Abstract

Background

Ginsenoside compound K (CK) stimulated activation of the PI3K-Akt signaling is one of the major mechanisms in promoting cell survival after stroke. However, the underlying mediators remain poorly understood. This study aimed to explore the docking protein of ginsenoside CK mediating the neuroprotective effects.

Materials and methods

Molecular docking, surface plasmon resonance, and cellular thermal shift assay were performed to explore ginsenoside CK interacting proteins. Neuroscreen-1 cells and middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model in rats were utilized as in-vitro and in-vivo models.

Results

Ginsenoside CK interacted with recombinant human PTP1B protein and impaired its tyrosine phosphatase activity. Pathway and process enrichment analysis confirmed the involvement of PTP1B and its interacting proteins in PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. PTP1B overexpression reduced the tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) after oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R) in neuroscreen-1 cells. These regulations were confirmed in the ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere of the rat brains after MCAO/R. Ginsenoside CK treatment reversed these alterations and attenuated neuronal apoptosis.

Conclusion

Ginsenoside CK binds to PTP1B with a high affinity and inhibits PTP1B-mediated IRS1 tyrosine dephosphorylation. This novel mechanism helps explain the role of ginsenoside CK in activating the neuronal protective PI3K-Akt signaling pathway after ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Keywords: ginsenoside CK, PTP1B, ischemia-reperfusion injury, stroke, PI3K-Akt signaling

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Ginsenoside Rd might be a promising neuroprotective agent to alleviate ischemic stroke damage [1]. It can reduce ischemia-induced neural apoptosis [2,3] and microglial activation [4,5]. The activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signaling has been considered one of the major underlying mechanisms [6]. Ginsenoside compound K (CK) is the major metabolite of ginsenoside Rd [7,8]. It is more bioavailable and soluble than the parent forms [7,8]. It protects neurons against oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R) injury via promoting cell viability and suppressing ROS generation, mitochondrial damage, and Ca2+ overload [9]. The neuronal protection of ginsenoside CK was also confirmed in the mice model of stroke [10,11]. However, the underlying mediators remain poorly understood.

Insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) is a signal transducer of the receptor tyrosine kinase for insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) signaling pathways [12]. It is ubiquitously expressed in different cell types, including neurons [13]. Insulin or IGF1 can attenuate brain neuronal apoptosis induced by oxidative stress [14,15]. The mechanisms include elevating insulin receptor/IGF1 receptor signaling-mediated gene transcription (such as elevating hexokinase-II and Bcl2 expression), improving neuronal glucose metabolism, activating IGF-1R/PI3K/Akt signaling and inhibiting neuronal Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK) signaling [14,15].

IRS1 phosphorylation is necessary for its downstream effects [16]. IRS1 serine phosphorylation is usually associated with insulin resistance [17]. In comparison, tyrosine-phosphorylated IRS1 bind to and activate PI3K, subsequently activating the serine/threonine kinase Akt [18]. Dephosphorylation of the tyrosine residues of IRS1 by Protein-tyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP1B, encoded by PTPN1 gene) can lead to deactivation and insulin resistance [19]. Inhibition of PTP1B reactivates IRS1-mediated PI3K/Akt [20]. One recent study revealed that ginsenoside CK could improve insulin resistance in adipose tissue by promoting the expression of IRS1/PI3K/Akt [21].

The regulatory effects of a specific ginsenoside compound primarily rely on its docking proteins [22,23]. This study aimed to explore the docking protein of ginsenoside CK mediating the neuroprotective effects.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Neuroscreen-1 cells (a subclonal line of PC-12; which is derived from transplantable rat pheochromocytoma) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Wortham, TX, USA) and cultured as recommended. Ginsenoside CK (purity: >99%), and sc-222227 were purchased from Selleck (Houston, TX, USA).

Lentiviral rat PTPN1 (NM_012637.2) overexpression particles were constructed based on pHBLV-CMVIE-IRES-Puro plasmids. Lentiviruses for infection were produced using psPAX2 packaging plasmid and pMD2.G envelope plasmid, as described previously [24]. Neuroscreen-1 cells were infected with the lentiviruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5, for transient PTP1B overexpression. Uninfected cells were eliminated by adding 2 mg/ml puromycin for 48 h before use.

2.2. Oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R) treatment

Neuroscreen-1 cells were treated with 150 ng/ml NGF for 96 h to induce neuronal differentiation, following the strategy recommended previously [25]. Then, the cells were cultured in a glucose-free culture medium with or without the presence of ginsenoside CK (10 or 40 μM) or sc-222227 (5 μM) in a hypoxic chamber (1% O2, 5% CO2 and 94% N2) for 3 h. Afterward, cells were incubated for 24 h under normoxia in a complete medium. The same concentrations of ginsenoside CK and sc-222227 were also administered during the normoxic culture.

