Abstract

In recent years, new expectations have been placed on universities, demanding academic contributions towards solving large-scale, interdisciplinary challenges. This is in conflict with existing insights from university governance research, which emphasises that scientific communities focus on reproducing disciplinary practices that are unsuitable in addressing societal challenges, because the problems associated with them are usually large-scale, complex and interdisciplinary. In light of this seeming paradox, we revisit the question of how—and on which theoretical grounds—universities may still be able to develop suitable internal governance mechanisms that allow them to address complex societal challenges effectively. Because university leaders are usually unable to coerce individual researchers to address such challenges in their research simply through their bureaucratic powers, we will argue that university leaders can, however, leverage individual researchers' agency to deviate from routine and disciplinary practice by developing novel or legitimising existing interdisciplinary scripts necessary to deal with such societal problems. Specifically, we outline that university managements can create a dual role consisting of the communication of legitimising interdisciplinary research on societal challenges, as well as providing for the necessary degree of interdisciplinary coordination by convening researchers around these topics.

Keywords: University, Governance, Change-agency, Interdisciplinary, Societal challenges

Introduction

In the face of urgent large-scale societal challenges (Rittel and Webber 1973; Head 2022), universities are increasingly expected to fulfil a new functional role within society as problem-solving organisations working on solutions to complex societal challenges (Fam et al. 2020; Nowotny et al. 2001).While this social desirability goal is incontrovertible, research suggests that universities may not offer an ideal organisational setting because addressing societal challenges tends to require a high degree of interdisciplinarity and the involvement of actors from multiple backgrounds (Orton and Weick 1990; Elken and Vukasovic 2019; Head 2022). This can be at odds with the disciplinary pressures of the scientific communities in which most researchers are strongly embedded (Stichweh 1992). Moreover, even if individual researchers resist these disciplinary pressures, they will often find it hard to trigger a sufficient level of collective and concerted action that, in order to address large-scale problems, will be also required (Head and Alford 2015; Marchant 2020). This double challenge casts doubt on whether universities are, in fact, well-positioned to address large-scale, complex problems (Orton and Weick 1990; Gibbons 1994; Krücken and Meier 2006; Hattke et al. 2016; Seeber et al. 2015; Hannon et al. 2018; Elken and Vukasovic2019; Horta 2022). Against this background, we propose that university leaders may gain an important dual role that, on the one hand, consists of legitimising interdisciplinary research scripts and, on the other hand, provides for the necessary degree of coordination.

To make our argument, we develop a multilevel framework of change agency in universities that revisits the interplay between (a) individual researchers, (b) the disciplinary scientific communities in which the researchers are embedded, and (c) university leaders. In this model, disciplinary communities inhibit the emergence of interdisciplinary research scripts under two conditions. Firstly, if they are strong enough, they restrict researchers' actions to that which is foreseen and stipulated by disciplinary research scripts (Stichweh 1992; Hattke et al. 2016; Vereijken et al. 2022). Addressing societal challenges is thus made difficult because pressure on disciplinarity delegitimises interdisciplinary scripts (Fini et al. 2021). Secondly, if they are weak because of, for example, the existence of overlapping neighbouring disciplinary communities, they create “opportunity haziness”, understood as the existence of diverse, partially conflicting scripts among which none is dominant enough to provide a commonly accepted and obvious framework of reference (Dorado 2005).

This haziness results in incomplete knowledge about viable research opportunities, standards and practices, and thereby creates impediments to interdisciplinary coordination, leaving researchers to engage in dispersed sense-making agency without strategic intent. They are thus likely to erratically switch between aligning their activities to diverse disciplinary and/or interdisciplinary research scripts so that the resulting level of interdisciplinary coordination remains insufficient to effectively address complex societal challenges. A first important conclusion from this model is thus that although strong disciplinary communities tend to inhibit interdisciplinary research, the mere act of weakening them does not necessarily result in an increased capacity to address complex societal challenges.

In the following, we instead propose that the solution to this dilemma lies in the effective appreciation of individual researchers' agency, i.e., their ability and inclination to collectively engage in interdisciplinary work, once pressures exerted by overt disciplinarity or opportunity haziness have been overcome. Consequently, university leaders can thus play a beneficial dual role in helping to reduce the inhibiting effects of disciplinary pressures and opportunity-hazy settings. On the one hand, they can exert leverage using their coordinative abilities by convening researchers for interdisciplinary projects that address societal challenges. Departing from suggestions in the existing literature, however, we add that while convening researchers is effective in the short run, its effect may be local and temporary unless disciplinary mindsets change on a broader scale. Hence, we suggest that, in the long run, university leaders should also aim to change the mindsets of existing staff and engage in legitimising interdisciplinary research scripts at individual level by communicative means; for example, by creating work groups, defining organisational missions and goals, or creating commonly accepted, novel narratives. Thus, the third conclusion of our model is that although the two mechanisms are largely complementary, a constant orientation towards addressing societal challenges is critically dependent on changing individual mindsets. This view underlines the relative importance of communicative mechanisms over proactive yet temporary convening processes.

The contribution of our paper is threefold. First, much of the existing literature has been sceptical about the notion of effective steering by university leaders because of their limited leverage in efficiently executing detailed bureaucratic control (Cohen et al. 1972; Weick 1976; Blaug 1976; Bleiklie et al. 2015; Orton and Weick 1990). Moreover, it highlighted that university leaders are not well-informed about suitable activities to address concrete problems, making coercive bureaucracy, in the form of establishing concrete interdisciplinary research lines, ineffective (Liefner 2003; Hattke et al. 2016). Our approach acknowledges this but still comes to a different conclusion: it does not build on the notion of detailed bureaucratic control, but instead emphasises opportunities arising from communicative legitimation and proactive convention. Communicative legitimation is a deliberate instance of soft governance. However, even convening researchers on interdisciplinary projects cannot be described as bureaucratic control, because although it may be implemented by incentivising, and even convincing researchers to participate in internal projects, the concrete definition of the project is still left to researchers. In that respect, our approach is in line with the existing literature emphasising the potential of soft governance (Courpasson and Clegg 2012; Hales 2002).

