ABSTRACT

Art therapy has been found to help Veterans with symptoms of post-traumatic stress. There is however limited scholarship on the differences in outcomes based on dosage (short-term vs. long-term treatment) especially for active duty military service members (SMs). This mixed methods program evaluation study examined feedback from SMs on their experiences of art therapy in an integrative medical care center after 3 weeks of group therapy and at the end of treatment (average time of 2 years). Data included participant demographics, feedback surveys, and narrative responses from SMs experiences of art therapy. The results indicate that longer-term art therapy resulted in improved perceived outcomes compared with the short term 3-week intervention. SMs with longer time in service reported the most improved self-reported outcomes. Women SMs expressed more positive emotions during their art making. Specific themes that were effectively addressed through art therapy included frustration tolerance, grief and loss, emotion regulation, personal insight, resiliency, and trauma processing. SMs also highlighted the unique and transformative role of the relationship with the therapist with alleviation of symptoms. The findings suggest benefits to long-term art therapy including improved ability in SMs to be aware of their symptoms and communicate effectively with others.

KEYWORDS: Art therapy, post-traumatic stress, traumatic brain injury, active duty military, program evaluation

What is the public significance of this article?—This program evaluation paper presents findings from Service Members (SMs) who received art therapy as a part of treatment for post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury at an integrative medical care center.Findings indicate that art therapy helped SMs who had served longer time in service as well as those with psychosocial challenges of frustration tolerance, grief and loss, emotion regulation, personal insight, resiliency, and trauma processing. In addition, art therapy helped SMs process, visually express and verbalize aspects of their symptoms that they reported could not be addressed elsewhere and facilitated communication and better use of other treatment professions.

Introduction

Since 2001, over 2.7 million military Service Members (SMs) have been deployed worldwide (McCarthy, 2018). Recent reports show that large numbers (480,748 or 20%) of returning Veterans require clinical treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 375,230 or 15% have been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, 2017; Dolan et al., 2012; Summerall, 2017; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2011). PTSD is a psychological disorder that occurs as a result of a traumatic event and entails symptoms such as intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, as well as changes in arousal and reactivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). More specifically, individuals with PTSD may reexperience their trauma as flashbacks, dissociative reactions, or nightmares; they tend to avoid trauma reminders, thoughts, and feelings; they may hold negative beliefs about themselves and the world; and they are inclined to hypervigilance, sleep disturbance, and irritability (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). TBI is triggered by an external force and brings about changed or disrupted brain operations (Bahraini et al., 2014; Wall, 2012). According to the VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines (2016), TBI must include at least one of following criteria: decreased level or loss of consciousness, loss of memory before or after injury, alteration in mental state (e.g., confusion), neurological deficits (e.g., weakness), or intracranial lesion. Approximately one-third of Veterans with TBI also experience PTSD symptoms (Tanielian et al., 2008), with TBI sustained during deployment frequently preceding development of PTSD (Yurgil et al., 2014). The co-occurrence of these complex conditions is a particular challenge and exacerbates symptoms like sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression, cognitive deficits, and embodied memory experiences (Bahraini et al., 2014; Kroch, 2009). In addition, individuals with both PTSD and TBI are likely to experience other long-term psychiatric consequences including mood disorders, cognitive and perceptual challenges as well as difficulties in emotion regulation (Walker, Kaimal, Gonzaga, Myers-Coffman, & DeGraba, 2017). It appears that demographic characteristics like race/ethnicity (Coleman, 2016), rank and branch (Baker et al., 2009; Ramchand et al., 2010), and time in service (Kline et al., 2010; Reger, Gahm, Swanson, & Duma, 2009) influence the severity of symptoms. One of the challenges in treating PTSD is that traumatic memories are stored through images, physical sensations, smells, and sounds, and often are not verbally accessible (Van der Kolk, 2014; Walker et al., 2016). Indeed, a recent review found that trauma-focused verbal therapies such as cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure therapy only have limited success with SMs (Steenkamp, Litz, & Marmar, 2020).

Over the last decade, art therapy has become an increasingly acknowledged complementary intervention for military Veterans with PTSD and TBI symptoms (Nanda, Barbato Gaydos, Hathorn, & Watkins, 2010; Pachalska et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2017). According to Lobban (2017), verbally conveying internal states can be virtually impossible for SMs who have been trained to guard their emotions and thoughts. During art therapy sessions, clients can safely and nonverbally express what is inside and practice managing overwhelming emotions by directing them into visual creative outputs (Jones, Walker, Drass, & Kaimal, 2017). Trauma survivors find it less threatening to retell their memories through pictures and visual symbolism than to speak about them (Harris, 2009; Spiegel, Malchiodi, Backos, & Collie, 2006). Having a visual narrative allows Veterans to grasp distressing material as an extension of the self as well as an external element of their combat experience (Gantt & Vesprini, 2017; Lobban, 2014). Over time, fractured and dissociated memories can be reintegrated (Lobban, 2014). Furthermore, the artmaking process is perceived as relaxing and enjoyable (Jones et al., 2017; Spiegel et al., 2006) and invites progressive self-expression. This gradual exposure can bring about a reduction of arousal, improved emotional self-efficacy and self-esteem, as well as positive emotions (Lobban, 2014), which in turn promotes recovery and reentry into civilian life (Lande, Tarpley, Francis, & Boucher, 2010; National Endowment for the Arts, 2015).

