Abstract

The crucial constraint in the broiler production sector is feed efficiency; many feed additives have been widely employed to increase broiler growth. Nonetheless, some of these substances exacerbate health and animal-based food product safety concerns. This meta-analysis examines the effect of clay minerals on alkaline phosphatase (ALP), broiler health, and performance. Metadata was constructed from 369 data items that were harvested from 86 studies. The addition of clay minerals was set as a fixed effect and the difference between experiments was established as a random effect. The metadata were fitted using a linear mixed model. Due to the presence of clay minerals, growth performance as assessed by body weight (BW), average daily gain (ADG), and performance efficiency index (PEI) increased significantly (P < 0.01). In the total period, the increases of BW, ADG, and PEI were 4.12 g, 0.0714 g/d, and 0.648, respectively, per unit of clay minerals added. Clay minerals did not affect blood serum parameters (e.g., ALP and calcium). The IgA and IgM concentrations in the jejunum and ileum were significantly greater (P < 0.01) in the starter phase. Among clay minerals, broilers fed diets with aluminosilicate, halloysite, kaolin, and zeolite consistently exhibited higher (P < 0.05) BW, ADG, PEI, and lower feed conversion ratio (P < 0.05) in the finisher phase. Aluminosilicate was the only clay that increased (P < 0.05) secretory IgA concentration in both jejunum and ileum. In conclusion, clay minerals could be used as a growth promoter, especially during the finisher phase, without adversely affecting feed intake, liver function, and mineral metabolism in broiler chickens. Aluminosilicate was superior in improving the mucosal immunity status of broiler chickens.

Key words: broiler chickens, clay mineral, growth promoters, meta-analysis, zeolite

INTRODUCTION

The digestive tract ecosystem is crucial for the health of broilers. The composition of intestinal microbiota and environmental parameters of the gastrointestinal tract is closely associated with the intestinal health of broilers. Compared to other avians, broilers have a small digestive system and a high flow rate, resulting in limited bacterial growth and shedding (Pan and Yu, 2014). Based on the most recent scientific studies, gut bacteria improve feed digestion, and their population stability affects the host immune system (Wu et al., 2013a; Yalçın et al., 2017). This mechanism will have a quantifiable effect on feed efficiency.

Recent feed additive technologies, such as antibiotic growth promoters (Maria Cardinal et al., 2019; Cardinal et al., 2020), antimicrobial peptides (Sholikin et al., 2021a), bacteriophages, clay and clay minerals (Slamova et al., 2011), enzymes (Kriseldi et al., 2021; Sjofjan et al., 2021), hyperimmune, phytobiotics, prebiotics, probiotics, and organic acids (Woong Kim et al., 2014), have been widely used to improve the digestive tract ecosystem and subsequently support broiler growth (Gadde et al., 2017). These features include inhibiting pathogenic bacteria (Broom, 2018), improving the digestibility of particular feed ingredients (Cao et al., 2007; Dersjant‐Li et al., 2015), enhancing nonspecific immunity in the gastrointestinal mucosa (Chen et al., 2016b), binding toxic substances in feed (Xu et al., 2018), and regulating the acidity level (Woong Kim et al., 2014). Nevertheless, most of the mentioned compounds still have limitations, particularly food safety. For instance, hyperimmune may result in autoimmunity or conflicting interactions with the host immunity (Gadde et al., 2017). Other substances, such as antimicrobial peptides, may induce allergies and pathogen resistance (Sholikin et al., 2021b). Both clay and clay minerals have inert properties and are rapidly removed from the host body; thus, it is potentially determined as the best candidate as a safe growth enhancer for broilers (Slamova et al., 2011; Gadde et al., 2017).

Clays and clay minerals have been investigated for their potential as growth promoters in the broiler (Rodríguez-Rojas et al., 2015). Clay is a material that occurs naturally in microscopic grains less than 2 or 4 micrometers in size, is composed of phyllosilicates, is malleable, and hardens upon drying (Nadziakiewicza et al., 2019). Clay minerals may be non-phyllosilicate, flexible, and thermally brittle. They are available as natural or synthetic (Rodríguez-Rojas et al., 2015; Moosavi, 2017). Clay minerals consist of one tetrahedral sheet (T) and one octahedral sheet (O). The T and O sheets are appropriately aligned in a straight line (Thiebault, 2020). Clay and clay minerals are often found in nature as a single unit, despite their different names and features. In addition, these substances possess an adsorbent capacity for many toxic molecules (Prabhu and Prabhu, 2018; Thiebault, 2020). It has been demonstrated that clay and clay minerals have a high affinity for adsorbing aflatoxins, enterotoxins, heavy metals, mycotoxins, pathogenic microorganisms, and plant metabolites (Gadde et al., 2017; Nadziakiewicza et al., 2019). Recent research indicates that clay minerals possess antibacterial and immunomodulatory properties (Durán et al., 2016; Dunislawska et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2022). They are often used as feed additives in the form of aluminosilicate, bentonite, diatomaceous earth or diatomite, glauconite, halloysite, kaolin, palygorskite or attapulgite, perlite, sepiolite, and zeolite (Gadde et al., 2017; Nadziakiewicza et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2022).

At 33 to 42 d of age, administering 10 g/kg of halloysite increased ADG and FCR in the finisher phase of broiler chickens (Nadziakiewicz et al., 2021). Halloysite substantially increased carcass weight and lowered liver and gizzard relative weights (Nadziakiewicz et al., 2022). In addition, zeolite is a popular type of clay that is advantageous to increase the expression of cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-6, and IL-10 (Gall-David et al., 2017; Qu et al., 2019; Dunislawska et al., 2022). Palygorskite enhances performance, gut defense systems, and immunity at 1 g/kg (Zha et al., 2022). Moreover, modified aluminosilicate (hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate) is also a promising adsorbent for the detoxification of Trichothecenes (T-2) toxins (Wei et al., 2019). These findings justify the promising growth-promoting effects of many clay minerals suited to be applied as a feed additive for broiler chickens. However, other research failed to establish a significant effect of clay minerals on broiler growth performance (Wu et al., 2013b, c). Discrepancies among empirical studies can potentially lead to subjective bias and nonrobust conclusions. A quantitative and objective analytical methodology is necessary to generate a more robust conclusion about clay minerals as growth enhancers supported by statistical evidence (Sadarman et al., 2021; Adli et al., 2022). Meta-analysis establishes the primary or general summary and validates a treatment effectiveness (Wahyono et al., 2022). This meta-analysis attempts to summarize and predict the optimal dosage of clay minerals in addition to optimizing on broiler growth by looking at the health parameters (such as immunoglobulins and cytokines), liver function via alkaline phosphatase concentration, and growth performance (especially daily body weight gain and feed conversion).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Ethics Declaration

This meta-analysis utilizes secondary data from published studies without necessarily needing ethical justification for animal use. However, we provide information about the ethics of animal experiments from each article cited source (Table 1).

Table 1.

Literature used in this meta-analysis data.

| No. | Article | Level1 | Region | Ethic | Clay mineral | Breed | Sex | Age2 | Weight3 | Reared4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Abaş et al. (2011) | 0–20 | Turkey | Zeolite | Ross 308 | 1 | 47 | 42 | ||

| 2. | Abbasi Pour et al. (2021) | 0–15 | Iran | yes | Sodium Bentonite | Ross | 11 | 14 | ||

| 3. | Al-Nass et al. (2011) | 0–20 | Kuwait | Zeolite | Indian River | 1 | 40 | 35 | ||

| 4. | Alharthi et al. (2022) | 0–4 | Saudi Arabia | yes | Bentonite and Zeolite | Ross 308 | 11 | 30 | ||

| 5. | Almeida et al. (2014) | 0–30 | United States | yes | Zeolite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 41.6 | 20 |

| 6. | Alzueta et al. (2002) | 0–20 | Spain | Sepiolite | Cobb | Male | 1 | 39 | 29 | |

| 7. | Attar et al. (2019) | 0–15 | Iran | yes | Sodium Bentonite | Ross 308 | Male | 11 | 24 | |

| 8. | Azar et al. (2011) | 0–50 | Iran | Perlite | Ross 308 | 1 | 42 | |||

| 9. | Bailey et al. (2006) | 0–5 | United States | yes | Bentonite | Cobb | Male | 1 | 35.4 | 42 |

| 10. | Banaszak et al. (2022) | 0–20 | Poland | yes | Mixed of halloysite and zeolite | Ross 308 | 1 | 43.5 | 7 | |

| 11. | Bolandi et al. (2021) | 0–10 | Iran | yes | Zeolite | Cobb | Proper Mix | 1 | 42 | |

| 12. | Bouderoua et al. (2016) | 0–50 | Algeria | yes | Sodium Bentonite | Hubbard | Male | 12 | 450 | 31 |

| 13. | Cabuk et al. (2004) | 0–25 | Turkey | Zeolite | Mix | 1 | 40 | 42 | ||

| 14. | Cheng et al. (2016) | 0–20 | China | yes | Palygorskite5 | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 40 | 42 |

| 15. | Cheng et al. (2018) | 0–10 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 40.1 | 42 |

| 16. | Curtui, (2000) | 0–5 | Romania | Zeolite | 1 | 28 | ||||

| 17. | Gall-David et al. (2017) | 0–0.006 | France | yes | Zeolite | Ross Pm3 | Male | 1 | 21 | |

| 18. | Grądzki et al. (2020) | 0–30 | Poland | yes | Zeolite | Ross 308 | male | 1 | 42 | |

| 19. | Denli et al. (2009) | 0–5 | Italy | yes | Diatomaceous Earth | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 47 | 42 |

| 20. | Dos Anjos et al. (2015) | 0–7.5 | United States | yes | Diatomaceous Earth | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 41 | 21 |

| 21. | Du et al. (2019) | 0–10 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 47.5 | 42 |

| 22. | Dunislawska et al. (2022) | 0–5 | Poland | yes | Zeolite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 46.6 | 42 |

| 23. | Durna Aydin et al. (2020) | 0–20 | Turkey | yes | Glauconite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 41.3 | 35 |

| 24. | El-Husseiny et al. (2008) | 0–5 | Egypt | Diatomaceous Earth | Ross 308 | Proper Mix | 1 | 39.2 | 35 | |

| 25. | Ghazalah et al. (2021) | 0–5 | Egypt | yes | Bentonite | Arbor Acres | Male | 1 | 35 | |

