ABSTRACT

The concept of moral injury, referring to the psychological impact of having one’s moral expectations and beliefs violated, is gaining a firm place in research on military trauma. Yet, although moral injury has the recognized potential to extend the understanding of trauma beyond the individualizing and pathologizing focus of the clinical realm, most studies nevertheless focus on clinical assessment, diagnosis and treatment. This review aims to contribute to a better understanding of contextual dimensions of moral injury. To this end, it complements current theory on moral injury with a systematic review of literature relevant to contextual factors in moral injury. It draws together insights from psychology, philosophy, theology and social sciences into spiritual/existential, organizational, political and societal dimensions of moral injury. Thus an interdisciplinary theoretical foundation is created for context-sensitive research and interventions.

KEYWORDS: Moral injury, PTSD, trauma, interdisciplinary, context, soldiers

What is the public significance of this article?—This review advances the concept of moral injury, which refers to the psychological impact of violations of one’s moral expectations and beliefs. By means of a systematic literature review, it integrates novel insights into the nature of moral injury and appropriate interventions for moral injury. Doing so, it develops an interdisciplinary theoretical foundation for context-sensitive research and interventions.

“You can’t choose between one human life and another. So, you always do the wrong thing. (…) It was one big mess. (…) There’s pretty rules of engagement, and then there’s reality … ” These are the words of a former soldier relating the event that still chokes him up today. At the end of his deployment, a UN-protected area fell to one of the local belligerent parties, driving masses of refugees to the compound where the soldiers were stationed, pleading for protection. As there were too many of them, he was forced to choose “between one human life and another.” To this day, he feels profoundly guilty for having failed to help people and furious for having been sent on a “mission impossible” by the military organization, his government and the United Nations. In other words, he suffers from distress resulting from moral conflict in which the wider context plays an important role.

A significant proportion of soldiers worldwide develop feelings of shame, guilt and/or betrayal and anger as a result of their deployment experience, with estimates ranging from approximately 5 to 25% (Bryan et al., 2016; Currier et al., 2015; Gray & Nash, 2017; Wisco et al., 2017). A little more than a decade ago, military psychiatrists and psychologists introduced the concept of moral injury to adequately capture such moral conflict-colored suffering. “Moral injury” refers to the profound and persistent psychological distress that people may develop when their moral expectations and beliefs are violated by their own or other people’s actions (Litz et al., 2009; Shay, 2014). The reason for the introduction of this concept was a growing dissatisfaction with dominant theory and treatment modules regarding post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which were criticized for giving marginal attention to the potential moral dimensions of military distress (DePrince & Freyd, 2002; Drescher et al., 2011; Litz et al., 2009).

The concept of moral injury has been praised for pushing the understanding of trauma toward the inclusion of ethical and sociological perspectives (Carey & Hodgson, 2018; Molendijk, 2021). For instance, while trauma-related guilt and anger often tend to be either overlooked or understood as the result of “distorted” cognitions in current PTSD models (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 272), the concept of moral injury incorporates psychodynamic, philosophical and theological perspectives on guilt and anger as possibly reasonable and appropriate, and accordingly as requiring a focus on (self-)forgiveness rather than de-responsibilization (Kinghorn, 2012; Shay, 2014). In relation to this, while the focus of PTSD models often lies on internal psychological processes of the suffering soldier, and on interpersonal processes at most, studies on moral injury inspired by anthropology and other social sciences point out that soldiers’ problems are also inextricably linked to wider contextual factors such as military culture, political mandate and societal attitudes (Farnsworth, 2014; Hautzinger & Scandlyn, 2013; Shay, 2014).

To date, only a handful of studies have explicitly examined contextual dimensions of moral injury. At the same time, there is a growing body of literature that implicitly addresses this issue. This article offers a systematic review of this literature, that is, of studies relevant to contextual factors in moral injury. Contextual factors can be defined as the circumstances that, in interaction with each other and with individual factors, shape the development of moral injury, and in terms of which moral injury can thus be more fully understood. This article starts with some more background on the concept and phenomenon of moral injury. Subsequently, it evaluates existing knowledge about the role of context in moral injury, particularly insights into the causes and consequences of moral injury and considerations on appropriate interventions for moral injury. Finally, it discusses key insights, gaps and questions emerging from this review. In doing so, it develops both an interdisciplinary theoretical foundation and a research agenda for context-sensitive research on moral injury and trauma in general.

The concept of moral injury

Since the introduction of a first conceptual model (Litz et al., 2009), the concept of moral injury has become well-known in military contexts, resonating with soldiers, military health care professionals and military researchers alike (Boudreau, 2011; Drescher et al., 2011). This is no coincidence: military practice constitutes preeminent conditions for morally critical situations that engender serious distress. Soldiers may have to use and witness violence in dangerous circumstances while embodying multiple moral commitments. They are instruments of the state who must adhere to political norms and legal rules, but also remain moral agents with personal values. Moreover, even when they agree with all they are ordered to do, they remain members of a society which makes violence taboo. In extreme cases, they may face tragic dilemmas which force them to choose between two evils, leaving them inevitably with “dirty hands,” no matter their choice.

In a recent survey conducted among US combat veterans, 10.8% reported engagement in moral transgressions, 25.5% reported transgressions by others, and 25.5% reported feelings of betrayal (Wisco et al., 2017). More specifically, many soldiers have reported experiences of injuring or killing others, failing to prevent the suffering of colleagues or civilians, and feeling betrayed by a leader or other trusted authority (Griffin et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2017; Yeterian et al., 2019). Thematically, moral dilemmas, moral disengagement and senselessness are recurring themes in the stories of morally injured veterans (Molendijk, 2018b). Not just combat operations but also peacekeeping missions can give rise to moral injury. For example, in a study among Dutch peacekeepers (Rietveld, 2009) more than 25% reported feelings of guilt about their deployment experience. One third of this 25% said to experience psychological distress due to guilt, in line with the abovementioned estimates of 5 to 25% of soldiers developing of feelings of shame, guilt and/or betrayal and anger.

