Abstract

Purpose

To determine if recruitment manoeuvres (RMs) would decrease 28-day mortality of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) compared with standard care.

Materials and methods

Relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published prior to April 26, 2018 were systematically searched. The primary outcome was mortality. The secondary outcomes were oxygenation, barotrauma or pneumothorax, the need for rescue therapies. Data were pooled using the random effects model. And the quality of evidence was assessed by the GRADE system.

Results

Of 3180 identified studies, 15 were eligibly included in our analysis (N = 2755 participants). In the primary outcome, RMs were not associated with reducing 28-day mortality (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.74–1.09), ICU mortality (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.74–1.1), and the in-hospital mortaliy (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.93–1.12). In the secondary outcomes, RMs could improve oxygenation (MD 37.85; 95% CI 11.08–64.61), the rates of barotrauma (RR 1.42; 95% CI 0.83–2.42) and the need for rescue therapies (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.42–1.12) did not show any difference in the ARDS patients with RMs.

Conclusions

Earlier meta-analyses found decreased mortality with RMs, in the contrary, our results indicate that RMs could improve oxygenation without detrimental effects, but it does not appear to reduce mortality.

Keywords: Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Recruitment maneuver, Mechanical ventilation, Randomized controlled trial

Abbreviations: RMs, recruitment manoeuvres; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; ICU, intensive care unit (ICU); PEEP, positive end expiratory pressure; ALI, acute lung injury; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; RR, risk ratios; CI, confidence intervals; AECC, American-European consensus conference; BiPAP, Bi-Level Positive Airway Pressure; LUS, lung ultrasonography; EIT, electrical impedance tomography

1. Introduction

ARDS represents a life-threatening form of respiratory failure that affects >3 million patients with ARDS each year, accounting for 10% of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, and resulting in a high mortality ranging from 35% to 46% [1]. ARDS is an acute, diffuse, inflammatory lung injury [2]. Bellani G et al. reported that 24% of patients with ARDS had received mechanical ventilation in the ICU, which suggests that mechanical ventilation are feasible in the ARDS's therapy [1], by minimising further pulmonary insult while providing acceptable oxygenation and carbon dioxide clearance [3]. Nowadays, various forms of mechanical ventilation are used, however, among those major mechanical ventilation strategies, only the low tidal volume strategy and positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) are associated with reduced mortality [4]. In addition, mechanical ventilation may bring about ventilator-induced lung injury due to alveolar overdistension, repetitive alveolar opening and collapse (atelectrauma), biotrauma, and oxygen toxicity, which may result in a lung inflammatory response and develop the multiple system organ failure [5,6]. Therefore, it is very imperative to find the optimal mechanical ventilation strategy for ARDS.

During the past decades, RMs have been increasingly concerned, which have been widely used in ARDS, acute lung injury (ALI), and patients under general anesthesia [7,8]. RMs refer to any technique that transiently raise the transpulmonary pressure above regular tidal ventilation to re-open previously collapsed lung tissue [9]. Here, a variety of RMs have been described, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), stepwise RMs, and extended sigh manoeuvres, etc. [10].

Given that RMs are helpful in openning collapsed lung tissue and decreasing strain and tidal recruitment [11], RMs have received much attention in the treatment for ARDS and become a feasible ventilatory strategy, which are used as an isolated intervention or as a part of some ventilatory strategies. Furthermore, some previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses showed that RMs might decrease mortality of patients with ARDS without increasing the risk of main adverse events [12,13]. However, RMs may increase intrathoracic pressure, cause barotrauma, reduce venous return and impair cardiac function [14,15], which may have detrimental effects on mortality. As a result, the application of RMs remains controversial.

Thus, we systematically reviewed the current trials and performed a meta-analysis to assess whether RMs can better improve clinical outcomes of patients with ARDS than standard care.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

We systematically searched for relevant studies published prior to April 26, 2018 in the Pubmed, Embase, Web of science, Cochrane Library. The search terms were as follows: (“recruitment maneuver” or “lung recruitment maneuver”or“Pulmonary reexpansion” or “lung recruitment”or“recruitment manoeuvres”) and (“Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Adult”or“Shock Lung”or“Lung, Shock” or “ARDS, Human” or “ARDSs, Human” or “Human ARDS” or “Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Acute”or“Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome” or “Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome”or“adult respiratory distress” or “ARDS” or “posttraumatic lung failure” or “posttraumatic pulmonary insufficiency” or “shock lung” or “respiratory distress, adult”). We applied no language restrictions and screened manually the reference lists from included studies to identify other relevant articles. Two reviewers (Hanyujie Kang, Huqin Yang) independently searched and evaluated the quality of the studies. Any disagreement was resolved by a third person.

2.2. Study selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients who were diagnosed with ARDS as defined by disease definition consensus at the time of study publication (the best is the patients with moderate or severe hypoxemia (PaO2/FaO2 ≤ 200 mmHg)); 2) adults (at least 18 years old of age) who were mechanically ventilated; 3) studies that compared RMs with standard care; 4) studies that reported the primary outcome of mortality (28-day mortality, ICU mortality and in-hospital mortality) or the secondary outcomes (oxygenation, barotrauma or pneumothorax, the need for rescue therapies) which could be directly extracted or calculated; 5) randomized controlled trial studies.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, letters, or expert opinions; 2) not related to ARDS or RMs; 3) not reported the primary outcome of mortality or the secondary outcomes; 4) studies that enrolled patients younger than 18 years old or animals; 5) not RCTs; 6) cross-over trials; 7) duplicates; 8) insufficient data; 9) experimental group did not receive RMs; 10) control group received RMs; 11) control group did not receive standard care ventilaion; 12) multiple publication.

We defined RMs as any technique that transiently increased the alveolar pressure above regular tidal ventilation to re-expand previously collapsed lung tissue in ARDS. And we defined standard care as a low tidal volume strategy.

2.3. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (Hanyujie Kang, Huqin Yang) independently extracted data from included trials and assessed the risk of bias. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion. We extracted the following data from the eligible studies: first author, publication year, total number of participants, criteria for enrollment, characteristics of the patients, intervention description, hospital environment, outcomes, study methods. If any of these data were inadequate, we contacted the corresponding authors by e-mail. The risk of bias of the included studies was assesed by the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias tool [16] and rated as “low,” “unclear,” or “high” in several domains. We did not assess the sections related to blinding of participants and personnel, or blinding of outcome assessment for the following reasons: Firstly, it may be impossible to blind healthcare personnel to group allocation; secondly, we assumed that participants were unaware of group allocation because of critical ill, and consent for participation was got from the next of kin; Thirdly, blinding of outcome assessment would not influence the bias because the primary outcome was mortality.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was mortality (28-day mortality, ICU mortality and in-hospital mortality).

Secondary outcomes were oxygenation (partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2 ratio), barotrauma or pneumothorax, the need for rescue therapies (prone position, nitric oxide, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, or extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation).

