ABSTRACT

Everyone who serves in the military (and survives the experience) will eventually become a Veteran, and most will face the challenge of finding a civilian job. This paper investigates how contemporary Veterans experience the transition period between military exit and entrance into civilian life and how their own actions before separation shape their post-transition outcomes. We follow 35 servicemembers through the transition process, interviewing them before and several months after they left the military. These interviews reveal the importance of three factors – the conditions triggering their exit, the strength of their military identity, and their own planning (or lack thereof) for the transition to civilian life – in enhancing or detracting from achievement of a stated post-military goals and objective success in moving into work or school. The strength and depth of an individual’s institutional identity shapes how and when servicemembers plan for military exit and how they adjust to unanticipated military exits. Early planning reflects anticipatory socialization for new civilian roles and is associated with better post-military outcomes. But early planning is often hindered by a strong military identity or facilitated by a weak military identity. These findings have important implications for the military and advocates who serve them with the recent military policy changes to transition assistance and the retirement pension system that encourage early planning for post-military life.

KEYWORDS: Veterans, transition, identity, anticipatory socialization

What is the public significance of this article?— This study shows how military identity and the circumstances leading to exit from the military shape career planning and preparation for the transition back to civilian life. Our findings suggest that those who have a strong military identity tend to begin planning for a new career too late to design concrete, effective steps to meet their goals. Conversely, those with weak military identities planned for their transition early, often because their long-term career path treated military service as a stepping-stone to other goals, rather than as a long-term career.

Introduction

Everyone who serves in the military (and survives the experience) will eventually become a Veteran, and most will face the challenge of finding a civilian job. The employment outcomes of new Veterans have been the subject of a great deal of scholarly and policy attention over the past decade and a half (cf Guo, Pollak, & Bauman, 2016; Humensky, Jordan, Stroupe, & Hynes, 2013; Kleykamp, 2013; Loughran, 2014; MacLean, 2010). Much of this work focuses on documenting the extent of Veteran employment challenges and identifying ways to assist Veterans in making a smooth transition back to civilian life. Less research is informative of the unfolding processes generating these outcomes because few studies collect information from the same people longitudinally over the period between initiating an exit from the military and reintegrating to civilian life. Rather, most research gathers retrospective data from individuals after their transition experience. This study asks: What do soon-to-become Veterans do during the transition process, both before and after separating from the military as they work to successfully navigate the transition to civilian work life, and what circumstances and behaviors hinder or enable their transition?

The transition period between initiating exit from the military and establishing a “new normal” civilian career is a crucial time during which many important decisions are made (or not made), yet there is limited longitudinal data that cover pre-and post-separation experiences. In this study we examine three factors we anticipated to influence the transition experience and outcomes based on prior research and theory: the circumstances leading to military separation, the strength of one’s military identity, and planning for post-military life. We draw on theories of adult transitions to provide insight into the role of exit triggers and identity in adult transitions, and anticipatory socialization as a framework for understanding the role and importance of planning for separation from military service. There is no single theory of military to civilian transition, but a constellation of theories and models drawn on to understand this process (Pedlar, Thompson, & Andrew Castro, 2019), with new models and theories emerging every day. These evolving models share in common an evolution from focusing on traumatic experiences to the accounting for the range of transition experiences, and from a sharp focus on work to a broad concern with identity and wellbeing. Military Transition Theory was one of the first models to build on Schlossberg and to apply the main insights to the military transition (Kintzle & Castro, 2018). A new model of military transition, the Success in Transition model (Whitworth, Smet, & Anderson, 2020), serves as the guiding model for the most current transition assistance programming in the DoD. Although our data collection precedes these developments, our results reinforce the rationale for new approaches–that the military transition is experienced by all, not only those with traumatic events, and extreme adjustment challenges, and that preparation must involve wholistic approaches to this major change in experience.

We see the contribution of this qualitative study as offering a valuable empirical perspective on military transition by using longitudinal qualitative data that spans the pre- and post-separation experience allowing us to connect both the anticipation of and reflection on this major life change. The majority of research draws on retrospective information from those who have transitioned out of the military, leading to the potential for recall bias and re-interpreting past experiences differently than they were experienced at the time (although see Vogt et al., 2018 for a notable exception). Additionally, much of the research on role exit or vocational change emphasizes voluntary exit and change, whereas a substantial number of military transitions are not voluntary (from roughly a quarter to over half depending on the definition of voluntary or involuntary (Department of Defense, 2018d). Finally, given the strong role played by military socialization into a (perhaps) total institution with a strong culture and socialization into a new identity, it is vital to unpack how military identity shapes the process of military exit. Recent models of military transition emphasize the importance of military identity to the transition process, but little empirical scholarship is cited to support the assertion or to explicate the mechanisms linking a strong military identity to transition outcomes (eg Whitworth et al., 2020). The return to civilian life involves a re-orientation to a civilian identity that may have been radically altered through military socialization and service. All of these substantive research contributions can provide insights for policy and practice to continue to assist transitioning Veterans re-integrate into civilian work life.

Theory of adult transitions and military transitions

Virtually all theories and models of military transition draw on Schlossberg’s model of adult transitions to some degree (Schlossberg, 1981; Schlossberg, Waters, & Goodman, 1995) because it describes a general model of the regular adult experience of a transition. Schlossberg identifies “transition” as key organizing feature of adult development because of the possibility of change in life trajectory that comes with any transition. A transition is defined as any event (or nonevent) that results in a change of assumptions about oneself or the world and therefore leads to a change in behavior and relationships (Schlossberg, 1981, p. 5). Military transition is one example; the process of separating from military service implies a move from exclusive (or at least primary) employment on active duty to exclusive (or primary) activity as a civilian. Such new activities might include civilian employment, pursuing civilian education or training, volunteer work, or retirement. The transition process or period involves a liminal status around this event, and the associated changes of assumptions about oneself or the world described by Schlossberg. Research on the military transition drawing on Schlossberg is often centered on Veterans in higher education and how to adapt to civilian school and work (Anderson & Goodman, 2014; DiRamio & Jarvis, 2011; Griffin & Gilbert, 2015).

In her theory, adaptation to a transition involves the process of integrating the transition into one’s life and is influenced by a range of factors from personal to situational to environmental. Job and career changes (both those that happen, and those expected but do not actually take place), represent significant adult transitions. Schlossberg later elaborated the model to specify four types of influences on transitions: situation, self, support, and strategies (Schlossberg, 2011). This study examines exit triggers as a primary situational factor, military identity as a core aspect of the self, and planning as a strategy that collectively shape the transition from military back to civilian life. Although our participants described various sources of support (the fourth S) from family, friends, a transition office or counselor, and organized transition workshops, those were experienced as part of the planning process. Our analysis did not identify these to be as important or consequential as exit triggers, military identity, and planning in differentiating who did relatively better or worse after separation.