There are several promising art therapy interventions for military Veterans and active-duty SMs with PTSD and TBI. For example, mask-making (Walker et al., 2017) allows clients to focus on their own experiences and encourages safe externalized representations. Another intervention, montage paintings (Berberian, Walker, & Kaimal, 2018), can serve as a consolidated yet complex visual reflection of clients’ experiences. Furthermore, expressive writing sessions (Jones et al., 2017; Landless, Walker, & Kaimal, 2018) have been found to assist clients in gaining perspective on their experiences and alternate points of view. While individual art therapy sessions with SMs tend to focus on identity, transition, a sense of self, and an increased understanding of personal triggers for trauma responses, group sessions aid with socialization and communication (Jones et al., 2017). In a recent mixed-methods study about Veterans’ perspectives on the acceptability of art therapy, Palmer, Hill, Lobban, and Murphy (2017) found that Veterans appreciated the way art therapy helped them explore difficult feelings and fostered a positive group experience in a soothing environment. Art therapy has also been used successfully in conjunction with other interventions. For example, a case study of a senior active duty military SM with chronic PTSD and TBI showed that art therapy in combination with acupuncture provided relief from PTSD symptoms including flashbacks and nightmares and increased frustration tolerance and emotional stability (Walker et al., 2017). Likewise, when employing art therapy together with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) in a recent randomized controlled trial for combat-associated PTSD, Decker, Deaver, Abbey, Campbell, and Turpin (2019) found that depression and most PTSD symptoms improved to a greater extent than when CPT was used alone. The authors further learned that participants perceived a greater benefit from art therapy (Likert score of 4.8) than from CPT (Likert score of 4.2) and had higher retention in treatment compared with CPT alone.

While there are many examples of art therapy with SMs, the distinction between the effects of short-term vs. long-term treatment has not often been examined. Art therapy approaches for SMs tend to differ depending on the length of treatment, with short-term interventions being more therapist-led and long-term treatment having an increasingly client-led format (Jones et al., 2017). The goals of short-term treatment may be to increase stabilization, establish safety and provide understanding about symptoms, whereas long-term goals may be to increase insight, identity development, emotional regulation, and empathy and support for self and others (Jones et al., 2017). A recent evaluation of long and short-term art therapy interventions for SMs with PTSD and TBI showed that, while short-term art therapy treatment improved aspects of identity, self-expression, and positive emotion, deeper issues of guilt, grief, loss, and trauma processing were more effectively addressed in long-term treatment (Kaimal, Jones, Dieterich-Hartwell, Acharya, & Wang, 2018). Furthermore, questionnaire responses indicated that more sessions resulted in overall higher satisfaction with treatment and that those SMs who were in service longer were more likely to benefit from art therapy sessions (Kaimal et al., 2018). These results were promising, however, did not fully clarify the outcomes of long-term art therapy with SMs. There are few studies that have assessed long-term art therapy (Eren et al., 2014; Greenwood, 2011; Greenwood, Leach, Lucock, & Noble, 2007), and no studies have specifically examined long-term art therapy with active duty SMs in the military.

Methods

The purpose of this program evaluation was to improve the quality of art therapy interventions. The SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines (Goodman et al., 2016) were followed for the write-up and structuring of this report.

Study context

The context for this program evaluation was a long-term art therapy program at a military hospital outpatient facility that was part of an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts, Creative Forces®: NEA Military Healing Arts Network, which is a partnership with the US Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs and the state and local arts agencies with administrative support provided by Americans for the Arts. SMs were referred to art therapy by physicians and other health-care providers at an integrative health-care clinic to address goals including improving mind-body awareness and emotional regulation, decreasing anger and irritability, gaining insight into underlying triggers for trauma-related hyperarousal or reactivity, etc. Once referred to art therapy, SMs attended three successive levels.

Level 1: SMs joined an introductory Level 1 group series of three group sessions, which entailed mask-making, montage painting and creative writing, followed by one individual art therapy session. The group sessions were limited to five participants at a time. They encouraged self-expression in a safe and positive environment and were intended to provide an introduction to spontaneous, general art-making. During the individual sessions, SMs processed their group experiences with the art therapist and identified treatment goals that would best be addressed through continued art therapy.

SMs then had the opportunity to proceed to a six-week Level 2 group series which met for 2 h per week and was held in a cohort format. During the six sessions, SMs were led through directives that allowed them to explore deeper issues such as grief, loss, and soul searching. More specifically, they were asked to depict their greatest fear and greatest comfort, write a dialogue between themselves and an entity of their choice, depict their soul, and create a box project to help with the processing of complicated grief. At the completion of this series, SMs once again meet individually with the art therapist to identify concrete and clear goals for continued one-on-one art therapy sessions.

These continued one-on-one art therapy sessions included further and more individualized processing of grief, loss, specific traumatic events, moral injury, spiritual injury, and identity development.

Throughout their treatment, and regardless of which level they were enrolled in, SMs were welcomed to attend an open studio pottery workshop and engage in art activities that supplemented the clinical art therapy they received. All art therapy services were provided by experienced and credentialed art therapists who also collected the surveys as part of their clinical programming. More detailed description of the program is available in Jones et al. (2017).