2.5. Statistical analysis

We presented the risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes. Values for continuous outcomes were given as the mean (standard deviation). Meta-analysis was performed using the Mantel-Haenszel random effects model. Statistical heterogeneity across trials or subgroups were tested by I2 testing, with values >50% regarded as being indicative of moderate-to-high heterogeneity [17]. Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analyses were used to explore sources of heterogeneity. Four prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted for the main outcomes: (1)trials with higher risk of bias versus trials with lower risk of bias; (2)different types of RMs; (3)RMs achieving a peak pressure of ≤40 cmH2O versus a peak pressure of >40 cmH2O; (4)RMs alone versus RMs co-intervention with higher PEEP or other therapies. In the meta-analyses of main outcomes, we also did sensitivity analyses by sequentially omitting one study each time or excluded studies with co-intervention (e.g. higher PEEP) in the experimental group to identify the potential influence. We evaluated the possibility of publication bias by constructing a funnel plot when more than seven studies were included in the meta-analysis. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry using Egger tests [18], and defined significant publication bias as a p value <.05. The quality of evidence for important outcomes was evaluated by the principles of GRADE system. Statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager Version 5.2 (Cochrane IMS, Oxford, UK), Stata version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA), and GRADE Pro version 3.6 (GRADE Working Group).

3. Results

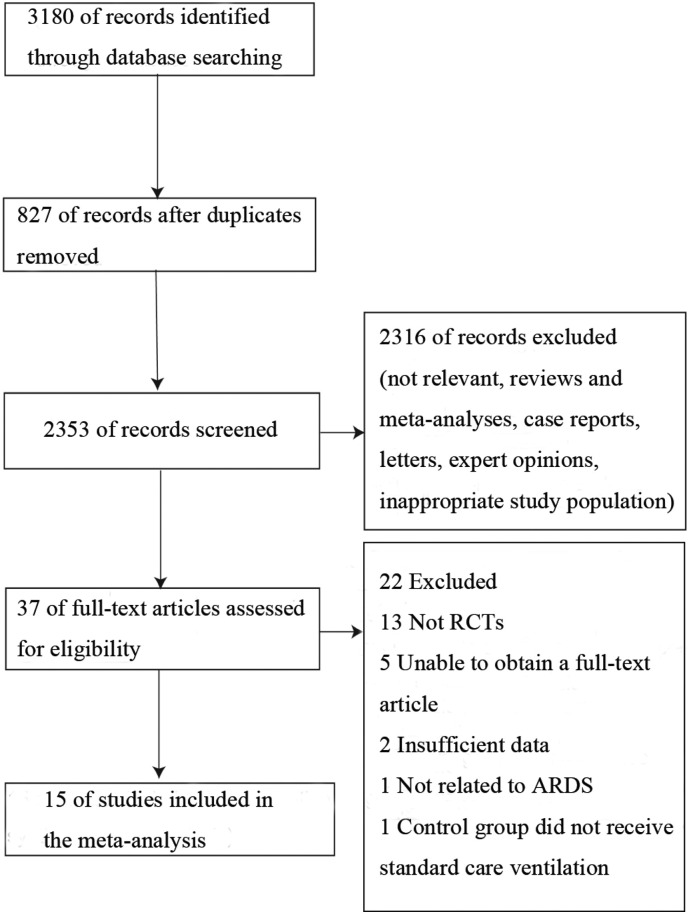

We identified 3180 studies, from which 827 were duplicates (Supplemental Fig. 1). After screening titles and abstracts, 2316 trials were excluded because of not meeting the inclusion criteria. Then, we obtained full-text articles for 37 citations, of which 22 were excluded for reasons described in the Supplemental Fig. 1. Ultimately, 15 articles involving a total of 2755 participants were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]], all studies cited did in fact get informed consent from each study participant and that each study was approved by an ethics committee or institutional review board.

Supplemental Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study selection.

3.1. Study characteristics

The included studies were published between 2003 and 2017. The sample size varied from 17 in. a single-centre randomized controlled trial (RCT) [33] to 1010 in a multi-centre RCT [19]. Study characteristics are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Source | Centers | Criteria for enrollment | Eligibility | Methods | Group | Number of patients | Type of RMs |

Frequency of RMs |

PEEP titration strategy |

Target tidal volume |

Mean PEEP after RM |

Mode |

Plateau pressure |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavalcanti/2017 | 120 ICUs |

AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS ≤ 72 h,P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 501 | PCV | NS | Decremental PEEP titration: The PEEP associated with the best compliance plus 2 cmH2O was considered the optimal PEEP |

5.8 ml/kg | NS | ACPC | 25.8 cmH2O | |

| Control | 509 | NA | NA | ARDSnet: low PEEP, low tidal volume | 5.8 ml/kg | NS | ACVC | 26.2 cmH2O | ||||||

| Chung/ 2017 |

1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS ≤ 48 h,P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 12 | PEEP increment method: (Under pressure-controlled mode, driving pressure was set to 15 cm H2O above PEEP. The level of PEEP was increased to a maximum of 40 cm H2O in increments of 5 cmH2O from 10 cm H2O, and the level was fixed to 40 s in each increment.) |

Only once on day 1 when the patients enrolled |

PEEP titration phase: the PEEP was adjusted to 25 cm H2O, and it was reduced by increments of 5 cmH2O each time | 6–8 ml/kg | 13.8 cmH2O | ACPC | 25.5 cmH2O | |

| Control | 12 | NA | NA | PEEP titration to keep SaO2 ≥ 90% |

6–8 ml/kg | 13.5 cmH2O | ACPC | 24.5 cmH2O | ||||||

| Yu/2017 | 1 | Berlin definition |

Patients with ARDS (duration not specified),P/F ≤ 300 |

Prospective study | RMs | 36 | PEEP increment method: Lung recruitment was performed in condition of SIMV mode (pressure control and pressure support). PEEP was increased by 5 cmH2O every time and maintained for 40–50 s before entering the next increasing circle, and the peak airway pressure was always kept below 45 cmH2O |

Every 8 h | After PEEP reached the peak value, it was then reduced by 5 cmH2O every time, and maintained at 15 cmH2O for 10 min. | 6–7 ml/kg | 15 cmH2O | SIMV | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 38 | NA | NA | The minimum PEEP level to maintain the target oxygenation with the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) less than 60% |

6–7 ml/kg | 8.2 cmH2O | SIMV | ≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Kacmarek/2016 | 20 ICUs |

AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS ≤ 48 h,P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 99 | PCV 15 cmH2O, PEEP 35–45 cmH2O to achieve Ppeak of 50–60 cmH2O |

At randomization | Decremental PEEP trial: PEEP at which compliance is maximized during decremental trial +3cmH2O | 6 ml/kg | 15.8 cmH2O | ACPC | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 101 | NA | NA | ARDSnet PEEP/FiO2 |

6 ml/kg | 11.6 cmH2O | ACVC | ≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Zhou/2014 | 1 | Berlin definition |

Patients with ARDS(duration not specified),P/F ≤ 100 | Prospective study | RMs | 56 | “Prone position ventilation combined with PEEP incremental method” |

Not clear | Decremental PEEP trial | ≤6 ml/kg | 12 cmH2O | ACPC | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 60 | NA | NA | Lung Protective ventilation: PEEP 20cmH20 Fi02为100% | ≤6 ml/kg | 13 cmH2O | ACPC | ≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Yang/2011 | 1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS(duration not specified),P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 19 | Sustained inflation (CPAP 40 cmH2O for 30s) |

Every 8 h for a total of 5 days |

Similar to control group(PEEP titration to keep PaO2 > 60, FiO2 < 0.6) | 350–450 ml | NS | ACPC | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 19 | NA | NA | PEEP titration to keep PaO2 > 60, FiO2 < 0.6 |

350–450 ml | NS | ACPC | ≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Zhang/2011 | 1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS(duration not specified),P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 15 | Increasing the PEEP in a stepwise fashion, first to 10 cmH20 (3 breaths), then to 15 cmH20 (3 breaths),and finally to 20 cmH20 (10 breaths) |

