Abstract

Sinorhizobium meliloti strains lacking BacA function are impaired in symbiosis with alfalfa host plants and display altered sensitivities to a number of compounds relative to wild-type strains. With the goal of finding clues to the currently unknown biological function(s) of BacA, we carried out a genetic analysis to determine which amino acids are critical for protein function and to attempt to ascertain whether the multiple phenotypes that result from a bacA-null allele were the result of a common cause or whether BacA has multiple functions. We have created a set of 20 site-directed mutants in which selected individual amino acids in bacA were replaced with glycine residues. The resulting mutants were characterized to determine how the various amino acid changes affected a number of phenotypes associated with loss of BacA function. Mutants H165G, W182G, D198G, and R284G had null phenotypes for all functions assayed, while mutants W57G, S83G, S231G, and K350G were indistinguishable from wild-type strains. The remaining 12 site-directed mutants demonstrate mixed phenotypic characteristics and fall into a number of distinctly different groups. These observations may be consistent with a role for BacA in multiple, nonoverlapping functions.

The bacterial protein BacA is a putative transporter of unknown function that is unusually interesting because it is absolutely required for both the virulence of an animal pathogen (18) and the symbiotic capacity of an agriculturally beneficial plant endosymbiont (9). As part of our efforts to elucidate the biological role of this intriguing protein, we have initiated a genetic dissection of BacA in the gram-negative bacterial endosymbiont of alfalfa, Sinorhizobium meliloti, because of its genetic tractability and the ease with which one can monitor its ability to establish a persistent infection with its eukaryotic host.

Nitrogen fixation is the end result of a complex symbiotic relationship between rhizobia and leguminous plants (23, 26), in which the bacterial partner is harbored within plant root nodules and exchanges reduced atmospheric nitrogen, necessary for host plant growth, for photosynthetically derived carbon compounds. bacA, a key gene involved in nodule development in the S. meliloti-alfalfa symbiosis, was isolated in a screen that identified bacterial mutants with symbiotic deficiencies (21). Rhizobia invade the nodules they elicit on legumes via specialized plant-derived structures called “infection threads.” Upon release from infection threads into plant membrane-bound compartments, wild-type rhizobia begin differentiating into nitrogen-fixing bacteroids. Electron microscopy has shown that S. meliloti mutants that lack bacA function invade nodules and are released properly from infection threads, but then appear to lyse and die at this intermediate developmental time point before they can differentiate and establish a functional symbiosis (9).

bacA mutants from Brucella abortus, an animal pathogen and close phylogenetic relative of S. meliloti (5), are similarly unable to persist in host tissues in experimentally infected mice and are unable to replicate and survive in vitro in murine macrophages (18). In the BALB/c mouse infection model, wild-type brucellae replicate to high levels in the liver and spleen during the first 2 weeks postinfection (24). After this time point, brucellae are hypothesized to switch from this acute phase of infection to a chronic one, in which tissue colonization decreases slightly and then plateaus, and brucellae undergo large changes in gene regulation and protein expression (19, 27–29). B. abortus bacA-null mutants behave like wild-type bacteria during the initial stages of host infection, but begin to be cleared by host mice beginning at around 2 weeks postinfection. Thus, bacA-deficient mutants of S. meliloti and B. abortus each have parallel survival patterns in their respective host organisms: both are able to invade and survive within their host environments at early developmental time points, but are unable to persist in their respective hosts during the chronic phase of infection, where they would each normally carry out long-term infections.

As originally suggested by Southern blots (9), a number of bacteria encode proteins that are related to the S. meliloti and B. abortus bacA gene products. The most closely related are the SbmA proteins of Escherichia coli (16) and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (A. Ichige and K. LeVier, unpublished data). When aligned pairwise, these four proteins show a high degree of similarity (79 to 97%), despite the substantial divergence of the α-Proteobacteria (S. meliloti and B. abortus) from the γ-Proteobacteria (E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium). The four proteins are approximately the same size (ca. 400 amino acids), and all are predicted to span the cytoplasmic membrane seven times (2). In the past 3 years, Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (1) searches of the sequence databases have shown that there is a second class of proteins related to BacA or SbmA (which will be referred to as “BacA-related proteins”). These BacA-related proteins are significantly more diverged from S. meliloti BacA (38 to 59% similarity), yet show large blocks of similar residues along long stretches of the proteins. These more diverged BacA-related proteins are all approximately 200 amino acids longer than the BacA/SbmA proteins and have highly conserved motifs common to bacterial ABC transport proteins (7) at their C termini. Interestingly, both S. meliloti and E. coli have a BacA-related protein as well as BacA/SbmA. The S. meliloti BacA-related protein ExsE was identified as a part of the sequence analysis of a cluster of genes involved in succinoglycan biosynthesis (GenBank accession no. AJ225561); however, exsE does not appear to play a role in synthesis of this polysaccharide and is not necessary for successful symbiosis with alfalfa (22). The E. coli BacA-related protein YddA is a predicted cytoplasmic membrane exporter of unknown function (20) that has been demonstrated to be regulated by the SOS response to DNA damage (4). The biological roles have not been determined for any of the BacA-related proteins, and it is not known if the more diverged BacA-related proteins perform the same function(s) as the BacA/SbmA proteins.

The molecular functions of the S. meliloti and B. abortus BacA proteins are not known, yet the proteins are of great interest, since they are critically important for these bacteria to establish their chronic intracellular relationships with their respective eukaryotic hosts. The presence of BacA-related proteins in a variety of bacteria, some of which are not known to enter into long-term associations with eukaryotic cells (e.g., Alcaligenes eutrophus and Synechocystis sp.) suggests that functions related to that of BacA must confer an important advantage in a variety of environmental conditions. The observation that E. coli sbmA mutants are resistant to bleomycin (32), microcin B17 (16), and microcin J25 (30) led to the suggestion that the SbmA protein is the transporter that brings these antibiotics into the cells. We have previously shown that the E. coli SbmA protein is functionally interchangeable with R. meliloti BacA (15) and had postulated that the symbiotic role of BacA might involve the transportation of some compound from the eukaryotic cytoplasm into the bacterial cell.

