ABSTRACT

The history of vocational interests shows that these measures have great promise for use in job assignment, suggesting that individuals will be more satisfied and successful in their job when they are doing work that interests them. Recent research has provided empirical support for these predictions and demonstrated that the match between an individual’s interests and his or her work activities is positively related to job performance and negatively related to attrition. Building on these positive empirical findings, the U.S. Army Research Institute is investigating vocational interest measures for personnel job assignment. Person-job fit is very important in a context such as the U.S. Army, where applicants have over 140 military occupational specialties from which to choose. This paper begins by reviewing evidence for the validity of interests and discussing how vocational interest measures may be used for assigning Soldiers in a military context followed by our recent research to develop a new measure of vocational interests to improve the process of matching Soldiers to military occupational specialties. We will conclude with the next steps for this research and potential paths of implementation.

KEYWORDS: Interest assessment, occupational interests, vocational interests, job assignment

What is the public significance of this article?—An organization’s effectiveness is based on the people who comprise it. Thus, selection and placement of personnel directly impact that effectiveness. Historically, cognitive testing has been the dominant tool for these purposes. However, cognitive tests have been shown to be limited in predicting elements of success beyond technical proficiency. They do not predict well those aspects of performance which depend on the individual’s motivation to perform well over time, or to remain with the organization over time. For these outcomes, noncognitive attributes such as personality and vocational interests provide critical predictive information. This special issue demonstrates the effectiveness of personality and interest measures in a military context, and how these tools are transforming the military selection and classification process. The effort reported in this issue marks major changes in the selection and classification process, changes that can help both military and civilian organizations be more productive and successful.

Extensive research has gone into the antecedents of job performance and turnover. Organizations want to know how to select the right people and get them into the right positions, resulting in productive long-term workers. There are several factors that influence employees’ job choice, performance, and ultimately whether they stay at or leave an organization. Non-cognitive attributes such as personality have taken on a greater significance in job assignment research; however, vocational interests have been notably absent from many reviews (Van Iddekinge, Putka, & Campbell, 2011). Vocational interests have been shown to be relevant to employee satisfaction and retention and ignoring their impact is detrimental to the holistic approach to job assignment decisions (Nye, Butt, Bradburn, & Prasad, 2018). This paper will focus on the validity of vocational interests and discuss the development of a new measure of vocational interests for use in the U.S. Army.

Vocational interests

Vocational interests have been an area of study for nearly 100 years; however, they are often used for coaching or personal development rather than a job assignment context. Vocational interests represent the type of work that employees want to do. Some of the defining features of vocational interests are that they are individual characteristics that are fairly stable over time (Low, Yoon, Roberts, & Rounds, 2005) and have a direct effect on job choices and behavior at work (Nye, Su, Rounds, & Drasgow, 2012, 2017; Van Iddekinge, Putka, et al., 2011). In addition, the effects of interests can be differentiated from other predictors of work behavior such as personality and cognitive ability (Van Iddekinge, Putka, et al., 2011). All three of these components are important for the assignment of employees but they exert their influence in different ways. In many ways personality works as the foundation for making choices or motivation to perform a behavior, whereas interests are more explicit preferences or driving factors. For example, personality traits may predispose someone to be motivated to perform well in a training environment (Ingerick & Rumsey, 2014). However, if the learner finds the material interesting, he or she is much more likely to be engaged and perform better in the training.

Vocational interests and performance

There are several theoretical perspectives on the relationship of vocational interests to job performance and turnover. One of the areas that has been investigated consistently for several decades is person-environment (P-E) fit which states that when there is a match between the employee and the job, the employee will be more likely to stay in the position and be satisfied and successful in it. Alternatively, when there is a mismatch between the employee and the job there is a greater chance of attrition, job dissatisfaction, and lower performance (Kristof‐Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005).

Several meta-analyses have been conducted to examine the relationship between vocational interests and organizational outcomes. Van Iddekinge, Roth, Putka, and Lanivich (2011) found that vocational interests were related to job and training performance, as well as turnover intentions and actual turnover. These researchers also suggested that multidimensional interest scales are more useful for predicting outcomes. Nye et al. (2012) further supported the moderate relationship between interests and performance and found that this relationship was stronger when congruence scores were used. When the interests of the employee matched the characteristics of the job (i.e., were congruent, as defined by Holland, 1959), there was a stronger relationship between interests and performance. These congruence indices were also related to organizational citizenship behaviors and persistence.

Vocational interests have shown promise for use in the military context. The US military began looking at vocational interests as far back as World War II, although the early research was less systematic than later projects. The U.S. Air Force’s Vocational Interest Career Examination (VOICE) instrument and its adaptation by the Army, the Army Vocational Interest Career Examination (AVOICE), both of which are discussed later, showed promise for predicting military outcomes. The VOICE was related to job satisfaction for early career Airmen (Alley & Matthews, 1982) and the AVOICE was related to task performance for Soldiers (Hanson, Paullin, Bruskiewicz, & White, 2003), but ultimately neither measure was adopted for wider use. The most recent Army interest assessment, the Work Preferences Assessment (WPA), also showed promising results for predicting Soldier performance. The WPA showed incremental validity over cognitive ability and personality in predicting technical knowledge, interpersonal knowledge, task proficiency, effort, and continuance intentions (Van Iddekinge et al., 2011). Building on these positive empirical findings, the U.S. Army Research Institute (ARI) is investigating a new vocational interest measure for personnel job assignment, incorporating recent advances in technology and theory.