Once every 12 h and lasted 3 days |

Similar to control group | 6–8 ml/kg | NS | ACPC | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 15 | NA | NA | PEEP was adjusted according to inspired oxygen concentration, which was to maintain PEEP at a minimum level |

6–8 ml/kg | NS | ACPC | ≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Hodgson/2011 | 1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS < 72 h,P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 10 | Staircase recruitment to Ppeak 55 cmH2O: the high pressure was set to 15 cmH2O above the PEEP, which was increased in a stepwise manner to 20, then 30 and then 40 cmH2O every two minutes | Daily,oxygen desaturation or diconnection |

Decremental reduction in PEEP titration from 25 to 15 every 30s until a decrease in SaO2 ≥ 1%. PEEP was then increased to 40cmH2O for 1 min. Optimal PEEP was 2.5cmH2O above the derecruitment point | ≤6 ml/kg | 17.4 cmH2O | PCV | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 10 | NA | NA | ARDSnet PEEP/FiO2 |

6 ml/kg | NS | ACVC | ≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Xi/2010 | 14 ICUs |

AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS (duration not specified),P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 55 | Sustained inflation (CPAP 40 cmH2O for 40s) |

Every 8 h for the first 5 days |

Similar to control group | 6–8 ml/kg | 10.5 cmH2O | CPAP | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 55 | NA | NA | PEEP to obtain SaO2 of 90%–95% or PaO2 of 60–80 mmHg, with FiO2 ≤ 0.60 | 6–8 ml/kg | 9.7 cmH2O | ACVC or ACPC for first 24 h |

≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Wang/2009 | 1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS (duration not specified),P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 10 | BIPAP | Every 8 h per day until on the 7th day or before weaning of mechanical ventilation |

Similar to control group | 6–8 ml/kg | NS | BIPAP | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 10 | NA | NA | Lung Protective ventilation(PEEP was adjusted according to inspired oxygen concentration, which was to maintain PEEP at a minimum level) | 6–8 ml/kg | NS | SIMV+ ACPC |

≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Huh/2009 | 1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS (duration not specified),P/F ≤ 200 | Prospective study | RMs | 30 | Extended sigh,Vt 25% of baseline,PEEP up to 25 cmH2O,Ppeak maximum 55 cmH2O |

Maneuver was repeated once a day or when ventilator was disconnected or if FiO2 requirement was increasing,for 1 week |

Decremental PEEP titration: in the decremental phase of the second ARM,PEEP was set 2cmH2O above the PEEP that leads to 2% drop in SpO2 or drop of static compliance |

6 ml/kg | 10 cmH2O | ACVC | NS | |

| Control | 27 | NA | NA | ARDSnet PEEP/FiO2 |

6 ml/kg | 9.5 cmH2O | ACPC | NS | ||||||

| Meade/2008 | 30 ICUs |

Onset of new respiratory symptoms within 28 days and bilateral opacifications on chest radiograph,and requiring PaO2/FIO2 ≤ 250 during invasive mechanical ventilation | Patients with ARDS ≤ 48 h,P/F ≤ 250 |

Prospective study | RMs | 475 | Sustained inflation (CPAP 40 cmH2O for 40s after ventilator disconnection) |

Up to 4 times daily, until FiO2 ≤ 0.40 | High PEEP: Standardized PEEP/FiO2 table to PaO2 55-80 mmHg or SaO2 88–93%, with higher PEEP levels than the control group |

6 ml/kg | 14.6 cmH2O | ACPC | ≤40 cmH2O | |

| Control | 508 | NA | NA | ARDSnet low PEEP-FiO2 table |

6 ml/kg | 10.1 cmH2O | ACVC | ≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Wang/2007 | 1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS (duration not specified),P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | 14 | Sustained inflation (CPAP 35 cmH2O for 35 s) |

NS | According to ARDSnet table | 6 ml/kg | 9.8 cmH2O | NS | ≤30 cmH2O | ||

| Control | 14 | NA | NA | According to ARDSnet table | 6 ml/kg | 11.6 cmH2O | NS | ≤25–30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Yi/2005 | 1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS (duration not specified),P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 14 | Sustained inflation (CPAP 40 cmH2O for 40s) |

Every 8 h for a total of 5 days |

Similar to control group | 6 ml/kg | 9.6 cmH2O | CPAP | ≤30 cmH2O | |

| Control | 14 | NA | NA | PEEP titrated to keep PaO2 > 60,FiO2 < 0.6 |

6 ml/kg | 8.5 cmH2O | ACVC | ≤30 cmH2O | ||||||

| Park/2003 | 1 | AECC definition |

Patients with ARDS ≤ 48 h,P/F ≤ 200 |

Prospective study | RMs | 11 | NO combined with sustained inflation (CPAP 30–35 cmH2O for 30s) |

Twice daily | Similar to control group | 6 ml/kg | 10.4 cmH2O | CPAP | NS | |

| Control | 6 | NA | NA | PEEP was set before ARM performing stepwise increase from 8 to 15 cmH2O(in increments of 2cmH2O)and set based on best oxygenation.PEEP was kept after ARM |

6 ml/kg | 8.2cmH2O | ACVC | NS |

RMs, recruitment maneuves; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; AECC, American-European consensus conference; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; NS, not stated; VT, tidal volume; P/F, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/fraction inspired oxygen; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood; FiO2, fraction inspired oxygen; Ppeak, peak inspiratory pressure; ACVC, assist control volume control mode; ACPC assist control pressure control mode; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; ARDSNet, The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network; BiPAP, Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure; PCV, pressure-controlled ventilation; SIMV, synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation; NO, nitric oxide; NA, not applicable.

All included studies except two enrolled patients with moderate or severe hypoxemia (PaO2/FaO2 ≤ 200 mmHg). Most defined ARDS according to American-European consensus conference (AECC) criteria [34]. Only two of included trials [21,23] used the definition of ARDS provided by the Berlin definition [35].

RMs varied across studies. Five studies used a PEEP incremental method [20,21,23,25,26], six studies used the CPAP method [24,27,[30], [31], [32], [33]], one studies used a extended sigh method [29], two studies performed RMs by pressure control ventilation [19,22], and one trial performed RMs by BiPAP (Bi-Level Positive Airway Pressure) [28]. Eight studies included a ventilation strategy that combined a higher PEEP ventilation with RMs [[19], [20], [21], [22],26,[29], [30], [31]]. Zhou et al. also used the same ventilation strategy, but participants in the experimental group were managed in the prone position [23]. Five studies applied RMs as an isolated intervention [24,25,27,28,32]. One study included nitric oxide therapy as a co-intervention with RMs [33].