However, our more recent characterizations of additional phenotypes of the S. meliloti bacA mutant, including resistance to certain aminoglycoside antibiotics and increased sensitivity to ethanol and detergents, have led us to conclude that loss of BacA function affects the integrity of the bacterial cell envelope (15; G. P. Ferguson, K. LeVier, R. M. Roop, and G. C. Walker, unpublished data). In this paper, we describe a site-directed mutagenesis study of the S. meliloti bacA gene, which we carried out not only to identify critical amino acids of BacA, but also to investigate whether the various effects of bacA result from one underlying molecular function or from multiple genetically separable functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. S. meliloti strains were grown in liquid LB/MC (Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 2.5 mM MgSO4 and 2.5 mM CaCl2) or on LB or LB/MC plates at 30°C unless otherwise stated. E. coli strains were grown in LB at 37°C. When required, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml; streptomycin, 500 μg/ml; tetracycline, 10 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5-α | F−φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK−mK+) deoR thi-1 phoA supE44 λ−gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco BRL |

| S. meliloti | ||

| Rm8002 | Wild type; Rm1021 (SU47 Smr) pho | 21 |

| Rm8654 | ΔbacA; Rm8002 bacA654::Spc | 15 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRK404 | Control vector; Tcr broad-host-range vector | 6 |

| pJG51Aa | bacA+ plasmid; pRK404 carrying bacA+ | 9 |

| pJG52Ba | bacA+ in Bluescript SK+ Apr | 9 |

| pRK600 | Cmr pRK2013 npt::Tn9 | 8 |

| K8G | bacAK8G in pRK404 | This study |

| W57G | bacAW57G in pRK404 | This study |

| S83G | bacAS83G in pRK404 | This study |

| W87G | bacAW87G in pRK404 | This study |

| Y120G | bacAY120G in pRK404 | This study |

| N159G | bacAN159G in pRK404 | This study |

| H165G | bacAH165G in pRK404 | This study |

| W182G | bacAW182G in pRK404 | This study |

| Q193G | bacAQ193G in pRK404 | This study |

| R194G | bacAR194G in pRK404 | This study |

| D198G | bacAD198G in pRK404 | This study |

| F223G | bacAF223G in pRK404 | This study |

| S231G | bacAS231G in pRK404 | This study |

| T259G | bacAT259G in pRK404 | This study |

| R284G | bacAR284G in pRK404 | This study |

| N312G | bacAN312G in pRK404 | This study |

| Q332G | bacAQ332G in pRK404 | This study |

| K350G | bacAK350G in pRK404 | This study |

| F363G | bacAF363G in pRK404 | This study |

| R389G | bacAR389G in pRK404 | This study |

The orientation of the bacA+ gene in pJG51A and pJG52B is the same as that of the lacZ promoters in plasmids pRK404 and Bluescript SK+, respectively.

Construction of site-directed mutants.

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out via PCR with mutagenic primers to direct the change of a single amino acid to glycine. Plasmid pJG52B (9), consisting of the S. meliloti bacA gene flanked by 1,580 bp of upstream sequence and 181 bp of downstream sequence cloned into the BamHI site of pBluescript SK+, was used as template DNA. A pair of matched complementary synthetic mutagenic oligonucleotides (33- to 35-mers) containing the desired mutation flanked by at least 15 bp of wild-type sequence on either side of the mutation were used as primers for PCR amplification of the entire pJG52B plasmid for each mutant to be made. All codons for the targeted amino acids were changed to GGA (glycine), with the exception of tryptophan 57 (W57), which was changed to GGC (glycine) to prevent the formation of a BamHI site in bacA, which would have disrupted subsequent cloning steps. DNA was amplified with 50 ng of purified pJG52B DNA and 10 pmol of each primer with the Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase and buffer (Stratagene) with the following cycles: 95°C for 30 s, 95oC for 30 s, 44oC for 1 min, and 68oC for 14 min, with steps 2 through 4 repeated 18 times. The PCR products were digested with DpnI to cut parent plasmid DNA, and 10 μl of this DNA was transformed into competent E. coli DH5-α cells. DNA was prepared from Apr colonies, and clones with the correct restriction digest patterns were sequenced. Sequencing was performed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Biopolymers Laboratory with an ABI 377 sequencer and ABI BigDye kit version 2 AmpliTaq chemistry. Clones with the correct mutations were cut from pJG52B with BamHI and cloned into the BamHI-cut, calf alkaline phosphatase-treated, broad-host-range plasmid pRK404. The resulting plasmids were transformed into competent E. coli DH5-α cells and plated onto LB mixed with tetracycline (LB Tc), IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). DNA was prepared from white, Tcr colonies. Plasmids with correct restriction digest patterns were transferred into S. meliloti strains Rm8654 and Rm8002 via triparental conjugation with pRK600 to provide transfer functions (17).

Sensitivity assays.

For all assays, cultures were grown in LB/MC with antibiotics, adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 or 0.2, and washed once in 0.85% saline. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days, at which time, growth was evaluated or zones of bacterial growth inhibition were measured.

For bleomycin assays, 100-μl aliquots of cells adjusted to an OD600 of 0.2 were mixed with soft agar (nutrient broth, 8 g/liter; Bacto agar, 6.5 g/liter [both Difco]; NaCl, 5 g/liter) containing MC and tetracycline (MC Tc) and plated onto LB/MC Tc. After 30 min, sterile filter paper disks (6-mm diameter; Becton Dickinson) were placed on plates and then spotted with 1 μl of 10 mg of bleomycin A2 hydrochloride per ml (Calbiochem) diluted in 0.85% saline.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) assays were carried out as for the bleomycin assay, except soft agar and plates were not supplemented with MC. SDS (Gibco BRL) was diluted to 10% (wt/vol) in water, and disks were spotted with 5 μl.

For ethanol assays, an LB Tc plate containing 4% ethanol was spotted with 10 μl of cells adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1. An LB Tc plate was duplicate spotted with diluted cells as a control.

Gentamicin assays were carried out as for the SDS assay. Filter disks were spotted with 5 μl of a 5-mg/ml stock of gentamicin sulfate (Sigma) diluted in water. An LB Tc plate containing 15 μg of gentamicin per ml was spotted with cells prepared as for the ethanol assay, and an LB Tc plate was duplicate spotted with these cells as a control.

Plant nodulation assay.