| 26. | Hu et al. (2013) | 0–0.6 | China | yes | Bentonite | Arbor Acres | Male | 1 | 21 | |

| 27. | Indresh et al. (2013) | 0–10 | India | Bentonite | Vencobb | Proper Mix | 1 | 35 | ||

| 28. | Joo et al. (2007) | 0–3 | Korea | Bentonite | Ross 208 | 1 | 42 | 35 | ||

| 29. | Juzaitis-Boelter et al. (2021) | 0–5 | United States | yes | Hydrated Sodium Calcium Aluminosilicate | Cobb | Male | 1 | 43 | 21 |

| 30. | Karamanlis et al. (2008) | 0–20 | Greece | Zeolite | Cobb 500 | 1 | 39.7 | 42 | ||

| 31. | Kavan et al. (2013) | 0–30 | Iran | Zeolite | Ross 308 | Male | 21 | 42 | ||

| 32. | Khanedar et al. (2012) | 0–15 | Iran | Calcium Bentonite and Sodium Bentonite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 42 | ||

| 33. | Lemos et al. (2015) | 0–15 | Brazil | Kaolin | 15 | 52 | ||||

| 34. | Lim et al. (2017) | 0–2 | Korea | Silicate | Cobb | 1 | 35 | |||

| 35. | Macháček et al. (2010) | 0–40 | Czech | yes | Zeolite | Bovan | 1 | |||

| 36. | Mallek et al. (2012) | 0–10 | Tunis | yes | Zeolite | Hubbard | Male | 1 | 45 | |

| 37. | Miazzo et al. (2005) | 0–3 | Argentina | Sodium Bentonite | Ross | Male | 23 | 50 | ||

| 38. | Miles and Henry, (2007a) | 0–20 | United States | Hydrated Sodium Calcium Aluminosilicate | Ross | Male | 1 | 21 | ||

| 39. | Miles and Henry, (2007b) | 0–20 | United States | Hydrated Sodium Calcium Aluminosilicate | Ross | Male | 1 | 21 | ||

| 40. | Modirsanei et al. (2008) | 0–30 | Iran | yes | Diatomaceous Earth | male | 1 | 42.0 | 42 | |

| 41. | Nadziakiewicz et al. (2021) | 0–10 | Poland | yes | Halloysite | Ross 308 | Proper Mix | 1 | 45 | 42 |

| 42. | Nadziakiewicz et al. (2022) | 0–10 | Poland | yes | Halloysite | Ross 308 | Proper Mix | 1 | 45 | 43 |

| 43. | Neeff et al. (2013) | 0–5 | United States | Hydrated Sodium Calcium Aluminosilicate | Ross 708 | male | 1 | |||

| 44. | Nikolakakis et al. (2013) | 0–30 | Greece | Zeolite | Cobb 500 | 1 | 42 | |||

| 45. | Oguz and Kurtoglu, (2000) | 0–25 | Turkey | Zeolite | Avian | 1 | 21 | |||

| 46. | Ortatatli and Oğuz, (2001) | 0–25 | Turkey | Zeolite | Avian | Mix | 1 | 21 | ||

| 47. | Ouachem and Kaboul, (2012) | 0–30 | Algeria | Marl | Isa 15 | 1 | 56 | |||

| 48. | Ouhida et al. (2000) | 0–20 | Spain | yes | Sepiolite | Male | 1 | 22 | ||

| 49. | Owen et al. (2012) | 0–30 | Nigeria | Kaolin | Hubbard | Mix | 1 | 60 | 56 | |

| 50. | Pappas et al. (2010) | 0–10 | Greece | yes | Palygorskite | Cobb | Proper Mix | 1 | 45 | 42 |

| 51. | Pappas et al. (2014) | 0–10 | Greece | yes | Bentonite | Ross 308 | 1 | 46 | 42 | |

| 52. | Pappas et al. (2016) | 0–10 | Greece | yes | Bentonite | Ross 308 | 1 | 45 | 42 | |

| 53. | Prvulović et al. (2008) | 0–5 | Serbia | Aluminosilicate | Mix | 1 | 42 | |||

| 54. | Qu et al. (2019) | 0–10 | China | yes | Zeolite | Arbor Acres | Male | 1 | 42 | |

| 55. | Rana et al. (2017) | 0–10 | Tunis | Zeolite | Hubbard | 1 | 37.6 | 39 | ||

| 56. | Saçakli et al. (2015) | 0–20 | Turkey | yes | Zeolite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 42.6 | 42 |

| 57. | Safaeikatouli et al. (2010) | 0–30 | Iran | Kaolin and Zeolite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 42 | ||

| 58. | Safaeikatouli et al. (2012) | 0–30 | Iran | Bentonite, Kaolin, and Zeolite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 42 | ||

| 59. | Shannon et al. (2017) | 0–5 | United States | yes | Bentonite | 1 | 37.4 | 21 | ||

| 60. | Shi et al. (2009) | 0–3 | China | Bentonite | Avian | Proper Mix | 1 | 42 | ||

| 61. | Suchý et al. (2006) | 0–20 | Czech | Zeolite | Ross 308 | Proper Mix | 1 | 43 | 40 | |

| 62. | Tang et al. (2014) | 0–4 | China | yes | Zeolite | Arbor Acres | 1 | 42 | ||

| 63. | Tang et al. (2015) | 0–4.8 | China | yes | Zeolite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 40 | 21 |

| 64. | Uzunoğlu and Yalçin, (2019) | 0–1.5 and 0–15 | Turkey | yes | Bentonite and Sepiolite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 44.1 and 43.9 | 42 |

| 65. | Wawrzyniak et al. (2017a) | 0–30 | Poland | yes | Zeolite | Ross 308 | 1 | 42 | 40 | |

| 66. | Wawrzyniak et al. (2017b) | 0–30 | Poland | yes | Zeolite | Ross 308 | 1 | 41 | 40 | |

| 67. | Wei et al. (2019) | 0–0.5 | China | yes | Modified Hydrated Sodium Calcium Aluminosilicate | Cobb 500 | male | 1 | 54.2 | |

| 68. | Wu et al. (2013b) | 0–20 | China | yes | Zeolite | Arbor Acres | Male | 1 | 42 | |

| 69. | Wu et al. (2013a) | 0–20 | China | yes | Zeolite | Arbor Acres | Male | 1 | 42 | |

| 70. | Wu et al. (2013c) | 0–20 | China | yes | Zeolite | Arbor Acres | 1 | 21 | ||

| 71. | Wu et al. (2015) | 0–20 | China | yes | Zeolite | Arbor Acres | 1 | 21 | ||

| 72. | Wu et al. (2016) | 0–10 | China | yes | Zeolite | Arbor Acres | 1 | 42 | ||

| 73. | Xia et al. (2004) | 0–1.5 | China | yes | Bentonite | Avian | Male | 1 | 49 | |

| 74. | Xiaohan Li et al. (2017) | 0–10 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Male | 1 | 39.8 | 42 | |

| 75. | Xu et al. (2003) | 0–1 | China | yes | Bentonite | Arbor Acres | 1 | 46.2 | 42 | |

| 76. | Yalçın et al. (2017) | 0–20 | Turkey | yes | Sepiolite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 41.2 | 42 |

| 77. | Chen et al. (2016) | 0–10 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 39 | 42 |

| 78. | Chen et al. (2016) | 0–10 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 39 | 21 |

| 79. | Chen et al. (2020) | 0–10 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 47.3 | 21 |

| 80. | Yan et al. (2019) | 1 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Ross 308 | Male | 1 | 43.2 | 42 |

| 81. | Yang et al. (2016) | 0–1.7 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 36.7 | 42 |

| 82. | Yang et al. (2017a) | 0–1.7 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 36.7 | 21 |

| 83. | Yang et al. (2017b) | 0–1.7 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | Proper Mix | 1 | 36.7 | 42 |

| 84. | Zha et al. (2022) | 0–2 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Ross 308 | Proper Mix | 1 | 46.3 | 42 |

| 85. | Zhang et al. (2017) | 0–20 | China | yes | Palygorskite | Arbor Acres | 1 | 40.2 | 42 | |

| 86. | Zhou et al. (2014) | 0–20 | China | yes | Attapulgite and Zeolite | Male | 1 | 39.2 | 42 |

Level in mg/kg as fed.

Age in day.

Weight in gram.

Rearing duration of treatment in day.

Palygorskite known as attapulgite.

Article Search

The search retrieved 3,802 items from Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, and Scopus, published between 2000 and 2022. The search terms are: "clay mineral" AND "broiler" with optional keywords such as [("performance" OR "alkaline phosphatase" OR "calcium and phosphor in serum" OR "tibia" OR "immunity")]. The outputs were further selection processes, including scientific articles, book reviews, book excerpts, and books.

Article Selection

The selection procedure followed the latest version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol (Shamseer et al., 2015; Selcuk, 2019; Page et al., 2021) which considered the previously available review. The protocol helps to minimize the risks of bias in selecting process and guarantees that the selected articles are of high quality and relevant to be included in the meta-analysis (Hayanti et al., 2022). In the first step, the article title and abstract are selected based on their relevance to the topic; acquired 189 publications related to the topic (1). Next, articles were selected when they had the digital object identifier (DOI) (2); were experimental research-based (3); had sufficient information on the materials and methods and well experimentally designed (4); reported addition levels, units, and type of clay mineral (5); the treatment of the clay mineral was not intended as an antitoxin or medication purpose (6); and broiler chickens were used as the subjects of the study (7). The representative flow of the selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. Articles are disregarded if they do not meet the selection process requirements, with the reasons provided.

Figure 1.

Process of literature selection for meta-analysis data. The process of identifying and selecting article resources for a meta-analysis study. Collected 3,802 related articles, then through the selection process, selected 86 articles that are available for data extraction.

