Abstract

Objective

Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (OPMD) is a late‐onset inherited neuromuscular disorder, with progressive ptosis and dysphagia as common manifestations. To date, OPMD has rarely been reported among East Asians. The present study summarizes the phenotypic and genotypic features of Chinese patients with OPMD.

Methods

Twenty‐one patients with molecularly confirmed OPMD from 9 unrelated families were identified by direct sequencing of the polyadenlyate binding protein nuclear‐1 (PABPN1) gene. Immunofluorescence staining of muscle biopsies was conducted to identify the components of protein degradation pathways involved in OPMD.

Results

In our cohort, the genetically confirmed OPMD group had a mean age at onset of 50.6 ± 4.2 years (range 45–60 years). Ptosis (42.9%) was the most common initial symptom; patients with ptosis as the first symptom subsequently developed dysphagia within a median time of 5.5 years (range 1–19 years). Evidence of external ophthalmoplegia was found in 38.1% of patients. A total of 33.3% of the patients developed muscle weakness at a median age at onset of 66 years (range 50–70 years), with neck flexor involvement in all patients. Five genotypes were observed in our cohort, including classical (GCG)9–11 repeats in 7 families and non‐GCG elongations with additional GCA expansions in 2 families. OPMD muscle biopsies revealed rimmed vacuoles and intranuclear filamentous inclusions. The PABPN1 protein showed substantial accumulation in the nuclei of muscle fiber aggregates and closely colocalized with p62, LC3B and FK2.

Interpretation

Our findings indicate wide genetic heterogeneity in OPMD in the Chinese population and demonstrate abnormalities in protein degradation pathways in this disease.

Introduction

Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (OPMD, OMIM 164300) is an autosomal dominant adult‐onset inherited neuromuscular disorder that is clinically characterized by slowly progressive eyelid drooping, swallowing dysfunction, and proximal limb weakness. 1 The pathological hallmark of OPMD is the presence of 8.5‐nm intranuclear tubulofilamentous inclusions aggregated in skeletal muscles. 2 Although rimmed vacuoles of autophagic changes are also frequently observed in the skeletal muscles of OPMD patients, they are not a specific feature of this disease and are found in many other muscle disorders.

Genetically, the disease is caused by abnormal expansion of (GCN)n triplet repeats in exon 1 of the polyadenlyate binding protein nuclear‐1 (PABPN1) gene located at chromosome 14q11.2‐14q13. 3 This gene encodes PABPN1, a ubiquitous protein known to bind to virtually all messenger RNAs, activate poly(A)polymerase (PAP) and control poly(A) tail length. 4 , 5 The normal PABPN1 allele contains (GCG)6(GCA)3(GCG)1 with 10 (GCN) repeats, whereas the mutated allele in OPMD contains an abnormal expansion of 11–18 (GCN) repeats that leads to an expanded polyalanine tract (each triplet adds to normal repeats, adding one alanine residue) in the N‐terminal portion of the PABPN1 protein. Polyalanine expansions cause abnormal aggregation of an insoluble PABPN1 protein as intranuclear inclusions in skeletal muscle fibers. 6 The clinical severity of the disease is associated with the length of the (GCN)n expansion. Patients with longer repeat expansions are on average diagnosed earlier and have more severe symptoms. 7 The frequency of the (GCN)11 allele is 1%–2% in some populations, such as North America, some European countries and Japan. 8 For compound heterozygote (GCN)11/(GCN)12–17 expansions, (GCN)11 acts as a disease modifier of dominant OPMD and contributes to a more severe phenotype; in contrast, a homozygous (GCN)11 allele leads to autosomal recessive OPMD with mild manifestations. Overall, homozygosity for a dominant OPMD mutation appears to be associated with the most severe phenotypes. 9 , 10 Additionally, a c.35G > C missense heterozygous mutation in the PABPN1 gene converts a glycine GGG codon to an alanine codon and results in an increase in the number of alanine codons, thus mimicking the effect of a PABPN1 triplet repeat expansion. 11

The frequency of OPMD varies among ethnicities worldwide. The estimated prevalence of the disease is 0.1–1:100,000 in the European population, though it is much more prevalent in certain ethnic communities, such as among Israel's Bukharan Jews (1:600) and French‐Canadians (1:1,000), probably due to a founder effect. 12 , 13 , 14 OPMD has rarely been reported among East Asians, primarily occurring in a small number of families in Japan. 15 , 16 , 17 To date, the largest cohort involved 13 unrelated families with OPMD in the northern region of China, with a few other cases being reported. 18 , 19 , 20 In general, integrated data regarding OPMD epidemiology and clinicopathological characteristics have not yet been comprehensively investigated in China. In this study, we analyzed detailed clinical characteristics and molecular data for 21 OPMD patients from 9 unrelated families in a Chinese cohort. To expand our understanding of the components of protein degradation pathways involved in OPMD, we also investigated PABPN1 distribution and its physical association with p62/sequestosome‐1 (SQSTM1), LC3B, NBR1, and FK2 in OPMD muscle fibers.

Materials and Methods

Patients and clinical assessments

This retrospective study included 21 consecutive patients from 9 unrelated families admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University between 2010 and 2021. The diagnosis of OPMD was based on three major criteria: (a) positive family history, (b) ptosis or previous surgical correction, and (c) dysphagia. 21 A detailed clinical history was obtained for all probands and some of their affected relatives, including age of onset, initial symptoms, disease duration, family pedigree, and neurological examination results. Serum creatine kinase (CK) activity and electromyography (EMG), electrocardiography (ECG), muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and pulmonary function testing results were obtained when available. The study protocols were approved by the local ethics committees, and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Muscle histology, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy

Muscle specimens were obtained from the biceps brachii of F2/III‐1 at age 58, the biceps brachii of F4/II‐1 at age 67, and the deltoid of F6/II‐3 at age 68; the specimens were used for pathological diagnosis and electron microscopy. Samples for histological examination were flash frozen in isopentane precooled with liquid nitrogen. Serial frozen sections (8 μm) were subjected to routine histochemical staining, including hematoxylin and eosin (HE), oil red O, modified Gomori trichrome (MGT), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide tetrazolium reductase (NADH‐TR), periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), cytochrome coxidase (COX), and adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase pH 4.6 and 9.4). To identify PABPN1 inclusions, the muscle sections were treated with 1 M potassium chloride (KCl) to remove soluble proteins. 22 , 23 Immunofluorescence staining was performed using the following primary antibodies: anti‐PABPN1 (Abcam, ab75855, rabbit; 1:250), anti‐SQSTM1/p62 (Abcam, ab109012, mouse; 1:500), anti‐SQSTM1/p62 (Abcam, ab56416, rabbit; 1:500), anti‐LC3B (Cell Signaling Technology, no. 83506, mouse; 1:200), anti‐ubiquitin (Abcam, ab134953, mouse; 1:250), dystrophin (NCLdys1 Novocastra, 1:100), anti‐FK2 (Millipore Corporation, 04–263, mouse; 1:500), and anti‐NBR1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 4BR, mouse; 1:100). The sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, washed in PBS, and mounted with DAPI. Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope. Muscle specimens for electron microscopy examination were successively fixed in 2.5% cooled glutaraldehyde and 2% osmium tetroxide. Thin sections were stained with both uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined by transmission electron microscopy.

Genetic analysis

We collected peripheral blood samples from all available family members. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood leukocytes using QIAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was performed to amplify exon 1 of the PABPN1 gene (NM_004643.4) using specific primers (forward, 5′‐CCTTAGAGGTGGGGCCTTATTTGA‐3′, and reverse, 5′‐CCGGCTCGGGCTCCA‐3′). The amplified products were purified and subjected to Sanger sequencing with an Applied Biosystems ABI 3730XL DNA analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequence data obtained were compared with reference PABPN1 coding sequences.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to evaluate variables (onset age and serum CK level). The onset age and CK level of different groups were examined by the Mann–Whitney U or the Kruskal–Wallis test. The frequency of initial symptoms in different groups was evaluated by Pearson's chi‐square test. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

Results

Distribution of pathogenic genotypes

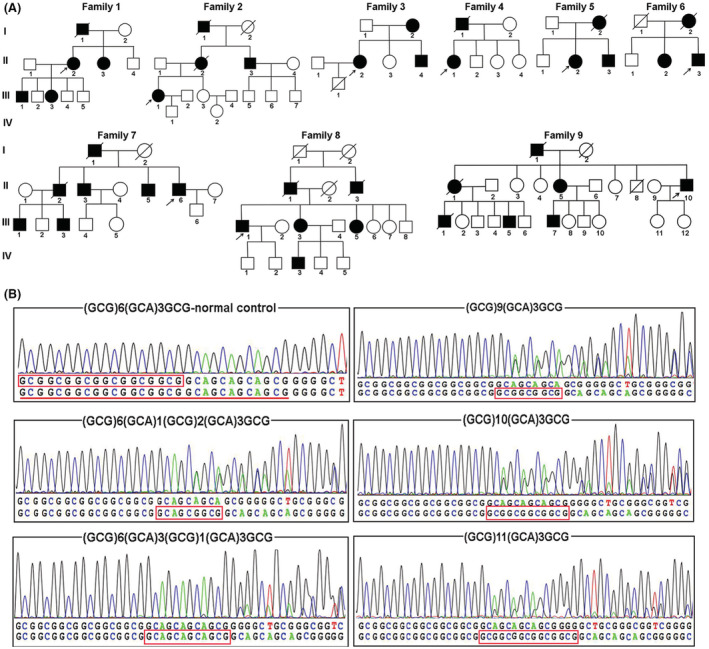

The 21 patients with genetically confirmed OPMD comprised 11 females and 10 males (Table 1). As OPMD is a dominant disease, all of the patients harbored the normal (GCN)10 repeat on one allele coupled with a pathogenic expanded allele containing (GCN)13 to (GCN)15 repeats (Fig. 1). Two forms of expanded genotypes were identified in our patients: pure (GCG) triplet expansions in 7 families and (GCA) triplet interspersions in 2 families (Table 2). The distribution of pure (GCG) triplet expansions was as follows: (GCN)10/(GCN)13 in 2 families, (GCN)10/(GCN)14 in 4 families, and (GCN)10/(GCN)15 in 1 family. In addition, the (GCG)6(GCA)1(GCG)2(GCA)3(GCG)1 allele and (GCG)6(GCA)1(GCG)3(GCA)3(GCG)1 allele were identified in family 6 and family 7, respectively. We also analyzed 100 control individuals, with all carrying two (GCN)10 repeat alleles.

Table 1.

Clinical findings of the 21 OPMD patients.

| Family/patient | Sex/Age (years) | Expansion size | Age at onset (years) | Initial symptoms | Ptosis age of onset | Dysphagia age of onset | Limb muscle weakness age of onset | Distribution of weakness | Ophthalmoparesis | CPK (U/L) | EMG | Cardiac dysfunction | Respiratory involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1/II‐2 | F/70 | 10/13 | 55 | Ptosis, dysphagia | 55 | 55 | 65 | Neck flexor + Proximal limbs | No | 84 | Myogenic damage; RNS(−) | Sinus bradycardia | NA |

| F1/III‐1 | M/53 | 10/13 | 51 | Ptosis, dysphagia | 51 | 51 | No | No weakness | No | 65 | NA | Normal | NA |

| F1/III‐3 | F/52 | 10/13 | 52 | Ptosis, dysphagia | 52 | 52 | No | No weakness | No | 135 | NA | Normal | NA |

| F2/III‐1 | F/59 | 10/13 | 49 | Ptosis | 49 | 56 | No | No weakness | Yes | 96 | Normal; RNS(−) | Normal | Normal |

| F3/I‐2 | F/72 | 10/15 | 52 | Ptosis | 52 | 56 | 61 | Neck flexor + Proximal limbs | Yes | 193 | NA | Normal | NA |

