Abstract

Introduction

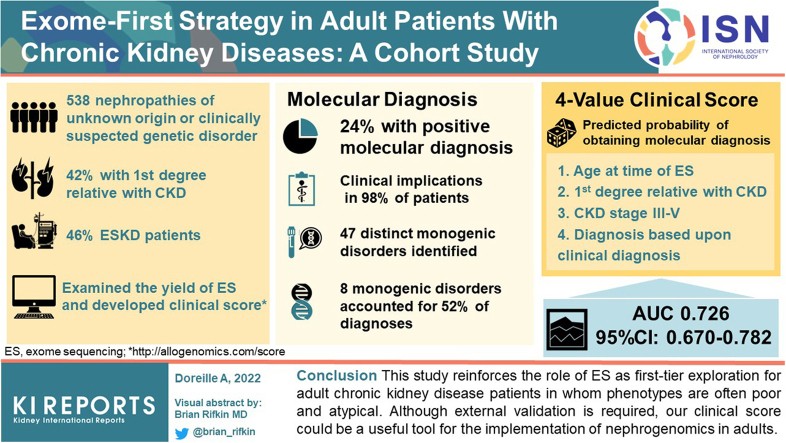

Exome sequencing (ES) has widened the field of nephrogenomics in adult nephrology. In addition to reporting the diagnostic yield of ES in an adult cohort study, we investigated the clinical implications of molecular diagnosis and developed a clinical score to predict the probability of obtaining positive result.

Methods

From September 2018 we have used ES to prospectively perform a first-tier liberal exploration of adult nephropathies of unknown origin and/or when a genetic kidney disease was clinically suggested. We also analyzed copy number variant using the same assay.

Results

Molecular diagnosis was made in 127 of 538 patients sequenced (diagnostic yield: 24%), comprising 47 distinct monogenic disorders. Eight of these monogenic disorders (17% [8/47]) accounted for 52% of genetic diagnoses. In 98% (n = 125/127) of the patients, the genetic information was reported to have major clinical implications. We developed a 4-value clinical score to predict the probability of obtaining a molecular diagnosis (area under the receiver operating characteristics curve [AUC] 0.726 [95% confidence interval: 0.670–0.782]) (available at http://allogenomics.com/score).

Conclusion

This study reinforces the role of ES as a first-tier exploration for adult chronic kidney disease patients in whom phenotypes are often poor and atypical. Although external validation is required, our clinical score could be a useful tool for the implementation of nephrogenomics in adults.

Keywords: CKD of unknown origin, exome sequencing, nephrogenomics

Graphical abstract

CKD affects approximately 700 million people worldwide and its prevalence is steadily growing.1 The proportion of patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) with family history vary worldwide, but up to 30% of ESKD patients report a family history.2,3 Yet, only 10% of adults with ESKD have their kidney disease ultimately confirmed as being of genetic origin.4 This suggests that a large number of genetic nephropathies might be currently undiagnosed in this population. Genetic investigations in nephrology have long been viewed as the prerogative of pediatricians or restricted to archetypal genetic nephropathies with highly penetrant variants affecting young adults.

The recent use of ES, has opened up new avenues to investigate nephropathies in adults.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 In a seminal retrospective study, the use of ES in a combined cohort of more than 3000 patients with CKD yielded a genetic diagnosis in 10% of cases, irrespective of age.5 The appropriate indications, clinical impact, and prospective diagnostic yield of ES in adult patients with a nephropathy have not yet been clearly investigated prospectively.

To address these issues, we report a cohort study of adult patients who underwent ES as a first-tier genetic test for investigation of early onset nephropathies of unknown origin, or because of clinical red flags suggesting a genetic kidney disease. We also investigated the clinical implications of a molecular diagnosis of kidney disease. We developed a clinical score to predict the probability of obtaining a molecular diagnosis to facilitate nephrogenomic implementation.

Methods

Study Population

This single-center, cohort study was performed in the setting of routine clinical care in an adult nephrology unit (Sorbonne University, Tenon Hospital, Paris, France).

ES has been routinely available in our center since September 2018. Nephrologists can offer ES in one or several of the following settings: (i) any patient with early onset CKD (<45 years old) of unknown cause despite full investigations; (ii) whenever a genetic etiology has been suspected on the basis of clinical red flags suggesting a genetic disease (multiorgan involvement, i.e., syndromic presentation, congenital anomalies, young age of onset of disease, consanguinity and family history of kidney disease); and (iii) when a related living donor transplantation has been planned to secure kidney graft donation. Local nephrogenomics referents (LM and AD) could assist the prescribing nephrologist in validating the indication of ES, although this remained at the sole prescriber’s discretion.

Typical autosomal dominant polycystic kidney diseases were excluded from the current indication for ES. If a genetic diagnosis was needed, a panel targeting genes involved in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney diseases was conducted first. Nevertheless, when atypical features were evidenced, or in the event of a negative test for PKD1 and PKD2, or on request from the patient or nephrologist, some patients initially labeled as potential “autosomal dominant polycystic kidney diseases” were eventually offered ES.