It is in light of these findings that psychologists themselves have voiced surprise about the fact that current psychological models of PTSD direct relatively little attention to moral emotions such as guilt (DePrince & Freyd, 2002; Litz et al., 2009). Also, they have critically observed that when practitioners do address feelings of guilt and anger they often tend to approach them as the result of irrational thoughts and faulty logic (Gnaulati, 2019; Litz et al., 2009). Failing to allow space for the potential legitimacy of blaming oneself and/or others, some argue, may be an important reason for the high number of veterans who drop out of or do not actually recover after PTSD treatment (Finlay, 2015; Gnaulati, 2019). This argument is supported by the finding that guilt is one of the most common residual symptoms following treatment for PTSD, and that especially the belief that the person’s actions during the traumatic event were simply unjustifiable often remained problematic for sufferers (Larsen et al., 2019).

Allowing space for the potential validity of a soldier’s feelings of guilt and anger requires acknowledging the potential role of contextual factors in moral injury. However, most current studies on moral injury – while simultaneously asserting that moral injury is not an official diagnosis – are currently working on developing workable clinical models for moral injury, seeking to facilitate the clinical assessment and diagnosis of moral injury and its relation to PTSD, and developing therapies for moral injury (see e.g., the reviews of Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016; Griffin et al., 2019; Koenig et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2018). Consequently, and probably unintentionally as many of these studies explicitly define moral injury as distinct from PTSD, the concept of moral injury risks turning into an individual-focused and pathologizing construct which explains trauma only in terms of intra-psychic and inter-personal processes, and gives sufferers the status of patients with mental disorders (Kinghorn, 2012; Scandlyn & Hautzinger, 2014). Yet, to reiterate, the very reason for moral injury’s introduction was that current trauma literature and treatment was found to pay too little attention to ethical and social dimensions of military suffering (Griffin et al., 2019; Koenig et al., 2019; Litz et al., 2009; Shay, 1994). This article goes beyond criticizing individualizing tendencies of current moral injury research and offers a systematic review of literature relevant to these dimensions.

Methods

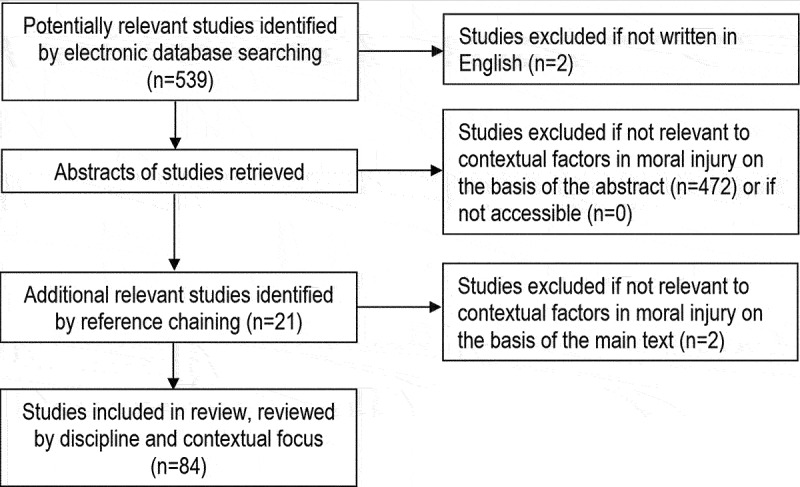

For the systematic review, Noblit and Hare’s (1988) review strategy was adopted, which is specifically intended for systematically integrating quantitative and qualitative research from different disciplines (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006). The strategy starts with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). It then is followed by a more organic search of the literature by means of manual backwards reference chaining, meaning that in the identified literature references are followed that appear potentially relevant to the review goal (Noblit & Hare, 1988). Notably, the emphasis of this strategy lies on the analysis of studies in terms of their contribution to theory rather than on aggregating empirical data. As such, this strategy makes it possible to identify all studies relevant to the review objective and amalgamate them into a comprehensive theoretical framework (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006).The objective of the present review was to synthesize literature on the role of context in moral injury and identify key insights and remaining gaps and questions in doing so. For this purpose, parallel literature searches were conducted in PsycINFO and Web of Science using the key terms “moral*” and “injur*” (e.g., moral injury, morally injurious, morally injured). These databases were selected for their quality and depth of coverage of psychological, philosophical, theological and social science literature. Figure 1 displays a flow diagram showing how relevant studies were identified. All relevant books, book chapters and peer-reviewed articles in English were retained. Since only a handful studies turned out to explicitly focus on contextual factors, the more open criterion of studies potentially relevant to the role of context in moral injury was employed. For instance, articles on the relation between moral injury and an individual’s world views were also included. PsycINFO returned 323 total results, 41 of which met the inclusion criteria. Web of Science returned 216 results, 24 of which met the inclusion criteria and had not been previously retrieved. Next, an additional search was conducted by means of reference chaining, to find studies that were not identified through a database search with the terms “moral*” and “injur*” but did pertain to contextual factors in moral injury. Following this search, an additional 19 studies were selected. All studies were accessible. In total, 84 studies were reviewed.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the process of inclusion and exclusion of studies from the review.

The analysis of the studies focused on their theoretical contribution. Specifically, it focused on the different ways in which the literature conceptualized the nature and causes of moral injury and proposed answers regarding moral injury’s prevention. In this analysis, different disciplinary perspectives and focal points were identified and categorized. The literature comprised studies from the fields of philosophy, theology and social sciences, with some exceptions coming from a psychological (psychoanalytically inspired) perspective (Bowker & Levine, 2016). Psychodynamic, philosophical and theological studies often had similar focal points, including the role of (religious) world views and assumptions and rituals in moral injury. In doing so, these studies often also indirectly addressed the role of organizational and societal contexts. Sociological, anthropological and political science literature usually focused more explicitly on either or both these contexts. Given the overlapping focal points of the different disciplines, the results of the review were categorized under these focal points, namely Spiritual/existential, Organizational and Political/societal dimensions. Studies focusing on the concept rather than the phenomenon of moral injury were categorized under the separate category Definition and conceptualization of moral injury. (Figure 1)

Results: Dimensions of moral injury

Below, general insights and concerns regarding the definition and conceptualization of moral injury are first discussed. Next, literature is reviewed on Spiritual/existential, Organizational and Political/societal dimensions of moral injury, with a focus on the literature’s perspectives on the nature and causes of moral injury, and potential answers regarding moral injury’s prevention.