Data Compilation and Validation

The vetting procedure produced 86 articles (Table 1). The lists of articles were used for the entire meta-analytical study. The data in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet file contains units of measurement that were standardized according to International Standard units. The constructed raw dataset resulted in 369 rows and 78 columns. Various clay minerals and their respective frequency were identified and included in the dataset: aluminosilicate (80), bentonite (107), diatomite (7), glauconite (2), halloysite (2), kaolin (28), palygorskite (41), perlite (9), sepiolite (10), and zeolite (165). The database contains information about the level of clay mineral administration in g/kg as a fed basis (i.e., the highest level was 50 and the lowest level was 0) and the 37 observed parameters that were classified into each broiler growing phase, including starter and finisher (Table 2). The parameters examined included body weight (BW, g), average daily gain (ADG, g/h/d), average daily feed intake (ADFI, g/h/d), feed conversion ratio (FCR), mortality (%), productive efficiency index, alkaline phosphatase in serum (ALP, mg/dL), calcium in serum (Ca, mg/dL), the phosphorus in serum (P, mg/dL), the weight of tibia (g). The PEI (1) formula is:

| (1) |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the meta-analysis data.

| Parameter1 | Data summary2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDP | Mean | SD | Max | Min | Q25 | Q50 | Q75 | |

| Level, mg/kg as fed | ||||||||

| Clay mineral | 369 | 8.69 | 10.1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 15 |

| Performance3 | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| BW, g | 180 | 711 | 289 | 1918 | 236 | 517 | 671 | 820 |

| ADG, g/h/d | 236 | 33.5 | 15.4 | 101 | 11.7 | 22.6 | 30.1 | 37.7 |

| ADFI, g/h/d | 241 | 48.9 | 23.3 | 187 | 19.5 | 35.2 | 44.7 | 52.2 |

| FCR | 238 | 1.5 | 0.218 | 2.99 | 0.99 | 1.36 | 1.46 | 1.58 |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| BW, g | 119 | 2128 | 430 | 3233 | 711 | 1897 | 2090 | 2431 |

| ADG, g/h/d | 152 | 69.7 | 20.1 | 155 | 22.7 | 58.2 | 70.3 | 80.7 |

| ADFI, g/h/d | 159 | 127 | 32.6 | 185 | 50.4 | 101 | 135 | 154 |

| FCR | 156 | 1.9 | 0.345 | 3.3 | 1.11 | 1.71 | 1.89 | 2.09 |

| Total | ||||||||

| BW, g | 198 | 2,087 | 459 | 3,384 | 1,104 | 1,781 | 2,090 | 2,403 |

| ADG, g/h/d | 195 | 50.9 | 13.8 | 95.2 | 19.5 | 39.8 | 50.8 | 58.1 |

| ADFI, g/h/d | 192 | 93.6 | 26.1 | 225 | 37.3 | 77.1 | 93.4 | 104.6 |

| FCR | 198 | 1.84 | 0.246 | 2.99 | 1.3 | 1.69 | 1.81 | 1.94 |

| Mortality, % | 56 | 3.9 | 3.29 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 3.33 | 5.33 |

| PEI | 184 | 264 | 73.9 | 498 | 85.6 | 215 | 268 | 316 |

| Serum, mg/dL | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| ALP | 34 | 108 | 32.5 | 194 | 61.1 | 80.9 | 105 | 132 |

| Ca | 70 | 10.1 | 1.02 | 12.3 | 5.1 | 9.63 | 10.1 | 10.7 |

| P | 70 | 6.07 | 1.97 | 8.88 | 1.48 | 5.62 | 6.5 | 7.5 |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| ALP | 45 | 188 | 97.9 | 334 | 65.9 | 92.8 | 167 | 308 |

| Ca | 60 | 10.4 | 1.84 | 16.1 | 8.03 | 9.01 | 10.2 | 10.8 |

| P | 54 | 7.07 | 3.53 | 19.8 | 2.06 | 4.92 | 6.98 | 7.8 |

| Tibia | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| Weight, g | 41 | 2.07 | 0.836 | 3.82 | 0.45 | 1.77 | 2.2 | 2.37 |

| Ash, g | 37 | 0.778 | 0.342 | 1.41 | 0.164 | 0.452 | 0.898 | 1.02 |

| Ash, % | 99 | 41.9 | 8.07 | 57.1 | 22.3 | 37.2 | 40.9 | 46 |

| Ca, % | 31 | 17.3 | 5.7 | 27.3 | 5.9 | 12.6 | 18.9 | 20.2 |

| P, % | 31 | 9.03 | 2.88 | 13.9 | 2.8 | 7.94 | 9.68 | 10.4 |

| Ca/P | 31 | 1.93 | 0.181 | 2.2 | 1.37 | 1.91 | 1.95 | 2.03 |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| Weight, g | 12 | 6.82 | 0.392 | 7.43 | 6.22 | 6.58 | 6.83 | 7.07 |

| Ash, g | 12 | 2.62 | 0.144 | 2.89 | 2.43 | 2.52 | 2.6 | 2.69 |

| Ash, % | 34 | 45.2 | 7.41 | 60.3 | 36 | 39.4 | 43.7 | 46.6 |

| Ca, % | 13 | 22.4 | 1.77 | 25 | 19.8 | 20.5 | 22.3 | 24.1 |

| P, % | 13 | 11.2 | 0.66 | 11.9 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 11.6 |

| Ca/P | 13 | 1.99 | 0.078 | 2.12 | 1.88 | 1.95 | 1.97 | 2.07 |

| Immunity, µg/mg protein | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| Jejunum IgG | 12 | 20.4 | 13.9 | 42 | 1.38 | 6.4 | 20.9 | 32.9 |

| Jejunum IgM | 8 | 2.41 | 1.05 | 3.51 | 0.94 | 1.3 | 2.97 | 3.13 |

| Jejunum IgA | 14 | 1.06 | 0.917 | 3.48 | 0.116 | 0.328 | 1.03 | 1.17 |

| Ileum of IgG | 12 | 24.7 | 14.7 | 43 | 5.65 | 6.41 | 29.6 | 35.8 |

| Ileum IgM | 8 | 2.46 | 0.864 | 3.22 | 1.19 | 1.66 | 2.96 | 3.11 |

| Ileum IgA | 14 | 1.12 | 0.797 | 3.02 | 0.105 | 0.377 | 1.25 | 1.38 |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| Jejunum IgG | 9 | 25.2 | 18.9 | 48.9 | 4.53 | 6.04 | 33.7 | 39.8 |

| Jejunum IgA | 9 | 0.836 | 0.657 | 1.53 | 0.117 | 0.145 | 1.22 | 1.46 |

| Ileum IgG | 9 | 25.8 | 18.9 | 50 | 4.56 | 6.87 | 36.2 | 40.9 |

| Ileum IgA | 9 | 0.865 | 0.726 | 1.63 | 0.097 | 0.104 | 1.33 | 1.45 |

| Cytokines, pg/mL | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| Serum IL–1β | 11 | 157 | 57.6 | 261 | 102 | 117 | 128 | 193 |

| Ileum IL–1β | 11 | 105 | 39.3 | 165 | 52 | 77.5 | 106 | 124 |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| Jejunum IL–1β | 11 | 101 | 39 | 161 | 49 | 73.5 | 101 | 121 |

ADFI = average daily feed intake; ADG = average daily gain; ALP = alkaline phosphatase; BW = body weight; Ca = Calcium; FCR = feed conversion ratio; IgA = immunoglobulin A; IgG = immunoglobulin G; IgM = immunoglobulin M; IL = interleukin; P = phosphor; PEI = productive efficiency index.

Max = maximum the feature data value; Min = minimum the feature data value; NDP = number of data points; Quantile statistics are expressed as follows: Q25: 25%; Q50: 50%; and Q75: 75%; SD = standard deviation.

The period or phase of treatment.

Where D = total days of growth and V = proportion of living broilers (one hundred percent minus mortality percentage) (Hubbard, 1999; Tauqir and Nawaz, 2001; Modirsanei et al., 2008).

Statistical Modelling

The objective of the statistical modeling was to determine the response variables affected by adding clay minerals. The studies were referred to as random effects, and the clay minerals addition was a fixed component. Then, using a linear mixed model (LMM), these 2 components were computed (St-Pierre, 2001; Sauvant et al., 2008). The LMM Equation (2) provides the foundation for metadata modeling.

| (2) |

Notation: = dependent variable, = overall mean value, = random effect of the ith study, assumed to be , = fixed effect of the jth of factor, = random interaction between the ith and jth level of factor, also assumed to be , = overall value of the linear regression coefficient of Y to X (a fixed effect), = overall coefficient value of the quadratic regression of Y to X (a fixed effect), dan = continuous values of the predictor variable (in linear and quadratic form, respectively), = random effect of the study on the regression coefficient of Y to X, assumed to be , and = residual value from unpredictable error. The interaction between the broiler strain (B) and the type of clay minerals (C) was also examined in the model. The different types of clay minerals were compared using the lsmeans package available in R software (Lenth, 2016). The least-square means of control and clay minerals groups were contrasted following the procedure of the R documentation.

A validation and significance test were conducted on the model. The significance effect was determined using a one-way analysis of variance. It is significant if the P value is < 0.05 and tends to be significant when P value is between 0.05 and 0.10. Pl represents the P value for the linear constant () and Pq represents the P value of the quadratic constant (). The validation test was conducted using the root mean square error (RMSE) and Nakagawa determination coefficient (R2) or (Nakagawa and Schielzeth, 2013; Nakagawa et al., 2017; R Core Team, 2022). Below is the equation for RMSE (3) and R2 (4).

| (3) |

| (4) |

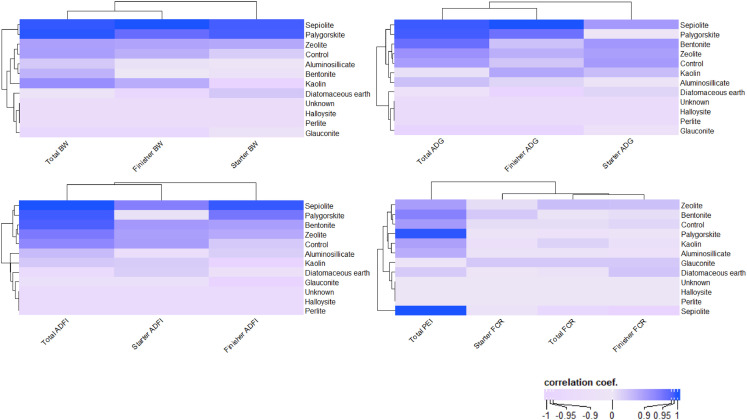

Note: = actual value, = estimated value, = number of data point, is the variant of a fixed factor, is the sum of all variants of the component, is the variant due to the predictor dispersion, and is the specific distribution of the variant. R version 4.2.0, also known as "Vigorous Calisthenics", and accompanying libraries, such as lme4 (for LMM construction) and lsmeans (for least-squares means test), are used to model and statistically test LMM. In addition, using mixed models methodology, categorical analysis was performed to evaluate the effects of clay minerals type on the response variables. The number of replications was used as a weighting factor and Tukey was used for multiple comparisons of the least-square means (Irawan et al., 2022). The Pearson correlation matrix between mineral clay types and growth performance (BW, ADG, ADFI, FCR, and PEI) is then given as a heatmap (Figure 2) (Brownstein et al., 2019; Sholikin et al., 2019).