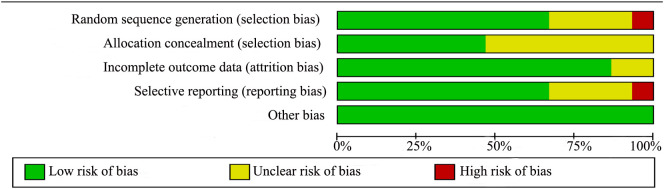

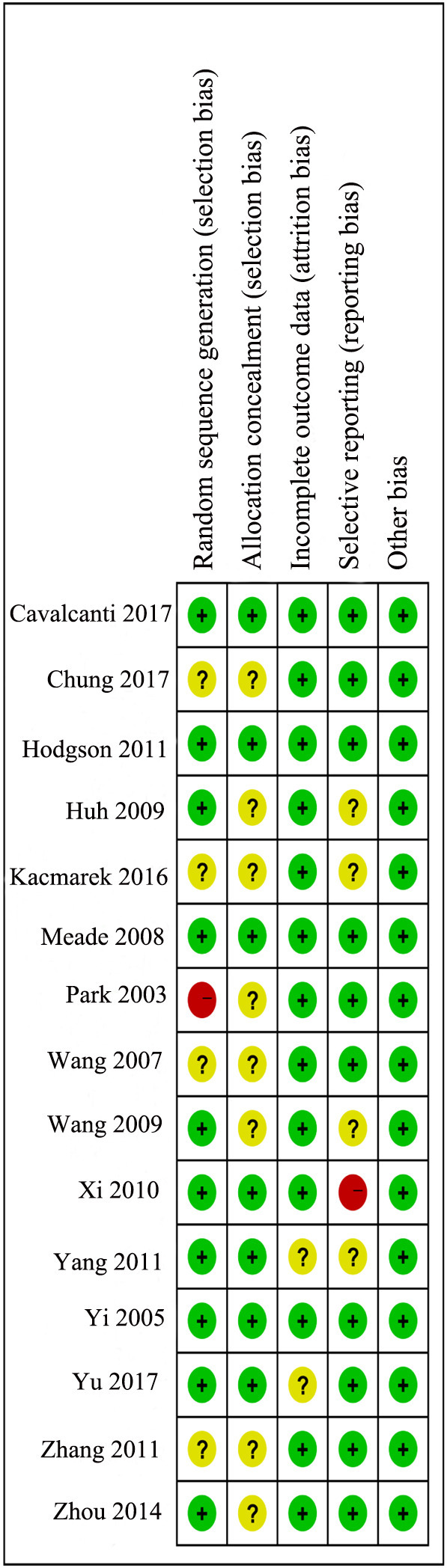

3.2. Risk of bias

The assessment of risk of bias are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2 and Supplemental Fig. 3. Four trials [19,26,30,32] had a lower risk of bias because they showed a low risk of bias in nearly all of the items. Most studies were rated as having a moderate risk of bias. Only one studies has high risk of bias in selective reporting biases because of not analysing these patients as intention-to-treat [27].

Supplemental Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph.

Supplemental Fig. 3.

Risk of bias summary.

3.3. Primary outcomes

3.3.1. 28-Day mortality

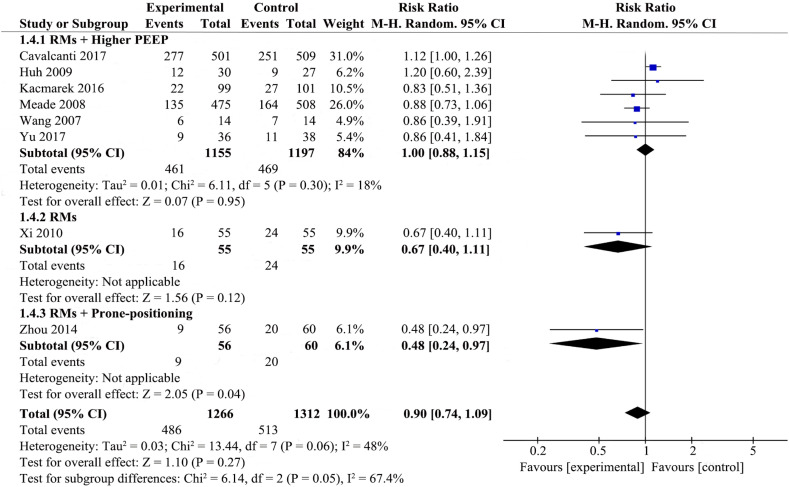

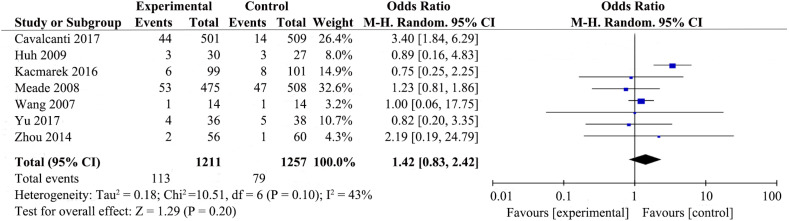

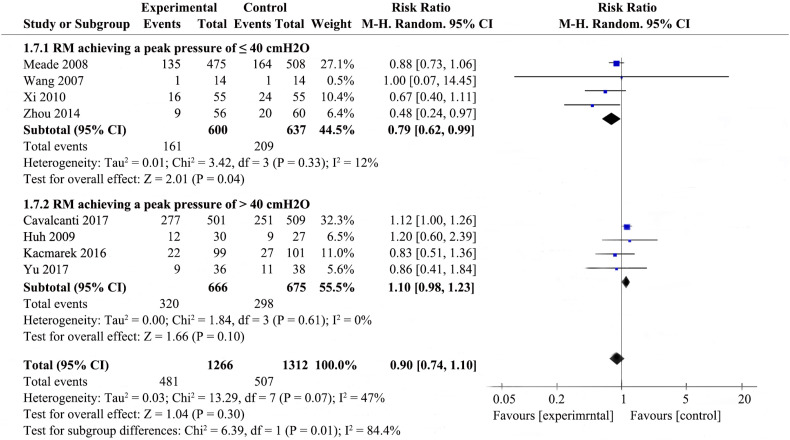

Eight studies [19,[21], [22], [23],[27], [28], [29], [30], [31]] that included 1266 patients from the experimental group and 1312 patients from the control group examined 28-day mortality. The details are presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Forest plot for 28-day mortality associated with recruitment manoeuvres in ARDS.

RMs were not associated with reducing 28-day mortality in the random-effects model (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.74–1.09; P = .27), with mild heterogeneity among the studies (χ2 = 13.44, I2 = 48%), we therefore investigated the source of the heterogeneity.

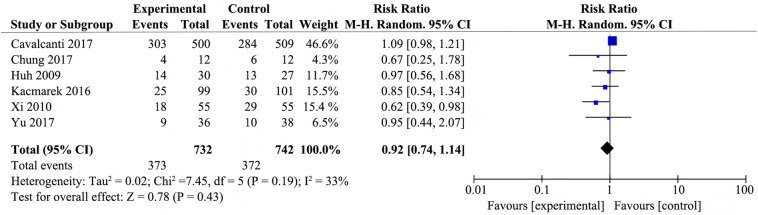

3.3.2. ICU mortality

Six studies [19,[20], [21], [22],27,29] that included 732 patients from the experimental group and 742 patients from the control group assessed the effect of RMs on the ICU mortality of patients with ARDS (Supplemental Fig. 4). There were no differences in ICU mortality between RMs group and control group (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.74–1.14; P = .43), with low heterogeneity among the studies (χ2 = 7.45, I2 = 33%).

Supplemental Fig. 4.

Forest plot for intensive care unit mortality associated with recruitment manoeuvres in ARDS.

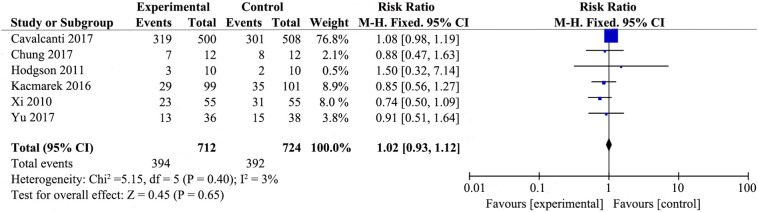

3.3.3. In-hospital mortality

Six studies [19,[20], [21], [22],26,27] that included 712 patients from the experimental group and 724 patients from the control group examined in-hospital mortality (Supplemental Fig. 5). The experimental group that included RMs did not appear to reduce in-hospital mortaliy (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.93–1.12; P = .65). There was no heterogeneity among the studies (χ2 = 5.15, I2 = 3%).