The role of vocational interests in the U.S. Army

In the U.S. Army, there is ongoing research investigating the question of how to get people to stay in service. The Army, or any military service, is unlike most careers in that it is not only a job but a way of life. First, Soldiers perform their specific job duties during working hours but they are “on duty” 24/7 as members of the U.S. Army. This means that everything they do, even when they are not performing their work duties, can affect their Army career. Second, Soldiers generally have to change locations every few years as part of their assignments. This can cause stress on Soldiers and their families and can be an obstacle to retention. Third, Soldiers have to meet specific physical requirements to stay in the Army. There are not many other jobs that have this type of requirement. Finally, Soldiers have to be ready to deploy at any time. While the likelihood of deployment varies greatly by job type and other factors, Soldiers are expected to always be ready to deploy if the need arises, which can be an additional stress factor. Given all of these factors specific to the military, the assignment process can be more complex than in civilian organizations.

The factors listed above are obstacles for all Army jobs, or military occupational specialties (MOS). Therefore, when trying to optimize the assignment process we must focus on the areas we can influence, which is where vocational interests come into play. P-E fit theory suggests that Soldiers entering their best-fitting MOS when enlisting have a greater likelihood of staying in the Army and being satisfied with and successful in their MOS. However, due to the complicated nature of the accession process, it is difficult to find opportunities to influence an applicant’s MOS choice. Because of the cost and time devoted to training and attrition, it is in the best interest of the Army and Soldiers to get applicants into the best-fitting MOS right from the start. While there are several paths into the Army, we will briefly describe one of the most common paths for joining.

In this scenario, a potential applicant has already graduated high school and will now meet with an Army recruiter to begin the process of applying. When the applicant meets with the recruiter, he or she will take a practice test that simulates the scores he or she will receive on the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), which is composed of the math and verbal sections of the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). This will let the recruiter know if the applicant is likely to be eligible for enlistment and for which MOS the applicant may qualify. If everything looks good at this stage, the recruiter will set up an appointment for the applicant at a Military Entrance Processing (MEPS) station for official testing. After the testing is complete and all scores are processed, the applicant will sit with a job classifier and find out which MOS he or she can choose from. Currently there are approximately 140 entry level MOS in the Army; however, it is extremely unlikely that an applicant would have the option to choose from all 140 MOS. The available MOS shown to the applicant depend on a variety of factors, including test scores, the number of training seats at the time, and Army need. While the applicant is not given the full range of MOS to choose from, there are generally a variety presented. Often the only information the applicant has about the MOS is information from the recruiter or job classifier and a short “propensity” video shown by the job classifier. The applicant is expected to choose an MOS at this time and then sign the contract to join to Army. Once this is complete the applicant returns home and comes back to the MEPS only when it is time to ship off to basic training.

In addition to the institutional factors determining the applicant’s available pool of MOS, the applicant’s personal choice of MOS is also a factor. ARI data shows that half of applicants had some idea what MOS they wanted before they met with a recruiter (Kirkendall, 2017). They based their choice on a variety of factors, but most of the applicants’ decisions were influenced by the assumption that the MOS would be a good fit for them. When applicants went into the process without having an MOS in mind, or if they did not get the MOS they originally wanted, their perceived fit between themselves and the MOS was again the number one reason for choosing their entry MOS. With this information in mind, we can see how perceived P-E fit plays a role in guiding the applicants’ job choices and shapes their Army career. The introduction of vocational interests into this process will be an additional tool to provide applicants with more information about P-E fit and help guide them to MOS in which they will be most successful.

Development of the adaptive vocational interest diagnostic (AVID)

Although there are some existing measures of vocational interests in the Army, which were mentioned earlier, these traditional measures have several limitations. First, existing scales were not constructed to measure well across all levels of the interest dimensions. Because classical test theory methods were used to evaluate and choose items during the scale development process, only items having a positive standing on the underlying dimension (after reverse scoring those that were negatively worded) were retained; neutral items were discarded due to low item-total correlations (Chernyshenko, Stark, Drasgow, & Roberts, 2007; Stark, Chernyshenko, & Drasgow, 2005; Stark, Chernyshenko, Drasgow, & Williams, 2006). This affects the rank-order of high and low scoring individuals who are often of primary interest in selection and assignment contexts. Second, traditional paper and pencil interest measures are inefficient and cumbersome to administer and maintain. They have rigid administration prescriptions in the sense that all items must be administered to every individual in a pre-specified order. This increases testing time and decreases test security through repeated item exposure.