Figure 2.

Matrix correlation of clay mineral on broiler performance at starter, finisher, and total period of treatment. Body weight (BW, g), average daily gain (ADG, g/h/d), average daily feed intake (ADFI, g/h/d), feed convertion ratio (FCR), and performance efficiency index (PEI).

RESULTS

Table 3 displays the effects of clay minerals supplementation on broiler performance, blood serum, tibia, and immunity. Clay additives significantly increased body weight (Pl = 0.044 and Pq = 0.027) and decreased FCR (P < 0.01) during the starter period. In the finisher phase, performance parameters such as BW, ADG, ADFI, and FCR experienced significant (P < 0.01) improvements. In total period, the administration of clay minerals resulted in a significant (P < 0.01) improvement in growth performance, as reflected by the increase in BW, ADG, and PEI. For every gram of clay minerals added, improvement rates of BW, ADG, and PEI were 4.12 g, 0.0714 g/h/d, and 0.648, respectively, based on the linear model. In contrast, for every gram of clay minerals added, the FCR was decreased (Pl = 0.003 and Pq < 0.001) by 0.00223 units. The application of clay minerals in the diet did not affect other performance parameters such as ADFI and mortality.

Table 3.

Determine the impact of adding clay mineral on broiler performance, blood serum, tibia, and immunity.

| Parameter1 | Mathematical models2 |

C × B3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept () |

Gradient ( or ) |

P values | RMSE | R2 | ||||

| Value | SE | Value | SE | |||||

| Performance4 | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| BW, g | 747 | 28.5 | 0.668 | 0.331 | 0.044 | 29.8 | 0.98 | 0.962 |

| −0.0106 | 0.00476 | 0.027 | ||||||

| ADG, g/h/d | 34.5 | 1.34 | 0.0012 | 0.0106 | 0.91 | 1.72 | 0.982 | 0.873 |

| ADFI, g/h/d | 50.5 | 2.17 | 0.0331 | 0.0197 | 0.095 | 3.24 | 0.975 | 0.991 |

| FCR | 1.48 | 0.019 | 0.00162 | 0.000388 | <0.001 | 0.064 | 0.873 | 0.296 |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| BW, g | 2095 | 60.2 | 5.86 | 1.2 | <0.001 | 67.3 | 0.97 | 0.003 |

| −0.082 | 0.0224 | <0.001 | ||||||

| ADG, g/h/d | 66.9 | 2.44 | 0.298 | 0.0738 | <0.001 | 3.5 | 0.95 | 0.462 |

| −0.00567 | 0.00197 | 0.005 | ||||||

| ADFI, g/h/d | 126 | 4.03 | 0.12 | 0.051 | 0.018 | 5.47 | 0.96 | 0.41 |

| FCR | 1.98 | 0.043 | −0.00517 | 0.00157 | 0.001 | 0.076 | 0.93 | 0.02 |

| 0.000114 | 0.0000421 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Total | ||||||||

| BW, g | 2,106 | 48.1 | 4.12 | 0.681 | <0.001 | 53.2 | 0.98 | <0.001 |

| −0.0527 | 0.0116 | <0.001 | ||||||

| ADG, g/h/d | 51.3 | 1.45 | 0.0714 | 0.0208 | 0.001 | 1.72 | 0.98 | 0.061 |

| −0.00087 | 0.00031 | 0.005 | ||||||

| ADFI, g/h/d | 95.9 | 2.765 | 0.0372 | 0.0219 | 0.091 | 3.56 | 0.974 | 0.004 |

| FCR | 1.87 | 0.024 | −0.00223 | 0.000749 | 0.003 | 0.064 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| 0.0000402 | 0.000011 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mortality, % | 3.87 | 0.57 | 0.0174 | 0.0221 | 0.433 | 2.06 | 0.511 | 0.875 |

| PEI | 262 | 8.12 | 0.648 | 0.176 | <0.001 | 13.2 | 0.96 | <0.001 |

| −0.00958 | 0.00292 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Serum, mg/dL | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| ALP | 106 | 8.31 | −0.0222 | 0.532 | 0.967 | 17.5 | 0.567 | 0.946 |

| Ca | 10.1 | 0.178 | 0.00205 | 0.00927 | 0.826 | 0.684 | 0.403 | 0.885 |

| P | 6.07 | 0.406 | −0.035 | 0.0142 | 0.018 | 0.403 | 0.94 | 0.741 |

| 0.000678 | 0.000322 | 0.041 | ||||||

| Finisher | ||||||||

| ALP | 197 | 23.3 | −0.0263 | 0.402 | 0.948 | 20.8 | 0.917 | 0.005 |

| Ca | 10.4 | 0.408 | 0.00831 | 0.00481 | 0.092 | 0.44 | 0.915 | 0.16 |

| P | 7.04 | 0.847 | −0.00668 | 0.00372 | 0.081 | 0.301 | 0.989 | 0.003 |

| Tibia | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| Weight, g | 2.11 | 0.248 | 0.00461 | 0.00369 | 0.221 | 0.322 | 0.789 | <0.001 |

| Ash, g | 0.809 | 0.108 | 0.00209 | 0.00141 | 0.146 | 0.122 | 0.818 | 0.964 |

| Ash, % | 44.5 | 1.65 | −0.0176 | 0.0422 | 0.678 | 2.96 | 0.845 | 0.001 |

| Ca, % | 18.9 | 1.53 | −0.134 | 0.113 | 0.246 | 3.03 | 0.525 | 0.829 |

| P, % | 9.77 | 0.73 | −0.0638 | 0.0407 | 0.13 | 1.06 | 0.713 | 0.106 |

| Ca/P | 1.94 | 0.047 | −0.00107 | 0.00551 | 0.847 | 0.167 | 0.074 | 0.012 |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| Weight, g | 6.78 | 0.254 | 0.0019 | 0.00232 | 0.437 | 0.126 | 0.884 | 0.929 |

| Ash, g | 2.65 | 0.075 | −0.0127 | 0.00269 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0.91 | 0.001 |

| 0.000292 | 0.0000516 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Ash, % | 46.2 | 2.48 | 0.0327 | 0.0155 | 0.047 | 1.02 | 0.977 | 0.227 |

| Ca, % | 21.3 | 0.75 | 0.0569 | 0.0148 | 0.006 | 0.462 | 0.885 | 0.179 |

| P, % | 11.1 | 0.327 | 0.00349 | 0.00515 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 0.914 | 0.277 |

| Ca/P | 1.93 | 0.024 | 0.00446 | 0.00127 | 0.008 | 0.047 | 0.542 | 0.082 |

| Immunity, µg/mg protein | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| Jejunum IgG | 16.9 | 9.04 | 0.869 | 0.449 | 0.089 | 2.89 | 0.951 | 0.319 |

| Jejunum IgM | 2.05 | 1.08 | 0.0375 | 0.0281 | 0.238 | 0.161 | 0.983 | 0.738 |

| Jejunum IgA | 1.05 | 0.496 | 0.0516 | 0.00517 | <0.001 | 0.067 | 0.993 | 0.149 |

| Ileum IgG | 22.2 | 9.52 | 0.689 | 0.371 | 0.1 | 2.38 | 0.97 | 0.736 |

| Ileum IgM | 2.11 | 0.933 | 0.0543 | 0.0161 | 0.02 | 0.092 | 0.992 | 0.992 |

| Ileum IgA | 1.03 | 0.38 | 0.056 | 0.00515 | <0.001 | 0.067 | 0.99 | 0.418 |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| Jejunum IgG | 22.1 | 18.1 | 0.979 | 1.47 | 0.53 | 4.03 | 0.963 | 0.04 |

| Jejunum IgA | 0.66 | 0.626 | 0.184 | 0.0753 | 0.058 | 0.067 | 0.99 | 0.29 |

| −0.0393 | 0.0191 | 0.095 | ||||||

| Ileum IgG | 22.1 | 18.3 | 1.45 | 1.22 | 0.279 | 3.34 | 0.976 | 0.287 |

| Ileum IgA | 0.768 | 0.695 | 0.0172 | 0.0265 | 0.541 | 0.073 | 0.992 | 0.235 |

| Cytokines, pg/mL | ||||||||

| Starter | ||||||||

| Serum IL–1β | 164 | 38.5 | 0.269 | 0.802 | 0.747 | 15 | 0.923 | |

| Ileum IL–1β | 108 | 29 | −0.377 | 0.358 | 0.327 | 6.63 | 0.973 | |

| Finisher | ||||||||

| Jejunum IL–1β | 105 | 28.6 | −0.421 | 0.401 | 0.329 | 7.45 | 0.965 | |

ADFI = average daily feed intake; ADG = average daily gain; ALP = alkaline phosphatase; BW = body weight; Ca = Calcium; FCR = feed conversion ratio; IgA = immunoglobulin A; IgG = immunoglobulin G; IgM = immunoglobulin M; IL = interleukin; P = phosphor; PEI = productive efficiency index.

= The first row of each parameter is a linear coefficient; the second row is a quadratic coefficient; R2 = R squared Nakagawa for validate linear mixed model; RMSE = root mean square error; SE = standard error.

B = broiler breed; C = level of clay mineral (g/kg as fed).

The period or phase of treatment.

The P content of the serum linearly decreased (Pl = 0.018 and Pq = 0.041) when supplemented during the starter phase up to 0.035 mg/dL. In the finisher phase, serum Ca concentration tended to increase (P = 0.092) and P concentration in blood serum tended to lower (P = 0.081). ALP concentration was not affected by adding clay minerals at the starter and finisher. The tibia ash composition was increased (P = 0.047). Similarly, the composition of Ca and the ratio of Ca to P were considerably increased (P = 0.006 and P = 0.008, respectively). In the starter and finisher phases, other tibia characteristics such as weight, ash, Ca, P, and Ca/P were not significant (except for ash, Ca, and Ca/P in the finisher phase).