| F3/II‐2 | F/52 | 10/15 | 48 | Ptosis | 48 | 49 | 50 | Neck flexor + Lower limbs | Yes | 120 | Normal; RNS(−) | Normal | Normal |

| F3/II‐4 | M/46 | 10/15 | 45 | Ptosis | 45 | No | No | No weakness | Yes | NA | NA | Normal | NA |

| F4/II‐1 | F/67 | 10/14 | 47 | Ptosis | 47 | 66 | 66 | Neck flexor + Proximal limbs | No | 71 | Myogenic damage; RNS(−) | Left ventricular high voltage | Respiratory insufficieny |

| F5/II‐2 | F/58 | 10/14 | 46 | Dysphagia | 50 | 46 | No | No weakness | No | 509 | Normal; RNS(−) | Normal | Normal |

| F5/II‐3 | M/46 | 10/14 | 45 | Dysphagia | 46 | 45 | No | No weakness | No | 311 | NA | Normal | Normal |

| F6/II‐2 | F/74 | 10/13 | 52 | Ptosis | 52 | 58 | NA | Neck flexor + Proximal limbs | No | 147 | NA | Normal | NA |

| F6/II‐3 | M/71 | 10/13 | 50 | Ptosis | 50 | 60 | 66 | Neck flexor + Lower limbs | No | 1156 | Myogenic damage; RNS(−) | Atrial fibrillation | Respiratory insufficieny |

| F7/II‐5 | M/72 | 10/14 | 48 | Ptosis | 48 | 52 | 70 | Neck flexor + Proximal limbs | No | 291 | Neurogenic changes; RNS(−) | Normal | NA |

| F7/II‐6 | M/67 | 10/14 | 57 | Ptosis | 57 | 62 | No | No weakness | Yes | 92 | Normal; RNS(−) | Normal | Normal |

| F8/II‐1 | M/67 | 10/14 | 60 | Ptosis, dysphagia | 60 | 60 | No | No weakness | No | 149 | Normal; RNS(−) | Normal | Normal |

| F8/II‐3 | F/67 | 10/14 | 58 | Ptosis, dysphagia | 58 | 58 | No | No weakness | Yes | 203 | Normal; RNS(−) | Normal | Normal |

| F8/II‐5 | F/66 | 10/14 | 52 | Ptosis, dysphagia | 52 | 52 | NA | NA | No | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| F8/III‐3 | M/52 | 10/14 | 50 | Ptosis, dysphagia | 50 | 50 | No | No weakness | No | NA | NA | Normal | NA |

| F9/II‐5 | F/68 | 10/14 | 48 | Dysphagia | 55 | 48 | NA | NA | Yes | 165 | Myogenic damage; RNS(−) | Normal | NA |

| F9/II‐10 | M/66 | 10/14 | 50 | Dysphagia | 53 | 50 | No | No weakness | Yes | 526 | Myogenic and neurogenic changes; RNS(−) | Left ventricle (LV) dysfuction | Respiratory insufficieny |

| F9/III‐5 | M/53 | 10/14 | 47 | Dysphagia | 53 | 47 | No | No weakness | No | 227 | NA | Normal | NA |

M, male; F, female; RNS, repetitive nerve stimulation; CPK, serum creatine kinase; NA, not available.

Figure 1.

Wild‐type genotypes in the healthy control group and identification of five genotypes in our OPMD patients. (A) Pedigree charts of nine genetically confirmed OPMD families. (B) Normal 10 (GCN) repeats in the PABPN1 gene; the normal 6 (GCG) repeats are marked with red boxes, and the 10 (GCN) repeats are underlined in red. (C) Abnormal 13–15 (GCN) repeats in the PABPN1 gene; the inserted (GCN) repeats are marked with red boxes.

Table 2.

PABPN1 (GCN) expansions in the analyzed population.

| Genotype | Total alanine codons/(GCN) | Control population | Number of families with OPMD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal sequence (GCG)6(GCA)3(GCG)1 | 10 | 100 normal controls | 0 |

| Pure (GCG) expansion | |||

| (GCG)9(GCA)3(GCG)1 | 13 | 0 | 2 (family 1, 2) |

| (GCG)10(GCA)3(GCG)1 | 14 | 0 | 4 (family 4, 5, 8 and 9) |

| (GCG)11(GCA)3(GCG)1 | 15 | 0 | 1 (family 3) |

| Expansion with (GCA) interspersion | |||

| (GCG)6(GCA)1(GCG)2(GCA)3(GCG)1 | 13 | 0 | 1 (family 6) |

| (GCG)6(GCA)1(GCG)3(GCA)3(GCG)1 | 14 | 0 | 1 (family 7) |

Clinical characteristics of genetically diagnosed OPMD

The mean age at symptom onset was 50.6 ± 4.2 years (range 45–60 years) in the group with genetically confirmed OPMD. There were no significant differences in age of onset between males (mean onset age of 50.3 ± 4.9 years) and females (mean onset age of 50.8 ± 3.6 years) (P > 0.05). Ptosis was the most common initial symptom in 9 patients (42.9%), with a median age at onset of 49 years (range 45–57 years). Dysphagia was the initial symptom in 5 patients (23.8%), with a median age at onset of 47 years (range 45–50 years). Seven (33.3%) patients presented both symptoms, with a median age at onset of 52 years (range 51–60 years). No significant differences in age at onset were observed among these three groups (P > 0.05, Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Comprehensive analysis of the clinical and genetic profiles of patients with OPMD. (A) Distribution of eight genotypes in all reported Chinese patients with OPMD. (B) Statistical comparison of age at onset among the three groups of patients with different initial symptoms. (C) Statistical comparison of age at onset between patients with (GCN)13 and those with (GCN)14–15. *Indicates P < 0.05; ns, not significant.