Finally, in high stakes testing situations, single-statement, Likert-type items can be easily faked; i.e., test takers can discern the correct or socially desirable answers and, thus, increase or decrease their scores. For example, intentional distortion has been found to undermine the utility of personality measures for personnel selection and assignment (White & Young, 1998). In addition, past research has indicated that individuals can inflate their scores on an interest assessment when instructed to do so (Abrahams, Neumann, & Githens, 1970; Garry, 1953). Although “faking good” is a concern with personality assessments, faking in vocational interest assessments can take a different form. Here, the concern is that individuals will distort their responses to get into a specific job that they may or may not be interested in. There are many potential reasons why an individual may select a particular job (e.g., family considerations, financial incentives, prestige) that may not be related to interests (Nye, Perlus, & Rounds, 2018). However, despite the importance of these decision factors to the individual, the link between interests and performance suggests that faking to get into a job that an individual is not interested in could undermine the validity of the assignment process. Therefore, the issue of faking needs to be addressed for high-stakes interest assessments.

Due to the limitations of previous measures, a new generation of interest assessments is needed to help facilitate the assignment of Soldiers in the U.S. Army. The AVID is being developed to 1) assess both global and narrow interest factors, 2) be fake-resistant, 3) utilize computer adaptive testing (CAT) technology to measure accurately and efficiently across a broad range of interest dimensions, and 4) use a forced-choice response format to overcome response set problems and meet the assessment needs of the Army. To develop the AVID, the Army initiated a comprehensive project to develop and evaluate this assessment for use with incoming Soldiers. This ongoing project will involve identifying the most important dimensions of vocational interest for Soldier assignment, developing and pretesting initial statement pools to assess these dimensions, refining the pools, and collecting preliminary validity evidence for an initial version of AVID. The purpose of the present study is to describe the first step of this process and identify important dimensions of interest for assessment.

The most popular and widely used structure of vocational interests was proposed by Holland (1997) who suggested that interests could be divided into six primary interest types that he labeled Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional interests. In this conceptualization, people with Realistic interests like working with things, gadgets, and in the outdoors; people with Investigative interests enjoy the sciences; Artistic individuals like to express themselves creatively through writing or the visual and performing arts; Social individuals enjoy working with people; Enterprising individuals like tasks that involve leadership, persuasion, and the pursuit of economic gain; and people with Conventional interests enjoy working in well-structured environments, like certain business settings (Nye et al., 2012). Collectively, these six types are known by their acronym as the RIASEC model.

Measures of the RIASEC interest types are designed to assess a wide range of activities that reflect broad occupational themes. Although these dimensions have demonstrated validity for predicting performance on the job (e.g., Nye et al., 2012), they may be too broad and may lack the precision necessary to differentiate individual interests in many occupations. As a result, some have suggested that basic interests may provide a better representation of contemporary jobs (Day & Rounds, 1997). Basic interests are more homogeneous dimensions of interest that group together work activities and may be relevant to a number of occupations. These narrower interest dimensions are analogous to trait facets in personality research. Just as personality facets are generally grouped together under the Big Five factors, each of the RIASEC dimensions may also be represented by several narrow basic interests. As a result, assessing basic interests can provide both the content specificity and the flexibility required to more accurately assign Soldiers into an MOS.

The present study

Despite the potential advantages of basic interests for Soldier assignment, a comprehensive set of basic interests that are relevant to military occupations has not yet been identified in the literature. Therefore, the present study used two approaches to identify the basic interests that may be useful in the Army. First, we re-examined data from the AVOICE collected during Project A to identify the structure of basic interests that may be of particular relevance in military settings. As discussed earlier, The AVOICE was an adapted version of the VOICE that was designed to more fully represent Holland’s RIASEC model. Details about the development of the AVOICE and its scales can be found in Hough, Barge, and Kamp (2001). For the second approach, we conducted a review of existing interest measures to identify additional basic interests that may not have been included in the AVOICE but yet may still be useful for assignment.

Using these two approaches, we were able to identify a more comprehensive list of basic interest dimensions for development. Below we describe these approaches in more detail and discuss our findings regarding potentially useful basic interest dimensions for the Army.

Methods

We first analyzed existing AVOICE data from the Army’s Project A Longitudinal Validation (LV), which was a research program designed to evaluate Army accessions screening tests including ASVAB and new selection and assignment measures (Campbell, 1990). The data for these analyses consisted of 45,002 responses to the 182 interest items assessed in the AVOICE. These data were analyzed using Goldberg’s (2006) proposed method for exploring the hierarchical structure of a set of personality variables. With this approach, exploratory factor analyses are used to extract successively higher numbers of factors. First one factor is extracted, then two factors, three factors, and so forth until none of the items have their highest loading on each new factor that is extracted.