Clinical Data Collection

The referral nephrologist filled an ES order, specifying demographic and clinical data. These data were entered into a secure REDCap (https://www.project-redcap.org/)10 electronic data capture tool, hosted at the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale unit of Tenon Hospital. Data were prospectively recorded on the day of blood sample collection. Data were collected on initial clinical presentation, extrarenal features, kidney function, imaging characteristics, pathology results, and results of prior genetic investigations, if already performed. A detailed family history was also recorded, and an electronic family tree was generated.

After ES results were made available, the referral nephrologist had to complete a multiple-choice questionnaire about the clinical implications of the results from the following restricted list: “Clarification of the mode of inheritance,” “Screening of family members,” “Impact on therapeutic management,” “Rule out recurrence on graft,” “Order complementary exams (e.g., audiogram, ophthalmologist…),” “Rule out several diagnoses,” “Help in the selection of related potential kidney donor,” “No clinical implication.”

ES, Variant Analysis and Final Exome Report

Genomic DNA was isolated from blood samples, exons (37 megabases) were captured with the Twist Human Core Exome kit, sequenced on Illumina platforms, and analyzed using dedicated software (SeqOne, Montpellier, France). Variant segregation was explored using targeted approaches in relatives. Copy number variant analysis was performed from exome assay and based on GATK4.11 All the coding regions of the genome (RefSeq exons) were sequenced. The technique used made it possible to proceed as follows: from 50 ng of fragmented DNA, indexed libraries were prepared and hybridized with biotinylated Twist Human Exome probes (37 Mb). The samples were prepared according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The library pools (multiplexed by 36 samples) were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 2000 sequencer in paired-end mode (2 × 150 bp) on a FlowCell P3. The raw data (file in bcl format) were converted to fastq format using the Dragen software installed on the sequencer (Illumina, Mumbai, Maharashtra). The variants were filtered according to their level of coverage (DP >10), their frequencies in GnomAD (<1%), their allelic frequency (>20%), according to their effect on the protein, according to their deleterious character or not according to Clinvar and Human Gene Mutation Database (in the versions available on the date of the analysis), and according to the compatibility of the phenotype and the mode of inheritance. Data were interpreted according to the clinical context mentioned by the clinician. Depending on the clinical context, different in silico panel could be applied, customized panel included genes of Groopman et al.5 publication implemented with new genes described in literature related to nephrology since then.

All patients’ sequencing data were discussed during a weekly multidisciplinary genome board meeting, which included at least 1 laboratory geneticist (LR and/or MD) and a nephrologist with a special interest in nephrogenomics (LM) and, whenever possible, the attending nephrologist who ordered the ES for the patient under discussion. This exome data discussion meeting resulted in the following: either (i) a final exome report indicating a “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” variant according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines12 explicative of the patient’s phenotype, or (ii) instructions for cosegregation and/or retrophenotyping when variants of unknown significance (VUS) possibly connected to the kidney phenotype were encountered. In the latter case, an additional genome board meeting was conducted to complete the final exome report with respect to cosegregation and retrophenotyping data. If ACMG medically actionable genes were found (even though they were not actively sought after), the result was returned to the patient if he/she had agreed to it during the pretest appointment, and after a multidisciplinary meeting evaluating a benefit for the patient to be aware of this incidental finding. The turnaround time from blood sample collection to genetic report was estimated at 8 weeks, except in emergency situations for which turnaround could be reduced to 3 weeks.

Cosegregation Studies

Whenever possible, ES was sequenced in trio (proband and both parents) or duo (proband and one sibling or parent). When relatives were initially not available and if cosegregation was needed to reach a conclusion on a VUS, probands were asked to contact their relatives to offer them a medical appointment with one of our nephrologists. During this appointment, clinical and biological data were collected. After clear information regarding its implication, targeted Sanger sequencing of the VUS was offered. Cosegregation was also used for the screening of the patient’s family members with a molecular diagnosis. Cosegregation was explored by targeted Sanger sequencing, and copy number variants were validated using an orthogonal method.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the diagnostic yield on the basis of the number of variants classified as “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” in the study population. We assessed the interaction between diagnostic yield and exome type (single, duo, or trio) using a χ2 test.

For regression studies, we first performed a univariate logistic regression examining the association between obtaining a molecular diagnosis by ES (“yes” vs. “no”) and all clinically relevant variables available at the time of sample collection with a rate of missing data <15%. Second, a multivariate model was built using these variables. Variable selection was performed using stepwise backward elimination. Because of a significant interaction between patient’s age and CKD stage at the time of ES, an interaction term was used in regression analyses.

We derived a predictive score based on this model’s β-coefficients. We assessed its discriminative ability using the AUC in the derivation cohort. We computed the AUC confidence interval using bootstrap (ci.auc function of the pROC package, 2000 replicates). We assessed its calibration using a calibration plot and a visual evaluation. We assessed variable importance using the absolute value of the t-statistic for each model parameter (varImp function of the caret package).