Survey instruments

Four surveys, developed to gather customized feedback on the art therapy services at the medical center, were given as part of this program evaluation: Survey A on the first day of Level 1, Survey B after three group art therapy sessions, Survey C during the individual session (after Level 1), and Survey D at the end of treatment if the SM participated in art therapy beyond Level 1. Survey A included demographic and qualitative information on participant perceptions of art therapy pre-treatment. Survey B contained feedback from SMs after Level 1 group art therapy sessions. Survey C included open-ended responses from SMs about their perspectives and goals during an individual session, following Level 1 group sessions. Survey D included feedback from SMs who continued with art therapy beyond Level 1. In total, 170 participants answered Survey A, 144 in Survey B, 70 in Survey C, and 72 in Survey D. The surveys were de-identified and data were aggregated for analysis. Program evaluation studies are exempt from requiring IRB approval at the site. Instead these are reviewed by public affairs, the security office, and hospital command, who approved this paper for publication.

Sample

In total, 222 SMs from the integrative health-care clinic completed at least one survey. Among them, 14 respondents were female and 208 were male. Fifty-four had mild TBI and 26 had moderate/severe TBI as evaluated at the integrative health-care clinic and self-reported on the surveys. The majority of TBIs and PTSD were combat related. Regarding their grade, 106 participants reported their rank as enlisted and 28 reported being officers (while 88 did not provide their grade). As for branch, 58.90% of the participants had served in the Army, 2.40% in the Navy, 4.70% in the Air Force, 32.10% in the Marines, and 1.80% in a branch not otherwise specified. On average, participants had 15 (standard deviation = 7.80) years of time in service with a range of 2 to 35 years.

Data analysis

Quantitative analyses of survey responses were used to: 1) Examine whether the post-treatment outcomes differed by participants’ demographic variables (including gender, time in service, and grade), and 2) Compare post-treatment outcomes reported in Survey B with those reported in Survey D. Some post-treatment outcomes were continuous measures. For example, the changes in self-reported health indicators were Likert scale measures taking values of −2 (significant negative change) to 2 (significant positive change). The rest of the post-treatment outcome measures were categorical variables. For example, the measures on therapy themes were dichotomous variables, such as “which areas did you address in your mask?”, which was followed by several options. For the purpose of data analysis, these became “did you address the theme of ‘Transitions’ through your mask therapy” – Yes/No. Wilcoxon scores tests were used to examine whether continuous outcomes differed by participants’ grade (enlisted/officer) or gender (women/men), to account for the skewed distributions of the outcome measures. Chi-square tests were used to examine whether categorical outcomes differed by participant’s grade. Fisher exact tests were used to examine whether categorical outcomes differed by gender (women/men), to account for the small cell sizes for women participants. Spearman tests were used to determine whether participant’s time in service was associated with their continuous outcome measures. To compare post-treatment outcomes reported in Survey B with those reported in Survey D, paired t-tests were used and continuous outcome measures reported by the same person in B were contrasted with his/her answer in D; McNemar’s test were used to compare the categorical outcome measures reported by the same person in B vs his/her answer in D. We used 0.05 as significance level. All the analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

For the qualitative analysis, open-ended responses to questionnaires B and D were compared. The mean time interval between the completion date of questionnaires B and D was 237 days, with a range of 25–665 days. In total, 66 SMs completed the narrative parts in both questionnaires. The responses to the following two questions were compared: (a) Did art therapy help you differently than other treatments you have received? If so, how? and (b) Further thoughts, comments, or suggestions. The data were organized by individual, with B and D responses for each participant listed side by side. The distinct changes from B to D were examined thematically, according to Braun and Clark’s (2012) six-phase approach and guidelines. More specifically, after familiarization with the data, initial codes were generated, followed by a search for themes, a review of the potential themes, the defining and naming of themes, and, lastly the completion of the final report.

Results

The results indicate that some demographic features like time in service and gender were related to differences in outcomes. The difference in outcomes by grade and time in service were replicates of our previous findings (Kaimal et al., 2018), and time in service continued to be an important determinant of perceived benefits of art therapy. In addition, initially officers were found to report benefits of art therapy faster than enlisted SMs but these differences were not evident at the later time point. Some differences were seen by gender as well. Although there were very few women in the sample (n = 14), they focused more on positive and future oriented subject matters during the Level 1 tasks, whereas the men tended to focus on processing negative emotions and past memories through the Level 1 tasks (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Difference in outcomes by gender

| Women n = 14 |

Men n = 208 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | P-value in Fisher’s Exact Test | |

| Did you feel positive while you were creating the mask? | |||

| Yes | 83.3 | 25.2 | 0.0066 |

| No | 16.7 | 74.8 | |

| Did you feel happy while you were creating the mask? | |||

| Yes | 50.0 | 3.5 | 0.0022 |

| No | 50.0 | 96.5 | |

| Did you address the theme of Future Goals through your writing? | |||

| Yes | 66.7 | 24.8 | 0.0441 |

| No | 33.3 | 75.2 | |

| Did you address the theme of Future Goals through your montage? | |||

| Yes | 83.3 | 31.6 | 0.0174 |

| No | 16.7 | 68.4 | |

| Did you feel relaxed while you were creating the montage? | |||

| Yes | 100.0 | 45.3 | 0.0106 |

| No | 0.0 | 54.7 | |

| Did you address the area of Frustration Tolerance through your art therapy? | |||

| Yes | 66.7 | 25.0 | 0.0451 |

| No | 33.3 | 75.0 | |

| Did you address the area of Transitions through your art therapy? | |||

| Yes | 100.0 | 32.8 | 0.0017 |

| No | 0.0 | 67.2 |

As can be seen from Table 1 specifically, 83.30% of women participants reported that they felt positive while creating masks, while 25.30% of men reported the same (P = .007 in Fisher’s exact test). When asked whether they addressed the theme “Future Goals” through their writing session, 66.70% of women participants answered yes while 24.80% of men answered yes (P = .044 in Fisher’s exact test). Similarly, when asked whether they addressed the theme “Future Goals” through their montage session, 83.30% of women participants answered yes while 31.60% of men answered yes (P = .017 in Fisher’s exact test). In addition, all of the women participants reported that they felt relaxed while creating the montage, while 45.30% of men reported feeling relaxed in montage sessions (P = .011 in Fisher’s exact test). Regarding areas addressed in art therapy treatment, 66.70% of women reported that they addressed “Frustration Tolerance” and 100% of women reported that they addressed “Transitions,” while the percentages were 25.00% and 32.80%, respectively, in men.