Second, our research has an important implication for the role attributed to disciplinary communities. While recent research has critically reflected on their role as gatekeepers delegitimising interdisciplinary research (Fini et al. 2021), we argue that weakening them will not in itself solve the issue because this could simply result in increased opportunity haziness. In fact, because disciplinary communities are often well-suited to solve disciplinary problems of lower complexity (Orton and Weick 1990), a mere weakening of them may impair not only a university's capability of producing knowledge, but also a fundamental and valuable structural mechanism of academia without necessarily achieving much in terms of increasing a university’s ability to address complex societal challenges.

Third, our approach is of practical importance. The de facto increasing presence and urgency of complex challenges, as well as their increasing reflection in science and innovation policies, places new expectations on universities concerning their role and function, from which follows a perceived need for changes in researchers’ activities (Donina et al. 2017; Leišytė et al. 2022), and from which follows a need to adapt internal governance (Bleiklie and Michelsen 2013) in such a way that the aggregate of individual researchers' actions will enable universities to better fulfil their extended function (Donina et al. 2017). By emphasising the role of legitimising interdisciplinary research on societal challenges, and providing coordination through convening researchers, our approach gives practical guidance for university leaders on how to adapt internal governance structures. More specifically, our model suggests that proactive convention is by no means the only approach to effectively promote change agency (Dorado 2005). Instead, it implies that the effects of pro-active convention may remain temporary so that complementary activities in the domain of communication will be required to effect lasting change.

While much of the subsequent argument will be built on literature on the German university system, we maintain that the fundamental, conceptual implications of our argument will apply to other national contexts as well, even if the degrees of freedom that specific actors hold in different domains will differ between countries.

Framework of Analysis

Academic routines for problem solving tend to be based primarily on disciplinary rather than on specific organisational scripts. These routines are well-suited to solving smaller types of emergent problems, and reflect the internal logics of broader disciplinary communities in a university’s sub-units (Orton and Weick 1990). While not exclusive as references, they exert a dominant influence on all researchers' behaviour, thematic preferences and methodological choices (Hattke et al. 2016; Vereijken et al. 2022). At the same time, they are ill-equipped to address large-scale societal issues that require interdisciplinary coordination, the orchestration of efforts across disciplinary boundaries (Lyall and Meagher 2012), a focus on problem solving (Wickson et al. 2006), and the involvement of a diverse set of stakeholder groups (Mitchell et al. 2015; Dentoni and Bitzer 2015; Donina et al. 2017).

While university leaders may appear as natural actors to provide for such interdisciplinary coordination, the extant literature has been quite clear that detailed bureaucratic control is usually an ineffective governance mechanism (Cohen et al. 1972; Weick 1976; Mintzberg 1979; Bleiklie et al. 2015; Engwall 2018). The specific question of reorienting research towards topics related to complex challenges is unlikely to be an exception to this rule (Oliver 1991; cf. Anderson 2008; Hüther and Krücken 2013) . Instead, we will argue that the key to promoting research on societal challenges lies in leveraging individual researcher’s agency. Thus, instead of resorting to bureaucratic top-down control, effective university leaders will have to convince researchers to develop or at least accept alternative interdisciplinary approaches by themselves, as a complement to their 'standard' disciplinary activities.

Following on from this general premise, we develop a model of embedded, multi-level agency in university organisations. This model posits that many current routine interactions of scholars in their disciplinary communities produce a pattern of reproductive agency, which currently tends to delegitimise interdisciplinary work (Fini et al. 2021). At the same time, overlapping and competing scientific communities present a notable level of institutional ambiguity that provides a fertile ground for transdisciplinary work at their interfaces. As we will demonstrate, this type of ambiguous setting provides university management with the option to create room for change agency by amplifying institutional ambiguity and, at the same time, providing referents and legitimacy for interdisciplinary work.

Scientists as Agents Between Continuity and Change

As established in a secular strand of social science literature, human interactions give rise to social and cognitive proximity (Boschma 2005), which facilitates the emergence of subsequent exchanges along similar routes and among similar actors (Giddens 1984). Such interactions are referred to by most authors as reproductive or routine agency. Eventually, such routinized, often unexamined repetition of actions gives rise to scripts, conventions and norms for future interactions (Giddens 1984; Barley 1997; Barley and Tolbert 1997). The accumulation of these may eventually translate into hard rules and institutions, or even manifest in organisations aligning themselves with overarching institutional requirements (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Greenwood et al. 2002). In this manner, institutional fields and organisational structures are continuously reconstituted by the continuity of exchanges between the individual agents of which they comprise (Lounsbury and Crumley 2007; Leca et al. 2009; Weik 2011; Abdelnour et al. 2017).

Despite existing constraints set by institutional fields, we understand academics as individuals who are capable of strategically motivated, rationally deliberated action endowing them with agency. Quite evidently, an academic’s agency does not result from adhering to past practice alone but as much from their autonomous perspectives on both the present and the future (Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Seo and Creed 2002). To an extent, interpersonal interactions will reproduce prior practice, as all actions happen "through" existing structures (Abdelnour et al. 2017; Cardinale 2018; Lok and Willmott 2019). However, they also remain vibrant and dynamic, and will unintentionally deviate from existing scripts, as well as by conscious choice (Seo and Creed 2002; Leca et al. 2009; Battilana and D'Aunno 2009).