Some researchers have subsequently built on Schlossberg’s model in constructing a specific model of military transitions. Military Transition Theory (MTT) incorporates elements of Schlossberg, primarily identifying three overlapping phases of the process: approaching the transition, managing the transition, and assessing the transition (Kintzle & Castro, 2018). It incorporates individual, interpersonal, community, and military organizational factors involved in the process. Building on MTT, the most recent Success in Transition (SIT) Model further elaborates MTT to incorporate specific transition programming during Phases 1 and 2 (Whitworth et al., 2020). This latest model serves as the framework for the current Transition Assistance Program offered by DoD to aid military service members and Veterans. These conceptual models of military transition layout a complete conceptual picture of the process of military transition for the development of policy and programmatic efforts to assist Veterans. They also provide a framework for empirical research like this study to test the components of the theory and evaluate the extent to which the theoretical logic is consistent with empirical observation. Both MTT and SIT theories emphasize the important role of military culture and identity in the transition, and the importance of different kinds of transition triggers and emphasize the value of effective transition planning. Our empirical research hones in on observing the first and second stages of the transition process, specifically tracing how military identity and transition triggers shapes the approach to and management of the transition, through a planning process that involves anticipatory socialization into potential new cultures and identities.

Exiting circumstances: What triggers the transition?

Because those who join the military do so voluntarily, those who serve may presume that exit from service will be voluntarily and take place after a great deal of consideration and forethought. However, the transition out of the military is not always a voluntary or anticipated event despite knowledge that one’s time in service will eventually have to come to an end. These different triggering events that initiate military exit, whether anticipated long in advance, or totally unanticipated, are expected to shape how transition is experienced and how individuals weather this period of change, whether from individuals’ planning and actions during the transition, or what structural resources are available to assist them. Prior research on military exit supports Schlossberg’s theory finding that the timing and circumstances of military exit shape the transition experience (Beland, 1992). The literature on employee turnover has emphasized the exit circumstances leading to voluntary employee turnover (eg Lee & Mitchell, 1994). Yet, previous research on military exit reveals differences between those experiencing voluntary versus involuntary exit (Coll & Weiss, 2013; McNeil, 1964; Zoli, Maury, & Fay, 2015), reminding us that while military entrance is now all voluntary, military exit isn’t necessarily so. In 2018, under half of all separations from military service were voluntary (44.7%) with 28.1% considered involuntary and 26.8% coming from retirements (which included medical retirement.) The figures for involuntary separation are higher among enlisted (30.2%) compared with officers (7.9%), while officers were higher on retirement (54.8%) than enlisted (23.8%) (Department of Defense, 2018d).

Schlossberg’s model of adult development categorizes transitions as “anticipated” and “unanticipated” (Schlossberg, 1981, 2011), dovetailing with voluntary and involuntary separations. Unanticipated triggers are common among military members: injury, medical problems, failure to be promoted are all regular occurrences in the military. Some triggers might be driven by the military institution, such as with a failure to promote. Servicemembers transitioning under these circumstances have had more challenging transitions (Coll & Weiss, 2013; Zoli et al., 2015). But a next duty assignment may be undesirable for personal or professional reasons prompting a dilemma about whether to endure or to exit (if they have the option.) Family circumstances may make continuation of military life unsustainable forcing another moment of personal contemplation. Conversely, some transitions have been planned since entry into the military, such as when individuals use military service as a means to achieve longer-term goals like pursuing higher education or obtaining security clearances to leverage for civilian work. The end of enlistment contracts or service obligations are typically well-understood and anticipated transition points.

Military identity

Exit triggers represent a situational factor, but one’s military identity operates as an aspect of the self that influences the military transition. As one of the most successful agents of socialization in society, the military routinely takes men and women from different places, cultures, and backgrounds and trains them on the shared attitudes, values, and actions expected in this new institutional world, and their role in it (Arkin & Dobrofsky, 1978; Higate, 2001; Jackson, Thoemmes, Jonkmann, Lüdtke, & Trautwein, 2012). Men and women in service often describe becoming more confident, capable, and responsible individuals, frequently comparing themselves as being “ahead” of their civilian peers. In Making the Corps, Ricks (2007) reports on how the Marines socialize new recruits into Marine culture to see themselves not only as distinct from but superior to civilians. As individuals become more embedded in the military world, either through longer time in service, or in highly specialized military fields like infantry and special forces valorized within military culture, they become more socialized to a “military mind” (Mills, 1956), strengthening their military identity. The separate and distinctive military culture that servicemembers learn to live within makes the transition out fraught with anxiety and concerns about status loss (Ahern et al., 2015; Cooper, Caddick, Godier, Cooper, & Fossey, 2018; Cooper et al., 2017), leading some transitioning members to cling to their cultural norms and identity. Military identity has been described as an ethnic identity (Daley, 1999) and as a social identity that involves recognizing a new group membership, internalizing the values and norms of the group, seeing themselves as members this new group, and then comparing that group to others (Haslam, 2004; Tajfel, 1982; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Military identity shapes how individuals see themselves relative to the civilian world, and an impending exit from the military community and culture initiates a significant identity shift, and for some, even an identity crisis. And it shapes how people approach the impending separation (Fuller & Redfering, 1976; Jolly, 1996; Walker, 2013).

Ebaugh (1988) describes the process of role exit as involving a transition of self-identity accompanying a role transition. Her study only sampled individuals making a voluntary role exit and identified the development of an “ex-role” identity as a crucial component of role transition. This identity change happens through a process of shifting reference groups, in which people evaluate themselves less on the standards of the exiting role and more on the standards of the entering role. Reference groups are the standard to which one compares themself, and those in or seeking entry into groups internalize the standards of the reference group. They also serve as gate-keepers in that they legitimate a role transition. The identity shifts required to build a post-military identity involve a shift away from identifying as a military person with a military reference group, toward seeing oneself as a civilian, often involving a hybrid Veteran identity and reference group. This identity shift happens through anticipatory socialization.

Anticipatory socialization and planning for military separation

Leaving military service means leaving one vocation or occupation and entering another or occupying oneself with other pursuits. For servicemembers and their families, military service is more than a job – it demands a constellation of sacrifices in service to the military institution (Segal, 1986) and offers relatively generous benefits and compensation to ease some of those burdens (Kleykamp & Hipes, 2014). In addition to the aforementioned identity changes, leaving the military requires preparation for the changes in income, compensation, and benefits as well as the changes to self-concept, identity and culture. Planning for exit from the military can and should involve a range of activities including information gathering, goal setting, general research (on schools, career fields, skillsets, cities), attending classes, networking, job fairs, conducting informational interviews, and more. Planning represents a crucial component of a successful transition, initiated by anticipatory resocialization back to civilian life, culture, and a post-military identity. Lack of planning for major transitions is associated with less successful transitions and greater difficulty in role adjustment (Mein, Higgs, Ferrie, & Stansfeld, 1998).

We see planning as a process that begins with anticipatory socialization, and effective planning for post-military life includes anticipatory socialization for new civilian roles (Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, 2007; Ebaugh, 1988; Kramer, 2010). Anticipatory socialization refers to the adoption of the attitudes and values of a group to which one does not (yet) belong which eases the transition into the new group and the adjustment once one becomes a member (Merton & Kitt, 1950). It is usually seen involving informal activities and behaviors of self-preparation and psychological planning such as gathering information, clarifying expectations, and building new social engagement. These things precipitate goal setting, and more concrete, specific planning activities like attending a financial planning seminar, a resume writing course, etc … (Kim & Moen, 2002) because one needs some basic understanding of a new role to set realistic goals and to know what courses, programs, or certifications are required. Anticipatory socialization also allows people to begin to explore and identify with new values, norms, and orientations of new roles before actually assuming them through role rehearsal (Ebaugh, 1998). Socialization into work involves anticipatory socialization beginning as early as childhood (Jablin, 2001), and socialization out of work, into retirement, also involves anticipatory socialization (Curl & Ingram, 2013). This kind of informal planning of anticipatory socialization predicts better adjustment and satisfaction in retirement (Elder & Rudolph, 1999).

