Abstract

Objective

Here we compare the procedural and clinical outcome of patients undergoing thrombectomy with running thrombolysis to matched controls with completed intravenous therapy and an only marginally overlapping activity.

Methods

Patients from 25 sites in Germany were included, who presented with an acute ischemic stroke. Patients’ baseline characteristics (including ASPECTS, NIHSS and mRS), grade of reperfusion, and functional outcome 24 h and at day 90 after intervention were extracted from the German Stroke Registry (n = 2566). In a case-control design we stepwise matched the groups due to age, sex and time to groin puncture and time to flow restoration.

Results

In the initial cohort (overlap group n = 864, control group n = 1702) reperfusion status (median TICI in overlap group vs. control group: 3 vs. 2b), NIHSS after 24 h, early neurological improvement parameters, mRS at 24 h and at day 90 were significantly better in the overlap group (p < 0.001) with a similar risk of bleeding (2.9% vs. 2.4%) and death (18% vs. 22%). After adjustment mRS at day 90 still showed a trend for lower disability scores in the overlap group (3 IQR 1-5 vs. 3 IQR 1-6, p = 0.09). While comparable bleeding risk could be maintained (4% in both groups), there were significantly more deaths in the control group (18% vs. 30%, p = 0.006).

Conclusion

The presented results support the approach of continuing and completing a simultaneous administration of intravenous thrombolysis during mechanical thrombectomy procedures.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, Alteplase, Brain infarction, Anterior circulation, Brain revascularization

Introduction

For a long time, intravenous administration of alteplase was considered the only proven treatment option for large vessel occlusion (LVO) within a time window of 4.5 h from symptom onset [1]. Intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) was standard of care until five randomized clinical trials proved the superiority of a treatment strategy combining mechanical thrombectomy (MT) and IVT [2–6]. Recent investigations revealed an early recanalization rate after sole alteplase administration for treatment of LVO in 41% with a good clinical outcome in only 29% [7]. Hence, until today the combinatorial approach of alteplase administration and mechanical thrombectomy is still the standard of care in ischemic stroke treatment.

Although there is a plentitude of data on the efficacy of MT and IVT reflected in national and international treatment guidelines, the temporal treatment workflow is still a point of discussion [8, 9]. Neurointerventionalists’ heterogeneous approaches in time management of IVT and MT in LVO were revealed in a national survey covering 107 treatment sites in Germany [10]. Even if the majority of participants reported to continue IVT after initiation of MT, there was a considerable number of clinicians who generally stop IVT either before or after MT or they decide on a case by case basis. After successful recanalization, most neurointerventionalists report to continue with IVT on a case dependent basis, e.g. thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) grade [10]; however, a certain minority exists, who do not continue IVT mostly because of a fear of increasing the risk of intracranial hemorrhage. These findings mirror a certain insecurity in coordination of IVT and MT in acute ischemic stroke treatment and are indicative of a missing strategy in cases of potential time overlap. In the past, the safety of a running IVT administration during MT using a stent retriever has been shown descriptively; however, there are still no comparative data to enable drawing conclusions with respect to continuing or termination of IVT before MT [11]. Additionally, there is no evidence regarding the impact of time overlap of IVT and MT on procedural or functional outcomes.

The just recently published randomized CHOICE trial [12] provides preliminary evidence for a clinical benefit of the adjunctive use of intra-arterial alteplase after successful mechanical thrombectomy but did not directly address possible overlapping efficacy of intravenous alteplase, as it is standard of care in most stroke centers to date.

This subgroup analysis of the GSR-ET (German Stroke Registry–Endovascular Treatment) addresses these questions and aims at quantitating the effects of a time overlap of IVT and MT (≥ 10 min) on treatment outcome and procedural safety in a case-control study design.

Material and Methods

Study Population

In this study 6635 patients of the GSR-ET (July 2015 to December 2019; http://ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03356392) were screened and out of these, 2567 patients were included. The GSR-ET is an ongoing, open-label, retrospective, multicenter registry of 25 sites in Germany collecting consecutive patients undergoing MT. A detailed description of the GSR-ET study design has been published before [13].

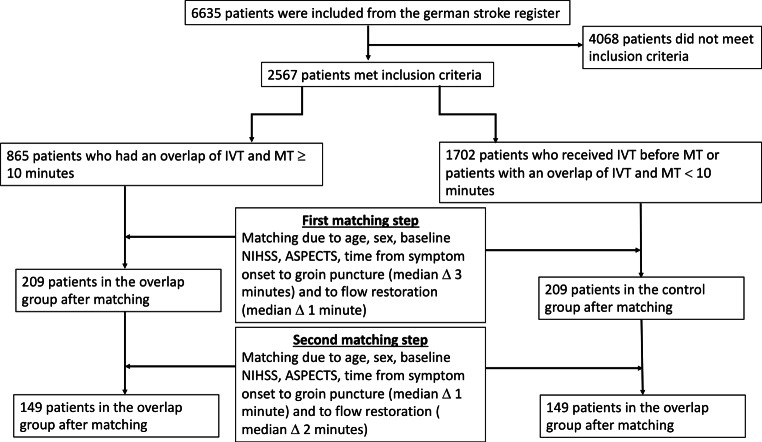

A descriptive statistical comparison of the initial cohort is provided in Table 1. Study cohort composition is graphically described in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, baseline and follow up evaluation, workflow times and clinical outcome in all patients who met inclusion criteria

| IVT and MT overlap | IVT before MT over 50 min | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) |