All tests were 2-sided and a P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using R Statistical Software version 4.0.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Cohort Characteristics and Patient Selection

From September 2018 to February 2021, 538 unrelated index cases underwent ES to explore their nephropathy. Patients’ baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ baseline characteristics and exome sequencing prescription data

| Variable | Missing | Study population (N = 538) | Missing | Patients with a genetic diagnosis (N = 127) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age–years (mean ± SD) | 42.6 (SD 13.3) | 39.8 (SD 13.2) | ||

| Female sex–no. (%) | 206 (38.3) | 53 (41.7) | ||

| Race or ethnic group–no. (%) | ||||

| White European | 169 (31.4) | 50 (39.4) | ||

| African ancestry | 177 (32.9) | 25 (19.7) | ||

| North African | 109 (20.3) | 39 (30.7) | ||

| Other/Unspecified | 83 (15.4) | 13 (10.2) | ||

| Consanguinity–no. (%) | 8 | 64 (12.1) | 2 | 23 (18.4) |

| First-degree family history of CKD–no. (%) | 7 | 200 (37.7) | 1 | 71 (56.3) |

| End-stage Kidney disease–no. (%) | 247 (45.9) | 55 (43.3) | ||

| Genetic test before ES–no. (%) | 5 | 66 (12.4) | 2 | 19 (15.2) |

| Patient with kidney biopsy – no. (%) | 13 | 187 (35.6) | 5 | 40 (32.8) |

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | 108 (57.8) | 22 (55) | ||

| Vascular lesions | 53 (28.3) | 11 (27.5) | ||

| Tubulo-interstitial lesions | 37 (19.8) | 13 (32.5) | ||

| Thrombotic microangiopathy | 32 (17.1) | 6 (15) | ||

| Immune deposits | 12 (6.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| IgA nephropathy | 8 (4.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Thin basement membrane abnormality | 8 (4.3) | 2 (5) | ||

| Factor motivating the ES–no. (%) | ||||

| Young age leading to CKD | 255 (47.4) | 69 (54.3) | ||

| First-degree family history of CKD | 128 (23.8) | 46 (36.2) | ||

| Undiagnosed origin of the CKD | 344 (63.9) | 77 (60.6) | ||

| Kidney biopsy not informative | 49 (9.1) | 13 (10.2) | ||

| Kidney biopsy not possible | 76 (14.1) | 14 (11) | ||

| To avoid kidney biopsy first | 82 (15) | 23 (17) | ||

| Related living donation planned | 15 (2.8) | 4 (3.1) | ||

| ES type– no. (%) | ||||

| Exome solo | 451 (84) | 105 (83) | ||

| Exome duo | 52 (10) | 13 (10) | ||

| Exome trio | 35 (7) | 9 (7) |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; ES, exome sequencing.

Mean age was 43 years (standard deviation: 13 years), and 38% of patients were women. Self-declared ethnic ancestry was 31% White European, 33% African (including French Indies), 20% North African, and 15% other. Consanguinity was found in 12% of cases. A first-degree family history of CKD was found in 42% of cases. A total of 46% of the patients had ESKD. Only 12% of patients had received a previous negative genetic test before ES (type of genetic testing detailed in Supplementary Table S1). A kidney biopsy was performed in 187 patients (35.6%). Main pathologic lesions reported were focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (n = 108, 57.8%), vascular lesions (n = 53, 28.3%), tubulo-interstitial lesions (n = 37, 19.8%) and thrombotic microangiopathy (n = 32, 17.1%).

Factors prompting ES are detailed in Table 1. Main factors were undiagnosed origin of the CKD (n = 344, 63.9%) and young age leading to CKD (n = 255, 47.4%). In 125 cases (23.2%), biopsy was either not informative or not possible. In 148 cases (27.5%), ES was performed early on to potentially avoid a kidney biopsy (details of clinical situations in Supplementary Table S2). Rarely (n = 15, 2.8%), ES was performed in the context of a planned related living donor transplantation, to secure the donation.

Genetic Findings and Diagnostic Yield in the Overall Cohort

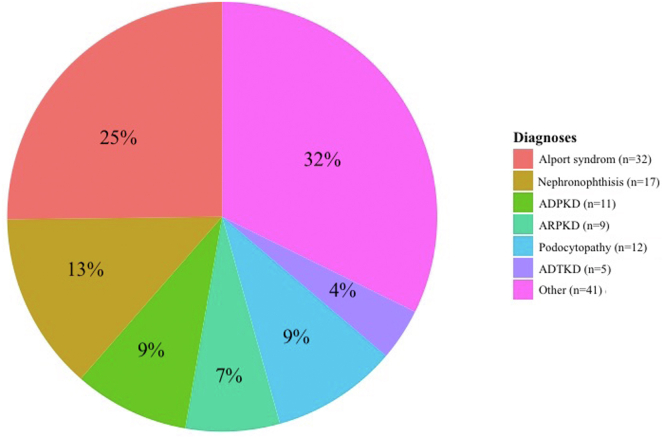

We detected diagnostic variants in 127 of 538 patients (24%), of which 7 diagnostic variants were detected by copy number variant analysis (6% of diagnoses). Genetic findings are detailed in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S3.