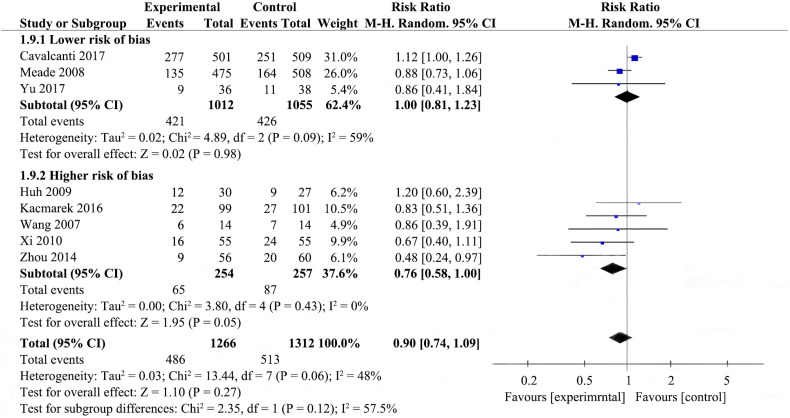

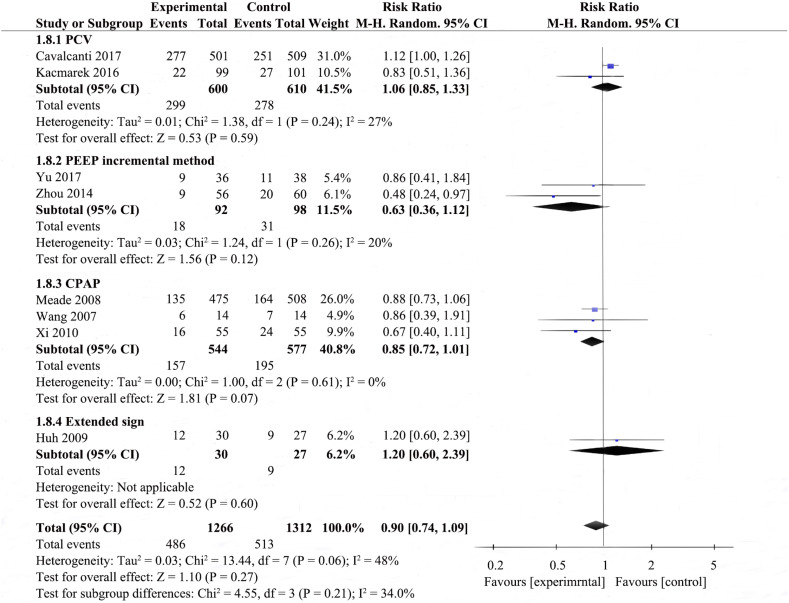

3.3.4. Subgroup analysis of mortality

Potential heterogeneity in 28-day mortality was explored with subgroup analysis (Fig. 1, Supplemental Fig. 6, Supplemental Fig. 7, Supplemental Fig. 8). Four studies were enrolled to analyze 28-day mortality among the RMs achieving a peak pressure of ≤40cmH2O subgroup [23,27,30,31], pool analysis showed that the RMs group reduced 28-day mortality in comparison to control group (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.62–0.99; I2 = 12%); there were four studies in the RMs achieving peak pressure of >40 cmH2O subgroup [19,21,22,29], RMs did not appear to reduce 28-day mortality (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.98–1.23; I2 = 0%); the P value for subgroup differences was 0.01. The effect of RMs on 28-day mortality was similar in the subgroup of studies in which RMs combined with higher PEEP [12,17,18,[25], [26], [27]] (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.88–1.15; I2 = 18%) compared to the subgroup with RMs alone [27] (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.40–1.11), ventilatory strategies that included RMs and prone-positioning [23]showed a pronouced effect on 28-day mortality (RR 0.48; 95% CI 0.24–0.97); the P for subgroup differences was 0.05. Pooled analysis of the studies with higher risk of bias [23,27,29,31] showed a larger effect on mortality (RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.58–1.00; I2 = 0%) than the pooled analysis of studies with lower risk of bias [19,21,30] (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.81–1.23; I2 = 59%); the P for subgroup differences was 0.12. Effects on 28-day mortality were not different for trials used different types of RMs, there were no differences in 28-day mortality between all experimental group and control group. Two studies [19,22] performed RMs by pressure control ventilation (RR 1.06; 95% CI 0.85–1.33; I2 = 27%), two studies [21,23] performed RMs by PEEP incremental method (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.36–1.12; I2 = 20%), three studies [27,30,31] performed RMs by CPAP (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.72–1.01; I2 = 0%), one study [29] performed RMs by extended sigh (RR 1.20; 95% CI 0.60–2.39); the P for subgroup differences was 0.21. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 6 and Fig. 1, subgroup analysis by the level of Ppeak or employing co-interventions could explain the heterogeneity (p < .1).

3.3.5. Sensitivity analyses of mortality

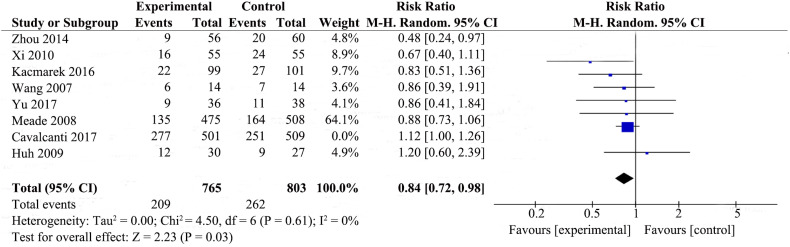

We also did sensitivity analyses by sequentially omitting one study each time to identify the potential influence on 28-day mortality. We found that the result changed after omitting the latest study [19](Supplemental Fig. 9). RMs reduced 28-day mortality (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.72–0.98; P = .03), and there was no heterogeneity among the studies (χ2 = 4.50, I2 = 0%).

3.4. Secondary outcomes

3.4.1. Barotrauma or pneumothorax

Seven trials [19,[21], [22], [23],[29], [30], [31]] reported rates of barotrauma or pneumothorax (Fig. 2 ). RMs did not increase risk of barotrauma or pneumothorax (RR 1.42; 95%CI 0.83–2.42; P = .20), with low heterogeneity among the studies (χ2 = 10.51, I2 = 43%).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing the recruitment manoeuvres' effect on barotrauma or pneumothorax of ARDS patients.

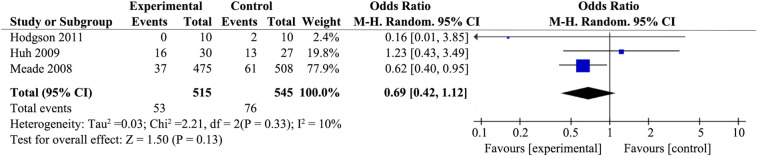

3.4.2. Rescue therapies

Only three trials [26,29,30] assessed use of rescue therapies for patients with ARDS (Fig. 3 ). Ventilatory strategies that included RMs had no pronouced effect on the use of rescue therapies for participants with ARDS (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.42–1.12; P = .13), with no heterogeneity among the studies (χ2 = 2.21, I2 = 10%).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing the effect of recruitment manoeuvres on rescue therapies of patients with ARDS.