During the starter phase, the clay minerals administration linearly increased (P < 0.01) the IgA concentration in the jejunum and ileum. Ileal IgM concentration was also linearly increased (P = 0.02), while jejunal IgG tended to increase (P = 0.089). In the finisher phase, jejunal IgA was the only variable found to be quadratically affected (Pl = 0.058 and Pq = 0.095) by the levels of clay minerals. In addition, increasing levels of clay minerals did not affect the expression of cytokines based on the concentration of IL-1β in serum, jejunum, and ileum. The lack of significant effect from LMM regression analysis on many parameters could be associated with variations from different clay minerals within studies.

Table 4 summarizes the different effects of clay minerals on the response variables. Clay minerals did not impact ADG, ADFI, and FCR during the starter phase (P > 0.05). However, more excellent (P < 0.05) BW in the starter and finisher phases was associated with some clay minerals treatment, including aluminosilicate, diatomaceous, halloysite, kaolin, smectite, and zeolite, compared to broiler chickens fed basal ration. ADFI and FCR were higher (P < 0.05) when broiler chickens were treated with aluminosilicate, while the other clay minerals did not affect those parameters. Compared to all treatments, the control exhibited the highest level of P in blood serum (6.15 mg/dL; P = 0.004) at the starter phase. Compared to other treatments (such as calcium bentonite and sodium bentonite), calcium concentration in blood serum at the finisher phase was considerably more significant in the bentonite treatment (11.3 mg/dL; P = 0.003). Compared to other clay mineral treatments, bentonite treatment tended to have a more significant ALP activity (219 mg/dL; P = 0.063). Other blood serum values relating to Ca, P, and ALP were insignificant. The weight and mineral makeup of the broiler tibia were not significantly affected by the type of clay mineral. The IgA was significantly higher in the jejunum and ileum (P < 0.01 and P = 0.003, respectively) at starter phase after the aluminosilicate treatment (e.g., hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate and silicate). In addition, these parameters concentration become 2.22 and 2.3 µg/mg protein, respectively. Moreover, other immunity characteristics were not significant owing to the various clay mineral types.

Table 4.

The type of clay mineral affects the performance, blood serum, tibia, and immunity of broilers.

| Parameter1 | Treatment2 |

SEM3 | P values | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con | Clay 1 | Clay 2 | Clay 3 | Clay 4 | Clay 5 | Clay 6 | Clay 7 | Clay 8 | Clay 9 | Clay 10 | |||

| Performance4 | |||||||||||||

| Starter | |||||||||||||

| BW, g | 812b | 835a | 816b | 841a | 798b | 846a | 844a | 833ab | 815b | 837a | 836a | 36.9 | <0.001 |

| ADG, g/h/d | 39.1 | 40.7 | 39.3 | 40.2 | 38.4 | 40.8 | 42.3 | 38.3 | 38.5 | 40.2 | 39.7 | 5.3 | 0.225 |

| ADFI, g/h/d | 55.7 | 56.5 | 57.2 | 57.2 | 57.5 | 58.5 | 48.3 | 53.6 | 55.6 | 56.5 | 56.3 | 9.9 | 0.844 |

| FCR | 1.46 | 1.46 | 1.47 | 1.47 | 1.48 | 1.48 | 1.26 | 1.47 | 1.48 | 1.44 | 1.45 | 0.11 | 0.346 |

| Finisher | |||||||||||||

| BW, g | 2,193c | 2,516a | 2,198c | 2,280a | 2,098c | 2,300a | 2,407a | 2,264b | 2,235b | - | 2,254b | 157 | <0.001 |

| ADG, g/h/d | 70.7b | 87.5a | 72b | 74.6a | 67b | 73.8a | 79a | 70.2b | 71.2b | - | 72.7b | 10.1 | <0.001 |

| ADFI, g/h/d | 130b | 152a | 131b | 137b | 126b | 119b | 131b | 127b | 130b | - | 132b | 16.5 | <0.001 |

| FCR | 1.92a | 1.65c | 1.89a | 1.91b | 1.97a | 1.74b | 1.83b | 1.9a | 1.9a | - | 1.9a | 0.141 | <0.001 |

| Total | |||||||||||||

| BW, g | 2,263b | 2,339a | 2,282b | 2,248b | 2,166b | 2,346a | 2,347a | 2,322a | 2,297b | - | 2,341 | 108 | <0.001 |

| ADG, g/h/d | 56.2 | 58.1 | 57.4 | 55.6 | 53.6 | 58.2 | 57.2 | 55.6 | 56.2 | - | 57.5 | 4.9 | 0.22 |

| ADFI, g/h/d | 95.8 | 97.7 | 97.6 | 97.9 | 99.7 | 86.9 | 94.1 | 95.6 | - | 95.8 | 96.8 | 1.54 | 0.368 |

| FCR | 1.87 | 1.88 | 1.86 | 1.93 | 1.98 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 1.89 | - | 1.85 | 1.84 | 0.014 | 0.33 |

| Mortality, % | 4.15 | 2.46 | 4.3 | 3.99 | - | 3.4 | - | 2.05 | - | - | 4.33 | 0.349 | 0.84 |

| PEI | 261a | 266ab | 263ab | 253ab | 220ab | 307ab | 272ab | 268ab | 249ab | 277ab | 274b | 4.49 | 0.001 |

| Serum, mg/dL | |||||||||||||

| Starter | |||||||||||||

| ALP | 105 | 104 | 92.6 | 77.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 133 | 5.57 | 0.106 |

| Ca | 10.2 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 10.8 | - | - | - | - | 8.54 | - | 10.1 | 0.122 | 0.564 |

| P | 6.15a | 5.74ab | 5.24b | - | - | - | - | - | 6.05ab | - | 5.98ab | 0.236 | 0.004 |

| Finisher | |||||||||||||

| ALP | 200ab | - | 219a | - | - | 212ab | 211ab | - | - | 209ab | 166b | 14.6 | 0.063 |

| Ca | 10.3b | - | 11.3a | - | - | 11.5ab | 10.5ab | - | 9.98ab | 10.6ab | 10.2b | 0.237 | 0.003 |

| P | 6.96 | - | 6.94 | - | - | 7.75 | 7.35 | - | 6.84 | 6.94 | 6.86 | 0.48 | 0.8 |

| Tibia | |||||||||||||

| Starter | |||||||||||||

| Weight, g | 2.13 | 2.14 | 2.11 | 2.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.26 | 0.131 | 0.967 |

| Ash, g | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.88 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.84 | 0.056 | 0.999 |

| Ash, % | 44. 7 | 44.9 | 43.8 | 44. 6 | - | - | - | - | 45.6 | - | 44.1 | 0.81 | 0.965 |

| Ca, % | 18.8 | 19.4 | 19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16 | 1.03 | 0.346 |

| P, % | 9.71 | 9.38 | 9.73 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8.52 | 0.518 | 0.221 |

| Ca/P | 1.95 | 2.01 | 1.95 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.9 | 0.033 | 0.888 |

| Finisher | |||||||||||||

| Weight, g | 6.83 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6.82 | 0.113 | 0.936 |

| Ash, g | 2.66 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.6 | 0.42 | 0.434 |

| Ash, % | 46.2 | - | 47.5 | - | - | - | 47.5 | - | - | 46.8 | 46.3 | 1.27 | 0.642 |

| Ca, % | 21.4 | - | 22.6 | - | - | - | 23.2 | - | - | - | 22.3 | 0.49 | 0.266 |

| P, % | 11.0 | - | 11.4 | - | - | - | 11.3 | - | - | - | 11 | 0.18 | 0.485 |

| Ca/P | 1.95 | - | 1.97 | - | - | - | 2.05 | - | - | - | 2.03 | 0.027 | 0.279 |

| Immunity, µg/mg protein | |||||||||||||

| Starter | |||||||||||||

| Jejunum IgA | 1.06b | 2.22a | - | - | - | - | - | 1.21b | - | - | 1.13b | 0.245 | <0.001 |

| Jejunum IgM | 2.09 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.18 | - | - | - | 0.37 | 0.632 |

| Jejunum IgG | 16.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20.3 | - | - | 19.4 | 4.02 | 0.495 |

| Ileum IgA | 1.08b | 2.3a | - | - | - | - | - | 1.20b | - | - | 1.06b | 0.213 | 0.003 |

| Ileum IgM | 2.13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.31 | - | - | - | 0.305 | 0.286 |

| Ileum IgG | 22.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25.2 | - | - | 22.5 | 4.25 | 0.738 |

| Finisher | |||||||||||||

| Jejunum IgA | 0.68 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.88 | - | - | 0.7 | 0.218 | 0.342 |

| Jejunum IgG | 22.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | 21.8 | 6.29 | 0.927 |

| Ileum IgA | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.75 | - | - | 0.81 | 0.242 | 0.846 |

| Ileum IgG | 22.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 24 | - | - | 24.5 | 6.28 | 0.928 |

| Cytokines, pg/mL | |||||||||||||

| Starter | |||||||||||||

| Serum IL–1β | 168 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 148 | - | - | 175 | 17.4 | 0.599 |

| Jejunum IL–1β | 107 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 95.4 | - | - | 99.5 | 11.8 | 0.374 |

| Finisher | |||||||||||||

| Ileum IL–1β | 110 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 102 | - | - | 102 | 11.9 | 0.507 |

ADFI = average daily feed intake; ADG = average daily gain; ALP = alkaline phosphatase; BW = body weight; Ca = Calcium; FCR = feed conversion ratio; IgA = immunoglobulin A; IgG = immunoglobulin G; IgM = immunoglobulin M; IL = interleukin; P = phosphor; PEI = productive efficiency index.

Con = control; Clay 1 = aluminosilicate (e.g., hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate and silicate); Clay 2 = bentonite (e.g., calcium bentonite and sodium bentonite); Clay 3 = diatomaceous earth (diatomite); Clay 4 = glauconite; Clay 5 = halloysite; Clay 6 = kaolin; Clay 7 = palygorskite (attapulgite); Clay 8 = perlite; Clay 9 = sepiolite; Clay 10 = zeolite.

SEM = Standard error of the mean (n = NDP in Table 2).

The period or phase of treatment.

Different letters in the same row have a significant difference with a 5% error degree.