For our analyses, we used principal axis factoring with varimax rotation. With this method of extraction, each factor maximizes the amount of variance accounted for in the items. So, for example, the first factor accounts for the most variance in the items. The second factor extracted is the factor that accounts for the highest proportion of the remaining variance after accounting for the first factor. The last factor extracted in each set of analyses accounts for the least amount of variance in the items. Therefore, the order of extraction is informative. Goldberg (2006) also suggested examining the correlations between the factor scores for each successive model. These correlations illustrate the relationships between the factors at each stage of the analyses and help to demonstrate the hierarchical structure of the data.

Next, we also conducted a literature review to identify potentially important basic interest factors that might not be represented well in the AVOICE. After identifying the list of basic interest dimensions that have been assessed in the literature, we examined the definitions and, where possible, the content of the scales to determine their relevance for Army MOS. Although a particular dimension may be useful for differentiating civilian jobs, it may not be particularly relevant for Army occupations. In other words, not all basic interest dimensions in the literature were selected for assessment with the AVID. Instead, the purpose of this literature review was to identify a broader range of potential basic interest dimensions that could be further refined in a measure developed to enhance assignment decisions in the U.S. Army.

Results

AVOICE hierarchical analyses

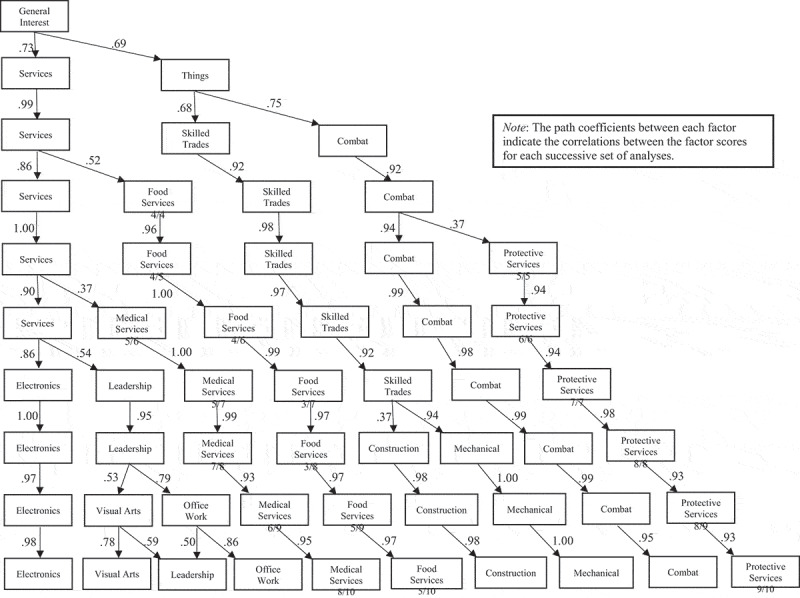

The results of the hierarchical analyses of the AVOICE data are shown in Figure 1. Again, the “path coefficients” between each factor indicate the correlations between the factor scores for each successive set of analyses. Based on these results, it appears that the 22 AVOICE scales assessed 10 basic interest dimensions. These dimensions are illustrated in the bottom row of Figure 1. The labels for these dimensions were selected based on the content of each factor and representative items are provided in Table 1. Several of the basic interests assessed by the AVOICE are lower-order dimensions of the Realistic interest type (i.e., Electronics, Construction, Mechanical, Combat, Protective Services) described in Holland’s (1959, 1997) RIASEC model. Many military jobs include Realistic activities and, therefore, it is not surprising that these interests would be represented well in the AVOICE.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical structure of the AVOICE.

Table 1.

Example items for the 10 basic interest dimensions assessed in the AVOICE.

| AVOICE Basic Interests | Representative Items for Each Basic Interest (factor loadings in parentheses) |

|---|---|

| Combat | Use cover, concealment, or camouflage (.62) Zero in a tank’s main gun (.57) Identify a target and adjust a cannon’s firing to hit it (.61) Collect rifles and pistols (.73) |

| Electronics | Technician (Electronics) (.65) Perform maintenance on a computer (.65) Design a circuit board (.66) Read about electronics (.61) |

| Office Work | Make out invoices (.60) Check a list of supplies received against those ordered (.65) Help prepare the payroll for a business (.61) Efficient methods for filing and retrieving office records (.61) |

| Mechanical | How different types of engines work (.71) Adjust a carburetor (.81) Rebuild or overhaul an engine (.80) Tune-up a car (.81) |

| Food Services | Wash, peel, dice vegetables (.60) Clear tables in a restaurant (.64) Serve food in a cafeteria (.75) Work as a short-order cook (.73) |

| Leadership | Inspire others with a speech (.61) Organize and lead a study group (.61) Mold a group of co-workers into an efficient team (.56) Teach someone how to solve a problem (.60) |

| Construction | Pour concrete for highway construction (.62) Construction worker (.61) Work with a hammer, trowel, or other hand tools (.56) Carpenter (.53) |

| Medical Services | Take blood samples from people (.74) Give injections to people for immunizations (.73) Perform emergency medical operations (.64) Assist a surgeon during an operation (.66) |

| Protective Services | Highway patrol officer (.71) Arrest a traffic violator (.63) Police officer (.75) Prison guard (.64) |

| Visual Arts | Photographer (.50) Television camera operator (.47) Operate a movie camera (.44) Record the sound for a motion picture (.41) |

Note. The AVOICE includes different sections that ask respondents to indicate how much they like various jobs, work tasks, spare time activities, or learning experiences, respectively. The example items presented above are taken from each of these sections and, therefore, the question stem differed slightly for some of these questions.