Alfalfa (Medicago sativa cv. Iroquois) seeds (Agway, Inc., Plymouth, Ind.) were germinated, inoculated, and grown on Jensen's nitrogen-free medium as described previously (17). Plant height, leaf color, and nodule characteristics were scored at 4 weeks postinfection. Plants with green foliage and pink root nodules were scored as proficient for nitrogen fixation (Fix+). Fix− plants were stunted, pale yellow, and devoid of pink nodules.

Microdissection of nodules and quantitation of S. meliloti content.

For each set of nodules to be evaluated, six nodules were aseptically removed from plant roots with a razor blade. Nodules were placed on a clean petri dish under a dissecting microscope, the white tip was cut from the pink base of the nodule, and each of these fractions was processed separately. (The white portion of the nodule invariably included the topmost one-half to one-third of the nodule.) For the wild-type control, the uppermost one-third of the uniformly pink nodule was separated from the lower two-thirds of the nodule. For the Rm8654 bacA-null control, the small white nodules were not dissected and were processed whole. Nodules or nodule fractions were soaked in a solution of 50% Clorox bleach for 1 min in a well in a 96-well plate and then gently washed three times in sterile distilled water and moved to a well containing liquid LB supplemented with 0.3 M sucrose. Nodules were then crushed with forceps until completely macerated. Three stepwise 1:10 dilutions were then made in the same growth medium, and LB plates containing streptomycin (LB Sm) and LB Sm Tc plates were spotted with 25-μl aliquots of various dilutions to quantitate total rhizobium content and the content of Tcr plasmid-bearing rhizobia in nodules. Plates were scored after 4 days of growth at 30°C.

Microscopy.

Nodules from alfalfa plants inoculated 4 weeks prior were viewed under a Nikon ECLIPSE E600 microscope by using the bright field with nodules illuminated by an external fiber optic light source. Nodules were placed on a microscope slide covered with a single layer of green laboratory tape (VWR) for the best contrast. Images were collected with SPOT RT software version 3.0 (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, Mich.). Images were resized and optimized with Adobe Photoshop version 4.0.1 and combined in Canvas 5 (Deneba Systems).

RESULTS

Choice of residues for mutagenesis.

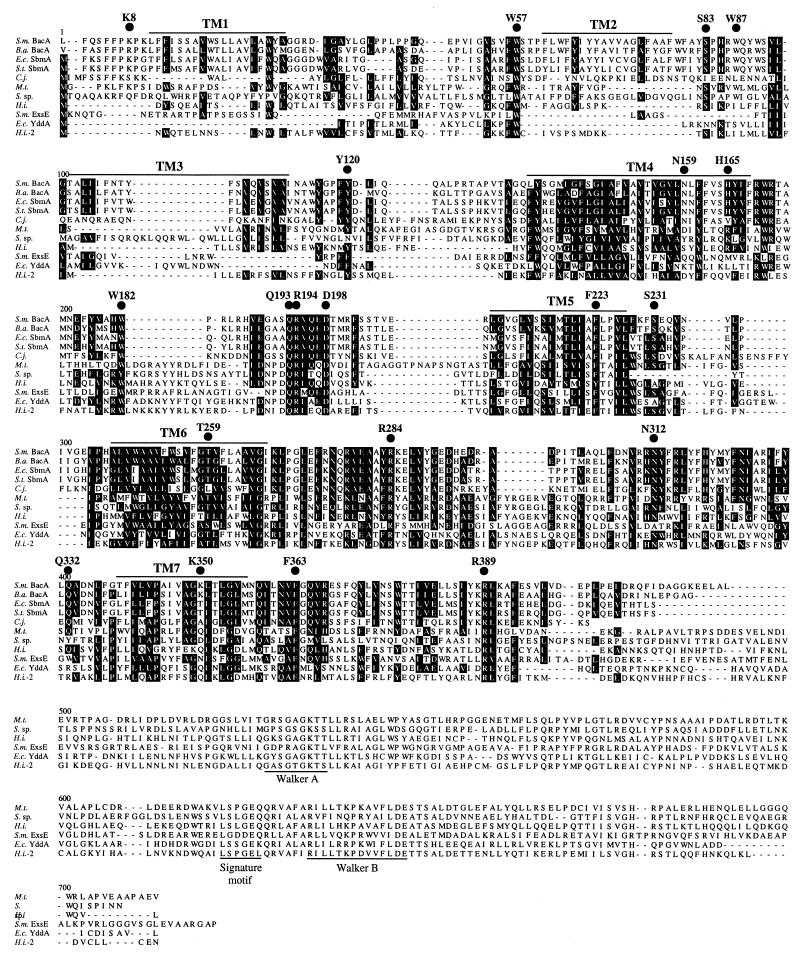

Figure 1 shows an alignment of 11 BacA/SbmA and BacA-related proteins from a variety of bacteria, in which the bottommost six proteins belong to the BacA-related grouping. The Campylobacter jejeuni protein lacks the C-terminal extended region of the BacA-related proteins and appears to be more similar to the tightly grouped BacA/SbmA proteins (40 to 59% similar). The C. jejeuni protein may be more diverged from the BacA/SbmA proteins from the top four organisms in the alignment than the four are from one another as a result of the much lower percent G+C content of its genome (30 to 38% for C. jejeuni versus 62% for S. meliloti, 56% for B. abortus, and 50 to 53% for E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of S. meliloti (S.m.) BacA (accession no. X73522) and ExsE (accession no. CAA12533), B. abortus (B.a.) BacA (accession no. AF244996), E. coli (E.c.) K-12 SbmA (accession no. P24212) and YddA (accession no. P31826), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (S.t.) SbmA (K. LeVier, unpublished data), and related hypothetical proteins identified in the organisms Campylobacter jejeuni (C.j.) NCTC 11168 (accession no. E81436), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.t.) RV1819C (accession no. Q50614), Synechocystis sp. (S. sp.) strain PCC6803 (accession no. BAA10424), and Haemophilus influenzae (H.i.) Rd (accession no. Q57335, P45221). The amino acid sequences were aligned with the MegAlign program of the DNA* package (DNASTAR, Inc.). Conserved residues are boxed in black, with conserved groupings as follows: acidic (DE), basic (HKR), aliphatic (AGILV), amide (NQ), aromatic (FWY), and hydroxyl (ST). The seven putative transmembrane (TM) domains of S. meliloti BacA are overlined and labeled. Consensus sequences for Walker boxes and the signature motif from ABC transporters are underlined and labeled. Solid, numbered circles above the S. meliloti sequence denote the amino acids selected for site-directed mutagenesis.