Figure 1.

Genetic diagnosis. ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; ADTKD, autosomal dominant tubulo-interstitial kidney disease; ARPKD, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease.

These 127 genetic diagnoses accounted for 47 distinct monogenic disorders. Eight molecular disorders collectively accounted for 52% of diagnoses as follows: ciliopathies because of mutations in PKD1 (n = 7, 6%), PKHD1 (n = 9, 7%) or TTC21B (n = 8, 6%); nephropathies because of mutations in COL4A3 (n = 7, 6%), COL4A4 (n = 14, 11%) or COL4A5 (n = 11, 9%); autosomal dominant tubulo-interstitial kidney disease because of mutation in ADTKD-UMOD (n = 5, 4%); and CKD secondary to PAX2 mutation (n = 5, 4%). Yet, of the 47 distinct monogenic disorders, 22 had only 1 recurrence in the cohort (i.e., 47% of identified monogenic disorders were unique). A total of 46% of patients had an autosomal dominant disease, 43% had an autosomal recessive disease, and 11% had an X-linked disease.

A total of 44 VUS+ (i.e., variants estimated to lie close to the border between uncertain significance and likely pathogenic) related to the phenotype were identified but could not be returned to the patient (Supplementary Table S4). A significant number of COL4A3 heterozygous variants (NM_000091.4 c.3829G>Ap.G1277S and NM_000091.4: c.4510T>C, p.Phe1504Leu) ranked previously as class 4 ACMG variants, have been reclassified as VUS given the frequencies observed in our internal cohort and accumulation of cosegregation data in different unrelated pedigrees.

ApoL1 risk alleles (G1/G2, G1/G1, or G2/G2) were found in 56 patients (10%). Among them, 3 patients also had a Mendelian diagnostic variant which explained their nephropathy.

Two patients had BRCA1 or BRCA2 variants, recommended for return of incidental findings in clinical sequencing in accordance with the ACMG policy and local review by multidisciplinary meeting from Sorbonne University.13 Three patients presented a G6PD variation, and 9 others had heterozygous CFTR variations.

Three patients had dual molecular diagnosis, thereby providing insights on extrarenal symptoms. Patient 112 was heterozygous for an OTOF pathogenic variant shedding light on her familial dominant deafness. Patient 323 was heterozygous for ACTA2 pathogenic variant, establishing a genetic basis for the occurrence of aortic dissection when he was 30 years old. Patient 364 is heterozygous for a PLIN1 likely pathogenic variant consistent with the lipodystrophy she exhibited.

Exome Solo and Cosegregation Study, Impact of Trio Analysis

A total of 84% of our ES was sequenced in solo (i.e., proband only; Table 1). There was no significant difference (P = 0.92) in the diagnostic yield whether the exome was initially performed in solo (i.e., proband only; 105/451, yield 23%), in duo (i.e., proband and a parent or sibling; 13/52, yield 25%) or in trio (i.e., proband and 2 parents or siblings, 9/35; yield 26%).

A total of 116 patients (21%) necessitated ancillary cosegregation analysis to establish conclusive genetic reporting. At baseline with no additional cosegregation data, the diagnostic yield of ES in trio (9/35; yield 26%) was significantly greater compared with duo (9/52, yield 17%) and solo (67/451; yield 15%). Indeed, these 116 ancillary cosegregation analyses enabled 42 additional diagnoses either by upgrading a VUS to likely pathogenic, or by confirming that 2 variants were in trans position for recessive diseases determining heterozygote compound variants.

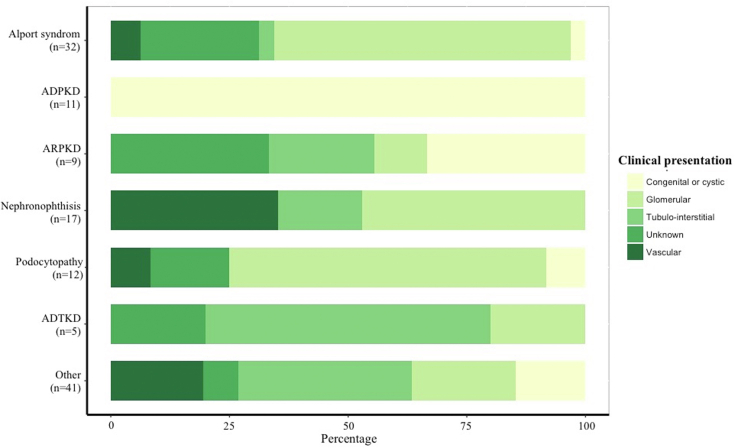

Genotype-Phenotype Correlation

As depicted in Figure 2, initial presentation in many cases did not match the expected clinical presentation linked to the genetic disorder. For example, in the 32 patients who had a diagnostic finding consistent with a nephropathy associated with COL4A3, COL4A4, or COL4A5, broad clinical patterns were disclosed. At the time of sample collection, 20 of these patients were initially considered by the referral nephrologist as having a glomerular disease, 8 were categorized as kidney disease of unknown origin, 2 as vascular kidney disease, 1 as congenital or cystic kidney disease, and 1 as tubulo-interstitial kidney disease.