In terms of the perceived impact and unique contributions of art therapy in the integrative treatment model of care received at the site, overall participants reported more positive feedback in Survey D than in Survey B. Participants reported being able to address issues in art therapy that they could not bring up anywhere else and that it helped them both within the sessions and outside with other providers. The changes were significantly stronger with long-term art therapy than short-term art therapy (see Table 2). According to Table 2, the majority of study participants had higher scores in Survey D compared to Survey B, but there were eight participants whose average in D was slightly lower than in B. Based on additional analyses we still conclude that participants had generally better outcomes in Survey D compared to Survey B.

Table 2.

Participant perceptions of the art therapy

| Questions that are asked in both Surveys B and D |

Score in Survey B Mean (SD) |

Score in Survey D Mean (SD) |

Paired T-Test (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| What effect did art therapy have on your overall treatment (1 no effect to 10 significant effect) |

7.8 (1.4) | 9.0 (1.3) | 5.52 (p <.0001) |

| Did your participation in art therapy have an impact on sessions with other providers (1 no impact to 10 significant impact) |

6.9 (2.3) | 8.2 (2.2) | 3.75 (p =.0005) |

| Describe the progress you made addressing the issues you processed through art therapy (1 no progress to 10 significant progress) |

7.3 (1.8) | 8.8 (1.2) | 5.42 (p <.0001) |

| How do you view art therapy’s role within the interdisciplinary treatment offered (1 not necessary to 10 essential) |

8.6 (1.9) | 9.5 (1.2) | 3.08 (p =.0035) |

| Were you able to address areas in art therapy that you had difficulty addressing elsewhere (1 no at all to 10 very much) |

8.1 (2.3) | 9.7 (0.8) | 4.62 (p <.0001) |

SMs identified “Frustration Tolerance,” “Grief and Loss,” “Emotion Regulation,” “Personal Insight,” “Resiliency,” and “Trauma Processing” as the predominant themes that were addressed by art therapy. Participants reported that they addressed more themes through art therapy treatment in Survey D compared to their answers in Survey B (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in the extent to which symptoms were addressed in short vs. longer-term art therapy

| People who answered “Yes” in Survey B |

People who answered “Yes” in Survey D |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did you address these themes through art therapy? | n | % | n | % | McNemar’s Test Statistic | P-value |

| Frustration Tolerance | 15 | 31.9 | 25 | 53.2 | 5.5556 | 0.0184 |

| Grief and Loss | 19 | 40.4 | 32 | 68.1 | 8.8947 | 0.0029 |

| Emotional Regulation | 19 | 40.4 | 27 | 57.4 | 4.0000 | 0.0455 |

| Personal Insight | 18 | 38.3 | 36 | 76.6 | 13.5000 | 0.0002 |

| Resiliency | 6 | 14.3 | 18 | 42.9 | 8.0000 | 0.0047 |

| Trauma processing | 18 | 40.9 | 29 | 65.9 | 4.8400 | 0.0278 |

The qualitative findings support these results from the surveys. When asked if they were able to address areas in art therapy that they could not address elsewhere, SMs used more words and more superlative descriptions in time point D compared with time point B, pointing to the unique strength of the art therapy services: “It was my first time doing anything like this … very helpful … like nowhere else.”“[An] experience that was unmatched … far better than all … ” “[This was the] best therapy method I have ever received. Everyone needs art therapy.” “[This was the] single most significant factor in what I believe to be life-saving therapy … Drastically changed my life.” “[This was] one of the most essential programs available … huge influence into my healing process.”

SMs also referred to the impact of art therapy on their overall care and how it helped them in other aspects of their treatment in the integrative care setting:“[This was an] integral part in the process as a whole. Without art therapy, I doubt I would have made significant progress in other treatments … art therapy was the foundation of it all.” “[This was the] most trusted and effective therapy out of approximately 12 different modalities.”

In terms of psychological health conditions that were addressed through art therapy, SMs referred to being able to confront emotions previously unexpressed more in Survey D compared with Survey B. “[Art therapy] allowed me to really open up and confront the uncomfortable, that which I wanted to hide or mask and to address the negative, accept what I can’t resolve and really understand what’s inside me.” “Some of the projects seemed extremely difficult to process at first, but afterward I was glad I talked through them.” “[Art therapy] challenged me to think about what bothers me and turn that into art. I was challenged every time and had to work on my frustration tolerance and patience for when things went wrong.” “Art pushed me out of my comfort zone and helped me ‘externalize’ some issues.”

Relatedly, SMs also tended to refer to being able to regulate their emotions more in Survey D compared with Survey B. “It gave me a way to deal with my emotions … I learned to deal with most scenarios of life … ” “I learned skills that I use daily … ” “It provided me with an outlet for my feelings.” “Art therapy … allowed me to get to a point where I can control my anger safely without my anger controlling me.”

