Abstract

Clostridium perfringens mutant strain 121A/91 shows neither enzymatic (phospholipase C) nor hemolytic activity. Nevertheless, the cpa gene and the corresponding alpha-toxin variant are detectable. Vaccination with this genetically constructed alpha-toxin variant, rAT121/91, induces antibodies capable of significantly reducing activities induced by wild-type toxin. Thus, rAT121/91 could be a useful vaccine candidate.

The alpha-toxin (42.5 kDa) of Clostridium perfringens, which is endowed with both phospholipase C (PLC, lecithinase) and sphingomyelinase activities (5), displays lethal activity in vivo and is cytolytic for erythrocytes from certain animal species (2, 10). No well-defined vaccine against C. perfringens alpha-toxin-associated diseases is available for use in humans or animals. The present study addressed an approach that had not been studied previously: the use of a naturally occurring, nontoxic alpha-toxin variant for vaccination. C. perfringens mutant strain 121A/91 was purchased from the German National Reference Center for Clostridia, Erfurt, Germany. C. perfringens reference strain ATCC 13124 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va. Strains were routinely cultivated in C. perfringens medium I at 37°C under anerobic conditions. Alpha-toxin-mediated lecithinase activity was assayed on the egg yolk salt agar (EYSA) described by Rigby (4). Additionally, mouse blood agar (Columbia agar containing 1% glucose and 5% mouse blood) was used to assay alpha-toxin-mediated hemolytic activity. Escherichia coli JM83 (16) was used as the host for gene cloning and protein expression. These cells were grown at 37°C by using Luria-Bertani agar or medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml for plasmid selection.

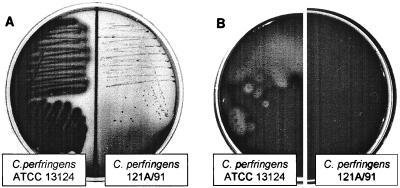

C. perfringens strain 121A/91 showed all of the morphological and biochemical characteristics of C. perfringens but produced no lecithinase activity on EYSA (Fig. 1A, right) and was nonhemolytic on mouse blood agar (Fig. 1B, right).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the alpha-toxin-related phenotypic characteristics of C. perfringens type A reference strain ATCC 13124 and strain 121A/91. (A) Bacterial growth of C. perfringens strains ATCC 13124 (left) and 121A/91 (right) on EYSA. (B) Bacterial growth of C. perfringens strains ATCC 13124 (left) and 121A/91 (right) on mouse blood agar.