Figure 2.

Genetic diagnoses and clinical presentation. ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; ADTKD, autosomal dominant tubulo-interstitial kidney disease; ARPKD, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease.

Clinical Implication

The clinical impact of genetic information provided by ES for patients with a final molecular diagnosis is detailed in Table 2. For these patients, the referral nephrologist reported an impact in all but 2 patients (98%). In most cases, ES results allowed for a diagnosis of the nephropathy or ruled out several diagnoses suspected on a clinical basis. Molecular diagnosis could also guide family testing and counseling, initiate referral for subspecialty care (e.g., audiometry, ophthalmologic review, cerebral magnetic resonance imaging), influence choice of therapy, or assist with kidney donor selection. Even when no diagnostic variants were found, ES had a clinical impact in some cases by influencing the therapy (n = 16, 4%), ruling out several diagnoses (n = 62, 15%), and leading to other consequences not specified (n = 80, 19%).

Table 2.

Clinical implications among patients with genetic diagnosis

| Patients with genetic diagnosis (N =127) | |

|---|---|

| Clinical implications of genetic information–no. (%) | 125 (98) |

| Clarification of mode of inheritance | 99 (78) |

| Screening of family members | 81 (64) |

| Influence therapy | 16 (13) |

| Rule out recurrence on graft | 25 (20) |

| Order complementary exams (e.g., audiogram, ophthalmologist) | 45 (35) |

| Rule out several diagnoses | 23 (18) |

| Help in the selection of related potential kidney donor | 10 (8) |

Factors Associated With Obtaining a Molecular Diagnosis

In multivariate logistic regression (Table 3), we identified 3 factors, prospectively collected at the time of sample collection, which were independently and significantly associated with obtaining a molecular diagnosis as follows: (i) patient’s age at the time of ES, (ii) a first-degree family history of CKD, and (iii) the current diagnosis on the basis of clinical presentation.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression estimating the probability of obtaining a molecular diagnosis

| General data | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | P-value | OR [95% CI] | P-value | |

| Female sex | 1.213 [0.792–1.851] | 0.371 | ||

| Consanguinity | 1.910 [1.059–3.366] | 0.027 | ||

| First-degree history of kidney disease | 2.939 [1.920–4.530] | <0.001 | 3.844 [2.398–6.249] | <0.001 |

| Previous genetic test | 1.333 [0.712–2.397] | 0.351 | ||

| Previous kidney biopsy | 0.811 [0.517–1.256] | 0.353 | ||

| Urinary reflux | 0.948 [0.140–3.988] | 0.948 | ||

| Extrarenal features | 1.663 [1.079–2.555] | 0.020 | ||

| Age at the time of ES (per 1-year increase) | ||||

| If CKD stage I or II | 0.971 [0.948–0.992] | 0.010 | 0.949 [0.924–0.973] | <0.001 |

| If CKD stage III, IV, or V | 0.976 [0.960–0.992] | 0.004 | 0.960 [0.942–0.977] | <0.001 |

| Current diagnosis on the basis of clinical presentation | ||||

| Vascular disease | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Glomerular disease | 1.646 [0.818–3.553] | 0.180 | 1.489 [0.708–3.333] | 0.310 |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 2.536 [1.155–5.844] | 0.023 | 2.461 [1.072–5.908] | 0.037 |

| Undiagnosed/isolated hematuria or proteinuria/other disease | 1.711 [0.790–3.890] | 0.182 | 1.476 [0.660–3.446] | 0.352 |

| Developmental disorders/nonclassic cystic disease | 6.174 [2.660–15.106] | <0.001 | 5.772 [2.362–14.811] | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; OR, odds ratio.

Derivation and Validation of a Clinical Score to Predict the Probability of Obtaining a Molecular Diagnosis

Using the β-coefficients from this multivariate model, we derived a score to predict the probability of obtaining a diagnosis (Table 4). In internal validation (Supplementary Figure S1), AUC was 0.726 (95% confidence interval: 0.670–0.782, determined using 2000 bootstrap replicates), and calibration plots demonstrated a good agreement between predicted probabilities and observed proportions across deciles of score values. First-degree family history of CKD and age at the time of ES were the 2 most important factors to predict ES results (Supplementary Figure S2). A score’s threshold of −2.230916 offers a negative predictive value of 94.2%, a sensitivity of 95.6%, and a positive predictive value of 26.8% (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). An online calculator is available at http://allogenomics.com/score.

Table 4.