Review of existing basic interest measures

Given the 10 dimensions assessed by the AVOICE, we next conducted the literature review to determine what basic interest dimensions, if any, were not represented well by this measure. Our review identified 26 different interest measures (including the AVOICE) that included 214 basic interest scales. However, there was also significant overlap among many of these scales. Therefore, we categorized the 214 scales into a reduced set of basic interest dimensions. To do so, two experts on the assessment of vocational interests examined any available descriptions provided for each scale (i.e., either from empirical studies or technical reports) and created a rational categorization based on their perceived content similarities. The dimensions that resulted from this categorization are described in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 describes the basic interest dimensions that were identified as most useful for Army assignment and that can be developed using the proposed framework for the AVID. Table 3 provides some additional basic interest dimensions that we identified in our review but that may be less relevant for the Army.

Table 2.

Potential AVID dimensions identified in the literature review.

| Basic Interests | Activities Associated with Each Dimension |

|---|---|

| RIASEC dimension: Realistic | |

| Construction | Designing and/or building things or maintaining structures with one’s hands or using tools and materials. Includes jobs like construction worker, mason, or welder. |

| Protection | Guarding, ensuring safety, and enforcing rules and laws. Includes jobs like law enforcement officer, park ranger, firefighter, or in leadership and management positions in protective service organizations. |

| Combat | Operating weapons and equipment in ground combat operations; performing reconnaissance operations; attacking enemy positions and defending friendly posts. Includes jobs in infantry, field artillery, and special forces. |

| Physical Activity | Engaging in physical activity, exercise, sports, and games. Includes jobs like physical trainer, athletic coach, or strength training coach. |

| Mechanical | Building, maintaining, repairing and using small and large machinery, including driving and operating heavy equipment or large vehicles. Includes jobs like mechanic, service repair person, mechanical engineer, factory or laboratory machinist, pilot, boat captain, and truck driver. |

| Electronics | Building, maintaining, repairing and using electronics including computer hardware and small electronics. Includes jobs like electrician, broadcast technician, electronic equipment installer and repair person, and electrical engineer. |

| Outdoor | Working in the outdoors. Includes jobs like farmer, forest ranger, veterinarian, zoologist, landscaper, and groundskeeper. |

| RIASEC dimension: Investigative | |

| Medical Services | Applying medical knowledge and skills to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of disease and injury. Includes jobs like paramedic, physician’s assistant, nurse, physical therapist, and dental hygienist. |

| Mathematics | Working with data and applying quantitative and statistical concepts and mathematical formulas. Includes jobs like statistician, mathematician, engineer, or financial analyst. |

| Science | Involves scientific activities such as studying biology, astronomy, geology, and physics; reading books about science; and doing scientific research or related activities. Includes jobs like scientist and laboratory worker or technology and medical paraprofessional. Also includes jobs in health, nutritional or pharmaceutical services involving scientific interests. |

| Information Technology | Developing, maintaining, and using computer systems, software, and networks for the processing and distribution of data. Includes jobs like computer systems analyst, network administrator, software developer, web administrator, and database administrator. |

| RIASEC dimension: Artistic | |

| Writing | Writing in detail factual reports, memos, textbooks, scientific, legal, historical or technical essays for business and record-keeping purposes. This interest may be satisfied by a number of jobs that involve significant writing tasks. |

| RIASEC dimension: Social | |

| Teaching | Instructing people inside and outside of school (e.g., teachers and instructors in school, churches, clinics, and welfare agencies). May also include training, coaching athletics, or providing child care. |

| Personal Service | Performing everyday tasks for others (e.g., household worker; hospitality services in airplanes, and hotels; or hair and beauty services, etc.). |

| RIASEC dimension: Enterprising | |

| Management | Leading others and influencing people and decisions. Includes administrative or supervisory positions, such as a shop foreman, supervisor, school administrator, police or fire chief, head librarian, executive, hotel manager, or union official. Also includes owning or managing a store or business. |

| Sales | Includes activities that involve selling products and services. Includes jobs that require selling products or services in stores, offices, or customers’ homes such as auto sales, insurance, lobbying, public relations, or real estate. |

| Human Relations | Arranging positive interpersonal interactions for individuals. Includes jobs that involve setting company policies, acting as a mediator in a conflict, solving interpersonal situations, etc. |

| RIASEC dimension: Conventional | |

| Office Work | Performing clerical, administrative, and business related activities (recording, data processing, typing, filing, etc.). This interest may be satisfied by work as an office manager, bookkeeper, receptionist, secretary, or administrative assistant. |

| Finance | Managing assets and debt. Includes jobs that utilize numbers such as in business bookkeeping, accounting, and tax procedures. |

| Food Service | Involves activities related to food processing, cooking, planning menus, and related activities. Includes jobs like short-order cook, cafeteria worker, caterer, food service manager, or waiter/waitress. |

Table 3.