The alignments of the more diverged BacA-related proteins with S. meliloti BacA made it possible to identify amino acids that were conserved among the larger BacA family of proteins. Most of the 20 amino acids selected for mutagenic alteration were chosen on the basis of strong conservation among all 11 proteins used in the alignment in Fig. 1. Exceptions were made with K8, W87, and N159, in which the amino acid targeted was conserved in the closely related BacA/SbmA group, and K350, which was chosen because it was a basic amino acid in a mainly hydrophobic, membrane-spanning region of the protein. All mutations were made by changing the amino acid of interest to glycine.

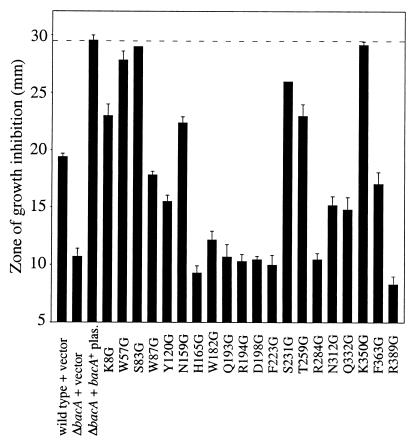

Sensitivity of site-directed mutants to bleomycin.

BacA/SbmA mutants from S. meliloti, B. abortus, E. coli, and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium are all more resistant to the glycopeptide anticancer agent bleomycin than are their isogenic parent strains (15, 18, 32; A. Ichige and K. LeVier, unpublished data). It has been proposed that BacA/SbmA serves as a transporter to bring this drug into cells (32), where it then leads to DNA damage and subsequent cell death (10). To determine whether the residues chosen in this study were involved in bleomycin sensitivity, we introduced the 20 site-directed mutants of S. meliloti bacA on the low-copy-number vector pRK404 into the Rm8654 ΔbacA background and tested for sensitivity to the drug. As shown in Fig. 2, providing the bacA+ gene on pRK404 made S. meliloti ΔbacA mutants more sensitive to killing by bleomycin. The responses of the strains carrying the 20 site-directed mutants to bleomycin ranged from close to the same degree of sensitivity to killing, as exhibited by Rm8654 ΔbacA carrying the wild-type bacA+ gene (W57G, S83G, S231G, and K350G), to levels of resistance equivalent to that of the ΔbacA mutant (H165G, W182G, Q193G, R194G, D198G, F223G, R284G, and R389G), with other mutants having intermediate phenotypes. Thus, a number of the residues altered in this study are necessary for the function of BacA that makes S. meliloti sensitive to bleomycin. With the exception of two mutants, all strains showed very clear delineations on plates between the zone of bacterial growth inhibition (proximal to where the bleomycin was spotted) and the zone of confluent bacterial growth. Q193G and R194G had very unusual zones of growth inhibition in which a small zone was completely devoid of visible bacterial growth (indicating bleomycin resistance), but this zone was surrounded by a much larger zone of very sparse bacterial growth, which was surrounded by a zone of confluent bacterial growth. In our previous studies, we had not encountered this resistance pattern. To be consistent with the method used to score all other plates in this assay, we measured the completely cleared innermost zone of growth inhibition on these plates.

FIG. 2.

Test for sensitivity to the antibiotic bleomycin. Site-directed mutants are in the Rm8654 ΔbacA mutant background. The dashed line indicates the level of bleomycin sensitivity of the positive control strain Rm8654(pJG51A) (ΔbacA plus pRK404 plasmid [plas.] carrying the bacA+ function). Strains with zones of growth inhibition greater than 25 mm were scored as having wild-type levels of bleomycin sensitivity. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Sensitivity of site-directed mutants to SDS and ethanol.

In a similar fashion, we then tested the mutants for sensitivity to other agents known to affect bacA mutants differently from the wild-type parent strain (15; G. P. Ferguson, K. LeVier, R. M. Roop, and G. C. Walker, unpublished data). The 20 mutants showed a variety of sensitivities to SDS (Fig. 3): four mutants showed severe detergent sensitivity (H165G, W182G, D198G, and R284G), and three more showed intermediate sensitivity (R194G, F223G and R389G). Twelve of the site-directed mutants grew as well on plates supplemented with 4% ethanol as did the bacA+ strain Rm8002, and four were as sensitive to ethanol as the ΔbacA mutant strain and showed no growth on plates (Table 2). Mutants R194G and R389G grew poorly on ethanol, and Q193G had medium to light growth. Overall, the degrees of sensitivity of the mutants to SDS and ethanol correlate well with one another.

FIG. 3.

Test for sensitivity to the detergent SDS. Site-directed mutants are in the Rm8654 ΔbacA mutant background. Strains with zones of growth inhibition less than 15.5 mm were scored as having wild-type levels of resistance to SDS. plas., plasmid. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

TABLE 2.

Bacterial growth in response to ethanol and gentamicin

| Straina | Result

onb:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 4% ethanol | Gentamicin (15 μg/ml) | |

| Wild type + vector | +++ | − |

| ΔbacA + vector | − | +++ |

| ΔbacA + bacA+ plasmid | +++ | − |

| K8G | +++ | − |

| W57G | +++ | − |

| S83G | +++ | − |

| W87G | +++ | + |

| Y120G | +++ | − |

| N159G | +++ | − |

| H165G | − | +++ |

| W182G | − | +++ |

| Q193G | ++ | ++ |

| R194G | + | +++ |

| D198G | − | +++ |

| F223G | ++ | +++ |

| S231G | +++ | − |

| T259G | +++ | − |

| R284G | − | +++ |

| N312G | +++ | − |

| Q332G | +++ | ++ |

| K350G | +++ | − |

| F363G | +++ | +++ |

| R389G | + | +++ |

Site-directed mutants are in the Rm8654 ΔbacA background.

+++, full growth; ++, medium to light growth; +, very light growth; −, no growth.

Sensitivity to gentamicin.