According to the quantitative results, more SMs reported being able to process trauma through art therapy, especially at the end of treatment at the two-year point. This finding was supported in the qualitative responses as well: “I was able to open up and see inside myself without having to talk to anyone. It gave me a positive way to process the loss of life which I experienced during combat … process and express previously un-accessible parts of my memory and traumatic experiences by providing an outlet in a safe atmosphere.” “ … art therapy was a direct approach that allowed me to process traumatic events on a time line that was comfortable for me.” “It allowed me to bring my memories and nightmares/fears into the real world and have control over them.”

Some aspects of the SMs’ experiences were not captured in the quantitative data. These included references to the physical and tangible aspects of the art media, sharing of oneself through the art product and the enjoyment embedded in the arts: “It let me identify what I liked in tangible ways. I can now do things I like instead of just thinking about what I might like … It gave me a way to physically see and touch my thoughts.”

Several SMs spoke about the enjoyment of art more in Survey D than in Survey B: “Expressing myself through art has significantly helped my mood.” “For me the biggest impact was in the self-enjoyment aspect of my life. I believe the activities and projects showed me that my interest in the outdoors was more important than I thought. It has led me to be more engaged in the woods and this engagement has significantly improved my mood.” “It allowed me to focus on the simple beauty of things in life.”

SMs also spoke of the social aspects of sharing through artmaking in group settings and the perceived benefits of sharing oneself through the art: “To be able to share stories, experiences, and pain with your brothers in arms is a relief.” “For the first time I was able to share experiences that I never shared in the past.” “[C]onnecting with people and expressing in ways I couldn’t do at the time.” “It has provided a means of connecting with others that regular conversation doesn’t.”

Lastly, a recurring theme was the influential and therapeutic role of the art therapist especially the unconditional positive regard that she conveyed to the SMs: “[Her] ability to listen compassionately and genuinely was far better than all but one psychotherapist I’ve met with throughout my treatment.” “There was never any judgment in our art – it was always perfect like it was and she appreciated that in us. [She] understands her patients and allows them to be themselves always.” “She was the single key to helping me through my issue. She allowed me to be me and if I was in a bad mood it was o.k. to be in a bad mood.” “She is able to see people and what is bothering them … She provided an environment highly conducive to sharing deeply repressed feelings and emotions. Environment was non-judgmental, non-threatening, and highly inclusive.”

Figures 1–6 show examples of artwork made by SMs in the different levels of art therapy, including group and individual sessions.

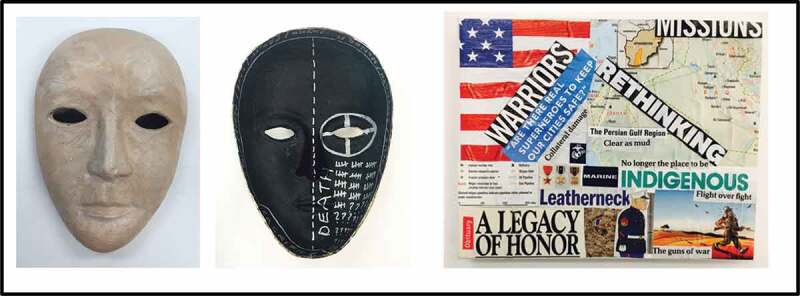

Figure 1.

Example of a Marine’s work in Level 1 art therapy groups

Figure 1. Artwork created by an active duty male service member who served as an infantry/sniper in the Marine Corps with over 18 years of service and seven deployments before he began art therapy. The mask he created represents his need to keep going despite the dark hole of sacrifice shown on the inside, with deaths of his comrades tallied. His montage represents a reflection on various aspects of military experience as well as on legacies of honor and collateral damage. Level 1 art therapy provided the service member with an opportunity for non-verbal self-expression.

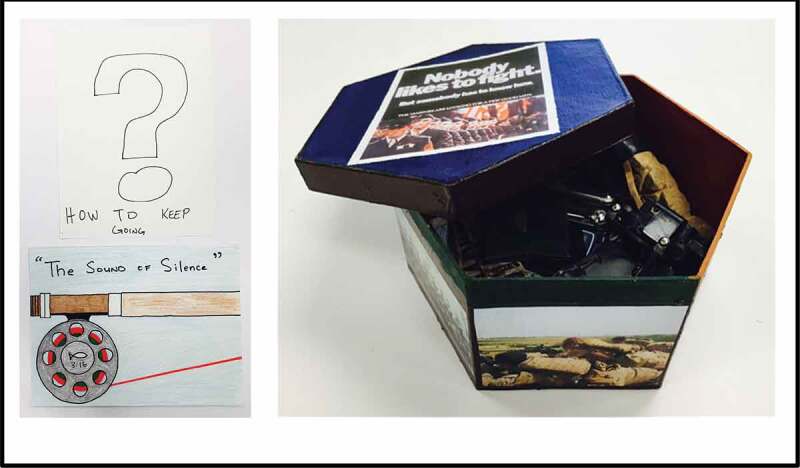

Figure 2.

Example of a Marine’s work in Level 2 art therapy groups

Figure 2. Examples of artwork created by the Marine in Level 2 art therapy groups. The first set is a pair of drawings representing his greatest fear at the moment, not knowing how he will keep going after he leaves support of his peers and treatment team, and his greatest comfort at the moment, fly fishing, which he described as helping to save his life through reconnection with nature and God. His celebration/commemoration box shows life as a Marine on the outside and contains images and memorabilia on the inside that represent deaths or near-death experiences. During Level 2 art therapy groups, the service member focused more on supports and resources he had in his life and helped him expose that which he had been suppressing that was contributing to chronic conditions.