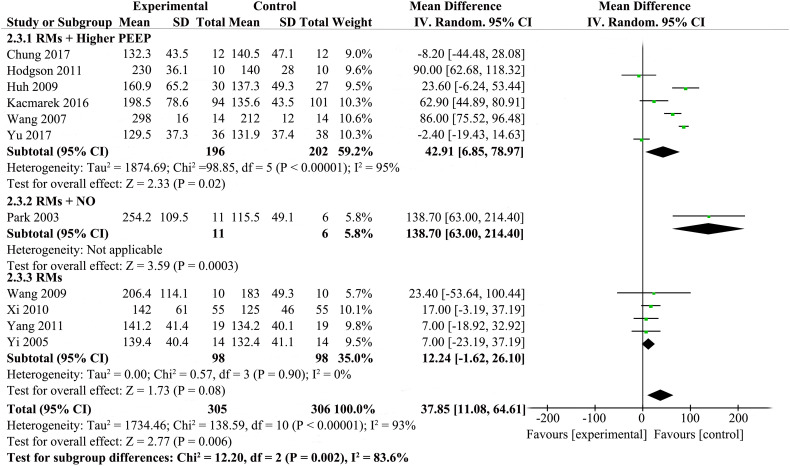

3.4.3. Oxygenation

Oxygenation (PaO2/FiO2 ratio at 24 to 48 h after randomiztion) was reported by eleven studies [[20], [21], [22],24,[26], [27], [28], [29],[31], [32], [33]], while details are presented in Fig. 4 . The results showed that RMs improved PaO2/FiO2 ratio at 24 to 48 h after randomiztion compared with standard care (MD 37.85; 95% CI 11.08–64.61; P = .006). The statistical heterogeneity was high (χ2 = 138.59, I2 = 93%), so we investigated the source of the heterogeneity.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing the effect of recruitment manoeuvres on oxygenation of patients with ARDS.

3.4.4. Sensitivity analyses of oxygenation

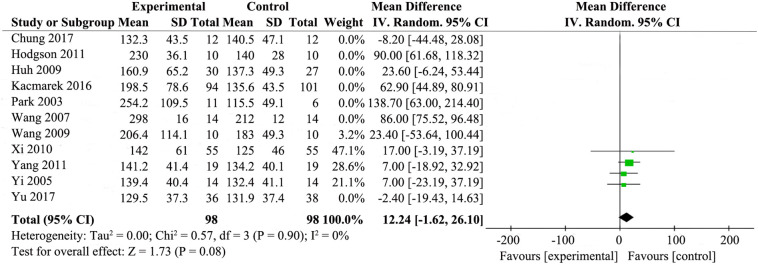

Potential heterogeneity in oxygenation was explored with sensitivity analyses. We did sensitivity analyses by excluding trials with co-interventions (e.g. higher PEEP or NO) which had potential influence on outcomes. Then, the result changed after omitting these trials [[20], [21], [22],26,29,31,33] The results showed that RMs for the patients with ARDS did not have obvious effect on improving the oxygenation (MD 12.24; 95% CI, −1.62 to26.10; P = .08). There was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.57, I2 = 0%) (Supplemental Fig. 10).

3.4.5. Publication bias

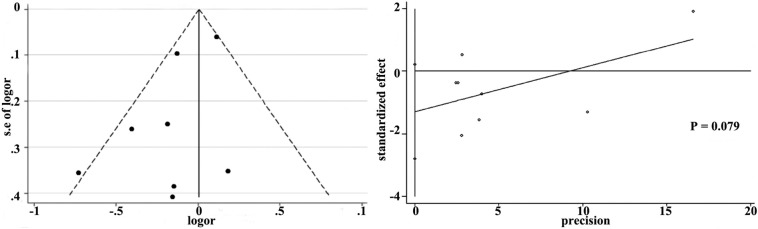

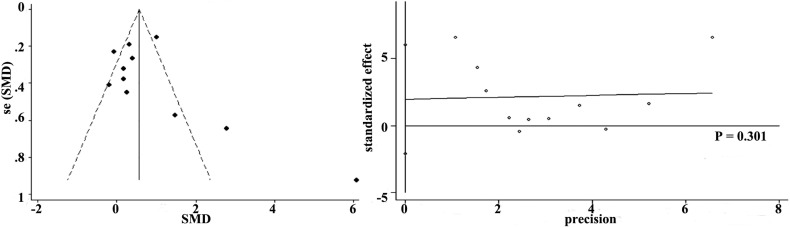

More than seven studies reported 28-day mortality and oxygenation, so we used funnel plot analysis to assess publication bias. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 11 and Supplemental Fig. 12, there were no obvious evidence of publication bias for 28-day mortality and oxygenation by funnel plots and Egger's test (P values for 28-day mortality and oxygenation were 0.079 and 0.301, respectively).

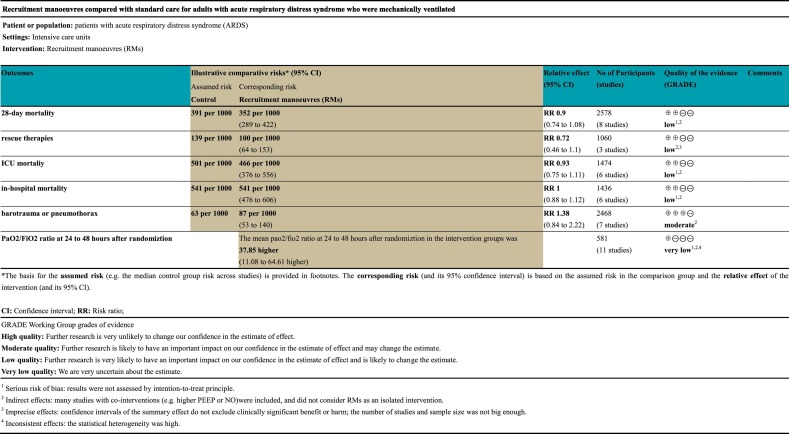

3.4.6. Quality of the meta-analysis evidence

The principles of GRADE system indicated that the quality of evidence for primary outcomes were of low quality (Table 2 )

Table 2.

GRADE summary of Fingdings comparing RMs to standard care for patients with ARDS.

4. Discussion

ARDS represents a serious problem which is associated with a high mortality ranging from 35% to 46% [1]. RMs are a feasible strategy that can be simply used at bedside on patients with ARDS, which are characterized by transiently raising the transpulmonary pressure to re-open collapsed lung tissue [9]. However, the re-opening process could lead to overdistention and hemodynamic impairment [[36], [37], [38]]. Therefore, the application of RMs on ARDS patients is still controversial.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that RMs did not reduce the mortality (28-day mortality, ICU mortality, and the in-hospital mortaliy) of patients with moderate or severe ARDS. Nevertheless, RMs could improve oxygenation, while not raising the risk of barotrauma or pneumothorax and increasing the use of rescue therapies. Overall, the results demonstrated that it is safe to use RMs on ARDS patients.