Definition and conceptualization of moral injury

While the concept of moral injury has received growing scholarly attention in recent years, there is no consensual definition of its meaning. A first often-used definition of moral injury is “(a) betrayal of what’s right, (b) by someone who holds legitimate authority (e.g., in the military – a leader), (c) in a high stakes situation (Shay, 2014, p. 182).” This definition has been offered by psychiatrist Shay, one of the first to use the term moral injury in his work on Vietnam veterans (Shay, 1994). A second much-cited description is “the lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioral, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations (Litz et al., 2009, p. 697).” This is the definition of psychologist Litz and his colleagues, who developed the first model of moral injury which fueled research on the concept.

Notwithstanding these definitional differences, most research on moral injury – including psychological and psychiatrist studies – shares the contention that moral injury does not fall squarely into the domain of mental disorder. In the case of moral injury, it is argued, blame of self and others can often be considered fitting and appropriate rather than irrational and misguided (Litz et al., 2009). As is discussed in more detail below, interpretations inspired by psychodynamics, philosophy and theology take this position even a step further, and explain moral injury not only as psychological damage but as painful knowledge about the self and the world (Molendijk, 2018b; Wiinikka-Lydon, 2017), or more concisely, as “lost innocence” (Ramsay, 2019) or “ethical struggle” (Molendijk, 2018b).

Nonetheless, many of these studies proceed by focusing on clinical questions of psychometric assessment, diagnosis and treatment (see e.g., Bryan et al., 2016; Currier et al., 2015; Litz et al., 2009; Yeterian et al., 2019). Therefore, scholars have voiced concern that the concept of moral injury actually risks to distort what it aims to capture. Despite the concept’s de-pathologizing approach, they argue, current research on the concept remains one-dimensionally focused on diagnosis and treatment, unintentionally reducing normative and political questions to individuals’ troubled psyches (Kinghorn, 2012; K. T. MacLeish, 2018). Such criticism is not intended to renounce the concept of moral injury or psychological perspectives on trauma, to the contrary. Most scholars maintain that moral injury is a potentially useful way to represent moral conflict-colored suffering as a multidimensional phenomenon, including but not limited to psychological dimensions (Hodgson & Carey, 2017).

Aiming to comprehensively capture the multiple dimensions of moral injury, theologian Carey and psychologist Hodgson have proposed the following definition.

Moral injury is a trauma related syndrome caused by the physical, psychological, social and spiritual impact of grievous moral transgressions, or violations, of an individual’s deeply-held moral beliefs and/or ethical standards due to: (i) an individual perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about inhumane acts which result in the pain, suffering or death of others, and which fundamentally challenges the moral integrity of an individual, organization or community, and/or (ii) the subsequent experience and feelings of utter betrayal of what is right caused by trusted individuals who hold legitimate authority. (Carey & Hodgson, 2018, p. 2)

This definition draws together the different understandings of moral injury articulated in the above-cited literature, including approaches to moral injury as more than an intra-psychic condition. Therefore, it is this comprehensive definition that seems most useful in research aiming to include contextual dimensions of moral injury.

As a final conceptual remark, it is worth noting that the concept of moral injury is not without controversy. Military representatives for instance, have articulated concerns that the term moral injury implies that soldiers’ problems are a result of unethical conduct (McCloskey, 2011). To avoid this connotation, the US Marine Corps does not use moral injury but the more euphemistic and more individual-focused term inner conflict (Nash & Litz, 2013, p. 368). Also, many researchers leave out Shay’s element of betrayal by legitimate authorities in their definition of moral injury, which is thought to be due to its suggestion of political critique (Hodgson & Carey, 2017). Responses like these show that the moral complexities that the concept of moral injury can potentially uncover, as well as the role of wider social contexts in these complexities, may engender discomfort. At the same time, precisely this discomfort indicates that spiritual/existential, organizational, societal and political dimensions may be relevant to soldiers’ suffering, and that the concept of moral injury has the potential of illuminating this relevance.

Spiritual/existential dimensions

Literature on moral injury from the fields of psychodynamics, philosophy and theology generally focuses on spiritual/existential dimensions of moral injury. Their perspectives offer valuable insights into the complexity of the phenomenon, in particular with respect to the ‘moral’ in “moral injury.” In most cognitive psychological research on moral injury, a person’s moral beliefs tend to be implicitly approached as a rather coherent system (Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016). Most philosophical and theological studies, instead, depict moral beliefs as a complex constellation of potentially competing moral convictions and commitments (Fleming, 2021; Kinghorn, 2012; Molendijk et al., 2018). In line with this, they describe moral injury not only in terms of blame of self and/or others, but also emphasize that morally injurious experiences may bring about (existential) moral confusion, self-doubt and disorientation (Kinghorn, 2012; McCormack & Ell, 2017; Meador & Nieuwsma, 2018; Molendijk, 2018b; Sherman, 2015).

With respect to the etiology of moral injury, studies describe how morally injurious events violate people’s world-views and/or religious beliefs, resulting in loss of trust in themselves and others, loss of religious/spiritual faith and practices, and loss of meaning and purpose in their work and life (Jinkerson, 2016; Koenig et al., 2018; Sullivan & Starnino, 2019). Relatedly, they underscore that moral injury does not manifest itself in a social vacuum but in the context of relationship dynamics. Moral injury, they state, therefore often involves experiences of conflict with others (including manifestations of guilt, shame, betrayal and alienation, and a loss of trust and faith) as well as with the self (inner conflict including confusion, self-doubt and disorientation; Gilligan, 2014; Martin et al., 2017; Yandell, 2019).Regarding potential answers to the problem of moral injury, studies attending to spiritual/existential dimensions stress that moral injury is not necessarily a problem to be fixed, but may also be considered an appropriate response to having been involved in morally critical situations (Kinghorn, 2012), and thus a ‘fact’ rather than a ‘feeling’ (Finlay, 2015). Accordingly, in addition to conventional psychotherapy these studies recommend pastoral/philosophical counseling with an emphasis on making amends and finding (self) forgiveness, as well as socially directed interventions such as community service (Bica, 1999; Fleming, 2021; Griffin et al., 2019; Hodgson & Carey, 2017). Furthermore, many studies point to the potential value of rituals, emphasizing how in earlier times warriors always went through purification and reintegration rituals upon their return from war (see also, Shay, 1994). For today’s times, these studies propose rituals such as symbolic cleansing, “confessing” and collective narrative practice projects (including friendship projects between civilians and veterans; Antal et al., 2019; Denborough, 2021; Drescher et al., 2011; Ramsay, 2019). These rituals, it is worth noting, combine spiritual and social elements; they encourage individuals with moral injury to look both inward and outward, and to find new ways to engage with both the self and the world.