Figure 3.

Example of a Marine’s work in ongoing individualized art therapy

Figure 3. In ongoing individualized art therapy sessions, the Marine first worked through “letting go of the black” in preparation of deep grief work. His work then focused on creating a list of each comrade who had died, creating a memorial tile for each of over 60 individuals. While creating the tile for each he was able to process circumstances of their deaths, the significance of each person to him, and to resurface positive memories that had been buried with the negative. Afterward he arranged the tiles together and created an American flag across them all, as to lay them to rest with honor. Ongoing work primarily focused on processing trauma, grief, and loss, and all of the associated emotions. The remaining 2 months of art therapy prepared him for his transition out of the military.

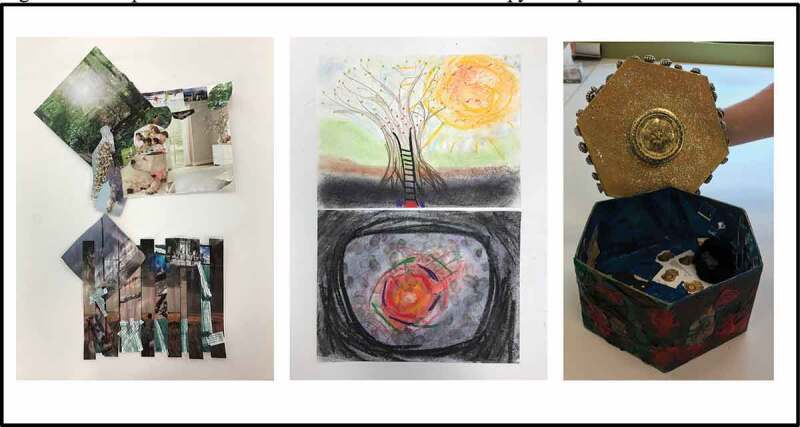

Figure 4.

Example of a Soldier’s work in Level 1 art therapy groups

Figure 4. Artwork created by an active duty female service member who served in military intelligence and criminal investigation in the Army with over 18 years of service and three deployments before she began art therapy. The mask she created summarizes the effects of a full career, internalizing her own feelings. The front is split, showing goals of being loving and connected and the other side showing faking the funk. The inside represents feeling a lack of voice, darkness that she felt, and a nod to the sanctuary she felt at home with her family. Her montage represents challenges from her career as well as symbolism that she was beginning to find her voice, which fostered feelings of hope.

Figure 5.

Example of a Soldier’s work in Level 2 art therapy groups

Figure 5. During Level 2 art therapy groups, the Soldier continued to process more deeply feelings of drowning, or being buried by pain caused by her work, as well as the recognition of her strengths, grounding resources, and strong support system she had at home. In creating the work, especially the celebration/commemoration box, she processed feelings associated with her experiences with deaths of comrades, victims of cases with which she had been involved, and maltreatment she had experienced.

Figure 6.

Example of a Soldier’s work in ongoing individualized art therapy

Figure 6. During ongoing individual art therapy sessions the Soldier utilized art therapy for emotional release, support, and processing of that which was arising in her daily life and worked to improve her own self-love and compassion despite past experiences.

Discussion

In this paper, we presented findings from a program evaluation on the differences in outcomes based on dosage of art therapy services (short-term of 3 weeks versus long term of up to 4 years) for active duty military SMs with post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury. Art therapy services included group sessions, individual sessions, community art studio experiences and open art therapy studio options and feedback data was available from SMs (n = 66).

The findings included quantitative and qualitative results and suggest that SMs with longer time in service reported the most positive impacts of art therapy. Both similarities and variations were noted in how SMs responded to art therapy services. Overall, longer-term outpatient interventions seemed to be particularly beneficial and lead to increased verbalization and communication. Furthermore, women SMs tended to express positive emotions in their Level 1 artwork more so than their male counterparts. In general, there are fewer studies on women SMs and this program evaluation study proposed the significant perceived benefits for women and men. The finding that longer time in service was associated with better art therapy outcomes was also found in a previous study (Kaimal et al., 2018), and here it additionally shed light on SMs specific experiences with art therapy over a longer period. These findings suggest that art therapy might be especially helpful for SMs with longer deployments as well as chronic symptoms that were not effectively addressed elsewhere.

In addition, the longer-term treatment was almost unanimously found to result in sustained improved subjective impressions in the areas of frustration tolerance, grief and loss, emotion regulation, personal insight, resiliency, and trauma processing. Although the findings implied that the SMs had improved outcomes within 3 weeks, these results appeared strengthened with longer-term sessions, suggesting the potential of sustained subjective improvement in functioning with longer-term treatment. As seen in previous studies with SMs, art therapy may assist with addressing experiences that were difficult to articulate in traditional verbal psychotherapy (Jones et al., 2017; Lobban, 2014; Walker et al., 2017).

The qualitative results supported many of the quantitative findings but in particular, highlighted the unique and transformative role of the art therapist in helping SMs address their clinical goals. The SMs pointed to the role of the art therapist in creating a non-judgmental and safe environment in which to process and communicate previously unexpressed and misunderstood experiences. The qualitative and quantitative data sources together provided a comprehensive picture of how art therapy may help externalize and process psychosocial challenges faced by active duty SMs. Lastly, the findings point to the value of integrating evaluation into clinical practice (Kaimal & Blank, 2015; Kaimal et al., 2018), both as a way to personalize care for patients, as well as a means to systematically track outcomes.