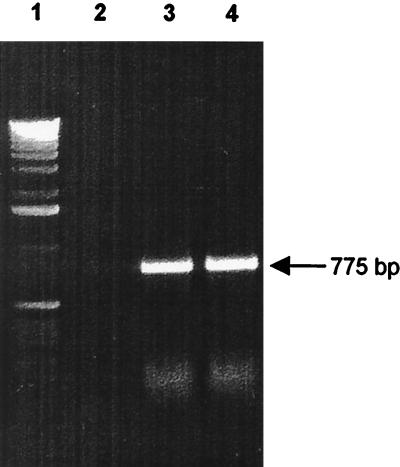

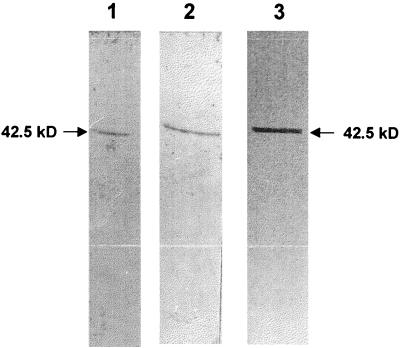

By PCR, as shown in Fig. 2, the predicted 775-bp cpa fragment was amplified from reference strain ATCC 13124 and strain 121A/91, confirming the taxonomic classification of strain 121A/91 as C. perfringens. The PCR was performed with oligonucleotide primers CP224 (5′-AGGAACTCATGCTATGATTGTAACTCAAGG-3′) and CP972i (5′-ACCACTAGTTGATATGTAAGCTACTAG-3′) as described previously (6, 7). To evaluate whether the lecithinase-negative, nonhemolytic phenotype demonstrated for C. perfringens strain 121A/91 is related to the poor transcriptional activity of its cpa gene or results from the expression and secretion of an intrinsically inactive gene product, we probed equivalent amounts of protein fractions extracted from the culture fluid of C. perfringens strains 121A/91 and ATCC 13124 with alpha-toxin-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) 3B4 (8) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (80, 40, 20, and 10 μg of protein extract; data not shown) and immunoblot analysis (20 μg of protein extract; Fig. 3). Both analysis demonstrated the presence of an alpha-toxin variant in the protein extract of strain 121A/91 that is specifically recognized by MAb 3B4 (1 μg/ml of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]-T20). These results ruled out the possibility that poor secretion of otherwise active alpha-toxin is responsible for the observed nonhemolytic and enzymatic phenotype of strain 121A/91. Furthermore, the immunoreactivities of MAb 3B4 against equivalent amounts of protein extracts from culture supernatants from strains 121A/91 and strain ATCC 13124 were found to be similar, irrespective of whether native (ELISA) or denaturing conditions (immunoblot analysis) were used for immunodetection. This observation indicated that the functionally important epitope on the 121A/91 alpha-toxin variant is presented in a manner similar to that on the wild-type (WT) toxin. Furthermore, the lack of functional activities in the 121A/91 alpha-toxin variant probably did not result from gross conformational changes in this protein in comparison to the WT toxin.

FIG. 2.

Detection of the cpa gene (775 bp) encoding C. perfringens alpha-toxin by PCR. Lanes: 1, DNA size marker (1- kb DNA ladder); 2, negative control (no template DNA); 3, C. perfringens ATCC 13124 (positive control); 4, C. perfringens strain 121A/91.

FIG. 3.

Immunoreactivity against alpha-toxin-specific MAb 3B4 (1 μg/ml of PBS-T20) of protein extracts from the culture supernatants of C. perfringens strains ATCC 13124 and 121A/91, as well as genetically constructed rAT121A/91, by immunoblot analysis. Lanes contained the following culture supernatants: 1, C. perfringens strain ATCC 13124 (20 μg of protein extract/slot); 2, C. perfringens strain 121A/91 (20 μg of protein extract/slot); 3, affinity-purified rAT121A/91 (3 μg/slot).

To clone a cpa gene fragment of the alpha-toxin variant, the PCR technique was applied by using the purified genomic DNA of strain 121A/91 and oligonucleotides VCP1 and VCP370. The primer sequences were determined on the basis of the ATCC 13124 cpa gene sequence published by Okabe et al. (3; GenBank accession no. M24904). VCP1 (5′-TACAATAGGCCTGGGATGGAAAGATTGA-3′) corresponded to nucleotides 85 to 101 of the ATCC 13124 cpa gene (underlined), with an additional 11-mer 5′ region that encodes the major part of an StuI restriction endonuclease site. Reverse primer VCP370 (5′-AGTCGGAGCGCTTTTTATATTATAAGTTGAATTTCC-3′) corresponded to the complementary sequence of positions 1310 to 1287 of the ATCC 13124 cpa gene (underlined), with an additional 12-mer 5′ region that encodes an Eco47III site. PCR was performed with 10 cycles consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min, followed by 20 cycles consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 63°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min and a final 5-min extension at 72°C. The resulting 1,133-bp DNA fragment was ligated with SmaI-digested plasmid pUC18 and sequenced.