Organizational dimensions

As research on moral injury from the fields of social sciences emphasizes, people always develop their moral beliefs as members of different communities, each having its own values and norms (Molendijk, 2018a). What follows from this is that the moral dimension of moral injury is always social and contextual. This conceptualization complements that of spiritual/existential-focused research, as it explains why and how people hold multiple, potentially competing moral convictions and commitments.

Considering moral injury among soldiers, on which most current research is focused, one relevant social context that comes to mind is the military organization. Although none of the reviewed studies focus specifically on the organizational context of moral injury, some do take it into account. In particular, they describe conflicts between personal and professional moral commitments (Enemark, 2019; Sherman, 2015), the breaking down of untenable occupational moral identities (Bica, 1999) and a sense of betrayal by the organizational leadership (Shay, 1994, 2014). Also, fundamental organizational characteristics are identified as contributing to the risk of moral injury. Inherent to the military organization, for instance, is the paradox that soldiers are supposed to be both willing instruments of violence and morally responsible agents. As a result of this paradox, double-bind messages and dual pressures are exerted on soldiers (Wiinikka-Lydon, 2017). Having to follow orders and mandates versus abiding by personal values seems a particularly complicated issue for military personnel. In addition, there is the value of unity and loyalty to other servicemembers, which may conflict with both orders and personal values (Bradley, 2018).

Existing research on work-related stress in general, moreover, indicates that many more organizational factors may influence the prevalence and manifestations of moral injury. High-risk work situations (Londoño et al., 2012), work role ambiguity (Buijs et al., 2012), institutional silence, denial and cover-ups (Smith & Freyd, 2014), marginalization and harassment (Hosein, 2019) and mental health stigma (Ben-Zeev et al., 2012) have all been identified as contributing to distress, especially in military organizations. These factors all have moral significance, which makes them potentially relevant to moral injury and thus worthy of investigation.

What can organizations do to address and prevent moral injury? To stay with the military context (the only organizational context for which interventions are discussed in the reviewed literature), a range of psychological and spiritual interventions are proposed to implement in organizations to decrease feelings of guilt, shame and betrayal among soldiers. US Major Kilner maintains that military leaders have the obligation to justify military violence to their troops (Kilner, 2010, February 10) and some military resilience trainings encourage soldiers to see their actions as meaningful (Hammer et al., 2013). Other studies, however, warn precisely against such interventions. They argue that to try and ‘impose’ a sense of righteousness and purpose flies in the face of the fact that some events do not allow such an interpretation and that soldiers often feel the need for remorse (K. T. MacLeish, 2018). As scholars have signaled, soldiers struggling with moral conflict may perceive justifications coming from military commanders, psychologists and chaplains, even when well-intentioned, as a form of betrayal, and consequently lose trust and develop a sense of alienation vis-à-vis military, psychological and religious authorities (Bica, 1999; Lifton, 1973). Of note, these scholars do not intend to say that all military practice is immoral, but rather that the chaotic circumstances of war may give rise to tragic dilemmas and other morally compromising situations, and that encouraging soldiers beforehand to see all their actions as justified – rather than acknowledging and allowing remorse for potential transgressions – can be counterproductive.

Political and societal dimensions

If the wider political and societal context is taken into account at all in moral injury research, it is usually only touched upon. Yet, if moral injury is understood as painful knowledge about the self and the world, as scholars have proposed, these contexts are relevant to moral injury. A study on morally injurious events during military missions demonstrates that when conflicts at the political level are not resolved (or only ostensibly through compromises), they will engender moral dilemmas for soldiers on the ground (Molendijk, 2019). Consequently, soldiers may develop feelings of abandonment and betrayal by the political leadership (Bica, 1999; Lifton, 1973; K. MacLeish, 2021; Molendijk, 2019). Regarding society as a whole, soldiers have reported resentment and alienation because of feeling misunderstood by civilians (Ferrajão & Aragão Oliveira, 2016; Worthen & Ahern, 2014). Soldiers have said to perceive both the negative image of perpetrator and positive representations such as victim and hero as misrecognition (Farnsworth, 2014; Molendijk, 2018a; see also, K. MacLeish, 2021). This indicates that distorting caricatures in societal discourses may be perceived as doing injustice to the soldiers’ experience. In engendering experiences of moral transgression and betrayal, they may perpetuate and contribute to moral injuries (Molendijk, 2018a).

Several interventions are proposed for moral injury as resulting from political practices and societal representations. At the macro-level, the just war tradition is mentioned as both a cause of moral injury and a potential solution. The just war tradition comprises moral criteria for military intervention which can be identified in international law and policy. It is called a cause of moral injury due to its potential to justify immoral war endeavors (Meagher, 2014) and a potential solution because it sets preconditions for military intervention and for military conduct in the context of an intervention without falling into pro- or anti-war absolutisms (Kinghorn, 2012). Specifically, research points to the protective value of realistic mandates where the mission’s objectives and operational reality line up, transparent political narratives that correspond with the actual mission motives and goals, and nuanced public debates in which justice is done to the (moral) complexity of military intervention (Molendijk, 2021). At the micro-level, scholars signal the healing value of practices of reconciliation. These practices, it is argued, allow morally injured individuals to translate their distress into meaningful and thus healing action by engaging broader social conditions and policies (Antal et al., 2019; Lifton, 1973; Ramsay, 2019).

At the same time, some studies suggest that moral injury is a fundamental problem of society that can never be completely prevented or resolved. The ways in which societal discourses construct certain understandings of the world inevitably means that deviant experiences and stories (for instance, of certain groups of traumatized veterans) in society are muted (Gilligan, 2014; Honneth, 1997). Thus, it is argued, we all constantly produce and perpetuate moral injury in each other (Wiinikka-Lydon, 2017). Yet, as mentioned, the specific ways in which this may occur is unclear, as the role of political and societal factors in moral injury receives scarce attention in the current literature.