Military sociologists have noted the important role of anticipatory socialization before enlistment into the military, such as when individuals shave their hair, begin intensive physical training, and study military history in advance of their entrance to the military (Lucas, 1971; Trainor, 2008; Yeung & Gifford, 2011), all as part of a process to instrumentally prepare for military training but also to shift reference group and alter self-identity. College students choose a major, join clubs and participate in internships as part of anticipatory socialization into desired careers (Jablin, 2001). These same anticipatory socialization practices are important when preparing for military exit as well, because it involves resocialization back to a civilian labor market, perhaps a new vocation and occupational setting, shifting of cultural context, and a change to self-identity. It is fundamentally a process of trying out a new cultural apparatus that comes with potential new civilian roles; it is about starting to build a new cultural competence that helps focus planning (Cooper et al., 2018, 2017). Goal setting, researching career requirements, even purchasing new clothing are all part of the planning activities required to achieve one’s goals and secure productive employment with a career change, and these steps begin with the less formal work of seeking information, envisioning oneself and importantly setting appropriate expectations about post-military life.

In the paper that follows, we describe our qualitative data collection and our approach to coding and analyzing longitudinal interviews conducted with individuals before and after their separation from the military. After discussing the major results from our analyses we conclude with a consideration of how these results comport with the new directions in transition assistance programming with transitioning servicemembers.

Methods

Participants

We recruited individuals within 12 months of their separation from the military for voluntary in-depth interviews who all provided informed consent to be interviewed, and to have the interview recorded, transcribed, and de-identified for analysis. At the end of the pre-separation interview, we asked about willingness to participate in a follow-up interview 6–12 months after their separation, collecting contact information from those who agreed. All personally identifying information was stored securely, with access limited to study personnel. We recruited through the transition offices at four Army installations (domestic and abroad) where one author worked as a contractor or where the garrison commander facilitated access. At one of these bases, study recruitment information was shared to an e-mail distribution list of known transitioning personnel, and at the others, we posted flyers, and recruited in person from those visiting the center. We also recruited in Southern California where we did not have official base access but recruited though flyers and advertisements posted in public places near a large military installation and by using snowball sampling.

We interviewed 48 servicemembers in an initial wave of pre-separation interviews between December 2012 and May 2014 to study the expectations, goals, and plans of individuals at the beginning of the transition process; 35 (72%) participated in a follow-up interview sometime within 12 months after their separation to ascertain how their transition process was experienced, what were their outcomes, and how their expectations and goals shifted as they experienced life after military service. Most initial interviews were conducted in person and lasted around 60 minutes. Follow-up interviews were typically conducted electronically (by Skype) or by phone given the geographic mobility associated with military transition (Bailey, 2013, p. 46) and were of a similar length.

Our sample experienced a diverse set of transition situations, including individuals who left after their first-term enlistment as well as those who served as many as 30 years. Table 1 shows several key demographic characteristics of our interviewees along with their pseudonym. We provide a rank range in a few cases to ensure confidentiality. Participants were officers and enlisted personnel representing the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force as well as men and women representing different racial and ethnic backgrounds. The majority of our sample had experienced a deployment, and a little over half had experienced direct combat (which we define as taking enemy fire).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of interview subjects

| Branch | Sex | Race/ethnicity | Rank | Status & Years In | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryan | Marine Corps | Male | Mixed Race | E6 | Medical Retirement (16 years) |

| Jameson | Navy | Male | White | E4 | Separating (7 years) |

| Heather | Navy | Female | White | O4 | Separating (7 years) |

| Ernie | Navy | Male | White | O4 | Retiring (22 years) |

| Alexander | Marine Corps | Male | White | O5 | Retiring (22 years) |

| Logan | Army | Male | White | E5 | Separating (6 years) |

| Claire | Army | Female | White | E5 | Separating (7.5 years) |

| Ashley | Army | Female | White | E4 | Medical Separation (3 years) |

| Lucy | Navy | Female | White | O3 | Separating (5 years) |

| John | Navy | Male | White | >E6 | Retiring (25 years) |

| Nick | Army | Male | White | E6 | Separating (10.5 years) |

| Dana | Navy | Female | White | E5 | Separating (7.5 years) |

| Samuel | Marine Corps | Male | White | E6 | Separating (12 years) |

| Emma | Navy | Female | White | O3 | Separating (4.5 years) |

| Tracy | Navy | Female | White | O4 | Retiring (28 years) |

| Liam | Army | Male | White | E4 | Separating (3 years) |

| William | Army | Male | White | E6 | Medical Retirement (20 years) |

| Doug | Air Force | Male | White | E6 | Retiring (20 Years) |

| Anthony | Army | Male | White | E6 | Separating (8 years) |

| Steven | Marine Corps | Male | White | E6 | Medical Retirement (12 years) |

| Brad | Army | Male | White | E6 | Medical Separation (10.5 years) |

| David | Army | Male | Black | >E6 | Retiring (22 years) |

| Marco | Army | Male | Latino | >E6 | Retiring (30 years) |

| Sarah | Army | Female | White | E5 | Separating (6 years) |

| Darnell | Army | Male | Black | >E6 | Retiring (26 years) |

| Thomas | Army | Male | White | W* | Retiring (27 years) |

| Matthew | Army | Male | White | >E6 | Retiring (22 years) |

| Tyrell | Army | Male | Black | E4 | Separating (3 years) |

| Joey | Army | Male | White | E5 | Medical Separation (8 years) |

| Tessa | Army | Female | Other | E5 | Chaptered Out (13 Years) |

| Jessie | Army | Male | White | E4 | Separating (9 years) |

| Peter | Army | Male | White | O3 | Separating (4 years) |

| Jayden | Army | Male | Black | E4 | Separating (12 years) |

| Jeremy | Army | Male | Black | O4 | Retiring (27 years) |

| Chelsea | Army | Female | White | E4 | Separating (8 years) |

Pseudonyms used and some ranks altered to ensure confidentiality.

Protocol and measures

Data for this specific study come from the transcripts of interviews conducted following a semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide was developed from the extant literature on military transition at the time to collect information about the role of goals, plans, social networks, and perceptions and expectations about civilian work in the transition process. Having a formal interview guide ensured a consistent set of questions were asked while allowing two different interviewers with familiarity with the military to be flexible in covering the subjects to facilitate rapport and conversational flow. Our interview guides are included as Appendix. The interview guide roughly follows a chronological ordering of key events in a military career and transition to civilian life. The pre-separation interviews focused questions on: how and why they joined the military; plans and behaviors related to separation; social networks; perceptions of and expectations for civilian life; experiences with transition programs and services; and recommendations for how to facilitate military transitions. The post-separation interviews focused on: recapping military separation history and experiences; reflecting on pre-separation goals, plans, and activities; post-separation adjustment experiences and reflections; experiences finding and starting work, school, or other activities; military identity and connection to military contacts and the institution.