BacA mutants of S. meliloti had previously been shown to have increased resistance to low levels of the aminoglycoside antibiotics gentamicin, netilmicin, and tobramycin (15). We therefore tested the site-directed mutants for sensitivity to gentamicin by using a disk sensitivity assay. However, plates did not have clear boundaries between zones of bacterial growth versus nongrowth around gentamicin-containing filter disks, but rather had a gradient of increasing growth as cells grew more distant from the disk (data not shown; n = 3). There were clear visual differences between gentamicin-sensitive and -resistant strains, but the indistinct nature of the edges of the zones of growth inhibition made precise quantitation impossible. We therefore used plates containing 15 μg of gentamicin per ml spotted with the strains, evaluated them for growth, and saw a range of sensitivities for the various mutants (Table 2). As in the bleomycin assay, mutants Q193G and R194G had unusual behavior. Each was able to grow quite well on gentamicin-containing media, reminiscent of the ΔbacA strain, but also showed a large, indistinct gradient of growth inhibition in the crude disk sensitivity assay, suggesting that the strains were quite sensitive to gentamicin, like the wild-type strain. In general, however, strains resistant to bleomycin also showed gentamicin resistance.

Symbiotic properties of site-directed mutants.

To determine whether the residues chosen for this study were required for symbiosis, alfalfa plants were inoculated with site-directed mutants, and the mutants were evaluated 4 weeks postinfection for the ability to elicit nitrogen-fixing symbioses with host plants (Table 3). A mixture of phenotypes was observed with these point mutants. At 4 weeks postinfection, plants inoculated with wild-type S. meliloti (Rm8002 carrying the control vector pRK404) had dark green leaves, elongated pink nodules, and an average height of 13 cm, whereas plants inoculated with the ΔbacA mutant (Rm8654 plus vector) were yellow, had small round white nodules, and had an average height of 4 cm. Ten of the site-directed mutants cloned into vector pRK404 and introduced into the ΔbacA strain Rm8654 were clearly able to fix nitrogen (Fix+) when plants were inoculated with them. Pink nodules were present on all plants, leaf colors ranged from light to medium green, and plant heights varied from 4 to 11 cm. Mutants Q193G and N312G appeared to be greatly reduced in their capacity for nitrogen fixation, with each forming pale pink nodules on only a fraction of the plants in the group. All of the plants in these groups were short and pale green. The remaining eight mutants had Fix− phenotypes when plants were inoculated with them: all plants were short, yellow, and devoid of pink nodules.

TABLE 3.

Ability of bacterial strains to fix nitrogen in association with alfalfa plantsa

| Strainb | Fix phenotype | Avg plant ht (mean ± SD cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type + vector | + | 13.4 ± 3.8 |

| ΔbacA + vector | − | 3.8 ± 1.1 |

| ΔbacA + bacA+ plasmid | + | 8.2 ± 1.8 |

| K8G | + | 6.2 ± 2.5 |

| W57G | + | 10.7 ± 3.2 |

| S83G | + | 8.2 ± 0.8 |

| W87G | + | 7.6 ± 2.1 |

| Y120G | + | 7.2 ± 2.0 |

| N159G | + | 7.6 ± 3.3 |

| H165G | − | 3.5 ± 0.7 |

| W182G | − | 4.1 ± 1.2 |

| Q193G | ± | 4.5 ± 0.4 |

| R194G | − | 4.0 ± 0.8 |

| D198G | − | 3.9 ± 0.2 |

| F223G | − | 2.9 ± 0.5 |

| S231G | + | 6.8 ± 2.5 |

| T259G | + | 6.3 ± 2.3 |

| R284G | − | 4.2 ± 1.6 |

| N312G | ± | 3.7 ± 0.7 |

| Q332G | + | 4.0 ± 0.7 |

| K350G | + | 10.8 ± 2.8 |

| F363G | − | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

| R389G | − | 4.5 ± 1.0 |

n = 5 plants per group.

Site-directed mutants are in the Rm8654 ΔbacA background.

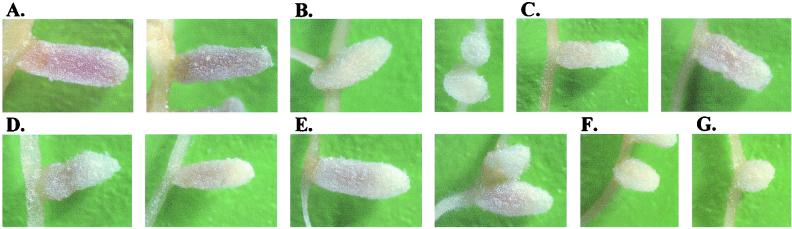

Interestingly, both the bacA-null mutant strain Rm8654 complemented with bacA+ on a plasmid (pJG51A; also referred to as bacA+ plasmid) and all of the site-directed mutants that were able to fix nitrogen in association with alfalfa elicited nodules that were visibly different from nodules elicited by wild-type S. meliloti (Fig. 4). Nodules elicited by wild-type bacteria were a uniform rich, vivid pink along the entire length of the nodule. However, nodules elicited by strains carrying the wild-type bacA gene or a Fix+ site-directed mutant on plasmid pRK404 were more pale pink in color and were only pink at the base of the nodule, with the upper one-third to one-half of the nodule completely white. No uniformly bright pink nodules were ever identified on any of the plants inoculated with a strain carrying the bacA+ function on the plasmid.

FIG. 4.

Alfalfa nodules elicited by various inoculum strains of S. meliloti. (A) Wild-type Rm8002 plus vector. (B) Rm8654 (ΔbacA) plus vector. (C) Rm8654 plus bacA+ plasmid (bacA+ in pRK404). (D to G) W57G in pRK404 in Rm8654 (D), K350G in pRK404 in Rm8654 (E), H165G in pRK404 in Rm8654 (F), and D198G in pRK404 in Rm8654 (G). Images were collected as indicated in Materials and Methods.