Sequence analysis revealed the cloning of a 1,110-bp cpa gene fragment (cpa[121A/91-mAT]) that would encode the mature form of a structural variant of alpha-toxin. The predicted primary structure of this protein consists of 370 amino acids. By sequence comparison with the corresponding region of the cpa[ATCC 13124] gene (3, 11, 12), 12 point mutations were identified within cpa[121A/91-mAT] that result in eight amino acid substitutions in the 121A/91 alpha-toxin variant (Met13→Val13; Ala174→Asp174; Thr177→Ala177; His212→Arg212; Pro295→Gln295; Ser335→Pro335; Ile345→Val345; and Trp360→Gly360). In previous studies, four of these substitutions (Ala174→Asp174; Thr177→Ala177; Ser335→Pro335; and Ile345→Val345) were found to be relatively common, as they were also observed in several active alpha-toxin molecules produced by various C. perfringens strains (1, 13). Therefore we propose that the occurrence of the additional four amino acid substitutions (Met13→Val13; His212→Arg212; Pro295→Gln295 and Trp360→Gly360) must be of functional relevance for the loss of the activities but it was beyond the scope of this study to probe which of the additional substitutions present in the alpha-toxin variant of strain 121A/91 have functional consequences.

A 1,110-bp StuI and Eco47III restriction fragment of the cloned PCR product was ligated with the StuI/Eco47III-cleaved cloning site of E. coli expression vector pASK75 (9; Institut für Bioanalytik, Göttingen, Germany), yielding expression plasmid pHITI-1. E. coli JM83 carrying pHITI-1 was used for the periplasmic expression of rAT121A/91 consisting of the mature 121A/91 alpha-toxin variant with its carboxy terminus fused to the StreptagI affinity peptide (14). rAT121A/91 was purified by using Streptactin-Sepharose resin (14; Institut für Bioanalytik). By ELISA (data not shown) and immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3), it was shown that WT-specific MAb 3B4 (8) reacted with purified rAT121A/91, irrespective of whether the recombinant protein was presented in a native conformation (ELISA) or under denaturing conditions (immunoblot). From this result, it can be concluded that rAT121A/91 has a conformation with a strong resemblance to both the 121A/91 alpha-toxin variant and the native WT toxin.

After intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of purified rAT121A/91 (10, 20, 40, or 80 μg in 500 μl of PBS (pH 7.4) into 6-week-old female NMRI mice (six per group), none of the animals showed any clinical symptoms of intoxication within the observation period of 72 h. A threefold 50% lethal dose of active WT toxin (4.8 μg) was administered i.p. to a group of six mice as a positive control. All of the animals died within 4 h after inoculation.

Twelve 8- to 9-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized i.p. with 50 μg of purified rAT121A/91 on days 0 and 21. The antigen was administered in 165 μl of PBS (pH 7.4) mixed with 100 μl of an oil-water emulsion adjuvant. A strong antibody response of the murine anti-rAT121A/91 (titers of up to 1:128,000) against both self and WT toxin was measured by ELISA (data not shown). The ability of murine anti-rAT121A/91 sera to neutralize the hemolytic activity of WT toxin (0.5 μg in 112.5 μl of isotonic washing buffer [WB]) was analyzed by preincubation of WT toxin for 30 min at 37°C with murine anti-rAT121A/91 sera and sera from nonimmunized animals. After preincubation, each sample was mixed with 250 μl of a washed mouse erythrocyte suspension and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After centrifugation (1,500 × g, 10 min at room temperature), the absorbances of the supernatants were measured at 540 nm. Murine anti-rAT121A/91 hyperimmune sera were able to significantly reduce the hemolytic activity of WT toxin (Table 1). Similarly, the lecithinase activity of WT toxin in vitro was significantly inhibited after preincubation with anti-rAT121A/91 serum (data not shown). Since the hemolytic activity and lethal effects of alpha-toxin are intimately linked to each other (10) and protection against the hemolytic activity of the toxin also seems to be critical for achieving protection against the lethal activity of alpha-toxin (15), it is reasonable to expect that protective immunity against C. perfringens could be established in vaccinees after immunization with recombinant inactive alpha-toxin variant rAT121A/91.

TABLE 1.