76 IQR 65-83 (n = 864) |

75 IQR 64-82 (n = 1702) |

0.198 |

| Sex, female No./total (%) | 426/864 (49.2) | 872/1702 (51.2) | 0.356 |

| Clinical and imaging evaluation at presentation | |||

| Baseline pmRS |

0 IQR 0-1 (n = 825) |

0 IQR 0-1 (n = 1634) |

0.163 |

| Baseline NIHSS Admission |

14 IQR 9-19 (n = 842) |

15 IQR 10-18 (n = 1647) |

0.817 |

| Baseline ASPECTS |

9 IQR 8-10 (n = 733) MW 8.8 ± 1.6 |

9 IQR 7-10 (n = 1390) M 8.4 ± 1.8 |

<0.001 |

| ACA |

2.2% n = 19/864 |

2% n = 34/1671 |

0.784 |

| MCA |

83.4% n = 721/864 |

90.1% n = 1507/1673 |

<0.001 |

| MCAm1prox |

32.8% n = 283/864 |

35.3% n = 590/1671 |

0.200 |

| MCAm1dist |

18.5% n = 160/864 |

21.8% n = 364/1671 |

0.054 |

| MCAm2 |

22.6% n = 195/864 |

21.2% n = 355/1671 |

0.443 |

| PCA |

3.9% n = 34/864 |

2.1% n = 35/1671 |

0.007 |

| Workflow times | |||

| Time from SO to IVT |

93 IQR 73-130 (n = 631) |

90 IQR 70-120 (n = 1176) |

0.03 |

| Time from SO to FLR |

172 IQR 140-215 (n = 556) |

259 IQR 205-324 (n = 1054) |

<0.001 |

| Time from SO to GRO |

125 IQR 105-163 (n = 621) |

210 IQR 165-270 (n = 1227) |

<0.001 |

| Clinical and imaging evaluation after intervention | |||

| Treat ae ICH | 25 (2.9%) (n = 840) | 41 (2.4%) (n = 1611) | 1.0 |

| 24h NIHSS |

6 IQR 2-16 (n = 743) MW 9.9 ± 9.9 |

10 IQR 4-18 (n = 1504) MW 12.1 ± 10.1 |

<0.001 |

| BL-24 h NIHSS |

5 (n = 743) |

2.5 (n = 1498) |

<0.001 |

| 24h NIHSS (0.1) | 141/738 (19.1%) | 150/1498 (10.0%) | <0.001 |

| 24h mRS |

4 IQR 2-5 (n = 748) MW 3.5 ± 1.6 |

4 IQR 3-5 (n = 1543) MW 3.9 ± 1.4 |

<0.001 |

| Functional long-term outcome | |||

| D90 mRS |

3 IQR 1-5 (n = 776) MW 2.8 ± 2.2 |

3 IQR 1-6 (n = 1458) MW 3.2 ± 2.2 |

<0.001 |

| Death | 163/865 (18%) | 376/1702 (22%) | 0.056 |

| Procedural outcome | |||

| Treat final TICI |

3 (n = 850) |

2b (n = 1679) |

<0.001 |

| 0 |

5.8% (n = 49) |

8.2% (n = 137) |

– |

| 1 |

1.5% (n = 13) |

0.8% (n = 14) |

– |

| 2a |

4.1% (n = 35) |

6.3% (n = 105) |

– |

| 2b |

32.6% (n = 277) |

36.5% (n = 613) |

– |

| 3 |

56% (n = 476) |

48.2% (n = 810) |

– |

24h mRS Modified Rankin Scale after 24 hours, BL-24 h NIHSS baseline NIHSS-NIHSS after 24 hours, 24h NIHSS (0.1) NIHSS of 0 or 1 after 24 hours, ACA Anterior cerebral artery, ASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, D90 mRS Modified Rankin Scale after 90 days, FLR flow restoration, GRO groin puncture, IVT Intravenous thrombolysis, MCA Middle cerebral artery, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, PCA Posterior cerebral artery, pmRS pretreatment modified Rankin Scale, SO symptom onset, TICI Thrombolysis in cerebral infarction, Treat ae ICH post treatment intracranial hemorrhage, Treat final TICI TICI after treatment

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the cohort composition and matching procedure. ASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, IVT Intravenous thrombolysis, MT Mechanical thrombectomy, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

The main inclusion criteria for all cases were (1) the diagnosis of an acute ischemic stroke attributed to large vessel occlusion, (2) intravenous alteplase administration, (3) endovascular treatment, (4) a prestroke modified Rankin Scale (mRS) 0–3. At a minimum time overlap of 10 min for IVT and MT patients were assigned to the case group. In the control group IVT had an overlap of less than 10 min or was finished prior to MT.

An overlap time of at least 10 min of analogous initiation of MT and running IVT was chosen, as the median time from groin puncture to flow restoration was around 50 min and the second half-life of alteplase for deeper tissue compartments is 40 min [14]. Thus, a sufficient pharmacological effect of the administered thrombolysis is highly probable during the endovascular procedure in this subgroup.

The initial case groups could not be well balanced especially regarding time-dependent decisive outcome affecting parameters. Therefore, we applied a matched case-control model performing the following steps to obtain two comparable case groups:

In the first step we matched the two groups with regard to age (max. age difference 5 years), sex (equal sex distribution), baseline NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) (max. difference 5 points), baseline ASPECTS (Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score) (max. difference 1 point), time from symptom onset to groin puncture (max. difference of 10 min) and time from symptom onset to flow restoration (max. difference of 10 min).

To obtain an even more accurate comparability, we further tightened the accepted time differences with the consequence of a diminished case number in each group in a second matching step. Thus, time from symptom onset to groin puncture and time from symptom onset to flow restoration were further reduced to a max. difference of 5 min each.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Endpoints

The primary functional outcome parameter was mRS at 90-day follow-up. Further surrogate markers were NIHSS at 24 h after MT/IVT, ∆NIHSS baseline/NIHSS after 24 h and NIHSS of ≤ 1 after 24 hours (surrogate parameters for early neurological improvement). Major neurological improvement was defined by a ≥ 8-point improvement in NIHSS score or an NIHSS score of 0 or 1 at 24 h [15].

The angiographic endpoint was the successful recanalization of the occluded target vessel assessed after each intervention on digital subtraction angiography with the Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI) score ≥ 2b. Occurrence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage and death were included as adverse events associated with MT/IVT.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate distribution of metric variables is described by median and IQR. For categorical data, absolute and relative frequencies are given. Standard descriptive statistics were used for all presented data.

Initially, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test data distribution in regard of normality.