Seven patients developed muscle weakness at a median onset age of 66 years (range 50–70 years). All of these patients experienced neck flexor and proximal limb weakness with a median disease duration of 13 years (range 2–22 years), though two had no involvement of the upper limbs (median disease duration of 9 years). Patients with ptosis as the first symptom subsequently developed dysphagia within a median time of 5.5 years (range 1–19 years); those with dysphagia as the first symptom subsequently developed ptosis within a median time of 4 years (range 1–7 years). A total of 6 patients (28.6%) developed aspiration pneumonia at a median age of 63 years (range 58–72). Three patients (F5/II‐3, F6/II‐3, and F7/II‐6) underwent ptosis surgery at a median age of 58.0 years (range 49–62 years) and a median of 7.0 years after ptosis onset (range 4–8 years). One patient (F9/II‐10) underwent gastrostomy at the age of 66 years, with a 16.0‐year disease duration after the onset of dysphagia. However, he died from aspiration pneumonia at the age of 70 years.

Phenotype–genotype correlation

All 21 patients had at least (GCN)13 repeats, 6 had (GCN)13 expansion (group 1), and the other 15 had at least (GCN)14 repeats (group 2, 12 with (GCN)14 expansion and 3 with (GCN)15 expansion) (Table 3). The patients in group 2 had a relatively earlier age at onset (median age of 48.0 years) than those in group 1 (median age of 51.5 years), but this difference was not significant (P > 0.05, Fig. 2C). Nine (42.9%) patients had an age of onset before 50 years old; among them, only one patient in group 1 carried the (GCN)13 expansion, and the remaining 8 patients carried (GCN)14 or (GCN)15 repeats. Based on comparisons of the type of clinical onset, there were no significant differences in the proportion of first symptoms between patients in group 1 and group 2 (P > 0.05). However, the presence of dysphagia as the first symptom was only identified in group 2 patients. In family 3, the proband (II‐2) with (GCN)15 expansion exhibited a relatively severe phenotype. She initially presented with droopy eyelids at 48 years old and subsequently experienced difficulty swallowing at the age of 49 years. With disease progression, she developed muscle weakness, with the earliest onset age (50 years) in our group, and had neck flexor and lower limb weakness at 52 years old. She also experienced diplopia and mild bilateral involvement of the superior rectus, inferior rectus, and lateral rectus, as well as extramuscular manifestations, including left ureterostenosis and right ectopic kidney with malrotation (Fig. S1).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of patients with (GCN)13, (GCN)14 and (GCN)15 expansions.

| Clinical features | Group 1: (GCN)13 expansion | Group 2: (GCN)14 and (GCN)15 expansions |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 6 | 15 |

| Male:Female | 2:4 | 8:7 |

| Age at onset (years) | 51.5 ± 2.1 | 50.2 ± 4.8 |

| Type of onset | ||

| Ptosis (n) | 3 | 6 |

| Dysphagia (n) | 0 | 5 |

| Ptosis and dysphagia (n) | 3 | 4 |

| Mean age at examination (years) | 62.3 ± 9.3 | 61.3 ± 9.1 |

| Clinical features | ||

| Ophthalmoparesis (n) | 1 | 7 |

| Proximal limbs weakness | 3 | 4 |

| Mean CK level | 278.5 ± 431.1 | 238.1 ± 149.0 |

| Cardiorespiratory involvement (n) | 1 | 2 |

CK, Serum creatine kinase.

In 6 families for whom age onset across two generations was available, affected offspring showed an earlier age at onset (median age 48 years) than their affected parents (median age 55 years) (P < 0.05). We evaluated whether there was a differential effect of paternal versus maternal transmission on offspring, but no significant differences in onset age were observed based on parental transmission (P > 0.05).

Muscle MR imaging and muscle histology

Muscle MRI and muscle biopsies were performed for 3 patients (F2/III‐1, F4/II‐1 and F6/II‐3). Patient F2/III‐1 only presented minimal fatty streaks predominantly in the adductor magnus and hamstrings. MRI of the skeletal muscles in patients F6/II‐3 and F4/II‐1 revealed involvement of the posterior compartment of the thigh muscles (including the adductor magnus and hamstrings); the adductor magnus was the most severely affected, with fatty replacement among all of the muscles at the thigh level. The gluteus muscles appeared to be affected earlier than the vastus intermedius and vastus lateralis muscles, yet the rectus femoris muscle was preserved even when gluteus muscles with severe fatty infiltration were present (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

T1‐weighted images of the thigh muscles of three patients with different stages of involvement. (A) Patient F2/III‐1, age 59 years, disease duration 10 years; the red arrow indicates fatty streaks in the adductor magnus. (B) Patient F4/II‐1, age 67 years, disease duration 19 years; the red arrow indicates fatty replacement in the adductor magnus and gluteus maximus muscles. (C) Patient F6/II‐3, age 71 years, disease duration 21 years; the red arrow indicates severe fatty infiltration in the adductor magnus and involvement of vastus lateralis muscles.

All biopsies showed increased variation in muscle fiber diameters with some angulated atrophic fibers. Two biopsies presented a predominance of type‐I fibers, but fiber‐type grouping did not occur. Other histopathological changes included internalized nuclei, necrotic and regenerative fibers, and connective tissue proliferation. In addition, rimmed vacuoles were found more frequently in patients F4/II‐1 (biceps brachii muscle) and F6/II‐3 (deltoid muscle) than in patient F‐2/III‐1 (biceps brachii muscle). Ultrastructural analyses using electron microscopy revealed some mitochondria with poorly defined cristae and intranuclear filamentous inclusions in muscle fibers (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Muscle histological findings for patients with OPMD. (A–D) Histochemical images of muscle sections from patient F6/II‐3. H&E staining revealed the variability in the fiber size, with some atrophic fibers (A). ATPase staining (pH 4.6) showed a predominance of type‐I fibers and small angular fibers (B). COX/SDH staining occasionally revealed COX‐deficient fibers (C) and MGT staining showed rimmed vacuoles (D). (E–G) Electron microscopic photograph of muscle sections from F4/II‐1 Electron microscopy studies demonstrated marked autophagic changes (E), and some mitochondrial cristae were poorly defined (red arrows) (F). (G–H) Tubulofilamentous inclusions in the nucleus. Arrows indicate tubulofilamentous inclusions. Scale bars: A–B 100 μm; C–D 50 μm; E,F,H 500 nm; G 2 μm.