Coding and analysis procedures

All interviews were recorded and transcribed by a commercial service into de-identified text files that use pseudonyms. We used Nvivo qualitative analysis software to organize transcripts, and to facilitate identification and recording of common themes across interviews. We engaged in several rounds of coding to analyze the data, following the “flexible coding” approach advocated by Deterding and Waters (2018). Our analytic process involved two primary types of codes: index and attributes (Deterding & Waters, 2018.) While many interview-based qualitative projects use a grounded theory approach we acknowledge that we entered the research with ideas about what concepts to investigate leading to the structure of our interview guide.

In a first round we conducted index coding (tagging a quote or section of text with a relevant code) of a set of broad themes drawn from the questions in the interview guide, as well as unanticipated themes that emerged as important during data collection. Emergent codes arose from interviewer reflective memos and study team dialogue about cases. One researcher coded the transcripts but did so in constant dialogue with the PI (and lead author), thus we did not explicitly measure inter-rater reliability. These index codes focused on the servicemember’s association with their military service, their plans/preparation/action for the transition, and their understanding of the meaning and value of their Veteran status.

We conducted a second round of coding that combined analytic and attribute, or case-based coding to systematically analyze how a few key analytic themes (circumstances of military exit, type of transition planning, and strength of military identity) related to each other. We drew on the index codes from the first round to develop these analytic codes to be applied to an entire case, rather than segments of text. Analytic attribute coding is especially useful when seeking to build a typology to define how cases cluster together (Deterding & Waters, 2018, p. 23; Weiss, 1995, p. 173). They allow for qualitative data reduction to engage in case comparison and analysis of patterns of association.

These analytic attribute codes include exit circumstances, identifying whether they were being pulled away from military service by future plans for civilian life or if they were being pushed out of the military due to institutional policies or issues (medical separation or retirement). We coded for planning for military exit oriented around the timing of planning with the categories: pre-planner, timed planners, and non-planners. We coded each case based on our assessment the strength of their identification with the military institution (high, medium, low), again inferred from the initial index coding of the interview transcripts. These military identity codes capture personal sense of pride and self-esteem resulting from their military affiliation. Finally, we incorporated codes connected to Schlossberg’s model described earlier by explicitly coding for “anticipated” or “unanticipated” transitions out of the military. During that coding process, we identified a need to elaborate the anticipated vs. unanticipated binary of the Schlossberg (Schlossberg, 1981, 2011) model to account for a new category of “anticipatable” transitions deriving from the unique aspects of military service in which there are common career points at which many people make important decisions about continuing their service.

Results and discussion

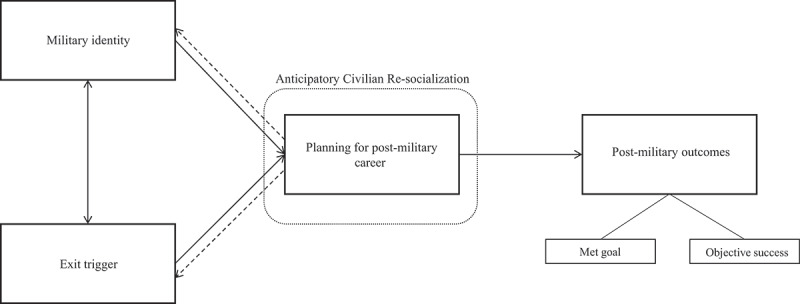

We identify three major factors shaping transition experiences and outcomes: exit triggers, military identity, and planning. Each has the potential to reinforce and influence the other. Figure 1 offers an abstraction of how these factors worked in concert to shape transitions. The circumstances triggering military exit and the strength of one’s military identity operated to alter the timing and nature of the planning activities undertaken by transitioning servicemembers. The timing and nature of planning was associated with post-transition outcomes, with earlier and more focused planning leading to both goal realization and objective success in finding stable work or schooling. We include dashed arrows back from planning to exit triggers and identity to anticipate how engaging in truly effective planning is to engage in early anticipatory re-socialization to civilian life. Engaging in anticipatory socialization leads to the subsequent specific, tangible steps toward transitioning to a new role and has the likely effect of weakening military identity, and possible altering exit circumstances. As a hypothetical example, someone facing an upcoming end of service contract may begin exploring civilian career opportunities several years beforehand. In doing so, she may become energized and excited about those opportunities and begin to see herself less and less strongly connected to the military and more interested in this future role. This might then prompt her to more deeply learn about that new possibility, and to align herself with a new career path, and to leave service as a result. Typically, the military wants to retain well-performing service members, so early exploration of alternatives has the potential to reduce retention at key career decision points. We discuss this tension in the concluding section of the paper, following a presentation of our results.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of major factors shaping military transition

Exiting circumstances: What triggers the transition?

Anticipated and anticipatable transitions: A decision point

Because those who join the military do so voluntarily it is often presumed that exiting from the service will be voluntary taking place after a great deal of consideration and forethought. Yet among our respondents the transition out of the military was often not a voluntary or anticipated event regardless of rank, years in service, or job type. The highly structured nature of the military career creates key decision points about continuation of military service that mark potential transition points because they prompt individuals to consider and reflect on their military career and on the relative merits of alternatives. Anticipatable military transitions are points in the military career that structure decisions about retention or exit: the end of an enlistment obligation, retirement (anytime after 20 years of service), or rank or age limits for continuing military service. In our coding for anticipated and unanticipated exit triggers, we found the need to account for the role of these key career points in shaping military exits. Our categories of transition types differ from DoD metrics of “voluntary,” “involuntary,” or “retirement” separations, and thus our sample distribution isn’t directly comparable with the demographics reported earlier on separation types. Notably, retirements include both medical and non-medical retirements which our respondents experienced differently in level of anticipation, as we discuss below

Table 2 summarizes the relationships among the major themes from our interviews. The majority of our sample, 38% (N = 13), exited the military because of an anticipatable transition trigger. These career crossroads between the institution’s expectations and the individual typically sparked reflection, leading servicemembers to take stock of their internal motivations for service and external circumstances that enable or constrain continuation of their military career. Those who decide upon exit can experience ambivalence about whether to stay or leave, causing conflict and stress, especially when the servicemember and their family differ about the decision. Anthony, a 30-year-old enlisted Soldier, loved serving in the military and if it wasn’t for his family, he would still be in the military. He said, “my family has wanted me to get out for the past seven and a half years [since I started serving].” After obliging his desire to go back to war with his unit during the re-enlistment decision, his wife ultimately pushed for him to get out at the next enlistment period. Anthony described, “[In] Afghanistan my wife and I kind of came to an agreement that it would be beneficial for the family if I left … she was pushing a little bit harder than I was. If it was up to me, honestly, I probably would have stayed in, but seeing my kids grow up on the internet was kind of tough.”

Table 2.