Discussion: Implications for research and practice

The growing body of research on moral injury has offered important insight into the distress that professionals develop when confronted with morally critical situations. Less attention, however, has been given to the role of contextual factors in moral injury. This article reviewed and synthesized the literature that directly or indirectly focuses on context, resulting in the identification of spiritual/existential, organization, political and societal dimensions of moral injury, as well as important questions pertaining to moral injury as a concept. A number of interrelated propositions (or hypotheses) can be drawn from the review results, as well as a number of gaps and questions that still need addressing. The propositions, identified gaps and questions can be read as directions for, and points of attention in, future research.

A contextual understanding of moral injury that includes perspectives from philosophy, theology, and social sciences is vital

Moral injury requires a holistic approach that is able to adequately grasp the multiple dimensions of the phenomenon. This point is emphasized in most research on moral injury (Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016; Griffin et al., 2019; Litz et al., 2009; Williamson et al., 2018), while at the same time it is generally not put into practice. Most current research takes a psychological perspective, and even the studies that do adopt alternative disciplinary perspectives nevertheless tend to take the psychological level as their focus rather than actually taking into account the spiritual/existential, organizational, political or societal level (Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016; Griffin et al., 2019; Litz et al., 2009; Williamson et al., 2018). Consequently, current conceptualizations of moral injury tend to employ too mechanistic interpretations of the moral dimension of moral injury while direction little to no attention to moral injury’s social dimensions. Most current research, for instance, approaches a person’s moral beliefs as a harmonious “code” or “system” that is internal to the person (Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016; Litz et al., 2009). However, as emphasized in the fields of philosophy, theology and social sciences alike, individuals develop their moral beliefs in a variety of social contexts which may conflict with one another (Enemark, 2019; Molendijk, 2018a; Sherman, 2015). As a result, a person’s moral beliefs are not a coherent unity but a constellation of possibly conflicting values.1

The results of this literature review underline that guilt, shame and anger are inherently relational. Guilt and shame are about how one perceives oneself or others through the eyes of one’s community because they stem from moral standards developed as a member of that community, and anger is often related to a loss of trust in one’s community, such as the organization or society (Bica, 1999; Farnsworth et al., 2017; Kinghorn, 2012; Shay, 2014; Sherman, 2015). Accordingly, guilt, shame and anger are often characterized by conflict. Moral injury, in short, overspills the boundaries of mental disorder, giving rise to research and treatment challenges that only an interdisciplinary perspective can adequately address. Insights from other disciplinary fields can complement existing research and in doing so help to capture the multidimensional phenomenon of moral injury.

Moral injury may benefit from perspectives focusing on the spiritual/existential dimension

One line of disciplinary perspectives that are useful for understanding moral injury includes psychodynamic, philosophical and theological perspectives on the spiritual/existential dimension of moral injury. As noted, many studies on moral injury have already integrated the idea that feelings of guilt, shame and anger should not readily be interpreted as the result of distorted cognitions and misplaced judgments, but be considered as possibly appropriate (Kinghorn, 2012; Litz et al., 2009; Shay, 2014). Yet, again, this contention is not always followed through, as indicated for instance, in the fact that different psychological studies propose the method of challenging and thus modifying the patient’s judgments about the traumatic event (Finlay, 2015; Gray et al., 2017). This method is conventional in psychological therapy but, as others argue, may not be the most apt to start with in cases of moral injury (Finlay, 2015; Gray et al., 2017). Therefore, attention is needed to what it concretely means to consider moral injury as having important spiritual/existential dimensions.

To start with, terms such as lost innocence (Ramsay, 2019) or ethical struggle (Molendijk, 2018b), which are philosophical/theological notions that scholars have coined to capture non-pathological aspects of moral injury, may be helpful to consider as sensitizing concepts. Also, psychological studies that have incorporated the philosophical method of Socratic questioning and theologically inspired theme of (self-)forgiveness can offer direction (Gray, Nash, & Litz, 2017; Litz et al., 2009). Finally, literature on ancient purification rituals for returning warriors are insightful, as well as rituals for today’s soldiers, such as symbolic cleansing, “confessing” and collectively producing testimonies of deployment experiences (Antal et al., 2019; Denborough, 2021; Drescher et al., 2011; Ramsay, 2019).

Moral injury may benefit from perspectives focusing on organizational, political, and societal dimensions

As noted, while many studies on moral injury, including psychological studies, emphasize the significance of social relationships in recovering from moral injury, at the same time most studies do not focus on options other than clinical, individual-focused interventions (see e.g., Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016; Griffin et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2018). Even the few studies that propose context-sensitive interventions nevertheless confine the interventions’ focus to the individual veteran. For instance, while some studies propose interventions in which veterans are encouraged to understand their moral injuries in relation to the moral communities of which they are part (such as the armed forces and society), these interventions only involve the veteran in question in dialogue with a practitioner, not said moral communities (Bica, 1999; Farnsworth et al., 2017). Similarly, while studies promoting interventions such as resilience training, community service and “witnessing practices” do call on veterans to engage with their social environment, they do not reflect on whether and how the social environment could engage with veterans (Hammer et al., 2013; Hodgson & Carey, 2017; Ramsay, 2019). Yet, the insights of these studies indicate that in addition to training the individual soldier and treating the individual veteran, interventions should also be sought at the level of the wider social context. At the same time, it seems that existing training and mental health interventions should be carefully evaluated for their appropriateness for moral injury, as there are indications that efforts to promote a sense of righteousness and purpose can actually be counterproductive (Bica, 1999; Eidelson et al., 2011; Lifton, 1973; K. T. MacLeish, 2018). To be able to develop appropriate context-sensitive interventions, comprehensive insight and thus further research is needed into how social context, including the wider sociohistorical context, (may) actually play a role in moral injury.