CK levels and EMG

The median CK level was 157 IU/L (range, 65–1156). Levels of CK were mildly to moderately (3.8‐fold of the upper limit of normal) increased in four patients, three of whom harbored the (GCN)14 expansion and one the (GCN)13 expansion. There was no significant difference in CK level between patients with (GCN)13 expansion and those with (GCN)14 or (GCN)15 expansion (P > 0.05). Twelve patients underwent electrophysiological examination, and EMG revealed myogenic changes in 4/12 patients, with two carrying the (GCN)13 expansion and two the (GCN)14 expansion. Neurogenic change was observed in one patient (F7/II‐5), who also experienced chronic axonal neuropathy during the course of the disease. A myogenic/neurogenic mixed pattern was found in 1 patient. Normal muscle activity was observed in the remaining 6 patients. RNS tests were normal in all 12 patients.

Cardiopulmonary function

In cardiac assessments, none of the patients displayed malignant arrhythmia on electrocardiography (ECG). ECG findings were normal in 16 patients, whereas cardiac abnormalities were observed in four patients. ECG showed atrial fibrillation in one patient (F6/II‐3) who received radiofrequency ablation (RFA) at the age of 60 years, but cardiac function was normal on the echocardiogram. Right axis deviation was detected in one patient (F9/II‐10), and his cardiac function revealed decreased diastolic function of the left ventricle (LV). Other abnormalities included left ventricular high voltage in one patient and sinus bradycardia in another. Only ten patients underwent pulmonary function analyses, and three had a restrictive respiratory pattern, with a mean onset age of 49 years (range 47–50 years) and a mean disease duration of 18 years (range 16–20 years). Respiratory impairment was moderate (FVC 56%–74%) in patients F4/II‐1, F6/II‐3 and F9/II‐10.

Abnormal accumulation of PABPN1 in the nuclei of muscle fibers and interaction with ubiquitin‐positive autophagic protein

To broaden our understanding of the players of protein degradation pathways involved in OPMD pathogenesis, we selected five of the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) and the autophagy–lysosome pathways (ALP) and analyzed the physical association of these proteins with PABPN1 in OPMD muscle fibers. The autophagy‐associated proteins p62/SQSTM1 and NBR1 are considered to play important roles in the autophagic degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, and impairment of autophagy–lysosome pathways results in abnormal accumulation of p62 and NBR1 in ubiquitin–positive protein inclusions. 24 , 25 Furthermore, an increase in the autophagosomal marker LC3B is associated with abnormally increased formation of vacuolar autophagosomes. 26 , 27 In addition, we selected the ubiquitinated protein marker FK2, together with ubiquitin, to investigate alteration of the ubiquitin–proteasome degradation pathway involved in OPMD.

Immunofluorescence staining revealed PABPN1‐positive nuclei in both MyHC‐I and MyHC‐II subtypes of muscle fibers (Fig. S2). Abnormal accumulation of PABPN1 appeared in the form of strongly immunoreactive, various‐sized, rounded or irregular aggregates, located mainly in nuclear regions and in approximately 5%–7% of the muscle fibers in a given 8‐μm transverse section (Fig. 5). Double‐label immunofluorescence staining revealed the following findings: (a) PABPN1 colocalized with p62/SQSTM1 in the nuclei of several muscle fibers; (b) PABPN1 was immunoreactive within LC3‐immunoreactive aggregates in the nuclear region, but LC3 aggregates seemed to be less abundant than p62/SQSTM; (c) both PABPN1 and FK2 were coimmunoreactive within the regions of nuclear aggregates in some muscle fibers; and (d) NBR1‐immunoreactive aggregates and ubiquitin‐immunoreactive aggregates showed close colocalization with p62 immunoreactivity (Fig. 6). Moreover, ubiquitin was abnormally expressed on the sarcolemma region of several atrophy fibers, and colocalized with the membrane‐associated protein dystrophin (Fig. S3). None of the control muscle biopsies showed PABPN1‐immunoreactive aggregates similar to those observed in OPMD biopsies.

Figure 5.

Abnormal aggregation of PABPN1 protein in the nuclei of muscle fibers in OPMD. Muscle tissues from F2/III‐1 were stained with anti‐PABPN1 antibody (green) and anti‐dystrophin antibody (red). PABPN1 fluorescent immunostaining performed after 1 M potassium chloride (KCl) pretreatment on 8 μm‐thick cryosections. (A–C) Nuclear aggregates containing PABPN1‐immunoreactive small‐rounded and various‐sized inclusions (white arrows). Blue: DAPI staining. Scale bars: A–C 50 μm.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of intranuclear aggregates within OPMD muscle fibers. (A–E) Immunofluorescence staining of muscle biopsies from patients F4/II‐1 and F6/II‐3. (A–C) Double‐label immunofluorescence illustrates nuclear PABPN1‐positive inclusions that partially colocalize with p62 (A), LC3B (B), and FK2 (C). (D) Colocalization of p62 and the autophagic cargo receptor NBR1 in the nuclei of muscle fibers in OPMD, but not in control. (E) The p62 aggregates show close colocalization with ubiquitin, and abnormal accumulation of ubiquitin was found on the sarcolemma region of atrophied fibers. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Discussion

In the present study, we comprehensively analyzed the clinical, molecular, and histopathological features of 21 patients with OPMD in a Chinese cohort. First, our study demonstrated five different genotypes, and classical (GCG)9–11 repeats were found in 7 families, while two different elongated alleles with additional (GCA) interspersion were observed in 2 families. A combined total of eight genotypes were found among the OPMD patients in our cohort and those reported in previous studies in mainland China, indicating wide genetic heterogeneity among OPMD patients in China. Second, we found that PABPN1 accumulated in the form of aggregates colocalizing with p62/SQSTM1, LC3B, ubiquitin, and FK2, revealing abnormalities in protein degradation involving both the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) and autophagic–lysosomal pathways in OPMD. Finally, cardiac abnormalities and respiratory insufficiency were present in our patients, highlighting the importance of cardiac and respiratory screening in OPMD.