Clinical score predicting the probability of obtaining a diagnosis

| Variable | β-coefficient |

|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.622792 |

| Age (in years) | |

| If current CKD stage I or II | −0.052247 |

| If current CKD stage III, IV, or V | −0.041056 |

| First-degree history of kidney disease | 1.346556 |

| Current diagnosis on the basis of clinical presentation | |

| Vascular disease | 0 |

| Glomerular disease | 0.398665 |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 0.900757 |

| Undiagnosed/isolated hematuria or proteinuria/other disease | 0.389117 |

| Developmental disorders/nonclassic cystic disease | 1.753048 |

For a given patient, score value is equal to the sum of each predictor (β-coefficients x variable) + intercept. Estimated probability is then equal to 1/(1+e-score).

For instance, for a 23-year-old patient with a CKD stage III, with no first-degree history of kidney disease, presenting with a tubulo-interstitial disease, the score value is: −0.622792 + 23 x (−0.041056) + 0.900757 = −0.666323. The probability of obtaining a diagnosis is then equal to 1/(1+e−(−0.666323)) = 33.9%.

Discussion

In this cohort study, first-tier ES with broadened indications in adult patients with kidney diseases demonstrated a diagnostic yield of 24%. In most cases (98%), ES results translated to meaningful clinical implications.

Our findings emphasize the high degree of genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of adult genetic nephropathies. Importantly, the diseases diagnosed by ES were sometimes unexpected. This cannot be explained by misclassification, because each diagnosis is considered to be responsible for a patient’s phenotype, using standard criteria.12 These data support pangenomic sequencing, which assesses genes that otherwise may have gone unevaluated, as a first-tier test in this population. Still, some centers prefer more phenotypically-driven testing (gene panel) as a first-tier test over pangenomic investigations.14 This “phenotype to genotype” strategy often requires a meticulous collection of renal and extrarenal manifestations, histopathological evaluation of the involved tissues, and several biochemical tests before the genetic test is ordered. According to these results (the “phenotype”), candidate genes are sequenced for disease confirmation. Conversely, our strategy could be summarized as “phenotype to genotype to phenotype.” This designation is because clinical and genetic evaluations are conducted in parallel, with a clinical re-evaluation in the light of genetic sequencing results, to confirm or rule out the diagnosis indicated by the genetic test. The successful diagnosis in phenotype-driven genetic testing is highly dependent on the clinical supposition of the nephrologist. This generates an indication bias by selecting patients with a complete, typical phenotype for genetic testing, eliminating less-penetrant, variable phenotypes. Therefore, many genetic nephropathies may be left undiagnosed or even ultimately end up not receiving genetic testing, especially if patients display an incomplete or atypical phenotype. Moreover, phenotype-driven approaches and targeted genes panel-sequencing strategies do not seem to be cost-efficient. Indeed, in 2021 in France, the panel approach was not justified by its cost. In our institution, an ES costs the same as a large targeted genes panel. When a targeted genes panel yields no pathogenic variation, a second panel might be prescribed sequentially, resulting in further expense and supplementary diagnostic delays. In contrast, ES allows periodic reappraisal of its findings, whereas a gene panel becomes obsolete once a new phenotype-linked gene is described. ES with in silico gene panel analysis represents yet another worthy approach currently promoted by the panel-app consortium from Genomic England.

We derived and internally validated an easy-to-use predictive score that demonstrated a “good” discriminative performance (AUC > 0.70) and satisfactory calibration. We provide an online calculator for this score (http://allogenomics.com/score). The use of a high-sensitivity threshold could help prioritize ES prescriptions and foster nephrogenomic implementation in adult patient populations. Below such a threshold, one could safely rule out the need for ES for patients with a high probability of “negative” results (e.g., 94.2% probability of negative results if the score is inferior to −2.230916). For instance, for a 50-year-old patient with CKD stage I, a current diagnosis of vascular disease and no first-degree history of CKD, the probability of positive ES is the lowest. Importantly, in our cohort, some of these patients, with an a priori low probability of obtaining a molecular diagnosis, were still diagnosed with a genetic disease. The choice of criteria selected to perform ES should be determined on a local basis, weighing resources against the expected diagnostic yield (i.e., the lower the threshold, the higher both the costs and the diagnostic yield). It is important to note that, because of the lack of external validation, our score should be used with caution to guide clinical decisions, although internal recalibration may facilitate its application in other settings.

In most cases, ES was analyzed in solo. Family member screening was necessary to achieve a final molecular diagnosis in 21% of the cases. Indeed, cosegregation is part of the criteria of ACMG pathogenicity classification guidelines because it allows for a potential VUS to be ranked down in case of nonsegregation (BS4) and reciprocally ranked up in case of cosegregation of de novo variation (PP1, PS2, PS4). Moreover, for a recessive disease for which heterozygote compound variants are suspected, confirmation of their trans position allows confirmation of a potential recessive disease (PM3). Cosegregation studies are time consuming and resource intensive but are sometimes essential to assess the pathogenicity of a variant.15 Given their privileged relationship to the patient, the referring nephrologist can act as a key facilitator of cosegregation studies. In turn, this highlights the need to empower nephrologists, both by educating and involving them in the genomic process.16

In this cohort, a new variant of nephronophthisis has been described. Indeed, thanks to GeneMatcher,17 we discovered a patient displaying the same variant and phenotype in the Netherlands. An ensuing cooperative exchange between centers, along with experimental and functional studies resulted in the description of the TMEM72 variation, which is responsible for a nephronophthisis-like phenotype.18 In its unbiased observation of genetic variants, ES generates the description of new genetic variants and contributes to the growth of the genetic thesaurus, and the description of new pathophysiological mechanisms.