Summary of patterns among major themes

| Anticipated Exit | Anticipatable Exit | Unanticipated Exit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Planners | N = 10 | N = 3 | N = 3 | N = 16 (45%) |

| Met Own Goal: 7/10 (70%) | Met Own Goal: 2/3 (67%) | Met Own Goal: 2/3 (67%) | ||

| Objectively Successful: 9/10 (90%) | Objectively Successful: 3/3 (100%) | Objectively Successful: 3/3 (100%) | ||

| Military Identity: Low 10/10 (100%) | Military Identity: High 2/3 (67%); Medium 1/3 (33%) | Military Identity: High: 1/3 (33%); Low 2/3 (67%) | ||

| Timed Planners | N = 8 | N = 7 | N = 14 (40%) | |

| N = 0 | Met Own Goal: 3/8 (38%) | Met Own Goal: 4/7 (57%) | ||

| Objectively Successful: 6/8 (75%) | Objectively Successful: 5/7 (71%) | |||

| Military Identity: High 3/8 (38%); Medium 3/8 (38%); Low: 2/8 (25%) | Military Identity: High: 4/7 (57%); Medium 1/7 (14%); Low 2/7 (29%) | |||

| Non-Planners | N = 2 | N = 1 | N = 3 (8%) | |

| N = 0 | Met Own Goal: 0/2 (0%) | Met Own Goal: 0/1 (0%) | ||

| Objectively Successful: 1/2 (50%) | Objectively Successful: 0/1 (0%) | |||

| Military Identity: High 2/2 (100%) | Military Identity: Medium 1/1 (100%) | |||

| N = 10 (29%) | N = 13 (38%) | N = 11 (32%) | N = 34 |

1 respondent had not formally separated by the time of follow-up and is not included in the above table.

After 20 years of service, servicemembers are eligible to retire from the military. In this stage of the military career servicemembers exist in a constant state of anticipatable transition. The transition decision for retirees comes with achievement of a career milestone and access to a pension and other lifelong benefits, prompting different considerations about whether to continue to work after military retirement. The financial security of a pension affords retirees broader possibilities post-service. But retirees also experience ambivalence about the decision to end a long military career, likely the only significant work they have held. After serving 25 years in the military John echoed this when he said “to this point, really as an adult, the Navy is all I’ve known … ” He also stated that he has to get used to going by his first name instead of his rank and last name, which has been the primary way he has known himself during the past 25 years. Anticipatable transitions are prompted by the structure of a military career that call attention to making a choice about continuing to serve. Because all in our sample were in fact leaving the military, we did not speak to anyone who made the decision to stay in service at one of these decision points. Among those who made the choice to leave, there was often some ambivalence about the decision to separate which can complicate their transition experience.

Anticipated transitions: Voluntary exit

Anticipated transitions from military service occur when servicemembers express wholly self-initiated intentions to leave the military, independent of structured career decision points. Typically, these servicemembers have long planned their exit from military service, making their transition a gradual process that is entirely desired and volitional. For them, a military career was rarely a goal at entry. 29% of our sample (N = 10) left the military with an anticipated exit. For some, like Heather, a 33-year-old Navy doctor early service experiences revealed incompatibility with military life leading to an early decision to exit once her obligation was fulfilled. “When I was deployed, I was pretty sure I was gonna get out after my payback was done after the four years … it kind of sealed the deal being on deployment … it wasn’t something I wanted to do again and I realized that there are more opportunities outside.” For individuals like Heather, military life simply doesn’t click and early on they realize they will not make the military a career.

In making a distinction between anticipated and anticipatable, we emphasize that while bureaucratic or structural features lead to contemplation about a transition, that does not mean that an individual actually does anticipate or expect a transition for him or herself long before this point, or even at this point. Such contemplation may lead to continued service, but our sample consisted only of those who ultimately decided to transition out, thus eliminating our ability to interview individuals facing these milestones, but who remained in service.

Unanticipated transitions: Departure under duress

Unanticipated triggers were pervasive among our sample, and stem from unforeseen events such as a medical injury/issue, disciplinary action, institutional constraints or even personal/family circumstances. 34% of our sample (N = 12) left the military because of an unanticipated trigger. In these instances, the transition was forced on them or lead individuals to leave the military against their desires to stay in. Tessa’s 13 years of service in the Army came to an abrupt end when she could not come to an agreement with her ex-husband on a family care plan for her son ahead of a unit deployment. Disciplinary actions led Jameson, an enlisted Navy Corpsman, to a rapid decision to get out. After signing a disciplinary counseling letter Jameson realized he was done, a rapid departure from his ideal vision for his military service, “I fought to go to Afghanistan. I love my country. I love the Navy. I wanted to do 20 years as a SEAL. This is my shit. Like I love this stuff. But [my command] put me in a place where I can’t succeed” recounting his discontent about the situation. For some, an unanticipated exit comes when institutional demands become incompatible with one’s personal priorities or values leading to unresolvable conflicts. While these cases seem similar to anticipatable transitions, timing and intensity of conflict differentiated them. As a drastic deviation from expected career plans in the military, they leave little time for preparing for their next civilian job or career. A latent heart condition halted Brad’s career progression in the Army, news that he described as soul crushing:

It was just like all of a sudden here I am busting my ass, and I’m at ten and a half year mark or ten year mark at that time. And just like, what the frack? … I had every intention – I had my life pretty much planned out. Like retire at 20 years and by then I’ll have my bachelor’s, if not my master’s. And then I’d get out, work a civilian job and then I get out and have two retirement checks … it was one of those things, I had my life pretty much planned out and how things were going to go. And all of a sudden a curve ball gets tossed in there.

For servicemembers like Brad, an unanticipated transition often comes with concurrent stressors, such as medical problems that further complicate their transition.

Planning for transition: Anticipating and preparing for civilian life

Individuals varied substantially in expected dates of military exit and when they began explicitly planning for that exit, and therefore they varied in how long they had to prepare for the transition to civilian life and how they approached the process of planning. For servicemembers using the military to facilitate other personal or professional goals, exit from the military was already part of a long-term plan. Other servicemembers, especially those retiring after more than 20 years, often expressed that initially they never anticipated staying in the military for a career, but the longer they stayed in, the less they considered leaving. As a result, they did not think much about planning for post-military life once they decided to make the military a long-term career. Even among similar kinds of servicemembers (eg. junior enlisted personnel, officers, and retirees) the length of planning for exit varied widely.

We categorized our respondents into three types of planners based on how early and how long they were planning for their transition. Pre-planners (45%) planned for their transition before any explicit date has been set for their exit. In fact, they may have been serving longer than desired only because of a service obligation and the decision to separate was part of a longer-term plan. For pre-planners, transition planning was an ongoing process motivated by internal aspirations and desires rather than any external timeline. These individuals most closely fit the ideal-type descriptions of role exiters and voluntary job changers in prior literature (Ebaugh, 1988; Lee & Mitchell, 1994). Timed planners (40%) began planning for transition and post-transition life only once they knew they would be leaving the military and they all experienced either and anticipatable or unanticipated transition. The length of time spent planning the transition varied for this group depending on how far in advance they knew they would be leaving. The third group, comprising only 8% of our sample, did no advanced planning (non-planners) while still on active duty. They typically started their planning for civilian life during their terminal leave or after they had already left the military. These servicemembers may have had vague ideas about their next steps but waited to specify their plans or take action until the very end of their time in the military.

We analyzed the relationship between a servicemember’s exiting circumstances and the type of planner they were to assess how they correlated with successful post-service outcomes. In defining a “successful” transition, we used a two-part approach. First, we identified whether servicemembers met their own stated goals for their transition, identified during their first interview. Second, we coded for successful outcomes by noting whether they were able to find stable employment or enroll in higher education within 3 months of their separation date. Using these markers, we examined the interaction between exit triggers and planning type in relation to successful transition pathways. Overall, we found greater variation between planning types than by servicemember’s exiting circumstances, with pre-planners and timed planners more successful in moving back to civilian life, even when they faced an unanticipated transition. Notably, all of those with an anticipated transition were pre-planners who planned for their transition long before it became a reality. 30% of our sample fell within this transition scenario of a completely voluntarily, long-planned separation process. For most transitioning servicemembers however, their path out of the military was more often due to unanticipated circumstances or structured by service-related decision points, and planning occurred in a much narrower time frame.