Baseline characteristics were compared by outcome performing Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, Mann–Whitney U test (non-normally distributed data), and the unpaired Student’s t test (normally distributed data) for continuous variables. In a case-control approach we excluded age, sex, baseline NIHSS, ASPECTS and time to groin puncture and time to flow restoration as potential confounding factors. The therapy group was defined with regard to start of IVT and groin puncture (maximum of 10 min difference). In the control group IVT was started more than 10 min before groin puncture. All patients were selected from the GSR-ET using a case-control approach of the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 25.0 for Windows, SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Significance level was set at α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 2 5.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

A total of 864 patients fulfilled the criteria for the overlap group and 1702 patients were in the control group. Median age was 76 years in the overlap group (IQR 65–83 years), and 49.2% (426 of 864) were women. On hospital admission, median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 14 (IQR, 9–19) in the overlap group and 15 (IQR, 10–18) in the control group. Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) was 9 in both groups (IQR overlap group, 8–10; IQR control group: 7–10). Most occlusions in the overlap group were located in the MCA (83.4%; 721 of 864), 2.2% cases showed an occlusion of the ACA and 3.9% of the PCA. Within this initial cohort significant differences could be detected in time to groin puncture and time to flow restoration amongst others (Table 1). In the following steps we gradually reduced each group with regard to an equal age and sex distribution, similar ASPECTS and NIHSS admission scores and a comparable time to groin puncture and time to flow restoration.

First Matching Step

After stepwise fitting the data to a case-control model, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding age, sex, baseline ASPECTS and NIHSS, time from symptom onset to groin puncture and time from symptom onset to flow restoration. In the first approach to homogenize the two groups the differing workflow times were matched to a delta of 10 min with regard to time from symptom onset to flow restoration and time from symptom onset to groin puncture (Table 2). In this cohort the overlap group showed higher complete reperfusion levels (TICI 3: 57.9% vs. 47%), while successful recanalization (TICI ≥ 2b) was achieved in 90.3% (control: 86.7%).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics, baseline and follow-up evaluation, workflow times and outcome in patients after first matching step

| IVT and MT overlap | IVT before MT over 50 min | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) |

76 IQR 67-82 (n = 209) |

76 IQR 67-82 (n = 209) |

0.963 |

| Sex, female No./total (%) | 108/209 (51.7) | 108/209 (51.7) | 1 |

| Clinical and imaging evaluation at presentation | |||

| Baseline pmRS |

0 IQR 0-1 (n = 203) |

0 IQR 0-1 (n = 207) |

0.300 |

| Baseline NIHSS Admission |

14 IQR 9-18 (n = 207) |

14 IQR 9-18 (n = 207) |

1 |

| Baseline ASPECTS |

9 IQR 8-10 (n = 189) |

9 IQR 8-10 (n = 184) |

0.868 |

| Workflow times | |||

| Time from SO to IVT |

120 IQR 90-155 (n = 203) |

70 IQR 55-85 (n = 202) |

<0.001 |

| Time from SO to FLR |

199 IQR 163-236 (n = 195) |

198 IQR 170-238 (n = 181) |

0.708 |

| Time from SO to GRO |

149 IQR 125-184 (n = 209) |

152 IQR 127-180 (n = 209) |

0.628 |

| Clinical and imaging evaluation after intervention | |||

| Treat ae ICH | 8 (3.8%) (n = 209) | 7 (3.3%) (n = 209) | 1.0 |

| 24h NIHSS |

7 IQR 2-15 (n = 189) MW 9.9 ± 9.4 |

8 IQR 3-16 (n = 194) MW 10.3 ± 8.6 |

0.384 |

| BL-24 h NIHSS |

4 IQR 0-9 (n = 188) |

3 IQR 0-8 (n = 193) |

0.118 |

| 24h NIHSS (0.1) | 32/209 (15.3%) | 32/209 (15.3%) | – |

| 24h mRS |

4 IQR 2-5 (n = 190) MW 3.6 ± 1.6 |

4 IQR 2-5 (n = 197) MW 3.6 ± 1.6 |

0.950 |

| Functional long-term outcome | |||

| D90 mRS |

3 IQR 1-5 (n = 184) MW 2.8 ± 2.2 |

3 IQR 1-6 (n = 192) MW 3.2 ± 2.2 |

0.052 |

| Death | 29/184 (15.8%) | 51/192 (26.6%) | 0.013 |

| Procedural outcome | |||

| Treat final TICI |

3 (n = 207) |

2b (n = 204) |

0.026 |

| 0 |

2.6% (n = 6) |

5.9% (n = 12) |

– |

| 1 |

2.4% (n = 5) |

0.9% (n = 2) |

– |

| 2a |

4.3% (n = 9) |

6.4% (n = 13) |

– |

| 2b |

32.4% (n = 67) |

39.7% (n = 81) |

– |

| 3 |

57.9% (n = 120) |

47.0% (n = 96) |

– |

24h mRS Modified Rankin Scale after 24 hours, BL-24 h NIHSS baseline NIHSS-NIHSS after 24 hours, 24h NIHSS (0.1) NIHSS of 0 or 1 after 24 hours, ACA Anterior cerebral artery, ASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, D90 mRS Modified Rankin Scale after 90 days, FLR flow restoration, GRO groin puncture, IVT Intravenous thrombolysis, MCA Middle cerebral artery, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, PCA Posterior cerebral artery, pmRS pretreatment modified Rankin Scale, SO symptom onset, TICI Thrombolysis in cerebral infarction, Treat ae ICH post treatment intracranial hemorrhage, Treat final TICI TICI after treatment

Further, after the first adjustment step the overlap group revealed nearly significantly better functional outcome with regard to D90 mRS (overlap group: mRS 3 IQR 1–5; control group: mRS 3 IQR 1–6, p = 0.052). While in the overlap group 15.8% of patients died after treatment, over one quarter of patients died in the control group (26.6%, p = 0.013). No significant differences could be detected in percentages of patients with best functional outcome at day 90 (mRS 0) (p = 0.192).