An additional benefit of extended genetic testing is that it may potentially enrich the phenotypic description of a disease related to a given gene. Until recently, nephronophthisis had not been documented as a likely cause of thrombotic microangiopathy. What may have appeared at first glance as a coincidental diagnosis emerged as a possible cause of thrombotic microangiopathy, thereby expanding the phenotypic description of nephronophthisis and ushering in a new vascular phenotype, termed “nephroangionophthisis.”19

Most broad spectrum genetic examination prescription, at least in France, must be passed by a validation committee composed of geneticists, molecular biologists and clinician nephrogenetic experts, to oversee and arbitrate indications of genomic investigations. In contrast, our approach is heavily reliant on the sole attending clinician and their ability to judge when a genetic test is thought to be relevant. However, there is emphasis on close interactions between clinicians and biologists to discussions the sequencing results. A key advantage of this liberalized approach to genomic indications is to reduce constraints associated with genetic analysis. In this study, this strategy proved successful for 2 reasons. First, a significant number of patients received genetic testing (538 in 2.5 years), with limited constraints for the referring nephrologist. Second, in numerous cases, irrespective of a positive or negative result, there were clear and objective benefits for both the patients and their relatives, on the basis of prospectively collected data pertaining to the clinical implications of ES results. In our opinion, to increase patient’s access to genomic testing and its benefits, prescription cannot be the exclusive prerogative of a few experts. We strongly advocate a more flexible approach such as ours, whereby guidelines are provided to clinicians but prescription is unrestrained, and according to which geneticists, molecular biologists, and clinicians collaborate to interpret genetic results. Importantly, genetic testing entails ethical and technical considerations, which should be part of the nephrology curriculum.

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not define a priori objective criteria for ES prescription. Instead, these data reflect real-life practice, where indications for genomic explorations were ultimately left to the discretion of the clinician. Second, pangenomic investigations have challenges of their own, because they may give rise to VUS for which handling is notoriously complex. However, in some cases, we were able to reclassify those VUS (as either likely benign or pathogenic) by additional cosegregation studies and reverse phenotyping in probands, with ensuing clinical implications. Third, this was a single-center study and so its generalization may be questioned. Nevertheless, our results are in accordance with results from other studies, and examples of the input of ES in adult nephrology are growing around the world.5, 6, 7, 8,20,21 Importantly, because of our “liberal” prescription criteria, our study sample can be considered as representative of the eligible population (i.e., patients cared for in our center who were <45 years old with a CKD of unknown cause, or where there was clinical suspicion for a genetic cause). Our center is one of the largest nephrology units in a public hospital in France, which unrestrictedly treats patients with acute and chronic kidney conditions in our geographic region (north-eastern Paris and suburbs). Consequently, our study can be considered as population-based because it covers residents from our area.22 However, despite being referred patients by several hospitals in our locality, our single-center setting prevents a conclusion as to whether our findings are fully transposable to patients from other geographic areas. To this end, we provide detailed baseline characteristics to enable comparison between patients from our center and those from other centers. Furthermore, to study whether our score can be extrapolated to other clinical contexts, a multicentric validation cohort is currently being planned.

With a positive diagnostic yield of 24% and a major clinical impact, our data from a cohort study support liberalization of ES explorations in adult nephrology. We derived and internally validated an easy-to-use clinical score, which reliably estimates the pretest probability of positive results and could help prioritize prescription, especially in settings with limited resources.

Disclosure

EL has consulted for Biocodex company and received compensation. CR declares travel grants from Sanofi and Alexion and speaker honoraria from Alexion. ER declares to have received fundings for research support, personal fees and compensation as a member of the scientific advisory board of Alexion Pharmaceutical. LM declares lecture fees with Travere Pharmaceutical and travels grant with Sanofi France Pharma. All the other authors have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Felicity Kay for her careful English editing. The authors want to thanks all the nephrologists who actively participate in exome sequencing prescription.

Funding

Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris paid for the genetic explorations in context of standard care. No external funding for this study.

Ethics

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients regarding de-identified clinical and personal patient data collection, analysis, and publication. The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board (Direction de la Recherche Clinique et de l’Innovation (APHP220461)) and the Ethic board of Sorbonne Université (CER-2022-009).