Potential heterogeneity could be detected in 28-day mortality and oxygenation. Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analyses were used to explore the sources of heterogeneity. The results showed that subgroup analyses couldn't explain the heterogeneity. The possible reason may be the small number of trials and the high risk of bias in some trials. Hence, we cannot confidently conclude that the effect of RMs on 28-day mortality was similar in these subgroups. However, in our subgroup analysis of RMs achieving a peak pressure of ≤40cmH2O versus RMs achieving peak pressure of >40 cmH2O, the effect was different between the subgroups. In the RMs achieving peak pressure of >40 cmH2O subgroup, RMs did not appear to reduce 28-day mortality. It is possible that higher PEEP can prevent alveolar collapse at end expiration, but it may also cause ventilator-induced lung injury through alveolar overdistention [39]. As for the significant heterogeneity in oxygenation in this study, we performed sensitivity analyses by excluding trials with co-interventions (e.g. higher PEEP or NO). Then, the result changed and the statistical heterogeneity could not be detected, which suggested that the co-interventions had potential impact on the outcomes. Applying adequate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) after RMs could prevent alveolar derecruitment [40], this may account for the result. Accordingly, RMs and PEEP titration are interdependent strategies for the success of treatment. But the number of these trials that did not employ co-interventions was small and the sample size was not big enough. Thus, we cannot confidently conclude that RMs employed in isolation did not have obvious effect on improving the oxygenation in patients with ARDS. Nevetheless, in clinical practice, RMs and PEEP are usually combined to open collapsed lung alveolar and keep them opened. So, applying RMs without PEEP makes little sense.

Our findings were different from the latest systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2017 [12], which reported that RMs were associated with the reduced 28-day mortality of patients with ARDS. We supposed that the main reason for the difference is that we have included a latest large-scale trial with high quality done by Cavalcanti, A.B. et al. [19]. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by omitting that study and the result changed, which suggests that the trial done by Cavalcanti, A.B. et al. has a potential influence on the result of 28-day mortality. In the latest large-scale trial done by Cavalcanti, A.B. et al., we found that RMs were associated with the increased 28-day mortality. We supposed that the following reasons could account for it. Firstly, in the control group, the lung protective characteristics of a low tidal volume strategy may reduce the atelectrauma. To some extent, the potential physiological advantages of the lung recruitment and PEEP titration strategy have been partly cancelled out. Secondly, the increasing in overdistention and hemodynamic impairment may have offset the potential strengths of the lung recruitment strategy [[36], [37], [38]].

Several limitations should be considered. Firstly, although we have searched all the related literatures, some unpublished trials might be missed. Secondly, the sample size of eight included studies was not big enough, in which the enrolled patients were <50. Thirdly, due to the risk of the included studies and the indirectness of evidence, the quality of evidence for primary outcome was low. We classified the evidence as indirect because many studies with co-interventions (e.g. higher PEEP or NO) were included, and did not consider RMs as an isolated intervention. This may be caused by the routine that RMs and PEEP titration are the most common strategies in clinical practice. Fourthly, some studies did not provide information on the main outcomes. Finally, as not all studies had available individual patient data, we were unable to assess the effects of RMs in some important subgroups, such as patients with early ARDS (<4–5 days) or later ARDS (>4–5 days) and patients with pulmonary ARDS or extrapulmonary ARDS.

Although our study did not support the opinion that the RMs were of great benefit to mortality, RMs are desirable if it can be used appropriately. Thus, it is very promising in the future to have individualized treatments to reduce lung injury and get the best curative effect. First of all, since patients with different lung recruitability had different response to RMs, assessing patients' lung recruitability before RMs application could guide individualized ventilation strategies to prevent ventilator-associated lung injuries and keep the lungs open [41]. Accordingly, it is necessary to strengthen the surveillance of the response to RMs and/or lung recruitability during the lung recruitment period, especially for patients with hemodynamic instability and high risk factors for barotrauma. Now, more and more physiological variables and techniques with relatively high sensitivity and specificity have emerged to estimate lung recruitability, such as static lung compliance, esophageal pressure monitoring, computed tomography, the use of lung ultrasonography (LUS), electrical impedance tomography (EIT) [41]. Secondly, it is also essential to explore the optimal RMs strategies for different patients with regards to type, duration, frequency, peak pressure and titration of PEEP. Types of RMs should be chosen on the basis of hemodynamics, oxygenation, barotrauma episodes, and lung recruitability through physiological variables and imaging techniques [41]. During recruitment maneuver, we could dynamically adjust our ventilation procedure based on information from the monitoring of the pulmonary function and respiratory mechanics to minimize possible deleterious effects [42]. The optimal PEEP should be determined by the PEEP/FIO2 tables of the ARDS Network or best compliance on the basis of a balance between alveolar recruitment and overdistention. Beyond that, many other advanced methods, such as stress index, esophageal manometry, ultrasound, and electrical impedance tomography, can be also used for PEEP selection if permitted [43]. Last but not least, it is important to guide the treatment according to the severity of the disease. Many studies have revealed that patients with moderate or severe hypoxemia, early ARDS and/or extrapulmonary ARDS are associated with greater lung recruitability [36,[44], [45], [46], [47]]. So, further research should focus on individual participants'features to find whether effects of RMs vary with severity, different stages, and cause of ARDS, which may help to give better individualized treatment.

5. Conclusion

In summary, compared with standard care, RMs did not appear to reduce mortality (28-day mortality, ICU mortality, and the in-hospital mortaliy), but could improve oxygenation for patients with ARDS, without detrimental effects on barotraumas and rescue therapies. Since there are some limitations in this meta-analysis, further prospective studies should be performed to confirm the effects of RMs on patients with ARDS.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Supplemental Fig. 5.

Forest plot for hospital mortality associated with recruitment manoeuvres in ARDS.

Supplemental Fig. 6.

Forest plot for subgroup analysis of 28-day mortality according to peak pressure.

Supplemental Fig. 7.

Forest plot for subgroup analysis of 28-day mortality according to risk of bias.

Supplemental Fig. 8.

Forest plot for subgroup analysis of 28-day mortality according to different types of recruitment manoeuvres.

Supplemental Fig. 9.

Forest plot for sensitivity analyses of 28-day mortality by omitting the latest study.

Supplemental Fig. 10.

Forest plot for sensitivity analyses of oxygenation by excluding trials with co-interventions.

Supplemental Fig. 11.

Funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits and Egger’ publication bias plot of 28-day mortality.

Supplemental Fig. 12.

Funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits and Egger’ publication bias plot of oxygenation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used to perform the meta-analysis are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.

Funding

This work was supported by the funds of Capital's Funds for Health Improvement and Research (2016–1-1061), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (ZYLX201312) and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals' Ascent Plan (DFL20150302).

