng W. Psychosocial intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and comorbid depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2681–2690. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S116465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fugger G, Dold M, Bartova L, Kautzky A, Souery D, Mendlewicz J, et al. Major depression and comorbid diabetes - findings from the European Group for the Study of resistant depression. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;94:109638. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.AlBekairy A, AbuRuz S, Alsabani B, Alshehri A, Aldebasi T, Alkatheri A, et al. Exploring factors associated with depression and anxiety among hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Princ Pract. 2017;26(6):547–553. doi: 10.1159/000484929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang CJ, Lin CH, Lee MH, Chang KP, Chiu HC. Prevalence and incidence of diagnosed depression disorders in patients with diabetes: a national population-based cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(3):242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez-de-Andrés A, Jiménez-Trujillo MI, Hernández-Barrera V, de Miguel-Yanes JM, Méndez-Bailón M, Perez-Farinos N, et al. Trends in the prevalence of depression in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes in Spain: analysis of hospital discharge data from 2001 to 2011. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arambewela MH, Somasundaram NP, Jayasekara H, Kumbukage MP. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes attending the diabetic Clinic at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Sri Lanka: a descriptive study. Psychiatry J. 2019;2019:7468363. doi: 10.1155/2019/7468363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dehesh T, Dehesh P, Shojaei S. Prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among patients with type 2 diabetes in Kerman, Southern Iran. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:1509–1517. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S249385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding X, Rong S, Wang Y, Li D, Wen L, Zou B, et al. The Association of the Prevalence of depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus with visual-related quality of life and social support. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2022;15:535–544. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S343926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weyerer S. Physical inactivity and depression in the community. Evidence from the upper Bavarian field study. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(6):492–496. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ströhle A, Höfler M, Pfister H, Müller AG, Hoyer J, Wittchen HU, et al. Physical activity and prevalence and incidence of mental disorders in adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 2007;37(11):1657–1666. doi: 10.1017/S003329170700089X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mendes R, Martins S, Fernandes L. Adherence to medication, physical activity and diet in older adults with diabetes: its association with cognition, anxiety and depression. J Clin Med Res. 2019;11(8):583–592. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahola AJ, Tikkanen-Dolenc H, Forsblom C, Harjutsalo V, Groop PH. Symptoms of depression are associated with reduced leisure-time physical activity in adult individuals with type 1 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58(10):1373–1380. doi: 10.1007/s00592-021-01718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim DJ. Effects of physical activity on depression in adults with diabetes. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2018;9(4):143–149. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2018.9.4.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tesfaye S, Selvarajah D. Advances in the epidemiology, pathogenesis and management of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):8–14. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida S, Hirai M, Suzuki S, Awata S, Oka Y. Neuropathy is associated with depression independently of health-related quality of life in Japanese patients with diabetes. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(1):65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bartoli F, Carrà G, Crocamo C, Carretta D, La Tegola D, Tabacchi T, et al. Association between depression and neuropathy in people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(8):829–836. doi: 10.1002/gps.4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohn JH, Kwak SH, Cho YM, Lim S, Jang HC, Park KS, et al. 10-year trajectory of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity in the development of type 2 diabetes: a community-based prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Home P, Riddle M, Cefalu WT, Bailey CJ, Bretzel RG, Del Prato S, et al. Insulin therapy in people with type 2 diabetes: opportunities and challenges? Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1499–1508. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kramer CK, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Short-term intensive insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bai X, Liu Z, Li Z, Yan D. The association between insulin therapy and depression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(11):e020062. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Surwit RS, van Tilburg MA, Parekh PI, Lane JD, Feinglos MN. Treatment regimen determines the relationship between depression and glycemic control. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69(1):78–80. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strom JL, Egede LE. The impact of social support on outcomes in adult patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(6):769–781. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weldesenbet AB, Kebede SA, Tusa BS. The effect of poor social support on depression among HIV/AIDS patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2020;2020:6633686. doi: 10.1155/2020/6633686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schiller VF, Dorstyn DS, Taylor AM. The protective role of social support sources and types against depression in caregivers: a Meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(4):1304–1315. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rueger SY, Malecki CK, Pyun Y, Aycock C, Coyle S. A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychol Bull. 2016;142(10):1017–1067. doi: 10.1037/bul0000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Azmiardi A, Murti B, Febrinasari RP, Tamtomo DG. Low social support and risk for depression in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Prev Med Public Health. 2022;55(1):37–48. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.21.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author Wenjie Dai (Email: m18673965791@163.com) on reasonable request.