In any case, a departure from established routines and the resulting institutional framework can only take place if individual agents consciously decide to depart from past practice, turning towards the future (Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Leca et al. 2009), regardless of whether they do so with (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Beckert 1999) or without (Bourdieu 1988; Giddens 1984) strategic objectives in mind. Fundamentally, it is therefore necessary to distinguish between reproductive routine agency, which is motivated by past practice and its resulting institutions; sense-making agency (Bourdieu 1988; Weick 1995), which is triggered by the absence of institutional referents but not by concrete ambitions; and genuine strategic agency (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Orton and Weick 1990; Beckert 1999; Weik 2011), which is motivated by the active intent to change existing organisations and institutions (Dorado 2005; Battilana and D'Aunno 2009). Since addressing complex societal problems requires a high degree of interdisciplinary coordination to strategically transcend existing disciplinary scripts, neither routine nor dispersed sense-making agency will provide an adequate basis for effective action. Instead, a focus must be on placed on strategic change agency and, more specifically, on collective change agency.

Prior research in sociology has shown that the degree to which individual agents can exert strategic change agency depends on the diversity of institutional referents to which they have access, as well as on the dominance of the prevailing script among those to which they are exposed (Dorado 2005). Beyond the organisation-internal/organisation-external dichotomies discussed in much of the literature on universities (Hattke et al. 2016; Doyle and Brady 2018), this leads us to acknowledge that the array of institutional referents relevant for specific organisational sub-units (Orton and Weick 1990) can be complex, diverse and constituted from different levels (Frost et al. 2016; Hasanefendic and Donina 2022). Empirically, individual researchers' existing exposure and potential to access additional institutional referents will manifest itself in the structure of their professional social relations (Boschma 2005). If they maintain these relations solely within their disciplinary community, it is likely that they are primarily exposed to one dominant script and have little capacity to perceive additional ones. If they maintain occasional and ephemeral relations to actors from other fields and organisational contexts, it is likely that they are at least aware of alternative scripts, yet without those developing much practical relevance for them. Finally, some of them may cross-disciplinary and organisational boundaries so frequently that they can, on a case-to-case basis, actively choose under which framework to operate.

Borrowing once more from existing insights in sociology, the resulting organisational fields affecting individual researchers can be described as opportunity-opaque (dominated by one characteristic, disciplinary script), opportunity-transparent (characterised by different, clearly identifiable scripts among which one remains dominant) or opportunity-hazy (characterised by diverse, partially conflicting scripts among which none is dominant) (Dorado 2005). Because most universities are characterised by the coexistence of different disciplinary scripts, they can—as organisations—hardly be opportunity-opaque. Instead, they will be either opportunity-transparent or opportunity-hazy.

In the next subsection, we therefore argue that the type of dominant agency (routine agency, sense-making agency, strategic-change agency) will depend on whether the environment is opportunity-transparent or -hazy, and on whether it is dominated by disciplinary vs. interdisciplinary orientation.

Disciplinary Communities as Guardians of Routine

In the existing literature, scientific communities have been described most vividly by Hattke et al.’s (2016) image of "invisible colleges" that transcend organisational boundaries and that correspond to the institutional fields of the disciplinary communities to which all academics primarily refer. Within universities, this leads to the intersection of inter-organisational, disciplinary and intra-organisational, transdisciplinary fields at the level of individual sub-units (Orton and Weick 1990; Bleiklie et al. 2015).

These external communities determine central institutional scripts relevant for all researchers, from reward systems, to requirements in appointment procedures, from established norms of research teaching, to their generic position towards applied science—different academic disciplines can provide fundamentally different conditions for individual decisions and actions. More indirectly, disciplinary environments create specific identities, which in turn impact on many relevant rationales for action, with which individual academics try to comply in an effort to build legitimacy (DiMaggio and Powell 1983).

Despite their importance of the disciplinary structure, disciplinary communities differ substantially in their strength (Dorado 2005). In some cases, they define clear, visible and close to unavoidable rules, practices and norms for research to fulfil disciplinary standards. In this case, the environments created by them can be characterised as opportunity-transparent, because from the perspective of an individual researcher, there is one single disciplinary script that applies to him or her and shapes his or her actions. However, since this script is a disciplinary one, the relevant institutional referents support and sustain disciplinary practices, and agency will be largely routine-based (Dorado 2005; Engwall 2018). In this situation, any emergence of change agency is unlikely if the system is left to operate on its own terms. Alternatively, weakly developed disciplinary communities may render a researcher’s environment opportunity-hazy. In such opportunity-hazy university environments, the overlap of institutional fields is the norm (Hattke et al. 2016; Doyle and Brady 2018) so that in the absence of other options, academics resort to dispersed sense-making agency. Outside their established disciplinary field, they lack a clear framework of reference and, seeking orientation, try their best to take sensible action under conditions of limited information. Under these circumstances, strategic coordination becomes difficult, and researchers may erratically switch between disciplinary and interdisciplinary scripts because they seek to reconcile different demands on their own, without reference to any authoritative practice.

It is now clear, that both the disciplines of scientific communities and dispersed activities of individual researchers are unlikely to bring about the type of strategic agency that is required to address—and improve—organisations capacity for addressing more complex societal challenges. If communities discipline is strong, research practices are clear but discipline and agency is routine-based. If they are weak, disciplinary orientation becomes weaker, but organisational haziness increases, which in turn prevents a necessary degree of interdisciplinary coordination. In fact, this mechanism explains why simply reducing the influence of the disciplines of scientific communities would not as such result in more targeted and concerted interdisciplinary efforts, but rather in dispersed and undirected activities of researchers switching erratically between different disciplinary and interdisciplinary scripts. It also explains why—in practice—we often see so little strategic orientation towards interdisciplinarity because there is an obvious need for a third actor to solve the dilemma. Individual-level agency and disciplinary community structure can bring about only disciplinary scripts based on routine agency or unguided erratic switching back and forth between unclear scripts. In the next section, we will argue that, despite the prevalent scepticism, university management can indeed solve this dilemma.