This is the first study to confirm five different genotypes in a population of patients with OPMD in southern China. A previous study in northern China reported seven different (GCN) expansion genotypes in 13 unrelated families, including the classical (GCG)8–11 and three different elongated alleles containing additional GCA and GCG expansions. To date, eight different genotypes in patients with OPMD from 24 unrelated families have been reported in mainland China (Supplement Table S1), indicating wide genetic heterogeneity of the disease in Chinese patients. Four of the genotypes with (GCA) interspersions were detected in five families of Chinese patients, which further supports previous findings that unequal crossing‐over is the underlying molecular mechanism causing non‐GCG elongations in OPMD. 28 Unlike the single variant identified in French‐Canadian, Bukhara Jewish, and Uruguayan families, the diverse distribution of repeat lengths in our patients reveals multiple OPMD founders within the Chinese population. 29 , 30 Regarding the frequency of repeat lengths in the Chinese population, an expanded (GCN)13 allele was present in 41.6%, followed by the (GCN)14 allele (37.5%). These results are similar to those observed in some other populations, such as in Spain, the UK, and France, where the (GCN)13 allele is also most common, but with a variation of 40%–73.5%. 31 , 32 Nevertheless, previous studies in the Mexican population have reported that the majority of patients (65%) with OPMD carry the (GCN)15 expansion, with the remaining 35% harboring (GCN)13 repeats. 33 A possible explanation for this discrepancy might be the different genetic backgrounds of various ethnic groups and relatively small sample sizes in some studies, including our cohort. The (GCG)7 expansion, which is considered a recessive allele, has also been reported as a phenotype modifier, and compound heterozygosity with (GCN)11/(GCN)12 leads to a more severe phenotype. This variant was not found among the genotypes of our OPMD patients and 100 normal controls. Our data indicate that (GCG)7 expansion is likely rare in Chinese individuals and among OPMD patients. Further studies with a larger sample size should be conducted to confirm these findings.

In OPMD, polyalanine expansions in PABPN1 protein induces abnormal accumulation of toxic, insoluble protein deposits in the nuclei of muscle fibers. However, although PABPN1 aggregates are the main features of OPMD, the mechanisms by which these aggregates are formed remain poorly understood. Under normal physiological conditions, the correctly functioning ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy–lysosome pathways (ALP) ensure proper control of the quality and quantity of their substrate proteins. 25 , 34 However, when the function of the proteasomal or lysosomal degradation system is impaired or when the proteins accumulated exceed the capacity of the intracellular degradation system, formation of multiprotein aggregates occurs, which is often associated with an increase in the number of autophagosomes, resulting in the formation of autophagic vacuoles. 35 HSP70 and UPS components (e.g., ubiquitin and proteasome subunits) have been reported to be present in PABPN1 nuclear aggregates, which suggests that ubiquitin–proteasome pathway function is impaired in OPMD. 6 , 36 , 37 , 38 Previous transcriptomic analyses and targeted genetic screens have revealed that many UPS components are deregulated in OPMD and correlate with stages of disease progression, confirming the important functional role of UPS deregulation in OPMD pathogenesis. 39 , 40 Our current study for the first time found abnormal accumulation of LC3B and FK2 in PABPN1 nuclear aggregates. p62/SQSTM1 accumulation within PABPN1 aggregates in our patients was also reported in a recent study, 41 and an association with NBR1 crucial for autophagic degradation of ubiquitinated targets has been described. 42 , 43 When autophagy is inhibited, p62 together with NBR1 abnormally accumulates and aggregates and become part of pathological inclusions. In our study, patients intranuclear regions stained positive for p62/SQSTM1, NBR1, ubiquitin and FK2, markers of autophagy‐associated and ubiquitinated proteins; this suggests impairment of the protein degradation system, possibly involving both UPS and ALP. Thus, our demonstration of UPS and ALP abnormalities in OPMD provides further evidence that altered cellular protein degradation pathways may play a critical role in OPMD pathogenesis.

Phenotypically, all of our patients presented with the typical symptoms of progressive ptosis and dysphagia, though proximal limb weakness was a variation of the OPMD phenotype associated with the disease course and the length of (GCN) repeats. Additionally, 38.1% of our patients manifested external ophthalmoplegia, which has been reported as a symptom of OPMD. A previous study in northern China described 13 (38.2%) patients with early onset between 27 years and 40 years of age; conversely, all of our patients developed their first symptoms between 45 years and 60 years of age. Similar to the findings of previous studies in the UK, Canada, and Italy, the most common initial symptom among our OPMD patients was ptosis. Our findings differ partially from the study in the northern region, in which dysphagia was the most common initial symptom. Most of our patients (95.2%) experienced different degrees of severity of dysphagia during the course of the disease; only one patient underwent gastrostomy, which appeared to result in a higher frequency of aspiration pneumonia than previously described. 44

In contrast to other trinucleotide‐related disorders, several studies have sought to correlate the severity of the phenotype with the size of the expansion in OPMD, with controversial results. 45 , 46 Our data support the observations that OPMD patients with longer repeat expansions tend to have earlier symptom onset, yet this evidence is less striking and limited by the small range and size of repeat lengths in our genotyped patients. Another factor influencing age of onset is genetic anticipation, as manifested through an earlier age of onset and/or increased severity of disease in successive generations. Anticipation is commonly reported in trinucleotide repeat disorders, such as myotonic dystrophy and Huntington's disease, though debate remains regarding whether genetic anticipation occurs in OPMD and the specific underlying mechanism. It has been argued that false anticipation may be detected due to ascertainment bias, and recall bias may be an alternative explanation in patients with OPMD; some published data indicate anticipation. 12 , 44 , 47 Our results are in line with those of previous studies, favoring true anticipation in OPMD. The biological basis of anticipation in other trinucleotide‐related disorders has been attributed to the molecular instability of trinucleotide expansions. Regardless, the underlying mechanism generating anticipation in OPMD remains unknown; it may however be due to sampling bias, environmental factors, epigenetic effects and recombination events.