DISCUSSION

Previous research has demonstrated that mineral clay has a high absorption capacity due to its fine particle size (some are nano-sized, 5–50 nm) (Ganguly et al., 2011; Al-Beitawi et al., 2017; Ujilestari et al., 2019), thin particle shape (Slamova et al., 2011), and vast surface area (Ouachem et al., 2015). Clay can absorb substances or materials to get rid of things like antinutrients, heavy metals, pathogenic microorganisms, poisonous compounds, and viruses, as illustrated in Figure 3 (Slamova et al., 2011). As a growth promoter, the advantages of clay and clay minerals are more focused on conditioning the digestive tract environment, such as boosting the quality of intestinal health by absorbing toxic chemicals or bacteria (Rodríguez-Rojas et al., 2015), enhancing the performance of various digestive enzymes (Zabiulla et al., 2021), and regulating pH (Gadde et al., 2017).

Figure 3.

Mode of action of clay and clay mineral in the small intestine (modified from Gadde et al., 2017). Clay and clay minerals bind antinutrients, pathogens, and toxins in the broiler small intestine by absorbing and expelling them. This condition will improve the gut health, as shown by a rise in increased enzyme activity and lactic acid bacteria.

In addition, clay minerals catalyze the digestive process (Zhang et al., 2021). Zeolite plays an active role in triggering enzyme activation and enhancing the performance of digestive enzymes (Smeets et al., 2020). The pores of clays are rich in metal ions that can help to maintain enzyme stability (thermal and pH) and act as an activating agent for lipases, proteases, and xylanase (Naseri et al., 2018; Smeets et al., 2020; Dashtestani et al., 2021). Such favorable effects on enzyme secretion and activation can explain the improvement of growth performance in broiler chickens, as confirmed by the increase in ADG and the decrease in FCR values. This meta-analysis also validated that ADFI was not affected by the clay minerals, indicating that they did not interfere with palatability. Compared to other clay minerals, zeolite significantly affected the phenotypes parameter, such as an increase in BW and ADG. Digestive enzymes, including lipase, protease, and xylanase are actively catalyzed by zeolite and activated by it (Smeets et al., 2020; Dashtestani et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). As a result, the zeolite treatment absorption process operates more effectively, leading to excellent production performance.

Clay enhances the PEI value; the quantity of PEI influences broiler performance; as the PEI value grows, so does the productivity and efficiency of the broiler. Santurio et al. (1999) study on bentonite administration in aflatoxin stress treatment showed that it might increase BW, ADG, FCR, PEI, and decrease mortality rate over the control. The meta-analysis revealed that the highest PEI was formed by zeolite (PEI = 274). This result causes zeolite capacity to promote digestion and absorption. Zeolite stimulates the formation of beneficial bacteria in the intestine during digestion (Lebedynets et al., 2004; Ferreira et al., 2012; Durán et al., 2016; Bolandi et al., 2021). Similarly, clays such as clinoptilolite (zeolite) and sodium bentonite are used (Modirsanei et al., 2008; Attar et al., 2019).

Fascinatingly, clay mineral does not influence broiler meat mineral (Abaş et al., 2011). Following a meta-analysis of ALP investigations, adding clay minerals did not affect the serum concentration of ALP. This remark implies that clay does not interfere with the metabolism of serum phosphorus. ALP is a member of the class of metalloenzymes that act as catalysts or biomineralizing agents in blood serum (Turan et al., 2011; Bhattarai et al., 2014; Abalymov et al., 2020). This metalloenzyme is responsible for the feed derived inorganic pyrophosphate release of phosphate ions and the crystallization of that compound into hydroxyapatite (de Souza Nakagi et al., 2013; Abalymov et al., 2020). The amount of ALP in the blood serum was unaffected by adding clay minerals. This implies that although serum P metabolism is unaffected by clay, P levels drop during the starter phase. The rate of P deposition in the tibia, the balance of Ca:P in the diet, and the pace of bone formation during the starter phase were assumed to be the causes of the drop in P (Kalantar-Zadeh et al., 2010; Abaş et al., 2011; Saçakli et al., 2015). Aluminosilicates, such as kaolin and zeolite, are minerals resistant to nutrient absorption in addition to these factors (Lemos et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015).

Zeolite treatment often resulted in lower serum ALP and Ca levels and higher P levels than the other classes of clays. Conversely, bentonite treatment led to greater ALP, Ca, and reduced P. It was suggested that the distinction between the two clays stems from their chemical structure, attraction for metal ions, and mineral homeostasis in serum (Dos Anjos et al., 2015; Du et al., 2019; Alharthi et al., 2022). The aluminosilicate crystal structure of zeolite comprises SiO4 and AlO4 tetrahedra and takes on a 3-dimensional shape (Nadziakiewicza et al., 2019). The zeolite primary charge is a negative charge caused by aluminum silicate (Narayanan et al., 2020). Additionally, zeolites feature honeycomb-shaped holes (microspores or nanoporous in size) that may hold metal ions and organic molecules (Shariatmadari, 2008; Wattanawong and Aht-Ong, 2021). Meanwhile, bentonite has a flexible, uneven heterogeneous structure that serves as a colloid (Prabhu and Prabhu, 2018). Na+ and Ca2+ ions comprise most of the bentonite exchangeable positive charge (Nadziakiewicza et al., 2019). With this knowledge, it is clear that bentonite contains Ca2+ and has the potential to swap this ion for other valence ions, allowing Ca2+ to be taken into the body. Additionally, increased serum Ca2+ concentration increases ALP concentration and a reduction in P concentration (Amer et al., 2018; Al-Zghoul et al., 2019; Kriseldi et al., 2021). Administration of clay minerals for more than 21 d of maintenance (finisher period) increased blood minerals, leading to a rise in tibia mineral content.

Due to the clay minerals addition, the tibia macromineral composition varies naturally, and ash as a biomineral composition predictor was changed. Clay minerals impact calcium deposition in the tibia. According to recent research by Safaeikatouli et al. (2012), bentonite, kaolin, and zeolite enhance the amount of Ca deposition in the tibia. The presence of clay-derived Ca2+ minerals, such as calcium bentonite, which are also absorbed in the small intestine, may cause an increase in Ca deposition, as seen in the tibia. The Ca2+ ions of bentonite may readily be exchanged for metal ions or other cationic substances (Moosavi, 2017). As a result, cells and other structures like the tibia will retain extra calcium ions in the blood. In addition, clays such as attapulgite, bentonite, and zeolite feature holes that are effective for inducing the binding and release of calcium carbonate from inorganic sources, thus increasing Ca2+ bioavailability (Moosavi, 2017; Hubadillah et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018a; Nadziakiewicza et al., 2019; Hartati et al., 2020; Sandomierski et al., 2020). High Ca levels can cause a reduction in P absorption in the small intestine and may block parathyroid hormone action as the following mechanism to maintain body homeostasis (Kalantar-Zadeh et al., 2010; Turan et al., 2011; Wilkens and Muscher-Banse, 2020). The implication is that; 1) several mechanisms regulate calcium balance, including calcium distribution into cells (e.g., through transcellular and paracellular channels); 2) increase bone density in tibia; and 3) induce the synthesis of vitamin D, which is vital for P absorption (Behera et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Wilkens and Muscher-Banse, 2020). Clays such as aluminosilicates, bentonite, kaolin, and zeolite in broiler feed might enhance Ca deposition (Safaeikatouli et al., 2012; Bouderoua et al., 2016; Attar et al., 2019).

According to previous research, changes in IgA and IgM levels indicate that the use of clay minerals impacts the immunity of broiler chickens. IgA and IgM are primarily responsible for inhibiting microorganisms or antigens in the small intestinal lumen. Antigens are deposited by IgM so that phagocytic cells may promptly consume them. Additionally, B cell-produced activated IgA acts as the primary mucosal effector and shields the intestinal epithelium from hazardous substances and pathogenic microbes (Corthésy, 2013). IgA also produces antigen-absorbing mucus, inhibits antigen access at epithelial receptors, and facilitates antigen removal with the help of peristaltic mechanisms and mucociliary activity (Peng et al., 2005; Racine and Winslow, 2009; Zhou et al., 2014; Bolandi et al., 2021). According to Chen et al. (2016a) results, adding palygorskite into the feed caused IgA and IgM levels to rise during the starter phase. Similar results were found by Tang et al. (2014), who found that the addition of clinoptilolite, which binds to zinc minerals, boosted IgA levels in the lumen of the jejunum of 21-day-old broiler chickens. The rise in IgA and IgM levels in the intestinal lumen indicates that clay minerals are efficient immunomodulatory agents, according to the prior explanation and metadata findings (e.g., jejunum and ileum). Thus, clay minerals directly contribute to maintaining the microflora ecology and improving broiler health by enhancing the immunological condition in the intestinal lumen, particularly the aluminosilicates and zeolite types of clay minerals, which enhance broiler immunological response. Most of the clay referred to in this meta-analysis has been activated by altering the clay pores (Wei et al., 2019). Clay minerals used various treatments to enhance the alterations, including acids, bases, ionic surfactants, mechanical (nano/micro grinding), polyhydroxy cation, and heat (Tole et al., 2019; Thiebault, 2020). The primary goal of activating clay minerals is to improve the adsorbent surface area and adsorption capacity for more effective use as an adsorbent (Tole et al., 2019). The immune system is strongly impacted by zeolite. Similar to superantigens, aluminosilicates, and silicates operate as nonspecific immunomodulators (SAgs). SAgs are sensitive to bacterial toxins and viruses that bind to proteins from T-cell receptors, create major histocompatibility, and drive the development of protein antigen-presenting cells (Ivkovic et al., 2004; Tang et al., 2022). This hypothesis is consistent with meta-analysis results showing that clay minerals could boost immunoglobulin levels and broiler health (surpress mortality percentage). In agreement with the results of Neeff et al. (2013), hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate lowers mortality from an aflatoxin B1 contaminated diet. Smectite and sodium bentonite may increase broiler performance and lessen the toxicological impact of aflatoxin on the liver, according to the results of another trial (Magnoli et al., 2011; Zabiulla et al., 2021). Moreover, Liu et al. (2018b) and Nadziakiewicz et al. (2022) stated that clay minerals might increase the production of significant quantities of IgA and alleviate intestinal, also gizzard damage caused by aflatoxin when employed as detoxifying agents.