Additional basic interest dimensions (Less relevant for military contexts).

| Basic Interests | Activities Associated with Each Dimension |

|---|---|

| RIASEC dimension: Investigative | |

| Social Science | Research, development, and consulting activities relevant to human behavior and social organizations. Includes jobs like psychologist, historian, sociologist, or survey researcher. |

| RIASEC dimension: Artistic | |

| Creative Arts | Activities involving the visual arts or music. Includes jobs like interior designer, fashion designer, composer, or artist. |

| Performing Arts | Performing for an audience. Includes jobs like musician, actor, movie director, singer, or dancer. |

| RIASEC dimension: Social | |

| Social Service | Helping individuals and communities to cope with problems. Includes jobs like counselor, therapist, or social worker. |

| Family Activity | Performing domestic activities. May also include jobs related to such activities such as child care worker, nursery school teacher, or child development specialist. |

| Professional Counseling | Advising people in meeting their professional goals. This interest may be satisfied by a job as a career counselor. |

| Religious Activity | Leading spiritual groups or providing altruistic teachings. Primarily includes jobs like spiritual leader, chaplain, or counselor at a religious camp. |

| RIASEC dimension: Enterprising | |

| Business | Dealing with structured wholesale and retail activities. Includes jobs in marketing, advertising, insurance, or real estate. |

| Law | Researching, documenting, and debating legal matters. Includes jobs like lawyer, court reporter, paralegal, or politician. |

As shown in Table 2, a number of the scales that we identified in our review and that are relevant to the Army are lower-order dimensions of Holland’s (1997) Realistic interest type. In contrast, we only identified one lower-order dimension of Holland’s Artistic interest type that seemed relevant to the Army (i.e., Writing). These findings are similar to what we found in the AVOICE analyses. In addition, although a number of the dimensions described in Table 2 were also assessed in the AVOICE, we also identified several new basic interests that appear related to Army jobs. For example, the AVOICE did not assess a unique dimension related to information technology. However, activities related to this basic interest dimension are becoming increasingly important both in the military and in civilian jobs more generally and several of the interest measures we identified in our review included an information technology scale. We also identified a number of scales that may be particularly relevant for some MOS or special assignments but not others. The Teaching dimension may be relevant for Instructors or Drill Sergeants and the Sales dimension may be relevant for Recruiters but neither of these dimensions are likely to be relevant to Infantry. Instead, the Infantry MOS is likely to be related to a number of other dimensions in Table 2 (e.g., Combat). Therefore, the basic interests identified in our review may be useful for assignment into a broad range of MOS. In addition, compared to the AVOICE list, the dimensions described in Table 2 represent a more comprehensive list of basic interest dimensions that can be assessed

Discussion

Because there are so many entry-level jobs in the Army, it is important to have a comprehensive interest measure that reflects this diversity. The methods used in this study were chosen for this reason. By examining the structure of the AVOICE data, we were able to find several basic interest dimensions that have already shown promise in the military context. These data also provided the opportunity to ensure characteristics unique to military jobs are represented. To supplement the AVOICE data, the extensive literature search helped to identify additional basic interest dimensions that may not be represented in the AVOICE. While this literature search did produce many new interest dimensions, many of these were not included in the AVID because they had limited applicability to the Army population. In addition to the more comprehensive basic interest structure included in the AVID, the forced-choice format will make AVID more useful than previous interest measures when it comes to job assignment. As previously discussed, applicants will be less able to distort their responses to align with a preconceived notion of any particular MOS. The forced-choice format will also allow for more information to be gathered in a shorter testing time, which is always beneficial for accessions screenings.

In addition to identifying a useful basic interest structure for Army MOS, the current study also contributes to the broader literature on the dimensionality of vocational interests. Although previous work has incorporated various basic interest dimensions in the assessment of vocational interests (Alley & Matthews, 1982; Harmon, Hansen, Borgen, & Hammer, 1994; Liao, Armstrong, & Rounds, 2008), a widely accepted structure of basic interests has not yet been identified. The present study adds to the existing literature using new methods to identify relevant basic interests that may contribute to future research in this area. As noted above, past research has suggested that the broader RIASEC types may be too broad to differentiate among some jobs and that basic interests may be more useful for understanding modern occupations (Day & Rounds, 1997). Therefore, the current study can contribute to efforts to assess and examine basic interests as predictors of occupational choice and workplace behavior.