University Management as Enablers of Change

Although acknowledging that attempts at hierarchical bureaucratic control may indeed be ineffective in universities (Orton and Weick 1990; Bleiklie et al. 2015), we maintain that a general dysfunctionality of university management does not necessarily follow. Since the discourse on new public management reinvigorated the discussion on the options and potential modalities of universities and developing them "as organisations" (Doyle and Brady 2018; Hüther and Krücken 2018; Kosmützky 2016; Krücken and Meier 2006), more and more scholars now contend that universities should be considered complete organisations (Bleiklie 2007; Krücken and Meier 2006; Seeber et al. 2015) in which central units can and will inevitably assume some governing role, and hence a complementary type of agency in shaping the organisations' development. Although in many countries, researchers are bestowed with some level of fundamental de jure autonomy that cannot be revoked at organisational level, university management has substantial leverage over its sub-units by performing a gatekeeper function, deciding on access to resources and consequently over the de facto viability of a large share of activities that academics seek to pursue within the university's organisational context (Blümel 2016).

Likewise, it follows from general findings in organisational studies (Courpasson and Clegg 2012; Hales 2002) that university management has diverse options to deploy “soft” governance approaches like motivation, persuasion and incentivisation to legitimise interdisciplinary research and problem-oriented scripts (Bleiklie et al. 2017; Doyle and Brady 2018). In the extant literature, several dimensions of (the practice of) leadership have been identified, based on which universities’ management can seek to influence the actions of individual groups of agents (Bolden et al. 2008). Arguably, all staff within a university are, at least to some extent, susceptible to incentives or to directives issued by central leadership (Boitier and Rivière 2016; Weiherl and Frost 2016; Doyle and Brady 2018; Frost et al. 2016), and in any case have to regularly engage with them as a procedural matter of course.

With both policy makers and their supporting constituencies show a strong leaning towards grand societal challenges and public missions (Boon and Edler 2018; Borrás and Edler 2020), universities have been increasingly challenged to develop their capacity to respond to those at an organisational level. Also, their ability to do so has become more important in defending the value of academic work in the policy domain (Välikangas and Lewin 2022). Against this background, several authors have assessed and conceptualised universities' ability to comply with societal requirements and the institutional changes that confront them at an organisational level (Frost et al. 2016; Musselin 2021; Whitley 2008). In general, they find that many university management teams have begun to respond to these new requirements (Blaschke et al. 2014; Kosmützky 2016; Välikangas and Lewin 2022) and, in the process, seek to develop the strategic capabilities of their organisations (Boer et al. 2007; Krücken and Meier 2006; Meier 2009).

Specifically, university management has a number of tangible levers of power at its disposal with which it can limit or encourage change agency; for example, it can withhold or grant access to certain resources (e.g., for larger equipment and buildings), to strategic information and strategic projects, and it can deny or approve appointments (Blaschke et al. 2014; Bolden et al. 2008; Leiber 2021; Woiwode et al. 2017). Thus, it can, to no small extent, influence the institutional referents that are de facto accessible from within the organisation, and even decide to establish new ones if it so chooses (Blaschke et al. 2014; Dentoni and Bitzer 2015; Donina et al. 2017; Hüther and Krücken 2013; Doyle and Brady 2018; Frost et al. 2016).

By thus partly controlling and shaping institutional referents available to researchers under its remit, university management can potentially solve the dilemma of the interplay of individual-level and disciplinary structure leading either to opportunity-transparent situations dominated by disciplinary routine agency, or to opportunity-hazy, sense-making agency, erratically switching between different disciplinary and interdisciplinary scripts. Notably, university leaders can function as an additional source of structure, which results in environments that are, on the one hand, opportunity-transparent and, on the other, will allow for strategic interdisciplinary research. In the next section, we will explain how university management can achieve this structure.

Conditions of Continuity and Change

Preconditions for Change Agency

We have made a case that the solution to the dilemma of disincentivisation of strategic disciplinary research does not lie in the weakening of institutional referents created by disciplinary communities, but in the strengthening of institutional referents associated with interdisciplinary research. We further pointed out that the weakening of disciplinary scripts and referents will most likely result in dispersed sense-making agency (Beckert 1999; Dorado 2005), which is unlikely to increase any organisation's aggregate capacity to address complex problems (Weik 2011). To achieve a sufficient level of mobilisation, the main challenge will be to expose a sufficient share of the collegiate to alternative referents, in a coordinated manner that improves its capacities for collective action. In order to increase a university’s ability to address larger societal problems at an institutional level, it is essential to encourage and trigger not only dispersed but also coordinated collective change agency.

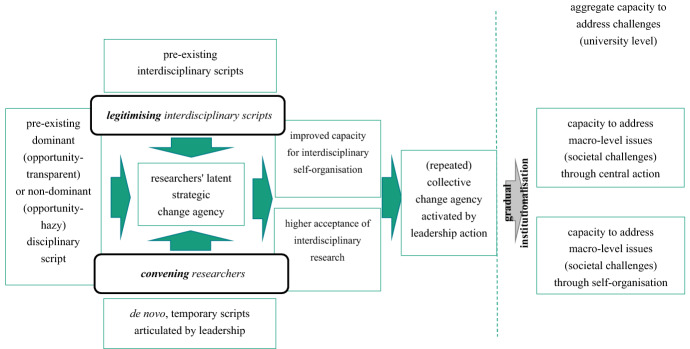

To understand how this could be achieved and which role university managers' agency could play in this context, it is necessary to establish in what manner and through which channels individual actors can gain access to either existing or novel—but also alternative—institutional referents, which enable and encourage them to initiate the large-scale interdisciplinary efforts that are needed to effectively address complex challenges. In this regard, two different ways, through which additional exposure could come about, can be distinguished as follows (cf. also Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

An agency-centred governance model

Against this background, three main aspects of exposure have to be determined to establish an individual researcher’s propensity to develop change agency (Fig. 1): first, the ex-ante dominance of their exposure to established disciplinary scripts (in terms of its inevitability with regard to career and financing); second, the extent to which they are exposed to alternative, already existing but interdisciplinary scripts; and, third, the extent to which they are exposed to novel, alternative interdisciplinary scripts established locally within the organisation.