In order to determine if the lack of pink color at the tips of nodules was due to loss of the pRK404 (Tcr) plasmid carrying the bacA+ function during the 4-week time course of this experiment, nodules were microdissected to separate white from pink portions. Each of these nodule fractions was processed separately and evaluated for bacterial content. (Note that S. meliloti parent strains are Smr, whereas S. meliloti plus pRK404 strain and its derivatives are Smr Tcr). The overall trend seen in this somewhat crude assay was that nodules from plants inoculated with wild-type strain Rm8002 plus vector had 1.5 to 2 orders of magnitude more rhizobia in their tips than did nodules elicited by Fix+ strains carrying bacA+ function on pRK404 (data not shown). This ratio held true as well for plasmid-carrying (Tcr) rhizobia, with levels of Tcr bacteria present at low levels in wild-type nodules, but absent or barely detectable in nodules from all Fix+ site-directed mutant strains examined. Nodules with white tips also seemed to show a lack of Tcr bacteria in their tips relative to the pink bases of the same nodules, which did contain Tcr bacteria. Previous work has shown that bacA expression is at its highest levels in the early nodule zone, where bacteroid differentiation takes place (9). Thus a strong selection for bacA may only occur at this early symbiotic developmental time point, and the selection for bacA may be lost once basal levels of nitrogen fixation have ensued. Our data confirm this idea and suggest that in early nodule development (which corresponds to the base of nodules), BacA function is absolutely required, and thus a plasmid carrying bacA+ is selected for, but at later developmental time points, once differentiated bacteroids in the base of developing nodules have begun to successfully fix nitrogen, the selection for bacA+ becomes diminished and the pRK404 plasmid carrying bacA is lost.

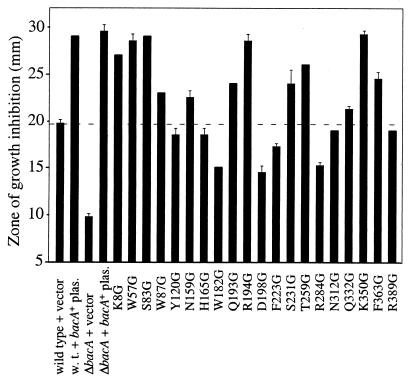

Dominant-negative properties of site-directed mutants.

Many of the BacA-related proteins identified in BLAST searches have the highly conserved motifs diagnostic of ABC transport proteins, and recent work has demonstrated that a number of ABC proteins within this superfamily function as dimers (for examples, see references 13 and 14). In a wild-type genetic background, overproduction of a nonfunctional variant of a protein that functions as a dimer could lead to the formation of mutant–wild-type heterodimers, leading to dominant-negative inhibition of wild-type protein function (11). We were interested in learning whether our site-directed bacA mutants carried on the low-copy-number plasmid pRK404 would behave in a dominant-negative fashion when moved into a bacA+ background (Rm8002).

Of the eight bacA mutants whose phenotypes most resembled those of a ΔbacA mutant in the assays performed in this study (H165G, W182G, Q193G, R194G, D198G, F223G, R284G, and R389G), four were clearly dominant for bleomycin sensitivity (W182G, D198G, F223G, and R284G) in this assay, because they increased the resistance of the bacA+ parent strain Rm8002 to bleomycin (Fig. 5). Mutants Y120G, H165G, N312G, and R389G also showed mild dominant characteristics. These results indicate that the altered BacA proteins encoded by these mutants are being expressed and are consistent with the suggestion that the dominance of these proteins is due to them forming dimers with wild-type BacA proteins. The behavior of the Q193G and R194G mutants was unexpected, since the bacA+ derivatives carrying these mutants showed a greater degree of sensitivity to bleomycin than the bacA+ parent alone. This observation suggests that the defects of these mutant BacA proteins can be suppressed when they interact with a wild-type BacA protein to form a dimer.

FIG. 5.

Test for dominant-negative phenotypes of site-directed mutants with respect to bleomycin sensitivity. Site-directed mutants are in the Rm8002 wild-type (w.t.) background. The dashed line indicates the level of bleomycin sensitivity of the Rm8002 wild-type strain. plas., plasmid. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

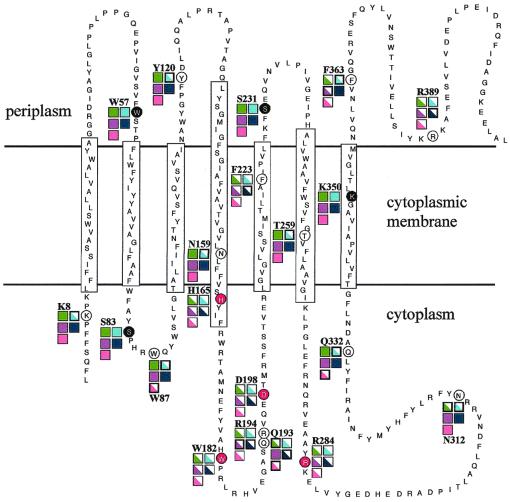

Work with the 20 individual site-directed mutants constructed for this study has shown that the S. meliloti BacA protein requires different subsets of nonoverlapping amino acids for full wild-type behavior in the various assays carried out in this work (summarized in Fig. 6). Of the assays performed in this work, the bleomycin sensitivity assay had the largest number of site-directed mutants with phenotypes that differed from those of wild-type strains. The data generated here are not inconsistent with the previous hypothesis that BacA serves as a transporter used by bleomycin to gain entry into S. meliloti cells and that strains lacking full BacA function are unable to bring the drug into cells at wild-type levels and are therefore more resistant to bleomycin killing. However, several facts suggest that it would be worth considering alternative hypotheses for the molecular basis of the bleomycin resistance of bacA mutants. The mode of bleomycin transport has not been fully elucidated in any bacterial system to date, and the uptake of this drug is affected by changes in the bacterial cell membrane. In E. coli, mutations in three separate steps in the biosynthetic pathway for ubiquinone, a part of the cytoplasmic membrane electron transport chain that plays an important role in the maintenance of membrane potential, all showed increased resistance to phleomycin E, a bleomycin analog (3).

FIG. 6.

Summary of phenotypes of 20 site-directed mutants overlaid on the predicted topology model of S. meliloti BacA (9). The circled amino acids were selected for site-directed mutagenesis and changed to glycine. Changes made to amino acids circled in black led to strict bacA+ wild-type behavior in all assays, changes to those circled in red led to ΔbacA mutant behavior in all assays, and changes to those circled in white showed mixed phenotypic characteristics. Boxes proximal to site-directed mutations indicate phenotypes for specific assays. Solid boxes indicate wild-type behavior for the specified assay, and half-filled boxes indicate ΔbacA mutant behavior. Boxes outlined in boldface black indicate an intermediate phenotype, in which the phenotype differed significantly from wild-type behavior. Color coding for specific assays is as follows: green, ability to fix nitrogen; aqua blue, bleomycin sensitivity; purple, SDS sensitivity; navy blue, ethanol sensitivity; pink, gentamicin sensitivity.

We monitored the site-directed mutants constructed here for sensitivity to gentamicin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic to which bacA mutants had previously been shown to have low levels of resistance (15). In this study, single amino acid changes in 8 out of 20 site-directed mutants led to significantly increased gentamicin resistance relative to the wild-type strain. Despite much study, the mechanism by which aminoglycosides penetrate the cytoplasmic membranes of gram-negative bacteria has not yet been determined, but under normal growth conditions, it appears to be dependent on Δψ, the electrical component of the proton motive force (31). The cytoplasmic membrane electron transport chain component ubiquinone itself has been proposed to be directly involved in aminoglycoside movement across the cytoplasmic membrane.

Work in this study has shown that sensitivity to bleomycin and gentamicin is similarly affected by mutational alteration of BacA, with the exceptions of mutants Y120G and N312G, which have intermediate resistance to bleomycin, but wild-type levels of sensitivity to gentamicin. Additionally, mutants Q193G and R194G each had very odd growth patterns in response to these drugs in disk sensitivity assays. However, the overall similarity of responses of mutants to bleomycin and gentamicin may be accounted for by the fact that, although structurally dissimilar, both drugs are hydrophilic and cationic and may be taken into cells by a similar mode of action that is dependent on cytoplasmic membrane potential. It has also been proposed that aminoglycosides cross the outer membrane barrier of gram-negative bacteria by first binding to lipopolysaccharide and then disrupting and/or disorganizing the outer membrane, a mechanism also used by the polycationic polymyxin B (31). This mechanism may also be employed by bleomycin and gentamicin in wild-type S. meliloti cells.

The majority of site-directed mutants with the strongest bacA-null phenotypes cluster to what are predicted to be cytoplasmic loops of the BacA protein. This may suggest that one requirement for BacA that could manifest itself in the multiple phenotypes seen for this protein is for an interaction with an as yet unidentified cytoplasmic protein. A strong possibility would be for an ATPase necessary to form the full complement of an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport system. In bacteria, ABC transporters use the energy of ATP binding and hydrolysis to energize the transport of a wide range of substrates across the cytoplasmic membrane (20, 33). The basic unit of an ABC transporter is made up of a hydrophobic transmembrane domain (TMD) that spans the cytoplasmic membrane multiple times and forms a putative channel, and a highly conserved cognate soluble ABC-ATP-binding domain (ABC-ATPase) peripherally associated at the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane. The ABC-ATPases are highly conserved proteins that are present in all organisms and have characteristic conserved A and B sites that form an ATP-binding pocket (12). In bacteria, the TMD and ABC-ATPase domains can be encoded by the genes of separate polypeptides, the products of which assemble into a multicomponent membrane-bound complex. The very strong conservation seen in the last two proposed cytoplasmic loops of BacA/SbmA proteins may reflect the interaction of these regions of BacA with a cognate ABC- ATPase. The BacA-related proteins, which carry both a TMD and an ABC-ATP-binding domain on the same polypeptide, show strong similarity to S. meliloti BacA in these conserved cytoplasmic loops as well. This may be an indication that the BacA-related proteins fold in such a way that their own ABC-ATPases bind to the cytoplasmic loops of the TMD portion of the same protein.

Recent work with a number of proteins has confirmed the model that ABC transporters function as dimers, with each half of the dimer consisting of one membrane-spanning TMD and one ATPase (for examples, see references 14 and 25). This situation is expected to be the case for other ABC transporters as well. Dimerization has also been demonstrated for Rad50, an ABC protein involved not in transport, but in DNA double-strand break repair (13). ATP promotes the dimerization of two Rad50 catalytic domains in a head-to-tail conformation, in which the highly conserved signature motif from each subunit binds the ATP bound to the opposite half of the dimer, with both ATP molecules buried in the dimer interface. The fact that our work with several site-directed mutants of the S. meliloti BacA protein with alterations in only a single amino acid led to dominant-negative effects when expressed in a wild-type background is consistent with the hypothesis that BacA (presumably bound to a cognate ABC-ATPase) may be acting as a dimer, with the dominant-negative phenotype seen suggesting that heterodimers formed between wild-type BacA and some site-directed mutants lead to defects in BacA function.

Alternatively, BacA could function as a transporter, but use a different, non-ATPase mode of energization for this process, such as from the proton motive force. The highly conserved cytoplasmic loops of BacA may be necessary for interactions with a non-ATPase protein of unknown function or may be involved in recognition or binding of a transport substrate. The BacA-related proteins could carry out the same function as BacA/SbmA proteins, but may have evolved to energize this process in an ATP-dependent manner instead.

Of the 20 site-directed mutants constructed for this study, 12 mutants had intermediate phenotypes that differed from the wild-type phenotype in at least one of the assays and showed a variety of patterns of phenotype mixtures. Such intermediate phenotypes could arise from alleles causing different degrees of loss of a single BacA function, or they could arise from individual mutations differentially affecting different functions of the BacA protein. The strongest trends seen in the assays performed here are that mutations that affect bleomycin resistance generally also affect gentamicin resistance to some degree, and mutants that are sensitive to ethanol are generally also sensitive to SDS. The bleomycin resistance assay seems to be the most sensitive assay, followed by the tests for nitrogen fixation ability and gentamicin sensitivity.

In the case of the phenotypes of some of the mutants examined in this study, it would be easier to account for the data by postulating that BacA has more than one function. For example, mutant N312G behaves like wild-type strains for sensitivity to SDS, ethanol, and gentamicin, but has intermediate sensitivity to bleomycin and carries out very inefficient nitrogen fixation in association with alfalfa. Mutant Q332G has almost identical bleomycin sensitivity to N312G, but grows moderately well on 15 μg of gentamicin per ml, like ΔbacA mutant strains, and is apparently wild type with regard to symbiosis. Mutants F223G and R389G each have ΔbacA mutant responses in all assays, except for the test for ethanol sensitivity, in which both strains show some wild-type capacity for growth. Mutant F363G shows intermediate phenotypes for sensitivity to bleomycin and SDS and behaves like a ΔbacA mutant for sensitivity to gentamicin and symbiosis with alfalfa, but has full wild-type levels of resistance to ethanol. Mutant R194G primarily has ΔbacA behavior in all assays, and Q193G has intermediate or null behavior in all assays, except for sensitivity to ethanol and SDS. However, both strains have very unusual growth patterns in response to bleomycin and gentamicin in disk sensitivity assays, and both lead to distinctly wild-type levels of bleomycin sensitivity when these mutations are moved into the wild-type Rm8002 background. Mutations in Q193, R194, and possibly F363 appear to be in a minority class that lead to strong ΔbacA characteristics, yet can apparently be suppressed by wild-type BacA in a dominant-negative assay. For the mutants discussed above, it is not easy to explain the differences in phenotype combinations by different degrees of loss of a single function.