Pre-planners

Pre-planners were the most successful in meeting their own goals and finding their next steps in the civilian world regardless of the transition trigger. Even though pre-planning servicemembers did not always meet the goals they set for themselves, they typically found stable employment outcomes or enrolled in higher education within 3 months of their separation from the military. Nearly 100% of pre-planners had a successful transition across all three exiting circumstances and almost 2/3rds of pre-planners met their own personal goals for their transition across each exit type.

The majority (63%) of pre-planners experienced an anticipated transition. This group were all short-timers, typically serving between 3 and 8 years, who did not make plans for a career in the military. They had been in constant evaluation of how their military service fit with their broader life goals with the military serving a specific, limited purpose in their goals. Liam, an enlisted Soldier who served 3 years, joined the Army for the education benefits. “I decided to go into the Army so I could finish school. I got my associates degree and I didn’t want to go into debt getting my bachelor’s, so I went to the Army and that’s where I am now. I fulfilled my three years. I’m getting ready to go back to school, finish my bachelor’s, maybe my master’s in business administration.” Liam had been preparing for his transition to higher education since the day he transitioned into the military.

Pre-planners with an anticipatable exit were all retirees. They served a career in the military but had been planning their post-service life before they had a timetable to retire. Marco, an enlisted Army retiree, and his wife knew that retirement was possible, but he stayed in as long as the military assignments were agreeable for his family. Without a specific timetable for transition, Marco and his wife began saving for the transition, eventually stashing away 18 months’ worth of savings to buffer a post-retirement job search period.

Servicemembers who actively think about their transition well before it happens have the opportunity to research opportunities, narrow their focus, and build network connections over a longer period of time – to engage in anticipatory socialization. This allows servicemembers’ to use the final months or years of their active-duty service to execute more concrete plans that capitalize on programs, courses, and other opportunities offered to military personnel (like structured internships) rather than using their last months of military income and benefits still in the anticipatory socialization phase of exploring or imagining what is possible. This is especially important for servicemembers looking to move into new industries or professions unrelated to their job in the military, or those who are unexpectedly separated from service, and who may require more anticipatory socialization into a new identity.

Matthew’s retirement plans were unexpectedly fast-tracked due to his wife’s car accident and her subsequent health issues, retiring a few years earlier than he originally wanted to. However, early in his military career he began planning for his post-service civilian life. While working on his bachelor’s degree he discovered he had a passion for working in criminal justice. He switched his MOS (military occupation) halfway through his military service (with the goal of building transferable skills) and completed a master’s degree while on active duty. These career preparations provided a solid plan to execute even though the timing of his retirement was unanticipated.

Timed planners

Timed planners began planning only once they knew their separation was imminent. Consequently, the timeline of these servicemembers’ transition planning varied from two years to three months before separation. The timed planners in our sample were split evenly between those with anticipatable and unanticipated transition triggers. While nearly 75% of timed planners experienced an objectively successful transition, less than half met their stated goals. Those with unanticipated exits due to medical separations often have a long lead time (1–2 years) when they know they are being separated but they remain on active-duty for medical care or recovery purposes, which provided greater time for planning, and thus for anticipatory socialization, goal setting, and realization of stated goals.

Timed planners succeeded in their post-transition goals for a few specific reasons. First, they capitalized on transferable skills, especially in jobs adjacent to the Department of Defense rather than seeking to move into completely new industries or occupations. Ernie retired after 22 years in the Navy and despite wanting to branch out, he decided to work as a civilian contractor in a job similar to his enlisted MOS. The next business day after his retirement ceremony he went to work as a civilian in the same building where had been working while on active duty. Timed planners also benefitted from targeted military employment programs. After 7.5 years in the Navy, Claire decided not to re-enlist. She used two internship programs as anticipatory socialization to gain experience and identify what she wanted to pursue for civilian work. Peter left the military after failing to be selected for special forces which altered his vision for his military career past his service obligation. A paid corporate internship program designed for transitioning service members offered a way to break into the finance industry. He credited the program for a successful transition, saying “I wouldn’t be here. I wouldn’t be in the job if I hadn’t been in the military, flat out. I wouldn’t have gotten the offer. None of the transition [into this industry] would’ve happened if I had not been in the military.” Formal programs like these for transitioning military serve to facilitate and short cut what usually happens via anticipatory socialization by individuals by providing pre-structured anticipatory socialization experiences for them.

Timed planners who did not find immediate success typically had more compressed timeline for exit, they waivered about re-enlisting/staying at anticipatable transition points, or they had significant concurrent stressors. These circumstances led to little to no anticipatory socialization to generate a realistic, actionable transition plan in advance of separation. Jameson, the Navy corpsman who, left the military quickly within 3–4 months after disciplinary action, wanted to build on his medical skills to pursue a bachelor’s degree in nursing, but an unplanned pregnancy with his girlfriend and a lagging decision from the nursing program he applied to shifted his priority to just making money. Samuel and his wife waivered back and forth about whether they should actually leave the Marine Corps. They remained worried about leaving secure, stable employment even though they had made the decision to not re-enlist a year earlier. This indecision continued past our first interview and it took 5 months of unemployment before he found a temporary internship in a different state from where his wife and children were residing. His family experienced significant financial trouble during his period of unemployment, in part because their wavering about the transition as it was happening absorbed the energy and focus needed to plan and prepare for the impending separation from the military.

Non-planners

The final category of servicemembers did not plan for the transition and found little of the success they expected. These servicemembers typically waited until their final months (or less) on active duty while on terminal leave, to start their job search or find higher education options. While only three servicemembers fell into the category, all had lengthy service records – from 16 years to 22 years on active-duty. There was very little difference between those who had an anticipatable or unanticipated transition and they consistently had the worst post-service outcomes within our sample. Non-planners suffered by overestimating the value of their skills, the transferability of their military experience, and the benefit of their status as Veterans. They had a false confidence and unrealistic expectations going into their transition that made advanced planning seem unnecessary. With little anticipatory socialization or preparation, they lacked important knowledge about the civilian labor market and typically only used the formal DoD sources of support for the transition such as the military’s transition course prior to their exit.

Alexander was a Marine Corps pilot retiring after 22 years. Having significant leadership experience in the military, he wanted to become a CEO or COO of a civilian company. Tired of defense-related work, he tried to break into a new industry but had trouble getting a formal interview after reporting he did over 60 informational interviews. Throughout his initial interview it was clear that he had trouble contextualizing the significance of his experiences in the military and how they might fit within a civilian environment. Alexander said:

If I compare it to what I’ve done … the flying aside, nobody, I mean that just doesn’t really compare and I understand that. So I wouldn’t even include that in the conversation but leadership-wise and things like that I don’t think anybody I know that hasn’t been in the military has had the responsibilities, quite frankly.

Alexander’s unrealistic expectations about the value of his military leadership experiences led to a lack of appropriate planning that left him still scrambling to find a job months after he retired from the military. Servicemembers who did not plan for their transition entered their job search unaware of labor market realities, causing further delays in finding any position, much less a position befitting their expectations, after they left the military. Alexander thought conducting informational interviews was planning for his transition, but he did not seem to understand their purpose – to learn new information about a career in order to effectively plan for how to enter it, and at what level.

This led to a lack of specificity in the job search. Alexander was looking to lead in “biotech, biomed, healthcare, finance, life insurance … you name it.” It was difficult for him to gain traction in any one industry because he hadn’t taken the time to understand the vast differences across them, (mistakenly) believing his military leadership experience would transcend industry differences. Ryan served 16 years in the Marine Corps before being medically separated. He had vague ideas about what he wanted to do after the military, such as become a skydiver or own a coffee shop, but he did not plan for work or education after the military because he felt too burned out from his service saying “whatever’s going to happen is going to happen. I don’t think I’ll have an issue getting into school [if I wanted to].” Doug, an Air Force retiree, said that he didn’t know what he wanted to do next. In his initial interview during his terminal leave period, he said that he knew he wanted to use his degree in business management and work in a professional work atmosphere that wasn’t retail or food related but that was the only specific criteria he had. It took him 10 months before his first job offer came through to work for the Department of Veteran Affairs.

In summary, whereas pre-planners or timed planners front-loaded their transition process, using their time still on active-duty to research their options to build concrete, actionable plans, non-planners’ transition started after they left the military significantly delaying their ability to move into civilian roles. Those who did not plan for their transition at all were particularly vulnerable to periods of unemployment. Non-planners and the less successful timed planners both seemed to not make it out of the initial anticipatory socialization stage where they engaged in learning about themselves and what they wanted to become before leaving the military. They simply didn’t begin early enough or tried to short-circuit that step and continued to bounce around between alternatives without committing. This typically resulted from unrealistic expectations that never quite leveled or from remaining somewhat ambivalent about the separation. These two dynamics relate to the challenge presented by a strong military identity in engaging in effective preparation for military exit.

Military identity

Many of those we interviewed expressed strong sense of self-image and self-esteem deriving from their military service. They routinely come to a new understanding of themselves and society through military experiences that were foundational to instituting a strong military identity. Jameson described, “It made a man out of me. I have a different air and confidence about me. I know that I can accomplish anything. I know that I can get any response I want from any person I want.” Jameson’s comments on the fundamental changes he experienced through service were echoed by many servicemembers who felt similarly that they became who they are today as a consequence of serving, and their self-concept was rooted in their military service.

Those who do not have a strong military identity represent cases where military socialization, from the perspective of the institution, seemingly failed. Yet these individuals tend to show the most successful post-service outcomes. For them, military service was part of a strategic plan to achieve decidedly nonmilitary life goals and their time in service did not reduce the prioritization of these civilian goals.1 Anticipatory socialization for a future civilian career goal competes with ongoing institutional military socialization that is designed to be “greedy” of commitment if not identity to maximize loyalty and value to the military institution (Coser, 1974; Segal, 1986). In our sample, half of interviewed individuals without a strong military identity had joined the military explicitly for the GI Bill and had transitioned straight into education rather than the workforce. For them, their affiliation with the military institution served other personal goals, therefore their military identity was temporary at best, and typically never developed at all.

Those with relatively stronger military identities had served for long careers or had expected to have long military careers that were cut short unexpectedly. Future planning more often centered on how to maintain military career success rather than how to set up civilian career success after service. Some presumed the exclusive focus on military career success would also lead to civilian career success, anticipating that their military skills and experiences would be immediately transferable and valuable in civilian sectors. As a result, individuals with stronger military identities were more likely to be timed or non-planners, considering post-military life only when it became necessary as an impending reality. Individuals who had developed a strong military identity also experienced ambivalence about decisions to leave the military, sometimes delaying their planning process. Their commitment to the institution and to their identity as a valuable member to it made it difficult to fully engage in anticipatory socialization, envisioning a new identity, and planning for a new reality. The few non-planners among our sample all had relatively strong military identities and shared a sense that their military experience and Veteran status put them at a unique and decided advantage compared to civilians, and therefore felt little planning for the transition was required. However, contact with the reality of the labor market over time typically led to a leveling of expectations, similar to the experiences of earlier generations of military retirees (Biderman, 1964).

Alexander, one of the non-planners described earlier, exemplified how a strong military identity got in the way of fully envisioning himself as a civilian. He was a pilot in the Marine Corps retiring after more than 20 years of service. He had general ideas about wanting to move away from the defense industry and be a C-suite leader of an organization. He described himself as “civilianizing,” describing packing up his uniforms and getting them out of the house as “closing a book and putting it on a shelf never to be read again.” He did over 60 informational interviews leading up to his transition, seeming to suggest a robust process of anticipatory socialization. But he was unaware how his strong military identity prevented him from seeing the realistic value of his service to civilian industries. Rather than treating informational interviews as a way to learn more about candidate civilian careers (he had be wide open to a variety of possibilities) to narrow in on a new career goal, he seemed to believe they should short-cut the usual hiring process and operate as a candidate-initiated job interview. He became frustrated that his leadership experience wasn’t being recognized and rewarded as he expected with job offers during these informational interviews, He clearly did not appreciate the disadvantage he might face trying to transfer across industries as a pilot. “ … all the informational interviews … and to hear we don’t hire leaders …, tells me right there that they don’t know what you’ve done in the military. I say I’m a pilot but I also immediately tell them most of my time is on the ground obviously. You’re doing something, and by the way I’ve never been trained for any of them, and I’ve been successful in all of them and I think you could say that of any military member anywhere. Because though people are like ‘Oh, they’re a generalist’, I think that’s a good thing and I think companies need that.” He spoke of his service as an Executive Officer (XO) in the same context as CEOs and COOs, suggesting he saw these roles as comparable despite signals from his informational interviewing and civilian job search process that they were not. Planning for him just meant making contacts, assuming they would lead to jobs, rather than truly researching and learning about specific jobs and what they required, and beginning to align himself with the values, norms, and expectations in a new field. After eventually landing a project management role in the defense industry, a step down from what he had expected, he acknowledged, “I was over-confident. Because some of the people I was dealing with, it was like, ‘how would somebody not hire you?’” Nearly a year after separating from the military, Alexander still had a hard time reconciling that the people he served with might not be seen as ideal hires in the civilian world. Prior research is consistent with Alexander’s experience; many long-serving military Veterans continue to identify themselves as “military,” unable to shake the old identity years after exit (Yanos, 2004). Alexander, like many Veterans, had a hard time shifting his reference group away from the military, and as a result, failed to understand that the status he enjoyed within the military culture as a Marine, a pilot, and a career officer does not transfer to the civilian world.

Implications for military practice

Our findings confirm prior research that exit triggers, identity, and planning play important roles in transition experiences and outcomes, and they add nuance to this prior work. First, we identify how the highly structured military career invites ongoing reflection about retention or separation by providing numerous points in a career for decision making. We build on Scholssberg’s theory and call these “anticipatable” transitions because military members understand these as career milestones at which they must decide to stay or leave military service. Second, we show how military identity shapes transitions because it affects the timing and nature of planning behaviors. Planning (or lack thereof) is deeply intertwined with one’s military identity. While early planning is associated with better post-transition outcomes, it is also associated with relatively weaker military identity according to our findings. Efforts to encourage earlier planning for military exit intended may be well-intentioned and well-suited to improving post-transition outcomes. However, early and ongoing engagement with post-military career goals and planning may also facilitate a reconsideration of one’s military identity by encouraging anticipatory socialization into alternate, nonmilitary roles, and therefore reduce one’s commitment to a military career. Thus, there is a potential conflict between optimal preparation for post-military life and military commitment and retention that operates through military identity.