The exposure to pre-existing disciplinary and interdisciplinary scripts determines whether environments are ex-ante opportunity-hazy or -transparent and whether, in the absence of university management action, individual agency will mostly be routine-based or rather erratic and sense making. Notably, change agency, at least collective change agency, is analytically not possible without management action because pre-existing interdisciplinary scripts will either be suppressed where disciplinary practices are strong, or form an unstable, confusing array where they are weak—since no independent structural force exists that would maintain them. This opens up the room for university management action. More specifically, university management can convene researchers to interdisciplinary projects or legitimise interdisciplinary scripts by communicative means. The convening of researchers constitutes a short-term centralised measure, typically implemented through the creation of projects where participation is financially incentivised (for example, where management holds control over the budget). Instead, the communicative legitimation of interdisciplinary research is a longer-termed attempt to change researchers' minds and attitudes towards interdisciplinary research. It builds on decentralised, subsidiary action and relies on self-organisations. Despite these differences, both approaches can effectively stabilise pre-existing or nascent interdisciplinary scripts, either by centralised convention or decentralised self-organisation. Of course, the same strategies can also contribute to creating stable interdisciplinary scripts de novo. Both the stabilisation process and the de novo creation will turn an ex-ante disciplinary opportunity-transparent into a hybrid disciplinary-interdisciplinary, opportunity-transparent environment. Alternatively, it will turn an ex-ante erratic opportunity-hazy into an interdisciplinary opportunity-transparent environment.

In either case, the result will be an opportunity-transparent environment, which displays some level of directed, collective change agency, and improve individual researchers' acceptance of interdisciplinary research and their capacity for interdisciplinary self-organisation. At an organisational level, these interdisciplinary scripts become routinized over time and will result in an increased capacity to address societal challenges.

Manager's Options to Change Researchers' Exposure

As mentioned above, a university's capacity to address complex challenges will improve if the equilibrium of individual researchers' exposure to different institutional scripts shifts from one determined by dominant disciplinary scripts or a discord of partially perceived different ones, to one in which alternative interdisciplinary scripts become clearly discernible as the basis for action. We have already mentioned that this can happen in two ways: by convening researchers, or by communicatively legitimising interdisciplinary scripts. In concrete terms, the activities connected to convening scientists and legitimising scripts can be described as follows.

In line with Dorado's (2005: 408) definition of convening as the "establish[ment] of collaborative linkages", convening refers to bringing together scientists in projects in which central management serves as the main coordinator of expenses, and in that capacity has authority to direct or at least to participate in specific activities. As legitimation, however, we designate activities in which university management encourages faculty to partake in interdisciplinary, problem-oriented calls without itself assuming a formal role. Nonetheless, its discursive leadership extends beyond mere acclamation or advice through the usual hierarchical channels. It would find itself expressed in, for example, the set-up of working groups and discussion forums on specific topics through which university managers convey ideas not only to deans but also to a broader circle of thematically interested colleagues who might subsequently be willing to assume responsibility for concrete action. Likewise, university management would not simply let such efforts happen but would set up suitable reporting structures for remaining aware of changing patterns of behaviour. And thus, be able to identify leverage point for further discursive support in the future.

While both can be effective, we have already hinted at differences in the nature of their effectiveness, in particular from a time perspective. On the one hand, convening researchers for interdisciplinary projects is a quick and, in the short-term, effective mechanism. However, it is unlikely to change attitudes towards interdisciplinarity because it only applies to participating researchers, who might fall back to disciplinary scripts once the project ends. To sustain the effects, continuous central efforts to organise and maintain interdisciplinary projects with a wide participation would remain crucial—if nothing else were to change. On the other hand, communicative legitimation is likely to take effect more slowly because it is a more indirect mechanism, which neither coerces nor incentivises researchers to take part in any concrete interdisciplinary action but leaves this to self-organised change. In this case researchers become aware of additional institutional referents, but their latent capacity for self-organised change agency will be activated only once concrete opportunities present themselves frequently enough to affect routines on a broader basis (Dorado 2005). In the meantime, the danger of dispersed agency may persist and organisations remain hazy with respect to interdisciplinary opportunities over longer periods. However, incrementally changing the basis of individual researchers' sense-making agency will eventually accumulate in institutional change within and beyond the organisation, even without any overarching strategic objective that was ex-ante shared by all (Weick 1999; Greenwood et al. 2002; Weik 2011). Thus, if well-targeted communicative efforts are effective in legitimising interdisciplinary scripts in broader parts of the collegiate, we conclude that they can have a broader and more lasting effect on attitudes towards interdisciplinary research—and the emergence of relevant de facto projects.

In practice, both the convening of researchers and the legitimation of interdisciplinary scripts are complementary and can be deployed simultaneously. The differences in the nature of their effects, however, suggests that—beyond the more fundamental, considerations above—the urgency of societal challenge may be a relevant factor in making choices. Specifically, a perception of urgency may create a need for quicker action and the deployment of measures likely to achieve this. Undoubtedly, urgency is in itself socially constructed (Wexler 2009) as evidenced, for example, by the case of infection control before and during the SARS-COV-2 pandemic (van Woezik 2016), or even climate change, which had been neglected for decades before it became topical across the board (Dentoni and Bitzer 2015). Nonetheless, it is a clearly identifiable characteristic of all problems at any given point in time, and de facto lowers funders' and regulators' tolerance to wait for universities' self-organisation capacities to eventually emerge. More urgent problems require quick reactions, which makes the indirect, communicative legitimation of scripts unsuitable in the short run so that recourse will have to be taken to intensify convention. At the same time, the convening of researchers will continue to remain short-lived with regard to impact, and is limited in scope. Thus, communicative legitimation will remain an essential parallel effort, even in the case of initial pressing challenges.

Discussion

As we have argued, it is in line with much of the extant literature that suggests that the best way to conceptualise universities is as organisations that constitute and reconstitute themselves in a dynamic equilibrium between multiple institutional fields (Hattke et al. 2016; Doyle and Brady 2018). Arguably, it is therefore less the "intensity of coupling" or "distinctiveness" (Orton and Weick 1990) but more the pre-existing diversity of a researcher’s exposure to institutional scripts that determines their propensity to develop change agency, and their susceptibility to university managers' initiatives. This understanding is consistent with the views of Mahoney and Thelen (2010) who conceive of organisational change as the result of agency, power, and institutional ambiguity opening up spaces for change.