Collaborators

Dany Anglicheau, Nadia Arzouk, Benoit Barrou, Xavier Belenfant, Nicolas Benichou, Romain Brousse, Maren Burbach, Aymeric Couturier, Karine Dahan, Mathilde Dargelos, Michel Delahousse, Adrien Flahaut, Marion Gauthier, Guillaume Hanouna, Alexandre Hertig, Sebastien Homs, Corinne Isnard Bagnis, Alexandre Karras, Rateb Khayat, Thomas Kofman, Alexandre Lahens, Marie Matignon, Olivia May, Inna Mohamadou, Camille Saint Jacques, Eric Thervet, Isabelle Tostivint, Alexis Werion.

Footnotes

Figure S1. Receiver operating characteristics curve (a) and calibration plot (b) for the predictive score.

Figure S2. Variable importance analysis for the multivariate model.

Table S1. Type of genetic test ordered prior to exome sequencing (n = 66).

Table S2. Clinical context of ES performed to avoid kidney biopsy (n = 82).

Table S3. Details of genetic findings in the cohort (ACMG class 4 and 5 variants).

Table S4. Details of variants of unknown significance + (ACMG class 3+).

Table S5. Sensitivities and specificities at various thresholds for the clinical score.

Table S6. Contingency table for a score’s threshold of −2.230916.

STROBE Statement.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Receiver operating characteristics curve (a) and calibration plot (b) for the predictive score.

Figure S2. Variable importance analysis for the multivariate model

Table S1. Type of genetic test ordered prior to exome sequencing (n = 66).

Table S2. Clinical context of ES performed to avoid kidney biopsy (n = 82).

Table S3. Details of genetic findings in the cohort (ACMG class 4 and 5 variants).

Table S4. Details of variants of unknown significance + (ACMG class 3+).

Table S5. Sensitivities and specificities at various thresholds for the clinical score.

Table S6. Contingency table for a score’s threshold of −2.230916.

STROBE Statement.

References

- 1.GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (Lond Engl) 2020;395:709–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClellan W.M., Satko S.G., Gladstone E., et al. Individuals with a family history of ESRD are a high-risk population for CKD: implications for targeted surveillance and intervention activities. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(Suppl 3):S100–S106. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connaughton D.M., Bukhari S., Conlon P., et al. The Irish Kidney gene project--prevalence of family history in patients with kidney disease in Ireland. Nephron. 2015;130:293–301. doi: 10.1159/000436983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wühl E., van Stralen K.J., Wanner C., et al. Renal replacement therapy for rare diseases affecting the kidney: an analysis of the ERA-EDTA Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(Suppl 4) doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groopman E.E., Marasa M., Cameron-Christie S., et al. Diagnostic utility of exome sequencing for kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:142–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann N., Braun D.A., Amann K., et al. Whole-exome sequencing enables a precision medicine approach for kidney transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:201–215. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018060575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landini S., Mazzinghi B., Becherucci F., et al. Reverse phenotyping after whole-exome sequencing in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:89–100. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06060519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaisitti T., Sorbini M., Callegari M., et al. Clinical exome sequencing is a powerful tool in the diagnostic flow of monogenic kidney diseases: an Italian experience. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1767–1781. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00898-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jayasinghe K., Stark Z., Kerr P.G., et al. Clinical impact of genomic testing in patients with suspected monogenic kidney disease. Genet Med. 2021;23:183–191. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-00963-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Testard Q., Vanhoye X., Yauy K., et al. Exome sequencing as a first-tier test for copy number variant detection: retrospective evaluation and prospective screening in 2418 cases. J Med Genet. 2022;59:1234–1240. doi: 10.1136/jmg-2022-108439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M.M., Datto M., Duncavage E.J., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of sequence variants in cancer: a joint consensus recommendation of the association for molecular pathology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn. 2017;19:4–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green R., Berg J., Grody W., et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joly D., Béroud C., Grünfeld J.P. Rare inherited disorders with renal involvement-approach to the patient. Kidney Int. 2015;87:901–908. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nestor J.G., Marasa M., Milo-Rasouly H., et al. Pilot study of return of genetic results to patients in adult nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:651–664. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12481019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doreille A., Villié P., Mesnard L. National survey on genetic test prescription in French adult nephrologists: a call for simplification and education. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:1213–1215. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfac041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GeneMatcher (GM) https://genematcher.org/

- 18.Snoek R., Claus L., Peters E.D.J., et al. European Society of Human Genetics Conference; 2021. Biallelic TMEM72 variants in patients with nephronophthisis-like phenotype.https://2021.eshg.org/programme/tuesday-august-31-virtual-conference/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doreille A., Raymond L., Lebre A.S., et al. Nephronophthisis in young adults phenocopying thrombotic microangiopathy and severe nephrosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16:615–617. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11890720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riedhammer K.M., Braunisch M.C., Günthner R., et al. Exome sequencing and identification of phenocopies in patients with clinically presumed hereditary nephropathies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:460–470. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Ven A.T., Connaughton D.M., Ityel H., et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies causative mutations in families with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:2348–2361. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017121265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szklo M. Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiol Rev. 1998;20:81–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.