2.3. Western blotting and cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

Western blotting was performed following the methods described previously [24]. 30 μg protein per sample was separated and detected. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-PTP1B (1:2000, 11334-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-Akt (1:1000, #4685, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) (p-Akt) (1:2000, #4060, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-ERK1/2 (1:1000, #4695, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-p44/42 ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (1:1000, #9101, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-IRS1 (Tyr1222) (1:1000, #3066, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-IRS1 (human Tyr612, rat/mouse Tyr608) (1:1000, 44-816G, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-Bax (1:5000, 50599-2-Ig, Proteintech), anti-Bcl2 (1:2000, 12789-1-AP, Proteintech) and anti-β-actin (1:5000, 66009-1-Ig, Proteintech). The protein signal bands were developed using chemiluminescence reagents (BeyoECL Star, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Protein expression was semi-quantified by densitometry and normalized to β-actin using ImageJ software (version 1.37, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

CETSA was conducted following the methods introduced previously [26]. 40 μM ginsenoside CK or vehicle control (DMSO) was incubated with the lysate supernatant collected above for 1 h at room temperature. Then, aliquots of the samples (50 μl) were treated with different temperatures (45, 55, 60, 65, and 70 °C) for 5 min, using a thermal cycler and cooled under room temperate for 5 min. Then, the samples were centrifuged (20,000g for 20 min at 4 °C) again. The supernatants were subjected to western blotting assays using anti-PTP1B.

2.4. Flow cytometric analysis

The proportions of apoptotic Neuroscreen-1 cells in each treatment group were measured by flow cytometry using Annexin V/PI staining. PI staining was applied to assess the integrity of the cellular membrane. In brief, Neuroscreen-1 cells (with or without PTP1B overexpression) were cultured in 6-well plates and were subjected to OGD/R, with the presence of ginsenoside CK or sc-222227. Then, cells were harvested, washed and incubated with the 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC and 10 μl of PI (20 μg/ml) in 100 μl 1 × binding buffer for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Then, 400μl PBS was added to each sample. Cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company, San Diego, CA, USA), with 488-nm excitation and a 525-nm filter for FITC and a 620-nm filter for PI detection. This staining help separate three subsets of cells: viable cells (annexin V-/PI-), early apoptotic cells (annexin V+/PI-), and late apoptotic or necrotic cells (annexin V+/PI+).

2.5. Molecular docking between Ginsenoside CK and its interacting proteins

The ginsenoside CK-protein interactions were predicted using TargetNet (http://targetnet.scbdd.com/) [27]. The proteins with a probability score higher than 0.5 were identified as candidates. The atomic interaction between ginsenoside CK and PTP1B was estimated using CB-Dock (http://clab.labshare.cn/cb-dock/php/index.php) [28], based on the 1EEO structure of PTP1B in RCSB PDB (PDB https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb1EEO/pdb).

2.6. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis

The binding affinity of ginsenoside CK to recombinant PTP1B was measured using a Biacore T200 (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Human recombinant PTP1B protein (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) was captured on a CM5 chip via a standard amine coupling procedure. Binding sensorgrams were recorded by serially injecting diluted ginsenoside CK over the immobilized PTP1B surface. Then, equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) value was calculated with a steady affinity state model.

2.7. Pathway and process enrichment analysis

PTP1B interacting proteins were identified using data provided by Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org/). The genes encoding PTP1B and its interacting proteins were subjected to pathway and process enrichment analysis using Metascape [29]. The top 20 most statistically significant terms were identified.

2.8. PTPase activity assay

The activity of recombinant PTP1B protein (active, ab51277, Abcam) was performed in 96-well plates, following the method introduced previously [30]. 99 μL reaction buffer solution, which consisted of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM MnCl2, and para-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) (1, 2, 3, or 4 mM) was prepared with or without the presence of ginsenoside CK (10 μM or 40 μM). Then, 1 μL enzyme solution containing recombinant PTP1B protein (1 mg/mL) was mixed in each well and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Reactions were quenched by adding NaOH solution (10 μL, 0.1 M). The absorbance was recorded at 405 nm using a microplate every three minutes. Lineweaver-Burk double reciprocal plot was used to study the kinetic behavior. The enzymatic velocity was calculated using the time-Δabsorbance (Δabs) data. Relative enzyme activity was calculated based on five repeats of three independent tests.

2.9. Middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in rats

Animal studies were performed following the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition) and were approved by the ethics committee of Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, China. The adeno-associated virus 5 (AAV5) based rat PTPN1 (NM_012637.2) overexpression AAVs (AAV5-PTP1B) were produced by Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) (Viral titer: 1.4 × 1012 GC/ml). Male Sprague-Dawley rats (220-250 g) were purchased from Chengdu Dashuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Chengdu, China). MCAO models in rats were constructed as we described previously [24]. Rats were randomly divided into four groups [1]: Sham group (n = 6), with surgery but no occlusion [2]; AAV5 vector group + MCAO (n = 6) [3]; AAV5-PTP1B + MCAO group [4]; AAV5-PTP1B + MCAO + Ginsenoside CK treatment (10 or 50mg/kg, intraperitoneally 30 min before occlusion). After 90 min occlusion, reperfusion was followed by 72 h of reperfusion. Then, the brain tissues obtained from each group were collected for 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining to determine the infarct volume. For AAV5 infection groups, rats were anesthetized and fixed to a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting, Kiel, WI, USA). For each group, a total of 5 μl AAV solution was injected into the right cerebral ventricle of rats, using a Hamilton microsyringe, with the following position coordinates: anterior-posterior (AP) 1.1 mm from bregma; medial-lateral (ML) 1.5 mm from midline; and dorsoventral (DV), 4.0 mm. The rate of the injection was 0.5 μl/min. Subsequently, the needle was fixed for 5 min and slowly removed within 2 min. 21 days post-injection, rats were subjected to MCAO operation. TUNEL staining, Nissl staining and H&E staining were conducted as we previously described [24].

2.10. Immunofluorescent staining

After MCAO/R, rat brains were removed, embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned into 10 μm thick slices. Then, the slices were subjected to deparaffinization, rehydration and antigen retrieval. Afterward, the slices were permeabilized in 0.4% Triton X-100 in PBS (with 1% goat serum) for 10 min, and blocked with 5% goat serum in PBST for 30 min. The slices were incubated with rabbit anti-phospho-IRS1 (Tyr608) (1: 100, 44-816G, ThermoFisher Scientific) and mouse NeuN monoclonal Antibody (1:200, 66836-1-Ig, Proteintech) overnight at 4°C. Then, the slices were washed and incubated with CoraLite594-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (1:200) and CoraLite488-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (1:200) for 30 min at room temperature. After 3 times washing with PBS, the slices were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wortham, TX, USA). The fluorescence was examined with a confocal microcopy Olympus fluorescence FV1000 microscope.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data were integrated and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.01 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Multiple group comparison was conducted using one-way ANOVA test, followed by the Tukey post hoc test. Welch's unpaired t-test was used for comparison between two groups. Results are expressed as mean ± standard derivation (SD). p < 0.05 was considered of significance.

3. Results

3.1. Ginsenoside CK interacts with PTP1B with a high affinity

Since the molecular mechanisms supporting the neural protective effect of ginsenoside CK (Fig. 1A) on ischemic/reperfusion injury are not well understood, we further investigated its interacting proteins. Bioinformatic prediction was conducted using TargetNet [27] to identify potential ginsenoside CK docking proteins. Among the high-potential candidates (probability score > 0.5) (Fig. 1B), PTP1B (encoded by PTPN1 gene) has been characterized as a novel therapeutic target in ischemic stroke [[31], [32], [33]]. It shows stimulative effects on PERK signaling and inhibitive effects on p-Akt signaling [[31], [32], [33]]. Therefore, we typically focussed on this molecule. Molecular docking analysis was then performed using the 1EEO structure of PTP1B in RCSB PDB (PDB https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb1EEO/pdb). Results indicated that PTP1B has multiple ginsenoside CK binding sites. One predicted binding site contains Y46, D181 and F182 (Fig. 1C–D, red arrows). These residues are critical for substrate binding and hydrolytic catalysis [34,35]. Therefore, we hypothesized that ginsenoside CK might interact with PTP1B and impair its physiological function. To validate the predicted interaction, we used surface plasmon resonance technology. Ginsenoside CK interacted with recombinant human PTP1B protein in a concentration-dependent manner, with an estimated KD of 0.89 μM (Fig. 1E). In the CETSA assay, ginsenoside CK increased the thermal stability of PTP1B compared to the DMSO control (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Ginsenoside CK binds to PTP1B with a high affinity. A. Ball and stick structure model of ginsenoside CK. B. Predicted proteins with high binding potential with ginsenoside CK. C-D. Molecular docking of between ginsenoside CK and PTP1B. The predicted binding positions covering the critical substrate binding and catalyzing sites of PTP1B protein were provided in Fig. D. E. SPR analysis of Ginsenoside CK binding to human recombinant PTP1B protein. F. Representative images of CETSA of PTP1B with 40 μM ginsenoside CK or DMSO control.

3.2. Ginsenoside CK reduces PTP1B-mediated inhibition of PI3K-Akt signaling

PTP1B is a well-characterized enzyme catalyzing dephosphorylation [35]. Using data from Uniprot, we identified the known PTP1B interacting proteins (Fig. 2A). Then, the genes encoding these proteins and PTPN1 were subjected to pathway and process enrichment analysis using Metascape [29]. Notably, GO:0051896: regulation of protein kinase B (Akt) signaling and M271: PID_PI3K_PLC_TRK_PATHWAY are among the top 20 enriched pathways (Fig. 2B). Activation of PI3K-Akt signaling has been validated as one of the most critical signaling pathways for neural survival after stroke [6,36]. However, PTP1B is a negative regulator of this pathway by dephosphorylating multiple tyrosine kinases and their docking proteins upstream of PI3K/Akt signaling [[37], [38], [39]]. Therefore, we investigated whether ginsenoside CK treatment abolishes the inhibitive effect of PTP1B on PI3K-Akt signaling.

Fig. 2.

Ginsenoside CK reduces PTP1B-mediated inhibition of PI3K-Akt signaling. A. A summary table of PTP1B interacting proteins, which are obtained from UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/). B. Summary of the top 20 statistically significant terms in the pathway and process enrichment analysis. 31 genes (PTPN1 and the genes encoding PTP1B interacting proteins) were subjected to the express analysis in Metascape. C-E. Representative image (C) and quantitation (D-E) of western blot analysis of PTP1B, p-Akt, Akt, p-ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 expression in NEUROSCREEN-1 cells after OGD (3h)/R (24h), with or without the presence of ginsenoside Rd or sc-222227 (5 μM). F–H. Representative image (F) and quantitation (G-H) of western blot analysis of PTP1B, p-Akt, Akt, p-ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 expression in NEUROSCREEN-1 cells with PTP1B overexpression after OGD (3h)/R (24h), with or without the presence of ginsenoside Rd or sc-222227 (5 μM). Quantitative results were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Neuroscreen-1 cells were subjected to OGD/R, with or without the treatment of ginsenoside CK or sc-222227 (a PTP1B inhibitor). Western blot showed that OGD/R induced upregulation of PTP1B. It is also associated with spontaneous upregulation of p-AKT and p-ERK1/2. Ginsenoside CK or sc-222227 treatment significantly increased the expression of p-AKT and p-ERK1/2 (Fig. 2C–E). PTP1B overexpression suppressed the phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 after OGD/R (Fig. 2F–H). These trends were partly reversed by ginsenoside CK or sc-222227 (Fig. 2F–H).

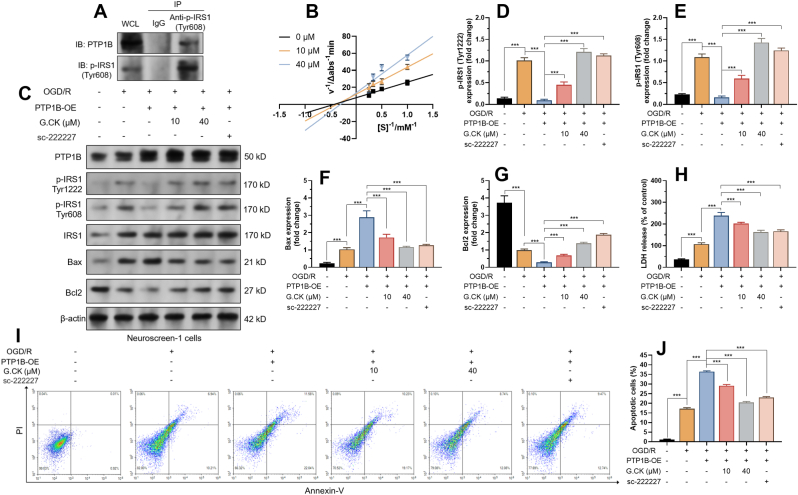

3.3. Ginsenoside CK reduces PTP1B-mediated IRS1 tyrosine dephosphorylation and neuronal apoptosis in vitro

IRS1 is a known substrate of PTP1B and has a confirmed role in PI3K-Akt signaling pathways [18,20,40]. We hypothesized that ginsenoside CK might exert regulatory effects through the PTP1B-IRS1 axis. Co-IP assay in Neuroscreen-1 cells confirmed the interaction between PTP1B and p-IRS1 (Tyr608) (Fig. 3A). Then, Lineweaver−Burk double reciprocal plots were generated to visualize the kinetic behavior of ginsenoside CK against PTP1B (Fig. 3B). 10 μM and 40 μM of ginsenoside CK lines intersected with the Y axis at higher positions than the 0 μM line, implying decreased maximum reaction rate (Vmax) of enzymatic reaction (Fig. 3B). The Michaelis constant (Km) also changed accordingly (Fig. 3B). These findings indicate that the presence of ginsenoside CK impaired the catalyzing capability of PTP1B.

Fig. 3.

Ginsenoside CK reduces PTP1B-mediated IRS1 tyrosine dephosphorylation and neuronal apoptosis in vitro. A. Co-IP was performed to show the interaction between PTP1B and p-IRS1 (Tyr608). IP was performed using anti-p-IRS1 (Tyr608). Then, the presence of PTP1B in the immunocomplex was detected by western blotting. B. Lineweaver-Burk plots for PTP1B inhibition by ginsenoside CK (10 or 40 μM). C-G. Representative image (C) and quantitation (D-G) of western blot analysis of PTP1B, p-IRS1 (Tyr1222 and Tyr608), IRS1, Bax and Bcl2 in NEUROSCREEN-1 cells with PTP1B overexpression after OGD (3h)/R (24h), with or without the presence of ginsenoside CK (10 or 40 μM) or sc-222227 (5 μM). G. LDH assay was performed to assess LDH release in NEUROSCREEN-1 cells treated as in panel A. H–I. Flow cytometric analysis was performed to quantify the ratio of apoptotic NEUROSCREEN-1 cells (annexin V+/PI-), after the indicating treatments. Quantitative results were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Neuroscreen-1 cells with or without PTP1B overexpression were subjected to OGD/R treatment. OGD/R treatment activated the expression of tyrosine phosphorylated IRS1 (Tyr1222 and Tyr608), which might be adaptive and protective responses of neural cells (Fig. 3C–E). PTP1B overexpression drastically suppressed the phosphorylation of these two tyrosines (Fig. 3C–E). Similar to sc-222227, ginsenoside CK weakened PTP1B-mediated dephosphorylation and restored p-IRS1 expression (Fig. 3C–E). In addition, under the OGD/R setting, ginsenoside CK remarkably alleviated PTP1B overexpression-induced upregulation of Bax and restored Bcl2 expression (Fig. 3C, F-G). Then, LDH release assay and flow-cytometric analysis of annexin V/PI staining were performed to assess cellular apoptosis. PTP1B overexpression exacerbated LDH release (Fig. 3H) and apoptosis after OGD/R (Fig. 3I–J). These trends were partly reversed by ginsenoside CK treatment (Fig. 3I–J).

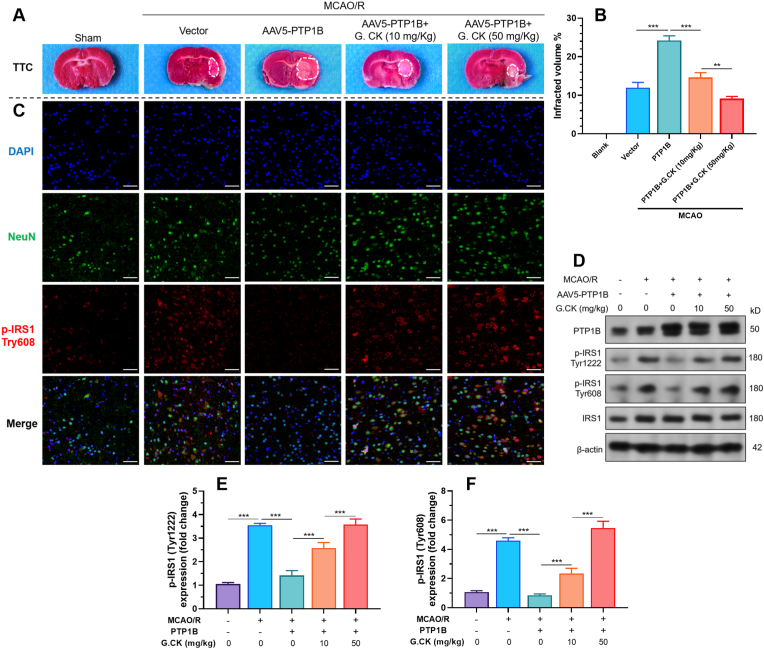

3.4. Ginsenoside CK reduces PTP1B-mediated IRS1 tyrosine dephosphorylation in vivo

MCAO models in rats were generated to check the in vivo neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside CK. MCAO/R resulted in significantly larger infarcted areas in the group with PTP1B overexpression compared to the control group (24.20% ± 1.217% vs. 11.93% ± 1.401%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A–B). Intraperitoneal injection of ginsenoside CK significantly reduced infarcted areas in a dose-dependent manner (14.60% ± 1.253% and 9.13% ± 0.59% in 10mg/kg and 50 mg/kg groups, respectively) (Fig. 4A–B). Then, immunofluorescent staining was performed to visualize the expression of p-IRS1 (tyr608) in the penumbra of the brain. MCAO/R stimulated the expression of p-IRS1 in neurons, which might be a spontaneous protective reaction (Fig. 4C). PTP1B overexpression reduced p-IRS1 (tyr608) expression. However, this suppressive effect was canceled by ginsenoside CK treatment (Fig. 4C). Western blotting assays were then performed using tissue from the ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere. PTP1B overexpression decreased the tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS1 under the MCAO/R setting (Fig. 4D–F). Intraperitoneal injection of ginsenoside CK before MCAO significantly restored IRS1 tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 4D–F).

Fig. 4.

Ginsenoside CK reduces PTP1B-mediated IRS1 tyrosine dephosphorylation in vivo. A-B. Representative images of TTC staining (A) and ipsilateral infarct area (B) at day 3 after MCAO/R. C. Representative confocal microscopic images showing the expression of NeuN (green) and p-IRS1 (tyr608) (red) in the penumbra areas in each group indicated in panel A. D-F. Representative images (D) and quantitation (E-F) of western blot analysis of p-IRS1 (tyr1222 and tyr608) in the ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere from each group indicated in panel A. Scale bar = 50 μm. Results were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

3.5. Ginsenoside CK alleviated neuronal apoptosis exacerbated by PTP1B overexpression after MCAO/R

To validate the protective effect of ginsenoside CK on neuronal death induced by MCAO/R in the penumbra, we performed TUNEL staining, Nissl staining and H&E staining. Results showed that ginsenoside CK alleviated neuronal death exacerbated by PTP1B overexpression after MCAO/R (Fig. 5A). Similar trends were observed in the expression of pro-apoptotic Bax protein (Fig. 5B–C). In terms of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein, PTP1B overexpression further decreased its expression after MCAO/R. However, ginsenoside CK treatment partly restored its expression (Fig. 5B and D).

Fig. 5.

Ginsenoside CK alleviated neuronal apoptosis exacerbated by PTP1B overexpression after MCAO/R. A. Representative images of TUNEL staining, Nissl staining and H&E staining in the penumbra on day 3 after MCAO/R. B-D. Representative images (B) and quantitation (C-D) of western blot analysis of Bax and Bcl2 in the ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere from each group in panel A. Scale bar = 100 μm. Results were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Ginsenoside CK can activate PI3K-Akt signaling and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in neurons, thereby promoting their proliferation and survival [11,41]. However, the mediators between ginsenoside CK and the activated PI3K-Akt signaling pathway remain poorly understood. In this study, we further explored its docking proteins. Molecular docking and subsequent SPR technology in the current study confirmed that ginsenoside CK interacts with PTP1B with a high affinity. The binding sites of ginsenoside CK on PTP1B include some critical residues of its substrate-binding and catalyzing sites (Y46, D181, and F182).

PTP1B has been recently identified as a promising therapeutic target in ischemic stroke [[31], [32], [33]]. Intraperitoneal administration of PTP1B post-reperfusion in mice showed a dose-dependent reduction in infarcted volumes and recovery in neurological functions [31]. In another report, neuronal PTP1B knockout mice showed substantially better recovery in sensory and motor functions after sensorimotor cortex stroke. Besides, PTP1B knockout mice had less anxiety-like and depression-like behaviors after peri-prefrontal cortex stroke [32].

Our bioinformatic analysis based on the known PTP1B-interacting proteins confirmed their involvement in PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Inhibiting PTP1B can increase Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in a mice model [31]. Therefore, we infer that PTP1B might be an important downstream effector of ginsenoside CK in modulating PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. To validate this hypothesis, we checked p-Akt and p-ERK1/2 expression in neuroscreen-1 cells after OGD/R. Results confirmed that ginsenoside CK could enhance p-Akt and p-ERK1/2 expression after OGD/R and rescue their expression suppressed by PTP1B overexpression.

Previous studies showed that PTP1B could negatively regulate Akt activation via dephosphorylating several upstream tyrosine kinases and their docking proteins, such as IRS1, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR2) [[37], [38], [39],42]. Among the interacting proteins, IRS1 has been characterized as an important player exerting neural protection against ischemia-associated injuries [13,43]. Increased IRS1 expression might be an adaptive response in rat pups following hypoxic-ischemia, which generates neuroprotection against brain damage [13,44]. Neuron-specific IRS1 transgenic rats had reduced neurovascular injuries and brain damage after hypoxic-ischemic injury [43]. Our in vitro enzyme kinetic analysis confirmed that ginsenoside CK impaired the dephosphorylation capability of PTP1B. Therefore, we hypothesized that ginsenoside CK might exert PI3K/Akt activating effects via the PTP1B-IRS1 axis. To validate this hypothesis, we conducted in vitro OGD/R studies using neuroscreen-1 cells and in vivo MCAO/R model in rats. PTP1B overexpression reduced IRS1 tyrosine phosphorylation in neuroscreen-1 cells after OGD/R and in the ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere of the rat brain after MCAO/R. When ginsenoside CK was administrated, IRS1 tyrosine phosphorylation was significantly restored. In addition, ginsenoside CK treatment attenuated neuronal apoptosis, which was exaggerated by PTP1B overexpression. These findings demonstrated that ginsenoside CK could activate PI3K/Akt signaling via inhibiting PTP1B-mediated IRS1 tyrosine dephosphorylation. However, as a natural compound with multiple docking proteins, its molecular regulatory network is complex. One recent study showed that PTP1B inhibition could alleviate ischemia/reperfusion-induced neuronal damage by reducing microglial activation [33]. These protective effects were mediated by inhibiting the PERK pathway and subsequent ER stress and autophagy [33]. Therefore, other potential molecular mechanisms underlying the neuronal protective effects of ginsenoside CK should be explored in the future.

5. Conclusion

This study revealed that ginsenoside CK binds to PTP1B with a high affinity. It inhibits PTP1B-mediated IRS1 tyrosine dephosphorylation and activates PI3K/Akt signaling. This novel mechanism helps explain the role of ginsenoside CK in activating the neuronal protective PI3K-Akt signaling pathway after ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Funding

This study was supported by the Key Research Project of the Science & Technology Department of Sichuan Province, China (2021YFS0131 and 2020YFS0414).

Authorship contributions

Fei Xu: Conception and design of study, acquisition of data, Drafting the manuscript. Suping Li: Conception and design of study, analysis and/or interpretation of data, Drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Jing Fu: acquisition of data, Drafting the manuscript. Liang Yu: acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data. Nengwei Yu: acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

All persons who have made substantial contributions to the work reported in the manuscript (e.g., technical help, writing and editing assistance, general support), but who do not meet the criteria for authorship, are named in the Acknowledgements and have given us their written permission to be named. If we have not included an Acknowledgements, then that indicates that we have not received substantial contributions from non-authors.

Footnotes

Jing Fu and Liang Yu contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Fei Xu, Email: 3578001337@qq.com.

Suping Li, Email: 359269660@qq.com.

References

- 1.Nabavi S.F., Sureda A., Habtemariam S., Nabavi S.M. Ginsenoside Rd and ischemic stroke; a short review of literature. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39(4):299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.02.002. Epub 2016/02/13 PubMed PMID: 26869821; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4593783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang B., Zhu Q., Man X., Guo L., Hao L. Ginsenoside Rd inhibits apoptosis following spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9(18):1678–1687. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.141802. Epub 2014/11/07 PubMed PMID: 25374589; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4211188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang C., Du F., Shi M., Ye R., Cheng H., Han J., et al. Ginsenoside Rd protects neurons against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity by inhibiting ca(2+) influx. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2012;32(1):121–128. doi: 10.1007/s10571-011-9742-x. Epub 2011/08/04 PubMed PMID: 21811848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang G., Xia F., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Cao Y., Wang L., et al. Ginsenoside Rd is efficacious against acute ischemic stroke by suppressing microglial proteasome-mediated inflammation. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(4):2529–2540. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9261-8. Epub 2015/06/18 PubMed PMID: 26081140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye R., Yang Q., Kong X., Han J., Zhang X., Zhang Y., et al. Ginsenoside Rd attenuates early oxidative damage and sequential inflammatory response after transient focal ischemia in rats. Neurochem Int. 2011;58(3):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.12.015. Epub 2010/12/28 PubMed PMID: 21185898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao H., Sapolsky R.M., Steinberg G.K. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt survival signal pathways are implicated in neuronal survival after stroke. Molecular Neurobiology. 2006;34(3):249–269. doi: 10.1385/MN:34:3:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin S., Jeon J.H., Lee S., Kang W.Y., Seong S.J., Yoon Y.R., et al. Detection of 13 ginsenosides (Rb1, Rb2, rc, Rd, Re, Rf, Rg1, Rg3, Rh2, F1, compound K, 20(S)-Protopanaxadiol, and 20(S)-Protopanaxatriol) in human plasma and application of the analytical method to human pharmacokinetic studies following two week-repeated administration of red ginseng extract. Molecules. 2019;24(14) doi: 10.3390/molecules24142618. Epub 2019/07/22 PubMed PMID: 31323835; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6680484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi M.K., Jin S., Jeon J.H., Kang W.Y., Seong S.J., Yoon Y.R., et al. Tolerability and pharmacokinetics of ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, and compound K after single or multiple administration of red ginseng extract in human beings. J Ginseng Res. 2020;44(2):229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.10.006. Epub 2020/03/10 PubMed PMID: 32148404; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7031742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Q., Lou T., Wang M., Xue L., Lu J., Zhang H., et al. Compound K inhibits autophagy-mediated apoptosis induced by oxygen and glucose deprivation/reperfusion via regulating AMPK-mTOR pathway in neurons. Life Sci. 2020;254 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117793. Epub 2020/05/18 PubMed PMID: 32416164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park J.S., Shin J.A., Jung J.S., Hyun J.W., Van Le T.K., Kim D.H., et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of compound K in activated microglia and its neuroprotective effect on experimental stroke in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341(1):59–67. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.189035. Epub 2011/12/31 PubMed PMID: 22207656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh J.M., Jeong J.H., Park S.Y., Chun S. Ginsenoside compound K induces adult hippocampal proliferation and survival of newly generated cells in young and elderly mice. Biomolecules. 2020;10(3) doi: 10.3390/biom10030484. Epub 2020/03/27 PubMed PMID: 32210026; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7175218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myers M.G., Jr., Sun X.J., White M.F. The IRS-1 signaling system. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19(7):289–293. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90007-8. Epub 1994/07/01 PubMed PMID: 8048169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu Y.F., Jiang S.T., Chow Y.H., Huang C.C., Ho C.J., Chou Y.P. Insulin receptor substrate-1 activation mediated p53 downregulation protects against hypoxic-ischemia in the neonatal brain. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(6):3658–3669. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9300-5. Epub 2015/06/27 PubMed PMID: 26111627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duarte A.I., Moreira P.I., Oliveira C.R. Insulin in central nervous system: more than just a peripheral hormone. J Aging Res. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/384017. Epub 2012/04/14 PubMed PMID: 22500228; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3303591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duarte A.I., Santos P., Oliveira C.R., Santos M.S., Rego A.C. Insulin neuroprotection against oxidative stress is mediated by Akt and GSK-3beta signaling pathways and changes in protein expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783(6):994–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.02.016. Epub 2008/03/20 PubMed PMID: 18348871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taniguchi C.M., Emanuelli B., Kahn C.R. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(2):85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. Epub 2006/02/24 PubMed PMID: 16493415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langlais P., Yi Z., Finlayson J., Luo M., Mapes R., De Filippis E., et al. Global IRS-1 phosphorylation analysis in insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2011;54(11):2878–2889. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2271-9. Epub 2011/08/19 PubMed PMID: 21850561; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3882165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saltiel A.R., Kahn C.R. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature. 2001;414(6865):799–806. doi: 10.1038/414799a. Epub 2001/12/14 PubMed PMID: 11742412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein B.J., Bittner-Kowalczyk A., White M.F., Harbeck M. Tyrosine dephosphorylation and deactivation of insulin receptor substrate-1 by protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Possible facilitation by the formation of a ternary complex with the Grb2 adaptor protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(6):4283–4289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4283. Epub 2000/02/08 PubMed PMID: 10660596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Rodriguez A., Mas Gutierrez J.A., Sanz-Gonzalez S., Ros M., Burks D.J., Valverde A.M. Inhibition of PTP1B restores IRS1-mediated hepatic insulin signaling in IRS2-deficient mice. Diabetes. 2010;59(3):588–599. doi: 10.2337/db09-0796. Epub 2009/12/24 PubMed PMID: 20028942; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2828646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu J., Dong J., Ding H., Wang B., Wang Y., Qiu Z., et al. Ginsenoside compound K inhibits obesity-induced insulin resistance by regulation of macrophage recruitment and polarization via activating PPARgamma. Food Funct. 2022;13(6):3561–3571. doi: 10.1039/d1fo04273d. Epub 2022/03/10 PubMed PMID: 35260867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang L., Yin X., Chen Y.H., Chen Y., Jiang W., Zheng H., et al. Proteomic analysis reveals ginsenoside Rb1 attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibiting ROS production from mitochondrial complex I. Theranostics. 2021;11(4):1703–1720. doi: 10.7150/thno.43895. Epub 2021/01/08 PubMed PMID: 33408776; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7778584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park K., Cho A.E. Using reverse docking to identify potential targets for ginsenosides. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2017;41(4):534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S., Fu J., Wang Y., Hu C., Xu F. LncRNA MIAT enhances cerebral ischaemia/reperfusion injury in rat model via interacting with EGLN2 and reduces its ubiquitin-mediated degradation. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25(21):10140–10151. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16950. Epub 2021/10/24 PubMed PMID: 34687132; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8572800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chua P., Lim W.K. Optimisation of a PC12 cell-based in vitro stroke model for screening neuroprotective agents. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8096. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87431-4. Epub 2021/04/16 PubMed PMID: 33854099; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8046774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng Y., Zhang X., Zhang T., Grace P.M., Li H., Wang Y., et al. Lovastatin inhibits Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in microglia by targeting its co-receptor myeloid differentiation protein 2 and attenuates neuropathic pain. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;82:432–444. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.09.013. Epub 2019/09/23 PubMed PMID: 31542403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao Z.J., Dong J., Che Y.J., Zhu M.F., Wen M., Wang N.N., et al. TargetNet: a web service for predicting potential drug-target interaction profiling via multi-target SAR models. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2016;30(5):413–424. doi: 10.1007/s10822-016-9915-2. Epub 2016/05/12 PubMed PMID: 27167132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y., Grimm M., Dai W.T., Hou M.C., Xiao Z.X., Cao Y., Cb-Dock A web server for cavity detection-guided protein-ligand blind docking. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41(1):138–144. doi: 10.1038/s41401-019-0228-6. Epub 2019/07/03 PubMed PMID: 31263275; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7471403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A.H., Tanaseichuk O., et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. Epub 2019/04/05 PubMed PMID: 30944313; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6447622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J., Chen B., Liang J., Han J., Zhou L., Zhao R., et al. Lanostane triterpenoids with PTP1B inhibitory and glucose-uptake stimulatory activities from mushroom fomitopsis pinicola collected in north America. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(37):10036–10049. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04460. Epub 2020/08/26 PubMed PMID: 32840371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun M., Izumi H., Shinoda Y., Fukunaga K. Neuroprotective effects of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitor on cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in mice. Brain Res. 2018;1694:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.04.029. Epub 2018/05/01 PubMed PMID: 29705606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cruz S.A., Qin Z., Ricke K.M., Stewart A.F.R., Chen H.H. Neuronal protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B hinders sensory-motor functional recovery and causes affective disorders in two different focal ischemic stroke models. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16(1):129–136. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.286970. Epub 2020/08/14 PubMed PMID: 32788467; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7818877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu Y., Yu J., Gong J., Shen J., Ye D., Cheng D., et al. PTP1B inhibitor alleviates deleterious microglial activation and neuronal injury after ischemic stroke by modulating the ER stress-autophagy axis via PERK signaling in microglia. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13(3):3405–3427. doi: 10.18632/aging.202272. Epub 2021/01/27 PubMed PMID: 33495405; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7906217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tonks N.K. PTP1B: from the sidelines to the front lines. FEBS Lett. 2003;546(1):140–148. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00603-3. Epub 2003/06/28 PubMed PMID: 12829250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma B., Xie L., Yang F., Wang W., Zhou Q., Xiang M., et al. Recent advance on PTP1B inhibitors and their biomedical applications. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2020;199 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manning B.D., Toker A. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating the network. Cell. 2017;169(3):381–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.001. Epub 2017/04/22 PubMed PMID: 28431241; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5546324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traves P.G., Pardo V., Pimentel-Santillana M., Gonzalez-Rodriguez A., Mojena M., Rico D., et al. Pivotal role of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) in the macrophage response to pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory challenge. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1125. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.90. Epub 2014/03/15 PubMed PMID: 24625984; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3973223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanno T., Tsuchiya A., Tanaka A., Nishizaki T. Combination of PKCε activation and PTP1B inhibition effectively suppresses aβ-induced GSK-3β activation and tau phosphorylation. Molecular Neurobiology. 2016;53(7):4787–4797. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feizi S. Protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP1B) regulates EGF-induced stimulation of corneal endothelial cell proliferation. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2009;4(2):127–128. Epub 2009/04/01. PubMed PMID: 23198060; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3498550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feldhammer M., Uetani N., Miranda-Saavedra D., Tremblay M.L. PTP1B: a simple enzyme for a complex world. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;48(5):430–445. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.819830. Epub 2013/07/25 PubMed PMID: 23879520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H., Qu F., Xin T., Sun W., He H., Du L. Ginsenoside compound K promotes proliferation, migration and differentiation of schwann cells via the activation of MEK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT pathways. Neurochem Res. 2021;46(6):1400–1409. doi: 10.1007/s11064-021-03279-0. Epub 2021/03/20 PubMed PMID: 33738663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanahan A.A., Lech D., Dubrac A., Zhang J., Zhuang Z.W., Eichmann A., et al. PTP1b is a physiologic regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in endothelial cells. Circulation. 2014;130(11):902–909. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009683. Epub 2014/07/02 PubMed PMID: 24982127; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6060619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tu Y.F., Jiang S.T., Chiang C.W., Chen L.C., Huang C.C. Endothelial-specific insulin receptor substrate-1 overexpression worsens neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury via mTOR-mediated tight junction disassembly. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7(1):150. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00548-3. Epub 2021/07/07 PubMed PMID: 34226528; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8257791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amtul Z., Hill D.J., Arany E.J., Cechetto D.F. Altered insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling in a comorbid rat model of ischemia and beta-amyloid toxicity. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5136. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22985-4. Epub 2018/03/25 PubMed PMID: 29572520; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5865153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]