As we have developed, the observable limits of collective change agency in university settings emerge not only from routinization and institutional rigidity that prevents individual change agency, but also from researchers' exposure to alternative institutional referents that enables it. While Orton and Weick's (1990) notion of adaptability to "signals" clearly implies that researchers’ responsiveness depends on a signal's source, the conceptual implications of this rather generic statement have so far not been fully elaborated. As such, we emphasise that it seems problematic that the literature on university governance has engaged in surprisingly little discussion on the fundamental principles based on which university managers can encourage and prompt individual researchers' inclination to activate their latent potential for change agency. This is particularly surprising, as there is a wealth of preceding discussions on this topic in sociology and organisation science (Dorado 2005; Weik 2011).

At a conceptual level, our model of a multi-level, embedded agency thus provides a fresh view on long-standing and established theories of university governance (Cohen et al. 1972; Weick 1976; Elken and Vukasovic 2019). It has enabled us to expand on two main forms of agency, beyond bureaucratic control, that university management can resort to when trying to promote interdisciplinary research addressing societal challenges. These were specifically to convene scientists around interdisciplinary research projects and to legitimise disciplinary research, and have been implicitly referred to in the literature (Blaschke et al. 2014; Blümel 2016; Doyle and Brady 2018), but so far have not yet been fully integrated in an overarching conceptual framework. Qualifying the sceptical views of earlier institutional approaches (Cohen et al. 1972; Weick 1976; Orton and Weick 1990), we were able to demonstrate that, conceptually, recourse to soft governance (Courpasson and Clegg 2012; Hales 2002) does not necessarily imply a loss of effectiveness.

With a view to the most suitable and precise approach, we differ from the proposition raised at times by organisational theorists that complex problems can only be suitably addressed by convention (Dorado 2005). Instead, we suggest that—in the long run—more lasting change may in fact only be possible through legitimation. One important additional argument in this regard is that only substantive changes in mind set at different levels of hierarchy will enable changes in future appointment procedures and thus ascertain a more structural transformation of the university in the long run. However, this does not necessarily contradict established findings in general organisational theory. First, the above statement on the paramount, even exclusive role of convention for changing routines was made in a context with a less pronounced focus on long-term institutionalisation than covered in this article (Dorado 2005). Second, it was made for a context in which there was no organisational frame like that of a university, through which managers can purposefully provide very defined group of actors with access to very specific institutional referents. We do not dispute that, absent such an organisational framework, convention might well be the only solution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the agency-based view proposed here suggests that universities need to strengthen their internal capacity for legitimation and convening scientists around interdisciplinary research, by responding to complex challenges and their increasing reflection in so-called mission-oriented policies. We maintain that any contribution towards solving large and complex societal problems will invariably require some active engagement by university management, not necessarily in the research process itself. In light of extended political expectations placed on universities, becoming active agents of internal concertation will become crucial for university managers, not least because of the shifting focus of funding organisations.

That said, we acknowledge that many relevant academic problems will continue to be solved in decentralised disciplinary community networks, and that researchers' effectively doing so is the foundation of all complementary endeavours. Hence, we emphasise that decision makers should ideally seek to ensure a reorientation towards interdisciplinary initiatives, not in a top-down manner but by providing access to attractive alternative institutional referents that researchers themselves would be interested in engaging with. While it is desirable to see specific research groups and universities become more responsive to external referents that originate from the policy domain, they should not lose their capacity to develop scientific contributions in substance. Since not all relevant problems are complex and interdisciplinary in nature, establishing new institutional referents that work against existing ones could reduce researchers' capabilities of dealing with other, equally relevant issues, even if this happens through extensive and repeated convention.

Hence, we conclude that even within the domain of soft governance, university management should take an enabling and communication-oriented rather than overly proactive approach, and make the best possible use of their role as ‘translating interfaces’, with the ability to convey new institutional referents from the domain of external to that of internal governance. In line with the paper’s main tenet, we continue to maintain that lasting change can hardly be brought about without individual scientists’ voluntary, creative contributions, even if this process may be more directed and lengthier. Instead of combatting disciplinary practices, even if discursively, it can exploit and augment pre-existing institutional ambiguities in and between scientific communities by legitimising interdisciplinary problem-solving scripts, and thereby widening each individual researcher’s room for agency.

To what extent universities are ready for such an empowering approach, however, will depend on the status quo ante, an aspect less fully explored in this paper. Where researchers are deeply embedded in dominant disciplinary networks and pressing problems, a mere enabling approach may not suffice. Hence, final conclusions on best governance options can only be drawn if the status quo ante, with regard to researchers' exposure and means of access to alternative institutional scripts, is known for a specific organisation. Further research on this will be required in both the conceptual and the empirical domain.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding for this research received from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under grant number 01PH20010 (StratGov). Also, they acknowledge valuable perspectives offered by two anonymous reviewers.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to be reported.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdelnour S, Hasselbladh H, Kallinikos J. Agency and Institutions in Organization Studies. Organization Studies. 2017;38(12):1775–1792. doi: 10.1177/0170840617708007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. Mapping Academic Resistance in the Managerial University. Organization. 2008;15(2):251–270. doi: 10.1177/1350508407086583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barley, S.R. (1997) ‘Institutionalization and Structuration: Studying the Links Between Action and Institution’, Organization Studies.

- Barley SR, Tolbert PS. Institutionalization and Structuration: Studying the Links between Action and Institution. Organization Studies. 1997;18(1):93–117. doi: 10.1177/017084069701800106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J. and D'Aunno, T. (2009) ‘Institutional Work and the Paradox of Embedded Agency’, in Institutional Work, Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009.

- Beckert, J. (1999) ‘Agency, Entrepreneurs, and Institutional Change: The Role of Strategic Choice and Institutionalized Practices in Organizations’, Organization Studies.