The next steps in developing and validating the AVID include statement development and pretesting. For CAT administration, a large number of interest statements must be developed and pretested. The pretest data will be used to estimate item response theory (IRT) parameters indicating their extremity and discriminating power (i.e., the capability to differentiate examinees with high, medium, and low levels of basic interests). Statements exhibiting poor discrimination will be culled from the pools used to create forced-choice items for adaptive or nonadaptive test administrations. In nonadaptive testing, forced-choice items will be created by manually pairing statements that are similar in social desirability and extremity. With CAT, this will be accomplished using an algorithm that also administers the forced-choice items that are most informative for an examinee at each point during a test. In both cases, the forced-choice responses will be scored using a multidimensional pairwise preference IRT model (Stark et al., 2005) in order to determine an examinee’s level of each basic interest. Based on research using this approach to measure other noncognitive constructs (Stark et al., 2014), we expect that the AVID will be resistant to faking and other types of response biases (e.g., acquiescent responding).

Once AVID has been administered to large samples of Soldiers, the validity of the forced-choice basic interest scores will be examined. An important consideration for the validity of the AVID is the match between Soldiers and their MOS. As noted above, Holland’s (1997) model of vocational interests suggests that individuals who are in jobs that they are interested in will be more satisfied, more successful (e.g., perform better), and will stay on the job longer. As such, examining the match between individuals and their jobs is particularly important for the validation process. Here, past research has also shown that profiles of interests provide the best operationalization of interest fit. In other words, a single interest dimension will not necessarily predict important work outcomes (Nye et al., 2017; Nye, Perlus, et al., 2018). Instead, matching an individual’s profile of interests to the interest profile for the job will provide a more comprehensive view of fit and the likelihood that individuals will be successful in their jobs.

Given the importance of interest fit for examining the validity of the AVID, it is also important to consider how fit will be operationalized. In the interest literature, interest fit is often operationalized using various congruence indices (Brown & Gore, 1994). A number of congruence indices have been proposed in the literature and have demonstrated validity for predicting work outcomes (Nye et al., 2017). Despite these promising results, the limitations of congruence indices are widely recognized (Edwards, 1993). As a result, some authors have suggested using polynomial regression as an alternative approach to operationalizing congruence (Edwards, 1993) and recent research has demonstrated the benefits of this approach for the vocational interest literature (Nye, Perlus, et al., 2018). Therefore, this approach may be useful for the AVID as well. Although a full discussion of polynomial regression is beyond the scope of the present study, interested readers are referred to past work on this topic for more information (Edwards, 1993; Nye, Perlus, et al., 2018).

Regardless of the approach that is used to operationalize interest fit, additional research is needed to validate the dimensions chosen for the AVID and the statement pools developed to assess them. This research should examine a broad range of outcomes and the utility of this assessment beyond other predictors. Again, past research has shown that vocational interests can predict workplace outcomes like task performance, training performance, job satisfaction, turnover, organizational citizenship behavior, and counterproductive work behavior (Nye, Butt, et al., 2018; Nye, et al., 2017). Past research has also shown that vocational interests can predict these outcomes over and above other predictors like cognitive ability and personality (Van Iddekinge et al., 2011). It would be useful to examine whether these findings hold for the AVID as well. In addition, it would also be useful to conduct a longitudinal examination of the AVID to determine if a Soldier’s interests at the time of accession are related to outcomes throughout his or her career in the Army, and how much this relationship varies based on the congruence between a Soldier’s interest profile and the profile of his or her MOS. Therefore, more research is needed to explore these issues in a military context.

One limitation of the current study is that only 20 dimensions were identified for the AVID. Although the methods used in the present study provided a thorough review of available research, there may be other dimensions that could also be relevant for military assessment. For example, it is possible that there are other relevant interest dimensions that were not assessed in the AVOICE or in previous vocational interest measures. In addition, some basic interest dimensions were intentionally excluded due to their lack of perceived relevance for Army MOS. Finally, it is also possible that some of the interest dimensions that were identified may not end up being relevant for Army MOS. Despite these possibilities, the various dimensions identified for the AVID make it one of the most comprehensive measures of basic interests, particularly with regard to its relevance to Army occupations and military assessment. Nevertheless, future research will be needed to examine the relevance of these dimensions for Army MOS and identify additional dimensions that may help to differentiate MOS. One potential approach to identifying additional useful dimensions could involve a full job analysis of particular MOS that may not be represented well by the 20 initial AVID dimensions. Understanding the tasks that are performed in these MOS can suggest additional basic interests that may be useful for interest assessment in the military. Other approaches may also be useful for identifying additional basic interest dimensions and future research is needed to explore these opportunities.