The prevalence and manifestation of moral injury is related to cultural, material, and structural characteristics of organizations

The few studies discussing organizational dimensions of moral injury point to professional role conflict, leadership failure and structural dilemmas as potential sources of moral injury among soldiers. In addition, as discussed, morally significant factors such as high-risk work situations, work role ambiguity, institutional silence, denial and cover-ups, marginalization and harassment, and mental health stigma may contribute to distress. Relations between these organizational factors and moral injury therefore warrant investigation. Moreover, as suggested by several of the reviewed studies (Ben-Zeev et al., 2012; Bica, 1999; Lifton, 1973; Smith & Freyd, 2014), to properly examine such relations it is important to also take underlying cultural norms and material circumstances into account. To do so, it may be helpful to draw on research in the fields of anthropology and organization studies, which for instance, has shown that the cultural representations prevailing in an organization (Sonenshein, 2007) and the occupational identities internalized by professionals (Leavitt et al., 2012) substantially influence professionals’ moral judgments. Also, it may be worth examining the role of more structural factors such as how work tasks and processes are organized in the emergence of issues such as role conflicts and organizational dilemmas (De Guerre et al., 2008). In relation to this, finally, the role of new technologies in moral injury seems worth investigating. The last decades have seen rapid technological innovations with substantial moral significance. Military and police work, for instance, is ever more affected by digital technologies and robotic automation, for instance, drones and police robots (Coeckelbergh, 2013; Joh, 2016; Ogle et al., 2018). Such developments give rise to new kinds of moral challenges and as such may influence the psychological wellbeing of professionals.

The prevalence and manifestation of moral injury is related to political, and societal factors

Besides organizational dimensions, research suggests that political practices and societal perceptions may play a role in how moral injury develops and manifests itself, in particular in professions such as the military profession, which are highly dependent on political decision-making and public opinion (e.g., Bica, 1999; Ferrajão & Aragão Oliveira, 2016; Lifton, 1973; Molendijk, 2019; Ramsay, 2019). As discussed, political failures and simplistic representations in public debates may engender a sense of perceived political betrayal and societal misrecognition, and in turn make morally injured veterans seek political compensation and societal recognition (Lifton, 1973; Molendijk, 2018a, 2019; Worthen & Ahern, 2014). Considering wider contextual dimensions of moral injury, then, mental disorder related to moral injury – if it should be described in such terms – might in part be approached as a manifestation of political and societal disorder. Further research into the political and societal context of moral injury may help to better understand the specific impact of incidents and structures of injustice, and offer insight into whether and how recognition and reparation foster or perhaps hinder personal and social healing.

Future directions

To summarize the directions for future research offered in the review, first, further research is warranted on the specific ways in which moral beliefs and expectations, and potential conflicts between them, play a role in the onset of moral injury, and how moral injury in turn impacts a person’s moral beliefs and expectations. Second, in addition to such investigation of moral injury’s spiritual/existential dimension, it is worth examining whether and how soldiers’ moral communities such as the military unit, the military organization and society play a role in these dynamics. Thorough examination of these issues can help to better understand risk and protective factors for moral injury, and offer more comprehensive insight into both the development of moral injury and the path toward recovery. Third, regarding treatment specifically, it would be fruitful to further investigate the value of themes and techniques such as Socratic questioning, (self-)forgiveness and purification and reintegration rituals, as well as of interventions such as stress and ethics training in the military, initiatives of rapprochement between the military and society, and efforts of political compensation and reparation.

Conclusion

This article discussed the results and implications of a systematic review of literature relevant to contextual factors in moral injury, identifying and synthesizing insights from psychology, philosophy, theology and social sciences. As became clear, the causes of moral injury lie not only at the individual level but also in contextual factors. Accordingly, answers to the question of moral injury should be sought not only at the individual level – involving only the morally injured individuals in question – but also at other levels. This review calls for interdisciplinary, context-sensitive research on moral injury in the military (and other relevant contexts). Such research will lead to an understanding of not only the psychological but also the spiritual/existential, organizational, political and societal dimensions of moral injury. This in turn, can contribute to the development of (more) adequate interventions for moral injury, including holistic therapy, rituals, trainings, compensation and reconciliation practices, and other context-sensitive interventions.

Military personnel, perhaps more than any professional group, are dependent on their organization and politics for their safety and well-being, and it can be argued that the political and military leadership as well as society at large bear particular responsibility for soldiers’ health, since it is in the name of society that soldiers are placed in high-risk circumstance. Moreover, this review showed that feelings of being let down by the military and political leadership and alienation from society may play an important role in veterans’ experience. For all these reasons, the to-date insufficiently addressed contextual dimensions of moral injury merit attention.

Funding Statement

This work is supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) [project number NWA.1160.18.019], the Netherlands Defense Academy, the Netherlands Veterans Institute, the Netherlands Police Academy and ARQ National Psychotrauma Centre.

Note

Notably, the few psychological studies on moral injury that do explicitly discuss morality also define it as a complex system that develops in social contexts (Litz et al., 2009). However, they generally do not follow through on this insight, and still approach thoughts and emotions related to moral injury as the result of violations of an internally harmonious, intra-psychic code (see e.g., the reviews of Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016; Griffin et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2018).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). [Google Scholar]

- Antal, C. J., Yeomans, P. D., East, R., Hickey, D. W., Kalkstein, S., Brown, K. M., & Kaminstein, D. S. (2019). Transforming veteran identity through community engagement: A chaplain-psychologist collaboration to address moral injury. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1–26. 10.1177/0022167819844071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zeev, D., Corrigan, P. W., Britt, T. W., & Langford, L. (2012). Stigma of mental illness and service use in the military. Journal of Mental Health, 21(3), 264–273. 10.3109/09638237.2011.621468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bica, C. C. (1999). A therapeutic application of philosophy. The moral casualties of war: Understanding the experience. International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 13(1), 81–92. 10.5840/ijap19991313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, T. E. (2011). The morally injured. Massachusetts Review, 51(1), 646–564. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23210143 [Google Scholar]