Cardiac involvement commonly occurs in several subtypes of limb girdle muscle dystrophies (such as LGMD2C‐F, 2I, and LGMD1B) and is associated with increased mortality. 48 , 49 Nonetheless, whether cardiac dysfunction occurs in OPMD remains unclear. Cardiac abnormalities were found in 20% of patients, with a mean age of 67.8 ± 1.7 years. The ECG findings among our patients included cardiac arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation, sinus bradycardia) and left ventricular high voltage. LV dysfunction (decreased diastolic function of the left ventricle) was also found in one patient harboring the (GCN)14 repeat. Although we observed a relatively high proportion of cardiac abnormalities in OPMD patients, it was not feasible to determine the percentage of these abnormalities that are directly associated with late‐onset OPMD, as these abnormalities are not uncommon in the older adult population. Indeed, 30% of patients show respiratory involvement, although small samples of pulmonary function data were in our cohort. Our results corroborate the importance of regular monitoring of respiratory function.

In summary, we comprehensively analyzed the spectrum of OPMD genotypes reported in the Chinese population to date, and our findings imply indicate that the genetic basis of OPMD is heterogeneous in Chinese patients. Classical (GCG)8–11 repeats were observed in 19 families (79.2%); non‐GCG elongations with additional GCA expansions were detected in 5 families (20.8%). These findings reveal wide genetic heterogeneity among OPMD patients in the Chinese population. Our data demonstrate that accumulation of proteinaceous aggregates in OPMD muscle fibers is most likely associated with impairment of both the ubiquitin–proteasome and autophagosomal–lysosomal pathways, indicating that improving protein degradation systems in OPMD might be clinically relevant and therapeutically important. Finally, cardiopulmonary dysfunction in OPMD was also observed, which suggests that cardiac and respiratory screening is worthy of clinician's attention in the management of this disease and deserves further investigation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Figure S1. The proband (II‐2, family 3) with a (GCN)15 expansion exhibited extramuscular manifestations. Her cranial MRI revealed several lacunar infarctions in both hemispheres; spiral CT urography (SCTU) showed left ureterostenosis and right ectopic kidney with malrotation.

Figure S2. Coimmunostaining of PABPN1 and myosin heavy chains (MyHCs) on patient F2/III‐1 section. Scale bars: 200 μm.

Figure S3. Double‐label immunofluorescence shows colocalization of ubiquitin and the membrane‐associated protein dystrophin on several atrophy fibers in patient F6/II‐3. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Table S1. Genotypes of PABPN1 reported in OPMD patients of mainland Chinese.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the patients who participated in this study and Lin‐ying Zhou and Yan Hu (Fujian medical University) for their work in preparing the electron microscopy sections.

Funding Information

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81701242, and 81974193, Beijing) and the Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology of Fujian Province (2018Y9079 and 2020Y9016).

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 81974193 and 81701242; Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology of Fujian Province grants 2020Y9016 and 2018Y9079.