The U.S. Army is an all-volunteer force and, as such, applicants can choose to access in MOS for which they qualify. The AVID is not intended to change this essential part of Army accessions but what it will do is provide guidance to applicants about which MOS would be the best fit for their interests. Given the number of entry-level MOS potentially available to applicants and the limited information traditionally provided in the accessioning process, this additional guidance will hopefully lead applicants into a better fitting MOS. The proper match between applicant and job characteristics will lead to successful Soldiers that are more likely to stay in their MOS and in the Army.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences [W911NF-16-C-0038];

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abrahams, N. M., Neumann, I., & Githens, W. H. (1970). An assessment of faking on the strong vocational interest blank under actual selection conditions (No. NPTRS-STB-70-6). San Diego, CA: Naval Personnel and Training Research Lab. [Google Scholar]

- Alley, W. E., & Matthews, M. D. (1982). The vocational interest career examination: A description of the instrument and possible applications. The Journal of Psychology, 112, 169–193. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1982.9915374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. D., & Gore, P. A. (1994). An evaluation of interest congruence indices: Distribution characteristics and measurement properties. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(3), 310––327.. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. P. (1990). An overview of the army selection and classification project (Project A). Personnel Psychology, 43(2), 231–239. doi: 10.1111/peps.1990.43.issue-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., Drasgow, F., & Roberts, B. W. (2007). Constructing personality scales under the assumptions of an ideal point response process: Toward increasing the flexibility of personality measures. Psychological Assessment, 19, 88–106. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day, S. X., & Rounds, J. (1997). “A little more than kin, and less than kind”: Basic interests in vocational research and career counseling. The Career Development Quarterly, 45, 207–220. doi: 10.1002/cdq.1997.45.issue-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J. R. (1993). Problems with the use of profile similarity indices in the study of congruence in organizational research. Personnel Psychology, 46(3), 641–665. doi: 10.1111/peps.1993.46.issue-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garry, R. (1953). Individual differences in ability to fake vocational interests. Journal of Applied Psychology, 37, 33. doi: 10.1037/h0058887 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L. R. (2006). Doing it all bass-ackwards: The development of hierarchical factor structures from the top down. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, M. A., Paullin, C. J., Bruskiewicz, K. T., & White, L. A. (2003, November). The army vocational interest career examination. Paper presented at the annual conference of the International Military Testing Association, Pensacola, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, L. W., Hansen, J. C., Borgen, F. H., & Hammer, A. L. (1994). Strong Interest Inventory: Applications and technical guide. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J. L. (1959). A theory of vocational choice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 6, 35–45. doi: 10.1037/h0040767 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices (3rd ed. ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Hough, L., Barge, B., & Kamp, J. (2001). Assessment of personality, temperament, vocational interests, and work outcome preferences. In Campbell J. P. & Knapp D. J. (Eds.), Exploring the limits in personnel selection and classification (pp. 111–154). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ingerick, M., & Rumsey, M. G. (2014). Taking the measure of work interests: Past, present, and future. Military Psychology, 26(3), 165––181.. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkendall, C. D. (2017). [Tier one performance screen (TOPS)] Unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- Kristof‐Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta‐analysis of person–Job, person–Organization, person–Group, and person–Supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342. doi: 10.1111/peps.2005.58.issue-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.-Y., Armstrong, P. I., & Rounds, J. (2008). Development and initial validation of public domain basic interest markers [Monograph]. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 159–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low, K. D., Yoon, M., Roberts, B. W., & Rounds, J. (2005). The stability of vocational interests from early adolescence to middle adulthood: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 713–737. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye, C. D., Butt, S. M., Bradburn, J., & Prasad, J. (2018). Interests as predictors of performance: An omitted and underappreciated variable. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 108, 178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nye, C. D., Perlus, J. G., & Rounds, J. (2018). Do ornithologists flock together? Examining the homogeneity of interests in occupations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 107, 195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nye, C. D., Su, R., Rounds, J., & Drasgow, F. (2012). Vocational interests and performance: A quantitative summary of over 60 years of research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 384–403. doi: 10.1177/1745691612449021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye, C. D., Su, R., Rounds, J., & Drasgow, F. (2017). Interest congruence and performance: Revisiting recent meta-analytic findings. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 138–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, S., Chernyshenko, O. S., & Drasgow, F. (2005). An IRT approach to constructing and scoring pairwise preference items involving stimuli on different dimensions: The multi-unidimensional pairwise preference model. Applied Psychological Measurement, 29, 184–201. doi: 10.1177/0146621604273988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, S., Chernyshenko, O. S., Drasgow, F., White, L. A., Heffner, T., Nye, C. D., & Farmer, W. L. (2014). From ABLE to TAPAS: A new generation of personality tests to support military selection and classification decisions. Military Psychology, 26, 153–164. doi: 10.1037/mil0000044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, S., Chernyshenko, O. S., Drasgow, F., & Williams, B. A. (2006). Item responding in personality assessment: Should ideal point methods be considered for scale development and scoring? Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 25–39. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Iddekinge, C. H., Putka, D. J., & Campbell, J. P. (2011). Reconsidering vocational interests for personnel selection: The validity of an interest-based selection test in relation to job knowledge, job performance, and continuance intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 13. doi: 10.1037/a0021193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Iddekinge, C. H., Roth, P. L., Putka, D. J., & Lanivich, S. E. (2011). Are you interested? A meta-analysis of relations between vocational interests and employee performance and turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 1167–1194. doi: 10.1037/a0024343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, L. A., & Young, M. C. (1998). Development and validation of the Assessment of individual motivation (AIM). Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]