- Blaschke S, Frost J, Hattke F. Towards a Micro foundation of leadership, governance, and management in universities. Higher Education. 2014;68(5):711–732. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9740-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaug, M. (1976) ‘The empirical status of human capital theory: A slightly jaundiced survey’, Journal of economic literature.

- Bleiklie I. Organization and Governance of Universities. Higher Education Policy. 2007;20(4):477–493. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleiklie I, Michelsen S. Comparing HE policies in Europe. Higher Education. 2013;65(1):113–133. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9584-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleiklie I, Enders J, Lepori B, editors. Managing Universities: Policy and Organizational Change from a Western European Comparative Perspective. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bleiklie, I., Enders, J. and Lepori, B. (2015) ‘Organizations as Penetrated Hierarchies: Environmental Pressures and Control in Professional Organizations’, Organization Studies.

- Blümel A. (De)constructing organizational boundaries of university administrations: changing profiles of administrative leadership at German universities. European Journal of Higher Education. 2016;6(2):89–110. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2015.1130103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boitier M, Rivière A. Changing Professions? The Professionalization of Management in Universities. In: Frost J, Hattke F, Reihlen M, editors. Multi-Level Governance in Universities. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bolden R, Petrov G, Gosling J. Tensions in Higher Education Leadership: Towards a Multi-Level Model of Leadership Practice. Higher Education Quarterly. 2008;62(4):358–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00398.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boon W, Edler J. Demand, challenges, and innovation. Making sense of new trends in innovation policy. Science and Public Policy. 2018;45(4):435–447. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scy014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrás, S. and Edler, J. (2020) ‘The Roles of the State in the Governance of Socio-Technical Systems' Transformation’, Research policy.

- Boschma R. Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment. Regional Studies. 2005;39(1):61–74. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Homo academicus. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale, I. (2018) ‘Beyond Constraining and Enabling: Toward New Microfoundations for Institutional Theory’, The Academy of Management review.

- Cohen, M.D., March, J.G. and Olsen, J.P. (1972) ‘A garbage can model of organizational choice’, Administrative science quarterly.

- Courpasson, D. and Clegg, S. (2012) ‘The Polyarchic Bureaucracy: Cooperative Resistance in the Workplace and the Construction of a New Political Structure of Organizations’, in D. Courpasson, D. Golsorkhi and J.J. Sallaz (eds.) Rethinking Power in Organizations, Institutions, and Markets, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 55–79.

- Dentoni D, Bitzer V. The role(s) of universities in dealing with global wicked problems through multi-stakeholder initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2015;106:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review. 1983;48(2):147. doi: 10.2307/2095101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donina D, Seeber M, Paleari S. Inconsistencies in the Governance of Interdisciplinarity: the Case of the Italian Higher Education System. Science and Public Policy. 2017;44(6):865–875. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scx019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorado S. Institutional Entrepreneurship, Partaking, and Convening. Organization Studies. 2005;26(3):385–414. doi: 10.1177/0170840605050873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle T, Brady M. Reframing the university as an emergent organisation: implications for strategic management and leadership in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 2018;40(4):305–320. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2018.1478608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elken, M. and Vukasovic, M. (2019) ‘The Looseness of Loose Coupling: The Use and Misuse of “Loose Coupling” in Higher Education Research’, in Theory and Method in Higher Education Research, Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 53–71.

- Emirbayer M, Mische A. What Is Agency? American Journal of Sociology. 1998;103(4):962–1023. doi: 10.1086/231294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engwall L. Structural Conditions for Interdisciplinarity. European Review. 2018;26(S2):S30–S40. doi: 10.1017/S106279871800025X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fam D, Clarke E, Freeth R, Derwort P, Klaniecki K, Kater-Wettstädt L, Juarez-Bourke S, Hilser S, Peukert D, Meyer E, Horcea-Milcu A-I. Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research and practice: Balancing expectations of the ‘old’ academy with the future model of universities as ‘problem solvers’. Higher Education Quarterly. 2020;74(1):19–34. doi: 10.1111/hequ.12225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fini, R., Perkmann, M. and Ross, J.-M. (2021) Attention to Exploration: The Effect of Academic Entrepreneurship on the Production of Scientific Knowledge, S.l.: SSRN.

- Frost J, Hattke F, Reihlen M, editors. Multi-Level Governance in Universities. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons M. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London: SAGE Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge Cambridgeshire: Polity Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood R, Hinings CR, Suddaby R. Theorizing Change: The Role of Professional Associations in the Transformation of Institutionalized Fields. Academy of Management Journal. 2002;45(1):58–80. doi: 10.2307/3069285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hales C. 'Bureaucracy-lite' and Continuities in Managerial Work. British Journal of Management. 2002;13(1):51–66. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.00222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon J, Hocking C, Legge K, Lugg A. Sustaining interdisciplinary education: developing boundary crossing governance. Higher Education Research & Development. 2018;37(7):1424–1438. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2018.1484706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanefendic, S. and Donina, D. (2022) ‘A heuristic perspective on organizational strategizing in complex and coherent higher education fields’, Tertiary Education and Management.

- Hattke F, Vogel R, Woiwode H. When Professional and Organizational Logics Collide: Balancing Invisible and Visible Colleges in Institutional Complexity. In: Frost J, Hattke F, Reihlen M, editors. Multi-Level Governance in Universities. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Head BW, Alford J. Wicked Problems. Administration & Society. 2015;47(6):711–739. doi: 10.1177/0095399713481601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Head, B.W. (2022) Wicked Problems in Public Policy: Understanding and Responding to Complex Challenges, Cham: Springer Nature.