References

- 1. Victor M, Hayes R, Adams RD. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 1962;267:1267‐1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tomé F, Fardeau M. Nuclear inclusions in oculopharyngeal dystrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 1980;49:85‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brais B, Bouchard JP, Xie YG, et al. Short GCG expansions in the PABP2 gene cause oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1998;18:164‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wahle E. A novel poly(A)‐binding protein acts as a specificity factor in the second phase of messenger RNA polyadenylation. Cell. 1991;66:759‐768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Apponi LH, Leung SW, Williams KR, Valentini SR, Corbett AH, Pavlath GK. Loss of nuclear poly(A)‐binding protein 1 causes defects in myogenesis and mRNA biogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;19:1058‐1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calado A, Tomé F, Brais B, et al. Nuclear inclusions in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy consist of poly(a) binding protein 2 aggregates which sequester poly(A) RNA. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2321‐2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Richard P, Trollet C, Stojkovic T, et al. Correlation between PABPN1 genotype and disease severity in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2017;88:359‐365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brais B. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy: a late‐onset polyalanine disease. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003;100:252‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blumen SC, Brais B, Korczyn AD, et al. Homozygotes for oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy have a severe form of the disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:115‐118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blumen SC, Bouchard JP, Brais B, et al. Cognitive impairment and reduced life span of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy homozygotes. Neurology. 2009;73:596‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson DO, Wills AJ, Hammans SR, Read SP, Sillibourne J. Oculopharyngeal musculardystrophy: a point mutation which mimics the effect of the PABPN1 gene triplet repeat expansion mutation. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blumen SC, Nisipeanu P, Sadeh M, Asherov A, Tomé FMS, Korczyn AD. Clinical features of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy among Bukhara Jews. Neuromuscul Disord. 1993;3:575‐577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brais B, Rouleau GA, Bouchard JP, Fardeau M, Tomé F. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Semin Neurol. 1999;19:59‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deenen JC, Horlings CG, Verschuuren JJ, et al. The epidemiology of neuromuscular disorders: a comprehensive overview of the literature. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2015;2:73‐85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Uyama E, Nohira O, Chateau D, et al. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy in two unrelated Japanese families. Neurology. 1996;46:773‐778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagashima T, Kato H, Kase M, et al. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy in a Japanese family with a short GCG expansion (GCG)(11) in PABP2 gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10:173‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishii YS, Noto YI, Yasuda R, et al. A Japanese case of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (OPMD) with PABPN1 c.35G > C; p.Gly12Ala point mutation. BMC Neurol. 2021;21:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shan J, Chen B, Lin P, et al. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy: phenotypic and genotypic studies in a Chinese population. Neuromolecular Med. 2014;16:782‐786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. You P, Ma Q, Tao T. Gene diagnosis of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy in a Chinese family by a GeneScan method. J Clin Lab Anal. 2010;24:422‐425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ye J, Zhang H, Zhou Y, Wu H, Wang C, Shi X. A GCG expansion(GCG)11 in polyadenylate‐binding protein nuclear 1 gene caused oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy in a Chinese family. Mol Vis. 2011;17:1350‐1354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Becher MW, Morrison L, Davis LE, et al. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy in Hispanic New Mexicans. Jama. 2001;286:2437‐2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tavanez JP, Calado P, Braga J, Lafarga M, Carmo‐Fonseca M. In vivo aggregation properties of the nuclear poly(A)‐binding protein PABPN1. RNA. 2005;11:752‐762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gidaro T, Negroni E, Perié S, et al. Atrophy, fibrosis, and increased PAX7‐positive cells in pharyngeal muscles of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:234‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bjørkøy G, Lamark T, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1: a missing link between protein aggregates and the autophagy machinery. Autophagy. 2006;2:138‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. D'Agostino C, Nogalska A, Cacciottolo M, et al. Abnormalities of NBR1, a novel autophagy‐associated protein, in muscle fibers of sporadic inclusion‐body myositis. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:627‐636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation ofassays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4:151‐175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nogalska A, D'Agostino C, Terracciano C, Engel WK, Askanas V. Impaired autophagy in sporadic inclusion‐body myositis and in endoplasmic reticulum stress‐provoked cultured humanmuscle fibers. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1377‐1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakamoto M, Nakano S, Kawashima S, et al. Unequal crossing‐over in unique PABP2 mutations in Japanese patients: a possible cause of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:474‐477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blumen SC, Korczyn AD, Lavoie H, et al. Oculopharyngeal MD among Bukhara Jews is due to a founder (GCG)9 mutation in the PABP2 gene. Neurology. 2000;55:1267‐1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rodríguez M, Camejo C, Bertoni B, et al. (GCG)11 founder mutation in the PABPN1 gene of OPMD Uruguayan families. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015;15:185‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tondo M, Gamez J, Gutierrez‐Rivas E, Medel‐Jiménez R, Martorell L. Genotype and phenotype study of 34 Spanish patients diagnosed with oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. J Neurol. 2012;259:1546‐1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hill ME, Creed GA, McMullan TFW, et al. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Phenotypic and genotypic studies in a UK population. Brain. 2001;124:522‐526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cruz‐Aguilar M, Guerrero‐de Ferran C, Tovilla‐Canales JL, Nava‐Castañeda A, Zenteno JC. Characterization of PABPN1 expansion mutations in a large cohort of Mexican patients with oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (OPMD). J Invest Med. 2017;65:705‐708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nogalska A, D'Agostino C, Terracciano C, Engel WK, Askanas V. Impaired autophagy in sporadic inclusion‐body myositis and in endoplasmic reticulum stress‐provoked cultured human muscle fibers. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1377‐1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nixon RA. Autophagy in neurodegenerative disease: friend, foe or turncoat? Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:528‐535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Askanas V, Serdaroglu P, Engel WK, Alvarez RB. Immunolocalization of ubiquitin in muscle biopsies of patients with inclusion body myositis and oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Neurosci Lett. 1991;130:73‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abu‐Baker A, Messaed C, Laganiere J, Gaspar C, Brais B, Rouleau GA. Involvement of the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway and molecular chaperones in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2609‐2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bao YP, Sarkar S, Uyama E, Rubinsztein DC. Congo red, doxycycline, and HSP70 overexpression reduce aggregate formation and cell death in cell models of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. J Med Genet. 2004;41:47‐51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ribot C, Soler C, Chartier A, et al. Activation of the ubiquitin‐proteasome system contributes to oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy through muscle atrophy. PLoS Genet. 2022;18:e1010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Anvar SY, 't Hoen PA, Venema A, et al. Deregulation of the ubiquitin‐proteasome system is the predominant molecular pathology in OPMD animal models and patients. Skelet Muscle. 2011;1:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roth F, Dhiab J, Boulinguiez A, et al. Assessment of PABPN1 nuclear inclusions on a largecohort of patients and in a human xenograft model of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 2022;144:1157‐1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kirkin V, Lamark T, Sou YS, et al. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:505‐516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Turco E, Savova A, Gere F, et al. Reconstitution defines the roles of p62, NBR1 and TAX1BP1 in ubiquitin condensate formation and autophagy initiation. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brisson JD, Gagnon C, Brais B, Côté I, Mathieu J. A study of impairments in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2020;62:201‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Müller T, Deschauer M, Kolbe‐Fehr F, Zierz S. Genetic heterogeneity in 30 German patients with oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. J Neurol. 2006;253:892‐895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mirabella M, Silvestri G, de Rosa G, et al. GCG genetic expansions in Italian patients with oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2000;54:608‐614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Blumen SC, Nisipeanu P, Sadeh M, et al. Epidemiology and inheritance of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy in Israel. Neuromuscul Disord. 1997;7:S38‐S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sveen ML, Thune JJ, Køber L, Vissing J. Cardiac involvement in patients with limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy type 2 and Becker muscular dystrophy. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1196‐1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ten Dam L, Frankhuizen WS, Linssen WHJP, et al. Autosomal recessive limb‐girdle and Miyoshi muscular dystrophies in the Netherlands: the clinical and molecular spectrum of 244 patients. Clin Genet. 2019;96:126‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. The proband (II‐2, family 3) with a (GCN)15 expansion exhibited extramuscular manifestations. Her cranial MRI revealed several lacunar infarctions in both hemispheres; spiral CT urography (SCTU) showed left ureterostenosis and right ectopic kidney with malrotation.

Figure S2. Coimmunostaining of PABPN1 and myosin heavy chains (MyHCs) on patient F2/III‐1 section. Scale bars: 200 μm.

Figure S3. Double‐label immunofluorescence shows colocalization of ubiquitin and the membrane‐associated protein dystrophin on several atrophy fibers in patient F6/II‐3. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Table S1. Genotypes of PABPN1 reported in OPMD patients of mainland Chinese.