Second Matching Step

After performing the second matching step, median time from onset to groin puncture was 154 min (IQR, 128–187 min) and median time to flow restoration was 203 min (IQR, 164–244 min) in the overlap group (control: time to groin puncture: 155 min IQR, 127–184 min; time to flow restoration was 201 min IQR, 177–244 min) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics, baseline and follow up evaluation, workflow times and outcome in patients after second matching step

| IVT and MT overlap | IVT before MT over 50 min | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) |

76 IQR 68-82 (n = 149) |

77 IQR 68-82 (n = 149) |

0.685 |

| Sex, female No./total (%) | 82/149 (55) | 82/149 (55) | 1 |

| Clinical and imaging evaluation at presentation | |||

| Baseline pmRS |

0 IQR 0-1 (n = 143) |

0 IQR 0-1 (n = 147) |

0.364 |

| Baseline NIHSS Admission |

14 IQR 9-17 (n = 148) |

14 IQR 9-17 (n = 148) |

1 |

| Baseline ASPECTS |

9 IQR 8-10 (n = 134) |

9 IQR 8-10 (n = 132) |

0.495 |

| Workflow times | |||

| Time from SO to IVT |

120 IQR 90-152 (n = 145) |

70 IQR 55-90 (n = 144) |

<0.001 |

| Time from SO to FLR |

203 IQR 164-244 (n = 135) |

201 IQR 177-244 (n = 131) |

0.579 |

| Time from SO to GRO |

154 IQR 128-187 (n = 149) |

155 IQR 127-184 (n = 149) |

0.957 |

| Clinical and imaging evaluation after intervention | |||

| Treat ae ICH | 6 (4%) (n = 149) | 6 (4%) (n = 149) | – |

| 24h NIHSS |

8 IQR 2-16 (n = 131) MW 10.7 ± 10.2 |

8 IQR 4-18 (n = 137) MW 10.4 ± 8.5 |

0.733 |

| BL-24 h NIHSS |

4 IQR 0-7 (n = 131) |

4 IQR −1-8 (n = 136) |

0.834 |

| 24h NIHSS (0.1) | 23/131 (17.5%) | 22/137 (16.1%) | – |

| 24h mRS |

4 IQR 2-5 (n = 133) MW 3.6 ± 1.6 |

4 IQR 2-5 (n = 140) MW 3.6 ± 1.6 |

0.648 |

| Functional long-term outcome | |||

| D90 mRS |

3 IQR 1-5 (n = 132) MW 2.9 ± 2.2 |

3 IQR 1-6 (n = 140) MW 3.4 ± 2.3 |

0.090 |

| Death | 25/132 (18.9%) | 43/140 (30.7%) | 0.006 |

| Procedural outcome | |||

| Treat final TICI |

3 (n = 148) |

2b (n = 147) |

0.238 |

| 0 |

3.3% (n = 5) |

6.8% (n = 10) |

– |

| 1 |

3.3% (n = 5) |

0.6% (n = 1) |

– |

| 2a |

6.1% (n = 9) |

6.8% (n = 10) |

– |

| 2b |

34.5% (n = 51) |

39.5% (n = 58) |

– |

| 3 |

52.7% (n = 78) |

46.3% (n = 68) |

– |

24h mRS Modified Rankin Scale after 24 hours, BL-24 h NIHSS baseline NIHSS- NIHSS after 24 hours, 24h NIHSS (0.1) NIHSS of 0 or 1 after 24 hours, ACA Anterior cerebral artery, ASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, D90 mRS Modified Rankin Scale after 90 days, FLR flow restoration, GRO groin puncture, IVT Intravenous thrombolysis, MCA Middle cerebral artery, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, PCA Posterior cerebral artery, pmRS pretreatment modified Rankin Scale, SO symptom onset, TICI Thrombolysis in cerebral infarction, Treat ae ICH post treatment intracranial hemorrhage, Treat final TICI TICI after treatment

In the overlap group 52.7% reached a postinterventional TICI 3 (control: 46.3%). Successful recanalization was achieved in 87.2% (129 of 148) in the overlap group and in 85.8% (126 of 147) in the control group. In 5 patients of the overlap group recanalization was considered unsuccessful (TICI 0), compared with 10 patients in the control group (Table 3). In both groups 6 patients were diagnosed with intracranial hemorrhage in posttreatment imaging (4%) (Table 3). A preserved good functional outcome could be shown in both groups (overlap group: mRS 3, IQR 1–5; control group: mRS 3, IQR 1–6). After the second matching step a statistical tendency towards a better outcome in the overlap group could be detected (p = 0.09).

Neither NIHSS after 24 h nor ∆NIHSS baseline/NIHSS after 24 h showed significant differences in the two groups. Of note, posttreatment mortality was 18% in the overlap group and 30% in the control group (p = 0.006) (Table 3). Comparing both groups no significant differences could be detected with regard to the most favorable mRS outcome of 0 (p = 0.148).

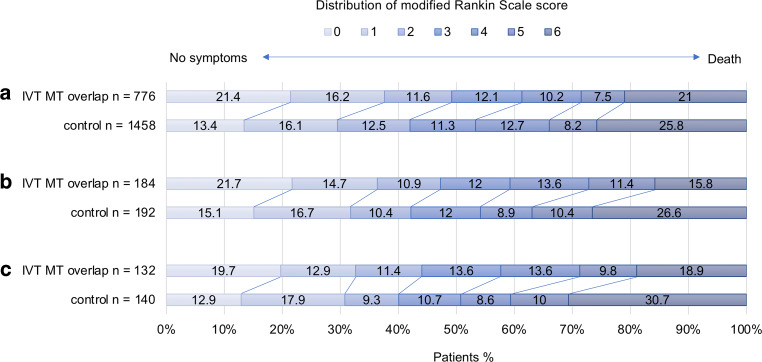

Functional outcome parameters (mRS after 90 days) for the initial cohort as well as after stepwise matching are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

In this shift analysis the distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at day 90 is shown. a Includes the initial unmatched cohort, b cohort after first matching step, c cohort after second matching step. IVT Intravenous thrombolysis, MT Mechanical thrombectomy

Discussion

The combination of IVT and MT as a matter of principle is still common sense and widely accepted in the stroke community. Recently, there are several randomized controlled trials questioning this approach and first results show a non-inferiority of EVT alone vs. a combination therapy [16–18]. Podlasek et al. concisely summarized the combined trial data of six studies including SWIFT-DIRECT and DIRECT-SAFE, showing a clinical non-inferiority of direct mechanical thrombectomy to bridging therapy [19] but significantly better technical success rates in the MT/IVT groups; however, there is still a paucity of evidence concerning the concomitant use of IVT and MT with overlapping lysis activity during the MT procedure. As there are no guidelines on the temporal orchestration of IVT and MT, a certain insecurity has spread among neurointerventionalists and neurologists whether to stop or to continue alteplase administration before initiation or after completion of the thrombectomy procedure [10]. This ambiguity is based on concerns regarding iatrogenically increasing the risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage or thrombus fragmentation if MT is performed under concomitant unmitigated potency of IVT, which leads to a discussion of principles [10, 20–22]. Summarizing the results of the presented study several key aspects and major concerns regarding the execution of IVT are touched.

First, the procedural as well as the functional outcome in patients undergoing overlapping IVT and MT does not differ significantly after matching of the two groups was performed. It rather seems that patients in the overlap group might benefit from parallel IVT administration as a tendency towards lower D90 mRS scores (p = 0.09) than in the control group could be revealed. Interestingly, unsuccessful recanalization was twice as high in the control group as in the overlap group (TICI 0: 3.3% vs. 6.8%). Second, the risk of postinterventional intracranial hemorrhage was not increased in the overlap group (4% in both groups after adjustment). Third, postinterventional mortality was not increased when performing overlapping IVT and MT. Quite the contrary, comparing the two groups, 18% of patients in the overlap group died after thrombectomy, whereas nearly one third of patients in the control group died (30%, p = 0.006). Taken together, the results of this study suggest that there is no need for stopping IVT immediately before starting or after having completed the MT procedure in patients with running alteplase administration. These results seem to be in line with the recently presented preliminary data from the SWIFT-DIRECT trial [24], as the investigated lysis group in this trial mainly consisted of mothership patients with short procedure times, making an overlapping lysis activity in this group probable. This actually raises the additional question if the positive trial results may be partially based on the positive effect of an overlapping lysis effect, and the results may have been less clear, if also transfer patients with no overlapping activity would have been included.

In addition, our results strongly support the results of the most recently published CHOICE trial [12], which shows an additional benefit of the adjunctive use of intra-arterial alteplase after successful recanalization. Especially the remarkable effect on reducing mortality and the similarity of the mRS shift analyses are surprisingly consistent in both studies. In this context, our results seem to add evidence to the question whether the intravenous approach might be sufficient compared with an additional intra-arterial application of alteplase.

There are several possible reasons for a tendentially better functional outcome in the overlap group compared to the control group. During the closer analysis of the differences in the mRS values, it became clear that very similar to the results of the CHOICE trial, the differences in favor of the overlap group are mainly based on the switch of patients from mRS 1 to 0 and to a lesser extent, from 3 and 4 to 6 (see Fig. 2). The first effect is probably explainable by the lysis of persistent micro-occlusions in the capillary vasculature or very peripheral occlusions due to thrombus fragments after successful MT of the large vessel occlusion, leading to a higher percentage of fully asymptomatic patients. Also, more frequently occurring thrombus migration in the control group to mechanically inaccessible regions due to longer impact times of the lysis might contribute to this effect. This also might explain the results of fewer postprocedural angiograms classified as TICI 3 in all controls. The second effect might be due to the same effect in the opposite group of patients suffering from a severe stroke despite successful recanalization, who develop without IVT an even bigger malignant infarction with a higher percentage of deceased patients.

To the best of our knowledge, besides the CHOICE trial addressing an additional intra-arterial approach, there are no published data available investigating the problem we focused on in the actual study. One recent publication, also from the GSR investigators, found a better outcome in patients with inhouse bridging lysis (which should in many cases be overlapping to MT) compared to patients without lysis therapy [23, 24]. But, although these data might also support the notion of the safety of concomitant lysis, their work does not address the same topic, as they compared lysis vs. non-lysis patients and not unmitigated active lysis vs. previously iv-treated patients. Additionally, by having access to much more patient datasets, our approach of a matched pair analysis became possible.

The main strength of our study is the large patient number of a real-world population, which enabled a very exact matching of the groups with still considerable patient numbers. Second, we provide additional evidence for applying the direct clinical consequence of not stopping running thrombolysis, before, during or after the MT procedure (obviously, unless no other causes demand this).

However, it has to be considered, that the presented results are dependent on the organizational and infrastructural characteristics of the German stroke system regarding localization of primary and tertiary stroke centers and the associated infrastructure as well as transportation times. While mechanical thrombectomy can only be performed in tertiary care institutions, thrombolysis is frequently initiated in peripheral hospitals leading to a limited number of patients where overlapping thrombolytic activity can be achieved. This is even more true in regions with more centralized organizational structures, where secondary transport is even more common and transportation times might be longer.

Besides this our study has certain limitations. First of all, this is a retrospective study with all shortcomings associated with this conceptual design, resulting in a certain selection bias; however, applying the described matching steps (including baseline NIHSS as a decisive matching parameter), we tried to minimize this bias as far as possible. Furthermore, considering the observational character of our analysis, remaining confounding factors cannot be excluded. Additionally, all collected clinical and imaging data are prone to subjectivity due to the multicenter study design without independent re-evaluation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the presented multicenter study provides evidence for the approach of not stopping running thrombolysis before, during or after the MT procedure in acute stroke treatment, unless no other inevitable causes demand this. The data reveal a tendency for better functional outcome, with comparable risk for intracranial hemorrhage and lower postinterventional mortality in the overlap group. The results strongly support the recently published data of a possible benefit of additional intra-arterial alteplase administration after successful MT. These results may have immediate practical implications for acute treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

Members of GSR-ET Steering Committee Investigators

Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf: Prof. Dr. C. Gerloff, Prof. Dr. J. Fiehler, Prof. Dr. G. Thomalla, Dr. med. A. Alegiani; Klinikum rechts der Isar: Dr. Boeckh-Behrens, Dr. Silke Wunderlich; Universitätsklinik Tübingen: Prof. Dr. Ulrike Ernemann, Dr. Sven Poli; Charité—Campus Benjamin Franklin und Campus Charité Mitte, Berlin: Dr. Eberhard Siebert, Prof. Dr. Christian H. Nolte; Charité—Campus Virchow Klinikum, Berlin: Dr. Sarah Zweynert, Dr. Georg Bohner; Sana Klinikum Offenbach: Dr. med. Alexander Ludolph, Dr. med. Karl-Heinz Henn; Uniklinik Frankfurt/Main: Dr. med. Jan Hendrik Schäfer, Dr. Fee Keil; Asklepios Klinik Altona: Prof. Dr. Joachim Röther, Prof. Dr. Bernd Eckert; Klinikum Altenburger Land: Prof. Dr. Jörg Berrouschot, Dr. Albrecht Bormann; Uniklinik Bonn: Dr. med. Franziska Dorn, Prof. Dr. Gabor Petzold; Klinikum Lüneburg: Dr. Christoffer Kraemer, Dr. med Hannes Leischner; Uniklinik München (LMU): Dr. med. Christoph Trumm, Dr. Dr. Steffen Tiedt, Dr. Lars Kellert; Klinikum Osnabrück: Dr. Martina Petersen, Prof. Dr. Florian Stögbauer; Bezirkskrankenhaus Günzburg: Dr. med. Michael Braun, Prof. Dr. Gerhard F. Hamann; Universitätsmedizin Mainz: Prof. Dr. Klaus Gröschel, Dr. Timo Uphaus; Uniklinik RWTH Aachen: Dr. med. Arno Reich, Prof. Dr. med. Omid Nikoubashman; Johannes Wesling Klinikum Minden: Prof. Dr. med. Peter Schellinger, Prof. Dr. med. Jan Borggrefe; Klinikum Nordstadt: Dr. med. Jörg Hattingen; Universitätsmedizin Göttingen: Prof. Dr. med. Jan Liman, Dr. med. Marielle Ernst.

Acknowledgements

The work has been presented at the 56. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Neuroradiologie e. V. (DGNR) 2021. The abstract of the oral presentation is available at 56. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Neuroradiologie e. V. Clin Neuroradiol 31, 1–73 (2021). 10.1007/s00062-021-01075-5.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

T. Boeckh-Behrens received speaker honoraria from Philips, Microvention and Phenox and reports consultancy fees from Microvention outside of the submitted work. C. Zimmer disclosed no relevant relationships regarding activities related to the present article. He has served on scientific advisory boards for Philips and Bayer Schering; serves as co-editor on the Advisory Board of Clinical Neuroradiology; has received speaker honoraria from Bayer-Schering and Philips; the institution has received research support and investigator fees for clinical studies from Biogen Idec, Quintiles, MSD Sharp & Dome, Boehringer Ingelheim, Inventive Health Clinical UK Ltd., Advance Cor, Brainsgate, Pfizer, Bayer-Schering, Novartis, Roche, Servier, Penumbra, WCT GmbH, Syngis, SSS International Clinical Research, PPD Germany GmbH, Worldwide Clinical Trials Ltd., Phenox, Covidien, Actelion, Medivation, Medtronic, Harrison Clinical Research, Concentric, Pharmtrace, Reverse Medical Corp., Premier Research Germany Ltd., Surpass Medical Ltd., GlaxoSmithKline, AXON Neuroscience, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Acandis, EISAI, NeuroRx, Italfarmaco, Bioclinica, MIAC and IXICO. No patents issued and pending. E. Burian, D. Sepp, M. Lehm, K. Bernkopf, S. Wunderlich, I. Riederer, C. Maegerlein, and A. Alegiani declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants or their legal representatives. In case of early death of patients, informed consent was waived to avoid bias.

Footnotes

The authors Egon Burian and Dominik Sepp contributed equally to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, Blackwell L, Albers G, Bluhmki E, Brott T, Cohen G, Davis S, Donnan G, Grotta J, Howard G, Kaste M, Koga M, von Kummer R, Lansberg M, Lindley RI, Murray G, Olivot JM, Parsons M, Tilley B, Toni D, Toyoda K, Wahlgren N, Wardlaw J, Whiteley W, del Zoppo GJ, Baigent C, Sandercock P, Hacke W, G. Stroke Thrombolysis Trialists’ Collaborative Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1929–1935. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60584-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, Nederkoorn PJ, Wermer MJ, van Walderveen MA, Staals J, Hofmeijer J, van Oostayen JA, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener HC, Levy EI, Pereira VM, Albers GW, Cognard C, Cohen DJ, Hacke W, Jansen O, Jovin TG, Mattle HP, Nogueira RG, Siddiqui AH, Yavagal DR, Baxter BW, Devlin TG, Lopes DK, Reddy VK, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2285–2295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, de Miquel MA, Molina CA, Rovira A, San Roman L, Serena J, Abilleira S, Ribo M, Millan M, Urra X, Cardona P, Lopez-Cancio E, Tomasello A, Castano C, Blasco J, Aja L, Dorado L, Quesada H, Rubiera M, Hernandez-Perez M, Goyal M, Demchuk AM, von Kummer R, Gallofre M, Davalos A, Investigators RT. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2296–2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamal, Montanera WJ, Poppe AY, Ryckborst KJ, Silver FL, Shuaib A, Tampieri D, Williams D, Bang OY, Baxter BW, Burns PA, Choe H, Heo JH, Holmstedt CA, Jankowitz B, Kelly M, Linares G, Mandzia JL, Shankar J, Sohn SI, Swartz RH, Barber PA, Coutts SB, Smith EE, Morrish WF, Weill A, Subramaniam S, Mitha AP, Wong JH, Lowerison MW, Sajobi TT, Hill MD, Investigators ET. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1019–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, Dewey HM, Churilov L, Yassi N, Yan B, Dowling RJ, Parsons MW, Oxley TJ, Wu TY, Brooks M, Simpson MA, Miteff F, Levi CR, Krause M, Harrington TJ, Faulder KC, Steinfort BS, Priglinger M, Ang T, Scroop R, Barber PA, McGuinness B, Wijeratne T, Phan TG, Chong W, Chandra RV, Bladin CF, Badve M, Rice H, de Villiers L, Ma H, Desmond PM, Donnan GA, Davis SM, Investigators E-I. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1009–1018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ospel JM, Singh N, Almekhlafi MA, Menon BK, Butt A, Poppe AY, Jadhav A, Silver FL, Shah R, Dowlatshahi D, O’Hare AM, Demchuk AM, Goyal M, Hill MD. Early Recanalization With Alteplase in Stroke Because of Large Vessel Occlusion in the ESCAPE Trial. Stroke. 2021;52(1):304–307. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahlgren N, Moreira T, Michel P, Steiner T, Jansen O, Cognard C, Mattle HP, van Zwam W, Holmin S, Tatlisumak T, Petersson J, Caso V, Hacke W, Mazighi M, Arnold M, Fischer U, Szikora I, Pierot L, Fiehler J, Gralla J, Fazekas F, Lees KR, Eso-Ksu EEEE. Mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: Consensus statement by ESO-Karolinska Stroke Update 2014/2015, supported by ESO, ESMINT, ESNR and EAN. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(1):134–147. doi: 10.1177/1747493015609778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, Coffey CS, Hoh BL, Jauch EC, Johnston KC, Johnston SC, Khalessi AA, Kidwell CS, Meschia JF, Ovbiagele B, Yavagal DR, American Heart Association American heart association/American stroke association focused update of the 2013 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute Ischemic stroke regarding Endovascular treatment: a guideline for Healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2015;46(10):3020–3035. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellert L, Wollenweber FA, Thomalla G, Nolte CH, Fiehler J, Ringleb PA, Dorn F. Thrombolysis management in thrombectomy patients: Real-life data from German stroke centres. Eur Stroke J. 2017;2(4):356–360. doi: 10.1177/2396987317727229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanak D, Kocher M, Veverka T, Cerna M, Kral M, Burval S, Skoloudik D, Prasil V, Zapletalova J, Herzig R, Kanovsky P. Acute combined revascularization in acute ischemic stroke with intracranial arterial occlusion: self-expanding solitaire stent during intravenous thrombolysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(9):1273–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renú A, Millán M, San Román L, Blasco J, Martí-Fàbregas J, Terceño M, Amaro S, Serena J, Urra X, Laredo C, Barranco R, Camps-Renom P, Zarco F, Oleaga L, Cardona P, Castaño C, Macho J, Cuadrado-Godía E, Vivas E, López-Rueda A, Guimaraens L, Ramos-Pachón A, Roquer J, Muchada M, Tomasello A, Dávalos A, Torres F, Chamorro Á; CHOICE Investigators. Effect of Intra-arterial Alteplase vs Placebo Following Successful Thrombectomy on Functional Outcomes in Patients With Large Vessel Occlusion Acute Ischemic Stroke: The CHOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;327:826–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Wollenweber FA, Tiedt S, Alegiani A, Alber B, Bangard C, Berrouschot J, Bode FJ, Boeckh-Behrens T, Bohner G, Bormann A, Braun M, Dorn F, Eckert B, Flottmann F, Hamann GF, Henn KH, Herzberg M, Kastrup A, Kellert L, Kraemer C, Krause L, Lehm M, Liman J, Lowens S, Mpotsaris A, Papanagiotou P, Petersen M, Petzold GC, Pfeilschifter W, Psychogios MN, Reich A, von Rennenberg R, Rother J, Schafer JH, Siebert E, Siedow A, Solymosi L, Thonke S, Wagner M, Wunderlich S, Zweynert S, Nolte CH, Gerloff C, Thomalla G, Dichgans M, Fiehler J. Functional outcome following stroke Thrombectomy in clinical practice. Stroke. 2019;50(9):2500–2506. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang X, Moreton FC, Kalladka D, Cheripelli BK, MacIsaac R, Tait RC, Muir KW. Coagulation and Fibrinolytic activity of Tenecteplase and Alteplase in acute Ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(12):3543–3546. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saposnik G, Di Legge S, Webster F, Hachinski V. Predictors of major neurologic improvement after thrombolysis in acute stroke. Neurology. 2005;65(8):1169–1174. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180687.75907.