- Horta H. Academic Inbreeding: Academic Oligarchy, Effects, and Barriers to Change. Minerva. 2022;60(4):593–613. doi: 10.1007/s11024-022-09469-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hüther O, Krücken G. Hierarchy and power: a conceptual analysis with particular reference to new public management reforms in German universities. European Journal of Higher Education. 2013;3(4):307–323. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2013.850920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hüther O, Krücken G. German Higher Education Institutions as Organizations. In: Hüther O, Krücken G, editors. Higher Education in Germany—Recent Developments in an International Perspective. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. pp. 133–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmützky, A. (2016) ‘Mission Statements and the Transformation of German Universities into Organizational Actors’, Recherches sociologiques et anthropologiques.

- Krücken, G. and Meier, F. (2006) ‘Turning the University into an Organizational Actor’, in Globalization and Organization, Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press, 2006.

- Leca, B., Battilana, J. and Boxenbaum, E. (2009) ‘Agency and Institutions: A Review on Institutional Entrepreneurship’.

- Leiber T. On Innovative Governance of Higher Education Institutions: Quality Literacy. Performance Indicators and a Focus on Learning and Teaching: Unpublished; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leišytė L, Rose A-L, Sterk-Zeeman N. Higher education policies and interdisciplinarity in Germany. Tertiary Education and Management. 2022;28(4):353–370. doi: 10.1007/s11233-022-09110-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liefner I. Funding, resource allocation, and performance in higher education systems. Higher Education. 2003;46(4):469–489. doi: 10.1023/A:1027381906977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lok J, Willmott H. Embedded Agency in Institutional Theory: Problem or Paradox? Academy of Management Review. 2019;44(2):470–473. doi: 10.5465/amr.2017.0571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbury, M. and Crumley, E.T. (2007) ‘New Practice Creation: an Institutional Perspective on Innovation’, Organization Studies.

- Lyall C, Meagher LR. A Masterclass in interdisciplinarity: Research into practice in training the next generation of interdisciplinary researchers. Futures. 2012;44(6):608–617. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2012.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J, Thelen KA, editors. Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marchant GE. ‘Governance of Emerging Technologies as a Wicked Problem’. Vanderbilt Law Review. 2020;1873(73):1861–1877. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, F. (2009) Die Universität als Akteur: Zum institutionellen Wandel der Hochschulorganisation, Zugl.: Bielefeld, Univ., Diss, 2008, Wiesbaden: VS Verl. für Sozialwiss.

- Mintzberg H. The Structuring of Organizations: A Synthesis of the Research. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K., van Buren, H.J., Greenwood, M. and Freeman, R.E. (2015) ‘Stakeholder Inclusion and Accounting for Stakeholders’, Journal of management studies.

- Musselin, C. (2021) University Governance in Meso and Macro Perspectives, S.l.: SSRN.

- Nowotny H, Scott P, Gibbons M. Re-Thinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C. Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes. Academy of Management Review. 1991;16(1):145. doi: 10.2307/258610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boer, H. de, Enders, J. and Schimank, U. (eds.) On the way towards new public management? The governance of university systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany, Netherlands: Springer International Publishing, pp. 137-152.

- Orton JD, Weick KE. Loosely Coupled Systems: A Reconceptualization. Academy of Management Review. 1990;15(2):203. doi: 10.2307/258154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.J. and Webber, M.M. (1973) ‘Dilemmas in a general theory of planning’, Policy sciences.

- Seeber M, Lepori B, Montauti M, Enders J, de Boer H, Weyer E, Bleiklie I, Hope K, Michelsen S, Nyhagen GM, Frølich N, Scordato L, Stensaker B, Waagene E, Dragsic Z, Kretek P, Krücken G, Magalhães A, Ribeiro FM, Sousa S, Veiga A, Santiago R, Marini G, Reale E. ‘European Universities as Complete Organizations?: Understanding Identity. Public management review: Hierarchy and Rationality in Public Organizations’; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seo M-G, Creed WED. Institutional Contradictions, Praxis, and Institutional Change: A Dialectical Perspective. Academy of Management Review. 2002;27(2):222. doi: 10.2307/4134353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stichweh R. The Sociology of Scientific Disciplines: On the Genesis and Stability of the Disciplinary Structure of Modern Science. Science in Context. 1992;5(1):3–15. doi: 10.1017/S0269889700001071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Välikangas, L. and Lewin, A.Y. (2022) ‘The Point Is… the Ingenuity of Resilience Escapes Capture’, European management review.

- van Woezik AFG. Tackling Wicked Problems in Infection Prevention and Control: a Guideline for Co-Creation with Stakeholders. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 2016;5(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0119-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereijken, M.W.C., Akkerman, S.F., te Pas, S.F., van der Tuin, I. and Kluijtmans, M. (2022) ‘‘Undisciplining’ higher education without losing disciplines: furthering transformative potential for students’, Higher Education Research & Development: 1–14.

- Weick KE. Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1976;21(1):1. doi: 10.2307/2391875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE. Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. (1999) ‘Sensemaking as an Organizational Dimension of Global Change’, in D. Cooperrider and J. Dutton (eds.) Organizational Dimensions of Global Change: No Limits to Cooperation, 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States: SAGE Publications, Inc, pp. 39–56.

- Weiherl J, Frost J. Professional and Organizational Commitment in Universities: from Judgmental to Developmental Performance Management. In: Frost J, Hattke F, Reihlen M, editors. Multi-Level Governance in Universities. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Weik E. Institutional Entrepreneurship and Agency. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 2011;41(4):466–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2011.00467.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler MN. Exploring the moral dimension of wicked problems *. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 2009;29(9/10):531–542. doi: 10.1108/01443330910986306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, R. (2008) Construction Universities as Strategic Actors: Limitations and Variations, Manchester: Manchester Business School.

- Wickson F, Carew A, Russell AW. Transdisciplinary research: characteristics, quandaries and quality. Futures. 2006;38(9):1046–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2006.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woiwode, H., Frost, J. and Hattke, F. (2017) ‘Hochschulleitungen zwischen Repräsentation und Ergebnisorientierung: Handlungs(un)fähigkeiten und Vermittlungstaktiken = University boards between representation and outcome orientation: (In-)abilities to act and mediation tactics’, Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis.