Abstract

Introduction

Renal intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) is a rare, aggressive B-cell lymphoma with neoplastic cells occupying the vascular lumina with only 53 patients reported to date. Here, we present the largest case series to characterize this rare disease.

Methods

We performed a multi-institutional, retrospective review of kidney biopsies and autopsies with a diagnosis of kidney IVLBCL and report our findings.

Results

We identified 20 patients with an average age of 65.7 ± 7.8 years (55% males) with IVLBCL on kidney biopsy. The most common clinical presentation was fever and anemia. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was noted in 70% to 90%, proteinuria in 70% to 84.1%, hematuria in 45%, and nephrotic-range proteinuria in 10% to 26.1% of cases. The median (interquartile range) of serum creatinine was 1.75 (1.14, 3.3) mg/dl. Neoplastic lymphoid cells were present in glomeruli, peritubular capillaries, and arteries or veins. Of the patients, 44.3% showed extrarenal infiltration into bone marrow, liver, spleen, central vervous system, lung and skin. Neoplastic cells express CD20, CD79a, PAX-5, and MUM1+, and were CD10-negative. Available follow-up data showed a median survival of 21 months after diagnosis. Extrarenal involvement is a significant and independent predictor of mortality with a hazard ratio of 4.975 (95% confidence interval:1.38, 17.88) after controlling for age and gender. Serum creatinine, age, sex, and infiltration of intrarenal arteries or veins did not affect survival.

Conclusion

Kidney IVLBCL is a rare disease that is unexpectedly diagnosed by kidney biopsy, presenting with fever, anemia, mild AKI, and proteinuria. Median survival is 21 months and extrarenal involvement is associated with worse outcome.

Keywords: B-lymphocytes, intravascular, kidney lymphoma, prognosis, proteinuria

Graphical abstract

IVLBCL is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with uncommon clinical presentations. The incidence ranges from 0.5 to 1 person per million people and most cases have a poor prognosis.1 Three different variants (classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic syndrome-associated) have been described, with differences in clinical features and outcome.2 The classic form (also known as the Western variant) presents with symptoms related to the organ involved, including the central nervous system, endocrine system, lung, kidney, among others. Renal involvement is rare. The hemophagocytic variant (Asian variant) presents with bone marrow and hepatosplenic infiltration. Patients with this variant present with ‘B’ symptoms and have a poor prognosis. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis itself is a life-threatening disorder characterized by fever, cytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, hemophagocytosis, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperferritinemia, low natural killer cell activity, and elevated soluble CD25. A confirmed diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis requires at least 5 criteria to be fulfilled. Because the laboratory assay of natural killer cell activity and soluble CD25 was not easily available, most institutions considered a provisional diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis on the basis of presence of fever, cytopenia, hemophagocytosis, and hepatosplenomegaly.2 The cutaneous form presents commonly in females with median age of 59 years (compared to 72 years for the classic IVLBCL). The cutaneous manifestations are widely variable ranging from erythematous eruption, plaques, cellulitis, painful and /or ulcerated nodules, and desquamative plaques in upper and lower limbs, lower abdomen, breast, and submammary region. Reportedly, it has better prognosis than the other 2 variants.3,4

The malignant cells in renal involvement can involve glomerular capillaries, peritubular capillaries, and tubulointerstitium. The signs and symptoms are heterogenous, ranging from fever of unknown origin, AKI, or proteinuria. The nonspecific clinical presentation contributes to a delay in diagnosis.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of The University of Iowa (201707806) and Arkana Laboratories (Solutions IRB). A multi-institutional retrospective study of all native kidney biopsy and autopsy databases was performed through December 2021. Searching for “intravascular large cell lymphoma” involving kidneys, we identified 20 cases in total, including 11 kidney biopsies from Arkana Laboratories (Little Rock, AR) and 3 biopsy cases from Cedars Sinai Medical Center (Los Angeles, CA). All clinical records, biopsy reports and slides were reviewed (when available). Follow-up and treatment data were obtained from electronic medical record and/or direct discussion with the nephrology clinical team. All biopsy cases had the standard kidney pathology examinations, including light microscopic evaluation with Jones methenamine silver, periodic acid–Schiff, hematoxylin and eosin, and trichrome stains, and Congo Red staining (in many cases) to rule out amyloidosis. Immunofluorescence microscopy was done on frozen sections using antibodies against IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C1q, kappa light chain, lambda light chain fibrin or fibrinogen, and albumin. Electron microscopic examination was performed for all cases with available non-sclerosed glomeruli in electron microscopic sample. Comprehensive evaluation of atypical cells was performed in consultation with a qualified hematopathologist. Immunohistochemistry was done for several markers of hematologic malignancies, including CD3, CD5, CD20, BCL6, BCL2, etc.

Given the relative rarity of the cases, we performed literature search using “kidney” and “intravascular large cell lymphoma” and reviewed all previously reported cases. Clinical presentation, pathologic features, treatment, and follow-up or survival data were collected, whenever available, and included into our analysis. The clinical and pathologic characteristics of these cases were analyzed separately for our 20 cases and 73 cases (when data was available from 53 previously reported cases in the literature, Supplementary Table S1). The survival analysis was performed for all cases with available follow-up data.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables close to normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and compared using the two-tailed t test. Skewed continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range (25%, 75%) and tested by non-parametric tests. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test, whenever appropriate. Kaplan Meier survival curve was generated to examine the survival of IVLBCL. To elucidate factors independently associated with survival, we applied univariate Cox regression analysis for each parameter. For multivariate Cox regression analysis, we included factors with P-values < 0.1 and age. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata IC version 10 (College Station, TX).

Results

Our index case (case #10, Table 1) is presented here to demonstrate the common histopathologic features noted on renal biopsy. A 59-year-old man presenting with AKI underwent a renal biopsy, which showed hypercellular glomeruli with large, atypical cells plugging the glomerular capillaries and blood vessels. These cells had increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and many had prominent nucleoli. The background renal parenchyma also demonstrated patchy acute tubular injury, with mild to moderate chronicity, and infiltration of peritubular capillaries by atypical cells (Figure 1). The atypical infiltrate is positive for CD20, BCL6, MUM1, BCL2, and c-MYC (50%); and negative for CD10, EBER, and TdT. Background T cells are highlighted by CD3 and CD5. The blood vessels are highlighted by CD31 and CD34. Ki-67 proliferative index is above 90%. Taken together, these immunostaining profiles confirm the presence of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with nongerminal center phenotype. This patient is lost to follow-up and the treatment or survival data is not available.

Table 1.

Epidemiology and histo-morphologic characteristics of multi-institutional cohort

| Case | Age | Ethnicity | Gender | AKI | Proteinuria | HEM | Infiltrations by atypical cells |

Serum |

Death | Time |

Treatment and follow-up | Clinical or laboratory findings | Microscopic description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glomeruli | PTC | A/V | Extrarenal | Cre (mg/dl) | (mo) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 75 | Unclear | Female | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 1 | 12 | CHOP | Negative SPEP/UPEP | 0/5 glomeruli sclerosed, diffuse glomerular infiltration by neoplastic cells, moderate IFTA, severe arteriosclerosis. |

| 2 | 72 | Caucasian | Male | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | splenomegaly, diffuse rash, neuropathy, dyspnea | Diffuse glomerular and occasional PTC Infiltration by neoplastic cells, mesangiolysis, mild to moderate IFTA, acute tubular injury, moderate arteriosclerosis and mild arteriolosclerosis. |

||||

| 3 | 77 | AA | Female | Yes | No | No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | right lung base infiltration by CT suspicious for malignancy | 3/5 glomeruli globally sclerosed, 1 glomerulus and extensive PTC infiltration by neoplastic cells, tubular injury, severe I FTA. |

|||

| 4 | 57 | AA | Female | Yes | Nephrotic | No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 | 1 | 24 | hospice, deceased 24 months later | Negative for ANA, RF, dsDNA, ANCAs, Hepatitis B and C markers, SPEP/UPEP | |

| 5 | 66 | Unclear | Female | Yes | No | No | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Elevated ACE, negative ANCA and ANA | Diffuse cortical infiltration by neoplastic cells. | ||||

| 6 | 52 | Caucasian | Male | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | 0 | 9 | Had chemotherapy (unknown regimen), improved kidney function with normal Cr, lost following up 9 months later | Negative for Hepatitis B/C markers, HIV, and RPR | 16 nonsclerosed glomeruli, diffuse PTC and occasional glomerular infiltration by neoplastic cells, mild to moderate IFTA, acute tubular injury. |

| 7 | 60 | Unclear | Male | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2.73 | 1 | Had chemotherapy (unknown regimen), deceased (unknown interval) | A. Fibrillation, DVT, celiac sprue, hypothyroidism, syncopal episode with BP 70/50 | 2/23 glomeruli sclerosed, rare neoplastic cell infiltration, mild IFTA, acute tubular injury, moderate arteriosclerosis. |

|

| 8 | 74 | Caucasian | Female | Yes | No | No | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 | 24 | R-CHOP, renal function normalized (Cr down to 0.9) at 24 mo | Dyspnea, weakness, fatigue, and edema. Labs: possibly adrenal insufficiency and hemolytic anemia | 2/15 glomeruli sclerosed, extensive PTC infiltration by neoplastic cells. |

| 9 | 64 | Caucasian | Male | No | No | No | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No glomerulosclerosis, PTC infiltration by neoplastic cells, mild IFTA. | ||||

| 10 | 59 | Asian | Male | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4.4 | Positive ANA, low C3 and C4. | Diffuse glomerular neoplastic cell infiltration. Mild to moderate IFTA, moderate arteriosclerosis. | |||

| 11 | 64 | Unclear | Male | No | No | No | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 12 | 59 | Asian | Male | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4.4 | low c3 | ||||

| 13 | 72 | Native American | Male | Yes | Nephrotic | Yes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 1 | 2 | Died 2 months after diagnosis | anemia | Diffuse and global glomerular infiltration by neoplastic cells. | |

| 14 | 53 | Unclear | Male | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 1 | 3 | Died 3 months after diagnosis | Diffuse and global glomerular infiltration by neoplastic cells. | ||

| 15 | 57 | Caucasian | Female | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | Treated with last Serum Creatinine of 1.7 mg/dL and minimal proteinuria. | palpable purpura | 75% global glomerulosclerosis, glomerular TMA, glomerular and PTC infiltration by neoplastic cells. | ||

| 16 | 69 | Caucasian | Female | Yes | No | Yes | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 60 | Alive 5 years post diagnosis, unclear treatment | Monoclonal Gammopathy, positive ANA | Focal glomerular and prominent PTC infiltration by neoplastic cells | ||

| 17 | 70 | Unclear | Female | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1.6 | 1 | Deceased (time unknown) | Focal glomerular and extensive PTC infiltration by neoplastic cells | |||

| 18 | 74 | Caucasian | Female | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | 1 | Comfort care, died less than 1 month after diag. | hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated LDH, hyperbilirubinemia, low complements, hypertension, fibromyalgia, GERD, negative bone marrow biopsy | 3/36 glomeruli sclerosed, diffuse glomerular and PTC infiltration by neoplastic cells, mild IFTA, acute tubular injury. |

| 19 | 73 | AA | Female | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4.1 | hemolytic anemia (LDH >2000, anemia, thrombocytopenia), negative bone marrow biopsy | 2/26 glomeruli sclerosed, glomerular infiltration by neoplastic cells, concurrent AA amyloid, minimal IFTA, acute tubular injury. | |||

| 20 | 67 | Asian | Female | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 1 | R-CHOP (4 cycles), Clinical response 1 month after diag. | lupus with decline in renal function | 9 non-sclerosed glomeruli, all with neoplastic cell infiltration, mild IFTA, mild arteriosclerosis. |

AA, African American; A/V, arterial/venous; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, oncovin/vincristine and prednisolone; HEM, hematuria; IFTA, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy; PTC, peritubular capillary; R-CHOP, rituximab combined with CHOP; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; 0, No; 1, Yes.

Figure 1.

Light microscopy (case #10) reveals glomeruli with mesangial and endocapillary hypercellularity because of infiltration by atypical large cells (arrows, 200×, hematoxylin and eosin stain), which also infiltrate peritubular capillaries. The atypical cells are positive for CD20 (200×), BCL2 (200×), and c-MYC (200×). Ki-67 highlights an increased (>90%) proliferation index (200×).

The detail characteristics of 20 patients from 3 institutions is described in Table 1. Additional clinical and pathologic features of 20 IVLBCL case series from 3 institutions and the overall features in 73 IVLBCL cases, including additional 53 reported cases from the literature review are reported in Supplementary Table S1.5 The average age of the current case series was 65.7 ± 7.8 years and 55% are males. Including all 73 patients, the mean age was 61.5 ± 11.4 (48% males). The ethnicity data was available in 33 patients, including 45.5% Asian, 24.2% Caucasian, 18.2% African American, 9.1% Hispanic, and 3% Native American. Most of the patients had fever and variable degrees of anemia. The most common renal manifestations (Table 2) were AKI, noted in 90% of our case series and 70% for all cases; proteinuria, reported in 70% of our cases and 84.1% for all cases; and hematuria, found in 45% of our case series and not mentioned or unclear in most of the reported cases. Nephrotic-range proteinuria was reported in 10% of our case series and 26.1% of all cases. Of all 43 patients with available data, the median and interquartile range of serum creatinine was 2.57 (1.6, 4.3) mg/dl in our case series and 1.7 (1.14, 3.3) mg/dl in the cases from literature review.

Table 2.

Overview of demography, renal manifestations, and pathologic findings

| Demography | Three centers N = 20 |

All cases N = 73 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.7±7.8 | 61.5±11.4 |

| Males | 55% | 48% |

| Ethnicity | Caucasians 7 (35%) | Caucasians 24.2% |

| Asians 3 (30%) | Asians 45.5% | |

| African American 3 (30%) | African American 18.2% | |

| Native American 1 (5%) | Hispanic 9.1% | |

| Unclear 6 (30%) | Native American 3.1% | |

| Renal manifestations | ||

| Clinical diagnosis of AKI | 90% | 70% |

| Proteinuria | 70% | 84% |

| Nephrotic range | 10% | 26% |

| Hematuria | 45% | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 2.57 (1.6, 4.3) | 1.7 (1.14, 3.3) |

| Pathologic findings | ||

| Glomerular capillary infiltration | 80% | 85.3% |

| Peritubular capillary infiltration | 75% | 58.6% |

| Arteries/veins | 15% | 14.1% |

| Extrarenal involvement | 35.7% | 44.3% |

AKI, acute kidney injury.

The glomerular infiltration by neoplastic lymphoid cells was identified in 80% of our case series and is comparable to the numbers (85.3% of all cases) reported in the literature. (Supplementary Table S1). The neoplastic cells are large with increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and prominent nucleoli, which may be multiple. Within the tubulointerstitium, neoplastic lymphoid cells were present in 75% of our cases and reported in 58.6% of all cases. These infiltrates were mostly within the peritubular capillaries and identified in the interstitium. Infiltration of arteries or veins by neoplastic lymphoid cells were documented in 14% to 15% of cases. The vascular spaces, do not only function as a conduit for the neoplastic cells, but are also sites for active replication, as noted by presence of mitotic figures and a high proliferative index by Ki-67 (over 90% in our index case). The spectrum of glomerular involvement (Figure 2) may range from minimal mesangial hypercellularity (Figure 2a), segmental infiltration (Figure 2b), peritubular capillaries (Figure 2b) to global glomerular infiltration by the neoplastic cells (Figure 2d). While immunofluorescence studies showed mostly negative or nonspecific staining for immunoglobulins or complements, we have observed IgM staining in the B-cells within glomerular capillaries and peritubular capillaries in the index case (Figure 2e). Ultrastructural evaluation was performed in 13 cases with available EM samples. One case with concurrent AA Amyloidosis (case #19) showed extensive podocyte foot process effacement (Figure 2f). Most of the remaining cases showed mild to moderate and segmental podocyte foot process effacement (<80%). Images from case #16 (Figure 3, Table 1) also show near complete obliteration of glomerular capillary lumina by neoplastic cells (Figure 3a). There is extensive podocyte injury noted on EM image with podocyte foot process effacement in association with numerous intraluminal neoplastic cell nuclear profiles (Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

Light microscopy (case #2) with neoplastic cells infiltration in glomeruli with minimal mesangial hypercellularity (a, 400×, PAS), segmental endocapillary hypercellularity (b, 400×, PAS), peritubular capillary involvement (c, 200×, hematoxylin and eosin) and inset-CD20 highlighting neoplastic B-cells, global glomerular infiltration (d, 400×, PAS), IgM immunofluorescence staining in glomerular and peritubular capillaries (e, 200×), EM image showing podocyte foot process effacement in capillaries infiltrated by neoplastic cells (f); Scale bar 20 μm. PAS, periodic acid–Schiff.

Figure 3.

Light microscopy showing global glomerular involvement by neoplastic cells (a, PAS stain) and EM image highlighting extensive podocyte foot process effacement in a capillary loop occluded by large neoplastic cells (b). Scale bar 20 μm. PAS, periodic acid–Schiff.

Of 61 cases which had comprehensive pathology documentation, 44.3% demonstrated evidence of extrarenal involvement, including bone marrow involvement (stage IV of lymphoma). Other sites of involvement included hepatic and splenic infiltrations; central nervous system involvement, manifesting as neurologic symptoms; lung; and skin infiltration (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

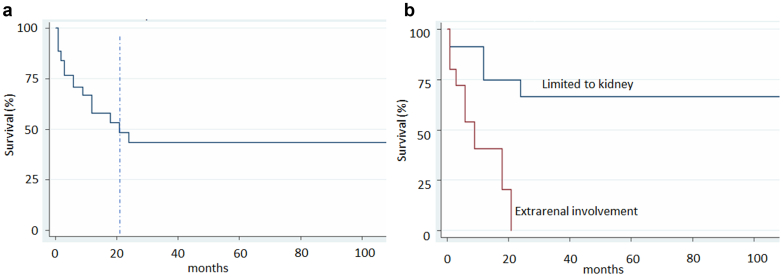

The follow-up data was available for 48 patients. Survival analysis (Figure 4) shows a median survival of approximately 21 months after diagnosis (Figure 4a). Six of 48 (12.5%) were post-mortem diagnoses without prior lymphoma diagnosis (designated as mortality at time zero in relation to the diagnosis of kidney IVLBCL). To examine prognostic features predicting survival, we performed univariate Cox regression analyses and found that worse prognosis was associated with the male gender (P = 0.059) and the presence of extrarenal involvement (P = 0.003, Table 3). Age, the levels of serum creatinine, and the intrarenal vascular infiltration did not affect survival. After controlling for gender and age, a multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that extrarenal involvement (Figure 4b). is a significant and independent predictor of mortality, with hazard ratio of 4.975 (P = 0.014).

Figure 4.

Kaplan Meier survival curve (a) Overall survival after diagnosis showed median survival of 21 months, (b) Patients with extra-renal involvement had much worse survival than those without, P < 0.001 by log rank P-test.

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis

| Univariate parameters | Hazard ratio | Standard error | z score | P > z | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum creatinine | 1.004 | 0.314 | 0.010 | 0.989 | 0.544–1.854 |

| Age | 1.027 | 0.021 | 1.290 | 0.196 | 0.986–1.070 |

| Male gender | 2.475 | 1.186 | 1.890 | 0.059 | 0.967–6.333 |

| Extrarenal | 6.227 | 3.898 | 2.920 | 0.003 | 1.826–21.238 |

| Arteries/veins | 1.781 | 1.353 | 0.760 | 0.447 | 0.402–7.894 |

| Multivariate parameters | Hazard ratio | Standard error | z score | P > z | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrarenal | 4.975 | 3.247 | 2.460 | 0.014 | 1.384–17.882 |

| Male gender | 1.405 | 0.858 | 0.560 | 0.577 | 0.424–4.653 |

| Age | 1.029 | 0.028 | 1.070 | 0.285 | 0.976–1.086 |

Discussion

Kidney IVLBCL is a rare disease presented with fever, anemia, mild AKI, and proteinuria. The highest incidence is amongst Asian population, followed by Caucasians and African Americans. The disease has a median survival of 21 months and extrarenal involvement, indicating extensive disease, is a significant predictor of worse outcome. An important consideration is the high rate of central nervous system involvement at initial presentation, which may present as recurrent or unexplained neurologic phenomena and determine survival.6,7

Patients with tubulointerstitial type of the disease usually present with bilaterally enlarged kidneys. Most common presentation is AKI with rising serum creatinine (1.7 mg/dl with interquartile range [1.14, 3.3] mg/dl in our analysis). The majority (70%−85%) have proteinuria (nephrotic-range in ∼25%). One potential mechanisms of AKI in IVLBCL is through obstruction of glomerular capillary tuft because of invasion of the lymphoma cells. As noted in our cases and other studies, the neoplastic lymphocytes have a predilection for vascular spaces and may grow in a cohesive (filling the entire vascular space), discohesive (free floating), or marginating (adhering to the vascular endothelium) pattern.8 The clinical significance of different growth patterns in the kidney is unclear given the rarity of disease. Interestingly, peripheral blood involvement is rare and reported at 4% across all variants of IVLBCL.3 Although the exact pathogenesis of nephrotic syndrome observed during IVLBCL is not known, our finding of extensive podocytopathy in glomerular capillaries obliterated by lymphoma cells (Figure 2f and 3b) suggests that podocyte injury is one possible mechanism leading to nephrotic-range proteinuria.

Common recurring abnormalities reported, including aberrations of chromosome 1 (71%), deletions of 6q (71%), rearrangements of 8p (46%), deletions of chromosome 18 (p or q arm, 32%), extra copies of chromosome 18 (29%), and involvement of MLL (11q23) may play a part in its pathogenesis.9 Ponzoni et al.10 have proposed that these cells lack surface adhesion molecules such as CD29 (β1 integrin subunit), which are required for cell adhesion and transmigration across vascular endothelium.11 The neoplastic B-lymphocytes also express CXCR3 and CXCR4 chemokine receptors involved in lymphocyte trafficking, but the endothelial cells lack corresponding ligands, allowing for congruent spread.12

The differential diagnosis of IVLBCL includes other B-cell lymphomas (CLL, mantle cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma or Burkitt lymphoma) and rarely T-cell lymphomas. If there is suspicion of involvement of kidney by a lymphoid malignancy, comprehensive morphologic evaluation and appropriate immunohistochemical studies, which include cell markers to distinguish B and T-cell lineages, malignancy, and proliferation indices, are recommended. The pathologic features of exclusive involvement of vascular channels by atypical neoplastic cells give a clue to the diagnosis of this entity, in the appropriate clinical context. Immunohistochemistry is often required for confirmatory diagnosis. The outcome of IVLBCL depends on rapid diagnosis, extrarenal involvement, and administration of early chemotherapy. The commonly used regimen for IVLBCL includes CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, oncovin/vincristine and prednisolone). The addition of rituximab to CHOP (R-CHOP) has yielded an 88% complete remission rate, 91% overall response rate, and a 3-year overall survival in 81% of patients with IVLBCL involving any organs.13 Autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation after high dose chemotherapy has been shown to improve the outcome of IVLBCL patients with 4-year overall survival of 70% to 80%.14 Chemotherapy treatment has been reported to result in clearance of the neoplastic cells from glomerular capillaries and favorable survival profile in a few cases of kidney IVLBCL.15,16 Nevertheless, the best therapeutic approach for IVLBCL is difficult to define, because of the absence of prospective clinical trials, because of the rarity of this disease. The current available data is limited to individual case reports (as in kidney IVLBCL) and underpowered studies (for all IVLBCL involving any organs).17, 18, 19 In addition, it is difficult to collect treatment data retrospectively because patients are often managed at other institutions.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the largest retrospective review of clinical and pathologic findings and prognostic factors of renal intravascular B-cell lymphoma. Limitations of this study include missing clinical and/or laboratory data in some cases, particularly those reported in the literature. In addition, treatment heterogeneity also influenced survival analysis, because the treatments ranged from none (hospice care), CHOP, rituximab, and the combination of R-CHOP. Given the variable presentation and often an unexpected diagnosis in renal biopsy, this collaborative study seeks to characterize a larger updated case series of IVBCL, identifying the common clinical, morphologic, and prognostic features, which will provide valuable information for clinicians and pathologists encountering this rare disease.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

All authors have no competing interests.

Funding

NIH DK133118 and HL145138 (DFD).

Footnotes

Table S1. Cases and respective references.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Cases and respective references.

References

- 1.Zuckerman D., Seliem R., Hochberg E. Intravascular lymphoma: the oncologist’s “great imitator”. Oncologist. 2006;11:496–502. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-5-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murase T., Nakamura S., Kawauchi K., et al. An Asian variant of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: clinical, pathological and cytogenetic approaches to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:826–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong Y.C., Kao H.W., Chuang W.Y., et al. Intravascular Large B-cell lymphoma: a case series and review of literatures. Biomed J. 2021;44:479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreri A.J., Campo E., Seymour J.F., et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant’. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desclaux A., Lazaro E., Pinaquy J.B., et al. Renal intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2017;56:827–833. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.6406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimada K., Murase T., Matsue K., et al. Central nervous system involvement in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of 109 patients. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1480–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimada K., Kiyoi H. Current progress and future perspectives of research on intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:3953–3961. doi: 10.1111/cas.15091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponzoni M., Campo E., Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks. Blood. 2018;132:1561–1567. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deisch J., Fuda F.B., Chen W., et al. Segmental tandem triplication of the MLL gene in an intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with multisystem involvement: a comprehensive morphologic, immunophenotypic, cytogenetic, and molecular cytogenetic antemortem study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1477–1482. doi: 10.5858/133.9.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponzoni M., Arrigoni G., Gould V.E., et al. Lack of CD 29 (beta1 integrin) and CD 54 (ICAM-1) adhesion molecules in intravascular lymphomatosis. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:220–226. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferry J.A., Harris N.L., Picker L.J., et al. Intravascular lymphomatosis (malignant angioendotheliomatosis). A B-cell neoplasm expressing surface homing receptors. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:444–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato M., Ohshima K., Mizuno M., et al. Analysis of CXCL9 and CXCR3 expression in a case of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:888–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreri A.J., Dognini G.P., Bairey O., et al. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meissner J., Finel H., Dietrich S., et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation experience. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:650–652. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrano A.G., Elsner B., Cabral Lorenzo M.C., Morales Clavijo F.A. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma and renal clear cell carcinoma as collision tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2021;29:653–657. doi: 10.1177/1066896920981633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hakroush S., Lehnig L.Y., Wallbach M., et al. Renal involvement of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a challenging diagnosis. J Nephrol. 2022;35:1295–1297. doi: 10.1007/s40620-021-01109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pothen L., Aydin S., Camboni A., Hainaut P. Nephrotic syndrome without kidney injury revealing intravascular large B cell lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-229359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponzoni M., Campo E., Ferreri A.J. Intravascular lymphoma occurring in patients with other non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010;8:641–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brett F.M., Chen D., Loftus T., et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma presenting clinically as rapidly progressive dementia. Ir J Med Sci. 2018;187:319–322. doi: 10.1007/s11845-017-1653-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.