- Bowker, M. H., & Levine, D. P. (2016). Beyond the battlefield: “Moral injury” and moral defence in the psychic life of the soldier, the military, and the nation. Organisational and Social Dynamics, 16(1), 85–109. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/phoenix/osd/2016/00000016/00000001/art00006 [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, P. (2018). Moral dilemmas associated with following military orders. In Moral decisions and military mental health: Final report of task group HFM-179 (pp. 3-1–3-8). NATO Office of Information and Press. NATO Science & Technology Organization (STO/NATO). [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., Bryan, A. O., Anestis, M. D., Anestis, J. C., Green, B. A., Etienne, N., Morrow, C. E., & Ray-Sannerud, B. (2016). Measuring moral injury: Psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment, 23(5), 557–570. 10.1177/1073191115590855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, T. O. D., Broesder, W., & Meijer, M. (2012). Strain and stress: Role ambiguity in an unfriendly environment. In Beeres R., van der Meulen J., Soeters J. L., & Vogelaar A. L. W. (Eds.), Mission Uruzgan: Collaborating in multiple coalitions for Afghanistan (pp. 107–118). Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, L. B., & Hodgson, T. J. (2018). Chaplaincy, spiritual care and moral injury: Considerations regarding screening and treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, Article 619, 1–10. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coeckelbergh, M. (2013). Drones, information technology, and distance: Mapping the moral epistemology of remote fighting. Ethics and Information Technology, 15(2), 87–98. 10.1007/s10676-013-9313-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., Drescher, K., & Foy, D. (2015). Initial psychometric evaluation of the moral injury questionnaire - Military version. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(1), 54–63. 10.1002/cpp.1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Guerre, D. W., Emery, M., Aughton, P., & Trull, A. S. (2008). Structure underlies other organizational determinants of mental health: Recent results confirm early sociotechnical systems research. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 21(5), 359–379. 10.1007/s11213-008-9101-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denborough, D. (2021). Moral injury and moral repair: The possibilities of narrative practice. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work, (4), 24–58. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.185150167829051 [Google Scholar]

- DePrince, A. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2002). The harm of trauma: Pathological fear, shattered assumptions, or betrayal. In Kauffman J. (Ed.), Loss of the assumptive world: A theory of traumatic loss (pp. 71–82). Brunner-Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods, M., Bonas, S., Booth, A., Jones, D. R., Miller, T., Sutton, A. J., Shaw, R. L., Smith, J. A., & Young, B. (2006). How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 27–44. 10.1177/1468794106058867 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, K. D., Foy, D. W., Kelly, C., Leshner, A., Schutz, K., & Litz, B. (2011). An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology, 17(1), 8–13. 10.1177/1534765610395615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelson, R., Pilisuk, M., & Soldz, S. (2011). The dark side of Comprehensive Soldier Fitness. American Psychologist, 66(7), 643–644. 10.1037/a0025272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enemark, C. (2019). Drones, risk, and moral injury. Critical Military Studies, 5(2), 150–167. 10.1080/23337486.2017.1384979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth, J. K. (2014). Dialogical tensions in heroic military and military-related moral injury. International Journal for Dialogical Science, 8(1), 13–37. https://ijds.lemoyne.edu/journal/8_1/pdf/IJDS.8.1.02.Farnsworth.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth, J. K., Drescher, K. D., Evans, W., & Walser, R. D. (2017). A functional approach to understanding and treating military-related moral injury. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(4), 391–397. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrajão, P. C., & Aragão Oliveira, R. (2016). Portuguese war veterans: Moral injury and factors related to recovery from PTSD. Qualitative Health Research, 26(2), 204–214. 10.1177/1049732315573012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, L. D. (2015). Evidence-based trauma treatment: Problems with a cognitive reappraisal of guilt. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 35(4), 220–229. 10.1037/teo0000021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, W. H. (2021). Moral injury and the absurd: The suffering of moral paradox. Journal of Religion & Health, 60(5), 3012–3033. 10.1007/s10943-021-01227-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt, S., & Frazier, P. (2016). A review of research on moral injury in combat veterans. Military Psychology, 28(5), 318–330. 10.1037/mil0000132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, C. (2014). Moral injury and the ethic of care: Reframing the conversation about differences. Journal of Social Philosophy, 45(1), 89–106. 10.1111/josp.12050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gnaulati, E. (2019). Potential ethical pitfalls and dilemmas in the promotion and use of American Psychological Association-recommended treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychotherapy, 56(3), 374–382. 10.1037/pst0000235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. J., & Nash, W. P. (2017). Adaptive disclosure: A new treatment for military trauma, loss, and moral injury. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. J., Nash, W. P., & Litz, B. T. (2017). When self-blame is rational and appropriate: The limited utility of Socratic questioning in the context of moral injury: Commentary on Wachen et al. (2016). Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 24(4), 383–387. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, B. J., Purcell, N., Burkman, K., Litz, B. T., Bryan, C. J., Schmitz, M., Villierme, C., Walsh, J., & Maguen, S. (2019). Moral injury: An integrative review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 350–362. 10.1002/jts.22362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, J. H., Cragun, R. T., & Hwang, K. (2013). Measuring spiritual fitness: Atheist military personnel, veterans, and civilians. Military Psychology, 25(5), 438–451. 10.1037/mil0000010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hautzinger, S., & Scandlyn, J. (2013). Beyond post-traumatic stress: Homefront struggles with the wars on terror. Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, T. J., & Carey, L. B. (2017). Moral injury and definitional clarity: Betrayal, spirituality and the role of chaplains. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(4), 1212–1228. 10.1007/s10943-017-0407-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. (1997). Recognition and moral obligation. Social Research, 64(1), 16–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40971157 [Google Scholar]

- Hosein, S. (2019). Muslims in the US military: Moral injury and eroding rights. Pastoral Psychology, 68(1), 77–92. 10.1007/s11089-018-0839-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jinkerson, J. D. (2016). Defining and assessing moral injury: A syndrome perspective. Traumatology, 22(2), 122–130. 10.1037/trm0000069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joh, E. E. (2016). Policing police robots. UCLA Law Review Discourse, 516(64), 518–543. https://www.uclalawreview.org/policing-police-robots/ [Google Scholar]