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki K, Matsumaru Y, Takeuchi M, Morimoto M, Kanazawa R, Takayama Y, Kamiya Y, Shigeta K, Okubo S, Hayakawa M, Ishii N, Koguchi Y, Takigawa T, Inoue M, Naito H, Ota T, Hirano T, Kato N, Ueda T, Iguchi Y, Akaji K, Tsuruta W, Miki K, Fujimoto S, Higashida T, Iwasaki M, Aoki J, Nishiyama Y, Otsuka T, Kimura K, Investigators SS. Effect of mechanical Thrombectomy without vs with intravenous Thrombolysis on functional outcome among patients with acute Ischemic stroke: the SKIP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(3):244–253. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang P, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Treurniet KM, Chen W, Peng Y, Han H, Wang J, Wang S, Yin C, Liu S, Wang P, Fang Q, Shi H, Yang J, Wen C, Li C, Jiang C, Sun J, Yue X, Lou M, Zhang M, Shu H, Sun D, Liang H, Li T, Guo F, Ke K, Yuan H, Wang G, Yang W, Shi H, Li T, Li Z, Xing P, Zhang P, Zhou Y, Wang H, Xu Y, Huang Q, Wu T, Zhao R, Li Q, Fang Y, Wang L, Lu J, Li Y, Fu J, Zhong X, Wang Y, Wang L, Goyal M, Dippel DWJ, Hong B, Deng B, Roos Y, Majoie C, Liu J, Investigators D-M. Endovascular Thrombectomy with or without intravenous Alteplase in acute stroke. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1981–1993. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zi W, Qiu Z, Li F, Sang H, Wu D, Luo W, Liu S, Yuan J, Song J, Shi Z, Huang W, Zhang M, Liu W, Guo Z, Qiu T, Shi Q, Zhou P, Wang L, Fu X, Liu S, Yang S, Zhang S, Zhou Z, Huang X, Wang Y, Luo J, Bai Y, Zhang M, Wu Y, Zeng G, Wan Y, Wen C, Wen H, Ling W, Chen Z, Peng M, Ai Z, Guo F, Li H, Guo J, Guan H, Wang Z, Liu Y, Pu J, Wang Z, Liu H, Chen L, Huang J, Yang G, Gong Z, Shuai J, Nogueira RG, Yang Q, Investigators DT. Effect of Endovascular treatment alone vs intravenous Alteplase plus Endovascular treatment on functional independence in patients with acute Ischemic stroke: the DEVT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(3):234–243. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podlasek A, Dhillon PS, Butt W, Grunwald IQ, England TJ. To bridge or not to bridge: summary of the new evidence in endovascular stroke treatment. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2022;7(3):179–181. doi: 10.1136/svn-2021-001465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaghi S, Eisenberger A, Willey JZ. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke after thrombolysis with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a review of natural history and treatment. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(9):1181–1185. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin X, Cao Y, Yan J, Zhang Z, Ye Z, Huang X, Cheng Z, Han Z. Risk Factors for Early Intracerebral Hemorrhage after Intravenous Thrombolysis with Alteplase. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27(11):1176–1182. doi: 10.5551/jat.49783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whiteley WN, Slot KB, Fernandes P, Sandercock P, Wardlaw J. Risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 55 studies. Stroke. 2012;43(11):2904–2909. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.665331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maier IL, Leha A, Badr M, Allam I, Bahr M, Jamous A, Hesse A, Psychogios MN, Behme D, Liman J. Inhouse Bridging Thrombolysis Is Associated With Improved Functional Outcome in Patients With Large Vessel Occlusion Stroke: Findings From the German Stroke Registry. Front Neurol. 2021;12:649108. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.649108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer Urs, Kaesmacher Johannes, Strbian Daniel, Eker Omer, Cognard Christoph, Plattner Patricia S, Bütikofer Lukas, Mordasini Pasquale, Deppeler Sandro, Pereira Vitor M, Albucher Jean François, Darcourt Jean, Bourcier Romain, Benoit Guillon, Papagiannaki Chrysanthi, Ozkul-Wermester Ozlem, Sibolt Gerli, Tiainen Marjaana, Gory Benjamin, Richard Sébastien, Liman Jan, Ernst Marielle Sophie, Boulanger Marion, Barbier Charlotte, Mechtouff Laura, Zhang Liqun, Marnat Gaultier, Sibon Igor, Nikoubashman Omid, Reich Arno, Consoli Arturo, Lapergue Bertrand, Ribo Marc, Tomasello Alejandro, Saleme Suzana, Macian Francisco, Moulin Solène, Pagano Paolo, Saliou Guillaume, Carrera Emmanuel, Janot Kevin, Hernández-Pérez María, Pop Raoul, Schiava Lucie Della, Luft Andreas R, Piotin Michel, Gentric Jean Christophe, Pikula Aleksandra, Pfeilschifter Waltraud, Arnold Marcel, Siddiqui Adnan H, Froehler Michael T, Furlan Anthony J, Chapot René, Wiesmann Martin, Machi Paolo, Diener Hans-Christoph, Kulcsar Zsolt, Bonati Leo H, Bassetti Claudio L, Mazighi Mikael, Liebeskind David S, Saver Jeffrey L, Gralla Jan, Alonso Angelika, Arquizan Caroline, Barreau Xavier, Beaujeux Rémy, Behme Daniel, Boeckh-Behrens Tobias, Boehme Christian, Boix Martí, Boulouis Grégoire, Bricout Nicolas, Broc Nicolas, Cereda Carlo W., Chabert Emmanuel, Cho Tae-Hee, Cianfoni Alessandro, Costalat Vincent, Denier Christian, Di Maria Frederico, du Mesnil de Rochemont Richard, Fearon Patricia, Ferrier Anna, Fischer Sebastian, Gauberti Maxime, Gaudron Marie, Gimenez Laetitia, Globas Christoph, Görtler Michael, Goyal Mayank, Hilker-Roggendorf Ruediger, Hill Michael D., Hua Vi Tuan, Humbertjean Lisa, Jansen Olav, Jung Simon, Kägi Georg, Kelly Michael E., Kleffner Ilka, Knoflach Michael, Nedeltchev Krassen, Krause Lars Udo, Lappalainen Kimmo, Lefebvre Margaux, Leyon Joe, Liao Liang, Liegey Jean-Sebastien, Loehr Christian, Michel Patrik, Nannoni Stefania, Nicholson Patrick, Nico Lorena, Obadia Michael, Ognard Julien, Ogungbemi Ayokunle, Olivot Jean-Marc, Escalard Simon, Pasi Marco, Peeling Lissa, Perez Jane, Petersen Martina, Piechowiak Eike, Raposo Roberto, Räty Silja, Reitz Sarah C., Remollo Sebastià, Remonda Luca, Rennie Ian, Requena Manuel, Riabikin Alexander, Riva Roberto, Rouchaud Aymeric, Rosi Andrea, Rubiera Marta, Spelle Laurent, Schnieder Marlena, Schaafsma Joanna D., Schubert Tilman, Schulz Jörg B., Siddiqui Mohammed, Soize Sébastien, Sonnberger Michael, Touze Emmanuel, Triquenot Aude, Turc Guillaume, Vieira Lucy, Ben Hassen Wagih, Wagner Judith N., Wasser Katrin, Weber Johannes, Wenz Holger, Weisenburger-Lile David, Wodarg Fritz, Wolff Valérie, Wunderlich Silke. Thrombectomy alone versus intravenous alteplase plus thrombectomy in patients with stroke: an open-label, blinded-outcome, randomised non-inferiority trial. The Lancet. 2022;400(10346):104–115. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]