There are several limitations to this study. The questions in the evaluation surveys were mostly based on the art therapy tasks without any standardized measures embedded in the feedback forms, which restricted the generalizability of the results. This is a definite area for improvement in future such program evaluation efforts. The use of standardized measures for symptoms of mood, emotion regulation and interpersonal functioning would help provide greater credence to the findings. The findings on gender differences in particular have to be interpreted with caution as the sample of women was too small to make any generalizations. Another shortcoming was the lack of distinction between mild and moderate/severe TBI. As this program evaluation study relied on self-reports only those diagnoses that were shared could be reported. Overall, there are limitations to the program evaluation approach. As the long-term outpatient interventions were self-selected, SMs who found the initial sessions beneficial were more likely to stay on and request art therapy treatment, which in turn may have biased Survey D responses. Lastly, it is virtually impossible to determine the impact of a particular art therapist (including rapport with the SMs) on the effectiveness of an art therapy intervention. Future studies can examine the change factors of the therapist and therapeutic relationship that facilitate positive outcomes for patients. Although a systematic cohort-based study would be a better method to assess the impact of patient characteristics and choices on the impacts and outcomes of art therapy this current effort serves as an important pilot for developing such a study. Further studies could also examine the differences between intensive outpatient art therapy vs. traditional long-term outpatient therapy with regard to sustained outcomes.

Summary

This program evaluation study provided an overview of the outcomes of art therapy for active duty military SMs with PTS and TBI. The data were collected as part of program evaluation of the clinical services. Findings indicate that art therapy helps to externalize the many invisible wounds of war including complex emotions associated with TBI and PTS as well as identity struggles, grief, loss, self-regulation and processing of trauma. However, the results of this program evaluation cannot be generalized due to some of the limitations in our methods. Further research using standardized measures of psychosocial functioning is needed to validate these preliminary findings and this evaluation serves as an important precursor to such efforts.

Acknowledgments

Creative Forces®: NEA Military Healing Arts Network is an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in partnership with the US Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs and the state and local arts agencies. This initiative serves the special needs of military patients and Veterans with traumatic brain injury and psychological health conditions, as well as their families and caregivers. Administrative support for the initiative is provided by Americans for the Arts

Funding Statement

National Endowment for the Arts [1855995-38-C-19].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Disclaimer

The identification of specific products, scientific instrumentation, or organization is considered an integral part of the scientific endeavor and does not constitute endorsement or implied endorsement on the part of the author, DoD, or any component agency. The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, US Government, or the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The NEA does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information in this material and is not responsible for any consequences of its use.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed. ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bahraini, N. H., Breshears, R. E., Hernández, T. D., Schneider, A. L., Forster, J. E., & Brenner, L. A. (2014). Traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 37(1), 55–75. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D. G., Heppner, P., Afari, N., Nunnink, S., Kilmer, M., Simmons, A., … & Bosse, B. (2009). Trauma exposure, branch of service, and physical injury in relation to mental health among US Veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Military Medicine, 174(8), 733–778. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-03-3808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberian, M., Walker, M. S., & Kaimal, G. (2018). ‘Master My Demons’: Art therapy montage paintings by active-duty military service members with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress. Medical Humanities. Advance Online Publication. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2018-011493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In Cooper H. (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 57–71). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. A. (2016). Racial differences in posttraumatic stress disorder in military personnel: Intergenerational transmission of trauma as a theoretical lens. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(6), 561–579. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1157842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decker, K. P., Deaver, S. P., Abbey, V., Campbell, M., & Turpin, C. (2019). Quantitatively improved treatment outcomes for combat-associated PTSD with adjunctive art therapy: Randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy. Advance Online Publication. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2018.1540822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center . (2017). DoD worldwide numbers for TBI. Retrieved from http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi.

- Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense . (2016). Clinical practice guideline for the management of concussion-mild traumatic brain injury. Retrieved from https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/mtbi/mTBICPGFullCPG50821816.pdf

- Dolan, S., Martindale, S., Robinson, J., Kimbrel, N. A., Meyer, E. C., Kruse, M. I., … & Gulliver, S. B. (2012). Neuropsychological sequelae of PTSD and TBI following war deployment among OEF/OIF veterans. Neuropsychology Review, 22(1), 21–34. doi: 10.1007/s11065-012-9190-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren, N., Öğünç, N. E., Keser, V., Bıkmaz, S., Şahin, D., & Saydam, B. (2014). Psychosocial, symptomatic and diagnostic changes with long-term psychodynamic art psychotherapy for personality disorders. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(4), 375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2014.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt, L., & Vesprini, M. E. (2017). Using the instinctual trauma response model in a military setting. In Howie P. (Ed.), Art therapy with military populations: History, innovation, and applications (pp. 147–156). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, D., Ogrinc, G., Davies, L., Baker, G. R., Barnsteiner, J., Foster, T. C., ... & Leis, J. (2016). Explanation and elaboration of the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines, V. 2.0: Examples of SQUIRE elements in the healthcare improvement literature. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(12), e7–e7.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, H. (2011). Long term individual art psychotherapy. Art for art’s sake: The effect of early relational trauma. International Journal of Art Therapy, 16(1), 41–51. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2011.570274 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, H., Leach, C., Lucock, M., & Noble, R. (2007). The process of long-term art therapy: A case study combining artwork and clinical outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 17(5), 588–599. doi: 10.1080/10503300701227550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D. A. (2009). The paradox of expressing speechless terror: Ritual liminality in the creative arts therapies’ treatment of posttraumatic distress. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(2), 94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2009.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. P., Walker, M. S., Drass, J. M., & Kaimal, G. (2017). Art therapy interventions for active duty military service members with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. International Journal of Art Therapy (Formerly Inscape). doi: 10.1080/17454832.2017.1388263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, G. & Blank, C.L. (2015). Program evaluation: A doorway to research in the creative arts therapies. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 32 (2), 89–92. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.1028310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, G., Jones, J. P., Dieterich-Hartwell, R., Acharya, B., & Wang, X. (2018). Evaluation of long- and short-term art therapy interventions in an integrative care setting for military service members with post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury. The Arts in Psychotherapy. Advance Online Publication. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2018.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, A., Falca-Dodson, M., Sussner, B., Ciccone, D. S., Chandler, H., Callahan, L., & Losonczy, M. (2010). Effects of repeated deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the health of New Jersey Army National Guard troops: Implications for military readiness. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 276–283. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroch, R. (2009). Living with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—a hermeneutic phenomenological study (Doctoral dissertation). University of Calgary. Retrieved from http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/002/NR54472.PDF [Google Scholar]