- Kilner, P. (2010, February 10). A moral justification for killing in war. Army, 55–60. https://juniorofficer.army.mil/pubs/armymagazine/docs/2010/CC_ARMY_10-02%20(FEB10)%20Morality-of-Killing.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kinghorn, W. (2012). Combat trauma and moral fragmentation: A theological account of moral injury. Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, 32(2), 57–74. 10.1353/sce.2012.0041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H. G., Ames, D., Youssef, N. A., Oliver, J. P., Volk, F., Teng, E. J., Haynes, K., Erickson, Z. D., Arnold, I., O’Garo, K., & Pearce, M. (2018). The moral injury symptom scale - Military version. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(1), 249–265. 10.1007/s10943-017-0531-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H. G., Youssef, N. A., & Pearce, M. (2019). Assessment of moral injury in veterans and active duty military personnel with PTSD: A review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(443), 1–15. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, S. E., Fleming, C. J. E., & Resick, P. A. (2019). Residual symptoms following empirically supported treatment for PTSD. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(2), 207–215. 10.1037/tra0000384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt, K., Reynolds, S. J., Barnes, C. M., Schilpzand, P., & Hannah, S. T. (2012). Different hats, different obligations: Plural occupational identities and situated moral judgments. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1316–1333. (world). 10.5465/amj.2010.1023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lifton, R. J. (1973). Home from the war: Learning from Vietnam veterans. Other Press. [Google Scholar]

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londoño, A., Romero, P., & Casas, G. (2012). The association between armed conflict, violence and mental health: A cross sectional study comparing two populations in Cundinamarca department, Colombia. Conflict and Health, 6(12), 1–6. 10.1186/1752-1505-6-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeish, K. T. (2018). On “moral injury”: Psychic fringes and war violence. History of the Human Sciences, 31(2), 128–146. 10.1177/0952695117750342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeish, K. (2021). Moral Injury and the Psyche of Counterinsurgency. Theory, Culture & Society, 02632764211039279. 10.1177/02632764211039279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. L., Houtsma, C., Bryan, A. O., Bryan, C. J., Green, B. A., & Anestis, M. D. (2017). The impact of aggression on the relationship between betrayal and belongingness among U.S. military personnel. Military Psychology, 29(4), 271–282. 10.1037/mil0000160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, M. (2011, April 28). Combat stress as “moral injury” offends Marines. Stars and Stripes. Retrieved May 28, 2015, from https://www.stripes.com/blog/stripes-central/stripes-central-1.8040/combat-stress-as-moral-injury-offends-marines-1.142177

- McCormack, L., & Ell, L. (2017). Complex psychosocial distress postdeployment in veterans: Reintegration identity disruption and challenged moral integrity. Traumatology, 23(3), 240–249. 10.1037/trm0000107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meador, K. G., & Nieuwsma, J. A. (2018). Moral injury: Contextualized care. Journal of Medical Humanities, 39(1), 93–99. 10.1007/s10912-017-9480-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meagher, R. E. (2014). Killing from the inside out: Moral injury and Just War. Cascade Books. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), 264–269. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk, T. (2018a). Moral injury in relation to public debates: The role of societal misrecognition in moral conflict-colored trauma among soldiers. Social Science & Medicine, 211, 314–320. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk, T. (2018b). Toward an interdisciplinary conceptualization of moral injury: From unequivocal guilt and anger to moral conflict and disorientation. New Ideas in Psychology, 51, 1–8. 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk, T. (2019). The role of political practices in moral injury: A study of Afghanistan veterans. Political Psychology, 40(2), 261–275. 10.1111/pops.12503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk, T. (2021). Moral injury and soldiers in conflict: Political practices and public perceptions. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk, T., Kramer, E.-H., & Verweij, D. E. M. (2018). Moral aspects of ‘moral injury’: Analyzing conceptualizations on the role of morality in military trauma. Journal of Military Ethics, 17(1), 36–53. 10.1080/15027570.2018.1483173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nash, W. P., & Litz, B. T. (2013). Moral injury: A mechanism for war-related psychological trauma in military family members. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(4), 365–375. 10.1007/s10567-013-0146-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies (Vol. 11). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ogle, A. D., Reichwald, R., & Rutland, J. B. (2018). Psychological impact of remote combat/graphic media exposure among US Air Force intelligence personnel. Military Psychology, 30(6), 476–486. 10.1080/08995605.2018.1502999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, N. J. (2019). Moral injury as loss and grief with attention to ritual resources for care. Pastoral Psychology, 68(1), 107–125. 10.1007/s11089-018-0854-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld, N. (2009). De gewetensvolle veteraan [The Conscientious Veteran] [Doctoral dissertation]. Tilburg University. [Google Scholar]

- Scandlyn, J., & Hautzinger, S. (2014). Collective reckoning with the post 9/11 wars on a Colorado homefront. In Costs of war (pp. 1–17). Brown University: Watson Institute for International Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, J. (1994). Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, J. (2014). Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 31(2), 182–191. 10.1037/a0036090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, N. (2015). Afterwar: Healing the moral wounds of our soldiers. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). Institutional betrayal. American Psychologist, 69(6), 575–587. 10.1037/a0037564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshein, S. (2007). The role of construction, intuition, and justification in responding to ethical issues at work: The sensemaking-intuition model. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1022–1040. 10.5465/amr.2007.26585677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, W. P., & Starnino, V. R. (2019). “Staring into the abyss”: Veterans’ accounts of moral injuries and spiritual challenges. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 22(1), 25–40. 10.1080/13674676.2019.1578952 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiinikka-Lydon, J. (2017). Moral injury as inherent political critique: The prophetic possibilities of a new term. Political Theology, 18(3), 219–232. 10.1080/1462317X.2015.1104205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Stevelink, S. A., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Occupational moral injury and mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(6), 339–346. 10.1192/bjp.2018.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco, B. E., Marx, B. P., May, C. L., Martini, B., Krystal, J. H., Southwick, S. M., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2017). Moral injury in US combat veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Depression and Anxiety, 34(4), 340–347. 10.1002/da.22614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthen, M., & Ahern, J. (2014). The causes, course, and consequences of anger problems in veterans returning to civilian life. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 19(4), 355–363. 10.1080/15325024.2013.788945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yandell, M. (2019). Moral injury and human relationship: A conversation. Pastoral Psychology, 68(1), 3–14. 10.1007/s11089-018-0800-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeterian, J. D., Berke, D. S., Carney, J. R., McIntyre-Smith, A., St Cyr, K., King, L., Kline, N. K., Phelps, A., & Litz, B. T., & Members of the Moral Injury Outcomes Project Consortium . (2019). Defining and measuring moral injury: Rationale, design, and preliminary findings from the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 363–372. 10.1002/jts.22380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.