Authors' contributions

Hanyujie Kang and Huqin Yang take responsibility for integrity of the data interpretation and analysis. All authors contributed substantially to the study design, data interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript. Hanyujie Kang performed statistical analysis and data synthesis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Bellani G., Laffey J.G., Pham T., Fan E., Brochard L., Esteban A., et al. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. 2016;315(8):788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan E., Brodie D., Slutsky A.S. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2018;319(7):698–710. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silversides J.A., Ferguson N.D. Clinical review: Acute respiratory distress syndrome - clinical ventilator management and adjunct therapy. Crit Care. 2013;17(2):225. doi: 10.1186/cc11867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epelbaum O., Aronow W.S. Mechanical ventilation in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Hosp Pract (1995) 2017;45(3):88–98. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2017.1331687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villar J., Blanco J., Zhang H., Slutsky A.S. Ventilator-induced lung injury and sepsis: two sides of the same coin? Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77(6):647–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plötz F.B., Slutsky A.S., van Vught A.J., Heijnen C.J. Ventilator-induced lung injury and multiple system organ failure: a critical review of facts and hypotheses. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(10):1865–1872. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kacmarek R.M., Kallet R.H. Should recruitment maneuvers be used in the management of ALI and ARDS? RESP CARE. 2007;52(5):622–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartland B.L., Newell T.J., Damico N. Alveolar recruitment maneuvers under general anesthesia: A systematic review of the literature. RESP CARE. 2015;60(4):609–620. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brower R.G., Morris A., MacIntyre N., Matthay M.A., Hayden D., Thompson T., et al. Effects of recruitment maneuvers in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with high positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(11):2592–2597. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000090001.91640.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Constantin J.M., Godet T., Jabaudon M., Bazin J.E., Futier E. Recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(14):290. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.07.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keenan J.C., Formenti P., Marini J.J. Lung recruitment in acute respiratory distress syndrome: what is the best strategy? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20(1):63–68. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goligher E.C., Hodgson C.L., Adhikari N., Meade M.O., Wunsch H., Uleryk E., et al. Lung Recruitment Maneuvers for Adult Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(Suppl. 4):S304–S311. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201704-340OT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzumura E.A., Figueiro M., Normilio-Silva K., Laranjeira L., Oliveira C., Buehler A.M., et al. Effects of alveolar recruitment maneuvers on clinical outcomes in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(9):1227–1240. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan E., Checkley W., Stewart T.E., Muscedere J., Lesur O., Granton J.T., et al. Complications from recruitment maneuvers in patients with acute lung injury: secondary analysis from the lung open ventilation study. Respir Care. 2012;57(11):1842–1849. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odenstedt H., Aneman A., Kárason S., Stenqvist O., Lundin S. Acute hemodynamic changes during lung recruitment in lavage and endotoxin-induced ALI. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(1):112–120. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2496-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gøtzsche P.C., Jüni P., Moher D., Oxman A.D., et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavalcanti A.B., Suzumura E.A., Laranjeira L.N., Paisani D.M., Damiani L.P., Guimaraes H.P., et al. Effect of Lung Recruitment and Titrated Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) vs Low PEEP on Mortality in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1335–1345. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung F.T., Lee C.S., Lin S.M., Kuo C.H., Wang T.Y., Fang Y.F., et al. Alveolar recruitment maneuver attenuates extravascular lung water in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(30) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu S., Hu T.X., Jin J., Zhang S. Effect of protective lung ventilation strategy combined with lung recruitment maneuver in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) Journal of Acute Disease. 2017;6(4):163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kacmarek R.M., Villar J., Sulemanji D., Montiel R., Ferrando C., Blanco J., et al. Open Lung Approach for the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Pilot. Randomized Controlled Trial CRIT CARE MED. 2016;44(1):32–42. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou X., Liu D., Long Y., Zhang Q., Cui N., He H., et al. The effects of prone position ventilation combined with recruitment maneuvers on outcomes in patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2014;53(6):437–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang G.H., Wang C.Y., Ning R. Effects of high positive end-expiratory pressure combined with recruitment maneuvers in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2011;23(1):28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J.G., Chen X.J., Liu F., Zeng Z.G., Qian K.J. Lung recruitment maneuver effects on respiratory mechanics and extravascular lung water index in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. World J Emerg Med. 2011;2(3):201–205. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cl H., Dv T., Ar D., Mj B., Am H., Ae H., et al. A randomised controlled trial of an open lung strategy with staircase recruitment, titrated PEEP and targeted low airway pressures in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical care (london, england) 2011;(3) doi: 10.1186/cc10249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xi X.M., Jiang L., Zhu B. Clinical efficacy and safety of recruitment maneuver in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome using low tidal volume ventilation: a multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123(21):3100–3105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z.Y., Zhu X., Li H.L., Wang T.H., Yao G.Q. A study on the effect of recruitment maneuver imposed on extravascular lung water in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2009;21(10):604–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jw H., H J., Hs C., Sb H., Cm L., Y K. Efficacy of positive end-expiratory pressure titration after the alveolar recruitment manoeuvre in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical care (london, england). 2009;(1) doi: 10.1186/cc7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meade M.O., Cook D.J., Guyatt G.H., Slutsky A.S., Arabi Y.M., Cooper D.J., et al. Ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes, recruitment maneuvers, and high positive end-expiratory pressure for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(6):637–645. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X.Z., Lu C.J., Gao F.Q., Li X.H., Hao D., Ning F.Y. Comparison of the effects of BiPAP ventilation combined with lung recruitment maneuvers and low tidal volume A/C ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2007;30(1):44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yi L., Xi X.M. Effects of recruitment maneuvers with low tidal volume ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2005;17(8):472–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park K.J., Lee Y.J., Oh Y.J., Lee K.S., Sheen S.S., Hwang S.C. Combined effects of inhaled nitric oxide and a recruitment maneuver in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Yonsei Med J. 2003;44(2):219–226. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2003.44.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernard G.R., Artigas A., Brigham K.L., Carlet J., Falke K., Hudson L., et al. Report of the American-European consensus conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes and clinical trial coordination. The Consensus Committee Intensive Care Med. 1994;20(3):225–232. doi: 10.1007/BF01704707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D., Thompson B.T., Ferguson N.D., Caldwell E., Fan E., et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gattinoni L., Caironi P., Cressoni M., Chiumello D., Ranieri V.M., Quintel M., et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1775–1786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luecke T., Pelosi P. Clinical review: Positive end-expiratory pressure and cardiac output. Crit Care. 2005;9(6):607–621. doi: 10.1186/cc3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Retamal J., Bugedo G., Larsson A., Bruhn A. High PEEP levels are associated with overdistension and tidal recruitment/derecruitment in ARDS patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015;59(9):1161–1169. doi: 10.1111/aas.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahetya S.K., Goligher E.C., Brower R.G. Fifty Years of Research in ARDS. Setting Positive End-Expiratory Pressure in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017;195(11):1429–1438. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2035CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbas C.S., de Matos G.F., Pincelli M.P., Da R.B.E., Antunes T., de Barros J.M., et al. Mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory failure: recruitment and high positive end-expiratory pressure are necessary. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11(1):18–28. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200502000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos R.S., Silva P.L., Pelosi P., Rocco P.R. Recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome: The safe way is the best way. World J Crit Care Med. 2015;4(4):278–286. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v4.i4.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosa R.G., Rutzen W., Madeira L., Ascoli A.M., Dexheimer N.F., Maccari J.G., et al. Use of thoracic electrical impedance tomography as an auxiliary tool for alveolar recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome: case report and brief literature review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2015;27(4):406–411. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20150068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hess D.R. Recruitment Maneuvers and PEEP Titration. Respir Care. 2015;60(11):1688–1704. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grasso S., Mascia L., Del T.M., Malacarne P., Giunta F., Brochard L., et al. Effects of recruiting maneuvers in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with protective ventilatory strategy. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(4):795–802. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rouby J.J., Puybasset L., Nieszkowska A., Lu Q. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: lessons from computed tomography of the whole lung. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4 Suppl):S285–S295. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057905.74813.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grasso S., Stripoli T., De Michele M., Bruno F., Moschetta M., Angelelli G., et al. ARDSnet ventilatory protocol and alveolar hyperinflation: role of positive end-expiratory pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(8):761–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-193OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Constantin J.M., Jaber S., Futier E., Cayot-Constantin S., Verny-Pic M., Jung B., et al. Respiratory effects of different recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2008;12(2):R50. doi: 10.1186/cc6869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used to perform the meta-analysis are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.