We see two recent changes, to the formal transition assistance programs and to the retirement system, that bring our concern about these tensions to the foreground. First, the evolving transition programs mandated for transitioning servicemembers (e.g. the former Transition GPS curriculum, or the new TAP program) clearly emphasize the importance of planning for transitioning servicemembers (Department of Defense, 2018b). Although our research was conducted during the transition to a now outdated TAP curriculum, we note that the use or nonuse of TAP wasn’t a differentiator of outcomes because all our participants used some services. The latest TAP program (Department of Defense, 2020) is intended to commence as early as 24 months, for those retiring, and at least 12 months for others before separation. This is a good step to encourage early planning, but 12–24 months may not actually be long enough.

Our findings suggest those who engage in a longer planning process do experience better post-transition outcomes. Evolving TAP programming has recognized the importance of early preparation for transition. To encourage earlier engagement in career planning, the Military Lifecycle (MLC) model laid out an idealized model of integrated career planning throughout the military career in which servicemembers construct an individual development plan (IDP) at entry and continually update and revise this plan throughout the career (Department of Defense, 2018a). The IDP is intended to encourage members to envision post-military career goals and to engage in early exploration of nonmilitary careers and their requisite skills. In this way, servicemembers can work to align their military career and civilian career goals in an ongoing process. One of our participants, Matthew, exemplified this approach. He investigated civilian opportunities early in his military career, and changed his military occupational specialty to align with his post-military goals. The ideal is to “enable transition to become a well-planned, organized progression of skill building and career readiness preparation” (Department of Defense, 2018a). These goals are laudable and most likely would improve transition outcomes if the model is appropriately followed by more servicemembers. It remains unclear how well the MLC model is incorporated and followed in reality, whether under past or current transition programming. However, on the basis of our findings about how strength of military identity shapes transition planning, the MLC model may conflict with dominant practices of military institutional socialization and norms that encourage the development of a strong military institutional identity, especially in the combat arms. To the extent that effective planning encourages if not requires some degree of anticipatory socialization, the MLC model has the potential to encourage early exit, and/or stymie the development of strong military identity. Essentially, the MLC model returns to the concerns raised by Moskos in the transition to an all-volunteer force, that the military was changing from an institution to an occupation (Moskos, 1977). By emphasizing post-military occupational goals early and repeatedly over the military career, the MLC model may push the military further along the continuum toward the occupational.

This did not happen to our participant Matthew though; he was able to simultaneously hold multiple identities of active duty soldier and future civilian professional. He factored in post-military careers early in his military service, he did continue to serve albeit in a different military occupation. He only left earlier than expected because of family circumstances. And it may well be that early planning for civilian work actually encourages retention, as people realize they are relatively well-compensated with relatively job stability. DoD should encourage further study of how to optimally encourage pre-planning for civilian careers, without harming retention in specific military occupations, or service overall, given that different military occupations have different degrees of transferability to the civilian occupational structure. We suggest that as these programs evolve, they pay close attention to how they affect retention and military identity.

Second, the relaxation of the requirement to serve all of 20 years to access pension retirement funds under the blended retirement program will likely alter how individuals experience military transition and planning. Blended retirement allows individuals to earn and retain retirement benefits before the twenty-year mark, reducing the centrality of the 20-year mark as a transition trigger point (Department of Defense, 2018c). Under blended retirement the most consequential anticipatable transition – the 20-year mark – is no longer as pivotal. Now, retention decisions may be less anticipatable, and spread out more evenly across the military life course. Individuals will be faced with a more continuous decision-making process. In tandem with the MLC model, blended retirement has the potential to encourage early exploration of and anticipatory socialization into nonmilitary occupational roles, possibly weakening a military identity and organizational commitment.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviews and editor for their helpful comments and suggestions. We are grateful for early assistance from Phil Lennon, and for early comments and feedback from Nathan Ainspan.

Appendix. Interview guides

Pre-separation Interview

Where did they come from?

Tell me a little bit about yourself.

Where are you from?

Why did you join the military?

When you joined, what did you expect to get out of your experience in the military?

Describe the job that you are currently doing.

What kinds of things have you done while you’ve been in the military?

What type of training did you get?

Did you take any nonmilitary classes (e.g. college or technical training)?

Where are they now?

How has the military changed you?

Why are you leaving the (Navy/Marine Corps/Army)?

What are your friends from high school doing now?

What do you think about what they are doing compared to what you’ve been doing?

How do they get out?

Walk me through what you have to do to process out.

Have you done any of those things yet? If not, when do you expect to?

Was (or is) your command supportive of your needs in transitioning out? (i.e. did they allow you time off to fulfill requirements, etc)

What are you planning to do when you get out? What led you to that interest?

Are you worried about finding a job/getting into a good school? Why or why not? Prompt for more here

How do networks apply in their plans?

Have you discussed getting out with your friends/family/spouse/children? What kinds of things do they say about your getting out? What about those who you currently work with or other friends you have served with?

Who has been helpful in preparing you to transition? How long have you known them?

Are any of your friends getting out? What do they plan to do?

What about friends who have already gotten out? What have they been doing? How’s it going for them? Has this had any impact on your leaving?

Their expectations and perceptions

How do you think civilian employers perceive Veterans?

What about civilians in general – what do they think about Veterans?

What kind of job do you expect to get?

Tell me a little more about that: Why do you expect to be starting there?

What kind of salary do you expect to earn when you start out?

How does your training apply to the civilian world?

Does your military experience make you competitive for “good” civilian jobs?

How does the media portray Veterans?

Does it affect how people think about Veterans?

Does it affect how they treat them?

Transition

Is there any way to make the transition easy? Easier?

Have you gone through any official transition assistance programs yet?

What resources would be/have been helpful in your transition process?

- What about (each of below), follow-up with a question about WHEN they should receive information about X.:

- One-on-one career counseling?

- Training on how to write a resume?

- Training on how to interview for a job?

- Training on how to find the jobs you’re interested in?

- Information about VA or other benefits?

- Personal finance training?

- Any others?

What resources do you wish you had?

- (For Officers):

- Have you been in charge of any enlisted service members as they transitioned out? Tell me more about that.

- What do you think differentiates successful vs. not successful transitions for those enlisted service members?

What can and what should civilians do to help folks transition?

If you could tell people one thing about your experience in the [Army/Marine Corps/AF/NAVY], what would it be?

Would you recommend enlisting (or military service) to your kids?

Follow-Up Interview, Post-Separation

PREPARING TO LEAVE THE MILITARY

When did you officially leave active duty?

-

The last time we spoke, we briefly discussed your thoughts around your decision to leave the military …

Can you help refresh my memory about when you first considered leaving active duty?

-

In those early stages, what were you thinking you might do after you got out? [Listen/probe for the tier of what their goals. For example, if they say get a job in manufacturing, are they thinking this is an entry-level job or a managerial position? If it is school, what types of schools were on their radar?]

Where did you get that idea? Why [school; work] over [school; work]?