CONCLUSION

Clay minerals positively affect body weight gain, feed conversion, performance index, IgA, and IgG of broilers. Additionally, clay minerals do not affect macromineral metabolism and blood serum absorption. According to FCR, the optimal amount of clay minerals was 22.6 g/kg for the finisher period and around 27.6 g/kg for the total period. Recommended clay minerals might nicely combine with other feed additives to enhance adsorption. Also, it can be an active form for specific applications, such as enhancing the absorption of Ca and P in the ileum.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) of The Republic of Indonesia, which has provided training on the development and writing of scientific papers based on meta-analysis, is to be thanked by the authors. Also, thanks to Research Organization for Agriculture and Food.

Author Contributions: Mohammad Firdaus Hudaya, Muhammad Ainsyar Harahap, Novia Qomariyah, Sari Yanti Hayanti, Sadarman, Santiananda Arta Asmarasari, and Tri Ujilestari (Tabulated the data) (Validating the database) (Review the paper). Mohammad Miftakhus Sholikin and Teguh Wahyono (Conceived and designed the analysis) (Performed the analysis and visualization) (Writing–original draft). Ahmad Sofyan, Barlah Rumhayati, Cecep Hidayat, Hendra Herdian, Ifa Manzila, Rantan Krisnan, Tri Puji Priyatno, and Windu Negara (Validating the result data) (Writing–review editing) (Language correction). Hardi Julendra, Nahrowi, and Wulandari (Validating the result data) (Review the paper) (Supervision). Agung Irawan, Danung Nur Adli, and Rahmat Budiarto (Wrote the paper) (Writing–review editing) (Language correction). Anuraga Jayanegara (Conceptualization) (Project administration) (Writing–review editing).

Disclosures

The authors agree and declare that there is no conflict of interest in the writing of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Abalymov A., Van Poelvoorde L., Atkin V., Skirtach A.G., Konrad M., Parakhonskiy B. Alkaline phosphatase delivery system based on calcium carbonate carriers for acceleration of ossification. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020;3:2986–2996. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abaş İ., Bİlal T., Esecelİ H. The effect of organic acid, zeolite, or their combination on performance, some serum indices, and ileum pH values in broilers fed with different phosphorus levels. Turkish J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2011;35:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi Pour A.R., Kermanshahi H., Golian A. Effects of conditioning time and activated sodium bentonite on pellet quality, performance, intestinal morphology, and nutrients retention in growing broilers fed wheat-soybean meal diets. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021;277:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Adli D., Sjofjan O., Irawan A., Utama D., Sholikin M., Nurdianti R., Nurfitriani R., Hidayat C., Jayanegara A., Sadarman S. Effects of fibre-rich ingredient levels on goose growth performance, blood profile, foie gras quality and its fatty acid profile: A meta-analysis. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2022;31:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Beitawi N.A., Momani Shaker M., El-Shuraydeh K.N., Bláha J. Effect of nanoclay minerals on growth performance, internal organs and blood biochemistry of broiler chickens compared to vaccines and antibiotics. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2017;45:543–549. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nass Y.A., Al-Zenki F.S., Al-Saffar E.A., Abdullah F.K., Al-Bahouh M.E., Mashaly M. Zeolite as a feed additive to reduce salmonella and improve production performance in broilers. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2011;10:448–454. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zghoul M.B., Alliftawi A.R.S., Saleh K.M.M., Jaradat Z.W. Expression of digestive enzyme and intestinal transporter genes during chronic heat stress in the thermally manipulated broiler chicken. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:4113–4122. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alharthi A.S., Al Sulaiman A.R., Aljumaah R.S., Alabdullatif A.A., Ferronato G., Alqhtani A.H., Al-Garadi M.A., Al-sornokh H., Abudabos A.M. The efficacy of bentonite and zeolite in reducing aflatoxin B1 toxicity on production performance and intestinal and hepatic health of broiler chickens. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022;21:1181–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J.A.S., Ponnuraj N.P., Lee J.J., Utterback P., Gaskins H.R., Dilger R.N., Pettigrew J.E. Effects of dietary clays on performance and intestinal mucus barrier of broiler chicks challenged with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and on goblet cell function in vitro. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:839–847. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzueta C., Ortiz L.., Rebolé A., Rodríguez M.., Centeno C., Treviño J. Effects of removal of mucilage and enzyme or sepiolite supplement on the nutrient digestibility and metabolyzable energy of a diet containing linseed in broiler chickens. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2002;97:169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Amer S.A., Kishawy A.T.Y., ELseddawy N.M., Abd El-Hack M.E. Impacts of bentonite supplementation on growth, carcass traits, nutrient digestibility, and histopathology of certain organs of rabbits fed diet naturally contaminated with aflatoxin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25:1340–1349. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attar A., Kermanshahi H., Golian A., Abbasi Pour A., Daneshmand A. Conditioning time and sodium bentonite affect pellet quality, growth performance, nutrient retention and intestinal morphology of growing broiler chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2019;60:777–783. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2019.1663493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar H.R.E., Kambiz N.A., Yahya E.N., Mohammad M. Effect of different levels and particle sizes of perlite on serum biochemical factors of broiler chicks. African J. Biotechnol. 2011;10:3232–3236. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C.A., Latimer G.W., Barr A.C., Wigle W.L., Haq A.U., Balthrop J.E., Kubena L.F. Efficacy of montmorillonite clay (NovaSil PLUS) for protecting full-term broilers from aflatoxicosis. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2006;15:198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Banaszak M., Biesek J., Adamski M. Aluminosilicates at different levels in rye litter and feed affect the growth and meat quality of broiler chickens. Vet. Res. Commun. 2022;46:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s11259-021-09827-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera J., Ison J., Tyagi S.C., Tyagi N. The role of gut microbiota in bone homeostasis. Bone. 2020;135:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai T., Bhattacharya K., Chaudhuri P., Sengupta P. Correlation of common biochemical markers for bone turnover, serum calcium, and alkaline phosphatase in post-menopausal women. Malaysian J. Med. Sci. 2014;21:58–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolandi N., Hashemi S.R., Davoodi D., Dastar B., Hassani S., Ashayerizadeh A. Performance, intestinal microbial population, immune and physiological responses of broiler chickens to diet with different levels of silver nanoparticles coated on zeolite. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021;20:497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Bouderoua Y., Ait-Saada D., Selselet-A G., Mourot J., Perier C., Robin G. Effects of dietary addition of raw and treated calcium bentonite on growth, digesta characteristics, blood profiles and meat fatty acids composition of broilers chicks. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2016;11:805–814. [Google Scholar]

- Broom L.J. Gut barrier function: Effects of (antibiotic) growth promoters on key barrier components and associations with growth performance. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:1572–1578. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein N.C., Adolfsson A., Ackerman M. Descriptive statistics and visualization of data from the R datasets package with implications for clusterability. Data Br. 2019;25:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2019.104004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabuk M., Alcicek A., Bozkurt M., Akkan S. Effect of Yucca schidigera and natural zeolite on broiler performance. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2004;3:651–654. [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Wang W., Yang C., Yang Y., Diana J., Yakupitiyage A., Luo Z., Li D. Application of microbial phytase in fish feed. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2007;40:497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal K.M., da S. Pires P.G., Ribeiro A.M.L.R. Growth promoter in broiler and pig production. Pubvet. 2020;14:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Cheng Y., Wang W., Wang A., Zhou Y. Protective effects of dietary supplementation with a silicate clay mineral (palygorskite) in lipopolysaccharide-challenged broiler chickens at an early age. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020;263:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Cheng Y., Yang W., Li X., Wen C., Wang W., Wang A., Zhou Y. An evaluation of palygorskite inclusion on the growth performance and digestive function of broilers. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016;129:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.P., Cheng Y.F., Li X.H., Zhang H., Yang W.L., Wen C., Zhou Y.M. Dietary palygorskite supplementation improves immunity, oxidative status, intestinal integrity, and barrier function of broilers at early age. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016;219:200–209. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.F., Chen Y.P., Li X.H., Yang W.L., Wen C., Zhou Y.M. Effects of palygorskite inclusion on the growth performance, meat quality, antioxidant ability, and mineral element content of broilers. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016;173:194–201. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0649-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.F., Chen Y.P., Wen C., Wang W.B., Wang A.Q., Zhou Y.M. Evaluation of dietary palygorskite supplementation on growth performance, mineral accumulations, antioxidant capacities, and meat quality of broilers fed lead-contaminated diet. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018;181:314–322. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-1047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corthésy B. Role of secretory IgA in infection and maintenance of homeostasis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2013;12:661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtui V.G. Effects of feeding a Fusarium poae extract and a natural zeolite to broiler chickens. Mycotoxin Res. 2000;16:43–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02946104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets V., Baaziz W., Ersen O., Gaigneaux E.M., Boissière C., Sanchez C., Debecker D.P. Hollow zeolite microspheres as a nest for enzymes: A new route to hybrid heterogeneous catalysts. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:954–961. doi: 10.1039/c9sc04615a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Nakagi V., Do Amaral C.M.C., Stech M.R., de Lima A.C.F., Harnich F.A.R., Laurentiz A.C., Pizauro Júnior J.M. Acid and alkaline phosphatase activity in broiler chicks fed with different levels of phytase and non-phytate phosphorus. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2013;41:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Dashtestani F., Ma'mani L., Jokar F., Maleki M., Fard M.Eskandari, Hosseini Salekdeh G. Zeolite-based nanocomposite as a smart pH-sensitive nanovehicle for release of xylanase as poultry feed supplement. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denli M., Blandon J.C., Guynot M.E., Salado S., Perez J.F. Effects of dietary AflaDetox on performance, serum biochemistry, histopathological changes, and aflatoxin residues in broilers exposed to aflatoxin B1. Poult. Sci. 2009;88:1444–1451. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dersjant-Li Y., Awati A., Schulze H., Partridge G. Phytase in non-ruminant animal nutrition: A critical review on phytase activities in the gastrointestinal tract and influencing factors. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015;95:878–896. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Anjos F.R., Ledoux D.R., Rottinghaus G.E., Chimonyo M. Efficacy of adsorbents (bentonite and diatomaceous earth) and turmeric (Curcuma longa) in alleviating the toxic effects of aflatoxin in chicks. Br. Poult. Sci. 2015;56:459–469. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2015.1053431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du M., Chen Y., Cheng Y., Wen C., Wang W., Wang A., Zhou Y. A comparison study on the effects of dietary conventional and ultra-fine ground palygorskite supplementation on the growth performance and digestive function of broiler chickens. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019;181:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dunislawska A., Biesek J., Banaszak M., Siwek M., Adamski M. Effect of zeolite supplementation on gene expression in the intestinal mucosa in the context of immunosafety support in poultry. Genes (Basel) 2022;13:1–14. doi: 10.3390/genes13050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durán N., Durán M., de Jesus M.B., Seabra A.B., Fávaro W.J., Nakazato G. Silver nanoparticles: A new view on mechanistic aspects on antimicrobial activity. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016;12:789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durna Aydin Ö., Yildiz G., Güntürkün O.B., Bayraktaroğlu A.G. The use of glauconite as a feed additive in broiler nutrition and its effect on growth performance, intestinal histomorphology and biomechanical properties of bones. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2020;26:343–349. [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseiny O.M., Abdallah A.G., Abdel-Latif K.O. The influence of biological feed additives on broiler performance. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2008;7:862–871. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira L., Fonseca A.M., Botelho G., Aguiar C.A., Neves I.C. Antimicrobial activity of faujasite zeolites doped with silver. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012;160:126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gadde U., Kim W.H., Oh S.T., Lillehoj H.S. Alternatives to antibiotics for maximizing growth performance and feed efficiency in poultry: A review. Anim. Heal. Res. Rev. 2017;18:26–45. doi: 10.1017/S1466252316000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall-David S.Le, Meuric V., Benzoni G., Valière S., Guyonvarch A., Minet J., Bonnaure-Mallet M., Barloy-Hubler F. Effect of zeolite on small intestine microbiota of broiler chickens: A case study. Food Nutr. Sci. 2017;8:163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly S., Dana K., Mukhopadhyay T.K., Parya T.K., Ghatak S. Organophilic nano clay: A comprehensive review. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 2011;70:189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazalah A.A., Abd-Elsamee M.O., Moustafa K.E.M.E., Khattab M.A., Rehan A.-E.A.A.A. Effect of nanosilica and bentonite as mycotoxins adsorbent agent in broiler chickens diet on growth performance and hepatic histopathology. Animals. 2021;11:1–10. doi: 10.3390/ani11072129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grądzki Z., Jarosz Ł., Stępień-Pyśniak D., Marek A. The effect of feed supplementation with Transcarpathian zeolite (clinoptilolite) on the concentrations of acute phase proteins and cytokines in the serum and hepatic tissue of chickens. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:2424–2437. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartati D.P., Santoso M., Qoniah I., Leaw W.L., Firda P.B.D., Nur H. A review on synthesis of kaolin-based zeolite and the effect of impurities. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2020;67:911–936. [Google Scholar]

- Hayanti S.Y., Hidayat C., Jayanegara A., Sholikin M.M., Rusdiana S., Widyaningrum Y., Masito M., Yusriani Y., Qomariyah N., Anggraeny Y.N. Effect of vitamin E supplementation on chicken sperm quality: A meta-analysis. Vet. World. 2022;15:419–426. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2022.419-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C.H., Qian Z.C., Song J., Luan Z.S., Zuo A.Y. Effects of zinc oxide-montmorillonite hybrid on growth performance, intestinal structure, and function of broiler chicken. Poult. Sci. 2013;92:143–150. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubadillah S.K., Othman M.H.D., Matsuura T., Ismail A.F., Rahman M.A., Harun Z., Jaafar J., Nomura M. Fabrications and applications of low cost ceramic membrane from kaolin: A comprehensive review. Ceram. Int. 2018;44:4538–4560. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard S. Hubbard SAS.; Quintin, France: 1999. Broiler Management Guide; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Indresh H., Devegowda G., Ruban S., Shivakumar M. Effects of high grade bentonite on performance, organ weights and serum biochemistry during aflatoxicosis in broilers. Vet. World. 2013;6:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Irawan A., Ningsih N., Rusli R.K., Suprayogi W.P.S., Akhirini N., Hadi R.F., Setyono W., Jayanegara A., Hafizuddin Supplementary n-3 fatty acids sources on performance and formation of omega-3 in egg of laying hens: A meta-analysis. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivkovic S., Deutsch U., Silberbach A., Walraph E., Mannel M. Dietary supplementation with the tribomechanically activated zeolite clinoptilolite in immunodeficiency: Effects on the immune system. Adv. Ther. 2004;21:135–147. doi: 10.1007/BF02850340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo E.J., Jung S.J., Son J.H., Cho J.K., Youn B.S., Youn K.T., Nam K.T., Hwang S.G. Effect of dietary supplement of fermented clay mineral on the growth performance and immune stimulation in broiler chickens. Korean J. Poult. Sci. 2007;34:231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Juzaitis-Boelter C.P., Benson A.P., Ahammad M.U., Jones M.K., Ferrel J., Davis A.J. Dietary inclusion of AZOMITE improves feed efficiency in broilers and egg production in laying and broiler breeder hens. Poult. Sci. 2021;100:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantar-Zadeh K., Shah A., Duong U., Hechter R.C., Dukkipati R., Kovesdy C.P. Kidney bone disease and mortality in CKD: Revisiting the role of vitamin D, calcimimetics, alkaline phosphatase, and minerals. Kidney Int. 2010;78:S10–S21. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamanlis X., Fortomaris P., Arsenos G., Dosis I., Papaioannou D., Batzios C., Kamarianos A. The effect of a natural zeolite (clinoptilolite) on the performance of broiler chickens and the quality of their litter. Asian-Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 2008;21:1642–1650. [Google Scholar]

- Kavan P.B., Shargh S.M., Hassani S., Mostafalo Effects of physical size of clinoptilolite on growth performance, serum biochemical parameters and litter quality of broiler chickens in the growing phase. Poult. Sci. J. 2013;1:93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Khanedar F., Vakili R., Zakizadeh S. Effects of two kinds of bentonite on the performance, blood biochemical parameters, carcass characteristics and tibia ash of broiler chicks. Glob. Vet. 2012;9:720–725. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-M., Lin C., Stavre Z., Greenblatt M.B., Shim J.-H. Osteoblast-osteoclast communication and bone homeostasis. Cells. 2020;9:1–14. doi: 10.3390/cells9092073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriseldi R., Johnson J.A., Walk C.L., Bedford M.R., Dozier W.A. Influence of exogenous phytase supplementation on phytate degradation, plasma inositol, alkaline phosphatase, and glucose concentrations of broilers at 28 days of age. Poult. Sci. 2021;100:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedynets M., Sprynskyy M., Sakhnyuk I., Zbytniewski R., Golembiewski R., Buszewski B. Adsorption of ammonium ions onto a natural zeolite: Transcarpathian clinoptilolite. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2004;22:731–741. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos M.J.de, Calixto L.F.L., dos S. Alves O., de Souza D.S., Moura B.B., Reis T.L. Kaolin in the diet and its effects on performance, litter moisture and intestinal morphology of broiler chickens. Ciência Rural. 2015;45:1835–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R.V. Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. J. Stat. Softw. 2016:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lim C.I., Park J.E., Kim S.E., Choe H.S., Ryu K.S. Effects of dietary silicate based complex mineral on performance, meat quality and immunological competence in broiler. Korean J. Poult. Sci. 2017;44:275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Li Z., Xu L., Xu X., Huang Q., Zeng Y., Wen M. The dynamics and adsorption of Cd (II) onto hydroxyapatite attapulgite composites from aqueous solution. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2018;87:269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Wang J.Q., Liu Z.Y., Wang Y.C., Wang J.P. Comparison of probiotics and clay detoxifier on the growth performance and enterotoxic markers of broilers fed diets contaminated with aflatoxin B1. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2018;27:341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Macháček M., Večerek V., Mas N., Suchý P., Straková E., Šerman V., Herzig I. effect of the feed additive clinoptilolite (ZeoFeed) on nutrient metabolism and production performance of laying hens. Acta Vet. Brno. 2010;79:S29–S34. [Google Scholar]

- Magnoli A.P., Monge M.P., Miazzo R.D., Cavaglieri L.R., Magnoli C.E., Merkis C.I., Cristofolini A.L., Dalcero A.M., Chiacchiera S.M. Effect of low levels of aflatoxin B1 on performance, biochemical parameters, and aflatoxin B1 in broiler liver tissues in the presence of monensin and sodium bentonite. Poult. Sci. 2011;90:48–58. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallek Z., Fendri I., Khannous L., Ben Hassena A., Traore A.I., Ayadi M.-A., Gdoura R. Effect of zeolite (clinoptilolite) as feed additive in Tunisian broilers on the total flora, meat texture and the production of omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria Cardinal K., Kipper M., Andretta I., Machado Leal Ribeiro A. Withdrawal of antibiotic growth promoters from broiler diets: Performance indexes and economic impact. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:6659–6667. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miazzo R., Peralta M.F., Magnoli C., Salvano M., Ferrero S., Chiacchiera S.M., Carvalho E.C.Q., Rosa C.A.R., Dalcero A. Efficacy of sodium bentonite as a detoxifier of broiler feed contaminated with aflatoxin and fumonisin. Poult. Sci. 2005;84:1–8. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles R.D., Henry P.R. Safety of improved Milbond-TX® when fed in broiler diets at greater than recommended levels. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2007;138:309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Miles R.D., Henry P.R. Safety of improved milbond-tx when fed in broiler diets limiting in available phosphorus or containing variable levels of metabolizable energy. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2007;16:412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Modirsanei M., Mansoori B., Khosravi A.R., Kiaei M.M., Khazraeinia P., Farkhoy M., Masoumi Z. Effect of diatomaceous earth on the performance and blood variables of broiler chicks during experimental aflatoxicosis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008;88:626–632. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi M. Bentonite clay as a natural remedy: A brief review. Iran. J. Public Health. 2017;46:1176–1183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadziakiewicz M., Lis M.W., Micek P. The effect of dietary halloysite supplementation on the performance of broiler chickens and broiler house environmental parameters. Animals. 2021;11:1–13. doi: 10.3390/ani11072040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadziakiewicz M., Micek P., Wojtysiak D. Effects of dietary halloysite supplementation on broiler chicken’s blood parameters, carcass and meat quality, and bone characteristics: A preliminary study. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2022;21 doi: 10.2478/aoas-2022-0037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadziakiewicza M., Kehoe S., Micek P. Physico-chemical properties of clay minerals and their use as a health promoting feed additive. Animals. 2019;9:1–15. doi: 10.3390/ani9100714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S., Schielzeth H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013;4:133–142. [Google Scholar]