Reduction of alpha-toxin-induced hemolysis of erythrocytes by preincubation of alpha-toxin with mouse anti-rAT121A/91 hyperimmune serum

| Incubation of mouse erythrocytes with: | % Hemolysisa |

|---|---|

| Mouse anti-rAT121A/91 hyperimmune serum | 7.3 ± 8.92 |

| Mouse preimmune serum | 6.8 ± 2.58 |

| IWB | 6.1 ± 0.79 |

| 0.5 μg of alpha-toxin preincubated with IWB (positive control) | 99.2 ± 7.44 |

| 0.5 μg of alpha-toxin preincubated with mouse preimmune serum (negative control) | 100.0 ± 4.33 |

| 0.5 μg of alpha-toxin preincubated with mouse anti-rAT121A/91 hyperimmune serum | 11.5 ± 2.6 |

The values shown are for triplicate measurements.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ginter A, Williamson E D, Dessy F, Coppe P, Bullifent H, Howells A, Titball R W. Molecular variation between the α-toxins from the type strain (NCTC 8237) and clinical isolates of Clostridium perfringens associated with disease in man and animals. Microbiology. 1996;142:191–198. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonel J L. Toxins of Clostridium perfringens types A, B, C, D and E. In: Dorner F, Drews J, editors. Pharmacology of bacterial toxins. Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press; 1986. pp. 477–517. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okabe A, Shimizu T, Hayashi H. Cloning and sequencing of a phospholipase C gene of Clostridium perfringens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;160:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91616-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rigby G J. An egg-yolk agar diffusion assay for monitoring phospholipase C in cultures of Clostridium welchii. J Appl Bacteriol. 1981;50:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1981.tb00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saint-Joanis B, Garnier T, Cole S T. Gene cloning shows the alpha-toxin of Clostridium perfringens to contain both sphingomyelinase and lecithinase activities. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219:453–460. doi: 10.1007/BF00259619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlapp T, Blaha I, Bauerfeind R, Wieler L H, Schoepe H, Weiß R, Baljer G. Synthesis and evaluation of a non-radioactive gene probe for the detection of C. perfringens alpha toxin. Mol Cell Probes. 1995;9:101–109. doi: 10.1016/s0890-8508(95)80034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoepe H, Potschka H, Schlapp T, Fiedler J, Schau H, Baljer G. Controlled multiplex PCR of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens strains in food samples. Mol Cell Probes. 1998;12:359–365. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1998.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoepe H, Wieler L H, Bauerfeind R, Schlapp T, Potschka H, Hehnen H-R, Baljer G. Neutralization of haemolytic and mouse lethal activities of C. perfringens alpha-toxin need simultaneous blockade of two epitopes by monoclonal antibodies. Microb Pathog. 1997;23:1–10. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skerra A. Use of the tetracycline promoter for the tightly regulated production of a murine antibody fragment in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1994;151:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Titball R W. Bacterial phospholipases C. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:347–366. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.347-366.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Titball R W, Hunter S E C, Martin K L, Morris B C, Shuttleworth A D, Rubidge T, Anderson D W, Kelly D C. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the alpha-toxin (phospholipase C) of Clostridium perfringens. Infect Immun. 1989;57:367–376. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.367-376.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tso J Y, Siebel C. Cloning and expression of the phospholipase C gene from Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium bifermentans. Infect Immun. 1989;57:468–476. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.468-476.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsutsui K, Minami J, Matsushita O, Katayama S-I, Taniguchi Y, Nakamura S, Nishioka M, Okabe A. Phylogenetic analysis of phospholipase C genes from Clostridium perfringens types A to E and Clostridium novyi. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7164–7170. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7164-7170.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voss S, Skerra A. Mutagenesis of a flexible loop in streptavidin leads to higher affinity for the Strep-tag II peptide and improved performance in recombinant protein purification. Protein Eng. 1997;10:975–982. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.8.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson E D, Titball R W. A genetically engineered vaccine against the alpha-toxin of Clostridium perfringens protects mice against experimental gas gangrene. Vaccine. 1993;11:1253–1258. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]