- Lande, R. G., Tarpley, V., Francis, J. L., & Boucher, R. (2010). Combat trauma art therapy scale. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(1), 42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2009.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landless, B. M., Walker, M. S., & Kaimal, G. (2018). Using human and computer-based text analysis of clinical notes to understand military service members’ experiences with therapeutic writing. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 62, 77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2018.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lobban, J. (2014). The invisible wound: Veterans’ art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 19(1), 3–18. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2012.725547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lobban, J. (2016). Factors that influence engagement in an inpatient art therapy group for veterans with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. International Journal of Art Therapy, 21(1), 15–22. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2015.1124899 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lobban, J. (Ed.). (2017). Art therapy with military veterans: Trauma and the image. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, N. (2018, March 21). 2.77 million service members have deployed since 9/11. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/chart/13292/277-million-service-members-have-deployed-since-9-11/

- Nanda, U., Barbato Gaydos, H. L., Hathorn, K., & Watkins, N. (2010). Art and posttraumatic stress: A review of the empirical literature on the therapeutic implications of artwork for war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Environment and Behavior, 42(3), 376–390. doi: 10.1177/0013916510361874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Endowment for the Arts . (2015, November 12) Creative arts therapy a useful tool for military patients. Author. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/news/2015/creative-arts-therapy-useful-tool-military-patients [Google Scholar]

- Pachalska, M., Pronina, M. V., Mańko, G., Chantsoulis, M., Mirski, A., Kaczmarek, B., … Kropotov, J. D. (2013). Evaluation of neurotherapy program for a patient with clinical symptoms of schizophrenia and severe TBI using event-related potentials. Acta Neuropsychologica, 11(4), 435–449. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, E., Hill, K., Lobban, J., & Murphy, D. (2017). Veterans’ perspectives on the acceptability of art therapy: A mixed-methods study. International Journal of Art Therapy, 22(3), 132–137. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2016.1277250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand, R., Schell, T. L., Karney, B. R., Osilla, K. C., Burns, R. M., & Caldarone, L. B. (2010). Disparate prevalence estimates of PTSD among service members who served in Iraq and Afghanistan: Possible explanations. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 59–68. doi: 10.1002/jts.20486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger, M. A., Gahm, G. A., Swanson, R. D., & Duma, S. J. (2009). Association between number of deployments to Iraq and mental health screening outcomes in US army soldiers. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(9), 1266–1272. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. (2016). A literature review of the therapeutic mechanisms of art therapy for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Art Therapy, 21(2), 66–74. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2016.1170055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, D., Malchiodi, C., Backos, A., & Collie, K. (2006). Art therapy for combat-related PTSD: Recommendations for research and practice. Art Therapy, 23(4), 157–164. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2006.10129335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, M. M., Litz, B. T., & Marmar, C. R. (2020). First-line psychotherapies for military-related PTSD. JAMA. 323 7 656 doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerall, E. L. (2017). Traumatic brain injury and PTSD: Focus on veterans. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/co-occurring/traumatic-brain-injury-ptsd.asp [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian, T., Jaycox, L. H., Schell, T. L., Marshall, G. N., Burnam, M. A., Eibner, C., … Vaiana, M. E. (2008). Invisible wounds: Mental health and cognitive care needs of America’s returning veterans. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9336.html [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office . (2011). VA mental health: Number of veterans receiving care, barriers faced, and efforts to increase access (GAO-12-12). Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-12.

- Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York, NY: Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M. S., Kaimal, G., Gonzaga, A. M., Myers-Coffman, K. A., & DeGraba, T. J. (2017). Active-duty military service members’ visual representations of PTSD and TBI in masks. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 12(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2016.1267317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M. S., Kaimal, G., Koffman, R., & DeGraba, T. J. (2016). Art therapy for PTSD and TBI: A senior active duty military service member’s therapeutic journey. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 49, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wall, P. L. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury in current military populations: A critical analysis. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 18(5), 278–298. doi: 10.1177/1078390312460578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurgil, K. A., Barkauskas, D. A., Vasterling, J. J., Nievergelt, C. M., Larson, G. E., Schork, N. J., … & Baker, D. G. (2014). Association between traumatic brain injury and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in active-duty marines. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(2), 149–157. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]