We have demonstrated that single amino acid changes in the BacA protein can profoundly influence both responses to stressful compounds and symbiotic interactions with alfalfa plants. The data from the assays performed here are compatible with bacA mutants having some bacterial cell surface alterations, but the data from some of the mutants with intermediate phenotypes suggest that the situation could be more complex and that BacA carries out multiple functions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mary Lou Pardue and Janet George for help with nodule imaging. We also thank Gail Ferguson and Brett Pellock for critical review of the manuscript and Gail Ferguson for collaboration and discussion regarding some of the mutant phenotypes.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant GM31030 to G.C.W. from the National Institute of General Medicinal Science. K.L. was supported by a U.S. Department of Energy-Biosciences Fellowship from the Life Sciences Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claros M G, von Heijne G. TopPredII: an improved software for membrane protein structure predictions. Comput Appl Biol Sci. 1994;10:685–686. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collis C M, Grigg G W. An Escherichia colimutant resistant to phleomycin, bleomycin, and heat inactivation is defective in ubiquinone synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4792–4798. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4792-4798.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown P O, Hanawalt P C. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2001;158:41–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Ley J, Mannheim W, Segers P, Lievens A, Denijn M, Vanhoucke M, Gillis M. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid cistron similarities and taxonomic neighborhood of Brucellaand CDC group Vd. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1987;37:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ditta G, Schmidhauser T, Yakobson E, Lu P, Liang X W, Finlay D R, Guiney D, Helinski D R. Plasmids related to the broad host range vector, pRK290, useful for gene cloning and for monitoring gene expression. Plasmid. 1985;13:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(85)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fath M J, Kolter R. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:995–1017. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.995-1017.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finan T M, Kunkel B, De Vos G F, Signer E R. Second symbiotic megaplasmid in Rhizobium meliloticarrying exopolysaccharide and thiamine synthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:66–72. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.66-72.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glazebrook J, Ichige A, Walker G C. A Rhizobium meliloti homolog of the Escherichia colipeptide-antibiotic transport protein SbmA is essential for bacteroid development. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1485–1497. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecht S M. Bleomycin: new perspectives on the mechanism of action. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:158–168. doi: 10.1021/np990549f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herskowitz I. Functional inactivation of genes by dominant negative mutations. Nature. 1987;329:219–222. doi: 10.1038/329219a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland I B, Blight M A. ABC-ATPases, adaptable energy generators fueling transmembrane movement of a variety of molecules in organisms from bacteria to humans. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:381–399. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopfner K P, Karcher A, Shin D S, Craig L, Arthur L M, Carney J P, Tainer J A. Structural biology of Rad50 ATPase: ATP-driven conformational control in DNA double-strand break repair and the ABC-ATPase superfamily. Cell. 2000;101:789–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung L W, Wang I X, Nikaido K, Liu P Q, Ames G F, Kim S H. Crystal structure of the ATP-binding subunit of an ABC transporter. Nature. 1998;396:703–707. doi: 10.1038/25393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichige A, Walker G C. Genetic analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti bacA gene: functional interchangeability with the Escherichia coli sbmAgene and phenotypes of mutants. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:209–216. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.209-216.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavina M, Pugsley A P, Moreno F. Identification, mapping, cloning and characterization of a gene (sbmA) required for microcin B17 action on Escherichia coliK12. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:1685–1693. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-6-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leigh J A, Signer E R, Walker G C. Exopolysaccharide-deficient mutants of Rhizobium melilotithat form ineffective nodules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6231–6235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeVier K, Phillips R W, Grippe V K, Roop II R M, Walker G C. Similar requirements of a plant symbiont and a mammalian pathogen for prolonged intracellular survival. Science. 2000;287:2492–2493. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin J, Ficht T A. Protein synthesis in Brucella abortusinduced during macrophage infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1409–1414. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1409-1414.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linton K J, Higgins C F. The Escherichia coliATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:5–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long S, McCune S, Walker G C. Symbiotic loci of Rhizobium meliloti identified by random TnphoAmutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4257–4265. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4257-4265.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long S, Reed J W, Himawan J, Walker G C. Genetic analysis of a cluster of genes required for synthesis of the calcofluor-binding exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4239–4248. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4239-4248.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long S R. Genes and signals in the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:69–72. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montaraz J A, Winter A J. Comparison of living and nonliving vaccines for Brucella abortusin BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1986;53:245–251. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.2.245-251.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikaido K, Ames G F. One intact ATP-binding subunit is sufficient to support ATP hydrolysis and translocation in an ABC transporter, the histidine permease. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26727–26735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niner B M, Hirsch A M. How many Rhizobium genes, in addition to nod, nif/fix, and exo, are needed for nodule development and function? Symbiosis. 1998;24:51–102. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Gorvel J-P. Brucella abortusinvasion and survival within professional and nonprofessional phagocytes. Adv Cell Mol Biol Membranes Organelles. 1999;6:201–232. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porte F, Liautard J-P, Köhler S. Early acidification of phagosomes containing Brucella suisis essential for intracellular survival in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4041–4047. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4041-4047.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rafie-Kolpin M, Essenberg R C, Wyckoff J H., III Identification and comparison of macrophage-induced proteins and proteins induced under various stress conditions in Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5274–5283. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5274-5283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salomón R A, Farias R N. The peptide antibiotic microcin 25 is imported through the TonB pathway and the SbmA protein. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3323–3325. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3323-3325.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taber H W, Mueller J P, Miller P F, Arrow A S. Bacterial uptake of aminoglycoside antibiotics. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:439–457. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.439-457.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yorgey P, Lee J, Kordel J, Vivas E, Warner P, Jebaratnam D, Kolter R. Posttranslational modifications in microcin B17 define an additional class of DNA gyrase inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4519–4523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young J, Holland I B. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters-revisited five years on. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1461:177–200. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]